James Maliszewski's Blog, page 54

June 3, 2024

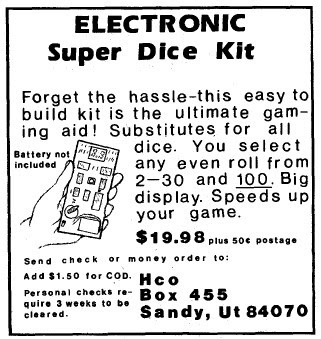

Electronic Super Dice Kit

Speaking of issue #62 of Dragon (June 1982), here's another advertisement from that same issue that stuck in my memory.

Now, electronic dice rollers were very trendy at the time, as evidenced by the existence of Dragonbone. They're yet another example of a transitional technology that is quickly superseded but that, for a time, manages to find a place in the market. For about a decade, starting in the mid-1970s, there were electronic versions of all sorts of things, spurred on by the decrease in the prices of integrated circuits, microprocessors, and transistors. Given that, I'm not at all surprised by the appearance of dice rollers like this.

Now, electronic dice rollers were very trendy at the time, as evidenced by the existence of Dragonbone. They're yet another example of a transitional technology that is quickly superseded but that, for a time, manages to find a place in the market. For about a decade, starting in the mid-1970s, there were electronic versions of all sorts of things, spurred on by the decrease in the prices of integrated circuits, microprocessors, and transistors. Given that, I'm not at all surprised by the appearance of dice rollers like this.What strikes me as unique about this advertisement is that, unlike Dragonbone, this was a kit to build your own "ultimate gaming aid" rather than a finished consumer product. I recall seeing "build your own radio" kits for sale in the Sears catalog and, of course, at Radio Shack, so it's not as if something of this sort was completely unheard of. However, at $19.98 (close to $65 in today's debased currency), this is very expensive for a do-it-yourself dice roller. Dragonbone was "only" $5 more, which makes me wonder if they had many sales. My guess is probably not, but there's no way to prove or disprove it now.

Regardless, the ad is yet another data point for the past is a foreign country file.

Mythical

Memory can be a powerful thing. Even at my advanced age, there are many things I can vividly recall about moments or events decades in the past. My memories are particularly strong about my earliest experiences playing RPGs, which shouldn't really come as a surprise, considering that I'm still involved in the hobby more than 40 years later.

A good example of this concerns issue #62 of Dragon (June 1982), which long-time readers may recall is the first issue of the magazine I ever owned. I purchased it from Waldenbooks, one of two chain bookstores found at my local shopping mall, and carried it around with me almost everywhere. I read that issue until its glorious Larry Elmore cover fell off, in the process committing nearly everything about it to memory.

I wrote a post about this a few years ago, in which I noted that the advertisements of that issue loom large in my memory, partly, I think, because I never saw the products being advertised on the shelves of any hobby shop or bookstore I visited. That was certainly the game with this advertisement:

Ysgarth is one of those RPGs I don't believe I've ever seen, despite the fact that I've known its name since 1982. It's one of those games that I often heard people talk about, but, even then, the impression they conveyed was almost of a mythical beast glimpsed only for a brief time in a dark and haunted forest rather than seen by the light of the sun. The same goes double for Abyss magazine, whose existence I knew only from advertisements like the one above.

Ysgarth is one of those RPGs I don't believe I've ever seen, despite the fact that I've known its name since 1982. It's one of those games that I often heard people talk about, but, even then, the impression they conveyed was almost of a mythical beast glimpsed only for a brief time in a dark and haunted forest rather than seen by the light of the sun. The same goes double for Abyss magazine, whose existence I knew only from advertisements like the one above. From what I understand, Ysgarth was an interesting but very complex fantasy roleplaying game. That complexity no doubt limited its appeal. Nevertheless, I find it strange that I never saw a copy of it in the wild during the '80s (or, for that matter, in the decades since). If anyone reading this has more direct experience of either Ysgarth or Abyss, I'd like to know your thoughts about it. For example, was it really as complex as legend would have it? Did you ever play it? Was it fun?

June 2, 2024

Yet More Thoughts about Skills

Last month, I presented a draft of a proposed new character class for inclusion in Secrets of sha-Arthan, the tomb robber. A common question about the class, both in the comments and in separate emails, concerned my inclusion of skills among the tomb robber's abilities. Long-time readers will no doubt remember that, in the early days of this blog, I was a fairly strong opponent of the inclusion of a skill system into class-based RPGs like Dungeons & Dragons. I was likewise an opponent of the thief class introduced in Greyhawk, viewing it as a self-justifying class for which there is no real need.

In the early days of the Old School Renaissance, such positions were pretty common, maybe even normative. This was, after all, the beginning of the re-evaluation of the virtues of Original D&D (1974), when a lot of us who'd either never played OD&D (raises hand) or who had long ago abandoned it in favor of later elaborations upon it, embraced it with zeal. Remember, too, that the OSR grew up amid the wreckage of Third Edition, whose mechanical excesses served as negative examples of what could happen when D&D's design "strays" too far from the foundations laid down by Arneson and Gygax in 1974. And one of 3e innovations was the addition of a skill system separate from class abilities.

Looking back on it now, I can see that my desire to avoid what I perceived as the flaws of Third Edition often led me to rhetorical intemperance. That's certainly the case with regards to skills, though, in my defense, I started to moderate my stance relatively early. That moderation was the result of play, particularly in my Dwimmermount megadungeon campaign, where I came to recognize just why the thief class and skill systems had organically evolved. Even so, I retained a certain wariness about both, since I continued to feel, as I still do, that character skills should never become a crutch for lazy play, which is to say, interacting with the game world solely through the game mechanic of skill rolls.

That said, what ultimately changed my opinion for good was my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign (take a drink). EPT, as many of you probably know, includes a skill system – the first, I believe, to appear in any roleplaying game. The skill system is certainly primitive by comparison to those in later RPGs, like Traveller or RuneQuest, of course. Indeed, the skill mechanic is vague and not very well integrated into EPT's overall play, but it's there. Consequently, when refereeing House of Worms, I made regular use of it.

What I discovered is that none of my earlier, hyperbolic concerns proved true at all. Skills never dominated play, nor did they encourage lazy play. The players rarely initiated skill rolls as a means to avoid having to think in-character or grapple with a problem presented to them. Instead, they might ask, "Does my character's Scholar skill give him any idea about the architectural style of this ruin?" or "Might my Jeweler-Goldsmith skill give me some idea of the value of this gemstone?" Sometimes, I'll call for an actual percentile roll to determine whether the skill grants the character the requested knowledge or not, but many times I'll simply make a judgment as to whether or not the skill is sufficiently expansive to grant it. Ultimately, the decision of how to adjudicate skills rested with me, the referee.

For me, that's the key. I dislike skill systems that demand a referee do something in response to a player-initiated successful roll. I much prefer those where skill use is a negotiation between player and referee and the final decision of whether a skill is relevant – or whether a roll is even needed – lies with the referee. Maybe that's common sense, but it's not the way I've often seen skill rolls used. Instead, they're more likely to be something a player employs to ensure a referee does (or does not) do a given thing within the context of the game. "I made a successful Stealth roll, so my character can sneak across the room without being seen by the guards" or "I got a success on my Persuasion roll and convince him not to report this to his superiors."

Skills – or perhaps competencies might be a better term – can be a good way for players and referees to cooperate in interacting with the setting and events within it. That's how I've been handling skills in House of Worms and I've taken that experience into Secrets of sha-Arthan as well – or at least I hope to do so.

May 31, 2024

How Do You End a Campaign?

As regular readers should know, I am an advocate for long campaigns, so much so that I feel that RPGs are best enjoyed when played in that way. Even so, that raises the question: when do you end a campaign?

I think about this often, because my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign is now several months in to its tenth year of weekly play, with a stable group of eight players, four of whom have been playing since March 2015 and one player who's played for almost as long. After nearly a decade of play, House of Worms is a perpetual campaign or very nearly so. There are so many character-driven goals, world events, long-term intrigues, and meddling NPCs to provide us with another decade's worth of play should we desire it. Whether that will actually happen is a separate matter.

More than likely, House of Worms will end much sooner than that, probably for mundane reasons, such as players having to stop playing due to real world obligations, changing schedules, etc. If so, it's quite possible there will be no "end" to it. Instead, it will simply stop in medias res. Would that be a bad thing? Would it be preferable to arrange something more conclusive and, dare I say, more satisfying? I'm honestly not sure. On the one hand, putting a proper cap on the campaign might feel better, in the sense that no one involved will have regrets about things being unresolved. On the other hand, I worry that such an approach borrows too heavily from literature or drama, which are very different kinds of entertainments from roleplaying.

Most of my past campaigns, both recently and in my youth, simply ended, usually due to boredom or distraction. For example, my Riphaeus Sector Traveller campaign, which I ran for three years, ended because I was exhausted and lacked the endurance necessary to run such an open-ended campaign at that particular time. The characters were in the midst of dealing with several different problems within the setting. When I announced I wanted to end the campaign, I didn't make an effort to wrap anything up; we simply ceased playing. No one involved seems to have minded, but I must admit that I occasionally think back with some regret on how abruptly the campaign ended. Of course, I'm not sure how I could have wrapped things up, since it was, as I said, a very open-ended campaign without a single contrived narrative.

I'm curious to hear what others think about this. I'm especially curious about others' experiences of ending campaigns that have run for a lengthy period of time (a couple of years or more). Did they end because they'd reached a natural stepping off point? Boredom? Real world issues? Did they end because there was a decision to end them? If so, how did they end? Did they simply cease or was there some kind of resolution? If there was resolution, was that resolution a consequence of prior events or was it engineered in order to provide a sense of closure?

This is a topic about which I'd really like to know more, so please share your experiences, stories, and insights, if you have them. Thanks!

May 30, 2024

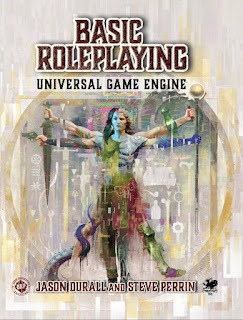

REVIEW: Basic Roleplaying Universal Game Engine

When it comes to venerable roleplaying game systems, the percentile skill-driven one first introduced in 1978's RuneQuest is unquestionably one of the most enduring and influential. Two years later, Chaosium released it as a separate 16-page booklet entitled

Basic Role-Playing

, which it then used as the foundation upon which to build many other classic RPGs, from Call of Cthulhu to Stormbringer to

Worlds of Wonder

. In the years since, many other games published by Chaosium and other companies have either directly made use of these rules or have been inspired by them. Like D&D's class-and-level system or the point-buy system of

Champions

, there can be no question that BRP is a mainstay of the hobby.

When it comes to venerable roleplaying game systems, the percentile skill-driven one first introduced in 1978's RuneQuest is unquestionably one of the most enduring and influential. Two years later, Chaosium released it as a separate 16-page booklet entitled

Basic Role-Playing

, which it then used as the foundation upon which to build many other classic RPGs, from Call of Cthulhu to Stormbringer to

Worlds of Wonder

. In the years since, many other games published by Chaosium and other companies have either directly made use of these rules or have been inspired by them. Like D&D's class-and-level system or the point-buy system of

Champions

, there can be no question that BRP is a mainstay of the hobby.Consequently, I was not at all surprised when Chaosium announced last year that a new edition of the game system would be released and released under the Open RPG Creative (ORC) License so that third parties could freely produce their own RPGs using this time-honored system. Of course, this latest iteration of Basic Roleplaying – take note of the disappearance of the hyphen – is a lot beefier than its original iteration. Weighing in at 256 pages, this latest version of the game is, in some ways, a bit more like GURPS in that it offers a large menu of rules options to choose from in creating one's own skill-driven RPG. This is a toolkit and not every tool is needed for every BRP-based game or campaign.

Despite the wide array of options available, drawn from an array of sources, the fundamentals of BRP remain largely the same since their first appearance more than four decades ago. Characters possess seven characteristics – Strength, Constitution, Size, Intelligence, Power, Dexterity, and Charisma – and a number of points with which to purchase skills. However, how those scores are generated, how many skills points are available, and so on are subject to multiple options. There are even optional characteristics, like Education, that a referee can choose to use if he so desires. The skill list, too, is customizable, as are the "powers" available to characters, like magic, mutations, or psychic abilities. This level of customization sets the tone for the entire book, hence my earlier reference to GURPS.

It's important to point out, though, that Basic Roleplaying includes lots of examples and advice throughout, in order both to illustrate the range of options and the pros and cons of making use of them. This is important, I think, because the book is dense and I can easily imagine that its density might be off-putting to newcomers. Even with all of the examples and advice, this probably isn't an easy book for inexperienced roleplayers to digest. There's a lot within its 256 pages and, while clearly written, even I found myself frequently flipping back and forth between sections to make sense of what I'd just read. I don't mean this as a damning criticism, but it's a reality nonetheless.

Ultimately, this is a danger all "universal" game systems must face. In an effort to include rules and procedures for anything that might come up in genres of games as different as fantasy and science fiction or modern-day and ancient world, the page count will inevitably rise. This is especially true for a game system like Basic Roleplaying, whose overall philosophy tends toward simulation, especially with regards to actions like combat. When one takes into account all the options available for nearly everything – including options that simplify the rules – the end result is undeniably ponderous.

Again, I say this not as a criticism but rather as an observation. Anyone who's played more than one BRP-based game knows how much they can differ from one another, in terms not just of content and focus but also in terms of complexity. Combat in RuneQuest, for example, is vastly more complicated than in Call of Cthulhu, never mind Pendragon . Yet, all three RPGs share unmistakable similarities that make it easier to pick up and play one if you already know how to play another, despite their differences. Basic Roleplaying provides rules, options, and guidance for building games as distinct as these and many more. I was genuinely amazed by the range of alternatives presented in this book, which is indeed a great strength. With this book, a referee would have no need for any others in constructing the BRP RPG to suit him and his players.

As a physical object, Basic Roleplaying is impressive, too. I own the hardcover version, which is sturdy and well-bound, with thick, parchment-like paper. The book is nicely illustrated with full-color art throughout. The layout is clear but dense, with the text being quite small in places (praise Lhankor Mhy for progressive lenses!). I haven't seen the PDF version, so I can't speak to its quality, but I cannot imagine it's much different. Since almost the entirety of its text has been released under the ORC License, you can take a look at its System Reference Document to see exactly what the book contains. If you do so, I think you'll understand what I mean about its density. At the same time, I'm very glad I own a physical copy of the book, but then I'm an old man who hates reading electronic documents, particularly long and complex ones like this book.

All that said, Basic Roleplaying is an excellent resource for anyone interested in using BRP for their own campaigns, regardless of the setting or genre. I highly recommend it.

May 29, 2024

Keeping It Rolling

A commenter to my Retrospective on From the Ashes wrote the following:

It's a known problem in fantasy worlds with metaplot that the stakes need to escalate until each new world-threatening villain and their attendant cataclysm is met with a yawn.

This is an accurate observation in my opinion and one that I've very deliberately tried to avoid in my ongoing House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign. Escalation of the sort the commenter mentions is, in my opinion, poison to the health of a long campaign. To show you what I mean, here's a very incomplete list of just a few of the major endeavors of the player characters over the course of the last nine years of active play:

A Funerary Mystery: The campaign kicked off in 2015 with the characters assisting their clan in attending to the affairs of a dead elder, who'd died at an advanced age. In the process of doing so, they uncovered evidence of a plot by foreign agents provocateurs to destabilize a border region of Tsolyánu.An Extended Trip Abroad: The House of Worms clan sent the characters to neighboring Salarvyá to tend to the clan's business interests there. After a few weeks seeing the local sights and exploring places of interest, a magical mishap propelled them thousands of miles away to the northern land of Yán Kór. The journey back to Tsolyánu took more than six months, during which time they met new friends, made new enemies, and tangled with the dreaded Ssú for the first time.Tsolyáni Politics: Returning home, they accidentally interfered with the plans of an imperial prince (Mridóbu). In return for his forgiveness, they pledged their future assistance to him, no questions asked.Cult Investigations: In their home city of Sokátis, the characters looked into the disappearances and strange behavior of important local people, leading them to discover evidence of a secretive cult dedicated to one of the Pariah Gods, perhaps the fearsome Goddess of the Pale Bone herself. In the process, they come to realize one of the player characters was not who seemed to be but rather a magical copy employed by the cult. They rescued the real character and disrupted some of the cult's activities.A Foreign Posting: Prince Mridóbu called in his favor and sent the characters to the far-off Tsolyáni colony of Linyaró to act as its administration. This posting is a "reward" for the characters' proven ability to disrupt hidden plots. Mridóbu believes something suspicious is afoot in the colony and the characters have the skills necessary to reveal it (plus he wants them far away from Tsolyánu, lest they cause more trouble for him there). A Journey by Sea, Land, and Sea Again: The characters then spend many months traveling by water before reaching the plague ravaged land of Livyánu, where they disembarked. They then trekked across its length to catch another sea vessel for the final legal of their trip to Linyaró on the coast of the Achgé Peninsula.Showing the Flag: Having reached Linyaró, the characters must establish control over the colony and deal with several scheming factions, at least one of which was probably behind the murder of the previous governor. This list represents only the first two years of play – and I've left out plenty of smaller adventures. Over the next nine years, the characters traversed the length and breadth of the Achgé Peninsula, dealt with the rulers of several Naqsái city-states, explored a huge ruined city, tangled with the Temple of Ksárul, battled the Hokún, treated with advanced AIs, visited an alternate Tékumel, traveled to several of the Planes Beyond, prevented the Shunned Ones from altering the atmosphere of the planet, and dealt with one of their companions' deaths, among other things. That's not even taking into account all the social interactions and alliances they've formed, often through marriage, in the course of play. After nearly a decade, there are simply too many adventures, expeditions, and escapades to recount, even if I were minded to share them all with you here.What I hope is clear, though, is that campaign events largely have not threatened the world as a whole. I dislike dramatic hyperbole. I feel that threatening to end the world makes for boring roleplaying sessions, not to mention making it difficult to continue playing after the supposedly world-ending danger is inevitably averted. The referee cannot keep upping the stakes and expect players to continue being interested in the campaign. After the first few times Armageddon is put on hold, players quickly come to realize that there are no stakes. This is why the characters – both player and non-player – generally drive the action: it keeps the players invested. They know that their actions have consequences and that events unfold logically from their choices. I doubt the campaign would still be ongoing if I'd opted for any other approach.

May 28, 2024

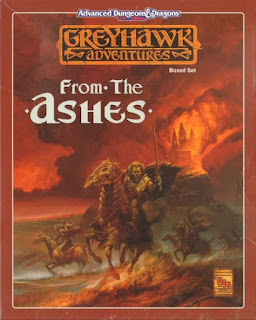

Retrospective: From the Ashes

At the end of last week's Retrospective on

Greyhawk Wars

, I promised I'd devote my next post in this series to taking a closer look at TSR's early 1990s attempt to reinvent Gary Gygax's World of Greyhawk setting for AD&D Second Edition. While Greyhawk Wars kicked off that reinvention by plunging the Flanaess into a fantastical "world war," the heavy lifting of teasing out just what that war actually meant for the venerable campaign milieu fell to another product, From the Ashes, released in 1992 and written by Carl Sargent.

At the end of last week's Retrospective on

Greyhawk Wars

, I promised I'd devote my next post in this series to taking a closer look at TSR's early 1990s attempt to reinvent Gary Gygax's World of Greyhawk setting for AD&D Second Edition. While Greyhawk Wars kicked off that reinvention by plunging the Flanaess into a fantastical "world war," the heavy lifting of teasing out just what that war actually meant for the venerable campaign milieu fell to another product, From the Ashes, released in 1992 and written by Carl Sargent. Like the 1983 revision of the original World of Greyhawk folio, From the Ashes comes in the form of a boxed set containing a pair of softcover books (both 96 pages in length this time) and an updated version of Darlene's incomparable maps. However, it also contains an additional map (depicting the regions around the City of Greyhawk), as well as new Monstrous Compendium sheets, and twenty cardstock reference sheets. All in all, it's impressively jam-packed in the way that TSR boxed sets almost always were during the late '80s and early '90s. Depending on one's preference, that's either a good thing or a bad thing – but we'll tackle that question soon enough.

The first of the two 96-page books is the Atlas of the Flanaess. This is largely a rewrite of material found in the 1983 boxed set, updated to take into account the consequences of the Greyhawk Wars on the setting. There's an overview of the setting's history, with an emphasis on recent events. Then, we're given looks at the peoples of the Flanaess, their lands, important geographical features, and the gods (or "powers," according to 2e's bowdlerized terminology) and their priesthoods. The Atlas also includes sections on "Places of Mystery" and "Tales of the Year of Peace." The first are unusual, often magical, locales that hold special interest to adventures, similar to those presented in the earlier Greyhawk Adventures. Meanwhile, the latter are adventure seeds for the Dungeon Master to flesh out.

The second 96-page book is the Campaign Book. This volume consists of entirely new information, focused primarily on the City of Greyhawk, its surrounding lands, and its important NPCs. During the Greyhawk Wars, the City suffered much damage. Now, it is being rebuilt and serves as neutral ground between all the previously warring kingdoms and factions. This turns the City into a Casablanca-esque den of espionage and intrigue, as well as a convenient home base for adventurers trying to make their way in this changed Flanaess. There is a ton of information here, providing the DM with lots of fodder for an ongoing campaign. I'd wager that the Campaign Book alone probably contains more new details about the World of Greyhawk setting than had been revealed in many years, perhaps ever.

And that is one of the aspects of From the Ashes that makes it controversial in some quarters – the detail. For many, the appeal of the World of Greyhawk has always been its sketchy, open-ended nature. The original folio was, at best, an outline of a setting, one each referee could use as a foundation on which to build his own version of Greyhawk. While the later boxed set included more details, most notably about the gods, it was still quite vague in its descriptions about many aspects of the setting. This aspect of the World of Greyhawk made it a good choice for DMs who weren't quite ready to create their own settings from whole cloth but who also still wanted lots of freedom to introduce his own ideas.

From the Ashes changed this aspect of the setting, bringing more in line with TSR's growing library of AD&D campaign settings, many of which came to be exhaustively detailed. This is precisely what started to happen with Greyhawk, too. Over the course of the next few years, From the Ashes was followed up by a number of lengthy expansion modules that filled in other parts of the Flanaess. In addition, some of these modules further advanced the unfolding "story" of From the Ashes in a way that was very much in keeping with the growing interest in "metaplot" that suffused RPGs during the 1990s, most famously in White Wolf's World of Darkness games, but by no means limited to them.

The second aspect of From Ashes that makes it controversial is its perceived changes to the tone of the Greyhawk setting. As originally presented, the World of Greyhawk had a tone that I can only describe as wargaming-meets-sword-and-sorcery. On the macro-level, it seems apparent to me that Gary Gygax liked the idea of a crazy quilt of rival nations, each jockeying for land, influence, and power – the perfect backdrop for a medieval wargames campaign of the sort that gave birth to Dungeons & Dragons in the first place. However, on the personal level, Greyhawk seems very much indebted to pulp fantasy of the Robert E. Howard and Fritz Leiber variety, as evidenced by his own forays into fiction writing.

The tone of From the Ashes and its expansions focused too much, I think, on the former at the expense of the latter. The battles of kingdoms and machinations of powerful NPCs overshadowed everything else. The Flanaess became their world; your player characters were just living in it. This is a problem that came to afflict the Forgotten Realms as well, much to the chagrin of its own creator. It was certainly a poor choice for Greyhawk, which, as I said, had long been more of a blank canvas on which the Dungeon Master could paint whatever he wanted while taking inspiration from the loose ideas Gygax provided. From the Ashes transformed the setting into a much more detailed place, driven by NPCs and Big Events dictated by TSR's desire to sell more product.

My own feelings about From the Ashes are decidedly mixed. I recognize and largely agree with many of the criticisms of the boxed set, especially regarding its introduction of a metaplot into Greyhawk, At the same time, Carl Sargent put a lot of solid work into this and many of the details he provided are eminently gameable, from small dungeons and adventure locales to interesting factions and conflicts. It's true that the Big Picture of the post-Wars setting takes precedence, but there's still some room for smaller, more personal scenarios and Sargent put effort into highlighting some of them. From the Ashes isn't, therefore, a complete disaster, but neither is it an unqualified success. Instead, it's a well-presented muddle and I think both positive and negative feelings toward are justified, depending on one's preferences.

Anonymous

About a month and a half ago, I opened up the comments section of the blog to readers without Google accounts, including those who wished to post anonymously. I'm pleased to say that this has actually been a boon to the blog, since most posts now receive many more comments – a lot more in some cases. That's good news overall, since I've wanted to foster discussion about the topics about which I write here, especially when my own opinion on a given matter might differ from conventional wisdom.

One of the drawbacks of allowing anonymous posts is that, in many the comments to many posts, it can be quite difficult differentiating one anonymous poster from another. That can lead to confusion and misunderstanding, something to which online written discussion is already quite prone. I don't know that there's a solution to this, but, if anyone has any ideas, I'd love to hear them. As I said, I'm mostly very happy with the reinvigorated comments sections, so I don't want to do anything that might stifle that. I simply wish it were easy to keep track of which anonymous poster was which.

May 27, 2024

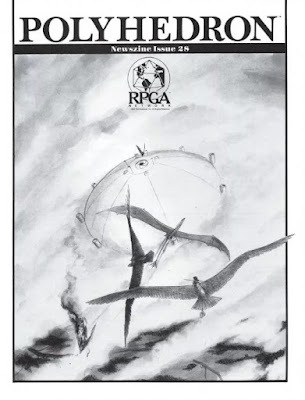

Polyhedron: Issue #28

Issue #28 of Polyhedron (March 1986) features yet another cover by Roger Raupp, who, as I've remarked previously, seems to have been TSR's go-to guy for on-demand artwork in the mid to late 1980s. I never minded, because I liked his style, which I felt struck a nice balance between the cleanliness of Larry Elmore and the grubbiness of Jim Holloway while still remaining firmly within the realm of "fantastic realism." Given how often his illustrations appear during this period, I suspect Raupp must have worked quickly – a great virtue for an artist employed in the gaming industry.

Issue #28 of Polyhedron (March 1986) features yet another cover by Roger Raupp, who, as I've remarked previously, seems to have been TSR's go-to guy for on-demand artwork in the mid to late 1980s. I never minded, because I liked his style, which I felt struck a nice balance between the cleanliness of Larry Elmore and the grubbiness of Jim Holloway while still remaining firmly within the realm of "fantastic realism." Given how often his illustrations appear during this period, I suspect Raupp must have worked quickly – a great virtue for an artist employed in the gaming industry."Notes from HQ" contains an update on "the City Project" first announced in issue #25. Editor Penny Petticord mentions that "the legal aspects of the project have not yet been completely resolved," but does not elaborate on precisely what this means. She might be alluding to the assignment of copyrights, given that this project will include submissions from many outside sources, though there are other possible explanations. Interestingly, Petticord makes no mention of the placement of the setting within the World of Greyhawk or any other setting. Gary Gygax's imminent departure from TSR might explain this omission. In any event, the project would eventually be shifted to the Forgotten Realms when Ed Greenwood's campaign setting became the default setting of AD&D in 1987.

"Adventure Among the Clouds" by Jeff Martin is an AD&D article that tackles the subject of cloud islands – floating "land" masses that can serve as adventure locales. The existence of such islands was first confirmed in the Monster Manual's description of cloud giants and elaborated upon further in module UK7, Dark Clouds Gather. In this article, Martin describes the origin, composition, and inhabitants of cloud islands, along with notes on how these magical places affect spells and magic items. His overall approach reminds me a lot of a condensed version of what Roger E. Moore pioneered with his "The Astral Plane" article in Dragon #67 (November 1982), though, sadly, less interesting. Cloud islands are potentially fascinating places and very much in keeping with AD&D-style fantasy, but Martin, in my opinion, treats them in a rather mundane way. It's a shame.

Back in the day, Frank Mentzer was a machine when it came to penning RPGA AD&D tournament adventures. This issue includes another one, "The Great Bugbear Hunt," intended for characters of levels 5–7. The set-up is that, while out in the wilderness, a passing band of bugbears slew the horses of a party of adventurers and stole all the items in the saddlebags. Among them is a magic-user's spellbook. Naturally horrified by this turn of events, he enlists the aid of others to venture back into the wilderness in an attempt to find the bugbears and retrieve it. The scenario is, in effect, a scavenger hunt in a wilderness filled with monsters and other obstacles. This one looks like a lot of fun, with plenty of varied and challenging encounters.

"The Specialist Mage" by Jon Pickens introduces a new idea for use in AD&D games: the specialist mage. Bear in mind, this is 1986, three years before the release of Second Edition, which formalized specialist mages as an option for player character magic-users. Here, the idea is presented as being for NPCs only – a common dodge employed in the pages of Dragon to justify its articles on new classes without running afoul of TSR dicta about "no new character classes." Pickens's version of the specialist mage receives XP bonuses if he employs more spells of his chosen specialty, in addition to having access to unique spells unavailable to non-specialists. In this issue, he presents numerous new necromancy spells, though they were intended only for use by "an NPC villain." Where have I heard that before?

Michael Przytarski's "Fletcher's Corner" is focused on the creation and judging of tournament scenarios, a topic that I must confess holds little interest for me. That he is given three pages to elucidate his thoughts on the topic makes it even less compelling somehow. Of course, this is the official newszine of the Role Playing Game Association, which sponsored innumerable tournaments at GenCon and elsewhere, so this is exactly the kind of content that should be here. That it holds no interest for me says more about my weirdness than it does about the article. Alas, I'm the one writing this post.

In terms of the number of articles, issue #28 has among the fewest in some time. That's probably due to the fact that "The Great Bugbear Hunt" adventure takes up half of the issue's 32 pages. Likewise, all the remaining articles, with the exception of "Notes from HQ," are at least three pages long. I probably wouldn't have even commented on this if any of them had any of them stood out as notable in some way. Instead, they're mostly fine if unexceptional, so I took greater note of how few there were than I otherwise might have.

Sadly, the next issue is the April Fool's Day issue, so I don't think it'll prove much better ...

How Do You a Problem Like Kirktá? (Part II)

Since readers seem to have been genuinely interested in this particular aspect of my ongoing House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign, here's an update on the situation I first mentioned earlier this month.

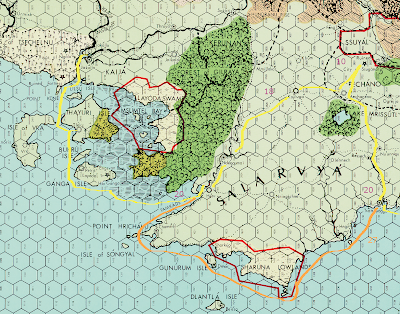

Presently, the player characters are on an extended expedition to explore ancient ruins once inhabited by an intelligent – and magically powerful – non-human species known as the Mihálli. These ruins are far from the characters' native Tsolyánu. The quickest paths to the ruins run through the neighboring realm of Salarvyá, which enjoys a generally peaceful relationship (aside from some border skirmishes from time to time). Early in the campaign, nearly nine years ago, the characters spent several months in Salarvyá on a mission for their clan, so the kingdom is familiar to them and many of the characters speak Salarvyáni.

Their present expedition is funded by Prince Rereshqála, one of several publicly declared heirs of the emperor of Tsolyánu. Rereshqála is given to magnificent displays of noblesse oblige, sponsoring works of art and scholarship. Because the Mihálli are so mysterious and poorly understood, it is hoped this expedition will uncover new information about them, including the recovery of artifacts associated with them. If successful, the expedition would bring glory and fame on those who undertook it – and to their noble patron as well.

In addition to providing the expedition with manpower and funds, Prince Rereshqála asked one other thing of the characters: to return a young Salarvyáni noblewoman to her family in the city of Koylugá. The young woman, Chgyár Dléru by name, is a member of Thirreqúmmu family who rules Koylugá. Indeed, her uncle, Kúrek Tiqónnu, is one of the seven most powerful men in all of Salarvyá and thus a candidate for the Ebon Throne upon the death of its present king. Salarvyá, you see, has an elective monarchy and, while the throne has long been held by members of the Chruggilléshmu family, in principle a candidate from any of the mighty feudal families might be elected instead.

Before entering Salarvyá, the characters had been warned that its political situation was growing increasingly fraught. The king is old and insane. Consequently, many of the great families were jockeying for position, so that, when he finally died, they could make their bid to rule. Likewise, the Temple of Shiringgáyi, the primary deity of Salarvyá, were flexing its own muscles by encouraging zealots to attack foreigners and rail against their supposedly pernicious influence. There were also reports of a large-scale military conflict between internal factions of the kingdom.

A map depicting the characters' possible paths through SalarvyáDespite all this, the characters journey through Salarvyá was largely uneventful until the night before they were scheduled to have an audience with Lord Kúrek in Koylugá. They had already successfully returned Lady Chgyár to her family and decided to spend the afternoon and evening exploring the city. After sunset, they visited the Night Market, an emporium of oddities, where they acquired a few useful and interesting trinkets. However, the Market was eventually disrupted by Shiringgáyi zealots. Rather than risk running afoul of local authorities, the characters fled back to their lodgings to wait out the night.

A map depicting the characters' possible paths through SalarvyáDespite all this, the characters journey through Salarvyá was largely uneventful until the night before they were scheduled to have an audience with Lord Kúrek in Koylugá. They had already successfully returned Lady Chgyár to her family and decided to spend the afternoon and evening exploring the city. After sunset, they visited the Night Market, an emporium of oddities, where they acquired a few useful and interesting trinkets. However, the Market was eventually disrupted by Shiringgáyi zealots. Rather than risk running afoul of local authorities, the characters fled back to their lodgings to wait out the night.That's when they received a message from Lord Kúrek confirming the details of their meeting with him the next morning. In addition to the expected subjects, the message also included a lengthy legal document detailing the terms and conditions of the upcoming marriage between Lady Chgyár and Kirktá! Needless to say, this caught everyone off-guard, Kirktá most of all, though he did spend some time trying to figure if perhaps had inadvertently done something while in Chgyár's presence that might have been misinterpreted as an offer of marriage. Even more alarmingly, the marriage contract referred to Kirktá by the name Kirktá Tlakotáni, Tlakotáni being the name of the emperor's clan. This made it clear that Lord Kúrek and his family knew of Kirktá's true lineage – but how? The characters had worked very hard to keep this information secret.

It's important to point out that Chgyár had originally been sent to Rereshqála by Lord Kúrek as a bride and, therefore, a token of friendship between a powerful faction within Salarvyá. However, Chgyár did not adapt well to life in Tsolyánu. She became so homesick that Rereshqála opted to send her back to her family rather than force her to remain in a foreign land. Consequently, the characters immediately theorized that this surprise marriage arrangement with Kirktá was intended to make up for the fact that she'd managed to let one imperial prince get away. Her family no doubt wished to be sure the same thing did not happen a second time. But, if so, how did anyone know Kirktá's secret? Further, how many more people might know? This was a potentially serious problem.

This post is already much longer than I intended it to be, so I'll end it here, with the promise to follow it up with another later this week. Suffice it to say that the characters spent a lot of time pondering how to proceed now that Kirktá's princely status had seemingly been uncovered by someone who intended to use it for unknown ends. Almost from its beginning in 2015, the House of Worms campaign has been fueled by the characters' interaction with the society, culture, politics, and religion of the world around them. They have goals and dreams of their own and they pursue them with gusto. Of course, the same is true of the non-player characters of the setting. The interactions between these two competing forces is something I continue to enjoy and that I hope will carry on well into the future.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers