Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 14

October 15, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] Let's Go Brandon!—to the Principal's Office

From Sixth Circuit Judge John Nalbandian, joined by Judge Karen Nelson Moore, in yesterday's B.A. v. Tri County Area Schools:

Two middle schoolers in Michigan wore sweatshirts emblazoned with the phrase "Let's Go Brandon" to school. Based on the commonly understood meaning of the slogan, the school administrators determined that the sweatshirts were inappropriate for the school environment. They asked the students to remove the sweatshirts, and fearing punishment, the students complied. But they still wanted to wear the sweatshirts at school to express their disapproval of then-President Joe Biden's administration and its policies. So, through their mother, the students sued the school district and several school administrators, alleging that the school deprived them of their First Amendment rights. The district court sided with the school district, concluding that the school could reasonably prohibit the sweatshirts since they were vulgar speech. Because the school reasonably understood the slogan "Let's Go Brandon" to be vulgar, we affirm….

[S]tudents do not "shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate." Tinker v. Des Moines Indep. Cmty. Sch. Dist. (1969). But those retained rights "are not automatically coextensive with the rights of adults in other settings." Bethel Sch. Dist. No. 403 v. Fraser (1986). Under Tinker, schools can generally forbid or punish student speech that causes a "substantial disruption of or material interference with school activities." But the Supreme Court has recognized several exceptions to Tinker's standard. On school grounds, a school may generally prohibit (1) indecent, lewd, and vulgar speech [as in Fraser]; (2) speech that promotes illegal drug use; and (3) speech that others may reasonably perceive as bearing the imprimatur of the school. Without one of these exceptions, the Tinker standard applies and the school has the burden of showing that it reasonably believes its regulation of student speech will prevent substantial and material interference with school functions.

This case is about the vulgarity exception. And specifically, how a school may regulate political speech without vulgar words that the school nonetheless reasonably understands as having a vulgar message. To answer that, we must resolve two preliminary questions. The first is linguistic, asking whether a phrase that lacks explicitly profane words might still have a vulgar meaning. The second is doctrinal, asking whether a school administrator may prohibit student political speech that has a vulgar message. The district court answered yes to both and so held that the plaintiffs hadn't suffered any constitutional deprivation because the school administrators' actions comported with the First Amendment. For the reasons given below, we agree….

The question of what is vulgar or profane can depend on the individual. To paraphrase the late George Carlin, everybody has a list of words that they consider profane—but the contents of that list vary greatly from person to person. In answering whether a jacket emblazoned with the words "Fuck the Draft" deserved constitutional protection, the Supreme Court noted that it's "often true that one man's vulgarity is another's lyric." So this high degree of subjectivity means that what is profane often hinges on who decides. And in related contexts, the Supreme Court has said that the question of who decides should be evaluated in a manner "consistent with our oft-expressed view that the education of the Nation's youth is primarily the responsibility of parents, teachers, and state and local officials, and not of federal judges."

The Constitution doesn't hamstring school administrators when they are trying to limit profanity and vulgarity in the classroom during school hours. Again, students do not "shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate." But neither are school administrators powerless to prevent student speech that the administrators reasonably understand to be profane or vulgar. And so "the First Amendment gives a … student the classroom right to wear Tinker's armband, but not Cohen's jacket." Schools are charged with teaching students the "fundamental values necessary to the maintenance of a democratic political system." And avoiding "vulgar and offensive terms in public discourse" is one such value. After all, "[e]ven the most heated political discourse in a democratic society requires consideration for the personal sensibilities of the other participants and audiences." …

[A] euphemism is not the same as the explicitly vulgar or profane word it replaces. "Heck" is not literally the same word as "Hell." But the word's communicative content is the same even if the speaker takes some steps to obscure the offensive word. The plaintiffs concede that a school could prohibit students from saying "Fuck Joe Biden" because "[k]ids can't say 'fuck' at school." And yet they insist that the euphemism "Let's Go Brandon" is distinct—even though many people understand that slogan to mean "Fuck Joe Biden." So it's not clear that the school administrators acted unreasonably in determining that the euphemism still conveyed that vulgar message.

After all, Fraser—the first case that recognized the vulgarity exception—involved a school assembly speech that had a rather elaborate sexual metaphor instead of explicitly vulgar or obscene words. And yet the Supreme Court had no reservation in holding that the school was not required to tolerate "lewd, indecent, or offensive speech and conduct." And it was up to the school to determine "what manner of speech in the classroom or in school assembly is inappropriate." Because "[t]he pervasive sexual innuendo in Fraser's speech was plainly offensive to both teachers and students—indeed to any mature person," the school could discipline his speech despite the absence of explicitly obscene or vulgar words. And so Fraser demonstrates that a school may regulate speech that conveys an obscene or vulgar message even when the words used are not themselves obscene or vulgar.

This conclusion fits with our circuit precedent, which reads Fraser to leave it to the school to decide what is vulgar or profane so long as the decision is not unreasonable….

[And] while the Court in Fraser did distinguish "between the political 'message' of the armbands in Tinker and the sexual content of [Fraser's] speech," that doesn't mean that it discounted the political nature of that speech [which was a speech urging the election of a classmate to student government office]. Indeed, much of the Court's opinion is spent explaining why the speech's vulgarity allowed the school to punish Fraser despite the protections for student political speech. The Court's reference to "Cohen's jacket," shows that when student speech is both vulgar and political, the school's interest in prohibiting vulgarity predominates over the student's interest in making a political statement in the language of their choosing….

Judge John Bush dissented:

[T]he speech here—"Let's Go Brandon!"—is neither vulgar nor profane on its face, and therefore does not fall into [the Fraser] exception. To the contrary, the phrase is purely political speech. It criticizes a political official—the type of expression that sits "at the core of what the First Amendment is designed to protect." No doubt, its euphemistic meaning was offensive to some, particularly those who supported President Biden. But offensive political speech is allowed in school, so long as it does not cause disruption under Tinker. As explained below, Tinker is the standard our circuit applied to cases involving Confederate flag T-shirts and a hat depicting an AR-15 rifle—depictions arguably more offensive than "Let's Go Brandon!" …

The majority says the sweatshirts' slogan is crude. But neither the phrase itself nor any word in it has ever been bleeped on television, radio, or other media. Not one of the "seven words you can never say on television" appears in it .Instead, the phrase has been used to advance political arguments, primarily in opposition to President Biden's policies and secondarily to complain about the way liberal-biased media treats conservatives. It serves as a coded critique—a sarcastic catchphrase meant to express frustration, resentment, and discontent with political opponents. The phrase has been used by members of Congress during debate. And even President Biden himself, attempting to deflect criticism, "agreed" with the phrase.

We cannot lose sight of a key fact: the students' sweatshirts do not say "F*ck Joe Biden." Instead, they bear a sanitized phrase made famous by sports reporter Kelli Stavast while interviewing NASCAR race winner Brandon Brown at the Talladega Superspeedway. The reporter said the crowd behind them was yelling "Let's go, Brandon!" She did not report the vulgar phrase that was actually being chanted. The Majority even concedes Stavast may have used the sanitized phrase to "put a fig leaf over the chant's vulgarity." That is telling….

Annabel F. Shea (Giarmarco, Mullins & Horton, P.C.) represents the school defendants.

The post Let's Go Brandon!—to the Principal's Office appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Boerne, RFRA, and the VRA

[Several justices seem ready to import the congruence and proportionality test to the 15th Amendment.]

I just finished listening to the oral argument in Callais. There are almost certainly six votes to rule in favor of Louisiana here. Justice Kavanaugh came to the argument extremely well-prepared, and seems to have mapped out all of the contours of an opinion. It seemed like he was reading from notes, and articulating different standards that could apply. He quibbled a bit with the Deputy SG's phrasing, but I think he is generally comfortable with the government's framing of the case. Chief Justice Roberts was quiet, and (as best as I can recall) only asked whether certain issues were raised in the Alabama litigation a few year ago. The Chief should assign the majority to Justice Kavanaugh, but will probably keep it himself. Justice Barrett was also working out some of the finer nuanced doctrines of the Enforcement Power analysis. She will probably write a concurrence along those lines.

There is much to discuss, but here I want to focus on a broader question of constitutional law.

Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment gives Congress the power to enact "appropriate legislation" to enforce the rest of the Fourteenth Amendment. City of Boerne v. Flores Court held that there are limits to Congress's power to remedy a violation of Section 1 (such as the Due Process or Equal Protection Clauses). Specifically, the remedy must be "congruent and proportional" to the constitutional violation.

The Supreme Court has never addressed whether the "congruence and proportionality" test also applies to Section 2 of the Fifteenth Amendment. I wrote about this way back in 2013 after Shelby County.

Today, several justices seemed to suggest that the Boerne test would limit Congress's powers under the Fifteenth Amendment. At one point, Justice Barrett asked counsel for petitioners to "assume" the Boerne test applied to the Fifteenth Amendment. In past cases, when Justice Barrett asks lawyers to assume something, that almost certainly means that is her position. Indeed, given Justice Barrett's unwillingness to reverse Smith, I think she will have to go all-in on Boerne.

If the Court does adopt the Boerne test, then the VRA inquiry changes. It is not disputed that the Fifteenth Amendment, like the Fourteenth Amendment, prohibits intentional discrimination. But Section 2 of the VRA (not to be confused with Section 2 of the Fifteenth Amendment) is an "effects" based test, that does not require any showing of intentionality.

Perhaps at some point in the past, Section 2 was a "congruent and proportional" response to the state of voting rights in the United States. Maybe that was even true when Gingles v. Thornburg was decided in 1986. But times have changed. Is there still a "congruence and proportionality" in 2025? I think it is worth noting that Gingles was decided a decade before Boerne. Then again, Boerne contrasted RFRA with the VRA, which had been upheld in Katzenbach.

The application of Borne to the VRA may give the Court a hook to "sunset" that provision, and rule that forcing the states to consider race when drawing maps may no longer be appropriate. Grutter gave the use of race a 25-year sunset clock. Gingles has had an even longer run.

Justice Barrett suggested that Gingles does not need to be "modified" but instead might be "clarified." The Court did just that with another Burger Court precedent. In Groff v. DeJoy (2023), the Court completely rewrote how TWA v. Hardison had been interpreted on the ground for five decades. And that was done to save the precedent from being overruled. Gingles may meet a similar fate. And yet another Burger Court precedent will bite the dust. (In fairness to co-blogger Paul Cassell, CJ Burger only concurred in the judgment in Gingles, which was decided during his final week on the Court.)

The post Boerne, RFRA, and the VRA appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] The Championship Round of the Harlan Institute Competition Will Be Held In The Rotunda of The National Archives

[High School students will moot whether the United Colonies should declare independence from Great Britain.]

Last this week, I announced that the topic of the 14th Annual Harlan Institute Virtual Supreme Court Competition will focus on America's 250th Anniversary. The question presented is whether the United Colonies declare independence from Great Britain.

With something of a tease, I wrote that the championship round will be held before a panel of judges in a "special place."

I can now (almost certainly) confirm that the championship round will be held in the Rotunda Gallery of the National Archives, in the presence of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. I will have much more details in due course.

Teams can register to compete now.

The post The Championship Round of the Harlan Institute Competition Will Be Held In The Rotunda of The National Archives appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "Viewpoint Diversity" Requirements as a New Fairness Doctrine: Viewpoint Discrimination in Application

I have an article titled "Viewpoint Diversity" Requirements as a New Fairness Doctrine forthcoming in several months in the George Mason Law Review, and I wanted to serialize a draft of it here. There is still time to edit it, so I'd love to hear people's feedback. The material below omits the footnotes (except a few that I've moved into text, marked with {}s, as I normally do when I move text within quotes); if you want to see the footnotes—or read the whole draft at once—you can read this PDF. You can see my argument about why viewpoint diversity requirements are likely to chill controversial faculty speech here; here is a follow-up section on why such requirements are likely to be viewpoint discriminatory in application.

[VI.] Viewpoint Discrimination in Application

Beyond the viewpoint-based chilling effects, viewpoint diversity mandates are also likely to be viewpoint-based in application: They are likely to be enforced in ways that require universities to add more representation of viewpoints that are seen as "mainstream" or "legitimate"—or that match the viewpoint of the funding presidential administration—rather than viewpoints that are controversial and unpopular.

Viewpoint diversity mandates obviously can't be used to promote all viewpoints (just as the Fairness Doctrine couldn't be used to give airtime to all viewpoints). Nor can one just say that they need to promote "both" viewpoints: Very few matters are entirely either-or, with only two views on the issue.

The question is rarely something like "should we have immigration or shouldn't we?" Rather, some might argue for no immigration, some for very little, some for a lot, and some for unlimited immigration. Within the "very little" or "a lot" options, some might want to see a preference for more educated or richer immigrants, while others might disagree. Some might want more immigrants from certain countries, while others might want more immigrants from other countries, and still others might want to have no country preferences at all. Some might want to allow immigrants but make them easy to deport; others might want to make deportation extremely difficult. Some might want a quick path to citizenship, and others a slow one, or even no path at all.

There are far too many possible viewpoints on most subjects to ensure that all will be represented. After all, a typical law school or public policy school (if that's where immigration experts are hired) might have only a few positions for people who specialize in immigration. Whoever enforces the mandate must choose which viewpoints are to be included.

In the process, the enforcers will have to make many decisions. There is the old joke that a university department has people with a wide range of opinions—from Bernie Sanders all the way to Joe Biden. Presumably that wouldn't count as sufficient viewpoint diversity if a viewpoint diversity mandate has any meaning.

Likewise, presumably a department's hiring people who only support unlimited immigration, nearly unlimited immigration, and very broad immigration wouldn't be seen as providing "viewpoint diversity" on that particular topic. Likewise, given that viewpoint diversity is likely to be evaluated at the department level rather than just at the level of one particular topical area (such as immigration policy), a department hiring people who have Marxist views, critical race theory views, and liberal views wouldn't count as "viewpoint diversity," even if the faculty in each camp think the others' viewpoints are wildly mistaken.

Conversely, say a department that has two faculty members who study immigration policy, one of whom takes a loosely mainstream Democratic Party view on the subject and one who takes a loosely mainstream Republican Party view. The department likely wouldn't be faulted as lacking "viewpoint diversity" on the grounds that no faculty take views that are seen as extreme within the context of modern American political debate (e.g., people who support completely open borders or who support total closing of all immigration and deportation of all noncitizens, including those who are legally present).

Presumably "viewpoint diversity" would, in practice, have to mean some meaningful representation of "conservative" or "right-wing" views as well as "liberal" or "left-wing" views. But this means that government officials will have to repeatedly make ideologically laden decisions about just where on the spectrum a particular view falls.

And those decisions often can't be made in any objective, truly neutral way. Say, for instance, that one of the most prominently visible law school faculty members prominently advocates very broad free speech protections. Should that be counted as a "right-wing" position or a "left-wing" one? Or say that another faculty member is known for arguing that religious objectors shouldn't be entitled to exemptions from generally applicable laws under the Free Exercise Clause. Today, that is a "liberal" view, associated with Justices Kagan, Sotomayor, and Jackson. But when the faculty member was hired, that may well have been a "conservative" view, associated with Justice Scalia and Chief Justice Rehnquist.

Or consider methodological divides. Law and economics, for instance, was historically seen as a "conservative" position, but of course many scholars use law-and-economics tools to reach liberal results. The same is true of originalism. How would a liberal originalist be counted for viewpoint diversity purposes?

More broadly, say a department has several prominent faculty members:

One is known for scholarship, teaching, and public commentary arguing for legalizing all drugs.Another is known for supporting essentially unlimited immigration.Another is known for wanting to sharply limit police power.Another was prominent in the movement to legalize same-sex marriage.Another consistently argues for free markets.Another argues for gun rights and opposes nearly all gun control measures.Another strongly supports private property rights.Another backs school choice programs.Is this a suitably viewpoint diverse department, because it has some faculty who endorse left-wing positions 1 to 4 (some perhaps seen as highly left-wing) and others who endorse right-wing positions 5 to 8? Would the answer change if, when asked, all eight faculty members say they are committed libertarians (and would even agree with each other on all those views, because they are part of the libertarian agenda)? Or would the department only be sufficiently viewpoint-diverse if it also had opponents of drug legalization, immigration, free markets, and gun rights? If so, how would that work given the limited number of faculty members that the department may be able to employ?

But beyond just the question of how particular viewpoints are categorized—which would itself be influenced by the ideological positions of the government officials who are doing the categorizing—presumably some viewpoints will be seen as so illegitimate or unfounded that the government won't require them to be included under the "diversity" rubric. Say that someone objects that some department entirely lacks avowed racists, or outright Communists, or advocates of political violence or of eliminating the age of consent for sex.

As a practical political matter, this lack probably wouldn't be seen as inconsistent with a viewpoint diversity mandate. Yet lack of representation for more mainstream viewpoints presumably would be seen as inconsistent with such a mandate (that's the point of the mandate). The federally imposed viewpoint diversity mandates would thus promote certain viewpoints—including viewpoints about inherently contestable value judgments, and not just about factual questions that might reasonably be viewed as settled—and not others.

Nor can this government preference for certain viewpoints over others be avoided by requiring proportional representation, or a department that "looks like America" in an ideological sense. One quarter of the population strongly or somewhat agrees with the view that "Jews are more willing than others to use shady practices to get what they want." One-eighth strongly or somewhat agrees with the view that "The use of force is justified to ensure members of Congress and other government officials do the right thing." Six percent of the population continues to condemn interracial marriage. Does it follow that law schools or political science departments will have to hire accordingly?

Likewise, consider medical schools or science or history departments. Presumably a viewpoint diversity requirement for medical school hiring might call for some diversity of views on topics that are genuinely controversial among serious scholars, such as youth gender medicine or the propriety of vaccinating young children against COVID. {Both these topics are ones on which the medical establishments of advanced Western democracies have split, which suggests that there is genuine and reasonable debate on the subject.} But if the medical school is entirely homogeneous on questions such as the germ theory of disease, the general utility of vaccines, or the superiority of modern medicine over faith healing, that presumably wouldn't be a reason to strip it of funds for lacking viewpoint diversity.

Nor is this limited to homogeneity on empirical questions; a "viewpoint diversity" requirement would likely be enforced in ways that tolerate homogeneity as to certain normative questions as well. For instance, a history department that entirely consists of Marxists or of pro-colonialists would presumably be faulted for lacking viewpoint diversity. But even if every member of the department rejects the normative views that Stalin was a great humanitarian or that the world would be a better place with more anti-Semitism, we would understandably think that there's no problem with those viewpoints being unrepresented.

Thus, in implementation, a viewpoint diversity requirement couldn't be viewpoint-neutral: It would necessarily end up protecting some viewpoints from being omitted or neglected, but it wouldn't protect other viewpoints. To be sure, some might defend such a requirement despite the inevitable viewpoint discrimination in its application. My argument here is simply that such viewpoint discrimination is inevitable.

And this too is one of the reasons the Fairness Doctrine was rejected:

[T]he enforcement of the doctrine requires the "minute and subjective scrutiny of program content," which perilously treads upon the editorial prerogatives of broadcast journalists…. [I]n administering the doctrine [the Commission] is forced to undertake the dangerous task of evaluating particular viewpoints….

[U]nder the fairness doctrine, a broadcaster is only required to air "major viewpoints and shades of opinion" to fulfill its balanced programming obligation …. [T]he Commission is [therefore] obliged to differentiate between "significant" viewpoints which warrant presentation to fulfill the balanced programming obligation and those viewpoints that are not deemed "major" and thus need not be presented. The doctrine forces the government to make subjective and vague value judgments about various opinions on controversial issues to determine whether a licensee has complied with its regulatory obligations. …

The doctrine requires the government to second-guess broadcasters' judgment on such sensitive and subjective matters as the "controversiality" and "public importance" of a particular issue, whether a particular viewpoint is "major," and the "balance" of a particular presentation.

Here too, the FCC's analysis applies to viewpoint diversity requirements as much as to the Fairness Doctrine, simply by changing "broadcaster" to "university department" and adapting a few other words accordingly.

The post "Viewpoint Diversity" Requirements as a New Fairness Doctrine: Viewpoint Discrimination in Application appeared first on Reason.com.

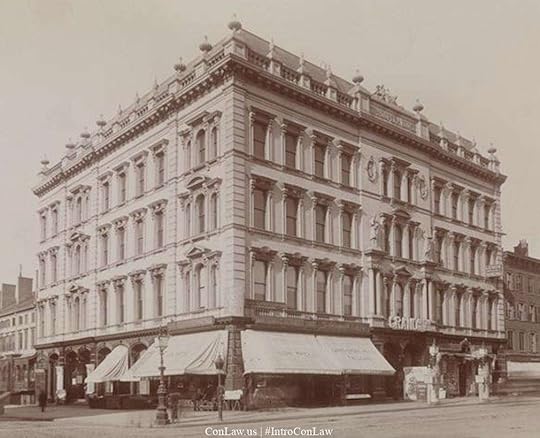

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: October 15, 1883

10/15/1883: The Civil Rights Cases are decided.

The Grand Opera House in New York denied "another person, whose color is not stated, the full enjoyment of the accommodations."

The Grand Opera House in New York denied "another person, whose color is not stated, the full enjoyment of the accommodations."The post Today in Supreme Court History: October 15, 1883 appeared first on Reason.com.

October 14, 2025

[Josh Blackman] DOJ Argues That Agency Head Cannot Delegate Power To Appoint Inferior Officers

[In 2005, the Office of Legal Counsel said this issue was unsettled. But a brief in the Alina Habba litigation takes a firm position.]

The Constitution allows Congress to vest the appointment power of inferior officers in the heads of departments. Can the department head then delegate that power to someone else in the department?

In 2005, the Office of Legal Counsel stated that the issue was unsettled:

Third, you have asked whether the prohibition in the draft order that prevents the Secretary of Defense from reassigning appointment authority to a subordinate is constitutionally compelled. The question whether Congress may permit the President or the head of a department to delegate appointment authority to an officer below the head of a department is a difficult one, and we cannot provide a definitive answer at this time. As noted, delegation clearly is not to be permitted for officers requiring Senate confirmation. However, neither the Attorney General nor this Office has definitively answered the question with respect to inferior officers who do not require Senate consent.

The Department of Justice has now provided a definitive answer. In the Third Circuit, there is ongoing litigation about whether Alina Habba can properly serve as Attorney General. Yesterday, a brief was filed by the Attorney General, the Deputy Attorney General, and others. I think this brief clearly represents the institutional position of the Department of Justice.

The brief squarely settles that the power to appoint inferior officers cannot be delegated:

The difference between acting service and delegated functions would still have significance for many other PAS officials under the FVRA. For example, because the power to appoint inferior officers is a non-delegable function constitutionally vested in an agency head, Lucia v. Securities and Exchange Commission, 585 U.S. 237, 244 (2018), an Acting Attorney General may appoint inferior officers under the FVRA, but an individual who has merely been delegated the Attorney General's powers under 28 U.S.C. § 510 may not; it would make no sense, however, to leap from that proposition to the defendants' conclusion that the FVRA also atextually preempts delegations that are valid under § 510.

Under 28 CFR §§ 0.15(b)(1)(ii), the Attorney General has delegated to the Deputy Attorney General, as well as the Associate Attorney Generals, the power to appoint certain positions. In light of the brief, these positions could not be considered inferior officers. Rather, at most, they must be "employees" of the United States. And per Buckley, these employees could not exercise "significant authority."

I'll need to chew on this matter a bit more.

The post DOJ Argues That Agency Head Cannot Delegate Power To Appoint Inferior Officers appeared first on Reason.com.

[Irina Manta] More on "Chatfishing" on Dating Apps and in Texting

[AI use continues spreading in online dating dialogue]

I blogged previously about the role and ethics of AI use in the online dating communication context. The Guardian published over the weekend a piece discussing the proliferation of this practice. One of the problems it highlights is the mismatch that individuals encounter between who they thought they were texting and the person that shows up on a date and is significantly less articulate or attuned. In that sense and on average, it likely makes online dating (as well as getting to know each other via texting generally) an even less efficient process than already.

Some of the uses of AI mentioned in the interviews conducted for the Guardian article lean toward the comical, such as this one:

As 32-year-old Rich points out, though, "it's not like using ChatGPT guarantees success". When he met someone in a bar one Friday night and swapped social media handles, he asked AI what his next move should be. ChatGPT discerned that sending an initial message on Monday midmorning would set the right pace. "Then it gave me some options for what the message could be," says Rich. "Keep it light, warm, and low-stakes so it reads as genuine interest without urgency," the bot advised. "Something like: Hey Sarah, still laughing about [tiny shared moment/reference if you've got one] – good to meet you!" Rich went back and forth with ChatGPT until he felt they'd hit upon exactly the right message ("Hey Sarah, it was lovely to meet you") but sadly she never replied, he says. "It's been two weeks now."

Rather shocking that such a witty line wasn't an instant winner (though to be fair, whatever happened before that probably left a negative or lukewarm impression enough not to inspire desire for another meeting likely couldn't be overcome by ChatGPT anyway…).

Some other AI uses, however, bring up heavier subjects, such as here:

Still, there was one date that pricked his conscience. He was doing the usual copy-and-paste, letting ChatGPT do the heavy lifting, "when a girl started talking about how she'd had a bereavement in her family". ChatGPT navigated her grief with composure, synthesising the kind of sympathy that made Jamil seem like a model of emotional literacy. "It said something like, 'I'm so sorry you're going through this, it must be really difficult – thank you for trusting me with it,'" Jamil recalls. When he met the girl in real life, she noted how supportive he'd been in his messages. "I felt bad – I think that was the only time I thought it was kind of dishonest. I didn't tell her I'd used ChatGPT but I really tried to message her myself after that."

In this kind of setting, ethically speaking, motive matters. Was Jamil mainly being lazy, manipulative, or just insecure about how to approach the situation and thought ChatGPT would help him to do right by his interlocutor's grief? There's no way to know from a brief journalistic set of quotations, but it brings us closer to one of the central guidelines about when use of AI may be acceptable.

At the heart of it, it may come down to the Platinum Rule, which is to treat others the way one believes that they would want to be treated. And in a situation of bereavement, most people would probably not find it acceptable for someone to use AI out of laziness but would at least tolerate it if it was done in a good-faith attempt to comfort in an appropriate tone. Whether the behavior fell into column A versus B is likely to reveal itself once in-person interactions begin or intensify. It is fair to say, however, that the existence of modern AI tools has made it more key than ever to place a lot less stock in what people (now potentially more assisted by technology than previously) say as opposed to what they do.

The post More on "Chatfishing" on Dating Apps and in Texting appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Errata in The Heritage Guide to the Constitution

The Heritage Guide to the Constitution is my fifth book. Like with my previous publications, I did everything in my power to eliminate typos and other errors before publication. And, like in the past, as soon as the book is sent to the printers, I discover more typos and errors. Finally, like in the past, as soon as Amazon ships the book, people start writing to me with errors.

I already compiled an errata list. We will make these changes for the second printing, and the online edition (stay tuned).

If you happen to spot an error, please email me: josh-at-joshblackman.com.

The post Errata in The Heritage Guide to the Constitution appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] A "Bombshell" Or a Dud?

[Once again, originalism is only elevated when a scholar with conservative credentials opposes conservative jurisprudence.]

Yesterday, the New York Times published an article, titled Originalist 'Bombshell' Complicates Case on Trump's Power to Fire Officials. Adam Liptak highlights a new essay by UVA Law Professor Caleb Nelson that casts doubt on the claim that the Article II Vesting Clause includes a removal power.

Nelson did not say anything particularly novel in this 3,000 word essay. Indeed, he cites the work of scholars like Jed Shugerman and Julian Davis Mortenson who have written hundreds of pages on this issue in recent years.

So why did Nelson warrant a glowing profile in the newspaper of record? Simple: a law professor with conservative credentials opposed conservative jurisprudence. Here, a Thomas clerk published a short essay that bucks the conventional wisdom on the right. Will Baude hailed the essay on BlueSky as a "bombshell." I think it is fitting that the Times quoted Baude's announcement, as he was the subject of a similarly positive NYT piece by Adam Liptak in 2023.

Barely two years ago, Will and his co-author, Michael Stokes Paulsen wrote a 150-page article arguing that Donald Trump was unquestionably disqualified by the presidency under Section 3. (Seth Barrett Tillman and I were on the other side of that debate.) In the wake of January 6, there were many scholars who had written that Trump was disqualified. But what made the Baude/Paulsen article stand out was their conservative credentials. Baude, in particular, had clerked for Chief Justice Roberts.

I think there is something of a pattern. The mainstream media will elevate originalism when it bucks conservative orthodoxies. But when originalism unquestionably supports a conservative position, it is described as fringe and radical.

Ultimately, I'm not sure that Nelson's article moves the needle, at all. I don't need to remind everyone that the Baude and Paulsen position received zero votes at the Supreme Court. Justice Thomas made up his mind about Humphrey's Executor a long time ago. He stated the issue plainly in Seila Law.

I don't think Justice Thomas will wake up and say, "my goodness, because of a 3,000 word essay by a law professor I hired three decades ago, I have to radically alter everything I think about the separation of powers." A former Thomas clerk once told me a story of how he tried to persuade the boss that he was wrong about some case. Thomas sat patiently and listened as the clerk presented his argument. After the clerk was done, Thomas said he felt even more convinced that his initial position was correct.

I think it far more likely that Thomas cites, and continues to cite, another former clerk who is also on the University of Virginia faculty: Sai Prakash. Indeed, Thomas cited Prakash in Seila Law:

1 For a comprehensive review of the Decision of 1789, see Prakash, New Light on the Decision of 1789, 91 Cornell L. Rev. 1021 (2006).

Why is it that Prakash, whose credentials are very close to those of Nelson, doesn't even merit a mention by the Times? Prakash has been engaging in a lengthy debate with Mortensen and Shugerman on this issue. Indeed, Prakash co-authored an article with another member of the UVA faculty, Aditya Bamzai, in the Harvard Law Review.

Still, all the focus now is on Nelson, who wrote a short essay. If you read down to the last paragraph of Nelsons piece, you will see how tentative the claim is:

I am an originalist, and if the original meaning of the Constitution compelled this outcome, I would be inclined to agree that the Supreme Court should respect it until the Constitution is amended through the proper processes. But both the text and the history of Article II are far more equivocal than the current Court has been suggesting. In the face of such ambiguities, I hope that the Justices will not act as if their hands are tied and they cannot consider any consequences of the interpretations that they choose.

This is not exactly lion-hearted originalism. It isn't even faint-hearted originalism. Call it "inclined-to-be" originalism?

Ultimately, I think this new entry to the field will not be a bombshell, but will be a dud.

The post A "Bombshell" Or a Dud? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "Viewpoint Diversity" Requirements as a New Fairness Doctrine: Viewpoint Diversity Rules as to Students

I have an article titled "Viewpoint Diversity" Requirements as a New Fairness Doctrine forthcoming in several months in the George Mason Law Review, and I wanted to serialize a draft of it here. There is still time to edit it, so I'd love to hear people's feedback. The material below omits the footnotes (except a few that I've moved into text, marked with {}s, as I normally do when I move text within quotes); if you want to see the footnotes—or read the whole draft at once—you can read this PDF. You can see my argument about why viewpoint diversity requirements are likely to chill controversial faculty speech here; here is a brief follow-up section as to the problems with imposing such requirements as to students:

[E.] Viewpoint Diversity Rules as to Students

The Administration's letter to Harvard also calls on "audit[ing] the student body" and not just the faculty. But the problem of people being encouraged to misreport their political beliefs is likely to be even more severe with regard to the auditing of students. For college students, any such audit is likely to be based entirely on self-reporting, since most students will have little history of party registration, even less history of political donation, no formal publication record of the sort that academics have, and (again, for most students) little politically minded social media commentary.

Yet if universities try to achieve viewpoint diversity by asking would-be students their political beliefs when they are applying, many students will likely claim beliefs that they see as likely to increase their chance of admission (e.g., by claiming to be conservative or centrist when they think they'll be penalized for being liberal, or claiming to be liberal or centrist when they think they'll be penalized for being conservative). This is especially so since this would generally be a very safe lie. The terms are vague enough that it will be hard to prove that people were misdescribing themselves. And even if, after they come to college, students become activists on a side contrary to the one they claimed, they can always just say that they've changed their minds. Indeed, the terms are vague enough that students can even persuade themselves that they are telling the truth. "No, really, I'm not that liberal—I'd say I'm more of a moderate" is an easy story to tell yourself once you learn that calling yourself a liberal would decrease your chances of admission.

To be sure, universities might measure their students' viewpoint diversity by asking students their political beliefs when they are already in school. But then to cure any lack of viewpoint diversity, they would still have to ask future applicants for their views, and risk the strategic responses that I describe above. And even the current students might feel an incentive to respond inaccurately: After all, if left-wing (or right-wing) activist students realize that so labeling themselves will increase the university's pressure to admit students from the other side for ideological balance, those students might well conclude that it's better to mischaracterize their positions in the viewpoint diversity survey.

The post "Viewpoint Diversity" Requirements as a New Fairness Doctrine: Viewpoint Diversity Rules as to Students appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers