Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 8

November 18, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] Eleventh Circuit Rejects Trump's Defamation Lawsuit Over CNN 2022 "Big Lie" Statement

[President Trump "complained that, by using the phrase 'Big Lie' to describe his claims about the 2020 presidential election, CNN defamed him."]

From Trump v. CNN, Inc., decided today (correctly, I think) by Judges Adalberto Jordan, Kevin Newsom, and Elizabeth Branch:

In 2022, Plaintiff-Appellant Donald J. Trump filed a defamation suit against Cable News Network, Inc. (CNN). He complained that, by using the phrase "Big Lie" to describe his claims about the 2020 presidential election, CNN defamed him….

To be clear, CNN has never explicitly claimed that Trump's "actions and statements were designed to be, and actually were, variations of those [that] Hitler used to suppress and destroy populations." But, according to Trump, this assertion is implied in CNN's use of the phrase "Big Lie." Further, he argues, the phrase "could reasonably be interpreted … by facets of the CNN audience as accusations that [Trump] is doing exactly what the historical record shows [that] Hitler did in his monstrous, genocidal crimes against humanity." And, the argument goes, these accusations are false statements of fact because Trump did not do exactly what Hitler did. Hitler engaged in a monstrous genocide; Trump "exercis[ed] a constitutional right to point out concerns with the integrity of elections."

Trump's argument is unpersuasive. First, although he concedes that CNN's use of the term "Big Lie" is, to some extent, ambiguous, he assumes that it is unambiguous enough to constitute a statement of fact. This assumption is untenable. Although we haven't squarely addressed the point, case law from other circuits is persuasive. In Buckley v. Littell (2d Cir. 1976), the Second Circuit held that, by using the terms "fascist," "fellow traveler," and "radical right" to describe William F. Buckley, Jr., the defendant was not publishing "statements of fact." Buckley, 539 F.2d at 893. Rather, the court ruled, the terms were "so debatable, loose and varying[ ] that they [we]re insusceptible to proof of truth or falsity." Similarly, in Ollman v. Evans (D.C. Cir. 1984), the D.C. Circuit held that when the defendant called the plaintiff "an outspoken proponent of political Marxism," his statement was "obviously unverifiable."

Trump argues that the term "Big Lie" is less ambiguous than the terms "fascist," "fellow traveler," "radical right," and "outspoken proponent of political Marxism." But he does not explain this assertion. If "fascist"—a term that is, by definition, political—is ambiguous, then it follows that "Big Lie"—a term that is facially apolitical—is at least as ambiguous.

Second, Trump's argument hinges on the fact that his own interpretation of his conduct—i.e., that he was exercising a constitutional right to identify his concerns with the integrity of elections—is true and that CNN's interpretation—i.e., that Trump was peddling his "Big Lie"—is false. However, his conduct is susceptible to multiple subjective interpretations, including CNN's. As we held in Turner, one person's "subjective assessment" is not rendered false by another person's "different conclusion." In Turner, the defendants stated that, on at least one occasion, the plaintiff, James Turner, offensive line coach of the Miami Dolphins, participated in the "homophobic taunting" of one of his players. Turner argued that this statement was false because his conduct was a "harmless 'joke,' as opposed to homophobic taunting." We rejected his argument, concluding that the statement "[wa]s the [d]efendants' subjective assessment of Turner's conduct and [wa]s not readily capable of being proven true or false."

Just as the Turner defendants described Turner's conduct as "homophobic taunting," CNN described Trump's conduct as his "Big Lie." Just as Turner viewed his own conduct as a "harmless 'joke,'" Trump viewed his own conduct as the exercise of a constitutional right. As in Turner, so too here. CNN's subjective assessment of Trump's conduct is not readily capable of being proven true or false.

Trump has not adequately alleged the falsity of CNN's statements. Therefore, he has failed to state a defamation claim….

Eric P. Schroeder and Brian M. Underwood, Jr. (Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner LLP) and George S. LeMieux and Eric C. Edison (Gunster, Yoakley & Stewart, P.A.) represent CNN.

The post Eleventh Circuit Rejects Trump's Defamation Lawsuit Over CNN 2022 "Big Lie" Statement appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] COVID Closure of Private Beach Access Constitutes a Taking

[The Eleventh Circuit concludes "there is no COVID exception to the Takings Clause."]

In April 2020, as the COVID outbreak was unfolding, Walton County, Florida, closed all beaches--public and private. Did this ordinance, as applied to private beaches, constitute a taking of private property under the Fifth Amendment? Yes it did, according to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit in an opinion released yesterday.

Judge Lagoa wrote for the panel in Alford v. Walton County, joined by Judges Brasher and Carnes. Her opinion begins:

The Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment provides that "private property" shall not "be taken for public use, without just compensation." U.S. Const. amend. V. Here, we consider whether a Walton County ordinance that proscribed all access to privately-owned beaches constitutes a "taking" under the Fifth Amendment. We hold that it does.

Despite the County's significant infringement on property rights, the district court granted summary judgment in favor of Walton County, noting that the ordinance was enacted during the COVID-19 pandemic. But there is no COVID exception to the Takings Clause. Instead, the government must respect constitutional rights during public emergencies, lest the tools of our security become the means of our undoing. "The Founders recognized that the protection of private property is indispensable to the promotion of individual freedom. As John Adams tersely put it, '[p]roperty must be secured, or liberty cannot exist.'" Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid, 594 U.S. 139, 147 (2021) (quoting Discourses on Davila, in 6 Works of John Adams 280 (C. Adams ed. 1851)).

Accordingly, after careful review, and with the benefit of oral argument, we affirm the district court's dismissal of the Landowners' prospective claims, but we reverse the district court's judgment on the Landowners' Takings Clause claim. Because we hold that the County effectuated a "taking" of the Landowners' property, we need not address the Landowners' claims under the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments. On remand, the district court shall consider the amount of "just compensation" that the Landowners are entitled to. U.S. Const. amend. V.

Here is how Judge Lagoa summarizes the conclusion that taking occurred:

the district court held that Ordinance 2020-09 was neither a physical taking nor a regulatory taking. We disagree. This case involves a textbook physical taking: Walton County enacted an ordinance barring the Landowners from entering and remaining on their private property; Walton County's officers physically occupied the Landowners' property; and Walton County's officers excluded the Landowners from their own property under threat of arrest and criminal prosecution. In other words, Walton County wrested the rights to possess, use, and exclude from the Landowners, and it took those rights for itself. That triggers the Landowner's right to just compensation.

The analysis that follows digs in to how the Supreme Court's decision in Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid from 2021 informs the analysis of government restrictions on land-use that so pervasively infringe upon a landowner's right to occupy their own land and exclude others.

Although this case involves a county ordinance, the Ordinance at issue effectuated a "physical appropriation" of the Landowner's property. Id. Thus, "a per se taking has occurred, and Penn Central has no place." Id. Ordinance 2020-09 physically appropriated the Landowners' property because it barred their physical access to the land. And to enforce the Ordinance, the County entered the Landowners' property at will for the specific purpose of excluding the Landowners. The County's officers parked their vehicles on private property to deter entry, used private property as their own highway, and forced Landowners to vacate their property under threat of arrest. Put simply, the County "entered upon the surface of the land and t[ook] exclusive possession of it," thereby triggering the right to just compensation. Causby, 328 U.S. at 261.

Notwithstanding these infringements on the right to possess and the right to exclude, the district court found that Ordinance 2020-09 was a simple "use" restriction. In so ruling, the district court emphasized that the Landowners retained the ability to sell their property, that the Ordinance was temporary, that the Landowners could still use part of their property, and that the Landowners could still exclude other citizens from their private property. None of these points makes a difference. At bottom, Ordinance 2020-09 prohibited the Landowners from physically accessing their beachfront property under any circumstances. That is different from a restriction on how the Landowners could use property they otherwise physically possessed.

Cedar Point is a useful comparison. Recognizing the distinction between physical appropriations and use restrictions, the Cedar Point Court rejected an argument advanced by California that the regulation permitting union organizers to enter private property was a mere use restriction. 594 U.S. at 154. There, a California regulation granted union organizers a right to access private farmland "for the purpose of meeting and talking with [agricultural] employees and soliciting their support." Id. at 144 (quoting Cal. Code Regs., tit. 8, § 20900(e)). Under the regulation, the union organizers had a right to access the private farmland for up to three hours per day and 120 days per year. Id. Importantly, the regulation in Cedar Point did not infringe on the rights of the farm owners to possess, to use, or to dispose of their property. See id. Regardless, the Court held that the regulation effectuated a physical taking because it infringed on the owners' right to exclude the union organizers. Id. at 149–54. In the Court's words, "[s]aying that appropriation of a three hour per day, 120 day per year right to invade the growers' premises 'does not constitute a taking of a property interest but rather . . . a mere restriction on its use, is to use words in a manner that deprives them of all their ordinary meaning.'" Id. at 154 (quoting Nollan v. California Coastal Comm'n, 483 U.S. 825, 831 (1987)).

In other words, the mere fact that the Cedar Point landowners retained the rights to possess, to use, and to sell their property did not undermine the fact that a physical taking occurred. Id. California still "physically appropriated" the landowners' property by granting the union organizers a right of entry. Id. Here, the physical taking at issue is even more severe than the one in Cedar Point. Unlike the regulation at issue in Cedar Point, Ordinance 2020-09 infringes on the right to exclude and the rights to possess and use. The Ordinance prohibited the Landowners from entering and remaining on their own property, while County officers entered and remained at will. The mere fact that the Landowners could—according to the district court—still "exclude the public" from their property is immaterial. In Cedar Point, it made no difference that the property owners retained the right to exclude everyone but the "union organizers." See 594 U.S. at 144. Likewise, it makes no difference here that the Landowners retained the authority to exclude everyone other than County officials tasked with enforcing the Ordinance.

As this opinion indicates, Cedar Point may turn out to have been something of a turning point in the law of regulatory takings.

[Note: I edited the title of the post to omit the word "regulatory," as the Eleventh Circuit's analysis characterizes the government regulation here as a per se physical taking. In my view, this should be understood as a type of regulatory taking, and that not all regulatory takings should be subject to the Penn Central balancing test, but that is not the way that the Court's analysis proceeded, and is arguably not the best way to understand current doctrine. Cleaning up these categories, and perhaps interring Penn Central in the process, is something I hope the Court will do.]

The post COVID Closure of Private Beach Access Constitutes a Taking appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] W. Va. High Court on Placing Children with Amish Foster Families

From Thursday's decision in In re M.B. (written by Chief Justice William Wooton):

The petitioner ("the petitioner") is the guardian ad litem of M.B., a two-year-old child who has been in the continuous care of the … foster parents … since shortly after his birth. The petitioner appeals from the February 29, 2024, order entered by the Circuit Court of Kanawha County, West Virginia, denying her motion to remove M.B. from the foster parents' home, arguing that because his placement in the home cannot lead to permanency, i.e., adoption, it would be in his best interest to be placed with another family that can offer him permanency.

The petitioner offers several bases for her contention that the foster placement here cannot lead to permanent placement. First, the petitioner contends that the foster parents, being members of an Old Order Amish community, would restrict M.B.'s formal education to grades one through eight and thus deprive him of his constitutional right to a thorough and efficient education. The petitioner also argues that remaining with Amish foster parents would not be in M.B.'s best interests because he would not have regular pediatric checkups, would not be vaccinated, would not be exposed to technology, and would not learn to drive. Finally, the petitioner suggests that M.B.'s adoption into the Amish community is problematic, at best, in that the community might not welcome a biracial child.

The respondent, the West Virginia Department of Human Services, and the foster parents, argue that to the contrary, it is in M.B.'s best interests to remain in what all parties acknowledge to be a loving home with the foster parents and his three siblings, who are part of the family unit…. [W]e affirm the circuit court's denial of the petitioner's motion to remove M.B. from the foster parents' home….

[A.] M.B.'s Right to Formal Education Past the Eighth Grade

We begin by recognizing that this issue is unique: whereas the relevant precedents guiding our consideration all involve the right of parents to the free exercise of their religion versus the interest of a state in establishing and enforcing educational standards, this case involves the right of a child to receive an education that meets this State's educational standards. In this regard, the United States Supreme Court acknowledged this distinction in Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972), noting that

[t]he dissent argues that a child who expresses a desire to attend public high school in conflict with the wishes of his parents should not be prevented from doing so. There is no reason for the Court to consider that point since it is not an issue in the case. The children are not parties to this litigation. The State has at no point tried this case on the theory that respondents were preventing their children from attending school against their expressed desires[.]

In contrast, here the petitioner, M.B.'s guardian ad litem, acting on his behalf, is a party to this appeal and advocates for what she claims to be his … statutory right to a high school education….

Thus, we turn to the petitioner's statutory claims, which first requires us to examine the FCBR [Foster Child Bill of Rights] …:

(a) Foster children and children in a kinship placement are active and participating members of the child welfare system and have the following rights:

(1) The right to live in a safe and healthy environment, and the least restrictive environment possible;

(2) The right to be free from physical, sexual, or psychological abuse or exploitation including being free from unwarranted physical restraint and isolation.

(3) The right to receive adequate and healthy food, appropriate and seasonally necessary clothing, and an appropriate travel bag;

(4) The right to receive medical, dental, and vision care, mental health services, and substance use treatment services, as needed;

(5) The right to be placed in a kinship placement, when such placement meets the objectives set forth in this article;

(6) The right, when placed with a foster of kinship family, to be matched as closely as possible with a family meeting the child's needs, including, when possible, the ability to remain with siblings;

(7) The right, as appropriate to the child's age and development, to be informed on any medication or chemical substance to be administered to the child;

(8) The right to communicate privately, with caseworkers, guardians ad litem, attorneys, Court Appointed Special Advocates (CASA), the prosecuting attorney, and probation officers;

(9) The right to have and maintain contact with siblings as may be reasonably accommodated, unless prohibited by court order, the case plan, or other extenuating circumstances;

(10) The right to contact the department or the foster care ombudsman, regarding violations of rights, to speak to representatives of these offices confidentially, and to be free from threats, retaliation, or punishment for making complaints;

(11) The right to maintain contact with all previous caregivers and other important adults in his or her life, if desired, unless prohibited by court order or determined by the parent, according to the reasonable and prudent parent standard, not to be in the best interests of the child;

(12) The right to participate in religious services and religious activities of his or her choice to the extent possible;

(13) The right to attend school, and, consistent with the finances and schedule of the foster or kinship family, to participate in extracurricular, cultural, and personal enrichment activities, as appropriate to the child's age and developmental level;

(14) The right to work and develop job skills in a way that is consistent with the child's age and developmental level;

(15) The right to attend Independent Living Program classes and activities if the child meets the age requirements;

(16) The right to attend court hearings and speak directly to the judge, in the court's discretion;

(17) The right not to be subjected to discrimination or harassment;

(18) The right to have access to information regarding available educational options;

(19) The right to receive a copy of, and receive an explanation of, the rights set forth in this section from the child's guardian ad litem, caseworker, and attorney;

(20) The right to receive care consistent with the reasonable and prudent foster parent standard; and

(21) The right to meet with the child's department case worker no less frequently than every 30 days.

Focusing on subsections (a)(13) and (18) of the FCBR, the petitioner argues that M.B.'s continued placement with Amish foster parents will deprive him of his statutory right to attend school—specifically, high school—and his right of access to information about available educational options, thus mandating his removal from the foster parents' home. We disagree. The petitioner appears to view each and every provision of the FCBR as mandatory, i.e., one strike and you're out. However, our precedents make clear that with the exception of subsections (a)(1), (2), and (3), the provisions of the FCBR constitute an interwoven set of factors to be considered and weighed in making a determination of whether a foster child's placement is in his or her best interests….

[B.] M.B.'s Right to Medical Care and Vaccinations

The petitioner next alleges that pursuant to the FCBR, M.B. has a right to medical care—care that he will not receive because the foster father testified that the Amish community does not have a doctor, that children are taken to the doctor only in situations where home health remedies are clearly inadequate, and that community members do not routinely vaccinate their children. We reject this claim both on legal and factual grounds.

First, as discussed supra …, an allegation that the placement of a child will result in a deprivation of a right enumerated in subsections (a)(4) through (21) of the FCBR does not, in and of itself, mandate removal from the placement; rather, the facts and circumstances are to be considered and weighed by the circuit court together with all other facts and circumstances supporting, or not supporting, the placement.

Second, the facts of this case simply do not support the petitioner's allegations that M.B. has been or will be denied medical care. The evidence of record shows that the foster parents have scrupulously abided by all of the DHS's requirements, taking M.B. for regular medical checkups, having him vaccinated, taking him to a specialist for treatment and a surgical procedure to correct bilateral hydronephrosis, and giving him all prescribed medications therefor. Further, the undisputed testimony of the foster father was that he and the foster mother would continue to seek medical care for the child when necessary and would consider additional vaccinations if they had reason to believe that those vaccinations would be efficacious.

Third, the petitioner points to no statutes or case law supporting her claim that "medical care," as the term is used in West Virginia Code section 49-2-126(a)(4), mandates regularly scheduled preventative medical checkups for children and/or vaccinations for children who will not be attending public school….

[T]he circuit court considered and weighed all of the evidence presented and concluded that placement with the foster parents would not result in the denial of M.B.'s right to medical care. Again, the court's findings of fact and conclusions of law are amply supported by the evidence of record, and we therefore will not disturb the court's ruling.

[C.] M.B.'s Placement With a White Family …

In his testimony, the foster father acknowledged that the foster parents had expressed a preference for White children but explained that they did so out of a concern that the Amish community might not accept children of another race, a concern which proved to be wholly unfounded. {The foster father testified that the community had been completely accepting of, and welcoming to, all four of the children.} The foster father further testified that if this ever changed, i.e., if the community became less accepting or welcoming as time went on, the family would move to another community. Finally, notwithstanding any initial hesitation they may have had, the fact is that the foster parents went ahead and welcomed four mixed-race children into their home, have adopted three of them, and hope to adopt M.B. as well.

We reject any suggestion by the petitioner that the foster parents' initial stated preference for a White child should somehow disqualify them from providing a home for children of other races or ethnicities, or that they in any way have denied M.B. a safe and healthy environment. The evidence in this case is undisputed that the foster parents have provided M.B. and his sisters with what the special commissioner characterized as a "loving and spiritual" home….

Each of the other four Justices on the five-Justice court wrote separate concurrences. Justice Thomas Ewing's and Justice Haley Bunn's concurrences stressed the importance of keeping the child with (to quote Justice Bunn) "the only family he has ever known." Senior Justice John Hutchison's concurrence likewise took a similar approach: "There was no showing by anyone establishing that it was in M.B.'s best interest to remove him from his foster home or that any of the other statutory requirements … were present."

Justice Charles Trump's concurrence stressed that Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972) was irrelevant here:

In holding that Wisconsin could not compel Amish parents to send their children to school beyond the eighth grade, the Supreme Court [in Yoder] made clear that its decision was based on the combination of the parents' free exercise rights … with the parents' [substantive] due process rights …. The case before us does not involve parental due process rights. Rather, the circuit court was tasked with deciding whether M.B. should remain in a foster placement with his foster parents who, like the parents in Yoder, also happen to be Amish…. Yoder involved a state's attempt to regulate the choices that parents may make concerning their own children's education; the case in front of us does not….

[F]oster parents do not have parental due process rights, such as the right "to direct the religious upbringing" of foster children whom the State places in their care. Foster children remain in the legal custody of the DHS while they are in a foster placement, and the rights and duties of the foster parents are contractually defined in an agreement between the foster parents and the DHS….

Wyclif Farquharson represents the state and Aimee N. Goddard (Legal Aid of West Virginia) represents intervenors.

The post W. Va. High Court on Placing Children with Amish Foster Families appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Not Quite How Get-Out-the-Vote Is Supposed to Work

From Eighth Circuit Judge David Stras (joined by Judges Steven Grasz and Jonathan Kobes) in yesterday's U.S. v. Taylor:

Taylor, who was born in Vietnam, moved to the United States over 20 years ago. Along with her husband, she settled in Sioux City, Iowa, where she was active in the local Vietnamese community.

In 2020, Taylor decided to run her own version of a get-out-the-vote campaign. The idea was to help Vietnamese Americans, some of whom struggled with English and were unfamiliar with our election system, register and vote. Her motives were not purely altruistic: she hoped they would vote for her husband, who was a candidate in the election.

Absentee voting was common during the pandemic. Taylor made it easy by bringing the necessary forms, translating them, having voters complete them, and returning them to the county auditor's office. Once the ballots arrived in the mail, Taylor would come back and help fill them out.

Sometimes, however, Taylor did more than just help. If she learned that a voting-age child was away from home, perhaps at college, she would instruct someone else in the family to complete the necessary forms and then vote on their behalf. For others, she just completed those steps herself. She turned in a total of 26 doctored documents, all with handwriting or signatures that were not the children's own….

Unsurprisingly, the convictions were affirmed.

The post Not Quite How Get-Out-the-Vote Is Supposed to Work appeared first on Reason.com.

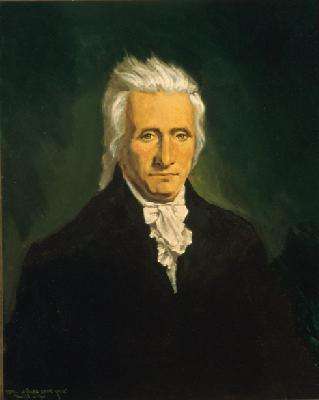

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: November 18, 1811

11/18/1811: Justice Gabriel Duvall takes judicial oath. Professor David P. Currie said that an "impartial examination of Duvall's performance reveals to even the uninitiated observer that he achieved an enviable standard of insignificance against which all other justices must be measured."

Justice Gabriel Duvall

Justice Gabriel Duvall

The post Today in Supreme Court History: November 18, 1811 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Open Thread

[What’s on your mind?]

The post Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

November 17, 2025

[Ilya Somin] The Heritage Foundation Scandal and the Growth of Anti-Semitism on the Right

[Sadly, this trend runs deeper than a few "Groypers" and influencers.]

Today, Princeton professor and prominent conservative political theorist Robert George resigned from the Heritage Foundation board in protest of Heritage President Kevin Robert's defense of anti-Semitic "influencer" Tucker Carlson and his support of Nick Fuentes, an even more virulent right-wing anti-Semite. George's resignation is the latest of a wave of departures from Heritage, including that of my George Mason University colleague Adam Mossoff, who wrote an eloquent statement explaining why he resigned from his position as a visiting fellow at Heritage.

For more detailed accounts of the Heritage controversy and reactions to it, see accounts by Cathy Young at the UnPopulist, and conservative Boston Globe columnist Jeff Jacoby. See also David Bernstein's post about the recent Federalist National Lawyers' Convention panel that addressed the issue of right-wing anti-Semitism, including the Heritage incident.

As Young indicates, the rot at Heritage extends far beyond this one incident, and began years ago. George and Mossoff are far from the first to leave Heritage in reaction to its descent into illiberalism and bigotry. Several leading Heritage scholars and policy analysts departed for similar reasons during the last decade, including Todd Gaziano (founding director of Heritage's Edwin Meese Center for Legal and Judicial Studies), fiscal policy expert Jessica Riedl (then known as Brian Riedl), and foreign policy analyst Kim Holmes (a former Heritage vice president).

I myself was a Heritage intern way back in 1994 (when I was a college student and Heritage was a very different institution). I would not work with them today, and I reached that conclusion years ago, based on their descent into illiberal nativism and nationalism. In December 2022, I turned down an invitation to contribute to the new edition of the Heritage Guide to the Constitution. I told the editor (who is my former student and current co-blogger Josh Blackman) that I was busy. That was true, in so far as it went. But my main reason was revulsion at Heritage's shift towards illiberalism and nationalism. If Heritage was still the organization I remembered from 1994, I might well have found the time to contribute.

Not wishing to provoke an unpleasant exchange, I shied away from fully explaining my reasons to Josh. I was wrong to do so. I should have told the full truth. I hope late is better than never, so I am doing so now.

Sadly, the problem here goes beyond the bigotry of a few "influencers" or the flaws of specific leaders at Heritage and some other conservative institutions. Rather, as Kim Holmes put it, this is the predictable consequence of "replacing conservatism with nationalism." A conservative movement that increasingly defines itself in ethno-nationalist terms as a protector of the supposed interests of America's white Christian majority against immigrants and minority groups cannot readily avoid descending into anti-Semitism, as well.

My Cato Institute colleague Alex Nowrasteh and I wrote about the connections between nationalism and bigotry in some detail in our 2024 article "The Case Against Nationalism." We are working on a follow-up piece that specifically addresses links to anti-Semitism and related current controversies surrounding the conservative movement.

In addition to right-wing anti-Semitism, there are also left-wing versions, some of which have also become more prominent in recent years. I wrote about some of them in a 2023 post on the roots of far-left support for Hamas. Right-wing anti-Semitism should not lead us to turn a blind eye to the left-wing varieties (and vice versa).

In his resignation letter from the Heritage board, Robert George urged his fellow conservatives to be guided by the principles of the Declaration of Independence, especially the idea that "that each and every member of the human family, irrespective of race, ethnicity, religion, or anything else…, is 'created equal' and 'endowed by our Creator with certain unalienable rights.'" George is right to emphasize the importance of equal rights, regardless of race, ethnicity, and religion. Unlike nationalist movements focused on ethnic particularism, the American Founding was based on universal liberal principles. Those principles remain the best protection for Jews and other minority groups. Left and right alike would do well to recommit to them.

The post The Heritage Foundation Scandal and the Growth of Anti-Semitism on the Right appeared first on Reason.com.

[Paul Cassell] Victims' Families Ask the Fifth Circuit to Overturn the Dismissal of the Criminal Case Against Boeing

[My two petitions for writs of mandamus challenge the Justice Department's violation of the Crime Victims' Rights Act and argue for substantive "public interest" review of prosecutors' dismissal motions.]

Last Thursday, families who lost relatives in the crashes of two Boeing 737 aircraft petitioned the Fifth Circuit to reinstate the criminal charge against Boeing. In two petitions I filed, the families asked the Circuit to reverse District Judge O'Connor's approval last week of the Justice Department's motion to dismiss the conspiracy case against Boeing. The petitions explained that the Department violated the Crime Victims' Rights Act (CVRA) by not fully conferring with the families about its dismissal plans—and by concealing a deferred prosecution agreement (DPA) from the families in the initial phases of the case. The petitions also argue that Judge O'Connor failed to fully assess whether dismissing the case was in the "public interest." Today, the Fifth Circuit consolidated the two petitions and ordered the Justice Department and Boeing to respond. In this post, I set out the case's current procedural posture and then the families' arguments.

I've blogged about the Boeing criminal case a number of times before, including here, here, and here. In a nutshell, Boeing lied to the FAA about the safety of its 737 MAX aircraft. The Justice Department charged Boeing with conspiracy for these lies, but then immediately entered into a DPA to resolve the criminal case. In subsequent litigation, the families proved that the 346 passengers and crew on board the two doomed 737 MAX flights were "crime victims" under the CVRA—they had been directly and proximately harmed by Boeing crime. This makes Boeing's conspiracy crime the "deadliest corporate crime in U.S. history," as Judge O'Connor described it.

In the most recent proceedings, the Justice Department moved to dismiss its earlier-filed charge against Boeing in favor of resolution through a non-prosecution agreement (NPA). Earlier this month, I blogged about Judge Reed O'Connor (U.S. District Court for the District of the Northern District of Texas) granting the Justice Department's motion. In his order, Judge O'Connor essentially agreed with many of the factual objections that I have made for the families who lost loved ones because of Boeing's crime. But, reluctantly, Judge O'Connor dismissed the charge, concluding that he lacked a legal basis for blocking the Department's ill-conceived non-prosecution plan.

Last week, the victims' families filed two challenges to the dismissal. I'll focus here on the petition challenging the NPA. A related petition challenges the earlier DPA reached in the case because of the Department's CVRA violations. Here's the introduction to the families' petition challenging the NPA (some citations omitted):

A year-and-half ago, many of the same victims' families filing this petition came to this Court in the same underlying criminal case—seeking enforcement of their CVRA rights and justice for Boeing criminally killing hundreds. See In re Ryan, 88 F.4th 614 (5th Cir. 2023). Following oral argument, this Court denied their petition as "premature," explaining that if and when "judicial approval is sought to resolve the instant case, the district court has an ongoing obligation to uphold the public interest and apply the CVRA." Id. at 627.

Last week, the district court made its decision on resolving the charge below, approving the Government's motion to dismiss the pending conspiracy charge against Boeing. The district court's decision essentially confirmed this Court's prophetic fear that this case's "ultimate outcome as approved by [a] federal court, means no company, and no executive and no employee, ends up convicted of any crime, despite the Government and Boeing's … agreement about criminal wrongdoing leading, the district court has found, to the deaths of 346 crash victims." 88 F.4th at 627.

Now that the issues are no longer "premature," this Court should intervene to protect both the victims' families' CVRA rights and the broader public interest. In granting dismissal, the district court failed to protect the families' CVRA rights, including their rights to reasonably confer and to be treated with fairness. The Government's alleged "conferral" conference calls with the victims' families were perfunctory exercises—lacking in any actual substantive conferring and hiding from the families critical features about the dismissal. Because of these unaddressed CVRA violations, this Court should reverse the district court.

This Court should also reverse because the district court misunderstood this Court's precedents regarding the need to protect the public interest when reviewing dismissal motions. The district court seemed to construe this Court's precedents as requiring it to approve the Government's motion to dismiss so long as the prosecutors had "not acted with bad faith" and had "given more than mere conclusory reasons" for the dismissal." Op. at 9. But this parsimonious reading ignored this Court's prior instructions in this very case—that under "Supreme Court and prior Fifth Circuit precedent … district judges are empowered to deny dismissal when clearly contrary to manifest public interest …" and that thus district judges will "vigilantly … enforce the public interest." Ryan, 88 F.4th at 626-27 (internal citation omitted).

Here, the district court found that the victims' families provided "compelling" reasons to deny the dismissal. Id. at 8. And yet, the district court reluctantly concluded that it was somehow required to give its approval to an agreement that "fails to secure the necessary accountability to ensure the safety of the flying public." Op at 6. In other words, the district court thought it had no choice but to lend its imprimatur to the dismissal. The district court was wrong. It had the power to reject the stunning injustice inherent in simply dismissing the charge for "the deadliest corporate crime in U.S. history." To protect the manifest public interest, this Court should reverse.

One of the most important parts of this petition is its challenge to the Justice Department's unprecedented approach of entering into a binding non-prosecution agreement with Boeing before securing district court approval for its motion to dismiss. I've blogged about this important issue in two earlier posts, here and here. The families' petition explains why the Fifth Circuit should reverse to protect the long-standing practice of judicial review of Justice Department dismissal motions:

The district court's approval of the Government's "unprecedented" no-further-

prosecution provision effectively guts Rule 48(a). Even before the district court ruled, the Government and Boeing had devised an agreement in which the Government promised not to further prosecute Boeing—even if the district court thereafter denied the motion to dismiss. Never before in Rule 48(a)'s eighty-year history has the Government entered such a preemptive agreement—much less received after-the-fact judicial approval for its ploy. In Ryan, this Court recounted that any contractual agreements, such as NPAs, "derogate neither court authority nor statutory rights." 88 F.4th at 625. But if this Court approves the Government's contractual end-run around Rule 48(a), this scheme will no doubt "become the blueprint for all future dismissal motions in federal criminal prosecutions." This disturbing subterfuge alone renders the Government's dismissal motion clearly contrary to manifest public policy—the long-standing public policy provided by Rule 48(a) of judicial review before the Government can terminate a prosecution.

The latest status is that the Fifth Circuit today entered a brief procedural order. The Circuit consolidated the two petitions and directed the Justice Department and Boeing to respond to the families' petitions by December 17. I then have three weeks to respond.

I hope that the Fifth Circuit will ultimately rule in favor of the victims' families and block the miscarriage of justice that would result if the deadliest corporate crime in U.S. history simply goes unpunished.

The post Victims' Families Ask the Fifth Circuit to Overturn the Dismissal of the Criminal Case Against Boeing appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Friend-of-the-Court Brief in Massachusetts' Social Media Addiction Lawsuit Against Instagram

Prof. Jane Bambauer (Florida) and I just submitted this amicus brief in Commonwealth v. Meta, which is now pending before the Massachusetts high court (and which is reviewing this trial court order that had let the claim go forward); thanks to Jay M. Wolman (Randazza Legal Group, PLLC) for his invaluable pro bono help as local counsel, and to law students John Joonhee Cho and Jonathan Tao, who worked on the brief. Here's the Summary of Argument:

[1.] Social media platforms create expressive products. Their choices about how to craft and format those products are presumptively protected by the First Amendment.

That protection extends to the very features the Commonwealth demands Meta remove. Push notifications, for instance, allow social media platforms to speak to users about new content. Endless scrolling, autoplay, and ephemeral features let social media platforms decide how users see speech on the platforms, just as a newspaper chooses how to format the front page or a film director chooses whether to break up a movie into multiple episodes. Whether these features constitute Meta's own direct speech, or are structural decisions about how Meta presents third-party speech, Moody v. NetChoice, LLC, 603 U.S. 707, 716-17 (2024), they stem from constitutionally protected decisions about where, when, and how speech is communicated (and, as to the "like" button, what speech is communicated).

[2.] A social media platform's design features shape how users speak through the platform. Push notifications amplify user speech by informing other users about the posts. "Likes" give users the ability to express their views about a post and see what others think about the post. "Likes" also communicate to social media platforms about what content the user enjoys, and thus help platforms determine what further content to show the user. And users may benefit from features like endless scrolling or autoplay because those features make information easier to access.

The same is true of users who are minors. Like adults, "minors are entitled to a significant measure of First Amendment protection, and only in relatively narrow and well-defined circumstances may government bar public dissemination of protected materials to them." Erznoznik v. Jacksonville, 422 U.S. 205, 212-13 (1975) (citation omitted). [P]rotected speech "cannot be suppressed solely to protect the young from ideas or images that a legislative body thinks unsuitable for them." Brown v. Ent. Merchs. Ass'n, 564 U.S. 786, 794 (2011) (citation omitted). The same principle governing the violent images in Brown—Brown struck down a restriction on violent video games, regardless of the "ideas" the games conveyed—applies to other display and content features such as autoplay, "likes," and endless scrolling.

[3.] The Commonwealth's lawsuit improperly asks judges and juries to second-guess Meta's choices about how it and its users will communicate. By concluding that it was legally sufficient for the Commonwealth to allege that "the harm alleged could be reasonably avoided and that such harm was not outweighed by Instagram's countervailing benefits," Mem. & Order 23, Meta Br. 84, the Superior Court essentially concluded that Meta's speech can be restricted if it is seen as negligent. But this Court and other courts have recognized that the First Amendment bars such negligence claims based on speech—for instance, claims that a late-night show featuring a dangerous stunt was negligently aired, a magazine describing autoerotic asphyxiation was negligently published, or a movie depicting violent youth gangs was negligently distributed. This Court should likewise recognize that judges and juries ought not be able to impose liability on Meta based on a theory that its speech was "unfair," Mem. & Order 21, Meta Br. 82, or failed a harm-benefit negligence-style balancing analysis.

The "basic principles of freedom of speech and the press, like the First Amendment's command, do not vary when a new and different medium for communication appears." Brown, 564 U.S. at 790 (cleaned up). The protections against state tort law offered to TV shows, magazines, and movies equally protect social media platforms.

[4.] This Court should likewise reject the Commonwealth's claims that Meta's speech expressing its views about the supposed harm and value of its (and its users') fully protected speech was "deceptive." Mem. & Order 23, Meta Br. 84. Authors, publishers, and distributors of books, films, songs, and the like must have full First Amendment protection in discussing whether their works are suitable for minors (or for other readers, viewers, or listeners). The same must be true for social media platforms.

This Court should therefore reverse the Superior Court and dismiss the Commonwealth's Complaint.

And here's the Argument:

[I.] Social media platforms create expressive products presumptively protected under the First Amendment

The First Amendment protects the editorial choices that publishers and editors make when they "select and shape other parties' expression into their own curated speech products." Moody, 603 U.S. at 717. That "principle does not change because the curated compilation has gone from the physical to the virtual world." Id. Social media platforms make choices about what to "include and exclude, organize and prioritize—and in making millions of those decisions each day, produce their own distinctive compilations of expression." Id. at 716. "[L]aws curtailing [platforms'] editorial choices must meet the First Amendment's requirements." Id. at 717. "[T]he editorial function itself is an aspect of speech." Id. at 731 (cleaned up).

The Commonwealth's lawsuit seeks to "curtail[]" those "editorial choices." Id. at 717. Meta organizes and presents its content through the infinite scroll, autoplay, push notification, and "like" features. Push notifications let Meta communicate information directly to its users. Infinite scroll lets Meta communicate information in a particular way. "[L]ike" buttons are visual elements that Meta communicates to users, and means for users to communicate information back to Meta. By attacking Meta's choices about how to communicate, the Commonwealth "prevents a platform from compiling the third-party speech it wants in the way it wants, and thus from offering the expressive product that most reflects its own views and priorities." Id. at 718 (cleaned up).

The Commonwealth seeks to avoid First Amendment scrutiny by distinguishing between Meta's "content moderation or algorithm-creating procedures," Commonwealth's Resp. Br. 46, and its chosen design features. The Commonwealth characterizes Meta's design features as "independent of content" and therefore not within Moody's protection. Id. at 47.

But this is a false distinction. Just as Meta may curate content by expressing disapproval through its content moderation policies, Meta may approve of and encourage speech through its design features. For example, rather than expressly policing or prohibiting politically biased content, Meta could implement a "community note" feature allowing users to flag and respond to factual claims. Though a "community note" feature operates as a design feature rather than an express policy from Meta, it might function more effectively in fostering Meta's favored forms of speech. Similarly, the "like" function is a design feature that helps shape the content of Meta products, by adding extra information to each post (the number of likes), by encouraging users to post popular content that draws more likes, and by encouraging users to read more popular content that has drawn more likes.

Even if such editorial choices were not necessarily treated as communicative themselves, they are protected under the First Amendment because they are decisions about how to effectively present and distribute speech. A performer may decide to use sound amplification to reach a larger group of listeners. Ward v. Rock Against Racism, 491 U.S. 781, 791 (1989) (treating sound-amplification regulation as a speech restriction, albeit one that may be content-neutral and subject to intermediate scrutiny). Likewise, a speaker may choose to canvass door-to-door rather than using billboards or mass mailings, Watchtower Bible & Tract Soc'y of N.Y., Inc. v. Vill. of Stratton, 536 U.S. 150, 164 (2002) (striking down ordinance restricting canvassing as a speech restriction). Such decisions are generally protected by the First Amendment, even though they are decisions about how and where to communicate rather than themselves being communication.

[II.] Social media users are entitled to First Amendment protections against governmental restrictions on communicative features a social media platform may offer

The changes that the Commonwealth demands that Meta impose would also operate as restrictions on users' ability to speak. The "like" feature enables users to convey speech with a certain content: It "literally causes to be published the statement that the [u]ser 'likes' something, which is itself a substantive statement." Bland v. Roberts, 730 F.3d 368, 386 (4th Cir. 2013). Similarly, push notifications enable users to better direct others to their content.

Users also have First Amendment interests as listeners in Meta's design features. "[T]he First Amendment protects the public's interest in receiving information." Pac. Gas & Elec. Co. v. Pub. Utils. Comm'n of Cal., 475 U.S. 1, 8 (1986) (plurality opinion). {See also Va. State Bd. of Pharmacy v. Va. Citizens Consumer Council, Inc., 425 U.S. 748, 756 (1976) (concluding that commercial speech is protected because "protection afforded is to the communication, to its source and to its recipients both"); id. at 757 ("[I]n Procunier v. Martinez, 416 U.S. 396, 408-09 (1974), where censorship of prison inmates' mail was under examination, we thought it unnecessary to assess the First Amendment rights of the inmates themselves, for it was reasoned that such censorship equally infringed the rights of noninmates to whom the correspondence was addressed."); First Nat'l Bank of Boston v. Bellotti, 435 U.S. 765, 775–76, 783 (1978) (concluding that corporate speech is protected "based not only on the role of the First Amendment in fostering individual self-expression but also on its role in affording the public access to discussion, debate, and the dissemination of information and ideas"); Lamont v. Postmaster Gen., 381 U.S. 301, 305, 307 (1965) (relying on "the addressee's First Amendment rights" rather than the sender's, where the sender was a foreign government and thus might not have had First Amendment rights); id. at 307-08 (Brennan, J., concurring) (stressing that it is not clear whether the First Amendment protects "political propaganda prepared and printed abroad by or on behalf of a foreign government," but concluding that the law was unconstitutional because it violated the recipients' "right to receive" information, regardless of the senders' rights to speak).} Like the "protected books, plays, and movies that preceded them," Meta's chosen design features "communicate ideas" to users "through features distinctive to the medium." Brown, 564 U.S. at 790. For example, "likes" signal to a user the approval of others. Push notifications bring platform speech to a user's attention. Removing or limiting these features makes it harder for users to exercise their right to receive information.

Likewise, infinite scroll and auto-play make it easier for users to see material. They also make the browsing experience more exciting and thus lead the user to want to keep browsing; this, too, is a protected form of editorial expression. Authors of serialized fiction (print or visual) often use cliffhangers to keep people coming back to the next episode, and creators in every medium have long used promises of interesting future content if only the listener will "stay tuned."

To be sure, infinite scroll and auto-play only make it slightly easier for users to keep browsing, since even without these features a user could just get more posts or see videos simply by clicking. But by the same token, any restrictions on infinite scroll and auto-play would likewise at most slightly (and hypothetically) serve whatever interests the Commonwealth is trying to serve by imposing such restrictions. The U.S. Supreme Court has recognized that, even under intermediate scrutiny, a restriction is unconstitutional to the extent that it "provides only the most limited incremental support for the interest asserted" and thus only a "marginal degree of protection." Bolger v. Youngs Drug Products Corp., 463 U.S. 60, 73 (1983) (relying partly on this reasoning in striking down restriction aimed at shielding children from contraceptive ads). Likewise, the Court has struck down speech restrictions, even under intermediate scrutiny, when "there was 'little chance' that the speech restriction could have directly and materially advanced its aim," Greater New Orleans Broad. Ass'n, Inc. v. United States, 527 U.S. 173, 193 (1999) (quoting Rubin v. Coors Brewing Co., 514 U.S. 476, 489 (1995)), when the restriction failed to "alleviate [the asserted harms] to a material degree," Edenfield v. Fane, 507 U.S. 761, 770-71 (1993), when the restriction "provide[d] only ineffective or remote support for the government's purpose," Cent. Hudson Gas & Elec. Corp. v. Pub. Serv. Comm'n of N.Y., 447 U.S. 557, 564 (1980), and when "[t]he benefit to be derived from the" restriction was "minute" and "paltry," City of Cincinnati v. Discovery Network, Inc., 507 U.S. 410, 417-18 (1993).

The Commonwealth's proposed limitations also remain constitutionally suspect even when they purport to protect children. Brown made clear that speech not "subject to some other legitimate proscription cannot be suppressed solely to protect the young from ideas or images that a legislative body thinks unsuitable for them." 564 U.S. at 795. That extends to "likes," push notifications, infinite scroll, autoplay, and other items that the Commonwealth views as "unsuitable for" "the young" at least as much as to the violent video games involved in Brown.

[III.] Plaintiff's unfairness claim is in essence a speech-based negligence claim that the First Amendment precludes

"[C]ourts have made clear that attaching tort liability to protected speech can violate the First Amendment." James v. Meow Media, Inc., 300 F.3d 683, 695 (6th Cir. 2002) (citing N.Y. Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 265 (1964)). This includes negligence and related torts, see id. at 689-90, as well as defamation, N.Y. Times, 376 U.S. at 265, intentional infliction of emotional distress, Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443, 451 (2011), false light invasion of privacy, Cantrell v. Forest City Pub. Co., 419 U.S. 245, 249 (1974), and interference with business relations,

NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware Co., 458 U.S. 886, 928 (1982). The Commonwealth's unfairness claim against Meta is in essence a negligence claim. To assess the unfairness claim under M.G.L. ch. 93A, the Superior Court considered whether "the risks of the platform outweigh its benefits" and whether Meta's design decisions were "unreasonable." Mem. & Order 23 (cleaned up), Meta Br. 84. This is the very sort of risk-benefit and reasonableness analysis called for in a negligence case. See, e.g., Mounsey v. Ellard, 363 Mass. 693, 708 (1973).

This Court recognized the First Amendment limits on such negligence claims in Yakubowicz v. Paramount Pictures Corporation, 404 Mass. 624 (1989), where it rejected a claim that a film depicting gang violence was negligently produced, distributed, and advertised, resulting in a stabbing that left two youths dead. The court concluded that "liability may exist for tortious conduct in the form of speech" only when the speech falls within one of the "narrowly defined" "recognized exceptions to First Amendment protection," such as incitement. Id. at 630. Because the speech did not fit within any of the exceptions, Paramount, as a matter of law, "did not act unreasonably in producing, distributing, and exhibiting [the movie]." Id. at 631. See also DeFilippo v. NBC, Inc., 446 A.2d 1036, 1038, 1040 (R.I. 1982)

(rejecting a claim that a TV program was negligent for permitting a dangerous stunt to be broadcast and for failing to warn plaintiffs' child of the dangers of the stunt, on the grounds that the speech did not fall within one of the "classes of speech which may legitimately be proscribed," which is to say a First Amendment exception); Herceg v. Hustler Mag., Inc., 814 F.2d 1017, 1019, 1024 (5th Cir. 1987) (rejecting liability for "[m]ere negligence," as opposed to constitutionally unprotected speech such as intentional incitement of illegal conduct, even when the speech involved a porn magazine's discussion of autoerotic asphyxiation, and led an adolescent reader to engage in such an act and accidentally kill himself).

Nor is this First Amendment protection for speech lost even if a viewer or listener does something seriously harmful to third parties in a way that was in part caused by the speech. Thus, for instance, when plaintiffs claimed that a video game helped lead a 14-year-old player to commit murder, on the theory that defendants acted "negligently" and "communicated . . . a disregard for human life and an endorsement of violence," the First Amendment precluded such liability. James, 300 F.3d at 695, 696-97. The same was true for claims that a rap song helped motivate a listener to murder a police officer, see Davidson v. Time Warner, Inc., No. Civ.A. V-94-006, 1997 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 21559 at *38 (S.D. Tex. Mar. 31, 1997), or that

the film The Fast and the Furious led a viewer to race and crash his car, see Widdoss

v. Huffman, 62 Pa. D. & C.4th 251, 257 (2003), or that the TV program Born Innocent led some underage viewers to sexually attack a small child in copying a scene shown on the program, Olivia N. v. NBC, Inc., 126 Cal. App. 3d 488, 492-94 (1981). And this logic applies equally to self-harm, whether accidental or intentional: The First Amendment precluded liability, for instance, when an 11-year-old partially blinded himself when performing a stunt that he had seen on the Mickey Mouse Club TV program, see Walt Disney Prods., Inc. v. Shannon, 247 Ga. 402, 404 (1981); when a 13-year-old hanged himself when simulating a stunt from The Tonight Show, DeFilippo, 446 A.2d at 1038; when a 14-year-old hanged himself when simulating behavior described in Hustler, Herceg, 814 2d at 1023; or when a 19-year-old shot himself after listening to a song called "Suicide Solution," see McCollum v. CBS, Inc., 202 Cal. App. 3d 989, 1003 (1988).This makes sense. Allowing negligence claims based on otherwise protected speech—speech that does not fall within one of the narrow First Amendmentexceptions—"would invariably lead to self-censorship by broadcasters in order to remove any matter that may . . . lead to a law suit." DeFilippo, 446 A.2d at 1041. This would in turn violate defendants' "right to make their own programming decisions" (even when the defendants are broadcasters, and thus seen as having a more "limited" First Amendment right than other speakers). Id.. And it would violate "the paramount rights of the viewers to suitable access to social, esthetic, moral, and other ideas and experiences." Id. at 1041-42 (citations omitted). Such negligence liability would "open the Pandora's Box" and "have a seriously chilling effect on the flow of protected speech through society's mediums of communication." Walt Disney, 247 Ga. at 405. "Numerous courts have pointed out that any attempt to impose tort liability on persons engaged in the dissemination of protected speech involves too great a risk of seriously chilling all free speech." Waller v. Osbourne, 763 F. Supp. 1144, 1151 (M.D. Ga. 1991), aff'd, 958 F.2d 1084

(11th Cir. 1992).

The cost-benefit balancing at the heart of a negligence claim is also too vague to be constitutionally permissible. "Crucial to the safeguard of strict scrutiny" required in First Amendment cases "is that we have a clear limitation, articulated in the legislative statute or an administrative regulation, to evaluate." James, 300 F.3d at 697. No such clear limitation is present when a factfinder "evaluating [plaintiff's] claim of negligence would ask whether the defendants took efficient precautions . . . that would be less expensive than the amount of the loss." Id.

The Commonwealth's negligence claim is not distinguishable from the preceding cases on the basis that it targets "design" rather than "content." The First Amendment protects choices about how to present content, not just the content itself. See Ward, 491 U.S. at 791 (recognizing the volume of speech as presumptively protected); Watchtower, 536 U.S. at 164-65 (recognizing the means of delivering speech, canvassing, as presumptively protected). Social media platforms make the very same choices when deciding what design features to offer, which requires that even content-neutral restrictions on these choices must be judged at least under intermediate scrutiny.

Of course, the Commonwealth has broad authority over purely commercial behavior that does not involve speech. "Laws that target real-world commercial activity need not fear First Amendment scrutiny. Such run-of-the-mill economic regulations will continue to be assessed under rational-basis review." Dana's R.R. Supply v. Att'y Gen., Fla., 807 F.3d 1235, 1251 (11th Cir. 2015). But this case does not concern a run-of-the-mill economic regulation. This case concerns a regulation of the content and presentation of speech. In such a situation, the government may not "criminaliz[e] speech" unless the speech falls within a First Amendment exception or the speech restriction otherwise passes heightened scrutiny. Id. As the cases cited above show, the same heightened scrutiny must apply to civil liability for such speech, too.

[IV.] Companies' views about the alleged harm and value of their speech products are entitled to full First Amendment protection

The Commonwealth is seeking to prevent Meta from opining on the state of the evidence concerning addiction and mental health stemming from the content and presentation of speech on Meta's platforms. In fact, the Commonwealth argues that Meta must affirmatively warn about a risk whose existence the company vehemently disputes. Ordinarily, the First Amendment provides "less protection to commercial speech" than it does to noncommercial speech. See Bolger, 463 U.S. at 64. But "a different conclusion may be appropriate in a case where the [commercial speech] advertises an activity itself protected by the First Amendment." Id. at 67 n.14. For instance, Bolger noted that the Court has held that an "advertisement for [a] religious book cannot be regulated as commercial speech." Id. (citing Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U.S. 105 (1943), and Jamison v. Texas, 318 U.S. 413 (1943)).

Likewise, the Court has held that speech does not retain "its commercial character when it is inextricably intertwined with otherwise fully protected speech"; any restriction on such speech must instead apply the "test for fully protected expression." Riley v. Nat'l Fed'n of the Blind of N.C., Inc., 487 U.S. 781, 796 (1988). Riley so concluded as to fundraising by charities, which consisted of requests for money coupled with noncommercial expression advocating for the charity's mission. Id. at 795 (holding that compelling fundraisers to state to donors what portion of revenues goes to fundraising was a speech compulsion that had to be judged under strict scrutiny). The same logic applies to statements by speech producers that express controversial opinions about their speech products' merits.

As discussed in the preceding Parts, Instagram, like a book, consists of fully protected speech—both the speech of users and the expressive curation and layout decisions of Meta. Just as the creators and distributors of films, books, newspapers, and the like are entitled to express their opinions that their works are valuable rather than harmful, Meta is entitled to do the same without that becoming restrictable commercial speech, contrary to the Commonwealth's assertion in Count Two.

Whether material is "safe[]" for minors, Mem. & Order 24, Meta Br. 85, is a hotly debated topic, as to films, books, music, social media platforms, and other speech products. Different people have sharply different opinions on these questions. All people and organizations, including the distributors of the speech, must be fully free to express those opinions.

Critics of controversial books such as Gender Queer, see, e.g., Penguin Random House LLC v. Robbins, 774 F. Supp. 3d 1001, 1033 (S.D. Iowa 2025), or of social media platforms are entitled to express their views about whether those books or platforms are suitable for minors, without risking liability if a jury or judge concludes those views are incorrect and therefore "deceptive." Likewise, the publishers of Gender Queer or the operators of the platform must have the same right. The same is true with regard to statements about whether the book publishers or social media platforms "prioritize the safety and well-being of [their] young users [or readers] over profits," Mem. & Order 4, Meta Br. 65, or statements disputing whether some expressive work is so appealingly designed as to be "addictive," Id.

To be sure, the government may sometimes regulate advertisements for protected speech similarly to other advertisements, as long as the regulation is essentially content-neutral (setting aside the regulation's drawing a commercial/noncommercial speech line). For example, consider a billboard ordinance that allows "political, ideological or other noncommercial message[s]" on billboards, Charles v. City of Los Angeles, 697 F.3d 1146, 1149 (9th Cir. 2012) (citation omitted), but not commercial messages. In Charles, the Ninth Circuit concluded that a billboard advertising a television program could be treated the same as a billboard advertising any other product. Id. at 1155.

But the court stressed that, "[s]ignificantly, the City does not seek to regulate the content of [the program] or to single out [its advertisements] in particular, but only to enforce broadly applicable guidelines that govern the placement of all commercial advertising." Id. at 1156. In contrast, the Commonwealth here is seeking to regulate the content of Meta products (see Parts I-III above) and is singling out Meta advertisements in particular as being supposedly "deceptive."

Nor can the Commonwealth's case be saved by arguing that Meta "created an over-all misleading impression through failure to disclose material information," Mem. & Order 24, Meta Br. 85. Meta has no legal duty to "disclose" hotly-contested claims about whether Instagram is harmful to children—again, just as book publishers, filmmakers, or music distributors have no duty to disclose such claims about their books, films, or music (at least unless the speech falls within a First Amendment exception). See, e.g., Book People, Inc. v. Wong, 91 F.4th 318, 324, 339 (5th Cir. 2024) (striking down requirement that "school book vendors who want to do business with Texas public schools to issue sexual-content ratings for all library materials they have ever sold"); Video Software Dealers Ass'n v. Schwarzenegger, 556 F.3d 950, 965-66 (9th Cir. 2009) (likewise as to requirement that video game distributors label games deemed to be unduly "violent"), aff'd, 564 U.S. 786 (2011); Ent. Software Ass'n v. Blagojevich, 469 F.3d 641, 653 (7th Cir. 2006) (likewise). This is why the existing schemes through which publishers sometimes include ratings on their works are voluntary, Brown, 564 U.S. at 803, rather than legally compulsory.

The First Amendment protects "both the right to speak freely and the right to refrain from speaking at all." Wooley v. Maynard, 430 U.S. 705, 714 (1977). Even when commercial advertising promotes nonspeech products, mandatory disclosures are constitutional only when they require the disclosure of "'purely factual and uncontroversial information.'" Nat'l Ass'n of Wheat Growers v. Bonta, 85 F.4th 1263, 1266, 1276-80 (9th Cir. 2023) (quoting Zauderer v. Off. of Disciplinary Couns. of Sup. Ct. of Ohio, 471 U.S. 626, 651 (1985)) (holding that the First Amendment precluded a requirement that herbicide sellers label certain products as containing "known carcinogens," partly because such a requirement was not "purely factual and uncontroversial"). And this is even more clear when the mandate applies to a speech distributor or producer and forces such speakers to "opine on potential speech-based harms" from their products. NetChoice, LLC v. Bonta, 113 F.4th 1101, 1119 (9th Cir. 2024) (striking down such a mandate for social media platforms). "[A] business's opinion about how its services might expose children to harmful content online is not 'purely factual and uncontroversial.'" Id. at 1120 (quoting Zauderer, 471 U.S. at 651). See also Video Software Dealers Ass'n, 556 F.3d at 967 (striking down a requirement that violent videos be labeled "18," to indicate that they are suitably only for adults, because this was not "factual information").

If at some point the Commonwealth's claims about the alleged harms of various social media features (or of social media as a whole) are established to be factual and noncontroversial, the government might be able to require social media platforms to acknowledge such harms in their advertisements. But just as Meta cannot be prevented from expressing controversial opinions about its speech products under the First Amendment, it cannot be mandated to disclose non-factual or controversial claims about its products either.

CONCLUSION

The Commonwealth claims the power to regulate a social media platform's design decisions concerning where, when, and how speech is communicated—and in the case of "likes," what speech is communicated. But the First Amendment provides protections against speech-based negligence claims, as this Court and other courts have recognized. And the First Amendment also protects speech producers' expressing their views about whether their speech is valuable and harmful.

The Commonwealth's attempt to regulate Meta's speech thus fails heightened First Amendment scrutiny. The decision below should therefore be reversed.

The post Friend-of-the-Court Brief in Massachusetts' Social Media Addiction Lawsuit Against Instagram appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Journal of Free Speech Law: "The Moving Goalposts of Public-Employee Speech: Kennedy v. Bremerton School District and Demonstrative Prayer," by Jared M. Hirschfield

This new article [UPDATE: link fixed] is here. The Introduction:

Over the past decade, the Roberts Court has sought to disrupt two major domains of the First Amendment: the Religion Clauses and free speech. These interests have recently merged to yield a flurry of cases raising complex questions at the intersection of free speech and religious liberty. This Article argues that the Court's emerging approach to such cases threatens to unravel longstanding free-speech doctrine and the core values underlying it.

These dangers are on full display in the Court's analysis of a recent case addressing the constitutional quandary posed by the religious speech of public employees. Kennedy v. Bremerton School District involved Joseph Kennedy, a high-school football coach and devout Christian who, after each game, knelt in prayer at midfield, joined by players, adult community members, and the media. After repeatedly requesting that Kennedy refrain from this so-called "demonstrative prayer," Bremerton School District placed Kennedy on administrative leave due to its concerns about the consequences of his behavior, including the difficulty of ensuring security at the games and the risk that the District would be violating the Establishment Clause by allowing Kennedy to continue. Kennedy refused to reapply for his coaching job and alleged that the District had violated his free-speech and free-exercise rights.

The Supreme Court has long recognized that public employees like Kennedy enjoy some degree of free-speech protection. In recognizing this qualified protection, the Court seeks to strike a careful balance. On one hand, employee-speech doctrine vindicates public employees' free-speech rights. On the other, it aspires to vest in school districts, government agencies, and other public institutions the leeway to manage themselves—and their workforces—effectively. To negotiate this fundamental tension, for public-employee speech, the Court has eschewed the stringent review typical of other areas of free-speech doctrine in favor of a more flexible balancing test: When a public employee speaks as a citizen on a matter of public concern, the Court balances the "interests of the [employee] … in commenting upon matters of public concern" against "the interests of the State … in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employees." However, when an employee speaks as part of her public employment, the employee is owed no free-speech protections at all because it is, in effect, the government—not the employee—speaking.

Kennedy appreciated little of this fragile détente. Taking up both Kennedy's free-speech and free-exercise claims, the Court granted certiorari on the questions of "whether a public-school employee who says a brief, quiet prayer by himself while at school and visible to students is engaged in government speech that lacks any First Amendment protection" and "whether, assuming that such religious expression is private and protected by the Free Speech and Free Exercise Clauses, the Establishment Clause nevertheless compels public schools to prohibit it." Justice Gorsuch authored an opinion for a six-Justice majority holding that the District's actions violated Kennedy's free-speech and free-exercise rights, and that the District's Establishment Clause interest failed to save its otherwise unconstitutional action.

Rather than evaluate Coach Kennedy's claims on their own merit and according to the doctrine applicable to each, Justice Gorsuch flattened the claims into a zero-sum, culture-war battle over religious liberty. For Gorsuch, Kennedy was no tough case. It was, boiled down, a "government entity [seeking] to punish an individual for engaging in a brief, quiet, personal religious observance doubly protected by the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses of the First Amendment." As Gorsuch saw it, in disciplining Coach Kennedy, the school district had flouted the principle that "[r]espect for religious expressions is indispensable to life in a free and diverse Republic—whether those expressions take place in a sanctuary or on a field, and whether they manifest through the spoken word or a bowed head." Religious expression is religious expression, Gorsuch told us—"form" and "context" be damned.

And yet, Gorsuch's creative deviations in Kennedy notwithstanding, the Court's well-established precedents provide a relatively tidy doctrinal framework for each of Kennedy's claims. Neither of those frameworks prescribes the analysis Gorsuch performs in Kennedy.

On the free-speech front, the Court has held that public employees receive free-speech protections only when speaking "as citizens." Public employees who instead speak "pursuant to their official duties" speak not as citizens but as employees and are not "insulate[d] … from employer discipline" at all. Further, a public employee may receive protection only for "speech on a matter of public concern"—not for speech on "private matters." This distinction "must be determined by the content, form, and context of a given statement, as revealed by the whole record." Fifty years of precedent can thus be synthesized into a (deceptively) straightforward rule: A public employer's disciplinary actions trigger the First Amendment only when an employee speaks (1) as a citizen (2) on a matter of public concern. If both conditions are satisfied, the Court then conducts "particularized balancing," weighing the employee's particular speech act against the government's particular interests in regulating it.

The free-exercise framework is similarly streamlined. If a rule or action that burdens free exercise is neutral and generally applicable, it is subject only to rational-basis review. However, if the rule or action is either not neutral or not generally applicable, it is subject to strict scrutiny and likely fails. A government policy is not neutral if it is "specifically directed at … religious practice," is "discriminat[ory] on its face," or otherwise has "religious exercise" as its "object." And a government policy fails the "generally applicable" requirement if the state allows for individualized exemptions from the policy but denies a religious exemption, or exempts comparable secular conduct.