James Maliszewski's Blog, page 42

September 24, 2024

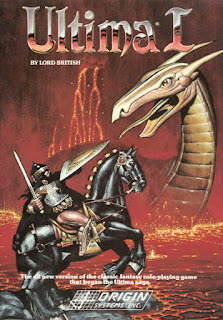

Retrospective: Ultima

Regular readers will recall that, growing up, I did not have a personal computer. That's why I spent so much time at the homes of friends who did. Indeed, it was only because of those friends that I was able to play such foundational computer roleplaying games as Telengard, Wizardry, and

Temple of Apshai

. Even in college, I didn't own a computer, so I continued the practice of using others' computers until the dawn of the 1990s, when I finally entered the modern world and at last got one of my own.

Regular readers will recall that, growing up, I did not have a personal computer. That's why I spent so much time at the homes of friends who did. Indeed, it was only because of those friends that I was able to play such foundational computer roleplaying games as Telengard, Wizardry, and

Temple of Apshai

. Even in college, I didn't own a computer, so I continued the practice of using others' computers until the dawn of the 1990s, when I finally entered the modern world and at last got one of my own. During my college years, there were two CRPGs I remember playing with great enthusiasm: Pool of Radiance and Ultima – or Ultima I as it had been rebranded in 1986. Ultima first came out in 1981, but I don't believe I was aware of it at the time. In any case, I never had the chance to play it until several years later, well after it had spawned a series of sequels. Consequently, everything I'll say in this post pertains to the 1986 version, published by Origin Systems. If there are any significant differences between it and the earlier version(s) of the game, please let me know in the comments.

Like so many early computer games, Ultima had an interesting instruction manual with some impressive artwork. The manual laid out the premise of the game as well as the parameters under which it operates. It does so almost entirely as if it were a document being read by the player's character. Consequently, the information contained within (mostly) lacks any reference to game mechanics or things that the character would not know. Some of it is even written as if an unnamed person is speaking directly to the character, who is addressed as "Noble One" and assumed to be the hero who will save the realm of Sosaria from the depredations of necromancer, Mondain.

Like most computer RPGs, then or now, Ultima owes a lot to Dungeons & Dragons in its overall conception and gameplay. However, unlike, say, Wizardry, it does not include the possibility of controlling an entire party of adventurers, which is something that was added in its sequels. Instead, the player controls a single character, whom he creates before starting his adventure. A character has six attributes that are nearly identical to those in D&D. Likewise, the races available are familiar ones – human, elf, dwarf, and bobbit (halfling). The same is true for the professions, consisting of fighter, cleric, wizard, and thief. In short, it's all pretty standard stuff and nothing that someone who'd been playing pen-and-paper RPGs would have found the slightest bit unusual.

In addition to being a foul necromancer, the aforementioned Mondain is also invulnerable to attack, thanks to his possession of a powerful artifact, the Gem of Immortality. Finding a way to circumvent the effects of the gem is thus the character's main quest throughout Ultima. To succeed in this quest, the character must travel throughout the realm, interact with NPCs, and explore dungeons and other locales. In the process, the character will acquire wealth, better gear, and experience points, allowing him to become more powerful. Again, it's all pretty standard stuff that we've seen many times before.

The "standard" nature of all this was simultaneously an asset and a drawback to Ultima, at least from my perspective at the time. I appreciated that it was pretty easy to pick up and play. Having played D&D for some time beforehand, there was very little in Ultima that surprised me. On the other hand, there weren't really any elements of the game that wowed me. I might have thought differently, if I had encountered it upon its original release in 1981. By the time I discovered it, in 1988, I'd already seen a number of other games that did what it did, often better. For example, Pool of Radiance seemed to me to be a much better implementation of the core concepts of tabletop RPGs in digital form – and it used the official AD&D rules to boot!

Of course, I still played Ultima and enjoyed myself. Even in the midst of my college studies, I still had a lot of spare time to waste on computer games. Consequently, I don't rate Ultima quite as highly as it probably deserves. Certainly, the game went on to become a very successful and influential CRPG series. To this day, I still know lots of people with very fond memories of the game and its sequels. Meanwhile, its spin-off, Ultima Online, released in 1997, was one of the first truly successful massive multiplayer online roleplaying games (or MMORPGs – a term coined by Richard "Lord British" Garriott, the creator of Ultima). For that reason alone, its place in the history of computer RPGs is assured.

September 23, 2024

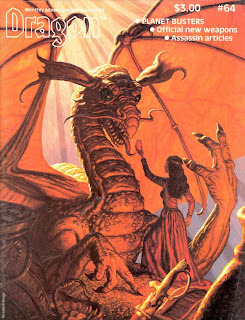

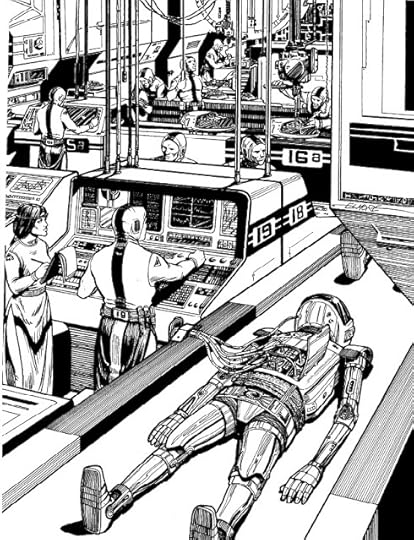

The Articles of Dragon: "Robots – Mechanical Sidekicks for Traveller Players"

Stop me if you've heard this one: Traveller is probably my favorite roleplaying game. Although I've played it far less often than I've played Dungeons & Dragons, GDW's game of science fiction adventure in the far future remains my true love (and I say this even after having taken a stab at having created my own SF RPG).

Stop me if you've heard this one: Traveller is probably my favorite roleplaying game. Although I've played it far less often than I've played Dungeons & Dragons, GDW's game of science fiction adventure in the far future remains my true love (and I say this even after having taken a stab at having created my own SF RPG). There are many reasons why this is the case and I could go on at some length enumerating them. Rather than do that here, I'll simply say that Traveller's main virtue is that, in its classic form, it's a versatile, easy to use set of rules that gives a referee nearly everything he needs to create his own planet-hopping sci-fi setting and keep it going for years. When I called 1982's The Traveller Book "the perfect RPG book" a few years ago, I meant it.

Even so, Traveller's approach to science fiction is quirky at times. There are numerous lacunae in its rules, such as, for example, the lack of laser pistols. While that particular omission never bothered me – I had Star Frontiers for that flavor of sci-fi – there was one area where I did feel as if Traveller had dropped the ball: robots. Until the release of Book 8: Robots in 1986, Traveller had no official rules for robots. Indeed, outside of the warbots employed by the Zhodani, there was scarcely a mention of robots at all within the canon of the game.

I felt the lack of robots in Traveller very keenly. At the time, I felt robots were an important, if not essential, aspect of spacefaring science fiction. Consequently, I was very happy to see Jon Mattson's article in issue #64 of Dragon (August 1982), "Robots – Mechanical Sidekicks for Traveller Players." In just six pages, Mattson provides fairly complete rules for designing and using robots in Traveller. His rules take inspiration from similar design sub-systems in Traveller, such as the starship construction system. This works to their advantage, since players of the game should already be familiar with the general framework on which he's riffing.

Obviously, a six-page set of rules cannot cover every possibility. There are plenty of areas that probably deserve expanded treatment (like the use of robots as player characters) or additional options beyond those Mattson includes. However, that's a minor criticism. The genius of the article is not that it's comprehensive, but that it provides a structure from which a referee could work in his own campaign. Because there was nothing comparable in GDW's materials, this was a godsend, which is why the articles remains a standout for me in this issue of Dragon.

So useful did I find this article that it achieved a status reserved only for a handful of others: I photocopied it and included it in my GM's binder. Like a lot of gamers in those days, I had this large binder in which I kept my notes, hand drawn maps, character sheets, and other papers I felt important enough to carry around with me, like Xeroxed copies of articles from Dragon and other gaming magazines. I regret that I no longer have that binder, if only to see what articles and other bits of ephemera I deemed valuable enough to keep inside it.

Another reason "Robots" looms large in my memory is the full-page artwork that accompanied it – by Larry Elmore, no less! I think the illustration supports my contention that Elmore was better suited to science fiction than to fantasy. (It's also an inadvertently ironic piece in that it depicts large numbers of human workers involved in the manufacturing of robots, which fitting, given Traveller's own occasionally quaint notions of technological development.)

"Orcs, goblins & trolls prefer Grenadier figures ..."

Another memorable Grenadier Models advertisement, this one appearing at the back of issue #64 of Dragon (August 1982).

September 22, 2024

REVIEW: A True Relation of the Great Virginia Disastrum, 1633

A True Revelation of the Great Virginia Disastrum, 1633 (hereafter Disastrum) by Ezra Claverie may well be the definitive product for Lamentations of the Flame Princess. I say "may," because my assessment depends heavily on just you want out of an LotFP product. If what you're hoping for is a clever and, in the best sense of the word, modular adventure scenario you can easily drop into an ongoing old school fantasy campaign, Disastrum is probably not for you. If, on the other hand, you're looking for looking for an imaginative and well-presented event-based scenario/hexcrawl set in 17th century Virginia, then Disastrum is exactly what you need.

Consisting of three clothbound A5-sized hardcover volumes, Disastrum gives an LotFP referee almost everything he – or should I say she, in keeping with the game line's style guide? – needs to run a lengthy and challenging scenario set in and around the Virginia Colony in the midst of an immense spatiotemporal accident caused by castaways from the Fifth Dimension. This accident has deformed both space and time, warping the landscape and its inhabitants, as well as creating portals to alternate times and realities.

Anyone with prior experience of LotFP will immediately recognize a trio of familiar elements in Disastrum: a 17th century locale (Virginia in 1633), an incursion by nonhuman "aliens" (the Fifth Dimensional castaways), and the unnatural consequences of their presence (the Warp). Taken together, these elements are the foundation of many (though by no means all) of LotFP's best-known adventures, so much so that I think it's become something of a joke among LotFP fans: "Oh, no! Yet another invasion of historical Earth by beings from another dimension and whose very presence poisons our world and fills me with dread!" I bring this up, because, while true to some extent, these elements can nevertheless can still be used to great effect and so they are in Disastrum.

Volume I is entitled Jamestown and Environs. At 96 pages, it provides useful information needed by the referee to begin the adventure, including an overview of the events that led to the Disastrum and a timeline of the Virginia Colony, from its founding in 1607 to 1633, when the scenario begins. What sets this volume apart from others of its kind is how practical it all is. For example, five pages are devoted reasons why the characters may have come to Virginia, each of which offers a different frame for subsequent events. There's also an overview of Jamestown, its buildings, and inhabitants, along with random tables for generating colonists, news/rumors, Scriptural citations, plantations, native villages, and more.

Random tables play an important role in Disastrum, as one might well expect, since a large part of the scenario involves traveling through the wilderness of Virginia. Volume I describes the terrain of the region, both natural and unnatural. The latter includes the Warp, where the effects of the Fifth Dimensional Incursion are strongest. For each region, there are keyed encounters, described in Volume II, as well as "omens and oddities" of various sorts – strange objects in the sky, objects falling from the sky, and "disastrumous hazards," which is to say, bizarre phenomena resulting from the Warp, such as gravity bubbles or time speeding up or slowing down.

Volume II, Lo! New Lands, is the biggest of the three books at 192 tables, describing all twenty keyed encounters in Virginia and twelve alternate worlds or realities accessible through the Eye of the Warp. The keyed encounters vary in both length and strangeness. Some, like the Escapees' Camp, consisting of indentured servants and slaves who've used the Disastrum as an opportunity to flee their masters, are relative simple and normal. Others, like the Speaking Swamp or Factory Fungus, are given great detail and are exceedingly weird – products of five-dimensional beings attempting to interact with a three-dimensional world and only partially succeeding. All of the encounters are compelling, whether simply by presenting the players with an aspect of 17th century colonial life or by challenging their wits against a consequence of the Warp.

Descriptions of the twelve alternate realities, called "spacetimes," take up about half of Volume II. Like the keyed locations, they vary in length and strangeness, though all are fairly strange. For example, there is the Post-Ant Empire, a spacetime ruled by biomechanical ants that displaced the dinosaurs. There's also the City of the Crawling Blood, an alternate London overrun with a strange sickness and the Wilder Wilderness, an alternate Virginia populated with megafauna, among many more. All but one of these is a side trek, a place of interest and danger but without any larger significance to the scenario. However, the Corpse City of the Western Gate, located in 18th century China, is ground zero for the cosmic event whose repercussions are felt more than a century earlier and a hemisphere away in Virginia. It's here that the scenario climaxes, one way or the other, as the character contend with extradimensional beings whose activities have the potential to doom the Earth and everyone on it.

Volume III, Prodigies, Monsters, and Index, is 128 pages long and, as its title suggests, focuses on the strange and unusual effects of the Disastrum. Thus we get more than 60 new monsters, most of them unique (as Raggi intended). Many can be encountered in and around the Virginia Colony, but others are the inhabitants of the various spacetimes to which the characters may travel. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Volume III presents random tables to enable the referee to create his own "new people," the name used to describe the fabricated three-dimensional bodies of five-dimensional beings and whose appearances and properties are quite surprising. It's all wildly imaginative and, as I said above, practical. With these three volumes, the referee has nearly everything he needs to run a memorable and demanding weird fantasy adventure.

Disastrum is exceptionally well done. It's the Masks of Nyarlathotep of Lamentations of the Flame Princess, in that it takes all the usual ingredients of a LotFP adventure and sharpens and heightens them to such a high degree that, after playing this long, open-ended scenario, you'll feel as if you've done LotFP. There will undoubtedly be excellent LotFP adventures in the future, but Disastrum has, for me. crystallized the game's essence and unique take on fantasy in a way that will be hard to top. Thats not say it's perfect. The scenario has a lot of moving parts that put a lot of weight on the referee's shoulders, even with all the random tables and examples provided. In addition, the standard edition lacks the foldout hex maps included with the deluxe slipcase edition. The hex maps aren't absolutely necessary, but I imagine most referee's would find them useful. Likewise, all editions (with the exception of the PDF version) are pricey, which might be an impediment to some prospective purchasers.

In the end, none of these mild criticisms should be held against A True Relation of the Great Virginia Disastrum, 1633, which is as close to a definitive LotFP product as you're likely to get. It's imaginative, well-written, and well-made and, despite its length, I found myself reading it almost compulsively. The combination of a nicely realized historical setting and fantastically weird encounters and situations seemed, to me, to be a near-perfect fulfillment of what Lamentations of the Flame Princess has, in recent years, striven to be. It's truly excellent. My only regret is that I don't presently have a place in my gaming schedule to run this adventure. I hope others who buy and read it will be more fortunate than I.

September 19, 2024

Western Gunfighter

Grenadier Models produced a line of historical miniatures under the name "Western Gunfighter" that were approved for use with TSR's Boot Hill.

I'm not certain when these miniatures were first released. I can find evidence online that they were at least advertised by Grenadier in 1978. Whether they were released in that year (or earlier), I can't say with any certainty. Even so, 1978 is prior to the release of Boot Hill's second edition in 1979, which is interesting. In addition to this large boxed set, there were also a number of smaller blister packs.

I'm not certain when these miniatures were first released. I can find evidence online that they were at least advertised by Grenadier in 1978. Whether they were released in that year (or earlier), I can't say with any certainty. Even so, 1978 is prior to the release of Boot Hill's second edition in 1979, which is interesting. In addition to this large boxed set, there were also a number of smaller blister packs. I've never seen any of them in the flesh, only photographs, so there's not much more I can say about them. Did anyone reading this own or see them?

September 18, 2024

Boot Hill Introduction (Part III)

The introduction to Boot Hill continues.

A campaign could be run with as few as 4 players and a referee, although a referee is not strictly necessary in smaller games, since players as a group can decide any questionable situations and together can put a check on any actions which tend to disrupt the smooth flow of a game (shooting anything which moves, for instance, quickly brings the wrath of the other players and the law down upon the head of the offender).

Once again, we see the distinction between a "game" and a "campaign." Equally interesting in my opinion is the suggestion that the players can not only handle certain aspects of play themselves without the need for a referee, but they can also be self-regulating in the sense of preventing one another from going against the spirit of the game. Nevertheless –

A referee is always preferable in any size campaign, and is a must for larger undertakings (which could easily encompass as many as 20 different roles). When the referee moderates the action, there is a secrecy aspect which the platers can work to advantage and which can greatly add to the interest of the campaign. Thus, the referee can relate information individually to each player depending upon the actions and position of his own character, and each character will have his own outlook on the game situation, since there will often be developments "behind the scenes" which will not be common knowledge to all. Likewise, secret plans can be made and related to the referee without the other players knowing of what transpires.

I've talked before about the need for large groups of players in our RPG campaigns, so I'm pleased to see that Boot Hill is yet another game that explicitly supports this kind of play. The discussion of secrecy is good, too. In my youth, I ran a short Top Secret campaign in which each of the three players was working for a different agency and all of them were tasked with adversarial goals. I also did something similar in my youthful Gangbusters campaign and that worked pretty well.

In a campaign situation, each player character will have his own identity and abilities (these are determined by dice rolling, with a slight advantage to allow player characters to be above the norm). If this character is killed, the player will have to take on another persona in the campaign (sometimes starting "from scratch" again in a similar character, or in a position which is completely unrelated to the former).

The idea that a player character should have "a slight advantage" so that he is "above the norm" is notable. Many post-D&D TSR roleplaying games included ability score generation schemes that were skewed in player character's favor.

Note, however, that in a large game, a player could conceivably take on the role of two different characters if carefully arranged and monitored by the referee. In such an instance, the two roles would have to be completely independent and not subject to conflict or possible cooperation. For instance, a player could have one role as a major rancher who is seeking to expand his holdings and another character who is an outlaw specializing in stagecoach robberies. Obviously, these two characters would have little cause to cooperate or conflict with each other, so such an arrangement would provide two characters for the campaign (assuming the referee was agreeable) rather than only one.

When I started playing RPGs, it was a widely accepted truth that no player should play more than one character in a session. However, most players had more than one character in the campaign and would often swap between them, based on interest and the context of the scenario on offer. That approach seems very similar to what's been suggested here.

Campaigns can be as small or as expansive as desired, centering on a single town or a large geographical area. Preparation can be minimal or as extensive as desired. While it is possible to structure rigid scenarios, free-form play will usually be more interesting and challenging. It is easy to set up a town, give a few background details, and allow the participants free rein thereafter. In no time at all lawmen will arrest troublemakers, gunfights will take place, and Wells Fargo will lose yet another payroll to masked outlaws. This game isn't named BOOT HILL without reason!

He makes it sound so easy!

Fortunately, there's an entire section of the rulebook dedicated to the creation and running of a Boot Hill campaign. I'll be taking a closer look at it in another series of upcoming posts.

Travel(ler) Times

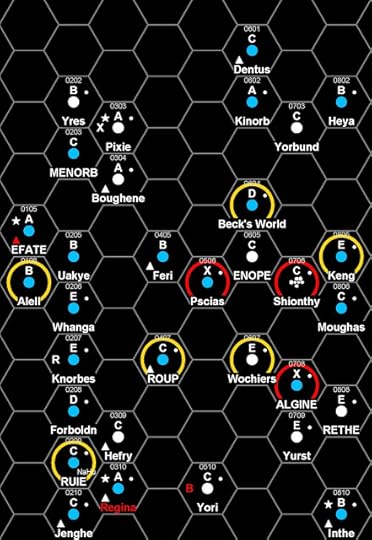

Back in the halcyon days of Google Plus – the only social media platform I've ever really liked – I floated the idea of starting up an open-ended, multi-group Traveller sandbox campaign set in a single subsector of space. For those unfamiliar with a subsector, here's an example:

Each hex represents a week's travel time in a starship outfitted with a Jump-1 drive. So, to travel from Regina (hex 0310) to Forboldn (hex 0206) would take two weeks – one to jump into either Ruie (hex 0209) or Hefry (hex 0309) and another to jump into Forboldn itself. Of course, Jump-1 is the least powerful form of jump drive, with others rated as high as Jump-6, the number being how many hexes it can travel in a single week. In my example, a starship equipped with a Jump-2 drive could thus reach Forboldn from Regina in a single week. And so on.

Each hex represents a week's travel time in a starship outfitted with a Jump-1 drive. So, to travel from Regina (hex 0310) to Forboldn (hex 0206) would take two weeks – one to jump into either Ruie (hex 0209) or Hefry (hex 0309) and another to jump into Forboldn itself. Of course, Jump-1 is the least powerful form of jump drive, with others rated as high as Jump-6, the number being how many hexes it can travel in a single week. In my example, a starship equipped with a Jump-2 drive could thus reach Forboldn from Regina in a single week. And so on.The relative slowness of interstellar travel is an important part of what makes Traveller the game that it is, regardless of whether the setting is GDW's Charted Space or a homebrew one. Since there is no faster means of communicating between star systems, information travels at the speed of the fastest ship available, much as did during the Age of Sail on Earth. This means that interstellar governments either have to delegate authority to local worlds or risk making decisions based on intelligence that may be weeks or even months out of date. This set-up creates a fun dynamic that's very conducive to adventure.

It also presents a bit of a problem for the kind of campaign I proposed on Google Plus. My idea was that I'd have several different groups of player characters operating within the same subsector, each starting on a different world. Their actions would be independent of one another and, unless they were significant in some way, they'd probably never even know about what the others were up to. However, I had hopes that, over time, each group would have sufficient impact on the worlds of the subsector that there'd be reverberations that could be felt elsewhere.

The difficulty was timing. If, for example, one group of characters, acting as mercenaries, helped overthrow the planetary government of Roup (hex 0407), word of that would travel slowly throughout the subsector. Depending on where the other groups of characters were, it might be some time before they heard of it. Furthermore, suppose one of those groups was adventuring on a single planet for weeks of real time, but only a few days of game time. They'd very quickly fall out of sync with the others, creating a timekeeping headache for me as the referee, since, as we all know, YOU CANNOT HAVE A MEANINGFUL CAMPAIGN IF STRICT TIME RECORDS ARE NOT KEPT.

It's not an insurmountable problem, to be sure. Gary Gygax does provide some genuinely helpful advice on how to manage groups engaged in different activities at different times within the same campaign in the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide. Nevertheless, it's still a lot to juggle in a way that allows regular play to proceed without interruption. If all the character groups spent no more than a single session on each world, this would be easier to manage, but that's unlikely to be the case. I don't want to enforce an artificial limit like "You must complete your mission on this world in four hours of play or else you must leave" to achieve the kind of campaign I want to run, but that seems to be the simplest way to achieve it and that's disappointing.

Am I missing something obvious? Is there a good way to referee an open-ended sandbox campaign with multiple character groups acting independently of one another without either artificial time limits or having to coordinate several out of sync timelines? If so, I'd love to hear about it.

September 17, 2024

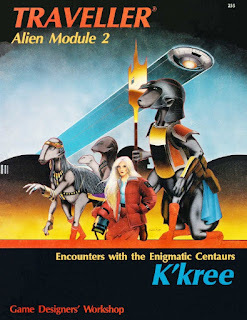

Retrospective: Alien Module 2: K'Kree

Traveller's Charted Space setting, home to the Third Imperium and its interstellar neighbors, is one I know very well. It's also one that I rank as my favorite imaginary setting – a testament to its near-perfect blend of originality and pastiche. Charted Space is a setting that's expansive enough to contain almost anything you can imagine in a space opera while still feeling distinctive. That's a more impressive feat than one might imagine, especially when one considers how often others have failed in the attempt.

Traveller's Charted Space setting, home to the Third Imperium and its interstellar neighbors, is one I know very well. It's also one that I rank as my favorite imaginary setting – a testament to its near-perfect blend of originality and pastiche. Charted Space is a setting that's expansive enough to contain almost anything you can imagine in a space opera while still feeling distinctive. That's a more impressive feat than one might imagine, especially when one considers how often others have failed in the attempt. One of the many ways by which Game Designers' Workshop achieved this was by subverting expectations. I mean that as a genuine compliment, not as a bit of nonsensical marketing speak. Very often, GDW would take a commonplace element of science fiction and ring a change or two on it so as to give it a different complexion, one unique to Traveller. Though they employed this technique throughout the game's product line, I feel as if they put it to best effect in their series of Alien Modules, beginning with Aslan in 1984. Aslan is a solid reworking of the "proud warrior race" trope, but I don't think anyone who reads it is going to be blown away by its content. That's not a knock against by any means, just an acknowledgment that it treads ground familiar to anyone who's a longtime sci-fi aficionado. From the Dorsai to the Klingons and Kzinti, the genre is replete with such races and cultures. Though I happen to think the Aslan are an interesting and well-done example of a proud warrior race, proud warrior races are a dime a dozen in both SF and fantasy. If you really want to impress me, you need to do something genuinely different.

That's exactly what GDW did with its second alien module, devoted to the "enigmatic centaurs" known as the K'Kree. Written by J. Andrew Keith and Loren Wiseman, this 40-page book was published the same year as its predecessor, but it's much more interesting. As you might notice from the cover image above (provided by the ever-awesome David Dietrick), the K'Kree are six-limbed beings, hence their nickname of "centaurs." That alone sets them apart, not just from humans or Aslan but from most alien races presented in science fiction. Of course, that's not the only thing that makes them unique, as I'll explain.

The K'Kree are the descendants of herbivorous grazers – like horses or cattle – that evolved to intelligence and eventually came to dominate their homeworld. The Alien Module explains that the K'Kree were not the only intelligent species to have evolved there. At least one other, known as the G'naak, also did so, against whom the K'Kree fought during ancient wars that also served to accelerate their technological development. The G'naak, unlike the K'Kree, were carnivores and were thus seen as an existential threat that demanded nothing less than genocide. With the G'naak wiped out, the K'Kree continued to develop, both culturally and technologically, until they eventually discovered jump drive and made their way to the stars.

The K'Kree are one of Traveller's so-called Major Races – one of the six species that discovered jump drive independently and established mighty interstellar states. The K'Kree's interstellar state, the Two Thousand Worlds, exists to trailing of the Imperium. Under its Steppelord, the Two Thousand Worlds is a deeply conservative polity dedicated to stability and protecting its people from outsiders, particularly meat-eaters, whose scent reminds the K'Kree of the long-defeated G'naak (who are akin to bogeymen in their culture). Revulsion of carnivores is so great among the K'Kree that, for example, they demand that ambassadors from other species abstain from eating meat for months before they will even receive them, among many other idiosyncratic practices.

Like their ancestors, the K'Kree prefer to travel in large groups. Among them, a desire to be alone – never mind enjoyment of it – is taken as a sign of insanity. They likewise hate enclosed spaces. All K'Kree would, by human standards, be considered claustrophobic, which is why their spacecraft are large and feature wide corridors and high ceilings. Alien Module 2 makes a good effort of explaining the mindset of the K'Kree and how it affects both their everyday behavior and the diplomacy of the Two Thousand Worlds. The K'Kree are a very alien race and rather unlike most of the nonhuman aliens encountered in popular science fiction.

That's a big part of why I hold Alien Module 2 in such high regard. At the same time, there's no denying that the K'Kree aren't really suitable for use as player characters – at least not easily. The module includes rules for doing so, along with an adventure designed to be used with K'Kree player characters. However, in my experience, it's just not practical in the long term, since K'Kree travel in large numbers, saddling a group of PCs with lots of additional servants, followers, family, and hangers-on that can get in the way of ordinary play.

Of course, that's the price for creating a genuinely alien species, with an unusual society, culture, and psychology. The K'Kree do, however, make for very memorable NPCs and in that role they're among the most interesting beings in Charted Space. The Traveller campaign in which I'm playing is set in a region of space not far from the Two Thousand Worlds and, while we've not yet run into the K'Kree directly, their presence is nevertheless felt. Indeed, the player characters have some trepidation about the possibility that these militant vegetarians might one day take notice of what's happening in our little corner of the universe. Good times!

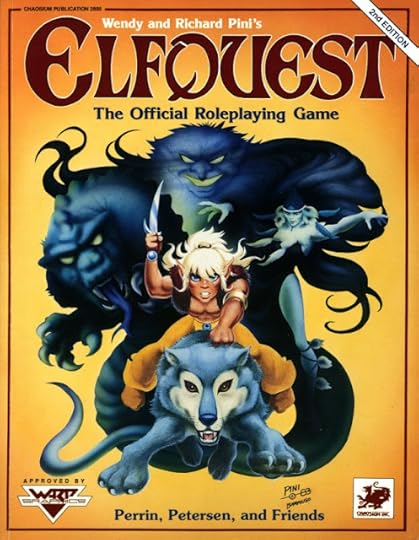

ElfQuest Returns

I've been an admirer of Chaosium boxed sets for a long time and consider many of them to be among the best RPG products ever released. That's why I was very quick to snap up the 40th anniversary reprint of Call of Cthulhu the company announced in 2021. Building on that success, Chaosium announced another re-release of a classic Basic Role-Playing-derived game, ElfQuest.

The remastered set will come in a 2" box and include not only the 2nd edition ElfQuest rulebook and related materials, but also The ElfQuest Companion, The Sea Elves, and Elf War supplements. Though I don't count myself a fan of ElfQuest, this announcement nevertheless makes me very happy. I love it when old RPGs are faithfully re-released for a new generation of fans to discover and appreciate. Chaosium has a very good track record when it comes to projects like this, so I think anyone who is an ElfQuest fan would do well to take a serious look at this.

The remastered set will come in a 2" box and include not only the 2nd edition ElfQuest rulebook and related materials, but also The ElfQuest Companion, The Sea Elves, and Elf War supplements. Though I don't count myself a fan of ElfQuest, this announcement nevertheless makes me very happy. I love it when old RPGs are faithfully re-released for a new generation of fans to discover and appreciate. Chaosium has a very good track record when it comes to projects like this, so I think anyone who is an ElfQuest fan would do well to take a serious look at this.

September 16, 2024

The Articles of Dragon: "The Big, Bad Barbarian"

As I've mentioned on multiple occasions, I looked forward to reading Gary Gygax's "From the Sorcerer's Scroll" columns in Dragon whenever they appeared. As Gygax himself regularly reminded his readers, his columns were (usually) the only articles in the magazine whose content was 100% official and approved for use with AD&D. Rabid AD&D player and TSR fanboy that I was at the time, this imprimatur thus meant a lot to me, because it ensured that I was permitted to make use of this new material in my campaign without reservation – and use it I did!

As I've mentioned on multiple occasions, I looked forward to reading Gary Gygax's "From the Sorcerer's Scroll" columns in Dragon whenever they appeared. As Gygax himself regularly reminded his readers, his columns were (usually) the only articles in the magazine whose content was 100% official and approved for use with AD&D. Rabid AD&D player and TSR fanboy that I was at the time, this imprimatur thus meant a lot to me, because it ensured that I was permitted to make use of this new material in my campaign without reservation – and use it I did!Like many (most?) gamers at the time, I'm not certain I ever played AD&D "by the book." Instead, my friends and I played a cobbled-together mishmash of Holmes, Moldvay, AD&D, and random bits of RPG "folklore" we picked up from Crom knows where. We still called what we were playing Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, of course, because that was the game to play and we all wanted to play it, but whether we actually were playing something Gary Gygax would have recognized as AD&D is an open question. What's important to understand for our present purposes is that we believed ourselves to be playing AD&D, hence why the new material Gygax presented for use with AD&D in Dragon was so important to us.

My first experience of Gygax's additions had come in issue #59 (March 1982) with his introduction of cantrips. While these minor spells were interesting, they were never widely adopted in our group, unlike those that began to appear a few issues later. A good example of what I am talking about is "The Big, Bad Barbarian," which appeared in issue #63 (July 1982). As its title suggests, this article gave us our first peek at the barbarian character class that would later be included in Unearthed Arcana several years later. Since this was the first new – and official – addition to the line-up of AD&D character classes, I was very excited to see it.

I also perplexed by it. My own sense of what a "barbarian" was had been informed by two sources: ancient history and fantasy literature, particularly Howard's stories of Conan the Cimmerian. The class that Gygax presented in issue #63, with its proficiencies in survival and suspicion of magic, was vaguely reminiscent of both, but still somehow its own distinct thing. I didn't hate the class, but neither did I wholeheartedly embrace it as I would other new Gygaxian classes. I suppose it's fair to say that, in principle, I was attracted to the idea of a barbarian class. I simply wasn't yet sold on the AD&D version.

Part of the reason why I felt this way is that Gygax's barbarian broke a lot of standard AD&D "rules." For example, the barbarian's ability scores were generated according to its own unique methods, unlike even those presented in the Dungeon Masters Guide. Strength is generated by rolling 9D6 and picking the three highest, while Constitution uses 8D6 (Wisdom, interestingly, is generated by rolling 4d4). Furthermore, barbarians get double the benefit for high Dexterity and Constitution scores, both of which they'll almost certainly have, given the way the scores are generated. The class also began play proficient in even more weapons than a fighter, in addition to many other special abilities. Even to my twelve year-old self, it all seemed a bit much.

Nevertheless, I dutifully attempted to make use of the new class. One of my friends asked if he could convert his longtime fighter into a barbarian, since he'd always imagined him as a barbarian. I agreed, since it gave us the perfect opportunity to give the barbarian a whirl, just as Gygax suggested we do. The results were ... mixed. In play, we found the barbarian exceedingly tough in combat and its various abilities useful. However, in its Dragon iteration, the class was utterly forbidden from using magic weapons, which hampered its ability to take on many powerful monsters. I imagine this was intended to be balance out its other strengths, but, in the end, it proved crippling and my friend asked to return his character to being a fighter, which I happily permitted.

My first experience with a new, official class for AD&D ended in disappointment. This made me wary of all future classes Gygax presented in "From the Sorcerer's Scroll, though, as we'll see in future posts in this series, my wariness did not sour me on the idea of new character classes in general. But the barbarian, in either its original version or its "improved" one in UA, never won me over. I retain a fondness for the concept of a barbarian class, as I've explained before. I simply haven't yet found (or created) one that I like well enough to use. One day!

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers