James Maliszewski's Blog, page 46

August 18, 2024

Level Titles: Assassins and Monks

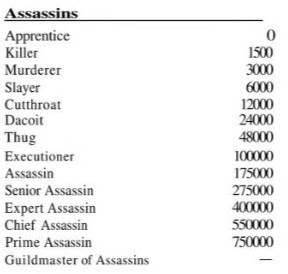

To continue with our discussion of level titles in Dungeons & Dragons, I thought it might be worthwhile to take a look at two classes that first appeared in Supplement II to OD&D, Blackmoor (1975), and later in the Advanced D&D Players Handbook (1978) – assassins and monks. Here are the level titles of the former, as they were in Blackmoor:

As with most level titles, these are all mostly synonyms, with a few exceptions, the first being "dacoit," which is an archaic term that, like "thug," ultimately derives from India. Another notable exception is "guildmaster of assassins," which suggests, like the titles immediately before it, that there's some kind of organized structure granting these titles to assassins as they gain experience. The text of Supplement II more or less states this: "Any 12th level assassin (Prime Assassin) may challenge the Guildmaster of the Assassins' Guild to a duel to the death, and if the former is victorious he becomes Guildmaster." This suggests there's a single Assassins' Guild rather several, as seems to be the case with thieves.

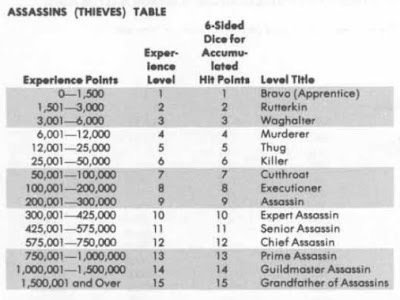

Regardless, the assassin level titles in the Players Handbook are somewhat different:

While many of the low-level titles are identical to those in Blackmoor, their arrangement is changed. In addition, Gygax indulged in his fondness for odd archaisms, like rutterkin and waghalter, while getting rid of "dacoit." Interestingly, he added a new title above "guildmaster assassin," namely, "grandfather of assassins," for reasons both historical and practical.

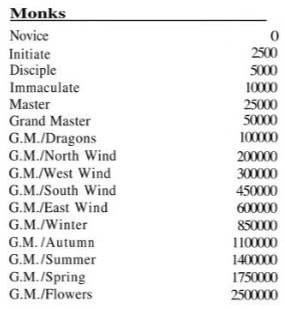

While many of the low-level titles are identical to those in Blackmoor, their arrangement is changed. In addition, Gygax indulged in his fondness for odd archaisms, like rutterkin and waghalter, while getting rid of "dacoit." Interestingly, he added a new title above "guildmaster assassin," namely, "grandfather of assassins," for reasons both historical and practical.Monks offer an intriguing parallel to assassins, because, like them, their level titles suggest the existence of a single organization that governs them and thus grants these titles. Likewise, above a certain point, the granting of these titles is tied to success in combat against the previous holder of the title, perhaps inspired by martial arts trials. The OD&D level titles are:

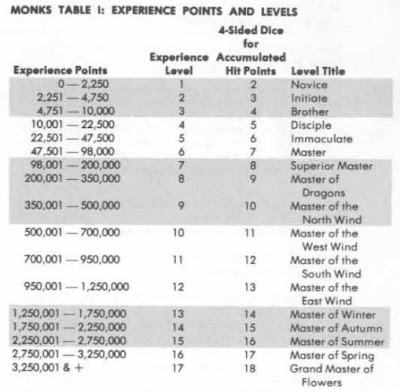

In the AD&D Players Handbook, we get this version of them:

In the AD&D Players Handbook, we get this version of them:

The AD&D list differs only in inserting an additional level and reserving the title "grand master," as opposed to simply "master" for the highest level. Otherwise, the two lists are almost identical, even down to the progression order of the various master titles (Dragons, North Wind, West Wind, etc.). I find that interesting, but I'm unsure what conclusions, if any, we can draw from these facts. It's also worth noting that, according to some sources, the "master" titles were inspired by the names of mahjong tiles, which seems plausible, given how wide were the interests in games of men like Arneson and Gygax.

The AD&D list differs only in inserting an additional level and reserving the title "grand master," as opposed to simply "master" for the highest level. Otherwise, the two lists are almost identical, even down to the progression order of the various master titles (Dragons, North Wind, West Wind, etc.). I find that interesting, but I'm unsure what conclusions, if any, we can draw from these facts. It's also worth noting that, according to some sources, the "master" titles were inspired by the names of mahjong tiles, which seems plausible, given how wide were the interests in games of men like Arneson and Gygax.

August 16, 2024

"You're a Player of Role-Playing Games"

Following up on yesterday's post about the "Appendix N" of Temple of Apshai, let's look at the paragraphs that follow, because, in many ways, they're even more interesting. After asking the reader whether he was familiar with any of stories, books, and characters cited, the game's introduction then declares:

If any or all of your answers are "yes," you're a player of role-playing games – or you ought to be. (If your answers are all "no," you have either stepped through the looking glass by mistake, or fate knows your destiny better than you.)

As I said, interesting. In particular, I think it's notable that the writer (Jon Freeman) saw an almost necessary connection between being familiar with fantasy literature and being a player of RPGs – as if you can't be one without also being the other. He continues:

Role-playing games (RPGs) allows you to step outside a world grown too prosaic for magic and monsters, doomed cities and damsels in distress ... and enter instead a universe in which only quick wit, the strength of your sword arm, and a strangely carved talisman around your neck may be the only things separating you from the pharaoh's treasure – or the mandibles of a giant mantis.

The standard (non-computer) role-playing game is not, in its commercial incarnation, much more than a rulebook – a set of guidelines a person uses to create a world colored by myth and legend, populated by brawny heroes, skilled swordsmen, skulking thieves, cunning wizards, hardy Amazons, and comely wenches, and filled with treasures, spell-forged blades, flying carpets, rings of power, loathsome beasts, dark towers, and cities that stood in the Thousand Nights and a Night if not The Outline of History.

Freeman writes very evocatively, doesn't he? Old school RPG fans will also, no doubt, approve of his description of a rulebook as "a set of guidelines."

Role-playing games are not so much "played" as they are experienced. Instead of manipulating an army of chessman about an abstract but visible board, or following a single piece around and around a well-defined track, collecting $200 every time you pass GO, in RPGs you venture into an essentially unknown world with a single piece – your alter ego for the game, a character at home in a world of demons and darkness, dragons and dwarves. You see with the eyes of your character a scene described by the "author" of the adventure – and no more.

Again, evocative stuff. Reading this, you can really tell that Freeman is passionate about the then-new hobby of roleplaying games.

There is no board in view, no chance squares to inspect; the imaginary landscape exists only in the notebooks of the world's creator (commonly called a referee or dunjonmaster) and, gradually, in the imaginations of your fellow players. As you set off in quest of fame and fortune with with those other player/characters, you are both a character in and a reader of an epic you are helping to create. Your character does whatever you wish him to do, subject to his human (or near-human) capabilities and the vagaries of chance. Fight, flee, or parley; take the high road or low; the choice is yours. You may climb a mountain or go around it, but since at the top may be a rock, a roc's egg, or a roc, you can find challenge and conflict without fighting with your fellow players, who are usually (in several senses) in the same boat.

This is very good stuff and, if I may, very much in keeping with the philosophy of gaming that's been championed in the Old School scene over the last fifteen years or so.

Role-playing games can (and often do) become, both for you and your character, a way of life. Your character does not stop existing at the end of a game session; normally, you use the same character again and again until he dies for a final time and cannot be brought back to life by even the sorcerous means typically available. In the meantime, he will have grown richer on the treasure he (you) has accumulated from adventure ro adventure, may have purchased new and better equipment, won magic weapons to help him fight better or protective devices to keep him safe. As he gains experience from his adventures, he grows in power, strength, and skill – although the mechanics and terminology of this process vary greatly from one set of rules to another.

The remainder of Freeman's introduction pertains mostly to the ways that Temple of Apshai alleviates some of the burden typically placed on the shoulders of players and referee alike, which is understandable, as part of his purpose is to demonstrate the value of computer RPGs over "standard" ones. Even so, what he says about roleplaying games – in 1979, please recall – still holds interest more than four decades later, especially to those of who prefer the "old ways." Indeed, I think it's all the more interesting when ones considers where this introduction appeared and who its intended audience was.

Temple of Apshai's Appendix N?

Here's the opening paragraph to introduction of the user manual from 1979's Temple of Apshai. This section was reprinted verbatim in the manual to The Temple of Apshai Trilogy six years later.

Did you grow up in the company of the Brothers Grimm, Snow White, The Red Fairy Book, The Flash Gordon serials, The Three Musketeers, the knights of the Round Table, or any of the three versions of The Thief of Baghdad? Have you read The Lord of the Rings, The Worm Ouroboros, The Incomplete Enchanter, or Conan the Conqueror? Have you ever wished you could cross swords – just for fun – with Cyrano or D'Artagnan, or stand by their sides in the chill light of dawn, awaiting the arrival of the Cardinal's Guard? Ever wondered how you'd have done against the Gorgon, the Hydra, the bane of Heorot Hall, or the bull that walks like a man? Would you have sailed with Sinbad or Captain Blood, sought passage on the ship of Ishtar, or drunk of the Well at World's End? Did Aphrodite make Paris an offer you couldn't refuse? Would you seek a red-hued maiden beneath the hurtling moons of Barsoom, or walk the glory road with "Dr. Balsamo," knowing it might be a one-way street?

Written by Jon Freeman, co-designer of the game, this paragraph is filled with literary references that it could almost be taken as the Appendix N of Temple of Apshai. I say "almost," because the paragraph is not meant to describe the specific influences upon the game itself so much as to describe the kinds of stories, books, and characters that might serve as introductions both to fantasy as a genre and to fantasy roleplaying. In that respect, it's less useful in understanding Temple of Apshai than it is in understanding what, in 1979, might have been considered the "must reads" of fantasy – and the kinds of literature that had served as the seed beds of roleplaying.

August 15, 2024

Level Titles: Clerics and Magic-Users

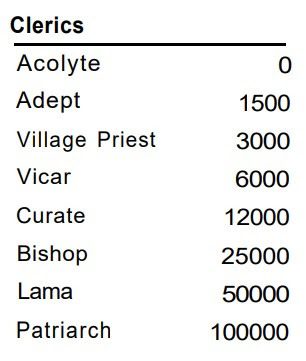

Yesterday, we looked at the level titles of fighters and thieves, so today we'll turn to the level titles of clerics and magic-users. These are a bit more interesting, in that there's more variability between the different editions of Dungeons & Dragons. In OD&D (1974), clerics have the following level titles:

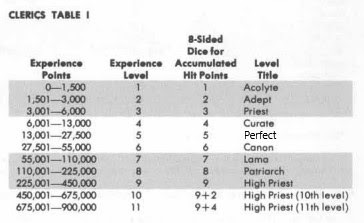

In the AD&D Players Handbook (1978), we get a similar but not identical list. Levels 1 and 2 are the same, while level 3 is simply "priest" rather than "village priest." The title of "curate" becomes a level 4 title and "vicar" disappears entirely, replaced by "perfect," which may or may not be a misspelling of "prefect." "Bishop" is replaced with "canon" and there's a title above patriarch – high priest.

In the AD&D Players Handbook (1978), we get a similar but not identical list. Levels 1 and 2 are the same, while level 3 is simply "priest" rather than "village priest." The title of "curate" becomes a level 4 title and "vicar" disappears entirely, replaced by "perfect," which may or may not be a misspelling of "prefect." "Bishop" is replaced with "canon" and there's a title above patriarch – high priest.

The 1981 Expert Rules has yet another set of level titles, one that is fairly close to that of OD&D and yet still distinct. There's a new title, elder, that's placed in between curate and bishop, making the latter a 7th-level title rather than a 6th-level one in OD&D.

The strangest thing about all the lists of clerical level titles is how, for the most part, they're all derived from the names of Christian clergy, which says a lot about the origins of the cleric class. The anomalous titles are "adept," which strikes me as being more appropriate to a magic-user of some kind and "lama," which, while religious in character, has nothing to do with Christianity. Why these were both included in the list, I have no idea.

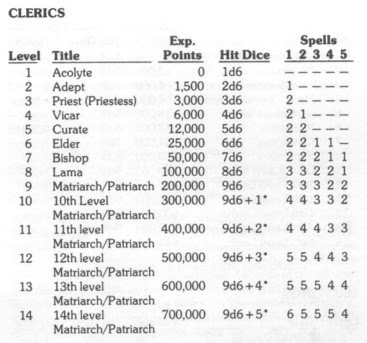

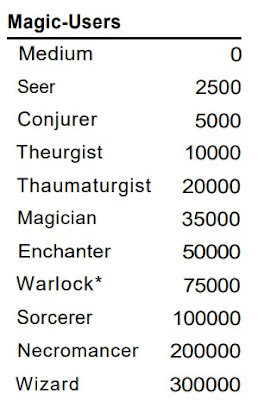

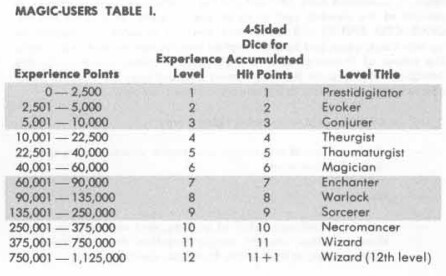

Turning to magic-users, we get this list in OD&D:

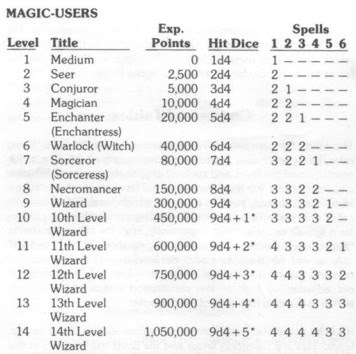

AD&D has a similar list, starting at level 3. The first two AD&D level titles are quite different and the titles that were replaced appear nowhere else on the list. They're simply removed.

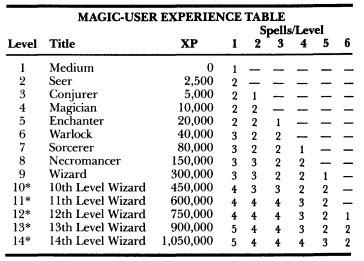

The Expert Rules give us yet another list. "Medium" and "seer" are restored to level 1 and 2, while "theurgist" and "thaumaturgist" are both removed entirely, much as "medium" and "seer" were in AD&D. The OD&D level titles that followed, starting with "magician" simply drop down several levels, perhaps so that "wizard" can now be the 9th-level rather than 11th-level title, since the 1981 edition places a great emphasis on level 9 being "name" level for the four human classes. Also of note is that the 1981 rules spell "conjurer" and "sorcerer" as "conjuror" and "sorceror," despite neither OD&D nor AD&D spelling them that way.

The Expert Rules give us yet another list. "Medium" and "seer" are restored to level 1 and 2, while "theurgist" and "thaumaturgist" are both removed entirely, much as "medium" and "seer" were in AD&D. The OD&D level titles that followed, starting with "magician" simply drop down several levels, perhaps so that "wizard" can now be the 9th-level rather than 11th-level title, since the 1981 edition places a great emphasis on level 9 being "name" level for the four human classes. Also of note is that the 1981 rules spell "conjurer" and "sorcerer" as "conjuror" and "sorceror," despite neither OD&D nor AD&D spelling them that way.

Normally, the 1983 Frank Mentzer-edited edition of D&D follows its 1981 predecessor quite closely, but there are some differences worthy of note. In the case of magic-user level titles, it's worth noting that '83 restores the "–er" endings of both "conjurer" and "sorcerer," while everything else remains the same.

I find these changes quite fascinating, but I wish I knew precisely why they were made. I have theories but no proof and I suspect, even if I were to hunt down the people responsible for doing so, they would not remember after so many decades.

Gradually, then Suddenly

It's been a rough few weeks for my ongoing House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign. Recently, the combination of the usual summer doldrums I've come to expect over the last nine years with the vagaries of my players' real-life schedules and obligations has resulted in fewer sessions where we actually play than those where we just chat. Now, there's nothing wrong with chatting with one's friends and, truth be told, I often enjoy those sessions where we shoot the breeze rather than roleplay. But House of Worms is a roleplaying game campaign, so I do take note of when we have an extended period of time when our playing is erratic to non-existent, as has been the case for the last month or so.

It's been a rough few weeks for my ongoing House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign. Recently, the combination of the usual summer doldrums I've come to expect over the last nine years with the vagaries of my players' real-life schedules and obligations has resulted in fewer sessions where we actually play than those where we just chat. Now, there's nothing wrong with chatting with one's friends and, truth be told, I often enjoy those sessions where we shoot the breeze rather than roleplay. But House of Worms is a roleplaying game campaign, so I do take note of when we have an extended period of time when our playing is erratic to non-existent, as has been the case for the last month or so.As it happens, one of my players also has taken note of it and today raised the question of whether or not I thought the campaign was in danger of sputtering out. Despite my optimism of only a few months ago, I had to agree that the campaign might indeed be entering its final days. Amusingly, our newest player, who only joined our merry band in January of this year, joked that he should have known this would happen. Anytime he'd joined a Tékumel campaign in the past, it fell apart soon thereafter, so why should House of Worms be any different? One of the original six players of the campaign hasn't been able to join us since earlier this year, while another of the original six is now taking an extended leave due to his work. Other players have also found themselves unable to attend for various reasons and that's had an adverse effect on our sessions, which, in turn, has slowed the momentum of the campaign to the point where the players are now openly discussing the possibility of things coming to a halt.

As I said during today's session, when the question was first raised, we've had periods like this before, when our session frequency became inconsistent and we lost some momentum, but we always managed to keep things going somehow, so that might well be the case this time as well. However, I must confess that this time feels a little different. If I had to put my finger on why it's probably related to the loss of two of the original six players. We're entering into Ship of Theseus territory, where the thread connecting the first session in March 2015 and the present is getting ever more tenuous. Maybe that's not what's going on, I don't know. I can only say that I agreed with the player that lately House of Worms feels as if it's no longer as energetic as it once was.

Of course, the reason the player brought the topic up was, in part, to see if we could make an effort to "wrap things up," which is to say, reach a place in the campaign where, if we were to decide to end it, doing so would bring some degree of satisfaction. Given the meandering nature of the campaign after nearly a decade of play, I'm not sure it'd be possible, even under the best of circumstances, to tie up all the dangling threads into a neat little bow, but, even if that's impossible, there's no reason we shouldn't work toward some kind of closure. We've spent too much time with these characters, this world, and one another not to try – which is why, in today's session, the characters began to lay the groundwork not only to effect Kirktá's rise to emperor of Tsolyánu but also to ruler of a restored Bednallján Empire. They think big, don't they?

And who knows: thinking big might just be the sort of thing that helps pull the campaign out of its doldrums and ensures our contemplation of its end is for nothing.

August 14, 2024

Level Titles: Fighters and Thieves

Level titles first appeared in original (1974) Dungeons & Dragons, seemingly inspired by the various types of figures available in the "Fantasy Supplement" to Chainmail (1971), about which I may make a separate post later. These titles, in themselves, have no mechanical purpose whatsoever, serving solely as a verbal way to distinguish between two characters of the same class but of different levels. Consequently, they disappeared entirely from AD&D's Second Edition (1989), but were present in all editions of D&D until the Rules Cyclopedia (1991), when they disappeared (though they did reappear in the brief and often forgotten The Classic Dungeons & Dragons Game in 1994).

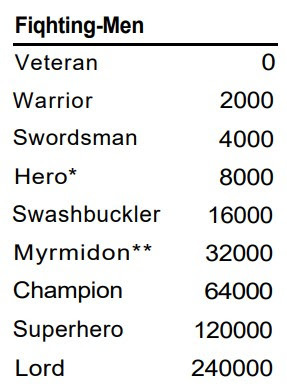

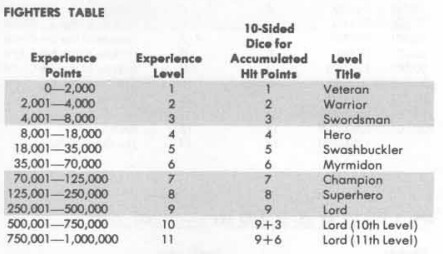

Since I've lately become very interested in the degree of continuity between the various editions of D&D, I thought looking at the level titles of the various classes might make for an interesting series of posts. To start, let's look at fighters (fighting men) and thieves. Here's the level title chart for the former from Volume 1 of OD&D:

In the AD&D Players Handbook (1977), the list is identical.

However, in the 1981 David Cook/Stephen Marsh-edited Expert Rules, we get this list of level titles, which is only nearly identical. The 3rd-level title, Swordsman, becomes Swordmaster, probably for the same reason the 9th-level title, Lord, gains the parenthetical option of Lady. All later editions of D&D (1983, 1991, 1994) use these same level titles.

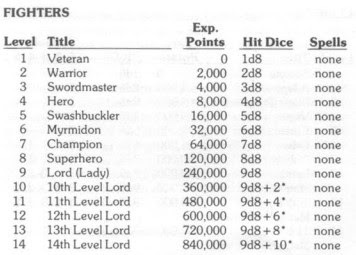

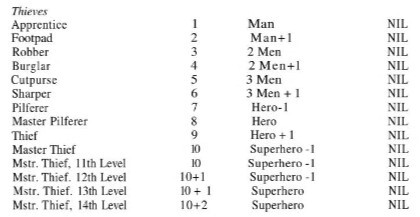

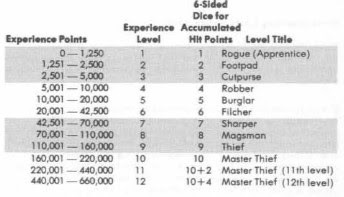

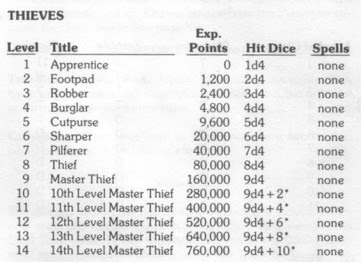

Thieves first appear in Supplement I to OD&D (1975) and use the following level titles:

In the AD&D Players Handbook, we get a slightly different list for thieves. Most of the titles are the same, but the levels they're associated with are swapped. We also get a couple of new titles, like Filcher at 6th level and Magsman at 8th level, because Gygax loved obscure and archaic words.

In the AD&D Players Handbook, we get a slightly different list for thieves. Most of the titles are the same, but the levels they're associated with are swapped. We also get a couple of new titles, like Filcher at 6th level and Magsman at 8th level, because Gygax loved obscure and archaic words.

The D&D Expert Set much more closely follows the Supplement I level titles than does AD&D, replacing only Master Pilferer at 8th level with Thief instead (and lowering the level at which Master Thief becomes available).

The D&D Expert Set much more closely follows the Supplement I level titles than does AD&D, replacing only Master Pilferer at 8th level with Thief instead (and lowering the level at which Master Thief becomes available).

Of the two character classes examined today, it's the thief that shows the most changes in its level titles between their first appearance in Greyhawk and later versions, though, even there, the changes are small. Meanwhile, the fighter changes barely at all. The same cannot be said of clerics and magic-users, as we'll see in the next post in this series.

Madison Bound

So, who's going to be attending Gamehole Con 11 this year? After much hemming and hawing, I finally went ahead and committed to going this October 17–20 in Madison, Wisconsin. As I've mentioned before, I had a great time at GHC the couple of times I was there before, so I'm looking forward to returning once again. I'm also looking forward to seeing friends from all over once again. For me, that's the real joy of conventions: having the chance to chat, hang out, and roll some dice in the flesh rather than just virtually, as I do too often these days.

So, who's going to be attending Gamehole Con 11 this year? After much hemming and hawing, I finally went ahead and committed to going this October 17–20 in Madison, Wisconsin. As I've mentioned before, I had a great time at GHC the couple of times I was there before, so I'm looking forward to returning once again. I'm also looking forward to seeing friends from all over once again. For me, that's the real joy of conventions: having the chance to chat, hang out, and roll some dice in the flesh rather than just virtually, as I do too often these days.With that in mind: who else will be attending? I'd love to have the chance to meet up with some of you and maybe even play something. I've been contemplating using the con as an opportunity to publicly playtest the latest draft of Secrets of sha-Arthan anyway, so it might be even more fun to do it with regular readers and patrons. If you'll be there and would like to get together, drop a note in the comments below and we can begin to planning it now.

August 13, 2024

Retrospective: Temple of Apshai

When I was in the seventh grade, a new kid joined my class and he soon became my best friend. He was also an early adopter of personal computers, owning a TRS-80. I didn't own a computer of any kind – and wouldn't until the early '90s – so I spent a lot of time over his house. admiring this wonder of the dawning Information Age. We played a lot of games on that "Trash-80," most of them not very good or memorable. However, a handful do stick out in my mind as being both, chief among them being Temple of Apshai.

When I was in the seventh grade, a new kid joined my class and he soon became my best friend. He was also an early adopter of personal computers, owning a TRS-80. I didn't own a computer of any kind – and wouldn't until the early '90s – so I spent a lot of time over his house. admiring this wonder of the dawning Information Age. We played a lot of games on that "Trash-80," most of them not very good or memorable. However, a handful do stick out in my mind as being both, chief among them being Temple of Apshai.

Temple of Apshai is one of the earliest computer dungeoncrawlers, not to mention one of the first have graphics, albeit very primitive graphics. For many computer aficionados at the time, I suspect that was one of the biggest draws about the game. For me, though, the mere existence of a computer RPG at all was more than enough to attract my attention. That I'd also seen advertisements for Temple of Apshai in the pages of Dragon probably played a role, too. In those days, I was easily captivated by ads and those Dragon magazine ads, showing an adventurer fighting some antmen, intrigued me.

Temple of Apshai was developed and published by Epyx, the company that also produced Crush, Crumble & Chomp (another game I'd first seen advertised in Dragon). Its earliest version appeared in 1979 and, from what I understand, came on a cassette type, a format that prevented player progress from being saved. My friend and I were playing on a later version that included 5¼-inch floppy disks, thank goodness. Temple of Apshai was already difficult enough as it is. I can't imagine trying to play it without the ability to save.

Temple of Apshai was developed and published by Epyx, the company that also produced Crush, Crumble & Chomp (another game I'd first seen advertised in Dragon). Its earliest version appeared in 1979 and, from what I understand, came on a cassette type, a format that prevented player progress from being saved. My friend and I were playing on a later version that included 5¼-inch floppy disks, thank goodness. Temple of Apshai was already difficult enough as it is. I can't imagine trying to play it without the ability to save.The game's premise is simple: enter and explore the ruined Temple of Apshai, the insect god, in the hopes of finding treasure and magic items. The instruction manual does provide some cursory background information about the founding of the temple and its relationship to the Temple of Geb, the god of earth. But the play of the game doesn't really make use of, let alone depend upon, this information, which is mostly about exploring – and surviving – a four-level dungeon consisting of more than 200 rooms and inhabited by two dozen different types of monsters, most of which are (appropriately) giant insects, along with a handful of slimes and undead.

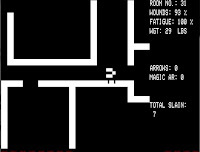

As I said above, the game's graphics were quite primitive, not much better than Atari's Adventure, which appeared only a little later. Even so, I was quite impressed with being able to see the layout of the dungeon rooms and corridors, in contrast to games like Zork, which relied entirely on text to present their in-game environments. The limitations of technology at the time being what they were, your character and the dangers he faces appear as simple pixelated shapes rather than as something genuinely representational. Later versions of the game improved upon this, but that occurred long after my friend and I played the game.

As I said above, the game's graphics were quite primitive, not much better than Atari's Adventure, which appeared only a little later. Even so, I was quite impressed with being able to see the layout of the dungeon rooms and corridors, in contrast to games like Zork, which relied entirely on text to present their in-game environments. The limitations of technology at the time being what they were, your character and the dangers he faces appear as simple pixelated shapes rather than as something genuinely representational. Later versions of the game improved upon this, but that occurred long after my friend and I played the game.Like all early computer games, Temple of Apshai clearly shows inspiration from Dungeons & Dragons, but it has a number of features that remind me a bit of RuneQuest . A character had six ability scores – Strength, Constitution, Dexterity, Intelligence, Intuition, and Ego – whose scores ranged from 3 to 18, just as in D&D. However, unlike D&D, there are no character classes. All characters are effectively fighters, since, aside from magic items, no magic powers or spells exist in the game. Further, combat and other actions can fatigue a character, who must rest in order to regain his energy. Armor lessens damage suffered, while shields make a character harder to hit. None of this is remarkable to old RPG hands, but, for a computer game of this, it's pretty sophisticated stuff.

Because of its graphical limitations, Temple of Apshai could not visually distinguish the contents of one room from another. Instead, each room, trap, and treasure have an entry in the game's instruction manual to which the player must refer in order to get a more detailed description of what his character is presumably encountering. For example, the first room of the dungeon is described as follows:

The smooth stonework of the passageway floor shows that advanced methods were used in its creation. A skeleton sprawls on the floor just inside the door, a bony hand still clutching a rusty dagger, outstretched toward the door to safety. A faint roaring sound can be heard from the far end of the passage.

This is very much like a "real" dungeon, which is to say, one a referee might create beforehand, with keyed room descriptions to which he'd refer in play. I don't think I appreciated this at the time, but, in retrospect, I find it fascinating. I recall reading somewhere that Temple of Apshai's designer, Jon Freeman, was inspired to create the game after he'd spent several years trying to find ways to use computers to aid referees in running D&D campaigns. If true, it's yet another reminder of just how important and influential Dungeons & Dragons has been on the growth and development of computer games and, by extension, computer technology itself.

Like so many early computer RPGs, I don't think I could play Temple of Apshai today. That's no knock against the game itself or its deserved place of honor in the history of computer games. Rather, it's because you can't go home again, however much you might want to do so. What enthralled and amazed my friend and I in 1982 is not something that would do so today – but it was an amazing game in its day and I'm glad to have had the chance to play it.

August 12, 2024

The Articles of Dragon: "Cantrips: Minor Magics for Would-Be Wizards"

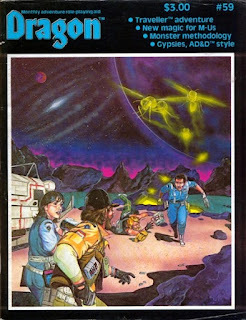

You would think I'd remember issue #59 of Dragon (March 1982) for its 20+ pages of science fiction content, but, at the time I first read it, I was much more interested in Gary Gygax's latest "From the Sorceror's Scroll" column. Entitled "Cantrips: Minor Magics for Would-Be Wizards," this column is what first introduced 0-level spells into Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. Gygax offers these up as the first preview of the AD&D "expansion volume" he was working on at the time and that he hoped would be released "next year" (i.e. 1983). He explains that this volume "will be for both players and DMs, with several new character classes, new weapons, scores of new spells, new magic items, etc."

You would think I'd remember issue #59 of Dragon (March 1982) for its 20+ pages of science fiction content, but, at the time I first read it, I was much more interested in Gary Gygax's latest "From the Sorceror's Scroll" column. Entitled "Cantrips: Minor Magics for Would-Be Wizards," this column is what first introduced 0-level spells into Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. Gygax offers these up as the first preview of the AD&D "expansion volume" he was working on at the time and that he hoped would be released "next year" (i.e. 1983). He explains that this volume "will be for both players and DMs, with several new character classes, new weapons, scores of new spells, new magic items, etc." Needless to say, this was irresistible to my youthful, Gygax-loving, TSR fanboy self. I'd been playing AD&D – or, at least, using AD&D books to play a game we called "AD&D" – since sometime in 1980 and had, during that time, had dutifully acquired all its available volumes. The prospect of a new volume and one penned by Gygax himself filled us with excitement. That he was now sharing monthly glimpses into what this volume might contain in the pages of Dragon more or less assure that I'd be paying careful attention to the magazine from now on.

Of course, this first article in the series of previews didn't really interest me all that much. For whatever reason, my friends and I weren't all that keen on magic-users. It's not that we never played magic-users – well, I didn't, but that's another story – but that our favorite classes tended to be fighters, thieves, and clerics. With one exception, I can't recall a single player character who was a single-classed MU. All of the magic-users amongst our characters were multi-classed elves and even these were pretty uncommon. Consequently, I couldn't get too excited about cantrips, since I knew they wouldn't see much use at our table.

And I was correct in thinking this. Early on, shortly after the article was published, I suggested that we give these new minor spells a whirl to see if they'd actually be useful. As Gygax presents them, a magic-user can memorize four cantrips for every first-level spell he's willing to forgo. At that very favorable exchange rate, a couple of players thought it worth a try, selecting cantrips like exterminate, knot, tangle, and wilt in place of a single detect magic or light. The consensus, as I recall, was that some cantrips had value in certain limited situations, but that, by and large, few magic-users would ever willingly give up a spell slot for them. After that, I don't think we ever thought much about cantrips.

Nevertheless, this remains a memorable and important article for me even now – because it was the first article that suggested to me that the AD&D game's rules might change or evolve in any significant way. You must remember that, by the time I started playing, all three of AD&D's rulebooks had already been released. While both Deities & Demigods and the Fiend Folio came out after my introduction to the hobby, I didn't pay either of them much heed and indeed made comparatively little use of either of them. More to the point, neither one changed much of anything about the AD&D rules, so they could be safely ignored. However, this Gygax column from issue #59 heralded the dawn of a new era, one in which AD&D would, at last, change through the introduction of new character classes, spells, magic items, etc. That was a very big deal to me at the time, hence why I can recall reading this article for the first time, even more than forty years later.

The Book of Apshai

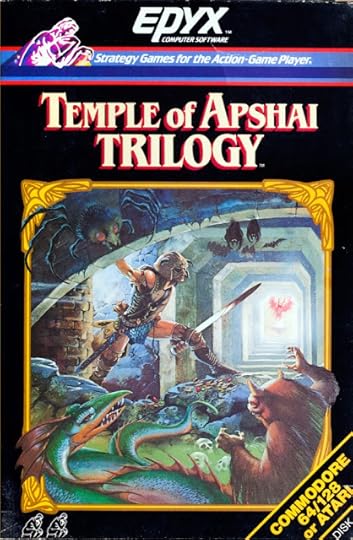

Later this week, I'll be posting a Retrospective on the early dungeoncrawler Temple of Apshai. While doing some research into this important computer game, I was reminded that, in 1985, publisher Epyx released Temple of Apshai Trilogy, which collected all three games in the series and graphically updated them for the newest generation of personal computers. Temple of Apshai Trilogy also included a game manual entitled The Book of Apshai whose interior contained, in addition to instructions on how to install and play the game, some truly amazing art by Mike Mott.

Before getting to the interior art, here's the color cover art of the game box itself, courtesy of Ken Macklin. This image is reproduced, in black and white form, on the cover of The Book of Apshai.

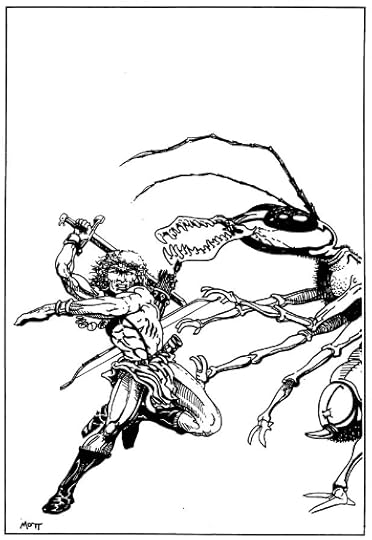

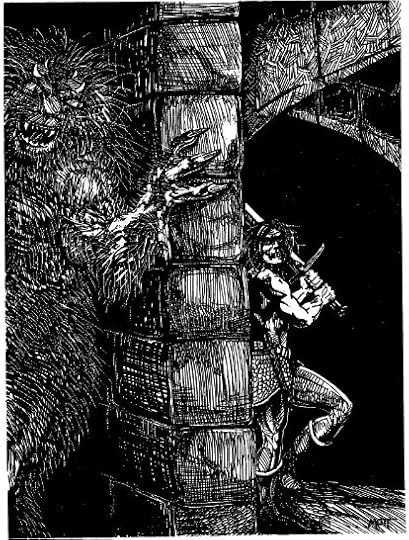

Inside the book, we get to Mike Mott's work, like this piece showing an adventurer facing off against one of the game's iconic Antmen.

Inside the book, we get to Mike Mott's work, like this piece showing an adventurer facing off against one of the game's iconic Antmen.

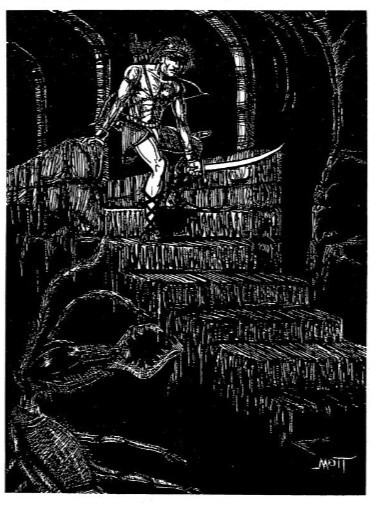

Speaking of Antmen, here's one lurking in the dark near a set of stairs the same adventurer is now descending.

Speaking of Antmen, here's one lurking in the dark near a set of stairs the same adventurer is now descending.

The adventurer appears yet again, this time waiting around a stone pillar, sword drawn, as some vicious monster prepares to attack.

The adventurer appears yet again, this time waiting around a stone pillar, sword drawn, as some vicious monster prepares to attack.

As in Dungeons & Dragons, torches are very important in Temple of Apshai.

As in Dungeons & Dragons, torches are very important in Temple of Apshai.

Here's a nifty little illustration from a section at the end of The Book of Apshai where the concept of roleplaying games is explained to an audience that, even in 1985, might still not understand it. The section is worthy of a post on its own, but I'll leave that for later.

Here's a nifty little illustration from a section at the end of The Book of Apshai where the concept of roleplaying games is explained to an audience that, even in 1985, might still not understand it. The section is worthy of a post on its own, but I'll leave that for later.

I know nothing of Mike Mott, the artist behind these terrific illustrations. Does anyone have any details about him or his career? His artwork is both very good and very evocative, the kind of thing that often appeared in computer game manuals at the time. Just looking at it as I wrote this post was strangely inspiring, which is what good gaming artwork should be.

I know nothing of Mike Mott, the artist behind these terrific illustrations. Does anyone have any details about him or his career? His artwork is both very good and very evocative, the kind of thing that often appeared in computer game manuals at the time. Just looking at it as I wrote this post was strangely inspiring, which is what good gaming artwork should be.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers