Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 6

November 21, 2025

[Ilya Somin] Trump's Shameful Attempt to Reprise the Munich Agreement With Ukraine - and What to do About it

[Trump's 28-point "peace" plan for the Russia-Ukraine War is a reprise of the 1938 Munich agreement, which dismembered Czechoslovakia for the benefit of Nazi Germany. But US and European supporters of Ukraine can do much to resist it.]

Denys Bozduhan | Dreamstime.com

Denys Bozduhan | Dreamstime.com President Trump has presented a 28-point "peace" plan for the Russia-Ukraine war, which - in reality - is a demand for Ukrainian capitulation. The administration threatens to cut off military aid and intelligence sharing if Ukraine refuses.

Among other things, the proposal requires Ukraine to give up extensive territory to Russia - including key strategic regions that Russia does not currently control - and caps the size of the Ukrainian armed forces, while imposing no similar limitations on Russia's military. It also includes a variety of built-in excuses for Russia to renew the war (such as the ban on "Nazi" propaganda in Ukraine, which could be violated whenever some fringe Ukrainian nationalist group makes public statements that could be interpreted as Nazi-like).

There are no meaningful countervailing constraints on Russia. While the Russians are required to stop the war, this is the sort of agreement they have repeatedly violated over the last decade. And the loss of strategic territory combined with limits on Ukrainian military power would make Ukraine intensely vulnerable to any such Russian treachery, which in turn makes the treachery highly likely to occur.

The plan does apparently include an unspecified security "guarantee" for Ukraine. But, absent specific provisions for the use of US or other NATO forces in the event of Russian aggression, such guarantees have little value. Ukraine in fact already got such a guarantee from the US, Britain, and Russia in the 1994 Budapest agreement, in exchange for giving up its nuclear weapons. It failed miserably.

The obvious historical analogue for Trump's plan is the 1938 Munich agreement, under which Britain and France forced Czechoslovakia to give up a large part of its territory to Nazi Germany, in exchange for a promise of peace. The Germans broke the promise the very next year, seizing the rest of Czechoslovakia.

In one crucial way, the Trump deal is is even worse than the Munich agreement was. The latter at least did not limit the size of Czechoslovakia's military. The Trump proposal does just that, with respect to Ukraine.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky seems inclined to reject the deal, and for good reason. Better to fight on with little or no US support than to accept capitulation.

There is, however, much that US and European supporters of Ukraine can do to counter the Trump plan. Europeans should finally confiscate the $300 billion in Russian state assets currently frozen in the West (mostly in Europe), and use them to fund Ukraine's war effort, thereby offsetting much of the likely decline in US assistance, and sending the Kremlin a powerful signal of allied determination.

In a November 2023 post, I rebutted a range of different objections to confiscating Russian state assets, including 1) claims that it would violate property rights protections in the US and various European constitutions, 2) sovereign immunity arguments, 3) arguments that it would be unfair to the Russian people, 4) slippery slope concerns, and 5) the danger of Russian retaliation. All of these points remain relevant today. Stephen Rademaker, former chief counsel to the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, has a recent Washington Post article further addressing the retaliation issue.

In the US, Congress should pass a law granting new military assistance to Ukraine and make delivery nondiscretionary, barring the executive from withholding it. I am not optimistic that Congress will actually do any such thing. But it is worth trying. Aid for Ukraine commands broad public support, and is backed by almost all congressional Democrats, plus a substantial number of Republicans in both the House and the Senate. A concerted bipartisan effort to enact new aid probably won't be able to achieve a veto-proof majority. But it could focus attention on the issue, and make it harder for the administration to stick to its current dangerous course.

In a February 2025 post, I summarized the many moral and strategic reasons why the West should back Ukraine in this conflict, and addressed counterarguments (such as that assistance is too expensive, that it diverts resources from more important foreign policy objectives, or that Russia's war is justified by the need to "protect" the Russian-speaking population in Ukraine). Here, I will merely reiterate that appeasing Vladimir Putin is likely to prove foolish, as well as immoral. His regime has repeatedly demonstrated that it has a deep hostility to Western liberal democracy, and that it cannot be trusted to abide by any agreements, unless compelled by the threat of overwhelming force.

The post Trump's Shameful Attempt to Reprise the Munich Agreement With Ukraine - and What to do About it appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] California Appellate Court Generally Rejects Pseudonymity for Defamation Plaintiffs (Including in #TheyLied Sexual Assault Allegation Cases)

From today's opinion in Roe v. Smith, decided by Justice Anne Richardson, joined by Justices Elwood Lui and Victoria Chavez:

In 2022, plaintiffs [Jane Roe and John Doe] and [defendant] Jenna [Smith] were all students at the same high school in Los Angeles County…. At the time, plaintiffs were in a dating relationship, which continued at least through the date of the complaint….

In March 2023, Jenna began telling other students at the high school that John had sexually assaulted her and Jane. In April 2023, [defendant] Mother [Smith] told parents of other members of the club that John had sexually harassed Jenna….

The school launched an investigation, with which John voluntarily cooperated. While the investigation was ongoing, Jenna continued to tell other students John had engaged in sexual misconduct towards her and Jane. The "school rumor mill [ran] wild" with this information and plaintiffs received "dozens" of harassing and violent comments on their social media accounts. Plaintiffs allege Jenna was behind these comments….

The school's investigation into Jenna's complaint finally concluded in August 2023, finding John was "not responsible for any of the claims [Jenna] launched against him."

Plaintiffs sued for defamation and related torts, and "sought damages in excess of $5 million" and "an injunction ordering defendants to remove all defamatory posts from social media and to issue apologies to plaintiffs, and prohibiting defendants from publishing any future statements about plaintiffs whether written or verbal."

The court reversed the trial court's decision allowing pseudonymity to the Does (no-one objected to the pseudonymity of the Smiths):

The right of public access to court proceedings is implicated when a party is allowed to proceed anonymously…. "Public access to court proceedings is essential to a functioning democracy." "[T]he public has an interest, in all civil cases, in observing and assessing the performance of its public judicial system, and that interest strongly supports a general right of access in ordinary civil cases," not merely those in which the public is a party, or which generate public concern. Public access to courtrooms in civil matters serves to:

"(i) demonstrate that justice is meted out fairly, thereby promoting public confidence in such governmental proceedings; (ii) provide a means by which citizens scrutinize and check the use and possible abuse of judicial power; and (iii) enhance the truthfinding function of the proceeding."

"If public court business is conducted in private, it becomes impossible to expose corruption, incompetence, inefficiency, prejudice, and favoritism. For this reason traditional Anglo-American jurisprudence distrusts secrecy in judicial proceedings and favors a policy of maximum public access to proceedings and records of judicial tribunals." "[W]hen individuals employ the public powers of state courts to accomplish private ends, … they do so in full knowledge of the possibly disadvantageous circumstance that the documents and records filed [therein] will be open to public inspection." … "[A] trial court is a public governmental institution. Litigants can certainly anticipate, upon submitting their disputes for resolution in a public court … that the proceedings in their case will be adjudicated in public." …

"[T]he right to access court proceedings necessarily includes the right to know the identity of the parties." … In Department of Fair Employment & Housing v. Superior Court (Cal. App. 2022), the court recognized the constitutional issues noted above and held that, before authorizing a civil litigant to use a pseudonym, the trial court must apply the "overriding interest test" outlined in NBC Subsidiary and California Rules of Court, rule 2.550(d)…. The court further held that "[i]n deciding the issue the court must bear in mind the critical importance of the public's right to access judicial proceedings. Outside of cases where anonymity is expressly permitted by statute, litigating by pseudonym should occur 'only in the rarest of circumstances.'" …

We agree with the Department of Fair Employment & Housing court that trial courts faced with a motion to proceed pseudonymously should apply the "overriding interest test" outlined [as to the sealing of court records] in NBC Subsidiary v. Superior Court (Cal. 1999) and California Rules of Court, rule 2.550(d)….

Courts in California have recognized at least two interests relevant here as potentially sufficient to allow for redaction of names. These are: first, maintaining privacy of highly sensitive and potentially embarrassing personal information [such as] … records revealing gender identity change … [and] medical and psychological records … and second, protecting against the risk of retaliatory harm…. A recurring theme in the caselaw is that a party's possible personal embarrassment, standing alone, does not justify concealing their identity from the public…. "An unsupported claim of reputational harm falls short of a compelling interest sufficient to overcome the strong First Amendment presumptive right of public access." …

We agree the allegations in the complaint pertain to highly sensitive and private matters: specifically, John's allegations he was wrongly accused of sexual misconduct while in high school; and Jane's allegations she was wrongly identified as a nonconsensual partner of John's during that time. Allegations concerning sexual conduct do fall into the category of highly sensitive and private matters, the more so because the parties were minors at the time.

But that is merely the first step in the overriding interest test. Next, the court must find that the interest of privacy in highly personal and sensitive matters overcomes the public's right of access. We conclude there is insufficient evidence to support the trial court's conclusion that it did. We take plaintiffs' contentions to the contrary one at a time.

First, there was no evidence of serious mental or physical harm that would occur to plaintiffs should their identity be revealed. To the extent the trial court concluded that a reasonable fear of one's employer learning about allegations of a private nature overcame the public's right of access, we disagree.

To state the obvious, the fear that a future employer might learn about the lawsuit through an Internet search is not the equivalent of a fear of violence to one's family members, deportation and arrest, violence, harassment and discrimination against transgender people, or violence against a witness in a murder case. Rather, the fear argued here is precisely the kind of reputational harm cases have routinely held is insufficient to allow a party to proceed anonymously…. "The allegations in defamation cases will very frequently involve statements that, if taken to be true, could embarrass plaintiffs or cause them reputation harm. This does not come close to justifying anonymity, however …." …

[F]ear of harm to one's reputation applies to a great number of cases, including virtually any defamation case. By definition, a claim for defamation involves an allegedly harmful falsehood that has been published to third parties. This justification, when (as here) unsupported by more than arguments based on unproven allegations, would swallow the rule and cannot be squared with the judicial refrain that proceeding under a pseudonym should only be allowed in the "rare" case.

Second, plaintiffs here were not minors at the time they filed this lawsuit. While they were minors for a portion of the underlying events, they are not anymore….

Third, the trial court's conclusion that knowledge of the events was "confined to a relatively small number of people" is unsupported by the record. [Details omitted. -EV] … Even if the trial court had taken such evidence, this factor is at best neutral…. [P]arties generally lose their reasonable expectations of privacy when they file a civil lawsuit….

Fourth, this is a case against two private individuals, not against a school or a government entity, such as in the particularly confidential Title IX context.

Fifth, there is no basis to proceed anonymously because the injury litigated against would be incurred as a result of the disclosure of the party's identity. The cases that have recognized such an interest are cases seeking to enjoin a disclosure of private facts. Here, by contrast, the plaintiffs are suing for damages based on comments which have already been made. To hold otherwise would effectively permit all defamation plaintiffs to proceed by way of pseudonym.

Sixth, that defendants already know plaintiffs' identities is, at best, neutral in this case ….

Seventh, we reject plaintiffs' argument that requiring them to use their real names would discourage "similarly situated" litigants from bringing defamation cases…. To accept such a rationale here would equip all defamation plaintiffs with the same argument.

To the contrary, courts have expressed a reluctance to allow defamation plaintiffs the option to remain anonymous until they know the outcome of their case…. [P]laintiffs claim to have sued to "disassociate their names" from damaging and untrue allegations. Yet they argue if their true identities became known, any ultimate success in the matter would be negated by disclosure of their names. As other courts have noted, this rationale does not make sense in the context of a plaintiff who has filed a defamation claim. (See Doe v. Doe (4th Cir. 2023) ["we fail to see how [the plaintiff] can clear his name through this lawsuit without identifying himself"].) …

The trial court concluded that since the public interest in the identity of the parties is "likely nominal at best," the public interest was overridden by plaintiffs' privacy interests…. [But th]e public has a fundamental interest in knowing the identities of parties to litigation in public fora. Such information is essential to monitoring public proceedings for a host of evils, including corruption, incompetence, inefficiency, prejudice, and favoritism…. "Identifying the parties to the proceeding is an important dimension of publicness. The people have a right to know who is using their courts." …

The trial court understandably credited the privacy concerns of plaintiffs, particularly given they were agreeable to having defendants' names kept out of the pleadings as well. But there is a third stakeholder whenever a party seeks to close any portion of a court record, whether or not represented by a group like the [First Amendment Coalition, which brought the appeal]: the public. Just as a court cannot seal documents solely because both parties agree, a court must be vigilant to protect the public's right of access even when the parties themselves agree to proceed pseudonymously.

Disclosure: I briefed and argued the case on behalf of the First Amendment Coalition. Thanks to then-Stanford-law-students Benjamin Diamond Wofford, Olivia Morello, and Samuel Himmelfarb, who worked on earlier phases of the case.

The post California Appellate Court Generally Rejects Pseudonymity for Defamation Plaintiffs (Including in #TheyLied Sexual Assault Allegation Cases) appeared first on Reason.com.

[David Bernstein] Attempts to Redefine Genocide are Undermining the Concept

[Note: I'm working on a book chapter with a similar theme, here is an attempt to distill it into blog post-size.]

As South Africa hosts its first ever G20 Summit, its continued pursuit of Israel under the false guise of genocide is resulting in growing diplomatic pushback. The United States and Argentina have announced they will not be attending, yet Pretoria continues to weaponize the very term "genocide" to suit its political objectives.

South Africa's pursuit of phony genocide charges forms part of a broader campaign aimed at delegitimizing and constraining Israel as it fights a multi-front war against actors openly committed to its destruction. Some are motivated by hostility to Israel, but others see an opportunity: by capitalizing on intense antagonism toward Israel within academic and NGO circles, they can advance a long-standing project of sharply restricting democracies' ability to fight non-state actors, and particularly terrorist organizations and militias. Israel thus becomes the canary in the coal mine for efforts to effectively outlaw military operations against terrorist groups embedded among civilians.

At the heart of these efforts is a misuse of international humanitarian law, a body of rules created not to restrain whichever side one dislikes, but to impose neutral, equal obligations on all parties to a conflict. IHL was never intended as a political weapon or a pacifistic tool, but as a universal framework meant to protect civilians while recognizing the realities of warfare. This neutrality is its core strength: once the framework is selectively wielded against only one side, incentives for compliance collapse.

The 1948 Genocide Convention sought to establish clear, objective standards for the crime of genocide—above all the requirement of a specific intent to destroy a protected group. Standards like this were crafted to prevent future atrocities like the Holocaust, not to be repurposed for partisan advocacy, whether rooted in intense anti-Zionism or in a strong presumption against the use of military force by Western democracies.

The current effort to redefine these standards is nowhere more visible than in South Africa's case against Israel at the International Court of Justice. The legal theory advanced by South Africa and its supporters drains the term "genocide" of its established meaning, creating dangerous precedents for future conflicts.

The Convention requires evidence of special intent — demonstrated through direct proof, or, absent that, inference only when such intent is the only reasonable conclusion. But Israel's decidedly non-genocidal stated goals in the war – to release the hostages and destroy Hamas – are supported by its conduct throughout the war.

Israel's actions, including its acceptance of ceasefire terms, its prior openness to negotiated political arrangements, and its extensive facilitation of humanitarian access to Gaza all support this goal and contradict the notion of genocidal intent. No State that facilitates vital humanitarian corridors and extensive aid entry (to date well over two million tons) or engages in sustained efforts to limit civilian harm could be, as the only reasonable conclusion, pursuing the physical destruction of a population.

One element of the Convention that South Africa emphasizes is the alleged deliberate infliction of conditions calculated to destroy the Palestinian population. The humanitarian situation in Gaza is unquestionably tragic—but Hamas, not Israel, bears primary responsibility.

And crucially, contrary to certain claims, international law does not oblige a State to provide goods it knows will be seized by enemy fighters, so long as good-faith efforts are taken to ensure civilians can receive help through alternative channels that actually reach them.

Nevertheless, Israel continued to enable massive flows of aid into Gaza throughout the conflict, even as Hamas repeatedly looted, diverted, or resold that aid, including stealing from UN warehouses. By mid-2025, UN data showed tens of thousands of tons of humanitarian assistance had been intercepted by Hamas. Israel's persistence in facilitating aid despite this pattern of theft and operational risk is fundamentally inconsistent with any claim of genocidal intent and goes well beyond what IHL requires of a state fighting an adversary embedded among civilians.

Israel's conduct—warning civilians before military action, adjusting operations to minimize harm, and confronting an enemy that intentionally situates military assets under civilian sites such as hospitals and schools—reflects an approach to urban warfare that many militaries struggle even to approximate.

Its civilian-casualty rate remains among the lowest of any comparable conflict, an especially notable fact given the extreme density of the environment and the absence of any fully safe haven outside the conflict zone. While casualty numbers alone cannot determine legality, sustained efforts to reduce civilian harm cut directly against the charge that Israel seeks the group's destruction.

The attempt to stretch the definition of genocide to encompass any high-intensity urban warfare causing civilian suffering would not protect civilians. Instead, it would hand terrorist groups a blueprint: embed deeper within civilian populations, ensure any military response causes significant civilian casualties, and weaponize legal institutions to delegitimize self-defense.

These efforts to rewrite international law to suit a political campaign against Israel would, if allowed, weaken the Genocide Convention itself. A diluted genocide standard does not protect vulnerable groups; it renders the Convention less able to confront real genocidal campaigns when they arise.

The Convention must be preserved as a principled, objective standard—not reshaped on the fly to serve particular political objectives.

The post Attempts to Redefine Genocide are Undermining the Concept appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Firing Teacher for Mentioning Racial Epithets in "Cultural Diversity" Class May Violate Connecticut Constitution

From a decision earlier this month in Byrd v. Middletown Bd. of Ed., by Connecticut trial court Judge Sheila Ozalis; Byrd was a teacher who "was teaching a lesson on 'recognizing racial epithets' as a part of the Cultural Diversity Curriculum at Beman Middle School":

The plaintiff alleges that from 1997–2021, she taught eighth grade students about the District's Cultural Diversity Curriculum, along with other units in the eighth grade Health Curriculum, including internet safety, self-esteem, romantic relationships, drug education, and career education. The plaintiff alleges that Equity Training in recent years for the teachers included the idea that teachers should be challenging students about uncomfortable topics because if people stay in their comfort zone, there is no new growth.

The plaintiff alleges that while employed by the Middletown School District for over twenty years, she presented the same Cultural Diversity Curriculum at Beman Middle School to eighth graders without complaint. She also alleges that this curriculum has been used by the District for nearly ten years, was posted on its website, approved by the Defendant, and was reviewed by the District in the summer of 2021 without any changes made. As a part of the Cultural Diversity Curriculum, the Plaintiff spoke to students about the diversity within their own community. "Lesson #3" of the published and approved curriculum describes the concept of the lesson as "recognizing racial epithets" and notes the discussion of racial epithets as part of the lesson plan.

The plaintiff alleges that during this lesson, she would introduce vocabulary and examples of attitudes towards distinct groups, including language demonstrating stereotypical thinking and hostility to a specific group or prejudices about particular groups and their alleged predilections and behaviors. She alleges that her open discussion of racial and ethnic stereotypes and slurs had been an established part of the posted Cultural Diversity Curriculum for over ten years and that it was the Plaintiff's practice to verbalize and specifically name the racial slurs that would be discussed during the lesson and ask her students if they had heard that specific slur before.

The plaintiff alleges that she would discuss each word's meaning and history and ask students why racial slurs were used to put people down and why people enjoy making jokes about and ridiculing minority groups. The Plaintiff would focus on the group targeted by the words and how the words hurt members of that group to assist in helping students make better decisions in life, including in their use of language, by providing a better understanding of the words, their origins, and society's pernicious use of them. The Plaintiff also alleges that she sought to make the students better citizens in a multicultural world.

Some of this language could be offensive and difficult for students to discuss. The Plaintiff alleges that she would tell students that they could use her "emergency pass" if they wished to leave a lesson because of any upset regarding the words to be discussed. If the student wanted to, they could even bring a friend with them when they took the emergency pass. The Plaintiff would then follow up with that student during or at the end of class to see if further resources were needed. The plaintiff alleges that nevertheless, this frank discussion about the realities of prejudice and the language utilized by some members of society at large was meant to assist students in recognizing and grappling with the prejudiced language and hostility that they will confront in life, and to make students more conscious of the prejudice and learned behavior existing in their own environments.

On October 29, 2021, the Plaintiff presented the "recognizing racial epithets" lesson to her third class of the day—the first two having occurred without incident—and began her discussion of racial slurs as usual by expressly saying the slurs aloud. The plaintiff alleges that one of the words she identified was "nigger," which she described as one of the most derogatory and offensive slurs that was historically used to depict African Americans as ignorant and uneducated. She alleges that on this day with this particular group, some students objected and said she should not be saying such language aloud, turned around in their chairs out of discomfort, and even videotaped the class discussion…..

Plaintiff alleges she was threatened with firing, and accepted a demotion to avoid being fired. She sued, claiming this violated the Connecticut Constitution's free speech clause, which has been interpreted as more protective than the First Amendment as to employees' speech that's part of their jobs (for a case finding no protection under the First Amendment in a similar factual situation involving K-12 teaching, see Brown v. Chicago Bd. of Educ. (7th Cir. 2016)):

Departing from the limitations imposed by Garcetti v. Ceballos (2006), in Trusz v. UBS Realty Investors, LLC, our Supreme Court held that employees speaking pursuant to official duties have free speech rights. This decision relies heavily on the express language of the Connecticut Constitution. Article first, § 4, of the Connecticut Constitution which provides that "[e]very citizen may freely speak, write and publish his sentiments on all subjects, being responsible for the abuse of that liberty." "By contrast, the first amendment does not include language protecting free speech on all subjects." ….

To narrow the scope of protected employee speech, the Trusz Court adopted a modified Pickering/Connick balancing test such that "only comment on official dishonesty, deliberately unconstitutional action, other serious wrongdoing, or threats to health and safety can weigh out in an employee's favor when an employee is speaking pursuant to official job duties. Nonetheless, "speech pursuant to an employee's official duties regarding, for example, a mere policy disagreement with the employer would not be protected, even if it pertained to a matter of public concern and had little effect on a legitimate employer interest." "The problem in any case is to arrive at a balance between the interests of the [employee], as a citizen, in commenting upon matters of public concern and the interest of the State, as an employer, in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employees." Pickering v. Board of Education (1968). Thus, "[i]t is only when the employee's speech is on a matter of public concern and implicates an employer's official dishonesty … other serious wrongdoing, or threats to health and safety … that the speech trumps the employer's right to control its own employees and policies."

The first step in evaluating employee speech is to determine whether the employee is speaking on a matter of public concern. Connick v. Myers (1983). "An employee's speech addresses a matter of public concern when the speech can be fairly considered as relating to any matter of political, social, or other concern to the community …." … The Appellate Court has held that racial discrimination against a fellow employee is a matter of public concern….

The inflammatory nature of racial slurs has long been recognized. In evaluating a hostile work environment claim based on sex, the Supreme Court explained the "pervasiveness" requirement by analogizing to racial animus and noted that "[t]here must be more than a few isolated incidents of racial enmity …. Thus, whether racial slurs constitute a hostile work environment typically depends upon the quantity, frequency, and severity of those slurs …." Nowhere have our courts made a stronger rebuke of racial slurs than in State v. Liebenguth (2020).

The Supreme Court in that case contextualized fighting words cases by noting at the outset that "there are no per se fighting words …. Consequently, whether words are fighting words necessarily will depend on the particular circumstances of their utterance." The Liebenguth Court recounted that "[w]ith respect to the language at issue in the present case, the defendant, who is white, uttered the words fucking niggers to [parking enforcement officer] McCargo, an African-American person, thereby asserting his own perceived racial dominance and superiority over McCargo with the obvious intent of denigrating and stigmatizing him. When used in that way, [i]t is beyond question that the use of the word nigger is highly offensive and demeaning, evoking a history of racial violence, brutality, and subordination."

The Supreme Court spoke with disapprobation on the use of the word "nigger" and stated that "[n]ot only is the word 'nigger' undoubtedly the most hateful and inflammatory racial slur in the contemporary American lexicon … but it is probably the single most offensive word in the English language." Ultimately, the Supreme Court held that the defendant's use of the word "nigger" in combination with his conduct and other derogatory language was likely to provoke a violent reaction and, therefore, his speech was unprotected fighting words. Thus, when the word "nigger" is used in certain contexts, it can be a threat to safety.

The federal government has also recognized the threat of racism. In 2021, CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky, a physician and scientist, made a media statement and "declared racism a serious public health threat." …

Words evoke racism not because of the letters on the page or their phonetics, but because of the manner in which they are used. Indeed, when divorced from their context, words can be devoid of meaning and lack clarity. Our Supreme Court recognized that context matters in stating that "there are no per se fighting words because words that are likely to provoke an immediate, violent response when uttered under one set of circumstances may not be likely to trigger such a response when spoken in the context of a different factual scenario."

Like our Supreme Court, the Garcetti Court also left open the potential for broader speech protection in certain scenarios when it noted that "[t]here is some argument that expression related to academic scholarship or classroom instruction implicates additional constitutional interests that are not fully accounted for by this Court's customary employee-speech jurisprudence." In fact, some courts have held that the utterance of the word "nigger" in the university setting for instructional purposes is protected. See Hardy v. Jefferson Community College (6th Cir. 2001) (where an adjunct instructor's use of the word "nigger" in a lecture on language and social constructivism was protected); Sullivan v. Ohio State University (S.D. Ohio 2025) (professor's use of the word "nigger" in his "Crucial Conversations" course to teach students how to engage productively in racially charged conversations was a matter of public concern).

And the court concluded that plaintiff's claim could therefore go on:

Plaintiff alleges that she did not direct racial slurs at her students in a derogatory manner, but rather she was saying them aloud to instruct students on how to avoid a potential threat created by using those words in public. During a Health class in the 2021–22 school year, taking place amid the backdrop of the Liebenguth decision and the CDC declaration, the Plaintiff alleges that she was acting within the scope of her employment and pursuant to the Defendant's approval when she taught her students a valuable lesson on a matter of public concern: the presence of racism and racially charged language in society today. Thus, the Plaintiff's speech touched upon a threat to health and safety.

Although traditionally a board of education's discretion over the curriculum has trumped the speech rights of public school teachers in primary and secondary education, here, the Plaintiff alleges that she was teaching the Cultural Diversity Curriculum in the manner prescribed by the Defendant. There can be no "mere policy disagreement" when the Defendant itself has adopted the curriculum for the past ten years, including the lesson on "recognizing racial epithets." Like she had in years past, the Plaintiff alleges she simply taught her students to recognize racial epithets and prepared them to confront such words outside the classroom in their communities. She also alleges that by the end of the day, she was placed on administrative leave and threatened with termination. As a result, the Plaintiff has adequately alleged that she was threatened with discharge on account of her constitutionally protected speech ….

This isn't part of the legal test, but the court's analysis here tracks the Connecticut Supreme Court's approach in Liebenguth: That court concluded that defendant could be prosecuted on a "fighting words" theory for using the word "nigger" as an epithet, but the court itself quoted the word over 50 times in discussing the subject, and the word was also quoted 6 times in oral argument.

Lewis Chimes represents plaintiff.

The post Firing Teacher for Mentioning Racial Epithets in "Cultural Diversity" Class May Violate Connecticut Constitution appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: November 21, 1926

11/21/1926: Justice Joseph McKenna died.

Justice Joseph McKenna

Justice Joseph McKennaThe post Today in Supreme Court History: November 21, 1926 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Open Thread

[What’s on your mind?]

The post Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

November 20, 2025

[Ilya Somin] US News and World Report Article Urging Colleges to Reject Trump's "Compact" With Higher Education

[I coauthored the article with four other legal scholars from across the political spectrum.]

Steven Cukrov | Dreamstime.com

Steven Cukrov | Dreamstime.com US News and World Report just published an op ed I coauthored with four other legal scholars entitled "Colleges Must Reject Trump's 'Compact' To Protect Our Democracy." The four other authors are Rick Garnett (Notre Dame), Serena Mayeri (University of Pennsylvania), Amanda Shanor (University of Pennsylvania), and Alexander "Sasha" Volokh (Emory, also my co-blogger here at the Volokh Conspiracy).

To put it mildly, the five of us have widely divergent views on political and legal issues. Serena Mayeri and Amanda Shanor are prominent progressive constitutional law scholars. Rick Garnett is a leading conservative constitutional law and law and religion specialist. Sasha Volokh and I are libertarians (him perhaps somewhat more radical than me).

But we all agree colleges should reject the "compact" for both constitutional and other reasons. Here's an excerpt from the article:

We teach law at four different U.S. universities and come from a range of political and legal perspectives. But we all agree that universities should vehemently and unanimously reject the Trump administration's "Compact for Academic Excellence in Higher Education."

The federal Department of Education first sent this compact to nine universities in October, stating that signatories would receive preferential consideration for federal grants. The compact itself conditions benefits such as federal contracts, tax-exempt status, student loans and student visas on the adoption of various government prescriptions for admissions, hiring, tuition, curriculum, discipline, international student enrollment, grading and free speech….

Universities that have balked at – or outright rejected – the compact are correct to do so. The administration's proposal contains five fundamental causes for alarm:

First, the compact tramples upon the constitutional rights that allow us to debate and disagree without fearing reprisals from our universities or from the government….

Second, the compact amounts to a federal takeover of private institutions and state entities. It threatens to withdraw federal benefits from any university that does not submit to the federal government's demands. Such imposed ideological uniformity would undermine the competition that spurs innovation and empowers students and faculty to "vote with their feet" for the schools that best meet their needs.

Moreover, the compact's approach to federal funding is unlawful and unconstitutional: Conditions on federal grants to state governments, including state universities, must be clearly stated in advance, related to the funds' purposes and not unduly coercive….

Third, the compact violates the constitutional separation of powers. Under the Constitution, Congress, not the executive, wields the power of the purse. An executive agency – here, the Department of Education – cannot withhold funds or place new conditions on monies Congress has allocated without clear and explicit legislative authorization….

Fourth, the compact places universities in a dangerous financial position, facing draconian penalties without due process – or any process at all. The compact authorizes the government and private donors to claw back federal dollars whenever federal officials are displeased with a university's actions. Signatories to this agreement would forfeit their autonomy and the fundamental freedoms of their community members….

Finally, the compact is riddled with internal inconsistencies that render it both incoherent and dangerous. The agreement claims to value "merit" in higher education, but offers preferential consideration for federal grant money based on universities' adherence to government-mandated ideology rather than scientific excellence. It prohibits discrimination based on "political ideology" while requiring special protection for "conservative ideas," and exclusion of foreign students based on their speech and political views.

Some of the issues raised in the US News article are addressed more fully in my forthcoming book chapter, "How Speech-Based Immigration Restrictions Threaten Academic Freedom," Academic Freedom in the Era of Trump, Lee Bollinger and Geoffrey Stone, eds. (Oxford University Press, forthcoming). Ideological and speech restrictions on foreign students are a major element of Trump's Compact.

As we note in the US News article, many prominent schools have already rejected the Compact, including eight of the nine to whom it was initially offered. But a few less well-known institutions have expressed willingness to join it. We hope no more do so.

For those keeping score, I have, in the past, extensively criticized constitutionally dubious higher education policies advanced by Democratic administrations, such as racial preferences in admissions and Biden's massive (and illegal) student loan forgiveness program.

The post US News and World Report Article Urging Colleges to Reject Trump's "Compact" With Higher Education appeared first on Reason.com.

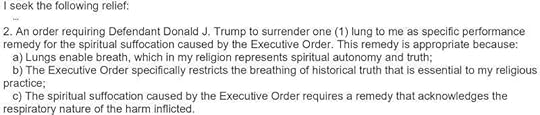

[Eugene Volokh] Lawsuit Challenging Trump Executive Order on "Divisive Race-Centered Ideology"—and Seeking Trump's Lung—Dismissed

[An excerpt from the plaintiff's Complaint.]

[An excerpt from the plaintiff's Complaint.] From Jeanpierre v. Trump, decided Tuesday by Magistrate Judge Daphne Oberg (D. Utah):

Mr. Jeanpierre is the founder of a religious organization called the Black Flag….He claims President Trump's Executive Order 14253 violates his religious freedoms under the First Amendment and the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA),as well as Article 18 of the United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The Black Flag is a tax-exempt religious organization with various tenets. The central tenet: Mr. Jeanpierre can do whatever he "feel[s] like doing." A "Principle of Autonomy" grants him "autonomy of mind, body, spirit, emotion, and execution of will regardless of opinion of any and all other individual(s), entity, or entities." The Black Flag prohibits prejudice and discrimination "against any member, guest, or affiliated party based on race, color, gender, sexual orientation, national origin, age, disability, or socioeconomic status." The religion "mandates recognition of systemic racism, inequity, and historical injustice," imposes "a religious duty to actively engage in dismantling systems of oppression," and requires "active engagement in outreach programs and protective measures" for marginalized or vulnerable groups.

On March 27, 2025, President Trump issued Executive Order 14253, titled "Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History." As characterized in the complaint, the executive order "directs federal agencies to remove … 'divisive race-centered ideology' from the Smithsonian Institution and to restore monuments that have been 'removed or changed to perpetuate a false reconstruction of American history.'" The order refers to a historical revisionist movement which "seeks to undermine the remarkable achievements of the United States by casting its founding principles and historical milestones in a negative light."

Mr. Jeanpierre claims the order "opposes narratives that present American history as 'inherently racist, sexist, oppressive, or otherwise irredeemably flawed.'" It "prohibits 'exhibits or programs that degrade shared American values, divide Americans by race, or promote ideologies inconsistent with Federal law,' and targets changes made to historical presentations since January 1, 2020." And it "directs the Department of the Interior to ensure that monuments and memorials do not contain content that 'inappropriately disparage Americans past or living (including persons living in colonial times).'"

According to Mr. Jeanpierre, this executive order "effectively establishes a state-sponsored religious doctrine of American historical exceptionalism" and, as a result, is "a direct attack on the foundational tenets of [his] sincerely held religious beliefs." He alleges the order prevents Mr. Jeanpierre "from exercising his religious autonomy to perceive and interpret history according to his religious conscience." He alleges the order's "prohibition against depicting American history as 'inherently racist, sexist, oppressive, or otherwise irredeemably flawed'" impedes his "religious mandate to identify and confront … historical realities" and interferes with his "religious practice of acknowledging and addressing systemic racism" by "imposing a sanitized historical narrative that contradicts [his] religious understanding of reality."

The "restrictions on historical presentations," according to Mr. Jeanpierre, force "compliance with a historical narrative that [he] religiously believes causes harm to marginalized communities" and "spiritual suffocation and respiratory distress to [his] religion by restricting the free breath of historical truth." Finally, Mr. Jeanpierre alleges the executive order's imposed historical doctrine compels him "to violate his religious tenants regarding autonomy, truth-telling, and confrontation of systemic inequity," forcing him "to choose between adherence to his religious principles and compliance with federal law."

Mr. Jeanpierre seeks injunctive, declaratory, and monetary relief, as well as "specific performance." In particular, he requests an order permanently enjoining Executive Order 14253 and declaring it violative of the First Amendment and RFRA—and a finding that it constitutes religious violence under international law. He requests $666 in "compensatory damages" and "attorney's fees and costs." And he seeks an order requiring President Trump "to surrender one (1) lung" to him as specific performance "for the spiritual suffocation caused by the Executive Order"—or, in the alternative, a specifically orchestrated apology delivered by President Trump before international news media….

The Magistrate Judge was required to screen the complaint for legal sufficiency, since Jeanpierre sought to bring the claim without paying the filing fee. And she concluded the complaint "fails to state a plausible claim for relief" for various reasons, including:

Mr. Jeanpierre fails to assert facts showing the executive order substantially burdens his exercise of religion. He alleges the order "imposes a sanitized historical narrative" that prohibits "depicting American history as 'inherently racist, sexist, oppressive, or otherwise irredeemably flawed.'" And he broadly alleges this prevents him "from exercising his religious autonomy to perceive and interpret history," impedes his religious practice of identifying and confronting "historical realities" and "acknowledging and addressing systemic racism," forces him to comply with an incorrect historical narrative, compels him "to violate his religious tenants regarding autonomy, truth-telling, and confrontation of systemic inequity," and forces him "to choose between adherence to his religious principles and compliance with federal law."

But the executive order, as described in the complaint, does not demand any conduct from Mr. Jeanpierre or impose any consequence for his religious beliefs. It orders federal agencies to remove race-centered ideology from the Smithsonian Institution and to restore public monuments, according to President Trump's historical narrative that the country's achievements, principles, and milestones are being undermined and cast in a negative light. Mr. Jeanpierre does not assert he was made to alter his religious behavior in some way because of this order. He does not even allege he visited the Smithsonian or any other monument affected by the order. And, even if he has, the order demands nothing from him. It includes no provision requiring or coercing him to accept the executive order's narrative as truth. Mr. Jeanpierre is free to disagree without any consequence. Accordingly, the complaint fails to state a claim under RFRA.

Third, Mr. Jeanpierre also fails to state a claim that the executive order violates his religious freedoms under the First Amendment. Among other things, the First Amendment contains an Establishment Clause and a Free Exercise Clause: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof …." Mr. Jeanpierre does not state a claim under either clause.

The Establishment Clause prohibits the government from "mak[ing] a religious observance compulsory," "coerc[ing] anyone to attend church," or forcing individuals "to engage in a formal religious exercise." The executive order does none of that—it is entirely secular. Mr. Jeanpierre does not allege he has been forced to attend or engage in any religious observance—or even that he has been forced to visit the Smithsonian or any other monument affected by the order.

The Free Exercise Clause prohibits the government from burdening "sincere religious practice pursuant to a policy that is not neutral or generally applicable." But Mr. Jeanpierre does not allege the executive order burdens his religious practice—that it prevents him from holding his own beliefs or compels him to alter his personal religious behavior. Moreover, the executive order is neutral and generally applicable. It has no religious objectives. It does not target religion. On its face, it has nothing to do with religion. In effect, Mr. Jeanpierre's free-exercise claim demands that President Trump refrain from implementing a religiously neutral, historical narrative at the Smithsonian and other monuments that is contrary to the Black Flag's religious understanding of history. The First Amendment has never been interpreted to "require the Government itself to behave in ways that the individual believes will further his or her spiritual development." For these reasons, the complaint fails to state a claim under either the Establishment Clause or the Free Exercise Clause.

Finally, Mr. Jeanpierre fails to state a claim that the executive order violates Article 18 of the United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a non-binding declaration that provides no private rights of action….

The post Lawsuit Challenging Trump Executive Order on "Divisive Race-Centered Ideology"—and Seeking Trump's Lung—Dismissed appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Lawyer's "Repeated Claims That the Spurious Citations Resulted from Clerical Errors Unrelated to the Use of Generative AI Are Not Credible"

From Monday's opinion by Justice Frank Menetrez, joined by Justices Richard Fields and Michael Raphael, in Schlichter v. Kennedy:

Grotke's approach differs from those taken by the attorneys in Noland and Alvarez [two previous cases involving hallucinated citations]. Grotke has not admitted that the Writ and the AOB [Appellant's Opening Brief] contain hallucinated citations that were produced by generative AI. Grotke admitted that he used AI in some fashion when preparing the AOB and that it was "possible" that he used AI in some fashion when preparing the Writ. But he maintains that the four spurious citations resulted from clerical error and that he intended to cite the actually existing cases for the propositions described in the declaration that he filed in response to our order to show cause. We find that Grotke's claims are not credible.

It is difficult to understand how Grotke's four spurious citations could possibly be mere clerical errors, and Grotke has not intelligibly explained how it would be possible. The spurious citations do not involve the mere omission or addition or transposition of one or several digits. Rather, all four spurious citations are completely different from the correct citations for the actually existing cases that have those case names. Grotke's spurious citations bear the hallmarks of hallucinated citations produced by generative AI. "[H]allucinated cases look like real cases. They are identified by a case name, a citation to a reporter, the name of a district or appellate court, and the year of the decision. [Citation.] But, they are not real cases."

Grotke's claim that he intended to cite the actually existing cases is similarly lacking in credibility. The actually existing cases do not support the legal propositions for which Grotke provided the spurious citations in the Writ and the AOB. Consequently, it would make no sense for Grotke to claim that he intended to cite the actually existing cases to support those legal propositions. Grotke attempts to avoid that problem by claiming that he cited the four cases for various other legal propositions, which he describes in his declaration. But the attempt fails, because the legal propositions described in his declaration are not the legal propositions in the Writ and the AOB for which the spurious citations were provided as authority.

For all of these reasons, we conclude that Grotke's repeated claims that the spurious citations resulted from clerical errors unrelated to the use of generative AI are not credible.

Other parts of Grotke's response show a similar lack of candor and credibility. Grotke claimed in his declaration that the spurious citations "resulted from a breakdown in [his] citation-verification process during compilation from vLex." But Grotke admitted at the hearing that before receiving our order of September 19, 2025, he had never signed up for or had a membership on vLex but merely used it "on and off" or "here and there."

Insofar as Grotke claims that he did check the four cases—by searching for them either by case name or by volume and page number citation—before filing the Writ and the AOB, the claim is not credible. If Grotke had tried to check the cases by volume and page number citations, then he would have discovered that the cases do not exist. Grotke admits that is what happened when he searched for the cases in response to our order of September 19, 2025. And if Grotke had tried to check the cases by case names, then he would have discovered that the actually existing cases do not stand for the propositions for which he was citing them.

We agree with Noland and Alvarez that "attorneys must check every citation to make sure the case exists and the citations are correct. [Citation.] Attorneys should not cite cases for legal propositions different from those contained in the cases cited. [Citation.] And attorneys cannot delegate this responsibility to any form of technology; this is the responsibility of a competent attorney." As explained by Alvarez, "[h]onesty in dealing with the courts is of paramount importance, and misleading a judge is, regardless of motives, a serious offense."

For all of the foregoing reasons, we find that Grotke has failed to show cause why he should not be sanctioned for relying on fabricated legal authority in the Writ and the AOB…. [W]e issue a sanction in the amount of $1,750 to be paid by Grotke individually …. We direct the Clerk of this court to notify the State Bar of the sanctions against Grotke.

I e-mailed the lawyer to see if he had a response, and he said this:

The cases were real, not hallucinations, though I have seen AI hallucinate cases in the past. The cites were just mistaken as to where they were located, page number, volume, etc. I reviewed the cases and included them because they were relevant. I believed that I had the correct cites because they were relevant, but somewhere along the way, maybe AI being the cause, I obtained the wrong cites. As I explained to the court, if I knew exactly why they were incorrect, they would not have been submitted that way.

The post Lawyer's "Repeated Claims That the Spurious Citations Resulted from Clerical Errors Unrelated to the Use of Generative AI Are Not Credible" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Exclusion of Students for Justice in Palestine from U Missouri Homecoming Parade May Have Violated First Amendment

From Mizzou Students for Justice in Palestine v. Choi, decided earlier this month by Judge Stephen Bough (W.D. Mo.):

Plaintiff Mizzou Students for Justice in Palestine ("MSJP") is a registered student organization at the University of Missouri ("the University" or "MU"). MSJP is dedicated to advocating for Palestinian rights by raising "awareness on campus of the historical and ongoing injustices committed against Palestinians." MSJP has hosted dozens of events, including "marches, lectures, and panel discussions."

The University hosts an annual Homecoming Parade. In the fall of 2024, MSJP applied to be part of the Homecoming Parade for the first time. MSJP planned to perform a traditional Palestinian dance and pass out Palestinian sweets. It also planned on displaying signs that read "Ceasefire Now" and "Stop the Genocide." Dr. Choi is the Chancellor of MU. Although MSJP initially believed that its application to participate in the 2024 Homecoming Parade had been approved, Dr. Choi ultimately denied the application, citing concerns related to safety….

The Free Speech Clause restricts the government's regulation of private speech, but does not regulate government speech…. In determining whether "the government intends to speak for itself or to regulate private expression[,]" [this Court] … is driven by a case's context rather than the rote application of rigid factors [and looks to] … the history of expression at issue; the public's likely perception as to who (the government or a private person) is speaking; and the extent to which the government has actively shaped or controlled the expression." Shurtleff v. City of Boston (2022)….

[a.] History of Expression

Under the history of the expression at issue factor, the Court looks to both the specific history of the MU Homecoming Parade and homecoming parades in general. The Complaint alleges that "[t]he University of Missouri has hosted an annual homecoming celebration for over 100 years. The University's Homecoming Parade is one of the oldest homecoming traditions in the country, with some even touting it as the very first homecoming tradition by an American university" and that "[t]he Homecoming Parade has long been a place for the expression of political and social messages, including ones widely considered controversial or offensive."

The Complaint further alleges that "[t]he Homecoming Parade has welcomed political campaigns and activist groups of all kinds, including many that people would find controversial or offensive." Finally, the Complaint alleges that "[e]ntities across the spectrum—from local businesses to student organizations—participated in the [2024] Homecoming Parade."

These allegations are sufficient to tilt the history of expression factor in MSJP's favor. The allegations of diverse participation stand in contrast with government-sponsored military parades, for example, which have a long tradition of communicating a more singular message to "celebrate [a nation's] militaries." Here, there does not appear to be a singular message as the Homecoming Parade has "long been a place for the expression of political and social messages[.]" Ultimately, the allegations do not show that the Homecoming Parade has "long conveyed important messages about the government." …

[Some more details from an earlier decision in the case: —ed.]

{[T]he MU Homecoming Parade … has a history of welcoming a diverse group of parade entries …, the Legion of Black Collegians led a march against racial injustices during the Homecoming Parade. In 2023, a Columbia resident described the Homecoming Parade participants to include a former city councilwoman in a suffragette costume, an LGBTQ group with dance music and a drag queen, and then lieutenant-governor, Republican Mike Kehoe, with "a crew politicking for his run for governor." In 2024, parade-walkers held signs advocating for a "yes" vote on Amendment 3 (a ballot measure to protect the right to abortion) and for national political candidates.

At the hearing, Dr. Choi and McCubbin stated that MU's Homecoming Parade has historically had campaigners for public office, student political organizations with opposing viewpoints, for-profit sponsors, non-profit organizations, and student affinity groups. Further, when the Court asked McCubbin whether the University had endorsed past political floats, he answered "no."}

[ii.] Public's Likely Perception

Under the public-perception factor, the Court considers whether, taking the alleged facts as true, the public would perceive the Homecoming Parade as an expression of governmental speech. As provided above, the Complaint provides that the Homecoming Parade has traditionally accepted a wide variety of participants including those with conflicting political views. For example, in the 2024 Homecoming Parade, examples of participants included "pro-choice and pro-life groups[,]" "a fraternity riding a truck while waiving 'TRUMP' and 'MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN' flags[,]" "the Mid-Missouri Pride Fest[,]" and "the league of Women Voters[.]"

[Some more details from an earlier decision in the case, which discussed the slightly different 2025 policy, rather than the 2024 policy that is being challenged in the broader excerpt I quote:—ed.]

{While the Parade Policy prohibits active campaigning this year, it still features a diverse mix of "invited participants" such as the Oscar Mayer Wienermobile and elected officials, neither of which are explicitly listed on the Parade Policy. The parade will also feature "paid sponsors" such as "HotBox Cookies," and community organizations such as "Columbia Christian Academy" and "Columbia Youth Lacrosse." The public does not tend to view MU as endorsing a sitting congressman, the Oscar Mayer Weinermobile, or a private Christian school just because they appear in its Homecoming Parade.}

Based on the allegations in the Complaint, the Court finds that the public would not "tend to view" the Homecoming Parade as the government speaking because the public seems unlikely to view the parade as "conveying some message" on the government's behalf. These allegations are sufficient to show that MU is not expressing a coherent governmental message. Indeed, if MU was expressing a message, given the variety of participants, it would be one that is "babbling prodigiously and incoherently." Matal v. Tam (2017) (concluding that if trademarks registered by the Patent and Trademark Office were government speech, the government would be "unashamedly endorsing a vast array of commercial products and services").

Finally, contrary to Dr. Choi's argument that "[a] reasonable observer at the parade would naturally conclude that the University is the speaker, since the University obtains the permit, funds the event, sets the theme, and orchestrates the proceedings[,]" those administrative acts, standing alone, do not transform private speech into government speech….

[iii.] The Extent to which the University has Shaped or Controlled the Expression

In assessing the extent to which the government has shaped or controlled the expression of the Homecoming Parade, the Court considers the role Dr. Choi plays in the 2024 Homecoming Parade. The Complaint alleges that "[a] University of Missouri official told MSJP leadership that its application would be subjected to a unique review process. Unlike every other student organization, Chancellor Choi had the final say on whether MSJP would be allowed to participate in the [2024] Homecoming Parade." These allegations are insufficient to tilt this factor in favor of MU as "the mere existence of a review process with approval authority is insufficient by itself to transform private speech into government speech."

Moreover, the Complaint's assertion that Dr. Choi had final authority over MSJP's participation—"unlike every other student organization"—suggests that he did not exercise such control over any other organization's message. Consequently, Dr. Choi has not "actively exercised" any authority to shape the message of the Homecoming Parade. Walker v. Sons of Confederate Veterans (2015) (noting that the Texas Department of Motor Vehicles Board had "rejected at least a dozen proposed [license plate] designs.")….

The court therefore concluded that the Parade was either a limited or unlimited designated public forum, that viewpoint discrimination was forbidden in either forum, and that the plaintiffs had adequately alleged such viewpoint discrimination:

The 2024 Homecoming Parade featured a wide array of participants expressing diverse and sometimes conflicting viewpoints, yet MSJP was the only group excluded from participation. Accordingly, the Court agrees with MSJP that the Complaint plausibly alleges that "MSJP's exclusion was not content-neutral," as "the only viewpoint barred from expression was one in support of Palestinians." …

The Complaint alleges that Dr. Choi "required of MSJP what [he] did not require of other student organizations—to explain in painstaking detail all of their plans for the [2024] Homecoming Parade." Dr. Choi also allegedly requested that MSJP "refrain from displaying [a] 'Stop the Genocide' [sign.]" Finally, after denying MSJP's application, another student group allegedly agreed to carry the Palestinian flag, but Dr. Choi "forbade them from holding the Palestinian flag unless the group also held the Israeli flag."

These allegations demonstrate that Dr. Choi subjected MSJP to a "unique scrutiny" and are sufficient to show that the exclusion was motivated by MSJP's viewpoint on Palestine and Israel….

And the court concluded that plaintiff's allegations, if shown, would show a violation of a clearly established constitutional right, so defendants couldn't claim qualified immunity.

An earlier decision granting a preliminary injunction concluded that plaintiffs had not only adequately alleged a First Amendment violation as to the 2024 parade denial, but that they were also likely to succeed on the merits as to the planned exclusion of the group from the 2025 parade.

Ahmad Kaki, Gadeir Abbas, and Lena F. Masri (CAIR Legal Defense Fund), C. Kevin Baldwin, Eric E. Vernon, and Sylvia Alejandra Hernandez (Baldwin & Vernon), and Benjamin J. Wilson and Lisa S. Hoppenjans (Washington University School of Law, First Amendment Clinic) represent plaintiff.

The post Exclusion of Students for Justice in Palestine from U Missouri Homecoming Parade May Have Violated First Amendment appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers