James Maliszewski's Blog, page 55

May 27, 2024

How Do You a Problem Like Kirktá? (Part II)

Since readers seem to have been genuinely interested in this particular aspect of my ongoing House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign, here's an update on the situation I first mentioned earlier this month.

Presently, the player characters are on an extended expedition to explore ancient ruins once inhabited by an intelligent – and magically powerful – non-human species known as the Mihálli. These ruins are far from the characters' native Tsolyánu. The quickest paths to the ruins run through the neighboring realm of Salarvyá, which enjoys a generally peaceful relationship (aside from some border skirmishes from time to time). Early in the campaign, nearly nine years ago, the characters spent several months in Salarvyá on a mission for their clan, so the kingdom is familiar to them and many of the characters speak Salarvyáni.

Their present expedition is funded by Prince Rereshqála, one of several publicly declared heirs of the emperor of Tsolyánu. Rereshqála is given to magnificent displays of noblesse oblige, sponsoring works of art and scholarship. Because the Mihálli are so mysterious and poorly understood, it is hoped this expedition will uncover new information about them, including the recovery of artifacts associated with them. If successful, the expedition would bring glory and fame on those who undertook it – and to their noble patron as well.

In addition to providing the expedition with manpower and funds, Prince Rereshqála asked one other thing of the characters: to return a young Salarvyáni noblewoman to her family in the city of Koylugá. The young woman, Chgyár Dléru by name, is a member of Thirreqúmmu family who rules Koylugá. Indeed, her uncle, Kúrek Tiqónnu, is one of the seven most powerful men in all of Salarvyá and thus a candidate for the Ebon Throne upon the death of its present king. Salarvyá, you see, has an elective monarchy and, while the throne has long been held by members of the Chruggilléshmu family, in principle a candidate from any of the mighty feudal families might be elected instead.

Before entering Salarvyá, the characters had been warned that its political situation was growing increasingly fraught. The king is old and insane. Consequently, many of the great families were jockeying for position, so that, when he finally died, they could make their bid to rule. Likewise, the Temple of Shiringgáyi, the primary deity of Salarvyá, were flexing its own muscles by encouraging zealots to attack foreigners and rail against their supposedly pernicious influence. There were also reports of a large-scale military conflict between internal factions of the kingdom.

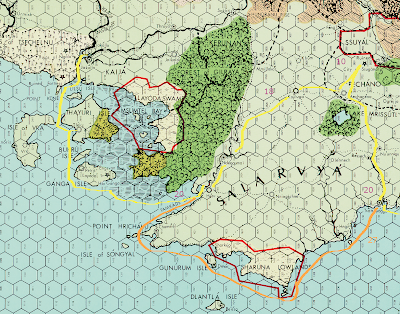

A map depicting the characters' possible paths through SalarvyáDespite all this, the characters journey through Salarvyá was largely uneventful until the night before they were scheduled to have an audience with Lord Kúrek in Koylugá. They had already successfully returned Lady Chgyár to her family and decided to spend the afternoon and evening exploring the city. After sunset, they visited the Night Market, an emporium of oddities, where they acquired a few useful and interesting trinkets. However, the Market was eventually disrupted by Shiringgáyi zealots. Rather than risk running afoul of local authorities, the characters fled back to their lodgings to wait out the night.

A map depicting the characters' possible paths through SalarvyáDespite all this, the characters journey through Salarvyá was largely uneventful until the night before they were scheduled to have an audience with Lord Kúrek in Koylugá. They had already successfully returned Lady Chgyár to her family and decided to spend the afternoon and evening exploring the city. After sunset, they visited the Night Market, an emporium of oddities, where they acquired a few useful and interesting trinkets. However, the Market was eventually disrupted by Shiringgáyi zealots. Rather than risk running afoul of local authorities, the characters fled back to their lodgings to wait out the night.That's when they received a message from Lord Kúrek confirming the details of their meeting with him the next morning. In addition to the expected subjects, the message also included a lengthy legal document detailing the terms and conditions of the upcoming marriage between Lady Chgyár and Kirktá! Needless to say, this caught everyone off-guard, Kirktá most of all, though he did spend some time trying to figure if perhaps had inadvertently done something while in Chgyár's presence that might have been misinterpreted as an offer of marriage. Even more alarmingly, the marriage contract referred to Kirktá by the name Kirktá Tlakotáni, Tlakotáni being the name of the emperor's clan. This made it clear that Lord Kúrek and his family knew of Kirktá's true lineage – but how? The characters had worked very hard to keep this information secret.

It's important to point out that Chgyár had originally been sent to Rereshqála by Lord Kúrek as a bride and, therefore, a token of friendship between a powerful faction within Salarvyá. However, Chgyár did not adapt well to life in Tsolyánu. She became so homesick that Rereshqála opted to send her back to her family rather than force her to remain in a foreign land. Consequently, the characters immediately theorized that this surprise marriage arrangement with Kirktá was intended to make up for the fact that she'd managed to let one imperial prince get away. Her family no doubt wished to be sure the same thing did not happen a second time. But, if so, how did anyone know Kirktá's secret? Further, how many more people might know? This was a potentially serious problem.

This post is already much longer than I intended it to be, so I'll end it here, with the promise to follow it up with another later this week. Suffice it to say that the characters spent a lot of time pondering how to proceed now that Kirktá's princely status had seemingly been uncovered by someone who intended to use it for unknown ends. Almost from its beginning in 2015, the House of Worms campaign has been fueled by the characters' interaction with the society, culture, politics, and religion of the world around them. They have goals and dreams of their own and they pursue them with gusto. Of course, the same is true of the non-player characters of the setting. The interactions between these two competing forces is something I continue to enjoy and that I hope will carry on well into the future.

May 26, 2024

The Cost of Power

One of the many ways that fantasy roleplaying games differ from their pulp fantasy inspirations concerns the use of magic. With comparatively few exceptions, pulp fantasy depicts magic as, at best, wild and unpredictable and, at worst, as outright diabolical. RPGs, meanwhile, treat magic almost as a form of technology, an instrument that is neither inherently good nor bad and that, if used with appropriate training, rarely if ever presents any danger to its user.

One of the many ways that fantasy roleplaying games differ from their pulp fantasy inspirations concerns the use of magic. With comparatively few exceptions, pulp fantasy depicts magic as, at best, wild and unpredictable and, at worst, as outright diabolical. RPGs, meanwhile, treat magic almost as a form of technology, an instrument that is neither inherently good nor bad and that, if used with appropriate training, rarely if ever presents any danger to its user. The most obvious exceptions that come to my mind are Chaosium's Call of Cthulhu and Stormbringer , both of which explicitly caution against the use of magic by characters, precisely because of its inherent danger. A more recent exception is Goodman Games' Dungeon Crawl Classics Role-Playing Game. Of course, two of the aforementioned RPGs are based directly on foundational works of pulp fantasy, while the other self-avowedly looks to pulp literature for its inspiration. There may be a few other contrary examples here and there, but, for the most part, fantasy roleplaying games have followed the lead of Dungeons & Dragons in treating magic purely instrumentally – differing from safe, reliable technology only in esthetics.

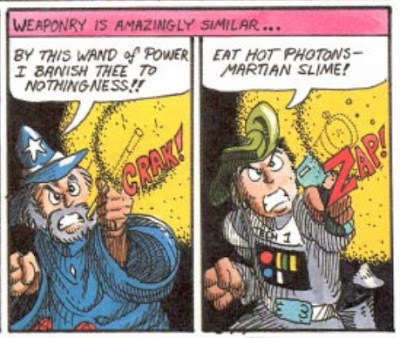

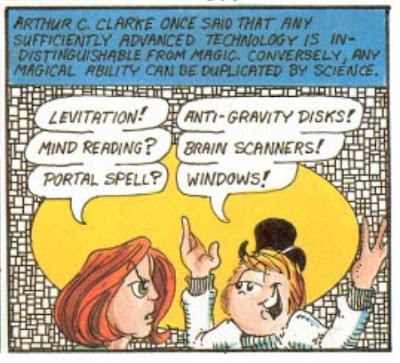

Back in Dragon #65 (September 1982), Phil Foglio lampooned this to good effect in his What's New with Phil & Dixie. In this particular strip, Phil claims that the differences between medieval and science fiction RPGs can be summed up in one word: none. When Dixie objects, he then provides her with a series of examples to prove his point that, while tendentious, nevertheless contain a ring of truth. The comic even invokes Clarke's Third Law for additional support.

Back in Dragon #65 (September 1982), Phil Foglio lampooned this to good effect in his What's New with Phil & Dixie. In this particular strip, Phil claims that the differences between medieval and science fiction RPGs can be summed up in one word: none. When Dixie objects, he then provides her with a series of examples to prove his point that, while tendentious, nevertheless contain a ring of truth. The comic even invokes Clarke's Third Law for additional support.

If you look at the history of the hobby over the last half-century, the paradigm of magic-as-technology has clearly been the most common. Whether that's because D&D set the pattern by adopting it or because it's just a simpler and perhaps even more fun way to handle magic, I can't say. Still, as a fan of dangerous magic, it's hard not to be a little saddened by how rarely it's been employed in RPGs over the decades. Perhaps it's time for a change ...

If you look at the history of the hobby over the last half-century, the paradigm of magic-as-technology has clearly been the most common. Whether that's because D&D set the pattern by adopting it or because it's just a simpler and perhaps even more fun way to handle magic, I can't say. Still, as a fan of dangerous magic, it's hard not to be a little saddened by how rarely it's been employed in RPGs over the decades. Perhaps it's time for a change ...

May 23, 2024

Retrospective: Greyhawk Wars

I've never been much of a wargamer (take a drink). Despite that, I've always been interested in wargaming, particularly the hex-and-chit variety epitomized by Avalon Hill. Over the years, I've dabbled in wargames, such as my recent flirtation with the COIN series published by GMT, but I've never really committed to them in the way that many of my friends have done. I thus have a minor inferiority complex about this, feeling that my gaming "education" is somehow deficient because I haven't played wargames as often or as widely as my peers.

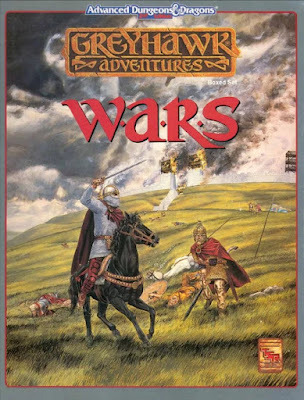

I've never been much of a wargamer (take a drink). Despite that, I've always been interested in wargaming, particularly the hex-and-chit variety epitomized by Avalon Hill. Over the years, I've dabbled in wargames, such as my recent flirtation with the COIN series published by GMT, but I've never really committed to them in the way that many of my friends have done. I thus have a minor inferiority complex about this, feeling that my gaming "education" is somehow deficient because I haven't played wargames as often or as widely as my peers.So, when TSR released a board wargame set in Gary Gygax's World of Greyhawk setting in 1991, I took immediate notice of it. This was my chance to get in some much needed wargaming experience. Alas, things didn't quite go as planned on this score, but I'll get to that soon enough. For the moment, let's focus on the matter of the game's title. According to the box cover, one could be forgiven for thinking it's called Greyhawk Adventures: Wars. However, the text of the rulebook repeatedly calls it simply Greyhawk Wars, which is how I've always referred to it, though some online spaces (like BoardGameGeek) favors the longer, more ponderous title.

In addition to the possible confusion over the title, it's also worth noting that, despite being a wargame, Greyhawk Wars was released under the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition banner. This is in spite of the fact that it contains no roleplaying content whatsoever, not even the thin gruel provided by Dragons of Glory , another TSR strategic-level wargame set within a D&D campaign world. Of course, TSR had long been notorious about slapping the (A)D&D logo on just about everything, in an effort to build and expand its "brand." Compared to, say, wind-up toys or sunglasses, this particular bit of brand building was pretty innocuous and indeed could be justified in that it was intended to be the lead-in to a relaunch of the World of Greyhawk setting.

Though Gygax departed TSR for good by 1986, the company retained control of Greyhawk. Throughout the late 1980s, there were a handful of Greyhawk products released, most notably Greyhawk Adventures, but none of them, in my opinion, did a good job of carrying on the flavor and tone set by Gygax's original. If anything, they blandified the setting, reducing it to the worst kind of vanilla fantasy. Unsurprisingly, the setting's popularity – and, therefore, sales – declined, especially when compared to TSR's other two AD&D settings: Krynn and the Forgotten Realms.

TSR probably recognized this fact, which is why, starting in the early '90s, the company attempted to better differentiate the World of Greyhawk in the hopes that it'd be more appealing to AD&D players. The first step in doing so was Greyhawk Wars. The wargame, designed by David "Zeb" Cook, concerns a massive war that engulfs the peoples and kingdoms of the Flanaess, one whose results upend the status quo presented in previous World of Greyhawk products. Whatever my personal feelings about the end result, it's hard not to admire the boldness of this approach. For years beforehand, Gary Gygax, in periodic Greyhawk updates published in Dragon, had been hinting at the possibility of such a large-scale "world war," but he never pulled the trigger on the idea, probably because he intended Oerth to be an open-ended "steady state" setting each Dungeon Master could customize according to his own desires.

Greyhawk Wars takes a very different approach. Instead of leaving the World of Greyhawk perpetually teetering on the edge of grand events, Cook opts to topple the whole structure, throwing long established peoples, places, and situations into chaos. At the end of the battles depicted in the wargame, a new order is established across the Flanaess, one where the forces of Good are battered, beaten, and on the defensive, while Evil, as represented by the Empire of Iuz, the Scarlet Brotherhood, and the successor states of the Great Kingdom is on the rise. The result is something that's definitely different from the original World of Greyhawk. Whether it's better is another matter.

As tabletop wargames go, Greyhawk Wars occupies a middle ground between being simple enough a newcomer can easily pick it up and so complex that only a hardened veteran of Third Reich could ever play it. The game rules are relatively short – only 8 pages – and straightforward. While there are lots of counters (representing military units), there are no hexes. Instead, the map of the Flanaess into movement "areas" of varying size, based to some extent on terrain. Also included in the game are a number of cards, some of which represent random events and treasures that can be used to augment the abilities of military units. Named NPCs (called "Heroes") play a role in the game, too, which lends it a slight roleplaying flair, though, for the most part, this is still very much a standard wargame.

Greyhawk Wars is intended for 2 to 6 players, depending on the scenario, each with its own victory conditions. These conditions, though, are solely for gaming purposes and have no bearing on the canonical versions of these events, much in the way that a Confederate player in a wargame about the American Civil War can emerge victorious, contrary to history. The 32-page Adventurer's Book lays out the "true" conclusion of the Greyhawk Wars, the one I described above, with Evil ascendant and Good on the defensive. This is in contrast to the earlier Red Arrow, Black Shield module, which, while assuming a particular outcome for its world war, nevertheless considers the possibility of other outcomes and how they might affect ongoing campaigns. Greyhawk Wars allows for no such possibility and all subsequent Greyhawk products would follow the canonical version of history detailed in the Adventurer's Book.

As I alluded to at the start of this post, my own experiences with Greyhawk Wars weren't great. That's not a fault of the game, which is fine, if unexceptional. Rather, I had difficulty in finding others interested in taking the time to play any of its scenarios. Between setting up and playing, most took 3 hours or more – a short time compared to many wargames, I know – and that limited my pool of potential players. As a result, I don't think I ever played Greyhawk Wars more than a half-dozen times and rarely to conclusion. My perpetual quest for more wargaming knowledge and experience was thwarted once again.

All that said, I can't help but find Greyhawk Wars a fascinating window into the last decade of TSR's existence. The mere fact that the company published something approximating a classic hex-and-chit wargame set in Greyhawk is remarkable in its own right. That it was also the first part of a larger plan to reboot Gary Gygax's campaign setting into something they hoped would be more attractive to fantasy roleplayers in the 1990s is just as remarkable. I can't speak much about the success of the former, since, as I said, I didn't get the chance to play it much. As to the latter, that's the subject of next week's Retrospective post, so stay tuned.

May 21, 2024

Polyhedron: Issue #27

Issue #27 of Polyhedron (January 1986) features yet another cover by Roger Raupp, this time depicting a clan of dwarves. Raupp was a very prominent artist in the pages of both Polyhedron and Dragon during the second half of the 1980s – so prominent that, for me at least, his illustrations strongly define the look of that era. I also remember Raupp's work on many of the later Avalon Hill RuneQuest books, which, as I understand it, are very well regarded among Glorantha fans. Leaving aside the forgettable "Notes from HQ," the issue properly kicks off with "Dominion" by Jon Pickens, which introduces a new type of spell for use by AD&D magic-users. Unlike previous collections of new spells by Pickens, this one looks not to magic items for inspiration but rather psionics. All of the dominion spells concern "controlling the victim's voluntary muscles and sensory linkages." This is not mind control but rather bodily control of another being (with the senses being considered part of the body). It's an interesting approach and ultimately, I think, a better one than AD&D's psionics system, which, in addition to being mechanically dubious, didn't really mesh with the overall feel of the game.

Issue #27 of Polyhedron (January 1986) features yet another cover by Roger Raupp, this time depicting a clan of dwarves. Raupp was a very prominent artist in the pages of both Polyhedron and Dragon during the second half of the 1980s – so prominent that, for me at least, his illustrations strongly define the look of that era. I also remember Raupp's work on many of the later Avalon Hill RuneQuest books, which, as I understand it, are very well regarded among Glorantha fans. Leaving aside the forgettable "Notes from HQ," the issue properly kicks off with "Dominion" by Jon Pickens, which introduces a new type of spell for use by AD&D magic-users. Unlike previous collections of new spells by Pickens, this one looks not to magic items for inspiration but rather psionics. All of the dominion spells concern "controlling the victim's voluntary muscles and sensory linkages." This is not mind control but rather bodily control of another being (with the senses being considered part of the body). It's an interesting approach and ultimately, I think, a better one than AD&D's psionics system, which, in addition to being mechanically dubious, didn't really mesh with the overall feel of the game."The Thorinson Clan" by Skip Olsen presents five dwarves, related by blood and marriage, from his Norse mythology-inspired AD&D campaign. These are the characters Roger Raupp portrayed on the cover. They're an interesting bunch and I must confess I appreciate the fact that Olsen's campaign is multi-generational, a style of play I think is under-appreciated (and one of the reasons I think so highly of Pendragon ). Almost certainly coincidentally, this issue's installment of Errol Farstad's "The Critical Hit" offers a very positive review of Pendragon, which he calls "the stuff of which legends are made." Needless to say, I agree with his assessment.

Next up is "She-Rampage" by Susan Lawson and Tom Robertson, a scenario for use with Marvel Super Heroes. As you might guess based on its title, the scenario involved She-Hulk but also a number of other female Marvel characters, like Valkyrie, Spider-Woman, Thundra, and Tigra. There's also an original character, Lucky Penny, who's based on the Polyhedron's editor, Penny Petticord. The background to the adventure is rather convoluted and involves alternate Earths where one sex dominates the others. The male-dominated Earth, Machus, has learned of the existence of our Earth and sees the existence of super-powered women as a potential threat to be eliminated. This they attempt to do by traveling to our world and then – I am not making this up – releasing doctored photos and scurrilous stories in the pages of "a girlie magazine known as Pander." Naturally, the superheroines take exception to this and it's clobberin' time. I have no words.

Michael Przytarski's "Fletcher's Corner" looks at "problem players." More specifically, he's interested in two different types of players who can cause problems for the referee. The first is the "Sierra Club Player," who's memorized all the rulebooks and uses his knowledge to overcome every obstacle the referee sets before him. The second is the "Multi-Class Player," whose experience is so wide that he tells other players the best way to play their class. In each case, Pryztarski offers some advice on how best to handle these players. Like most articles of this sort, it's hard to judge how good his advice would have been at the time, because most of what he says is now commonsense and has been for a long time.

"Alignment Theory" by Robert B. DesJardins is yet another attempt to make sense of AD&D's alignment. Like all such attempts, it's fine to the extent that you're willing to accept its premises. DesJardins argues that "law versus chaos" is a question of politics, while "good versus evil" is a question of heart (or morality). He makes this distinction in order to fight against the supposed notion that some players believe Lawful Good is more good than Chaotic Good – in short equating "law" with "good" and "chaos" with "evil." Was this a common belief then or now? I suppose it's possible players who entered the hobby through Dungeons & Dragons might have carried with them echoes of its threefold alignment system, but, even so, how common was it? I guess I long ago tired of alignment discussion, so it's difficult for me to care much about articles like this.

This month, "Dispel Confusion" focuses solely on rules and other questions about Star Frontiers , which surprised me. Meanwhile, "Gamma Mars: The Attack" by James M. Ward offers up a dozen new mutants to be used in conjunction with the "Gamma Mars" article from last issue. Most of these mutants are mutated Earth insects, but one represents the original Martian race, whose members have been lying beneath the planet's surface in wait for the right moment to strike against human colonists to the Red Planet. I find it notable that Ward was long interested in introducing extra-terrestrial beings into his post-apocalyptic settings, whether Gamma World or Metamorphosis Alpha. I wonder why it was an idea to which he returned so often?

As you can probably tell by this post, my enthusiasm for re-reading Polyhedron is waning. I'm very close to the end of the issues I owned in my youth, so I may simply be anticipating the conclusion of this series. On the other hand, I also think there's a certain tiredness to the newszine itself. The content has never been as uniformly good as that of Dragon and it's become even more variable as it has depended more and more on submissions by RPGA members, few of which are as polished or imaginative as those to be found elsewhere. The end result is a 'zine that's sometimes a bit of a chore to read, never mind comment about intelligently.

Ah well. I'll soldier on.

May 20, 2024

Ever Want to Be a Vampire?

As a kid, something I really enjoyed about reading Dragon magazine was looking over its advertisements. Most issues had a couple of dozen (or more), often from companies I'd never heard of offering products I'd never seen. In too many cases, the ads were vague to the point of being cryptic. Consider this one that I saw in issue #80 (December 1983):

What exactly is this advertisement for? Is Wizards World a roleplaying game or something else entirely? At the time, I had no way of knowing, since I wasn't willing to risk $10 (over $30 in today's inflated currency) on a whim. I wouldn't find out the truth until nearly three decades later, when Goblinoid Games acquired the rights to

Wizards' World

, making it available in both print and electronic forms.

What exactly is this advertisement for? Is Wizards World a roleplaying game or something else entirely? At the time, I had no way of knowing, since I wasn't willing to risk $10 (over $30 in today's inflated currency) on a whim. I wouldn't find out the truth until nearly three decades later, when Goblinoid Games acquired the rights to

Wizards' World

, making it available in both print and electronic forms. Wizards' World is nothing special. It's similar to many other independent RPGs produced at the time in being amateurish and derivative but nevertheless made with great enthusiasm. Still, I'm glad to have solved this particular mystery. Do any readers recall any other similarly enigmatic advertisements? If so, I'd be interested in knowing what they were.

May 19, 2024

Heretical Thoughts (Part II)

Was Third Edition Dungeons & Dragons really that bad?

Was Third Edition Dungeons & Dragons really that bad?I know that it has a poor reputation among fans of old school D&D, which is really to say, TSR D&D, but is that reputation deserved? Was it truly a bad edition of "the world's most popular tabletop roleplaying game," to borrow a phrase – or does it simply catch a lot of grief for things not directly related to it as a game?

To place my thoughts in a little more context, let me provide a little personal history. I played Dungeons & Dragons – mostly AD&D – more or less continuously from late 1979 till about 1996 or thereabouts. That's around the time TSR released the "Player's Option" series of books. By that point, I'd already begun to tire of AD&D and had started to spend more time playing other RPGs, but something about the "Player's Option" volumes really vexed me. They were, in my opinion, a step too far, contributing further to my growing sense that AD&D was bloated and directionless.

During the period between 1996 and 2000, I largely abandoned playing Dungeons & Dragons in any form, in favor of many other roleplaying games. Late in this period, I also began to make my first forays into professional writing. One of my earliest employers was Wizard World, publisher of the magazine InQuest Gamer. InQuest initially focused on collectible card games, but eventually expanded to cover games of all sorts, including RPGs.

Though I was a freelancer, I was often assigned articles that gave me access to people and materials that would otherwise have been hard to come by. In early 2000, for example, I was given a major assignment: write about the upcoming new edition of D&D. To help me with this, Wizards of the Coast sent me pre-release proofs of the 3e Player's Handbook. I spent several weeks reading the text and giving the rules a test drive with my gaming group.

Though I was a freelancer, I was often assigned articles that gave me access to people and materials that would otherwise have been hard to come by. In early 2000, for example, I was given a major assignment: write about the upcoming new edition of D&D. To help me with this, Wizards of the Coast sent me pre-release proofs of the 3e Player's Handbook. I spent several weeks reading the text and giving the rules a test drive with my gaming group. This was the first time I'd played any version of D&D in several years – and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Indeed, I enjoyed it so much that, after I'd written the article for InQuest, I kept playing a Frankenstein version of "3e" cobbled together from the proofs WotC sent me augmented by 2e books to fill in any gaps (like monsters and magic items). We continued playing in this fashion until all three of the 3e core rulebooks were released between August and October of that year.

Third Edition brought me back to playing Dungeons & Dragons after a long hiatus. For that reason alone, I find it difficult to bear any ill will toward the edition. Then, as now, I had qualms about certain aspects of its design – its emphasis on "system mastery," for instance – but the fact that it reminded me just how fun D&D could be is a huge point in its favor. 3e simultaneously felt fresh and vibrant while also remembering its roots. Unlike late Second Edition, which was, to put it charitably, a chaotic mess without any clear sense of what it was about, Third Edition proudly advertised itself as a "back to the dungeon" edition. This restored to D&D a much-needed focus.

Of course, this wasn't the only way that 3e remembered its roots. A careful reading of the text of its three rulebooks revealed just how much of its verbiage it shares with previous editions, particularly when it came to the descriptions of spells, monsters, and magic items. This might not seem like a big deal, but it would prove to be very important. That's because Third Edition was the first "open" edition of D&D, most of whose contents (via its System Reference Document, or SRD) were made freely available for use by other publishers through either the Open Game License (OGL) or the D20 System Trademark License (STL). For the first time ever, the publisher of Dungeons & Dragons was offering a royalty-free means to produce adventures, supplements – and even whole games – compatible with D&D.

Of course, this wasn't the only way that 3e remembered its roots. A careful reading of the text of its three rulebooks revealed just how much of its verbiage it shares with previous editions, particularly when it came to the descriptions of spells, monsters, and magic items. This might not seem like a big deal, but it would prove to be very important. That's because Third Edition was the first "open" edition of D&D, most of whose contents (via its System Reference Document, or SRD) were made freely available for use by other publishers through either the Open Game License (OGL) or the D20 System Trademark License (STL). For the first time ever, the publisher of Dungeons & Dragons was offering a royalty-free means to produce adventures, supplements – and even whole games – compatible with D&D.The SRD and OGL quickly proved themselves very important and not just to the plethora of game companies that sprang up like mushrooms overnight to support 3e. By opening up the mechanical and conceptual "guts" of Dungeons & Dragons, Wizards of the Coast inadvertently gave birth to the Old School Renaissance. As early as 2004, independent publishers were experimenting with using the SRD and OGL to create RPGs that resembled earlier editions of D&D. The rest, as they say, is history, with the OSR quickly becoming both a movement and a genre, not to mention a permanent part of the larger hobby.

Now, one might reasonably argue that neither of these qualities has anything to do with Third Edition as a game either. That's a defensible position, though I don't completely agree with it, as I'll soon explain. However, I think historical context is important here. After the mess that was late Second Edition, 3e was a surprisingly clear, rational, and accessible restatement of the classic RPG. Most of its major deviations from TSR era D&D, like ascending armor class or new saving throw categories, served good purposes, even if I am no longer wholly on board with many of them. Nevertheless, they worked and facilitated play that, in my experience anyway, was quite reminiscent of how we played D&D in the early to mid-1980s.

Now, one might reasonably argue that neither of these qualities has anything to do with Third Edition as a game either. That's a defensible position, though I don't completely agree with it, as I'll soon explain. However, I think historical context is important here. After the mess that was late Second Edition, 3e was a surprisingly clear, rational, and accessible restatement of the classic RPG. Most of its major deviations from TSR era D&D, like ascending armor class or new saving throw categories, served good purposes, even if I am no longer wholly on board with many of them. Nevertheless, they worked and facilitated play that, in my experience anyway, was quite reminiscent of how we played D&D in the early to mid-1980s. That's the important thing for me. Had Third Edition not played at the table as well as it did, I very much doubt that I'd have stuck with it. 3e brought me back to Dungeons & Dragons precisely because its designers wanted to produce a "modern" game that played enough like its predecessors that earlier materials were roughly compatible with it. Wizards of the Coast even released a short conversion booklet intended to help 2e players convert characters, magic, and monsters to the new edition. This demonstrates, I think, how seriously WotC at the time took its role as the new custodians of the original roleplaying game. The company wanted to retain old players even as it hoped to reach a new audience.

Of course, Third Edition had a lot of flaws. Like 2e, its presentation left a lot to be desired, particularly its absurd "dungeonpunk" art style. Likewise, several of its new mechanical elements, like feats and prestige classes, soon overshadowed everything else, to the point where the elegance of its core rules design began to buckle and burst. By the end of its run, Third Edition was every bit as bloated and directionless as its predecessor, to the point that I once again abandoned official D&D, this time for good. Fortunately, the SRD and OGL made retro-clones of earlier editions possible and my abandonment of WotC's subsequent versions didn't mean I couldn't keep playing a version of Dungeons & Dragons I still enjoyed, even if it now bore names like Labyrinth Lord or Swords & Wizardry instead.

In the end, I don't see how one can reasonably claim that 3e was either a bad game or a bad edition of D&D, except on the basis of very narrow criteria. I'm as curmudgeonly as they come – remember that I hate plush Cthulhus and fake nerd holidays – and even I am no more willing to indict Third Edition for its worst excesses than I am to indict First Edition because of Unearthed Arcana. From my perspective, 3e injected some much-needed vitality into Dungeons & Dragons at a time when it needed it most. This not only ensured the game's continued pre-eminence among RPGs, but also laid the groundwork for the OSR. That's a legacy well worth celebrating.

That said, 3e's art really did suck.

That said, 3e's art really did suck.

May 17, 2024

The Flammarion Engraving

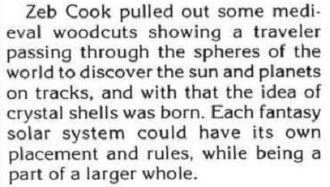

In the foreword to the Lorebook of the Void, one of the two volumes included in the original Spelljammer boxed set, Jeff Grubb talks about a bit about its creative origins. One paragraph of that foreword has long stuck with me.

When I first read this, I thought it was very cool, because, even at the time, I thought D&D could do with a little more genuinely medieval influence on its fantasy. Even if, in the end, the cosmos presented by Spelljammer bore only the most superficial resemblance to the conceptions of medieval thinkers, it was still (in my youthful eyes anyway) a step in the right direction.

When I first read this, I thought it was very cool, because, even at the time, I thought D&D could do with a little more genuinely medieval influence on its fantasy. Even if, in the end, the cosmos presented by Spelljammer bore only the most superficial resemblance to the conceptions of medieval thinkers, it was still (in my youthful eyes anyway) a step in the right direction. I spent some time in the early '90s trying to find these "medieval woodcuts" to no avail. This was before Internet search engines were very good, so I wasn't completely surprised that I might not find a good example of what he might have been referring to. However, some years later I did come across one image that looked like it might have been the kind of thing Grubb had seen.

This is the so-called "Flammarion engraving," which first appeared in the 1888 book, L'atmosphère : météorologie populaire, by Camille Flammarion. Apparently, its artist is unknown, but it became very popular in the 1960s as an illustration of psychedelic experiences, the opening of the human mind to new realities. Regardless of its original intent, it's a very striking and evocative image, so I can understand why it is that Grubb might have been inspired by it, if indeed this is the "medieval woodcut" that David Cook showed him all those years ago.

This is the so-called "Flammarion engraving," which first appeared in the 1888 book, L'atmosphère : météorologie populaire, by Camille Flammarion. Apparently, its artist is unknown, but it became very popular in the 1960s as an illustration of psychedelic experiences, the opening of the human mind to new realities. Regardless of its original intent, it's a very striking and evocative image, so I can understand why it is that Grubb might have been inspired by it, if indeed this is the "medieval woodcut" that David Cook showed him all those years ago.Looking around online, I discovered a blog post by Grubb from more than a decade ago in which he talks a bit about the creation of Spelljammer. It's a very interesting post, filled with plenty of details I didn't know. Among those details is Grubb's admission that, yes, the above image was indeed the one that inspired him, though he connects it to Daniel Boorstin's 1983 book, The Discoverers, rather than Flammarion. I'm glad to know that my guess was correct. Anyway, read the whole blog post if you'd like to know more about the prehistory of Spelljammer.

May 16, 2024

The Path to Adventure

I've commented in several previous posts that the period between 1982 and 1984 is a fascinating one for both TSR and its most famous product, Dungeons & Dragons. This period, I believe, represents the peak of game's faddish popularity, when the company was so flush with cash – and keen to ensure its continued flow – that it slapped the D&D logo on almost everything, from woodburning and needlepoint sets to toys and beach towels, to name just a few. Of course, this same period also saw the publication of the Frank Mentzer edited D&D Basic Set, the best-selling version of that venerable product that TSR ever released, whose sales no doubt contributed greatly to the company's bottom line.

I've commented in several previous posts that the period between 1982 and 1984 is a fascinating one for both TSR and its most famous product, Dungeons & Dragons. This period, I believe, represents the peak of game's faddish popularity, when the company was so flush with cash – and keen to ensure its continued flow – that it slapped the D&D logo on almost everything, from woodburning and needlepoint sets to toys and beach towels, to name just a few. Of course, this same period also saw the publication of the Frank Mentzer edited D&D Basic Set, the best-selling version of that venerable product that TSR ever released, whose sales no doubt contributed greatly to the company's bottom line.

Right smack in the middle of this same period is the premier of the CBS animated television series for which Gary Gygax is credited as a co-producer. The series, which ran for three seasons between 1983 and 1985 and a total of 27 episodes, was part of an effort to increase the pop cultural footprint of D&D beyond the realm of RPGs. So far as I know, the cartoon was the only fruit of that effort, despite Gygax's frequent reports that a Dungeons & Dragons movie of some sort was in the works. Readers more knowledgeable than I can correct me if I am mistaken in this judgment.

Because I was too old for its intended target audience, I never paid close attention to the D&D cartoon during its initial run. Consequently, I took even less note of the various cartoon-branded products released in conjunction with it. I could probably write several posts about this topic and perhaps I eventually will, but, for the moment, what most interests me are the six "Pick a Path to Adventure" books published in 1985 by TSR. As you might expect, these books are all very similar to the Endless Quest series (themselves modeled on the earlier and more well known "Choose Your Own Adventure" books), but drawing on characters and elements of the cartoon.

As I said, I was completely unaware of the existence of these books until comparatively recently. I certainly never saw them at the time of their original publication. Even if I had, there's zero chance I'd have read them, given my superior attitude toward the series and its perceived kiddification of my beloved D&D. Now, I find myself somewhat curious about them, if only because some of them apparently introduce new characters (like Eric the Cavalier's younger brother) and concepts unseen in the series. In addition, each of the six books uses a different member of the ensemble cast as its viewpoint character, which is actually not a bad idea. (Take note as well that first book in the series was written by Margaret Weis of Dragonlance fame).

Looking into these books online revealed that, contemporaneous with the Endless Quest books (and a few years before the cartoon-branded books), TSR produced another series of "Pick a Path to Adventure" books under the Fantasy Forest brand. From what I can tell, they appear to have been geared towards a younger audience than the Endless Quest books. Likewise, these books don't carry the D&D logo anywhere, though some of them, like The Ring, the Sword, and the Unicorn, proclaim "From TSR, Inc., the producers of the DUNGEONS & DRAGONS cartoon show."

Looking into these books online revealed that, contemporaneous with the Endless Quest books (and a few years before the cartoon-branded books), TSR produced another series of "Pick a Path to Adventure" books under the Fantasy Forest brand. From what I can tell, they appear to have been geared towards a younger audience than the Endless Quest books. Likewise, these books don't carry the D&D logo anywhere, though some of them, like The Ring, the Sword, and the Unicorn, proclaim "From TSR, Inc., the producers of the DUNGEONS & DRAGONS cartoon show." Once again, these are books of which I was completely unaware at the time and that I've not seen, let alone read, in the years since. If anyone among my readers has read them, I'd like to know a bit more about them, specifically whether they contain anything that connects them to Dungeons & Dragons. I would assume that they do, because what other purpose would TSR have had in publishing them beyond creating a potential new audience for its games? However, judging solely on the basis of the books' covers, they all look fairly generic. Their connection to D&D, if any, would seem to be limited.

TSR produced another series of "Pick a Path to Adventure" books – or should I say "Pick a Path to Romance and Adventure?" – the (in)famous HeartQuest series of fantasy romance novels. Unlike the other two series, I did know about these. I have a vague recollection of first seeing mention of them in the pages of Dragon, but, despite all my best efforts, I can find no evidence of this. In any case, I saw these in either Waldenbooks or B. Dalton sometimes in 1983 or '84 and had a strongly negative reaction to their existence. Their covers, reminiscent of the Harlequin romance books from the same time, certainly did nothing to endear them to me.

TSR produced another series of "Pick a Path to Adventure" books – or should I say "Pick a Path to Romance and Adventure?" – the (in)famous HeartQuest series of fantasy romance novels. Unlike the other two series, I did know about these. I have a vague recollection of first seeing mention of them in the pages of Dragon, but, despite all my best efforts, I can find no evidence of this. In any case, I saw these in either Waldenbooks or B. Dalton sometimes in 1983 or '84 and had a strongly negative reaction to their existence. Their covers, reminiscent of the Harlequin romance books from the same time, certainly did nothing to endear them to me.Like the Fantasy Forest series, HeartQuest does not seem to have been explicitly connected to Dungeons & Dragons, at least as far as branding goes. From what I've gathered, they're not actually bad books for what they are, though nothing special. I would imagine that they were another prong in TSR's attempts to expand the audience of their products (and thus their sales). Given that, unlike the Endless Quest books, which had several dozen titles, HeartQuest only had six, suggesting that, whatever its quality, they failed to achieve the goals TSR had set for them.

I've sometimes jokingly called 1982–1984 the period when TSR was throwing a lot of spaghetti against the wall in the vain hope that some of it might stick. The company certainly tried many different approaches to expanding its customer base to what appears to have been limited success. On the other hand, these book series may well have played a role in helping to build up the company's publishing division. That division would eventually prove very successful – so successful, in fact, that, by the 1990s, it would become the cart pulling the horse of TSR's fortunes. That's a story for a different day (and probably a different writer, since I don't know enough about its fine details). Still, it's always fascinating to look into the forgotten corners of the hobby's history like the "Pick a Path to Adventure" books.

May 14, 2024

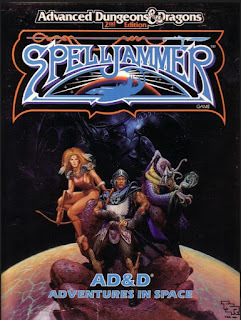

Retrospective: Spelljammer: AD&D Adventures in Space

Spelljammer: AD&D Adventures in Space is a guilty pleasure of mine. Written and conceived by Jeff Grubb, this overstuffed boxed set was first released in 1989, just as I was transferring between two colleges. For a lot of reasons, this was a very tumultuous time in my life and, as a result, my memories of it are very vivid, even thirty-five years later – memories that include purchasing Spelljammer from a Waldenbooks in a suburban mall and then poring over its contents for some time afterwards.

As its subtitle suggests, Spelljammer took AD&D 2e into "space," though not in the traditional scientific (or even science fictional) sense of the word. Rather, Grubb took inspiration from ancient and medieval conceptions of the cosmos, in which the stars and planets are embedded within celestial spheres made of ether. Rather than multiple nested spheres containing all the celestial bodies of a single solar system, as the ancients conceived, Grubb imagined each sphere as encompassing an entire solar system or, more to the point, an entire campaign setting, with all the spheres floating within a "sea" of flammable material called phlogiston.

Through the use of flying vessels equipped with magical "helms," it was possible for the inhabitants of worlds within one sphere to journey to worlds within another. This was the high concept of Spelljammer: the ability to travel between TSR's various campaign settings by means of magical "space" ships. It's a very clever conceit, one reminiscent not just of ancient cosmology but also of Jack Vance's Rhialto the Marvelous. In addition to facilitating transit between existing settings, Spelljammer also opened up the development of a "bridge" setting between them, namely, the larger cosmos of races, organizations, and even worlds that make regular use of space travel.

In some respects, Spelljammer is the forerunner of both Ravenloft: Realm of Terror (1990) and Planescape (1994), two other TSR boxed campaign settings whose conceptual frameworks allowed characters from Greyhawk, the Forgotten Realms, Krynn, and elsewhere to adventure side by side while also exploring entirely new locales created to flesh out the bridge setting. In the case of Spelljammer, that bridge setting includes a mix of the good, the bad, and the downright weird. There's the pompous Elven Navy attempting to keep the peace, xenophobic beholders at war with themselves and everyone else, mysterious mind flayers with their nautilus ships, the spider-like neogi, and mercantile arcane, just to name a few. As presented in Spelljammer, the cosmos was positively filled with all manner of space-faring peoples – and an equally large number of space-based locales and mysteries.

Chief among these mysteries is the titular Spelljammer, an ancient – and gigantic – manta ray-shaped space vessel with an equally gigantic citadel on its back. The origins and true nature of the Spelljammer are unknown, making it the subject of many legends. It's also the destination of many a spacefaring adventurer, as the citadel on its back is reputed to hold untold magic and wealth for those bold enough to venture within. The Spelljammer is thus equal parts the Flying Dutchman of space and an old school megadungeon, which is itself a pretty good high concept.

Of course, Spelljammer was replete with high concepts – and that's part of the problem. In an effort to be expansive and easy to use to use with any existing AD&D campaign setting, Spelljammer is something of a curate's egg. I suspect that this was due less to Jeff Grubb's own preferences and more to directives from TSR regarding the boxed set's place within their larger publishing scheme. This prevents the bridge setting from having a strong flavor of its own, which is too bad, because it contains a lot of elements that I wish had been better (or differently) developed. Instead, the whole thing has a kind of underdone quality that fails to do full justice something I still consider to be a great idea to this day.

Spelljammer straddles the line between the end of the Silver Age and the beginning of the Bronze Age of Dungeons & Dragons, which, I think, explains a lot. Like the products of the Silver Age, Spelljammer is an exemplar of the era's "fantastic realism," itself a metastasis of Gygaxian Naturalism. At the same time, Spelljammer heralds the start of AD&D's "boxed set era," when TSR cranked out new boxed campaign settings (and expansions thereof) almost on a monthly basis – a seemingly never-ending parade of good ideas not given sufficient time to germinate. There's reason why so many gamers of a certain age have such affection for this period of AD&D's development. For all of the flaws in their output, almost all of these boxed sets contained good, imaginative ideas that inspired a lot of us, Spelljammer included.May 13, 2024

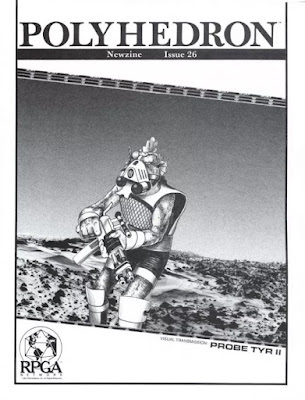

Polyhedron: Issue #26

Issue #26 of Polyhedron (November 1985) is another one that I recall very vividly, almost entirely because of its Roger Raupp cover, depicting a reptilian alien superimposed over what looks to be photograph from one of the Viking landers sent to Mars in the mid-70s. The cover was inspired by Roger E. Moore's article, "Gamma Mars," on which I've briefly commented before. I have lots to say about it but will hold off on doing so until later in this post.

Issue #26 of Polyhedron (November 1985) is another one that I recall very vividly, almost entirely because of its Roger Raupp cover, depicting a reptilian alien superimposed over what looks to be photograph from one of the Viking landers sent to Mars in the mid-70s. The cover was inspired by Roger E. Moore's article, "Gamma Mars," on which I've briefly commented before. I have lots to say about it but will hold off on doing so until later in this post. "Notes from HQ" is, as usual, mostly filled with RPGA ephemera of minimal lasting value. There is, however, a brief section worthy of mention. The "City Project" announced in the previous issue is moving forward, though Penny Petticord asks RPGA members to "hold your actual submissions until specific procedures are announced next issue." Furthermore, she explains HQ "will be finalizing details with Gary Gygax" regarding the placement of the city within the World of Greyhawk setting. Of course, Gygax would depart TSR less than a year later and the City Project would, in turn, head in a different direction.

Next up is "Squeaky Wheels," a guest editorial by Frank Mentzer, in which he tackles criticisms of roleplaying games in the mass media. Mentzer isn't talking solely about the religiously-inflected Satanic Panic – though he does have rebuttals to offer on that score – but also to more general worries about RPGs, such as the suggestion that playing these games inclines one to suicide. I must admit that, despite having lived through these times, I encountered almost no resistance to my involvement in roleplaying. If anything, my parents and the parents of my friends were incredibly supportive of our hobby. Perhaps we were just lucky, I don't know. In any case, I'll never cease to be baffled when I come across articles like this one. They're yet more evidence that the past really is a foreign country.

"Con-Fusion" by Fas Eddie Carmien is a brief collection of thank yous to the volunteers at GenCon 18 – nothing special. "Where Chaos Reigns" by Sonny Scott is more amusing, being a fictionalized account of his time working telephone assistance on behalf of the RPGA at GenCon. Though hardly an article for the ages, it's fun and, as someone who's worked at a phone bank a few times over the course of my life, the inanity of the calls Scott recounts seems very true to life. Michael D. Selinker's "A View of GenCon 18 Game Fair from RPGA Network HQ" is a day-by-day recounting of the con from the perspective of someone involved in its operation. I've never been involved in running a con, so I found this article more interesting than I expected. It's helped by the fact that Selinker can spin a good yarn and has a decent sense of humor.

The third and final part of Frank Mentzer's AD&D tournament adventure, Needle, appears in this issue. Part I focused on the location of the titular obelisk, while Part II was about the process of retrieving it for transport it across the sea. Part III concerns what happens after it's been installed in the palace square of the king who wanted it in the first place. In case you're wondering: a magical door to the Moon opens in its base and the characters must journey through it to see its wonders. As premises for an adventure go, it's not a bad one and Mentzer does a solid job of presenting intriguing and challenging encounters.

"Dispel Confusion" is short this month, tackling only AD&D and Gamma World questions, none of which are especially memorable. For me, what's most fascinating is how increasingly truncated this column has become. In early issues of Polyhedron, "Dispel Confusion" covered two or three pages and covered all of TSR's RPGs. As time went on, its page length shortened and its focus contracted, with only AD&D and Gamma World being consistently covered. The former is understandably, as it was always TSR's most popular and best selling game. Gamma World's continued presence strikes me as stranger, as I never got the impression it was very successful, despite its having no fewer than four editions during TSR's time.

Speaking of Gamma World, we come at last to Roger E. Moore's "Gamma Mars," which, as its title suggests, presents information on the state of the planet Mars in the post-apocalyptic 25th century of the game. In this timeline, Mars was first visited by human beings in 2002, with a stable colony growing there over the course of the 21st century. By 2076, the colony became independent of Earth. The colonists would eventually discover evidence of alien habitation on the planet – the reptilian Luntarians – but these beings are not natives to Mars but visitors from another planet outside our solar system. A small number of Luntarians placed themselves into suspended animation in the past and were subsequently revived just in time for the Social Wars to engulf Earth and cut Mars off from the mother planet.

I was a big fan of the articles from Dragon that described the state of the Moon in Gamma World, so I was understandably excited to learn more about the wider solar system of the game's setting. As described by Moore, Mars has only been partially terraformed. Its atmosphere, for example, remains too thin for humans to breathe unaided. In addition, pure strain humans predominate, since Mars largely sat out the conflict that devastated Earth. The result is a very different take on Gamma World, one where rival cities jockey with one another for power and rumors of alien ruins and technology form the basis for adventure. At the time, I found it compelling stuff; even now, I think there's something remarkable about it.

Jon Pickens provides "Unofficial Illusionist Spells" that are actually fairly interesting, at least when compared to the cleric and magic-user spells from previous issues. I think that's because, in AD&D, there are comparatively few illusionist magic items and thus the spells here don't exist primarily to act as means of explaining how such items exist. Michael Przytarski's "Fletcher's Corner" also deals with magic, in this case magic items, which he first divides into the categories of "mundane, powerful, deadly, and ridiculous" with the goal of suggesting how common each type should be in a good campaign. He also addresses the question of "magic shops," something I get the impression was becoming increasingly common in mid-80s AD&D (based on how often it was criticized in official TSR publications). The issue ends with Errol Farstad's positive review of Twilight: 2000.

Twenty-six issues in, Polyhedron continues to lack a solid, consistent foundation on which to build. As I have repeatedly said in this series, you never know what to expect from an issue, with some having numerous useful and excellent articles and others ... less so. While I completely understand why this was the case, it's disappointing and played a big part in why I'd eventually let my subscription lapse, even as I continued to read Dragon for many more years to come.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers