James Maliszewski's Blog, page 45

August 27, 2024

Upon the Occasion of the Emperor's Birthday, 2024

Ahead of his 77th birthday in a couple of days, Marc Miller, creator of Traveller, released the following statement through the Citizens of the Imperium mailing list:

Some years ago, fellow game designer Greg Stafford died, and I was impressed that his company announced almost immediately that he had a succession plan in place, and that his legacy and his designs would live on.

His example was an inspiration to me, and I resolved to emulate him. It would be a terrible loss if Traveller were encumbered, or somehow restricted in its outreach to present and future fans.

With that in mind, I have worked to make Traveller an asset to science-fiction role-players... with our user-friendly Fair Use policies, with the Travellers’ Aid Society programs, with the Cepheus editions of Traveller, and with Mongoose as a primary publisher of their edition of Traveller.

Over the past several years, I have turned over more and more responsibilities to Mongoose, and I have collaborated actively with them as they work to realize the Traveller dream. Earlier this year I passed full ownership of Traveller to Mongoose in order to secure its future.

With that in mind, I point out that, following the example of Greg Stafford, I have a succession plan in place: day-to-day decisions about the Traveller game system are already being made by Mongoose Publishing (with my co-operation and approval), and if anything should happen to me, they would carry on with my full knowledge and blessing.

That doesn’t stop me from speaking my mind: expressing opinions about Traveller, writing stories and lore, and even revealing secrets about the universe.

But Traveller is in good hands, now, and far into the far future.

And I thank you for your (continuing) support for Traveller.

Marc

I'd suspected something like this might be in the offing for some time, but this is the first confirmation of it that I've seen – and an official one at that. Since I know there are a lot of Traveller fans who read this blog, I thought they might find this news to be of interest. I may have further thoughts on the matter. If so, I'll save those for a future post.

August 26, 2024

The Articles of Dragon: "It's That Time of Year Again ..."

I'm sure this will come as a great surprise to longtime readers of this blog that, as a young man, I was fairly serious and earnest. Shocking, I know! Of all the things about which I was serious – and there were many – Dungeons & Dragons was near the top of the list. It's no exaggeration to say that, in the first few years after I discovered the game, D&D was an important part not merely of my life but also of my self-conception. I was a D&D player and I was sincerely proud of this fact in a way that I doubt I've ever been since.

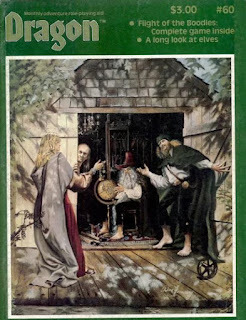

I'm sure this will come as a great surprise to longtime readers of this blog that, as a young man, I was fairly serious and earnest. Shocking, I know! Of all the things about which I was serious – and there were many – Dungeons & Dragons was near the top of the list. It's no exaggeration to say that, in the first few years after I discovered the game, D&D was an important part not merely of my life but also of my self-conception. I was a D&D player and I was sincerely proud of this fact in a way that I doubt I've ever been since.Consequently, when I first came across issue #60 of Dragon (April 1982) and read its contents, I was taken aback. Sure, the article contained a further installment of Roger E. Moore's magisterial demihuman "Point of View" series (focusing on elves this time), along with more cantrips from Gary Gygax and other interesting stuff, but what really caught my eye were a pair of articles that played off longstanding Dragon columns, specifically "Giants in the Earth" and "Dragon's Bestiary." I say "played off," because neither installment in this issue was quite right, as I'll explain.

"Giants in the Earth" was replaced by "Midgets in the Earth" and, rather than presenting D&D stats for characters from classic fantasy and science fiction literature, what we got instead were write-ups for goofy original characters, like the kobold dictator Idi "Little Daddy" Snitmin, Morc the Orc, and master halfling thief Eubeen Hadd. Written by Roger E. Moore and accompanied by artwork that looks like it could have been drawn by Jim Holloway, "Midgets in the Earth" was clearly intended as nothing more than silly fun in honor of April Fool's Day. Please bear in mind that I read this article long before I'd come across the regular April Fool's issues of Polyhedron, so the concept was still somewhat new to me at the time.

The issue's "Dragon's Bestiary" was in a similar vein. Instead of the usual assortment of dangerous and unusual new monsters for use with D&D, we were given entries inspired by various pop culture "monsters," like Donald Duck or Marvin the Martian or the Bad News Bugbears. Like "Midgets in the Earth," these were clearly intended to be silly, but I found them irritating – all the more so because they were written by designers like Tom Moldvay and David Cook, who could have been writing really useful stuff. Why were they wasting effort on such nonsense, I thought? I'd much rather have had more serious content that I could drop into my ongoing AD&D campaign.

The issue's "Dragon's Bestiary" was in a similar vein. Instead of the usual assortment of dangerous and unusual new monsters for use with D&D, we were given entries inspired by various pop culture "monsters," like Donald Duck or Marvin the Martian or the Bad News Bugbears. Like "Midgets in the Earth," these were clearly intended to be silly, but I found them irritating – all the more so because they were written by designers like Tom Moldvay and David Cook, who could have been writing really useful stuff. Why were they wasting effort on such nonsense, I thought? I'd much rather have had more serious content that I could drop into my ongoing AD&D campaign.

Yeah, I was a little tightly wound in those days. Go figure! In time, I came to be a bit more accepting of such silliness, but it took some time – and more April Fool's issues of Dragon to do it. I never fully embraced it, but I did become less uptight about it and the way I enjoyed my hobby. Or at least that's what I keep telling myself ...

Yeah, I was a little tightly wound in those days. Go figure! In time, I came to be a bit more accepting of such silliness, but it took some time – and more April Fool's issues of Dragon to do it. I never fully embraced it, but I did become less uptight about it and the way I enjoyed my hobby. Or at least that's what I keep telling myself ...

August 25, 2024

REVIEW: Knave (Second Edition)

By the mid-1990s, I'd had regular access to the Internet for a number of years and it was great. Forums and websites dedicated to RPGs of every kind were available at the click of a mouse button, offering all manner of interesting and useful content. While most of this content was dedicated to existing roleplaying games, some of it offered up new roleplaying games – the original creations of enthusiastic designers who recognized that they could use the Internet to get their own games to a vastly larger audience than would have ever been possible in the pre-digital age.

While Marcus Rowland's scientific romance RPG, Forgotten Futures is, for me, one of the best examples of these 1990s Internet-distributed games, I think it's fair to say that Steffan O'Sullivan's FUDGE is the most well-known and influential. I first became aware of FUDGE through a dear friend of mine, who felt that its loose, freeform mechanics provided would-be game designers the tools they needed to achieve their goals. At the time, he and I were hoping to put together our own science fiction RPG and so we took a lot of interest in FUDGE, whose "legal notice" was an early example of an open gaming license of the sort that would later propel the d20 System to prominence.

I found myself thinking about FUDGE recently as I read through the second edition of Ben Milton's Knave. Billed as "an exploration-driven fantasy RPG and worldbuilding toolkit, inspired by the best elements of the Old-School D&D movement.," Knave seemed, to my aged eyes, to have a lot in common with FUDGE. Whether one views that comparison as a good thing or a bad thing will, I think, determine your opinion of Knave. Before delving more deeply into this, though, I should explain that, prior to reading this new edition of the game, I wasn't all that familiar with Knave. Aside from Mörk Borg and Electric Bastionland, my knowledge of "ultra-light" RPGs was fairly limited and that no doubt colors what I have to say in this review.

The second edition of Knave is an 80-page digest-sized hardcover book available in both standard and premium formats, the main difference between the two (aside from price) being the cover design. Speaking of presentation, I should note that all of the book's artwork comes courtesy of Peter Mullen, whose artwork is well known (and loved) in the old school community. Their presence is quite welcome, since Knave's layout is otherwise simple and unpretentious, which, while a boon to clarity, tends toward the monotonous, especially in the many sections devoted to random tables. The book also includes a couple of two-page maps by Kyle Latino, which don't connect directly to anything in the text, so they serve more or less as artwork, too.

As a set of rules, Knave is short and quite simple – so short that summaries of nearly everything needed to play fit on the four "pages" inside the front and back covers. I've seen plenty of other RPGs attempt to do this, but Knave is the first I can recall that succeeds. Indeed, I'm pretty sure it'd be possible to run the game using just these four pages and nothing else. That's no small feat, though, as I've already stated, it's only possible because the rules are short and simple. Most actions in Knave – called checks – are handled by a d20 roll modified by a character's appropriate ability score and any relevant modifiers and then compared against a target number (usually 16). Understand this basic mechanic and you understand Knave, with nearly everything else being an embellishment.

In his designer's commentary at the back of the book, Milton explains that he created Knave as "a hack of Basic D&D that [he] created for an after-school gaming club for 5th graders" and his "goal was to streamline and rationalize the rules so that players could learn the rules and create characters in just a few minutes and jump right into playing." Consequently, Knave's rules, while similar to those of D&D, differ from them in a number of respects. For example, there are still the usual six ability score, but they range in score 0–10 rather than 3–18. Further, the use of some of the abilities differs from their usual D&D association, such as Wisdom being used to modify ranged attacks and Constitution playing a role in encumbrance.

Combined with the lack of character classes, Knave thus occupies an odd middle ground for longtime D&D players between the familiar and the unfamiliar. Fortunately, the rules are so uncomplicated that I don't imagine any of the game's deviations from "standard" old school conventions should prove an impediment to a veteran's ability to pick them up. Meanwhile, a complete neophyte, who knows little or nothing about D&D, would probably find them fairly intuitive, which seems to have been the goal. In the aforementioned designer's commentary – one of my favorite sections of the book – Milton regularly uses words like "straightforward," "quick," and "easy" to explain the thought process behind Knave's rules.

This philosophy suffuses the game, where everything associated with dungeon delving and wilderness travel – the core activities of old school Dungeons & Dragons – is pared down to quick, reasonably easy to use and understand procedures, with lots of room for individual expansion and experimentation. Combat, for instance, includes the possibility of initiating "maneuvers," like disarming or stunning, that is self-admittedly inspired by the "mighty deeds of arms" from Dungeon Crawl Classics, but without the same mechanical complexity. Magic, whether in the form of spells or relics, is similarly open-ended, with plenty of scope for creativity in their execution. This approach holds for most of the activities associated with classic play, like leveling up, encounters, and even equipment.

This open-ended toolkit approach might be off-putting to some, especially those looking for a more "full bodied" fantasy roleplaying game – but that's not what Knave is or was intended to be. Certainly, you could play Knave "straight" and have a satisfying experience with it. However, it's pretty clear from the way the game is written and presented that Milton expects that the rules of Knave will mutate and change with regular play, as each group adds to and subtracts from what he has put on offer in the rulebook. "Altering rules and writing your own is a time-honored part of the hobby," as he explains in Knave's introduction.

An important key to understanding Knave, I think, is that, in addition to its simple, concise mechanics, the rulebook also contains numerous random tables throughout its pages, all of them with 100 results. These tables cover careers to wizard names to disasters and more. Like everything else in Knave, they're laconic and intended to serve as jumping off points for one's imagination rather than the final word. More than that, they're clearly intended to be used in play, when the player or referee needs to come up something quickly. As a big fan of random tables and the effect they can have on play, I applaud the inclusion of these tables, as I know firsthand just how useful they can be.

In the end, Knave is a pleasant surprise. Reading it made me think more seriously about the relationship between the complexities of rules and play, as well as my own preferences with regard to each of them. While I'm not completely sold on some of Knave's mechanical deviations from classic play, like the lack of classes, I nevertheless appreciate the way Milton's own choices made me ponder what I like and why, which I think will strengthen my own design work in the future. I also appreciate that, while Knave made think about such matters, its primary purpose is not philosophy but rather presenting "a framework that makes playing old-school RPGs straightforward, intuitive, easy to prep, and easy to run" – a laudable goal at which I believe it succeeded.

August 22, 2024

Lament for a Lost Age

One of my most popular posts is "The Ages of D&D," which I wrote more than fifteen(!) years ago, on January 11, 2009. In it, I attempted to sort the history of Dungeons & Dragons into a series of "ages" – Golden, Silver, Bronze, etc. I was still fairly new to the blogging game when I wrote that post and, while I largely stand behind its conclusions, I now concede that I relied more on hazy memories and intuitions than on anything approaching "research." Perhaps one day I'll offer a more considered discussion of the Ages of D&D, complete with evidence to support my assertions, but, for the purposes of the present post, I'm going to go with the categories and timeframes I established back in 2009.In the original post, I assert that the Golden Age of D&D lasted almost a decade, from 1974 until 1983. In retrospect, I'm not entirely sure why I chose 1983 as the end point of the Golden Age. My guess is that it I saw the arrival of Dragonlance in 1984 as marking a definitive break with the way the game had previously been marketed and played. Even so, if you read my original post, you'll see that I allow for the possibility that the Golden Age actually ended somewhere 1979 and 1981, with either the completion of AD&D or the publication of Moldvay's Basic Set being important milestones, albeit for different reasons. Even then, I think I recognized that the game had already changed by the time I first encountered it in late 1979 and indeed that I might never have encountered it at all had it not been for those changes.

One of my most popular posts is "The Ages of D&D," which I wrote more than fifteen(!) years ago, on January 11, 2009. In it, I attempted to sort the history of Dungeons & Dragons into a series of "ages" – Golden, Silver, Bronze, etc. I was still fairly new to the blogging game when I wrote that post and, while I largely stand behind its conclusions, I now concede that I relied more on hazy memories and intuitions than on anything approaching "research." Perhaps one day I'll offer a more considered discussion of the Ages of D&D, complete with evidence to support my assertions, but, for the purposes of the present post, I'm going to go with the categories and timeframes I established back in 2009.In the original post, I assert that the Golden Age of D&D lasted almost a decade, from 1974 until 1983. In retrospect, I'm not entirely sure why I chose 1983 as the end point of the Golden Age. My guess is that it I saw the arrival of Dragonlance in 1984 as marking a definitive break with the way the game had previously been marketed and played. Even so, if you read my original post, you'll see that I allow for the possibility that the Golden Age actually ended somewhere 1979 and 1981, with either the completion of AD&D or the publication of Moldvay's Basic Set being important milestones, albeit for different reasons. Even then, I think I recognized that the game had already changed by the time I first encountered it in late 1979 and indeed that I might never have encountered it at all had it not been for those changes.

I've previously discussed the foundational role played by David C. Sutherland III in giving birth to the esthetics of Dungeons & Dragons. Sutherland's grounded, vaguely historical illustrations were, for several years, the face of D&D. During the three-year period between 1975 and 1978, Sutherland and Dave Trampier were together responsible for nearly all the art that appeared in TSR products, not just Dungeons & Dragons but other games, too, like

Gamma World

and Boot Hill. Not bad for a couple of "talented amateurs." is it?

I've previously discussed the foundational role played by David C. Sutherland III in giving birth to the esthetics of Dungeons & Dragons. Sutherland's grounded, vaguely historical illustrations were, for several years, the face of D&D. During the three-year period between 1975 and 1978, Sutherland and Dave Trampier were together responsible for nearly all the art that appeared in TSR products, not just Dungeons & Dragons but other games, too, like

Gamma World

and Boot Hill. Not bad for a couple of "talented amateurs." is it?By now, you can probably guess where I'm going with this: the end of the Golden Age is marked by a shift in the game's esthetics away from the extraordinary ordinary artwork of Sutherland and Trampier and toward something else – just what is a different question. Nevertheless, consider that, in 1979, TSR began to expand its stable of artists, hiring Erol Otus (whose TSR artwork debuted in later printings of the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide) and David "Diesel" LaForce (ditto). The next year, in 1980, TSR added Jeff Dee, Jim Roslof, and Bill Willingham as well. The cumulative effect of their artistic talents is unmistakable.

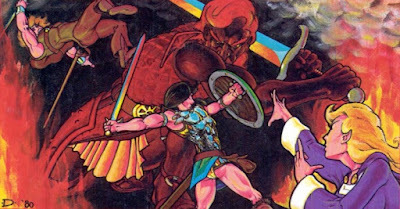

The change in the look of Dungeons & Dragons products in the aftermath of hiring these five artists cannot be denied. Pick up almost any D&D book or module published between 1979 and 1981 and compare it to its predecessors. Earlier products have a stiff, staid, "serious" look to them that, to my eyes at least, shows some continuity with the look and feel of the historical wargames out of which the hobby grew. By contrast, the D&D books and modules from the '79 to '81 period are bright, bold, and dynamic. They are clearly the work of different artists with very different esthetic sensibilities.

The change in the look of Dungeons & Dragons products in the aftermath of hiring these five artists cannot be denied. Pick up almost any D&D book or module published between 1979 and 1981 and compare it to its predecessors. Earlier products have a stiff, staid, "serious" look to them that, to my eyes at least, shows some continuity with the look and feel of the historical wargames out of which the hobby grew. By contrast, the D&D books and modules from the '79 to '81 period are bright, bold, and dynamic. They are clearly the work of different artists with very different esthetic sensibilities.These sensibilities ranged from the comic book inflected art of Dee and Willingham to the more restrained heroic action of Roslof and the underground comix stylings of Otus. Whether this shift was "better" or "worse" than what preceded it is immaterial. What matters is that it happened and it denotes the beginning of a new phase in the history of Dungeons & Dragons – the mass marketing of the game to an audience beyond college age and older wargamers whose points of reference were the pulp fantasy authors and stories that I've attempted to draw attention to over the years.

I entered the hobby right smack in the middle of this period of D&D history. After my initial exposure to Dungeons & Dragons through the Holmes Basic Set and

In Search of the Unknown

, many of my earliest memories of the game are filtered through the artwork of Dee, Otus, Willingham, and the other newcomers to TSR. While only a few of my Top 10 Illustrations of the Golden Age – bear in mind I wrote those posts before I started to re-evaluate my thoughts on the matter – are the work of these artists, that does nothing to diminish the impact they had not just on me but on D&D's presentation to the wider world. For a large cohort of new players, the 1979–1980 hires defined Dungeons & Dragons in much the same way that Sutherland and Trampier did before them.

I entered the hobby right smack in the middle of this period of D&D history. After my initial exposure to Dungeons & Dragons through the Holmes Basic Set and

In Search of the Unknown

, many of my earliest memories of the game are filtered through the artwork of Dee, Otus, Willingham, and the other newcomers to TSR. While only a few of my Top 10 Illustrations of the Golden Age – bear in mind I wrote those posts before I started to re-evaluate my thoughts on the matter – are the work of these artists, that does nothing to diminish the impact they had not just on me but on D&D's presentation to the wider world. For a large cohort of new players, the 1979–1980 hires defined Dungeons & Dragons in much the same way that Sutherland and Trampier did before them.But, like all such periods of roiling creativity, it did not last long. By 1982, many of these artists no longer worked at TSR and those that remained, like LaForce, shifted over to cartography, doing illustrations only sporadically. New artists, like Larry Elmore and Jeff Easley, appeared on the scene around the same time, lending their considerable talents to depicting the fantastic realism of the dawning Silver Age. Lots of readers slightly younger than me no doubt have similar feelings of affection toward this next group of artists, as they should, but, for me, many of my fondest memories of Dungeons & Dragons will be forever intertwined with that first "new" generation of artists whose arrival on the scene coincided with my own.

Interviews

An early hallmark of this blog were the interviews I did with many of the writers and artists of the early days of the hobby. In the years since I returned to Grognardia, I've done comparatively fewer interviews. That's something I'd like to try to change in the coming months.

Are there any people you'd especially like to see interviewed? When I'm at Gamehole Con this year, my hope is that I'll be able to secure a few interviews with notable guests and attendees for the blog. Beyond those, who else would you be interested in?

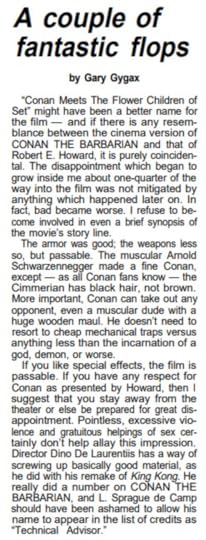

Conan Meets the Flower Children of Set

Long ago, I discussed my own thoughts about the 1982 Conan the Barbarian movie. In issue #63 of Dragon (July 1982), Gary Gygax offers his own.

August 21, 2024

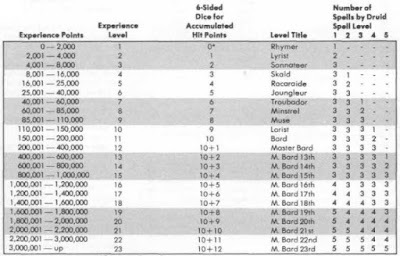

Level Titles: Druids, Rangers, and Bards

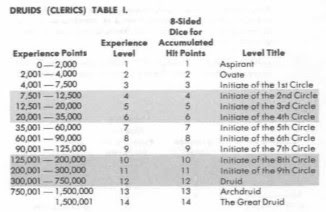

The druid class first appeared in Supplement III to OD&D, Eldritch Wizardry (1976). Though the supplement gives Gary Gygax and Brian Blume the byline, the class was actually the creation of Dennis Sustare, who's credited with a special thanks (and dubbed "The Great Druid"). Here's the original list of druid level titles:

The level titles of the druid found in the AD&D Players Handbook (1978) is nearly identical, except that Gygax has inserted a new title, "ovate," between "aspirant" and "initiate of the 1st circle." Its inclusion is interesting, because of its connection to British neo-druidism, where "ovate" is a type of prophet or seer. I suppose it's a good thing that the term and its connections are sufficiently obscure or else critics of the game might have had more "support" for their bad arguments against it.

The level titles of the druid found in the AD&D Players Handbook (1978) is nearly identical, except that Gygax has inserted a new title, "ovate," between "aspirant" and "initiate of the 1st circle." Its inclusion is interesting, because of its connection to British neo-druidism, where "ovate" is a type of prophet or seer. I suppose it's a good thing that the term and its connections are sufficiently obscure or else critics of the game might have had more "support" for their bad arguments against it.

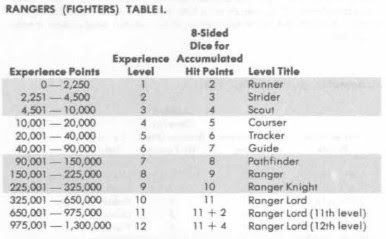

The ranger class originates in volume 1, number 2 of The Strategic Review (Spring 1975) in an article written by Joe Fischer. Presented as a sub-class of fighting men akin to the paladin (which appeared in the Greyhawk supplement earlier the same year), this OD&D version of the ranger has the following level titles:

The ranger reappears in the AD&D Players Handbook. Its level titles are almost identical to those from The Strategic Review. However, a few of the titles have been transferred to different levels and the original 9th-level title (ranger-knight) has been pushed back to level 10, in order to make room for the title of "ranger."

The ranger reappears in the AD&D Players Handbook. Its level titles are almost identical to those from The Strategic Review. However, a few of the titles have been transferred to different levels and the original 9th-level title (ranger-knight) has been pushed back to level 10, in order to make room for the title of "ranger."

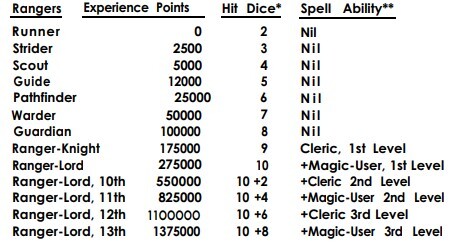

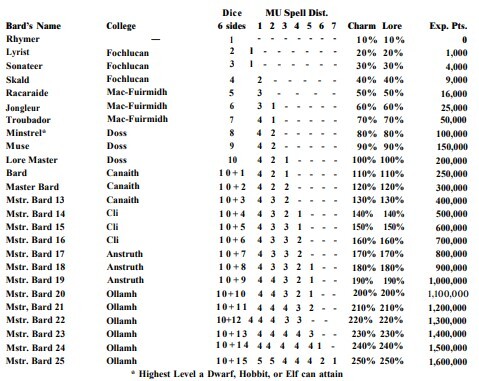

Like the ranger, the bard class first appeared in the pages of The Strategic Review, specifically volume 2, issue 1 (February 1976). Written by Doug Schwegman, the article presents bards as jacks-of-all-trades based on ideas drawn from the Celtic bard, the Nordic skald, and the southern European minstrel. As originally presented, the bard has the following level titles:

Like the ranger, the bard class first appeared in the pages of The Strategic Review, specifically volume 2, issue 1 (February 1976). Written by Doug Schwegman, the article presents bards as jacks-of-all-trades based on ideas drawn from the Celtic bard, the Nordic skald, and the southern European minstrel. As originally presented, the bard has the following level titles:

The level titles of the AD&D version of the bard differ from the OD&D version in only one small way. The OD&D title of "lore master" is changed – bizarrely, in my opinion – to "lorist," a coinage for which I can find very little evidence in any of the dictionaries to which I have access. Regardless, I find it notable that Gary Gygax, in translating Schwegman's bard to AD&D, retained nearly all the level titles while changing the overall nature of it.

The level titles of the AD&D version of the bard differ from the OD&D version in only one small way. The OD&D title of "lore master" is changed – bizarrely, in my opinion – to "lorist," a coinage for which I can find very little evidence in any of the dictionaries to which I have access. Regardless, I find it notable that Gary Gygax, in translating Schwegman's bard to AD&D, retained nearly all the level titles while changing the overall nature of it.

Druids explicitly and bards implicitly all belong to an organization that governs their advancement. In the case of druids, this advancement is similar to that of monks in being adjudicated through a trial by combat. I find details of this very fascinating for what they suggest about the "world" of Dungeons & Dragons and how the various character classes fit into it. Perhaps this is a topic worthy of a later post or two.

Druids explicitly and bards implicitly all belong to an organization that governs their advancement. In the case of druids, this advancement is similar to that of monks in being adjudicated through a trial by combat. I find details of this very fascinating for what they suggest about the "world" of Dungeons & Dragons and how the various character classes fit into it. Perhaps this is a topic worthy of a later post or two.

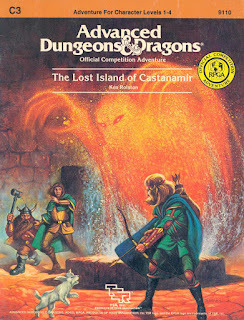

Retrospective: The Lost Island of Castanamir

I'm a fan of the first two entries in the C-series of AD&D modules, The Hidden Shrine of Tamoachan and The Ghost Tower of Inverness, but a guarded one. That's because these modules, filled as they are with tricks, traps, and puzzles designed to challenge the wits – and patience – of the players, are hard to run properly and, in my youth, I was not always up to the task. I don't mean that as a knock against either module, which I do like, but I do recall that they were frustrating for both me and my players, albeit for different reasons.

I'm a fan of the first two entries in the C-series of AD&D modules, The Hidden Shrine of Tamoachan and The Ghost Tower of Inverness, but a guarded one. That's because these modules, filled as they are with tricks, traps, and puzzles designed to challenge the wits – and patience – of the players, are hard to run properly and, in my youth, I was not always up to the task. I don't mean that as a knock against either module, which I do like, but I do recall that they were frustrating for both me and my players, albeit for different reasons. To some extent, my experiences were probably due to my ignorance of the very idea of tournament modules. I remember being somewhat confused by the scoring guidelines and sheets included with many of TSR's AD&D modules from the early '80s, since I'd never attended a convention, let alone participated in a tournament. Moreover, our preferred style of play was very loose and rambling and most tournament modules included very contrived framing devices that were hard to fit into that style.

By the time the third module in the C-series, The Lost Island of Castanamir, was published in 1984, our style of play had evolved further, this time in the direction of epic fantasy under the influence of Dragonlance. Consequently, tournament modules fit even less into our campaigns than they had before. Skeptical as I was, I remained a TSR fanboy, which meant I often snapped up anything new the company might publish, including this module. Besides, it had a colorfully eye-catching cover, courtesy of Jeff Easley, whose art I'd come to like a great deal – though I did wonder about why it looked like the elf was preparing to shoot his bow at the little yappy white dog in front of him.

Written by Ken Rolston, who'd later go on to bigger and better things both within the tabletop RPG and video game worlds, The Lost Island of Castanamir is, alas, not a very good adventure. Or at least, as presented, it's not very good.

Its premise is that the player characters are hired by a magician to investigate a mysterious island that, until recently, had disappeared entirely. This island had once been the abode of a powerful magic-user named Castanamir the Mad. Castanamir was eccentric and paranoid, believing that his rivals sought to steal his wealth. Therefore, he protected his island home with all manner of spells to ward off would-be thieves. One of those spells caused the island to vanish without a trace. Its sudden return has aroused the suspicion – and greed – of the magician who hires the PCs to see why the island has returned and what, if anything, remains of Castanamir and his treasures.

As backgrounds to fantasy adventures go, this isn't a bad one. You've got a forbidding locale, a mystery, danger, and, of course, the promise of treasure. That this is an adventure designed for 1st–3rd level characters is also quite appealing, since many low-level modules are much blander and limited in scope. Despite this, the final product is less than it could have been, which is a shame, as there are some genuinely interesting ideas in it.

For example, the characters soon discover that Castanamir was a master of planar sorcery and his abode isn't laid out according to a straightforward plan. Instead, doors act as magical portals that connect to one another in unexpected ways. The module's maps include codes to indicate how the various doors connect to one another. Initially, this cartographic idiosyncrasy will foil with efforts by the characters to map the place, disorienting them. In time, they'll likely figure out how the various doors and rooms related to one another. It's a fairly simply trick but an effective one. I've used similar tricks in my own adventure locales over the years.

Other tricks and challenges are more whimsical, even silly, to the point that I'm not sure it's fair to call them "challenges" so much as vexations. I've never been a fan of "Mother, may I?" tricks or traps that depend on the players' ability to read the referee's mind or to use out of character knowledge to succeed. I much prefer challenges that are, in the terminology of commentators more pretentious than even I, call "diegetic," which is to say, explicable solely within the context of the game world. This isn't a damning criticism of the module. Indeed, it's very much in keeping with venerable tradition within the hobby, but, at the time I first read this, I had tired of it and, even now, my feelings about it are decidedly negative.

Perhaps The Lost Island of Castanamir plays better than it reads – I wouldn't know, as I never ran it for my friends back in the day – but I doubt it. In charity, I suppose it could be called a "funhouse dungeon" that just didn't click the way that, say, White Plume Mountain did. I can't quite put my finger on the source of my dissatisfaction. Maybe I'd simply lost interest in that kind of dungeon and was looking for something more naturalistic. By this point, I'd been playing Dungeons & Dragons in one form or another for five years more or less non-stop. Perhaps the truth is that I was simply tiring of D&D itself and workmanlike modules of this sort were simply not up to the task of firing my imagination in the way they might have even a year or two earlier.

Regardless, The Lost Island of Castanamir was a something of a letdown for me and, in the years since, I've come to associate it with my waning enthusiasm for D&D in the mid-1980s. That's terribly unfair to the module and Ken Rolston, who, as I said, has produced some truly remarkable stuff, but such is the power of memory, I guess.

August 20, 2024

The War against Lovecraft

I've often joked that nowadays, in critical discussions of the creator of Conan the Cimmerian, it's almost required that he be referred as "that writer who killed himself, Robert E. Howard." It's a joke – but only barely – because you can easily find plenty of examples where the circumstances of Howard's death have become the most important thing about him. I find this frankly bizarre, as if any man can be reduced to a single fact about his life, never mind a man as complex and, let's be honest, troubled as Robert Ervin Howard.

I've often joked that nowadays, in critical discussions of the creator of Conan the Cimmerian, it's almost required that he be referred as "that writer who killed himself, Robert E. Howard." It's a joke – but only barely – because you can easily find plenty of examples where the circumstances of Howard's death have become the most important thing about him. I find this frankly bizarre, as if any man can be reduced to a single fact about his life, never mind a man as complex and, let's be honest, troubled as Robert Ervin Howard.I was reminded of this recently because I was given a copy of Free League's oversized edition of H.P. Lovecraft's "The Dunwich Horror," illustrated by François Barranger. It's an absolutely gorgeous book that pairs HPL's text with Barranger's moody, evocative artwork. The back of the book includes "A Note about H.P. Lovecraft," which reads:

There has long been an ongoing debate about Lovecraft's world view and prejudices. Lovecraft wrote in a time when racism was widespread and accepted in literature, and it is in this context that his works should be read.

Lovecraft himself expressed a racist world view and often let it shine through in his texts. Lovecraft's novels are outstanding classics, but the racism that now and then appears in certain texts is reprehensible, and something that we in Free League reject and distance ourselves from.

Despite this, we have chosen to print The Dunwich Horror without linguistic intervention. It is one of the greatest classics in horror literature. Lovecraft's stories deserve to be released and find a new readership, but at the same time, the author's racism should be approached critically and rejected.

What's the purpose of this "note?" No doubt I am biased, but I can't recall anything in "The Dunwich Horror" that could be called racist by any reasonable definition. Given that, why alert the reader that Lovecraft himself held odious views about his fellow man? Had the text of "The Dunwich Horror" contained clear and unambiguous evidence of these views, this approach might – might – have made some sense, but it doesn't. Consequently, the boast that "we have chosen to print The Dunwich Horror without linguistic intervention" is an empty one. There's nothing courageous or principled about it. Instead, it comes across as an attempt to look virtuous while doing to Lovecraft what is often done to Howard: reduce him to a single fact about his life – "that racist writer, H.P. Lovecraft."

I don't begrudge anyone his feelings about H.P. Lovecraft and his reprehensible opinions. If someone sincerely believed that even his stories with no explicitly racist content are somehow tainted because of HPL's views, I can find no fault with him. I don't share that belief any more than I share Lovecraft's beliefs about race, but it's not for me to say what is or is not beyond the pale for someone else. We should be free to decide what we like and don't like without censure, especially when it comes to works of art, whose impact is often intensely personal.

That said, I strongly reject the tendency of the last decade or so to try to tarnish Lovecraft's literary fame by pointing out his racism at every turn. To me, it smacks of an invidious effort to diminish the influence he continues to exert on fantasy, science fiction, horror, and the wider popular imagination. When one considers that, at the time of his death in 1937, Lovecraft and his comparatively small corpus of writings were largely unknown, his lasting impact is all the more remarkable. He belongs to a very select group of popular writers, whose ideas have transcended the short span of his life and now belong to the ages. What better way to take Lovecraft down a peg than to point out again and again that he was a virulent racist?

I regularly say that it's easy, from the vantage point of the present, to hurl brickbats at our ancestors for their ignorance, shortsightedness, and other sins. That's especially true of a man like H.P. Lovecraft, who is estimated to have written nearly 90,000 letters to dozens of correspondents during his lifetime. In those letters, of which only about 10% survive, HPL revealed much about himself, his life, and his opinions. We thus have a much better sense of him as a man, both good and bad, than we do about many historical figures, which, of course, makes it all the easier to highlight his flaws, if that's what one wishes to do.

As for myself, I prefer, on the occasion of 134th anniversary of his birth, to unambiguously celebrate H.P. Lovecraft and his works. All of us reading this owe him and his singular imagination a debt of thanks.

August 19, 2024

The Articles of Dragon: "Giants in the Earth"

As I pen more posts for this series, you'll notice that many of its entries are themselves about series of articles from the pages of Dragon. I could offer a lot of explanations for this, but the simplest, I suppose, is that, with series, you know what you're getting. In theory, if you like one entry in the series, you will probably enjoy those that follow. Series provide a foundation on which to build and a format to follow that makes them attractive to both writers and readers – that's the reason this blog has so many series of its own.

Issue #59 (March 1982) introduced me to a new series of Dragon articles. Entitled "Giants in the Earth," this was an irregular feature devoted to presenting famous characters from fantasy (and occasionally science fiction) literature in terms of Dungeons & Dragons game mechanics. This particular issue included write-ups for five different characters – Poul Anderson's Sir Roger de Tourneville (by Roger E. Moore), L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt's Harold Shea (by David Cook), Alexei Panshin's Anthony Villiers (by Andrew Dewar), Clifford Simak's Mark Cornwall and Sniveley (both by Roger E. Moore).

At the time I first saw this article, I think I was only familiar with Sir Roger de Tourneville, having already read The High Crusade. The others were completely unknown to me and, in the case of the Simak characters, I'm embarrassed to admit, still are. Nevertheless, I found the piece fascinating for several reasons. First, almost from the moment I started playing D&D, I began to think about how best to stat up characters from myth, legend, and books. Seeing how "professional" writers did so held my interest. Second, many of the entries – even the science fiction ones! – included suggestions on introducing these characters into an ongoing D&D campaign, an idea I'd never considered before. Finally, the entries served to introduce me to authors and books I might otherwise never have encountered, just as Appendix N and Moldvay's "Inspirational Source Material" section had done.

That last one is of particular importance to me, especially nowadays, as the inspirations for fantasy roleplaying shift away from books of all kinds and more toward movies and video games. With the benefit of hindsight, one of the things that's very obvious is how much more literary fantasy was in my youth. Arguably, that's because, until comparatively recently, fantasy hadn't much penetrated the mainstream and thus there were few other ready sources for the genre. If you were interested in wizards and dragons and magic swords, books were all you had, whereas today we have a greater number of options available to us. Perhaps – and maybe I'm just being an old man again – I detect a difference in kind between the literary fantasies I grew up reading (and that inspired the founders of the hobby) and the pop culture stuff we see today.

The irony of my being introduced to "Giants in the Earth" through this issue is that it's one of the last ones published in Dragon. Though I'd eventually see some of the earlier installments, the vast majority of them were long out of my reach, their having been published long before I started playing RPGs, let alone reading the magazine. Even so, the few that I did read served the useful purpose of broadening my knowledge of fantasy and science fiction, as well as acquainting me with characters and writers who would, in time, become lifelong companions.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers