James Maliszewski's Blog, page 35

December 16, 2024

A Random Demon

Being a big fan of the humorous illustrations of Wil McLean, I thought I'd share this fun little comic from issue #20 of Dragon (November 1978).

Starting with Classic Traveller

Toward the end of last month, I mentioned that Mongoose Publishing, the new owners of Traveller, had released a few 72-page Starter Pack for the game in PDF form. It's a good introduction to the current version of Traveller, giving newcomers a taste of both the rules and the kinds of adventure scenarios with which they can be used.

Toward the end of last month, I mentioned that Mongoose Publishing, the new owners of Traveller, had released a few 72-page Starter Pack for the game in PDF form. It's a good introduction to the current version of Traveller, giving newcomers a taste of both the rules and the kinds of adventure scenarios with which they can be used.

However, not everyone's interested in Mongoose's edition of Traveller. Many people would prefer their introduction to the venerable science fiction roleplaying game be through the "classic" version published by Games Designers' Workshop between 1977 and 1986. In fact, since I got back from Gamehole Con, I've received several emails from people asking me my opinion about the best introduction to Traveller, specifically which edition of the rules and what supplements and adventures I'd recommend. Since this is a common question I'm asked, I thought it might be useful to write a post devoted to this topic.

My standard response to this question is to direct people toward The Traveller Book, which I've previously called the perfect RPG book. I stand by that assessment for all the reasons I mentioned in my original post, but one of the biggest is that it's still in print and available for only $20 from DriveThruRPG. For a 160-page hardcover book, that's an incredible bargain, all the more so, because it includes everything you'd ever need to play Traveller under one cover – rules, encounters, patrons, adventures, and an overview of the Third Imperium and the Spinward Marches sector. Truly, this is still probably the best way to familiarize yourself with Traveller.

That said, there are another couple of options worth considering. The first is Starter Traveller, originally released as a boxed set in 1983. This version of the game includes the same rules as The Traveller Book, but formatted as a 64-page book, The reason it's shorter is that all of the relevant charts relating to gameplay have been removed and placed in their own separate 24-page book. Also included with the set are two adventures, Mission on Mithril and Shadows, both of which had been previously released.

Another possibility is the Classic Traveller Facsimile Edition, which presents the three little black books of classic Traveller as a single digest-size 160-page book. Like The Traveller Book, the Facsimile Edition is available in print from DriveThruRPG and it's even less expensive – $9! This version has the advantage of preserving the original layout of the 1981 edition, while the other two options have been updated and improved in various ways. This is the edition you'll want to buy if your interest in primarily in getting a sense of what the game like in its early days. (To clarify: this is not the original 1977 version, though it's very close).

Each of the three options above has its advantages and disadvantages, depending on what you're looking for. Overall, I continue to favor The Traveller Book as the best all-around intro to the classic game, but I have an affection for Starter Traveller, because it was the first edition I owned. And, as I've already said, the Facsimile Edition is best for those hoping to get a sense of what the game was like in its earliest stages, before the Third Imperium setting had begun to take over the line and become not merely an example of a setting but the setting for the game.

On the question of what to buy after obtaining the rules, I'd recommend avoiding any of the volumes with "Book" in the title, like Book 4: Mercenary or Book 5: High Guard – not because they're bad supplements but because they're very specific and unnecessary to all but the most dedicated players. Newcomers have no need of them. Instead, I'd recommend focusing on adventures, especially those I've included on my Top 10 lists of the same. All of them are still available in PDF form through DriveThruRPG and are good options if you want to get a sense of what classic Traveller is all about.

As I've noted several now in recent weeks, I'll be talking a lot more about Traveller here, since it's a game and a topic about which I remain quite passionate and about which I feel I still have interesting things to say – unlike Dungeons & Dragons, but that's a topic for an upcoming post ...

December 13, 2024

Questions and Answers

With the end of my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign in sight after nearly a decade of regular play, I've started thinking about not just its conclusion but what happens after the conclusion. Since nearly all of the players have agreed they'd like me to referee a new game, it's clear that our little circle of gamers will continue to meet each week after the final curtain falls on this particular campaign. And while the question of precisely what game we'll play next is an interesting one – I may post about that later – what I want to talk about now is something quite different.

House of Worms began in early March 2015. When I started it, I simply wanted to give Empire of the Petal Throne another whirl. I'd refereed the game a couple of time prior, but neither of those campaigns lasted very long. Considering how rich and compelling the world of Tékumel is, I felt I owed it to myself to give EPT another shot. I was quite fortunate that, this time, in the words of Col. John "Hannibal" Smith, it all came together and remarkably so. We're now just shy of the ten-year mark, which makes House of Worms the single longest continuous RPG campaign I've ever refereed by a wide margin.

At the start, though, I had no idea how long the campaign would last. Based on my past experiences with Tékumel, I had no expectation that House of Worms would last even a single year, let alone ten. As a result, I didn't plan too far ahead. I had some basic ideas of how to kick off the campaign and where it might go after that, but most of my ideas were pretty sketchy and that's being generous. I relied pretty heavily on player decisions to guide where the campaign went and what I developed for it. I tried to stay a few steps ahead of the players at all times, but, even then, I regularly created and discarded ideas at a fairly quick pace, responding in equal parts to what the players did and my own changing interests.

In my campaigns, I try to give the impression that the end results are what I'd had in mind all along. Of course, it's a parlor trick, misdirection in which I get the players to focus on what worked rather than what didn't. In the past, I've described my campaigns as being a lot like that scene in the movie Ghostbusters, where Bill Murray's Peter Venkman attempts to pull the tablecloth out from under the place settings on a table in the dining room. He fails utterly but is undeterred, boasting, "And the flowers are still standing!" even as everything else falls to the floor. That's what I do much of the time.

Despite that, I still do have ideas I purposefully introduce into the campaign and that prove important. It's not entirely an illusion. Some of these ideas bear fruit and some do not, while others morph into something I'd not originally intended. I imagine that's not a phenomenon unique to me. Any long running campaign is likely to include plenty examples of all of the above. In fact, I have a hard time imagining how a roleplaying campaign could go for more than a few weeks before it starts to diverge from what any of its participants consciously had in mind. That's one of the main joys of this form of entertainment: you never know where's going to wind up.

So, when House of Worms finally does end, I'm going to devote the next session to a wrap-up in which I'll encourage the players to ask my anything about the campaign and how it developed. What ideas did I originally have and how did they change? What was going on with some character or plot that was left dangling at the end? How much did their choices to zig when I expected them to zag derail what I might have had in mind? And so on. I greatly value transparency in most things, including RPGs. Letting the players see "behind the curtain," so to speak, is important, especially in a campaign as long-running as House of Worms.

Needless to say, I'll do a post or two about the players' questions and my answers to them. I feel the process of refereeing is often too opaque and writing about what I did and why over the course of the last decade will undoubtedly be useful to other referees (and probably players as well). The end of House of Worms is a major event for all involved. Expect to see quite a few posts devoted to it in the weeks and months to come.

December 10, 2024

Retrospective: Duneraiders

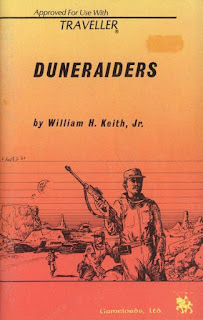

My look at classic Traveller adventures and supplements continues this week with 1984's Duneraiders, a scenario I ranked as number 8 on my list of the top 10 scenarios published for the game. Like last week's Nomads of the World-Ocean, Duneraiders was written and illustrated by the Keith Brothers (with William H. Keith credited as its primary creator) for Gamelords. That's not the only similarity between the two adventures, as I'll soon explain.

My look at classic Traveller adventures and supplements continues this week with 1984's Duneraiders, a scenario I ranked as number 8 on my list of the top 10 scenarios published for the game. Like last week's Nomads of the World-Ocean, Duneraiders was written and illustrated by the Keith Brothers (with William H. Keith credited as its primary creator) for Gamelords. That's not the only similarity between the two adventures, as I'll soon explain.

Before getting to that, I'd like to take a moment to talk briefly about Gamelords and its place in the history of both roleplaying and the hobby. Headquartered in Gaithersburg, Maryland (a suburb of Washington, DC), the company is probably best known today for Thieves' Guild fantasy products. For me, though, it was their many excellent Traveller releases that most captured my attention.

Along with pre-Battletech, pre-Shadowrun FASA, Gamelords was a GDW-approved licensee, given a region of the Third Imperium setting to develop through their scenarios. This region included the Reavers' Deep sector, a frontier bounded by the Imperium, the Aslan Hierate, and the Solomani Confederation. The Deep features mostly independent worlds, some of them joined together into about a half-dozen small interstellar states that contend with one another and the aforementioned larger powers. It's a great setting for Traveller campaign, especially the particular style of Traveller campaign in which the player characters work primarily as mercenaries and agents provocateur.

In the case of Duneraiders, the characters find themselves on the backwater world of Tashrakaar, a desert planet in the Drexilthar subsector. While hanging out at its primitive, class-D starport, they witness a firefight on the loading dock. Duneraiders – human inhabitants of the open desert – are attacking a massive orecrawler with the obvious intention of destroying or at least severely damaging it. This is noted by bystanders as unusual behavior. Though the Duneraiders have no love for the mining companies that extract minerals from "the Flats" region of Tashrakaar for sale offworld, nearly all of their attacks are against the companies' operations, not permanent settlements.

The adventure assumes the characters will inevitably intervene against the Duneraiders. In doing so, they also rescue a young woman, Arlana Jeric, whose father, Gill, is the owner and operator of Jericorp Mining, a small resource extraction business. It doesn't take long to realize that the "Duneraiders" are, in fact, goons in the employ of Jericorp's bigger and better capitalized rival, Dakaar Minerals, who are attempting to mask their involvement by disguising themselves as the desert dwellers. Unfortunately, the goons are successful in damaging the orecrawler, which was one of several owned by Jericorp. Without it operating, Jericorp may be unable to prove its claim on a stretch of the Flats believed to hold a motherlode of minerals.

That's when Arlana suggests that perhaps the characters would be willing to hire on as freelance troubleshooters for Jericorp, providing security for another orecrawler as its crew desperately attempts to locate the rich veins of ore they suspect are there. If the characters agree, this is where the adventure proper truly begins. The bulk of Duneraiders' 60 pages are devoted to describing the Orecrawler (with deckplans) and its 12-man crew, Tashrakaar and its ecology, and, of course, the titular Duneraiders and their culture. It's a very impressive package, providing the referee with everything he needs to run many sessions on this single planet of the Reavers' Deep sector.

If this sounds familiar, it is, because, in broad outlines, Duneraiders is another example of a very common classic Traveller scenario: the characters involve themselves in coprorate shenanigans on a backwater planet whose environment and native inhabitants are equal parts challenges and assets – just as we saw in Nomads of the World-Ocean. There's nothing wrong with this; it's a very fun set-up for an extended adventure. Furthermore, the Keith Brothers are very imaginative and each of the worlds presented in their work is genuinely unique. However, I suspect that a Traveller referee would be wise to avoid using too many of these scenarios in his campaign, lest they seem overdone.

Duneraiders is a very good adventure about which I have fond memories playing rather than refereeing. That partly explains why I think so highly of it. The other is that there's something inherently compelling about the characters fighting against an exploitative corporation, aided by locals who better understand the hostile environment in which the battle must be fought. Unsurprisingly, Frank Herbert's Dune series was probably a major inspiration for this adventure, but I also expect the 1962 film Lawrence of Arabia also influenced the Keiths in imagining Tashrakaar and its inhabitants. Though not quite as good as Nomads of the World-Ocean, Duneraiders is a fine example of classic Traveller adventure design and well worth a look.

Oldies but Goodies!

One of the most vexing aspects of middle age is looking back on the past with hindsight and thinking, "If only I knew then what I know now." That's precisely the thought that entered my head when I saw this advertisement from the Armory in issue #69 (January 1983).

Marvel at how inexpensive all these early TSR products were! Had I but known and been interested in this stuff, I could have really cleaned up, since the prices, even adjusted for inflation, are all quite reasonable, especially for the OD&D supplements. Now, as it turns out, I would eventually acquire a complete set of everything produced for OD&D for similarly low prices at the end of the '80s, so I can't complain too much. Still, ads like this make me wish I had access to a time machine.

Marvel at how inexpensive all these early TSR products were! Had I but known and been interested in this stuff, I could have really cleaned up, since the prices, even adjusted for inflation, are all quite reasonable, especially for the OD&D supplements. Now, as it turns out, I would eventually acquire a complete set of everything produced for OD&D for similarly low prices at the end of the '80s, so I can't complain too much. Still, ads like this make me wish I had access to a time machine.

December 9, 2024

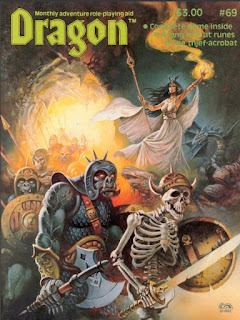

The Articles of Dragon: "A Split Class for Nimble Characters: the Thief-Acrobat"

Issue #69 of Dragon (January 1983) is another one about whose articles I have very strong memories. The strength of my memories is bolstered, no doubt, by the issue's remarkable cover by Clyde Caldwell. Caldwell's an artist about whom my feelings are generally mixed, but I've nevertheless got a fondness for this particular piece, which, in some ways, encapsulates the vibe of the dying days of D&D's Golden Age. Consequently, I'll be returning to this issue several times in the coming weeks.

Issue #69 of Dragon (January 1983) is another one about whose articles I have very strong memories. The strength of my memories is bolstered, no doubt, by the issue's remarkable cover by Clyde Caldwell. Caldwell's an artist about whom my feelings are generally mixed, but I've nevertheless got a fondness for this particular piece, which, in some ways, encapsulates the vibe of the dying days of D&D's Golden Age. Consequently, I'll be returning to this issue several times in the coming weeks.

This week, though, I want to look at Gary Gygax's "From the Sorceror's [sic] Scroll" column, in which he provides full details on the thief-acrobat "split class" that he first mentioned in a previous column. A split class is a specialization path for an existing class, in this case the thief. Provided he has the appropriate ability scores requirements (STR 15, DEX 16), a thief can, upon attaining 6th level, choose to devote himself to acrobatics as an outgrowth of his thievery – in effect, becoming a cat burglar or second story man in criminal parlance.

At the time of this article's publication, this was a comparatively unique concept, one that Gygax claims "has not been expressed before" and for which there is "nothing similar" in AD&D. I'm not entirely sure this is true. As I mentioned previously, the thief-acrobat reminds me a bit of the original concept for the paladin class, as found in Supplement I to OD&D. Likewise, the AD&D version of the bard, in which a character must first attain levels in fighter and thief before becoming a bard, is in the same ballpark in my opinion. Even so, the precise arrangement Gygax presents for the thief-acrobat isn't one we'd seen before.

I liked the idea of the thief-acrobat more in principle than in fact and my friends held similar views. Only one of them ever chose to pursue this split class and the player soon grew bored of playing him. That was probably the biggest problem with the thief-acrobat: it was very specialized and thus of limited utility. This is the kind of class that I could see thriving in, say, an urban, all thief campaign, where each character needs to distinguish himself from his fellow thieves. In a more traditional dungeon-based campaign, I think the thief-acrobat hold much less or appeal – or at least that's how my friends and I viewed it.

When it comes to the question of designing character classes, there are a couple of common approaches, neither of which is without its problems. Dungeons & Dragons began with only a few broad, archetypal classes, like the cleric, fighting man, and magic-user, but soon added many more, each one devoted to a narrower but nevertheless real archetype. AD&D opted for a larger list of available classes, while the D&D line kept to something closer to the original, narrower list. Each approach has its advantages and disadvantages and I can easily defend them both.

Had Gygax remained at the helm of AD&D, we would certainly have seen more classes added to its roster, some of which, like the thief-acrobat, would have been quite narrow in their utility. That's not necessarily a problem, but it can add a lot of unnecessary complexity to the game, not to mention diluting the game's flavor. On the other hand, a goodly selection of classes can, if presented properly, increase the game's flavor, with each one revealing more about its explicit or implied setting and the sorts of activities characters are expected to undertake within it.

Whether the thief-acrobat succeeds in doing any of these things is an open question, hence my own ambivalence toward it. Even so, this article sticks in my mind, because, like others written by Gygax at the time, it offered a sneak peek into his evolving vision of AD&D. It was a really interesting time to be a fan of the game and I'm glad to have been around for it.

What the @!¢%*# is GURPS?

Though I was a fan of Ogre and Car Wars, both designed by the American Steve Jackson (not the British one), I didn't pay close attention to the other games his company was publishing. Consequently, when GURPS arrived on the scene in 1986, I largely paid it no heed, aside from the very peculiar advertisements I remember seeing in the pages of Dragon and elsewhere, like this one.

What's most immediately striking to me about this ad – aside from the painful lack of a question mark – is that nowhere does it explain what GURPS actually stands for. That's probably intentional, since the oddity of the game's title is memorable and might serve to pique interest in it. By the time I first played GURPS in the early '90s, it was already common knowledge that this was the Generic Universal Role Playing System, so it never really bothered me. But to a contemporary reader of Dragon? I wonder what he'd have thought.

What's most immediately striking to me about this ad – aside from the painful lack of a question mark – is that nowhere does it explain what GURPS actually stands for. That's probably intentional, since the oddity of the game's title is memorable and might serve to pique interest in it. By the time I first played GURPS in the early '90s, it was already common knowledge that this was the Generic Universal Role Playing System, so it never really bothered me. But to a contemporary reader of Dragon? I wonder what he'd have thought.

Fantasy Lives!

I've written about Powers & Perils before, so I won't repeat myself here. I will, however, share this advertisement for it that I remember seeing in several gaming magazines in the mid-80s.

December 8, 2024

Going Home

I've now been refereeing my Barrett's Raiders Twilight: 2000 campaign for three years in real-world time, covering considerably less time within the game world – only about two and a half months. During that time, the character's unit, consisting primarily of American personnel trapped behind Warsaw Pact lines after the disastrous Battle of Kalisz, has attempted to find its way back to NATO-controlled territory. In the course of doing so, they've visited the Free City of Kraków, traveled partway down the Vistula by boat, tangled with marauders, the GRU, and rogue elements of the Red Army, not to mention Polish nationalist groups seeking to rebuild their country independent of both sides in the Cold-War-turned-hot. Consequently, the characters' journey hasn't always followed a straight line.

I've now been refereeing my Barrett's Raiders Twilight: 2000 campaign for three years in real-world time, covering considerably less time within the game world – only about two and a half months. During that time, the character's unit, consisting primarily of American personnel trapped behind Warsaw Pact lines after the disastrous Battle of Kalisz, has attempted to find its way back to NATO-controlled territory. In the course of doing so, they've visited the Free City of Kraków, traveled partway down the Vistula by boat, tangled with marauders, the GRU, and rogue elements of the Red Army, not to mention Polish nationalist groups seeking to rebuild their country independent of both sides in the Cold-War-turned-hot. Consequently, the characters' journey hasn't always followed a straight line.Recently, though, their travels took on an added level of urgency, thanks to their picking up a radio message announcing Operations Order OMEGA. This order, issued under the extraordinary authority of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, heralded the evacuation of all US personnel in Europe, civilian and military. The schedule of the withdrawal provides for the departure on November 15, 2000 of as many US personnel as possible from Bremerhaven, West Germany to Norfolk, Virginia, USA. Since departure is largely on a "first come, first served" basis, the characters have decided that they must make it to Bremerhaven well before November, since they have no desire to remain in Europe.

The last few weeks of the campaign have been devoted to the characters' determined efforts to head westward into Germany. This has proven difficult, as what remains of organized Warsaw Pact forces are still operating in that area and, needless to say, are vastly more powerful than themselves. Marauders of all kinds are another obstacle with which they must contend. To date, their efforts have been slow and careful, with the goal of avoiding contact with any enemy forces they can – as well as any remaining NATO forces that hope to enmesh them the final, failing stages of their own operations in Eastern Europe. In short, they simply want to go home.

While it'll likely still be many more weeks of play before they succeed in reaching secure NATO lines and make their way safely to Bremerhaven (assuming they do so, of course), I've nevertheless started thinking about what the characters will find once they cross the Atlantic and return to the USA. In the earlier GDW canon of the game, America is in chaos, with authority – where it exists at all – is divided between Joint Chiefs of Staff, who assumed control after the president, vice president, the cabinet, and a large portion of the Congress were killed, and a civilian government reconstituted under unusual and possibly illegal means. The conflict between "MilGov" and "CivGov," as they are colloquially known, plays a major role in the post-war history of the country.

In general, I like this conflict. I think it works well in a game in which the characters are active duty military personnel, who would be torn between their loyalty to the Army and their oaths to the Constitution. Unfortunately, I don't think the way GDW sketched out the conflict was very good, nor do I think they considered its impact on Twilight: 2000 campaigns set in America. So, I've been trying to give these matters a great deal more thought, with a goal of creating something that's both plausible and playable. In particular, I want to present a situation that's a genuine muddle without obvious good guys or bad guys, where the characters will have sort out the question of whom to support and why for themselves.

I'm actually looking forward to this next phase of the campaign a great deal. While in Poland, the characters never settled down for any length of time. Every time a situation arose that threatened to tie them down, they did the best they could to extricate themselves. As their commanding officer, Lt. Col. J.D. Orlowski, regularly reminds them, "We're US soldiers first and foremost." There was never much chance they'd abandon their duties to the Army, so it was only ever a question of when not if they'd make their way homeward. Now that they are, I can start thinking about the bigger picture and how the characters might make a lasting difference in the post-nuclear world. I'm quite excited by the prospect.

December 4, 2024

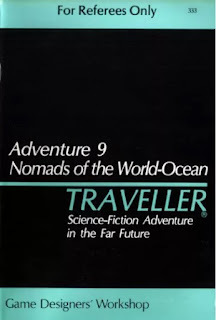

Retrospective: Nomads of the World-Ocean

I recently mentioned that I'd be devoting more space on this blog to coverage of Traveller. I thought a good way to start making good on that pledge is using my weekly Retrospective to draw attention to some of my favorite Traveller products, since Game Designers' Workshop published a large number of excellent adventures and supplements for the game. They're not all winners, of course, but I do think that Traveller had a higher ratio of good to bad support material than many of its contemporary RPGs.

I recently mentioned that I'd be devoting more space on this blog to coverage of Traveller. I thought a good way to start making good on that pledge is using my weekly Retrospective to draw attention to some of my favorite Traveller products, since Game Designers' Workshop published a large number of excellent adventures and supplements for the game. They're not all winners, of course, but I do think that Traveller had a higher ratio of good to bad support material than many of its contemporary RPGs.A good example of what I'm talking about is 1983's Nomads of the World Ocean, written and illustrated by the incomparable Keith Brothers. I'd previously mentioned this adventure, the ninth published for Traveller, in my list of the Top 10 Classic Traveller Adventures, where it ranked as number 4. I still think that's a fair judgment, because, while very well-done, Nomads of the World-Ocean is also a very specific kind of scenario and, therefore, might not hold a wide appeal.

The adventure takes place on Bellerophon, a world in the Solomani Rim subsector. As its title suggests, Bellerophon is a water world whose only dry land are a few scattered islands and reef-flats exposed at low tide. Despite this, the planet boats a population of over 2 billion humans, most of whom live on magnificent pylon cities that rise from the ocean shallows, thrusting two or three kilometers into the sky. There are also sea-bottom complexes and free-floating raft cities, as well as a considerable population of the titular nomads, who live aboard large ship-cities that follow herds of marine creatures called daghadasi that provide them with a livelihood.

Like many classic Traveller adventures, the characters come to Bellerophon as agents of an outside organization, sent to investigate the activities of a corporation that operates on the planet. In this case, the corporation, Seaharvester, is culling the population of daghadasi in order to obtain a chemical produced by the animals in their pre-reproductive phase. This chemical has proven to be the basis for an entirely new family of drugs that have the potential to wipe out bacteria, viruses, viroids, and even cancer cells. Unfortunately, a daghadasi carcass weighing a million tons yields only a few grams of the chemical. Worse, only about 10% of all slaughtered daghadasi produce more than trace amounts of it, necessitating massive, indiscriminate slaughter to procure this valuable new chemical.

When evidence of Seaharvester's actions became known, public opinion turned against them and its parent company, SuSAG, one of the Imperium's megacorporations, placed limits on their culling of the daghadasi. However, there's evidence that Seaharvester has been skirting these limits and it's now up to the characters to prove it. The adventure presents two options to involve the characters. One assumes they're working for an environmentalist group, the Pan-Galactic Friends of Life, while the other assumes they're employed by SuSAG itself, looking to save its reputation.

What makes Nomads of the World-Ocean special isn't this set-up but the world of Bellerophon itself. Everything about it is described in loving detail, with plenty of hooks for interesting encounters, side adventures, and exploration. The Keith Brothers give us information on the pylon cities, Seaharvester's factory ships, the lifecycle and ecology of the daghadasi and, of course, the nomads themselves. As one might expect, the nomads receive the greatest amount of detail, since they hold the key to proving the continued malfeasance of Seaharvester.

The nomads live on wandering ship-cities of 1000-5000 people. Their society and indeed livelihoods depend on the kilometers-long daghadasi, whom they sustainably hunt to provide not just food but also materials for the manufacture of other items that they trade. The nomads are a highly technological society. Their ship-cities, for example, make use of fusion power, as do the various smaller craft they use in the hunting of the daghadasi. Though they share a common language and culture, the nomads are divided into factions, based in part on their attitudes toward outsiders and the traditional ways of their people, which is now under threat from Seaharvester. A significant portion of the scenario involves the characters having to navigate nomad politics to achieve their own ends.

Nomads of the World-Ocean is a great example of something classic Traveller did very well: present a single world out of the 11,000 that make up the Third Imperium and showing that it alone is more than sufficient to occupy the characters' attention for weeks or even months of gameplay. One of the paradoxes at the heart of Traveller is that, as its name suggests, the characters are assumed to move around a lot from world to world and even sector to sector, never staying in one place for very long. Yet, each and every world they visit is – or can be – a setting in itself. Balancing the characters' ability to travel easily across Charted Space with giving each world its own unique appeal isn't always easy, which is why I so highly regard adventures like this one. Nomads of the World-Ocean is a terrific example of Traveller at its best.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers