James Maliszewski's Blog, page 34

December 22, 2024

D&D and Traveller

I think we tend to underestimate just how old Traveller is.

I think we tend to underestimate just how old Traveller is. Consider that original Dungeons & Dragons, the very first roleplaying game ever published, was released sometime in late January 1974. Traveller first appeared less than three and a half years later, in late May 1977 (before the wide release of Star Wars, which is a very important fact to bear in mind). Less than a dozen other RPGs were published between these two dates and, of those that were, almost none of them are still published today. That alone sets Traveller apart from its contemporaries.

I mention this because, as I was thumbing through my 1977 Traveller boxed set, I was struck by just how similar in format and content the game is to the 1974 OD&D boxed set. This is not an original thought and indeed it's one that I've had before. I nevertheless think it's worthy of further examination. We are, after all, closing out D&D's semicentennial year and, while I'm reducing the attention I'll devote to that game for the foreseeable future, there really is no escaping its gravitational pull. Like it or not, discussions of almost any roleplaying game will inevitably lead back to Dungeons & Dragons. In the case of Traveller, the most immediately obvious connection to D&D is its format. Like OD&D, Traveller was initially released in a boxed set containing three digest-sized booklets. Each of these booklets focuses on a different aspect of the overall game rules. OD&D's first volume is entitled "Men & Magic" and provides the rules for character generation, combat, and spells. Traveller's first volume is called "Characters and Combat" and covers very similar ground. The second volume of OD&D is "Monsters & Treasure," while that of Traveller is "Starships." The difference between these two volumes is stark, since there's not much commonality of subject matter here and not merely because OD&D has no need of rules for space travel. However, the obvious connections between the two games return with the third volume of each. OD&D has "Underworld & Wilderness Adventures" and Traveller has "Worlds and Adventures."

In the case of Traveller, the most immediately obvious connection to D&D is its format. Like OD&D, Traveller was initially released in a boxed set containing three digest-sized booklets. Each of these booklets focuses on a different aspect of the overall game rules. OD&D's first volume is entitled "Men & Magic" and provides the rules for character generation, combat, and spells. Traveller's first volume is called "Characters and Combat" and covers very similar ground. The second volume of OD&D is "Monsters & Treasure," while that of Traveller is "Starships." The difference between these two volumes is stark, since there's not much commonality of subject matter here and not merely because OD&D has no need of rules for space travel. However, the obvious connections between the two games return with the third volume of each. OD&D has "Underworld & Wilderness Adventures" and Traveller has "Worlds and Adventures."  As I said, there's nothing novel about these observations. They've been made for years on OSR blogs and forums and were probably noted at the dawn of the hobby, too. I would not be at all surprised if Marc Miller and/or other notables at Games Designers' Workshop made them as well. When I attended Gamehole Con in October, one of the many amusing stories Marc Miller told about the early days of GDW concerned the release of Dungeons & Dragons. He said that the company's staff was so taken with the game that they soon spent all their time playing it. So enamored were they with this weird new game that Frank Chadwick, GDW's president at the time, established a rule: "No playing D&D during office hours."

As I said, there's nothing novel about these observations. They've been made for years on OSR blogs and forums and were probably noted at the dawn of the hobby, too. I would not be at all surprised if Marc Miller and/or other notables at Games Designers' Workshop made them as well. When I attended Gamehole Con in October, one of the many amusing stories Marc Miller told about the early days of GDW concerned the release of Dungeons & Dragons. He said that the company's staff was so taken with the game that they soon spent all their time playing it. So enamored were they with this weird new game that Frank Chadwick, GDW's president at the time, established a rule: "No playing D&D during office hours." It's a very funny story in its own right, as well as a reminder – as if we needed one – that the appearance of Dungeons & Dragons on the wargaming scene in 1974 forever changed the face of that hobby and, in the process, created an entirely new one. Though primarily a historical wargames publisher, GDW was no stranger to science fiction. Prior to the release of Traveller, the company had already published two science fiction games: Triplanetary in 1973 and Imperium in 1977. The latter game initially had no connection to Traveller, which, upon its release, included no setting whatsoever. It was only later that the background of Imperium. with its series of Interstellar Wars between the Vilani and the Terrans, was folded into the much more successful Traveller.

It's a very funny story in its own right, as well as a reminder – as if we needed one – that the appearance of Dungeons & Dragons on the wargaming scene in 1974 forever changed the face of that hobby and, in the process, created an entirely new one. Though primarily a historical wargames publisher, GDW was no stranger to science fiction. Prior to the release of Traveller, the company had already published two science fiction games: Triplanetary in 1973 and Imperium in 1977. The latter game initially had no connection to Traveller, which, upon its release, included no setting whatsoever. It was only later that the background of Imperium. with its series of Interstellar Wars between the Vilani and the Terrans, was folded into the much more successful Traveller.

OD&D was thus a significant inspiration for Marc Miller in creating Traveller, since it showed him not just what was possible with a roleplaying game but also the form such a game might take. Admittedly, this is likely true of nearly every RPG published in the last half-century, but, in the case of Traveller, it's especially so, since, by his own admission, he and the other designers at GDW were playing a lot of D&D in those days. Miller even contributed some D&D comics to The Strategic Review, which testifies to his early devotion to the game. When I spoke to him in October, he repeatedly emphasized the debt we all owe Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson for having created a form of entertainment unlike any that came before. Miller even included Gygax in his deck of cards as a "king" of GDW, since the company published his Dangerous Journeys game in the '90s.

OD&D was thus a significant inspiration for Marc Miller in creating Traveller, since it showed him not just what was possible with a roleplaying game but also the form such a game might take. Admittedly, this is likely true of nearly every RPG published in the last half-century, but, in the case of Traveller, it's especially so, since, by his own admission, he and the other designers at GDW were playing a lot of D&D in those days. Miller even contributed some D&D comics to The Strategic Review, which testifies to his early devotion to the game. When I spoke to him in October, he repeatedly emphasized the debt we all owe Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson for having created a form of entertainment unlike any that came before. Miller even included Gygax in his deck of cards as a "king" of GDW, since the company published his Dangerous Journeys game in the '90s. The connections between D&D and Traveller were not apparent to me in my youth, in large part because I didn't come across a copy of OD&D '74 until I was in high school, by which point Traveller was already well on its way toward becoming

MegaTraveller

– a much more mechanically complex game published, like AD&D, in a conventional 8½ × 11" format. Now that I am aware of the myriad connections, they're impossible to un-see. To be honest, I'm glad of that. As I have no doubt written here dozens of times, Dungeons & Dragons was my first love, but Traveller is my true love. They're both very special to me and, while there's no question which one is my favorite, I would prefer not to have to choose between them. For the moment, though, Traveller has my attention. I very much look forward to sharing my thoughts and memories of this great roleplaying game.

The connections between D&D and Traveller were not apparent to me in my youth, in large part because I didn't come across a copy of OD&D '74 until I was in high school, by which point Traveller was already well on its way toward becoming

MegaTraveller

– a much more mechanically complex game published, like AD&D, in a conventional 8½ × 11" format. Now that I am aware of the myriad connections, they're impossible to un-see. To be honest, I'm glad of that. As I have no doubt written here dozens of times, Dungeons & Dragons was my first love, but Traveller is my true love. They're both very special to me and, while there's no question which one is my favorite, I would prefer not to have to choose between them. For the moment, though, Traveller has my attention. I very much look forward to sharing my thoughts and memories of this great roleplaying game.December 21, 2024

Three Dimensions

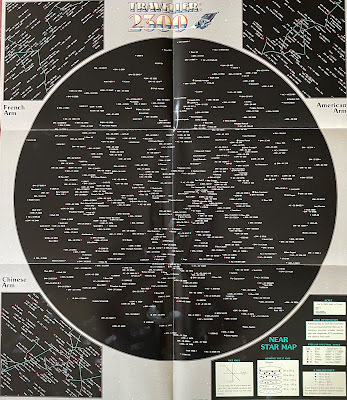

I mentioned in yesterday's post about my favorite science fiction roleplaying game map that Traveller's star maps are two-dimensional and that that's long been an issue for some fans of the game (though it mostly doesn't bother me). In the comments to that post, several readers mentioned the three-dimensional star maps included in GDW's 2300AD (né Traveller: 2300) and SPI's Universe. Here's the Near Star Map from the former, which covers a volume of space within 50 light years of our solar system:

Even at this small size, you can see there are a lot of stars included on this map. As it turns out, there are, in reality, even more stars within 50 light years of Sol, but GDW didn't have the benefit of our current astronomical knowledge. They worked from the then-quite good Gliese Catalogue of Nearby Stars from the '70s, which has since been updated many times (and perhaps even superseded). Still, I loved this map, which included XYZ coordinates for hundreds of stars, which provided lots of scope for exploration and adventure in the 24th century.

Even at this small size, you can see there are a lot of stars included on this map. As it turns out, there are, in reality, even more stars within 50 light years of Sol, but GDW didn't have the benefit of our current astronomical knowledge. They worked from the then-quite good Gliese Catalogue of Nearby Stars from the '70s, which has since been updated many times (and perhaps even superseded). Still, I loved this map, which included XYZ coordinates for hundreds of stars, which provided lots of scope for exploration and adventure in the 24th century.Much as I loved that map, though, my absolute favorite 3D star map came from SPI's Universe:

This map included far fewer star systems and covered only a volume of about 30 light years from Earth. However, I probably spent far more time poring over this map than 2300AD's. The reason for this is quite simple: I encountered the Universe map first, making it perhaps the first three-dimensional star map I'd ever seen. Unlike 2300AD, I never actually played Universe, but I read the one-volume, softcover edition of the game released by Bantam Books cover to cover multiple times. The pull-out star map left a lasting impression on my thirteen-year-old self.

This map included far fewer star systems and covered only a volume of about 30 light years from Earth. However, I probably spent far more time poring over this map than 2300AD's. The reason for this is quite simple: I encountered the Universe map first, making it perhaps the first three-dimensional star map I'd ever seen. Unlike 2300AD, I never actually played Universe, but I read the one-volume, softcover edition of the game released by Bantam Books cover to cover multiple times. The pull-out star map left a lasting impression on my thirteen-year-old self.I love the idea of using a properly three-dimensional star map in a science fiction roleplaying game. Nowadays, the availability of much better astronomical data and personal computers with useful software, employing 3D maps is probably easier than it's ever been. Despite that, I've never refereed or played in a long-running SF RPG campaign that made use of them. I don't know why that is or if it's likely to change anytime soon. I have very vague ideas of following up my ongoing Twilight: 2000 campaign with a 2300AD one, but that's still some years in the future, if ever.

Has anyone reading this made a good use of three-dimensional star maps in their roleplaying games?

December 20, 2024

Ode to a Classic

One of the things I miss about the early days of the Old School Renaissance is how many blogs there were and how interconnected they all were. There was a lot of discussion back and forth between this blog and that one. Someone would make an interesting – or controversial – post and the next thing you knew, there were lots more posts commenting on it. This created a really dynamic ecosystem of personalities and ideas that gave those early days a distinct vibe that I just don't feel anymore, but I'm old, so that might just be me.

Sadly, I don't read as many other blogs as I used to do in those heady days. Consequently, I often miss really excellent posts, like this one, which was pointed out to me by Geoffrey McKinney, a longtime reader of this blog, as well as an accomplished old school game writer. The post, over at the A Knight at the Opera blog, talks at length about "the best RPG cover of all time," namely that of the 1977 Traveller boxed set. It's an excellent post with which I completely agree and I'm grateful to Geoffrey for pointing out to me.

Since I've been talking a lot about Traveller here lately, I thought it'd be worth sharing more widely. Head on over to A Knight at the Opera and give it a read. Be sure to leave a comment, too, if you like it. I'm sure the author would appreciate knowing that something he's written is being enjoyed. I know I always do.

The Best Map Ever (Take 2)

Long ago, at the dawn of this blog, I declared Darlene's exquisite map of The World of Greyhawk to be "the best map ever." To be fair, in the linked post, I qualified my hyperbole somewhat, saying that no "map for a fantasy RPG setting has ever captivated me the way" this one had – and I stand by that. Darlene's map of the Flanaess is one of the greatest maps ever made for use with a fantasy roleplaying game. It's beautiful simply as a work of art, eminently usable, and, for me at least, almost as iconic as Dave Trampier's AD&D Players Handbook cover.

However, there is another map of which I am equally fond. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it's this one:

I apologize for its small size. The original is quite large and the width of a blog post is inadequate to show its true glory. The map depicts the portion of Charted Space in which the Third Imperium and its interstellar neighbors exist, along with a couple of important astrographic features, like the Great and Lesser Rifts. Each of the rectangles represents a single sector, an area of space equal to 32 × 40 parsecs. Some of the sectors are named, like the Solomani Rim, the Beyond, and the Spinward Marches, but many of them are not.

I apologize for its small size. The original is quite large and the width of a blog post is inadequate to show its true glory. The map depicts the portion of Charted Space in which the Third Imperium and its interstellar neighbors exist, along with a couple of important astrographic features, like the Great and Lesser Rifts. Each of the rectangles represents a single sector, an area of space equal to 32 × 40 parsecs. Some of the sectors are named, like the Solomani Rim, the Beyond, and the Spinward Marches, but many of them are not. The map was, I believe, originally produced by GDW as a freebie to give away at conventions and to mail order recipients. I received mine in a large envelope after I'd written to the company to request their latest catalog. I was ecstatic to get it, because I'd previously seen a black and white reproduction of the map in a British book about RPGs whose title escapes me now (a No Prize to anyone who can tell me which one it was in the comments). I liked the map so much that I hung it on my bedroom wall, belong the Darlene Greyhawk map and there it stayed for years, even after I'd gone away to college. Unfortunately, the map was lost when I removed it from the wall some years later.

Unlike the Greyhawk map, this one is simple in its presentation and lacking in detail. Nevertheless, I'd still say it's quite beautiful. There's an elegance to it that I have always found incredibly appealing, an elegance that's very much of a piece with the elegance of Traveller itself. It uses only three colors – black, white, and red – just like the original Traveller boxed set, which I think contributes to rather than detracts from its attractiveness. In science fiction, minimalism is often a very solid esthetic choice and it's one that classic Traveller embraced from the very beginning (more on that particular topic in a future post).

The map's not without a couple of problems, the first of which being that it's a flat, two-dimensional depiction of three-dimensional space. That's an issue Traveller has always had and there's no easy way around it, though some fans have tried over the years. I've never been much bothered by it myself, since properly 3D star maps tend to be very complex and difficult to use in play. The bigger problem, in my opinion, is that most sectors of Charted Space are claimed by one or more large interstellar empires, which makes it feel fairly cramped rather than wide open. For many types of sci-fi campaigns, this is fine. If you're looking for one in which exploration is a central activity, it's less ideal, though there are some ways to fix this.

Even so, this remains one of my favorite RPG maps and one to which I regularly return for inspiration.

December 18, 2024

Solitaire

The third "configuration" of Traveller is solitaire and is described in this way:

One player undertakes some journey or adventure alone. He handles the effects of the rules himself. Solitaire is ideal for the player who is alone due to situation or geography.

I started playing Traveller in 1983, around the time that The Traveller Book was released – more than four decades ago now. In all the years I've played the game, I've never known anyone to play the game solitaire as described here. In fact, until the last few years, I don't think I recalled that solitaire was even mentioned as a possible way to play the game. That's not to say that Traveller isn't suitable for some degree of solitaire "play." The Traveller Book, in its section on "Basic Traveller Activities," notes that "many of the subordinate game systems lend themselves to solitaire ... play." This is absolutely true in my experience.

Traveller's character generation system is, in my opinion, one of the best ever devised, beautifully blending randomness with choice while also evoking the thrill of gambling. The system is so good that it's probably worthy of several posts about it, but, for now, what's important is that generating characters in Traveller is fun. You never quite know what you're going to wind up with, thanks to the unpredictability of the dice rolls. But no matter how things unfold, you (generally) wind up with a character who has a rough history of what he was doing between the age of 18 and when he enters the campaign after some period of time in service to one or another interstellar career, usually military.

Indeed, character generation is so fun that, to this day, I sometimes still generate a character or two as a way to pass the time. I used to have a nice little computer program that helped with this. It was called "TravGen" or something similar, but I lost it when I got a new computer and have never been able to find a functional version of it on the Internet since. Even without the program to speed things up, generating characters for Traveller is enjoyable as an activity in its own right – the kind of solitaire play I associate with the game.

Another form of solitaire play in which I still regularly engage is generating subsectors. This is a bit more involved than generating characters, but it's still a lot of fun. The last time I did this in earnest, I wound up creating an entire sector and starting up a non-Third Imperium Traveller campaign that I refereed for three years. That's the "danger" of generating subsectors: after a while, ideas about the various worlds you create, their inhabitants, and their relationships to one another start to percolate and the next thing you know, you're imagining an entire setting for a campaign. None of this is bad, of course – far from it! – but it is dangerous, in the sense that it can very easily feed gamer attention deficit disorder, something to which I was once very prone.

A third potential source of solitaire play within Traveller is trade and commerce. Choose a starship, pick a starting world in a subsector (whether published or one of your own creation), get some cargo and/or passengers, and then set off to try and turn a profit as you direct your ship from world to world. This is a great way to learn the speculative trade system in Traveller, as well as to better understand the economic ties that connect the worlds of one region of space. I have a vague recollection that GDW itself released a computer program in the 1980s that handled trade and commerce, but perhaps my aged brain imagined it. Regardless, trade is another fun way to play Traveller by oneself.

Compared to OD&D, which was released just three years prior, Traveller is a design of considerable elegance. All of its rules systems work well with one another and support and encourage its intended gameplay styles. Many of these systems, like the three I mentioned above, are enjoyable in themselves as separate "min-games" that can be "played" between sessions and that generate additional content for use in an ongoing campaign. It's absolutely brilliant design work and a big reason why I keep coming back to Traveller.

The Lord Weird Slough Feg

No discussion of Traveller is complete without mentioning the 2003 album of the same name by the heavy metal album band, The Lord Weird Slough Feg.

I'm no aficionado of metal (or indeed any other kind of popular music), but I own a copy of this and enjoy it. The album's especially fun for all the references to aspects of the Third Imperium setting.

If you visit the band's website, you'll see what looks like an announcement of their next music endeavor, to be released in 2025:

December 17, 2024

Retrospective: Leviathan

When I first shifted the focus of my Retrospective posts toward classic Traveller, I hadn't consciously decided to look at those adventures included in my Top 10 Classic Traveller Adventures about which I'd not previously written separate posts, but, after last week's post on

Duneraiders

, I realized that's exactly what I'd been doing. Rather than fight it, I've decided to lean into it, which is why I'm turning my gaze to Adventure 4: Leviathan, which I placed at the lofty rank of number 2 out of 10.

When I first shifted the focus of my Retrospective posts toward classic Traveller, I hadn't consciously decided to look at those adventures included in my Top 10 Classic Traveller Adventures about which I'd not previously written separate posts, but, after last week's post on

Duneraiders

, I realized that's exactly what I'd been doing. Rather than fight it, I've decided to lean into it, which is why I'm turning my gaze to Adventure 4: Leviathan, which I placed at the lofty rank of number 2 out of 10.Leviathan is a very unusual adventure for a number of reasons. First published in 1980, it was written by Bob McWilliams a name many of you might recognize from the pages of White Dwarf, where McWilliams had a regular column called "Starbase" devoted to Traveller. "Starbase" was a favorite – or should I say favourite? – feature of mine and one of the primary reasons I read White Dwarf in my youth. Unlike Dragon, where Traveller (and science fiction more generally) was mostly an afterthought until the advent of the Ares Section in April 1984, White Dwarf gave pride of place to Traveller, making it very appealing to a young sci-fi nerd like myself.

In many ways, Leviathan is as much a product of Games Workshop as it is of Game Designers' Workshop (GDW). In addition to McWilliams, the adventure credits Albie Fiore (another WD stalwart), Ian Livingstone (nuff said), and Andy Slack (ditto) as having edited it. Furthermore, the book includes illustrations by Fiore and the incomparable Russ Nicholson. Strengthening the overall Britishness of Leviathan is its use of UK spellings throughout the text, which is perhaps unintentionally appropriate, given the game's use of the double-l orthography for Traveller (whose origin, Marc Miller told me at Gamehole Con, lies with E.C. Tubb's Dumarest of Terra series).

Traveller's default playstyle could probably be described as a "hexcrawl in space," quite literally, given what the game's interstellar star charts look like. Leviathan takes this a step further, with the characters hired by the large multi-system trading cartel, Baraccai Technum, to participate in the exploration of a region of space known as the Outrim Void. The Void lies to rimward of the Spinward Marches sector and gets its name not from its emptiness but from its relative lack of civilization, at least compared to the Imperium. The terms of the characters' contract require them to sign on as crew for the exploratory merchant ship Leviathan on a voyage of about six months.

This is a very interesting and unusual set-up for a Traveller adventure, one that's been relatively rarely used in the game's history. One would think, given the history of popular science fiction, that interstellar exploration of an unknown area of space would be a fairly common subject for scenarios. That's generally not been the case with Traveller, at least not within the official Third Imperium setting. A big reason for that, as that setting evolved over the years, it's been extensively – even exhaustively – mapped, with literally thousands of worlds placed, named, provided with stats, and often more. That's been a blessing and a curse for referees over the decades and remains so today.

But, at the time Leviathan was written, that wasn't the case. The Third Imperium was then a very loose framework individual referees could shape to their own preferences and needs and the presentation of the Outrim Void demonstrates this. The worlds of the region are only briefly described and precisely what the characters will find as they explore them is largely left to the referee to fill in. Much like the Imperium itself, the Void is a loose framework for adventure, making it usable for all manner of encounters and scenarios. That's a big part of its appeal: it's a great tool for referees who want to do their own thing without having to invent an entire universe from whole cloth.

Interestingly, Leviathan spends almost half of its 44 pages to information on the titular 1800-ton Leviathan-class merchant cruiser. We get not only keyed deckplans, but also game stats for the ship and its entire 56-man crew (not counting the player characters). Equally useful are 26 rumo(u)rs about the Outrim Void to entice the characters, as they explore. The five pages of library data serve a similar purpose. This is not an "adventure module" in the sense players of Dungeons & Dragons or other RPGs would recognize. Instead, it's a collection of aids to the referee to aid him in building a wide variety of situations that might arise as the characters travel from world to world throughout the Outtim Void.

Leviathan is thus a reminder of an earlier period of the hobby, before gamers expected companies, in the words of OD&D's afterward, to do the imagining for them. Like The World of Greyhawk, Adventure 4 provides referees with an outline to which they are expected to add whatever details they needed or desired. And those details could vary widely from referee to referee and campaign to campaign rather than being bound up in a rigid canon, a concept that was, if not completely unknown, at least highly unusual in those days. By today's standards, then, Leviathan is something of a throwback and why I rate it so highly.

Done with Dungeons & Dragons?

As I alluded to yesterday, I increasingly feel as if I don't have anything interesting left to say about Dungeons & Dragons. On some level, that's understandable. There are nearly 4500 posts on this blog and, though I haven't done an inventory of just how many of them are specifically about D&D, I think it's safe to wager that more than half of them – that's over 2000 posts – pertain to the game in some fashion. With that much virtual ink spilled over a single roleplaying game, even if it is the single most popular and successful one, what more is there for me to say?

Part of the problem, though a small one, is that it's been some time since I actually played any version of Dungeons & Dragons. I kicked the then-current edition of D&D to the curb in 2007, right before I began my OD&D journey and started this blog. I never played either 4e or 5e, as I was perfectly happy, when I wanted to play Dungeons & Dragons, to make use of one of the TSR editions of the game, whether the Little Brown Books, AD&D, or B/X – except that I rarely did so. It's ironic that this should be the case, since Grognardia began in large part as an exploration of the history of D&D and, by extension, the larger RPG hobby.

Of course, one might reasonably ask, "But weren't you playing Labyrinth Lord and Swords & Wizardry and Lamentations of the Flame Princess and [insert your favorite retro-clone here]? Aren't they just D&D with the serial numbers filed off? Indeed, wasn't that the whole point in their creation?" Similarly, "Haven't spent the last decade playing Empire of the Petal Throne, whose rules are basically OD&D with some changes added?" For that matter, "Isn't Secrets of sha-Arthan, your personal science fantasy game, just like EPT, another variant on good ol' D&D? How can you say you haven't been playing Dungeons & Dragons?"

These are all fair questions, but, as I noted, my not playing D&D is only a small part of the problem. A much bigger one is simply that, for whatever reason, I don't think I've had any genuinely original insights into the game in a very long time. Sure, I can – and do – mine old Dragon articles or TSR era products for little tidbits of trivia, but it's rare that any of this is insightful. They're mostly exercises in pure nostalgia, exactly the kind of thing detractors of the Old School Renaissance have been criticizing for years. I don't think there's anything inherently wrong in indulging in nostalgia from time to time, especially when your readership is made up overwhelmingly of middle-aged men who remember the glory days of our hobby. However, I don't want that to be the only thing this blog is known for.

2024 is the 50th anniversary of the publication of Dungeons & Dragons. My intention was to devote a lot of time to looking at OD&D and its rules and history. Here we are, almost at the end of the year, and I've done very little of that. I've started and deleted more posts about OD&D and D&D generally than I have about any other game or topic. In almost every case, I either discovered I'd already written about the topic before or that what I wanted to say was rather trite. In a moment supreme irony, even the topic of this post is one I broached only a couple of months ago. It really does seem as if, when it comes to D&D at least, I've done it all – or at least all that I find interesting enough to devote the time to write about.

This is why I'm now looking to spend more time writing about Traveller in the new year. It's a game I've played almost as long as Dungeons & Dragons and about which I am still very passionate. More than that, it's a game about which there's still a lot more I could say. The well of Traveller commentary is far from dry, whether I'm writing about its rules, its history, the Third Imperium setting, or my own involvement in the game's fandom or publications. I feel as if I could write about Traveller for a very long time and not repeat myself than I often do with D&D.

As always, I wrestle with the issue of just how interesting non-D&D topics are with many readers. My most popular posts continue to be those that touch on Dungeons & Dragons in some way, while those that stray farthest from it aren't nearly as well liked. It's a frustrating conundrum. Ultimately, though, I've concluded that, if I'm to continue writing the blog, I need to write primarily for myself, which probably means I'm going to dial down the number of D&D-centric posts – not eliminate, mind you, just reduce. To a very great extent, Dungeons & Dragons is the hobby, so there's no way I could remove coverage of the game entirely, even if I wanted to do so (which I don't). However, I do want to get back into writing insightfully about older games that interest me, hence the increase in Traveller content.

I assure you: I'll write about more than Traveller. As much as I adore the game, I don't think I could make it the subject of every post. Plus, Grognardia began as and remains a broader blog than any one game. The shift I'm making now and into next year is simply a rebalancing of focus rather than the wholesale rejection or closing off of other options. 2025 will certainly bring changes around here, but being "done with Dungeons & Dragons" in a definitive way is not one of them.

Crypt of the Undead

Did anyone own this game? I ask, because I very vividly remember the advertisements for it, like this one that appeared in issue #69 of Dragon (January 1983). Epyx was a very prolific publisher of early computer games, some of which I did actually played, but Crypt of the Undead was not one of them. From what I've been able to gather from online sources, it wasn't all that good. If so, that's disappointing, given how evocative this ad is. I'd much rather learn that it's a forgotten gem, so, if you owned or played it, I'd like to know more.

December 16, 2024

REPOST: The Articles of Dragon: "Charting the Classes"

One of the characteristics of what I call the Silver Age of D&D is an obsession with mathematics, using it for a wide variety of purposes, from determining the best way to model falling damage to proving if one's dice "be ill-wrought." In issue #69 (January 1983) of Dragon, Roger E. Moore offered up yet another new field for mathematical analysis: class "balance." Many old school gamers think worrying about such matters is a peculiarly modern notion, but it's not. For almost as long as I've played the game, I've known players who fretted over whether this class or that class was "overpowered" or "underpowered" compared to the others. It's a concern I've never really worried about myself, partially because I think all but the most egregious mechanical differences take a backseat to what actually happens at the table. Nitpicker and hair splitter I may be about many topics relating to D&D but this isn't one of them.

One of the characteristics of what I call the Silver Age of D&D is an obsession with mathematics, using it for a wide variety of purposes, from determining the best way to model falling damage to proving if one's dice "be ill-wrought." In issue #69 (January 1983) of Dragon, Roger E. Moore offered up yet another new field for mathematical analysis: class "balance." Many old school gamers think worrying about such matters is a peculiarly modern notion, but it's not. For almost as long as I've played the game, I've known players who fretted over whether this class or that class was "overpowered" or "underpowered" compared to the others. It's a concern I've never really worried about myself, partially because I think all but the most egregious mechanical differences take a backseat to what actually happens at the table. Nitpicker and hair splitter I may be about many topics relating to D&D but this isn't one of them.However, I'm hardly representative of anyone but myself and I expect that, when Moore wrote this article he was speaking on behalf a sizable number of gamers who had a sneaking suspicion that some AD&D character classes were better (or worse) than others -- and he was going to prove it. Moore's analysis hinges on comparing the classes according to accumulated experience points, not level. His thesis is that, by examining the relative strengths and weaknesses of each class at certain XP benchmarks, he might get a sense of which classes are more (or less) potent than others. In doing this, Moore discovers that, for the most part, AD&D's classes are reasonably balanced against one another, with two significant exceptions, along with a third point of discussion.

The first anomaly concerns druids, which Moore says are unusually tough compared to other classes. Compared to clerics, they advance very quickly and, more importantly, they continue to gain full hit dice all the way to 14th level, which also nets them more Constitution bonuses as well. Druids thus wind up being comparable to fighters at mid-levels and even surpassing them at higher levels. Consequently, he recommends increasing the druid's XP requirements to compensate. The second anomaly concerns monks, which Moore says are too weak in terms of hit points for a class that is supposed to fight hand-to-hand. He recommends that they have D6 hit points. Finally, Moore says -- along with nearly every AD&D player I knew back in the day -- that bard, as presented in the Players Handbook, needs to go. He recommends Jeff Goelz's bard as a replacement.

In the end, "Charting the Classes" is actually a very modest and limited analysis of AD&D's character classes and Moore's suggestions are all quite reasonable. I believe I even adopted his recommendation regarding druids, as I know from experience that they were more potent than they had any right to be. Still, I largely find the idea of "balance" between the classes a Quixotic obsession that's played a lot of mischief with D&D in its later incarnations. But it is, unfortunately, a long and deeply held concern of many gamers and I don't expect it to ever go away.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers