Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 9

November 17, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] Judge Reverses Earlier Decision: Ex-Employee Can't Sue Planned Parenthood for Race Discrimination as a "Jane Doe"

[[UPDATE 11/17/2015 10:21 am: Sorry, post title originally accidentally omitted the "as a 'Jane Doe'" (which of course is what this decision is about, see below); I've revised the title to include it. My apologies!]]

In September, I wrote:

Ex-Employee Can Sue Planned Parenthood for Race Discrimination as a "Jane Doe," Because Abortion Providers Had Been Physically Attacked

Jane Doe, a former Planned Parenthood employee, is suing Planned Parenthood for race discrimination (and some related employment claims). Usually, employment claims are brought in the plaintiff's own name, at least unless there's some highly personal element (such as alleged sexual assault) that's part of the case.

But Doe asked to be pseudonymous—and was allowed to be pseudonymous—simply on the basis that her having worked at Planned Parenthood might expose her to criminal attack. On this theory, anyone who worked for an abortion clinic would likewise be entitled to pseudonymity in any case in which such employment would be disclosed. In principle, the same would be true as to any other occupation where there appears to be some general risk of violence due to public hostility—or for that matter any case where the person's political or religious views might expose them to some such general risk. And the judge just granted the motion (Doe v. Planned Parenthood of Illinois (N.D. Ill.))….

Friday, though, the judge reversed that decision:

This court's prior order allowing plaintiff initially to proceed under a pseudonym is vacated. Plaintiff's generalized statements of danger do not outweigh the normal rule that parties to federal cases must proceed under their names.

Here's part of Planned Parenthood's motion that led to the reversal:

While Plaintiff claims she fears "credible threats to [her] personal safety, including harassment, doxing, and physical harm," she does not identify any specific threat made to her or any former employee of PPIL. Instead, she cites general incidents where PPIL clinics were targeted. Moreover, Plaintiff does not allege in her Complaint or Motion to Proceed Under Pseudonym and for a Protective Order that PPIL harassed her or threatened her physical safety. Rather, Plaintiff's claims involve allegations of discrimination based on her race, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, and age as it relates to her compensation. Further, Plaintiff acknowledges that she does not reside in the community served by the former PPIL Englewood Clinic (or any community served by PPIL), so any perceived personal threat against Plaintiff's personal safety by individuals in the Englewood Community is certainly a stretch.

Furthermore, Plaintiff has not shown any exceptional circumstances that would justify allowing her to proceed anonymously in this Complaint. In rare circumstances, courts will allow parties to proceed anonymously "to protect the privacy of children, rape victims, and other particularly vulnerable parties." Plaintiff is not a child; she does not allege that she is a rape victim; and, she is not a vulnerable party. She likewise has not identified a real, specific threat of harm to her physical safety. If this Honorable Court allowed Plaintiff to proceed under a pseudonym in this case, then the Court would essentially be opening the floodgates by signaling that any former PPIL employee (or any employee who performed work for a "controversial" employer) could proceed anonymously in court when filing a Complaint involving allegations of employment discrimination related to compensation. This result would be absurd and counter to Rule 10(a) and the presumption of public court filings.

I think the reversal is correct; here's my thinking from the September post:

Public access to information about civil cases "serves to promote trustworthiness of the judicial process, to curb judicial abuses, and to provide the public with a more complete understanding of the judicial system, including a better perception of fairness." This access "protects the public's ability to oversee and monitor the workings of the Judicial Branch," and the Judiciary's "institutional integrity." "Any step that withdraws an element of the judicial process from public view makes the ensuing decision look more like a fiat and requires rigorous justification."

And this applies to the names of the parties as well. "[A]nonymous litigation" thus "runs contrary to the rights of the public to have open judicial proceedings and to know who is using court facilities and procedures funded by public taxes." "Identifying the parties to the proceeding is an important dimension of publicness. The people have a right to know who is using their courts."

Party names often offer the best clue for discovering further information about the case. Consider journalists who write about civil litigation. Without party names, they are limited to what they can glean from the filings and what the pseudonymous parties' lawyers are willing to reveal.

But armed with the names, they can investigate further. They can contact the parties' coworkers, business associates, or acquaintances. They can search court records in other cases to determine whether the fact pattern in this case had led to other litigation. They can more generally see what other cases have been filed by the plaintiff or against the defendant and see whether the parties have been found to be credible or not credible in the past. They can determine whether the parties might have ulterior motives for litigating.

Pseudonymity also tends to lead to additional restrictions on public access as a case unfolds. Because filed documents will often contain information that indirectly identify a pseudonymous party, courts may need to outright seal other case information or enjoin a party from publicly revealing the pseudonymous party's name (or other details of the lawsuit) in order to maintain effective pseudonymity.

And allowing pseudonymity in one case invites pseudonymization of all other cases that raise similar concerns, "open[ing] the door to parties proceeding pseudonymously in an incalculable number of lawsuits" of that kind. See, e.g., Doe v. Fedcap Rehab. Servs. (S.D.N.Y. 2018) ("At bottom, Plaintiff wants what most employment-discrimination plaintiffs would like: to sue their former employer without future employers knowing about it."). Courts have therefore treated litigating under a pseudonym as implicating the right of public access to judicial proceedings. And, because of this, all "circuit courts that have considered the matter have recognized a strong presumption against the use of pseudonyms in civil litigation."

Concrete evidence of specific threats to this particular person might suffice to justify a rare exception to this general rule. But it can't be enough that there's some evidence of past attacks against some Planned Parenthood ex-employees, Jews suing over anti-Semitism, police officers, employees of controversial political organizations, etc.

That post also quotes more from the plaintiff's argument for pseudonymity.

The post Judge Reverses Earlier Decision: Ex-Employee Can't Sue Planned Parenthood for Race Discrimination as a "Jane Doe" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: November 17, 1880

11/17/1880: The United States and China sign treaty that protects Chinese laborers residing in the United States. This treaty was implicated in Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886).

The post Today in Supreme Court History: November 17, 1880 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Open Thread

[What’s on your mind?]

The post Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

November 16, 2025

[Jonathan H. Adler] Is the Federal Prohibition on Felon Firearm Possession Constitutional?

[Judge Willett thinks that some federal statutes have been interpreted and applied in ways that conflict with the notion that the federal government only has limited and enumerated powers.]

Arnett Jackson Bonner has multiple felony convictions. This means he cannot possess a firearm. Under 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(1), convicted felons may not "possess in or affecting commerce, any firearm or ammunition; or to receive any firearm or ammunition which has been shipped or transported in interstate or foreign commerce." Because almost all firearms have been shipped or transported across state lines, this operates as a ban on firearm possession. Is this prohibition constitutional?

Current Supreme Court precedent provides that the federal government is one of limited and enumerated powers, and that the federal government's most expansive powers--to regulate commerce among the several states--is not a plenary power to regulate anything and everything, even when supplemented with the Necessary and Proper Clause. On this basis, in United States v. Lopez, the Court held that a prohibition on possessing guns in schools exceeded Congress' power to regulate commerce (even though the defendant in that case was facilitating a commercial transaction).

Statutes such as § 922(g)(1) seek to satisfy Lopez by including a jurisdictional element--in this case a requirement that the possession be "in or affecting commerce" or that the gun received crossed state lines--so as not to exceed the scope of the commerce power. But is it that easy? Jurisdictional elements written so broadly would seem to make a mockery of the idea that Congress' powers are limited and enumerated.

This is the view of at least two judges on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. In United States v. Bonner, Judge Willett wrote a separate concurring opinion (joined by Judge Duncan), suggesting a need to revisit the scope of jurisdictional elements such as those in § 922(g)(1), as well as to consider whether such broad prohibitions are consistent with the Second Amendment. (The opinion was just a concurrence because circuit precedent foreclosed Bonner's constitutional challenges to his conviction.)

The Commerce Clause portion of the concurrence reads:

"Every law enacted by Congress must be based on one or more of its powers enumerated in the Constitution." And although those powers "are sizable, . . . they are not unlimited." That means, among other things, Congress has no power to enact a comprehensive criminal code. As Chief Justice Marshall—no skeptic of national power—explained, "It is clear, that Congress cannot punish felonies generally." In short, not everything we may want to criminalize can be criminalized by the federal government. For example, "Congress has a right to punish murder in a fort, or other place within its exclusive jurisdiction," but it has "no general right to punish murder committed within any of the States."

As relevant here, § 922(g)(1) makes it "unlawful for any person . . . who has been convicted in any court of, a crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year . . . to . . . possess in or affecting commerce, any firearm or ammunition." On its face, the phrase "in or affecting commerce" might appear to require a genuine commercial nexus— placing § 922(g)(1) squarely within Congress's power "[t]o regulate Commerce . . . among the several States," or perhaps within its authority "[t]o make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution" that power. But in Scarborough v. United States, the Supreme Court interpreted § 922(g)(1)'s predecessor far more broadly, reading "in or affecting commerce" to demand no more than "the minimal nexus that the firearm have been, at some time, in interstate commerce." Applying that interpretation to § 922(g)(1), we have held that the Government need show only that a firearm was manufactured in one State and later discovered in another. The Supreme Court has gone further still, suggesting that a defendant need not even know the firearm ever crossed state lines.

So construed, it is difficult to see how § 922(g)(1) honors the principle of enumerated powers. In United States v. Lopez, the Supreme Court "identified three broad categories of activity that Congress may regulate under its commerce power." "First, Congress may regulate the use of the channels of interstate commerce. Second, Congress is empowered to regulate and protect the instrumentalities of interstate commerce, or persons or things in interstate commerce, even though the threat may come from intrastate activities. Finally, Congress' commerce authority includes the power to regulate those activities having a substantial relation to interstate commerce, i.e., those activities that substantially affect interstate commerce."

Mere possession of a firearm fits uneasily within any of these categories. The closest candidate might be "activities that substantially affect interstate commerce"—after all, some have argued that "widespread, firearm-related crime" has a substantial effect on the national economy. But whatever the effect of such "widespread" crime, the economic consequences of Bonner's individual act of possession is hardly "substantial." At best, § 922(g)(1) can meet the substantial-effects test only by aggregating the impact of all firearm possession by felons. Yet aggregation is ordinarily appropriate only when the underlying activity is economic—and firearm possession is not. As the Supreme Court explained in United States v. Morrison, "[t]he Constitution requires a distinction between what is truly national and what is truly local." And it is, indeed, "hard to imagine a more local crime than this."

While we have acknowledged the force of this objection, we have "regard[ed] Scarborough . . . as barring the way." But it was not Scarborough's holding that led us to that conclusion; as we have noted, "Scarborough addresses only questions of statutory construction, and does not expressly purport to resolve any constitutional issue." Instead, we have relied on what we took to be Scarborough's "implication of constitutionality." Yet a decision like Scarborough—in which the Commerce Clause "was not at issue, and was not so much as mentioned in the opinion"—is "scant authority" on the meaning of that Clause. In concluding otherwise, we have strayed from the Supreme Court's considered interpretations of the Commerce Clause in Lopez, Morrison, and NFIB v. Sebelius, and from its admonition that "[q]uestions which merely lurk in the record, neither brought to the attention of the court nor ruled upon, are not to be considered as having been so decided as to constitute precedents."

The pseudonymous Anti-Federalist Brutus objected to Congress's powers under the new Constitution, fearing that "implication" would "extend" them "to almost every thing." He also warned that the Judiciary would become an instrument for enlarging federal authority, predicting that we would "extend the limits of the general government gradually" through "a series of determinations," ultimately "facilitati[ng] the abolition of the state governments." Our reliance on Scarborough combines these fears: our decisions now expand federal power not by remote implication from the constitutional text, but by remote implication from our own precedents.

While Brutus's fears of the total abolition of the States may have been overstated, the steady expansion of federal power has nonetheless deprived the States of much of their freedom to pursue innovative, locally tailored solutions to vexing problems. Most debates over felon disarmament focus on the Second Amendment (which I address below). But there is also a serious question about whether some individuals who may constitutionally be disarmed should nevertheless have their rights restored. In the system the Framers designed, the States could—within constitutional bounds—serve "as laboratories for devising solutions" to that "difficult legal problem[]." By contrast, in the world § 922(g)(1) has created (and we have blessed), such experimentation is foreclosed by the long arm of the general government— much like the world Brutus feared.

* * *

As one of our colleagues has observed, "our circuit precedent dramatically expands the reach of the federal government under the Commerce Clause. No Supreme Court precedent requires it. And no proper reading of the Commerce Clause permits it."31 That alone is reason enough for the full court—or, if need be, the Supreme Court—to take up the question and reexamine our precedent.

If federal power to regulate commerce among the several states is limited--that is, if it is not a plenary power to reach any and all activity--§ 922(g)(1) cannot be read as broadly as current precedent suggests. To hold that Congress may regulate any activity that is conducted with any object that has crossed state lines or been bought or sold in interstate commerce is to obliterate the limits on federal power recognized in Lopez, Morrison, and NFIB. It is to treat commerce not as something to be regulated, but as a contagion that infects everything it touches, subjecting it to federal regulation and control.

Current law does not hold that once an individual has traveled or participated in interstate commerce, that person is eternally subject to federal regulation and control without regard for what activities they engage in (see, e.g., NFIB). There is no reason to treat objects differently. It is one thing to regulate articles in commerce as part of a regulatory scheme covering such commerce. It is quite another to say that such articles can always be regulated. Thus Alfonso Lopez could have been prosecuted for bringing a gun to school for the purposes of completing a gun sale, but it was impermissible to prosecute him merely for possessing a gun in a designated place (the school zone). The former could be understood as a regulation of commerce, the latter is not.

It seems to me that the analysis required by Lopez and its progeny should first identify the activity (or class of activities) subject to regulation, and then consider whether that class is economic in nature, or sufficiently related to economic activity that its regulation is a necessary part of a broader regulatory scheme. This approach would account for the Court's post-Lopez decisions (including the misstep in Gonzales v. Raich) while maintaining limits on federal power. It might, however, require reevaluating the constitutionality of statutory provisions like § 922(g)(1), or at least reconsidering the basis upon which such prohibitions could be considered constitutional.

And although it's beyond the scope of this post, Judge Willett's concerns about how to reconcile his circuit's precedent interpreting and applying § 922(g)(1) with Bruen are worth a read too.

The post Is the Federal Prohibition on Felon Firearm Possession Constitutional? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] To Join the Illuminati, Reply to Their Official Recruitment Email

Some spam I just received:

Greetings from the Illuminati World Elite Empire.

We extend this invitation to individuals who are ambitious, talented, and determined to rise above limitations. The Illuminati offers a gateway to fame, wealth, power, influence, and both spiritual and physical protection. Whether your goals lie in business, politics, the arts, or personal empowerment, becoming a member of the Illuminati will grant you access to life-changing opportunities. Upon initiation, you will receive countless benefits, including profound knowledge, influential global connections, and an immediate cash reward of $2.5 million USD to recognize your commitment to the Brotherhood.

Please note:

This message is part of our exclusive recruitment campaign, which concludes next month. This opportunity is extended only to serious and dedicated individuals. If you are not committed to joining the Illuminati Empire, we respectfully ask that you do not respond. Our organization values loyalty above all. Are you ready to embrace the path of power and enlightenment? If so, reply directly to our official recruitment email [e-mail address omitted -EV]

I feel so honored!

The post To Join the Illuminati, Reply to Their Official Recruitment Email appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] A Nice Little Rant on Oldies-not-Goodies from Georgia Supreme Court Justice Joseph Lumpkin (1853)

["[T]hat Court and that country is behind the age that stands still while all around is in motion."]

From Lowe v. Morris (Ga. 1853), which considers whether a writ of error issued by the Clerk of the Court should be dismissed on the grounds that it erroneously failed to include the seal of the Court. The rules of the court required clerks to include such a seal, but didn't prescribe the consequence if the rules weren't followed. The majority said that the writ remained valid:

The question is not, whether the parties to whom the writ of error was directed could be punished for not obeying it, because not in conformity with the rule; but the question is, whether the party applying for this writ of error, issued by the Clerk of this Court, shall be deprived of his constitutional right, merely because our own officer has omitted to put the seal of the Court to the writ, as directed by the rule? … The rule does not declare, that a writ of error issued in any other manner than that prescribed by the rule, shall be null and void ….

In my judgment, the rule is merely directory to the Clerk as to the manner in which writs of error issued by him shall be authenticated, and if he violates its provisions, it is an irregularity, which may subject him to personal peril and responsibility, but will not deprive the party of his constitutional right to be heard in this Court, as to the matters involved in the record which has been sent up here in obedience to our own mandate, attested by the official signature of our own officer, merely because he has failed to obey the direction of our rule of practice, in attaching the seal of the Court to the writ of error, which is in all other respects perfect.

Justice Joseph Lumpkin add a long, amusing, and somewhat rambling concurrence, including this passage; I quoted it on the blog back in 2008, but I just came across it again and thought I'd pass it along, in somewhat more detail:

For myself, I am free to confess, that I despise all forms having no sense or substance in them. And I can scarcely suppress a smile, I will not say "grimace irresistible," when I see so much importance attached to such trifles. I would cast away at once and forever, all law not founded in some reason—natural, moral, or political. I scorn to be a "cerf adscript" to things obsolete, or thoroughly deserving to be so. And for the "gladsome lights of jurisprudence" I would sooner far, go to the reports of Hartly, (Texas,) and of Pike and English, (Arkansas,) than cross an ocean, three thousand miles in width, and then travel up the stream of time for three or four centuries, to the ponderous tome of Sidenfin and Keble, Finch and Popham, to search for legal wisdom. The world is changed. Our own situation greatly changed. And that Court and that country is behind the age that stands still while all around is in motion.

I would as soon go back to the age of monkery—to the good old times when the sanguinary Mary lighted up the fires of Smithfield, to learn true religion; or to Henry VIII. the British Blue-Beard, or to his successors, Elizabeth, the two James's and two Charles's, the good old era of butchery and blood, whose emblems were the pillory, the gibbet and the axe, to study constitutional liberty, as to search the records of black-letter for rules to regulate the formularies to be observed by Courts at this day.

I admit that many old things may be good things—as old wine, old wives, ay, and an old world too. But the world is older, and consequently wiser now than it ever was before. Our English ancestors lived comparatively in the adolescence, if not the infancy of the world. It is true that Coke, and Hale, and Holt, caught a glimpse of the latter-day glory, but died without the sight. The best and wisest men of their generation were unable to rise above the ignorance and superstition which pressed like a night-mare upon the intellect of nations.

And yet we, who are "making lightning run messages, chemistry polish boots and steam deliver parcels and packages," are forever going back to the good old days of witchcraft and astrology, to discover precedents for regulating the proceedings of Courts, for upholding seals and all the tremendous doctrines consequent upon the distinction between sealed and unsealed papers, when seals de facto no longer exist! Let the judicial and legislative axe be laid to the root of the tree; cut it down; why cumbereth it, any longer, courts and contracts? …

And a bit more from Justice Lumpkin on why in particular he thought the seal was obsolete:

The truth is, that this whole subject like, many others, is founded on the usage of the times, and of the country.… The only reason ever urged at this day, why a seal should give greater evidence and dignity to writing is, that it evidences greater deliberation, and therefore should impart greater solemnity to instruments. Practically we know that the art of printing has done away with this argument. For not only are all official, and most individual deeds, with the seals appended, printed previously, and filled up at the time of their execution, but even merchants and business men are adopting the same practice, as it respects their notes.

Once the seal was every thing, and the signature was nothing. Now the very reverse is true: the signature is everything, and the seal nothing. Thanks to the advancing intelligence of the age! In the days of ignorance, to be able to read and write, would save a felon's neck. Many of the educated gentry now, who are too lazy to work, and prefer to live by their wits, are the fellows upon whom the penalties of the law are visited in their utmost severity.

So long as seals distinguished identity, there was propriety in preserving them. And as a striking illustration, see the signatures and seals to the death warrant of Charles the First, as late as January, 1648. They are 49 in number, and no two of them alike. But to recognize the waving, oval circumflex of a pen, with those mystic letters to the uninitiated, L. S. [locus sigilli, literally "place of the seal," used instead of a physical seal -EV] imprisoned in its serpentine folds, as equipotent with the coats of arms taken from the devices engraven on the shields of knights and noblemen; shades of Eustace, Roger de Beaumont, and Geoffry Gifford, what a desecration! The reason of the usage has ceased; let the custom be dispensed with altogether….

The post A Nice Little Rant on Oldies-not-Goodies from Georgia Supreme Court Justice Joseph Lumpkin (1853) appeared first on Reason.com.

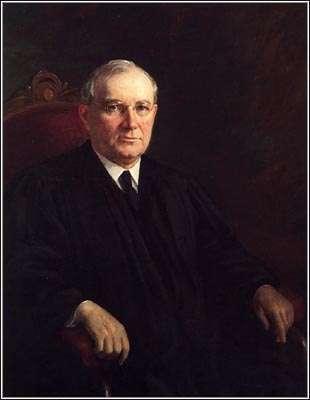

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: November 16, 1939

11/16/1939: Justice Pierce Butler dies.

Justice Pierce Butler

Justice Pierce ButlerThe post Today in Supreme Court History: November 16, 1939 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Open Thread

[What’s on your mind?]

The post Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

November 15, 2025

[Ilya Somin] Trump's Racially Discriminatory Refugee Policy

[There is no non-racist justification for prioritizing white Afrikaner South Africans while closing the door to virtually all other groups.]

NA

NA The Trump Administration recently announced a policy cutting US refugee admissions to a record-low of 7500 over the next year, while seeking to allocate those slots "primarily" be to Afrikaner South Africans and "other victims of illegal or unjust discrimination in their respective homelands." Given the administration's actions so far (admitting Afrikaners while seeking to bar virtually all other refugees), it is obvious few or no "other victims" are going to be admitted under the new policy. There is no remotely defensible justification for this policy, which is just a form of blatant racial and ethnic discrimination.

As explained in my previous post on this topic, I am not opposed to admitting Afrikaners, and there is even a plausible case they are legally eligible for refugee status, based on the South African government's discriminatory policies (which include various forms of affirmative action favoring Blacks as a way to compensate for the injustices of apartheid). But the idea that white South Africans have a stronger claim to refugee status than virtually every other group in the world is utterly absurd. Around the world, numerous racial, ethnic, and religious minorities, and victims of political persecution face vastly more severe discrimination and oppression.

There is no other good reason to privilege Afrikaners, either. In my earlier post, I criticized the idea that all or most white South Africans are inveterate racists, inimical to American liberal democratic values. That stereotype is simplistic and dated. But it's also wrong to make the opposite assumption, that they are somehow more attuned to those values than other would-immigrants and refugees. There is no basis for that assumption, either.

The same goes for claims that white South Africans can assimilate better based on language and culture. There are many potential English-speaking refugees who could do just as well, most obviously English-speaking Black Africans fleeing oppressive governments. And, as discussed in Chapter 6 of my book Free to Move: Foot Voting, Migration, and Political Freedom, social science evidence indicates that immigrants from non-English speaking countries generally learn the language quickly, and otherwise assimilate successfully. In sum, there is no reason to think that Afrikaners are a better fit for America than other refugees, unless being American is somehow synonymous with being white.

Conservatives who favor color-blindness in government policy in other situations (as I do) would do well to condemn Trump's policy here. Otherwise, it sure seems like their support for color-blindness is limited to situations where whites are the ones disadvantaged.

In almost any other area of government policy, blatant racial or ethnic discrimination like this would be struck down by the courts. Unfortunately, Supreme Court precedents like Trump v. Hawaii have created a double standard under which the government can get away with discriminatory policies in the immigration field, that would not be permitted elsewhere.

I have argued this double standard is indefensible, and the Supreme Court should reverse precedents suggesting otherwise. That may not happen anytime soon. But, even if this kind of racial discrimination in refugee policy is legal under current (badly misguided) precedent, that doesn't make it right.

Trump's extension of refugee status to Afrikaners might, I have suggested, set a precedent for expanding it to a wide range of other groups, one that can be effectively exploited by a future, more pro-immigrant, administration. Perhaps it might someday lead the federal government to rethink the current unduly narrow legal definition of "refugee," which excludes victims of many types of severe oppression. Trump and his minions surely don't intend any such effects. But unintended effects often occur with government policies.

Regardless, Trump's policy of favoring white South Africans while barring almost all other refugees, is utterly reprehensible. If you support color-blindness and abhor racial and ethnic discrimination in other contexts, you should condemn it here, too.

The post Trump's Racially Discriminatory Refugee Policy appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Journal of Free Speech Law: "The Fox Effect? Implications of Recruiting Corporate Law to Combat Misinformation," by Lili Levi

This new article is here. The Introduction:

In the wake of the mega-million-dollar settlement of U.S. Dominion's defamation action against Fox News over the network's broadcast of false election fraud claims after the 2020 U.S. presidential election, shareholder derivative actions were brought in Delaware against the parent company Fox Corporation's board of directors for breach of fiduciary oversight duties under state corporate law. The shareholder plaintiffs claimed that the Fox Corporation board breached its fiduciary duties by allowing Fox News knowingly to air false programming that put the company at risk of massive defamation liability. The Delaware Chancery Court denied Fox Corp.'s motion to dismiss the action for lack of standing, so the derivative action is currently pending.

But should corporate fiduciary duty law be interpreted to impose liability on the boards of companies that own news outlets for failing to control defamation and other speech tort risks associated with the editorial judgments made by their news subsidiaries? What makes the In re Fox Corporation Derivative Litigation (hereinafter "In re Fox") significant beyond its specific facts is that the plaintiffs' rationales seek to expand and supercharge the traditional oversight requirements of corporate law. If accepted, this turn to strengthening the disciplinary power of corporate governance in the news media context is likely to undermine press functions and the public interest in a free and independent press.

The expansive interpretations of corporate governance principles advanced in In re Fox could attract support on the basis that corporate oversight duties can serve to minimize misinformation in political discourse. Surveys reveal that many Americans see political misinformation as a social threat. If using corporate law to combat misinformation could lead to robust censorship effects on falsity, then many could consider this a significant public benefit. This could incentivize additional lawsuits against the press.

At the same time, such a development is likely to undermine press activity in ways harmful to public discourse. If these kinds of corporate governance claims are successful, they promise to generate a regulatory regime of editorial control by risk-averse corporate boards with much broader business interests than the protection of press freedom. The possibility of multi-million-dollar personal liability for parent company board members—or at least corporate insurers—is likely to generate excessive board-level micromanagement.

It is reasonable to expect that this would lead directly to journalistic self-censorship by news subsidiaries, deter journalism discouraged by a press-hostile government, and worsen journalistic timidity in covering the powerful and litigious. The self-regulatory compliance and oversight systems likely to be implemented in media companies as a response to heightened governance liability will inevitably extend to coverage of matters beyond clearly false information.

Enhanced board obligations may also lead to uneven effects. If the most likely plaintiffs in defamation actions continue to be the politically powerful, wealthy, or socially notable, parent company boards worried about follow-on oversight lawsuits might feel disproportionate pressure to reduce critical coverage of such elites. Society loses when the powerful are not held to account. Moreover, heightened compliance requirements could provide cover for targeted and politicized efforts by board members to influence the content of their news units. Such results would all be dangerous for the press function and, ironically, for the same public discourse that anti-misinformation initiatives seek to improve.

Proponents of expanded oversight doctrine may attempt to dispute these predictions of a chilling effect on journalism by noting that damages payouts in successful shareholder derivative actions go to the corporate treasury. So if a derivative action based on the company's prior payments to defamation plaintiffs is successful, the recovery may in fact offset the company's defamation payouts by recouping the money from the culpable directors themselves.

But such theoretically reallocated liability cannot in fact be expected to temper either the corporate costs of expanded oversight litigations or the expected chilling effect on news companies' journalist functions. If the Fox plaintiffs' arguments to change corporate oversight doctrine are successful, the true costs are likely to be extensive. When oversight compliance requirements are effectively dictated by corporate insurers with little or no commitment to journalism, intrusive oversight into and second-guessing of the editorial process is practically guaranteed. Even if this would lead to desirable results for the most extreme cases, the consequences of overzealous compliance are likely to be overbroad and troubling for the public interest.

The functions of an independent press are democratically necessary and already subject to excessive economic, social, and governmental pressure (including legally aggressive lawsuits against FCC-regulated broadcast outlets by a sitting President). Adding even more pressure is bad policy. In light of the sustained recent attacks on constitutional press protections in defamation cases, the limits to other newsgathering protections, and press-skeptical courts and juries, the press is already in a particularly vulnerable spot legally. Recent settlements of lawsuits against CBS and ABC brought by President Trump trigger suspicions that the executive branch is not only demanding but also obtaining exceptional capitulation from conglomerate-owned press entities.

The anti-misinformation frame implicit in In re Fox thus offers an opportunity to address key questions about what types of trade-offs we should accept between two of our foundational social commitments—to the democratic value of the independent press and the democratic value of truthful political discourse. Because the deterrent effects on misinformation of expanding corporate oversight duties to this context are unclear and the negative consequences for the press are predictable, the likely effects of expanding corporate fiduciary liability to parent corporations vis-à-vis the coverage decisions of their news media organizations should be resisted—even by those who deplore Fox News' 2020 election coverage. Ultimately, the Essay argues that courts should be reluctant to impose oversight liability in the news company context where executives or boards of directors did not actively direct clearly illegal conduct.

The Essay does not advance a doctrinal First Amendment argument. Nor does it request special and disproportionate exceptions or advantages for the press. It is, rather, a plea that before courts decide to advance anti-misinformation efforts by expanding ordinary corporate law principles to reach oversight of defamation risk in journalistic contexts, as proposed in In re Fox, they consider the potential impact of such an expansion on the ability of press organizations to perform their critical democratic functions.

To be sure, media owners are free to engage in intrusive oversight voluntarily. Nevertheless, the Essay argues that the effects of adopting a legal requirement are likely to lead to accelerated and industry-wide owner oversight over editorial decisions than is reported today. This poses a clear threat to journalistic independence. And since such intrusions are also unlikely to be open and transparent to those outside the organization in many instances, they could well obscure independent assessment of the degree of owner constraint on the outlet's reporting.

The Essay proceeds as follows: Part I.A describes In re Fox, the Delaware Chancery Court's denial of the defense's motion to dismiss the suit for demand futility, and subsequent developments. In so doing, it provides a "mini-overview" on shareholder derivative suits to set the context and clarify the procedural posture of the case for the unfamiliar. Part I.B examines the In re Fox litigation through an anti-misinformation lens. Part II.A sketches board oversight duties under current Delaware corporate law. Part II.B unpacks the expanded board monitoring duties sought by the plaintiffs in In re Fox. Part III explores our dual—and here conflicting—social commitments to press editorial freedom and truthful political dialogue. Part III.A takes the first step by showing how the plaintiffs' theories of liability in In re Fox do not justify expansion of current doctrine. Part III.B then addresses the dangers of expanded monitoring obligations to press functions—particularly since many news outlets are owned by other entities and since the current politico-legal environment amplifies the vulnerability of the press. Part III.C argues that the anti-misinformation benefits of the doctrinal expansion sought in In re Fox are at best uncertain and likely outweighed by the predictable chilling effects of expanded corporate law oversight duties on press functions. While recognizing the limits of its suggestions, Part III.D ends with some thoughts on other ways to promote press accountability.

The post Journal of Free Speech Law: "The Fox Effect? Implications of Recruiting Corporate Law to Combat Misinformation," by Lili Levi appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers