James Maliszewski's Blog, page 44

September 6, 2024

How Do You Solve a Problem Like Kirktá? (Part IV)

While the House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign may be winding down, it's still far from over. As discussed in three previous posts, the player characters have stopped in the city of Koylugá on their way across the kingdom of Salarvyá on their way to explore Mihálli ruins to the northeast. While in Koylugá, one of the characters, Kirktá, has found himself engaged to be married to Chygár, niece of the city's ruling prince, Kúrek. The engagement is a stratagem intended to force the characters to act as his agents as part of his bid to secure the Ebon Throne, when the current – and insane – king vacates it in death. Neither he nor his niece has any real intention of seeing this marriage take place. It's part of a typically Salarvyáni scheme to achieve a much greater end.

The characters do not like being used as pawns in someone else's game. This turn of events has stiffened their spines and so they have decided to use it as a way to advance their interests. Rather than simply acquiescing to the terms of the marriage dictated to them by Kúrek, they have fought hard for their terms. Nebússa's wife, Srüna, a formidable woman in her own right, has acted as their negotiator and pushed for a number of things Kúrek seems opposed to. Chief among these is that the marriage happen before their departure from Koylugá and that Chgyár should accompany her husband when they do so.

Kúrek was reluctant to accept these terms. He preferred that the marriage only happen after the characters had headed to the lands of the Gürüshyúgga clan to which he was sending them. Further, he was quite adamant that Chgyár should remain in Koylugá until then. These facts led the characters to suspect that they were being lied to about the Kúrek's true plans, but they had insufficient evidence to determine his true motives. So, they simply instructed Srüna to push even harder for an earlier wedding date and having Chgyár join their expedition once it was completed. Surprisingly, Kúrek eventually agreed.

Not long after this happened, Chgyár asked to speak with Kirktá. She begged him not to go through with the wedding – at least not until after his journey. Kirktá saw no reason to agree and told her so. This made her increasingly angry, to the point of panic. Once it became clear that Kirktá had made up his mind to marry her, despite her protestations that she had no interest in doing so, she finally sent him away in exasperation, saying, "I have grown tired of you and these endless conversations. If dying with you is the only way to end them, I am resigned to that fact. Begone."

It took a while before Kirktá understood what she had just said. Nebússa was now worried. Chgyár's use of the phrase "dying with you" suggested that, as they suspected, Kúrek had something more in mind than a simple marital alliance. Srüna was then dispatched to speak with Chgyár, in the hope that she might clarify matters. While she would not answer certain questions directly, she did explain that Kirktá was being sent to the Gürüshyúgga clan not merely as an emissary of her uncle but as a sacrifice. More significantly, the word she used was a very specific, technical term in the Salarvyáni language for a kingly sacrifice of the kind that occurs when the ruler of Salarvyá is judged too infirm to sit upon the Ebon Throne any longer. He is then impaled as a sacrificial offering to Shiringgáyi, their supreme goddess.

This put a very different spin on things! It also explained Chgyár's extreme reluctance to marry and accompany Kirktá eastward, since she likely believes that she, too, will be sacrificed. While none of the characters yet knew precisely with Prince Kúrek had planned or why, it didn't matter: he was plotting to have them killed under the cover of employing them as his agents. That was enough for the characters to decide that they needed to escape Koylugá as quickly and quietly as possible. The longer they waited, the more likely they were to be captured and sent to the Gürüshyúgga under armed guard.

It was time to act.

The Bishop Returns

September 5, 2024

Hidden Details

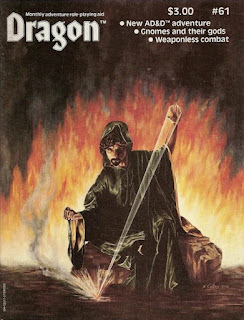

In a comment to my earlier post about level titles beyond Dungeons & Dragons, Tamás Illés pointed out that the later installments of the computer game Wizardry included level titles (as did EverQuest). Not being well versed in the history of the Wizardry, this comment naturally piqued my interest. I spent some time yesterday looking into the matter by seeking out scans of the original manuals online. In doing so, I not only confirmed the truth of the comment – more on that in a future post – but also stumbled across something equally interesting.

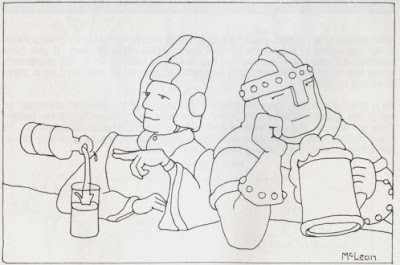

I never owned Wizardry myself. When I played it, I did so on a friend's computer after having watched him play it. Consequently, I don't think I ever saw the game's manual or, if I did, I have no recollection of doing so. That's too bad, because the manual contains notable artwork, like this one, depicting the four basic character classes:

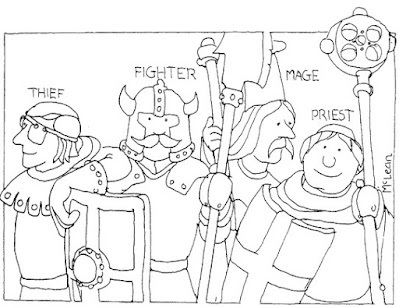

Then, there's this illustration, depicting the four elite character classes:

Then, there's this illustration, depicting the four elite character classes:

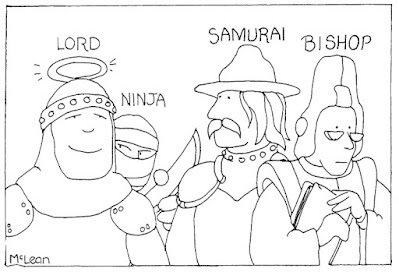

Leaving aside the very odd illustration of the samurai – he looks more like a soldier in Cromwell's New Model Army than a Japanese warrior to me – what immediately caught my eye was the bishop on the far right. He reminded me of this famous illustration from the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide:

Leaving aside the very odd illustration of the samurai – he looks more like a soldier in Cromwell's New Model Army than a Japanese warrior to me – what immediately caught my eye was the bishop on the far right. He reminded me of this famous illustration from the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide:

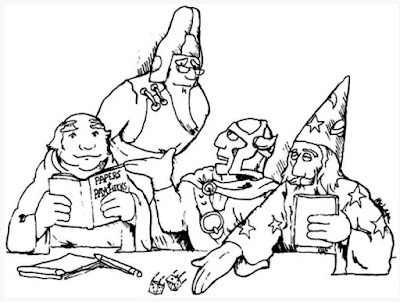

I initially assumed that the Wizardry illustration was an allusion or homage to the DMG piece, since it seemed unlikely that the distinct appearance of the bishop's "miter" was an independent creation (unless perhaps they were both referencing a third source). However, the question was very quick resolved when I finally noticed the artist's signature – McLean. This was clearly Will McLean, the very same artist who provided all those humorous little cartoons scattered throughout the Dungeon Masters Guide (though he is erroneously credited in the Wizardry manual as "Will Mclain."

I initially assumed that the Wizardry illustration was an allusion or homage to the DMG piece, since it seemed unlikely that the distinct appearance of the bishop's "miter" was an independent creation (unless perhaps they were both referencing a third source). However, the question was very quick resolved when I finally noticed the artist's signature – McLean. This was clearly Will McLean, the very same artist who provided all those humorous little cartoons scattered throughout the Dungeon Masters Guide (though he is erroneously credited in the Wizardry manual as "Will Mclain."

This discovery made me happy, because I've been a fan of Will McLean's cartoons for years. I'll post some additional examples of them in an upcoming post.

September 4, 2024

Retrospective: Sabre River

Despite my generally negative feelings toward Frank Mentzer's 1983–1986 revision of the Dungeons & Dragons rules, I have a special place in my heart for the

Companion Rules

. Indeed, I still consider it one of the best things ever produced for any edition of D&D, largely because it made a serious attempt to provide answers to the question of just what characters do when they reach the lofty heights of level 15 and beyond. While the Companion Rules themselves were only partially successful in this regard, TSR also intended to provide additional ideas and guidance for campaigns at this level of play in the form of the CM-series of adventure modules, of which there were ultimately nine.

Despite my generally negative feelings toward Frank Mentzer's 1983–1986 revision of the Dungeons & Dragons rules, I have a special place in my heart for the

Companion Rules

. Indeed, I still consider it one of the best things ever produced for any edition of D&D, largely because it made a serious attempt to provide answers to the question of just what characters do when they reach the lofty heights of level 15 and beyond. While the Companion Rules themselves were only partially successful in this regard, TSR also intended to provide additional ideas and guidance for campaigns at this level of play in the form of the CM-series of adventure modules, of which there were ultimately nine.Of course, as I mentioned in my Retrospective post about one of the modules in this series, this intention wasn't as easy to fulfill as TSR might have wished. Nearly all of the CM modules were flawed in one way or another, especially when it comes to providing a model for campaigns in which many, if not all, of the player characters have risen to rule their own domains. Despite that, many of them nevertheless include clever ideas and interesting concepts that could, if reworked, be useful to the harried Dungeon Master of a Companion-level campaign.

Take, for example, Sabre River, co-written by Douglas Niles and Bruce Nesmith and released in 1984. The module begins with the following:

Have all of your characters settled down and started dominions? Have you wondered if they'll ever get the chance to fight their way through an old-fashioned dungeon again? Yes, they will!

The premise of Sabre River is that a group of four to six characters of levels 18–22 must venture into the Tower of Terror, a dungeon within a volcano, in order to deal with a curse that's been laid upon the land. The land in question is the domain of either an NPC ruler or – preferably – that of one of the player characters. In this respect at least, Sabre River is already an improvement over its immediate predecessor, Death's Ride, which more or less rejected the very idea that a player character's domain should be subjected to the undead invasion depicted in that module.

The idea of a dungeon capable of challenging a party of 18th–22nd-level characters is intriguing. In the D&D circles with which I was familiar at the time, it was generally assumed that, as a character achieved double-digit levels, he would find his challenges in domain rulership and all that that entailed, like mass combats, power politics, and faction play. I suspect that explain why I so rarely saw anyone continue to play a D&D character at such exalted levels: the implied style of play wasn't very appealing to most players and indeed seemed to be a break from what Dungeons & Dragons was assumed to be about. What most players of my acquaintance wanted instead was more of the same, albeit at a great degree of challenge and, in principle, that's what Sabre River provided.

The Tower of Terror is indeed challenging. It's populated by powerful and deadly monsters, like a red dragon, elementals of various types, a beholder, and swarms or flocks of lesser creatures. There's also a commensurate level of treasure, some of it truly staggering, like a roomful of gold ingots worth 800,000gp in total. That only makes sense, of course, since high-level characters need huge amounts of experience points to advance and treasure is the surest source of such XP. Still, I was quite shocked to see these numbers as I re-read the module. For me, these astronomical sums have long been an impediment to my enjoyment of a D&D campaign of this level. Others may feel differently, of course.

Sabre River's challenges also include a handful of tricks, traps, and unusual tactical situations intended to test the players' skills in combat. There's also the central mystery of the curse, how it can be lifted, and what the characters must do to achieve that. It's all very serviceable but far from outstanding – certainly nothing on par with adventures like White Plume Mountain or The Ghost Tower of Inverness when it comes to imagination (and frustration). Mostly, Sabre River is about everything being BIG, from monsters (and their hit point totals) to treasures, which is a little disappointing, especially because I know that Doug Niles is a good designer who's penned some enjoyable stuff over the years.

Sabre River is not a terrible module; it simply doesn't stand out as anything special. Its worst sin, in my opinion, is that it doesn't deviate too much from the mediocre track record of the CM-series, almost none of which take full advantage of the new opportunities and vistas that the Companion Rules opened up to player characters of levels 15 to 25. A shame!

September 3, 2024

Limited Edition

Authentic Dungeon Masters Prefer ...

During the period between 1979 and 1982 when Grenadier Models held the license to produce official Advanced Dungeons & Dragons miniatures, the company ran lots of advertisements in the pages of Dragon magazine and elsewhere. Because they frequently made use of people dressed up in fantasy garb, I've always found them quite memorable (and silly – but in a good kind of way). Here's one I came across from issue #61 (May 1982) while preparing my earlier post from today.

September 2, 2024

The Articles of Dragon: "Call of Cthulhu is a Challenge"

"Dragon's Augury" was the name given to Dragon magazine's recurring review section. At the time I first encountered it, "Dragon's Augury" had no single, dedicated reviewer. A different contributor reviewed each featured gaming product, though there were often contributors whose names I'd see quite regularly, such as Tony Watson and Ken Rolston.

"Dragon's Augury" was the name given to Dragon magazine's recurring review section. At the time I first encountered it, "Dragon's Augury" had no single, dedicated reviewer. A different contributor reviewed each featured gaming product, though there were often contributors whose names I'd see quite regularly, such as Tony Watson and Ken Rolston. Sometimes, though, there'd be a review from a notable figure within TSR, like Gary Gygax, and these naturally caught my attention. A good example of this occurred in issue #61 (May 1982), in which David Cook, author of one of my favorite AD&D modules, wrote a review of the newly released Chaosium RPG, Call of Cthulhu. By the time this review appeared, I already owned a copy and was a great fan of it. Nevertheless, I was very curious to hear what Cook might have to say about it.

Though Cook had a lot of positive things to say about Call of Cthulhu, the overall tenor of his review could probably be called "mixed." After providing a nice overview of both the works of H.P. Lovecraft and the intended playstyle of CoC, he launches into his dissection of the game's flaws. For example, he points out that, while short, Basic Role-Playing, is not very complete, with many ambiguous rules. The same is true of the Call of Cthulhu rulebook itself, which, in addition to ambiguity, includes editorial errors that further contribute to its lack of clarity. In particular, Cook notes that the game's combat system lacks, among other things, "rules for how to deal with cover, movement, surprise, or other situations" that might come up in a fight.

Cook singles out A Sourcebook for the 1920's as "the weakest part" of the boxed set. Its contents, he believes, appear to be little more than "notes and unfinished design work." He finds the alternate character generation rules – one of my favorite parts of the book – to be "inadequately explained" and a source of confusion. Another bone of contention is the game's lack of rules for generating and handling human NPCs, whom Cook imagines will play important roles in any Lovecraft-inspired adventure. Speaking of which, Cook speaks highly of the sample scenarios included in the rulebook.

The review is fairly lengthy and detailed, but it generally goes on in this direction. I get the impression that Cook, as a fan of Lovecraft, may have had high, or at least very specific, hopes for what Call of Cthulhu should have been like and those hopes were not fully met. Even so, he acknowledges that "when played, it's fun." He does caution that, because of its rules gaps, it demands a lot of the referee. Consequently, Call of Cthulhu "is a good game for experienced role-playing gamers and ambitious judges, especially if they like Lovecraft's type of story."

As I mentioned, I already owned a copy of Call of Cthulhu by the time I read this review and was slightly baffled by it. My friends and I had been enjoying it without noticing any of the problems Cook pointed out in his review. That's probably because, as young people – I would have been twelve at the time – our grasp of the rules as written was not always the best and so we frequently made things up when we needed to do so. By contrast, Cook was already an accomplished game designer with a lot of experience both as a writer and a player of both wargames and RPGs. This undoubtedly colored the way he wrote his review, something I didn't appreciate at the time.

I also couldn't fathom why Cook had so many critical things to say about the game, despite his admission that he had found Call of Cthulhu fun in play. If he enjoyed the game, I thought, why point out its flaws? For that matter, how had he even noticed them in the first place? I thought about these and other related questions for some time afterward, which is precisely why I still remember this review more than four decades later. David Cook challenged my own assumptions and blind spots. He'd dared to say critical things about a new game my friends and I had enjoyed. In retrospect, I realize I learned a lot from his approach, even if, in 1982, it made little sense to me.August 29, 2024

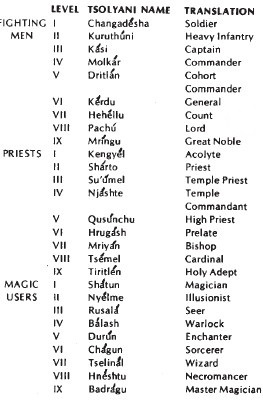

Level Titles: Beyond D&D

Having now covered all of the published TSR era D&D and AD&D character classes with level titles, I wanted to turn to some other RPGs published by the same company that also include them. First up is Empire of the Petal Throne (1975), which only makes sense, as the game's rules were essentially a variant of OD&D. Here is the chart featuring level titles for all three character classes available in that game:

There are a couple of notable ways that this chart differs from its D&D predecessors. The first and most obvious is that these titles aren't in English. Instead, they're in the Tsolyáni constructed language used in the setting, though they are accompanied by rough English translations. Secondly and more importantly, most of these titles have a meaning within the setting. For example, the titles of the fighting man class are, from levels 1 through 6, actual titles within the Tsolyáni legions. Likewise, the titles of both the priest and magic-user classes are those of ranks within the "circles" (an administrative term) of the temple priesthoods and lay priesthoods respectively. In short, these level titles aren't arbitrary names but rather markers of attainment within Tsolyánu.

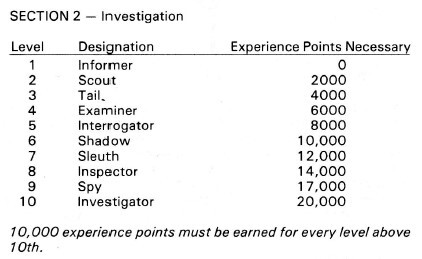

There are a couple of notable ways that this chart differs from its D&D predecessors. The first and most obvious is that these titles aren't in English. Instead, they're in the Tsolyáni constructed language used in the setting, though they are accompanied by rough English translations. Secondly and more importantly, most of these titles have a meaning within the setting. For example, the titles of the fighting man class are, from levels 1 through 6, actual titles within the Tsolyáni legions. Likewise, the titles of both the priest and magic-user classes are those of ranks within the "circles" (an administrative term) of the temple priesthoods and lay priesthoods respectively. In short, these level titles aren't arbitrary names but rather markers of attainment within Tsolyánu. Empire of the Petal Throne is not, however, the only TSR RPG to include level titles. Another one that does so is Top Secret (1980) and its titles seem to have a lot in common with those of Dungeons & Dragons. Take, for example, the titles of the Investigation section:

Like most of their D&D predecessors, the Top Secret level titles (or "designations") are just synonyms related to the class in question, as you can see in the case of the Confiscation section:

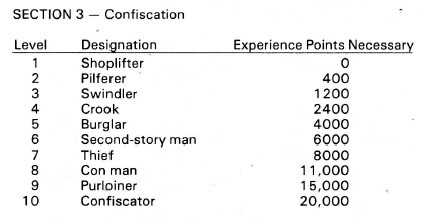

Like most of their D&D predecessors, the Top Secret level titles (or "designations") are just synonyms related to the class in question, as you can see in the case of the Confiscation section:

If anything, the Confiscation titles are even less plausible than those for Investigation. Shoplifter? Crook? Those don't strike me as at all credible internal designations for a covert operative. Consider, too, the Assassination section:

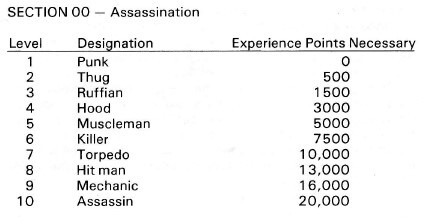

If anything, the Confiscation titles are even less plausible than those for Investigation. Shoplifter? Crook? Those don't strike me as at all credible internal designations for a covert operative. Consider, too, the Assassination section:

Punk? Hood? Muscleman? As I said, these strike me as simply synonyms – and of a decidedly colloquial sort – rather than anything that could be accepted as having any purpose within the world of the game itself.

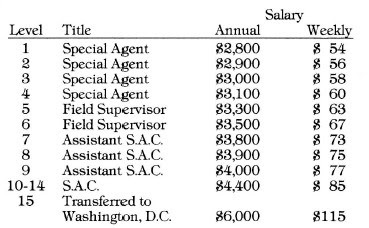

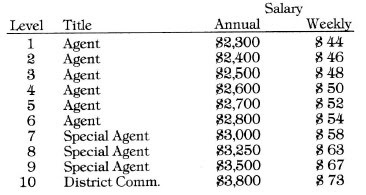

Punk? Hood? Muscleman? As I said, these strike me as simply synonyms – and of a decidedly colloquial sort – rather than anything that could be accepted as having any purpose within the world of the game itself. On the other hand, there's Gangbusters (1982), which includes level titles for some of its character professions, but not others. For example, these are the titles for FBI agents:

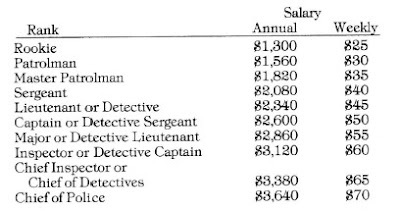

You'll notice several things about this chart. Firstly, not every level has a unique title. Secondly, each increase in level includes a commensurate increase in salary, which has a real in-game effect. The titles in Gangbusters are, in this way, go beyond even those of Empire of the Petal Throne in being something that definitely exists within the game world rather than being simply an artifact of the game rules. For the sake of completeness here are the charts for Prohibition Agents and police officers:

You'll notice several things about this chart. Firstly, not every level has a unique title. Secondly, each increase in level includes a commensurate increase in salary, which has a real in-game effect. The titles in Gangbusters are, in this way, go beyond even those of Empire of the Petal Throne in being something that definitely exists within the game world rather than being simply an artifact of the game rules. For the sake of completeness here are the charts for Prohibition Agents and police officers:

Clearly, Gangbusters puts level titles to the best use of all the roleplaying games so far examined, in that they not only reflect a setting-based reality (i.e. promotion within a character's profession) but also provides a setting-based benefit in the form of increased pay. These are small things, to be sure, and one could reasonably argue that there's no need to present such things in this fashion. However, given that Gangbusters uses a level-based system, albeit one very different from D&D, it makes some sense to do it this way. In any event, I think it's fair to say Gangbusters does level titles better than D&D and Top Secret.

Clearly, Gangbusters puts level titles to the best use of all the roleplaying games so far examined, in that they not only reflect a setting-based reality (i.e. promotion within a character's profession) but also provides a setting-based benefit in the form of increased pay. These are small things, to be sure, and one could reasonably argue that there's no need to present such things in this fashion. However, given that Gangbusters uses a level-based system, albeit one very different from D&D, it makes some sense to do it this way. In any event, I think it's fair to say Gangbusters does level titles better than D&D and Top Secret.

August 28, 2024

Level Titles: Illusionists and the Rest

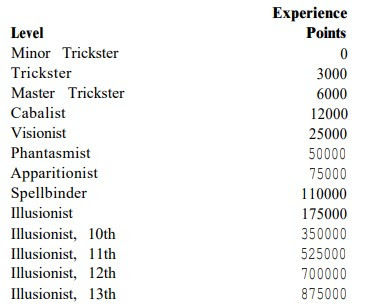

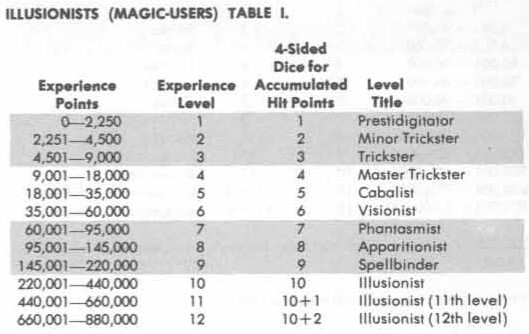

Having already covered the level titles of most of the character classes in Dungeons & Dragons, it's now time to turn to those that remain, some of which are unusual. Let's start with the most straightforward: illusionists. A sub-class of magic-user, illusionists first appeared in volume 1, issue 4 of The Strategic Review (Winter 1975) in an article written by Peter Aronson. As presented there, illusionists have the following level titles:

The AD&D Players Handbook (1978) has an almost identical list of level titles. The only difference is that the original level 1 title, minor trickster, is turned into the level 2 title, in order to make room for "prestidigitator," which also happens to be the level title for a level 1 magic-user. There is, of course, no explanation for this overlap of titles, which is, I think, unique in the game.

The AD&D Players Handbook (1978) has an almost identical list of level titles. The only difference is that the original level 1 title, minor trickster, is turned into the level 2 title, in order to make room for "prestidigitator," which also happens to be the level title for a level 1 magic-user. There is, of course, no explanation for this overlap of titles, which is, I think, unique in the game.

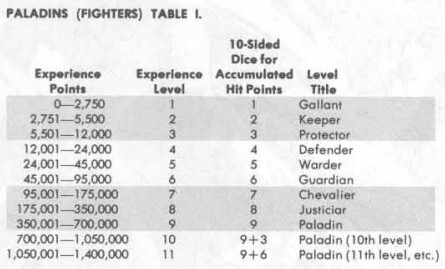

The paladin class first appeared as a kind of proto-prestige class to the fighting man in Supplement I to OD&D (1975). In that form, the class has no distinctive level titles. Those didn't appear until the stand-alone version of the class was presented in the AD&D Players Handbook several years later.

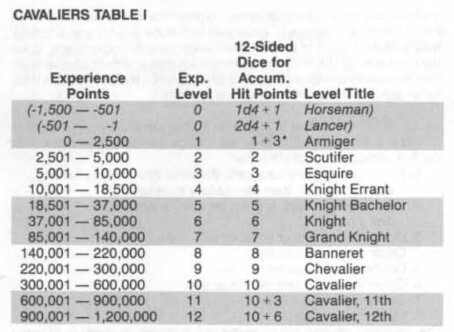

Unearthed Arcana (1985) formally introduced the cavalier class into AD&D. The book also made the paladin, previously a sub-class of the fighter, a sub-class of the new cavalier, which makes a certain amount of sense, given its knightly overtones. The cavalier's level titles, includes those of its two 0-levels.

Unearthed Arcana (1985) formally introduced the cavalier class into AD&D. The book also made the paladin, previously a sub-class of the fighter, a sub-class of the new cavalier, which makes a certain amount of sense, given its knightly overtones. The cavalier's level titles, includes those of its two 0-levels.

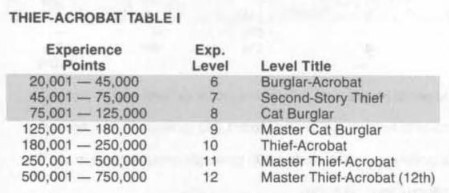

Speaking of "proto-prestige classes," Unearthed Arcana also gives us the thief-acrobat. The thief-acrobat is a specialist version of the thief that an ordinary thief can opt into, starting at 6th level, provided he meets certain ability score requirements for Strength and Dexterity. Interestingly, thief-acrobats have their own distinct level titles.

Speaking of "proto-prestige classes," Unearthed Arcana also gives us the thief-acrobat. The thief-acrobat is a specialist version of the thief that an ordinary thief can opt into, starting at 6th level, provided he meets certain ability score requirements for Strength and Dexterity. Interestingly, thief-acrobats have their own distinct level titles.

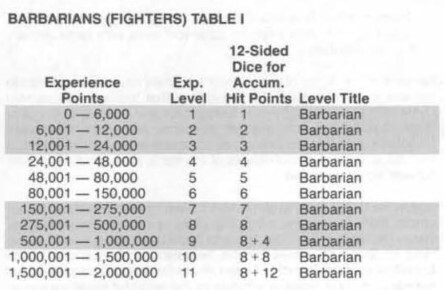

Finally, there is the barbarian class, also appearing in UA. The barbarian probably has the most unusual level title chart of all:

Finally, there is the barbarian class, also appearing in UA. The barbarian probably has the most unusual level title chart of all:

Aside from being funny, what strikes me about the chart above is the implication that level titles actually mean something and are perhaps even bestowed by someone or some group within the world of D&D. Barbarians, as outsiders, aren't part of that world and thus have no such titles. At least, that's how I read it – but I may simply be finding meaning where there is none.

Aside from being funny, what strikes me about the chart above is the implication that level titles actually mean something and are perhaps even bestowed by someone or some group within the world of D&D. Barbarians, as outsiders, aren't part of that world and thus have no such titles. At least, that's how I read it – but I may simply be finding meaning where there is none.I'll return to the question of the meaning of level titles in a future post, since I've still got at least a couple more to present before I can offer any attempt at a summation of my thoughts. Stay tuned.

August 27, 2024

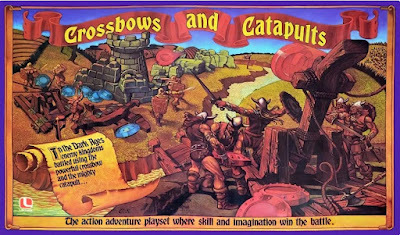

Retrospective: Crossbows and Catapults

My childhood circle of neighborhood friends was quite large and included boys of all ages, some of them much younger than myself. For example, when I first discovered Dungeons & Dragons during the Christmas holidays of 1979, I was in the fifth grade, but my closest friends outside of school were a year or so younger than me. I also had friends who were younger still, often the little brothers of my other buddies. Being preteen boys, age didn't really matter all that much to us, because we all, more or less, enjoyed the same pastimes and it was always better to have more playmates. This was especially so after we started playing D&D and other RPGs.

My childhood circle of neighborhood friends was quite large and included boys of all ages, some of them much younger than myself. For example, when I first discovered Dungeons & Dragons during the Christmas holidays of 1979, I was in the fifth grade, but my closest friends outside of school were a year or so younger than me. I also had friends who were younger still, often the little brothers of my other buddies. Being preteen boys, age didn't really matter all that much to us, because we all, more or less, enjoyed the same pastimes and it was always better to have more playmates. This was especially so after we started playing D&D and other RPGs.Even so, my discovery of D&D coincided with – and probably facilitated – my abandonment of toys or anything that to my youthful self smacked of being "kid stuff." Children in those in-between years of 10 to 12 are, in my experience, quite concerned with appearing to be more "grown up" than they were just a few short years before. This concern can manifest in the ostentatious rejection of overt symbols of their childhood, like toys, games, and other entertainment that don't match up with their nebulous conception being older. That's certainly how it was for me.

Of course, having a friend group that included lots of younger boys provided a convenient excuse to transgress these arbitrary new boundaries between "kid" and "grown up" from time to time. My youngest friend was another's brother and he was about four years younger than me. Though he played D&D with us (and did so very well) he still unapologetically kept one foot in childhood, playing with those little G.I. Joe action figures – everyone knows the "real" G.I. Joe is 12 inches tall! – and other early '80s toys that the rest of us publicly eschewed. Our looking at and admiring his toys was no sin against our newfound maturity, since we weren't playing with them, you see. Such fine distinctions were very important to us and we did our Pharisaical best to maintain them.

Even so, there were egregious exceptions and Crossbows and Catapults was one of the bigger ones I can remember. Released in 1983, when I had just started high school, Crossbows and Catapults was simultaneously the kind of "family game" that I'd never have bought for myself, but was secretly happy had been given as a Christmas gift to my friend's kid brother. As we often did, my friends and I spent the Christmas break visiting one another's homes and passing judgment on our holiday hauls. We'd also use it as an opportunity to try out anything we deemed worthy of our time.

Crossbows and Catapults had rules, but I honestly cannot recall them. Even if I could, I'm fairly certain we never made much use of them, preferring to do our own thing with it. The game is supposed to be played by two players, but it was very easy to change this to two sides, which is what we did. Each side – Vikings or Barbarians – is given a number of little figurines, plastic blocks and structures, and a rubber band-powered ballista ("crossbow") and catapult that fired chunky discs that reminded me of checkers. To be played at all, you need a large, open area with a fairly flat surface, preferably an uncarpeted floor. We used to play on my friends' basement floor or on the ping-pong table we also used for Car Wars.

As I said, Crossbows and Catapults had rules, but we preferred simply to build up walls and castles from the plastic bricks, place the figures, and then take turns shooting at them with our ballistas and catapults. We'd done this before with army men when we were younger and had great fun with it. Now, thanks to the cool little plastic siege engines included with the game, we could unleash a more potent – and accurate – kind of destruction upon the world. It was childish, of course, but that's probably why we had such fun with it. At that particular stage in our lives, on the cusp of or just entering our teen years, we thought were ready to leave our childhoods behind, even though, on some level, we clearly were not. Crossbows and Catapults afforded us the chance to be kids again without feeling self-conscious about it, which is why, to this day, I still have fond memories of this stupid game.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers