Henry Jenkins's Blog

November 17, 2025

Frames of Fandom: An Excerpt From 'Fandom as Consumer Collective'

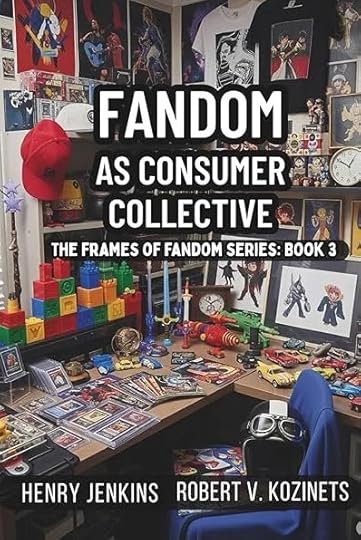

Henry Jenkins and Robert Kozinets recently released the third book in their Frames of Fandom book series, Fandom as Consumer Collective and the fourth book, Fandom as Subculture, will be published before the end of 2025. Altogether, fifteen volumes have been planned in this series and are at various stages. The books are being self-published and print-on-demand on Amazon. This post provides an excerpt from the third book, which examines how consumer collectives overlap with, include, and also transcend subcultures and audiences to form a new type of social grouping, simultaneously engaged with and critical of consumer culture.

BUY FRAMES OF FANDOM READ ABOUT THE FRAMES OF FANDOM SERIES AT POP JUNCTIONS About Fandom as Consumer Collective

READ ABOUT THE FRAMES OF FANDOM SERIES AT POP JUNCTIONS About Fandom as Consumer CollectiveConsumer collectives overlap with, include, and also transcend subcultures and audiences to form a new type of social grouping, simultaneously engaged with and critical of consumer culture. The book explores this tension—between individual consumer and social collective, participation and resistance, community and market, consumer and producer—unpacking how consumer collectives challenge existing commercial norms while also embracing the cultural opportunities they offer. It demonstrates a bridging of unhelpful disciplinary divides and calls for an enhanced appreciation of the creative, critical, and transformative potential of consumer collectives. Furthermore, it builds and then demonstrates an integrated conceptual toolkit for better understanding a world where passionate consumers participate in collectives that provide them with a deep sense of fulfillment. For scholars, practitioners, and fans alike, this book explores fandom as a critical engine of cultural production, a source of creative collective effervescence, and a force for cultural expression in an increasingly fragmented world.

This selection uses three publications targeted at Star Trek fans (and others) to illustrate the different ways fan works might relate to consumer culture.

Chapter 9: Canaries in the GemeinschaftAll About Star Trek Fan Clubs

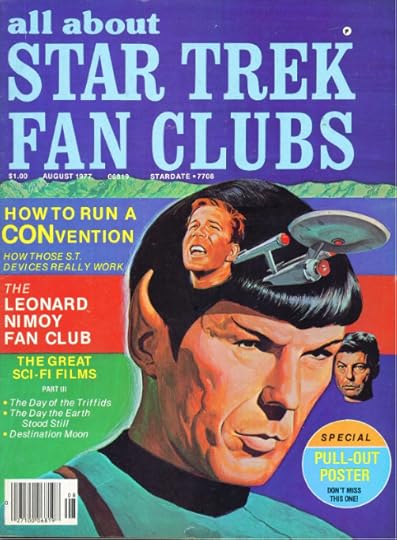

Figure 9.1: All about Star Trek Fan clubs magazine cover, circa 1977

We begin with an example from Rob’s personal collection of memorabilia (Henry has a copy of it as well!). It is a magazine called All About Star Trek Fan Clubs, whose cover is pictured, and a sample table of contents is provided. We chose it because it exemplifies an intriguing and important aspect of consumer collectives, including fandom: the ability of these collectives to combine both economic value, as indicated both by the price tag on the magazine’s cover and the fact that Rob bought it in his neighborhood convenience store, and the cultural values it possessed that derive from its interaction within a communal or gift economy.

The theory underlying this understanding goes back to Tönnies’ influential book, which postulated a core division in social groups. The first form, Gemeinschaft, translates to community in English and has many of the same positive connotations. In Kozinets (2002, p. 21), Rob explained the communal ideal as “a group of people living in close proximity with mutual social relations characterized by caring and sharing,” placing its origins within “the deep trust and interdependence of family relations,” and linking it to Robert Putnam’s (2000) theory of dwindling social capital and the need for a renewed gemeinschaft-like sense of belonging, civic engagement, and social contribution.

Figure 9.2: All about Star Trek Fan clubs magazine cover, circa 1976

The second type of social group, Gesellschaft, is the dark sister in this theoretical story. The English word society only roughly captures the connotations of Gesellschaft. Gesellschaft describes a relational situation opposite to that of familiar or familial relations. Where families are informal and help one another, societies are formal, contractual, and transactional. When people interact in a large marketplace, they are interacting with the roles and rules—the social logics—of a Gesellschaft: keeping a distance, getting the best deal, and making a profit. Gemeinschaft communities prioritize caring for and sharing with those within the group, whereas Gesellschaft markets emphasize transactions with outsiders where each player is trying to get a better deal at the other’s expense. Both settings are characterized by their own power dynamics. However, the divergence in social logics appears to account for the historical spatial and temporal confinement of markets to specific locales, occasions, and roles. People and institutions have sought to maintain a clear separation between the more ruthless and exploitative social logics of the Gesellschaft market and communal social institutions like home and family.

With the advent of industrialization and later, postindustrialization, market influences have increasingly permeated aspects of life traditionally dedicated to communal relationships. Times, spaces, and roles once exclusive to community-oriented interactions now often accommodate market-driven activities. Theorists like Biggart (1989), Frenzen and Davis (1990), and Granovetter (1985) have argued that markets and communities—Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft—are now interdependent and even embedded within one another. This encroachment of market logic into communal spheres has led to criticism that the foundational communal values of caring and sharing are being eroded, as market-oriented self-interest reshapes the nature and quality of communal relations, making the actualization of the caring and sharing communal ideal in modern societies ever more challenging.

Communities and Markets: Contrasting yet Interconnected

A substantial body of research on consumer collectives and fandoms has explored these interconnections. In Jenkins (1992), Henry observes that many media fan communities establish nonprofit trade relationships to create a sense of shared communal experience. In Kozinets (2001), Rob suggested that Star Trek fans' distinction between the commercial and the sacred reflects a broader cultural tension between consumer communities and markets. Henry and Rob, along with others too numerous to mention, tended to hold the fort, noting the differences and tensions between these two pervasive and historically important forms of social logic.

Conversely, another strand of research suggested that the relationships between communities and markets might be less problematic than they seemed. Studies on various communities, including river rafters (Arnould and Price 1993), Harley-Davidson subcultures (Schouten and McAlexander 1995), and Macintosh, Saab, and Bronco brand communities (Muñiz and O’Guinn 2001), show little tension between consumer communities and markets. As we noted above, Schouten and McAlexander suggest that marketers and subcultural communities could pursue a symbiotic relationship, implying benefits to both of them. Perhaps even more strongly, Muñiz and O’Guinn (2001) suggested that brands and communities had merged, a transformation they cast as generally positive.

Now, let’s start to think about what went into the “All About Star Trek Fan Clubs” magazine and what else it tells us about how market and communal logics work. We can see how the magazine, despite being a widely distributed commercial product that was sold for profit, is deeply intertwined with the nonprofit, gift economy-driven elements of the Star Trek fan community. That interrelationship demonstrates some of the complexities inherent in many consumer collectives, which are hybrids where market and communal forces coexist and influence each other.

First, it is crucial to position this magazine in relation to the broader theoretical frameworks we have established. Star Trek fandom is a quintessential culture of consumption, as we have defined it—a vast, interconnected system of commercially produced images (the starship Enterprise, Spock's ears), texts (the episodes, films, and novels), and objects (phasers, uniforms, and model kits). This magazine, as a piece of merchandise, is undeniably one of those objects, produced by a media company whose goal is to profit from mass culture. By its very nature, popular culture depends on mass culture, and thus fandom is interrelated in its very DNA with the market logics of contemporary corporate capitalism.

However, the magazine occupies a fascinating, paradoxical space. Like fan fiction, its content and the core of its appeal are heavily reliant on the gift economy that fuels the fan community. It makes the legitimating claim that it is “made by fans for fans” (and there is no reason to doubt it, either). Although the eye-catching cover illustration features the trinity of Classic Trek characters and the iconic U.S.S. Enterprise, the magazine is not dedicated to Star Trek, per se. It is dedicated to Star Trek fan clubs—although, strangely, fans never graced any of the covers of its six-issue run. The Fanlore wiki describes its content as “a fusion of professional boosterism of Star Trek and its actors, and of fandom boosterism” (Fanlore, 2024). In this fusion, the magazine acts as a node, a physical artifact that channels the global flows that Arjun Appadurai (1990) describes. It circulates ideas about fan identity (the ideoscape), showcases fan art and stories (the mediascape), and provides the organizational know-how for fan-run conventions (the technoscape), all while being part of a commercial flow (the financescape).

The magazine’s content reveals its role as a bridge, designed to guide what we might call the "fandom-curious" from individual engagement into deeper, more structured forms of collective life. In 1977, before the mass availability of the Internet, a fan's experience could be isolating. The magazine's articles serve as a direct intervention in the size and intimacy dynamics of the collective. The first major story mentioned on the cover, "how to run a convention,” serves as a type of blueprint for transforming an unstructured gathering into a highly structured, self-governing event. It provides the tools for fans to scale up their activities from small, intimate groups into larger, more organized forms.

The second cover story, about a fan club dedicated to Leonard Nimoy, illustrates another key function: making specific fan collectives visible and accessible. By featuring this club and a fan painting of Mr. Spock, the magazine takes an unofficial, grassroots entity and grants it a form of official legitimacy by placing it within a professionally produced, commercial text. It serves as an advertisement for a specific subgroup within the larger fandom, offering a pathway for an individual fan to increase the intimacy of their involvement by joining a dedicated group. This process of highlighting and legitimizing unofficial fan activity is a primary way that the commercial marketplace identifies and engages with the energy of its most passionate consumers.

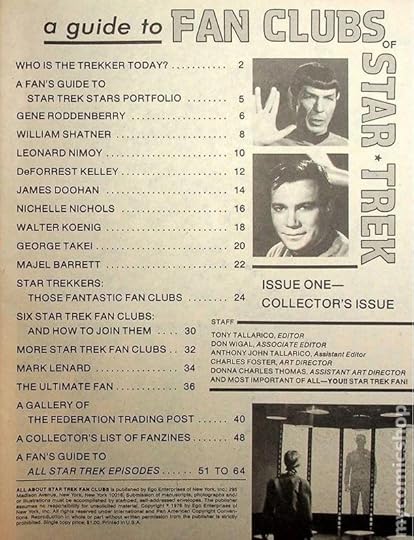

Figure 9.3: Star Trek Official Fan Club magazine cover

The final cover story, offering reviews of three "great sci-fi films," is particularly revealing. It acknowledges that fans are often "omnivorous" in their tastes and do not exist within a single, hermetically sealed culture of consumption. As we and numerous others have found, many Star Trek fans are not exclusively loyal to the show. This article functions to deliberately broaden the boundaries of the Star Trek culture of consumption, linking it to the wider universe of science fiction fandom, emphasizing the intersection of different cultural consumption circles, as we depict in Figure 7.1. The article on sci-fi films acts as another type of bridge—encouraging fans to explore the adjacent territories and demonstrating the fluid, overlapping nature of these cultural worlds.

Upon examining the table of contents, the mission to shape fan identity becomes even more evident. The lead story, “Who is the Trekker today?,” is an explicit act of identity construction. By using and validating the (then-preferred) term “Trekker,” the magazine tells its readers, ‘Look, others might call you a Trekkie, but you are a Trekker. You can take your fandom seriously. We have worked these things out for you, and there is a community waiting for you.’ Following the articles that profile the show's creators and actors, the magazine shifts its focus to the main topic: “Star Trekkers: Those Fantastic Fan Clubs.” It features six specific fan clubs, offering instructions on how to join them. By profiling an “ultimate fan,” listing collectible fanzines, and providing a 13-page “fan’s guide” to all 79 original episodes, the publication provides a comprehensive toolkit. It offers a prepackaged identity, a directory of collectives to join, and the cultural capital (episode knowledge) needed to participate, effectively serving as a primer for building a deeper, more structured, and more socially connected fan life.

We can usefully compare the “All About...” magazine with another, much longer-lived publication, Star Trek: The Official Fan Club magazine, which was renamed Star Trek Communicator after its 99th issue. The most important word to note regarding the magazine’s title is the term “official.” The magazine actually began as a fan publication created by Dan Madsen at the age of 18 as an outgrowth of the fan club he started. Madsen’s publication found its way to Paramount, who asked him to license the publication—and, later, to make his fan club the “official” one. As the cover featured in Figure 9.3 shows, the publication’s focus is not actually about fan clubs per se, but the Star Trek franchise itself. The cover in the figure offers fans exclusive information such as “first photos from the set of Star Trek: Generations.” But it does not offer them information about fandom and how it operates or how to identify oneself as a fan, although Dan Madsen—who is also a devoted Star Wars fan, fan organizer, and publisher—continued as publisher of the magazine until it was sold and stayed on until it was abandoned by its new owner.

Official publications are beholden to rights holders and as a consequence, they are policed to ensure that nothing occurs that might raise the risk of damaging the value of the franchise. Official organizations typically support affirmational forms of fandom (see Defining Fandom) but allow much less space for unauthorized and transformative fan activities. Zines, in the old days, might be sold under the table at a Creation con but other fan conventions center around fan works, which are openly displayed and celebrated. Fan authors have the opportunity to read excerpts from their works. Huge piles of new and vintage fanzines may be displayed on the dealer’s tables rather than the kinds of authorized merchandise that are sold at, say, San Diego Comic-Con. The same fan may go to official and unofficial conventions but an experienced fan knows what to expect from each.

We can see from this analysis that the “All About” magazine, although it is a published market offering, serves the function of helping to educate and potentially build individual fanships into collective fandoms. It provides a socializing and enculturating platform for individual fans. It offers them DIY and how-to-type guides on things like starting a convention, broadening their tastes and knowledge, buying merchandise, and collecting fanzines. It caters to fans' sometimes eclectic tastes, such as featuring poetry written by Classic Trek star and fan favorite Nichelle Nichols, something that would not be likely to appear in the official magazine. The general fan community benefited from the presence of the “All About” magazine. The All About magazine's existence generates value for the fan community by facilitating connections, circulating knowledge, and providing a sense of shared identity. This value generation aligns with the communal aspects of a gift economy, where the focus is on mutual benefit and shared resources.

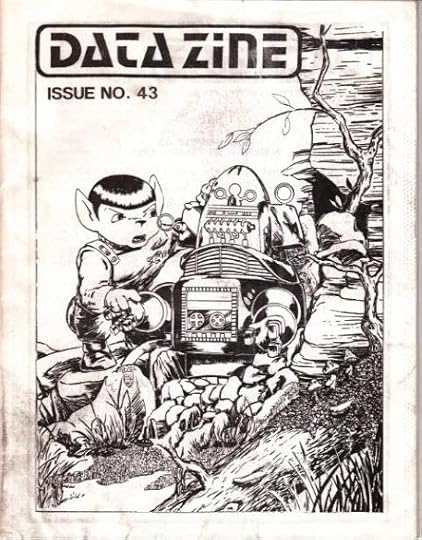

Figure 9.4: Datazine zine cover

Datazine: Unofficial and UnboundWe might contrast both of these publications with Datazine, which, from 1980 to 1991, served as a key resource for—rather than about—the fan fiction community (see Figure 9.4). Unlike the other two publications, which engaged to some degree with the commercial sphere, Datazine was totally unauthorized—by any official group, including the copyright holders. Datazine was closer to Factsheet Five which had been central to the larger zine movement coming out of the underground press efforts of the 1960s counterculture. The magazine never sought nor needed a mass audience, as long as it maintained the support of highly motivated readers who were themselves often also producing its content. Witness the fact that it makes extensive use of fan slang and jargon: you have to be invested in the community to understand what’s being said. Put differently, Datazine could be insular and exclusive. Unlike the commercial publications, Datazine had no incentive to broaden the ranks of fandom. Datazine was uninterested in formal fan clubs unless they had grassroots publications to offer. Datazine published notices from fan editors about their publications, where you could order them, and how much they cost. In one sense, these were advertisements, but the underlying logic was that of a gift economy since, in most cases, the zines were sold at cost.

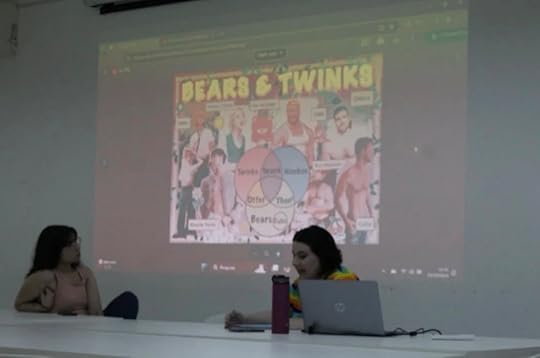

Henry found Datazine to be a key resource when he began his work on Textual Poachers (Jenkins, 1992). The world Henry described in that book was largely circumscribed by the contents of this publication in ways he would only belatedly recognize. At that point, what had begun as a female fandom around Star Trek was expanding to incorporate more and more other fan objects, although mostly within the realm of genre films and television series. Thus, a passion for Star Trek led to interests in Star Wars, the original Battlestar Galactica, the British Blake’s 7, and so forth. But it also includes cop partner shows like Starsky and Hutch or the British series, The Professionals. Datazine also played important roles in identifying and codifying genres of fan fiction. Kirk/Spock, understood as a very particular relationship, was expanded there to the concept of slash, which could incorporate any number of other same-sex partnerships from across the spectrum of popular media. Some of the publications supported by Datazine were multimedia publications where smaller and diverse fandoms worked together. These zines might introduce readers to shows they had never heard of before, but if readers followed particular writers and editors, their range of fan objects might broaden. Datazine paved the way for today’s even more inclusive fan fiction archives like Archive of Our Own (discussed in Fandom as Participatory Culture).

Datazine also provided other resources in support of fan creators, such as advice columns and, somewhat more controversially, reviews of fanzines. Fans had a heated debate about whether reviews were negative, especially in a public context, or whether they could be vital in nurturing the creative development of the fans involved. Were reviews—which often imply a consumer orientation (“should you read this story?”)—consistent with the caring and sharing ethos of the fan gift economy?

The readers were assumed to be invested in building up the infrastructure of a fandom perceived to be a loosely affiliated network of people who both consumed and created fan works. In this realm, Datazine’s low production values were a badge of honor. Datazine, thus, has a different conception of how fandom was structured than publications that delimited themselves around Star Trek, sought to support the interests of formal fan clubs, and were primarily oriented around commercial efforts rather than grassroots publications. Datazine was very much a byproduct of a counterculture conception of DIY production as applied to the realm of fandom.

Datazine thus represents a fascinating and powerful form of consumer collective, one that can be understood through the frameworks we have developed. It stands as a prime example of a self-governing or grassroots commons formation—fiercely unofficial and valuing its unstructured, networked nature over any formal hierarchy. This structure directly influenced its relationship with size and intimacy.Datazinedeliberately operated at the small-scale, high-intimacy end of the spectrum, in contrast to the commercially oriented magazines that sought to expand their audience using the market logic of the gesellschaft. Its use of insider jargon and its focus on a gift economy were cultural mechanisms used for maintaining a manageable size and cultivating deep, trusting bonds among a core group of highly dedicated participants. The zine acted as a gatekeeper, prioritizing the quality of connection among initiates over the quantity of a mass readership. In doing so, it became the connective tissue for a multitude of overlapping cultures of consumption. While the other magazines primarily focused on the singular Star Trek culture of consumption,Datazinecurated a space where fans could fluidly move between the Star Trek,Starsky and Hutch, andBlake’s 7cultures, among others. The unifying principle was not a single fan object, but a shared passion for a specific creative practice—the writing and circulation of fan fiction—which itself became a vibrant, meta-level culture of consumption, complete with its own distinct objects (the zines), texts (the stories), and social norms.

Henry Jenkins is the Provost Professor of Communication, Journalism, Cinematic Arts and Education at the University of Southern California. He arrived at USC in Fall 2009 after spending more than a decade as the Director of the MIT Comparative Media Studies Program and the Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities. He is the author and/or editor of twenty books on various aspects of media and popular culture, including Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture, Hop on Pop: The Politics and Pleasures of Popular Culture, From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: Gender and Computer Games, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, Spreadable Media: Creating Meaning and Value in a Networked Culture, and By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism. His most recent books are Participatory Culture: Interviews (based on material originally published on this blog), Popular Culture and the Civic Imagination: Case Studies of Creative Social Change, and Comics and Stuff. He is currently writing a book on changes in children’s culture and media during the post-World War II era. He has written for Technology Review, Computer Games, Salon, and The Huffington Post.

Robert V. Kozinets is a multiple award-winning educator and internationally recognized expert in methodologies, social media, marketing, and fandom studies. In 1995, he introduced the world to netnography. He has taught at prestigious institutions including Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Business and the Schulich School of Business in Toronto, Canada. In 2024, he was made a Fellow of the Association for Consumer Research and also awarded Mid-Sweden’s educator award, worth 75,000 SEK. An Associate Editor for top academic journals like the Journal of Marketing and the Journal of Interactive Marketing, he has also written, edited, and co-authored 8 books and over 150 pieces of published research, some of it in poetic, photographic, musical, and videographic forms. Many notable brands, including Heinz, Ford, TD Bank, Sony, Vitamin Water, and L’Oréal, have hired his firm, Netnografica, for research and consultation services He holds the Jayne and Hans Hufschmid Chair of Strategic Public Relations and Business Communication at University of Southern California’s Annenberg School, a position that is shared with the USC Marshall School of Business.

November 4, 2025

“I May Be Circling the Drain But I Have a Few Steps in Me!’: Dick Van Dyke, ‘Mary Poppins’ and Playful Aging

The following blog post is based on remarks I presented as a keynote speaker at The Older, The Better! Aging Celebrity in Contemporary Media and Sport Contexts, PRIN 2022 PNRR “Celebr-Age” Final Conference organized by Ylenia Caputo, Simona Castellano, Antonella Mascio, Roy Menarini, Maurizio Merico, Sara Pesce, Mario Tirino at Universita di Bologna in September.

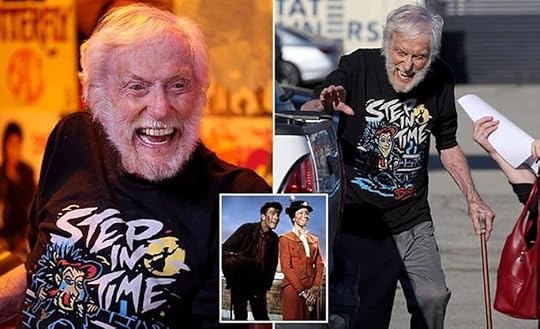

Dick Van Dyke will turn 100 this December and this past year has seemed like one big victory lap, starting with the extraordinary moment when a production number of “Step In Time” on Dancing with The Stars (ABC) concluded as this particular star stepped out onto the stage and (with an assist from two chorus boys) danced a few steps. The crowd went wild and so did the internet, as the scene brought a rush of nostalgia for anyone who grew up with Walt Disney’s Mary Poppins and Van Dyke’s performance of Bert the Chimney Sweep. I count myself among them. Mary Poppins was the first film I remember seeing in the theater and what a theater it was – Atlanta’s fabulous Fox Theater, an arabesque themed movie palace from the 1920s.

Mary Poppins plays a central role in my recent book, Where the Wild Things Were: Boyhood and Permissive Parenting in Post-War America. I want to begin this blog post where that book’s discussion of the film left off or perhaps more accurately where the book began, since I used the film to ground the book’s introduction of the concept of permissiveness, which turns out to be useful to think about the current moment in Van Dyke’s life (and mine) also. I am an aging Boy in a Striped Shirt, admiring Van Dyke’s dexterity all the more at a point where my own mobility has been limited by symptoms associated with diabetes and neuropathy.

In the book, I use this scene where the Banks household discusses how to hire a new nanny, with both the father (embodying prewar patriarchal norms focused on disciplining the child) and the children (embracing a more pleasure-centered and permissive style then coming into popularity through the widespread success of Benjamin Spock’s Baby and Child Care). We might map the contrast between the two approaches through this chart from another popular child-rearing guide of the era by Rudolf Dreikurs in 1964, the same year Mary Poppins was released.

Autocratic Parenting (Mr. Banks)Authority Figure Power Pressure Demanding Punishment Reward Imposition Domination Seen and Not Heard YOU do because I said soHere, and throughout the rest of the song, the key words and concepts—“precision,” “firmness,” “discipline,” “rules,” on the one hand and disorder and moral disintegration on the other—come directly from the discipline-centered child-rearing advice of the early 20th century. Ada Hart Arlitt’s The Child From One to Six (1930) warned that the child “will not know that there are laws that govern the universe unless he knows that there are laws that govern the home.” The home was to be regulated not by “mother love” but by the “kitchen time-piece.” Here, we speak to a core concern of the behaviorist model: the idea that children should be fed and put to bed on a fixed schedule rather than giving over to their demands or desires.

As in the pre-war models, the best methods for achieving these goals required the father to be the head of the household and for those under his “command” to maintain authority over the young. Going hand in hand with this emphasis on patriarchal power within the home is a distrust of maternal sentimentality or what Banks refers to as “the slipshod, sugary, female thinking they get around here all day long.” Banks is portrayed as seeking a polite distance from his children: “I'll pat them on the head and send them off to bed.”

Democratic Society (The Children)Knowledgeable LeaderInfluenceStimulationWinning CooperationLogical ConsequencesEncouragementSelf-determinationGuidanceListen! Respect the childWE do it because it is necessaryThe conversation between parents and children models something closer to the family council Dreikurs (1964) describes: “Each member has the right to bring up a problem. Each has the right to be heard. Together, all seek for a solution to the problem and the majority opinion is upheld” (p. 301). The children assume that they have the right to contribute to solving the problem and that their insights will be helpful to the adults. The children’s attempt to assert their voice in the process is only heard because their mother insists that the parents should listen to what they have to say.

The children’s criteria emphasize an affectionate relationship, the opposite of the anti-sentimentalist approach advocated by Watson and Mr. Banks. If Banks wants a nanny who can give commands, they want one with a “cheery disposition.” She is defined by the ways that she engages with them through jokes, songs, outings, and games, and not through the expectations she places upon them. She is to win their cooperation through what she permits and the guidance she offers. And as if to dramatize this process of winning cooperation, the next verse functions as a negotiation in which the children agree not to misbehave if the nanny agrees to better respond to their needs.

As defined in my book, permissiveness:

Uses empathetic reflection to “take stock” and attempt to understand children’s motivations and drivers

Values children’s sensuality, curiosity, push for independence, passion, playfulness as part of how they process the world

Seeks to protect the rights of children to find their own voices, to pursue just solutions, to engage democratically with others in their own community

Offers opportunities for children to achieve catharsis by working through emotional conflicts via expressive means, such as drawing pictures, writing stories, acting them out using dolls or other household materials.

Seeks to minimize conflict by decreasing the use of authoritative statements in favor of discussions and explanations

Seeks indirect rather than direct means to shape children’s characters

Is known for what it permits and accommodates rather than what it disciplines, constraints, limits and thwarts

Gives children security and freedom to work through their own problems, watches from distance, provides resources when needed

Embraces play as a mode of learning and as a means of communication, especially between parents and children

My book discusses the ways permissiveness permeated the representations of children—especially boys—in the children’s fictions of the era. Consider, for example, this sequence from one of my favorite films, 5000 Fingers of Dr. T, written by Doctor Seuss, as a young boy in a striped shirt proclaims his rights to be treated with the same respect owed to adults.

Alongside Spock, the other major advocate on the permissive family ideal was the grandmotherly Margaret Mead who was preoccupied with the idea that changing the dynamics of the American family was the best way to foster a more democratic culture. American family life, Mead argued, had been shaped by several decades of disruption. First, there had been the immigrants who came to America in the late 19th and early 20th century; their children had rejected old world traditions in order to try to become more American. There were also the dislocations felt by families, like my own, that had moved to the city from the country, shifting from agriculture-based to industrialized lifestyles. Then, there was the generation which had postponed starting a family during the Depression and the war. Consequently, baby boom parents had little to no memories of what the typical American family had looked like before. Mead wrote in November 1945, “this leaves two courses open to them, either to fashion a pattern out of partial remembrance of the war years or to make a new pattern for themselves altogether” (p. 91). What will happen, Mead (Unpublished, 1945) asks, “if the young people of this generation realize that the world is theirs for the making, that because of the break between peace and war, they can -- if they wish -- reject the whole model which their brothers and sisters -- living in another world -- have given them in the past five years?” Developing this new model will require intentionality: Otherwise, she fears:

It is this younger group who will be most lost, most groping, most likely to take short cuts and easy solutions, most likely to become a ‘lost generation.’ The only way in which this can be prevented is to help these young people think it through, give them a chance to discuss the whole problem, to realize why they are at sea, to talk over the kind of life their elder brothers and sisters have been living, to label those aspects of it which don’t belong in their lives now….There is no older generation who can give these models to them. The most we can do is to help them find them themselves. (Mead, 1945, Unpublished)

Writing for Harpers, also in 1945, Mead calls upon “the symbol-makers, the writers, the artists, the radio broadcasters and the filmmakers” to be “enlisted” into producing new narratives, the shared designs out of which the post-war family would be constructed.

And the “symbol makers” responded by producing works, such as Mary Poppins, which consciously modeled what a permissive household might look like. In “Just a Spoonful of Sugar,” Mary describes her use of “reverse-psychology,” through which work becomes less painful if embraced as a form of play and medicine tastes better if disguised by sucrose.

In both Mary Poppins and Sound of Music, Julie Andrews embodied the ideals of the period, freeing children from the constraints imposed upon them from conservative fathers, allowing them to sing and play and go on outings, and gradually bringing the father to embrace the new values of the postwar family.

A recent Disney film stressed the way the story was about “Saving Mr. Banks” as much as it was about setting the family right. And in practice, permissive culture sought to place greater demands on adults to listen to, empathize with, and achieve understanding of their children. Often, the parenting guidebooks of the era stressed the importance of the father becoming a playmate for his children, a practice which not only brought a strong male presence into their lives, but also gave the father a way to rejuvenate himself at the end of a hard day at work. Similarly, in 5000 Fingers, we see the adult male’s potential to be an ideal father for the orphaned boy by observing how they played together.

Advertisements of the period warned fathers that if they did not take time to play with their children now, then it would be soon too late. We can see examples of this discourse in a Kodak advertisement. Or, again, in a popular song about fatherhood performed by folk singer Harry Chapin.

If the plot of Mary Poppins works to get the workaholic Mr. Banks, who is named for the institution where he has dedicated his life, to go out and fly a kite with his children, the Van Dyke character, Bert, models what it might mean for an adult to enjoy a more playful and imaginative life. It is Bert who draws chalk pictures on the sidewalk that are so immersive that the children and their Nanny can jump into them and have wild adventures together. It is Bert and his Uncle Albert who lets loose with wild laughter which sends them floating up to the ceiling. And it is Bert who teaches the father that he needs to be more attentive to the emotional needs of his children.

And much as Mary Poppins teaches the children that “just a spoonful of sugar makes the medicine go down,” Bert and his Chimney Sweep friends model what a more playful relationship to work might look like. And, ironically, it was Dick Van Dyke who also portrayed the most fossilized version of adult work, the ancient old man who is the elder leader of the board of the Bank of England. Here, we see a still relatively young Van Dyke imagining what it would be like to be elderly, having, like Charles Dickens’ Ebanezar Scrooge, spent his life dedicated to little more than the pursuit of gold or in this case, tuppence.

In hindsight, it is clear that Mary Poppins had as much to teach us about being an adult as it had to say to us as Baby Boom era children, if we only knew where to look.

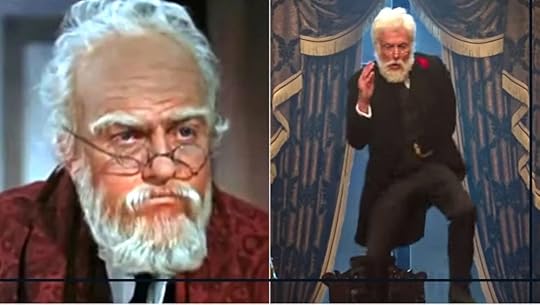

I want to argue that a new phase in Van Dyke’s life can be seen in Mary Poppins Returns when he steps on screen, now himself an older man, singing and dancing, having grown into the bank president who looks more like the original than we could have anticipated. And this becomes the persona which Van Dyke adopts more and more in his public appearances. As the character explains, “I may be circling the drain but I have a few steps left in me.”

dick van dyke in Mary poppins returns (2018)

Each new birthday requires that Van Dyke, now widely seen as a national treasure, flash another broad smile and looking like he will burst out laughing at any moment. We already know how much he loves to laugh. While Van Dyke played many roles across his career, it is the part of Bert to which he returns again and again. Photographs show him in T-Shirts which evoke catch phrases from Mary Poppins, now repurposed to reflect ironically on the process of aging. He and Bert have fused with the star sign becoming a living, breathing intertextual reference back to his most beloved role.

For his 90th Birthday, he stood on a balcony in Disneyland being serenaded by throngs of the public below and presided over the opening of a new cafe dedicated to memories of the film.

Dick Van Dyke celebrates his 90th birthday at disneyland

For his 96 birthday, Van Dyke released a music video where he dances with his considerably younger wife and gives a ribald version of “Everyone loves a lover.” Again, he demonstrates his physical control of his body as well as the fact that he still is a clown who does not take himself too seriously. A news segment commemorating his 98th birthday includes references to his roles in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and the Dick Van Dyke show but it starts with “Jolly Holliday” and references Mary Poppins multiple times.

Much as Bert in Mary Poppins models what a permissive father might be, Van Dyke’s later appearances showcase to an aging Baby Boom audience what playful aging might look like. He’s still got it, baby, and so do you, he seems to say, as we watch from our arm chairs and imagine what it might be like to “step in time” with a chorus of always cheerful chimney sweeps. In Entertainment and Utopia Richard Dyer (1977) tells us that musicals model what utopia feels like through their appeals to spontaneity, plentitude, energy, and the other virtues they associate with entertainment. As my own 68th birthday approaches, I would just love to move through the world with less numbness in my feet, less stiffness in my knees, and less discomfort in my chest.

Van Dyke’s 100th birthday approaches in just a month and a half and he seems to be joining George Burns and Betty White as an example of a star who comes to perform what it is like to break the century boundary. Happy Birthday, Dick, and may everyday continue to be a “Jolly Holiday.”

Biography

Henry Jenkins is the Provost Professor of Communication, Journalism, Cinematic Arts and Education at the University of Southern California. He arrived at USC in Fall 2009 after spending more than a decade as the Director of the MIT Comparative Media Studies Program and the Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities. He is the author and/or editor of twenty books on various aspects of media and popular culture, including Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture, Hop on Pop: The Politics and Pleasures of Popular Culture, From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: Gender and Computer Games, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, Spreadable Media: Creating Meaning and Value in a Networked Culture, and By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism. His most recent books are Participatory Culture: Interviews (based on material originally published on this blog), Popular Culture and the Civic Imagination: Case Studies of Creative Social Change, and Comics and Stuff. He is currently writing a book on changes in children’s culture and media during the post-World War II era. He has written for Technology Review, Computer Games, Salon, and The Huffington Post.

October 23, 2025

IPDW2025—(Re)designing Production: An Interview with Alex McDowell

TL: Alex, thank you for sharing your time and experience in this discussion to celebrate International Production Design Week. I’d like to start by reflecting on the history and transformation of production design in the filmmaking process. Throughout your career, have you experienced much change in production design and the role of the production designer in filmmaking and screen storytelling?

AM: Hi Tara, thanks for your questions!

There have of course been huge changes in our craft since I started, but not enough to fully integrate Production Design in the opportunities of non-linear production. Rick Carter has one of my favorite quotes for all of us: “the production designer's first job is to design the production”.

This has always been true, and it's our responsibility as designers to take it on. But the context has changed radically. For over 20 years we’ve been pushing for a change in the relationship between the front end and the back end of production and since the early 2000s we developed an art department workflow that aligned closely to visual effects. But the reality was that the pre-production assets that framed the shoot tended to be discarded and then rebuilt in post.

With virtual production, non-linear production has kicked in. Now our work is to use the tools we have—and keep them up to date—to design the virtual production. Now we take responsibility to update the production design/art process to drive the full breadth of the production, which means a different make-up of the art department. Increasingly, we are working with illustrators using 3D and game platforms, engineers, designers in Rhino or Maya to drive models informed by photogrammetry scans from drones in a location, reference images to blender or rapid fabrication, etc. At this point, the design development can be distributed to any of the appropriate departments—construction, location, stunts, set dressing, DP, VFX, virtual production—and director.

The art department increasingly needs polymaths. Schools need to teach accordingly, and designers need to hire appropriately. It’s also worth saying that a lot of these processes no longer apply only to mega-productions. The smallest budget can use a drone to scan a location and a single designer to accurately add a set extension.

Across your career you have worked as a production designer on a range of different projects, including Madonna’s early music videos, The Crow (1994), The Fight Club (1999), Minority Report (2002), Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005), Watchman (2009), and Man of Steel (2013). How would you describe your own approach to production design and has this changed across your career?

In addition to the previous response, the only thing to add is obvious: every show has different demands. We learn from every show and apply that learning to the next. The designer probably has to adapt to the nuance and context of a script and direction more fully than almost any other department—materials change, crew skills change, vendors change, tools change, location resources change and your knowledge updates exponentially.

Minority report (2002)

Man of steel (2013)

Your work has been instrumental in the development of a world-driven approach to storytelling, whereby the world is designed prior to and beyond the boundaries of a script. This seems to enable a stronger relationship between production design and other filmmaking crafts across the storytelling and production process. What do you see to be the role of the screenplay within this approach and how does this redefine story ideation, authorship, and collaboration in screen production?

What we have learnt simply is that non-linear production is possible when storytelling meets narrative design. Every world provides unique context and logic from which any number of story paths can evolve. Ideation, authorship, and collaboration in screen production become a single workspace for development. Production design in this context provides an immersive and adaptive container that much more closely mirrors the conditions of production start to finish for all the makers of a film and evolves accordingly.

minority report (2002) ‘precogs temple’

World building requires an interdisciplinary approach to storytelling, within filmmaking departments and with experts in other fields like computer science, animation, and culture. This seems to require a reimagining or reorganization of the traditional film development and production process. Do you see evidence of this kind of reorganization happening in the industrial context? And is it possible for traditional filmmaking processes to still embrace world-building principles without a complete restructuring of the production process?

Industrial is the right word. We are finally moving from a 19th century Victorian-industrial linear production process to one of the most agile and effective non-linear practices in the world. I’ve experienced a broad range of industries outside entertainment media, and our industry can compete with any of them. But it absolutely requires a restructuring of the traditional production process. This assumes that the traditional creative skills remain and are still vital, but we all have to work with new tools as we always have. These tools speak to each other in ways that make ideation and creativity more intuitive, closer to our imagination, and we have to adapt to take advantage of that. We are biological, cellular creatures, but we’ve been forced to work with straight lines. It’s fun to see us getting closer to our intuitive selves.

Your work sits at such an interesting intersection between design, technology, and education and you have been instrumental in promoting the critical role that production design plays in world building and storytelling. Can you discuss some of the work you have been doing as part of the World Building Institute at USC, particularly the Project JUNK consortium? Why has it been so important for you to also work across education and support the development of future world builders? What has been the most rewarding part of working at the interface of industry and education?

Most rewarding and valuable continues to be the demands of the students when they see that the edges of their work are unconstrained, and when they understand that world building demands cross-disciplinary co-creation. I hope we are developing the base for new generations of polymaths, who can work across media, in industries within and outside entertainment, and in fields that do not yet exist. If we are able to focus on the need to break down the silos of disciplines and understand the power of folding together the craft skills and toolsets across media, we need to train generations that can navigate and exploit these changes as they happen.

The JUNK project is a world building program that we are now teaching globally that originated in a collaboration between USC SCA and Austral University in Buenos Aires. It is not only reaching students in entertainment media but also in trades as wide reaching as engineering, biology, anthropology, architecture and social politics. It’s a true test of how what we are learning through the intersection of the advances in media and world building can change the world.

Finally, how would you characterize the twenty-first century production designer based on creative and technological developments in screen practice and the film industries?

Our work is to stay on our toes, be aware of every change in tools and resources, interface more deeply with the full breadth of production, and increasingly demand that the technology keeps up with our imagination.

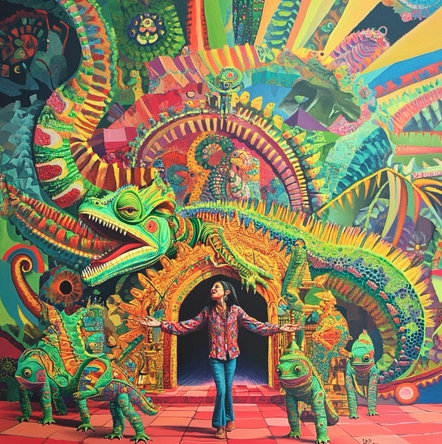

future world vision – mega city 2070 project

BiographiesAlex McDowell. Designer. Royal Designer for Industry (RDI). Creative director, production designer, professor, world builder. British citizen, US citizen, living in the US since 1986. He has been a production designer and creative director in film, game, animation, theatre and other media for over 30 years. McDowell is an advocate and originator of the narrative design system world building. His practice incorporates design and storytelling across media in education, research, institutions, corporations, and entertainment media. He is co-founder & creative director of Experimental Design, Professor of Cinematic Practice at the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts, Director of the USC World Building Institute & World Building Media Lab, USC William Cameron Menzies Endowed Chair in Production Design, founder of the the JUNK Consortium, Associate Professor at USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, The Bridge Institute. He’s written and talked a lot about narrative design, for a long time, in many places, to many people.

Tara Lomax is an Associate Editor at Pop Junctions. She has expertise in entertainment franchising, multiplatform storytelling, and contemporary Hollywood entertainment and has published on topics such as transmedia storytelling and world building, creative licensing, seriality, virtual production and visual effects. Her work can be found in publications that include JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies, Senses of Cinema and Quarterly Review of Film and Video, and the book collections The Screens of Virtual Production (2025), Starring Tom Cruise (2021), The Supervillain Reader (2020), The Superhero Symbol (2020), The Palgrave Handbook of Screen Production (2019), and Star Wars and the History of Transmedia Storytelling (2017). She is the Discipline Lead of Screen Studies at the Australian Film Television and Radio School (AFTRS) and has a PhD in screen studies from The University of Melbourne.

IPDW2025—Minding Dreams

As a teenager in the late 1960s, I enjoyed “turning on, tuning in and tripping out.” But I never in my wildest adolescent dreams could have foreseen the trip that “minding dreams” has taken me on. These dream journeys that I have experienced have been far more wondrous than I could have ever imagined when I was younger.

What have I discovered over this past 50+ years of “minding dreams?” What is it about each one of the dreams that has resonated with me? When you experience specific types of dream imagery over and over again... it’s almost like you’re finding your own water level of subconsciousness. My pursuits and interests as a young person were quite varied. From drawing and painting and writing and traveling and then philosophizing, continuously seeking transcendental experiences, even being on the receiving end of “messages,” which I thought were meaningful to me. I don’t mean weird otherworldly “messages,” I just mean listening to and being influenced by music, especially the songs of the Beatles; to the extent that I, like so many others of my generation, felt I actually understood where they were creatively coming from. I still do.

I marveled at the Beatles’ ability to form something that was so much greater than the sum of the individual parts in their music, and to express that so magnificently that the “message” was not only exhilarating, but overwhelmingly resonant when played and replayed again. And most importantly, that I could keep hearing those musical and lyrical “messages” playing in my head over all these years. I think that my being on the receiving end of that kind of a dream-like “messaging” in the late 1960s, especially from John Lennon, reinforced for me something that I felt I already intuited about the life of many Dream Minders.

After a Dream is first experienced, each person who “has it” often tries to recall who was in it and what happened…and then perhaps to understand what it was about. But afterwards, what the dreamers are often left with is the memory of images of not just who was in the dream and what occurred, but also where the dream took them, and how it made them feel to be there.

During this process of “minding dreams,” we often like to think we can justify the aesthetics from an “almost” rational perspective, but most of the time we simply respond to what feels intuitively plausible to us. Over the years, I have learned that there is almost always a way to perceive an ethereal creative dream web underlying each dream, so that we later can actually “mind” that area, as in later exploring it conceptually and emotionally. And perhaps even spiritually.

I’ve found that this level actually matters to many of the best dreams, which inspire us to find the mysterious aspects that are “there” to be discovered, which we might not at first have seen or realized were “there.” I’m personally usually looking to experience dream places that feel like they have already existed before I arrived there in my dream.

What does the process of “dream minding” look like? What does it feel like? What does this emotionally or even intellectually express? Where we go, we take others. And once we show where we are, it often becomes clear that this also fundamentally helps to determine “who we are.” And this, for me, is the essence of what “minding dreams” is all about. They reflect simultaneously both the sum of what was first experienced, and then subsequently what is shared with other dreamers who can now “mind” the same dream.

Through writing, music, film, painting, sculpture, in a digital or analogue medium, many dreamers attempt to express or re-create their dreams in order to see them “come true.” However, not many are successful at doing this. The fortunate Dream Minders, who truly create from the dreams that come to them naturally, usually have their inner eyes and ears attuned to their inner mind of dreaming much of the time.

One celebrated Dream Minder once said, “Some of my best dreams are not my own.” His interactions with others in the creative process of “minding dreams,” which have subsequently inspired so many, is located somewhere within the mind space between where he is and where others subsequently arrive mentally.

One of the things that most “Dream Minders” have in common with one another is a deep love of visual storytelling, combined with a great desire to inspire and be inspired by the dreams of others. Dream visions are not always something anyone can illustrate right away. Dream Minders can feel that they’re having a vision of a dream before they can fully “see” it. It’s not always an image that comes into view in their mind’s eyes, but almost more of the feelings of a presence in a dream that mysteriously demands engagement and exploration.

There’s always a gap between each one of us, because as individuals we each have our own individual consciousness. We usually feel original and uniquely alone while we are dreaming. But where do those images and sounds, and our responsive thoughts and feelings come from? Surely from somewhere…and, once we express them as dream visions, how are they actually received by other dreamers, particularly in a potentially collaborative process such as “minding dreams?”

The context of what you're “seeing” or trying to “see” in a dream makes such a big difference in how you perceive it, especially when you’re trying to transform it into something else in the process of “minding dreams.” Sometimes when I'm scouting in my mind’s eye, I have the feeling that actually I'm “auditioning” dream places, characters, ideas and feelings in order to see if they not only want to be in my dream, but can they be in my dream to fulfill a specific purpose.

That means a Dream Minder must have a filter that disregards what they are looking at in a naturalistic sense. We’re only “seeing” it for how it might potentially fit into that specific dream. Underneath this level are other considerations, such as, what is it for or what’s the reason for it to be in this dream? Most importantly, what is its spiritual purpose in the dream?

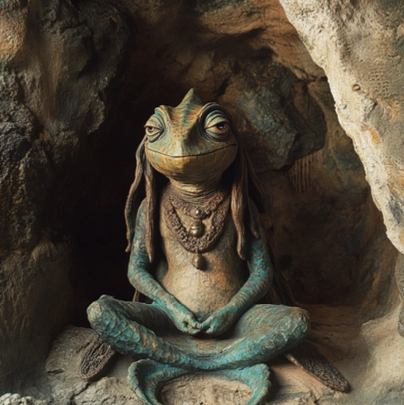

BiographyRick Carter is a production designer and art director best known for his work on films such as Back to the Future Part II (1989), Back to the Future Part III (1990), Jurassic Park (1993), Forrest Gump (1994), Avatar (2009), Lincoln (2012), Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015), and The Fabelmans (2022). He has collaborated with directors such as Steven Spielberg, Robert Zemeckis, James Cameron, and J. J. Abrams and is a two-time Academy Award winner.

October 22, 2025

IPDW2025—Storytelling Through Spaces: The Blood, Sweat, and Tears of Production Design

Having worked in the Art Department for the last twenty years, and as a production designer for ten of those years, across feature films, short films, commercials and television, I have come to believe that, put simply, production design is about creating worlds that are believable. Worlds where the audience is unable to tell real locations from created sets. I have very often overheard the line, meant as criticism, “what did the production designer even do here?!” But to me, this is the highest compliment the production design team can receive. It’s what we strive to do in our profession. The audience knows what they see is not real, yet if the world feels true, they can surrender to it. My job is to make that surrender possible.

To the outside world, the term “production design” conveys something glamorous and creative. But, in reality, this profession is a constant battle between creativity, logistics, deadlines and budgets. Even the weather and changing shoot schedules shape what we finally build. Every project turns into a balance between vision and adjustment. You start with a clear plan, but the plan never survives the ground reality. And so, you learn to adapt, all the while ensuring that the set never suffers.

John Lennon once said, “life is what happens when you’re busy making other plans”. But I’d tweak it a little to say, “production design is what happens when you’re busy making other plans”!

When I started in this field, the work began with hand-done sketches and physical models. Now, with the major technological advances available to us, we begin with screens: digital renders, previsualization and virtual production tools. These have changed how we plan and build, and they certainly help when you’re putting together large-scale productions. But personally, I still find that there is no match for the details one can bring to elements by hand, especially in a culture of resourceful ‘hacks’ like India. Technology is useful, but it’s not design. Real design happens when your hands are dirty, when you’re mixing colours on site and when you find a new tone under natural light. A render can show a space, and it can’t give it life.

Every film or series I’ve worked on has taught me something new about how the spaces a story is set in shapes how we feel about the story itself. I pick two of these projects as examples to shed light on my experience in this business across two decades: Gold (Dir. Reema Kagti, Excel Entertainment, 2018) and Dahaad (Dir. Reema Kagti, Amazon Prime Video, 2023). Both these productions could not be more different to each other: one is a period sports drama, set against the backdrop of pre- and post-independent India; the other is a thriller series set in present-day rural Rajasthan and in the context of the Indian caste system.

Though diametrically different in the brief I was given, my challenge on both projects was the same: to bring the screenplay to life visually, in such a seamless manner that the audience should feel like they’ve entered India in the 1940s or rural Rajasthan as it stands today, all while sitting in the comfort of their seats. A personal challenge I set myself, as I always do, was to create a space that would inspire the actors to perform, the cinematographer to shoot, and the director to direct, from the moment they walked onto set.

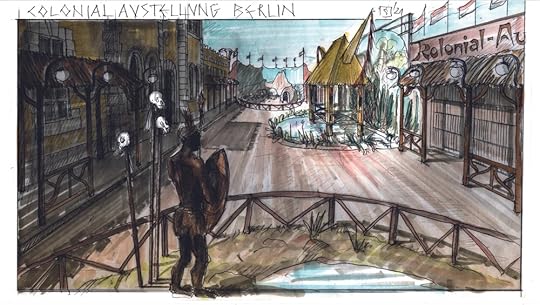

As production designer on Gold, I had to recreate a colonized country striving to find its identity back in the 1940s. The story of India winning its first Olympics gold medal in hockey after independence was not just about sport. It was about pride, self-belief, and reclaiming dignity. That feeling had to live in every frame—not just through dialogue, but through the world we built.

India has changed so much in the seven decades since its independence that few visual elements from that era still exist. While some places retain an old charm, modern life has seeped in everywhere — glass, steel, signboards, and cables. For this film, our challenge was to erase the present to find the past. Extensive research went into every element, from the props and set dressing, to the colonial Indian architecture, and the color palettes. We fabricated props and recreated objects like cameras and furniture from archival photographs we discovered. Some period elements were even sourced from London to capture the colonial influence visible in India during that time.

the finished hockey field.

making the hockey field

hockey stick props

Gold was an extremely labor-intensive film. An anecdote that comes to mind pertains to one of the key props in the film: the hockey sticks. We needed 350 of them, all wooden and appropriate to the period. After scanning my database, I found a vendor in Punjab whose grandfather had crafted hockey sticks for India’s Olympic team decades ago. We discussed every detail of these hockey sticks — the shape, the weight, the finish. Once the sticks arrived in Mumbai, my team and I refined each one by hand. We dyed the thread and grips ourselves, used toweling fabric to wrap them, and matched their texture to the old sticks used in the 1940s. By the end, these hockey sticks went from being mere props, to being an integral part of the story on screen and behind the scenes for the team of Gold. The actors too rehearsed their hockey games with these sticks for the shoot, to create authenticity on set and in their performances.

One of the largest structures we built for this film was a monastery and the area around it. Everything was built on one large piece of land: the mud hockey field, dining hall, kitchen, hostel rooms and so on. The monastery had to look timeless and completely free from any British architectural influence. It was designed as a Buddhist place of calm and focus, with simple geometry, earthy tones, and raw textures. The hockey field itself came with its own set of problems. The ground, which once used to be a paddy field, was soft from years of cultivation. We spent days draining it, layering it and stabilizing it before the players could train on it. It took us more than a month to build that entire world, and every day brought new challenges: structural, aesthetic, and emotional.

THE FINISHED MONASTERY (GOLD)

THE FINISHED MONASTERY (GOLD)

THE FINISHED MONASTERY (GOLD)

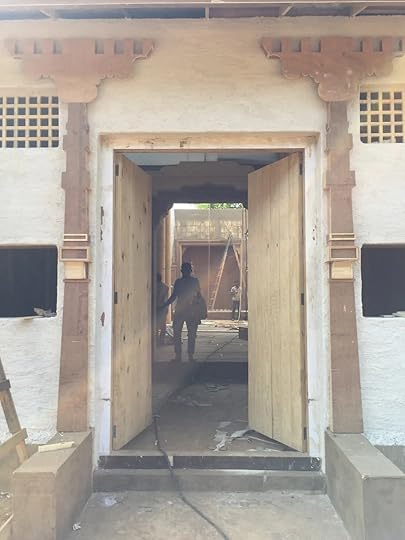

MAKING THE MONASTERY (GOLD)

MAKING THE MONASTERY (GOLD)

MAKING THE MONASTERY (GOLD)

We also had to build an entire market set outdoors for this film. It was beautiful on paper, but nature had other plans. For a week straight, thunderstorms hit every evening like clockwork. Each time it poured, the street became drenched, the paint washed off, and large parts of the wooden structures swelled or warped. The next morning, my team and I would start again: repainting, replacing damaged plywood, drying out props under whatever sunlight we got. Because the schedule couldn’t shift, we lost the chance to age the walls the way we had planned. The surfaces looked too fresh for the period we were recreating. That set was never quite what I wanted it to be. It’s hard to admit that, but it’s part of the truth of our work—some frames carry your pride, others carry your struggle. This experience taught me more about the limits of control than any technical challenge. You learn to adapt, to make the best of what remains after a storm, sometimes literally.

Another incident that comes to mind is how one afternoon, while the set was still being constructed, a violent thunderstorm hit. In the chaos that followed, one of our carpenters got struck by lightning. He was seriously injured and had to be hospitalized for months. That moment stays with me. It continues to remind me how much unseen risk goes into creating what appears effortless on screen. After this lightning incident, the mood on the Gold set changed completely. What could have torn the team apart brought us closer. Every member became more careful, more connected. This incident taught me an important life lesson which I carry to this day: production design is not just about visuals, but it’s about people—the carpenters, the painters, the set dressers, and the workers whose hands built a whole world from nothing. Every beam, every wall carried human effort. Every set is a record of hands that built, painted, and carried. These are the invisible architects of cinema. Their names appear briefly in the credits, but their presence lives in every frame. Film production is, and must always be, a culture of collaboration. Each person brings their craft, and everyone depends on each other to complete the film. The hierarchy may exist as hierarchies do, but what truly matters is trust and teamwork.

AT THE DESK (GOLD)

HOSTEL EXTERIOR (GOLD)

HOSTEL INTERIOR (GOLD)

CREATING THE HOSTEL (GOLD)

DINING AREA (GOLD)

MARKET AFTER RAIN (GOLD)

VILLAGE STREET (GOLD)

PROP FABRICATION (GOLD)

PROP FABRICATION (GOLD) Dahaad (2021)

Whether it’s a massive historical film or a contained streaming series, the foundation is the same: shared labor, patience, and a belief in the story we’re telling together. Dahaad wasn’t a grand period piece, but a grounded story about real people and the social constraints around them. The team was smaller than Gold and more intimate, but the effort was just as extensive. When I began work on this series, I wanted the setting to act like a character. This story lived in ordinary spaces — small towns, police stations, homes—but each of these spaces hid tension, and the quiet dread that something terrible might exist in familiar places. There was no scale or spectacle to hide behind on this project, which ultimately became our biggest creative and technical challenge.

During the location scout, we found an abandoned building that we finalized for the main police station set. It wasn’t ideal. The rooms were tiny, arranged around a large central courtyard, the corridors were narrow, and camera angles were difficult. But there was something that just clicked about the space. To turn that cramped building into a workable set became one of the biggest tests of our design skills. Because the rooms were small, every surface mattered: the color, the texture, and the light all had to come together seamlessly to create an atmospheric and visually appealing, yet realistic, police station set in rural India.

POLICE STATION INTERIOR (DAHAAD)

POLICE STATION EXTERIOR (DAHAAHD)

POLICE STATION COURTYARD (DAHAAD)

POLICE STATION CORRIDOR (DAHAAD)

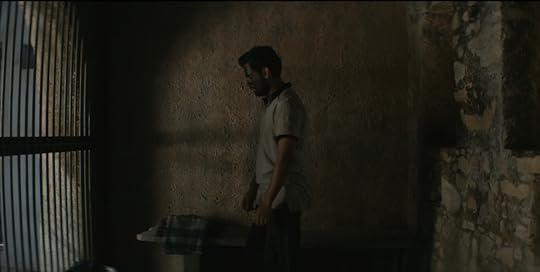

JAIL CELL (DAHAAD)

INTERROGATION ROOM (DAHAAD)

INTERROGATION ROOM (DAHAAD)

ANJALI CABIN (DAHAAD)

I decided to keep the look bare and stark. Too much set dressing would make the set feel false. The walls, the dust, the cracks were all created by hand, with minimal dependence on technology. Since regular paint on the walls looked too clean, we decided to use limewash to get a rough, uneven texture which caught light differently at every hour. That surface gave life to the frame: it looked like a real government building that had seen years of use.

The limited space also influenced how scenes were staged. The tension between the officers, the fatigue, and the moral unease of the investigation in the screenplay all lived within that confinement; it left the viewer feeling like the killer could be anywhere, maybe in the next room, maybe outside that very wall. That’s the thing with production design—it has the power to make or break a film.

Shooting Dahaad wasn’t easy. The heat and the dust of the crowded sets in Rajasthan tested everyone. But that discomfort became part of the story. The actors weren’t performing in comfort; they were surrounded by the same exhaustion their characters carried. Designing Dahaad taught me that realism isn’t just about accuracy. It’s about feeling the truth of a space. When a wall has history, it speaks without dialogue.

Some of my favorite memories from Dahaad are from smaller moments. We turned a 17-seater van into a moving library for children, filled with toys, bright colored books, and Hindi poetry on its sides. That set brought me pure joy because it carried lightness in a story filled with tension. At the other extreme were the public toilets featured in the cold openings of each episode. We built them in real public spaces, and they had to feel unsettling and dirty.

In streaming projects like Dahaad, the pressures are different—longer schedules, tighter budgets, and the need for consistency across episodes. The pace is slower, but the demands are constant. You’re always maintaining a visual rhythm while staying realistic. The constraint shifts from weather to time, but it still tests the same thing: patience.

VAN EXTERIOR (DAHAAD)

VAN INTERIOR (DAHAAD)

VAN EXTERIOR (DAHAAD)

PUBLIC TOILET (DAHAAD)

PUBLIC TOILET (DAHAAD)

__________________________

To summarize, production design is often described as background work. But for me, it’s where the story begins. It gives actors a world to inhabit and audiences a world to believe in. Production design is not just about how a space looks: it’s about how it feels. The walls, the surfaces, the props all carry the weight of the story visually, even before the characters speak.

This line of work continues to teach me so much more than just visual world building. Every day is a philosophy class and a therapy session that teaches me life skills. I learn about detachment because these worlds we build with our blood, sweat and tears are temporary—they get dismantled, repainted, or replaced. I learn about coping with disappointment when sometimes you build sets that never make it to the final cut—a scene gets rewritten or a sequence is edited out, and the entire set you built with so much effort quietly leaves the film. I also learn about going with the flow and about adapting to change and dealing with difficult scenarios (sometimes people!).

Your patience is tested, you’re pushed to limits you didn’t know you have, all the while learning new things about yourself. In production design, you learn to let go and build again. Every project becomes a lesson in resilience. You learn to let go of perfection, to trust your team, and to find the beauty in what survives. You learn to build worlds that disappear, yet somehow, continue to live on in emotion, forever immortalized on the celluloid.

I truly believe that you have to either be totally mad, or totally passionate to be in this profession. I think I’m a mix of both.

BiographyShailaja Sharma is a Mumbai-based production designer. She began her journey in Bollywood nearly two decades ago, starting out as an assistant and learning the craft on the job. Over the years, she has worked on films like Gold and Yeh Ballet, and on Dahaad—the first Indian series to premiere at Berlinale in 2023. She also completed a course in Production Design at the London Film School. In Japan she also studied the language and absorbed its design sensibilities, which continues to shape the way she sees detail, texture, and balance in every project.

October 21, 2025

IPDW2025—Natural Realism in Production Design Through the Lens of ‘Watching You’ (2025–)

When audiences think about production design, they often imagine the elegance of period pieces or futuristic science-fiction. But in contemporary drama, design succeeds by doing the opposite — disappearing. The goal is not to create spectacle but to persuade; to build spaces so truthful that viewers forget they were ever designed.

As Production Designer on the Stan Original series Watching You (2025 – ), this creative paradox was at the heart of the work: the more authentic a world appears, the less audiences notice it. Yet achieving that invisibility requires an extraordinary amount of visible labour — research, experimentation, collaboration, and sensitivity to story. The show has been described as “elevated Australian noir — sexy, stylish and suspenseful” (The Conversation, 2025). For me, it was an opportunity to explore how the language of natural realism can heighten psychological tension while staying grounded in emotional truth.

Watching You is a contemporary thriller built around the themes of surveillance, intimacy, and power. The story follows Lina, a paramedic whose one-night stand is secretly recorded, spiralling her life into paranoia and danger as she hunts for the voyeur while questioning everyone she trusts. From early script meetings, it was clear that voyeurism wasn’t just part of the plot — it was a design philosophy. Sydney’s oppressive summer became an agitator, a force that pushed our characters to the edge.

We embedded these themes into the visual language building it around reflection and concealment; exposing for harsh sunlight, embracing deep shadows combined with Hitcockian framing. Urban environments featured glass facades, open-plan layouts, and visible sightlines that could both reveal and obscure. We used fluted and mottled glass in key locations to distort visibility, blurring what's seen and unseen. In contrast, our rural setting — an old bush house belonging to Lina’s Grandfather — worn timber, aged metal, heavy drapery — was the opposite: concealment, protection, and memory. It provided refuge yet carried an unease through its isolation.

Location photo, pre art department work

Pa's House location with set dressing and painted throughout

This environmental contrast operates on multiple levels—urban versus rural, modern versus aged, transparent versus opaque—all reinforcing the story's themes without announcing themselves. Rather than dressing sets to look “pretty,” we designed environments that were sun-bleached, tactile, and alive with atmospheric heat, letting natural elements like fire and wind shape the emotional landscape.

Every character’s environment reflected their psychological arc. Lina’s home felt warm but constraining, echoing her move from security to vulnerability. Low ceilings and vertical blinds foreshadowed her eventual sense of entrapment. Clare and Axel’s aspirational home embodied femineity through curves and archways, its palatial scale contrasted with Lina and Cain’s modest townhouse, reinforcing themes of desire, duplicity, and power. Pa’s House became almost a character itself — a space layered with memory, decay, and transformation.

The way a person lives tells us everything: clutter versus order, material choice, colour temperature, or the wear on a chair arm. Cultural identity was also integral. Characters’ mixed backgrounds were represented subtly through heirlooms, design motifs, or pattern that reflected layered heritage without cliché. Similarly, their occupations as first responders informed practicality: furniture placement, accessible storage, lived-in functionality.

We personalised environments with small, authentic touches drawn from collaborative conversations. During pre-production, Aisha Dee, who plays Lina recalled a set of childhood toys she’d collected. We sourced those exact items and placed them in Pa’s House on the shelf beside a photograph of Lina’s Mother. They never needed to be referenced, or have a close-up, we dressed them into the set to support her performance and trigger an emotional connection to a real childhood memory for the scene.

Lina discovers the hidden camera concealed in a textured lamp base designed so the lens fit inside a single embossed bump. Stills: Lisa Tomasetti.

Pa’s House, set dressed with heavy drapes and curtains responding the themes of concealment.

Production design thrives on collaboration. My Design Bible — a visual compendium of mood, palette, materials, lighting and spatial reference — became a shared language for our second block director and cinematographer as well as the whole art department team. Design thinking often happens collectively and physically. For one major set build, we taped out dimensions on the office floor so the director and DOP could walk it and lens up on it, feeling proportions viscerally before construction. Practical limitations inevitably shaped creative choices. A dream location might collapse due to permissions or scheduling; budgets stretch only so far. But constraint breeds authenticity. When our ideal setting fell through, we adapted an industrial space instead — and it felt more truthful than the original concept.

Naturalistic design doesn’t mean neutral design. Every colour choice, material, and line carried meaning. Orange emerged as a key accent. Through the last-minute location change mentioned earlier, we were gifted a bright orange door — an unmissable visual warning. Vanessa Loh (Costume Designer) dressed Lina in an orange dress as she entered for the first time. That repetition of the orange dress against the orange door amplified the danger like a subliminal message: don’t go in. Orange became a warning associated with specific characters and props foreshadowing danger. These decisions aren’t decorative — they’re narrative.

Natural realism extends beyond walls and furniture. It lives in the brands, logos, and artefacts that populate the world. We designed fictional companies like NestShare and ForgeFit with the same care real branding demands. Hundreds of names, logos, and applications were tested until they felt authentic. These details, a phone App logo, a promotional LED screen video, may pass unnoticed, but they cement the believability of the universe.

Chai Hansen as Cain, looking down the lens and seen through playback screens against the ForgeFit backdrop. Stills Lisa Tomasetti.

ForgeFit Launch Party entrance dressed with branding and decadent flower arrangements. Vertical line and glass motifs reoccurring throughout the series.