James Maliszewski's Blog, page 53

June 10, 2024

I Did It Again

I have a regular problem: I sit down to write a post and then discover, as I am adding links to other related posts, that I've already written about the topic in question. In some cases, the previous post is from last year or the year before that, but, in others, the previous post is from more than a decade ago. It's very frustrating, but it seems increasingly inevitable. After so long and so many posts, the odds of my doing this at any given time are pretty high. At the same time, I take the fact that I don't do it more often as a good sign, since it suggests I still have some new thoughts left in me.

I'll do better tomorrow; I promise.

June 9, 2024

A (Very) Partial Pictorial History of Kobolds

One of the things I've long appreciated about early Dungeons & Dragons is the way that it took vaguely defined folkloric, mythological, and literary monsters and made them distinctive to the game. The pig-faced orcs of the Monster Manual are a good example of what I'm talking about, though there are many others, like kobolds. In folklore, kobolds don't have a clear and universally accepted description. From what I recall, they're short and vaguely dwarfish. That's probably why Holmes, in his Basic Set, calls them "evil dwarf-like beings" (and why I opted for something similar in my Dwimmermount and Urheim setting).

Within the history of D&D, however, the image immediately below is (I think) the very first time we're shown a kobold. It's from the AD&D Monster Manual (1977) and is drawn by Dave Sutherland, based on an exceptionally vague description that speaks only of their coloration, small horns, lack of hair, and red eyes.

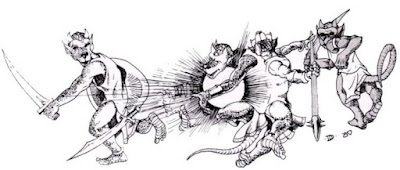

The MM also includes a second Sutherland kobold illustration, this one a full-page piece.

The MM also includes a second Sutherland kobold illustration, this one a full-page piece.

I like this second illustration a lot, because it gives a sense of how, despite having only 1–4 hit points each, kobolds could nevertheless be dangerous foes, because of their numbers. The illustration is also useful in showing the little monsters from several different angles. I suspect, more than any other, this piece is responsible for my early conception of kobolds and their physical characteristics – short, scaly dog-men with horns. Precisely why Sutherland settled on this appearance, I have no idea, since there's nothing in either folklore or the Monster Manual's own description to suggest it.

I like this second illustration a lot, because it gives a sense of how, despite having only 1–4 hit points each, kobolds could nevertheless be dangerous foes, because of their numbers. The illustration is also useful in showing the little monsters from several different angles. I suspect, more than any other, this piece is responsible for my early conception of kobolds and their physical characteristics – short, scaly dog-men with horns. Precisely why Sutherland settled on this appearance, I have no idea, since there's nothing in either folklore or the Monster Manual's own description to suggest it.That same year (1977), Minifigs in the UK picked up the license to produce official Dungeons & Dragons miniatures. Though the company didn't produce as many figures as did Grenadier later (more on that below), it produced enough that they're often worth examining for insight into the beginnings of D&D as a product line. Take, for example, this figure of a kobold, which looks rather similar to the creatures depicted in Sutherland's illustrations, particularly the second, full-page one, right down to the harness he's wearing.

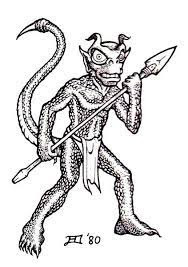

1980's Rogues Gallery features a very memorable depiction of kobolds by Jeff Dee. As you can see, Dee's kobolds look very similar to Sutherland's – almost identical, in fact. In this rendering, they're still short, scaly dog-men.

1980's Rogues Gallery features a very memorable depiction of kobolds by Jeff Dee. As you can see, Dee's kobolds look very similar to Sutherland's – almost identical, in fact. In this rendering, they're still short, scaly dog-men.

Deities & Demigods was published the same year as the Rogues Gallery, but offers up a somewhat different depiction of kobolds. The entry for Kurtulmak, the supreme deity of the kobolds, is accompanied by an illustration drawn by Erol Otus. He's described as looking like a "giant kobold (5½' tall) with scales of steel and a tail with a poisonous stinger). This suggests that what we see below is, more or less, what a kobold looks like. Though there's a very broad similarity with the Sutherland/Dee illustrations, we can see that his face has been flattened into more humanoid proportions, thereby lessening its canine associations.

Deities & Demigods was published the same year as the Rogues Gallery, but offers up a somewhat different depiction of kobolds. The entry for Kurtulmak, the supreme deity of the kobolds, is accompanied by an illustration drawn by Erol Otus. He's described as looking like a "giant kobold (5½' tall) with scales of steel and a tail with a poisonous stinger). This suggests that what we see below is, more or less, what a kobold looks like. Though there's a very broad similarity with the Sutherland/Dee illustrations, we can see that his face has been flattened into more humanoid proportions, thereby lessening its canine associations.

Just below the Otus illustration in the DDG is another one featuring Kurtulmak, this time by Dave LaForce. As you can see, the four kobolds depicted in it look like smaller versions of their god, albeit without horns or scales. To me, LaForce's kobolds look almost simian in apperance.

Just below the Otus illustration in the DDG is another one featuring Kurtulmak, this time by Dave LaForce. As you can see, the four kobolds depicted in it look like smaller versions of their god, albeit without horns or scales. To me, LaForce's kobolds look almost simian in apperance.

Interestingly, 1980 is also the year that Grenadier Models first started producing official Advanced Dungeons & Dragons miniatures under license from TSR. If you look carefully at this photo, what you see are three kobold miniatures whose appearance is not too dissimilar to what we see in the art of Otus and LaForce above. Pay close attention to their flat, humanoid faces and lack of horns.

Interestingly, 1980 is also the year that Grenadier Models first started producing official Advanced Dungeons & Dragons miniatures under license from TSR. If you look carefully at this photo, what you see are three kobold miniatures whose appearance is not too dissimilar to what we see in the art of Otus and LaForce above. Pay close attention to their flat, humanoid faces and lack of horns.

The next year (1981), Otus provides a different illustration for a kobold, this time appearing in Tom Moldvay's D&D Basic Set. This illustration accompanies an entry that describes kobolds as "small, evil dog-like men ... [that] have scaly rust-brown skin and no hair."

The next year (1981), Otus provides a different illustration for a kobold, this time appearing in Tom Moldvay's D&D Basic Set. This illustration accompanies an entry that describes kobolds as "small, evil dog-like men ... [that] have scaly rust-brown skin and no hair."

This version has neither horns nor a tail, but its canine head is unmistakable. I find it notable that the module

Keep on the Borderlands

, included with the '81 Basic Set, has a rumor table that makes mention not just of "hordes of tiny dog-men" (i.e. kobolds), but also "big dog-men" or gnolls, suggesting a connection between these two monsters that I don't believe I've ever seen developed in the entire history of D&D.

This version has neither horns nor a tail, but its canine head is unmistakable. I find it notable that the module

Keep on the Borderlands

, included with the '81 Basic Set, has a rumor table that makes mention not just of "hordes of tiny dog-men" (i.e. kobolds), but also "big dog-men" or gnolls, suggesting a connection between these two monsters that I don't believe I've ever seen developed in the entire history of D&D.

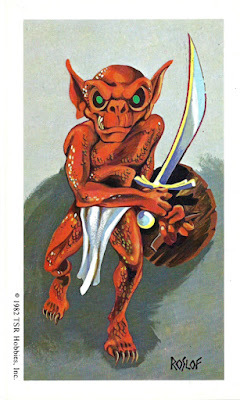

Above, we can see Jim Roslof's illustration of a kobold from 1982's AD&D Monster Cards. This illustration looks to me to be a further development of the Otus/LaForce version of kobolds – flat faces, no horns, no visible tail. In fact, they look rather like the goblins depicted in that same product, which makes for an interesting call-back to OD&D (and Chainmail before it), which seems to treat kobolds as if they were simply a species of goblin, or at least a closely related type of monster.

Above, we can see Jim Roslof's illustration of a kobold from 1982's AD&D Monster Cards. This illustration looks to me to be a further development of the Otus/LaForce version of kobolds – flat faces, no horns, no visible tail. In fact, they look rather like the goblins depicted in that same product, which makes for an interesting call-back to OD&D (and Chainmail before it), which seems to treat kobolds as if they were simply a species of goblin, or at least a closely related type of monster.The first appearance of kobolds in AD&D Second Edition is in the Monstrous Compendium (1989), with this illustration by Jim Holloway:

Holloway's kobold is a kind of two-steps-forward-one-step-back version – broadly consonant with Otus/LaForce/Roslof one but regaining the horns of Sutherland/Dee. Though there's no visible tail, the description in the Monstrous Compendium suggests that they do indeed possess "non-prehensile rat-like tails." It also notes that they "sound like small dogs yapping" and smell like "a cross between damp dogs and stagnant water." This perhaps suggests that the writer (David Cook, Steve Winter, or Jon Pickens) was attempting to restore a bit of the canine connection of early 1e while retaining the overall look established by its later artists.

Holloway's kobold is a kind of two-steps-forward-one-step-back version – broadly consonant with Otus/LaForce/Roslof one but regaining the horns of Sutherland/Dee. Though there's no visible tail, the description in the Monstrous Compendium suggests that they do indeed possess "non-prehensile rat-like tails." It also notes that they "sound like small dogs yapping" and smell like "a cross between damp dogs and stagnant water." This perhaps suggests that the writer (David Cook, Steve Winter, or Jon Pickens) was attempting to restore a bit of the canine connection of early 1e while retaining the overall look established by its later artists.

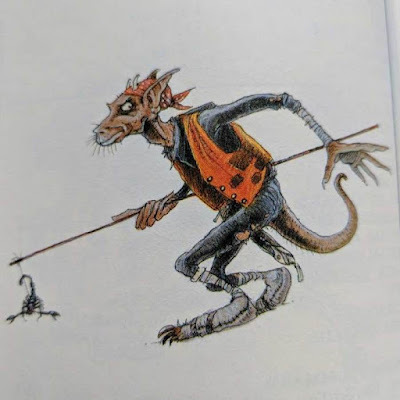

Lastly, there's this illustration from the 2e Monstrous Manual (1993), provided by Tony DiTerlizzi, who's probably best known for his distinctive contributions to the Planescape setting. This version restores the elongated, muzzle-like face of early AD&D, though, to my eyes, it looks more rat-like than canine. The accompanying description is the same as in the earlier Monstrous Compendium, so it's not as if any of DiTerlizzi's alterations were required by a revised text.

Lastly, there's this illustration from the 2e Monstrous Manual (1993), provided by Tony DiTerlizzi, who's probably best known for his distinctive contributions to the Planescape setting. This version restores the elongated, muzzle-like face of early AD&D, though, to my eyes, it looks more rat-like than canine. The accompanying description is the same as in the earlier Monstrous Compendium, so it's not as if any of DiTerlizzi's alterations were required by a revised text.Despite my recent musings about Third Edition, the post-TSR editions of Dungeons & Dragons are beyond the scope of this blog, so I won't be discussing the subsequent development of kobolds. That's probably just as well, since I'm not a fan of their metamorphosis into small lizard/dragon-men. Nevertheless, looking over the pictorial history of this low-level monster has opened my eyes to just how ill-defined the kobold actually is. My own preferred version is heavily indebted to that of the first version I ever saw and I suspect that's probably true of most other D&D players.

Do you have a default vision of kobolds? If so, what does it look like?

June 7, 2024

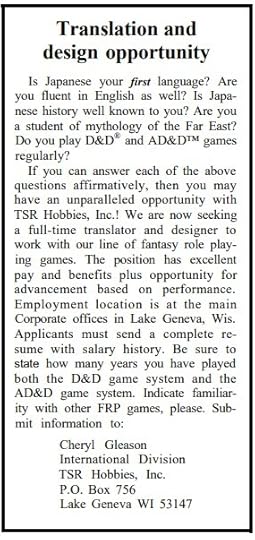

Translation and Design Opportunity

This notice appeared in issue #68 (December 1982) of Dragon:

Though the notice doesn't explicitly say so, I assume the job on offer relates to the project that would eventually become Oriental Adventures. Of course, it could also have been about translating Dungeons & Dragons (and other TSR RPGs) into Japanese. I recall that the first Japanese edition of D&D appeared in 1985 and was a translation of Frank Mentzer's 1984 edition. The fact that the contact person is Cheryl Gleason, a name I've never seen before, doesn't make the matter any clearer.

Though the notice doesn't explicitly say so, I assume the job on offer relates to the project that would eventually become Oriental Adventures. Of course, it could also have been about translating Dungeons & Dragons (and other TSR RPGs) into Japanese. I recall that the first Japanese edition of D&D appeared in 1985 and was a translation of Frank Mentzer's 1984 edition. The fact that the contact person is Cheryl Gleason, a name I've never seen before, doesn't make the matter any clearer.Does anyone out with better insight into the history of TSR know any more?

How Do You Solve a Problem Like Kirktá? (Part III)

When last we left him, Kirktá and his clan-mates were wrestling with the recent revelation that Kúrek Tiqónnu Thirreqúmmu, lord of the city of Koylugá, was somehow aware of the fact that the youthful scholar priest of Durritlámish was, in fact, a hidden heir to the Petal Throne. Further, Kúrek was finalizing the arrangements for the upcoming marriage between Kirktá and his niece, Lady Chgyár – a marriage that no one else, least of all Kirktá, knew anything about. The characters naturally suspected that Kúrek wished to enter into a political alliance with someone of importance within nearby Tsolyánu. Even if Kirktá chose not to participate the Kólumejàlim or "choosing of the emperor," never mind win it, the mere fact that he is the son of the reigning emperor brings with it a host of potential benefits. Marrying his niece to Kirktá thus made a lot of sense. Even so, there were lots of other unanswered questions.

The characters decided that, rather than continue to ponder these matters with insufficient information, they should take the Chlén-beast by the horns. They composed a brief letter to Lady Chgyár, asking if they might speak with her this evening. She replied that she was happy to receive them for an evening meal, during which they could talk. Together, the group made their way to the Thirreqúmmu palace, which served both as the ruling family's domicile and the province's seat of government. After being led through a maze of chambers within the building, they found themselves in a dining hall, where Chgyár and her servants welcomed them.

The young woman wasted little time getting to the point. Chgyár imagined they'd come to see her because they were surprised and perhaps a little shocked by the marriage contract, as well as mention of Kirktá's Tlakotáni lineage. She explained that, despite appearances, she was not actually interested in marrying Kirktá, nor, for that matter, was her uncle. Rather, the contract was meant as an encouragement of compliance in her uncle's political designs. Kúrek is very ambitious. He hopes, upon the death of King Griggatsétsa, to ascend the Ebon Throne as Salarvyá's new monarch. To do that successfully, he needs allies within the kingdom, specifically the Gürüshyúgga family of Tsa'avtúlgu, currently leading a revolt against the capital.

What does any of this have to do with the characters? The Gürüshyúgga family, you see, are worshipers of a deity known as Black Qárqa, a Salarvyáni version of Sárku, the Five-Headed Lord of Worms after whom the House of Worms clan is named. Lord Kúrek believes that the characters, as outsiders, could act as "neutral" intermediaries in the current conflict between the Gürüshyúgga and the King. Of course, their true purpose is not merely to end the conflict but also to make sure the Gürüshyúgga understand that it was Kúrek who engineered its cessation, so that they would, in turn, support his bid for the throne. It is hoped that, because the characters are themselves devotees of the same dark god as the Gürüshyúgga, they might have greater influence than would he or most other Salarvyáni.

If the characters agree to attempt this, Lord Kúrek will keep Kirktá's true lineage a secret. Neither will he have to marry Chgyár, who, for her part, says she "has someone else in mind" for her future husband. The marriage contract is simply a useful prop in the event that the characters do not agree to help. Kúrek can not only reveal that Kirktá is a hidden heir but also that he "toyed with a young woman's affections" – a charge with enough plausibility that it might well be believed by enough people to blacken the reputation of not only Kirktá but his comrades as well.

Before sending them on their way again, Chgyár provided as many answers to their characters' question as she could. Most important among her answers was that the conflict between the king and the Gürüshyúgga stemmed from the former's desire to seize certain devices of the Ancients that the latter reputedly possessed in large numbers and that may well be the source of their own power (the Gürüshyúgga being renowned as sorcerers and stalwart defenders against the dreaded Ssú). She then implied that, if the characters were successful in securing an alliance between her family and them, the Gürüshyúgga might reward them with a few choice items from their arsenal. She then sent them on their way to prepare for the meeting with Lord Kúrek the next morning.

Naturally, the characters still have a lot of questions. Among the most significant concerns how they choose to respond to this. They do not like being strongarmed by anyone, least of all foreign aristocrats. At the same time, their desire to keep Kirktá's imperial status secret places them in a very real bind. If they don't help, Kúrek will reveal it and numerous unhappy consequences may arise from it. How much of a risk are they willing to take? Or is it simply better – or at least safer – to serve as emissaries to the Gürüshyúgga on behalf of Chgyár's uncle?

So many questions, so few answers.

Look the Part You Play

June 6, 2024

Aranalar

Aranalar by Luigi CastellaniAranalar ("Indomitable") is a sword +1, +2 vs the Unmade forged from alchemical steel. Its blade is single sided, forward curving, and,like all Kulvuan osuna, intended to be wielded from the back of a teteku, The blade itself is approximately two feet in length and bears a maker’s mark (not visible in the illustration) that identifies it as a product of the famed Bejanakoru workshop of lost Onoritash, though it is unlikely that its enchantment took place there. The grip is wrapped in ridzor-leather, while its pommel bears an early example of a nasha-charm that would later become commonplace on Kulvuan imperial weaponry.

Aranalar by Luigi CastellaniAranalar ("Indomitable") is a sword +1, +2 vs the Unmade forged from alchemical steel. Its blade is single sided, forward curving, and,like all Kulvuan osuna, intended to be wielded from the back of a teteku, The blade itself is approximately two feet in length and bears a maker’s mark (not visible in the illustration) that identifies it as a product of the famed Bejanakoru workshop of lost Onoritash, though it is unlikely that its enchantment took place there. The grip is wrapped in ridzor-leather, while its pommel bears an early example of a nasha-charm that would later become commonplace on Kulvuan imperial weaponry.Aranalar possesses a single magical ability, from which it receives its name. So long as the sword is held, its wielder is completely immune to the melee attacks of any Unmade of equal or lesser level than himself. This immunity does not apply to either ranged or magical attacks, however. The ability has no duration and is usable at will, so long as the sword is held. Sheathed, Aranalar no longer provides this immunity. Likewise, this immunity extends only to the current wielder of the sword and to no one else.

The precise date of Aranalar’s forging is unknown. However, its magical ability suggests that it was created for use during either the Consolidation of Light (1:1–4) or Daybreak Wars (1:15–25). The third book of Samakan’s Lesser Chronicle of Dawn makes mention of the warrior Besu Tankuli, who, during the Siege of Itixtar, emerged seemingly unscathed after facing off against “an Unmade host the likes of which none have seen since the Epoch of Shadows.” Samakan notes that Besu wielded “a mighty blade, whose enchantment protected him against the twisted creations of the Unmakers on that day.” General Daljan Chayusi (1:301–2:5) unambiguously wielded Aranalar during his career, most famously at the Battle of Uchiran (1: 344). Upon his retirement, he gave the sword to his son, Dalen (1:326–2:3), who was murdered by persons unknown, possibly for his role in the Second Archontic Succession Crisis (1:358). Aranalar was then stolen and disappeared from history, though rumors of its location or current wielder continue to this day.

Criticism and Commentary

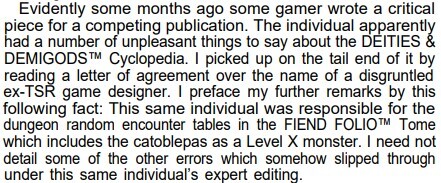

I think it's fair to say that Gary Gygax had a very thin skin when it came to criticisms of the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons game line, even when the criticisms weren't aimed at a book or module in which he had a hand. A good example of what I'm talking about can found in the "From the Sorceror's [sic] Scroll" column he penned for issue #66 of Dragon (October 1982). There, Gygax responds to criticism of Deities & Demigods.

Before getting into the substance of what Gygax says here, a little background. The "critical piece" referenced in the paragraph above appeared in issue #19 of Different Worlds (March 1982). It's a review written by Patrick Amory that ends by stating "Deities & Demigods [is] fit only for the trashcan." Gygax claims that he only heard about Amory's piece after "reading a letter of agreement" written by a "disgruntled ex-TSR game designer." This second letter appeared in issue #22 of Different Worlds (July 1982) and its author is Lawrence Schick, who served as the editor of Deities & Demigods.

Before getting into the substance of what Gygax says here, a little background. The "critical piece" referenced in the paragraph above appeared in issue #19 of Different Worlds (March 1982). It's a review written by Patrick Amory that ends by stating "Deities & Demigods [is] fit only for the trashcan." Gygax claims that he only heard about Amory's piece after "reading a letter of agreement" written by a "disgruntled ex-TSR game designer." This second letter appeared in issue #22 of Different Worlds (July 1982) and its author is Lawrence Schick, who served as the editor of Deities & Demigods.

If you follow the link to Schick's "letter of agreement," you'll see that it's both lengthy and thoughtful in its criticisms. Though he clearly disagreed with the direction James M. Ward took the book, he does not seem to bear any ill will toward the man he calls "a real nice guy." Likewise, that he "really liked the AD&D system and wanted the AD&D products to be the best possible." Schick's criticisms, for the most part, boil down wanting DDG to have closer to Cults of Prax in its approach. That's an absolutely fair criticism in my book, but I'd of course say that, since it's pretty close to my own opinion on the matter. Regardless, I don't think anything Schick wrote is worthy of the intemperate and petty response Gygax offers.

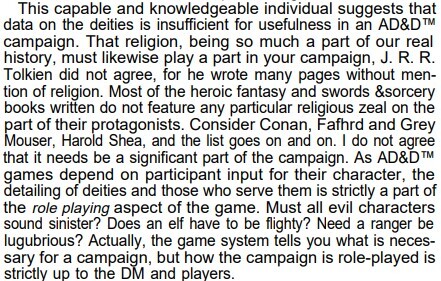

Sadly, Gygax doesn't stop there. He continues his verbal assault against "this capable and knowledgeable individual" in a very bizarre fashion.

Given Gygax's frequent and vociferous disavowals of the influence of Tolkien over his vision of AD&D, I think it's pretty rich of him to turn around and try to use the (admittedly true) lack of religion in Middle-earth as evidence that the kind of book Schick would have preferred is somehow inappropriate for the game line. His references to the works of Howard, Leiber, and De Camp and Pratt seems less disingenuous (and more in keeping with his pulp fantasy preferences), but I'm not sure it serves his original point. If anything, in his flailing attempt to deflect Schick's fair criticisms of Deities & Demigods, he comes close to suggesting a book about gods and religion is unnecessary for AD&D.

Given Gygax's frequent and vociferous disavowals of the influence of Tolkien over his vision of AD&D, I think it's pretty rich of him to turn around and try to use the (admittedly true) lack of religion in Middle-earth as evidence that the kind of book Schick would have preferred is somehow inappropriate for the game line. His references to the works of Howard, Leiber, and De Camp and Pratt seems less disingenuous (and more in keeping with his pulp fantasy preferences), but I'm not sure it serves his original point. If anything, in his flailing attempt to deflect Schick's fair criticisms of Deities & Demigods, he comes close to suggesting a book about gods and religion is unnecessary for AD&D.

This line of attack is all the odder, because Gygax's own articles about the deities and demigods of his World of Greyhawk setting were all quite good and included many of the details that Schick wished to see. He even acknowledges this later in his response, adding that this is appropriate "because they are part of an actual campaign," while DDG was never intended as anything more than "raw material upon which to build a campaign." He then suggests that expecting Deities & Demigods to be more than that is tantamount to "want[ing] someone else to do all your creative thinking for you." What an odd – and condescending – thing to say!

In the end, I think Gygax would have been better off not saying anything at all. I can only assume the fact that Schick, a former TSR employee, publicly offered his own firsthand thoughts about the shortcomings of an AD&D volume stung. I can certainly understand his feelings and might well have felt similarly were I in his shoes. Nonetheless, his response seems disproportionate and, worse, small-minded. Compared to Dragon, Different Worlds had a very small circulation and I doubt that many people were unduly influenced by its negative review, assuming they even saw it. If anything, an immoderate tirade like this one might well have had a greater negative effect on potential buyers.

June 5, 2024

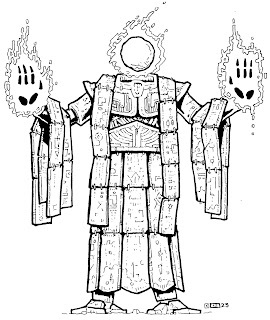

The Unmade

An Unmade Brute by Zhu BajieThe Unmade (or Omajya in the Onha language) are the unnatural servitors of the Unmakers. Transformed by iniquitous sorcery, the Unmade are frightful demonstrations of where the Unmakers' nihilistic philosophy leads if unchecked. They are also a potent threat to the civilized peoples across sha-Arthan (except the continent of Alakun-Tenu, where the priesthood of Ten long ago extirpated them).

An Unmade Brute by Zhu BajieThe Unmade (or Omajya in the Onha language) are the unnatural servitors of the Unmakers. Transformed by iniquitous sorcery, the Unmade are frightful demonstrations of where the Unmakers' nihilistic philosophy leads if unchecked. They are also a potent threat to the civilized peoples across sha-Arthan (except the continent of Alakun-Tenu, where the priesthood of Ten long ago extirpated them).Like their masters, the Unmade first appeared during the Epoch of Strife. Though none can say for certain which of the many Unmaker prophets of those days first twisted Men and beasts to serve them, the names Arkatzo and Trene are often cited by scholars. Arkatzo figures prominently in the legends of Jalisan of Churuga, while Trene is associated with the ruin that bears her name to this day, Trene's Bastion, laid waste by Hejneka during the latter days of the Pechra War.

An Unmade Martinet by Zhu BajieLike their ultimate origins, the process by which the Unmade come to be is not well understood, even after all this time. Large scale alchemy is almost certainly involved, as is metamorphic sorcery of a type unseen since the Epoch of Wonders. Indeed, it has been suggested by some, such as Badisa Selmis in his Compendium of Universal Knowledge, that the Heritor Lords were the first to perfect a method of re-shaping living beings, a method the Unmakers would later improve upon. Others, such as Ajana Solokat theorize that the weird energies of the False World are another important component.

An Unmade Martinet by Zhu BajieLike their ultimate origins, the process by which the Unmade come to be is not well understood, even after all this time. Large scale alchemy is almost certainly involved, as is metamorphic sorcery of a type unseen since the Epoch of Wonders. Indeed, it has been suggested by some, such as Badisa Selmis in his Compendium of Universal Knowledge, that the Heritor Lords were the first to perfect a method of re-shaping living beings, a method the Unmakers would later improve upon. Others, such as Ajana Solokat theorize that the weird energies of the False World are another important component.As one might expect, there is wide variability in the forms of the Unmade. Nevertheless, there are three broadly recognized classes of these beings. The first is by far the most common. Known as Brutes (or Travesties), they are nightmarish mixtures of many types of creatures given humanoid form. No two Brutes look exactly the same but all are aggressive, bestial, and hulking. This type of Unmade periodically gather in hordes to menace city-states or even entire realms.

An Unmade Discarnate by Zhu BajieThe second type is slightly less common but can often be found serving alongside Brutes, where they act as leaders. Called Martinets (or Taskmasters), these Unmade are humanoid in shape, their head replaced by a phase stone that grants them the ability to use one or more sorcery spells, depending on its size and color. Compared to Brutes, Martinets are very intelligent and free-willed, making them a much greater threat.

An Unmade Discarnate by Zhu BajieThe second type is slightly less common but can often be found serving alongside Brutes, where they act as leaders. Called Martinets (or Taskmasters), these Unmade are humanoid in shape, their head replaced by a phase stone that grants them the ability to use one or more sorcery spells, depending on its size and color. Compared to Brutes, Martinets are very intelligent and free-willed, making them a much greater threat.The third and final type is the rarest – and most dangerous. The Discarnates exist simultaneously on sha-Arthan and the World Between. This not only enables them to move quickly from place to place, it also makes them difficult to engage in physical combat. Their dual existence grants them access to sorcery even more potent than that of the Martinets. Fortunately, Discarnates are few in number and seem to serve as special agents or even lieutenants to Unmaker prophets.

As noted above, other types of Unmade may also exist, but are sufficiently uncommon that they lack for widely accepted appellations.

Retrospective: Verbosh

In my youth, I didn't have a lot of direct experience with Judges Guild products. Aside from the

Wilderlands of High Fantasy

, I can probably count the number of JG releases I owned or used on one hand. Partly that's because I was an unrepentant TSR fanboy and looked askance at third-party products, even those that were "approved for use with Dungeons & Dragons," as Judges Guild's were. However, an equally important factor is that, for whatever reason, I rarely saw JG books for sale at the bookstores and hobby shops I frequented. They didn't stock Tegel Manor or City-State of the Invincible Overlord at Waldenbooks, B. Dalton, or Kay-Bee Toys, all of which were my regular sources for RPG materials, the end result of which is that it would be years before I saw many of the products that are now considered classics by connoisseurs of old school roleplaying games.

In my youth, I didn't have a lot of direct experience with Judges Guild products. Aside from the

Wilderlands of High Fantasy

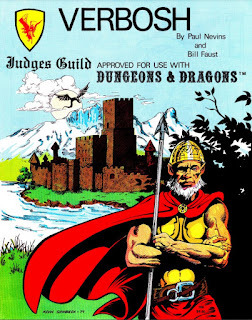

, I can probably count the number of JG releases I owned or used on one hand. Partly that's because I was an unrepentant TSR fanboy and looked askance at third-party products, even those that were "approved for use with Dungeons & Dragons," as Judges Guild's were. However, an equally important factor is that, for whatever reason, I rarely saw JG books for sale at the bookstores and hobby shops I frequented. They didn't stock Tegel Manor or City-State of the Invincible Overlord at Waldenbooks, B. Dalton, or Kay-Bee Toys, all of which were my regular sources for RPG materials, the end result of which is that it would be years before I saw many of the products that are now considered classics by connoisseurs of old school roleplaying games.In the years since, I've therefore made a point of trying to hunt down and read many of the Judges Guild releases which I've seen people discuss online, especially those about which the discussion is largely positive, like Verbosh. Originally published in 1979, Verbosh is an 80-page supplement by Paul Nevins and Bill Faust, two names I do not otherwise recognize. A name I do recognize, however, is Kevin Siembieda, who provides all the interior artwork for this product (the cover is by someone called Bob Hadley), as well as its maps. Siembieda, of course, is the co-founder of Palladium Games and designer of the eponymous The Palladium Role-Playing Game. This was still fairly early in his career, so these illustrations are still amateurish in my opinion, but a step above the Judges Guild standard.

In addition to being the name of this book, Verbosh is also the collective name for a village and fortification nestled along the banks of a river known "the Great Source." Long ago, the fortification was built by a self-styled lord, who named the place after himself. His descendants – all also named Verbosh – inherited his penchant for grandiosity and eventually styled themselves kings. Though some of them achieved genuinely great things, their line eventually "went steadily down hill," according to the text. The latest Verbosh (thirty-first of his line, who call himself "the Magnificent") has been reduced to running a shop that sells meaningless titles of nobility.

Both the village and the fortification are described through a series of keyed locations, in addition to random encounters for daytime and night. Nearly all these locations are shops or services, like an inn, an armorer, or a bakery. Each has an NPC proprietor, with D&D stats and information about his history and personality. Tonally, these descriptions are somewhat whimsical, or at least not entirely serious. For example, the baker is a hobbit who "will bake anything, but it is likely to be poor. His bread is like insulation (and is often used for the purpose)." Of course, the baker is also a polymorphed copper dragon "who thinks his baking is actually good." One's reaction to this reaction is a pretty good gauge of whether you'll like much of the content of Verbosh, which is filled with other examples of such things (e.g. Talc of Umpowder, a blacksmith)

Beneath the fortification is a three-level dungeon to explore. Also nearby is a shipwreck that serves as the basis for an underwater adventure. Taken together, this provides plenty to do for characters who've just arrived in the area. Many of the NPCs in Verbosh also have agendas of their own and can easily become sources of both rumors and employment. Some of these agendas point away from Verbosh itself and toward the wilderness outside the settlement. Naturally, said wilderness is filled with lots of encounters of varying complexity and difficulty. This includes another fortified town/castle named Warrenberg, which itself has a large number of NPCs and locales of a sort similar to those found in Verbosh. Taken together, Verbosh presents lots of opportunities for adventure.

As I said at the beginning of this post, my experience with Judges Guild back in the day was very limited. Viewing them now, what strikes me as how inconsistent their quality was, as well as how amateurish its production values were. This is especially true when compared to TSR's own offerings. At the same time, the better JG books offer the referee a huge amount of raw material from which to work. One might not wish to use any of the books as written, but, as foundations on which to build one's own scenarios, they can be quite good. That's certainly true of Verbosh in my opinion. The sheer magnitude of material in its 80 pages – maps, NPCs, rumors, encounters, and more – is staggering. Yes, a lot of it is much more tongue-in-cheek than I, as a notorious stick in the mud, would like, but it's very easy to ignore, for instance, Federico Fellini's Fast Food business if, like me, you find it a bit silly and use the rest with little trouble.

June 4, 2024

Slaying Monsters Should Be Mostly Fun and Games

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers