James Maliszewski's Blog, page 30

January 31, 2025

42nd-Level Demigod

When I was in the seventh grade, I won first prize at my school's science fair and so was sent, along with a classmate, who'd won second prize, to compete in the state science fair. I was understandably very excited about this, but also a bit nervous, too. I thought my project – a Newton car – good. However, I didn't think it stood much of a chance of winning an award at the state level. I wasn't completely right about that. I won an honorable mention, which is only a couple of steps up from a participation trophy, or so I thought at the time. Meanwhile, my classmate, who was also my best friend, won an actual award. I was happy for him, of course, but also a bit jealous.

During the state science fair, my classmate and I spent most of our time in a large auditorium, waiting with our projects so that we could talk to the judges that roamed the place throughout the day. For reasons I've never understood, he and I were not placed near one another, so we couldn't talk. Fortunately, I'd brought some books to read while I waited, one of them being the AD&D Monster Manual. I spent much of my time perusing its pages to pass the time, as there were often large gaps between when I spoke to one judge and when I'd speak to the next one.

The kid whose science project was next to mine – it had something to do with plants and photosynthesis, the details of which elude me – took notice of my Monster Manual and recognized it. Turns out he was also a Dungeons & Dragons player. This perked me up quite a bit, since, if I couldn't talk to my friend and classmate about D&D, at least I could talk to someone about my favorite pastime. I sometimes look back with envy with how easily my younger self could carry on enthusiastic conversations with total strangers simply on the thin basis of a shared interest. Nowadays, I can scarcely imagine doing such a thing.

During the course of the conversation, this kid let slip that his current character was "a 42nd-level demigod." I asked him to explain what he meant by that. He then launched into a lengthy accounting of the events of his campaign, in which his character had done all manner of over-the-top things, including slaying a significant number of the deities in Deities & Demigods. His character, as a consequence, had risen not only rise to the lofty level of 42, but had also stolen a portion of his vanquished foes' divine power and ascended to the level of demigod, gaining the standard divine abilities listed in that book (among other things, like many of the artifacts and relics in the Dungeon Masters Guide).

I did my best not to be rude or roll my eyes at this, but it was difficult. I asked lots of probing questions about his campaign and why his Dungeon Master had allowed this. I suppose it's good that the kid had zero self-awareness. He didn't pick up on my concealed tone of disdain. Instead, he answered all my questions and recounted, in some detail, not just the epic battles in which his demigod character had fought, but also the fact that his DM had been restrained in rewarding him, since, despite all his victories, his character "still only a demigod." How does on respond to that?

I was reminded of this memory yesterday, when I read some of the comments to my post about Dolmenwood. I was genuinely pleased – and a little surprised – that people enjoy reading about the characters and events of the various campaigns I'm refereeing. "Let me tell you about my character" has long been a phrase to send shivers down one's spine. I recall that, at the one and only GenCon I attended, the employees of a game company (White Wolf?) were all wearing shirts mocking this, for example. Consequently, I've long been somewhat reluctant to post too much about what I'm doing in my games. As fun as RPG campaigns are for the people actually involved in them, they're frequently both impenetrable and a little boring for those on the outside.

However, now that I've seen that people are, in fact, interested in them, I plan to talk about them a bit more. I probably won't go on about them at any length – I don't want to overwhelm you like the kid with the 42nd-level demigod – but I will make a more concerted effort to write posts about them. I might do a weekly or biweekly "campaign update" in which I keep everyone appraised about how things are unfolding. If there's a character or event deserving of more detail, they might warrant a separate post, especially if I think doing so has a wider applicability. I've done this in the past on a couple of occasions in recent years, so it's probably a worthy consideration for the future.

So, look forward to more discussions of House of Worms, Barrett's Raiders, and Dolmenwood in the weeks and months to come.

January 29, 2025

Thoughts on Dolmenwood

Recently, a couple of readers took note of the fact that, under the header "What I'm Refereeing" on the lefthand column of this blog, I've included

Dolmenwood

, published by Necrotic Gnome. However, unlike my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne and Barrett's Raiders Twilight: 2000 campaigns, I've never posted about this. This is absolutely true, though the omission was not intentional – far from it, in fact, as I have nothing but praise to offer about Dolmenwood, both as a fantasy setting and as a game. Indeed, I'm really enjoying Dolmenwood and consider it one of the best "new" fantasy roleplaying games I've played in some time.

Recently, a couple of readers took note of the fact that, under the header "What I'm Refereeing" on the lefthand column of this blog, I've included

Dolmenwood

, published by Necrotic Gnome. However, unlike my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne and Barrett's Raiders Twilight: 2000 campaigns, I've never posted about this. This is absolutely true, though the omission was not intentional – far from it, in fact, as I have nothing but praise to offer about Dolmenwood, both as a fantasy setting and as a game. Indeed, I'm really enjoying Dolmenwood and consider it one of the best "new" fantasy roleplaying games I've played in some time.I put "new" in quotation marks, because, rules-wise, Dolmenwood's not really new. It's a very close descendant of Old School Essentials, which is itself a very close restatement of the 1981 Moldvay/Cook version of Dungeons & Dragons (or B/X, as many people call it). How does it differ from B/X, I'm sure some of you will ask? Most obviously, it has its own classes and races, some of them unique to the setting. Likewise, it uses the dreaded ascending armor class and has its own saving throw categories. There are few other small differences, mostly in terms of presentation, but, for the most part, the rules of Dolmenwood are so close to B/X (or OSE) that I don't think anyone already familiar with those – or, for that matter, almost any version of old school D&D – will have much trouble picking it up.

Where Dolmenwood shines, though, is its setting, the titular Dolmenwood, a large, tangled forest at the edge of civilization that's filled with intrigued, secrets, magic, and lots of fungi. If I were to sum up the setting in a simple phrase, it would be "fairytale fantasy," even if that doesn't quite do Dolmenwood justice. It's like a weird cross between Jack Vance's Lyonesse, Machen's The White People, and Dunsany's The King of Elfland's Daughter, with touches from Twin Peaks and The Wicker Man, among many other influences. As a place, Dolmenwood is weird and eccentric, filled equally with whimsy and terror.

A big part of what makes Dolmenwood such a dichotomous place is the lurking presence of Fairy, which is to say, the otherworldly realm of the elves and other supernatural beings, the most powerful of which were long ago cut off from the mortal world by a coalition consisting of the Duchy of Brackenwold (who rules the wood), the Pluritine Church (who serves the One True God), and the secretive people known as the Drune (who have their own agenda). Elves and fairies are no longer as common as they were in the past, but their machinations can still be felt. In particular, the Cold Prince, the lord of winter eternal, seeks ways to regain his dominion over Dolmenwood.

Of course, there are lots of contending factions within Dolmenwood – the Duchy, the Church, the fairies and their nobles, witches, the Drune, and the wicked Nag-Lord, a trickster figure who serves as a literal agent of Chaos, corrupting the land and its peoples. These factions all play roles, large and small, in ensuring that Dolmenwood is never a dull place. One of the things I've found in refereeing this campaign is that I'm never at a loss for adventure ideas, because there's so much going on in the setting. Once the characters started doing what characters do, they soon found themselves enmeshed in all sorts of plots and schemes, gaining allies and enemies in equal measure.

Speaking of characters, there are presently four in the campaign:

Squire (soon to be Sir) Clement of Middleditch: The big-hearted but small-brained of a minor noble sent out into the world to make something of himself (or die trying). He's presently attempting to be knighted by a fairy princess, an idea that appeals to his romantic soul, even if doing so brings with it more than a little risk.Alvie Sapping: A teenaged thief with a quick mind and quicker tongue. He's attached himself to Clement's retinue as a way to travel and, he hopes, make money. Alvie has an intense dislike of bards and other musicians, on account of his no-good father's having been one, which has occasionally been a source of trouble for him (and amusement for everyone else).Waldra Dogoode: A hunter and woodswoman, who's more comfortable in the wild spaces of Dolmenwood than in its more settled ones. She's an expert tracker and an amateur student of the many mushrooms and other fungi in the region. Her ambition is to one day produce a complete and accurate map of the entire Wood.Falin Cronkshaw: A breggle (goat-man) cleric, who was exiled to a small parish because of her insistence that there were in fact breggle saints whom the Church has suppressed. She now travels with her companions hoping to find evidence vindicating her theories. The characters are an interesting bunch and their interactions with one another and the people they meet have been among the highlights of the campaign. Thus far, they've helped a ghost reunite with his love, explored a weird series of caverns, traveled to a remote village overrun with fungus, helped an exiled elf reclaim his home, and journeyed into Fairy as part of Clement's quest for a liege. Along the way, they've seen strange sights and met many unusual people, some of whom would later become important to the unfolding events of the campaign.Unfortunately, Dolmenwood is not yet available for sale, though it should be soon. Having supported Necrotic Gnome's crowdfunding of the game, I have access to advance copies of its three rulebooks (Player's Book, Campaign Book, and Monster Book) and several adventures. They're all very well done, beautifully laid out and illustrated, filled with ideas to spark your imagination. The Campaign Book is especially nice. In addition to discussing at length the various factions I've already mentioned, it also includes a hex-by-hex gazetteer of Dolmenwood. This makes refereeing the game quite easy, as all you need to do is find the hex where the characters currently reside (or through which they're traveling) and read the entry, which usually contains multiple places of interest, major NPCs, and adventure seeds. Truly, this book alone has made refereeing the campaign quite easy. It's a model for what a campaign book should be in my opinion.

There you have it: my brief thoughts on Dolmenwood the RPG and Dolmenwood the setting. If you have any more specific questions, ask me in the comments and I'll do my best to answer them.

Deluxe Traveller

January 28, 2025

Retrospective: Invasion: Earth

By now, I scarcely need to remind people that roleplaying games are an outgrowth of wargaming, specifically miniatures wargaming. More than a half-century after the appearance of Dungeons & Dragons, this is a well-known and indisputable fact. Nevertheless, it's a fact worth mentioning from time to time, if only to provide context for how many early and influential RPGs were created and designed. It's also a reminder that, even though roleplaying games would eventually eclipse their predecessors, wargames remained an important component of the wider hobby for many years (and arguably still are, though I'm far from the best person to make that claim).

By now, I scarcely need to remind people that roleplaying games are an outgrowth of wargaming, specifically miniatures wargaming. More than a half-century after the appearance of Dungeons & Dragons, this is a well-known and indisputable fact. Nevertheless, it's a fact worth mentioning from time to time, if only to provide context for how many early and influential RPGs were created and designed. It's also a reminder that, even though roleplaying games would eventually eclipse their predecessors, wargames remained an important component of the wider hobby for many years (and arguably still are, though I'm far from the best person to make that claim).

Game Designers' Workshop, best known nowadays as the original publisher of Traveller, began its existence in 1973 as a publisher of hex-and-chit wargames. Its first foray into what might be called roleplaying was in 1975 with En Garde!, though the game is closer to a dueling simulator with light character-driven elements than a "true" RPG (similar, in some ways, to Boot Hill in this respect). But, by and large, GDW's output during the first few years of its existence was tabletop wargames – nearly twenty by the release of Traveller in 1977.

Marc Miller, one of the founders of GDW, had long been a science fiction fan and among his first designs at the company (along with John Harshman) was Triplanetary, whose vector-based movement system inspired Traveller's own (and that of Mayday, itself an offshoot of Traveller). He also designed Imperium, a simulation of a series of interstellar wars between the vast, alien Imperium and the plucky, upstart Terran Confederation. Devotees of the Third Imperium setting may recognize this scenario as part of its historical background, but, at the time of its release, Imperium had no connection to Traveller – which hadn't yet been published and, when it was, later the same year, it was devoid of any kind of example setting.

I bring all this up to emphasize that, at GDW, there was a great deal of interplay between its wargames and the roleplaying games it would eventually publish, with one influencing the other and then in turn influencing other games (or even the same ones in later editions). Thus, for example, Traveller incorporates into its official setting the scenario of Imperium, whose second edition in 1990 would then add details from Traveller. I consider this sort of cross-pollination a hallmark of Games Designers' Workshop, a company that, until the very end, was marked by fervid creativity.

1981 is a good example of what I mean. Traveller had, by that point, already been out for four years and had established itself as the hobby's premier science fiction roleplaying game (sorry, Space Opera!). GDW sought to support the game on multiple fronts, revising and clarifying the rulebooks, as well as releasing new ways to play the game, whether large scale interstellar naval battles (Trillion Credit Squadron), miniatures wargaming (Striker), or strategic wargames, like Fifth Frontier War and Invasion: Earth. GDW clearly had big plans for Traveller and its releases that year demonstrate that, I believe.

Unlike Fifth Frontier War, whose scope covers several subsectors of the Spinward Marches during a "current" war within the timeline of the Third Imperium, Invasion: Earth is both much smaller and "historical," which is to say, taking place in the past of the setting. Set about a century before the "present day," Invasion: Earth focuses on the final stages of the Solomani Rim War (or the War for Solomani Liberation, if your sympathies lie in that direction), as Imperial forces attempt to conquer Terra, a major bastion of the Solomani Cause. As the homeworld of humanity (or humaniti, according to Traveller's unique orthography), Terra holds great symbolic importance to the Solomani, who see themselves as its true children, in contrast to the Imperium, whose culture and very blood have been corrupted by contact with non-Terran aliens.

Invasion: Earth, as its title suggests, is very narrowly focused on the attack and defense of the solar system, culminating in the planetary invasion of Terra. There's thus both space combat and ground combat, each reflecting a different theater of the ongoing Imperial invasion and Solomani counterattack. Rules-wise, it's fairly similar, both in terms of its specifics and its overall complexity, to Fifth Frontier War, which is ti say, it's a proper wargame for hex-and-chit aficionados, not something simplified for casual players like myself. Consequently, I never played Invasion: Earth, even as I admired the copy I saw in the collection of my friend's father – a common theme in my early encounters with wargames.

As I said above, GDW clearly had big plans for Traveller at the time of this game's release. Though intended primarily as a historical game, which, in the setting's timeline, the Solomani lost, there are notes in the back of the rules about how to use the game to simulate invasions of other planets within the Traveller universe. There are also suggestions on how to use the events of the war as fodder for adventures, either in the past or in the present of the Third Imperium setting. I wonder whether anyone ever took up these options for their own Traveller campaigns.

Invasion: Earth, like Fifth Frontier War, has long fascinated me. I love the idea of wargames or simulations intended to flesh out or expand upon some aspect of a roleplaying game's setting, but I've rarely had the opportunity to make use of it myself. For instance, I long wanted to find a way to play out a war in my House of Worms campaign, but I never had the opportunity to do so – or indeed a clear sense of how I'd make it work, but I keep thinking about it nonetheless.

January 27, 2025

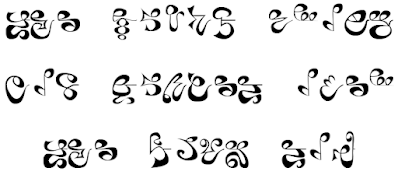

The Articles of Dragon: "A New Name? It's Elementary!"

Since , it seems only right that this week's installment of "The Articles of Dragon" should be Jay Treat's "A New Name? It's Elementary," which originally appeared in issue #72 (April 1983). Though it's a comparatively short article – just three pages and none of them are full pages – it's one of those articles that nevertheless had a profound influence on me.

Since , it seems only right that this week's installment of "The Articles of Dragon" should be Jay Treat's "A New Name? It's Elementary," which originally appeared in issue #72 (April 1983). Though it's a comparatively short article – just three pages and none of them are full pages – it's one of those articles that nevertheless had a profound influence on me. Treat begins by noting that "an appropriate and authentic name can add flair to any character's persona." He explains what he means by this by way of illustration. The Old English language has, to the ears of speakers of modern English, "the air of the exotic and archaic." Despite this, most of its sounds are familiar to us even now, making it relatively easy to pronounce. For that reason, Treat recommends using Old English names for fantasy RPG characters, since such names will sound plausibly foreign, while still being something the average gamer can say without much difficulty.

Even more than that, Old English names were typically made up of two or three elements, each of which had its own meaning. Provided one knows the meaning of these elements, one can construct a name that itself conveys something about the character so named. For example, he suggests that the name Windbearn, meaning "child of the wind," might make a suitable name for the King of Good Dragons, Bahamut, while traveling the Material Plane in human form. Windbearn is fine as a name in its own right, but it also reveals something – in this case a secret – about the person who bears the name.

The article includes two random tables of elements, so you can easily create new names with the roll of some dice. Here's part of one of them to give you an idea of what they were like:

When I first read this article, I was thirteen years old and in the eighth grade. Though I, of course, already knew that all names had meaning, this was perhaps the first time I'd ever seen that fact made clear to me. To call it "revelatory" is perhaps too strong a word, but I can think of no other. In the months that followed, I took the lessons of this article to heart. As I began to lay the foundations for the Emaindor setting, for example, I specifically created a kingdom – Rathwynn – that took inspiration from pre-Norman England and I used this article and other sources to help me come up with appropriate names for the people and places there. This would eventually lead to my doing similar things for the other cultures of the setting.

When I first read this article, I was thirteen years old and in the eighth grade. Though I, of course, already knew that all names had meaning, this was perhaps the first time I'd ever seen that fact made clear to me. To call it "revelatory" is perhaps too strong a word, but I can think of no other. In the months that followed, I took the lessons of this article to heart. As I began to lay the foundations for the Emaindor setting, for example, I specifically created a kingdom – Rathwynn – that took inspiration from pre-Norman England and I used this article and other sources to help me come up with appropriate names for the people and places there. This would eventually lead to my doing similar things for the other cultures of the setting.That's why, even though "A New Name? That's Elementary!" is a very brief, probably forgotten article in the annals of Dragon, it's always been special to me. It's an article that further reinforced my growing feeling that language and names are important topics worthy of consideration in roleplaying, not mere afterthoughts. (It's also the forerunner of a series of other languages articles that appeared later this year in the magazine, many of which also captivated me as a kid, about which I'll have more to say in the coming weeks.)

January 26, 2025

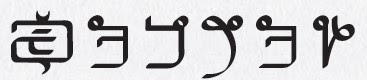

What's in a Name?

Since I was a child, foreign languages (and foreign alphabets) have fascinated me. I'm almost certain that my fascination was a direct result of my having spent untold hours staring at the endpapers and appendices of the

Random House Dictionary of the English Language

that detailed the evolution of various writing systems and the relationships between Indo-European languages. Though I've never mastered any language other than English, I've formally studied a bunch of them, which has only strengthened my interest in tongues other than my own. Reading The Lord of the Rings probably played a role, too.

Since I was a child, foreign languages (and foreign alphabets) have fascinated me. I'm almost certain that my fascination was a direct result of my having spent untold hours staring at the endpapers and appendices of the

Random House Dictionary of the English Language

that detailed the evolution of various writing systems and the relationships between Indo-European languages. Though I've never mastered any language other than English, I've formally studied a bunch of them, which has only strengthened my interest in tongues other than my own. Reading The Lord of the Rings probably played a role, too.My fascination with languages inevitably carried over into my roleplaying games. Almost from the moment I discovered Dungeons & Dragons, I started creating riddles, puzzles, ciphers, and codes that depended on obscure, esoteric, and/or foreign words. I thought I was being clever, though, judging from the reactions of my friends, they weren't nearly as pleased with my brilliance as I was. Undeterred, I moved on to creating my own languages, complete with their own grammars and vocabularies, hoping that my players would want to make use of them in our games. Alas, outside of coming up with appropriate sounding names for characters and locations for my campaign setting, this rarely happened.

I think names are important. Having good, evocative names helps to lend a sense of place to an adventure or campaign, especially if they're meant to be something other than a generic fantasyland or galactic empire. One of my problems with a lot of RPG settings is that the frequently don't have good names, quite the opposite, in fact. Bad names – or even unimaginative names – take me out of a setting or adventure, which can lessen my enjoyment of them. I realize that not every roleplayer cares about such things, but, for me, they're important. A big part of my enjoyment of roleplaying comes from exploring an imaginary world and, in my opinion, good worlds have good names.

As a setting, Tékumel is well known for its use of constructed languages, most notably Tsolyáni, the language of the titular Empire of the Petal Throne. Everything in the setting, from monsters to gods to even coinage and units of measurement have unique names derived from Tsolyáni or another imaginary language. For someone like myself, that's a huge boon to immersion. However, I know plenty of gamers who are actually put off by it. They don't like having to wrestle with words like Ngóro or Dlamélish or Mu'ugalavyá when playing an RPG. Sure, words like these are more suggestive of a real world with a real culture of its own, but, if they get in the way of actually playing, then what's the point of including them?

This is something I think about a lot. Since I've lately been writing a bit more about Thousand Suns , I'm reminded of the fact that, in that game, I make use of the constructed international auxiliary language Esperanto. I did that for a number of reasons, though one of the main ones was that a number of sci-fi books that inspired me, like Harry Harrison's "Stainless Steel Rat" series, for example, used Esperanto as the universal language of mankind. So, in Thousand Suns, I use Esperanto words and names in place of more common English ones as a way to add flavor to the game's meta-setting. I don't expect anyone to actually speak Esperanto while playing any more than anyone is expected to speak Tsolyáni while playing Empire of the Petal Throne. Even so, I've occasionally got complaints about the use Esperanto and its peculiar orthography (e.g. ĉ instead of ch or ĝ instead of j).

I've been pretty upfront about the fact that Tékumel was a big influence on me as I developed the setting of Secrets of sha-Arthan . One way that Tékumel has definitely influenced me is the use of unfamiliar, non-English words for people, places, and creatures within the setting. I really like the way these words have helped me to get a stronger handle on the various cultures that exist in sha-Arthan and how they relate to one another, but, as with Tékumel, I can easily imagine that someone not as keen on the use of odd words might find them an impediment rather than an aid to their enjoyment of Secrets of sha-Arthan.

It's a tough line to walk. My own interests and inclinations are to indulge my own love of exotic words, even if it's discouraging to some potential players. At the same time, one of my goals with both Thousand Suns and Secrets of sha-Arthan is to present something that were more easily accessible than the games and books that inspired them. Consequently, I'm constantly second guessing myself when it comes to how hard to lean into idiosyncratic nomenclature. I'd appreciate hearing your thoughts about this topic, especially if you can point to your experiences with games/books that either succeeded or failed to make use of peculiar names and words to help build a unique setting.

January 23, 2025

What is Thousand Suns?

I've rather surprisingly received several comments and emails about Thousand Suns and how it relates to Traveller. In retrospect, I suppose it's not really all that surprising, since I briefly touched on the game last week, in my post "Traveller and I." So, in the interests of answering some of the more basic questions people might have about Thousand Suns, I'm presenting this post. Because my goal here is to be as complete but succinct as possible, I won't be able to answer every possible question here. If you have any other questions, feel free to leave them in the comments to this post or drop me a line at the address found in the "About Me" tab above.

I've rather surprisingly received several comments and emails about Thousand Suns and how it relates to Traveller. In retrospect, I suppose it's not really all that surprising, since I briefly touched on the game last week, in my post "Traveller and I." So, in the interests of answering some of the more basic questions people might have about Thousand Suns, I'm presenting this post. Because my goal here is to be as complete but succinct as possible, I won't be able to answer every possible question here. If you have any other questions, feel free to leave them in the comments to this post or drop me a line at the address found in the "About Me" tab above. Thousand Suns is a science fiction roleplaying game I wrote in 2007 and then first released in 2008. The current version of the game (the one available at the link above or the sidebar to the left) came out in 2011. It's not really a new edition so much as a revision of that original version. In addition to having a much better layout and graphic design, it's also better organized and (I hope) clearer, with lots more art. The 2011 edition has its flaws, but none of them have yet convinced me that it's time to do another revision of the game.

I wrote Thousand Suns as an homage both to the imperial science fiction I've loved since my youth and to Traveller. By "imperial science fiction," I mean primarily literary SF from the '50s, '60s, and '70s that features mighty galactic empires and whose plots take inspiration from the 19th and early 20th century Age of Imperialism. Think authors like Anderson, Asimov, Piper, Pournelle, and the so forth and you'll have a pretty good idea what I'm talking about. These are the authors and stories that captivated me as a child and with whom I still strongly associate science fiction. Thousand Suns was thus, from the very beginning, a self-indulgent project intended to make a science fiction RPG whose primary audience was me.

Previously, Traveller had filled that role. Back in 2007, though, I had pretty burnt out on Traveller. I'd been playing it since the early 1980s and had thoroughly immersed myself in both its rules and its official Third Imperium setting. I'd also written professionally for the game, during both its Traveller: The New Era and GURPS Traveller incarnations. At that point, I thought I'd learned enough about Traveller that I could improve upon it, creating a better game – or at least one that better suited me and my personal preferences as both a referee and a player. I did say this was a self-indulgent project, did I not?

Specifically, I wanted to create a generic science fiction rules set, which is to say, one without an official setting. Rather than being a game about any one setting, I wanted to present a toolbox that allowed the referee to create his own imperial science fiction setting. In this, I was inspired by Traveller itself, which, in its original 1977 release, was a game just like this. Over time, though, the Third Imperium increasingly came to dominate Traveller, so much so that, in my opinion, the game became about roleplaying within that setting rather than being a toolbox for creating one's own setting.

Now, I love the Third Imperium and consider it my favorite fictional setting of all time. But, after almost fifty years of development, the Third Imperium isn't the most welcoming to newcomers to the game. That's why I intentionally designed Thousand Suns without a setting of its own. Instead, it has a "meta-setting" – a flexible outline of a setting, in which some details have been provided, along with lots of "blank spaces" for the referee to fill in himself according to the kind of setting he wishes for his campaign. For example, I don't specify whether the main human interstellar state is a federation or an empire. I simply call it "the Terran State" and provide lots of options on how to portray it, from an idealistic and democratic alliance to an ironfisted tyranny and everything in between. My goal, above all, was to make something that was both adaptable and accessible.

Rules-wise, Thousand Suns is pretty straightforward. Character generation is either by lifepath or point buy, depending on the wishes of the player. Characters are defined by five abilities ranked from 1 to 12 and skills similarly ranked. Skill tests use a 2D12 roll under a target number based on a combination of the relevant skill rank and an appropriate ability. The amount by which the roll is under that target number is important, because, in many cases it helps to determine the effect, like damage in combat. Rolls of 2 are dramatic successes, while rolls of 24 are dramatic failures, with each having its own effects. All in all, it's a pretty simple system, though, like all system, there are wrinkles here and there, once you get into the weeds of modifiers and edges cases.

The rulebook (also available in Spanish) contains everything you'd ever need to play – character generation, sample aliens, combat rules, equipment, psi powers, starships, trade, world generation, etc. I tried very hard to make good use of all 272 pages of this 6"×9" book. I like to think I succeeded, though there is a companion book called Starships that expands upon the rules for space vehicles, including the starship construction system. There's also Five Stars, which presents another sample sector (one is included in the rulebook), a new alien race, and an adventure that involves both. I once had plans to produce a few other books to support the game, but a combination of factors, including my focus on this blog, distracted me from doing so.

Compared to Traveller, Thousand Suns is, I think, a bit simpler rules-wise, but not hugely so. It's also a bit more "modern" in its approach to science fiction, though, again, not hugely so. For example, there are cybernetics and robots in the rulebook, things Traveller has never really made much space for. I also included lots more advice on designing an imperial SF setting than Traveller ever did, because, as I said at the beginning of this post, I wanted Thousand Suns to be accessible to newcomers who'd never played this kind of science fiction roleplaying game before.

That said, I still call Thousand Suns "a love letter to Traveller," because it's very much informed by my decades of playing that game, which I still adore and consider one of the best RPGs ever designed. Thousand Suns is not a replacement for Traveller so much as another take on the same subject matter, one with slightly different emphases and esthetics reflective of my own idiosyncratic preferences. If you're a fan of Traveller, you might find Thousand Suns useful as a source of ideas, but its rules are sufficiently different that none of its content can be used without modification.

This turned out to be a lot longer of a post than I intended and I'm not certain I said everything I wanted to say. If you have any questions I didn't answer about Thousand Suns, go ahead and leave a comment below or send me an email. I'll do my best to answer them.

January 22, 2025

Retrospective: Monster Manuscript

The very first AD&D book I bought was the Monster Manual, which I acquired through a Sears catalog store using money my grandmother had given me for Christmas. This would have been in early 1980, probably January or February, not long after I was introduced to Dungeons & Dragons. I absolutely adored that book and spent untold hours poring over its pages. Even now, I still consider the original Monster Manual one of the best books ever published for the game, if only for the way it expanded the implicit setting of AD&D, never mind the range of opponents available to the referee.

The very first AD&D book I bought was the Monster Manual, which I acquired through a Sears catalog store using money my grandmother had given me for Christmas. This would have been in early 1980, probably January or February, not long after I was introduced to Dungeons & Dragons. I absolutely adored that book and spent untold hours poring over its pages. Even now, I still consider the original Monster Manual one of the best books ever published for the game, if only for the way it expanded the implicit setting of AD&D, never mind the range of opponents available to the referee.A big part of the genius of D&D is that it's built from modular elements, like character classes, spells, magic items, and, yes, monsters. Simply adding a new one here or there can change the game in all sorts of ways, keeping it fresh and opening up new avenues for exploration and development. As a kid, I was especially fond of seeing new monsters in the pages of Dragon, in adventure modules, and in expansion books such as the Fiend Folio and Monster Manual II. My motto then was "you can never have too many monsters."

Consequently, I was always on the lookout for sources of new monsters to add to my AD&D campaign – and I wasn't very picky. Recently, a comment on my post about piercer miniatures unintentionally reminded me that Grenadier Models published a 32-page monster book in 1986, called the Monster Manuscript. According to multiple online sources, the book was given away for free to purchasers of a particular set of miniature figures produced by Grenadier. However, I'm fairly certain I got my copy in the mail simply because I was on the mailing list for the Grenadier Bulletin newsletter. On the other hand, this was nearly forty years ago, so it's quite possible I'm mistaken about that.

Regardless, I owned a copy of the Monster Manuscript, which features a striking cover by Ray Rubin, depicting a night hag riding a helsteed, two of the monsters included in the book (more on that shortly). Rubin was the cofounder of Grenadier, along with Andrew Chernak, but he's probably best known for having painted most of the color box covers for Grenadier figures, going all the way back to its licensed AD&D sets, if not before. The Manuscript's text is attributed to Don Wellman, who was apparently a sculptor at the company, much like John Dennett, who did all the interior black and white art.

Grenadier, you may recall, once held the license to produce official AD&D miniatures, a license they lost in 1982. In the aftermath of that loss, Grenadier rebranded their fantasy figures under the name Dragon Lords, many of which were identical to their old AD&D sculpts under new names. However, after a few years, the company wanted to create new sculpts of their monsters and, to promote that endeavor, they released the Monster Manuscript, which also became the name of the Dragon Lords sub-line devoted to fantasy creatures. All of the monsters included in the book thus had corresponding figures released for them over the course of 1986 and '87.

The introduction to the book (by Wellman) is mostly self-promotion about the game line, but it does include a section that I think is interesting from a historical point of view:

The creature descriptions and gaming stats included in the MONSTER MANUSCRIPT are my perspectives. They are provided as merely food for thought. If you like them the way I've presented them – great! If not, feel free to change them however you see fit; adapt them to your own fantasy world. I tend to believe that the word, "Official", is one which has been used too much in the gaming industry over the years. Imagination is what fantasy is a li about, so why place unnecessary restrictions on it? Fantasy and science fiction fans have to be some of the most creative and intelligent people anywhere, so utilize your abilities, don't be afraid to try something a little different just because it's not labeled "Official". If you've got a yearning for Lawful Good troll warriors, go for it!

It's hard not to look at this section as a dig at Gary Gygax/TSR and their emphasis on only using "official" products at the gaming table. Grenadier had probably suffered financially as a result of their having the AD&D license pulled, so I can hardly blame Wellman for a little bit of snark on the subject in his introduction.

Judging by their stats, the monsters included in the Monster Manuscript are clearly intended for use with Dungeons & Dragons, specifically AD&D. Here's an example of one of the entries. It's for a floating eye, a beholder knock-off:

As you can see, the entry is similar to what you'd find in the Monster Manual, but abbreviated in such a way as to avoid being too similar. To the best of my knowledge, TSR never objected to the content of the Monster Manuscript, so I assume Grenadier's change to the format was sufficient to avoid legal challenges. There are over 100 monsters in the book, many of them being what you'd expect – creatures from folklore and mythology. Others are, like the floating eye, non-union equivalents to AD&D monsters, often with names that are surprisingly close to their predecessors, like the "blinc dog," "ruster beast," and "owlbeast," to name a few. Likewise, Dennett's accompanying illustrations are frequently reminiscent of those found in the Monster Manual and elsewhere, leaving no question of what they're supposed to be in the minds of knowledgeable gamers.

As you can see, the entry is similar to what you'd find in the Monster Manual, but abbreviated in such a way as to avoid being too similar. To the best of my knowledge, TSR never objected to the content of the Monster Manuscript, so I assume Grenadier's change to the format was sufficient to avoid legal challenges. There are over 100 monsters in the book, many of them being what you'd expect – creatures from folklore and mythology. Others are, like the floating eye, non-union equivalents to AD&D monsters, often with names that are surprisingly close to their predecessors, like the "blinc dog," "ruster beast," and "owlbeast," to name a few. Likewise, Dennett's accompanying illustrations are frequently reminiscent of those found in the Monster Manual and elsewhere, leaving no question of what they're supposed to be in the minds of knowledgeable gamers. Where the Monster Manuscript differed, though, was in its descriptions. Many included little details that gave the monster an origin or context that I found imaginative or that included bits of world building. For example, many weird or hybrid animals are noted as having been tainted by Chaos, while others reference other planes and dimensions. None of it is exceptional stuff, but some of it's flavorful enough that I can still remember it. That's more than I can say of many other monster books I've read over the years and why I think back fondly on the Monster Manuscript even now.

Traveller Distinctives: Social Standing

This post is the start of a new series, Traveller Distinctives, in which I look at an aspect of Traveller's rules that I consider unique or otherwise distinctive, whether from the perspective of other roleplaying games generally or science fiction RPGs specifically. The series will be both irregular in frequency and in its subject matter. That is, I'll post new entries in it as often as I like and I won't be following any kind of clear program. This isn't a "cover to cover" series so much as a "things James finds distinct about the Traveller rules" series. Additionally, I should point out that I'll generally be sticking to the text of the original 1977 rules, with occasional references to the 1981 version.

This post is the start of a new series, Traveller Distinctives, in which I look at an aspect of Traveller's rules that I consider unique or otherwise distinctive, whether from the perspective of other roleplaying games generally or science fiction RPGs specifically. The series will be both irregular in frequency and in its subject matter. That is, I'll post new entries in it as often as I like and I won't be following any kind of clear program. This isn't a "cover to cover" series so much as a "things James finds distinct about the Traveller rules" series. Additionally, I should point out that I'll generally be sticking to the text of the original 1977 rules, with occasional references to the 1981 version.To kick things off, I'm starting small: Social Standing. Social Standing (or SOC) is one of the six "basic characteristics" all characters possess, along with Strength, Dexterity, Endurance, Intelligence, and Education. While the first four have clear analogs in OD&D, as does their being six in number, SOC has no such antecedent. Indeed, I'm not sure of any other significant roleplaying games published by 1977 that includes something similar, but, as always, I'm happy to be corrected.

According to Book 1, SOC "notes the social class and level of society from which a character (and his family) come." A little later, in the section on naming a character, there's a subsection devoted to titles, which reads (italics mine):

A character with a Social Standing of 11 or greater may assume his family's hereditary title. The full range of titles is given in Book 3. For initial naming, a Social Standing of 11 allows the use of Sir, denoting hereditary knighthood; a Social Standing of 12 allows use of Baron, or prefixing von to the character's surname.

What's notable here is that Traveller associates Social Standing with nobility and hereditary nobility at that. The referenced section from Book 3 – which, intriguingly, is found in the chapter about encounters – elaborates on this a bit.

Persons with social standing of 11 or greater are considered to be nobility, even in situations where nobility do not take an active part in local government. Nobility have hereditary titles and high standing in their home communities.

The emphasis on "home communities" is interesting, as is the mention of "local government." This is, I think, evidence that, in 1977 Traveller at least, there's little to no notion of an immense, sector-spanning government like the Third Imperium. Instead, there are just scattered worlds or perhaps small multi-world groupings. The ranks of nobility are, as follows:

11 knight/dame12 baron/baroness13 marquis/marchioness14 count/countess15 duke/duchessThe list is an idiosyncratic one in that it ranks a count higher than a marquis, something not found in either the English or French systems of precedence with which I am familiar. Likewise, the pairing of the French marquis with the English marchioness is odd, but it's the future, so who cares? The text continues:At the discretion of the referee, noble persons (especially of social standing 13 or higher) may have ancestral lands or fiefs, or they may have actual ruling power.

This section is noteworthy, because a common knock against Traveller in my youth was that there was little to no explicit benefit to having a high SOC (and the title that went with it) after character generation. This was even true after the release of Citizens of the Imperium, which introduced an entire Noble career. In any case, what's obvious is that Traveller as written assumes a universe in which monarchy and aristocracy are still commonplace and effective – an egalitarian Star Trek future this is not!

Ranking above duke/duchess are two levels not reflected in social standing: prince/princess or king/queen are titles used by actual rulers of worlds. The title emperor/empress is used by the ruler of an empire of several worlds.

Note "several worlds," not the thousands of the Third Imperium and other interstellar states of the later official GDW setting. Note, too, that the text states that a prince or king is an "actual ruler" of a world, again implying that space is full of governing monarchies of one sort or another.

The only other place where Social Standing plays an important role in Traveller is in resolving a character's prior service. Characters with SOC 9+ have an improved chance of gaining a commission in the Navy, while those with SOC 8+ have an improved chance of gaining a promotion in the Marines. This makes sense if the default assumption is that many, if not most, worlds have a hereditary aristocracy, since careers in the Navy and its subordinate service, the Marines, have been historically viewed as prestigious in similar historical societies on Earth. Likewise, Navy and Marines – along with the Army – can acquire improved SOC as part of mustering out, reflective no doubt of the esteem in which such services are held in such aristocratic societies.

What I find most noteworthy about social standing and the rules governing it in Traveller is how there is of it. Consider that SOC is one of only six characteristics possessed by all characters, suggesting that Marc Miller considered it as foundational to a character as Strength or Intelligence. Despite this, there's not much present in the text of 1977 Traveller (or, for that matter, 1981) to guide the player or referee in understanding how it's meant to be used or what it means for the implied universe of the game. Instead, we get only hints here and there. The later Third Imperium setting is more explicit, in that there's an emperor and archdukes and so forth, but, even then, how this works for titled player characters is left somewhat vague.

For me, though, SOC is a distinctive element of Traveller, something we don't see in any contemporary RPG, science fiction or otherwise. It's a big part of why I don't consider the base game truly "generic" without modification. Putting social standing (and the possibility of hereditary titles) on par with other characteristics has strong implications for the kinds of settings for which it was designed. I'll return to this thought in my upcoming post about jump drive, since there are a number of connections between these topics, as I'll explain.

January 21, 2025

REPOST: Conan of Cross Plains

Janus must be very fond of writers, for so many were born this month: J.R.R. Tolkien, Clark Ashton Smith, Edgar Allan Poe, Abraham Merritt and, today, Robert Ervin Howard. Of them all, Howard is possibly unique in having created a character – Conan – who is a genuine pop cultural icon, his name recognized even by people with no prior connection to pulp fantasy. The irony is that that recognition often acts as an impediment to appreciating Howard's genius in having created him. Indeed, the popular conception of Conan bears only a passing resemblance to the character who first strode onto the pages of Weird Tales in December 1932.

Janus must be very fond of writers, for so many were born this month: J.R.R. Tolkien, Clark Ashton Smith, Edgar Allan Poe, Abraham Merritt and, today, Robert Ervin Howard. Of them all, Howard is possibly unique in having created a character – Conan – who is a genuine pop cultural icon, his name recognized even by people with no prior connection to pulp fantasy. The irony is that that recognition often acts as an impediment to appreciating Howard's genius in having created him. Indeed, the popular conception of Conan bears only a passing resemblance to the character who first strode onto the pages of Weird Tales in December 1932.It may sound fantastic to link the term "realism" with Conan; but as a matter of fact - his supernatural adventures aside - he is the most realistic character I ever evolved. He is simply a combination of a number of men I have known, and I think that's why he seemed to step full-grown into my consciousness when I wrote the first yarn of the series. Some mechanism in my sub-consciousness took the dominant characteristics of various prize-fighters, gunmen, bootleggers, oil field bullies, gamblers, and honest workmen I had come in contact with, and combining them all, produced the amalgamation I call Conan the Cimmerian.It's a pity that this character, this amalgamation of so many real people Howard met in Depression era Texas, isn't the one with which so many are familiar today. He is, for my money, vastly more interesting than the dim, loincloth-wearing, stuffed mattress to be found in so many popular portrayals of the Cimmerian.

--Robert E. Howard to Clark Ashton Smith (July 23, 1935)

Of course, Howard himself has fared little better in the popular imagination than has his most famous creation. To the extent that anyone even knows any facts about the author's life, they're likely based on distortions, misrepresentations, and outright lies, such as those L. Sprague de Camp peddled in Dark Valley Destiny. Fortunately, the last three decades have seen the rise of a critical re-evaluation of both REH and his literary output, finally allowing both to be judged on their own merits rather than through the lenses of men with axes to grind.

This is as it should be. Robert E. Howard was a man like any other. He had his vices as well as his virtues; there is no need more need to reduce discussions of him to mere hagiography than there is to ill-informed criticisms. But men, particularly artists, need to be understood in their proper context, historical as well as cultural. Until comparatively recently, Howard hasn't been given that chance. Like Conan, he's been reduced to a caricature, a laughable shadow of his full depth and complexity that illuminates little about either his life or his legacy.

As the quote above makes clear, Conan may have been a man of the Hyborian Age but he was born in Depression era Texas and, I think, is most fully understood within that context. This is equally true of Howard himself, as Mark Finn noted in Blood and Thunder, a much-needed biographical corrective to De Camp:

One cannot write about Robert E. Howard without writing about Texas. This is inevitable, and particularly so when discussing any aspect of Howard's biography. To ignore the presence of the Lone Star State in Robert E. Howard's life and writing invites, at the very least, a few wrongheaded conclusions, and at worst, abject character assassination. This doesn't keep people from plunging right in and getting it wrong every time.It's often claimed that Howard led a tragic life but I'm not so sure that's true. If anything, he's had a far more tragic afterlife, for, despite of all the Herculean efforts made to elucidate his life and art, he is still so often remembered as "that writer who killed himself because he was upset about his mother's death." Couple that with the disservice done to his creations and it's a recipe for the frustration of anyone who reveres his memory, warts and all.

Yet, there is reason to hope the tide may eventually turn. Del Rey has done terrific work in bringing Howard's writings – and not just his tales of Conan – back into print. Better still, these are all Howard's writings, not the hackwork pastichery of others. In fact, it's becoming increasingly difficult to find those faux Conan stories on bookstore shelves. It's my hope that, at the very least, this will ensure that future readers will have a better chance to encounter the genuine articles than I did when I first sought out stories of the Cimmerian as a young man. Likewise, the facts of Howard's own life are also becoming more well known, at least among scholars and dedicated enthusiasts of fantasy. It may be some time before past falsehoods are cast aside for good but it's at least possible to imagine that now, whereas it was not even a few years ago.

Like the 119th birthday of Robert E. Howard, that's something worth celebrating.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers