James Maliszewski's Blog, page 38

November 4, 2024

The Articles of Dragon: "Old Dwarvish is Still New to Scholars of Language Lore"

I promise this is the final article from issue #66 of Dragon (October 1982) that I'll talk about! However, since I'd already posted about the others devoted to languages in Dungeons & Dragons, I felt I'd be remiss not to do so for this one as well.

I promise this is the final article from issue #66 of Dragon (October 1982) that I'll talk about! However, since I'd already posted about the others devoted to languages in Dungeons & Dragons, I felt I'd be remiss not to do so for this one as well. "Old Dwarvish is Still New to Scholars of Language Lore" by Clyde Heaton is short in length and unusual in its approach. The piece purports to be the notes of "that illustrious pursuer of knowledge," Boru O'Bonker concerning the ancient language of Old Dwarvish. The language is no longer spoken regularly by dwarves, but exists as their ceremonial and traditional language. It survives mostly in poetry and religious rites and occasionally in old expressions and colloquialisms. The framing device of the article suggests that knowledge of the language is kept from outsiders, which is why O'Bonker is now on the run from "very short, heavily armed gentlemen" who had "a professional interest in him."

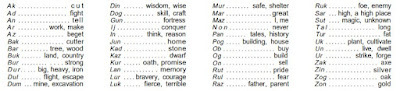

What then follows is a brief discussion of the phonology, grammar, and vocabulary of Old Dwarvish. When I say "brief," I'm not kidding. For example, here's the entirety of the vocabulary presented with the article.

The grammar presented is similarly limited, presenting only the basic structure of Old Dwarvish sentences and the structural relationships between nouns, adjectives, and verbs. Within the context of the framing device, this is because O'Bonker is focused on unraveling the mystery of this ancient tongue. He doesn't yet have all the pieces, so his notes are, therefore, incomplete. That's a clever explanation, but one is then left with a question: Why? What's the purpose of this article, if not to provide the reader with a reasonably complete Old Dwarvish language to use in his adventures and campaign?

The grammar presented is similarly limited, presenting only the basic structure of Old Dwarvish sentences and the structural relationships between nouns, adjectives, and verbs. Within the context of the framing device, this is because O'Bonker is focused on unraveling the mystery of this ancient tongue. He doesn't yet have all the pieces, so his notes are, therefore, incomplete. That's a clever explanation, but one is then left with a question: Why? What's the purpose of this article, if not to provide the reader with a reasonably complete Old Dwarvish language to use in his adventures and campaign?I have long suspected that the purpose of this article was, in fact, to show how little of a language a referee needed to create in order to make use of it in an adventure as a puzzle to be solved. In my youth, it was not at all uncommon for an important clue or piece of information in a dungeon to be hidden through the use of a cypher or an alphabet the referee made up. The players had to figure out a way to understand it and doing so was vital to moving forward. Most often, these cyphers used substitution or a similarly obvious method of hiding its information. More industrious referees would employ more elaborate methods. That's what I think Heaton is doing here, but I really can't say for certain.

Regardless of the author's actual intention, I was inspired by it to create my own partial languages for use in my Emaindor setting. I created fragments of Elvish (two varieties), Almerian (a Latin analog), Emânic, Tulikese, and more. I was no linguist, just a kid with an interest in foreign languages and a lot of time on his hands. So, I did my best to try to choose distinct sounds for each language and then a basic structure for sentences and enough vocabulary to name places and characters, as well as to, occasionally, make use of little phrases for color. I still have most of them in a binder my mother gave to me years ago, just before she sold my childhood home. They're nothing special but they were among my earliest attempts to create a coherent, "realistic" fantasy setting, so I retain an affection for them, which is why this article, despite its limitations, is one I look back on with similar affection.

Bafflement and Intrigue

Something I remember very vividly about growing up is that I'd sometimes find evidence of a popular culture I'd never encountered. Take, for example, Judge Dredd.

Until I started reading White Dwarf, I don't think I had any real understanding of who Judge Dredd was. I certainly had never read any comic book in which he appeared and, even if I had, I'm not sure if I'd have understood and appreciated the cultural context out of which the character arose. Consequently, whenever I did brush up against Dredd, I was left feeling both baffled and intrigued – baffled, because what little I had gleaned about him made little sense to me and intrigued, for precisely the same reason. I wanted to know more, if only to make sense of all the fleeting references to him on this side of the Atlantic, but it wasn't easy.

Until I started reading White Dwarf, I don't think I had any real understanding of who Judge Dredd was. I certainly had never read any comic book in which he appeared and, even if I had, I'm not sure if I'd have understood and appreciated the cultural context out of which the character arose. Consequently, whenever I did brush up against Dredd, I was left feeling both baffled and intrigued – baffled, because what little I had gleaned about him made little sense to me and intrigued, for precisely the same reason. I wanted to know more, if only to make sense of all the fleeting references to him on this side of the Atlantic, but it wasn't easy.Perhaps it's just a consequence of getting older, but I miss the days when I would feel baffled and intrigued by an artifact of some far-off sub-culture. That almost never happens anymore, thanks to the Internet. Assuming I even find something weird from a foreign land – an increasing rarity in the global village in which we're all now imprisoned – it doesn't take much time to find an explanation online. Long gone are the days when I'd be forced to puzzle out who some comic book character I'd never heard of was. Enlightenment is almost instantaneously within reach.

You'd think I'd be happy about that. My younger self would probably have loved to have had access to the Internet. Back then, I didn't enjoy being in the dark. I wanted to know everything about everything, especially when it came to nerdy matters, like science fiction or fantasy. Now, though, I find myself looking back wistfully at the days of my youth, before the emergence of the pop cultural beige slurry seeping into every nook and cranny of our wired world. I miss the days when not everywhere felt the same and I could luxuriate – and occasionally be frustrated by – the differences wrought by distance.

The past is a foreign country that I'll never again get to visit.

Amalaric the Ill-Tempered

When I attended Gamehole Con this year, I decided I wouldn't referee any games, but would instead play in several. I did this for a couple of reasons. First, I'm usually the referee, so having the opportunity to play is a treat (even though I'm actually quite bad at it). Second, I intend to run some sessions at future Gamehole Cons – and perhaps some other cons, too, if I can decide on others to attend – and wanted to do some "field research" on what these games are typically like. Though I'm a pretty experienced and, if my players are to be believed, good referee, I'm nevertheless quite self-conscious about my abilities. Seeing how others handle the referee's duties at a con thus provided me with some very useful information.

The very first game I played at the con was Hyperborea. I've been a fan of the game since its original edition, released more than a decade ago. It's a delightfully game, inspired by the greats of pulp fantasy, like Howard, Lovecraft, and Smith. Rules-wise, it's pretty much a rationalized and house ruled version of AD&D and, like AD&D, Hyperborea is baroque and idiosyncratic. To tell the truth, that's a big part of why I like the game so much. I appreciate it when a designer imbues his game with himself – his likes and dislikes, his philosophy and worldview – that's just what Jeff Talanian did with Hyperborea. That's a welcome break from recent attempts to sand down the rough edges of our popular culture to make it appeal to everyone, in the process making it appeal to no one in particular.

Like most con games, this one had a four-hour time slot and featured six players. Entitled "A Tale of Crows and Shadow," it was, so far as I know, an original adventure by our referee. Before we began, he passed out a stack of pregenerated characters from which to choose. I selected a warlock – a fighter/magic-user, more or less – named Amalaric the Ill-Tempered. After everyone had chosen their characters, the referee then asked if we all had dice. Embarrassingly, I did not. I was sitting next to the referee and, as I explained that I had no dice, he turned, looked at me, and asked, "Are you sure you're in the right place?" He meant it humorously, of course, but I can't deny feeling a little sheepish at his words. Fortunately, a player seated across from me tossed me a bag of dice and told me to keep them. "I always carry extras for times like this."

The adventure began with all of the characters awakening aboard a slave galley headed out to sea. Our food and drink had been drugged after a night's debauchery in the metropolis of Khromarium. Below decks and chained to our oars, we first had to find a way to escape. The first half of the scenario involved us plotting to free ourselves and then take control of the vessel. After many extraordinary feats of Strength (and Dexterity) and much combat, we were successful. Now in command of the ship, we had to pilot it back to land without quite knowing where we were. Once there, we trekked through the wilderness at night, while someone (or something) was following us. Eventually, we discovered that our stalker was a vampire – and a child vampire at that. Dealing with her was creepy, unnerving, and surprisingly difficult, but we eventually prevailed.

I had a lot of fun playing this adventure, which felt very picaresque in its structure. This wasn't a scenario in which everything that happened in it was directly connected. Instead, one thing happened after another, each being a kind of mini-scenario of its own. It was a bit like a series of pulp fantasy vignettes, all sharing the same cast of characters, but not having any overarching plot or theme. I was quite fine with that. Not only did it suit Hyperborea, but it also gave the session a "light" feeling. We weren't following some grand storyline or trying to achieve anything beyond saving our skins and escaping the latest danger we stumbled upon.

Not being a veteran of con games, I'm not sure how typical my experience was. One of the most notable things about it, to my mind anyway, is that the players were frequently willing to take chances on harebrained schemes and reckless gambits. That might be a function of the fact that everyone knew this was a one-shot. Our natural self-preservation instincts were blunted. If our character died while trying to bowl over a group of guards, Captain Kirk style, so what? We were having good, pulpy fun and that's all that mattered. As I think about the possibility running my own games at a future con, I'll bear this in mind. I think a good convention adventure is probably its own thing, distinct from the kind of adventure that works well in a campaign situation.

Anyway, Hyperborea's a fun game. I should play it more (and so should you).

November 3, 2024

High Adventure and Low Comedy

Free League publishes not one, not two, but three different fantasy roleplaying games at the moment – Forbidden Lands, Symbaroum, and now Dragonbane. Each one is quite distinct from one another, not just in terms of rules but also in tone. For example, Dragonbane, the latest iteration of the venerable Swedish RPG, Drakar och Demoner, sets itself apart from the other Free League fantasy RPGs by its willingness to embrace lighter, even sillier moments, as designer Tomas Häremstam points out in his preface:

Free League publishes not one, not two, but three different fantasy roleplaying games at the moment – Forbidden Lands, Symbaroum, and now Dragonbane. Each one is quite distinct from one another, not just in terms of rules but also in tone. For example, Dragonbane, the latest iteration of the venerable Swedish RPG, Drakar och Demoner, sets itself apart from the other Free League fantasy RPGs by its willingness to embrace lighter, even sillier moments, as designer Tomas Häremstam points out in his preface:Though a toolbox for allowing you to tell fantasy stories of all kinds, Dragonbane is a game with room for laughs at the table and even a pinch of silliness at times – while at the same time offering brutal challenges for the adventurers. We call this playstyle mirth and mayhem roleplaying – great for long campaigns but also perfect for a one-shot if you just want to have some quick fun at your table for the night.

Dragonbane is quite an interesting RPG for a number of reasons and I hope to get around to discussing it at some point, but there are several other games and gaming products ahead of it in my review queue. However, the "mirth and mayhem" tagline really caught my attention, in part because it reminds of a phrase my friends and I have used for years – high adventure and low comedy.

I can't quite recall precisely when we coined this phrase, but we did so as a way to capture what the experience of playing most RPGs was actually like at the table – not what its designers wanted to be like, which is quite a different thing. This is an important distinction. With a handful of exceptions, like Paranoia or Toon, whose stated intention is to be humorous, most roleplaying games are written and meant to be played seriously. "Serious" doesn't mean utter devoid of humor, of course, but the humor is accidental, a natural consequence of the unpredictability of playing any game, especially one where player choice and dice rolls contend with one another.

What my friends and I call "high adventure and low comedy" is thus very often (though not exclusively) the result of exactly this: dice with a mind of their own. One of my most popular posts touches on this very topic, though from a slightly different angle. However, the point remains the same, namely, that it's well nigh impossible to avoid moments of unexpected levity when so many of a character's actions are determined by the roll of dice. There's simply no way to ensure that even a high-level and competent character will always succeed at the right moment. Instead of making his save against dragon breath, he might fail and be burnt to a crisp. The reverse is also possible and the all-powerful Dark Lord might, metaphorically speaking, slip on a banana peel as he attempts to menace the heroes who've dared to confront him in his lair.

Over the years, I've experienced many examples of this. In my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign, the character Aíthfo hiZnáyu has fallen prey to bad dice rolls on several notable occasions. And while I used those unintended mishaps as an opportunity to introduce new elements to the campaign, there's no denying that they were also funny – so much so that the players continue to chuckle about them years later. House of Worms has never been a deliberately funny campaign. Tékumel, with its detailed history, ancient mysteries, and constructed languages is perhaps the very definition of serious business when it comes to RPGs and yet there's no way to prevent unexpected silliness from creeping in from time to time – nor would we want to do so!

Dice rolls that go awry aren't the only source of humor. Players are every bit as unpredictable as dice. Sometimes, a player might just be in a whimsical mood and decide that his character does something goofy. Other times, he might be bored and want to shake things up by choosing to act in a way that's, in his opinion, more entertaining. Or maybe someone misspeaks, calling a character by the wrong name or accidentally – or, worse, intentionally – making a pun that causes everyone to erupt into laughter. There are simply so many ways that a roleplaying game session can descend into unintentional humor that there's no point in worrying about it. Instead, it's best to embrace it these moments of levity and enjoy them for what they are.

I think that's why, when I came across the passage I quoted above, I was so taken by it. Over the years, I've read a lot of roleplaying games. Very few of them acknowledge that low comedy is very often the inescapable companion of high adventure. You can't really have one without the other, not without clamping down so hard on anything that deviates in even the slightest way from the Truth Path that, in the process, you've also sucked all the fun out of roleplaying. These are games, after all and they're meant to be fun. They're also exercises in human creativity and interaction, both of which often take us to unexpected places.

Isn't that why we play these games in the first place?

November 1, 2024

Vague Recollections

One of the many downsides of our increasingly disembodied, virtual existence is the ease with which everything disappears into Orwell's memory hole. Anything produced online, especially on a platform you don't own – like this blog, for instance – could go away tomorrow if someone in an office somewhere decides it should be so. Those of us who can still recall the existence of Google Plus know all too well what I am talking about. Now, it's true that nothing lasts forever in the sublunary world, but I can't help but feel this is especially so when it comes to Internet scribblings.

I thought about this yesterday, as I tried to locate something I remember reading online back in (I think) the 1990s. Yes, I know: in Internet terms, the '90s might as well have been 300 years ago, not merely 30. Furthermore, the thing I want to find had been posted to one of the many Usenet newsgroups dedicated to roleplaying games, like rec.games.frp, so the odds of my finding it were never great to begin with. Still, I held out hope that, with enough perseverance, I might succeed. Since I was unsuccessful on my own, I thought I'd turn to my readers, many of whom possess far greater skills than I when it comes to locating obscure information.

I recall reading a narrative from the perspective of a Call of Cthulhu investigator. Unlike his colleagues, this investigator didn't go out into the field. Instead, he stayed safely at his home in Arkham or wherever and communicated with his comrades via telephone. In his phone conversations, he made certain that his interlocutor never told him too much about what he had seen or done, lest he have to make a SAN roll – "Don't tell me what you read in the book. Don't even tell me the title of the book," "No, I don't want to know what the creature looked like," etc. The whole thing was a meta-commentary on the way to "win" at Call of Cthulhu. I remember finding it quite amusing when I first read it.

Now, it's probably gone and I have only my increasingly hazy memories of it. Does this ring any bells with anyone else? Might anyone be able to suggest how I might find it again? I don't hold out much hope of ever reading it again, but I figured that, if anyone could aid me, it might be my readers.

Thanks!

October 31, 2024

REPOST: Fantasy is Frightening

(This month, I'd intended to write a longer post about the domestication of horror and frightening things in our popular media, including RPGs, but, as so often happens, time slipped away and here we are on Halloween and I never wrote that post. I still intend to write it; I just can't be sure when. In the meantime, enjoy this old post that touches on the topic. –JDM)

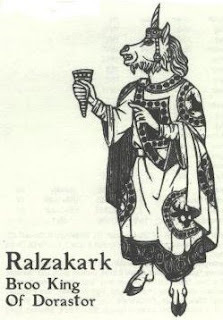

(This month, I'd intended to write a longer post about the domestication of horror and frightening things in our popular media, including RPGs, but, as so often happens, time slipped away and here we are on Halloween and I never wrote that post. I still intend to write it; I just can't be sure when. In the meantime, enjoy this old post that touches on the topic. –JDM)In RuneQuest, there is a race of beings known as Broos or goatkin. In my second edition rulebook, they're described as

Human-bodied and goat-headed, [they] ... are tied irrevocably with the Rune of chaos. They are given to atrocities and foul practices, and carry numerous loathsome diseases.Broos have the ability to procreate with any species, intelligent or otherwise, with the resulting offspring taking characteristics from both its Broo and non-Broo parent. Most Broos in the Dragon Pass area (the area of Glorantha originally most detailed in RQ's early materials) have the heads of goats and other herd animals, hence their nickname, but Broos come in a variety of types, depending on their parentage.

Anyway, during the RuneQuest Renaissance of the '90s, a product was put out for RQ3 called Dorastor: Land of Doom, which detailed a Chaos-tainted land to the south of the Lunar Empire. As I've stated several times before, I never played much RuneQuest at any time, but I was often interested in it. Just before Avalon Hill was purchased by Hasbro in 1998, the company was selling off its stock of RuneQuest materials in very cheap -- and hefty -- bundles. I bought them out of curiosity and it was then that I first read Dorastor. The supplement included a NPC known as Ralzakark, leader of Dorastor and king of the Broos.

For reasons I can't fully articulate, I found Ralzakark quite frightening. Perhaps it was because he had the head of a unicorn, a creature normally associated with purity and goodness. Perhaps it was because he was an urbane, sophisticated creature unlike his subjects. Whatever it was, Ralzakark frightened me. I don't mean scared in that ooga-booga-monster-in-closet sort of way; I mean in some psychological/emotional way. Ralzakark was a disturbing NPC -- and fascinating too. For all I know, I may be the only person who finds the Unicorn Emperor of the Broos unnerving, but I suspect not. I know of many people who find the Broos more than a little creepy and Ralzakark's inversion of many of the known facts about these creatures probably does unsettle people besides myself.

This got me to thinking about how the best fantasies, the ones that really stick with me, are frightening on some level. Shelob, in The Lord of the Rings, frightens me and so does Gollum, come to think of it. They both touch on things within my psyche that I'd rather not think about and force me to confront them. Most of us, I imagine, need to do this from time to time, which is why I think it's healthy for children's stories to include frightening elements. It's the same reason I think RPGs shouldn't shy away from being frightful. That's not all they should be, of course. Still, I think they're a lesser entertainment than they can be if they neglect to include things to unnerve us from time to time.

October 30, 2024

Retrospective: The Travellers' Digest

Fanzines have a long history in fandoms of all kinds, going back at least as far as the 1920s, when science fiction and fantasy increased their reach (and popularity) through pulp magazines like Weird Tales and Amazing Stories. Unsurprisingly, the hobby of roleplaying – and, by extension, its fandom – followed a similar trajectory, building on the already existing traditions of 'zine making. Just as many of the people who created the first RPGs had previously contributed to wargames fanzines, so too would many of the contributors to the emerging scene for roleplaying 'zines go on to create or contribute to later RPGs. Fanzines thus served as a kind of "training ground" for new and often, though not exclusively, young writers hoping to make a name for themselves.

Fanzines have a long history in fandoms of all kinds, going back at least as far as the 1920s, when science fiction and fantasy increased their reach (and popularity) through pulp magazines like Weird Tales and Amazing Stories. Unsurprisingly, the hobby of roleplaying – and, by extension, its fandom – followed a similar trajectory, building on the already existing traditions of 'zine making. Just as many of the people who created the first RPGs had previously contributed to wargames fanzines, so too would many of the contributors to the emerging scene for roleplaying 'zines go on to create or contribute to later RPGs. Fanzines thus served as a kind of "training ground" for new and often, though not exclusively, young writers hoping to make a name for themselves.While Dungeons & Dragons, by virtue of its being the first and most popular roleplaying game, had a very enthusiastic fanzine culture, it was not the only RPG that did so. Those slightly older and better connected than I could probably speak at great length about the vibrancy of the 'zines devoted to, say, Tunnels & Trolls or RuneQuest, two games that I know had fanzines devoted to them. Not having been a player of either of those games in my youth, I don't have much to say on that front – or indeed about the 'zines written by fans of most other roleplaying games. The main exception is, of course, Traveller, a game I've played and adored since I first encountered it sometime in 1982.

The interesting thing about Traveller fanzines is that some of them were, in fact, officially licensed and associated with a third-party game company producing material for use with Traveller. For example, FASA, which would later publish Star Trek the Roleplaying Game and BattleTech (né Battledroids), began its existence as a Traveller licensee. During those days, FASA produced not one but two 'zines, Far Traveller and High Passage. One might argue that these periodicals aren't actually "fanzines" at all, but closer to prozines and I'd be willing to concede the point if it weren't for the fact that these periodicals were still very amateurish, produced on a shoe-string budget and written by and for fans. And, of course, one might counter by saying the entire RPG hobby, including the companies that service it, have never really stopped being amateurish, so it's a distinction with only a very small difference.

All of this is a roundabout way of saying that, before the Internet, Traveller had a number of well-done and influential fanzines that straddled the line between purely amateur and truly professional, often involving writers and artists who worked on both sides of the line, like the Keith Brothers. I read a number of them on and off, but I never became a regular reader of any of them until the appearance of The Travellers' Digest in 1985. Published by Digest Group Publications, the (theoretically) quarterly periodical was clearly modeled on GDW's own The Journal of the Travellers' Aid Society, though, to be fair, most fanzines for Traveller looked to JTAS for inspiration.

What distinguished The Travellers' Digest (hereafter TD) was not its format but its content. Each issue presented an adventure scenario that was part of a looser, large narrative – the so-called "Grand Tour," in which a quartet of characters, including a highly advanced sentient robot, traveled across the Imperium and reported on their experience to the eponymous The Travellers' Digest, which is presented as an in-universe magazine. Each adventure highlighted a different region of the Third Imperium, providing players and referees alike with information they could incorporate into their campaigns, even if they didn't make use of the Grand Tour meta-narrative.

I could have cared less for the Grand Tour, especially since the adventure presupposed the use of four pregenerated characters, none of whom, not even the robot, held much interest for me. However, I loved all the additional details the writers provided about the Imperium, its worlds, cultures, and history through the vehicle of the Grand Tour scenarios. I talked recently about "jump dimming," for instance, and that's a good example of the kinds of things TD did often: present clever new details about the Imperium so that it started to feel like a real place, with its own unique societies and cultures.

GDW had already provided plenty of details about the Third Imperium in its own publications, but TD did so in a way that felt very organic and, above all, playable. The magazine (mostly) didn't just present high-level lore dumps without consequence to the characters. Instead, the information played a part in a scenario and the characters' encounters with it made sense. Thus, if a scenario were set on Capital, the Imperium's seat of government, the workings of the Moot aren't just chrome but significant to the adventure in some way. DGP managed to pack a lot of great information into their adventures, occasionally even stuff that was truly setting-changing (like the revelation about how the alien Aslan came to possess jump drive).

The Travellers' Digest ran from 1985 until 1990, producing 21 issues in total before morphing into The MegaTraveller Journal, which lasted only three issues before the company folded – a victim of, among other things, the changing fortunes of GDW and indeed Traveller itself. I have a special affection for TD, because it was being produced around the time that I first started to take an interest in writing professionally. Though I never wrote for TD itself, I did write for The MegaTraveller Journal and, through it, made many friends with whom I am still in contact today.

Traveller is the only RPG fandom in which I've ever been deeply immersed and 'zines, whether fan or pro, were a big part of how I've interacted with that fandom and its members. Consequently, I have strongly positive feelings about these periodicals, so much so that, five or six years ago, I briefly considered producing my own Traveller fanzine. I never followed through with it for various reasons, but the thought still crosses my mind from time to time. Who knows? Maybe one day I'll do it.

October 29, 2024

A Birthday Gift

Today is my birthday, so I'm mostly taking it easy. However, my definition of "taking it easy" includes working on the current manuscript for Secrets of sha-Arthan. In this latest iteration, I've eliminated race-as-class, in large part because I wanted to open up greater possibilities for players of nonhuman characters, like the Ga'andrin.

Originally, I'd imagined that the Ga'andrin as eschewing sorcery entirely, Then, I thought about relegating their sorcerers to the realm of NPCs. However, after seeing Zhu Bajiee's latest artwork for me, I knew I couldn't deprive players of the opportunity to play one of these guys. As usual, he did a great job of bringing my vague ideas to life. I can't wait to finish the rulebook and share it with the world.

October 28, 2024

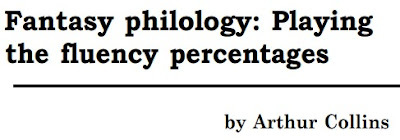

The Articles of Dragon: "Fantasy Philology: Playing the Fluency Percentages"

Clearly, issue #66 of Dragon (October 1982) was a memorable one for me, because I'm – once again – devoting a post to one of its articles. To be fair, both of the previous two posts concerning this issue were also about a favorite topic of mine, languages, so it was probably inevitable I'd write about them. Even so, I'd hazard a guess that there will be comparatively few issues to which I'll return multiple times in this series, which probably says more about my own tastes than the quality of individual Dragon issues.

Clearly, issue #66 of Dragon (October 1982) was a memorable one for me, because I'm – once again – devoting a post to one of its articles. To be fair, both of the previous two posts concerning this issue were also about a favorite topic of mine, languages, so it was probably inevitable I'd write about them. Even so, I'd hazard a guess that there will be comparatively few issues to which I'll return multiple times in this series, which probably says more about my own tastes than the quality of individual Dragon issues."Fantasy Philology: Playing the Fluency Percentages" by Arthur Collins (an author I hold in particularly high regard) is among a handful of articles I remember quite vividly, right down to being able to quote portions of the following dialog, which kicks it off:

Collins uses this dialog to illustrate what he thinks D&D sessions "ought to sound like (sort of)" but rarely do. His point isn't so much that he expects every player, let alone the referee, to make use of "accents and characteristic speech patterns." However, Collins does believe that "language differences can add a lot to a campaign, especially in terms of the challenge of communicating with people (and monsters) who speak other tongues and dialects." The dialog above is intended to show that these differences might extend even to members of common character classes and races.

Collins uses this dialog to illustrate what he thinks D&D sessions "ought to sound like (sort of)" but rarely do. His point isn't so much that he expects every player, let alone the referee, to make use of "accents and characteristic speech patterns." However, Collins does believe that "language differences can add a lot to a campaign, especially in terms of the challenge of communicating with people (and monsters) who speak other tongues and dialects." The dialog above is intended to show that these differences might extend even to members of common character classes and races. Collins then goes on to propose that each Dungeon Master get a handle on all the major languages in his campaign and how they relate to one another. Like A.D. Rogan, Collins is a fan of using language trees to aid in understanding the relationships between languages. However, unlike those in Rogan's article, which are mostly just ornamental, Collins's trees serve a purpose in the new language rules he proposes. These rules are the real meat of his article and why I was so taken with them back when I first read them more than four decades ago.

Under the standard rules of (A)D&D, a character either speaks and understands a language or he does not. Whether he does so is a function of his Intelligence score, his class, and his race. For most people, I suspect that's fine, but it's not what I wanted for my games. By this time, I'd been playing Call of Cthulhu for some time already and I liked its language rules. I wanted something similar in my D&D games and this article provides that. In fact, it provides more than that since, as I said, it takes into account how closely related on language is to another to determine a character's ability to understand and be understood.

I make it sound more complicated than it actually is. Collins gives each character a fluency percentage in each language he knows, based on his Intelligence score, his level, and a few other factors. These establish how well he can make himself understood to speakers of the same language. These percentages are modified when trying to speak to someone fluent in a related language, depending on how closely related it is. The more distantly related it is, the harder it is to make oneself understood. It's a very straightforward set of rules – simple really, but still more complex than anything in any edition of Dungeons & Dragons with which I'm familiar.

One of the conclusions to which I've come, after decades of playing RPGs, is that we all use the rules we think are most important to the kind of play we want and tend to downplay or even outright ignore the rest. I've never cared a lot about combat, so I prefer simple, uncomplicated systems. On the other hand, I like dealing with languages and communication, so I appreciate attempts like this article to model better the nature of learning, speaking, and understanding different languages. Based on my own experiences, most gamers don't feel the same way, which is probably why I tend to remember articles like this one when they appear.

King and Aces

Marc Miller, creator of Traveller, and one of the three founders of Game Designers' Workshop also attended Gamehole Con this year, as he does most years. I first met Marc many years ago, at the Origins Game Fair in 1991, which was, I believe, the last time the con was held in my hometown of Baltimore. I was a member of a Traveller fan organization called the History of the Imperium Working Group (HIWG) and several of us present at the con wanted to pitch some ideas to GDW for (Mega)Traveller adventures and supplements. We wound up going out to dinner with Marc, Chuck Gannon, and the Japanese translators of Traveller. We didn't succeed in our quest, but I did have the chance to meet several wonderful people, including Marc, with whom I've stayed in contact over the years.

Marc Miller, creator of Traveller, and one of the three founders of Game Designers' Workshop also attended Gamehole Con this year, as he does most years. I first met Marc many years ago, at the Origins Game Fair in 1991, which was, I believe, the last time the con was held in my hometown of Baltimore. I was a member of a Traveller fan organization called the History of the Imperium Working Group (HIWG) and several of us present at the con wanted to pitch some ideas to GDW for (Mega)Traveller adventures and supplements. We wound up going out to dinner with Marc, Chuck Gannon, and the Japanese translators of Traveller. We didn't succeed in our quest, but I did have the chance to meet several wonderful people, including Marc, with whom I've stayed in contact over the years.Marc held several panels, one of which was devoted to the history of GDW. Every person who arrived in the conference room was given a deck of cards Marc had printed through DriveThruRPG. He's a big fan of specialized decks of cards and often brings them for sale at conventions. The decks he gave us were devoted to the topic of the panel. The face cards all featured important people in the history of the company, like Marc Miller, Loren Wiseman, and Frank Chadwick, while the number cards all featured games it had published, like Traveller, Twilight: 2000, or Space: 1889 (along with lots of wargames, of course).

During the panel, Marc would go around the room, point to someone and ask them to draw a card randomly from the deck they'd been given. After doing so, the person would then read what was on the card and Marc will talk for a while about the person or game in question. In this way, the cards provided some focus for the discussion rather than relying solely on audience questions. Another benefit is that light was often shed on individuals or games that might otherwise not get discussed, like Chaco, a wargame about the 1932–1936 war between Bolivia and Paraguay. The game is one of Miller's earliest designs and was created, in part, as an educational tool to teach about South American history.All the panels at Gamehole Con were too short – only an hour. They were all held in the same room, with a new one starting every hour on the hour, all day, every day. That meant that there was often a rush toward the end of each panel that caused a fair bit of disruption, as overzealous gamers tried to enter an ongoing panel before it was actually ended. I would have much preferred fewer, longer panels, so that we could luxuriate a bit in the stories and memories of the guests.

During the panel, Marc would go around the room, point to someone and ask them to draw a card randomly from the deck they'd been given. After doing so, the person would then read what was on the card and Marc will talk for a while about the person or game in question. In this way, the cards provided some focus for the discussion rather than relying solely on audience questions. Another benefit is that light was often shed on individuals or games that might otherwise not get discussed, like Chaco, a wargame about the 1932–1936 war between Bolivia and Paraguay. The game is one of Miller's earliest designs and was created, in part, as an educational tool to teach about South American history.All the panels at Gamehole Con were too short – only an hour. They were all held in the same room, with a new one starting every hour on the hour, all day, every day. That meant that there was often a rush toward the end of each panel that caused a fair bit of disruption, as overzealous gamers tried to enter an ongoing panel before it was actually ended. I would have much preferred fewer, longer panels, so that we could luxuriate a bit in the stories and memories of the guests. In the case of Marc Miller, he has so many stories. He's now 77 years old and has been involved in the hobbies of wargaming and roleplaying for more than half a century. Yet, his memory is incredibly sharp and, with age, I think he's acquired a perspective that's refreshing in its humility. He talked a lot about how, as in the case of TSR, no one really knew what they were doing at GDW. They were making it all up as they went, having fun as they explored new ideas and took chances on making them reality. Some ideas were better than others and some approaches worked, but they learned a lot from each project, whether it proved a success or a failure. Marc expressed several times how blessed he'd been to have had the career he had, making games and making people happy.

Not a bad legacy, eh?

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers