James Maliszewski's Blog, page 59

April 10, 2024

Comments

In the wake of my "Whither Grognardia?" post from earlier this month, I learned that a lot of readers find it difficult, if not impossible, to comment on the blog. That certainly explains why the number of comments per post has generally been lower than it was during the first iteration of the blog. In response, I did some poking around to see if the reported problem related to settings that I could change or if it was something else out of my control.

I'm still not sure of the answer. However, I did make a few changes to the comment settings. If you're someone who has, in the past, had difficulty commenting, give it a go and see if anything has changed on your end. If so, I will be pleased. If not, I may need to look into the matter further.

[UPDATE: It would appear that most people can now comment without too much trouble, which is good. However, I should point out that all comments are still manually moderated, in order to stem the tide of spam (of which there is a lot). Consequently, a comment's not appearing immediately doesn't necessarily mean that it didn't go through, only that I'm not at my computer or otherwise haven't yet approved it.]

April 9, 2024

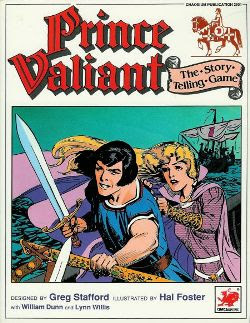

Retrospective: Prince Valiant: The Story Telling Game

When I was kid, I always looked forward to the Sunday edition of the local newspaper, because it had this enormous color comics section. Truly, there were dozens upon dozens of these strips – everything from Peanuts to Garfield to Hagar the Horrible and more. Also present were a number of "old" comics, like Mark Trail, Apartment 3-G, and Mary Worth, whose continued presence baffled me. Who read these comics? Certainly not I, nor any of my childhood friends.

When I was kid, I always looked forward to the Sunday edition of the local newspaper, because it had this enormous color comics section. Truly, there were dozens upon dozens of these strips – everything from Peanuts to Garfield to Hagar the Horrible and more. Also present were a number of "old" comics, like Mark Trail, Apartment 3-G, and Mary Worth, whose continued presence baffled me. Who read these comics? Certainly not I, nor any of my childhood friends. However, there was one "old" comic that I often did read: Prince Valiant. I did so partly because of the comic's subject matter, Prince Valiant was set, as its subtitle proclaimed, "in the days of King Arthur" and I had long been a devoted fan of Arthurian legendry. Furthermore, Prince Valiant was beautifully drawn and had a very – to me – strange presentation. There were no speech balloons or visual onomatopoeia, just lots of text arranged like storybook.

I was never a consistent reader of Prince Valiant, but, when I did take the time to do so, I almost always enjoyed it. There was a sincerity to the comic that I appreciated as a youngster, as well as an infectious love of heroism and romance (in all senses of the term). I wouldn't say that Prince Valiant played a huge role in my subsequent fondness for tales of fantastic adventure, but there's no doubt that it played some role, hence why I took an interest in Greg Stafford's 1989 roleplaying game adaptation when it was released.

Stafford is probably best known as the man behind Glorantha, the setting of RuneQuest. For me, though, Pendragon will always be his magnum opus – and one of the few RPGs I consider "perfect." Consequently, when I eventually learned of the existence of this game, I was intensely interested. How would it differ from Pendragon? What specifically did it bring to the table that justified its existence as a separate game rather than, say, a supplement to Pendragon? These are questions whose answers I wouldn't learn for quite some time. 1989 was something of a tumultuous year for me; I was busy with other things, and it'd only be sometime in the mid-1990s that I would finally lay eyes upon Prince Valiant.

The most obvious way that Prince Valiant differs from Pendragon is revealed in its subtitle: "The Story-Telling Game." Now, some might immediately think that, in this instance, "storytelling" is simply a synonym for "roleplaying" and you'd be (mostly) right – sorta. The important thing to bear in mind is that Prince Valiant is intended as an introductory game for newcomers to this hobby of ours. Consequently, Stafford tries to use common sense words and concepts that aren't rooted in pre-1974 miniatures wargaming culture. Hence, he talks about "storytelling" rather than "roleplaying" and "episodes" rather than "adventures" or "scenarios" and so forth. The result is a game that's written in a simpler, less jargon-laden way than was typical of RPGs at the time (or even today).

At the same time, Stafford's use of the term "storytelling" isn't simply a matter of avoiding cant. Prince Valiant is, compared to most other similar games, intentionally very simple in its rules structure, so that players can focus on the cooperative building of a compelling narrative set in Hal Foster's Arthurian world. Additionally, the game provides the option of allowing even players to take over the story-telling role within an episode, setting a new scene or introducing a new character or challenge. The chief storyteller, which is to say, the referee in traditional RPGs, is encouraged not to ignore these player-inserted story elements but instead to run with them, using them as a way to introduce unexpected twists and turns within the larger unfolding narrative.

The other clear way that Prince Valiant differs from Pendragon is its rules, which can fit on a single page. This makes them easy to learn and remember, as well as to use. Unlike more traditional RPGs with their assortment of funny-shaped dice, Stafford opted in Prince Valiant to use only coins. For any action where the result is not foregone, a number of coins are flipped, with heads representing successes. The more heads flipped, the better the success. In cases where a character competes against another character, such as combat, successes are compared, with the character achieving the most successes emerging victorious – simplicity itself!

Last but certainly not least, Prince Valiant differs from Pendragon because of the pages upon pages of beautiful artwork derived from the comic. Not only does this give the game its own distinctive look, it also highlights its adventuresome, Saturday matinee serial tone in contrast to the heavier, occasionally darker tone of Pendragon and the myth cycles on which it drew. That's not to say Prince Valiant is unserious or "for kids," only that it's a fair bit "lighter" than its "big brother" and thus probably more suitable for younger and/or less experienced players. In that respect, it makes an excellent first RPG.

It's worth noting, too, that the bulk of Prince Valiant's 128-page rulebook is made up not of game mechanics but of advice and tools for players and storytellers alike. Stafford quite obviously distilled the lessons he learned from his many years of playing and refereeing roleplaying games, presenting them in a conversational, easy-to-understand way. Indeed, I've met many people over the years who've claimed that Prince Valiant's true value is not so much as a game in its own right, despite their affection for it, but as an introduction to roleplaying. True though this is, it's also undeniably an excellent game that I'd love to play some day.

That's right: I have never played Prince Valiant and am not sure I ever will. The copy I read years ago was owned by someone else and I've never found a used copy at a reasonable price. I recall that there was an updated or revised version published a few years ago. It doesn't appear to be available through the Chaosium website, alas. Mind you, I certainly don't lack for good RPGs to play; it'd just be great to give this classic one a whirl one day.

April 8, 2024

Polyhedron: Issue #21

Issue #21 of Polyhedron (January 1985) features a cover illustration by Timothy Truman, who produced a lot of artwork for TSR throughout the 1980s before going on to greater success as a comic book artist. The piece depicts the protagonist of this issue's "Encounters" article, facing off against a creature of para-elemental ice, but, as I'll explain shortly, I have some questions.

Issue #21 of Polyhedron (January 1985) features a cover illustration by Timothy Truman, who produced a lot of artwork for TSR throughout the 1980s before going on to greater success as a comic book artist. The piece depicts the protagonist of this issue's "Encounters" article, facing off against a creature of para-elemental ice, but, as I'll explain shortly, I have some questions.

The issue starts with another "Notes from HQ" article by Penny Petticord. Her position is RPGA Network Coordinator, which I assume is the title of the head of the RPGA. However, starting with issue #22, Petticord will also be the editor of Polyhedron, taking over from Mary Kirchoff, who'd been on the staff of the newszine since issue #5. She would then devote herself full-time to fiction, writing numerous Dragonlance novels and later becoming part of TSR's book publishing division.

Next up is the aforementioned "Encounters" article by James M. Ward. The scenario sees a young paladin named Ren Grakkan on a quest to retrieve "the most potent of all artifacts," the white cloak of enchanting (or is it charming? The text is inconsistent) for his unnamed lady love. The cloak is found in a cave guarded by para-elemental ice monsters. As I noted, I have a couple of questions. First, Ren is described as a paladin, but he looks more like a classic sword-and-sorcery barbarian based on Truman's illustration. The text at least supports this, since he's described as wearing no armor but only bracers of defense (AC 4) and having Dexterity 18 (hence a –4 defensive adjustment). Even so, he looks nothing like what I'd expect of a "paladin," but perhaps I simply lack imagination. (I suppose it's possible the artwork depicts the cloak's original owner, a barbarian lord, who lost it in battle against the ice creatures, but then why isn't the cloak shown?) Second, this so-called "potent artifact" Ren is seeking makes its wearer's charm and illusion spells harder to resist, especially if the wearer is female. Could it be that Ren's "lady love" is actually a sorceresss who's charmed him? There's no evidence of this in the text, but the thought occurs to me. (Also, why does Ward keep re-using the name "Ren" for his characters?)

Sonny Scott's "Observations from a Veteran Gamer" is short piece of fluffy advice from a long-time player of AD&D who's also a stalwart of the RPGA. I don't mean to be so dismissive, but there's nothing here you've never heard a thousand times before. More interesting is Gary Gygax's "Why Gargoyles Don't Have Wings But Should." The article begins with classic Gygaxian boasting: he speaks of his association with Flint Dille ("Did you know his grandfather invented Buck Rogers?") and their upcoming joint projects. Then, he moves on to his dissatisfaction with depictions of both the gargoyle and the mar(l)goyle from Monster Manual II. The illustrations for both, Gygax says, lack wings and this should be corrected in "some future edition" of AD&D. For reference, here are the two illustrations in question:

"Don't try to tell me those dark shadows are wings!" Thus spake Gygax.

"Don't try to tell me those dark shadows are wings!" Thus spake Gygax. Gygax also explains that the second monster's proper name is marlgoyle, with an "l," just as it's named in The Lost Caverns of Tsojcanth. This is one of those cases where, if one knows anything about geology, the error is obvious. In any case, I find this sort of thing fascinating – all the more so because the error was never corrected in any subsequent edition of the game.

Gygax also explains that the second monster's proper name is marlgoyle, with an "l," just as it's named in The Lost Caverns of Tsojcanth. This is one of those cases where, if one knows anything about geology, the error is obvious. In any case, I find this sort of thing fascinating – all the more so because the error was never corrected in any subsequent edition of the game. Roger E. Moore's "Take Command of a Titan!" is, by far and away, the best part of this issue and indeed one of my favorite articles ever to appear in any gaming periodical, not simply Polyhedron. In it, Moore lays the groundwork for a "Big Ship" campaign in Star Frontiers. By "big ship," he means a space vessel whose crew numbers in the hundreds at least, if not more. This is territory well covered by both Traveller and Star Trek, but it's not really discussed in Star Frontiers. Additionally, Moore provides lots of ideas on what makes a Big Ship campaign unique and fun. Back in my youth, this article, along with its sequel in the next issue, was a very inspirational one for me. To this day, I find myself longing for a science fiction campaign set aboard a Big Ship.

"Spelling Bee" by Frank Mentzer returns, looking at the ins and outs of a few low-level magic-user spells for AD&D. I'm always of two minds about these kinds of articles. On the one hand, I appreciate seeing the clever ways that people can make use of well-worn spells. On the other hand, some of these clever uses depend on very specific, nitpicky, and possibly tendentious readings of the text. It's a fine line, to be sure, which is why I can't be outright dismissive of articles like this, even as I, as a habitual referee, tend to grit my teeth at some of the more "creative" applications put forward.

"Witchstone" by Carl Sargent is an AD&D adventure for character levels 8–12. It's an odd adventure, because, at base, it's pretty mundane: a bunch of hill giants are causing trouble and it's up to the PCs to deal with them. However, the reason why the giants are more hostile than usual concerns a power play by a giantess wishing to make her son chief. This she does by trickery, pretending she is a witch and arranging for "accidents" to occur that support her false claim. It's certainly interesting in an abstract sense, but I'm not sure how much of this would be communicated to the characters involved in the adventure.

"Five New NPCs" is just what its title suggests: a collection of five non-player characters submitted by RPGA members. None of them are especially memorable. "Module Building from A to Z" by Roger E. Moore is vastly more worthy of attention. In this lengthy, four-page article in which Moore presents the guidelines by which modules submitted to both Dragon and Polyhedron are evaluated. It's a remarkable article for its insight into the culture of TSR in early 1985, as well as into the readership of its periodicals. There are already hints of the "TSR Code of Ethics" that would appear later, for example. The guidelines also allude to the relative popularity of various RPGs at the time, with modules for games like Boot Hill and Gangbusters being excluded "due to low reader interest." There's a lot here to consider; I may need to do a longer post dissecting the whole thing.

I could not bring myself to read "The RPGA Network Tournament Scoring System" – sorry! "Dispel Confusion" covers only three games this month: AD&D, Gamma World, and Top Secret, with AD&D questions taking up slightly more than half of the pages devoted to this section. That shouldn't come as a surprise, but I nevertheless find it notable. What does surprise me is how often the submitted questions amount to "In my campaign, can I do ...?" with the answer usually being, "Yes, if the referee will allow it." What a strange world! This seeking of permission from the publisher is bizarre. I wonder if anyone ever wrote to Parker Brothers to ask about whether it was OK to use Free Parking as something other than an empty space?

Barbarian, Scout, Tomb Robber

Initially, I modeled the character classes of Secrets of sha-Arthan on 4+3 structure of Tom Moldvay's D&D Basic Set, coming up with the following:

Adept: An analog to the cleric only in as much as it's a second "caster" class.Chenot: A non-human class occupying a similar niche to the halfling.Ga'andrin: An analog to the dwarf – a "tough" non-human class.Jalaka: A non-human class that combines combat and sorcery – elf analog.Scion: An analog to the thief only in as much as it's a "skill" based class but focusing more on social situations.Sorcerer: Obviously, an analog to the magic-user.Warrior: Fighter.I was quite happy with this arrangement, because it kept the number of classes down to a manageable number and (for the most part) the classes were all distinct from one another. However, as I've developed sha-Arthan, both through preliminary playtesting and my own evolving sense of the setting as a place, I've come to realize the need for some additional classes – or at least I am seriously considering adding them.The proposed additional classes are:Barbarian: Another "fight-y" class but distinguished in part by its "outcast" status, which is to say, coming from outside the major societies/cultures of sha-Arthan. The purpose of the class is to provide an easy "in" for players who don't want or don't yet feel comfortable playing a character who's part of one of the established cultures of the setting.Scout: Since travel and "hexcrawling" are a big part of Secrets of sha-Arthan (including how secrets are acquired), I felt the need for a class whose niche was exploring (which is why I might use the name "explorer" instead). It's a very broad analog to the ranger class, but with more focus on survival and overcoming terrain hazards, in addition to the usual stuff.Tomb Robber: Despite my alleged hatred of thieves, I nevertheless find myself drawn to (and creating) variants of the class. The Tomb Robber is yet another one, albeit one closer to the traditional D&D thief in terms of its abilities. Given the more "ancient world" of sha-Arthan, I felt like the Tomb Robber makes good sense and has a clear place in the setting.I haven't yet made up my mind about the additional three classes. They'll require further thought and playtesting, but I feel like they all add to the game, as well as the setting. In fact, one of the biggest reasons I like them is that they all – even the barbarian – hook into the setting and kind of gameplay I find enjoyable. The question is whether they bring enough to the table to justify bringing the total number of "basic" classes to 10. (Alternately, I could eliminate the racial classes entirely, leaving seven classes and four races, but that's a much bigger change in my opinion).

Regardless, work on Secrets of sha-Arthan continues. With luck, I might even finish a complete draft before the next total solar eclipse!

Curse the Baggins!

I've long been a defender of amateurish old school art, but even I have limits.

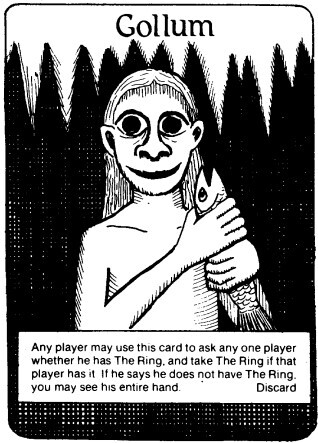

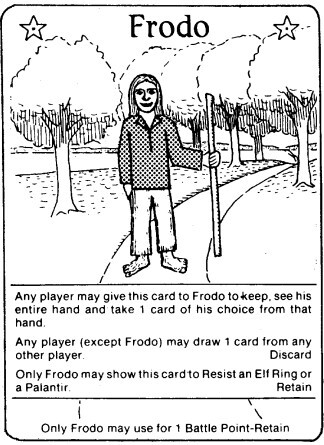

While re-reading some old Dragon magazine issues from the mid-1980s, I came across an advertisement Riddle of the Ring, a Middle-earth boardgame originally released in 1977. The ad mentions that a new edition of the game, from Iron Crown Enterprises, which, at the time, held the Middle-earth license, was in the works. However, a limited number of the original edition was still available from its original publisher, Fellowship Games of Columbia, South Carolina.

The only reason I even paid any attention to this full-page advertisement is that it included examples of the artwork found in the original edition, like this:

Or this:

Or this:

To paraphrase the great philosopher David St. Hubbins, there's a fine line between charming and just bad and I find it difficult to judge either of the examples of Riddle of the Ring's artwork above as anything but the latter. Maybe that's unfair, given the relatively early publication date of this game and the likely limited resources of the publisher. I understand that they're not going to look as awesome as the Brothers Hildebrandt Tolkien calendars of the same era, but, surely, they should be better than this.

To paraphrase the great philosopher David St. Hubbins, there's a fine line between charming and just bad and I find it difficult to judge either of the examples of Riddle of the Ring's artwork above as anything but the latter. Maybe that's unfair, given the relatively early publication date of this game and the likely limited resources of the publisher. I understand that they're not going to look as awesome as the Brothers Hildebrandt Tolkien calendars of the same era, but, surely, they should be better than this.

Am I wrong?

April 7, 2024

Can You Go Home Again?

Despite my preference for playing RPGs with a group of friends, I've long enjoyed video and computer games. In fact, over the past Christmas holiday season, I finally completed Legend of Grimrock, a computer game I bought more than a decade ago and never finished. The premise of Legend of Grimrock is that the your party of four characters have been accused of crimes they (probably) didn't commit and must serve their sentence within the dungeons of Mount Grimrock. If they somehow survive its dangers, they will be absolved of their crimes. Of course, no one has ever escaped Mount Grimrock, so the odds of their doing so are not good.

I had a lot of fun with Legend of Grimrock (and, earlier this year, its sequel). It's a tough, occasionally frustrating dungeon whose challenges are a mix of puzzles, traps, resource management, and, of course, combat. In fact, I had such a good time playing it that I experienced a little bit of sadness when I finished the game. I wanted there to be more and there wasn't, so I naturally set out to find other games that might scratch the same itch. Surprisingly, there weren't a lot of computer or video games out there that had quite what I was looking for – at least not current video games (by which I mean, games released within the last decade or so).

Fortunately, fondness for and appreciation of the products of earlier eras is not limited to the realm of tabletop roleplaying games. Indeed, I suspect there is probably even more nostalgia for old video and computer games, if only because of their greater popularity and reach. In recent years, quite a few publishers have made their older games available once again, after making small updates so that they'll run on modern hardware. That's when the idea struck me: why don't I play one of those older games – go right back to "the source," so to speak? Surely that would help me over my feeling of letdown after completing Legend of Grimrock.

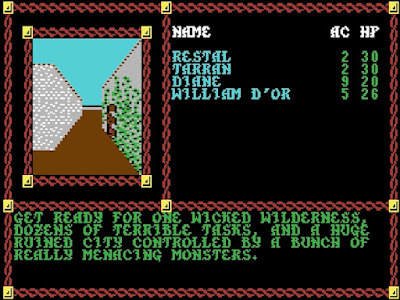

So, I picked up a copy of Pool of Radiance, a computer game for which I have fond memories. Not only was this the first computer game to make use of the Dungeons & Dragons rules, it came out during my time away at college. I never owned the game myself – I didn't yet have a computer, this being 1988 – but a friend of mine did. He kindly let me play it when he was in class and I recall enjoying myself. I never completed the game, so buying it now would give me the opportunity to do so, albeit thirty-six years after the fact.

Regrettably, it looks like I'll probably never finish Pool of Radiance.

The truth is that, for me, the game is too old, both in terms of its content and presentation, for me to enjoy. I suspected this might be the case, since, when I wrote my Retrospective piece back in October 2022, I had the chance to look at lots of screenshots and even the original manual. They reminded me that just how primitive the game is. Now, as an enjoyer of OD&D, there's nothing inherently wrong with primitive and, in fact, there can often be something very enjoyable about it. When it comes to technology, though, the matter is a bit more complicated, since it can be difficult to unlearn what you have already learned.

In the case of Pool of Radiance, its user interface is awkward and clunky, designed for use with computer hardware that no longer exists. Likewise, the graphics are often difficult to read/recognize on a modern computer monitor. That made doing almost anything in the game slow and unintuitive, thereby detracting from my enjoyment. Further, the game design is very tedious and grindy – almost as if the stereotype of old school tabletop RPGs were true! Rather than challenging my wits, the game challenged my patience and I soon found I was unable to play it with any pleasure.

It's a great shame, because I was looking forward to playing Pool of Radiance to its conclusion, after all these years. I wonder if the problems are really with the game itself or with me. It may simply be the case that I've grown so accustomed to the way modern games work that I can't get myself back into the headspace to appreciate older ones. If so, that makes me wonder if something similar might be going on with people who claim they can no longer play older tabletop RPGs. Is this a case where "technology," broadly defined, so alters our mental frames that it inhibits or even impedes our ability to make use of earlier versions of itself? I don't know if this is true, but it's a fascinating thought.

Regardless, I still don't have a good replacement for Legend of Grimrock. Any suggestions?

April 5, 2024

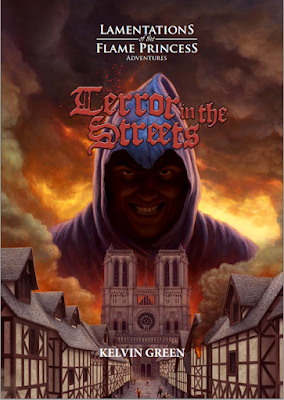

REVIEW: Terror in the Streets

Allow me to say once again, as I always do, that I am a huge fan of historical fantasy. From what I can tell, my fondness for it is unusual, both among RPG players and among RPG writers and broadly for the same reason: the perception that it's hard to get right – especially when there are legions of know-it-all armchair historians out there positively salivating at the possibility of uttering the dread incantation Ackchyually the moment they detect even the slightest deviation from the historical record. Consequently, I don't blame anyone who chooses to shy away from venturing anywhere near real world history in their RPG sessions or products.

Allow me to say once again, as I always do, that I am a huge fan of historical fantasy. From what I can tell, my fondness for it is unusual, both among RPG players and among RPG writers and broadly for the same reason: the perception that it's hard to get right – especially when there are legions of know-it-all armchair historians out there positively salivating at the possibility of uttering the dread incantation Ackchyually the moment they detect even the slightest deviation from the historical record. Consequently, I don't blame anyone who chooses to shy away from venturing anywhere near real world history in their RPG sessions or products.

Nevertheless, I remain deeply grateful to publishers like Lamentations of the Flame Princess and writers like Kelvin Green for their willingness to sate my peculiar tastes for fantastic adventures set in this world's historical past. Terror in the Streets – no, I won't be using the acronym – is a clever, well-presented and, above all, fun example of just how you can use real world history as a backdrop for a fantasy RPG adventure without either getting too bogged down in pointless minutiae or giving that history its proper due. It's not perfect by any means, but Terror in the Streets is very good.

Before proceeding to the meat of this review, I should add that there are, in fact, two different versions of Terror in the Street. The first (and the one I'm reviewing in this post) is a 96-page A5 hardcover book featuring a cover painting by Yannick Bouchard. The second version, entitled Big Terror in the Streets – no, just no – is a boxed set that features a lot of additional goodies, like a map of the city of Paris in 1630, player handouts, cardboard cut-outs, and a large yellow six-sided Unrest Die (for tracking the progress of civil unrest), in addition to an additional book, the 48-page Huguenauts and Other Distractions. Unfortunately, I don't believe Big Terror in the Streets is available in any form any longer, though there may still be copies of it floating around in secondary markets. That's a shame, since Huguenauts and Other Distractions has much to recommend it and indeed provides worthwhile fodder for anyone who continues to worry that historical fantasy is hard to get right. (If I find that the book is available, I'll do a review of it as well.)

Terror in the Streets is a murder mystery set in early 17th century Paris – "Jack the Ripper, but 250 years early," as the author describes it in his introduction. There's a serial killer of children loose in the city and it's up to the player characters to stop him. Just how and indeed why they might do so is an open question, one of many ways that Terror in the Streets might be called a "sandbox" adventure. Other than a timeline that dictates when and where the killer strikes (along with other key events), the course of the adventure is largely determined by the choices of the player characters, as they investigate, interact with NPCs, and deal with random encounters.

This is, in my opinion, the only way to structure a murder mystery adventure without resorting to a more heavy-handed approach. Yes, this structure carries with it the risk that the characters might get lost in the weeds, wasting too much time on red herrings – of which there are quite a few in Terror in the Streets – and other irrelevant complications. However, the advantage of this more open-ended structure is that it's much more forgiving to the referee trying to keep track of all the moving parts that make up the scenario. Plus, the timeline, which exists independently of character actions, serves as a useful way to nudge their attention back toward more pressing matters. And there are even guidelines for what might happen if the characters fail to stop the killer, which is quite refreshing.

While the murder mystery scenario is a genuinely compelling one that nicely leverages multiple aspects of real world history, like the tensions between political and religious factions within Paris, it's not the only appealing thing about Terror in the Streets. Equally interesting in my opinion is its presentation of 17th century Paris – its districts, landmarks, taxi service companies, encounters, and, above all, unique NPCs – in effect a mini-gazetteer of the city. Taken together, these elements give the referee everything he needs to keep the characters engaged while in Paris, not just for this adventure but for others as well. It's nicely done and, reading through it, I found myself wishing that LotFP produced more material like this in the future.

The only aspect of Terror in the Streets that might be considered a flaw is Green's humor-laden conversational style of writing. This is not a book whose author takes himself or the material too seriously. Consequently, there are asides, digressions, and meta-commentary scattered throughout, usually to good effect. Green is quite open about his inspirations and the shortcomings/limitations of the adventure, which is genuinely refreshing and indeed helpful. However, there are also occasional moments of goofiness and sly winks at the reader, like a mad wizard with wild hair and a beard named Alain de la Mare. These don't necessarily detract from the scenario, but I can easily some players and referees finding them off-putting, particularly those who prefer their historical fantasies straight. For myself, I found most of these elements amusing and felt they nicely demonstrated that there's no reason a historical scenario need be unduly solemn.

In the end, though, this is a small thing and Terror in the Streets is one of the best things Kelvin Green has written for LotFP to date. It's also one of the best historical fantasy adventures I've read in quite some time. Reading it, I was left with a small sense of disappointment that I am not refereeing a game where I could easily make use of it. Terror in the Streets is a well written, well presented scenario that is probably a lot of fun to play. I can think of no better compliment.

Favorites

I've asked this question elsewhere, but it's worth throwing open to a larger audience: which Grognardia posts do you consider your favorites? Alternately: which posts, irrespective of your liking for them, do you consider essential?

I ask because I've long considered the possibility of putting together an anthology or digest of Grognardia containing only my best and most significant posts. However, I'm not always the best judge of this sort of thing and can always benefit from others' perspective.

Feel free to post your picks in the comments or, if you'd prefer, send them to me directly via email address included on the "About Me" tab. Thanks in advance!

April 4, 2024

"Are We the Baddies?"

The House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign continues on each week, as it has for the last nine years. One of the things I most enjoy about it are the many opportunities it affords us to explore a fantasy setting that is quite unlike both the real world and commonplace vanilla fantasy settings. This is especially fun for me when the player characters act in ways that are perfectly consonant with the principles of Tékumel but nevertheless surprise their players. This happened in our most recent session and I thought what happened might be worth sharing.

The House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign continues on each week, as it has for the last nine years. One of the things I most enjoy about it are the many opportunities it affords us to explore a fantasy setting that is quite unlike both the real world and commonplace vanilla fantasy settings. This is especially fun for me when the player characters act in ways that are perfectly consonant with the principles of Tékumel but nevertheless surprise their players. This happened in our most recent session and I thought what happened might be worth sharing.To begin, a brief bit of context: the characters, having returned to Tsolyánu after several game years of having served in the administration of the far-off colony of Linyaró, are now in the employ of Prince Rereshqála, one of the potential heirs to the Petal Throne. They've recently begun to first leg of a very long journey that will take them into unknown lands and ultimately end with the exploration of ancient ruins associated with the non-human Mihálli species. Along the way, their ship put in at an island whose governor belongs to the same clan as Nebússa, one of the player characters. The intended purpose of the stopover was resupply and "showing the flag" on behalf of Rereshqála.

However, Nebússa soon became aware of the possibility that something nefarious might be afoot on the island, with the governor at the center of it. An early avenue of investigation suggested that the governor might be skimming an inordinate amount of money from his collection of taxes, perhaps funneling them toward sinister purposes. Notice that I wrote "inordinate amount of money." That adjective is important, especially in Tékumel. That's because, strictly speaking, there's nothing wrong with a little bit of peculation by a provincial governor. Indeed, it's expected and one of the perks of the job. The expectation that a civil servant wouldn't engage in the misappropriation of government funds is an attitude alien to Tékumel. It rises to the level of genuine concern when said civil servant embezzles too much.

Now, the players – and their characters – already know this. After nearly a decade of playing in the setting, they have a very good sense of how things operate in Tsolyánu and elsewhere. They've (largely) put aside their 21st Western morality and approach Tékumel from the point of view of a native. They might still comment upon it as an out-of-character aside – and frequently do, because it can be a source of humor – but none of them really need to be reminded anymore that the social context of Tsolyánu is not that of our world. Things are done differently here and that's that.

As their investigations continued, it soon became clear that the governor they initially suspected of duplicity was, in fact, being set up by someone else and that the strange things occurring on the island had nothing to do with his theft of tax money. They knew this to be the case when, upon examining the governor's books, it was clear he wasn't stealing enough. Sure, he was embezzling, but he wasn't embezzling as much as they would be in his position. Indeed, they soon came to the conclusion that he was basically honest but incompetent and that someone else was probably behind certain events on the island.

They were right. A political rival on a nearby island was responsible for much of what was happening. When they confronted her, she admitted as much without any artifice. The characters that she was so open and honest, but she explained that this was simply politics and no concern of theirs. Initially, they objected, claiming her actions undermined the Empire and that, therefore, they had no choice to become involved. She reiterated that her goal was strengthening Tsolyánu through the elimination of a weak rival and, once again, that this was none of their concern. She then offered to buy them off. What would it take for them to stop interfering, leave, and never return?

At first, the players weren't sure how to respond. As they struggled with everything the rival had said to them, they realized they'd been approaching this not as Tsolyáni, which is to say, as subjects of a fantasy empire with a very different worldview, but as 21st century men offended by political corruption. Soon, though, their perspective began to change; the offer held more and more appeal. A few rounds of negotiation and they had managed to obtain a fair bit of magical and monetary assistance in exchange for their silence. A deal had been struck and they were on their way, prompting one of the players to ask, "Are we the baddies?"

The session was a terrific one. Everyone involved had a lot of fun and laughed at what had ultimately transpired. I personally found it enjoyable, because I got to present Tékumel as a "real" place that operates according to its own rules, ones that are frequently at odds with those of our world. To me, that's one of the best and most vital parts of roleplaying: being able, if only for a while, to be transported to another place and to see that place through alien eyes. I wouldn't want to live on Tékumel, but it is an interesting place to visit.

April 3, 2024

Why Women Don't Play Wargames

Roger E. Moore's article in issue #20 of Polyhedron about "Women in Role Playing" reminded me of this ad that I first saw on Jon Peterson's blog. According to Jon, it first appeared in the June 1977 issue of Fantastic, a Ziff Davis pulp magazine founded by Howard Browne (a protégé of Ray Palmer).

I don't have a lot to say about this particular topic beyond relating to you my own limited experiences. I started playing RPGs in late 1979 with my neighborhood friends and classmates. Not one of them was female, but that's hardly surprising, given my age. I recall encountering a very small number of girls and women who played roleplaying games at the local games days organized by public libraries to which I'd sometimes go. When I went to college in the late '80s, I likewise encountered a handful of women who gamed, but, as in my childhood and teen years, they were unusual. I don't think I started to see female roleplayers in any number until the 1990s, thanks in no small part to White Wolf's World of Darkness games, particularly Vampire: The Masquerade.

I don't have a lot to say about this particular topic beyond relating to you my own limited experiences. I started playing RPGs in late 1979 with my neighborhood friends and classmates. Not one of them was female, but that's hardly surprising, given my age. I recall encountering a very small number of girls and women who played roleplaying games at the local games days organized by public libraries to which I'd sometimes go. When I went to college in the late '80s, I likewise encountered a handful of women who gamed, but, as in my childhood and teen years, they were unusual. I don't think I started to see female roleplayers in any number until the 1990s, thanks in no small part to White Wolf's World of Darkness games, particularly Vampire: The Masquerade.

Obviously, girls and women are much less rare in the hobby nowadays than they used to be, though I'd still wager they're a minority overall. For example, my adult daughter has gamed with her friends since high school; most of them are men. I won't make any claims to how representative any of this with the hobby as a whole, of course, but it's all I've got when it comes to this question (which, I'll be honest, isn't something that occupies my thoughts all that much).

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers