James Maliszewski's Blog, page 61

March 21, 2024

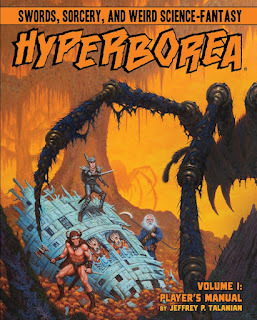

REVIEW: Hyperborea

When I first read

Astonishing Swords & Sorcerers of Hyperborea

, two things about it greatly impressed me. Most significant was that this roleplaying game of "swords, sorcery, and weird fantasy" demonstrated an obvious love for the pulp fantasies of Robert E. Howard, H.P. Lovecraft, and Clark Ashton Smith. Equally obvious was its love for Gygaxian AD&D. The latter should have come as no surprise, given designer Jeff Talanian's stint as Gygax's protégé and amanuensis for the uncompleted Castle Zagyg project. Still, both these qualities endeared AS&SH – an infelicitous acronym of there ever was one – to me. In the more than a decade since its initial release in 2012, the game has found a place for itself among fans of old school Dungeons & Dragons and its descendants, particularly among those, like myself, whose tastes tend toward the pulpy end of the fantasy spectrum. A second edition of the game was released in 2017 in the form of a single hardcover book. The new edition added some new material to the contents of its original boxed rulebooks, as well as new art and layout. Unfortunately, the second edition rulebook was over 600 pages in length and very unwieldy to use, either in play or as a reference volume. On the other hand, the many adventures published to support the new edition were both excellent and evocative of Weird Tales-inspired fantasy.

When I first read

Astonishing Swords & Sorcerers of Hyperborea

, two things about it greatly impressed me. Most significant was that this roleplaying game of "swords, sorcery, and weird fantasy" demonstrated an obvious love for the pulp fantasies of Robert E. Howard, H.P. Lovecraft, and Clark Ashton Smith. Equally obvious was its love for Gygaxian AD&D. The latter should have come as no surprise, given designer Jeff Talanian's stint as Gygax's protégé and amanuensis for the uncompleted Castle Zagyg project. Still, both these qualities endeared AS&SH – an infelicitous acronym of there ever was one – to me. In the more than a decade since its initial release in 2012, the game has found a place for itself among fans of old school Dungeons & Dragons and its descendants, particularly among those, like myself, whose tastes tend toward the pulpy end of the fantasy spectrum. A second edition of the game was released in 2017 in the form of a single hardcover book. The new edition added some new material to the contents of its original boxed rulebooks, as well as new art and layout. Unfortunately, the second edition rulebook was over 600 pages in length and very unwieldy to use, either in play or as a reference volume. On the other hand, the many adventures published to support the new edition were both excellent and evocative of Weird Tales-inspired fantasy.2022 saw the appearance of a third edition of the game, this time in the form of two, smaller hardcover volumes – a Player's Manual and a Referee's Manual , each around 300 pages long. In addition to their much more convenient size, these new volumes contain even more art than the two previous editions, as well as a cleaner layout and organization. The game also acquired a new title with this edition – Hyperborea. The combined effect of all these changes is, in my opinion, the best-looking and easiest-to-use edition of the game to date.

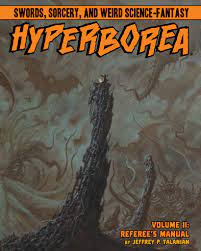

As pleased and impressed as I am by the visual improvements of the third edition, its actual content is not significantly changed from second edition. Aside from combat, which is much simplified, most of the changes are quite small, small enough that I, as a casual player of the game over the last decade, had to dig around online to notice most of them. There are also new additions to the selections of monsters, spells, and magic items, not to mention playable human races. When combined with all aforementioned esthetic changes, I think this is more than sufficient justification for a new edition, but whether it's enough for any individual to replace their existing copy of second edition with it is for each person to decide himself. By design, none of the changes or additions make, say, adventures written with 3e in mind incompatible with previous ones, so there is no necessity in "upgrading."

As pleased and impressed as I am by the visual improvements of the third edition, its actual content is not significantly changed from second edition. Aside from combat, which is much simplified, most of the changes are quite small, small enough that I, as a casual player of the game over the last decade, had to dig around online to notice most of them. There are also new additions to the selections of monsters, spells, and magic items, not to mention playable human races. When combined with all aforementioned esthetic changes, I think this is more than sufficient justification for a new edition, but whether it's enough for any individual to replace their existing copy of second edition with it is for each person to decide himself. By design, none of the changes or additions make, say, adventures written with 3e in mind incompatible with previous ones, so there is no necessity in "upgrading."Players of Gygaxian AD&D will immediately find Hyperborea familiar – six attributes, a plethora of classes and sub-classes (22 in all!), nine alignments, multiple lists of spells, etc. It's a big, baroque stew of often idiosyncratic but flavorful options, but it's never overwhelming. In large part that's because of Talanian's presentation of the material, but it helps, too, that Hyperborea is much more clearly a cohesive ruleset than a sometimes-contradictory hodgepodge built up over time, which only makes sense, given that Hyperborea came out decades after AD&D. Consequently, I consider Hyperborea the best modern restatement of AD&D.

Of course, the real joy of Hyperborea is not its rules, however solid they are. Where it most stands out is setting. The titular Land Beyond the North Wind is a flat, hexagonal plane that was once a component of "Old Earth" and the source of many of its myths and legends. Inhabited by the peoples of many ancient cultures – Amazons, Atlanteans, Kelts, Kimmerians, Norse, Picts, and more – Hyperborea is a adventuresome, horror-tinged sandbox in which to set all manner of pulp fantasy adventures. If you read about it in story by REH, HPL, or CAS, you can easily set it in Hyperborea. The setting is sketched out with just enough detail that the referee isn't left entirely to his own devices, but neither is he hamstrung. Think of the original World of Greyhawk folio and you have a good idea of the level of detail I'm talking about.

If I have a complaint about Hyperborea compared to its predecessors, it's that the setting map is now presented in a softcover

Atlas of Hyperborea

, which is sold separately. Previous editions, including the second edition hardcover, included a very nice, fold-out map of the lost continent; the Atlas chops up that map into smaller (and much less usable, in my opinion) portions. It's a shame, because Glynn Seal's map of Hyperborea is lovely and deserves better.

If I have a complaint about Hyperborea compared to its predecessors, it's that the setting map is now presented in a softcover

Atlas of Hyperborea

, which is sold separately. Previous editions, including the second edition hardcover, included a very nice, fold-out map of the lost continent; the Atlas chops up that map into smaller (and much less usable, in my opinion) portions. It's a shame, because Glynn Seal's map of Hyperborea is lovely and deserves better. Hyperborea is a product of real passion and dedication, both to the legacy of Gary Gygax and to the imaginations of the greatest writers of Weird Tales. It's a good example of what can be accomplished by a designer with a singular vision and a dedication to seeing it realized. Certainly, Hyperborea is not a fantasy roleplaying for everyone. Its focus and authorial voice are distinctive, even a little out of step with what some may want. But if what you're looking for is a florid, flavorful take on pulp fantasy that nevertheless hews closely to the outlines of Gygaxian AD&D, you're in for a treat.

Should I Go to Gamehole Con Again?

Being shy and introverted by nature, I never developed the habit of going to gaming conventions in my youth. Nevertheless, I attended one Origins, back in 1991, because it was held in Baltimore, not far from where I grew up. I also attended one GenCon (2001), because I was, at the time, working quite seriously as a freelance gaming writer and I saw it as a good opportunity to meet people associated with the various publishers who'd employed me. In both cases, I had a good time and I still look back fondly on the experiences. For example, having the chance to sit in the Steve Jackson Games booth with the late Loren Wiseman to talk about Traveller for hours remains a cherished memory of mine to this day.

Being shy and introverted by nature, I never developed the habit of going to gaming conventions in my youth. Nevertheless, I attended one Origins, back in 1991, because it was held in Baltimore, not far from where I grew up. I also attended one GenCon (2001), because I was, at the time, working quite seriously as a freelance gaming writer and I saw it as a good opportunity to meet people associated with the various publishers who'd employed me. In both cases, I had a good time and I still look back fondly on the experiences. For example, having the chance to sit in the Steve Jackson Games booth with the late Loren Wiseman to talk about Traveller for hours remains a cherished memory of mine to this day.In the years that followed, I simply didn't have the time or, frankly, the inclination to attend any more conventions. I had young children at home, so my devotion to being a freelance writer waned, as did my desire to travel anywhere, never mind gaming conventions. My personal world contracted quite a bit – and I don't mean that in a bad way – and remained quite small until I started writing this blog. Through it and my involvement in the early days of the OSR, I started "meeting" more and more people who shared my interests and outlook. That, in turn, planted the seeds of the idea that maybe I should reconsider going to conventions.

I hate traveling, especially by air. Prior to September 11, 2001, air travel was barely tolerable. Afterwards, I couldn't stomach the thought of it and abandoned the idea of ever using it again. However, my good friend (and co-host of the Hall of Blue Illumination podcast), Victor Raymond, slowly convinced me to consider going to Gamehole Con. He told me that GHC was still fairly small in size and, even as it had grown, it retained a feeling of coziness that might be more amenable to an introvert like myself. "Small enough that you can find people you want to meet – and large enough that you can avoid those you don't want to," is how he put it.

Eventually, I took the plunge and first attended the con in 2017. As Victor had told me, I found it very much to my liking. I was finally able to meet a number of people with whom I'd been friends online for years, which was extremely gratifying. I also met numerous gaming luminaries of the past, which was a real treat. My experience in 2017 was so enjoyable that I happily returned the next year. The second time I attended was every bit as good as the first. This led me to believe that I might perhaps make this an annual thing. Indeed, the next year, I not only planned to return, but planned to participate in the Tékumel Track of events sponsored by the Tékumel Foundation. Despite my dislike of large gatherings and air travel, I thought I'd finally found a convention for me.

Unfortunately, in 2019, I was hit by a car just days before leaving for what would have been my third GHC. Though I was able to walk away from the accident with comparatively minor injuries, I had to cancel my con appearance. I nevertheless intended to return to Madison, Wisconsin in 2020 but the real world had other ideas. Though the convention eventually returned to its former self, the break – and my own lack of desire to be subjected to health theater in addition to security theater while traveling – put an end to my attendance at Gamehole Con.

Lately, though, I've started to wonder whether I should try to attend again. Several friends of mine, including at least one player in my ongoing Twilight: 2000 campaign, has mentioned that they'd be going to the con. Several more have suggested that they might go, especially if I were going to do so. Further, I've been considering the possibility of refereeing Secrets of sha-Arthan scenarios for people other than my friends, as a way of playtesting its rules and gauging reactions to its setting by a larger sample. Perhaps a con setting might be a good way to do that?

So, what do you think? Should I go to Gamehole Con this year? Obviously, my decision won't hinge entirely on what anyone posts in the comments, but I do like to hear other perspectives. I had a lot of fun at GHC in the past, so it's not as if attendance would be something wholly alien to me. At the same time, I'm (once again) out of practice when it comes to attending a large event like this, something my introverted nature instinctively recoils at. That's why I'm curious to know your thoughts on the matter.

March 20, 2024

Stuck in the Past

As I've no doubt explained previously, I was never much of a comics reader as a kid – or, more precisely, I was never much of a superhero comics reader as a kid. With the exception of Doctor Strange, Master of the Mystic Arts, which I picked up intermittently, the two comics I followed with any devotion were both science fiction titles, Star Wars (about which I've written many times before) and Micronauts (about which I don't believe I have).

As I've no doubt explained previously, I was never much of a comics reader as a kid – or, more precisely, I was never much of a superhero comics reader as a kid. With the exception of Doctor Strange, Master of the Mystic Arts, which I picked up intermittently, the two comics I followed with any devotion were both science fiction titles, Star Wars (about which I've written many times before) and Micronauts (about which I don't believe I have). Nevertheless, like all American boys growing up in the 1970s, I was still very much aware of superheroes, thanks in no small part to their TV and movie adaptations, including cartoons. Perhaps because he was Marvel's most popular – and merchandised – character at the time, I had a special fondness for Spider-Man. I loved the terrible 1960s cartoon, which I saw in reruns, as well as the equally awful 1977 live action series, starring Nicholas Hammond of The Sound of Music Fame. I also remember watching the Adam West Batman series, various incarnations of Super Friends, the 1978 Superman movie, and probably others I've long forgotten.

As I got older, I retained a vague affection for the idea of superheroes, especially after I started playing RPGs. I can still vividly recall some of the adventures my friends and I had playing, first,

Champions

, and, later, Marvel Super Heroes. I remember, too, when we started to see big budget Hollywood movies featuring various costumed characters, starting with Tim Burton's Batman. The release of that movie in 1989 was a major cultural event and its success not only spawned three sequels but also paved the way for yet more superhero movies, a trend that has continued to the present day.

As I got older, I retained a vague affection for the idea of superheroes, especially after I started playing RPGs. I can still vividly recall some of the adventures my friends and I had playing, first,

Champions

, and, later, Marvel Super Heroes. I remember, too, when we started to see big budget Hollywood movies featuring various costumed characters, starting with Tim Burton's Batman. The release of that movie in 1989 was a major cultural event and its success not only spawned three sequels but also paved the way for yet more superhero movies, a trend that has continued to the present day.Despite not calling myself a fan of superheroes, I've seen more than my fair share of the superhero movies released in the last three decades, enjoying some more than others. One of the things that's always bugged me about these movies (and other adaptations) is how many of them continue to tread the same ground that their original source material did decades ago. There may indeed be nothing new under the sun, but did we really need to see another version of "The Dark Phoenix Saga?" For that matter, have there been any new superheroes or superhero stories produced in the last couple of decades with any staying power? Why are the biggest pop cultural characters all products of the 1980s or earlier?

I think about this often, most recently during a recent trip with my family. While perusing some weird snacks and candies in a store, I spied a tall, thin, red can featuring what looked to me like Larry Elmore's iconic cover painting for the Frank Mentzer-edited Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set (1984). Drawing closer, it turned that, yes, it was Elmore's artwork on a D&D-branded energy drink calling itself a "Hero's Potion of Power." Intrigued, I bought the thing, but I didn't have the courage to try it. That job fell to my daughter, who declared it "alright, but nothing special."

I think about this often, most recently during a recent trip with my family. While perusing some weird snacks and candies in a store, I spied a tall, thin, red can featuring what looked to me like Larry Elmore's iconic cover painting for the Frank Mentzer-edited Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set (1984). Drawing closer, it turned that, yes, it was Elmore's artwork on a D&D-branded energy drink calling itself a "Hero's Potion of Power." Intrigued, I bought the thing, but I didn't have the courage to try it. That job fell to my daughter, who declared it "alright, but nothing special." On the same trip, we went to a bookstore not far from where I grew up. I hadn't found anything to purchase, so I stood out near the lobby of the store while my daughter paid for a book. When I looked over at the checkout counter, I saw a display filled with little boxes sporting an immediately recognizable color scheme. I did an almost comical double take, because I was sure that my aging eyes must have erred in some way, because I couldn't conceive that I was seeing what I, in fact, was seeing – the familiar blue and brown palette of the AD&D Monster Manual.

Sure enough, that's exactly what it was. Apparently, the boxes contain one of a series of randomized plastic monster figurines based on the illustrations of the original Monster Manual. This, frankly, befuddled me almost as much as the Hero's Potion of Power, but then I've never really understood the appeal of these expensive, randomized "loot boxes." Beyond that, why were the figurines based on the artwork of Dave Trampier and Dave Sutherland rather than more contemporary designs? Did it have something to do with D&D's 50th anniversary? I'm honestly not sure of the answer. For all I know, there may be similar loot boxes available for the monsters of later D&D editions, but my gut tells me that's unlikely to be the case. (If I'm mistaken about this, feel free to correct me in the comments).

Sure enough, that's exactly what it was. Apparently, the boxes contain one of a series of randomized plastic monster figurines based on the illustrations of the original Monster Manual. This, frankly, befuddled me almost as much as the Hero's Potion of Power, but then I've never really understood the appeal of these expensive, randomized "loot boxes." Beyond that, why were the figurines based on the artwork of Dave Trampier and Dave Sutherland rather than more contemporary designs? Did it have something to do with D&D's 50th anniversary? I'm honestly not sure of the answer. For all I know, there may be similar loot boxes available for the monsters of later D&D editions, but my gut tells me that's unlikely to be the case. (If I'm mistaken about this, feel free to correct me in the comments). Of course, this past Christmas, my wife bought me a Dungeons & Dragons T-shirt that she unexpectedly came across while shopping. She knows I'm normally not a wearer of such things – I abhor the brandification of the game – but the fact that the shirt featured the Erol Otus cover painting of Tom Moldvay's Basic Set was sufficiently unusual that she decided to take a chance. She was right to do so, because I was positively tickled by the gift and often wear it as a sleep shirt (I'd never wear it while out and about – I'm too old for that sort of thing).

Of course, this past Christmas, my wife bought me a Dungeons & Dragons T-shirt that she unexpectedly came across while shopping. She knows I'm normally not a wearer of such things – I abhor the brandification of the game – but the fact that the shirt featured the Erol Otus cover painting of Tom Moldvay's Basic Set was sufficiently unusual that she decided to take a chance. She was right to do so, because I was positively tickled by the gift and often wear it as a sleep shirt (I'd never wear it while out and about – I'm too old for that sort of thing).I can't help but wonder why it is that, in the pop cultural sphere, so much of what is being presented and sold to us are the products of earlier generations of creative minds. Is this simply the result of a lack of imagination or is it because, on some level, we know that we'll never be able to come up with anything better than our predecessors? If I were to travel back in time to tell my younger self that, decades from now, there'd still be new Star Trek shows and Star Wars movies – or that I couldn't care less about any of them – I doubt he'd believe me and yet here we are. Nostalgia is a hell of a drug, but what does it mean when popular culture spends decades luxuriating in it?

I'm as happy as anyone to see Erol Otus art on a T-shirt (even if he's unlikely to have profited from it in any way). At the same time, I think there's something not just decadent but even stagnant about endlessly recycling the pop culture of the 50s, 60, 70s, and 80s only even more vapid and rampantly consumerist than before. Have we simply run out of new ideas? Or do the new ideas simply lack the appeal of the older ones? What's really going on here and what does it mean?

Number 9

A couple of weeks ago, my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign marked its 9-year anniversary. As I alluded to in a post earlier this year, the campaign continues to grow and evolve. I added a new player to our merry little band, bringing us to eight (plus myself, of course), and his character helped usher in a new phase of the campaign.

A couple of weeks ago, my House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign marked its 9-year anniversary. As I alluded to in a post earlier this year, the campaign continues to grow and evolve. I added a new player to our merry little band, bringing us to eight (plus myself, of course), and his character helped usher in a new phase of the campaign. Every time another anniversary is reached, I goggle at the fact that we've somehow managed to keep this going for so long. It's truly a wondrous thing and, while there's undoubtedly a good deal of luck involved, I think there are several other factors that have contributed to the campaign's continued success. In the interest of encouraging others who are interested in keeping a RPG campaign going for nearly a decade of continuous, weekly play, here's what wisdom I have to offer:

March 19, 2024

Retrospective: Time of the Dragon

When I first started writing these Retrospective posts, I set myself some broad historical parameters, in order to pare down the absolutely immense number of potential games and gaming products about which I could write. Those parameters were (very roughly) the first decade of the RPG hobby, meaning the years 1974–1984, which maps pretty closely to what I've previously called the Golden Age of Dungeons & Dragons. Like all such parameters, mine was somewhat (though not entirely) arbitrary and, over the years, I've deviated from it when I felt there was a worthy product whose publication date fell outside that range of years.

When I first started writing these Retrospective posts, I set myself some broad historical parameters, in order to pare down the absolutely immense number of potential games and gaming products about which I could write. Those parameters were (very roughly) the first decade of the RPG hobby, meaning the years 1974–1984, which maps pretty closely to what I've previously called the Golden Age of Dungeons & Dragons. Like all such parameters, mine was somewhat (though not entirely) arbitrary and, over the years, I've deviated from it when I felt there was a worthy product whose publication date fell outside that range of years. For the most part, though, I've stuck to my original framework, if only out of habit and some degree of stubbornness. However, a conversation with a very old friend of mine reminded me that the early years of 1990s were more than thirty years ago. Likewise, the first non-TSR edition of D&D was released just shy of a quarter-century ago, making it almost as old today as OD&D was at the time 3e was published. Shocking though these reminders were to my increasingly aged self, the served a valuable purpose in giving me some additional perspective on the history of the hobby. 2024, after all, marks the 50th anniversary of Dungeons & Dragons and I'm still focusing very narrowly on a small sliver of that half-century. Perhaps it was time to expand Grognardia's gaze a little further into the future past – to the end of TSR's existence, at least.

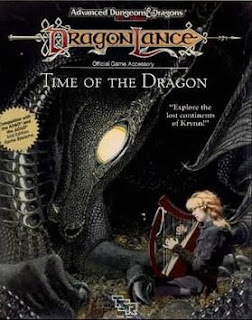

And what better way to kick off the expanded coverage of the Retrospective series than a post about my favorite Dragonlance product, 1989's Time of the Dragon? Yes, you read that right: my favorite Dragonlance product. I know that I am well known as a Dragonlance hater, but the truth is that my feelings toward the setting and line of AD&D products is rather more nuanced than simple hatred. I don't actually hate Dragonlance itself so much as what its popularity and success did to the subsequent direction of Dungeons & Dragons, nudging it down the road toward whatever it is that it's become in recent decades.

Time of the Dragon is the brainchild of none other than David "Zeb" Cook, which may explain why I've always had such an affection for it. It's also one of those glorious boxed sets that TSR produced in large numbers during the 2e era, something no one else in the hobby (with the possible exception of the Chaosium of old) has ever done as well. Consisting of two books – the 112-page Guide Book to Taladas and the 48-page Rule Book of Taladas, along with 24 full-color cardstock sheets and 4 poster maps – Time of the Dragon presents for the first time another continent of Krynn, the aforementioned Taladas. Like the more familiar Ansalon, Taladas suffered from the events of the Cataclysm, when a single huge meteor fell from the sky and nearly sundered the continent. However, Taladas has its own unique races, cultures, and history, not to mention relationship with the gods that set it apart from Ansalon.

That's a big part of why I retain an affection for Time of the Dragon. Whereas Ansalon and the modules focusing on the War of the Lance have a faux-Tolkien-meets-Ren-Faire vibe to them, Taladas is a darker, harsher place, owing in part to how it experienced the Cataclysm. The meteor strike caused massive terrain-altering earthquakes, resulting in lava flows and volcanic eruptions that blackened the skies. Survival in this environment required hard decisions by the peoples and societies of Taladas, making it a crueler, more pragmatic and occasionally xenophobic place. In some respects, Taladas anticipates many aspects of the later Dark Sun setting, though admittedly lacking in the more sword-and-planet feel of the latter.

Consequently, Taladas feels very different from Ansalon, almost to the point of feeling as if the continent were not located on Krynn. Its peoples and societies deviate from the standard assumptions of both AD&D and Dragonlance. For example, the majority of the elves of Taladas have a nomadic, horse-based culture quite unlike those of Ansalon, while a minority of the race are reclusive tricksters who steal human babies to replenish their own sickly stock. Similarly, the dwarves of Taladas do not dwell underground and, in fact, have a fear of subterranean locales. Kender – much disliked in many gaming circles – barely exist in Taladas and those who do lack the carefree attitudes of their Ansalon cousins. Taladas is also home to numerous new playable races, like goblins, ogres, lizard men, and minotaurs, the latter of which rule a Roman-inspired empire. Combined with several distinct human cultures, likewise inspired by historical antecedents, Taladas would never be mistaken for Ansalon.

Time of the Dragon is also notable for its various rules changes and alterations to 2e. The one I remember most are its kits, an innovation most AD&D players would probably associate with the interminable The Complete X Handbook series, but which, so far as I recall, debuted in this boxed set. At any rate, it's the first place I encountered the idea of kits and I was immediately taken with them. For those unfamiliar with them, a kit is a set of small tweaks to a standard character class to reflect the idiosyncrasies of a particular race and/or culture. For example, there's a kit for the horse-riding bowmen of the Uigan culture and another for the gnomish Companions of the Dead, an elite group of fighters. What I think works about these kits, as compared to those that appeared later, is that they're all very specific and serve to ground the character that possesses one in the setting, which is something I find very agreeable.

I don't get the impression that Taladas was very well received by Dragonlance fans in general, though, as I recall, there were a handful of supplements produced to support it during the 2e era. If my assessment is correct, I can understand why that might have been the case. Aside from a few high-level connections to standard Krynn, such as the influence of the three moons over magic, Taladas might as well be its own unique setting. Even the signature draw of Dragonlance – the dragons – are downplayed and re-contextualized so that, if it weren't for the DL logo on the box, one might be hard pressed to recognize it as taking place on Krynn. That might also explain why I was (and am) so fond of Time of the Dragon: it's a fascinating experiment in building a distinct and unusual AD&D setting that doesn't quite fit into the usual array of building blocks, which is itself a feature of the entire 2e era of AD&D.

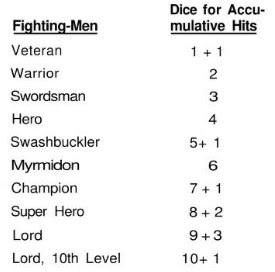

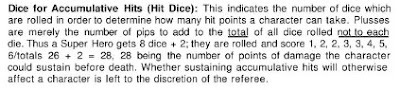

Dice for Accumulative Hits

Recently, an acquaintance of mine asked a question about original, pre-Greyhawk OD&D (1974) for which I had no immediate answer: how are hit points determined when a character gains a level? That may seem like a very simple question, but consider the following chart from Men & Magic:

If you look at the second column, you'll see there's an uneven progression of "dice for accumulative hits" – 1+1, 2, 3, 4, 5+1, etc. Though the chart above is for the fighting man, both the magic-user and cleric charts are quite similar in this regard, which is why I was asked the question about how hit points are determined upon gaining a level.

If you look at the second column, you'll see there's an uneven progression of "dice for accumulative hits" – 1+1, 2, 3, 4, 5+1, etc. Though the chart above is for the fighting man, both the magic-user and cleric charts are quite similar in this regard, which is why I was asked the question about how hit points are determined upon gaining a level.If the player of a first-level fighting man rolls 1d6+1 to determine his character's hit points, what does he do when his character acquires the 2000 experience points necessary to gain level 2? How many dice does he roll and add to the total? OD&D's rules are not especially clear on this point, as we can see:

The example in the text is rather unhelpful as it does not describe the process of rolling additional hit points upon gaining a level. Instead, it simply presents how to roll the hit points of Level 8 fighting man divorced from any other context.

The example in the text is rather unhelpful as it does not describe the process of rolling additional hit points upon gaining a level. Instead, it simply presents how to roll the hit points of Level 8 fighting man divorced from any other context. Empire of the Petal Throne was first published in 1975 and its rules are clearly a variant of pre-Greyhawk OD&D. Consequently, when I have some question about how the rules of OD&D are to be interpreted, I often take a look at EPT. There's no guarantee that EPT's presentation is necessarily representative of the original intention (if any) of OD&D's rules, but, if nothing else, they usually offer some insight into how one person chose to interpret those rules, which is better than nothing.

In this case, EPT suggests that, upon gaining a level, the player rolls the number of dice prescribed by the rules and totals the result. If the total is higher than his character's previous hit point total, the new total is used. If it's lower, then the previous total is retained. This approach makes a lot of sense to me, since, among other things, it helps to ameliorate bad rolls for hit points over time (provided the character survives, of course). It also provides a simple way to deal with the uneven progression of hit dice. Whether this approach is what was intended in OD&D, I simply have no idea.

Of course, it's possible I'm simply missing something very obvious or that this topic has been well explained elsewhere. If so, I'd love to be corrected, since it's a question that really stumped me when I was asked about it. Back when I was playing OD&D in my Dwimmermount campaign, I had already come under the sway of the EPT interpretation and made ready use of it. Later, we adopted Greyhawk's one additional hit die per level approach, so I never had to grapple with this area of ambiguity.

Thinking about it now, I can't help but assume it's a topic that's been examined thoroughly by better exegetes than myself, but perhaps not. Please let me know what, if anything, I've been missing in the comments.

March 18, 2024

Polyhedron: Issue #18

Serendipity is a funny thing. No sooner did I mention my childhood affection for Spider-Man than I find that issue #18 of Polyhedron (July 1984) features everyone's favorite web-slinger facing off against the Scorpion on its cover. This only makes sense, of course, since TSR's Marvel Super Heroes debuted around this time and was a big hit for the company. In fairly short order, it seemed as if there were nearly as many adventures being released for MSH as there were for Dungeons & Dragons, though my memory might well be faulty.

Serendipity is a funny thing. No sooner did I mention my childhood affection for Spider-Man than I find that issue #18 of Polyhedron (July 1984) features everyone's favorite web-slinger facing off against the Scorpion on its cover. This only makes sense, of course, since TSR's Marvel Super Heroes debuted around this time and was a big hit for the company. In fairly short order, it seemed as if there were nearly as many adventures being released for MSH as there were for Dungeons & Dragons, though my memory might well be faulty.

Spidey and the Scorpion form the basis for this issue's "Encounters" article, written by none other than Jeff Grubb, the designer of Marvel Super Heroes. Like all previous "Encounters" articles, this one is brief, but Grubb nevertheless makes the most of the limited space, presenting a scenario in which Spider-Man must rescue J. Jonah Jameson from a subway car that's been commandeered by Scorpion. It's straightforward and simple but does a good job, I think, of presenting the kind of situation in which the Web-head often found himself.

James M. Ward's "Cryptic Alliance of the Bi-Month" focuses on the mutant mirror image of the Knights of Genetic Purity, the Iron Society. Also known as the Mutationists, the Iron Society seeks to rid the post-apocalyptic Earth of all non-mutated life, with pure strain humans being the primary target of their ire. Needless to say, this makes the Society an object of fear in Gamma World and I always felt that they'd be used primarily as antagonists in most campaigns. Compared to the Knights, who might excellent villains in my opinion, the Iron Society somehow feels a bit more one-note and the article does little to change my mind on this, alas.

"Remarkable, Incredible, Amazing" by Steve Winter. As you might guess from its title, it's an overview of the then-newly released Marvel Super Heroes RPG. It's basically an advertisement intended to entice gamers into buying TSR's latest product and, in that respect, it does a fair job. Much more interesting is Roger E. Moore's "Kobolds and Robots and Mutants with Wings." Over the course of three pages. Moore talks first about the joys of "hybrid" games that mix and match rules and setting elements, something that even the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide discusses briefly. He then moves on to talk about various hybrid games he's run, such as when AD&D adventurers made use of a well of many worlds to travel to the universe of Bunnies & Burrows to fight rats in thrall with agents of the Cthulhu Mythos. Finally, he presents a lengthy discussion of kobalts – kobolds who traveled to Gamma World's setting, were mutated by radiation, and then bred true as a distinct species. Moore stats them up for both GW and AD&D and presents lots of information on how they could be used in both games. As I said, it's a very interesting article and a reminder of just how imaginative a writer Moore was.

"The Magic-User" by James M. Ward presents yet another "archetypical" [sic] example of a Dungeons & Dragons class, including her personality, skills, possessions, and holdings. In this case, that's Delsenora, an older woman who uses potions of longevity to retain her youth, who has a particular hatred for powerful undead, like vampires and liches. She also has a passion for flying through the use of magic. Consequently, she's built her castle high in the mountains, in a place otherwise inaccessible to those without flight. Appended to the end of Delsenora's description are two more magic-users, one by Ward (named Lidabmob – Bombadil spelled backwards) and another by Susan Lawson, presumably a RPGA member.

"Two Cents" by Joseph Wichman is a rambling opinion piece in which the author, another RPGA member, covers a number of vaguely related topics under the header of "roleplaying." He begins by arguing, contra the "Two Cents" column in issue #14, that roleplaying is not the same as acting and that any referee who expects his players to immerse themselves deeply in their roles is being unreasonable. He also touches on "troublesome" players, evil characters, and player vs character knowledge – all perennial topics in the gaming magazines of my youth. While I don't disagree with anything the author writes here, the article is somewhat frustrating to read, since it bounces around from one subject to the next.

"Layover at Lossend" by Russ Horn, yet another RPGA member, is a short Star Frontiers scenario set on the titular planet of Lossend. The format of the single-page scenario reminds me a bit of the "Encounters" feature, in that it includes of player characters to be used in conjunction with it. The adventure itself isn't particularly worthy of comment, since it's very short and sketchy, leaving most details to the referee to work out. What is interesting is that Horn refers to the referee – the official term for the Game Master in the game – as "the DM." This is obviously just a small slip-up, both on the part of the writer and the Polyhedron editorial staff. However, I think points to the extent to which the terminology of Dungeons & Dragons had become the defaults in RPG discussions, even discussions about other games.

"Money Makes the World Go Round" by Art Dutra – again, an RPGA member – is a thoughtful little piece about the role of money and treasure in an ongoing D&D campaign. Dutra's focus is primarily from the side of the referee, highlighting the ways that money can be used to both motivate and impede player characters. He points out all the costs that PCs can incur during a campaign, especially those that are overlooked, like training and converting gems into coins, among many others. Dutra is absolutely correct, in my opinion, that referees often fail to take into account the, if you'll forgive the pun, value of money as a driver of a campaign. My only criticism is that focusing on taxes, exchanges rates, hidden costs, and other expenses can very quickly become tedious, or at least that's been my experience. Finding a way to keep money in mind without degenerating into an exercise in bookkeeping would be truly worthwhile topic for an article or essay.

Speaking of tedious, this issue's "Dispel Confusion" is largely filled with very persnickety rules questions of the sort that bore to tears. Whether because of laziness or a lack of intelligence, I've always been much more of a rulings guy rather than a rules guy, so this stuff frequently baffles me. I'm especially baffled by questions that begin "Can I ...?" as if the sender felt he needed TSR's permission to introduce something into his own campaign. I suppose these are the inevitable fruits of the company's attempts to maintain tight control over all of its games and to discourage its customers from buying or making use of "inferior" supplementary materials.

Issue #18 of Polyhedron shows the continued evolution of the 'zine. Perhaps the biggest change is the inclusion of many more articles submitted by RPGA members. That's a welcome change, though the quality of those submissions seems to vary quite a bit. Over time, I suspect that, too, will change, but, for the moment, it gives the issue a much more uneven feel than some of its immediate predecessors. Nevertheless, I look forward to seeing what future issues have in store.

The Waydreland Mermaid

One of the things about this blog that continues to give me joy are the people I meet through it. Recently, I was contacted by artist Alan Howcroft as a result of my blog post about issue #31 of White Dwarf. Alan provided the issue with its evocative cover painting. Forty years after the cover first appeared, he put together an animated sequence featuring it, which you can see below.

Alan also told me that the animation shows more of the painting than was possible on the original White Dwarf cover. In addition, the animation corrects some color inaccuracies found in the print version, so, if you watch the video above, you're seeing the painting in its entirety, just as the artist intended it.March 17, 2024

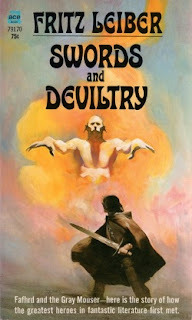

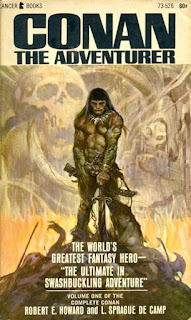

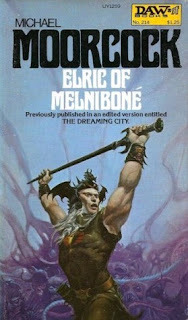

The Problem with Appendix N

Since its start sixteen(!) years ago this month, an overriding concern of this blog has been the literary inspirations of Dungeons & Dragons, particularly those stories and books belonging to what I call "pulp fantasy." Though there are several reasons why this topic has been of such interest to me, the primary one remains my sense that, in the decades since its initial publication in 1974, Dungeons & Dragons has moved conceptually ever farther away from its origins in the minds of Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax – and the works that inspired them.

Since its start sixteen(!) years ago this month, an overriding concern of this blog has been the literary inspirations of Dungeons & Dragons, particularly those stories and books belonging to what I call "pulp fantasy." Though there are several reasons why this topic has been of such interest to me, the primary one remains my sense that, in the decades since its initial publication in 1974, Dungeons & Dragons has moved conceptually ever farther away from its origins in the minds of Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax – and the works that inspired them.The argument can be made, of course, that this movement was, in fact, a good thing, as it broadened the appeal of both D&D and, by extension, roleplaying games as a hobby, thereby leading to their continued success half a century later. I have no interest in disputing this point of view at the present time, not least of all because it contains quite a bit of truth. My concern has rarely been about the merits of the shift, but rather about establishing that it occurred. To do that, one needs to recognize and understand the authors and books that inspired the game in the first place.

It's fortunate, then, that Gary Gygax was quite forthcoming about his literary inspirations, providing us with several different lists of the writers and literature that he considered to have been the most immediate influences upon him in his creation of the game. The most well-known of these lists is Appendix N of the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide. While I was not the first person to draw attention to the importance of Appendix N – Erik Mona, publisher of Paizo, springs immediately to mind as a noteworthy early advocate – it's no mere boast to suggest that Grognardia played a huge role in promoting Appendix N and its contents during the early days of the Old School Renaissance.

It's fortunate, then, that Gary Gygax was quite forthcoming about his literary inspirations, providing us with several different lists of the writers and literature that he considered to have been the most immediate influences upon him in his creation of the game. The most well-known of these lists is Appendix N of the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide. While I was not the first person to draw attention to the importance of Appendix N – Erik Mona, publisher of Paizo, springs immediately to mind as a noteworthy early advocate – it's no mere boast to suggest that Grognardia played a huge role in promoting Appendix N and its contents during the early days of the Old School Renaissance.So successful was that promotion that discussions of Appendix N proliferated well beyond this blog, to the point where, a decade and a half later, "Appendix N fantasy" has become almost a brand unto itself. One need only look at the Dungeon Crawl Classics RPG from Goodman Games to see a high-profile example of what I mean, though I could cite many others. If nothing else, it's a testament to just how inspiring others found the authors and books that had earlier inspired Gygax. There was clearly a hunger for a different kind of fantasy beyond the endless parade of Tolkien knock-offs Terry Brooks inaugurated (and that Dragonlance formally introduced into D&D).

Yet, for all that, Appendix N suffers from a very clear problem, one that has limited its utility as a guide for understanding Dungeons & Dragons as Gary Gygax understood it: it's just a list. Gygax, unfortunately, provides no commentary on any of the authors or works included in the list, stating only that those he included "were of particular inspiration" He later emphasizes that certain authors, like Fritz Leiber, Robert E. Howard, and H.P. Lovecraft, among others, played a stronger role in "help[ing] to shape the form of the game." Beyond these brief remarks, Gygax says nothing else about what he found inspirational in these books and authors or why he selected them over others he chose not to include.

Yet, for all that, Appendix N suffers from a very clear problem, one that has limited its utility as a guide for understanding Dungeons & Dragons as Gary Gygax understood it: it's just a list. Gygax, unfortunately, provides no commentary on any of the authors or works included in the list, stating only that those he included "were of particular inspiration" He later emphasizes that certain authors, like Fritz Leiber, Robert E. Howard, and H.P. Lovecraft, among others, played a stronger role in "help[ing] to shape the form of the game." Beyond these brief remarks, Gygax says nothing else about what he found inspirational in these books and authors or why he selected them over others he chose not to include.In addition, Appendix N is long, consisting of nearly thirty different authors and many more books. Drawing any firm conclusions about what Gygax saw in these works is not always easy, something that, in my opinion, might have been easier had the list been shorter and more focused. That's not to say it's impossible to get some sense of what Gygax liked and disliked in fantasy and how they impacted his vision for Dungeons & Dragons, but it's certainly harder than it needs to be.

Compare Gygax's Appendix N to the one found in RuneQuest. The list is about half as long (if you exclude other RPGs cited) and every entry is annotated, albeit briefly. Reading the RQ version of Appendix N, one has a very strong sense of not only why the authors found a book inspirational, but what each book inspired in them (and, thus, in RuneQuest). As much as I love Gygax's selection of authors and works, I can't help but think that selection would have proven more useful if he'd taken the time to elaborate, if only a little, on what he liked about its entries.

Compare Gygax's Appendix N to the one found in RuneQuest. The list is about half as long (if you exclude other RPGs cited) and every entry is annotated, albeit briefly. Reading the RQ version of Appendix N, one has a very strong sense of not only why the authors found a book inspirational, but what each book inspired in them (and, thus, in RuneQuest). As much as I love Gygax's selection of authors and works, I can't help but think that selection would have proven more useful if he'd taken the time to elaborate, if only a little, on what he liked about its entries.I found myself thinking about this recently, because I've been pondering the possibility of including an analog to Appendix N in Secrets of sha-Arthan . Since the game has a somewhat exotic setting that deviates from the standards of vanilla fantasy, I feel it might be helpful to point to pre-existing works of fantasy and science fiction (not to mention other roleplayng games) that inspired me as I developed the setting. That's why, if I do include a list of inspirations, it'll likely be both fairly short and annotated – closer to RuneQuest's Appendix N than to Gygax's.

None of this should be taken as a repudiation of Appendix N or the works included in it as vital to understanding Dungeons & Dragons and Gary Gygax's initial vision for it. I still think there is insight to be gleaned by reading and re-reading the works of pulp fantasy included in the appendix and will continue to recommend them to anyone who asks for recommendations of fantasy worthy of their time. Nor should any of the foregoing discourage anyone from taking the time to read Howard or Leiber or Lovecraft, as doing so is time well spent and more than sufficient reward in its own right. However, with some time and perspective, I recognize that Appendix N has certain shortcomings that can make it less than adequate as a guide to "what Dungeons & Dragons is about."

None of this should be taken as a repudiation of Appendix N or the works included in it as vital to understanding Dungeons & Dragons and Gary Gygax's initial vision for it. I still think there is insight to be gleaned by reading and re-reading the works of pulp fantasy included in the appendix and will continue to recommend them to anyone who asks for recommendations of fantasy worthy of their time. Nor should any of the foregoing discourage anyone from taking the time to read Howard or Leiber or Lovecraft, as doing so is time well spent and more than sufficient reward in its own right. However, with some time and perspective, I recognize that Appendix N has certain shortcomings that can make it less than adequate as a guide to "what Dungeons & Dragons is about."

January 25, 2024

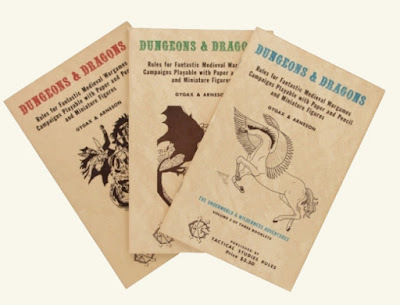

Fifty Years Ago Today

I'm very interested in the history of Dungeons & Dragons, but I'm not a historian – especially when compared to someone like Jon Peterson. Consequently, if Jon opines that January 26, 1974 is the day on which D&D was released – and, therefore, the game's birthday – I'm inclined to trust his judgment. So, happy birthday Dungeons & Dragons! For the last half-century, you've entertained untold millions of people across the globe, providing them with a delightful means to exercise their imaginations together with their friends.

I'm very interested in the history of Dungeons & Dragons, but I'm not a historian – especially when compared to someone like Jon Peterson. Consequently, if Jon opines that January 26, 1974 is the day on which D&D was released – and, therefore, the game's birthday – I'm inclined to trust his judgment. So, happy birthday Dungeons & Dragons! For the last half-century, you've entertained untold millions of people across the globe, providing them with a delightful means to exercise their imaginations together with their friends.

Dungeons & Dragons played an outsize role in popularizing fantasy literature, ideas, and themes, as well as inspiring many of its devotees to create their own. Roleplaying, as a formal activity, owes nearly its entire existence to the phenomenal success of D&D. Even more remarkable is the extent to which the computer and video game industry, which is bigger and more profitable than the music and movie industries combined, owes a huge debt to the example set by D&D. If you play any game with classes or levels or experience or hit points today, that's because of Dungeons & Dragons.

It's slightly crazy if you think about it. Two wargamers from the American Midwest created an entirely new type of entertainment, one that, over the course of five decades, changed the world forever. That's no small accomplishment – and it's certainly worth celebrating.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers