James Maliszewski's Blog, page 57

May 1, 2024

Scary Enough

I'm a big fan of the horror genre, whether books, movies, or roleplaying games. As a kid growing up in the 1970s, horror and the occult were in the air, so it was difficult not be exposed to it. Consequently, when I saw the first advertisements for Call of Cthulhu in 1981, I knew I had to get a copy. CoC quickly became one of my favorite games, joining Dungeons & Dragons and Traveller to form the Holy Trinity of RPGs from my youth. In the years since, I haven't played Call of Cthulhu as much as I've used to, but I still regard it very highly and hope one day to have the chance to play it again.

I'm a big fan of the horror genre, whether books, movies, or roleplaying games. As a kid growing up in the 1970s, horror and the occult were in the air, so it was difficult not be exposed to it. Consequently, when I saw the first advertisements for Call of Cthulhu in 1981, I knew I had to get a copy. CoC quickly became one of my favorite games, joining Dungeons & Dragons and Traveller to form the Holy Trinity of RPGs from my youth. In the years since, I haven't played Call of Cthulhu as much as I've used to, but I still regard it very highly and hope one day to have the chance to play it again.One of the interesting things about horror RPGs is that almost no one who plays them is ever really frightened. Someone might play his character as if he were frightened, but I don't think I've ever seen anything in a game genuinely scare a player, at least not deliberately. That never really bothered me, because, let's face it, it's not that easy to induce fear while sitting around a table in a well-lit room with a bunch of your friends. Plus, would it even be fun to play a game where you're routinely frightened in the way you might be watching a movie or reading a book?

Even so, there's always been part of me that, as a referee, has wondered about the question of why we play horror RPGs and what we hope to get out of them. That's why I was so taken with a section in the Warden's Operations Manual for the new edition of the sci-fi horror game Mothership that addresses this very issue:

Actually scaring your players, like they might get scared watching a horror film or playing a video game is an incredibly rare thing. It is not a measure of a successful game night. Most of the time, your players simply want to have fun in a horror setting. This means they want to play characters who feel afraid, while they the players sit back eating chips and rolling dice. Sometimes you have players who love to be scared and really get into it. If that's the case, enjoy it! But don't feel bad if it doesn't happen every week. Instead focus on keeping the tension escalating.

I think this is quite close to the truth of it, at least as I've experienced the play of horror RPGs over the years. The horror present in your typical Call of Cthulhu scenario, for example, is largely intellectual rather than emotional. Very few players will ever feel frightened or disgusted by events in the game, even if they understand that their characters, being ordinary people, would probably feel those things within the context of the game world. This makes for a better roleplaying experience in at least two respects. First, it doesn't set the bar so high for the referee that he'll never achieve "success." Second, it helps maintain a little distance between the players and the often horrific things with which their characters must deal.

That said, even highly intellectualized fear, horror, and revulsion are all useful tools for the referee in presenting an engaging setting and/or scenario. After all, fantasy can be frightening and confronting frightening things in a fictional context can be very appealing to a lot of people, especially those among us who are normally not very brave. In that respect, it's not much different than the more general experience of fictional danger found in many common RPG activities, like combat or exploration. It's fun for our characters to do or to endure things that we'd never be able to or indeed want to, isn't it?

Fake Nerd Holidays

Apparently, because today is May 1 – May Day in many European countries – someone has decided that it's also the made-up "holiday" of Traveller Day, for obvious reasons.

I must tell you: I don't like this. I absolutely loathe Star Wars Day and its nonsensical date (May 4). I feel similarly about Alien Day (April 26), which, like Traveller Day, I had never even heard of until this year. Much like forced humor, forced holidays grate on my nerves, perhaps because they're usually created by companies looking for new ways to squeeze money out of one of their customers rather than the holidays being organic bottom-up expressions of respect and affection.

I must tell you: I don't like this. I absolutely loathe Star Wars Day and its nonsensical date (May 4). I feel similarly about Alien Day (April 26), which, like Traveller Day, I had never even heard of until this year. Much like forced humor, forced holidays grate on my nerves, perhaps because they're usually created by companies looking for new ways to squeeze money out of one of their customers rather than the holidays being organic bottom-up expressions of respect and affection. I don't know who came up with Traveller Day or the intentions behind it. Maybe it really does represent something genuinely spontaneous and fan-driven. If so, then why not choose a more suitable date for commemoration, like the date of its original publication? Wouldn't that make more sense? May 1 feels like a marketing stunt rather than something real, but what do I know?

Bah, humbug.

Which Is It?

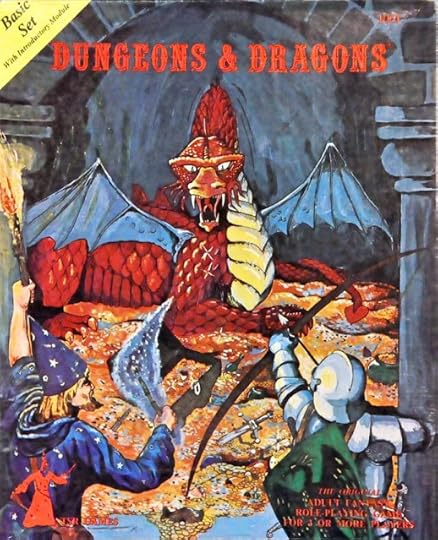

The first RPG I ever owned was the 1977 Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set, whose cover looked like this:

If you look in the bottom righthand corner, you'll see that it calls itself "the original adult fantasy role-playing game." Take note of the italicized word and its spelling, particularly its use of a hyphen between "role" and "playing."

If you look in the bottom righthand corner, you'll see that it calls itself "the original adult fantasy role-playing game." Take note of the italicized word and its spelling, particularly its use of a hyphen between "role" and "playing." Now, here's the cover of the 1981 Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set:

If you look at its bottom righthand corner, you'll see that the hyphen has disappeared – "role playing" is presented as two separate words. The 1984 D&D Basic Set restores the hyphen, which brings it in line with the general usage of the AD&D hardcover volumes. However, TSR was quite inconsistent on this point over the years. If you look at the covers of its RPGs throughout the '70s and '80s, you'll see both "role-playing" and "role playing." For example, Gamma World calls itself a "role-playing game," while Star Frontiers is a "role playing game." So, which is it?

If you look at its bottom righthand corner, you'll see that the hyphen has disappeared – "role playing" is presented as two separate words. The 1984 D&D Basic Set restores the hyphen, which brings it in line with the general usage of the AD&D hardcover volumes. However, TSR was quite inconsistent on this point over the years. If you look at the covers of its RPGs throughout the '70s and '80s, you'll see both "role-playing" and "role playing." For example, Gamma World calls itself a "role-playing game," while Star Frontiers is a "role playing game." So, which is it?Looking over my collection of games, at least those from before 1990, both usages seem quite commonplace, though I detect a slight preference for the hyphenated form. No publisher is completely consistent on this point, though there are some (like GDW) that do a better job at it than others. Sometime in the mid-1980s, a third variant – roleplaying, as a compound word – starts to appear. The earliest game I own that makes use of it is Pendragon (1985), but it's possible I've missed an even earlier instance of this. Nowadays, I see "roleplaying" quite a lot, though the hyphenated version persists.

Do you have a preference? Looking at my own writing, I see that I tend to favor the compound word over the two earlier versions. I'm not quite sure why that is. I wonder if "roleplaying" arose for typographical or graphic design reasons or something equally mundane. Given the general lack of consistency even within a single publisher's products, I doubt that there was a conscious effort to move from one form to another. More than likely, the shift is for other, less obvious reasons. Still, I find myself wondering about the shift and my own preference for one form over the others. I'd be very curious to hear the thoughts of readers on the matter.

Now Under Construction

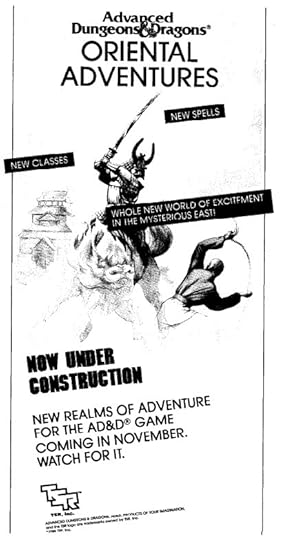

Because I did a Retrospective post on Kara-Tur: The Eastern Realms last week, I was reminded of how excited I was by the announcement that the long-awaited Asian expansion to AD&D, Oriental Adventures. OA was a long percolating project about which Gary Gygax had talked for years beforehand, in part because he felt the monk class didn't belong in "standard" AD&D, given its inspiration in the legends of the Far East. Despite this, there didn't seem to be any evidence that such a project was likely to happen anytime soon and I largely put it out of mind.

Then, without warning, in issue #102 of Dragon (October 1985), this advertisement appeared:

Now, we'd finally get official game rules for samurai and ninja and martial arts and everything else we fans of Kurosawa and Kung Fu Theatre had long thought should be brought into AD&D. To say that Oriental Adventures was greatly anticipated, at least among my friends and myself, is something of an understatement and this ad, featuring a washed out, black and white version of Jeff Easley's cover painting, is a big part of the reason why. Though my feelings about OA are now a bit more mixed, I still have many fond memories of it – and the long October I spent waiting for November 1985 to roll around so that I could finally lay my hands on it.

Now, we'd finally get official game rules for samurai and ninja and martial arts and everything else we fans of Kurosawa and Kung Fu Theatre had long thought should be brought into AD&D. To say that Oriental Adventures was greatly anticipated, at least among my friends and myself, is something of an understatement and this ad, featuring a washed out, black and white version of Jeff Easley's cover painting, is a big part of the reason why. Though my feelings about OA are now a bit more mixed, I still have many fond memories of it – and the long October I spent waiting for November 1985 to roll around so that I could finally lay my hands on it.

April 30, 2024

Retrospective: The Book of Wondrous Inventions

I have a complicated relationship with humor in roleplaying games. I unreservedly celebrate games like Paranoia and Toon that are explicitly humorous in tone and content, having had a lot of fun with them in the past. Likewise, I know very well that even the most "serious" RPG campaigns are likely to include moments of unexpected levity and goofiness and there's absolutely nothing wrong with that. After all, even Shakespeare included moments of comic relief in his most harrowing tragedies.

I have a complicated relationship with humor in roleplaying games. I unreservedly celebrate games like Paranoia and Toon that are explicitly humorous in tone and content, having had a lot of fun with them in the past. Likewise, I know very well that even the most "serious" RPG campaigns are likely to include moments of unexpected levity and goofiness and there's absolutely nothing wrong with that. After all, even Shakespeare included moments of comic relief in his most harrowing tragedies.At the same time, I wince at most puns and have a particular dislike of forced attempts humor in roleplaying games. Over the years, I've seen enough well-meaning but ultimately disastrous attempts to "lighten the mood" that my natural inclination is to be suspicious of humor in RPGs. That's not to say I hate it unreservedly, only that I recognize how easy it is for this sort of thing to go badly wrong.

With all that in mind, I hope I can be forgiven for having very mixed feelings about The Book of Wondrous Inventions. Compiled by Bruce Heard from nearly fifty contributions by a wide variety of authors (more on that in a bit) and published in 1987, The Book of Wondrous Inventions is clearly intended to be a companion volume to The Book of Marvelous Magic, right down to its title. But whereas the content of The Book of Marvelous Magic was largely serious in tone – or at least no less serious than the standard lists of (A)D&D magic items – this new book was intentionally written with humor in mind. In his introduction, Bruce Heard writes the following:

These inventions should be viewed with humor. They provide fun and an uncommon change of pace whenever they appear in the game.

There's nothing inherently wrong with this approach, especially if one is sparing in their use within a given campaign. Almost since its inception, D&D has included its fair share of magic items that could well be viewed as silly. The apparatus of Kwalish, anyone? The difference here, I think, is that previous goofy magic items were spice, those included here are the main course – or, at least, they give the impression of being so, because there are so many of them under a single cover. That's not really their fault, but I can't deny that it bugged me a bit in the past and still bugs me a bit even today.

The magic items detailed in this book are all unique and highly idiosyncratic, the products of singular individuals intent on creating something truly unusual. There's Aldryk's Fire Quencher (a magical water sprinkler), Brandon's Bard-in-a-Box (a portable music system), Kruze's Magnificent Missile (self-explanatory), Volospin's Dragonfly of Doom (a magical attack helicopter for hunting dragons), and so on. As you can see, nearly all of the items described reproduce the effects of a post-medieval – and likely modern-day or futuristic – technological device within the idiom of vanilla fantasy. There's not much cleverness on display here. Instead, the entries are all "What would a magical vacuum cleaner be like?" or "Wouldn't a magical pinball machine be funny?"

The combination of the fundamentally technological framing of these items and their banality results in a very sub-par book, even given Heard's stated intention that they "provide fun" and a "change of pace." It's particularly baffling, because many of the entries are written by talented and imaginative people, like Ed Greenwood, Jeff Grubb, and even Sandy Petersen. I can only assume that they were all specifically instructed to come up with stuff that would feel appropriate in Wile E. Coyote's Acme Catalog – or perhaps from the minds of Dragonlance's tinker gnomes. The end result is not, in my opinion, either useful as a source of ideas for an ongoing D&D campaign or even of mirth. It's dull, predictable, and, above all, forced, which is a great shame, because I admire many of the book's contributors.

Sadly, the book is done no favors by its accompanying illustrations. Much as I adore the work of Jim Holloway, one of the few artists who really understood the humor inherent in typical RPG situations, his artwork here is simply so goofy that it makes it impossible to imagine using any of its inventions with a straight face. Maybe that's the point. Maybe you're not supposed to be able to do so. Maybe I'm just a killjoy lacking in a funny bone. Ultimately, that's not for me to judge. I can only say that, when I bought this back in 1987, I instantly regretted and have never used it, except as a cautionary tale of what happens when you try to inject "humor" into a campaign rather than allowing it to arise organically through play.

Oh, the pain ... the pain!

Oh, the pain ... the pain!

Polyhedron: Issue #24

Issue #24 of Polyhedron (July 1985), with its cover illustration by Roger Raupp, is another one I remember very clearly from my youth – and the cover is a big part of the reason why. When I first saw this odd collection of characters, I honestly had no idea what I was looking at. Were they supposed to be orcs or half-orcs or something else entirely? As I turned out, my guess wasn't far from the truth, but that initial perplexity compelled me to read the issue with great interest. Nearly forty years later, I still remember it.

Issue #24 of Polyhedron (July 1985), with its cover illustration by Roger Raupp, is another one I remember very clearly from my youth – and the cover is a big part of the reason why. When I first saw this odd collection of characters, I honestly had no idea what I was looking at. Were they supposed to be orcs or half-orcs or something else entirely? As I turned out, my guess wasn't far from the truth, but that initial perplexity compelled me to read the issue with great interest. Nearly forty years later, I still remember it."Notes from HQ" can be quickly dispensed with, since most of it concerns RPGA matters of little lasting interest. The main thing worth discussing is a note indicating that, in response to pleas from the editor in previous issues, there have been a number of submissions from RPGA members. Indeed, Penny Petticord states that "we have not rejected a single article." She quickly adds, though, that submissions are still very few in number and that "only a fraction of the so-called active membership has contributed." At the time there were supposedly "over 8000" RPGA members worldwide, so I can sympathize with Petticord's lament about the small number of submissions.

"Letters" is quite interesting this issue. First, there's a letter in which a reader complains about the heavy D&D focus of Polyhedron, as well as the lack of support for Marvel Super Heroes. In response to the first part, the editors explain that Polyhedron can only publish those articles that are submitted to it, so, if anyone wants to see more non-D&D content, they'll need to make it happen themselves. As I think I said before, I wish I'd paid more attention to this sort of stuff when I was a subscriber, because I probably would have had better luck getting published in Polyhedron than I ever did in Dragon. In answer to the second part, the editors point out that, because MSH is a licensed game, Marvel itself must review and approve everything it publishes for the game. This makes it harder for any writer, especially those outside the TSR staff, to produce new articles to support it. Also among the letters published are a couple discussing the bad publicity Dungeons & Dragons is getting in their area, a consequence of the ongoing Satanic Panic. If I hadn't lived through those times, I'd hardly believed such things happened!

"Secrets of Success" by Steve Null offers tips on playing in RPGA tournaments. Never having participated in RPGA events, I must say I only briefly skimmed this article and saw nothing worthy of comment here. "Unofficial New Magic-User Spells" by Jon Pickens continues what he began in issue #22. The selection of new spells continues to focus replicating the effects of AD&D magic items, which is fine, but I'd have liked a little more variety myself. More notable, I feel, is that, like its predecessor, it includes the word "unofficial" in its title – a reminder that nothing that appears in Polyhedron carries the official TSR seal of approval.

Part I of Frank Mentzer's AD&D adventure, "Needle," appears in this issue. Designed for characters of levels 8–10, this is another tournament adventure offered for the delectation of readers of Polyhedron, like most of the adventures published in its pages previously. The adventure concerns an expedition to locate and examine a powerful magic item – the titular Needle – that is found in a ruined city located in a far-off land. The characters are all members of an adventuring guild called SMART, which stands for Syndicate of Master Adventurers for the Recovery of Treasure. All the pregenerated characters have what I assume (hope?) are merely nicknames, like Slim, Smiley, Blondy, and Blaze. To be honest, I found this nomenclature detracted from my enjoyment of scenario, which is otherwise decent, filled with lots of challenges and puzzles. Maybe it's just me, but I prefer a slightly more serious tone when it comes to things like names.

Errol Farstad's "How Reviews are Done" is an overview of how RPGs and RPG products will be reviewed in Polyhedron, since such reviews are a new future in the newszine. All games are given a Difficulty rating from 1 to 4, with 1 being the easiest to learn for a newcomer and 4 being the hardest. Then, the product is rated on a scale of 1 to 10 in three other categories: Packaging, Rules and Explanations, and Miscellaneous. Taken together, these four ratings contribute to its Overall score, rated from 0 to 4 Stars. With the explanations out of the way, Farstad reviews Star Trek the Role Playing Game, to which he gives an overall rating of 3 Stars out of a possible 4. He had some minor (and frankly nitpicky) complaints about the game, which did not detract from his otherwise very positive opinion of it. Being a big fan of the old FASA game, I could not disagree with his assessment.

"The Grond Family & Friends" by Roger E. Moore is the first installment in a new series called "The New Rogues Gallery." Like the book after which its named, this series is intended to present write-ups and illustrations of characters from people's home campaigns – basically "Let me tell you about my character(s)" in written form. The eponymous John Grond is a half-ogre and it's his friends and family whom Roger Raupp depicted on the cover of this issue. Half-ogres were briefly described as a possible player character race by Gary Gygax in issue #29 of Dragon (September 1979). Moore apparently liked the idea enough to adopt and adapt for his own use. The article presents six characters, ranging from Grond himself (a 16th-level fighter) to his wife (a 4th-level half-ogre cleric) and followers, like Boron the Moron, a full ogre of limited intelligence.

"Fletcher's Corner" by Michael Przytarski – and people say my name is hard to spell – is the start of a new column devoted to "solving the everyday problems faced by anyone who judges role playing games." In short, it's another referee's advice column. Consequently, I expect it'll be filled with lots of good insights and advice that will be genuinely useful to someone who's sitting behind the screen for the first time but rather dull to the veterans among us. That's OK: there are always newcomers in need of advice and that's good for the hobby. For his inaugural column, Przytarski takes up the topic of introducing new characters (and, by extension, new players) to a campaign. It's a good topic and his advice is solid, though nothing I haven't heard before (or come to understand through years of play). It'll be interesting to see what he tackles next and whether I find it useful.

Concluding the issue is "Dispel Confusion," with answers to questions about D&D, AD&D, and Marvel Super Heroes. Sadly, none of the questions piqued my interest, because they were all very banal. Most pertained to discrepancies between two sections of the rules or details that had been inadvertently left out of the text – in short, the kinds of rules questions about which you can't say very much else. Personally, I've always enjoyed questions that afford the responder to pontificate a little about a philosophy of play or game design, but that's just me. Maybe next issue!

April 28, 2024

REVIEW: How to Make a Fantasy Sandbox

There were two great obsessions at the dawn of the Old School Renaissance: megadungeons and sandboxes. Each was a distinctive element of many of the foundational roleplaying game campaigns of the 1970s, like Blackmoor, Greyhawk, and Tékumel. Their rediscovery and promotion are among the lasting impacts of the OSR – so much so that both massive dungeons and open-ended hexcrawls are now permanent fixtures of the even wider RPG scene. Of the two, I'd say that megadungeons are probably the better understood and more commonly used, thanks in no small part to the many examples of them now available in print. Furthermore, a megadungeon is, in many ways, just a scaled-up version of a dungeon and almost everyone who's ever played a fantasy RPG, whether tabletop or electronic, knows what a dungeon is like and how it's constructed. However, sandboxes are, in my experience, both less common and less well understood. There are no doubt many reasons for this, but a big one, I think, is they require more preparation beforehand by the referee and preparation of a less formulaic sort than what's employed when designing a dungeon, regardless of its size.

There were two great obsessions at the dawn of the Old School Renaissance: megadungeons and sandboxes. Each was a distinctive element of many of the foundational roleplaying game campaigns of the 1970s, like Blackmoor, Greyhawk, and Tékumel. Their rediscovery and promotion are among the lasting impacts of the OSR – so much so that both massive dungeons and open-ended hexcrawls are now permanent fixtures of the even wider RPG scene. Of the two, I'd say that megadungeons are probably the better understood and more commonly used, thanks in no small part to the many examples of them now available in print. Furthermore, a megadungeon is, in many ways, just a scaled-up version of a dungeon and almost everyone who's ever played a fantasy RPG, whether tabletop or electronic, knows what a dungeon is like and how it's constructed. However, sandboxes are, in my experience, both less common and less well understood. There are no doubt many reasons for this, but a big one, I think, is they require more preparation beforehand by the referee and preparation of a less formulaic sort than what's employed when designing a dungeon, regardless of its size.Fortunately for those of us who enjoy fantasy sandboxes – my ongoing House of Worms campaign, for example, is something of a sandbox – there are resources out there to aid in their creation. The very best of them has long been Rob Conley's twenty-four part series on "How to Make a Fantasy Sandbox," whose first post appeared in the far-off time of September 2009. It's a terrific collection of blog posts, filled with good ideas and wisdom drawn from years of refereeing sandbox campaigns. I long ago bookmarked many of the posts and refer to them often in my own work, such as designing the Eshkom District for Secrets of sha-Arthan. If you've never read these posts before, I highly recommend you do so.

An equally good – maybe better – option would be to purchase How to Make a Fantasy Sandbox, 180-page compilation of Conley's blog posts, rewritten and expanded with examples, maps, and artwork, available in PDF, softcover, or hardcover formats. In the book's introduction, Conley provides both a nice overview of what a sandbox campaign is and his own reasons for enjoying them:

One of my favorite things to do with Tabletop RPGs is to create interesting places with interesting situations and then let the players trash the setting in pursuit of adventure.

That certainly encapsulates much of the fun my players and I have had with my House of Worms campaign. He goes on:

My focus is not to create any type of narrative. Rather, I focus on helping my players experience living their characters' lives while adventuring. It's called a sandbox campaign because like in life, the players are free to do anything their characters can do within the campaign setting.

This wide-open world with unlimited choices can be very challenging as a Game Master/Referee. The key to dealing with this challenge is organization. A systematic approach is needed to break down the enormous task of dealing with an entire world. Organized into bite-size chunks that one can do in the time they have for a hobby.

Once again, I think Conley has done a fine job here of distilling the essence and unique pleasures of a sandbox campaign, while also recognizing that creating and maintaining such a campaign is not always easy, hence the need for a guide such as this one.

With that out of the way, he first describes and then elaborates upon thirty-three distinct steps in the process of designing a fantasy sandbox, from creating the map to placing settlements and lairs to choosing a "home base" for a new campaign. It's all presented clearly and methodically, so that it's easy for even a neophyte to follow. Best of all, Conley includes lots of examples throughout, drawn from his own experience of making fantasy sandboxes. Indeed, I'd go so far as to say that these examples are among my favorite parts of How to Make a Fantasy Sandbox. They not only serve as illustrations of design principles, but they also give some insight into Conley's own gaming past, which I found delightful and inspiring.

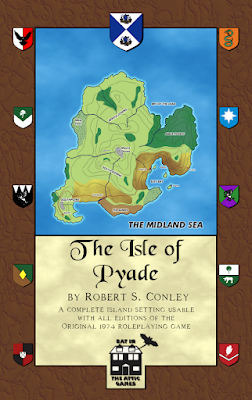

Throughout the text, the Isle of Pyade serves as the main example of how to implement the thirty-three steps to creating a fantasy sandbox setting. I found this very useful, because it's eminently practical and concrete rather than merely theoretical. If you follow the steps through, one by one, you'll see Pyade grow out of a blank hex map into a fully-fleshed out and complete location. Whether you're a novice or an old hand at this sort of thing, you'll learn a lot from the example of Pyade.

Throughout the text, the Isle of Pyade serves as the main example of how to implement the thirty-three steps to creating a fantasy sandbox setting. I found this very useful, because it's eminently practical and concrete rather than merely theoretical. If you follow the steps through, one by one, you'll see Pyade grow out of a blank hex map into a fully-fleshed out and complete location. Whether you're a novice or an old hand at this sort of thing, you'll learn a lot from the example of Pyade.By the conclusion of How to Make a Fantasy Sandbox, the Isle of Pyade is now ready to use. However, many of its details – maps, NPCs, encounter tables, etc. – are scattered across its 180 pages, making it less suitable for use as a reference. Should you wish to make use of Pyade yourself, a better option might be the separate The Isle of Pyade book (available in electronic, softcover, and hardcover format), which takes all the relevant details and consolidates them in one place for greater coherence and ease of use. There's also some additional content in the form of artwork and color reproductions of the original maps Conley made in the late 1980s. If you're fan of RPG "archeology" as I am, this only adds to the value of The Isle of Pyade.

How to Make a Fantasy Sandbox is a very good book, one I am very happy to own and one I am certain I'll refer to and make use of in the years to come. In addition to all the thoughtful insights and clear instructions Conley provides, he "shows his work," which is to say, he lays bare how he works and why, right down to including very useful appendices of resources, hexmapping guidelines, travel and encounter rules, and information about the process behind creating Blackmarsh , his earlier published sandbox setting. Aside from some minor quibbles about editing, I have only praise to offer about this book. If you have even the slightest interest in creating and refereeing a sandbox campaign, consider picking up a copy. You won't regret it.

April 23, 2024

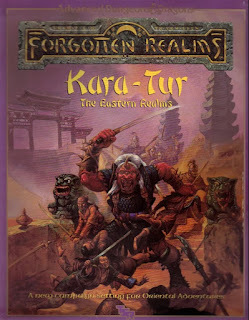

Retrospective: Kara-Tur: The Eastern Realms

I remember being very excited about the imminent release of the Oriental Adventures in 1985. Aside from the obvious reason – the introduction of playable ninja and samurai into Advanced D&D – I was quite keen to see "the Oriental lands of Oerth," as promised in the "Coming Attractions" section of Dragon #102. However, when OA was released in November of that year, there was no real evidence in that book that Kara-Tur, as its setting was called, had any connection whatsoever to the World of Greyhawk. This fact was further demonstrated when the first adventure module for use with Oriental Adventures,

Swords of the Daimyo

, came out the next year. Though it included a gazetteer of part of the land of Kozakura, there was once again no evidence that it had any connection to Gary Gygax's campaign setting.

I remember being very excited about the imminent release of the Oriental Adventures in 1985. Aside from the obvious reason – the introduction of playable ninja and samurai into Advanced D&D – I was quite keen to see "the Oriental lands of Oerth," as promised in the "Coming Attractions" section of Dragon #102. However, when OA was released in November of that year, there was no real evidence in that book that Kara-Tur, as its setting was called, had any connection whatsoever to the World of Greyhawk. This fact was further demonstrated when the first adventure module for use with Oriental Adventures,

Swords of the Daimyo

, came out the next year. Though it included a gazetteer of part of the land of Kozakura, there was once again no evidence that it had any connection to Gary Gygax's campaign setting.None of this really mattered, of course. Though I was a big fan of the World of Greyhawk, the connection (or not) between it and Kara-Tur had no impact whatsoever on my ability to use the rules of OA or my enjoyment of Kara-Tur. Even so, when TSR finally got around to releasing a boxed dedicated to detailing this vast continent and its peoples, I was more than a little baffled to see it had suddenly – and definitively – been placed in the Forgotten Realms setting. In retrospect, this made sense. In the aftermath of Gygax's ouster from the company, TSR had turned the Realms into the setting for AD&D. Everything that could be (and quite a few things that couldn't) were jammed into Ed Greenwood's brainchild, often to its detriment.

That didn't stop me from buying it, of course. Even in 1988, I was still very much a fanboy of TSR. Plus, I have always been something of a collector of campaign settings. Consequently, there was pretty much no chance that I wouldn't buy Kara-Tur: The Eastern Realms when it was released. Furthermore, it truly was an impressive product, consisting of two 96-page books and four double-sided, color maps of the region, all for $15 (about $40 in today's debased currency) – a steal! In addition, the books were amply illustrated by the late, great Jim Holloway, along with cover art by Jeff Easley. All in all, a terrific package and I'd have been foolish not to have picked it up.

The two integral books are unusual in that they're essentially a single book split into two volumes, right down to sharing page numbers. Volume I covers the lands of Shou Lung and T'u Lung – analogs of China during centralized and Warring States periods respectively – as well as Tabot (Tibet – ugh!), the Plain of Horses (Mongolia), and the Northern Wastes (Siberia). Volume II covers the lands of Wa and Kozakura – analogs of Japan during the Edo and Sengoku periods respectively – along with Koryo (Korea – ugh!), the Jungle Lands (Indochina), and the Island Kingdoms (Indonesia and the Philippines). It's an impressive amount of material, covering nearly every aspect of these lands that you can imagine, from geography and history to religion and politics. In addition, each realm gets NPCs, monsters, adventure ideas, and sometimes even new spells and magic items.

What's interesting is that Kara-Tur has no single author. Instead, different authors cover different lands, with the whole thing "coordinated" by David Cook, primary author of Oriental Adventures. The authors are a diverse bunch of people, most of whom were not employees of TSR at the time: Jay Batista, Deborah Christian, John Nephew, Michael Pondsmith, and Rick Swan. I'm not sure how common such a practice would have been at the time, but it strikes me as unusual, at least compared to many similar projects, which were usually the work of a single author. Consequently, Kara-Tur has a somewhat uneven feel to it, as if each author had a slightly different vision of what he had in mind while writing.

This unevenness comes through most clearly when you look at certain lands, whose histories, societies, cultures, and names(!) are lifted almost entirely from the real world, while others are a bit more fantastical. That's probably my biggest problem with Kara-Tur as a setting: it leans to heavily on the real world, particularly when compared to the larger Forgotten Realms, which is largely unmoored from any specific real world inspirations. Some of that, I suspect, has to do with the relative unfamiliarity of Asian history – and fantasy – in late 1980s America. It was probably much easier to look to the real world, file the serial numbers off, add some wizards, and be done with it. Unfortunately, the results are often quite mediocre, not to mention at odds with the overall tenor and feel of the Realms of which Kara-Tur was supposed to be the eastern half.

It's for this reason that, while I proudly bought and owned Kara-Tur: The Eastern Realms, I never really liked it. Compared to many of TSR's other campaign settings, this one seemed to me to be lacking in imagination. That's a great shame, because I feel like the cultures of Asia offer great fodder for the fantasy roleplaying games. Maybe that was a goal that was more difficult to realize almost four decades ago than it would be today, I don't know. Regardless, Kara-Tur falls well far of the mark of what I would have liked back in the day and even more so now. Alas!

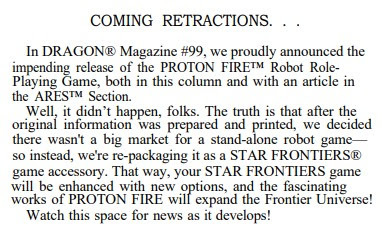

Coming Retractions ...

Speaking of weird little games, I stumbled across this in issue #101 of Dragon (September 1985):

This appeared at the end of the issue's "Coming Attractions" feature, which announced upcoming TSR game product releases. I've talked about Proton Fire on this blog a couple of times previously. In the first of those two posts, former TSR employee Steve Winter provides some additional context in the comments that's well worth checking out.

This appeared at the end of the issue's "Coming Attractions" feature, which announced upcoming TSR game product releases. I've talked about Proton Fire on this blog a couple of times previously. In the first of those two posts, former TSR employee Steve Winter provides some additional context in the comments that's well worth checking out. Probably because it was a science fiction RPG and science fiction is my genre of choice, I've long had a mild obsession with Proton Fire, the game that never was. Knowing that it did, in fact, exist in some form, but was never put into publishable form only feeds my desire to know more about it. Alas, I suspect this is a desire that shall never be sated!

Polyhedron: Issue #23

April Fool's issues were a staple of my youth, but they're very difficult to pull off. Partly, that's because humor can be very subjective and, partly, that's because most attempts at humor, especially in writing, are simply not very good. Consequently, I greeted the arrival of issue #23 of Polyhedron (April 1985) with some trepidation, despite its delightful cover by Tom Wham (take note of the bolotomus and snits in the bottom lefthand corner). However, I'm happy to say that this particular April Fool's Day issue is (mostly) pretty good. In fact, there are a couple of articles that I still find rather amusing even now – not laugh-out-loud funny, but intellectually droll, if that distinction means anything.

April Fool's issues were a staple of my youth, but they're very difficult to pull off. Partly, that's because humor can be very subjective and, partly, that's because most attempts at humor, especially in writing, are simply not very good. Consequently, I greeted the arrival of issue #23 of Polyhedron (April 1985) with some trepidation, despite its delightful cover by Tom Wham (take note of the bolotomus and snits in the bottom lefthand corner). However, I'm happy to say that this particular April Fool's Day issue is (mostly) pretty good. In fact, there are a couple of articles that I still find rather amusing even now – not laugh-out-loud funny, but intellectually droll, if that distinction means anything.

The issue begins with another installment of "News from HQ" that explains the nature of this issue:

If this is your first issue of the POLYHEDRON Newszine, I'd like to take this opportunity to welcome you to the RPGA Network, and let you in on the gag. Five out of the six issues you will receive with each year of membership will bring you club news, informative articles on your favorite game systems, and a chance to make a serious contribution to the hobby by sharing your ideas with other members. This is not one of those five.That's the kind of humor I'm talking about. The editorial goes on to explain that this issue was "conceived in madness and dedicated to the proposition that there is room for levity in gaming." I wholeheartedly agree, as anyone who's ever played in one of my campaigns will tell you. Yes, even the ones occasionally featuring unpleasant stuff. Games are supposed to be fun, after all, and it's important not to lose sight of that.

Much less funny is "An Official Policy Statement," whose entire shtick is using $64 words to say silly things about, in this case, "the sex lives of monsters." As I said above, humor writing isn't easy.

Fortunately, Gary Gygax gifts us with "Ultimists," a new character class for AD&D. Described as "fighting wizard-priests," Ultimists combine the abilities of clerics, magic-users, and monks. While their ability scores are rolled using only 3d6, the result of that roll is made by recourse to a chart, with most rolls resulting in scores of 15 or higher. This section of the class description pokes fun, as Gygax makes clear, those "enthusiasts" who objected to his system for rolling up the abilities of the then-new barbarian class. Ultimists also make use of spell points, because "memorizing spells is tedious, and the selection requires reasoning and intelligence applied to the game." Ouch. I can't really blame Gygax for using the article as an opportunity to vent about critics of AD&D. I imagine he was quite fed up with them by this point in his life.

Fortunately, Gary Gygax gifts us with "Ultimists," a new character class for AD&D. Described as "fighting wizard-priests," Ultimists combine the abilities of clerics, magic-users, and monks. While their ability scores are rolled using only 3d6, the result of that roll is made by recourse to a chart, with most rolls resulting in scores of 15 or higher. This section of the class description pokes fun, as Gygax makes clear, those "enthusiasts" who objected to his system for rolling up the abilities of the then-new barbarian class. Ultimists also make use of spell points, because "memorizing spells is tedious, and the selection requires reasoning and intelligence applied to the game." Ouch. I can't really blame Gygax for using the article as an opportunity to vent about critics of AD&D. I imagine he was quite fed up with them by this point in his life."Why Gargoyles Don't Have Wings (But Should) (An Alternative Viewpoint) by David Collins is an attempt to explain away Gary Gygax's concerns about the illustration of the gargoyle in the Monster Manual through a variety of vaguely humorous means. It's fine for what it is, but nothing special. A bit more interesting is Skip Williams's "The Lighter Side of Encounters" in which he presents a couple of humorous encounters from Frank Mentzer's Aquaria campaign as a way of demonstrating how humor sometimes finds its way into otherwise "serious" RPG campaigns. The encounters are all based on things that actually happened in Menzter's campaign, which is fascinating in its own right. Speaking of Mentzer – or, rather, Knarf Reztnem – his "Punishments to Fit the Crime" offer a pair of humorous stories whose conclusions depend on puns. They're basically Dad jokes in written form. Make of that what you will.

Frank Mentzer reappears with "New Magic Items," which offers up some fun (and funny) magic items from his Aquaria campaign, like the canister of condiments and the sweet tooth. Then, he reappears yet again – the man was a machine back in the day – with "Excerpts from the Book of Mischievous Magic," a spoof of his The Book of Marvelous Magic. This second article many amusing magical items like the awl of the above, cool hand lute, stocking of elf summoning, and practical yoke. It's all very silly, of course, but done with some real cleverness and an understanding that a good joke magic item isn't just a joke, but should also have some potential utility in a game. Mentzer clearly understood this.

Part 2 of David Cook's "In the Black Hours" AD&D adventure (Part 1 appeared in the previous issue) is the sole piece of "serious" material in the entire issue and thus feels very much out of place. Like its predecessor, it looks fun, reminding me a bit of something in which Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser or Conan, while working as a thief, might have become involved. "Dungeonsongs" is back to form, with a trio of humorous, RPG-themed songs set to well-known tunes, like "I'll Be a Wererat in the Morning" and "Green Slime." "Dispel Confusion" answers numerous important questions for D&D, AD&D, and Top Secret , like this one:

Bruce Heard pens "Zee Chef," another new character class for use with AD&D. A chef is designed specifically for NPCs "devoted to the culinary arts and learning more about native delicacies." It's a spellcasting class, with a host of new spells, including my favorite, edible glamour. Concluding the issue is "The Male of the Species" by – you guessed it – Frank Mentzer, which describes "emezons," the male counterparts to the amazons presented by Gary Gygax in issue #22. Some emezons are members of the new chef NPC class, while others are "exceptionally skilled at child raising, interior decorating, and hair styling." Hey, it was a different time.

Bruce Heard pens "Zee Chef," another new character class for use with AD&D. A chef is designed specifically for NPCs "devoted to the culinary arts and learning more about native delicacies." It's a spellcasting class, with a host of new spells, including my favorite, edible glamour. Concluding the issue is "The Male of the Species" by – you guessed it – Frank Mentzer, which describes "emezons," the male counterparts to the amazons presented by Gary Gygax in issue #22. Some emezons are members of the new chef NPC class, while others are "exceptionally skilled at child raising, interior decorating, and hair styling." Hey, it was a different time.All in all, not bad. Even someone as humor-impaired as myself chuckled a couple of times, which is quite a feat in itself. I'd still rather have had a "normal" issue of Polyhedron, but I can't deny the staff did a good job with their assignment. Well done!

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers