Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 2

November 28, 2025

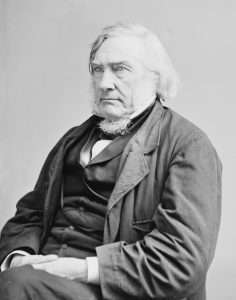

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: November 28, 1872

11/28/1872: Justice Samuel Nelson resigns.

Justice Samuel Nelson

Justice Samuel NelsonThe post Today in Supreme Court History: November 28, 1872 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Open Thread

[What’s on your mind?]

The post Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

November 27, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] Garry Kasparov, "What Thanksgiving Means to Me"

A nice piece, which I enjoyed and thought I'd pass along. As with all such things, it can't capture the whole picture, but it captures an important part of it, I think. You can see it on Persuasion, or (under a slightly different title) on Kasparov's Next Move; an excerpt:

Democracy, freedom—politics, too. These are not ends in and of themselves. They are a vehicle for delivering human happiness and flourishing. That goal is what we're fighting for.

The notion of a free society is abstract. Thanksgiving celebrates abundance, and abundance is tangible. You can taste it. Smell it. Hear it. The turkey and mashed potatoes on your plate, the chatter with loved ones, whom you're free to visit—these are the fruits of a free society….

Free societies deliver abundance.

These days, there is a lot of doom and gloom about the United States across the political spectrum. I am not talking about America's current democratic and institutional crisis, which is indeed deathly serious. I am referring to the short-sighted ideological decay that is increasingly popular with radicals of all stripes; on the right, the perception of America as sinful, deviant, and overly tolerant. On the left, it is the view that America is criminal, colonial, illegitimate….

Americans would do well to discard these self-destructive narratives. It may be hard to describe what lofty concepts like democracy and freedom really mean, but you can see the rewards of those concepts all around you if you're willing to open your eyes.

If Abraham Lincoln could find time for gratitude in the middle of a deadly Civil War, Americans today can too. If [Boris] Yeltsin [visiting the U.S. in 1989] could be so impressed by a grocery store many Americans might consider average, then you have something to be thankful for. I'll dispense with the caveat that America isn't perfect (what country is?). If you are thankful for something, then you have something you can fight for.

The post Garry Kasparov, "What Thanksgiving Means to Me" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] Trump's Unjust and Counterproductive Collective Punishment of Afghan Migrants

[Stopping all immigration processing for Afghan migrants is unjust and undermines rather than furthers the goal of combatting terrorism.]

Afghan evacuees arrive at Dulles International Airport in September 2021 (Rod Lamkey - CNP/Polaris/Newscom)

Afghan evacuees arrive at Dulles International Airport in September 2021 (Rod Lamkey - CNP/Polaris/Newscom)

Yesterday, Afghan migrant Rahmanullah Lakanwal shot and seriously wounded two National Guard members in Washington, DC. In response, the Trump Administration has "indefinitely" suspended processing of all immigration-related applications by Afghans, including those legally in the US already. The Trump Administration has already been trying to deport many recent Afghan migrants, and this attack may serve a convenient excuse for further actions along these lines.

Lakanwal's attack was a heinous crime, and he should be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law. But Trump's collective punishment of Afghan immigrants is both unjust and counterproductive. As a group, Afghan immigrants have a very low rate of terrorism. Moreover, many entered the United States precisely because they helped the US in the war against the Taliban and Al Qaeda. Barring or deporting such people will predictably undermine future efforts to combat terrorism.

My Cato Institute colleague Alex Nowrasteh, a leading expert on immigration and terrorism (author of the most comprehensive analysis of that subject), has a helpful post listing all Afghan migrants who committed or attempted to commit terrorist attacks in the US, from 1975 to 2024. There are a total of only six, none of whom caused any fatalities. If, as seems likely, Lakanwal's attack was motivated by terrorism, that would make seven. That's a very low rate (about one perpetrator every seven years) for an immigrant community that numbers some 200,000 people.

If Lakanwal's crime turns out to be a terrorist attack, it would be only the second attempted by one of the large number of Afghan migrants who entered since 2021, after the fall of Afghanistan to the Taliban (the earlier case was ). If, as the administration claims, the 2021 influx included large numbers of unvetted terrorists, we should be seeing a lot more incidents like these.

The overall rate of terrorism among Afghan migrants may well be lower than that among native-born Americans. Since 2020, domestic right-wing perpetrators of political violence (nearly all native-born whites) have killed 44 people, and likely committed many more non-fatal attacks, though the exact number is hard to pin down. Left-wing domestic terrorists accounted for another 18 deaths during the same period (they, too, probably committed many additional non-fatal attacks). That's likely a higher incidence of terrorism than Afghan migrants, even accounting for the latter's much smaller numbers. Exact comparisons are difficult because we don't have a comprehensive data base of non-fatal domestic terrorist incidents.

Conservatives rightly decry racial and ethnic discrimination by government in other contexts, for example when it comes to racial preferences in employment and education. These principles should apply to immigration, as well. There is no justification for collectively sanctioning all Afghan migrants for the aberrational acts of very small number of them. All the more so in a situation where deportation and exclusion would subject victims to the horrifically oppressive rule of the Taliban. That's far worse than, e.g., being unfairly denied admission to an elite college, and having to settle for a lower-ranking one.

In the case of the Afghans, deportation and exclusion may well actively undermine the struggle against terrorism, rather than further it. I explained why in an earlier post about Trump's efforts to deport Afghans who arrived since 2021:

The veterans' groups [opposing deportation of Afghans] are right. Afghans deported back to Afghanistan - especially those who worked with the US during the war - will indeed face harsh persecution by the Taliban. Deporting them would be profoundly unjust, and also a betrayal of wartime allies that will make it more difficult for the US to recruit local support in any future conflict. If we don't stand by our allies, why would anyone trust us?

I'm old enough to remember a time when Republicans saw themselves as fighters against radical Islamism. Now they seek to deport Afghan allies back to the tender mercies of the Taliban, under the ludicrous pretext that conditions in Afghanistan are improving under the Taliban's rule.

If we betray Afghans who helped us fight terrorism, based on indefensible ethnic prejudice, potential allies will be less likely to help us in future conflicts.

NOTE: To forestall misunderstandings, I will point out I am using the word "punishment" here in its colloquial sense, covering all retaliatory punitive actions, rather than in the technical legal sense, which only covers penal sanctions imposed after conviction for a crime. The administration's actions against Afghan migrants fit the former definition, even if not the latter.

The post Trump's Unjust and Counterproductive Collective Punishment of Afghan Migrants appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: November 27, 1964

11/27/1964: WGCB carried a 15-minute broadcast by the Reverend Billy James Hargis as part of the "Christian Crusade" series. This broadcast gave rise to Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. Federal Communications Commission (1969).

The Warren Court (1969)

The Warren Court (1969)The post Today in Supreme Court History: November 27, 1964 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Open Thread

[What’s on your mind?]

The post Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

November 26, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] Knife with 4½" Blade and Rounded Tip Wasn't "Weapon" Forbidden by Probation Condition, Oregon Court Holds

From yesterday's Oregon Supreme Court decision in State v. Cortes, written by Justice Bronson James:

Defendant, who is houseless, is on probation and subject to the general conditions of probation provided for by Oregon law. Those conditions include the requirement that a probationer shall "[n]ot possess weapons, firearms or dangerous animals." Defendant's probation officer issued a probation violation report alleging that defendant had violated the general weapons condition when he reported to the probation office with a knife in his backpack. At the probation violation hearing, defendant claimed that, although it was a knife, it was a steak knife, and it was therefore not a weapon but a tool, an essential eating implement that defendant carried in his backpack by necessity because, being houseless, he carried all his worldly possessions upon his person. {The knife was nine inches long, and the blade was four-and-a-half inches in length and had a rounded tip.}

The trial court rejected defendant's argument that the knife—even if it was a steak knife—was not a weapon for purposes of the probation statute. The Court of Appeals affirmed without opinion.

We allowed review to consider whether defendant violated the weapons condition in ORS 137.540(1)(j). The debate in this case might appear ontological in nature: What makes a weapon a weapon? What characteristics give an object weaponness?

But, we need not resolve those deeper philosophical questions. Our task is more grounded; we are only called upon to decide what the Oregon legislature intended to be considered a weapon for purposes of ORS 137.540. Here, based on the text, context, and legislative history of ORS 137.540(1)(j), and considering maxims of constitutional avoidance, we hold that the legislature intended for the term "weapons," as used in that statute, to apply to instruments designed primarily for offensive or defensive combat or instruments that would reasonably be recognized as having substantially the same character, and not to tools or objects designed primarily for utility, even when those tools can be used as weapons under some circumstances.

Based on that definition, we conclude that the trial court erred in concluding that defendant had violated the weapons condition without first engaging in a factual inquiry about the knife at issue and making a factual determination as to whether it was a knife that was designed primarily for offensive or defensive combat, or one that would reasonably be recognized as having substantially the same character, as opposed to a knife designed primarily for utility….

The development of the probation statutes since 1931 provides several important contextual clues for interpreting the weapons provision in ORS 137.540(1). First, the purpose of the probation system is to promote a probationer's freedom and need for rehabilitation so long as those interests are consistent with public safety. Second, it is Oregon's policy to ensure that the probation system operates in a swift, certain, and consistent manner. To achieve that policy, the legislature has developed a system of general and specific conditions of probation with the goal of limiting the discretion of probation officers to interpret judgments while, at the same time, providing probationers with clear notice of what conduct is prohibited and required while under supervision.

With that context in mind, it is unlikely that the legislature intended for "weapons" to mean literally anything capable of being used to inflict injury. Such a definition would capture a nearly endless number of objects and would give probation officers unreasonably broad authority to determine what objects constitute weapons. That result would deprive probationers of fair notice about what conduct would constitute a violation. Moreover, it would lead to arbitrary enforcement, with each probation officer determining individually whether a particular object is a weapon in a particular circumstance, as exemplified by the testimony of the probation officer in this case who, when asked to define a weapon, said it was "[a]nything that can cause me harm." …

[And i]f the term "weapons" is defined by situational use, then virtually anything in the home can be a weapon when used in a particular manner. Defining a weapon in terms of how an object is used works well when evaluating past behavior, such as criminal statutes that apply to actions already undertaken. But probation conditions exist to regulate future behavior. A situational "use" definition applied to constructive possession makes it nearly impossible for probationers to predict what future behavior would, or would not, be prohibited. Further, it invites arbitrary enforcement that would vary between probation officers. For these reasons, we reject the state's definition of "weapons," in favor of a definition of "weapons" tied to the features of an object's design….

The sole question in this case is the legislative intent in using the term "weapons" in the general conditions of probation. Nothing in our decision today forecloses an individual court from constructing a special condition of probation for knives or other forms of potentially dangerous tools—such as, for example, a special condition prohibiting actual possession of any type of knife, regardless of design, outside the home, unless possessed for work purposes—as long as the record supports that such a condition is "reasonably related to the crime of conviction or the needs of the probationer for the protection of the public or reformation of the probationer, or both." …

Justice Stephen Bushong, joined by Justice Christopher Garrett, dissented:

Under ORS 137.540(1)(j), a probationer shall not "possess weapons, firearms or dangerous animals." The statute does not define "weapons," and, as the majority opinion points out, a knife can be used as a tool—a utensil that is used to eat or cut food—and as a weapon. I would distinguish between the two, not by focusing on whether the implement was designed for combat or reasonably recognized as having the same character, as the majority opinion concludes, but by examining the circumstances surrounding a probationer's possession….

Defendant possessed the knife in his backpack, with the handle sticking out, making it readily accessible to him by reaching back—without removing his backpack—and grabbing it. That suggests that he possessed the knife to use it as a weapon. The handle of the knife was wrapped in tape, making it easier for defendant to grab it quickly and hold it tightly, in a threatening way, if he thought he needed a weapon. Defendant's manner of possessing the knife suggests that he possessed it as a weapon because he intended to use it, if necessary, as a weapon.

That also is how defendant's probation officer saw it. After seeing the knife handle sticking out of defendant's backpack, the probation officer thought that defendant was in possession of a "weapon" in violation of the general condition of probation in ORS 137.540(1)(j). Based on the probation officer's testimony, the trial court determined as a factual matter that defendant had possessed a weapon in violation of that general condition of probation. Because there are sufficient facts in the record to support that determination, I would affirm.

That does not mean that any possession of this knife would necessarily be a violation of the general condition of probation in ORS 137.540(1)(j). For example, if defendant had possessed this knife in the bottom of his backpack, wrapped in a napkin with a fork and spoon alongside a cup and a plate, I would conclude as a factual matter that he possessed it as an eating utensil, not as a weapon.

Similarly, a probationer who possessed a hammer in a toolbox alongside a wrench and a screwdriver on the way to his job at a construction site possessed the hammer as a tool, not as a weapon. A probationer who possessed a baseball bat in a duffel bag alongside a mitt, a baseball, cleats, and a baseball uniform on the way to a baseball field possessed the bat to play baseball, not to use it as a weapon. Under those circumstances, probation officers and courts should conclude that the probationer had not possessed a weapon in violation of the general condition of probation in ORS 137.540(1)(j).

But hammers and baseball bats, though not specifically designed for combat, can be used as weapons. The same is true of a knife that is not specifically designed for combat. The circumstances in which a probationer possessed such an implement can reveal that a probationer possessed it as a weapon. For example, a probationer holding a baseball bat or a hammer in his hand in a threatening manner as he walked towards a street brawl would be possessing the implement as a weapon. In my view, such a possession would violate the general condition of probation in ORS 137.540(1)(j), even if the probationer stopped short of using the implement to bludgeon someone….

Public defender Francis C. Gieringer represents Cortes.

The post Knife with 4½" Blade and Rounded Tip Wasn't "Weapon" Forbidden by Probation Condition, Oregon Court Holds appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] 2023 Criminal Trial Where Witnesses Wore Surgical Masks Violated Confrontation Clause

From last week's Texas Court of Criminal Appeals decision in Smith v. State, written by Judge Scott Walker; the Court of Criminal Appeals is Texas's highest court for criminal cases (the Texas Supreme Court handles civil cases):

Appellant's Confrontation Clause rights were violated by the trial court's mask mandate….

In Romero v. State (Tex. Crim. App. 2005), … one of the State's key witnesses refused to testify without wearing a "disguise" consisting of "dark sunglasses, a baseball cap pulled down over his forehead, and a long-sleeved jacket with its collar turned up and fastened so as to obscure [his] mouth, jaw, and the lower half of his nose." This Court noted that "the presence requirement is motivated by the idea that a witness cannot 'hide behind the shadow' but will be compelled to 'look [the defendant] in the eye' while giving accusatory testimony."

[The court in Romero also reasoned that, "Although the physical presence element might appear, on a superficial level, to have been satisfied by Vasquez's taking the witness stand, it is clear that Vasquez believed the disguise would confer a degree of anonymity that would insulate him from the defendant. The physical presence element entails an accountability of the witness to the defendant…. In the present case, accountability was compromised because the witness was permitted to hide behind his disguise." -EV]

Although in Maryland v. Craig (1990), the Supreme Court [rejected a Confrontation Clause because it] determined that the testimony of a child through a one-way closed-circuit monitor was reliable even though the physical presence element was lacking, the facts in Craig are not analogous to Romero. "[U]nlike Craig, [Romero] also involve[d] a failure to respect a second element of confrontation: observation of the witness's demeanor." When more than two elements of confrontation are being compromised, this Court determined that the Confrontation Clause requirements can only be circumvented if the public policy interest being served is "truly compelling." We did not find the witness's fears compelling, noting differences between adults' fears and children's fears and the fact that the defendant already knew the witness's name and address….

The Confrontation Clause requires case-specific evidence showing an encroachment of the defendant's right to confrontation was necessary to further a public-policy interest for the encroachment to be allowed under the United States Constitution. Because a surgical mask affects the physical-presence element of the Confrontation Clause and the jury's ability to assess demeanor, the trial court was required to make case-specific showings of fact that the mask mandate was necessary to further a public-policy interest….

[T]he use of surgical masks in the case at bar … is a significant impediment to viewing facial expressions due to the coverage of both the nose and mouth …. A reversal of the conviction is warranted because (1) the trial court did not show case-specific evidence that the masks were necessary, and (2) the mask mandate was applied regardless of individual necessity….

[Moreover], the trial took place in January of 2023, after face masks were no longer required by the Supreme Court of Texas and after the Governor had issued an executive order prohibiting mask requirements….

Presiding Judge David Schenck, joined by Judges Kevin Yeary and Jesse McClure, dissented:

This case poses the question of whether the trial court's policy requiring every person in the courtroom, including witnesses providing live testimony in the presence of jurors, to wear a mask violated Appellant's rights under the U.S. Constitution's Confrontation Clause. To be sure, the COVID-19 pandemic presented many courts with the same question concerning trials during the time in which state and national declarations of disaster were in effect; the answer to that question was uniform: masking requirements do not violate a defendant's confrontation rights. Now, this Court is presented with that question for a trial occurring post-pandemic. While the decision to require masks of all the trial's participants and observers was imprudent and (we are told) evidently political, I do not believe the interference with the juror's ability to observe witness demeanor somehow ripened into a Confrontation Clause violation….

The U.S Supreme Court has identified four elements that collectively ensure the right to confrontation: 1) physical presence; 2) oath; 3) cross-examination; and 4) observation of demeanor by the trier of fact. Craig. The "combined effect" of these distinct elements collectively "serve[ ] the purposes of the Confrontation Clause by ensuring that evidence admitted against an accused is reliable and subject to the rigorous adversarial testing that is the norm …." Being different, they are not necessarily equal.

It is physical presence of the witness, as opposed to any of the other elements alone or in combination, that anchors the Craig analysis and, in turn, any evaluation of a claim of deprivation. "[A] defendant's right to confront accusatory witnesses may be satisfied absent a physical, face-to-face confrontation at trial only where denial of such confrontation is necessary to further an important public policy and only where the reliability of the testimony is otherwise assured."

"Although demeanor evidence is … of … high significance, it is nevertheless well settled that it is not an essential ingredient of the confrontation privilege …." While the demeanor of a witness is also significant, infringements on that aspect of confrontation alone typically will not impede the core interest in forcing witness accountability for his or her testimony or amount to a categorical denial of the face-to-face encounter so critical to confrontation. To date, the U.S. Supreme Court has never held—or considered—whether disruption of the demeanor element would, on its own, constitute a violation of the confrontation right…. Accordingly, only the physical presence element triggers the Craig analysis…. Should the answer to the threshold issue of whether there is a denial of the face-to-face component of confrontation in the first place be no, the Craig analysis is simply not implicated….

[In this case], the witnesses were physically present in the courtroom during testimony, testified under oath, and were subject to cross-examination by counsel and observation by the jury throughout…. [T]he witnesses in this case were actually present in the courtroom before Appellant and within his scope of vision. Additionally, the jurors could assess witness credibility and demeanor by observing "body language" and "delivery." … "[T]he reliability of witness testimony" in this case "was otherwise assured; jurors were able to observe how witnesses moved, spoke, hesitated, and even cried," the witnesses were not disguised, their eyes were visible, and had no degree of anonymity due to the ability to remove the masks for identification.

Sophie Bossart represents Smith.

The post 2023 Criminal Trial Where Witnesses Wore Surgical Masks Violated Confrontation Clause appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Eleventh Circuit Upholds Dismissal of Trump v. Clinton and Affirms Sanctions Against Trump (Updated)

[A rare instance in which courts were willing to impose sanctions upon sanctionable conduct.]

Today the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit largely upheld the district court's dismissal of Donald Trump's lawsuit against Hillary Clinton and others and affirmed the district court's award of sanctions against Trump and Alina Habba. Chief Judge William Pryor wrote for the panel, joined by Judges Brasher and Kidd.

Judge Pryor's opinion in Trump v. Clinton begins:

These four consolidated appeals concern five separate orders. In 2022, between his terms of office, President Donald Trump filed a lawsuit against dozens of defendants, alleging several claims, including two under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act and three under Florida law. The district court dismissed the amended complaint with prejudice for failure to state a claim. On the defendants' motions, the district court also entered sanctions against Trump and his attorneys, under Rule 11 and under its inherent authority. While those orders were on appeal, Trump and his attorneys moved the district court to reconsider each order in the light of a report by Special Counsel John Durham. They also moved to disqualify the district judge. The district court denied both motions. Two defendants ask us to sanction Trump for bringing a frivolous appeal.

We affirm the orders with a caveat. Because the district court lacked jurisdiction over one defendant, it erred in dismissing the claims against that defendant with prejudice. So we vacate the dismissal of those claims and remand with instructions to dismiss them without prejudice. Because Trump's remaining claims are untimely and otherwise meritless, we affirm the dismissal of the amended complaint with prejudice for the other defendants. And because Trump and his attorneys committed sanctionable conduct and forfeited their procedural objections, we affirm both sanctions orders. The Durham Report does not change our conclusions, and the district court lacked jurisdiction to consider the disqualification motion. Yet, because the appeal of the dismissal order is not frivolous, we deny both motions for appellate sanctions.

Update: Here are some portions of the opinion discussing the sanctions:

Federal courts have the inherent authority to "fashion an appropriate sanction for conduct which abuses the judicial process." Chambers v. NASCO, Inc., 501 U.S. 32, 44–45 (1991). This authority arises from the "control necessarily vested in courts to manage their own affairs so as to achieve the orderly and expeditious disposition of cases." Link v. Wabash R.R. Co., 370 U.S. 626, 630–31 (1962). To "unlock[] that inherent power," a court must find that a party or his attorney acted in "bad faith." Sciaretta v. Lincoln Nat'l Life Ins. Co., 778 F.3d 1205, 1212 (11th Cir. 2015). On a finding of bad faith, the district court may "assess attorney's fees." Id.

The district court ordered Trump and Habba (along with her law firm) to pay nearly $1 million in attorney's fees under its inherent authority. On appeal, Trump and Habba present several arguments against the sanctions. We discuss and reject each in turn. . . .

After noting that Trump and Habba abandoned some of their arguments against the sanctions (because Trump only ever hires the best lawyers), the opinion addresses some of the arguments on the merits.

We review a finding of bad faith for clear error. Bagelheads, 75 F.4th at 1311. Clear error review requires "that a finding that is plausible in light of the full record—even if another is equally or more so—must govern." Grayson v. Comm'r, Ala. Dep't of Corr., 121 F.4th 894, 896 (11th Cir. 2024) (citation and internal quotation marks omitted). To establish bad faith under the inherent authority standard, a court must find "subjective bad faith." Purchasing Power, 851 F.3d at 1224. "A finding of bad faith is warranted where an attorney knowingly or recklessly raises a frivolous argument, or argues a meritorious claim for the purpose of harassing an opponent." Thomas v. Tenneco Packaging Co., 293 F.3d 1306, 1320 (11th Cir. 2002) (citation and internal quotation marks omitted). An egregious failure to pursue "reasonable inquiry into the underlying facts" of a claim can also support a finding of bad faith. In re Evergreen Sec., Ltd., 570 F.3d 1257, 1274 (11th Cir. 2009) (citation and internal quotation marks omitted).

The district court rested its bad faith finding on three features of the amended complaint. First, it found that the amended complaint was a shotgun pleading filed for a political purpose. Second, it found that the amended complaint contained factual allegations that were "knowingly false or made with reckless disregard for the truth." Finally, it ruled that the amended complaint was based on patently frivolous legal theories. Trump challenges all three grounds. We affirm on the first and third. . . .

The district court bolstered its finding of bad faith by pointing to Trump's litigation conduct in other cases. It found that Trump's activity showed a "pattern of misusing the courts." Trump and Habba argue the district court was wrong to consider Trump's other litigation conduct.

The district court did not clearly err. We have affirmed a sanctions award based on a review of "similar cases" brought by a plaintiff and his attorney. Johnson v. 27th Ave. Caraf, Inc., 9 F.4th 1300, 1313–14 (11th Cir. 2021). Trump and Habba cite no contrary authority. Although they tell us that the district court misread Johnson and other cases, they never explain why the principle it drew from those cases is wrong. Nor do they explain how the district court clearly erred in concluding that Trump's litigation conduct in other cases was "similar" to the conduct here. All they offer is the cursory statement that the other cases were "brought for different, good faith reasons." We have no basis for vacatur.

I challenge anyone to read this opinion and conclude that Alina Habba has any business working in a U.S. Attorney's office, let alone being an actual U.S. Attorney, acting or otherwise.

The post Eleventh Circuit Upholds Dismissal of Trump v. Clinton and Affirms Sanctions Against Trump (Updated) appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] D.C. Circuit Upholds Energy Department Ban on Non-Condensing Furnaces and Water Heaters

[After this decision, rescinding this Biden Administration rule may be more difficult.]

In American Gas Association v. U.S. Department of Energy, a divided panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit rejected a legal challenge to a regulation adopting energy efficiency standards for natural gas-powered consumer furnaces and commercial water heaters that effectively bans non-condensing units from the market. This regulation had been adopted in 2023, and the court heard oral argument in November 2024, but only released its opinion in November of this year.

According to the panel opinion, written by Judge Wilkins and joined by Judge Pillard, the regulation did not exceed DOE's authority under the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA) and was not arbitrary and capricious. Judge Rao dissented (and, in my view, had the better of the argument).

Here is how Judge Rao describes the issues and why the DOE rule should have been held unlawful.

This case concerns Department of Energy regulations that effectively ban a class of common and affordable gas-powered appliances. Millions of homes and commercial buildings are equipped with traditional, "non-condensing" gas furnaces and water heaters. These reliable appliances vent their exhaust up a standard chimney. A more efficient "condensing" technology exists, but it is incompatible with traditional chimneys. Instead, it requires a different venting mechanism. In its quest for greater efficiency, the Department has issued new efficiency standards that effectively ban the sale of non-condensing appliances. As a result, any consumer seeking to replace a traditional gas furnace or commercial water heater will be forced to install a condensing model, a switch that often requires disruptive and expensive renovations to a building's venting and plumbing systems.

These standards run afoul of the careful balance Congress struck in the Energy Policy and Conservation Act ("EPCA") between improving energy efficiency and preserving consumer choice. While EPCA empowers the Department to set efficiency standards, the statute also imposes a critical limit on that authority. The agency is prohibited from imposing an efficiency standard that will result in the "unavailability" of a product with a "performance characteristic" that consumers value.

No one doubts that the challenged regulations make non-condensing appliances unavailable. The central question in this case is whether a non-condensing appliance's venting mechanism is a protected "performance characteristic." Because these appliances utilize a chimney common to many older homes and buildings, installing a condensing appliance will often require complex and costly renovations that may reduce a building's useable space. The ability to vent through a traditional chimney is exactly the kind of real-world feature Congress protected from elimination in the marketplace. The Department's efficiency standards, which make non-condensing appliances unavailable, are therefore contrary to law.

Independent of this legal error, the Department failed to demonstrate that the regulations are "economically justified," as mandated by EPCA, by showing their "benefits … exceed [their] burdens." 42 U.S.C. § 6295(o)(2)(B)(i); see also id. § 6313(a)(6)(B)(ii). The Department utilized an economic model that we have previously held to be irrational and inconsistent with EPCA's requirements. The flawed model fares no better here. Because the regulations are contrary to law and predicated on an arbitrary economic analysis, I respectfully dissent.

As Judge Rao's opinion indicates, it is difficult to square the majority's approach to the statute with Loper Bright. The statutory question in the case is what counts as a "performance characteristic." The majority thinks the statute is ambiguous on this point, and thus turns to legislative history and suggests the challengers face an evidentiary burden to prove that non-condensing appliances have such characteristics. Yet as Judge Rao notes, any such evidentiary burden "applies only to the factual question of whetehr a standard will cause a protected product to become available, not to the legal question of what qualifies as a 'performance characteristic.'" As she explains:

The central disagreement turns on the legal question of what counts as a "performance characteristic" under EPCA. The majority largely ducks this question by declaring that EPCA is ambiguous as to the meaning of "performance characteristic" and "utility." Majority Op. 16–18. The majority takes this ambiguity as a license to defer to the Department. But this Loper Bright avoidance is inconsistent with the Supreme Court's directive that a court must "use every tool at [its] disposal to determine the best reading of the statute and resolve the ambiguity." 144 S. Ct. at 2266.

Judge Rao further explains why the Department failed to provide an adequate justification for the rule, but this is a lesser concern that the question of statutory authority.

This rule would seem to have been a good candidate for quick rescission under the Trump Administration's directive that agencies identify and rescind regulations that lack adequate statutory warrant under the best interpretation of the applicable statute. Judge Rao's statutory arguments are more persuasive than those offered by the majority, particularly in a post-Chevron world in which the agency does not receive deference and the best reading of a given statute is supposed to govern. The problem now, however, is that the D.C. Circuit has upheld the regulation as consistent with the the statute.

Given this ruling, were the Department to rescind the rule on these grounds it would face a likely reversal (unless it were able to get further review in the Supreme Court). This means that we may be stuck with this rule. Failing to rescind the rule earlier, or even to ask the D.C. Circuit to delay issuing an opinion so the Administration could review the rule, seems to have been an oversight, and a costly one at that.

The post D.C. Circuit Upholds Energy Department Ban on Non-Condensing Furnaces and Water Heaters appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers