K. Rex Butts's Blog, page 7

March 29, 2023

Listening is Loving

Every day we encounter people who are hurting, living with grief and pain, a trauma that stems from suffering. As both a minister and one of those people who has suffered, one of the more frequent questions I get asked is about what we can do to help those who are hurting. Although there’s so much to say that space will not allow for, I do want to discuss one response concerning listening.

What I want to discuss stems from my experience as a minister of the gospel and my personal experience. Most people who know me also know that my wife and I lost our first child, Kenny, who unexpectedly passed away three days after his birth on August 2, 2002. Like anyone who suffers such a loss, the road of grief we have walked was very difficult but has eased in ways over the years.

More recently, I have started reading more about trauma and the way that trauma impacts the lives of people. The more I read about trauma and its impact on people, the more I realize that I’m also reading about my wife and me. The awareness of trauma wasn’t even on our horizon when our son passed away, but I can look back and see how traumatized we were (and sometimes still are). We’ve obviously survived, but I wonder if the journey of learning to live with grief would have been less difficult if we could have seen the trauma we were living with.

I say that because I also wonder how many others suffer in some way, whose suffering is even more difficult because they are unaware of how trauma affects their lives. I also wonder how much more difficult the suffering of others is because we don’t recognize and attend to the trauma affecting the lives of those who suffer.

When I speak of suffering, I do so broadly to include the death of children and the loss of others. People can also suffer from divorce, health problems, domestic abuse, poverty, racism, etc. Regardless of the source, the commonality of the suffering I have in mind is the kind that seemingly paralyzes a person’s life. The suffering is so profound that it consumes life in ways that words cannot adequately describe. As Billman and Migliore write, “Acute suffering creates an abyss of speechlessness for the person in pain.”1

Such suffering is the kind that can slowly destroy life. And yet, as I mentioned at the beginning, most of us probably encounter at least one person a day who is enduring this suffering. So what can we do? How can we attend to the trauma of suffering that others live with?

We don’t need a degree of any sort to listen…We just need the compassion that flows from the grace of God.

The answer begins with our ability to listen, which leads to empathy for those suffering and living with trauma. This listening posture is what Jennifer Baldwin describes as a “hermeneutic of empathy” that allows for understanding. Such empathy does not require us to share similar experiences of suffering. As Baldwin writes, “If we allow ourselves, we can feel into the affective experiences of people whose lives are very different than our own but with whom we share the common struggles of life, love, hope, faith, oppression, and survival.”2

Listening to understand and gain empathy is not always easy. Some people don’t listen well, period. Others may listen but want to solve the problem, compare one traumatic event with another, or even worse, theologize about God and the problem of evil. None of that is helpful. One thing we can learn from the book of Job is that his friends did well when they wept with Job and sat with him in his suffering. Everything went terrible the moment Job’s friends opened their mouths and began to theologize about his suffering.

Once we can learn to listen to understand and gain empathy, a new space opens. Baldwin writes:

When we can abide in and remain present to the realities of traumatic experience and response, we open a space of authentic compassion and care for the parts, individuals, and communities among us who viscerally know the pain of traumatic violation3

Being present in this manner means listening without judgment, even if we might disagree. Listening to understand and gain empathy does not require agreement on theology, politics, cultural issues, etc. What listening does is love. That is, when we listen and learn, we are loving and can learn ways we might love in other tangible ways.

I can’t speak for those who have endured terrific illness and injury or those who have experienced divorce, racism, etc. But I’m confident I can speak for everyone who has lost a child and say we never get over such a loss. We learn how to live with the loss of a child, which takes years because we don’t have any other choice if we’re to keep living. Along the way, I have had much help, and that help came from those who were willing to listen.

We don’t need a degree of any sort to listen in the manner I have described above. We just need the compassion that flows from the grace of God. And by the way, if we want people who suffer to really believe that God loves them and is with them in their suffering, then the onus is on us to be the listening presence of God.

1Kathleen D. Billman and Daniel L. Migliore, Rachel’s Cry: Prayer of Lamen and Rebirth of Hope, Cleveland: United Church Press, 1999, 105.

2Jennifer Baldwin, Trauma-Sensitive Theology: Thinking Theologically in the Era of Trauma, Eugene: Cascade Books, 2018, 87.

3Ibid, 121.

March 15, 2023

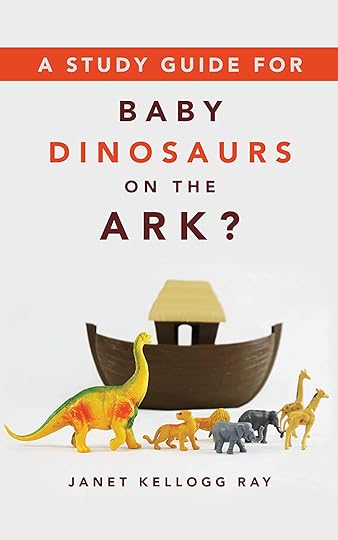

Baby Dinosaurs on the Ark?

“In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth,” says the Bible in Genesis 1:1.1 This claim is central to the Christian belief that God is the Creator of Life. This belief is also expressed in the earliest Christian creeds. For example, the Apostle’s Creed begins with the confession, “I believe in God, the Father Almighty, maker of the heaven and earth.” Similarly, the Nicene Creed begins with the confession, “We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible.”

Beyond acknowledging God as the Creator, neither the Apostle’s Creed nor the Nicene Creed says anything about when or how God went about creating. Certainly not a word is said that offers a scientific explanation as to the formation process of creation and how creation went from its beginning to its current state. Some Christians may already want to object with a question about what the rest of the Genesis creation narrative says. Fair enough, but I don’t believe the purpose of the Genesis creation narrative was ever intended to be a scientific account of how creation came into existence, though I know there are Christians who will disagree. In a nutshell, my own view is that the purpose of the Genesis creation narrative is theological in that it is intended to convey who created us and for what purpose.2

My intent here is not to discuss the merits of interpreting the Genesis creation narrative and the issues associated with the text. I began with a mention of the two earliest Christian creeds to say that I believe it is possible and permissible for Christians to hold different beliefs on questions such as how old the earth is, whether the seven days of creation are literal or not, and so forth. What I dislike is the notion that people must choose between science and the Christian faith, as though one cannot accept the theories of modern science and believe in the Christian faith.

It is a false dichotomy to think that people must choose between science and the Christian faith. Whether or not you agree with every biological theory commonly accepted by most scientists, it is more than possible to accept the science and still be a Christian. My dislike for the false dichotomy stems from knowing young Christians who struggled with faith, sometimes losing their faith because they found the scientific evidence very credible but could not reconcile that evidence with the way they were taught to read the Genesis creation narrative as a literal-scientific and anti-evolution text that demands a Young Earth Creationist belief (creationism). For this reason, I really recommend reading Baby Dinosaurs on the Ark? by Janet Kellog Ray.3

I first read Ray’s book shortly after it was published because the subject matter interests me. The author is a science educator who teaches at the University of North Texas in Denton, Texas, one who accepts the scientific evidence for evolution and is a Christian. Throughout the book, Ray explains what science is and what it does and corrects misconceptions about science and scientific evidence.

The book also engages the different theories for the origins of creation and how it’s possible to reject creationism without rejecting God. On the second to last page, Ray writes:

Trying to force a modern understanding of science into an ancient document misses lots of boats. No only do we miss the message intended by the origional authors and compilers, we also force the Bible to be something it is not—a scientifically accurate natural history of the earth. When we read Genesis, we don’t learn about modern science, but we do learn about God.4

Whether or not you accept every claim made by modern science, what Ray said is spot on.

If this is an issue that is of interest to you, then get her book and read it. But there is more because Eerdmans Publishing has just released a study guide for this book.5 Each chapter highlights the points made by Ray in each chapter of the original book but also includes discussion questions followed by a small expansion on the topic that will allow for further reflection on the content. The study guide is intended for facilitating discussions, whether that be in a small group, Bible class, etc…

Anyway, if you haven’t already, I hope you will purchase both Baby Dinosaurs on the Ark? and A Study Guide for Baby Dinosaurs on the Ark?.

1The Holy Bible, New International Version, NIV. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

2Two books I recommend reading are: 1) John H. Walton, The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate, Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2009; Francis S. Collins, The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief, New York: Free Press, 2007.

3Janet Kellog Ray, Baby Dinosaurs on the Ark?: The Bible and Modern Science and the Trouble of Making It All Fit, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2021.

4Ibid, 184.

5_____. A Study Guide for Baby Dinosaurs on the Ark?, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2023.

February 27, 2023

By The Spirit

I finished up a sermon series called Christ-Formed from Galatians this past Sunday. As I mentioned in each sermon, Paul writes, “My dear children, for whom I am again in the pains of childbirth until Christ is formed in you” (Gal 4:19).1 Christians, as people justified by faith and baptized into Christ, are adopted into a new life shaped by Jesus Christ's life.

Learning to live as Christ-formed people is a matter of discipleship, sometimes called spiritual formation. I actually prefer the phrase life formation because this formation is a claim upon our entire life. This is also why the Holy Spirit matters to our lives as Christians.

If we ask the question of how we are formed in Christ, the simple answer is probably to hear Paul saying, “Since we live by the Spirit, let us keep in step with the Spirit” (Gal 5:25). We can trust that living by the Spirit will result in our formation in Christ because God’s Holy Spirit is never going to lead us in any other life than that revealed to us in Jesus Christ.

This means that over time, as we live by the Spirit, our lives should reflect the life that Jesus Christ lived, with all of the values that characterize the life of Jesus Christ. In particular, this includes the logic of the cross that Christ embraced. So like Christ, we learn to serve and even suffer for the sake of others, extending God’s gracious hospitality to everyone just like Christ. Now if only it was that simple. But it’s not, so we need to start with an understanding of our freedom in Christ.2

The gospel Jesus proclaimed was the good news of God’s kingdom at hand. In proclaiming the kingdom of God, Jesus has called us to follow him in living under God’s governance again rather than our own rule.

According to Paul, “It is for freedom that Christ has set us free” (Gal 5:1). Paul is responding to those Jewish believers who insist that living in a right relationship with God (justification) requires adherence to the Law of Moses. If the question is whether people must be circumcized to live in a right relationship with God, then Paul’s response is a “No!” Christians are not obligated by the requirements of the Law anymore. By extension, Christians are not bound by legalistic expressions of Christianity either. There is always a temptation to reduce the Christian Faith to a set of rules, even proof-texting the Bible as necessary, in order to say what Christians can and cannot do and then use that legalistic reduction to judge the faith of other Christians. Then anyone who doesn’t understand and practice the Christian faith according to the reduction appears guilty of turning to another gospel.3 The irony is that it’s this sort of sectarian legalism that Paul has declared as another gospel.

I don’t want to leave the impression that Christian doctrine is unimportant and doesn’t matter. What matters is remembering that we are free from the trapping of sectarian legalism in Christ. However, our freedom is not a license to indulge whatever desires we have. In fact, the idea of freedom in Christ is not our individual right to determine for ourselves what is right and wrong, and therefore live however we like. I know our society thinks of freedom as the right to self-determination, but that’s actually a form of slavery because God never created us to live as our own governors. In fact, going back to Genesis 3, we see that what Adam and Eve sought was the ability to gain knowledge of what’s good and evil for themselves. Instead of trusting God to determine what is good and evil, they sought that power for themselves—to their own peril. So it is a mistake to think we are free to rule ourselves. The gospel Jesus proclaimed was the good news of God’s kingdom at hand. In proclaiming the kingdom of God, Jesus has called us to follow him in living under God’s governance again rather than our own rule.

The way that God’s governance works is that God gives us his Holy Spirit to walk by. That’s why Paul writes, “Walk by the Spirit, and you will not gratify the desires of your flesh” (Gal 5:16) The language of walking by the Spirit is about letting the Spirit determine how we live our lives.4 However, in order to walk by the Spirit, we have to give our attention to the Spirit.

The word for Spirit in Hebrew is ru’ach, which also means “wind”. So if we think about the Holy Spirit as a wind that’s blowing, the image of sailing might help us think about how we give our attention to the Spirit. think with me for a moment about wind and sailing. Sailing requires putting the sails into the wind to catch the wind so the boat will sail. So it is in walking by the Spirit. That is, we have to put our sails, so to speak, into the Spirit and catch the Spirit. If we’ll position ourselves to catch the Spirit, our lives will reflect Christ and produce the fruit of the Spirit (Gal 5:22-23).

The choice we are faced with is whether we want a Christ-formed life or not. Assuming we do, we must ask what kind of spirit we position our lives to catch. If we want to position our lives to catch the Holy Spirit, then we have to attend to the work of the Holy Spirit, which means disciplining ourselves to spend time in prayer, taking time to read and dwell upon scripture, and giving ourselves time for reflection on our lives. It’s in such times that we are able to discern those aspects of our lives that still need to be transformed by the Spirit into Christ-likeness.

So I close with one question: How are we attending to the work of the Holy Spirit?

1Unless otherwise noted, all scripture quotations are from The Holy Bible, New International Version, NIV. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

2James D.G. Dunn, The Epistle to the Galatians, Black’s New Testament Commentaries, Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 1993, 286-287, notes that the point Paul “wished to bring out was that the call to freedom was a call not merely from the older enslavement, but also a call to a new responsibility.”

3For example, see Alisa Childers, Another Gospel?: A Lifelong Christian Seeks Truth in Response to Progressive Christianity, Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale, 2020. I share some of the same concerns the author has for some of the teaching coming from so-called progressive/liberal Christianity, but the author’s rigid dogma that reflects the traditional evangelical/conservative Christianity has problems too. Perhaps it would be better for all Christians, including progressives and evangelicals, to hold their doctrine with both humility and a charitable disposition. For the moment we make our understanding of biblical doctrine a de facto requirement to being a true Christian, then we are adding to the gospel and then indeed proclaiming another gospel.

4F.F. Bruce, The Epistle to the Galatians, The New International Greek Testament Commentary, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1982, 243.

February 6, 2023

Baptized Into Christ

To find ourselves justified by faith in Christ means our lives are now located among God’s new creation. Yet history has shown the struggle to grasp what it means for the church to live as participants in God’s new creation rather than continuing in the ways of the old creation.

In the New Testament writing of Galatians, part of the struggle was with Jewish believers struggling with the implications of being justified by faith in Christ. Consequently, instead of living as people in God’s new creation, these Jewish believers returned to the old creation by submitting again to the Torah. In particular, they taught that living in a right relationship with God (justification) required circumcision. So Galatians is Paul’s response and corrective instruction. According to Paul, “Neither circumcision nor uncircumcision means anything; what counts is the new creation.”1

Justification by faith in Christ is redemption into God’s future of new creation rather than the past of the old creation. However, to understand the implications, we have to go back and read a passage from Galatians 3:26-28:

So in Christ Jesus you are all children of God through faith, for all of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male nor female, for you are all one in Christ.

Paul’s language of being baptized into Christ is locative language. As baptized people, the church, as I have already pointed out, lives among God’s new creation. Consequently, the church must live as a witness to this future where the boundaries of ethnicity, social status, and gender no longer define participation.2 However, too often, Christians have struggled with and even failed to embody the implications of this text in various ways.

The Galatians text offers an example of one early church struggling to live out the implications. In Galatians 2:11-14, Paul writes about confronting the apostle Peter (Cephas) over his failure to embody the implications. When we read about the history of Western civilization and Christianity in the Western church, both Catholic and Protestant, the reality of colocalization and slavery is another example of how Christians have returned to the old creation rather than living as a witness of God’s new creation.

All believers baptized into Christ have received the Spirit who empowers them to serve equally within the church. It also seems clear, based on observation, that God has gifted some women to preach, teach, pastor, and lead others in the way of Jesus Christ.

One of the ways that Christians have failed to embody the implications of our baptism described in Galatians 3 is by allowing ethnicity, social status, and gender to decide whom God has gifted to serve in ministry. In 1857, a Black Christian named Peter Lowery planted the first Black congregation in Nashville associated with the Stone-Campbell Restoration Movement. In doing so, Lowery had to petition the city council for permission to hold church services in the evening. The council’s response was to unanimously deny the petition because nothing good came “from negro preaching.” The reason was that “Negro preachers could not explain the fundamental principles of Christianity; they were not competent.”3 It’s safe to assume that at least some of the city council members identified as Christians. Yet for the council members, Lowery’s race, rather than his baptism (and presumably their baptisms), was the determining factor in his ability to serve as a church-planting minister.

It’s easy to see the racism at work in the case of Peter Lowery. Today we know that a person’s race and ethnicity have nothing to do with whom God has to serve as a minister of the gospel. Whether our ancestry is African, Asian, or European origin or some combination, we know that God is impartial in gifting people to serve in ministry. So when we see that the Spirit has gifted someone to preach, teach, pastor, and lead others in the way of Jesus Christ, we affirm their calling regardless of race and ethnicity.

The same affirmation of a calling to ministry falls short regarding gender. In many churches, a person’s gender is the basis for determining how the Spirit has gifted someone to serve. If a person is a male, they may serve without restriction, but if the person is a female, their gender precludes them from serving in some or all aspects of ministry. So some Christians are seemingly incapable of even recognizing when the Spirit is gifting a woman to serve in ministry because they have already concluded that God would never gift a woman to preach, teach, pastor, and lead others in the way of Jesus Christ. The problem is the same as in the case of Peter Lowery, with the only difference being gender instead of racism.

The baptismal claim of Galatians 3 is that ethnicity, social status, and gender are now relativized.4 The coming of Christ and subsequently the outpouring of the Holy Spirit on all flesh (cf. Acts 2:17-21) has changed everything because the eschatological future of God's new creation is now breaking into the present. All believers baptized into Christ have received the Spirit who empowers them to serve equally within the church. It also seems clear, based on observation, that God has gifted some women to preach, teach, pastor, and lead others in the way of Jesus Christ. That is unless we don't begin with the premise of old creation where gender determines how the Spirit gifts men and women for ministry.

I realize that one single post on this matter leaves many questions unanswered. Some will try making the creation order in Genesis 1-2 carry more freight than initially intended to dismiss any possibility that God might raise a woman in Christ to preach. Some will immediately recall texts like 1 Corinthians 14:34-35 and 1 Timothy 2:11-12 as proof-texts to counter any claim of accepting the full participation of women in Christian ministry.5 Before rushing to such proof texts, remember that it's easy to make the Bible justify a reality rooted in the old creation. White slave owners did so with slavery and racism, and we can do so in other ways that pertain to gender. My hope is that we could look at this matter through the theological lens of what has changed in the coming of Christ.

1Unless otherwise noted, all scripture quotations are from The Holy Bible, New International Version, NIV. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

2Richard B. Hays, The Moral Vision of the New Testament: Community, Cross, and New Creation: A Contemporary Introduction to New Testament Ethics, New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1996, 440.

3“City Council,” Republican Banner, May 29, 1857. I am indebted to John Mark Hicks for sharing this source on his Facebook wall on Friday, February 3, 2023 (last accessed on Monday, February 6, 2023).

4James D.G. Dunn, The Epistle to the Galatians, Black’s New Testament Commentaries, Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 1993, 197, points out that the claim of the text is not that a person’s description as a Jew or Gentile, male or female, slave or free is vanquished but rather that they are relativized and therefore cannot be used to define status, worth, value, or privilege.

5K. Rex Butts, Gospel Portraits: Reading Scripture as Participants in the Mission of God, Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2022. I address the subject matter of women serving in ministry at more length in the final chapter of this book, titled “The Spirit-Filled Church.”

January 30, 2023

A Eulogy

Recently a woman who was part of the Newark Church of Christ, whom I serve with as the lead minister/pastor, passed away. Her death was sudden, unexpected, and tragic, especially considering that she still had much life to live. As a minister, I was asked to speak the eulogy at her memorial service. So what do you say to a husband, a mother, two children, a sister, cousins, friends and co-workers, and many fellow Christians who are gathered to remember and honor the life of someone they love?

The following is the manuscript of the eulogy I shared at the memorial service.

Anita and I had at least two things in life that we held in common. First, we both were born in Arkansas. And yes, that matters. Last year, when Anita took a trip to Arkansas with her mother, Frances, she posted a picture on Facebook of an Arkansas field with the comment saying, “That right there’s some good dirt, y’all!”

I’ll confess, I was envious.

But more importantly, Anita and I are brother and sister. Now that might have some of you scratching your heads because I certainly wasn’t mentioned as a sibling in her obituary. But we are siblings, bound together as brother and sister in Christ because I’m a Christian, and so is Anita. So for the rest of you who are Christians, Anita is your sister in Christ too.

Now you might have noticed that I’m using the present tense, even to speak about Anita. That’s not a mistake on my part. It’s intentional because it has everything to do with the Christian faith that Anita lives her life by.

When John, Anita’s husband, asked me to speak at this memorial service, he asked me to share a message about the Christian faith. So I intend to do just that, even as I share a message about the life that Anita lives.

So I want to read a passage from the New Testament writing of Romans chapter 8, but before I do, I want to explain why I’m reading a passage from Romans. The reason is that in Anita’s Bible, at the top of Romans chapter 8, she had a note written to write a book about Romans 8. Although Anita never got the chance to write that book, she is living the claims of Romans 8.

Starting in v. 22, the apostle Paul writes in Romans 8, “We know that the whole creation has been groaning together as it suffers together the pains of labor, and not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly while we wait for adoption, the redemption of our bodies. For in hope we were saved. Now hope that is seen is not hope, for who hopes for what one already sees? But if we hope for what we do not see, we wait for it with patience.”1

Romans 8 is bookended by two particular claims about the promise of salvation that God is bringing about in Christ. First, there isn’t any condemnation for those in Christ. And secondly, nothing can separate us from the love of God because we are more than conquerors in Christ.

These claims are important to remember as we think about the hope that Paul speaks of in this passage I read just a few moments ago.

Our hope is the assurance in Christ that God will save. Such hope is the promise of what we wait for, the “adoption, the redemption of our bodies.” But it’s a hope that groans because it’s lived in a life that comes with struggles—sufferings.

Those who know Anita’s story know that she had struggles in life, but she never gave up her Christian faith and the hope in Christ that is held onto by faith. That’s important to know because I know that Anita’s passing is difficult. Anita was still in the prime of her life, just having recently completed her Master’s of Library Science and Information degree. So her passing is a tremendous grief.

I need to say something about such grief because Anita’s family—especially her husband John, her children Clayton and Claire, her mother Frances, and her sister Dana—must bear this grief. Nothing that I or anyone else says will make the grief any less. And I’m saying that from my own personal experience of losing a child. People ask me what they can say to someone grieving. Just say, “I’m sorry,” but don’t say anything to try to make the passing of Anita less difficult because it doesn’t work. Don’t say things like, “Well, God just needed another angel.” First of all, Anita’s not an angel. Anita is Anita. And secondly, there’s a family sitting right here who still needs her. Also, y’all need to know that people don’t get over grief. People can learn to live with grief, but that takes time, time as in months and even years. So give John, Clayton and Claire, Frances, Dana, and the rest of the family some grace and be merciful, because the road ahead will still be difficult.

When I speak of learning how to live with grief, I’m also talking about learning how to live by faith with hope in Christ. It’s the same hope that Anita has lived with. It’s a hope rooted in the crucified and resurrected Jesus Christ. You see, Jesus Christ has already come and suffered death himself upon the cross, but God the Father didn’t abandon his Son to death. Rather, God raised Jesus from death, and so his crucifixion and resurrection stand as the promise of salvation.

This promise of salvation isn’t just some ethereal eternal life that’s disembodied from who we are as human beings. Paul describes this hope that we wait for as “the redemption of our bodies.” Over in 1 Corinthians 15, Paul speaks of a bodily resurrection, and the reason he does so is because Jesus was raised in bodily form as well.

Now I don’t know exactly what our resurrected bodies will be like, but I know that the first disciples recognized Jesus as Jesus after his resurrection. So I’m confident in saying that we who put our hope in Christ will not only see Jesus face to face and recognize him as the man named Jesus but on that day when Christ comes again and raises to eternal life his followers, we’ll see Anita again and recognize her as the person we know as Anita.

This is why I speak of Anita in the present. Her passing is not the final scene of her life. She’s resting in the Lord, Jesus Christ, as we speak. And when not if but when Jesus comes again, Anita will rise into this eternal life that she has been living by the power of God’s Spirit.

This is the hope of Christ that Anita has lived her life with. I know that this hope doesn’t make her passing easy. I grieve with all of you. We lost a beautiful woman, and I don’t want to downplay the grief that Anita’s passing brings, not one bit. But I also know that to honor Anita’s life, we need to consider the hope that has kept her going.

Death is a terrible thing that we all must live with, but it’s not the final chapter of life. Resurrection is, and it’s a chapter without end. It’s the hope that Paul says, “we wait for it with patience.” Sometimes that seems impossible, but by the grace of God, we can just as Anita has done.

Earlier today, I took some time just to listen to a rather new song called the Hymn of Heaven, which is written by Phil Wickman. The words of the chorus go…

There will be a day when all will bow before Him

There will be a day when death will be no more

Standing face to face with He who died and rose again

Holy, holy is the Lord

But it’s the words to the third verse that really has my attention…

And on that day, we join the resurrection

And stand beside the heroes of the faith

With one voice, a thousand generations

Sing, "Worthy is the Lamb who was slain”

"Forever He shall reign"

And with hope in Christ, among those heroes of the faith singing the hymn of heaven is Mrs. Anita Delp.

Almighty God, we remember before you today your faithful servant Anita; and we pray that, having opened to Anita the gift of eternal life, you will receive her more and more into your joyful presence, that, with all who have faithfully served you in the past, Anita may share in the eternal victory of Jesus Christ our Lord; who lives and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, on God, forever and ever. Amen. 2

1Unless otherwise noted, all scripture quotations are taken from the New Revised Standard Version, copyright 1989. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

2Adapted from Episcopal Church, The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, Together with the Psalter or Psalms of David According to the Use of the Episcopal Church, New York :Seabury Press, 1979, 253.

January 23, 2023

Prayer Works?

By now, most people are familiar with the terrible injury that Buffalo Bills Safety, Damar Hamlin, suffered in a game against the Cincinnati Bengals. Suffering cardiac arrest after a legal football hit and nearly dying was terrible. NFL player or not, Hamlin is a young man, and it would have been tragic for him to die.

Fortunately, Damar Hamlin received excellent medical treatment and appeared to be on the road to a full recovery. More importantly, many people were praying for Hamlin’s healing. Even Dan Orlovsky, a former NFL Quarterback and current NFL Analyst for ESPN offered an intercessory prayer for Hamlin on live television. It’s nice to see so many people praying, not only because that is something we should do for others in need but also because people recognize that we mortal humans need God. However, once it became clear that Damar Hamlin was likely to recover, I began reading posts and comments on social media that claimed Hamlin’s recovery was proof that prayer works. This is a problem.

When we respond to a situation like Damar Hamlin’s injury and recovery, saying this is proof that prayer works, we immediately create another problem. If this is how we know that prayer works, why has prayer not worked for the many women who have had difficulty conceiving children and have even miscarried the children they did conceive? Or, if getting well after people pray proves that prayer works, why does prayer not work for some of the children with cancer who will never live to see adulthood?

Pointing to someone who has recovered from an illness or injury as proof that prayer works can be an existential problem for the suffering. However, such a claim is also a theological problem because to speak about prayer working is to talk about the work of God. So when we say that someone’s remarkable recovery is proof that prayer works while knowing that there are other people who others are praying for but do not recover, it then appears that the work of God is either by arbitrary choice or limited in power. That means God either shows favoritism or is not sovereign, which creates a big theological problem. This is why there are scores of books written on theodicy in which philosophers and theologians attempt to account for the existence of a benevolent God and human suffering.

I don’t have an answer to why a loving God allows suffering, and if I’m pressed, I can demonstrate why I don’t believe a good answer exists. However, I think there is an answer to whether prayer works, an answer that affirms prayer does work but perhaps differently than we may assume. So, I want to ask: How does God work for his redemptive purpose through faith expressed in prayer?

Psalms 42 and 43 are connected prayers. However, the Psalmist wonders where God is rather than expressing a robust assurance of God’s presence. The Psalmist prays, “My soul thirsts for God, for the living God. When can I go and meet with God?” (42:2).1 Right now, the only thing that seems to keep the Psalmist living is his tears, which he describes as his food (42:3). Whatever is going on in the life of the Psalmist, there is despair and even doubt that we should not ignore. The despair and doubt seem so pervasive that the Psalmist prays to God, “why have you forgotten me? Why must I go about mourning, oppressed by the enemy?” (42:9).

Prayer works because, as an act of faith, we entrust our lives to God's loving care even when we have doubts and struggle to make sense of life. Prayer works because we entrust ourselves to the providential care of God, who is redemptively working life for the good through his Son, Jesus Christ—crucified, resurrected, and exalted as our Lord and Savior.

I can relate to the Psalmist because this is how I felt after my son passed away. The best way to describe how I felt was to say I was lost. My wife and I, along with many others, prayed for our son, yet he still died. In some sense, I felt betrayed by God, and as time passed, I became so tired that I just wanted to give up believing God cared. I couldn’t make sense of God or why God seemingly didn’t answer the prayers for our son.2

Randy Harris says, “Sometimes to walk in faith is to walk in deep darkness.”3 In fact, it doesn’t take much faith to keep trusting God when there isn’t push challenging that trust. On the other hand, it takes a lot of faith to trust when life is consumed by grief that becomes darkness. The faith that walks in darkness may have doubts, but it’s still faith. In The opposite of faith is neither doubts nor the laments one dares to utter amid the darkness. Instead, the opposite of faith may be apathy. It’s okay to have doubts and complaints.

It takes courageous faith to express such doubts and laments in prayer, wrestling with the tension created when faith collides with suffering. This collision is a disturbance within our souls even as we are trying to hold on to hope. We can hear the Psalmist wrestling with the tension in the refrain, as the Psalmist expresses the refrain three times, “Why, my soul, are you downcast? Why so disturbed within me? Put your hope in God, for I will yet praise him, my Savior and my God.” (42:5, 11; 43:5).4 I propose that this refrain is where we begin understanding how prayer works.

In Psalms 42 and 43, we have an expression of faithful lament, which is a protest or complaint that always hopes. The hope of lament is for God to respond to the reality of suffering.5 It is from the depths of darkness that the Psalmist calls out to God. “Deep calls to deep…” (42:7), the Psalmist prays. Even from the depths of his despair, the Psalmist knows his prayers will reach the depths of God’s great power. God is still sovereign, and God is still redemptively at work. So this Psalm offers us a voice for entrusting ourselves in prayer to God, reminding us to put our hope in God.

Psalms 42 and 43 don’t offer any particulars as to what prayer might do. Instead, the Psalmist trusts God enough to say, “Send me your light and your faithful care, let them lead me; let them bring me to your holy mountain, to the place where you dwell. Then I will go to the altar of God, to God, my joy and my delight.” (43:3-4).

Here is what prayer does ad how prayer works. Praying is not about trusting God. Even when prayer is a lament expressing anger, despair, and grief that trouble us to the very core of our beings, prayer works. Prayer works because we trust in God. Prayer works because we express faith in God still at work. Prayer works because, as an act of faith, we entrust our lives to God's loving care even when we have doubts and struggle to make sense of life. Prayer works because we entrust ourselves to the providential care of God, who is redemptively working life for the good through his Son, Jesus Christ—crucified, resurrected, and exalted as our Lord and Savior.

A mature faith, according to Tomáš Halík, “takes seriously the human experience of the tragedy and pain…”6 Prayer is a way in which we take seriously the reality of suffering and the trauma that follows, even when the only prayer we have is a lament. Prayer allows us to continue entrusting ourselves to God in his "steadfast love" (NRSV). That's also why I keep praying, for praying keeps me holding on to hope in Christ even if some days I feel like I'm barely clinging to hope. If you're living with grief and pain, I hope you'll entrust yourself to God by praying, even if it's just a simple "Lord, have mercy on me, a sinner" or just a lament, just to be silent with God and let him tend to your soul.

1Unless otherwise noted, all scripture quotations are from The Holy Bible, New International Version, NIV. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

2I share the story of my son’s death and the journey to a renewed hope in a chapter titled “Lost Sons,” see John Mark Hicks, Christine Fox Parker, and Bobby Valentine, eds., Surrendering to Hope: Guidance for the Broken, Abilene: Leafwood Publishers, 2018.

3Randy Harris, Soul Work: Confessions of a Part-Time Monk, Abilene: Leafwood Publishers, 2011, 33.

4This refrain gives a structure that involves two expressions of lament or complaint that leads to the recognition of hope. For more on the structure of Psalms 42 and 43, see Mitchell Dahood, Psalms I: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, vol. 16, The Anchor Bible, New York: Double Day, 1965, 255; Bernhard W. Anderson, Out of the Depths: The Psalms Speak For Us Today, 3rd ed., Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2000, 66.

5Soong-Chan Rah, Prophetic Lament: A Call for Justice in Troubled Times, Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2015, 21.

6Tomáš Halík, Patience with God: The Story of Zacchaeus Continuing In Us, trans. Gerald Turner, New York: Double Day, 2009, 108.

January 10, 2023

Mature Faith

“God is good all the time. All the time, God is good.” Except there are times when it doesn’t seem like God is good. Not when I’m walking through the pediatric oncology ward, not when I read news reports of war where innocent civilians are killed, not when I hear the story of a woman in my office discussing her life which began a descent into trouble when she was sexually abused as a child, and not when my memory takes me back to the day when my oldest son took his final breath.

Please understand me. I am not denying the goodness of God and would never do so because I believe God is good. But in life there are times when God seems anything but good.

One of my favorite lines in the Psalter reads, “You kept my eyes from closing; I was too troubled to speak” (Ps 77:4).1 You may understand because you have experienced such troubling times yourself. On any given day I imagine we encounter people who are so troubled that they cannot speak. At least, too troubled to express the pain they are bearing, and perhaps so because they’re not sure if anyone would care to listen. So, with great courage, they put on the mask of a smiling face in order to pretend like all is well when it’s not.

As both a pastor and one who has lived through my own grief and pain, I have tried to be a voice for those who are too troubled to speak. Sometimes I am able to do this, while other times, I am too troubled to speak for myself. But let me give it a try.

God is good and one of the reasons God is good is that he’s big enough to handle our disappointments and doubts as well as our fear and frustrations.

A mature faith, as Tomáš Halík, writes, “takes seriously the human experience of the tragedy and pain” and does so “without belittling it with facile religious comforts.”2 But how can we take seriously the experiences of suffering that others bear if we’re unwilling to listen, be present with them in such grief and pain without trying to counter their anger, bewilderment, and doubts with pious sentiments meant to bolster faith but actually only dismissing the faith expressed by the suffering?

If we want people to trust God in the midst of suffering, then the best thing we can do is create space for them to feel safe in expressing their grief and pain. We create such space by listening without passing judgment or needing to correct anyything said that we might sound somewhat impious. This is a time for empathy, which is a way of carrying the burden of someone else’s suffering (cf. Gal 6:2).

Halík, who I quoted earlier, goes on to say, “Mature belief is patient dwelling in the night of mystery.”3 If we truly have a solid faith in God then we are more than capable of sitting with the disruption of any uncertainty others have. In fact, those who must always assert a statement of faith to someone's doubts in the midst of suffering are probably showing their own lack of faith.

God is good and one of the reasons God is good is that he’s big enough to handle our disappointments and doubts as well as our fear and frustrations. God is big enough because the crucified, resurrected, and exalted Christ in whom God has revealed himself is our assurance. So for the people struggling in your church, in your community, or whoever God entrusts to your presence, listen and give them the space not to be okay, to question God, and to express their doubts as an act of faith. In doing so, God just might work through you to lead someone through the chasm that exists between a faith lingering in despair and a faith renewed in hope.

1Unless otherwise noted, all scripture quotations are from The Holy Bible, New International Version, NIV. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

2Tomáš Halík, Patience with God: The Story of Zacchaeus Continuing In Us, trans. Gerald Turner, New York: Double Day, 2009, 108.

3Ibid.

December 20, 2022

Advent: Peace

Phillip Brooks was the Episcopalian priest who wrote the words to O Little Town of Bethlehem in 1868. This hymn reminds us of the salvation that first appears to us in the birth of Christ, who was named Jesus. God is now with us in this child called Immanuel, meeting our hopes and fears with peace.

Peace, however, can mean a lot of things these days. No more wars, no more fighting, and “Smile on your brother, everybody get together, try to love one another right now.”1 Or it’s just another word that means very little at all.

For Israel, the word “peace,” shälōm in Hebrew, has in mind a well-lived life. To have shälōm is not just to have a life free of violence and conflict but also a healthy and prosperous life. And unless I’m woefully mistaken, we all want this kind of peace. I’ve never met anyone who wants their life to turn out terrible.

In the United States, we stress the importance of doing well in school and eventually getting a good job. Ideally, a good education lead will lead to a good-paying job with all the necessary benefits for living a prosperous life—shälōm—until it doesn’t. What I mean is that most of us have had the privilege to obtain whatever education we sought and land a decent-paying job. Beyond our education and careers, we have more restaurants than we could ever eat at in a week and streaming apps that can deliver more music and cinematic entertainment than we could ever consume. If we’re honest, most of us live in bigger homes than we need and drive nicer vehicles than we need. Yet a Gallup poll released last February found that only 38 percent of Americans are satisfied; before the pandemic, that percentage was only 48 percent.2

The Incarnation is a new beginning because the redemption of God is now at hand in Christ. God’s peace is coming upon us because God’s peace is dwelling among us in Jesus Christ.

There are many reasons for such dissatisfaction, so we can’t blame the pandemic entirely. Also, I’m not trying to be critical of people who are struggling, but I think we need to remember that the peace we seek is found in Christ. It’s easy to forget this and seek peace elsewhere, in other entities—for example, the pursuit of education and jobs. Neither education nor a job is inherently wrong, but when we think they will bring a prosperous life, it becomes idolatry.

Idolatry, at its root, elevates creation above the creator.3 Micah knows that idolatry is a hopeless endeavor. Whether the idol has the form of a golden statue or just a portrait of Benjamin Franklin on a hundred-dollar bill, Micah knows idolatry is dire. So Micah wants to remind us from whom we find peace. According to the prophet, there is a ruler to come. So Micah says, “And he shall stand and feed his flock in the strength of the Lord, in the majesty of the name of the Lord his God. And they shall live secure, for now he shall be great to the ends of the earth; and he shall be the one of peace” (Mic 5:4-5).4

As Christians, we believe this ruler is Jesus Christ. In Advent, we remember, as we sing in the hymn Hark! The Herald Angels Sing, “Glory to the Newborn King, peace on earth and mercy mild, God and sinners reconciled.”

In his book Counterfeit Gods, Timothy Keller defines idolatry as “anything more important to you than God, anything that absorbs your heart and imagination more than God, anything you seek to give you what only God can give.”5 Now, if we’re honest, we all, at various times, make something other than God more important, allowing our hearts to be absorbed by that something because we think it will make life more enjoyable. Yet that peace comes only from God through his Son, who is born among us in the person of Jesus.

The Gospel of Matthew says that Jesus will also be called Immanuel, which means “God with us” (Matt 1:23). The Advent story does not say, “Come get right with God if you want peace.” It’s quite the opposite. The Advent story says that God comes to us in Jesus Christ. God is making the move in this story, and his move is made to dwell among us so that we can receive this peace, this shälōm, ourselves.

We’re less than a week away from Christmas, a day when we remember the birth of Jesus. The birth of a child is, in a sense, the beginning of new life. And so it is with Jesus for all of us. The Incarnation is a new beginning because the redemption of God is now at hand in Christ. God’s peace is coming upon us because God’s peace is dwelling among us in Jesus Christ.

So this Christmas and into the new year of 2023, if we feel like we’ve lost sight of God and placed something else above God, let God restore our vision. Let God refocus our attention on Jesus. Let Advent be an invitation to start following Jesus again and walk with Jesus into his peaceable kingdom.

Glory be to God the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit, as it was in the beginning, is now, and will be forever, world without end. Amen!

1“Get Together,” Music and Lyrics by Chet Powers, Performed by the Youngbloods, 1966.

2Harry Enten, “American happiness hits record lows,” CNN, February 2, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2022/02/02/politics/unhappiness-americans-gallup-analysis/index.html (accessed on Friday, December 16, 2020).

3Vinoth Ramachandra, Gods That Fail: Modern Idolatry and Christian Mission, rev. ed., Eugene: Wipf and Stock, 2016, 104.

4All scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version, Updated Edition Bible, copyright © 1989, 2021 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A., and are used by permission. All rights reserved.

5Tim Keller, Counterfeit Gods: The Empty Promises of Money, Sex, and Power, and the Only Hope that Matters, New York City: Penguin Books, 2009, xix.

December 14, 2022

Advent: Joy

I recently picked up a copy of C.S. Lewis’s little book called A Grief Observed, in which Lewis reflects on his grief after his wife passed away due to cancer. Lewis begins with the observation that grief feels like fear. C.S. Lewis means that grief creates this paralyzing emotion that seems bereft of hope. Such grief becomes so pervasive that something as simple as taking a shower can feel like an arduous chore.

In today’s parlance, we speak of fear as depression, which many of us can identify with. The source of such fear, or depression, will differ. For Lewis, it was the death of his wife. For my wife and I, as most of you know, it was the death of our son. For you, it may be the death of a spouse or child, but it may be something different. Chronic health problems have a way of imprisoning people in depression, with a fear of when the subsequent surgery or bout with pain is coming again. Other people are imprisoned by traumatic childhood events, struggling with the lies someone convinced them to believe about themselves. Other people are imprisoned by past sins and regrettable decisions that have left them with shame, making them feel as if their biggest failures will forever judge them.

Over time though, as Lewis observed, we can learn to live, but the grief remains with us. For most of us, on most days, we can get up and go about our days, but the fear of what we’ve lost, of what we endured, or what we did, and what that means for us lingers with us.

How do we experience joy in the midst of a life where we still live with grief?

This Advent season reminds us of the joy received in the Lord's coming. Yet the fullness of such joy also requires waiting. For now, we live between the first and second coming of the Lord. The between stage is one in which we have received the joy of the Lord yet still endure grief. In such a stage, we must wait even though waiting seems especially hard once “Earth's joys grow dim; [and] its glories pass away,” as the Anglican minister Henry Francis Lyte wrote in what would become the hymn Abide With Me.

The prophet Zephaniah says, “The Lord, your God is in your midst, a warrior who gives victory; he will rejoice over you with gladness; he will renew you in his love; he will exult over you with loud singing” (Zeph 3:17).1 Although we still struggle as we wait between the reception of joy and the fullness of joy, Zephaniah wants us to know that the Lord isn’t finished. Our struggles aren’t the end of the story. Whether our struggles spring from grief, illness, sin, or so forth, it’s not the end. God hasn’t abandoned us to a hopeless plight.

The coming of the Lord in the birth of Jesus Christ is the emergence of hope, God’s act of love and promise that he is righting the wrongs. This is the basis for our joy, but such joy is something meant to be experienced. So how do we experience joy in the midst of a life where we still live with grief? This question reflects the tension between the existential joy we can experience in Christ now and the eschatological joy we have in Christ now but await the full experience in the second coming of the Lord.

Speaking specifically to the practice of youth ministry, Lauren Calvin Cooke suggests that existential must be physically experienced rather than just philosophically understood. In other words, experiencing joy requires “an embodied knowledge and experience of joy. It is not enough for young people to know about joy; they need to feel joy.”2 When joy is felt, the eschatological future becomes existentially present. Such an experience can keep us from falling into despair as we still struggle with grief in our present life (which I can attest to personally).

My concern here is two-fold. First, we need to experience the joy received in Christ, but we also can’t ignore the grief we still experience. To negate the former is to abandon Advent while negating the latter will only deepen the pain of our grief. So what practice might there be for us to experience the joy we receive in Christ but still live with the eschatological tension of joy already received but not yet known in fullness? Cooke calls our attention to the Eucharist (the Lord’s Supper) in which the “contradictions” of joy and grief are held together.3

I realize that in many churches the practice of the Eucharist amounts to simply receiving a small piece of bread and a sip of wine. But we must remember that this bread and wine represent the body of Christ broken for us and the blood of Christ poured out for the forgiveness of our sins (Matt 26:26-28). In other words, eating this bread that signifies the body of Christ and drinking the wine that signifies the blood of Christ is a physical reminder of God’s promises to us in Christ. When we receive the bread and wine, we also proclaim the death of Jesus Christ until he comes (1 Cor 11:26). By receiving the body and blood, we are also proclaiming the eschatological victory we have in Christ that extends joy to us.

In many churches, participating in the Eucharist or the Lord’s Supper is also called communion, but communion is fellowship. Therefore we cannot reduce communion simply to receiving the bread and wine. We must learn to see the entire assembly, our gathering together as Christians, as communion, and the receiving of the bread and wine as a culmination of our communion. In this aspect, everything from greeting one another, praying with each other, singing together, and everything else we do when gathered together is part of coming together to share in the Eucharist with Jesus through the presence of the Holy Spirit. Then our gathering together and sharing in the Lord’s Supper together become physical experiences of our joy in the Lord and the joy encountered again during the Advent season.

As a pastor and personallt, I know that many people are living with grief. No amount of seasons jolly will eliminate the pain of such grief. However, I’m thankful we can gather with our churches and share in the Eucharist together. As we do, I pray that we will feel the joy we have in Christ and will one day experience in fullness when Christ comes again. May this joy that Advent proclaims sustain us even as “Earth's joys grow dim; its glories pass away.”

1All scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version, Updated Edition Bible, copyright © 1989, 2021 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A., and are used by permission. All rights reserved.

2Lauren Calvin Cooke, "Finding Joy in an Unjust World: Practicing Deep Joy in Youth Ministry," The Journal of Youth Ministry 17, no 1 (Spring 2019): 77. As the subtitle indicates, Cooke is addressing this matter within the sphere of youth ministry but suggestion is applicable to all aspects of church ministry and Christians of any age.

3Ibid,

December 6, 2022

Advent: Love

The story of Advent is the story of the coming of the Lord. It is the story of God becoming flesh in the person of Jesus of Nazareth. So, not surprisingly, I always enjoy preaching through Advent. But what makes the story of Advent so important?

Isn’t it obvious what makes Advent so important? Perhaps but let’s not assume so. The Advent story might be characterized by what Tolkien described as “a story of a larger kind.1” That’s because the coming of Jesus is the big story of God redeeming the world, making everything new through his incarnation and eventual crucifixion, resurrection, and exaltation. But as beautiful as this big story is, it’s also difficult.

The beautiful baby Jesus will die hanging on a Roman cross. Yes, God raise Jesus from death and exalts him as the Lord and Messiah, but the only way to this victory is by being born into a life of struggle and walking the road of suffering to the cross. There isn’t any resurrection and exaltation without the incarnation and crucifixion first.

If we will trust God enough to walk the road to Jerusalem with Jesus to his crucifixion, then we are assured that we’ll also walk the victorious road to Emmaus with Jesus in his resurrection.

I bring this up because I know that as festive as this time of year is, there are people who still struggle in life, and the holidays don’t make the struggles disappear. In fact, for some people, the holiday season makes the struggles even more difficult. But we must remember that we are loved, especially when we struggle. We must remember that God has not forgotten or become apathetic toward us. Instead, God has pursued us with such passionate love that he is willing to enter life with us and suffer death for us, making a new life from death.

This is why the story of Advent is good news. We need not fear the coming of the Lord because the Lord comes to us as incarnation, crucifixion, resurrection, and exaltation. Advent is the arrival of salvation in Jesus Christ rather than condemnation. Advent means a new life sustained by love is possible. This possibility was realized on that road to Emmaus, where two disciples encountered the resurrected Jesus (Lk. 24). As they went along the road, the day eventually gave way to evening, and so this Jesus, who three days earlier was crucified and buried in a tomb, now sat at a table with them. At the table, their eyes were opened, and they recognized Jesus.

So if during this season, amid struggle, I hope the Advent story offers encouragement. I know life can be difficult, and continuing to live by faith in God is sometimes difficult too. But I believe that if we will trust God enough to walk the road to Jerusalem with Jesus to his crucifixion, then we are assured that we’ll also walk the victorious road to Emmaus with Jesus in his resurrection. This is the hope, love, joy, and peace that the Advent story invites us to participate in, even when we stumble and struggle.

As we journey through the story of Advent once again, may we remember that we are loved by God!

1Taken from a lecture by J.R. Tolkien, “On Fairy Stories,” 1939, the transcript is available at: http://www-personal.umich.edu/~esrabkin/wwnoft/tolkienonfairystories.html (last accessed on Tuesday, November 22, 2022).