Henry Jenkins's Blog, page 8

October 17, 2023

Into the Wild: A Reflection on Cosplay in Public Discourse: Notes on an Unfolding Semantic Shift (Part One)

Our words are not without meaning, they are an action, a resistance.— bell hooks

The fight against bad English is not frivolous…— George Orwell

Cosplay is big news today. And I’m not just talking about within the realms of fandom and fan studies; cosplay has hit the mainstream hard over the last few decades. A socio-cultural evolution seeing its meaning change in ways unexpected and not yet quite understood. Once describing a subcultural, niche fan practice, cosplay is fast becoming a metonym for all kinds of dressing up practices. Forget the subtleties of masking and costuming, masquerade, mimicry, fancy dress, dressing up, or just plain old dressing, it’s all cosplay now.[1] As a natural aspect of evolving phenomena, semantic shifts are hardly surprising— that’s not the story here. Like seasoned seamsters, fans and scholars are always adjusting the meaning of cosplay, altering its pattern and form, letting it out a bit here, a timely tuck or hem there, and always embellishing our understanding of this art of making otherwise. Less important then is the idea that cosplay’s meaning is stretchable, it’s the origin, nature, and agents of this particular public amplification that I want to observe and consider, and its potential impact upon what’s rather magically called the “cosphere.”

Pinpointing when I first became aware of journalists using cosplay as shorthand for dressing up in Western mainstream news and entertainment media reportage is tricky. I inappreciably felt the approaching storm before realizing it, like catching the sweet whiff of ozone on the summer air. A quick search of newspapers suggests it couldn’t have been before 2021 because that’s when “cosplay” starts showing up in news headlines. In the UK, the trend gathered pace during the 2022 Conservative Party leadership election, in which both candidates — Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak — were accused of cosplaying a variety of sources, from professions and trades to economic classes and past political figures.[2] Well-heeled Sunak, for example, was described as “cosplaying” a soldier and “playing” at being a plebeian, rather poorly, it has to be said, and Truss too, who was also mocked for her “Thatcherite cosplay”.[3] Moreover, as a “walking embodiment of [the] union flag,” Truss — frequently dressed in red and blue color blocks — was also thought likely to be cosplaying the Union Jack, the UK’s national flag, alongside dangerous concepts like nationalism and patriotism. (Following that line of thought, former UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher herself arguably cosplayed as soldiers and Russians.)

Images of Truss (bottom row) “cosplaying” as Thatcher (top row). Source: @LouisHenwood

This semantic shift did not go unnoticed. Large parts of the notoriously irreverent British public gleefully seized upon the idea of cosplaying politicians— a garden-fresh stick to beat them with. Prior to this groundswell of usage, cosplay-as-dress-up was most often targeted at former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson — infamous for dress up and play acting— and his “Cosplay Cabinet”: “A quick glance through their PR shots you will find top politicians dressed in camouflage, branded jumpers, hardhats, aprons, lab coats, police jackets, goggles and fishmonger hats.”

Image from Huff Post: Damon Dahlen/HuffPost

There’s nothing new in politicians dressing up to attract voters or to build their brand, of course. Appearing as or like another popular or public figure can help make the strange familiar, efficiently signaling political stances and continuities and so forth; a helpful tactic for “unknown quantities” wishing to amass public appeal quickly (and economically), as we’ll see later. And much like fan cosplayers, they draw upon a mix of sources, real life and fictional and specific and general.

JFK set a trend for Air Force bomber jackets, a vogue followed by every US president since, usefully tying into martial and hero mythologies.[4] Vladimir Putin reinforces his alpha male image by dressing up as all kinds of “action men,” from soldiers and bikers to hunters, the bare-chested variety. Buffoons and clowns continue to inspire Johnson and Donald Trump from their pantomime coiffures to their outsize clothing and grins.[5] And when official campaign photos of the usually sharp-suited French President Emmanuel Macron showed him unshaven and wearing a black special forces hoodie, he was roundly “accused” of cosplaying Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. Election campaigns, however, see even the most sartorially challenged politicians dress up as something, anything to attract voters; in the US, it’s often cowboys, in the UK farmers, in Taiwan, it’s Squid Game players, and in Peru, to secure the “otaku” vote, it’s anime characters.

Dressing up like fictional secret agents — think James Bond, all dark custom suits and bespoke watches — is de rigueur amongst male politicians of all stripes, however. (Tellingly, Putin’s personal vehicle registration plate is 007.) Like the imported trees in Belfast’s iconic “Palm House,” our idea of what powerful people look like — resolutely male and wearing business attire — is planted, deep-rooted, and out of place. Thus, women politicians too, sadly, often dress up like — or, today, cosplay as? — male politicians and tycoons, or spies. As Mary Beard writes, “we have no template for what a powerful woman looks like, except that she looks rather like a man.” Social progress, of course, brings the possibility of altering that template.

J’accuse!

But it’s not just politicians, journalists, or dissenters who are driving this semantic shift. Public discourse is awash with all kinds of people describing all kinds of other people as cosplayers, often in accusatory tones.[6] Members of American far-right, neo-fascist, male organizations are frequently, and mockingly, characterized as cosplaying Nazis or soldiers, real and fictional (e.g., “Call of Duty,” Peacemaker, or Punisher). Antifa fighters, those black-clad activists known as the “black bloc,” are likewise described as cosplaying soldiers or ninjas or even — to tactically muddy the waters — MAGA devotees, that’s to say charged with cosplaying MAGA insurrectionists at the January 6th Capitol Riot. Frequently too, MAGA adherents denigrate Antifa activists as “cosplay activists,” those whose activism is performative rather than substantive.

Keeping with the rich MAGA theme, CPAC 2022 not only played brazenly with fascist and Nazi symbolism and iconography but dabbled with performance art in the form of a tableau vivant.[7] While characterized on social media as cosplay, the “living picture” performance was closer to a cosplay skit, a short theatrical piece or performance. Hatched by pro-Trump influencer Brandon Straka, the skit’s surreality makes it worthy of description: a teary white male (Straka) wearing a fresh orange jump suit — and incongruously a red MAGA cap and conference badge — sits barefoot in a prop jail cell.[8] A consolatory Marjorie Taylor Greene kneels at his feet, scarlet-clad, dollish ‘n’ doltish, and happy to play Mary Magdalene to his sideshow Jesus. Outside the “cell” a tepid hellfire “preacher” leads an offbeat congregation in prayer. (If you feel up to it, you can check it out here.) After the act, onlookers could either silently contemplate the weepy prisoner — surely parodying commemorative traditions of silent moments — or don a headset and listen to testimonies from those arrested on January 6th, getting an earful and an eyeful at the same time— a watery encounter promoting reflection, one hopes.

Image from Daily Mail: Adam Gray/Daily Mail

With everything noted so far, you’d be forgiven for thinking that we’ve reached the limit of actions describable as cosplay.[9] Not so. In the public imagination, such is the stretchiness of “cosplay” that countries may be described as cosplaying other countries, from other times: during a United Nations Security Council meeting, Sergiy Kyslytsya (Ukrainian ambassador to the UN) asked, “Why has the Russian Federation decided to cosplay the Nazi Third Reich by attacking the peaceful neighboring state and plunging the region into war?”

Note that, apropos behavior, nothing is changing here; people are doing what they’ve always done, and countries; the only thing changing is how journalists and editors and everyday people are now choosing to describe those doings: what was once dress up, mimicry, pantomime, and so forth is now cosplay. A specialized media fan term is being publicly co-opted, in real-time; its meaning (potentially) altered as frequent misuse becomes standard. And, as we’ll get into later, adopting “fanspeak” allows lay users to tap into a wellspring of subordinate meanings, often nefariously; that’s to say, politicians readable as media fans, or “worse” — as far as flattening gender stereotypes go — as media “fanboys” or “fangirls.” The action of dressing up in the public sphere is itself undergoing something of a semantic costume change. And we must, as George Orwell advises, be ever watchful of language change — buzzwords, euphemisms, replacements, etc. — enacted by the state and its agents and adopted within public discourse, as we’ll also get into later.

Yet perhaps there’s good reason for the curious uptake of cosplay in news media and everyday parlance, and it’s not just a bad habit demonstrating muddy thinking. After all, the behaviors I’ve been cataloging do share much with fan cosplay— as far as a meaning or definition of media fan cosplay can be pinned down, that is. But do they fall within what Theresa Winge usefully describes as the “cosplay continuum”?

Let’s take a closer look.

Countries aside, people are using modes of dress to play with their identity; in many cases, there’s a citation of specific sources (real and fictional); some parties make their “costumes” while others shop for them; costumes can be outlandish or “everyday,” the latter form mirroring developing trends within fan domains for less costumey modes of cosplay, such as Disneybounding or “stealth” or “closet” cosplay. As in fan cosplay, certain performances have more depth than others with some “players” perfecting idiolects, facial expressions, gestures, mannerisms, and so on. But it can go deeper. News media, for example, described Truss as cosplaying Thatcher sartorially and ideologically; as with Thatcher, Truss cultivated a reputation for hard-nosed politics and an unbending leadership style.[10] During the 2022 leadership contest, the British public watched Truss (try to) forge herself as an “Iron Lady”; in keeping with technological advances, her robotic and despotic performance proved, however, rather more “Evil Robot Maria” from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927).

Does it seem fair then that people describe these behaviors as cosplay? Yes, perhaps. But for all the points of connection, something blocks me from affirming these kinds of happenings as cosplay. I sense a disconnect; deeper realities lie beneath surfaces. Encountering another mainstream headline or news story ballyhooing “cosplay” is like coming upon a cultural shadowland, offering a grimmer, soulless view or version of cosplay. Something is missing from these mainstream usages and practices, something vital, some vital things. To regain the missing things is to make sense of the disconnect.

Self-definition is one of those missing things. And relatedly, intention. Intention to cosplay, that is. (There are plenty of other intentions behind these usages and dress-up performances— courting voters, for example.) Like vegans, cosplayers announce themselves. That’s to say, they happily self-identify as cosplayers; they want you to know they’re cosplaying or are part of cosplay culture. Even those performing “stealth” or “closet” cosplay acknowledge their practice in some form, public or personal; inquiries upon it are not met with surprise, denial, or silence. Even cosplayer politicians — in the traditional fannish sense — like Taiwanese legislator Lai Pin-Yu proudly affirm themselves as part of the cosplay family. But the people involved in the opening examples are described as cosplaying; they do not recognize or identify themselves as cosplaying, nor indeed as dressing up; others label them so. Even today, politicians, say, may be unaware that “cosplay” is a thing, never mind a thing that they might do— such are the bubbles we inhabit.

Thus, while some politicians might be readable as cosplaying, they might not see it that way; they’re not trying to “be” or to “be recognized” as someone else; it’s accidental, coincidental, detrimental, if discovered. Stated otherwise, those “cosplaying,” or channeling the look or ideas of other national leaders, for example, would surely deny it. In their world, imitation is far from a sincere form of flattery (unless you’re the one being imitated, that is). Rather, it suggests fakery, unoriginality, and followership, as well as play-acting; when what politicians want, no, need is to be seen as the real deal, as trailblazers, as serious leaders, as themselves.

Is awareness a requisite of cosplay? To what extent must we know we’re doing it to be doing it? Must cosplay, like war or bankruptcy, be declared to be “real”? A curious question given cosplay’s deep bond to the imaginary, which brings me to my next missing thing— imagination.

Cosplay is an art of making things otherwise— the self, the text (in its broadest sense), the world. As Theresa Winge memorably describes it, cosplay is all about “costuming the imagination.”[11] The word we have somehow settled upon — for the time being, things can always change in cosplay culture — to describe this diverse range of behaviors tells us everything we need to know; more than just “dressing up as,” cosplay combines costume and (role)play and is deeply bound to the imagination and invention and pleasure and desire. Even when the cosplayer means only to replicate their source text, it’s still an act of imagination, often lovefuelled.[12] A worldmaking act illustrating a bondedness to the origin text and a wish to share and celebrate that bond with everyone, and to give and take pleasure in that sharing, in connecting with the source and with cosplay communities, real world and digital.

All this good stuff — creativity, pleasure, transformation, belonging, worldmaking — materializes from everyday encounters with the imagination. It’s hard to imagine cosplay without imaginings, and gloomy. Imagine: a wren without a song; a spring morning without its chorus— “a thousand blended notes”; a heart without cause to soar— “the freshness of the morning/ the dew drop on the flower.” The objects — bird, dawn, heart — remain in this imagining but lacking now the things that make them manifestly them.[13] And that’s what I feel when I see what’s being reported as cosplay in mainstream news and social media. It looks like people (possibly) dressing up as other kinds of people, all surface and no heart. And I find that it doesn’t really look like cosplay at all.

Where’s the intention, the creativity, the love, the community, the play?

A trail of questions returning me to my terminus a quo: Why are a great many people choosing to replace perfectly good terms — dress up, mimicry, costuming, copycat, and so forth — with cosplay? Beyond observing this surface change, what are we to make of it? What deeper realities lie beneath this semantic shift?

Artwork: “Once Emerged from the Gray” of Night by Paul Klee (1918).

[1] A semantic shift synonymous with the wider mainstreaming, or massification, of media fandom.

[2] Labour Party leader Kier Starmer described Liz Truss as indulging in “Thatcherite cosplay,” while he himself was accused of engaging in “Blairite cosplay.” Note: “Thatcherite” refers to previous UK (Conservative) Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher (1979-1990) and “Blairite” to previous UK (Labour) Prime Minister, Tony Blair (1997-2007.

[3] Notorious and odious right-wing British politician Jacob Rees-Mogg is routinely identified in news and social media as cosplaying a “toff” (a member of the British “upper-class”), particularly “Lord Snooty,” a character from the iconic British comic, Beano. For a fascinating broader discussion of class, mimicry, and British politicians, see “‘The Beano's’ Lord Snooty” (Part 4 of 4) by Dave Miller. CEOs and celebrities also tap into this kind of class cosplay, billionaire “tech bros” wearing priceless jeans and hoody combinations etc.

[4] JFK refers to former US President, John Fitzgerald Kennedy (1961-1963).

[5] Johnson is regularly derided for his awful “Churchill cosplay” too, referring to former UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1940-1945, 1951-1955.

[6] The selection of examples included here are drawn from social media searches and offer only an illustrative sample of how “cosplay” is being used within public spaces and discussions.

[7] The Conservative Political Action Conference, or CPAC for short.

[8] Straka was himself convicted on misdemeanor charges after the Jan 6th attack.

[9] I’ve been sticking to political realms but similar expansions in cosplay usage may be observed in other spheres, such as business, technology, climate industries, creative industries, and so forth.

[10] Thatcher too, famously, lowered the timbre of her voice and adopted “mannish” mannerisms to match dominant ideas of what powerful people look like, as discussed earlier.

[11] See, “Costuming the Imagination: Origins of Anime and Manga Cosplay” by Theresa Winge (Mechademia, 2006).

[12] Or “coser” as is popular within China’s cosplaying communities; a term gaining international traction, you see how language shifts and bends. Interestingly, note that this contraction drops the “play”— a discussion for another day.

[13] Fragment from “Lines Written in Early Spring” by William Wordsworth. Lines from “My Heart Soars” by Chief Dan George.

BiographyBased in the north of Ireland, Ellen Kirkpatrick is an activist-writer with a PhD in Cultural Studies. In her work, Ellen writes mostly about activism, pop culture, fan cultures, and the transformative power of storytelling. She has published work in a range of academic journals and media outlets. Recovering the Radical Promise of Superheroes: Un/Making Worlds, her open access book on the radical imagination and superhero culture, can be found here. Ellen can be found writing at The Break .

October 2, 2023

The American Key Demo Needs to Get Older

With America’s Senior Citizens in control of more money than younger generations, it is time for US entertainment companies to more aggressively appeal to older audiences.

In a CNBC report, Ipsos CEO Darrell Bricker stated that, “the single biggest power group in the economy going forward are older women because there's a lot of them and there's more every day.” This came out in 2021 and it has only become more accurate and important. As Bricker shared with me, population data shows that current “female seniors in America are 55% of the senior population, while men are 45%. In 2050 the UN estimates that 63% of American seniors will be women and only 37% will be men. Where the population numbers go is where the money goes. Senior women are the fastest growing age cohort in America today.”

FIGure 1: "Which U.S. Generation Wields the Most Economic Power?" from VisualCapitalist.com's Iman Ghosh and Marcus Lu

With American Baby Boomers having an estimated combined wealth of $75 trillion, an amount of wealth that towers above the $8 trillion held by Millennials, it is time for entertainment companies to change their “Key Demo.” Not only will this change allow them to focus on consumers that advertisers want and who can also pay for their subscriptions, but it will also push studios to make shows and films directly appeal to people who are 50+

But first…

What is the Key Demo?

The key demo is the primary demographic that advertisers and media creators want most as their audience. For decades, the key demo was mostly young people. As Jaime Weinman wrote for Maclean’s, “Young adult viewers have been TV’s target demographic for decades, because they’re thought to have less brand loyalty and more disposable income.”

In the 2002 article “The Most Desirable Demo,” NextTV.com’s R. Thomas Umstead explained why the key demo changed; “with cable-network penetration now pushing toward 90 percent of all U.S. television households, the weight placed on absolute household eyeballs during the 1980s and 1990s has given way to a more narrowly defined, demographic-oriented focus.” And according to Umstead, “no demographic is more desirable than 18-to-49-year-old adults.” [Emphasis added]

People under the age of 50 were so highly valued that audiences 50+ were described as “empty calories.” Umstead shared that while CBS enjoyed ratings success in the early 1990s because it did so well in total viewership numbers for several consecutive years, “those triumphs were the equivalent of empty calories. Because so much of the CBS audience was aged 55 or older…those ratings never translated into major ad dollars.” [Emphasis added]

While the key demo is often associated with television, it overlaps with consumers that movies, games, and sports historically targeted: young and typically male. Through the 1980s and 90s, the video game industry was primarily focused on appealing to males that ranged from being in kindergarten to in college.

(A 1988 Nintendo survey found that only 27% of the audience was female. Additionally, in the documentary Console Wars, Tom Kalinske - the President and CEO of Sega of America from 1990 to 1996 - explained that Sega saw teenage and college age males as its core audience.)

As the American film industry reorientated itself around blockbuster films, the young male demographic became a key demographic for movie producers. “The whole notion of the summer blockbuster has always been built around young men,” Comscore, Inc’s Senior Media Analyst Paul Dergarabedian told the New York Times in 2015.

But as Dergarabedian further explained, the importance of young men as a demographic is fading, “I think we’re about to see that change. The clout and importance of the female audience has never been bigger.”

And a reason why audiences who aren’t young and male are becoming more important is because…

The Financial Power of Young Men is Collapsing in Real Time.

The above is not hyperbolic. In general, Millennials and Gen Z have far less economic power than Boomers did. According to ConsumerAfffairs.com, “Gen Z dollars today have 86% less purchasing power than those from when baby boomers were in their twenties.” Zooming on a specific example of this generational disadvantage, “Gen Zers and Millennials are paying 57% more per gallon of gas than baby boomers did in their 20s.” Even more troubling, Millennials and Gen Z “are paying nearly 100% more for their homes than baby boomers did in their twenties.”

Figure 2 - Consumer Affairs, "Comparing the costs of generations"

Moreover, sectors that have relied on young men for the last decade have been especially gutted by this economic downturn; two of these are esports and crypto.

The esports sector has been largely male for years. As one report states, “despite the split between male and female video game players being very close to 50:50, the esports audience is still predominantly male,” with over 80% of the esports viewers being male.

During the 2010s esports became so popular myriad articles were published proclaiming that it would eclipse the NFL and other traditional sports. A 2017 Business Insider article, linked the NFL’s then lower ratings to young men being more interested in esports. Flashforward to 2023 and the NFL, NBA, and other sports have high television ratings while viewership for esports has dropped.

(Of note, for the 2023 Super Bowl, advertisers were actually focused on targeting people 50+ because, according to Danielle McMurray, “with younger audiences cutting back on spending, marketers are wise to focus on the 50+ audience.”)

In the last few years Venture Beat has reported that the middle class of esports is dead and Bloomberg has covered that, “the hype around esports is fading as investors and sponsors dry up.” Moreover, esports leader FaZe Clan, which once was valued at over $1 billion in 2021 has lost over 90% of its worth.

Figure 3- Since FaZe Clan went public, its stock value hit a high of $24.69 only to collapse to less than a dollar.

In regards to crypto, as Marisa Dellatto wrote for Forbes in November 2021, crypto’s super users were young men. That was the same month the total crypto market hit a value of over $3 trillion. Since then, the value of the total crypto market has plummeted more than 66%.

Figure 4 - Overall cryptocurrency market capitalization per week from July 2010 to March 2023 (in billion U.S. dollars) from Statista.com.

Returning to the topic of television, recent economic contractions and business deals have brought to light information that suggests that young adult audiences have not been economically viable consumers for over a decade. For example, The CW was created in 2006 when CBS and Warner Bros. merged their respect networks, UPN and The WB, into one new network. When Paramount and Warner Bros. Discovery sold their controlling interests in The CW to Nexstar in October 2022, something shocking was revealed about The CW. The CW, a network known for appealing to the key demo of people between 18 - 35, a network that had hit shows such as America’s Next Top Model, The Flash, Supernatural, Arrow, The Vampire Diaries, Gossip Girl, and many others, “has never been profitable.” [Emphasis added]

In 2018, Charles Lane wrote for NPR that the influential male demographic was waning. “Men between the ages of 18 and 34 have been a key demographic for marketers for years,” Lane said. “That's starting to change, say some marketing experts, who say the economic fortunes of these men have declined.”

The prediction made by Lane is now here, and…

The Shift is Already Happening.

The economic power of older women is already impacting the economy and non-entertainment brands are beginning to take note. For instance, PYMNTS noted that the beauty industry has placed “a renewed emphasis on older women as a means of capturing the attention of one of the wealthiest cohorts of consumers.”

And “wealthiest cohorts” does little to truly communicate just how economically powerful this demographic is. This is because American women over the age of 50 “represent over $15 trillion dollars in purchasing power.”

Older people are already flexing their superior buying power. As James Rodriquez wrote for Business Insider, boomers are buying homes at a substantially higher rate than millennials.

“Between July 2021 and June 2022, boomers were the largest share of homebuyers for the first time since 2012, according to new data from the National Association of Realtors,” Rodriquez penned. “Boomers purchased 39% of all homes that sold during that span, up from 29% the year before. Millennials, on the other hand, saw their share of the market shrink to just 28%, down from 43% the year prior.”

Rodriquez further stated, “despite the numbers game favoring millennials, a slew of other factors conspired to allow boomers to stick it to their successors. The main thing, though, was cash. Boomers are more advanced in their careers and in many cases have already spent decades amassing home equity, making them much more likely than other generations to fork over all cash for their next property. And when bidding wars become the norm, it pays to offer a lump sum.”

There is also a gendered component to this because single women are buying more homes than single men. In every state except North and South Dakota, women own more homes than men. According to Khristopher J. Brooks, “single women own roughly 10.7 million homes, compared to 8.1 million for single men.”

Figure 5 Source: USAFacts.org - "Which generation has the most wealth? Baby boomers have the highest net worth, averaging $1.6 million per household"

And remember, the wealth that older generations currently have will persist for decades to come. As research from USAFacts.org documents, "baby boomers have the highest household net worth of any US generation." USAFact.orgstates, "with most baby boomers financially planning for at least a few more decades, they benefit from wealth earned from long careers and have more robust retirement accounts than” other generations.

Furthering this gap in economic buying power is that student loan payments will restart in October 2023. According to Apollo Global Management’s chief economist Torsten Sløk, it is estimated that student loan repayments resuming will, “subtract roughly $9 billion from consumer spending every month, or roughly $100 billion a year.” Sløk goes on to point out that this, “will mainly have an impact on younger households.”

In short, older women can buy houses in the real world; younger adults can only buy houses in virtual worlds.

And in regards to entertainment…

This is Already Impacting the Entertainment Industries.

A Comscore/AARP study found that older audiences returned to movie theaters in 2022 in numbers that outpaced their attendance before the pandemic. “According to the data,” the report notes, “the attendance of people 45 and older grew five percent from previous attendance levels in 2019, the last full year before the COVID-19 pandemic affected theater attendance.” A movie that significantly benefited from this was Top Gun: Maverick, which benefited from nearly 40% of its audience being 45 or older.

Even Barbie, the film with the biggest box office of 2023, somewhat reflects these trends. For instance, 18-24 year olds only made up 27% of Barbie’s opening weekend. Evidence suggesting that Barbie’s success is partially due to an overrepresentation of people outside of the key age demo.

It isn’t just the traditional theatrical experience that appeals to older audiences, because television is finally catching up. As Warner Bros. Discovery Chief US Advertising Sales Officer Jon Steinlauf said in May 2022, “our most affluent viewers are adults 50+….They account for over 50% of all US consumer spending. A large majority of them watch us every month.”

In the world of streaming, people 50+ have recently become the largest age group in this sector. According to the Decider’s Greta Bjornson, for the “first time ever, consumers ages 50-64 are streaming more TV than the generation below them.” On top of this, Netflix has announced plans to better appeal to older consumers. And while networks used to see senior citizens as “empty calories,” Yellowstone has become one of the most popular shows in the country due to appealing to older audiences.

Similar to Yellowstone, if we go back to August 2022 and look at Netflix’s top show, we’d find that Stranger Things was knocked out of the number 1 spot by Virgin River, which, according to AdWeek, had a “viewing audience [that] was nearly two-thirds over 50 and almost a third over 65 years old.”

We aren’t just seeing older audiences become more important, we are also seeing older talent becoming essential to shows or movies finding success. According to a study from the National Research Group, people were asked to name movie stars that could get them to see a movie. Nineteen of the top 20 actors named were over 40; the only exception being Chris Hemsworth who was 39 at the time of this research. Even when the list expands to the top 100 actors, only 13 are under the age of 40 when the study was conducted.

And we are beginning to see this consumer power of older women impact the video game industry. An April 2023 AARP report, “Gamers 50-Plus Are a Growing force in the Tech Market,” found that gamers over the age of 50 are now a population of 52.4 million, roughly 45% of all Americans in that age range. On top of that, “in 2023, older adults’ continued interest in gaming could lead to $2.5 billion in biannual spending on digital and physical game content.”

As CBS’s Chief Research Officer Radha Subramanyam recently said, “at CBS, we love older viewers. They watch a lot of television. And advertisers love them because they have tons and tons of spending power.”

Not only is this group increasingly spending more money, it skews female because 52% of the women in this demographic play every day vs. just 37% of men.

But now the question is…

The Future is Silver and Female, What Should Be Done?

“The 18-34 year old demographic has traditionally been the most coveted by Hollywood,” Comscore, Inc’s Senior Media Analyst Paul Dergarabedian shared with me. “But in recent years, the realization that mature audiences not only have the discretionary income but also the desire to consume big screen and small screen entertainment should inspire studios and producers to tailor films and TV shows that have appeal to those over 40.”

A soon to be real world example of this appeal to seniors is The Golden Bachelor, which is a twist on The Bachelor franchise but will center its focus on a 72-year-old man looking for love among women who are in their 60s and 70s. And The Golden Bachelor is not alone. As New York Times article by John Koblin points out, The Golden Bachelor will be joining a landscape slowly pivoting to appeal to older audiences with shows such as the continuation of the original Law & Order, and reboots of Magnum, P.I. and Matlock. Even Abbot Elementary, a hit show that feels as though it appeals to a young audience, has a viewership with a median age of 60.5.

With people 55+ becoming more digitally literate and expected to be the dominant consumer group for decades,[1] major entertainment brands are facing a consumer landscape in which young people are simply not a worthwhile group to pursue. Or as Ryan Glasspiegel wrote for Barrett Sports Media, “Baby Boomers Have All The Money, Brands & Advertisers Have To Pay Attention.”

Of note, this is not advocating for uninspired entries from legacy franchises to be created. Instead, it is advocating for films and shows to be made that highlight actors older audiences enjoy or that have narratives important to Boomers.

For entertainment companies in need of advertiser and subscriber revenue, embracing this shift means more than just producing more Yellowstone spinoffs (with that said, no one is against more Yellowstone). It means doing more to craft shows and films that resonate with people 55+. This could be more movies like 80 For Brady or a reboot of The Golden Girls, but it also means content that speaks to the everyday human experience of getting older and wanting more out of the life one has left.

As the value of media companies have plummeted, many industry experts have provided several smart reasons as to why so many streaming platforms are failing. But what they often overlook is the generational wealth gap and the customers these new media companies focused on. Digital media leaned heavily into a generation with little disposable income, a lot of debt, and a job market in which entry-level jobs will be taken by AI. So, while linear entertainment may appeal to the olds, it is the olds who have the cash. And if the entertainment industry wants to continue to see green it will have to follow America’s population into its golden years.

[1] Visa’s Wayne Best, Senior Vice President and Chief Economist wrote in this 2018 report, “baby boomers (those born between 1946 and 1964) have continued to dominate consumer spending in the U.S. In fact, consumers over 50 now account for more than half of all U.S. spending. They are also responsible for more spending growth over the past decade than any other generation, including the coveted millennials.”

“As a group,” Best continued, “this over-50 crowd should continue to be a major force in U.S. consumer spending, especially as those over 60 years old drive growth over the next five to 10 years.”

Additionally, Edward Yardeni, an economist and founder of Yardeni Research, believes that spending by Boomers could delay the next recession.

BiographyNicholas Yanes Ph.D. is a digital vagabond who now works on developing artificial intelligence systems. Having drifted away from traditional academia, Yanes’s non-AI professional work centers on analyzing entertainment industries, contributing to M&A research, and periodically publishing an awesome article now and then. (Check out The Birth and Death of Budcat Creations, Iowa’s First and Only Triple-A Game Studio.)

His first book, The Iconic Obama, examined the 2008 presidential election and its relationship to popular culture. And his second book, Hannibal for Dinner, reflects on Bryan Fuller’s adaptation of Dr. Hannibal Lector’s adventures. Yanes has written for CNBCPrime, MGM, ScifiPulse, Sequart, the Casual Games Association, Shudder’s blog The Bite, and several other publications.

More about Yanes can be found at his LinkedIn profile.

September 18, 2023

The Space Between Fiction and Reality: A Conversation about ‘Swarm’ and the Crucial Project of Cinematic Representation

Swarm (2023) is a streaming television series created by Donald Glover and Janine Nabers about a super-fan of Ni’Jah (read: Beyoncé)—who becomes a serial killer, driven by her love of Ni’Jah. Jacqueline Nkhonjera studies race, gender, and postcolonial media, and Yvonne Gonzales studies fandom, queerness, and affective attachment; they have come together in this dialogic essay to process this piece of media that pulls their interests together in new—and sometimes horrifying—ways.

Yvonne Gonzales (YG): I want to start this conversation, before we get into more of our research-based analyses, with a discussion of just how this work made us feel. I found myself viscerally uncomfortable so often. I flinched away from the screen on several occasions, and it was actually hard to finish. I admit, I’m generally averse to thrillers, but that last episode was rough. If this is a comment on its quality, which I don’t intend it to be, Swarm is incredibly powerful. It inciting discomfort is intentional, but it was definitely a difficult watch. How did you find yourself responding?

Jacqueline Nkhonjera (JN): I agree—there were several parts of the series that were difficult to watch. I found myself covering parts of the screen with my hand, with one eye shut, as I waited for the more visceral murder moments to end. I am also averse to thrillers and gore, so this was unsurprising. But I found myself sitting in discomfort beyond those scenes as well. I struggled with awkward exchanges between Dre, the main character, and the people in her life. I was consistently on edge each time Ni’Jah appeared on screen, afraid of what reaction her presence would elicit from Dre. Nothing about this series is comfortable—from the casting to the storyline, down to minute cinematic choices made by the creators. Why do you think discomfort was such a key tenet of this watching experience? What was achieved?

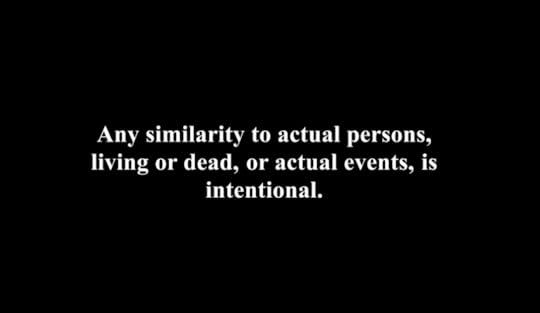

YG: I’m so glad that you brought up the discomfort not only with the murders and violence, but with the seemingly normal human-to-human interactions and Dre’s constant failures. As for why discomfort was so central, I think that might be a better question to loop back to, as it’s so tied up with another facet that’s integral to Swarm: its relationship to reality. It even starts with the bold text on a black screen: “This is not a work of fiction. Any similarity to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events, is intentional.” That attachment to reality is, for me, a major part of the discomfort. I found myself watching Dre obsess over Ni’Jah with a massive poster of BTS hanging up behind me and wondering is that supposed to be me? I’m a super fan—one who doesn’t kill anyone or get into fights with strangers on the internet, to be clear—and one major effect of the discomfort of Swarm is that I found myself reflecting on my own parasocial attachments to my celebrity love objects; maybe that’s the point, or one of them.

JN: Swarm did not remain within the confines of my screen either. The series bled through the frame and into my day-to-day life. I thought of some of my friends, who are Beyonce super fans, and I heard Dre’s dialogue in their voices at certain moments. When Ni’Jah dropped the visuals for her new song Festival, I was taken back to the year Beyonce dropped the Lemonade (2016) visual album. It made so many people in my life feel seen—like the songs were made for them. Depictions of that cathartic experience created some of the most powerful moments in the show. It is a beautiful joy to witness and one that I have felt as well. I agree that this is the point at which the discomfort sets in. Relating to Dre’s connection to Ni’Jah—even to a small extent—while also possessing a deep fear of that attachment creates an unsettling tension. Her character moves audiences to introspection in a way that I find fascinating. Dre is the canvas upon which we are invited to negotiate our own relationship to the affective attachments in our lives.

YG: Absolutely, it very much forced a reckoning with reality. I found myself struggling, though, as someone who has devoted my whole career to studying the real-life joy of the fan experience, with the pathologization of Dre’s fannishness. Her murders are framed as a direct result of her love of Ni’Jah; in Swarm, being a fan is, in itself, a sickness. The only other Ni’Jah super-fan we see is within the true crime episode, where he briefly talks about the supportive community but then switches into something of the lines of “yeah, we’ll attack people online, but we don’t murder.” Especially since Swarm very intentionally asks us to attach this story to reality, I don’t love this dismissal of fans and fandom in general as insane, as the cause of violence, without addressing the actual purpose of fandom, which is often to provide community to marginalized people. In many cases, fandom is where people can explore queer identities—which I would love to get into with Dre’s unspoken queerness—but also, in the case of the Beyoncé fandom, to facilitate a community of Black women around an object that they can take inspiration from and comfort in. What does it mean to turn a space of historical marginalization into a pathologized mental illness that produces violence?

JN: You have, so aptly, put words to some unnamed feelings that I am sitting with. The predominantly Black cast was what initially drew me to the series. I never thought I’d say this and wouldn’t have guessed that I needed it but: it feels liberating to see a Black woman casted as a serial killer. It’s exciting to see Black women play roles that are largely played by white men, even when they are frightening or uncomfortable. We deserve the complexity, range, and nuances of roles that are afforded to those with social positions that are lauded in our society and—by extension—the media industry. A role like this pulls Black women in from the margins and suggests that we too can make a home of the weird, the scary, and the spine-chilling. There’s a lot of power in that.

That said, I found myself feeling protective over Dre’s character. Her fandom, as you noted, was persistently positioned as an illness, and her personhood outside of it was left quite bare. There was a vacancy to Dre, her personality and dialogue an echo of her past. “Who’s your favorite artist?” she commonly asked her victims before killing them. To invoke Audre Lorde (1985), there are no new ideas with Dre, only new ways of making them felt. With her character being so deeply attached to her fandom, it was difficult to humanize her. The joy and safety that fandom provides is easily overlooked in the series. Instead, she is presented as a victim of it, like she has no choice but to attack her victims due to her allegiance to Ni’Jah. This depiction of Dre strips her of agency and humanity in a way that I found quite jarring.

How can we better walk the line of representing marginalized groups and individuals in new ways without reproducing hegemonic stereotypes? In this case, Swarm reproduces common depictions of Black women as senselessly angry, for instance. And it doesn’t end at that—there is much to be said about representations of her queerness as well.

YM: Wow, there’s so much to respond to here. You’re right, it’s such an uncomfortable balance: how can Black women be represented as complex and imperfect and boundary-breaking and terrifying without falling into stereotypes? What we’re really talking about here is what is good and bad representation? I would argue that portraying a queer Black person’s—I hesitate to use the term “woman” for Dre, but we’ll come back to that—attempts to find community and love through her attachment to an idol as illness is… not necessarily bad representation, but complicated representation. Because you’re right, it’s rare to see Black women treated with the same care that Netflix uses for Jeffrey Dahmer or Ted Bundy, and that care is deserved. But then, is this harmful? Is this going to dissuade Black women from engaging in fandom and forming homosocial relationships like the one Dre had with Marissa before her death? And especially when you bring in all of Dre’s other identities—queer, gender non-conforming, foster child—why must she be the villain? Again, what does good representation mean, and where do portrayals like this fit?

JN: Right, and how do we engage in representation that honors the intersections of different identities? This depiction of Dre centers her mental illness, for instance, and marginalizes other parts of her identity. Her queerness is not given the attention or care that the storyline demands. Also, when dealing with questions of desire and wanting—it’s difficult not to consider this facet of her identity in relation to her attachment to Ni’Jah. The scene where Dre bites into a red apple, as a representation of Ni’Jah’s neck, feels deeply erotic on both a functional and symbolic level. The fruit, a common symbol for affection and forbidden desire, suggests a consumption of—and hunger for—Ni’Jah. An exploration of that hunger in relation to Dre’s queerness would have complicated Dre’s character in a way that would’ve felt more human. Good representation doesn’t just consider parts of people. It creates room for those parts to exist in messy dialogue with one another. We need to be willing to get messier.

YM: That’s so bold to say, when I feel like Swarm already revels in the mess. Maybe the fully intersectionality-aware version would be a few episodes longer! But to return to the apple (or was it a plum?), the forbidden-ness really feels key. I think there might be a reading of Swarm in which Dre’s murderous impulses come from her suppression of identity. You see in the interviews with Marissa’s mother some remark about how women could still be friends without being “...funny.” All of Dre’s murders, too, start with some slight—however imagined—against women. Even her outburst as a child was because she viewed some girl as harming Marissa. And then once Dre (as Tony) gets together with Rashida, she (he? they?) goes for at least a year without killing (as far as we know), maybe because they’re living in their true identity and are satisfied. That is, at least until Rashida offends Ni’Jah.

Again, I don’t think this is a definitive reading of Dre’s queerness, but it’s an argument that we commonly see about other serial killers, like Dahmer or Gacy: murderous intent as a result of oppressive heteronormativity and internalized homophobia. I feel like I’m writing a long Tumblr conspiracy post with this one, but I think it’s important to look at when marginalized identities can be read as the cause of mental illness in the media, and why the creators set it up that way. Maybe the way to segue this rant into something more productive is a question: what do you think the intention of Swarm is, for the creators?

JN: This makes me want to get back on Tumblr—I need more Tumblr conspiracies in my life! What an interesting read on suppression, queerness, and violence in the show. This is the mess I was looking for! By “mess,” I mean the interconnectedness of things that don’t feel like they can or should be related, the narratives that are imperfect and confusing but valuable still. From what you’ve just shared, it’s true that some of that weaving and connecting needs to be left to the audience. After all, media are co-created by both maker and watcher. As for the intention of Swarm, I think that there are many.

One thing that we haven’t touched upon yet is the show’s commentary on social media and technology through Dre’s attachment to her phone. This relationship is put on full display when she spends time at Eva’s cult-like get away. Dre becomes frantic when Eva takes her phone away, and she ends up running over her with her car. The need to stay close to the phone seems to stem from her desire to stay informed about Ni’Jah-related news on her Twitter “stan account.” The account and her phone also become a space of affirmation. In a world where people don’t seem to understand Ni’Jah’s power and excellence, a community of like-minded people are only a click away.

The digitalization of her community, thoughts, and feelings is also made evident in the texts she sends herself through Marissa’s phone after she dies. Dre’s phone is a space of mourning and celebration all at once, a space of both loneliness and community. In the final episodes of the show, when Dre starts dating Rashida, there are significant changes in her gender expression, walk, and voice. She almost feels like a different person. She also no longer has a phone. Whether the loss of her phone—and all that it represents—brings her closer or further away from a potentially suppressed self: I don’t know. But I think that there is something to be said about people who find refuge in the digital world. This could be the intention of the creators or just another Tumblr conspiracy! What are your thoughts on representations of social media and technology in this project?

YG: I loved the focus on technology; especially in the early episodes, every time Dre pulls out her phone we hear a buzzing swarm in the background. When she opens her phone in that first episode and sees all the missed texts from Marissa, the swarm becomes overwhelming. Technology, for Dre, is both a lifeline and a manifestation of obsession. A lot of the people she kills, she kills because of things they said about Ni’Jah online. She kills Eva because she took away her phone and, by extension, her connection to time and Ni’Jah. The phone becomes her connection to Ni’Jah once again when her lack of a phone prevents her from getting her tickets replaced. The thing that seemingly pushes her to get her shit together and settle down as Tony in Atlanta is the deactivation of Marissa’s phone; for her, “normalcy” as we understand it requires her to be separated from technology and, by extension, Ni’Jah.

I think the facet of the online fan experience that really gets glossed over and forgotten is how fandom functions most centrally as a community, not between fan and performer but within and between fans themselves. She talks about her Twitter followers as friends, no matter how often people say things like, “Those are not your friends, those are some crazy ass fans. They don’t give a fuck about you, it’s not real.” For Dre, though, the digital is the most real. And often, as we discussed before, online spaces exist to bring marginalized folks together around the things they love. The dismissal of her social life, as it exists through technology, further alienates her from real life social interactions. We’re really in the mess here, but technology provides access to some forms of social life and community, while also preventing access to others. It can be all consuming and warp perceptions of reality, specifically in the context of “the Swarm” or “the Hive.” This contrasting portrayal of technology as both negative and positive is a great example of how technology and social media actually do function—they can be wonderful, and they can be terrible. Did you find yourself being critical of your own social media use after watching this?

JN: Absolutely, it made me interrogate my own connection to social media, technology, and my “digital” communities. As a diasporic subject, my connection to my physical home and communities across southern and eastern Africa is highly mediated. I cultivate and strengthen relationships through a screen and—in many ways—technology keeps certain parts of me alive. Living in the West, where certain parts of my identity remain severely undernourished, I often turn to my devices to resuscitate the parts of myself that I do not want to forget. If people around me aren’t talking about a political event or afrobeats album drop, for instance—I turn on my phone to find the people who are!

I was raised in multiple countries, and I sit at the intersection of several identities. I exist between borders, both physical and metaphorical, and I have made homes of spaces between the digital world and my off-screen reality. Social media is one of the few spaces where I find comfort in my liminality; where I can easily engage with people who have similar lived experience, and where I am able to tend to multiple parts of myself. I think that this is also indicative of the realness of digital spaces and communities. Conversations like this are an invitation to take that more seriously. Swarm encourages us to do the same.

YG: I think Swarm makes that uncomfortable, though; no one takes Dre’s online love seriously, and while we occasionally see tweets praising Ni’Jah and calling her a goddess, we see far more of the negative aspects of online communities like fandoms. For example, I know that through fandom, I can find people all over the world whose couches I could sleep on. Hell, when I moved to LA, a Twitter follower gave me their couch; it’s still in my living room and great for naps. Swarm doesn’t show any of that, not really. There is a little taste of that when Festival drops in the first episode and Dre transforms suddenly into a sexual, confident person, but it is immediately overshadowed by Marissa’s death. I wish we got to see how beautiful the internet can be, especially for marginalized people. Fandom was instrumental for my own gender and sexual exploration, and many of the people who are part of these intense fan communities are queer.

I think Dre’s queerness is an important part of Swarm, too, but not one that the show spends too much time on. Why do you think that by the end, Dre is Tony—both in the final episode, and in the pseudo-true crime episode—but there are no conversations of gender? The closest we get is Rashida bringing Dre a tampon and saying “I don’t care.” We also see Eva kiss another member of the cult and Dre’s confused face in response, like she wasn’t aware that was something people could do comfortably. Yeah, I just want to push towards an understanding of how gender and sexuality function within Swarm and how we can read it as an audience.

JN: Agreed, however I think that Dre’s attachment to her online world—no matter how uncomfortable it may make us—still depicts an important reality that many of us have experienced. That said, it is true that it is not portrayed in the most positive light and that felt like a missed opportunity in the series.

You bring up an interesting point about the absence of conversation around Dre’s gender despite the shift in Dre’s presentation as depicted in the final two episodes. To an extent, I don’t think the creators wanted audiences to read Dre as a definitively trans character. Is Dre’s change in appearance a reflection of gender or is it a reinvention driven by a need to remain under the radar? These tensions, and the development of Dre’s gender across the series, felt frustratingly simple. This is often what it comes down to in conversations around representation: which identities are granted the privilege of particularity? And which ones are rendered ambiguous and open to debate?

As you mentioned, the vagueness around Dre’s gender is heightened by the true crime episode, where it’s revealed that Dre is now living under the alias Toni. What an interesting episode—I found the stylistic shift to a mockumentary fascinating! Stylistic boundary-pushing within film and TV is an incredible way to reimagine on-screen representation. It creates room for audiences to get to know characters in ways that aren’t as easily attained in traditional filmic formats. Shows like Dear White People serve as an example of this—the main character’s radio show is used as a space for her to air out personal grievances and frustrations that nuance the audience’s understanding of her life and actions.

What role do you think the medium and stylistic choices of the show play in the ways that fandom, Black womanhood, and queerness—for instance—are represented in Swarm? What can we learn from them? This is an important question to ask for this show and other on-screen projects that center the narratives of marginalized folk.

YG: I want to tattoo your response on my forehead, specifically that question: which identities are granted the privilege of particularity? Gender is one of those identity aspects that feels impossible to pin down, and through this discussion, I am coming to appreciate the embrace of that ambiguity with Dre; the debate itself becomes generative. There’s just a particular tension with portraying a potentially trans person as a serial killer in the political environment we are experiencing in 2023, which might explain my sensitivity to the portrayal.

As for the true crime episode, that was the part of the show that really had me thinking. No joke, I googled “Andrea Greene” at the end of that episode just to make sure, 100%, that this wasn’t a dramatization of a true story. In that episode, they censored every mention of the pop star Dre was obsessed with, and they referred to the fandom not as the swarm but as the hive. On top of that, the mug shot they showed at the end was not Dominique Fishback but some other actor; the family interviewed were also not the same actors who played her foster family in the previous episode. And then that red carpet footage of Donald Glover talking about how he’s working on an adaptation with Janine Nabers and Dom Fishback—I truly believed it was real for a second. That in itself says so much about the fact that this is a believable story, or at least, it presents itself in such a way that it could be real. As much as we argue for authentic representation, a part of me believed this story either way.

True crime is also a genre that is most primarily consumed by white women, so what does it mean to tell the story of a Black woman through this specific medium? And the title of that episode—“Falling Through the Cracks”—speaks heavily to identities and unequal distribution of attention, especially when the detective is also a Black woman. Medium says something, so what does this medium and the perceived consumption of it say in this instance?

JN: I googled “Andrea Greene” too! I also called the number at the end of the episode and reached a voicemail where a pre-recorded voice asks if you have any information on the whereabouts of Andrea Greene. The person is then interrupted by, who I assume is, Andrea Greene. Andrea asks the speaker who their favorite artist is, and the speaker starts to scream. The voicemail is then cut short. This is another example of, as I mentioned earlier in our conversation, the ways that Swarm (quite literally) bleeds through the cinematic frame and into our day-to-day lives. From a functioning voicemail feature, to several real-life references, a mockumentary episode, and the use of interview footage of the creators—Swarm challenges storytelling traditions in a new and interesting way. It is a multimedia offering that blurs the lines between fiction and reality, the digital and the non-digital.

The consumption of such a project, keeping in mind the racialized consumption practices of true crime that you brought up, elicits a discomfort because it is unusual and unexpected. This also circles back to our conversation around the politics of discomfort and the use of the “uncomfortable” as a tool. The question remains: when is instrumentalizing discomfort effective and at what point does it become harmful? Swarm, even in its representational shortcomings, provides powerful insight into the good and the bad of on-screen representations.

YG: That’s a great question to leave this conversation on: when is discomfort effective, and what does it tell audiences about themselves? This conversation has become so generative from the starting place of discomfort, and it invites us to ask ourselves why certain things make us flinch away from the screen. Swarm is a great vehicle to ask these questions and masterfully forces us to do so. I’m going to be thinking about this show for a while.

JN: Agreed! The question of why we respond the way we do and—with reference to our dialogue on mediums—how this is achieved by creators is an important place for us to land. I’ll be thinking about this too.

Biographies

Jacqueline Nkhonjera is a Dual Masters candidate in Global Media and Communications at the University of Southern California and the London School of Economics.

Yvonne Gonzales is a doctoral student at USC Annenberg.

August 28, 2023

Fandom, Participatory Culture and Web 2.0 — A Syllabus

As regular readers of this blog know, the syllabus for my PhD seminar on fandom studies has evolved a lot through the years. The changes I have made this round mostly center on integrating a transcultural fandom perspective across the whole, with a particular emphasis on East Asian fandoms. This shift reflects a number of things. For one thing, I have a growing number of PhD students with strong interests in K-pop and its fans as well as a growing constituency from the East Asian Language and Culture program at USC. I was recently given an honorary appointment there to reflect my involvement and commitment. Beyond that, having spent seven weeks this summer teaching, speaking, and doing research on fandom, I am really fascinated by everything I learned and brought back a ton of interesting raw materials to work through. I also see transcultural fan studies as one of the richest spaces in the subfield at the moment. This is why I ran the Global Fandom Jamboree here a year or so back. We are building contact with fandom studies faculty around the world, offering us new data on different local practices and logics. And to do this we need new theories which deal with regional, diasporic, and crosscultural connections within fandom. I am especially intrigued with the nexus between Japan, Korea, and China and the continued role of America and the UK in that region. Each of these cultures has vibrant and distinctive fan communities and a great deal of cultural exchange despite geopolitical conflicts, both historical and contemporary, which makes this to me the most compelling space to discuss. And there are open questions about how India fits into this nexus as another major pop culture-producing country or the emerging role of Thailand and Southeast Asia in relation to this nexus. I have lots to learn here, but there's a broad range of expertise amongst the students enrolled in the class and so I look forward to creating a context in the classroom where we can all learn from each other -- one of many reasons I am leaning heavily on the dialogic writing process for the assignments.

Comm 577: Fandom, Participatory Culture and Web 2.0Fan Studies:emerged from the Birmingham School's investigations of subcultures and resistance

became quickly entwined with debates in Third Wave Feminism and queer studies

has been a key space for understanding how taste and cultural discrimination operate

has increasingly been a site of investigation for researchers trying to understand informal learning or emergent conceptions of the citizen/consumer

has shaped legal discussions around appropriation, transformative work, and remix culture

enters discussions of racial representation, diversity, and inclusion within the entertainment industry

offers a useful window for understanding how globalization is reshaping our everyday lives

contributes to important debates about the nature of media authorship

and so much more

This course will be structured around an investigation of the contribution of fan studies to cultural theory, framing each class session around a key debate and mixing writing explicitly about fans with other work asking questions about cultural change and the politics of everyday life. This term, I have chosen to revise my syllabus to reflect ongoing debates in the field – in particular, a new effort to “de-colonize fandom studies,” to re-center the field around questions of race and nationality, as well as its historic focus on gender and sexuality. Together, we will work through the ways that this new work requires us to question and revise earlier formulations of the field. I am also building on research I did this summer on fandom in Shanghai to give particular attention to the matrix of different fandoms that intersect in East Asia, including those from China, Japan, South Korea, the United States, and Great Britain.

Student Learning OutcomesDistinguish among fandom, participatory culture, and Web 2.0

Map the roots of fandom studies in earlier theories of audiences, readers, subcultures, and publics

Recognize and apply methods (ethnography, autoethnography, historiography, close textual analysis) associated with fandom studies

Explore the links between fandom studies and earlier forms of grassroots media practice

Engage with debates in fandom studies around gender, sexuality, generational differences, race, and nationality

Apply concepts like transcultural fandom and cultural imperialism to understand fan cultures in the East Asian context.

Identify core fandom practices, such as fan fiction, vidding, and cosplay

Map the social dynamics (and tensions) that define fan communities

Discuss the relationship between fan activism and civic imagination

Define core concepts used to explain fan activity, such as resistance, participation, engagement, taste, and mastery

Question the conflicting assumptions about authorship and intellectual property that shape relations between fans and producers

Debate Moral Economy and Fan Labor as contrasting models for how value emerges from fan communities

Make an original contribution to the scholarship on fandom and participatory culture

Required Readings and Supplementary MaterialsAnastasia Salter and Mel Stanfill, A Portrait of the Auteur as Fanboy: The Construction of Authorship in Transmedia Franchises (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2020).

Mizuko Ito, Daisuke Okabe and Izumi Tsuji (eds.), Fandom Unbound: Otaku Culture in a Connected World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012).

Rukmini Pande (ed.) Fandom, Now in Color: A Collection of Voices (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2020).

I assign a lot of reading in the hopes of providing you resources for your research and writing, not to mention a broader mapping of key debates and figures in the field. My expectation is that you will scan everything to get a broad sense of goals, theories, methodologies, and subjects. You then should drill deeper into at least one reading each week that you feel will be most related to your own interests in fandom studies and be ready to speak to it in class discussion,

Optional Readings and Supplementary MaterialsElizabeth Affuso, Suzanne Scott (erf.) Sartorial Fandom: Fashion, Beauty Culture, and Identity (University of Michigan, 2023)

The opening session of this class considers fandom in the context of larger trends in cultural studies and is considered a review of fundamental texts in the field. If you have not previously read any of the following, I recommend you take a look at these readings:

Angela McRobbie, “Settling Accounts with Subcultures: A Feminist Account,” http://www.hu.mtu.edu/~jdslack/readin...

Stuart Hall, “Encoding/Decoding” in Simon During (ed.), The Cultural Studies Reader (London: Routledge, 2007), https://faculty.georgetown.edu/irvine....

Raymond Williams, “Culture Is Ordinary” (1958).

Janice Radway, “The Readers and Their Romances,” Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy and Popular Literature (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1984).

Richard Dyer, “Judy Garland and Gay Men,” Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society (London: McMillian, 1986).

bell hooks, "The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators," in Black Looks: Race and Representation (Boston: South End Press).

Stanley Fish, “Is There a Text in This Class?” Is There a Text in This Class? (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980).

AssignmentsDialogic Writing: This semester, I want students to experiment with collaborative or dialogic forms of writing. You will be assigned a partner at the start of the term (someone who will bring a significantly different background and perspective from your own). Across the term, you will write a weekly series of conversational pieces where the two of you dig into issues which have been raised by the course materials, conversations, and experiences, but which will also draw on your own observations about fandom and participatory culture. These are not crossfire posts; your goal is to explore your differences but also to search for common ground. Each installment should be roughly 1,500 words (i.e. 750-1k words per contributor) and should include more than one round of back and forth exchanges. Assignments are due by 9 AM on the day the class meets.

Auto-Ethnography: You will write a short five-page auto-ethnography describing your own history as a fan of popular entertainment. You will explore whether or not you think of yourself as a fan, what kinds of fan practices you engage with, how you define yourself as a fan, how you became invested in the media franchises that have been part of your life, and how your feelings about being a fan might have adjusted over time.

Annotated Bibliography: You will develop an annotated bibliography exploring one of the theoretical debates that have been central to the field of fan studies. These might include those which we've identified for the class, or they might include other topics more relevant to the student's own research. What are the key contributions of fan studies literature to this larger field of inquiry? What models from these theoretical traditions have informed work in fan studies? This bibliography is intended to get you started with the secondary reading for your final project and should include a brief abstract of what you hope to explore through that project.

Presentation: Students will do a short 10-minute presentation of their findings for their final paper during the final week of class.

Final Paper: You will write a 15-20-page essay on a topic of your own choosing (in consultation with the instructor) which you feel grows out of the subjects and issues we've been exploring throughout the class. The paper will ideally build on the annotated bibliography created for the earlier assignment.

Some students may be asked to informally do share and tell on fandom practices or communities which surface in their dialogical writing. If you have something you want to present, please let me know. But recognize that this is not a course requirement – you can say no – and these presentations will not be graded.

Course ScheduleWeek 1: Fandom Studies - A Prehistory

Jonathan Gray, Cornel Sandvoss, and C. Lee Harrington, "Why Study Fans?" in Jonathan Gray, Cornel Sandvoss, and C. Lee Harrington (eds.), Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World (New York: New York University Press, 2007).

See recommended/ supplemental readings highlighted in this syllabus for further review materials.

NOTE: The opening session considers fandom in the context of larger trends in cultural studies and is considered a review of fundamental texts in the field.

Week 2: Fan Studies and Cultural Resistance

John Fiske, "The Cultural Economy of Fandom," in Lisa A. Lewis (ed.), The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media (New York: Routledge, 1992).

Joli Jensen, “Fandom as Pathology” ," in Lisa A. Lewis (ed.), The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media (New York: Routledge, 1992).

Camille Bacon-Smith, "Identity and Risk," Enterprising Women: Television Fandom and the Creation of Popular Myth (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992).

Constance Penley, "Feminism, Psychoanalysis, and the Study of Popular Culture," in Lawrence Grosberg, Cary Nelson, and Paula A. Treichler (eds.), Cultural Studies (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991).

Henry Jenkins, "Star Trek Rerun, Reread, Rewritten,” Fans, Bloggers and Gamers (New York: New York University Press, 2006).

Rebecca Wanzo, “African American Acafandom and Other Strangers: New Genealogies of Fan studies,” Transformative Works and Culture 20, 2015, http://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/699.

(Rec.) Stephen Duncombe, “Resistance” in Laurie Ouellette and Jonathan Gray (eds.), Keywords For Media Studies (New York: New York University Press, 2017).

(Rec.) Henry Jenkins, “Negotiating Fandom: The Politics of Race-Bending” in Melissa A. Click and Suzanne Scott (eds.), The Routledge Companion of Fandom Studies (London: Routledge, 2017).

(Rec.) Stephen Duncombe, “Resistance” in Laurie Ouellette and Jonathan Gray (eds.), Keywords For Media Studies (New York: New York University Press, 2017).

(Rec.) Henry Jenkins, “Negotiating Fandom: The Politics of Race-Bending” in Melissa A. Click and Suzanne Scott (eds.), The Routledge Companion of Fandom Studies (London: Routledge, 2017).

Week 3: From Engagement to Participation

Rhiannon Bury, “Fans, Fan Studies and the Participatory Continuum,” in Melissa A. Click and Suzanne Scott (eds.), The Routledge Companion of Fandom Studies (London: Routledge, 2017).

Henry Jenkins, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green, “The Value of Media Engagement,” Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture (New York: New York University Press, 2013), 113-150.

danah boyd, Henry Jenkins, and Mimi Ito, “Defining Participatory Culture,” Participatory Culture in a Networked Era (London: Polity, 2014), 1-31.

Alfred L. Martin Jr., “Surplus Blackness,” Flow, April 27, 2021, https://www.flowjournal.org/2021/04/surplus-blackness/.

Nancy Baym, "Participatory Boundaries," Playing to the Crowd: Musicians, Audiences, and the Intimate Work of Connection (New York: New York University Press, 2018).

Week 4: Tracing the History of Participatory Culture

Robert Darnton, "Readers Respond to Rousseau: The Fabrication of Romantic Sensibility," The Great Cat Massacre and Other Episodes in French Cultural History (New York: Basic, 2009).

Daniel Cavicchi, “Foundational Discourses of Fandom” in Paul Booth (ed.), A Companion of Media Fandom and Fan Studies (New York: Wiley Blackwell, 2017).

Alexandra Edwards, “Literature Fandom and Literary Fans” in Paul Booth (ed.), A Companion of Media Fandom and Fan Studies (New York: Wiley Blackwell, 2017).

andré m. carrington, “Josh Brandon’s Blues: Inventing the Black Fan,” Speculative Blackness: The Future of Race in Science Fiction (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016).

Helen Merrick, “FLAWOL: The Making of Fannish Feminisms,” The Secret Feminist Cabal: A Cultural History of Science Fiction Feminisms (New York: Aqueduct, 2019).

Week 5: Transcultural Fandom

Bertha Chin and Lori Hitchcock Morimoto, “Towards a Theory of Transcultural Fandom,” Participations, May 2013, http://www.participations.org/Volume%2010/Issue%201/7%20Chin%20&%20Morimoto%2010.1.pdf.

Bertha Chin, Aswin Punathembekar, Sangita Shresthova, “Advancing Transcultural Fandom: A Conversation,” in Melissa A. Click and Suzanne Scott (eds.), The Routledge Companion of Fandom Studies (London: Routledge, 2017).

Rukmini Pande, “Can’t Stop the Signal: Online Media Fandom as Postcolonial Cyberspace,” Squee From the Margins: Fandom and Race (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2019).

Week 6: The Case of East Asia

Henry Jenkins, “Transcultural Fandom” (Work in Progress).

Hiroki Azuma, “Database Animals” in Mizuko Ito, Daisuke Okabe and Izumi Tsuji (eds.), Fandom Unbound: Otaku Culture in a Connected World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012).

Sharon Kinsella, “Japanese Subcultures in the 1990s: Otaku and the Amateur Manga Movement,” Journal of Japanese Studies, Summer 1998.

Teguh Wijaya Mulya, “Faith and Fandom: Young Indonesian Muslims Negotiating K-Pop and Islam,” Contemporary Islam, 2021.

Ingyu Oh, Hyun-hin Lim, and Wonnho Jang, “What Is Female Universalism in Hallyu?: A Theoretical and Empirical Exploration” (Work in Progress, August 2023).

Miranda Ruth Larsen, “‘But I’m a Foreigner Too’: Otherness, Racial Oversimplification and Historical Amnesia in K-Pop Fandom,” in Rukmini Pande (ed.), Fandom, Now in Color: A Collection of Voices (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2020).

Mizuko Ito, “Contributors Versus Leechers: Fansubbing Ethics and a Hybrid Public Space,” in Mizuko Ito, Daisuke Okabe and Izumi Tsuji (eds.), Fandom Unbound: Otaku Culture in a Connected World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012).

Week 7: The Contested Social Dynamics of Fandom

Matt Hills, “From Fan Doxa to Toxic Fan Practices,” Participations, May 2018.

Benjamin Woo, “The Invisible Bag of Holding: Whiteness and Media Fandom,” in Melissa A. Click and Suzanne Scott (eds.), The Routledge Companion of Fandom Studies (London: Routledge, 2017).

Mel Stanfill, 2011, "Doing Fandom, (Mis)doing Whiteness: Heteronormativity, Racialization, and the Discursive Construction of Fandom," in Robin Anne Reid and Sarah Gatson (eds.), "Race and Ethnicity in Fandom," Transformative Works and Cultures 8 (special issue), 2011, https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/256.

Suzanne Scott, “Interrogating the Fake Geek Fan Girl: The Spreadable Misogyny of Contemporary Fan Culture,” Fake Geek Girls: Fandom, Gender and the Contemporary Culture Industry (New York: New York University Press, 2019).