James Maliszewski's Blog, page 51

July 2, 2024

They're Multiplying ...!

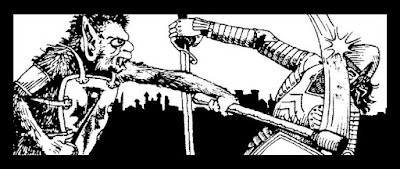

The discussion surrounding the depiction of gnolls in TSR era Dungeons & Dragons has been quite lively, both in the comments and in emails sent to me privately. Another commenter pointed me toward an even more obscure gnoll illustration.

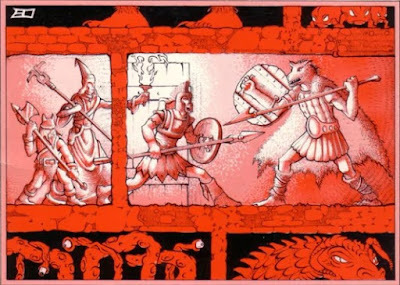

This full-page piece originally appeared in 1981's

The Sinister Secret of Saltmarsh

and is by Stephen D. Sullivan. There are two gnolls depicted above, both in the center of the illustration. The first is standing upright, grappling with a sword-wielding fighter. The other is on the ground, biting at the fighter's leg. It's an odd thing to depict, since I don't recall gnoll's having a bite attack in any TSR edition of D&D, but, if I am mistaken about this, I am certain one of you will correct me. In any case, Sullivan's gnolls teeter on the line between looking properly hyena-like and more canine/lupine. Personally, I prefer it when monsters are their own thing, not just real-world animals with a few bits added or subtracted, so I don't want gnolls to look exactly like hyenas. At the same time, I also don't want them to be dog or wolf-men either (though, interestingly, The Keep on the Borderlands) does, on its rumor table, describe them as "big dog-men," so what do I know?

This full-page piece originally appeared in 1981's

The Sinister Secret of Saltmarsh

and is by Stephen D. Sullivan. There are two gnolls depicted above, both in the center of the illustration. The first is standing upright, grappling with a sword-wielding fighter. The other is on the ground, biting at the fighter's leg. It's an odd thing to depict, since I don't recall gnoll's having a bite attack in any TSR edition of D&D, but, if I am mistaken about this, I am certain one of you will correct me. In any case, Sullivan's gnolls teeter on the line between looking properly hyena-like and more canine/lupine. Personally, I prefer it when monsters are their own thing, not just real-world animals with a few bits added or subtracted, so I don't want gnolls to look exactly like hyenas. At the same time, I also don't want them to be dog or wolf-men either (though, interestingly, The Keep on the Borderlands) does, on its rumor table, describe them as "big dog-men," so what do I know?

OK, One More

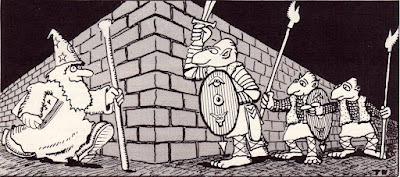

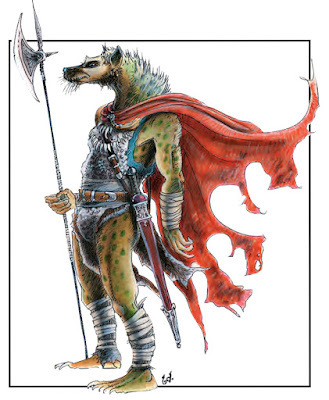

Once again, my readers have demonstrated that they have better memories than I. There is indeed an illustration of a gnoll in The Secret of Bone Hill. The illustration in question is by Harry Quinn, an underappreciated TSR artist whose name is rarely brought up in discussions like these.

A couple of things immediately strike me about this piece. Most obviously, the gnoll definitely looks more wolfish than hyena-like, an impression that's probably heightened by the fact that there are also two actual wolves depicted here. In addition, this gnoll seems to be wearing the same kind of attire (padded or scaled shirt with a leather skirt and huge girdle) originally seen in Sutherland's Monster Manual illustration. Likewise, he wields a spear, which, based on previous illustrations seems to be the signature weapon of gnolls (assuming we count polearms as a flavor of spear).

A couple of things immediately strike me about this piece. Most obviously, the gnoll definitely looks more wolfish than hyena-like, an impression that's probably heightened by the fact that there are also two actual wolves depicted here. In addition, this gnoll seems to be wearing the same kind of attire (padded or scaled shirt with a leather skirt and huge girdle) originally seen in Sutherland's Monster Manual illustration. Likewise, he wields a spear, which, based on previous illustrations seems to be the signature weapon of gnolls (assuming we count polearms as a flavor of spear).I find it fascinating how often a single artist set the terms for all those who followed him. As I look more closely at the depictions of various humanoid monsters in D&D, it becomes ever clearer how common this is throughout the game's early history. This is especially true, I think, for monsters, humanoid or otherwise, that are unique to Dungeons & Dragons. Since there was no prior tradition of them on which to draw, there was a good chance that the work of the first artist to draw a given monster would become definitive – the one later artists would look to for inspiration in their own work. That's clearly what has happened in the case of gnolls, even if, as in Harry Quinn's case, he introduced some variations of his own.

July 1, 2024

One More

Reader Lore Suto pointed out that I'd overlooked an important early illustration of the gnoll – by Erol Otus, no less! The image appears on the cover of the AD&D Dungeon Masters Adventure Log. Appearing in 1980, I have a great fondness for this particular product, which I used a lot in my youth. That's why I can't believe I'd forgotten that the cover featured a party of adventurers squaring off against a gnoll.

It's a terrific illustration that recalls Sutherland's original from the Monster Manual, right down to the gnoll's arms and armor. To my eyes, Otus's gnoll looks a bit more wolfish than does Sutherland's, but I like it nonetheless. I like it, too, because it's a good reminder that, despite his reputation for "trippy" visuals, Erol Otus was quite capable of something more akin to "traditional" D&D art, of which this piece is a solid example.

It's a terrific illustration that recalls Sutherland's original from the Monster Manual, right down to the gnoll's arms and armor. To my eyes, Otus's gnoll looks a bit more wolfish than does Sutherland's, but I like it nonetheless. I like it, too, because it's a good reminder that, despite his reputation for "trippy" visuals, Erol Otus was quite capable of something more akin to "traditional" D&D art, of which this piece is a solid example.

June 30, 2024

A (Very) Partial Pictorial History of Gnolls

There's no use in fighting it. You'll be seeing more entries in what has inadvertently become a series for a few more weeks at least, perhaps longer. After last week's post on bugbears, which are a uniquely D&D monstrous humanoid, I knew I'd have to turn to gnolls this week, as they, too, are unique to the game. Perhaps I should clarify that a little. There is no precedent, mythological or literary, for the spelling "gnoll." However, the spelling "gnole" appears in "How Nuth Would Have Practised His Art Upon the Gnoles" from Lord Dunsany's 1912 short story collection, The Book of Wonder (as well as in Margaret St. Clair's "The Man Who Sold Rope to the Gnoles").

There can be no doubt that Dunsany's story served as the seeds for the gnolls of D&D. In their description in Book 1 of OD&D, gnolls are described as "a cross between Gnomes and Trolls (. . . perhaps, Lord Sunsany [sic] did not really make it all that clear." The original short story contains no description of the titular creature, leaving Gygax to advance his theory of gnolls being a weird hybrid monster. Artist Greg Bell interprets them thusly:

Sometime in the three years between their first appearance in OD&D (1974) and the publication of the Monster Manual (1977), someone at TSR decided that gnolls were, in fact, "low intelligence beings like hyena-men." That's how they're described in J. Eric Holmes's Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set, which is where I first encountered them, courtesy of this delightful illustration by Tom Wham:

Sometime in the three years between their first appearance in OD&D (1974) and the publication of the Monster Manual (1977), someone at TSR decided that gnolls were, in fact, "low intelligence beings like hyena-men." That's how they're described in J. Eric Holmes's Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set, which is where I first encountered them, courtesy of this delightful illustration by Tom Wham:

Meanwhile, the Monster Manual itself, published the same year, gives us this illustration by Dave Sutherland.

Meanwhile, the Monster Manual itself, published the same year, gives us this illustration by Dave Sutherland.

The Monster Manual also includes another Sutherland gnoll-related piece, this time of Yeenoghu, the demon lord of gnolls. To my eyes, Yeenoghu looks a lot more hyena-like than does the illustration above, but, even so, they're still broadly similar.

The Monster Manual also includes another Sutherland gnoll-related piece, this time of Yeenoghu, the demon lord of gnolls. To my eyes, Yeenoghu looks a lot more hyena-like than does the illustration above, but, even so, they're still broadly similar.

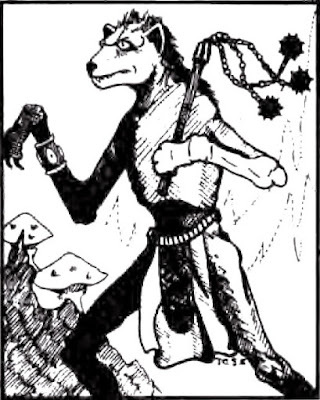

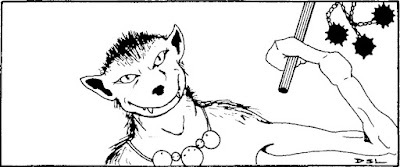

Speaking of Yeenoghu, he reappears in the pages of

Deities & Demigods

, this time depicted by Dave LaForce. I've always found this version of the demon lord a bit goofy. I'm not sure if it's his grin or the strangeness of the arm that holds his infamous triple flail.

Speaking of Yeenoghu, he reappears in the pages of

Deities & Demigods

, this time depicted by Dave LaForce. I've always found this version of the demon lord a bit goofy. I'm not sure if it's his grin or the strangeness of the arm that holds his infamous triple flail.

The AD&D Monster Cards sets are a good source of unusual takes on many monsters and that's especially so in the case of gnolls. Artist Harry Quinn depicts them in a way that, to my eyes, looks decidedly feline. To anyone familiar with the weird phylogenetics of hyenas, that's inappropriate, but it still feels off somehow. Perhaps it's simply the weight of all the previous depictions that makes me think so. In any case, Quinn's version of the gnoll is quite distinctive.

The AD&D Monster Cards sets are a good source of unusual takes on many monsters and that's especially so in the case of gnolls. Artist Harry Quinn depicts them in a way that, to my eyes, looks decidedly feline. To anyone familiar with the weird phylogenetics of hyenas, that's inappropriate, but it still feels off somehow. Perhaps it's simply the weight of all the previous depictions that makes me think so. In any case, Quinn's version of the gnoll is quite distinctive.

The 2e Monstrous Compendium features what is probably the most hyena-like of all versions of the gnoll, courtesy of James Holloway.

The 2e Monstrous Compendium features what is probably the most hyena-like of all versions of the gnoll, courtesy of James Holloway.

Tony DiTerlizzi provides an even more hyena-like version of the gnoll in the Monstrous Manual, right down the spots on its fur.

Tony DiTerlizzi provides an even more hyena-like version of the gnoll in the Monstrous Manual, right down the spots on its fur.

I feel like I have probably overlooked some illustrations of gnolls from the TSR era of D&D, but, if so, they must be fairly obscure, as these are the only ones I could easily find in my collection. What's most notable about the ones I did find is how closely they hew to the post-OD&D notion that gnolls are hyena-men. I'd chalk up most of the differences to artist skill and choice rather than a fundamental disagreement about this fact. In this respect, they're quite similar to bugbears, another distinctly D&D monster whose look stayed largely the same during TSR's stewardship of Dungeons & Dragons.

I feel like I have probably overlooked some illustrations of gnolls from the TSR era of D&D, but, if so, they must be fairly obscure, as these are the only ones I could easily find in my collection. What's most notable about the ones I did find is how closely they hew to the post-OD&D notion that gnolls are hyena-men. I'd chalk up most of the differences to artist skill and choice rather than a fundamental disagreement about this fact. In this respect, they're quite similar to bugbears, another distinctly D&D monster whose look stayed largely the same during TSR's stewardship of Dungeons & Dragons.

June 29, 2024

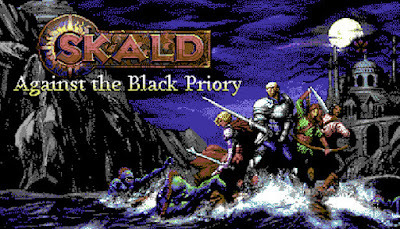

Against the Black Priory

Back at the start of April, I wrote about my inability to replay the old AD&D computer game, Pool of Radiance. The difficulty lay primarily in its user interface, which was clunky and difficult to use on a contemporary computer. Likewise, the graphics, which looked fine on the screen in the late 1980s, did not translate well on a better monitor with a higher resolution. Consequently, I found it nigh impossible to play, let alone enjoy, Pool of Radiance again (or likely any of the other AD&D computer RPGs from that era). That's a shame, because I'm a fan of computer roleplaying games and am always on the lookout for enjoyable ones.

Back at the start of April, I wrote about my inability to replay the old AD&D computer game, Pool of Radiance. The difficulty lay primarily in its user interface, which was clunky and difficult to use on a contemporary computer. Likewise, the graphics, which looked fine on the screen in the late 1980s, did not translate well on a better monitor with a higher resolution. Consequently, I found it nigh impossible to play, let alone enjoy, Pool of Radiance again (or likely any of the other AD&D computer RPGs from that era). That's a shame, because I'm a fan of computer roleplaying games and am always on the lookout for enjoyable ones.Fortunately, I stumbled across Skald: Against the Black Priory , a brand new (released May 2024) computer RPG inspired by the 8-bit CRPGs of old, while introducing aspects of modern design to make it more playable on contemporary machines. Though Skald no doubt took a lot of inspiration from games like Bard's Tale – likely explaining its title – one of the things that sets it apart in my opinion is the combination of sword-and-sorcery and cosmic horror of its narrative. Think Robert E. Howard's "Worms of the Earth" or Clark Ashton Smith's Hyperborea stories and you have a good idea of the kind of thing I'm talking about.

I've enjoyed my time playing the game. It's party-based (with up to six characters) and uses a top-down perspective, in keeping with its inspirations. There are lots of little details hidden throughout the game, both to assist you in your quests and to paint a picture of the overall setting. The game is quite unforgiving at times (again, in keeping with its inspirations). Not only are enemies tough, especially at low levels, but there are some choices you can make that result in automatic death. Though its interface is better suited to modern sensibilities, the game itself is quite old school in its deadliness (though there is an option for "narrative play," if you aren't interested in a challenge).

All in all, I have almost entirely positive feelings about Skald: Against the Black Priory. My biggest complaints are minor (the combat system can be grindy) and are outweighed by the game's cleverness and atmosphere. Playing through it has definitely whetted my appetite for more games like this. Now, I just need to find them ...

June 28, 2024

REPOST: Have Space Suit – Will Travel

[This is a repost of something I wrote almost four years ago. Last night, I found myself thinking about space suits in science fiction RPGs and decided to write a post about it. As usual, I soon realized I'd done it before. Rather than abandon the idea, I thought I'd repost this, since its initial appearance was very early after I'd returned to blogging and was therefore not widely read.]

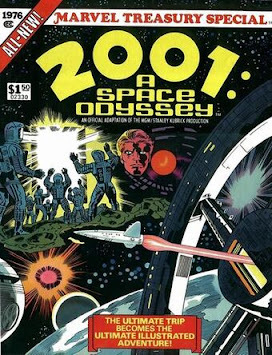

When I was a child, I owned a copy of the Marvel Treasury Special adaptation of 2001 by Jack Kirby. I can't recall how I acquired it, though I suspect it was a gift by a well-meaning relative who knew that I liked science fiction. I am certain that I read the comic before I ever saw the movie (which wasn't released on home video until 1980). The combination of Clarke's story, Kubrick's visuals, and Kirby's art was a heady mix and I was equally enthralled and frightened by what I saw in those large newsprint pages.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I became a fan of 2001: A Space Odyssey when I finally did see the film and it remains one of my favorite movies. I recently re-watched it; my feelings toward it are unchanged: I consider it not only one of the greatest science fiction films of all time, but one of the greatest films regardless of genre.Even if you disagree with that assessment, it's hard to deny how influential the movie is. Without even paying close attention, you can recognize imagery, set designs, costuming, even plot details that have clear echoes in subsequent motion pictures. Ash from Alien owes a lot to HAL 9000, for example, particularly in his having been given a hidden agenda at odds with those of the human characters. Likewise, the Enterprise's encounter with V'ger in Star Trek: The Motion Picture would have been impossible without the final act of 2001, "Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite."

Growing up in the immediate aftermath of the Apollo lunar lanading, astronauts and space suits were everywhere. 2001 has particularly stylish and iconic space suits – so much so that I am convinced the multi-colored thruster suits from the aforementioned Star Trek film are a tribute to those in Kubrick's masterpiece. Come to think of it, Alien also had remarkable space suits, but those are the work of French artist Jean Giraud, better known by his nom de plume, Moebius.

On the other hand, science fiction like Star Wars or Battlestar Galactica didn't have a place for space suits – flight helmets, yes, but not full suits of the sort seen elsewhere. It's probably for this reason that I've subconsciously come to divide space-oriented sci-fi into space suit and non-space suit categories, with the former being more "serious" than the latter. The lack of space suits is something I associate with action-oriented space opera rather than idea-based science fiction. Obviously, this is a completely unfair distinction, one largely based, I imagine, on the prominence that space suits had in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Nevertheless, it's a distinction that's been lurking at the back of my mind since childhood, affecting even my feelings about science fiction roleplaying games. One of the most basic and ubiquitous skills in GDW's Traveller is Vacc Suit (though I've never discovered the origin of the second "c" in the word). Consequently, I've always seen the game as a sober, serious, and indeed thoughtful game, compared to, say, TSR's Star Frontiers, which, while I have a great fondness for it, didn't even mention space suits or their equivalent until the release of the Knights Hawks expansion a year later. Ironically, it was Star Frontiers that saw an adventure module based on 2001: A Space Odyssey, not Traveller, which only goes to show how arbitrary distinctions like this can be.

June 26, 2024

Peace Finally Comes

I've mentioned a couple of times previously that I'm currently playing in a Traveller campaign refereed by an old friend of mine. I first met this particular friend around 1990 through a Traveller fan organization known as the History of the Imperium Working Group (HIWG – pronounced Hi-Wig). HIWG's original purpose was to assist GDW in developing the Third Imperium setting during the MegaTraveller era, when the Imperium was in the throes of a succession crisis/civil war inexplicably known as the Rebellion.

HIWG had a fanzine called Tiffany Star that was released more or less bimonthly, starting in January 1988. Its first issue included a map of the warring factions of the fragmented Third Imperium as they were five years after the start of the Rebellion, which I've reproduced below.

The map originated with Marc Miller at GDW and bears the title "Peace Finally Comes." The original idea behind it was that this map would represent the end state of the Rebellion, after its factions had become exhausted by years of open warfare between one another. What was interesting about it is that there were a couple of missing factions, which is to say, factions from the early phases of the Rebellion that had seemingly disappeared, leading to much speculation about the circumstances under which they were defeated or subsumed into other factions Likewise, many of the remaining factions had grown or contracted in their astrographic extent.

The map originated with Marc Miller at GDW and bears the title "Peace Finally Comes." The original idea behind it was that this map would represent the end state of the Rebellion, after its factions had become exhausted by years of open warfare between one another. What was interesting about it is that there were a couple of missing factions, which is to say, factions from the early phases of the Rebellion that had seemingly disappeared, leading to much speculation about the circumstances under which they were defeated or subsumed into other factions Likewise, many of the remaining factions had grown or contracted in their astrographic extent. Figuring out how this had all happened was part of HIWG's original remit. Certain members of the organization were "sector analysts," whose job it was to create and collate material pertaining to one of the sectors of the Imperium or surrounding space. In theory, this material would then be used by GDW in creating future MegaTraveller products. I was the sector analyst for Antares sector, while my friend was the sector analyst for Lishun sector to spinward. We became friends because we started exchanging letters – remember, this was in that benighted time just before the advent of the consumer Internet – and sharing information of mutual interest. Later, when I went to graduate school, it just so happened that I moved to the same city as my HIWG pen pal and we've been friends ever since.

When I again saw the Peace Map, as we called it, for the first time in many years, I felt a huge rush of nostalgia, not just for MegaTraveller, warts and all, but for one of my earliest and most serious brushes with organized RPG fandom. Remember, as I said, that this was before the Internet was in widespread use. Almost none of us had email addresses, let alone a regular means of real time chat. Instead, we exchanged photocopied (or dot matrix printed) materials by post, occasionally meeting at conventions if they were geographically convenient. It was slow, inefficient, and occasionally frustrating, but also a great deal of fun. I made a lot of friends through HIWG, several of whom are still in contact with me.

Beyond that, the Peace Map represents a path not taken for Traveller. The whole point of the Rebellion was to shake up the staid status quo of the Third Imperium by creating multiple successor states suspicious of one another. This created many more opportunities for adventure, intrigue, and outright warfare. This greatly appealed to me and my preference for smaller settings. I was quite excited by the possibilities, especially for my beloved League of Antares faction. Alas, it was not to be. Instead, GDW opted to descend the Imperium – and, later, most of charted space – into a new dark age with almost no interstellar states and most worlds regressing both technologically and socially. What a waste!

I still have dreams of one day revisiting my own vision of a post-Rebellion Third Imperium setting, one where the fragments of the shattered Imperium survived and pursued their own destinies. I don't know that I'll ever get around to refereeing such a campaign, but a man can dream ...

June 25, 2024

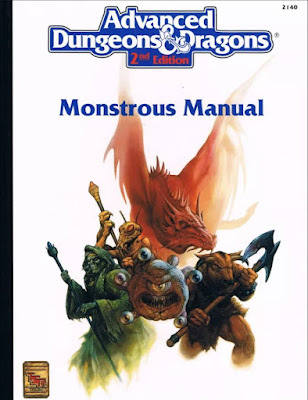

Retrospective: Monstrous Manual

In the course of writing posts about the pictorial histories of several standard Dungeons & Dragons monsters, I often consulted 1993's Monstrous Manual. This book, released four years after the launch of AD&D Second Edition was, according to its own introduction, "created in response to many requests to gather monsters into a single, durable volume which would be convenient to carry." The introduction goes on to say that, alongside the Player's Handbook and Dungeon Master's Guide, the Monstrous Manual "forms the core of the AD&D 2nd Edition game."

In the course of writing posts about the pictorial histories of several standard Dungeons & Dragons monsters, I often consulted 1993's Monstrous Manual. This book, released four years after the launch of AD&D Second Edition was, according to its own introduction, "created in response to many requests to gather monsters into a single, durable volume which would be convenient to carry." The introduction goes on to say that, alongside the Player's Handbook and Dungeon Master's Guide, the Monstrous Manual "forms the core of the AD&D 2nd Edition game."Those unfamiliar with the history of Second Edition can be forgiven for wondering why it took TSR four years to publish what is essentially an updated version of the venerable Monster Manual or why this version carries a slightly different title than its predecessor, unlike either the PHB or DMG, whose titles remained the same. The truth is that the Monstrous Manual was a do-over, TSR's attempt to fix the grave mistake of the Monstrous Compendium, released in 1989 along with the other 2e rulebooks. Rather than being a hardcover book, the Compendium was a D-ring binder designed to hold loose, three-hole punched sheets of monster entries. The Compendium was an interesting high concept, its actual implementation proved impractical o multiple levels, hence the need for the Monstrous Manual.

The Monstrous Manual is a very large book, larger than either of its companion 2e volumes or indeed of any AD&D rulebook published up to that point. At 384 pages, it includes all the contents of Volumes One and Two of the original Monstrous Compendium, along with additional monsters imported from the MC volumes associated with the Greyhawk, Forgotten Realms, Spelljammer, and Dark Sun settings. By necessity, many of these entries are abbreviated in length from their original Compendium appearances, since, with a handful of exceptions, all are limited to a single page. Even so, the book uses a small type face and all the entries are quite dense. Like the MC, each entry includes an illustration – this time in color – but, unlike its predecessor, these illustrations are largely provided by a new generation of artists rather than longtime TSR hands like Jeff Easley or James Holloway.

The presence of these new artists, most notably Tony DiTerlizzi, gives the Monstrous Compendium a very distinctive look, one that stands out from earlier 2e releases. I remember being struck by this even at the time I originally bought the book. DiTerlizzi, for example, is best known for his defining work on the Planescape setting, which didn't come out until a year later. His illustrations in the Monstrous Manual are uniformly excellent and admirable – but they nevertheless represent a strong break with AD&D's artistic past, which had broadly favored artwork with a more "traditional" high fantasy/sword-and-sorcery esthetic. DiTerlizzi's work meanwhile has an otherworldly, fairytale-ish quality that works better for some monsters than for others. Likewise, it contrasts with the comic book-inspired illustrations of Jeff Butler and the dark moodiness of Thomas Baxa, two other artists whose styles are quite different from those of TSR's past. The result is, by my lights, an artistic mishmash that detracts somewhat from its content.

And that content is, by and large, quite solid. The Monstrous Manual is good and useful, eminently more suited to its purpose than was the Monstrous Compendium, if for no other reason than it is practical. As I mentioned above (and in my earlier Retrospective post about it), the MC was an interesting high concept that might have worked had TSR thought a little more about the details of its design. There is nothing clever about the design of the Monstrous Manual, but it at least served its intended purpose without much fuss. That it also included a very large selection of monsters – far more than the original Monster Manual – was another point in its favor.

From the vantage point of more than three decades after its original publication, what strikes me most about the Monstrous Manual is how it reminds that TSR never had a clear plan of what to do with AD&D as a game line and, even when it did, it often bungled those plans. From its original conception under Gary Gygax to its eventual realization under David Cook, AD&D 2e was always conceived as a way to correct, regularize, and improve upon the foundations laid by First Edition. However, for various reasons, those plans never fully came to pass. Instead, we got missteps, half-measures, and course corrections that, in retrospect, casts a shadow even over the best products of 2e, like the Monstrous Manual.

Bogeyland

In his comment to yesterday's post about bugbears, Jesse Smith connected bugbears to bogeymen, which awakened a forgotten memory of my childhood. During the Christmas season growing up, one of the local TV stations always broadcast March of the Wooden Soldiers, the abridged version of the 1934 Laurel and Hardy film, Babes in Toyland (itself loosely based on the 1903 operetta of the same name). The movie was a favorite mine and, in this era before videotapes made it possible to watch almost any movie whenever you wanted, I looked forward to its broadcast each year.

In his comment to yesterday's post about bugbears, Jesse Smith connected bugbears to bogeymen, which awakened a forgotten memory of my childhood. During the Christmas season growing up, one of the local TV stations always broadcast March of the Wooden Soldiers, the abridged version of the 1934 Laurel and Hardy film, Babes in Toyland (itself loosely based on the 1903 operetta of the same name). The movie was a favorite mine and, in this era before videotapes made it possible to watch almost any movie whenever you wanted, I looked forward to its broadcast each year. The actual plot of March of the Wooden Soldiers isn't particularly important. It's a comedic fairytale film set in Toyland, with Laurel and Hardy playing two friends, Stannie Dum and Ollie Dee, who work for the Toymaker, who, in turn, supplies toys for Santa Claus. Also living in Toyland is Silas Barnaby, the Crooked Man, who is also the town's richest inhabitant. By duplicitous means, Barnaby frames Tom-Tom the Piper's Son for the kidnapping and probable murder of one of the Three Little Pigs, resulting in his banishment to Bogeyland.

In the movie, Stannie and Ollie talk about Bogeyland and its inhabitants, the Bogeymen:

STANNIE: What happens to you in Bogeyland?

OLLIE: Oh, it's a terrible place. Once you go there, you never come back.

STANNIE: Why?

OLLIE: Well, when the Bogeyman gets you, they eat you alive!

STANNIE: What do they look like?

OLLIE: Well, I've heard that they're half man, and half animal. With great big ears ... and great big mouths. And hair all over their body. And long claws that they catch you with.

For reference, this is what one of the Bogeymen looks like:

As you can see, it's a pretty simple costume – little more than a loose, furry bodysuit with a rubbery fright mask and wig. On one level, it's kind of ridiculous and not at all frightening. On another, though, it's surprisingly effective, precisely because it's so crude and obviously fake. There's something strangely off-putting about its look, something that both frightened and fascinated me as a child.

As you can see, it's a pretty simple costume – little more than a loose, furry bodysuit with a rubbery fright mask and wig. On one level, it's kind of ridiculous and not at all frightening. On another, though, it's surprisingly effective, precisely because it's so crude and obviously fake. There's something strangely off-putting about its look, something that both frightened and fascinated me as a child. Unsurprisingly, the Bogeymen left a deep impression on my imagination, so deep that, until I read Jesse Smith's comment on yesterday's post, I hadn't realized the extent to which my conception of D&D's various monstrous humanoids owed to them. The Bogeymen are vicious, bestial things who obviously hate goodness and delight in chaos. Later in the movie, Silas Barnaby rallies them to his side. He leads a horde of Bogeymen in an assault on Toyland, where they wreak havoc upon its buildings and inhabitants.

The scene where they come pouring out of the caves of Bogeyland is another image burned into my brain. The combination of both their numbers and their malice is so great that, for a time, it appears as if Barnaby will be successful in his revenge plot against the people of Toyland. What he didn't count on were the titular wooden soldiers, oversized toys mistakenly made at 6 feet tall instead of 6 inches. Ollie and Stannie activate them and, with their help, they push back the Bogeymen back to their caves. It's a great battle for such a silly film.

So, yeah, I can see a lot of appeal of imagining bugbears as bogeymen. Honestly, I'd love to see Dungeons & Dragons and other fantasy RPGs take more inspiration from unusual sources like this. We need to make monsters monstrous again.

June 24, 2024

A (Very) Partial Pictorial History of Bugbears

Since my recent forays into the artistic evolution of both kobolds and goblins (not to mention orcs) have proved popular with readers, I thought I'd continue to look into other well-known Dungeons & Dragons monsters for a few more weeks. This time, I'm looking at the bugbear, both because it's completely unique to D&D, but also because, with one very important exception, its representation in artwork has been very consistent – far more so than any of the previous monstrous humanoids I've examined so far.

Of course, that one exception is a big one. More than that, it's the original illustration of the bugbear, as drawn by Greg Bell in OD&D's Supplement I (1975). Look upon his majesty!

I actually really like this illustration, because it's just so weird. That pumpkin head – the result of a miscommunication between Bell and Gygax – makes it quite clear that you're dealing with a wholly inhuman monster, despite its two arms, two legs, and upright stance. These days, this is how I prefer my monstrous humanoids, so I may be unduly biased toward it. Regardless, it's an oddity and an outlier that no subsequent TSR era D&D artist has ever used as inspiration for his interpretation of it – a pity!

I actually really like this illustration, because it's just so weird. That pumpkin head – the result of a miscommunication between Bell and Gygax – makes it quite clear that you're dealing with a wholly inhuman monster, despite its two arms, two legs, and upright stance. These days, this is how I prefer my monstrous humanoids, so I may be unduly biased toward it. Regardless, it's an oddity and an outlier that no subsequent TSR era D&D artist has ever used as inspiration for his interpretation of it – a pity!With the AD&D Monster Manual (1977), we see the first examples of what will eventually become the iconic appearance of the bugbear – little wonder, since it's by Dave Sutherland, the artist most responsible in my opinion for the esthetic of old school D&D.

Here's another instance of a bugbear from the Monster Manual, this time drawn by Dave Trampier. I find this second piece interesting, because it's clear that Tramp is using Sutherland's illustration above as a model. These are clearly the same monster drawn by two different artists.

Speaking of Tramp, he drew another early bugbear illustration, which appeared in 1978's Descent into the Depths of the Earth. Once again, this is clearly the same monster as those depicted in the MM, but, this time, they have a slightly more cartoonish look to them, almost like characters out of Trampier's Wormy comic.

Speaking of Tramp, he drew another early bugbear illustration, which appeared in 1978's Descent into the Depths of the Earth. Once again, this is clearly the same monster as those depicted in the MM, but, this time, they have a slightly more cartoonish look to them, almost like characters out of Trampier's Wormy comic.

Next up are some Grendadier Model sculpts of bugbears from 1980. As you can see, these, too, are in keeping with the basic appearance laid down by Dave Sutherland a few years earlier – big, furry brutes with wide mouths full of sharp teeth and large ears.

Next up are some Grendadier Model sculpts of bugbears from 1980. As you can see, these, too, are in keeping with the basic appearance laid down by Dave Sutherland a few years earlier – big, furry brutes with wide mouths full of sharp teeth and large ears.

1980 was also the year in which Deities & Demigods appeared. Though bugbears as such do not appear in the book, we do get a depiction of their deity, Hruggek, as drawn by Dave LaForce. I'm not fond of this illustration, which I've always found a bit goofy. Maybe it's the grin, I don't know. Still, it's broadly in keeping with what we've come to expect of bugbears up till now.

1980 was also the year in which Deities & Demigods appeared. Though bugbears as such do not appear in the book, we do get a depiction of their deity, Hruggek, as drawn by Dave LaForce. I'm not fond of this illustration, which I've always found a bit goofy. Maybe it's the grin, I don't know. Still, it's broadly in keeping with what we've come to expect of bugbears up till now.

In 1982, the

AD&D Monster Cards

include a bugbear, its illustration done by Jim Holloway. This may be the first piece of color artwork for the monster in the history of the game.

In 1982, the

AD&D Monster Cards

include a bugbear, its illustration done by Jim Holloway. This may be the first piece of color artwork for the monster in the history of the game.

Second Edition's Monstrous Compendium (1989) includes this artwork, again by Jim Holloway. While still largely in keeping with its predecessors, I notice that the bugbear's face is now arranged more like that of a human being. Both its mouth and ears are smaller, for example, though its nose remains large and broad.

Second Edition's Monstrous Compendium (1989) includes this artwork, again by Jim Holloway. While still largely in keeping with its predecessors, I notice that the bugbear's face is now arranged more like that of a human being. Both its mouth and ears are smaller, for example, though its nose remains large and broad.

Finally, there's Tony DiTerlizzi's take on bugbears from 2e's Monstrous Manual (1993). I'm not sure what to make of this illustration. While it retains the overall look of Sutherland's original, I feel like it continues down the path laid down by the Monstrous Compendium of giving bugbears human proportions, which undercuts their monstrousness, something I've come to see as a mistake in the portrayal of D&D's humanoid monsters.

Finally, there's Tony DiTerlizzi's take on bugbears from 2e's Monstrous Manual (1993). I'm not sure what to make of this illustration. While it retains the overall look of Sutherland's original, I feel like it continues down the path laid down by the Monstrous Compendium of giving bugbears human proportions, which undercuts their monstrousness, something I've come to see as a mistake in the portrayal of D&D's humanoid monsters.

I am certain I've overlooked several other examples of bugbear illustrations from TSR era Dungeons & Dragons. Feel free to point me toward others that you've found. I'm particularly interested in any examples of bugbears that, like Greg Bell's OD&D version, deviate greatly from the model laid down by Sutherland. My suspicion is that there won't be many (or any) such examples, because, for whatever reason, most old school D&D illustrators more or less followed in the footsteps of their predecessors, something we don't see in quite the same way with many other monsters. I wonder why that is.

I am certain I've overlooked several other examples of bugbear illustrations from TSR era Dungeons & Dragons. Feel free to point me toward others that you've found. I'm particularly interested in any examples of bugbears that, like Greg Bell's OD&D version, deviate greatly from the model laid down by Sutherland. My suspicion is that there won't be many (or any) such examples, because, for whatever reason, most old school D&D illustrators more or less followed in the footsteps of their predecessors, something we don't see in quite the same way with many other monsters. I wonder why that is.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers