James Maliszewski's Blog, page 49

July 22, 2024

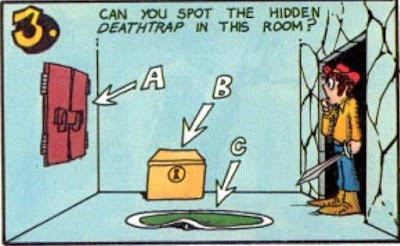

Can You Spot the Hidden Deathtrap in this Room?

While looking for the illustration of the mind flayer that appears in issue #78 (October 1983), I came across this classic bit from Phil Foglio's What's New comic. I've hidden the answer below a break.

It's a funny visual gag, but I think it's also genuinely representative of the way tricks and traps were often employed in the first decade or so of the hobby. What I mean is that, in those days, many tricks and traps were intended to test the player rather than (or in addition to) the character. Consequently, they were "gamey" in conception, more akin to brain teasers or puzzles than the kinds of things one might expect to encounter within the reality of a fantasy setting. I can recall several examples from my youth that depended on English puns or wordplay to resolve. I know my friends and I weren't alone in this.

It's a funny visual gag, but I think it's also genuinely representative of the way tricks and traps were often employed in the first decade or so of the hobby. What I mean is that, in those days, many tricks and traps were intended to test the player rather than (or in addition to) the character. Consequently, they were "gamey" in conception, more akin to brain teasers or puzzles than the kinds of things one might expect to encounter within the reality of a fantasy setting. I can recall several examples from my youth that depended on English puns or wordplay to resolve. I know my friends and I weren't alone in this.Of course, the real takeaway from this is I miss What's New ...

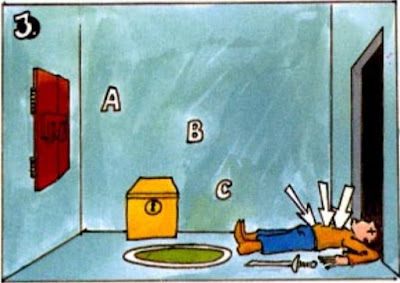

Happy 47th Birthday, Traveller!

Today is the real Traveller Day: 47 years ago, on July 22, 1977, at the third Origins Game Fair, held on Staten Island, New York, Game Designers Workshop released its science fiction roleplaying game, Traveller and the rest is history.

Today is the real Traveller Day: 47 years ago, on July 22, 1977, at the third Origins Game Fair, held on Staten Island, New York, Game Designers Workshop released its science fiction roleplaying game, Traveller and the rest is history. Though, like most people, Dungeons & Dragons was my introduction to the hobby, Traveller became (and remains) my favorite RPG and the Third Imperium my favorite imaginary setting. I didn't discover the game until around the time The Traveller Book was released in 1982 – the same year TSR released Star Frontiers and just a year before FASA released Star Trek. I played and enjoyed them all, but it was ultimately Traveller that won my heart for its simple, flexible rules and serious tone reminiscent of so many of the sci-fi books I loved.

My first professional writing credits were for Traveller when I was still in college. Through Traveller fandom, I met some of my oldest and dearest friends. And of course some of my best gaming memories relate to playing Traveller. Consequently, I'm inordinately fond of this roleplaying game and think the day of its release is every bit as worthy of celebrating as that of D&D.

Happy Birthday, Traveller! Just three more years till your golden anniversary ...

July 21, 2024

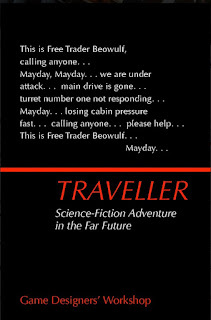

A (Very) Brief Pictorial History of Mind Flayers

The people have spoken, which means I shall continue this series for a while longer. In reviewing the suggestions offered by readers, one of the more popular ones was the mind flayer. Since this tentacled monstrosity is also my favorite Dungeons & Dragons monster, I thought it'd make sense to kick off the next round of these posts with a look at mind flayers (or illithids, as they were called in Descent into the Depths of the Earth).

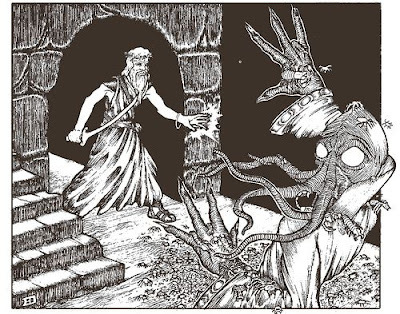

Though the mind flayer first appears in issue #1 of The Strategic Review (Spring 1975), the first illustration of it does not appear until a year later, in Supplement III, Eldritch Wizardry (1976), as drawn by Tracy Lesch. Despite how early it is, this is clearly recognizable as the monster of later depictions – a rare instance when someone other than Dave Sutherland laid the esthetic foundations upon which later artists would build.

Speaking of Dave Sutherland, here's his take on the mind flayer from the Monster Manual (1977). You can see that he was riffing off Lesch's original conception, right down to having four facial tentacles and a preference for high-collared robes of the sort favored by Ming the Merciless.

Like the kobold, the mind flayer gets two illustrations in the Monster Manual. However, this second illustration is not by Sutherland but rather by Tom Wham. Though humorous in tone, Wham's art shows a mind flayer that looks very close to its predecessors. He even includes the skull on the monster's belt. (Also of interest is that one of the illithid's victims is a halfling.)

The aforementioned Descent into the Depths of the Earth (1978) not only gives us the name illithid but also this terrific illustration (by an uncredited artist that I nevertheless think is Dave Trampier). Again, note the similarities to its predecessors.

The aforementioned Descent into the Depths of the Earth (1978) not only gives us the name illithid but also this terrific illustration (by an uncredited artist that I nevertheless think is Dave Trampier). Again, note the similarities to its predecessors.

1980 gave us several different illustrations of mind flayers, starting with this one from The Rogues Gallery by Erol Otus:

1980 gave us several different illustrations of mind flayers, starting with this one from The Rogues Gallery by Erol Otus:

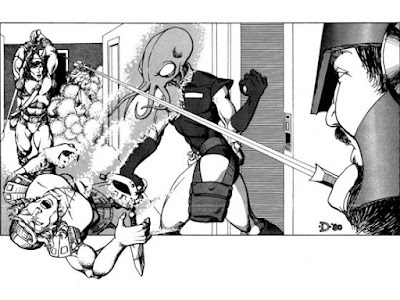

We get another, from Jeff Dee this time, in Expedition to the Barrier Peaks. It's one of my favorites of all time, probably because it's different. Rather than showing the illithid in a high-collared robe like every previous artist, Dee puts him in a sci-fi uniform, wielding technological devices – and it feel right. I can't be certain, but I suspect this illustration is the origin of the widely held notion that mind flayer are from another world (or even the future).

We get another, from Jeff Dee this time, in Expedition to the Barrier Peaks. It's one of my favorites of all time, probably because it's different. Rather than showing the illithid in a high-collared robe like every previous artist, Dee puts him in a sci-fi uniform, wielding technological devices – and it feel right. I can't be certain, but I suspect this illustration is the origin of the widely held notion that mind flayer are from another world (or even the future).

1980 also brought us the first mind flayer miniature from Grenadier Models. By most standards, it's pretty goofy looking, but you can see, if you look carefully, that it's heavily inspired by Sutherland's Monster Manual illustration. For example, the mini has similar sleeve decoration and he's wearing the same strange harness seen in the MM.

1980 also brought us the first mind flayer miniature from Grenadier Models. By most standards, it's pretty goofy looking, but you can see, if you look carefully, that it's heavily inspired by Sutherland's Monster Manual illustration. For example, the mini has similar sleeve decoration and he's wearing the same strange harness seen in the MM.

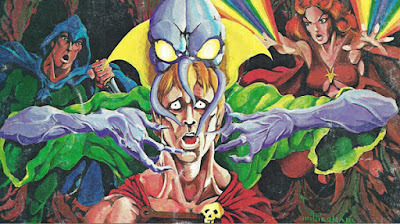

The next year, in 1981, AD&D modules D1 and D2 were combined together under a single cover, with the addition of some new art. One of those pieces of art appeared on the back cover of the module. Drawn by Bill Willingham, this is the first time we've seen a mind flayer in color.

The next year, in 1981, AD&D modules D1 and D2 were combined together under a single cover, with the addition of some new art. One of those pieces of art appeared on the back cover of the module. Drawn by Bill Willingham, this is the first time we've seen a mind flayer in color.

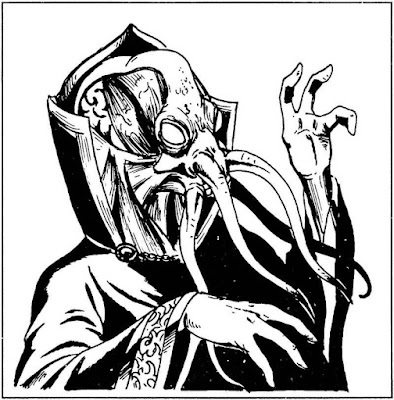

In October 1983, in issue #78 of Dragon, Roger E. Moore's "The Ecology of the Mind Flayer" appeared, accompanied by a Roger Raupp illustration. What's notable about this illustration is that the illithid is not wearing a high-collared robe, but he is wearing that harness seen in previous illustration.

In October 1983, in issue #78 of Dragon, Roger E. Moore's "The Ecology of the Mind Flayer" appeared, accompanied by a Roger Raupp illustration. What's notable about this illustration is that the illithid is not wearing a high-collared robe, but he is wearing that harness seen in previous illustration.

Citadel Miniatures briefly held the license for AD&D miniatures and produced several mind flayers in 1985, such as the one below. The high-collared robe returns once more.

Citadel Miniatures briefly held the license for AD&D miniatures and produced several mind flayers in 1985, such as the one below. The high-collared robe returns once more.

By 1987, the license passed to Ral Partha. The company held the license for almost a decade and, during that time, they produced this mind flayer miniature:

By 1987, the license passed to Ral Partha. The company held the license for almost a decade and, during that time, they produced this mind flayer miniature:

I don't know precisely when this mini was produced, so, if anyone knows, please let me know in the comments. This is important for a reason that will become apparent shortly.

I don't know precisely when this mini was produced, so, if anyone knows, please let me know in the comments. This is important for a reason that will become apparent shortly.For the 1989 Second Edition Monstrous Compendium , we get an illustration from James Holloway. Though some of the details are different – notice the brain you can see inside the mind flayer's head – but it's still not far from what we've seen many times before, including the high-collared robe.

Finally, there's 1993's Monstrous Manual whose depiction was done by Tony DiTerlizzi.

Finally, there's 1993's Monstrous Manual whose depiction was done by Tony DiTerlizzi.

The illustration looks just like the Ral Partha mini above – unless it's the other way around. That's why I'm curious about when the miniature was released. My suspicion is that the DiTerlizzi illustration came first, but I cannot prove it.

With that, we come to the end of my brief look at mind flayer artwork from the TSR era of Dungeons & Dragons. I know I've probably overlooked a lot of illithid illustrations from Second Edition, like the one on the cover of Spelljammer, but I've already presented enough, I think, to give a good sense of how these monsters were presented during the first two decades of D&D. However, if you can recall any illustrations of mind flayers you think are especially worthy of comment, let me know.

July 19, 2024

REVIEW: The Lair of the Brain Eaters

The first few years of the Old School Renaissance were marked by a renewed appreciation not just of early roleplaying games but also of the pulp fantasy stories that inspired them. This was the time when Appendix N of Gary Gygax's AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide became a frequent topic of discussion on blogs and forums, much to the satisfaction of those of us who felt a strong injection of sword-and-sorcery was the perfect antidote to what we felt was an increasingly video-gamified hobby (remember: this coincided with the release of D&D Fourth Edition) that had lost sight of its literary roots.

The first few years of the Old School Renaissance were marked by a renewed appreciation not just of early roleplaying games but also of the pulp fantasy stories that inspired them. This was the time when Appendix N of Gary Gygax's AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide became a frequent topic of discussion on blogs and forums, much to the satisfaction of those of us who felt a strong injection of sword-and-sorcery was the perfect antidote to what we felt was an increasingly video-gamified hobby (remember: this coincided with the release of D&D Fourth Edition) that had lost sight of its literary roots.This is the backdrop against which many of the earliest D&D retro-clones – emulations of earlier editions – appeared, including Lamentations of the Flame Princess. Calling itself a "weird fantasy role-playing game," LotFP took seriously the goal of bringing more pulp fantasy-inspired content into fantasy gaming, especially in its adventures, which quickly gained a reputation for being, by turns, imaginative, grotesque, challenging, deadly, and prurient – among many other extravagant adjectives.

However, as LotFP's creator, James Raggi, found his strange Muse, its adventures moved away from generic pulp fantasy scenarios of the sort one might have found in Weird Tales during the Golden Age of the pulps and toward a weirder, even more brutal version of Earth's 17th century. This new focus on historical fantasy helped LotFP distinguish itself from its fellow retro-clones, but it also, I think, narrowed its appeal somewhat, since most fantasy gamers, old school or otherwise, are looking for adventures they can easily drop into campaign settings other than Earth during the 1600s.

While I am a big fan of LotFP's pivot to historical fantasy, I miss the ahistorical strangeness of stuff like Death Frost Doom , Hammers of the God , or The Monolith from Beyond Space and Time. Consequently, when I learned about D.M. Ritzlin's The Lair of the Brain Eaters , I was intrigued. Unlike most recent LotFP releases, this adventure didn't seem to be set in the 17th century. Rather, it seemed more like something from Robert E. Howard's Hyborian Age or perhaps Clark Ashton Smith's Hyperborea – a lurid, necromantic pulp fantasy scenario of the kind we haven't seen for LotFP in a while.

That should come as no surprise. Ritzlin is the proprietor of DMR Books, a small press dedicated "fantasy, horror, and adventure fiction in the traditions Robert E. Howard, H.P. Lovecraft, and other classic writers of the pulp era." Indeed, The Lair of the Brain Eaters shares its title with a short story Ritzlin wrote for the collection, Necromancy in Nilztiria . According to the author, some of the story's details have been changed (and "a great many more have been added"), so this adventure is less directly adapted and more inspired by its source. Even so, it's quite unusual by the standards of contemporary Lamentations of the Flame Princess.

The adventure concerns a cult dedicated to the consumption of human brains. Called the Yoinog – supposedly an ancient term meaning "knowledge seekers" – the cult serves the necromancer Obb Nyreb, furnishing him with a fresh supply of corpses as he attempts to unravel the mysteries of Veshakul-a, the goddess of death. Nyreb and the Yoinog have established themselves in a network of caves beneath a graveyard of the city of Desazu. Unfortunately, in their zeal for graverobbing, the cult has drawn attention to their master's activities, thereby providing an opening for the player characters to involve themselves in the adventure.

The Lair of the Brain Eaters is short and to the point. The cult's cave network consists of only twenty keyed areas, with Nyreb's chambers occupying an additional nine. Most of them are described briefly, with little in the way of extraneous detail. Do not, however, mistake its comparatively spartan descriptions for a sparseness of ideas – quite the contrary. The florid prose of many adventures is often chalked up to the designer's desire to be a writer of fiction. Here, the opposite is the case: the text's concision signals that its designer is already a skilled fictioneer and understands well that less can be more.

For example, this is part of the description of a "bottomless pit": "This pit is not really bottomless, but it amused Obb Nyreb to tell the Yoinog it was, and they never doubt him." Elsewhere, a kitchen is described thusly: "Grimy pots, pans, and plates litter the floor. A cauldron large enough to contain a man sits in the center of the room, while smaller ones dangle from the ceiling." Speaking as someone whose personal style tends toward the aureate, I admire Ritzlin's ability to convey description, vital information, and mood through so few words. This approach also makes the descriptions easy to use at a glance, which is very helpful in play.

Designed for character levels 1–3, The Lair of the Brain Eaters is challenging. There are a lot of Yoinog within the caves, as well as other creatures, such as the apelike Skullfaces and mutant rats (some of which breathe fire – yes, it's a bit silly, but so what?). Fortunately, the caves contain lots of opportunities for the characters to act stealthily or otherwise use the environment to their advantage. In addition, there's a captive within who, if freed, can aid the characters in navigating the place. These factors, combined with some clever tricks and obstacles, creates a memorable locale for both exploration and combat.

The Lair of the Brain Eaters is an inventive, evocative, and unpretentious "meat and potatoes" adventure that I'd like to see more of – from Lamentations of the Flame Princess or any other publisher. I think it'd be an especially great fit for anyone playing North Wind's Hyperborea RPG, but it'd work just as well with any other fantasy game that draws inspiration from the pulps. I really enjoyed this one.

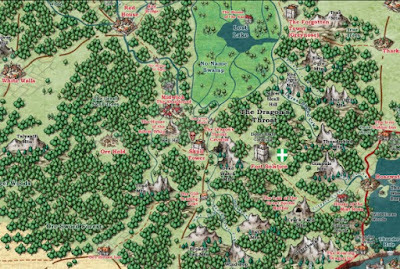

Arduin Map Collection

Dave Hargrave's The Arduin Grimoire (1977) and its two immediate sequels, Welcome to Skull Tower and The Runes of Doom (1978), are important artifacts from the first few years of the hobby of roleplaying and thus of great interest to all fans of old school gaming. These three books, often known collectively as The Arduin Trilogy, were not just mere flights of fancy by their creator, but outgrowths of Hargrave's home-brewed fantasy roleplaying game campaign, among whose hundreds of players was none other than Greg Stafford of RuneQuest fame. The Trilogy not only delighted many roleplayers during the '70s, but also included some of the earliest published artwork of Erol Otus.

Dave Hargrave's The Arduin Grimoire (1977) and its two immediate sequels, Welcome to Skull Tower and The Runes of Doom (1978), are important artifacts from the first few years of the hobby of roleplaying and thus of great interest to all fans of old school gaming. These three books, often known collectively as The Arduin Trilogy, were not just mere flights of fancy by their creator, but outgrowths of Hargrave's home-brewed fantasy roleplaying game campaign, among whose hundreds of players was none other than Greg Stafford of RuneQuest fame. The Trilogy not only delighted many roleplayers during the '70s, but also included some of the earliest published artwork of Erol Otus.Emperor's Choice Games, the current publisher and rights holder of Arduin, has big plans for Dave Hargrave's legacy, starting with the release of a large collection of maps based on those he made for his RPG campaign almost a half-century ago. These maps include not only the titular County of Arduin (an earlier version of which I positively reviewed fifteen years ago), but also maps of the continent of Khaora in which it is situated and the country of Chorynth as well. The new County of Arduin map is gorgeous and filled with lots of interesting and useful details.

If you're a fan of Arduin or just a lover of fantasy maps, please take a look.

Gamescience?

Can anyone recommend a reliable source of Gamescience precision polyhedral dice? They seem very difficult to find these days. Gamescience seems to maintain a website, but, based on its appearance, I'm not convinced it's still active. More to the point, the selection available there is quite limited.

Can anyone recommend a reliable source of Gamescience precision polyhedral dice? They seem very difficult to find these days. Gamescience seems to maintain a website, but, based on its appearance, I'm not convinced it's still active. More to the point, the selection available there is quite limited. Alternately, are there any other manufacturers who make dice of similar appearance and quality? I'm not wedded to Gamescience as such. However, I don't like dice with rounded edges and most dice these days seem to be in that style. I'd happily acquire precision dice from another source if I knew of one.

Any suggestions?

July 18, 2024

From the Sorceror's [sic] Scroll

Way back in issue #11 of Dragon (December 1977), a new column appeared entitled "From the Sorcerer's Scroll." This was the image that accompanied the first appearance of the column.

The first three columns were penned by Rob Kuntz. With issue #14 (May 1978), Gary Gygax took over the column and a new image accompanied it.

The first three columns were penned by Rob Kuntz. With issue #14 (May 1978), Gary Gygax took over the column and a new image accompanied it.

Interestingly, the table of contents to issue #14 includes this:

Interestingly, the table of contents to issue #14 includes this:

In case the image above is too small to read, the title of Gygax's column is called "Sorceror's [sic] Scroll." That's a misspelling, albeit a very common one. In the next issue, the table of contents spells the word "sorcerer" correctly. However, in issue #18 (September 1978), the misspelling returns – before being fixed again in issue #19 (October 1978). However, the misspelling returns again in issue #23 (March 1979) and remains. The situation gets worse in issue #30 (October 1979), when the column gets new art.

In case the image above is too small to read, the title of Gygax's column is called "Sorceror's [sic] Scroll." That's a misspelling, albeit a very common one. In the next issue, the table of contents spells the word "sorcerer" correctly. However, in issue #18 (September 1978), the misspelling returns – before being fixed again in issue #19 (October 1978). However, the misspelling returns again in issue #23 (March 1979) and remains. The situation gets worse in issue #30 (October 1979), when the column gets new art.

Unlike the previous two bits of accompanying art, which spelled sorcerer correctly even when the table of contents was in error, the appearance of new art enshrines the misspelling permanently. You can even see it in the next iteration of the column's art, from issue #68 (December 1982).

Unlike the previous two bits of accompanying art, which spelled sorcerer correctly even when the table of contents was in error, the appearance of new art enshrines the misspelling permanently. You can even see it in the next iteration of the column's art, from issue #68 (December 1982).

I'm admittedly a stickler for correct spelling, so maybe I'm more sensitive to this sort of thing than are most people. Even so, "sorceror" is a pretty egregious misspelling, all the more so when it's clear that someone working on Dragon knew the correct spelling and would make adjustments to the table of contents when he saw the error. Interestingly, the magic-user level title of "sorcerer" is consistently spelled correctly throughout the history of Dungeons & Dragons, even in OD&D, which is notorious for its misspellings, typos, and other orthographical blunders. This makes me wonder what was going in the editorial offices of Dragon.

I'm admittedly a stickler for correct spelling, so maybe I'm more sensitive to this sort of thing than are most people. Even so, "sorceror" is a pretty egregious misspelling, all the more so when it's clear that someone working on Dragon knew the correct spelling and would make adjustments to the table of contents when he saw the error. Interestingly, the magic-user level title of "sorcerer" is consistently spelled correctly throughout the history of Dungeons & Dragons, even in OD&D, which is notorious for its misspellings, typos, and other orthographical blunders. This makes me wonder what was going in the editorial offices of Dragon.

July 17, 2024

The Bad News Bugbears

While perusing issue #60 of Dragon (April 1982), I stumbled across yet another image of a bugbear I should have brought to your attention. This one appears in an April Fool's edition of the "Dragon Bestiary" with art by (I think) Jim Holloway.

July 16, 2024

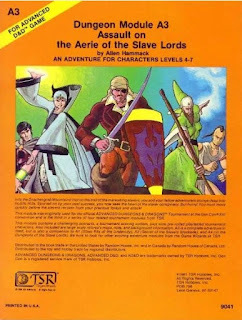

Retrospective: Assault on the Aerie of the Slave Lords

Since I've already done Retrospective posts about the first, second, and fourth modules in the "Slave Lords" series, I thought it only proper that I should finally do one on the third, Assault on the Aerie of the Slave Lords. Written by Allen Hammack (best known for

The Ghost Tower of Inverness

) and released in 1981, module A3 is probably my least favorite of the four, perhaps because it reveals its origins as a tournament module even more obviously than do the others in the series. So much of its content and structure is contrived to test the skills of its players that it feels obviously artificial. That's a shame, because there are some genuinely good ideas here that, presented differently, might have been more successful.

Since I've already done Retrospective posts about the first, second, and fourth modules in the "Slave Lords" series, I thought it only proper that I should finally do one on the third, Assault on the Aerie of the Slave Lords. Written by Allen Hammack (best known for

The Ghost Tower of Inverness

) and released in 1981, module A3 is probably my least favorite of the four, perhaps because it reveals its origins as a tournament module even more obviously than do the others in the series. So much of its content and structure is contrived to test the skills of its players that it feels obviously artificial. That's a shame, because there are some genuinely good ideas here that, presented differently, might have been more successful. Having destroyed a caravan fort of the slavers in the previous module, the characters are now investigating a hidden mountain city reputed to serve as one of their main bases of operation. Reaching the city first requires a trek through cave tunnels to find its entrance. Once there, the characters must then descend into its sewers to locate the council chamber of the slave lords. Only at this point can they face off against them and hope to put an end to their depredations.

If all that sounds convoluted, even improbable and tedious, you're right. There's a reason I called this module contrived. It's presented as a series of gauntlets – make it through the caves to find the city; through the city to find the sewers, etc. – the characters must run, each one filled not only with a lot of enemies but also with tricks and traps of all kinds. This probably works really well in a tournament, where each gauntlet is part of a different round of play, but, as a module to be used in campaign play, it leaves a lot to be desired.

The situation is made worse, I think, by the fact each section includes elements that strain credibility. For example, the mountain "caves" the characters must navigate to reach the city are actually a mazelike series of worked stone corridors. The slave lords clearly went to a lot of trouble to make them and then fill them with monsters and traps. The "city" of Suderham that serves as their base is really quite small (about 70 locations), a great many of which are taverns and "houses of ill repute." The referee is encouraged to flesh it out more fully, based on some limited details provided in the module. Perhaps that's enough, given its purpose here, but I find myself wishing for more. Almost nothing in this module feels naturalistic to me. Instead, it's all here to support a tournament experience and it shows.

Worst of all is the ending. Because this is the penultimate module in the series, the characters clearly cannot defeat the slave lords once and for all. Likewise, the next and final module in the series, begins with the characters defeated, stripped of their equipment, and thrown into a dungeon from which they must escape. Consequently, the module provides numerous ways to ensure that, no matter what else happens, the characters are captured so that they be thrown into said dungeon. I fully understand why this is the case, especially in a tournament situation, but it's deeply unsatisfying nonetheless.

Despite all of my complaints, there's still a lot to like here. Suderham, while smaller and less detailed than I'd have wanted, has potential, given its location in a volcanic crater and nefarious character – a pity that it's unceremoniously destroyed in the next module. Likewise, the idea of exploring the sewers and encountering weird monsters, like a killer mimic and a crossbow-wielding minotaur, is great, even if its execution leaves something to be desired. Then there's the art by TSR's stable of Electrum Age artists like Jeff Dee, Bill Willingham, and Erol Otus, most of which is quite good and probably deserving a post of its own. Such a shame they weren't put to better use!

Speaking of halflings ...

Speaking of halflings ...

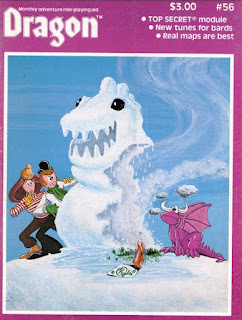

The Articles of Dragon: "Singing a New Tune"

In starting this new iteration of The Articles of Dragon, I struggled a bit with deciding when to begin. The very first issue of Dragon I remember buying for myself – from Waldenbooks, no less – was issue #62, which features a phenomenal cover painting by Larry Elmore. However, I'd been reading the magazine for a few months prior to that purchase, largely thanks my friend's older brother, who acted as one of our gaming mentors. He had a collection of Dragon issues and we'd often sneak into his basement bedroom to read them when he was out of the house.

In starting this new iteration of The Articles of Dragon, I struggled a bit with deciding when to begin. The very first issue of Dragon I remember buying for myself – from Waldenbooks, no less – was issue #62, which features a phenomenal cover painting by Larry Elmore. However, I'd been reading the magazine for a few months prior to that purchase, largely thanks my friend's older brother, who acted as one of our gaming mentors. He had a collection of Dragon issues and we'd often sneak into his basement bedroom to read them when he was out of the house. Issue #56 (December 1981), with its memorable Phil Foglio cover, was among the issues in that collection and is thus the first Dragon magazine I ever read. It's not a great issue, at least in comparison to many of those that followed, but it has two articles in it that I remember quite vividly, the first of which I decided would be the first entry in this new series, whose purpose, after all, is to use old Dragon articles as an occasion to share memories of my early days in the hobby.

Written by Jeff Goelz, "Singing a New Tune" offers up "a different bard, not quite so hard" for use with Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. AD&D's bard, as presented in the Players Handbook, is a bizarre and unprecedented multi-class/split class thing. A prospective bard begins play as a fighter. Then, after achieving a level between 5 and 7, he takes up thievery. He then abandons the thief class sometime between 5th and 9th level and becomes a bard proper. Why Gygax opted for this scheme is unclear, since Doug Schwegman's original bard class from Strategic Review, Vol. 2, issue 1 (September 1976) is a straightforward class without multiclassing. So different is this class than any other in the game that it's stuck in an appendix at the end of the PHB.

In his article, Goelz proposes to return bards to something closer to what was seen in the Strategic Review, albeit with numerous tweaks of his own. He begins with an amusing exchange between a DM and two half-orc NPCs, in which they discuss bards.

I was so taken with this dialog that, all these years later, I can still quote sections of it from memory. The idea of a Dungeon Master chatting with two non-player characters, who call him "boss," is quite funny to me for some reason. The dialog also serves the purpose of pointing out the problems with both previous versions of the bard class.

I was so taken with this dialog that, all these years later, I can still quote sections of it from memory. The idea of a Dungeon Master chatting with two non-player characters, who call him "boss," is quite funny to me for some reason. The dialog also serves the purpose of pointing out the problems with both previous versions of the bard class.Goelz opted for a middle road between a wholesale rewriting of the class and a simple reworking of what had come before. He looked to the Welsh bard, both historical and mythical, for inspiration, using it as a guide for what aspects of previous bard classes to retain, to omit, or to alter. The result is, in my opinion, pretty good – simpler, more playable, and with a power level that's comparable to the other AD&D classes. Most importantly, Goelz's bard has a clear niche for itself as a loremaster with strong social skills and a smattering of druid and illusionist spells.

That list bit is important, because I think the real judge of whether the existence of a class is justified is its role within the game. Both previous versions of the bard were very broad classes with a wide range of skills and abilities that stepped on the toes of several other classes. This new one is much more unique, carving out a specific role that is not clearly served by any other class. That it's also mechanically less onerous is another point in its favor. That's why I was quite taken with it when I first read this article more than forty years ago.

At the same time, I've never been a huge fan of any version of the bard class. The bard has always felt weirdly specific – Goelz's version especially so – in much the same way that the monk did. In some campaign settings, a bard is perfectly reasonable and appropriate, while in others it would stick out like a sore thumb. My dislike is also probably a function of the people I've know who are boosters of the class: flamboyant, theatrical types with a penchant for extemporaneous poetry and song. I readily admit this is a me problem, not a bard problem as such, but it's there nonetheless. That's why I cannot recall the last time I've permitted a bard in any of my D&D campaigns. Were I to do so, however, I wouldn't hesitate to use the version in this article (or some variation thereof).

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers