Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 7

November 20, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: November 20, 1910

11/20/1910: Justice William Henry Moody retired.

Justice William Henry Moody

Justice William Henry MoodyThe post Today in Supreme Court History: November 20, 1910 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Open Thread

[What’s on your mind?]

The post Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

November 19, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Chancellor James Kent on Hamilton's Federalist No. 77 and Modern Academic Commentary

[A guest post from Professor Seth Barrett Tillman.]

I am happy to pass along this guest post from Professor Seth Barrett Tillman, which concerns how best to understand Alexander Hamilton's analysis in Federalist No. 77. This topic is once again very timely in light of the ongoing litigation over the President's removal power. And, once again, Tillman offers a correction to scholars who misread Hamilton. Make sure you read till the end.

***

As readers of this blog will know, there is a long-standing debate about the scope of the President's and Senate's appointment and removal powers. That debate has been shaped by the language of the Appointments Clause (referring to the Senate's "advice and consent" power), ratification era debates, including Hamilton's Federalist No. 77, debates in the First Congress, and, of course, subsequent executive branch practice, legislation, judicial decisions, and commentary.

In 2010, I attempted to make a modest contribution to this debate. Without opining either on the constitutional issue per se or on the meaning of the Appointments Clause, I argued that Hamilton's Federalist No 77 was not speaking to removal at all—at least, not removal as we think about it today.

In Federalist No. 77, Hamilton stated: "The consent of th[e] [Senate] would be necessary to displace as well as to appoint." 20th century and 21st century commentators have uniformly understood Hamilton's "displace" language as speaking to "removal." (Albeit, there have been a few exceptions over the last one hundred years.) My modest contribution was to point out that "displace" has two potential meanings. "Displace" can mean "remove," but it can also mean "replace." This latter meaning is, in my view, more consistent with the overall language of the entire paragraph in which Hamilton's "displace as well as to appoint" statement appears.

Hamilton wrote:

It has been mentioned as one of the advantages to be expected from the co-operation of the senate, in the business of appointments, that it would contribute to the stability of the administration. The consent of that body would be necessary to displace as well as to appoint. A change of the chief magistrate therefore would not occasion so violent or so general a revolution in the officers of the government, as might be expected if he were the sole disposer of offices. Where a man in any station had given satisfactory evidence of his fitness for it, a new president would be restrained from attempting a change, in favour of a person more agreeable to him, by the apprehension that the discountenance of the senate might frustrate the attempt, and bring some degree of discredit upon himself. Those who can best estimate the value of a steady administration will be most disposed to prize a provision, which connects the official existence of public men with the approbation or disapprobation of that body, which from the greater permanency of its own composition, will in all probability be less subject to inconstancy, than any other member of the government. [bold and italics added]

Likewise, Hamilton, on other occasions, used "displace" in the "replace" sense. See, e.g., Letter from Alexander Hamilton, Concerning the Public Conduct and Character of John Adams, Esq. President of the United States [24 October 1800] ("But the truth most probably is, that the measure was a mere precaution to bring under frequent review the propriety of continuing a Minister at a particular Court, and to facilitate the removal of a disagreeable one, without the harshness of formally displacing him."); Alexander Hamilton to the Electors of the State of New York [7 April 1789] ("It has been said, that Judge Yates is only made use of on account of his popularity, as an instrument to displace Governor Clinton; in order that at a future election some one of the great families may be introduced.").

Similarly, Justice Story expressly adopted the "replace" view of Federalist No. 77. Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States §§ 1532–1533 (Boston, Hilliard, Gray, & Co. 1833) ("§ 1532. … [R]emoval takes place in virtue of the new appointment, by mere operation of law. It results, and is not separable, from the [subsequent] appointment itself. § 1533. This was the doctrine maintained with great earnestness by the Federalist [No. 77] . . . ." (emphasis added)).

More recently, it appears, although one cannot be entirely sure, that Justice Kagan has adopted the "replace" interpretation of Federalist No. 77. Kagan wrote:

In Federalist No. 77, Hamilton presumed that under the new Constitution '[t]he consent of [the Senate] would be necessary to displace as well as to appoint' officers of the United States. He thought that scheme would promote 'steady administration': 'Where a man in any station had given satisfactory evidence of his fitness for it, a new president would be restrained' from substituting 'a person more agreeable to him.' [quoting Federalist No. 77] [bold added]

Seila Law LLC v. CFPB, 591 U.S. 197, 261, 270 (2020) (Kagan, J., concurring in the judgment with respect to severability and dissenting in part). "Substituting" is, in my opinion, akin to "replace."

However, in a 2025 article in California Law Review (at note 225), Professors Joshua C. Macey and Brian M. Richardson discuss both Federalist No. 77 and Joseph Story's interpretation of Federalist No. 77. Macey and Richardson wrote: "Joseph Story's Commentaries interpreted Federalist 77's reference to 'dismissal' to refer plainly to removal." There are three errors here. First, why is "dismissal" in quotation marks? It does not appear either in Federalist No. 77 or in Story's Commentaries, at least not in the sections under our consideration. Second, Story adopted the "displace" means "replace" view. And third, the issue is not "plain." We all make mistakes. In my view, this was a mistake on Macey and Richardson's part.

Macey and Richardson then write: "Notably, Chancellor [James] Kent, in a letter, attributed Story's interpretation to the original text of Federalist 77, an error which was repeated both in nineteenth-century histories of removal and by Chief Justice Taft's law clerk in connection with Taft's decision in Myers [v. United States]." Id. at note 225. Macey and Richardson cite two publications by Professor Robert Post in support of this view, but they do not cite any original, transcript, or reproduction of Kent's letter. This sentence of theirs is a Gordion knot. I have made some effort to cut this knot. Let me start by saying that, as best as I can tell, Kent's letter is from 1830, and Story wrote in 1833. So I suggest there was no way for Kent to attribute or misattribute anything by Story. Macey and Richardson are not entirely at fault. The error is in some substantial part Professor Robert Post's, and the concomitant error, by Macey and Richardson, is their (all too understandable) willingness to rely on Post and their failure to look up Kent's actual letter. Still, for reasons I explain below, Macey and Richardson have done modern scholars a valuable service—for which I thank them. (And, no, this is not sarcasm.)

To summarize: Macey and Richardson rely on Robert Post. Post is quoting Chief Justice Taft's researcher: William Hayden Smith. And William Hayden Smith is quoting Chancellor Kent. We are four levels deep—so, it is hardly surprising that one or more mistakes and misstatements creep into the literature.

Professor Post wrote:

[William Hayden] Smith replied on September 22 [1925] in a letter [to then-Chief Justice Taft] that cited scattered references and concluded that "I have deduced that executive included in its meaning the power of appointment and that sharing it with the legislative was extraordinary." Hayden Smith to WHT (September 22, 1925) (Taft [P]apers). Smith did not find much about the power of removal—the [Supreme Court] library was still looking for W.H. Rogers, The Executive Power of Removal—except that Chancellor Kent had in a letter written that although in 1789 "he [Kent] head leant toward Madison, but now (1830) because of the word 'advice' must have meant more than consent to nomination, he said he had a strong suspicion that Hamilton was right in his remark in Federalist, no. 77, April 4th, 1788: 'No one could fail to perceive the entire safety of the power of removal if it must thus be exercised in conjunction with the senate.' " [bracketed language added] [bold & italics added]

Robert C. Post, X.I The Taft Court / Making Law for a Divide Nation, 1921–1930, at 426–27 n.58 (CUP 2024); Robert Post, Tension in the Unitary Executive: How Taft Constructed the Epochal Opinion of Myers v. United States, 45 J. Sup. Ct. Hist. 167, 173 (2020) (same). The language above is simply too elliptical to clearly understand. "He said he had": Who is the "he" here, and whose voice is this: Kent or Smith on Kent? There is no reliable way to know what language here is Post's, and/or what is Smith's, and/or what is Kent's. Nor is there any good way to tell what here is a quotation and what has been rewritten (and by whom). The one thing which is clear is that Post leaves the reader with the impression that this passage is about removal.

What to do? All we can do is to examine the next level. That is: What did William Hayden Smith write in his letter to Taft?

Here is a link to the Letter from William Hayden Smith to Chief Justice Taft (Sept. 22, 1925). Smith wrote:

In [Senator Daniel] Webster[']s Private Correspondence, vol.1, pp.486-7, there is a letter from Chancellor Kent upon the subject. After remarking that at the time of the debate in 1789, he had leant toward Madison, but now (1830) because of the word "advice" must have meant more than consent to nomination, he said he had a strong suspicion that Hamilton was right in his remark in the Federalist, no.77, April 4th, 1788: "No one could fail to perceive the entire safety of the power of removal if it must thus be exercised in conjunction with the senate." [italics added] [bold and italics added]

There are two problems with the passage above, one internal to the passage, and one external to it, as quoted by Post and others.

First: the minor error. The sentence in bold and italics is from Story's 1833 Commentaries on the Constitution—it is not from Federalist No. 77. And Kent's letter is from 1830—so that sentence is not likely from Kent either (unless Story lifted it from Kent's writings [which I have no good reason to suspect], or Kent was a time traveller [ditto]). The mistake here is Smith's, and Post's quoting Smith without explanation, and those quoting Post without examining the underlying chronological problem.

Second: the major error. The Smith passage above is the penultimate full paragraph of the letter. What has gone unreported is how Smith ends his letter. Smith, on the top of the next (that is, the last) page of his letter, wrote:

Kent went on to say that there was a general principle in jurisprudence that the power that appoints is the power to determine the pleasure and limitation of the appointment. The power to appoint, he said must also include the power to re-appoint, and the power to appoint and reappoint when all else is silent is the power to remove. However, Kent concluded that he would not call the president[]s power in[to] question as "it would hurt our reputation abroad, as we are already becoming accused of the tendency of reducing all executive power to legislative." [italics added] [hyphen added]

This last full paragraph, which has gone unreported in the modern literature, inverts the common understanding of the prior paragraph—a paragraph which has been reported by Post and others. As I understand Kent, he is saying that absent tenure in office, the President and Senate collectively can appoint to vacant positions, and they can also appoint to occupied positions. An appointment of the latter type works a constructive removal. That's the "removal" power under discussion in Federalist No. 77. In terms of a free-standing presidential removal power, Kent acknowledges that one has sprung from practice and by statute, and he chooses not to question the president's use of such a removal power for political reasons. In other words, Kent, like Story, read Federalist No. 77's "displace" language to refer to "replace," and not to "removal" per se or removal simpliciter.

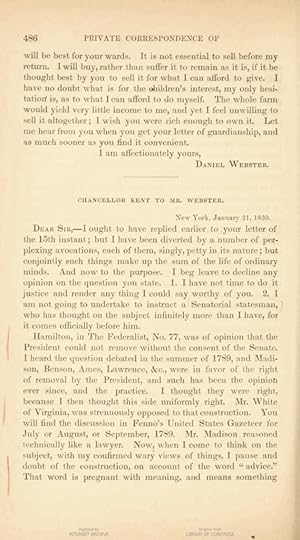

That takes us to Kent's January 21, 1830 letter. You can read it here—at page 486 (just as reported by William Hayden Smith)—courtesy of the HathiTrust website.

Kent stated:

Again, two points here. The troubling statement from Story does not appear in the Kent letter. How could it? And the only removal power under discussion in Federalist No. 77 is the power to appoint and re-appoint, with the latter working a constructive removal. The power of the President to remove (as in a pure removal, absent any successive or subsequent appointment) arose in connection with a purported congressional declaratory act and acquiescence by congress or the public or both. That sort of removal, according to Kent, was not under discussion in Federalist No. 77. At least, that is my reading of these documents.

I thank Professors Macey and Richardson for teeing this issue up. In doing so, they have helped start a process leading to the clarification of a messy historical literature. As for Professor Post—we all make mistakes. Certainly, I am not faulting him. And I am not faulting, in any way, Professor Bailey for adhering to the traditional Hamilton meant removal in Federalist No 77 view during our 2010 debate on the issue. There is certainly evidence on both sides of the issue—that is: What did Hamilton mean by "displace"?

Still, it is troubling—more than slightly troubling—that unlike Professor Bailey, any number of academics and historians have played let's pretend and announced, as if God, that all evidence points conclusively in one direction. Historical and interpretive questions are rarely so simple. Frequently, there is a majority and a minority view, if not more than two such views, and a stronger/better view and a weaker/lesser view. And after hundreds of years, it is difficult for moderns to identify which was or is which. But pretending that there are not competing ideas and ideals undercuts our understanding and our efforts at fair-play, and when all this is done by academics, it teaches students little more than adherence to authority, political correctness, and wokism. If academics cannot be reasonably fair in voicing disagreement, at least they should strive to be cautious—given that their favored theories may be falsified by one heretofore unknown document. Editors at journals and publishing houses who publish such one-sided materials fail to understand one of their key missions—which is to rein in the excess that comes from debate participants, who may have a fair point to make, but who have lost perspective. I know that my publications have frequently benefited from editors who advised me to moderate my language. If editors refuse to do this, than Professor Brian Frye will (and should) have his dream—a world without journals replaced by papers only "published" on the Social Science Research Network. That "is the long and short of it." Jonathan Gienapp, Removal and the Changing Debate over Executive Power at the Founding, 63 Am. J. Legal Hist. 229, 238 n.55 (2023) (peer review); see also Ray Raphael, Constitutional Myths: What We Get Wrong and How to Get It Right 278 n.38 (2013).

The post Chancellor James Kent on Hamilton's Federalist No. 77 and Modern Academic Commentary appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] No Restraining Order Blocking High School Turning Point USA Event, "Two Genders: One Truth"

From Doe v. Albemarle County School Bd., decided yesterday by Judge Jasmine Yoon (W.D. Va.):

This matter is before the court on Plaintiff J. Doe's motion for a temporary restraining order, and motion for a preliminary injunction, both filed on November 17, 2025. Doe requests that the court prohibit Defendant Albemarle County School Board ("the School Board") from allowing the Western Albemarle High School's Turning Point USA club ("TPUSA club") to host Victoria Cobb as a guest speaker for an event titled "Two Genders: One Truth." The event is scheduled for November 19, 2025, at 12:00 p.m. The court held a hearing on the motion for a temporary restraining order on November 18, 2025. The court finds that Doe has not made a clear showing that they are likely to succeed on the merits of the "deliberate indifference" element of the Title IX claim. Accordingly, the court will deny Doe's motions for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction….

While the court recognizes and sympathizes with Doe and their anxiety and distress surrounding the event, … Doe is not able to make a "clear showing that [they are] likely to succeed at trial" on their Title IX claim. A Title IX claim premised on sexual harassment, as here, requires the plaintiff to prove that: "(1) the educational institution receives federal funds; (2) the plaintiff was subjected to harassment based on her sex; (3) the harassment was sufficiently severe or pervasive to create a hostile (or abusive) environment in an educational program or activity; and (4) there is a basis for imputing liability to the institution."

Under the fourth prong, liability may only be imputed to the institution in cases of deliberate indifference. Specifically, the Supreme Court has held that an institution may be liable for third-party harassment "only where [its] response to the harassment or lack thereof is clearly unreasonable in light of the known circumstances." Davis v. Monroe Cnty. Bd. of Educ. (1999). The Davis standard "sets the bar high for deliberate indifference."

Specifically, the Davis Court held that "it would be entirely reasonable for a school to refrain from a form of disciplinary action that would expose it to constitutional or statutory claims." Here, the School Board was exposed to both statutory and constitutional claims after Principal Jennifer Sublette announced her decision to move the original event from lunch to evening. The demand letter—sent from Michael B. Sylvester on behalf of the TPUSA club, sponsoring teacher, and Cobb—delineated these potential claims, which included First Amendment viewpoint discrimination and federal Equal Access Act violations. The letter asked the Board to correct the "unlawful act" "immediately."

While a demand letter with frivolous or empty claims would not suffice to show the School Board's exposure to liability, the First Amendment and Equal Access Act claims raised in this demand letter involve nuanced and sometimes unsettled questions of law. First Amendment protections for school settings established in cases like Tinker v. Des Moines Indep. Cmty. Sch. Dist. (1969) … as well as the prohibition on viewpoint discrimination expounded in cases like Good News Club v. Milford Cent. Sch. (2001), cast doubt on Doe's assertion that permitting the event to proceed was clearly unreasonable….

Although the court does not rule on the merits of any First Amendment or Equal Access Act issues, it recognizes that the School Board weighed the issues arising from this complex area of law while facing potential legal claims from a range of entities. The continued debate among School Board leadership, advocacy groups, and members of the public in the weeks before and after the October 9 board meeting further underscores the thorniness and obscurity of applying federal law to this dispute. Accordingly, the court finds the Board's response based on their understanding of the law was not "clearly unreasonable."

The School Board also promptly responded to the complaints and community backlash it received. Within about a week of its decision to reinstate the lunchtime event, the Board issued a Community Message recognizing "that these discussions have left many feeling angry, frustrated, or invalidated," and affirming that "[the Board's] policies require us to ensure students' constitutional rights to assemble and hear diverse perspectives, just as we expect respectful conduct and nondiscrimination in all schools." … [T]he School Board also consulted its legal counsel and laid out parameters for the event to ensure that it could proceed behind closed doors without disrupting the school or violating any laws….

The post No Restraining Order Blocking High School Turning Point USA Event, "Two Genders: One Truth" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] No Pseudonymity in #TheyLied Defamation Case Over Sexual Assault Allegations

From Doe v. Doe, decided today by Judge F. Kay Behm (E.D. Mich.):

Plaintiff [John Doe] and Defendant [Jane Doe] are half-siblings and have known each other for over forty years. Plaintiff owns a law firm that operates nationwide, with a primary business address in Oakland County, Michigan. The relationship between Plaintiff and Defendant deteriorated when Defendant allegedly failed to perform on a contract to work for Plaintiff, and defaulted on a personal loan. A few days after Plaintiff terminated the contract for Defendant to work for Plaintiff, Defendant called Plaintiff's former spouse and told her that 30 years ago Plaintiff got Defendant drunk and sexually assaulted her. Plaintiff says this statement by Defendant is false and defamatory….

Generally, there is a presumption of open judicial proceedings in the federal courts; proceeding pseudonymously is the exception rather than the rule. Rule 10 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure requires that the complaint state the names of all parties. In order to circumvent this requirement, it must be shown that the need for anonymity substantially outweighs the presumption that parties' identities are public information and the risk of unfairness to the opposing parties….

[Plaintiff argues that] "[c]ourts generally allow a plaintiff to litigate under a pseudonym in cases containing allegations of sexual assault because they concern highly sensitive and personal subjects." And because Defendant is his half-sibling, the disclosure of either party would lead to the inevitable disclosure of the other.

The court is cognizant that the accusation of sexual misconduct can itself invite harassment and ridicule. But the public has an interest in the openness of judicial proceedings; "if courts were to allow mutual pseudonymity in sexual assault-related libel or slander suits, then 'whole areas of the law could become difficult for the media and the public to monitor, outside the constrained accounts of the facts offered up by judges and lawyers.'" Although Plaintiff credibly asserts that disclosure of the parties' names may mean that internet search results will associate them with this lawsuit and its potentially sensitive facts, that is not a factor unique to this particular Plaintiff justifying a departure from Rule 10.

Other than the implied, and speculative, reputational damage to his law firm, Plaintiff does not assert a specific, individualized claim of potential retaliation or harassment. See Doe v. Megless (3d Cir. 2011) ("That a plaintiff may suffer embarrassment or economic harm is not enough."). The court finds it telling that Plaintiff failed to cite a single case in which a plaintiff in a defamation or libel action was allowed to proceed pseudonymously against an alleged victim of sexual assault. See Roe v. Doe 1-11 (E.D.N.Y. 2020) ("The Court finds it highly persuasive that Plaintiff fails to and is unable to cite a single case in which a plaintiff, suing for defamation and alleging he was falsely accused of sexual assault, was allowed to proceed anonymously against the victim of the purported assault."); DL v. JS (W.D. 2023)….

Seems correct to me; for more on this, see this post.

The post No Pseudonymity in #TheyLied Defamation Case Over Sexual Assault Allegations appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Any 2024-25 Journal Articles on Law and Religion That You Particularly Liked?

If so, consider nominating them for this award, by Dec. 15; note that the award is limited to relatively junior faculty members:

The AALS Section on Law and Religion seeks nominations for the 2025 Harold Berman Award for Excellence in Scholarship. This annual award recognizes a paper that has made an outstanding scholarly contribution to the field of law and religion. To be eligible, a paper must have been published between July 15, 2024, and November 15, 2025. The author must be a faculty member at an AALS Member School (with no more than 10 years' experience as a faculty member) or a full-time fellow or VAP at an AALS member school. Nominations should include the name of the author, the title of the paper, a statement of eligibility, and a brief rationale for choosing the paper for the award. Self-nominations are accepted. Nominations should be sent to Rick Garnett (rgarnett@nd.edu), Chair of the Berman Prize Committee, by December 15, 2025.

The post Any 2024-25 Journal Articles on Law and Religion That You Particularly Liked? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "Inside the Markets Aggregating Political Reality"

Stanford Political Science Prof. Andy Hall, a colleague of mine at Hoover, has this very interesting post at his new Free Systems Substack. An excerpt:

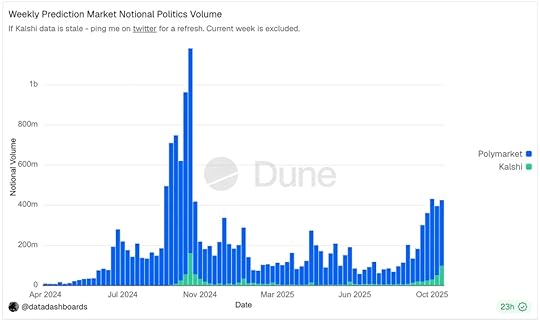

I've studied political prediction markets for years, and their early history is full of clever designs and unrealized promise. But what's happening now is fundamentally different. The scale, the liquidity, and the attention these markets are attracting represent a break from efforts of the past.

My broader project is to understand how we preserve liberty in an increasingly algorithmic world. Prediction markets are a fascinating case where individuals, freely pursuing their own incentives and acting on their own information, can generate a public good for the digital era: a clearer shared picture of a highly complex political environment. At the same time, they can also create strange feedback loops that require careful governance. So they're well worth studying.

To learn more, I decided to see them up close. Two weeks ago, I flew to New York City for election night and joined a group of academics, technologists, and prediction-market traders to run a real-time experiment betting on actual elections.

Over the course of the night, I witnessed a technology that has incredible potential to make us smarter and more informed about politics and the world—and which raises profound questions about what politics looks like in a world of live probability feeds where truth is often contested and frictionless information overwhelms our narrow attention spans….

Three questions that will make or break prediction markets for politics

Question 1: When markets become narrative, how do we think about manipulation and unintended consequences? …

Question 2: When we have markets for everything, how do we find the right ones at the right time and make sure they resolve correctly? …

Question 3: When markets are a source of truth, how do we define truth for the most contentious issues? …

Back home after my experiment in New York, I've developed a new habit. When I watch NFL games, I have the Kalshi and Polymarket prices open on the computer next to me. When I see them spike, I know to pay attention to the game in anticipation of a big play, because the markets move several seconds before my TV feed does. Traders are literally outrunning my "live" TV. The growth and speed of these prediction markets is truly extraordinary.

Real-time prices from political prediction markets can cut through noise, quantify uncertainty, and help us see the world more clearly, if they are designed with care. That means solving at least three linked governance challenges that I've explored here: manipulation, discovery, and resolution. There are good reasons to be optimistic about all of them, but they all require careful thought and learning from mistakes as we go. I'll be sharing more in-depth ideas on each in the coming months.

Read the whole thing; if you find it interesting, you can subscribe to the Substack here.

The post "Inside the Markets Aggregating Political Reality" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Democratic National Committee Not Liable for Field Organizer's Alleged "Grooming" of 16-Year-Old Campaign Volunteer, Which Led to Sex

From yesterday's decision by Judge Gerald Pappert (E.D. Pa.) in D.F. v. DNC Servs. Corp.:

D.F. was a [16-year-old] high school student in the summer of 2012 when she volunteered with Organizing for America, an arm of the Democratic National Committee, to work on the presidential campaign.

Killackey, a 38-year-old field organizer in the office, "allegedly 'groomed' D.F., leading to a sexual relationship between the two, which D.F. contends was unwanted and abusive":

He allegedly "took an immediate and unusual interest" in D.F. and openly flirted with her, referred to her as "precocious," and gave her gifts. D.F. alleges that Killackey was "groom[ing]" her "for sexual exploitation and abuse."

In June of 2012, D.F. asked staff at the Bristol office for a ride home from work, and Killackey agreed to give her one. D.F. alleges that Killackey flirted with her in his car and that she told him "she may have a crush on him." Killackey allegedly pulled the car over and, without D.F.'s consent, touched and spoke to her in a sexual manner. D.F. alleges that later that summer, Killackey "brought [her] to his apartment" and "proceeded to initiate sexual intercourse," after which a "sexually abusive relationship" continued throughout the summer and into the school year. The alleged sexual abuse happened in Killackey's car, at his apartment or in public parks. D.F. did not reveal the relationship or the abuse to the DNC or to any staff in the Bristol office.

D.F. sued the DNC for, among other things, negligent supervision, but the court threw that claim out:

[A] claim for negligent supervision must allege that an employer "knew or should have known of a need to supervise the employee, and that, by failing to do so, exposed the plaintiff to the employee's misbehavior." … To state such a claim, D.F. must allege facts sufficient to satisfy two separate inquiries. First, that Killackey harmed her on DNC premises or on premises to which Killackey gained access via his employment, and second, that the DNC could have foreseen the need to control Killackey and that the harm he allegedly caused was reasonably foreseeable….

None of Killackey's alleged misconduct took place at the Bristol Campaign office. D.F. claims Killackey exhibited unprofessional conduct on DNC's premises: he flirted with her, sang a suggestive song about her, called her "precocious," gave her gifts, and made business calls that D.F. joined from his office with the door closed. D.F. also alleges that she and Killackey "openly held each other" and "behave[ed] like boyfriend and girlfriend" at a post-election celebration in Washington, D.C. But D.F. claims the alleged sexual conduct—the abuse—took place in Killackey's apartment, his car or in public parks. The DNC does not have a duty to supervise its employees at their homes, in their cars or in public parks.

D.F. characterizes Killackey's conduct on DNC's premises as "grooming," but none of his alleged on-premises actions were tortious. To state a claim for negligent supervision, D.F. must allege that Killackey committed an intentional tort on DNC's premises or on premises to which he was privileged to access via his employment. She does not….

I doubt that all courts would require, as a condition of negligent supervision claims, that the intentional tort was committed on the employer's "premises or on premises to which he was privileged to access via his employment"; some would allow liability so long as the intentional tort was made possible by behavior within the employment relationship (and there is other evidence of negligent supervision). But Pennsylvania law does appear to impose such an intentional-tort-on-the-premises requirement.

In addition to the premises requirement, negligent supervision claims must satisfy two foreseeability requirements. First, the employer may be liable if "it knew or should have known the necessity" for controlling their employee based on "dangerous propensities that might cause harm to a third party." Second, the harm that the "improperly supervised employee caused" must be reasonably foreseeable. Here, the foreseeability inquiry focuses on Killackey's alleged unwanted sexual acts which are the source of D.F.'s alleged harm.

The DNC could not, based on the amended complaint's allegations, have known Killackey had a propensity to commit sexual abuse…. D.F. concedes that no one with the DNC had actual knowledge of Killackey's propensity to commit harm. She alleges that she told no one with the DNC about the nature of their relationship, and that the DNC never discovered it. D.F. claims only the DNC should have known Killackey had a propensity to sexually abuse her because DNC staff was aware that:

Killackey was flirtatious with D.F. and called her "precocious";Killackey agreed to give D.F. a ride home;D.F. and Killackey went canvassing together;Killackey gave D.F. a book and other unidentified gifts;Killackey exchanged text messages with D.F. on his personal phone;Killackey sang a suggestive song from a movie after D.F. made a reference to the film;D.F. and Killackey sat in his office with the door closed while he made calls;D.F. joined DNC staff to watch election results at a bar, where she and Killackey sat next to each other;At an inaugural ball in Washington, DC, the two "held each other" and "openly behav[ed] like boyfriend and girlfriend." …The prior conduct need not be an exact match for the tortious conduct, but the employee "must have committed prior acts of the same general nature as the one for which the plaintiff brings suit—acts that show the employee is 'vicious or dangerous and … intended to inflict injury upon others.'" While D.F.'s allegations could allow the inference that DNC staff witnessed unprofessional conduct in the workplace, they do not establish that the staff should have foreseen Killackey might sexually abuse her outside the workplace. And the harm Killackey allegedly caused was not reasonably foreseeable for the same reasons the DNC could not have known of Killackey's propensity to commit sexual abuse. "A harm is foreseeable if it is part of a general type of injury that has a reasonable likelihood of occurring." D.F. has not alleged facts to plausibly establish that the harm—Killackey's alleged sexual abuse—was reasonably foreseeable….

The claim of negligent failure to report child abuse fails for the same reason: D.F. insufficiently alleges the DNC had reason to suspect Killackey's alleged abuse…. [A]t most, D.F. alleges DNC staff were aware of Killackey's unprofessional conduct—not that they were aware of the alleged abuse, which took place away from the workplace and which D.F. never mentioned or alluded to….

The plaintiff's conspiracy and aiding and abetting claims were also thrown out, since to show that one needs to show even more than negligence—agreement "to perform an unlawful act" for conspiracy, and "'actual knowledge' of the tort, which knowledge may be inferred by 'willful blindness'" for aiding and abetting. And plaintiff's vicarious liability claim were thrown out as well:

An employer may be vicariously liable for its employees' tortious acts committed during the scope of their employment. But if "an assault is committed for personal reasons or in an outrageous manner, it … is not done within the scope of employment." Pennsylvania courts "have consistently held that sexual abuse of minors falls outside an employee's scope of employment." D.F. fails to allege that Killackey's conduct was "actuated by any purpose of serving" his employer and she therefore fails to state a claim for the DNC's vicarious liability….

The assault, battery, and intentional infliction of emotional distress claims against Killackey are pending. Note that the general age of consent for sex in Pennsylvania is 16, but plaintiff alleges that much of the behavior was actually nonconsensual.

The post Democratic National Committee Not Liable for Field Organizer's Alleged "Grooming" of 16-Year-Old Campaign Volunteer, Which Led to Sex appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: November 19, 1969

11/19/1969: Walz v. Tax Commission of City of New York argued.

The post Today in Supreme Court History: November 19, 1969 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Open Thread

[What’s on your mind?]

The post Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers