James Maliszewski's Blog, page 60

April 2, 2024

Retrospective: The Complete Fighter's Handbook

AD&D 2nd Edition catches a lot of flak among old schoolers and I completely understand why that is. Nevertheless, as I've stated before, I don't think it's nearly as bad as its somewhat exaggerated reputation would suggest. I played 2e happily for many years and have fond memories of the adventures and campaigns in which I participated. For that matter, I probably wouldn't hesitate to play 2e again if someone I knew were starting up a new campaign using those rules. In short, I think 2nd Edition is just fine, even if it's not my preferred version of Dungeons & Dragons.

AD&D 2nd Edition catches a lot of flak among old schoolers and I completely understand why that is. Nevertheless, as I've stated before, I don't think it's nearly as bad as its somewhat exaggerated reputation would suggest. I played 2e happily for many years and have fond memories of the adventures and campaigns in which I participated. For that matter, I probably wouldn't hesitate to play 2e again if someone I knew were starting up a new campaign using those rules. In short, I think 2nd Edition is just fine, even if it's not my preferred version of Dungeons & Dragons.

That's not to say 2e is not without problems – or, at least, that the larger 2e game line is not without problems and big ones at that. One of the biggest can be seen in its inordinate fondness for bloated (and frequently mechanically dubious) supplements, like 1989's The Complete Fighter's Handbook by Aaron Allston. This was the book that launched a thousand supplements, inaugurating not just the "PHBR" series, which would eventually include fifteen different volumes, but also the "DMGR" (9 volumes) and the "HR" (7 volumes) series as well. These supplements were of varying quality and entirely optional, but, as is so often the case, their mere existence placed a lot of pressure on referees to allow their use in their campaigns, often with disastrous results.At 124 pages in length, The Complete Fighter's Handbook is an eclectic mix of new and optional rules for use by players of the fighter class and by Dungeon Masters wishing to include additional levels of details with regards to armor, weapons, combat, and related topics. In principle, it's not a bad idea for a supplement, akin in some respects to Traveller's Mercenary , both in terms of its content and the way that its publication changed the game forever. Once The Complete Fighter's Handbook was published, it was inevitable that there'd eventually be Complete Handbooks for every class and race in the game, each one adding further complexity and ever greater demands on the referee.

The book begins with a lengthy, eight-page treatment of armor and weapon smithing in the context of 2e's non-weapon proficiency system. On the one hand, that's a genuinely useful and even interesting subject for players and referees who want that level of detail in their campaign. On the other, it's also a lot of new rules material that most players and referees simply won't want. Ultimately, that's the paradox of this book: there's some good stuff in here, but I'm not sure the juice is worth the squeeze. It's also, as I've said, the first step on the supplement treadmill that would come to characterize AD&D 2nd Edition – not to mention undermining the edition's very raison d'être of making AD&D clearer, simpler, and more accessible. Alas, the need to keep selling books trumps all.

Next up are 24 pages devoted to 14 different "kits," a concept first introduced in Time of the Dragon , along with guidelines for modifying the kits or creating one's own. Unlike the kits from Time of Dragon, those presented here are mostly rather "generic" – gladiator, peasant hero, pirate, etc. – rather than being immersed in a specific cultural or social context. This is the same problem that would later befall 3e's prestige classes and probably for the same reason: it's harder to sell game material that is tied to a specific setting than it is to sell material usable by anyone who pays their $15.

Then there's a similarly long section devoted to "roleplaying" that is a mixture of the banal ("warrior personalities"), the basic (campaign structure), and the half-interesting ("one-warrior type campaigns"). In many ways, this section exemplifies the Complete Handbook series as a whole: an overwritten mix of good and bad, with much of it unnecessary. The remaining half of the book is like this, too – lots of rules options relating to weapon proficiencies, combat, and equipment, mixed up with occasional bits of advice regarding their implementation. There's simply so much of it that I shudder at the thought of any referee making use of more than just a tiny percentage, because I imagine the effects of using more than that in a campaign would be confusion at best and catastrophe at worst.

That, ultimately, is my primary criticism of The Complete Fighter's Handbook and the books it inspired: it's too much and to little good end. There are a few good ideas scattered throughout but finding them is like looking for a diamond among a mountain of coal. Worse, as I've said, is the way that this book laid the groundwork for a new philosophy not just of play but of publishing that would hobble AD&D 2nd Edition until its – and TSR's – demise. I genuinely wish that weren't the case, because I think there's the germ of a good idea behind this book, but it's buried under so much dross that I find it hard to render a positive judgment in the end – a pity!

Popularity (Part II)

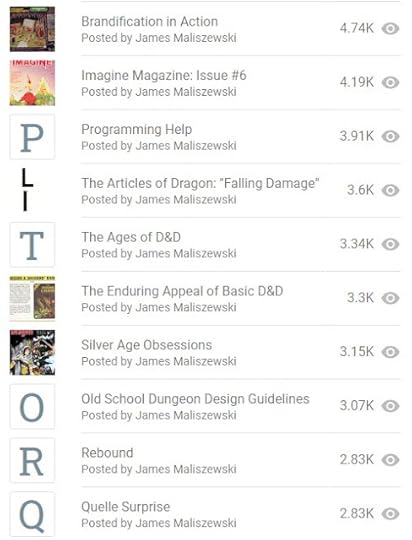

Here are the eleventh through twentieth most popular posts on Grognardia for comparison to the Top 10:

That's quite a different batch of posts and (mostly) a pretty good reflection of what I think of this blog as being about.Brandification in Action is a good post and its subject matter is one to which I return again and again. Indeed, it's one I intend to discuss more soon.Imagine Magazine: Issue #6 only ranks so high because it was the final post of the first iteration of Grognardia. For nearly eight years, it was the first thing anyone would see upon visiting the blog. Frankly, it's a wonder it didn't rack up more pageviews. Programming Help is another post of no consequence whose pageviews are almost certainly are an accident of key words.The Articles of Dragon: "Falling Damage" is a genuinely interesting mix of gaming history and theory and is very much the kind of thing that I like.The Ages of D&D is a worthy and significant post. I might quibble with some of what I wrote back in 2009, but the general thrust of it still seems sound.The Enduring Appeal of Basic D&D raises a very real point on which I think I ought to expand one day. A solid post.Silver Age Obsessions is a favorite of mine and, apparently, others as well. I like it because it not only makes good use of the schema of "The Age of D&D," but does a good job of illustrating some of the very real differences between the game's proposed eras.Old School Dungeon Design Guidelines is a good and useful post. It's also a relic from the days when there was a lot more interplay between blogs and forums. Rebound represents one of the few posts on this blog to talk, even allusively, about 5e, which might explain its popularity. That said, it was written before we knew much about the game, so my points are very abstract. I certainly wouldn't have chosen it as a Top 20 post, but I'm just the writer of this blog. What do I know?Quelle Surprise being on this list is probably an artifact of the past anticipation for the 2011 Conan the Barbarian movie rather than a reflection of anything else.Looking over entries 1 through 20 in terms of pageviews doesn't provide me with much clarity about just which posts will prove popular and which ones will not, since it's an incredibly eclectic mix. However, seeing them all has at least given me a better sense of what I consider my best posts. Perhaps I can use that insight as I continue to contemplate how best to continue writing this blog in the years to come.

April 1, 2024

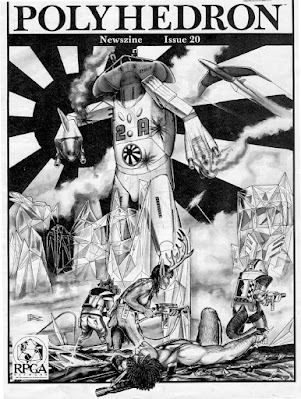

Polyhedron: Issue #20

Issue #20 of Polyhedron (November 1984) is another with which I am very familiar. Regular readers should also remember it from another post I wrote almost a year ago. The cover, by Roger Raupp, depicting the events of this issue's "Encounters" article, is a big part of the reason why it made such an impression on me as a teenager. I'll have a little more to say about it shortly.

Issue #20 of Polyhedron (November 1984) is another with which I am very familiar. Regular readers should also remember it from another post I wrote almost a year ago. The cover, by Roger Raupp, depicting the events of this issue's "Encounters" article, is a big part of the reason why it made such an impression on me as a teenager. I'll have a little more to say about it shortly."Notes from HQ" is a good reminder that, whatever else it may have been, Polyhedron was supposed to be the official news organ of the RPGA. Consequently, the article focuses on the most recent GenCon and the events run there on behalf of the Role Playing Game Association. While most of the information it conveys is ephemera – "Due to a computer mixup, our events didn't make it into the pre-registration brochure ..." – I nevertheless found the titles of some of the RPGA events fascinating. For example, there was "Baron of San Andreas" for Boot Hill , "Seventh Seal" for Top Secret , and "Rapture of the Deep" (or "Face of the Anemone") for Gamma World. It's all quite evocative and makes me wish I knew more about them.

Speaking of Gamma World, there's another installment of James M. Ward's "Cryptic Alliance of the Bi-Month," this time devoted to the Healers. To date, most of the entries in this series have been, in my opinion, vague on details and generally limited in utility. Some, however, get by because the cryptic alliance covered is sufficiently interesting in its own right, like, say, the Knights of Genetic Purity, Sadly, the same cannot be said of the Healers, who come across as very generic peaceniks without much in the way of adventure hooks that might convince a referee to include them. Also, like too many of the cryptic alliances in this series, the Healers' own legends include too many sly jokes and references to 20th century pop culture ("Lue of the Sky" and "Bencassy"), but then that's a common problem with the presentation of Gamma World's setting and not unique to them.

Kim Eastland's "The Proton Beam" describes a new form of weapons technology for use with Star Frontiers , along with defenses against it. I've always had conflicted feelings about the fixation sci-fi games have with an ever-expanding equipment list, so I tend to greet articles like this with some skepticism. In this case, though, I appreciate that Eastland use the introduction of the proton beam into an existing Star Frontiers campaign as an occasion for adventure. He suggests several possible ways the new weapon could debut, each of which has the potential to send the campaign in different directions. To my mind, that's how new equipment/technology ought to be handled.James M. Ward returns with "The Druid," a two-page article describing Thorn Greenwood, a druid NPC, in some detail. This is part of an irregular series begun back in issue #17, in which Ward presents an archetypal example of an AD&D character class as an aid/inspiration to players and referees alike. Accompanying the article is another page in which RPGA members have submitted their own shorter examples of members of the class. It's an interesting idea, but I'm not convinced it's quite as useful as Ward might have intended.

"The 384th Incarnation of Bigby's Tomb" is a very high-level (15–25) AD&D tournament adventure by Frank Mentzer. Despite its title, the scenario does not seem to have anything to do with either Gary Gygax's character Bigby nor with The World of Greyhawk. The titular Bigby would seem simply to be a generic archmage, though artist Roger Raupp seems to have taken some inspiration from Gygax's actual appearance in depicting him:

The premise of the adventure is that Bigby labors under a curse that makes him unable to employ potions of longevity and thereby extend his life. Rather than die, he placed himself in suspended animation within an artifact, where he would rest until brave adventures might find him, lift the curse, and deliver to him the desired potion. The dungeon surrounding the artifact is not really a tomb, since Bigby isn't dead, but it is a deadly place filled with lots of tricks, traps, and challenges, just as you'd expect of a good tournament dungeon.

The premise of the adventure is that Bigby labors under a curse that makes him unable to employ potions of longevity and thereby extend his life. Rather than die, he placed himself in suspended animation within an artifact, where he would rest until brave adventures might find him, lift the curse, and deliver to him the desired potion. The dungeon surrounding the artifact is not really a tomb, since Bigby isn't dead, but it is a deadly place filled with lots of tricks, traps, and challenges, just as you'd expect of a good tournament dungeon."Encounters," yet another piece by James M. Ward, features the Aquabot for Gamma World, about which I've written before, as I noted above. In my youth, I remember finding the article somewhat jarring, because, up until this point, the setting of Gamma World had never included anything like this in any of its previous supplementary material and I didn't quite know what to make of it. Years later, I'm still not sure, but there's no denying that it made an impression on me, so I suppose it achieved its purpose.

The antepenultimate section of this issue is a doozy: Roger E. Moore's three-page essay on "Women in Role Playing." The article is a very well-intentioned and reasonably thoughtful attempt to broach a number of topics relating to the entry of more women into the overwhelmingly male dominated hobby of roleplaying. While I suspect that many readers today, male or female, might detect the occasional air of condescension in Moore's prose, I think that's probably the wrong lens through which to view this piece. TSR, to its credit, was always quite keen to expand the hobby beyond its traditional male fanbase and articles like this suggest, I think, that they were at least partially successful.

Roger Moore returns with "Now That It's Over ...," another report on the most recent GenCon (17 for those who care). Unlike "Notes from HQ," Moore's article focuses not solely on RPGA matters but on the entire con. Consequently, there's some genuinely interesting bits of historical trivia, like the performance of a dramatic reading from the first Dragonlance novel that received "a standing ovation." He also highlights all the new RPGs that appeared that year, like Paranoia, Toon, Ringworld. and Chill , not to mention TSR's own additions, like Marvel Super Heroes and The Advenures of Indiana Jones – quite the banner year for new releases!

Finally, there's "Dispel Confusion," with answers to questions about D&D, AD&D, Gamma World, Gangbusters, Star Frontiers, and Top Secret. Only the AD&D questions have any lasting importance, largely because they're questions put directly to Gary Gygax himself at the latest GenCon. One concerns the appearance of the mythical module T2, whose manuscript Gygax says is now complete, though without committing to a release date. The second monsters that are "pretty useless" and that "are never seen in the modules." Oddly, Gygax replies that "work is being done to update and improve the Fiend Folio," even though the questioner, at least as reported, did not specifically mention that book of monsters. It's well known that Gygax didn't like the Fiend Folio and many of its entries, so perhaps he simply took this question as another opportunity to vent his spleen about it.

Popularity (Part I)

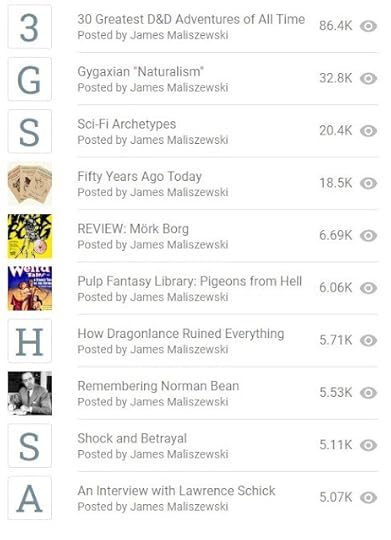

Let's continue to today's theme of navel gazing by taking a look at the most popular posts of this blog by pageview, according to Blogger's own stats. I'd like to see if they reveal anything about what my readers have enjoyed over the years.

By a wide margin, 30 Greatest D&D Adventures of All Time is my most viewed post and understandably so. Its title alone probably ensures that it's one of the top hits in any online search for "greatest D&D adventures" or some variations thereof. From my perspective, it's not an especially great post; I'm not even sure I still hold the same opinions about the modules on the list.By contrast, Gygaxian Naturalism is a good post. This is the origin point for that particular term, which still gets bandied about online after all this time. I couldn't be happier about that.Sci-Fi Archetypes is bizarre to have at the number three spot, yet there it is. It's a trifle of a post that I can only assume owes its place to its title playing well in search engines.Fifty Years Ago Today is on this list because it celebrates D&D's half-centenary and that was a popular point of discussion back in January.REVIEW: Mörk Borg was my first post on this blog after nearly eight years, which is probably enough to explain its popularity. That Mörk Borg was, for a time, the online flavor du jour likely played a role, too.Pulp Fantasy Library: Pigeons from Hell is a decent enough overview of the classic Robert E. Howard horror short story. It's not my favorite, let alone my best, entry in this long-running (and temporarily dormant) feature of Grognardia, but it's solid. Why it's in my Top 10 of popular posts, I could not tell you. Perhaps another algorithmic artifact? How Dragonlance Ruined Everything is a good post and one of my favorites. I'm not surprised it's in the Top 10 and it deserves to be there.Remembering Norman Bean is almost certainly here for algorithmic reasons. I'm not unhappy to see a post of Edgar Rice Burroughs, one of the founding fathers of modern fantasy and, by extension, our hobby, get more attention, but I am surprised it's a Top 10 post.Shock and Betrayal is here for a lot of reasons, including, I suspect, the Internet's love of drama. I'm also likely one of the higher profile fans of Tékumel online, so I suppose it was inevitable that others would be interested in my take on this particular bit of unpleasantness. An Interview with Lawrence Schick is an early interview with a notable figure of the early days of gaming. There's some good stuff in the interview, though it's too short. Why, of all the interviews I've done over the years, it's the only one to reach the Top 10, I have no idea.Looking over the Top 10 posts in terms of pageviews, I don't see much of a discernible pattern, except perhaps the role search engines play in directing traffic on the Internet. Of these ten posts, only a couple – "Gygaxian Naturalism" and "How Dragonlance Ruined Everything" – are really all that representative of my considered thoughts about roleplaying and its history and culture. The rest seem almost random in content; they do very little to help me get a sense of what readers enjoy. However, the next ten most popular posts are, I think, a bit more representative, though, even there, there are some oddities.

By a wide margin, 30 Greatest D&D Adventures of All Time is my most viewed post and understandably so. Its title alone probably ensures that it's one of the top hits in any online search for "greatest D&D adventures" or some variations thereof. From my perspective, it's not an especially great post; I'm not even sure I still hold the same opinions about the modules on the list.By contrast, Gygaxian Naturalism is a good post. This is the origin point for that particular term, which still gets bandied about online after all this time. I couldn't be happier about that.Sci-Fi Archetypes is bizarre to have at the number three spot, yet there it is. It's a trifle of a post that I can only assume owes its place to its title playing well in search engines.Fifty Years Ago Today is on this list because it celebrates D&D's half-centenary and that was a popular point of discussion back in January.REVIEW: Mörk Borg was my first post on this blog after nearly eight years, which is probably enough to explain its popularity. That Mörk Borg was, for a time, the online flavor du jour likely played a role, too.Pulp Fantasy Library: Pigeons from Hell is a decent enough overview of the classic Robert E. Howard horror short story. It's not my favorite, let alone my best, entry in this long-running (and temporarily dormant) feature of Grognardia, but it's solid. Why it's in my Top 10 of popular posts, I could not tell you. Perhaps another algorithmic artifact? How Dragonlance Ruined Everything is a good post and one of my favorites. I'm not surprised it's in the Top 10 and it deserves to be there.Remembering Norman Bean is almost certainly here for algorithmic reasons. I'm not unhappy to see a post of Edgar Rice Burroughs, one of the founding fathers of modern fantasy and, by extension, our hobby, get more attention, but I am surprised it's a Top 10 post.Shock and Betrayal is here for a lot of reasons, including, I suspect, the Internet's love of drama. I'm also likely one of the higher profile fans of Tékumel online, so I suppose it was inevitable that others would be interested in my take on this particular bit of unpleasantness. An Interview with Lawrence Schick is an early interview with a notable figure of the early days of gaming. There's some good stuff in the interview, though it's too short. Why, of all the interviews I've done over the years, it's the only one to reach the Top 10, I have no idea.Looking over the Top 10 posts in terms of pageviews, I don't see much of a discernible pattern, except perhaps the role search engines play in directing traffic on the Internet. Of these ten posts, only a couple – "Gygaxian Naturalism" and "How Dragonlance Ruined Everything" – are really all that representative of my considered thoughts about roleplaying and its history and culture. The rest seem almost random in content; they do very little to help me get a sense of what readers enjoy. However, the next ten most popular posts are, I think, a bit more representative, though, even there, there are some oddities. I'll take a look at this second tier of popular posts tomorrow.

March 31, 2024

Whither Grognardia?

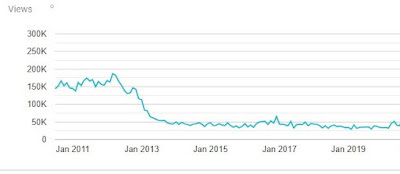

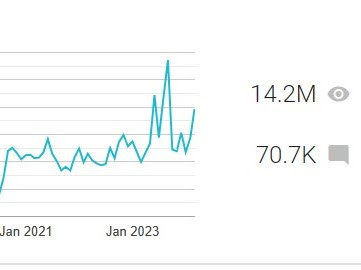

Over the past holiday weekend, Grognardia celebrated its sixteenth anniversary – or, rather, the sixteenth anniversary of the first post to appear here. Now, in truth, I've only posted at this blog for about half that time, owing to my hiatus between December 2012 and August 2020. On the other hand, I never took the blog down and it continued to have a fairly steady, if significantly decreased, readership even during those nearly eight years when I wasn't posting. Take a look at what I mean:

That's a screenshot of Blogger's own Stats page, illustrating Grognardia's pageviews over time, during the period between June 2011 and July 2020. I don't know why the stats only go back to 2011 rather than earlier, but that's all I've got to work with. As you can see, during the 2011 to 2012 period, the two-year period I was posting regularly before my long break, the blog was averaging about 160,000 pageviews per month, with a high of 186,933 for February 2012. After the break, that dropped to about 45,000 per month, with a high of 65,409 in November 2016.

Here's what's happened since I returned to the blog in August 2020:

During that first month back, the blog received 120,063 pageviews, which is about triple what it'd been receiving during my absence, though still quite a bit below what it'd been getting at its height eight years prior. Since then, as you can see, pageviews have fluctuated from month to month, but generally stayed around the 130,000 range. Then, in May 2023, views inexplicably spiked to 221,901 before dropping down to 144,281 the next month and then spiking upward again, eventually reaching an all-time high of 286,230 in August of that year. While I've never again seen anything close to that number of pageviews, the overall number seems to be slowly on the rise, averaging around 140,000 for most months (though March 2024 was just shy of 200,000).

During that first month back, the blog received 120,063 pageviews, which is about triple what it'd been receiving during my absence, though still quite a bit below what it'd been getting at its height eight years prior. Since then, as you can see, pageviews have fluctuated from month to month, but generally stayed around the 130,000 range. Then, in May 2023, views inexplicably spiked to 221,901 before dropping down to 144,281 the next month and then spiking upward again, eventually reaching an all-time high of 286,230 in August of that year. While I've never again seen anything close to that number of pageviews, the overall number seems to be slowly on the rise, averaging around 140,000 for most months (though March 2024 was just shy of 200,000).I bring all this up not merely to boast, but as background to the real point of this post, namely, what to do with this blog. When I began it in March 2008, I had absolutely no idea what I was doing or where it'd go. Owing as much to fortunate happenstance as to any skill on my part, Grognardia took off, becoming one of the major blogs of the burgeoning Old School Renaissance. Indeed, the blog received so much attention that I often felt as if I'd lost control of it, which, like a runaway freight train, was soon careening wildly under its own momentum.

I often joke – not without some degree of truth – that the fist iteration of Grognardia was my mid-life crisis. The blog sprang from an unthinking impulse on my part, one born of my increasing dissatisfaction with the direction of Dungeons & Dragons in the dying days of the 3e era. Giving in to that impulse yielded great joy but also great disappointment, failure, and embarrassment. The present iteration of Grognardia came about when, in the depths of the pandemic lockdowns, I felt I needed a public outlet for expressing myself again. After considering all manner of other alternatives, I finally settled on posting here again, though not without some trepidation.

Though born of different motive, this second version of Grognardia is every bit as directionless as the first. Most days, I write about whatever happens to come to mind rather than proceeding according to some definite plan. The downside of this is that "whatever happens to come to mind" is often a topic I've already covered before. After about 4200 posts and more than 70,000 comments, what haven't I already written about? Indeed, what more do I have to say about anything? I sometimes feel as if I'm competing against an earlier version of myself, a younger more energetic version whose combination of enthusiasm and naivete provides him with more interesting fodder for thoughtful posts.

And yet, for all my frustrations, people keep reading, as the stats above demonstrate. They don't comment as much as they used to, nor do my posts seem to generate nearly as much discussion elsewhere (or as much controversy, thank goodness), but they do nevertheless read, for which I am grateful. Still, I sometimes can't help but wish that I got a better sense of engagement with my posts from my readers. This lack, in turn, feeds my feeling that I don't really have anything interesting to say anymore, so why even try?

Some of that perception may be the result of the larger hobby's (not merely its old school sub-grouping) having changed a great deal between 2012 and 2020. When I started Grognardia sixteen years ago, blogs were very important parts of the online ecosystem of discussion. That's not true anymore, or at least it's less true than it once was. Social media and video seem much more significant, neither of which I really use. If so, is there still a place for Grognardia? Or is it, like old school RPGs themselves, a relic of the past?

[ADDENDUM: To be clear: I have no intention of shutting down the blog again, at least not anytime soon. I simply find writing engaging posts a lot harder now than I did years ago and I wonder if the problem lies with me or with changes in the wider world of online RPG discussion.]

March 27, 2024

sha-Arthan Appendix N (Part II)

In Part I of this post, I shared the four authors whose stories and settings have most influenced my development of Secrets of sha-Arthan. In this part, I'd like to share the four roleplaying games I'd single out as having played a similar role.

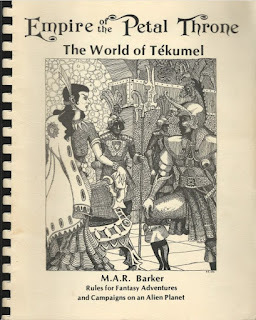

Empire of the Petal Throne: This one should be obvious. The mere fact that I've spent the last nine years refereeing my House of Worms campaign pretty much guaranteed EPT would be included in this list, since it's the RPG I've played the most and most consistently since my youth. However, the game shares so many elements in common with sha-Arthan – secret science fiction, ancient history, baroque societies, weird monsters – that, on some level, it'd be completely accurate to call sha-Arthan "my Tékumel." Of course, sha-Arthan isn't just that, but it owes a huge debt to Tékumel, which is one of my favorite fictional settings of all time.

Empire of the Petal Throne: This one should be obvious. The mere fact that I've spent the last nine years refereeing my House of Worms campaign pretty much guaranteed EPT would be included in this list, since it's the RPG I've played the most and most consistently since my youth. However, the game shares so many elements in common with sha-Arthan – secret science fiction, ancient history, baroque societies, weird monsters – that, on some level, it'd be completely accurate to call sha-Arthan "my Tékumel." Of course, sha-Arthan isn't just that, but it owes a huge debt to Tékumel, which is one of my favorite fictional settings of all time.

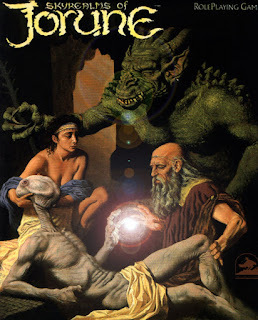

Skyrealms of Jorune: This is another important secret science fiction game and one whose influence over sha-Arthan is important to acknowledge. Though I never owned, let alone played the game when it was first released, I was entranced by the ads for it that ran in the pages of Dragon magazine. Replete with the evocative artwork of Miles Teves, Jorune had a wonderfully exotic setting in the form of the titular planet, where "magic" of a sort is possible, thanks to peculiar physical laws. Likewise, its many unusual – and completely non-terrestrial – intelligent aliens and lifeforms have served as inspirations as I imagined their counterparts on sha-Arthan. Amazing stuff!

Skyrealms of Jorune: This is another important secret science fiction game and one whose influence over sha-Arthan is important to acknowledge. Though I never owned, let alone played the game when it was first released, I was entranced by the ads for it that ran in the pages of Dragon magazine. Replete with the evocative artwork of Miles Teves, Jorune had a wonderfully exotic setting in the form of the titular planet, where "magic" of a sort is possible, thanks to peculiar physical laws. Likewise, its many unusual – and completely non-terrestrial – intelligent aliens and lifeforms have served as inspirations as I imagined their counterparts on sha-Arthan. Amazing stuff!

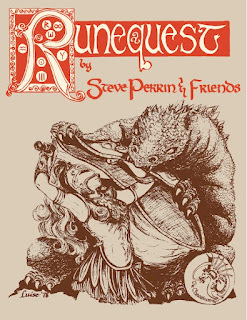

RuneQuest: Right behind Tékumel is Glorantha when it comes to my favorite fictional settings. The main things I took from RQ was its non-medieval, more Bronze Age setting and its emphasis on the importance of culture and religious cults. Indeed, the alignment system of Secrets of sha-Arthan is directly inspired by the cults of Glorantha. I've likewise borrowed a couple of other elements from the game that I thought would fit in well with the setting I was creating for my own game. Beyond that, RuneQuest impresses me with its ability to take itself seriously but not too seriously and that's something that a lesson than an old stick in the mud like me needs to be reminded of often.

RuneQuest: Right behind Tékumel is Glorantha when it comes to my favorite fictional settings. The main things I took from RQ was its non-medieval, more Bronze Age setting and its emphasis on the importance of culture and religious cults. Indeed, the alignment system of Secrets of sha-Arthan is directly inspired by the cults of Glorantha. I've likewise borrowed a couple of other elements from the game that I thought would fit in well with the setting I was creating for my own game. Beyond that, RuneQuest impresses me with its ability to take itself seriously but not too seriously and that's something that a lesson than an old stick in the mud like me needs to be reminded of often.

Bushido: This is another RPG that stresses the importance of culture and religious beliefs and thus inspired me as I developed Secrets of sha-Arthan. While there's not much of feudal Japan's DNA in the True World, there is something of Bushido's rules in my own game, in particular those covering "downtime." Characters in Secrets of sha-Arthan can engage in training, research, intrigue, and social climbing when not traveling or exploring ancient ruins and vaults. The inclusion of these options was inspired by Bushido, which is the first game I recall having rules for these kinds of activities. While other RPGs have subsequently included them, Bushido is the game from which I first learned them.

Bushido: This is another RPG that stresses the importance of culture and religious beliefs and thus inspired me as I developed Secrets of sha-Arthan. While there's not much of feudal Japan's DNA in the True World, there is something of Bushido's rules in my own game, in particular those covering "downtime." Characters in Secrets of sha-Arthan can engage in training, research, intrigue, and social climbing when not traveling or exploring ancient ruins and vaults. The inclusion of these options was inspired by Bushido, which is the first game I recall having rules for these kinds of activities. While other RPGs have subsequently included them, Bushido is the game from which I first learned them.And there you have it: the four roleplaying games whose settings and/or rules influenced me in my own work. As Picasso is reputed to have said, "Good artists borrow; great artists steal." I make no claim to be a great artist, but I thought it only right to let you know from whom I've stolen, if only so that you might be introduced to some really terrific roleplaying games well worth your time.

March 26, 2024

Retrospective: MegaTraveller

Traveller is, without qualification, my favorite roleplaying game and has been since I first encountered it through The Traveller Book in 1982. Over the course of the next four years, I played the heck out of it with both my neighborhood friends and one of my high school classmates. Then, I stopped – or, more precisely, I grew bored with Traveller. Looking back on it now, I suppose it was simply a case of over-saturation. Even more than D&D had been my go-to game for fantasy, Traveller had been my go-to game for science fiction, the end result of which briefly abandoning it for GDW's other SF RPG,

Traveller: 2300

, which came out in 1986. (I would eventually come to feel similarly about Dungeons & Dragons, but not until the mid-90s.)

Traveller is, without qualification, my favorite roleplaying game and has been since I first encountered it through The Traveller Book in 1982. Over the course of the next four years, I played the heck out of it with both my neighborhood friends and one of my high school classmates. Then, I stopped – or, more precisely, I grew bored with Traveller. Looking back on it now, I suppose it was simply a case of over-saturation. Even more than D&D had been my go-to game for fantasy, Traveller had been my go-to game for science fiction, the end result of which briefly abandoning it for GDW's other SF RPG,

Traveller: 2300

, which came out in 1986. (I would eventually come to feel similarly about Dungeons & Dragons, but not until the mid-90s.)My love affair with Traveller: 2300 was comparatively brief, lasting only a couple of years. In only two years of playing it, my passion for the game burnt itself out. Not long thereafter, I discovered that, during my time away from it, GDW had released a new edition of Traveller, bearing the rather unusual (and cumbersome) title of MegaTraveller. This new edition boasted not just revised and expanded rules, but also a change in its official Third Imperium setting – the so-called Rebellion.

A quick aside for context: starting with The Spinward Marches in 1979, GDW slowly built up and developed Traveller's official setting. This setting was originally intended as a loose backdrop for published adventures. Over time, the Third Imperium setting, named for the large, human-dominated interstellar empire at its center, accumulated a wealth of details. This was a big part of its appeal to me and other fans. However, a common complaint about the Third Imperium was that it was too static, a holdover, I suspect, from its origins as a universal framework for a wide variety of campaigns. MegaTraveller's Rebellion – really a war of succession – was an attempt to end that stasis by throwing the Third Imperium into a civil war.

The Rebellion was a major reason why I decided to return to Traveller after my hiatus. I thought the political and military shakeup of the Third Imperium was exactly what was needed to add some dynamism and danger to a setting that felt very staid to me. Consequently, I snapped up MegaTraveller and dove back into the rules and setting I'd loved for many years beforehand. My hope in buying the new edition was that it was similar enough to the earlier edition rules-wise that I wouldn't have to relearn how to play, while also being changed just enough to make it more compelling.

On the first point, I was largely correct. Mechanically, most of MegaTraveller's rules were very close to the 1977/1981 versions I'd played before. Character generation was much as I'd remembered it, though there were a lot more skills and options for advanced generation methods like that found in Mercenary. The combat system borrowed elements from Azhanti High Lightning in an effort to streamline it. More significantly, there was now a codified, universal task system for the handling of both skill use and combat – a major innovation over the ad hoc approach to skills in the previous edition.

At the same time, there were major changes to starships, both their construction and combat systems. Classic Traveller had a simple, elegant system for starship construction. Its combat system was a bit more complex, making use of a realistic vector movement that I always found frustrating. By contrast, MegaTraveller introduced an extensive but unwieldy (and much corrected) construction system that required more or less demanded a spreadsheet to use properly. Its combat system seems to have been modeled on the personal combat system, which is either a positive or a negative depending on how you felt about the original combat system.

Also included in the MegaTraveller boxed set was the Imperial Encyclopedia, which consolidated the two volumes of Library Data under one cover. There was also a map of the Spinward Marches sector. Released around the same time – but sold separately – was the Rebellion Sourcebook. This setting book laid out the various factions of the Imperial civil war for use in the game. Unfortunately, all of the information was very high level and there were no practical details, in this or in the boxed set, on what it was like to referee a campaign during this time of interstellar tumult. Its main utility for me came in the form of its credits, which thanks an organization called The History of the Imperium Working Group (HIWG), whose members were apparently dedicated to working out the details of the Third Imperium setting.

I found HIWG's address in a copy of Challenge magazine and sought them out. They were a collection of Traveller fans dispersed throughout the world who'd been consulted by GDW about the Rebellion and its development. At the time, they were quite active in producing documents about various in-universe topics, which they shared amongst themselves and with Traveller writers. Some of HIWG's members even wrote articles that were published in Challenge and elsewhere. I enthusiastically joined HIWG and used it as a platform to jumpstart my professional writing career. I also made a number of lifelong friends who also shared my passion for Traveller.

MegaTraveller was never a success. Many longtime fans, who'd wanted to see the Third Imperium setting reinvigorated, grew disenchanted with the Rebellion, which seemed both needlessly destructive and aimless. Newcomers were even more confused by what the game was about than they might have been during the latter days of classic Traveller's run. Matters weren't helped by the fact that GDW produced very few support products for the game, leaving most of that work to licensees like Digest Group Publications. The end result was a huge mess – not unlike the Rebellion itself.

Yet, for all of that, I have fond feelings toward MegaTraveller, largely because it served as both my entry into professional writing and because it introduced me to several people who've been very important to me over the years. It probably helps that, for all my protestations to the contrary, I adore setting details and MegaTraveller was an era when such details were at the forefront. From most perspectives, MegaTraveller might not be a great edition of Traveller, but it's one I nevertheless associate with many positive things. That's why it'll always have a special place in my heart.

sha-Arthan Appendix N (Part I)

Last week, I pointed out a "problem" with Gary Gygax's Appendix N, namely, it's just a list without any explanatory apparatus, unlike its counterpart in the original RuneQuest. As I explained in that post, this is far from a damning criticism – Appendix N remains an invaluable guide to excellent fantasy and science fiction stories – but it does limit its utility in trying to understand Gygax's own thought processes as he created both D&D and AD&D.

That's why I decided I'd do things differently in Secrets of sha-Arthan. Rather than simply include a lengthy list of all the books (and games) that had had even the tiniest influence over my own work on SoS, I'd instead present a smaller, more focused list, along with commentary on precisely what I'd taken from each source. The goal is not merely to honor my inspirations, but also to aid anyone who picks up the game in understanding where I'm coming from.

The list, like the game itself, is still in a state of low-level flux. I've purposefully narrowed the list to just four authors, each of which wrote a series of multiple stories within those series. By keeping the list focused on those whose influence is strongest and most clear, I hope that I'll do a better job than Gygax of "showing my cards," creatively speaking. Obviously, other authors and books have inspired me, too, but their inspiration has been more limited. Rather than muddy the waters, I've stuck only with whose influence is most clear.

Burroughs, Edgar Rice: The influence of Edgar Rice Burroughs over the subsequent history of fantasy cannot be underestimated. His Barsoom novels in particular have played a huge role in establishing the broad outlines of that genre and the stories and characters that inhabit it. Everything from building a unique setting, with its own history and geography to populating it with all manner of exotic cultures and beasts to even presenting an alien vocabulary, it's all there in A Princess of Mars, a book not much read today but that I have come to love more the older I get.

Burroughs, Edgar Rice: The influence of Edgar Rice Burroughs over the subsequent history of fantasy cannot be underestimated. His Barsoom novels in particular have played a huge role in establishing the broad outlines of that genre and the stories and characters that inhabit it. Everything from building a unique setting, with its own history and geography to populating it with all manner of exotic cultures and beasts to even presenting an alien vocabulary, it's all there in A Princess of Mars, a book not much read today but that I have come to love more the older I get.In creating sha-Arthan, I often looked to Barsoom and Amtor for inspiration, particularly in my conception of the creatures that dwell upon it. Furthermore, the Ironian language is intended to be reminiscent of the Martian tongue as invented by Burroughs. I also imagine adventures in the True World to be swashbuckling affairs, filled with perilous danger, narrow escapes, and feats of derring-do, just like the delightful novels of ERB.

Smith, Clark Ashton: Of all the writers whose work graced the pages of Weird Tales during the Golden Age of the Pulps, Clark Ashton Smith remains my favorite by far. His examination of the dangers of egotism and the ever-present risk of divine punishment combine with his black humor and imaginative dreamscapes to produce some of the most inventive – and often terrifying – fiction of the first half of the 20th century. Though I am fond of all his story cycles, it's those set in Zothique, Earth's last continent untold eons in the future, that I find most compelling.

There's more than a little of Zothique in sha-Arthan. Its ancient history, selfish sorcerers, and otherworldly daimons are all directly inspired by CAS. Smith's baroque and archaic vocabulary have likewise influenced the nomenclature and general tone of my writing about the setting. Though sha-Arthan is not as dark (or darkly humorous) as Zothique, it does possess some of the latter's world-weariness,

Tierney, Richard L.: Secrets of sha-Arthan takes a lot of inspiration from the late Hellenistic and early Roman eras. That's a period of history that's always fascinated me, so that's no surprise. It's also the time period covered by the Simon of Gitta historical fantasies of Richard L. Tierney, some of whose stories I've discussed in the past.

Tierney, Richard L.: Secrets of sha-Arthan takes a lot of inspiration from the late Hellenistic and early Roman eras. That's a period of history that's always fascinated me, so that's no surprise. It's also the time period covered by the Simon of Gitta historical fantasies of Richard L. Tierney, some of whose stories I've discussed in the past.

Tierney's stories deftly combine real world history and beliefs, particularly those relating to Gnosticism, with an unusual interpretation of H.P. Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos and swashbuckling adventure. This combination of elements is both unique and appealing to someone of my interests, which is why I consider the Simon of Gitta tales to be among the most important influences on my development of sha-Arthan as a RPG setting.

Vance, Jack: Rounding out this quartet of inspirational authors is Jack Vance, creator of The Dying Earth and its sequels, all of which have, to varying degrees, influenced sha-Arthan, though the original 1950 fix-up novel remains the most important. Like Smith's Zothique stories, I've looked to Vance for ideas about ancient, forgotten history, venal wizards, and cruel, otherworldly beings. However, the single most significant idea I've taken from Vance is that of secret science fiction, which is to say, an ostensibly fantasy setting that is, beneath the surface, based on scientific (or pseudo-scientific) principles. That's a big part of sha-Arthan and its eponymous secrets.

Vance, Jack: Rounding out this quartet of inspirational authors is Jack Vance, creator of The Dying Earth and its sequels, all of which have, to varying degrees, influenced sha-Arthan, though the original 1950 fix-up novel remains the most important. Like Smith's Zothique stories, I've looked to Vance for ideas about ancient, forgotten history, venal wizards, and cruel, otherworldly beings. However, the single most significant idea I've taken from Vance is that of secret science fiction, which is to say, an ostensibly fantasy setting that is, beneath the surface, based on scientific (or pseudo-scientific) principles. That's a big part of sha-Arthan and its eponymous secrets. In Part II, I'll talk about the other roleplaying games that have influenced the development of Secrets of sha-Arthan. For obvious historical reasons, this is something Gygax could never have done. However, I've played enough RPGs over the years that there's no question they've had as much of an impact on my thoughts about sha-Arthan as has fantasy literature. Revealing just what I've taken from them is, I think, every bit as important as revealing my literary inspirations.

March 25, 2024

Polyhedron: Issue #19

Issue #19 of Polyhedron (September 1984), like the previous issue, features a cover illustration promoting one of TSR's licensed RPGs, in this case The Adventures of Indiana Jones. The reputation of the Indiana Jones game has long – and somewhat understandably – suffered as a result of the game's narrow focus and presentation, squandering its real potential as a vehicle for pulp adventure. The scenario included in this issue, "The Temple of the Chachopoyan Warriors "(written by Doug Niles), does little to correct this. The adventure reframes the opening scenes of Raiders of the Lost Ark as a means of introducing the game and its rules to newcomers. While adequate to that specific task, it also reinforces the sense that the RPG would never really rise above its limited source material and that's a pity.

Issue #19 of Polyhedron (September 1984), like the previous issue, features a cover illustration promoting one of TSR's licensed RPGs, in this case The Adventures of Indiana Jones. The reputation of the Indiana Jones game has long – and somewhat understandably – suffered as a result of the game's narrow focus and presentation, squandering its real potential as a vehicle for pulp adventure. The scenario included in this issue, "The Temple of the Chachopoyan Warriors "(written by Doug Niles), does little to correct this. The adventure reframes the opening scenes of Raiders of the Lost Ark as a means of introducing the game and its rules to newcomers. While adequate to that specific task, it also reinforces the sense that the RPG would never really rise above its limited source material and that's a pity.

This issue's "Two Cents" is a rebuttal to last issue's rebuttal to another article, appearing in issue #14 – yikes! If nothing else, it's a reminder that roleplayers have always liked to argue with another about almost anything. It's also a reminder that my patience is very limited when it comes to such things, then or now. That said, this issue's installment, by Christopher Gandy, at least makes a few solid points, most importantly that, for many players, roleplaying is an escape and an opportunity to do and experience things they'd never be able – or want – to do in real life. There's nothing wrong with this and it can, in fact, serve a useful purpose.

"Lost Ships, Madmen, and Pirate Gold" by Antonio "Crazy Tony" O'Malley is a fun article intended for use with Gangbusters, Call of Cthulhu, Daredevils, or any other roleplaying game set in the 1930s (interestingly, Indiana Jones is not mentioned). The general thrust of the three-page piece concerns the care and feeding of pulp adventure campaigns. O'Malley covers a wide range of topics – legendary treasures, historical mysteries, gangsters, and ghosts, among others – with an eye toward offering advice on how best to make best use of them in play. The article is both creative and practical and I remember enjoying it when I first read it long ago, an opinion that didn't much alter upon re-reading it.

"... And the Gods Will Have Their Way" by Bob Blake concludes the "Prophecy of Brie" series of adventures begun back in issue #16. The adventure takes up the interior twelve pages of this issue and is designed to be removeable by bending back the staples that hold it together. Though I never mad direct use of it, I appreciated its attempt to provide a consistent cultural backdrop for the scenario, in this case, pseudo-Celtic, rather than the usual vague mishmash found in most Dungeons & Dragons modules at the time. On the other hand, the fact that this "mini-module" took up half of the issue's page count was a bit of an annoyance. As always, I suspect that the editors of Polyhedron were struggling with figuring just what the 'zine was supposed to be and how it differentiated itself from TSR's other gaming periodical, Dragon.

Frank Mentzer presents the results of the RPGA Network Item Design Contest, consisting of six winners selected from a pool of "almost a hundred." The items were judged in the categories of "usefulness," "originality," and "rules compliance." The grand prize winner, whose creator received a lifetime membership to the RPGA, is the talisman of the beast. Written for AD&D, the talisman enables its wearer to shapechange into the animal associated with it, as well as to speak with animals of the same type. Usable seven times a week, any attempt at an eighth use traps the wearer in anima form until the curse is dispelled by the Great Druid. With the exception of the taser rifle, intended for use with Star Frontiers, all the other winners are for AD&D – a reminder, I suppose, of just how much more popular it was than any of TSR's other offerings.

Tim Kilpin's "If Adventure Has a Game ... er, Name, It Must Be Indiana Jones!" is a two-page overview of The Adventures of Indiana Jones Role-Playing Game. It's essentially an advertisement masquerading as an article, though I do appreciate that there are some quotes from David Cook, in which he explains his intentions while designing the game. Alas, his intentions included not just a desire for "fast action" but also hewing as closely as possible to the characters and events of the two movies released at the time. Not to sound like a broken record, but it's a real shame that TSR either didn't (or couldn't – I've seen claims that it was Lucasfilm that dictated this) open up the world of Indiana Jones a little more, so as to include original characters and situations. Ah, well!

James M. Ward's "Cryptic Alliance of the Bi-Month" looks at The Created, a group of sentient androids and robots that believe themselves superior to the human beings who created them. The Created make for a great antagonistic cryptic alliance in Gamma World campaigns, which is why I like them. Compared to earlier articles in this series, this one doesn't add much to our knowledge beyond making The Created even more explicitly villainous than we already suspected (their leader is android/robot hybrid called V.A.D.E.R. X and, no, there's no explanation for that acronym).

"The Laser Pod" by Jon Pickens is a nice – and very useful – addition to the Star Frontiers starship combat system found in Knight Hawks. One of the oddities of baseline Knight Hawks is that fighter craft are too small to carry any type of laser weapons. Instead, they're armed exclusively with rockets. While this makes sense within the context of the starship construction rules, it nevertheless felt a little disappointing to those of who'd grown up imagining fighters dogfighting with lasers. Pickens presents a clever little option that simultaneously stays true to the original rules while also giving us laser fanatics what we've wanted all along. Bravo.

Finally, there's "Dispel Confusion" with more questions and answers about TSR's various RPGs. While reading this issue's sampling, a few thoughts occurred to me. First, the AD&D questions are overwhelmingly technical in nature, which is to say, they're about how to interpret the text of the rules as written, whereas the questions for most of the other games are much more in the realm of advice on how to handle situations the rules don't explicitly cover. This might simply be a consequence of AD&D having more rules than other TSR games, but I suspect it may speak to the culture surrounding AD&D as well. Second, there are no questions in this issue about Boot Hill. I can't help but wonder if this is reflective of its relatively small fanbase at the time.

As always, Polyhedron continues to be something of a moving target. Every issue offers a different mix of content, coverage, and quality, which, I suppose, is fairly typical of a zine that is increasingly relying on outside submissions for its content. Still, I find the inconsistency a little bit frustrating, making my enjoyment of this series similarly inconsistent.

March 24, 2024

Memories of Death

For reasons I'll explain in another post, I've been spending a lot of time looking at the examples of play provided in earlier roleplaying games. While not all games from the early days of the hobby include such examples, a great many of them do, starting with original Dungeons & Dragons in 1974. It's easy to understand why this was the case: RPGs were a genuinely new concept and most people in the 1970s, absent being introduced to them through others, would have required some sort of guidance on how to play them. As a kid, I didn't pay close attention to examples of play, because I learned how to play D&D from a friend's older brother, who'd already been gaming for some time before we first cracked open the copy of my beloved Holmes Basic rulebook.

While OD&D includes an example of play occurs in Volume 3, The Underworld and Wilderness Adventures, I didn't see it until many years after I'd already started playing RPGs. The first one I ever encountered was found in the aforementioned Holmes rulebook and made a big impression upon me, forming my sense of how a session of playing D&D is supposed to go. Unfortunately, the example glosses over how combat is supposed to work (something it has in common with its OD&D predecessor, I'd later learn). However, Holmes does include two examples of combat earlier in the rulebook, which I also remember quite vividly, if only for the names of the characters involved in them – Bruno the Battler, Mogo the Mighty, Malchor (a magic-user), and the Priestess Clarissa. It's strange that, more than four decades later, I can still recall all four of these names, but, as I've said many times, the Holmes rulebook made a profound impression upon me.

While OD&D includes an example of play occurs in Volume 3, The Underworld and Wilderness Adventures, I didn't see it until many years after I'd already started playing RPGs. The first one I ever encountered was found in the aforementioned Holmes rulebook and made a big impression upon me, forming my sense of how a session of playing D&D is supposed to go. Unfortunately, the example glosses over how combat is supposed to work (something it has in common with its OD&D predecessor, I'd later learn). However, Holmes does include two examples of combat earlier in the rulebook, which I also remember quite vividly, if only for the names of the characters involved in them – Bruno the Battler, Mogo the Mighty, Malchor (a magic-user), and the Priestess Clarissa. It's strange that, more than four decades later, I can still recall all four of these names, but, as I've said many times, the Holmes rulebook made a profound impression upon me.

The first combat example Holmes offer is short and details Bruno the Battler facing off against a goblin. Bruno comes out on top, though not before losing half his hit points. In the second example, Bruno is not so lucky and dies "a horrible death" to the venomous bite of a large spider. This, too, left a profound impression upon me and my friends, because it shows quite clearly how easy it is for D&D characters to die in combat, especially at low levels of experience.

The first combat example Holmes offer is short and details Bruno the Battler facing off against a goblin. Bruno comes out on top, though not before losing half his hit points. In the second example, Bruno is not so lucky and dies "a horrible death" to the venomous bite of a large spider. This, too, left a profound impression upon me and my friends, because it shows quite clearly how easy it is for D&D characters to die in combat, especially at low levels of experience. The next example of play I probably encountered was the lengthy one found pages 97–100 of the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide. As a young person, this was probably my favorite example of play, both for its level of detail and its shocking conclusion – "You see a sickly gray arm strike the gnome as he's working on the spike, the gnome utters a muffled cry, and then a shadowy form drags him out of sight ... You hear some nasty rending noises and gobbling sounds ..." Elsewhere, it's noted that the poor gnome was surprised by ghouls, who paralyzed and then quickly devoured him. Yikes!

The example of play in the 1981 Tom Moldvay-edited D&D Basic Rules is probably the most famous of this entire "genre." Though not as extensive as the example of the DMG, it's still quite longer, taking up slightly more than an entire page. What makes this example so well-known is the death of the thief, Black Dougal (who also seems to have died on another occasion, as reported in the

Dungeon Masters Adventure Log

). "Black Dougal hasps 'Poison!' and falls to the floor. He looks dead." "I'm grabbing his pack to carry treasure in." Fredrik the dwarf is one cold dude.

The example of play in the 1981 Tom Moldvay-edited D&D Basic Rules is probably the most famous of this entire "genre." Though not as extensive as the example of the DMG, it's still quite longer, taking up slightly more than an entire page. What makes this example so well-known is the death of the thief, Black Dougal (who also seems to have died on another occasion, as reported in the

Dungeon Masters Adventure Log

). "Black Dougal hasps 'Poison!' and falls to the floor. He looks dead." "I'm grabbing his pack to carry treasure in." Fredrik the dwarf is one cold dude.What unites all these examples of play is, of course, death, specifically the death of player characters, which probably explains why they all had such a powerful effect on me when I first entered the hobby. My first experience of fantasy gaming was through the Dungeon! boardgame. You couldn't die in Dungeon! If your piece was defeated in combat, you lost treasure and had to retreat, but you didn't choose a new piece with which to play. But D&D was completely different in this regard. The fact that death was nothing unusual but simply a normal consequence of play was weirdly exciting to me. It implied there were actual stakes and that merely surviving a dungeon exploration was a true achievement.

As a referee, I wouldn't say that I'm a soft touch, but, in general, I don't take it as my job to kill player characters, unlike my friend's older brother, who was often quite gleeful about doing so. At the same time, I don't shy away from killing off even longstanding PCs if the dice simply don't go their way. To me, death – even meaningless death due to a failed saving throw – always has to be an option or less why bother rolling dice at all? Why have rules? Why not simply engage in collaborative storytelling instead of playing a roleplaying game? I'm sure not everyone playing RPGs agrees with this stance, but it's deeply ingained in me, instilled long ago by reading the examples of play I found in my earliest copies of Dungeons & Dragons.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers