Henry Jenkins's Blog, page 7

March 4, 2024

OSCAR WATCH 2024 — World on Fire: Reflections on 'Oppenheimer' (2023) and Contemporary Hollywood

This is the first of a series of critical responses to the films nominated for Best Picture at the 96th Academy Awards.

If ever there was a film of the moment, Oppenheimer must be it, right now. The film ends ominously with the image of the globe’s surface being consumed by (nuclear) fire (Figure 1), doing so at a time when the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists has set its Doomsday Clock, both in January 2023 and in January 2024, at 90 seconds to midnight, the closest to the end of our world it has ever come since the clock’s inception in 1947. With two nuclear powers (Russia and Israel) currently involved in large-scale wars and all the others (the UK, France, China, India, Pakistan and North Korea) involved in border disputes, limited military interventions and/or nuclear posturing, all of which could quite conceivably escalate at any moment, the ending of Oppenheimer is uniquely resonant. Many viewers, journalists and other commentators have reflected on these resonances, as have I.

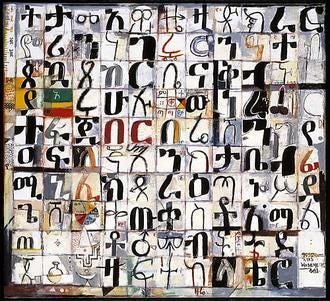

figure 1: world on fire in oppenheimer (2023)

But there are other things to consider as well. A critics and audience favourite (judging by its ratings on Rotten Tomatoes and Metacritic and its ranking in the IMDb users chart, as well as the numerous awards it has already won), Oppenheimer has been nominated for 13 Oscars; only three movies have ever received more. Members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences love biopics and, more generally, films more or less closely (or loosely) based on real events. Best Picture Oscar winners of this kind range historically all the way from Mutiny on the Bounty (1935), The Great Ziegfeld (1936) and The Life of Emile Zola (1937) to Spotlight (2015), Moonlight (2016), Green Book (2018) and Nomadland (2020). The academy also loves Christopher Nolan and his movies which have received dozens of nominations since 2002, including for Best Director, Screenplay and Picture; but despite eleven Oscars awarded for Nolan’s movies, so far there has been none in these last three categories. As a Nolan-written-and-directed biopic about J. Robert Oppenheimer, the so-called “father of the atomic bomb”, which meticulously reconstructs the events leading up to the first nuclear explosions at the Alamogordo Bombing Range and in Hiroshima as well as important post-war developments, Oppenheimer would seem to be tailor-made for this year’s awards ceremony.

And there is yet more to say about the timeliness of this film. A surprise hit at the box office (at number three in the global chart for 2023 with revenues of almost $1 billion, the second highest figure ever for an R-rated movie), Oppenheimer breaks with the dominance of franchise movies as well as free-standing fantasy/Science Fiction/superhero/action and animation movies at the top of the annual global box office charts. Together with the underperformance of some of the usual suspects for global box office glory and the surprisingly successful transfer of the Barbie and Super Mario Bros. phenomena to the big screen (making up numbers one and two in the chart for 2023), some commentators have taken the financial success of Oppenheimer to indicate a possible sea change in cinemagoing habits and preferences – although it is not at all clear in which direction this may go: newmovie franchises and/or a return to biopics and historical epics (the latter arguably the most successful genre at the box office until the 1960s with a major revival in its box office fortunes in the 1990s).

Before one can speculate about whether Oppenheimer might initiate certain trends, one needs to get a better understanding of what kind of film it actually is, and to do so means, among other things, acknowledging that it explores one of the key themes of global blockbusters since 1977, namely large, even global, communities under threat, with high levels of spectacular death and destruction being put on display. From the Death Star’s destruction of Alderaan to Thanos’s erasure of half of all life in the universe (with the added threat to perhaps wipe out all life so as to enable a new beginning), Hollywood has entertained the world most successfully for over four and a half decades with stories about wide-ranging devastation.

And Oppenheimer arguably does this as well, even going as far as using the kind of mythological framework that also underpins other hit movies from Star Wars and Superman (1978) via the Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings movies all the way to the Marvel Cinematic Universe. After all Oppenheimer’s opening caption reads: “Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to man. For this, he was chained to a rock and tortured for eternity.” As already mentioned, the film’s final image is of the Earth on fire; fire stolen from the gods (in Greek myth or in 20th century science and engineering) goes together with infernal punishment – in Oppenheimer’s case not primarily for the bringers of fire but for all of humanity.

The film also makes interesting (and controversial) use of Oppenheimer’s famous quotation from the Baghavad Gita: “Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” In the final scene, Oppenheimer reminds Albert Einstein of the scientists’ fear that the explosion of the atomic bomb “might start a chain reaction that would destroy the entire world”, and then concludes: “I believe we did.” The following image of the burning planet suggests that Oppenheimer (and his team) will indeed one day have to be regarded as destroyer(s) of a world.

It should also be noted that, like so many other blockbusters, Oppenheimer makes extensive use of otherworldly special effects imagery, which here is mainly to do with what appear to be the subatomic and cosmological realms. This imagery could be – just like the final image of the globe on fire – related to Oppenheimer’s imagination, but it feels, to me, quite separate, not anchored in anyone’s subjectivity but more like yet another framing device: the story and the story world are not only placed in a mythological frame (Prometheus, Baghavad Gita) but also on a scale in between the unimaginably small and the unimaginably large, the world of human experience revealed as only a very thin slice of physical reality.

At the same time, the film – quite unusually for a Hollywood blockbuster and even more so for one of the biggest ever IMAX releases – is for long stretches basically made up of talking heads (not necessarily in close-up, though). There is lot of dialogue and also some silent contemplation, but not much action; or perhaps one could say that the dialogue is the action. Now one might expect that this being a biopic, the dialogue reveals a lot about Oppenheimer, and in a sense it does: one gets a strong sense of his arrogance and his tendency to offend and alienate certain people, but also his ability to convince people, to win them over, to mobilise and guide them. It is strongly suggested that much of the time he merely plays a part, in that he carefully calculates what he says and how he generally presents himself to others with a view of manipulating them.

There are very few scenes revealing his “true” self, as it were, his genuine beliefs and feelings (his breakdown after he receives the news of Jean Tatlock’s death being one such scene). Importantly, the closest we may come to understanding him perhaps are comments made by his wife and by his nemesis, Lewis Strauss – and they do not paint a flattering portrait: Oppenheimer is said to be a narcissist who revels in having led the atomic bomb project and who, instead of feeling genuine regret or guilt, just wants to shift the public’s perception of him, if necessary by playing the role of a martyr in the security hearings. This gives an extra charge to his final (flashback) dialogue with Albert Einstein. What exactly are we to make of his facial expression and tone of voice when he says “I believe we did” (start a chain reaction that will destroy the entire world)? Does he feel guilt and regret, or perhaps a perverse sense of pride?

I have to admit that I have only seen the film twice, and I may well see it very differently when I will finally go through it scene by scene, shot by shot, conceivably even frame by frame. But I think the film will continue to fascinate and deeply engage me and many other viewers for many years to come. Unless, of course, – and this is a genuinely frightening but, unfortunately, not really that far-fetched thought – the film’s final image of the burning Earth becomes our reality, and we (or rather: those of us who survive) will have more important things to do than analysing and appreciating movies.

Peter Krämer is a Senior Research Fellow in Cinema & TV in the Leicester Media School at De Montfort University (Leicester, UK). He also is a Senior Fellow in the School of Art, Media and American Studies at the University of East Anglia (Norwich, UK) and a regular guest lecturer at several other universities in the UK, Germany and the Czech Republic. He is the author or editor of twelve academic books, including American Graffiti: George Lucas, the New Hollywood and the Baby Boom Generation (Routledge, 2023), and has published over ninety essays in academic journals and edited collections.

February 19, 2024

Immersive Ways of Live Storytelling Through Challenging Transmedia Universes: Rodrigo Terra Interviewed by Renata Frade and Bruno Valente Pimentel

Rodrigo Terra is an old-school transmedia evangelist who still maintains the systemic logic of developing storytelling projects with advanced immersion technologies for interactive content. His career is a great model of a hybrid researcher, with parallel academic and professional trajectories over more than 15 years of work in Brazil and abroad, especially related to virtual reality. Co-founder and Chief Technology Evangelist of ARVORE Immersive Experiences, Rodrigo Terra has won several international awards, including the first Primetime Emmy®️ in Brazil. He was awarded a Graduate in Administration degree from Fundação Getúlio Vargas (Brazil), trained as a radio broadcaster, and serves as a professor of Post-Graduation at ESPM-SP (Brazil). His mission today is to bring extended realities (XR) to the world and to raise Brazilian creative talents in XR globally. Today he is also a member of the EraTransmidia Association, Executive Director of the XRBR Association, and an active member of the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences (USA).

In my conversation with Terra and mobile apps developer and VFX editor Bruno Valente Pimentel, we discussed experiences developing transmedia and storytelling strategies as well as how those strategies can be applied to engaging audiences in entertainment, education, audiovisual media, and business.

Q - You have been working with virtual reality for almost 10 years in entertainment and education projects, in addition to being a transmedia researcher and founder of the Brazilian organization Era Transmídia, which has existed for around 15 years. Could you talk about why you became interested in this area of study and business? Throughout this period, what advances and areas for improvement do you see in terms of engagement and the evolution of media for transmedia?

A - My transmedia journey began in 2006 while studying at the New York Film Academy, where my focus was on flat screen content. I was always fascinated by how franchises like Star Wars, The Matrix, and The Lord of the Rings expanded their storyworlds across various media, showcasing different levels of integration and convergence. This curiosity intensified when I came across Henry Jenkins’ book Convergence Culture at a Barnes & Noble store. It was my first encounter with the term "Transmedia" and gave a name to my growing interest. At that time, there were no organizations or study groups on this topic in Brazil, leaving me to explore this field on my own. In 2011, I discovered the first study group on Transmedia at ESPM University in São Paulo. This discovery marked a turning point. EraTransmidia had just been established as an organization and, by 2014, evolved into an Association. I had the honor of serving as its President from 2016 to 2018. From the outset, I viewed transmedia as the future of content creation, extending beyond mere entertainment. Influential works by Professor Mark J.P. Wolf were pivotal in shaping my understanding of content as a journey through sub-creation. This approach sees storyworlds and galaxies of stories as systems akin to fractals, with both direct and indirect connections among the core pillars of narrative, playfulness, and interactivity. As of 2023, I observe that transmedia has finally become an integral part of the entertainment industry. The video game industry, in particular, now recognizes the value of transmedia, utilizing content creation strategies to enhance user engagement and expand intellectual properties (IPs) for that medium.

Several recent works demonstrate the effective use of transmedia:

- Sony Pictures and Sony PlayStation have adopted a new strategy for expanding their IP, highlighted by the creation of PlayStation Studios and Microsoft’s new IP conglomerate. A prime example is the Last of Us HBO series, which successfully extends the game's IP to reach a new audience while preserving the original game's fan base. This is part of a broader trend, with Sony Pictures also investing in adapting TV and movie series into innovative gaming and media formats, including XR. Conversely, Xbox is expanding beyond its long-standing Halo franchise, which has seen various unsuccessful attempts to engage new audiences over the past decade. The upcoming Fallout series on Amazon Prime, involving an open-world game, is another project to watch. It’s noteworthy that Todd Howard from Bethesda and Phil Spencer from Xbox are ensuring its canonical integration, a lesson learned from past transmedia efforts. Additionally, the growing popularity of board games and role-playing games that utilize these IPs adds another dimension to these storyworlds.

- The Line, a VR immersive narrative produced by ARVORE and directed by our partner Ricardo Laganaro in 2019/2020, is an Emmy Award-winning example of blending narrative with art forms to create something new. This project highlights how virtual reality can be used to weave compelling stories in an interactive and immersive environment and to evolve narratives by including the body as a meaningful medium.

- The creation of VR Chat worlds represents an emerging form of art and social interaction, originating from community-driven content. The works of creators like Fin Interactive showcase the potential of these platforms for community and user-generated content (UGC) to craft unique experiences. In these non-geographical spaces, users can engage with diverse avatars, including pop culture appropriations from Batman to anime characters, and participate in activities like watching new dramas through streaming services within VR Chat. This represents the cutting-edge of transmedia, where users can express themselves and interact in a virtual space that blends imagination with elements of popular culture.

Q - Your mission is to bring extended realities to the world and present creative Brazilian talents in XR internationally. How have you carried out this work and which are the most paradigmatic in terms of transmedia and storytelling actions?

A - I have always been an “evangelist” for ecosystems I’ve been connected to.

The transmedial approach, which I like to define as “the native and natural capability of an IP to expand throughout media and its degree of adaptability by trans-creation,” reaches one of its best values in the XR medium. When we add spatiality to the user’s perception of content, it unlocks another layer of the power of presence.

Q - You are a member of the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences (USA), President of ABRAGAMES, Executive Director of the XRBR Association, and winner of several awards, including the first Primetime Emmy®️ in Brazil. Could you talk about the journey you took to reach these achievements? What were the projects, training, mistakes and successes that made you achieve these things? How do you believe you are seen as a Brazilian, especially in the USA, in international projects and what are they currently?

A - I have always been committed to building and participating in communities I believe in. I am also an advocate for associative movements, believing in the power of people and companies coming together to seek a common betterment. I have always been an entrepreneur as well.

Q - You consider yourself a Legomaniac. How do you believe Lego can help in teaching and producing transmedia and civic imagination content and strategies? Do you have any experience in this regard?

A - LEGO is a therapy and an art form for me.

They have the incredible premise of “thinking with hands,” which helps connect our most profound learning capabilities with context understanding and complex conceptualization, everything using fun as a tool.

Through build-and-play, you need to imagine or follow initial instructions in order to start, which is essential to develop creation skills and materialize concepts. Concepts became tangible and you have a more personal and clear view of a difficult problem, for example.

LEGO Education Serious Play deserves mention because the company understood the power of fun and creation and developed a tool for stimulating problem-solving approaches by using Imagination to “get you out of the box.” This is a very native transmedia strategy.

Q - How do you see a VR/AR platform nowadays as a narrative experience tool? What are the best new platforms or technologies to develop a new immersive transmedia platform?

A - Today's immersive technology platforms empower creators and users to tell their own stories as personal journeys. This is the layer of “storyliving,” which goes beyond storytelling. A well-crafted immersive narrative experience puts you viscerally into fictional situations, as our brain understands that we are present in that space-time with more stimuli than just imagination. The memory created in that moment is more akin to a memory of a trip to a place where you were enchanted by a sunset on a rainy evening or a childhood moment playing with your favorite LEGO, rather than chronologically remembering a story you passively watched in a dark room or at home. There is no value judgment here, but immersive narratives are highly connected to the way we live moments, not just how we transmit our stories. Thus, I see that the best immersive transmedia platforms in the future will be those where you choose your degree of immersion, personalization, and socialization.

Q - How do you feel about Apple entering into the VR headset market with Vision Pro as an immersive tool? What kind of new experience you can imagine on it that you cannot have in hardware like the Meta Quest Pro?

A - Apple's proposal is indeed to have a spatial computer with enough processing power to elevate the paradigm of productivity and media consumption. We will still discover what we can do with this equipment, but an interesting thing, for example, is the potential metaphors we can create using the reality dial, where you control the degree of immersion you want to have at the moment. It's very playful and highly functional.

Q - You got a degree in radio and have a long history as a broadcaster developing projects in different platforms. Audiovisual is now becoming a convergence zone for games, AR/VR and XR projects. How do you perceive the power of storytelling and audiovisual foundations to involve the audience in those platforms?

A - I have always believed that stories should be expanded beyond screens. Great creators like Disney or Maurício de Souza have shown us this. Platforms that encompass media convergence as their semantic space need the foundations of the audiovisual to build new ways of living and telling stories. Just because we are in a new moment where interactivity opens paths for deeper connections with content, it doesn't mean the basics of story transmission no longer apply. Structures that the arts of theater, music, cinema, and television have taught us so far to inform, enchant, and provoke continue on. They are our common ground now.

Q - As a transmedia producer/researcher how do you perceive the evolution of immersive platforms, and which do you think is the best start for an immersive project nowadays ?

A - Today, to start a project, you begin with the motivation of what experience you want to offer someone. Beyond a story, the message you want to convey will be given viscerally in an immersive experience. Whether it will be a game or immersive narrative is a subsequent creation exercise, in my view. We always start with sensations, and from them, the product is born.

Q - What motivates the recent record in Brazilian game exports? Can you tell us about the Brazil Games initiative and how storytelling is applied in this campaign?

A - Brazil has improved its game production quality in all aspects – art, game design, sound design, and, mainly, universalism, over the last 10 years. The work of the Brazil Games export program (a partnership between ABRAGAMES and ApexBrasil) has been and continues to be to introduce these games, professionals, and companies to the world, so the international market can know, negotiate, buy, and distribute our content. Our narrative is very much focused on the journey of the studios, developers, and their games. We are still in a moment of discovering the capabilities of the Brazilian market in producing games that meet the desires of the modern consumer, but we are proving that the country is a creative powerhouse capable of being one of the largest game producers in the world in a few years.

Q - Metaverse is seen as an evolution of game world creation in which technology tools are used to live in other realities, other than just this physical one as we know it. There are many stories in Metaverse and different immersive experiences on it depending on the brand/technology you are using. How do you perceive it, and do you think in the future a possible convergence to create one universe/metaverse where many brand’s projects interact would be possible?

A - I believe the Metaverse is the natural evolution of convergent media. Understanding that we will increasingly enter the era of spatial computing, the media and content we consume and the forms of interaction with them and social interactions will also converge. Adding an important element in this equation: the physical world interacting in real-time with simulations, seeking to bring a new type of context perception called “mixed reality.” What we have to be careful of at this moment is to ensure that we have a solid construction of platforms that will converge in the future to be the Metaverse: integrated, open, and focused on protecting the privacy and security/integrity of those who will have this medium as part of our lives, just as we have smartphones today.

Q - Pixel Ripped is a great success for game sagas developed in Brazil! Would you tell us how the idea of the first game happened and what we can expect for the next games?

A - Pixel Ripped was born from the brilliant mind of our partner Ana Ribeiro and her motivation to tell, in the form of a game, about her child and teenage memories and daydreams about her own journey with video games. Pixel Rippedis a great tribute to the history of games, and more than that, it is a tribute to the memories lived by gamers of all ages. We can expect more games from the franchise addressing important and historic decades of video games, always with the franchise's signature of bringing the craziness of our imagination in when we are playing!

I have always been engaged in building and participating in the communities I believe in. I am also an advocate for associations, believing in the power of people and companies coming together to seek a common betterment. I have always been an entrepreneur as well. ARVORE Immersive Experiences is my second company; before that, I had a small production company focused on entertainment and events/corporate videos.

In 2017, already familiar with many VR and AR trailblazers, when we founded ARVORE, I felt the need, along with other innovators, to create a space for us to exchange experiences broadly. We joined forces in São Paulo with a group working on VR in Rio de Janeiro and started what became the XRBR Association (Extended Reality Brazilian Hub). From then on, our efforts to engage entrepreneurs from all over Brazil culminated in us becoming the largest association in the sector in Latin America by 2023.

With our work and ARVORE's engagement in the gamedev community, I was invited to lead ABRAGAMES (National Association of Videogame Developers). As of 2023, I have been in management for three years and will continue for two more. As a broadcaster, my dream was to someday come close to an Emmy statuette and perhaps see my name in the credits of a winning production. I never imagined being the executive producer of a Primetime Emmy-winning piece, especially with a prize I am most proud of like Outstanding Innovation in Interactive Programming. This recognition is a huge milestone in my journey, making me a member of ATAS and allowing me to contribute to the US content innovation ecosystem.

Being perceived and recognized as a Brazilian is the greatest achievement I seek. The quality of Brazilian digital products is unquestionable. Our diversity and originality are our trademarks; we communicate with the contemporary global audience. Living in imperfect systems has made us more adept at handling moments of crisis or difficulty. I only see advantages in being Brazilian and being able to contribute this worldview to the US and other territories.

BiographiesRenata Frade is a tech feminism PhD candidate at the Universidade de Aveiro (DigiMedia/DeCa). Cátedra Oscar Sala/ Instituto de Estudos Avançados/Universidade de São Paulo Artificial Intelligence researcher. Journalist (B.A. in Social Communication from PUC-Rio University) and M.A. in Literature from UERJ. Henry Jenkins´ transmedia alumni and attendee at M.I.T., Rede Globo TV and Nave school events/courses. Speaker, activist, community manager, professor and content producer on women in tech, diversity, inclusion and transmedia since 2010 (such as Gartner international symposium, Girls in Tech Brazil, Mídia Ninja, Digitalks, MobileTime etc). Published in 13 academic and fiction books (poetry and short stories). Renata Frade is interested in Literature, Activism, Feminism, Civic Imagination, Technology, Digital Humanities, Ciberculture, HCI

Rodrigo Terra is the Co-founder and Chief Technology Evangelist of ARVORE Immersive Experiences. He has won several international awards, including the first Primetime Emmy in Brazil. He earned a Graduate degree in Administration from Fundação Getúlio Vargas (Brazil), trained as a radio broadcaster, and is a professor of Post-Graduation at ESPM-SP (Brazil).

Bruno Valente Pimentel earned a Bachelor's degree in Social Communication and graduated in Radio and TV (Multimedia) at the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ/Brazil), with post-graduate work in Film & Television Business at Fundação Getúlio Vargas (Brazil). Bruno Valente Pimentel has been working with Audiovisual Products for more than 20 years. He was in the team who produced the first live streaming project in Brazil,Gilberto Gil/IBM ’s project “Pela Internet." He has also been a mobile app developer since the beginning of the App Store, creating apps in areas such as market, AR/VR/XR, events, services, brands, educational, training, streaming and entertainment. He also has experience in UI/UX and design and transmedia (M.I.T.).

January 29, 2024

Serial Killers and the Production of the Uncanny in Digital Participatory Culture

With the evolution of media from the late 19th century onwards the ‘spectacle’ of serial killing moved beyond the realm of one-to-many, lean back and read-only media to be incorporated across our many-to-many, lean forward read-and-write 21st century digital environment. The new media landscape – where we do not live with, but in media - is not merely a state of having more media. Rather, it reflects (as much as it invites) a radically altered experience of being in the world, one that is at once collective and collaborative, inevitably shared and participatory (whether through surrendering our personal information or via our co-creative behaviours online), as the Pop Junctions blog consistently documents.

The marriage of participatory culture and the digital environment extends to all mediated phenomena – from the hybrid warfare of the ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East, to the various ways people find, maintain and break up their love online, up to and including cocreating and reshaping the modern mythos of the serial killer. Further, the serial killer, we argue, is not just yet another exemplar of contemporary digital culture—it is reappropriated as a unique totem upon which people can project their anxieties about either a real or perceived dehumanisation process experienced in the digital environment. This experience is part of our recurring encounters in the digital environment suffused with reminders of humanity’s potential obsolescence. Examples of such uncanny occurrences include when we are confronted with algorithmic curation, automation and robotics, and the results of generative artificial intelligence (such as intimate chatbots and hallucinating image and video generators).

Our argument is based on a consideration of the specific ways in which users can be seen as active agents in the process of co-creative meaning-making about serial killers online, and how such engagement links to the uncanny as both an expression and production of people’s lives lived in digital media.

In our digital environment, the generation and co-creation of serial killer mythology takes places through overlapping practices. These include:

streaming and binge-bonding over content (such as serial killer documentaries or podcasts on the major platforms);

sharing content (trading serial killer media across multiple channels);

commenting about serial killers (which fuels massive threads on YouTube and is the raison d’etre of Reddit subs like r/serialkillers);

creating amateur content (which is particular to platforms like YouTube and TikTok); as well as

remediating or remixing content into memes and other forms of creative expression online, such as shared through the DeviantArt community.

These practices all function to encourage the appropriation and reappropriation of modern serial killer discourses into a new media language particular to digital culture.

While many theorists expounded on what serial killing says about the social in any given context and the ways in which serial killing and media entangle, we ask: what is the current new media landscape doing to the idea of the serial killer as it is related to media publics? And how is serial killer mythology developing in relation to participatory culture? What we suggest is that people’s lives in media open up ways in which media publics consume, cultivate and perform knowledge about serial killers, enabling them to exercise a reconfigured sense of control over the story of the serial killer as a myth and as a deviant Other, all serving to establish oneself as authentically human confronted with a pervasive and ubiquitous digital environment heavily populated by non-human actors.

Serial killers then and now

While the ‘serial killer’ was defined and coined in the 1970s, the phenomenon took hold after the Ripper murders of the 1880s in London’s Whitechapel district. The serial killer evolved through different media iterations—from a celebrity of the newspaper tabloid to the spectacle of the television, to a ‘public property’ of the new media apparatus. The high-profile case of Jack the Ripper was perhaps the first ‘celebrity’ serial killer, as he was celebritised via the medium of the newspaper. Another example of this relationship, this time in turn of the century Australia, is the case of Martha Rendell in Western Australia. Despite major protestations of her innocence and the dubious evidentiary support presented at court in 1909, Martha Rendell was the last woman to be hanged in Perth. The newspaper coverage at the same carefully constructed her, managing the threat of the ‘wicked stepmother’ serial killer.

Charles Manson, we might then say, was to television what Jack the Ripper and Martha Rendell were to newspapers—Manson exploded into public consciousness within the historical moment of the rise of colour television across America, and concomitantly, with the media obsession with celebrity. These figures are therefore not just a product of context, but also a product of media.

How we see them, how we project our fears and anxieties onto them and their horrific acts, how we make sense of the serial killers in our midst – this is very much a function of both mediation (how we learn about serial killers in media) and mediatization (how media come to play a profound role in the way institutions and society as a whole function over time).

Importantly, the newspaper, radio and later on television were the original mass media, symptoms as well as signposts of massive urbanization, the rise of the industrial age, and the emergence of the ‘mass’ society – where the uncannily anonymous nature of everyday life contrasted as well as aligned with the horrific acts and identity (as also one of us, just ostensibly less human) of the serial killer.

With the shift from the static imagery of the newspaper to the spectacularised moving image serial killers were reborn in living colour. As a result, during the post-War period, the function of the serial killer construct evolved and became, more than ever before, a function of media spectacle. The strategies of television formats developed in this era find eery parallels to the techniques of serial killer ritual, as Mark Seltzer writes, “Repetitive, compulsive, serial violence... does not exist without this radical entanglement between forms of eroticized violence and mass technologies of registration, identification, and reduplication, forms of copycatting and simulation” (1998: 265).

Since at least the late 1960s, with the ubiquity of colour television across the domestic sphere, media primed mainstream culture for the popularity, fascination, and endless imagery of the serial killer (Stratton 1994: 7). The site of the serial killer became a locus onto which media publics could project their own pathology, and emergent languages about perversion and trauma came to the fore. As such, the ‘serial killer’ reminded people of their corporeality as well as confronting them with its dismissal at the hands of these murderers. The visceral engagement between publics and celebrities that was fostered during this era intensified this relationship.

Television provided the necessary grounds for the production of violence as celebrity spectacle. A screen cultures evolved and professionalized, a pathological repetition of the subject of serial killing in the form of television news, true crime documentaries, and ‘serial crime drama’ ensued. As Brian Jarvis pinpoints in his work “Monsters Inc.: Serial killers and consumer culture,” a serial killer consumer culture emerged where ‘fans’ “avidly build collections which mirror the serial killer’s own modus operandiof collecting fetish objects” (2007: 27). We agree with Jarvis that it would be too simple to “dismiss this phenomenon as the sick hobby of a deviant minority” and rather understand it as “merely the hardcore version of a mainstream obsession with the serial killer” (327) engendered by and in media.

The serial killer of the 1960s onward, as represented (and promoted) in mass media culture, can also be seen as exemplary of this era’s relative affluent and peaceful nature and the rise of consumer culture, as the middle-class flocked to generic, lifeless suburbs and shopping malls of major metropolitan cities around the world.

The ‘serial killer’ construct continued to gain currency later in the 20th century as a manifestation, or even of ‘symptom,’ of postmodern media culture itself. In effect, labelling serial killing and serialising it on television and film also brought it, like murder back into the home—where it belongs (as Alfred Hitchcock was famously quoted in an interview with the National Observer of 15 August 1966).

The mythologising of the serial killer through postmodern media, in many ways, led to the conflation of the mythic with the abject, the grotesque with the sensational, and the tragic with the iconic. This is also what led to the glorification and even glamorising of serial killers that some commentators have condemned (“Netflix’s Next ‘Sexy Serial Killer’ Documentary,” 2019). Regardless of problematic ethical implications, late century broadcast models set the tone and conditions for the mediatisation of the serial killer on the new media platforms and practices of the 21st century.

Being human in the digital

Given the participatory nature of our digital environment, we recognise how users are active agents in the process of meaning-making about serial killers. The newly interactive style of public commentary exercises a kind of ‘public ownership’ over the ‘social problem’ of serial killing in ways that traditional media did not and could not. Commenting on serial killers fuels massive threads on nearly every social platform, the most notable of which are perhaps YouTube and Reddit, where one can witness raw and unfiltered exchanges. Partly, this phenomenon stems from the near-zero gatekeeping mechanisms on new media platforms. Users can also participate in these threads as anonymously (or as visibly) as they wish, a choice that provides another dimension of control over the practice.

Understanding why and how YouTube extends users’ agency in the process of meaning-making is complex and challenging. In part because of its originally open nature, and the ability to share and embed YouTube videos on every other platform or messaging service seamlessly and effortlessly, YouTube has become an incredibly powerful and impactful social phenomenon. In other words: YouTube is a ‘media public’ especially because it is a loosely knit co-creative practice.

Source: screenshot of YouTube

The top three results sorted by ‘view count’ for the search term ‘serial killer documentary’ on the YouTube platform (at the time of writing): “Inside the Mind of Jeffrey Dahmer: Serial Killer’s Chilling Jailhouse Interview” (Inside Edition, 2019) and “Ghosts of Highway 20”[1] (The Oregonian, 2019), boasting more than 37 million views each. The Dahmer interview video alone hosts more than 70,000 discrete user comments. When sorted by ‘popularity’ (ranked by ‘likes’), the top three comments on this video (on 27 March, 2023) are as follows:

The fact that he is so aware and still did it is absolutely terrifying. (51k likes)It’s terrifying how calm and normal serial killers seem, you just never know. (7.5k likes)This interview is literally insane. The way he’s able to recognize the bizarreness with such clarity but at the same time almost be completely detached from the carnal side of himself. Very strange man, it’s like he’s split in two mentally. (3.2k likes)Each of these top comments separately and distinctly engender a notion of the uncanny: the unsettling feeling that the once well-known, familiar, and reliable fabric of reality—whether another person, specific social relations, or people’s sense of belonging to a community—becomes strange and unsettling. As both Sigmund Freud and Martin Heidegger have argued in different ways in their published works, the first focusing on the uncanny as a feeling, the second on its relation to ontology, the experience of uncanniness goes to the heart of the human condition.

In fact, much of people’s actions and behaviour in life revolve around reducing, downplaying or altogether ignoring the uncanny, yet it is always there. The uncanny is waiting to be discovered, acting as a source of estrangement that makes us instantly aware of the fact that who we (think we) are, how things (are supposed to) function, and what all of this means is simply just an act of sensemaking that is essentially arbitrary, and permanently unstable. It is here that we meet the figure of the serial killer, as the comments above demonstrate, this is the place where the human figure is both monstrous and “calm and normal,” the place where the human figure is “split in two” (the other half clearly comprising a non-human, unfeeling and therefore unknowable entity). Here, people are forcibly moved beyond the horrors of their actions to the rather unsettling notion that these human beings can do what they do as part of our human community, part of us.

Users are active agents in the process of meaning-making about serial killers in relation to the uncanny specifically when looking at the kinds of gatekeeping operations that are active in Reddit’s true crime communities (r/TrueCrime and r/SerialKillers). Take for example the ‘patrolling of borders’ about what can be said, could be said, and what can absolutely not be said (with the consequence of being permanently banned). Three of the nine rules for participating in the r/SerialKillers community are specifically directed to these language rules:

#3. No glorification of serial killers#5. No Self-promotion / Merchandise Links / Murderabilia#9. No Writing To Serial Killers. (https://www.reddit.com/r/serialkillers/)These rules are self-regulatory and independent of traditional ‘rulemaking’ structures (in the sense that there is no legal obligation), reflecting the way the community sees its position in shaping the language and knowledge around serial killers—namely what is right, what is wrong, and how users should or should not engage with the cultural site of the serial killer. That is, the ‘serial killer’ must remain actively conscripted to its place as deviant Other—the celebration of which is not tolerated.

These structures can also be read as a mechanism of protection against the psychic threat of violence upon the community. This is activated both through the attempt to collectively ‘figure out’ the serial killer as a problem to be solved. For example, users provoke conversations on this issue by posting questions such as:

What are some of the wildest conspiracy theories for why SKs killed people? (https://redd.it/1257iun)Why is it commonly believed that a serial killer doesn’t stop killing until they die or are imprisoned? (https://redd.it/xwne4h)Why serial killers don’t kill bad people instead? (https://redd.it/vjr903)Of course, users could consider referencing or reading the medico-scientific literature on the bio-psycho-social makeup of these kinds of offenders to discern motivations, but there is a preference (and easier access point, especially considering most people do not have access to journals outside the field or the academy) to do this in an online community as it provides the power of collaborative knowledge-seeking and knowledge-making with the additional psycho-social safety of group dynamics and collectively policed boundaries.

Further, these relatively organic and self-directed rules suggest a broader attempt to distance the Self from the deviant Other. In her research on Reddit, Judith Fathalla (2022) points out that the term “‘True Crime Community’ (TCC) is a self-description used by enthusiasts of true crime media on Tumblr, Reddit and social media sites. Fathalla suggests that the very fact that these media publics self-describe as ‘a community’ is telling because it denotes a need for “boundaries and norms of behaviour” (3). This is borne out in rules and community discussions about ways of speaking. For instance, the r/serialkillers community reminds its members that “phrases like ‘favourite’ killer can be construed as glorification and are better phrased as ‘most frequently discussed’” (https://redd.it/gctnjx). These collectively policed ordinances enable anyone to delve deeply into the phenomenon, while such mechanisms of digital culture simultaneourly keep the threat of the serial killer at bay.

The Internet produces just as many unregulated spaces that cultivate taboo as it does self-regulated ones that attempt to contain it. In these spaces we see the uncanny emerge in other ways, namely, via the production of user-generated, and remixed material. An endlessly creative range of work is posted on the site DeviantArt, a user-generated portal self-described as a place where “art and community thrive” and through which users can “explore over 350 million pieces of art while connecting to fellow artists and art enthusiasts” (https://www.deviantart.com/).

By its very name, this community positions itself as the deviant Other. Members are referred to as ‘deviants’ and pieces submitted to the site are called ‘deviations’. It is unsurprising then that users remix serial killer iconography in ways that focus on some of the most troubling aspects of their crimes. Two pertinent examples are Jeffrey Dahmer’s cannibalism and John Wayne Gacy’s clown costume. In the case of Dahmer-themed content or ‘deviations,’ the notions of cannibalism and ‘ordinariness’ collide in a morbid excursion into the uncanny: cartoons of Dahmer ‘cooking’ with a frypan while skulls emanate from the pan (Star90skid), artwork remixing Dahmer in a scene together with American 1920s era serial killer Hamilton Howard “Albert” Fish casually discussing dinner (AGwun 2015a), and disturbingly ‘cute’ depictions of a child-like Dahmer with a knife and fork exclaiming “yummy” (AGwun 2015b). The range of John Wayne Gacy amateur work hosted on DeviantArt illustrates a preoccupation with assemblage and transformation that uses the evil clown as a leitmotif. There are literally dozens of remediations all conflating Gacy’s role in the community as ‘Pogo the Clown’ and the horror of his crimes.

https://www.deviantart.com/kazekage-of-the-sand/art/The-Bay-Harbour-Butcher-269494098

The incongruity provoked by the ‘ordinary cannibal’ trope cuts to the heart of the experience of uncanniness: all of them are just like us, and yet they are not – and one of the few ways we have to handle this, is to participate in remixing and deconstructing them. What these remixes on the tip of the digital serial killer iceberg remind us of is that rather than the ordinary being the opposite of our horror, the ordinary is in fact its twin, that is, the banal and mundane operate in dialogue with the deviant drive as a fortification against these taboos. DeviantArt functions as a site (both a cultural site and a web site) that holds space for the uncanny in this way. The ‘realities’ about us that we take as ‘given’ are disturbed and un-realised, made real again. In participating with this digital media, we are both normal (products of our environment) and not-normal (enjoying our taboo par excellence).

The serial killer belongs to all of usOf salience in our collective reworking of trauma, through the historically conjunctive development of mass media and social order, is the spectre of the serial killer—ostensibly human and non-human. In every era, the serial killer gets reinvented, in each step engaging more of us in its co-creation. Statistically, most people will never interact with a serial killer ‘face-to-face’. Our entire relationship with this character is therefore mediated through all the communication practices which bring this archetype into our knowledge, which is the very basis of discursivity. The serial killer, time and time again, proves to be an enigmatic figure, particularly produced by the mass media of its time, available us to act out and cope with our anxieties about what it is to be human, yet also reproducing us as inhuman cogs of the machine of mass society, industry, and culture.

In doing so, our media act on two levels, at once offering us human agency and effectively reducing it to (almost) zero. First, mass media operate as a way for the collective to regain some psychic protection from the threat of horror posed by the ‘serial killer’ as a social phantasm, not in the least because it is the ‘average person’ that is the typical victim of the serial killer. However, if we are all potential victims of serial killer attack, then through social practice we are all also potential guardians against it, as much as we are participants (in and through media) of making the serial killer.

In our analysis, we combine notions of serial killing through mediation and through understanding media as practice to explore the entanglement between the media public, the media apparatus, and the serial killer archetype, in a current interaction becoming re-articulated through digital modes of exchange that provide grounds to share, remix, watch, like and comment simultaneously, in the most voyeuristic and compulsive of ways. These new practices tend to reconfigure the role of the serial killer as a site of shared, complex and profound interactions with our bodies, the notion of bodies-in-pieces, and indeed our humanity and non-humanity all at once.

The mediation and mediatisation of the serial killer provides a historically embedded trajectory through which we can appreciate, as much as appropriate, our engagement with this abominable figure and the horrific acts they engage in. In short, we suggest that the serial killer today has become the totem with which we work through the fear of losing our humanity—and vitally doing so in a digital environment where the serial killer has come to belong to all of us.

Works CitedAGwun (2015a) Quarrel. https://www.deviantart.com/agwun/art/...

AGwun (2015b) Serial killers doodle 3. https://www.deviantart.com/agwun/art/...

Fathallah, J. (2022). ‘Being a fangirl of a serial killer is not ok’: Gatekeeping Reddit’s True Crime Community. New Media & Society, OnlineFirst: 1-20.

Freud S (2003 [1919]) The Uncanny. Translated by D Mclintock. London: Penguin.

Glitsos L and Taylor J (2022) The Claremont serial killer and the production of class-based suburbia in serial killer mythology. Continuum 36(4): 508–527.

Goodall M (2012) The ‘book of Manson’: Raymond Pettibon and the killing of America. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics3(2): 159–170.

Haebich A (1998) Murdering stepmothers: the trial and execution of Martha Rendell. Journal of Australian Studies 22(59): 66–81.

Jarvis B (2007) Monsters inc.: Serial killers and consumer culture. Crime, Media, Culture 3(3): 326–344.

Seltzer M (2013) Serial killers: Death and life in America’s wound culture. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

Star90skid (2018) In the kitchen. https://www.deviantart.com/star90skid....

The Late Show with Stephen Colbert (2019) Netflix's Next ‘Sexy Serial Killer’ Documentary. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7eMw4... (accessed 4 June 2023).

[1] Comments for the “Ghosts” documentary have been disabled—this can be enacted by the creator, which often happens when users become too involved, over-invested, or inappropriate or can be enacted by YouTube administration if the content/comments are of a sensitive nature and directed toward minors.

BiographyMark Deuze is a professor of Journalism and Media Culture at the University of Amsterdam (before that at Indiana University). He is author of 11 books, including McQuail's Media and Mass Communicatin Theory (Sage, 2020), Leven in Media(Amsterdam University Press, 2017), Media Life (Polity Press, 2012) and Media Work (Polity Press, 2007).

January 15, 2024

Feeding the Civic Imagination (Part Four): Passing Down and Following Up: Jewish Cuisine’s Umbrella Potential

Forward

COVID-19 lockdowns inspired the Civic Paths research group to explore how food is involved in civic imagination, the capacity to imagine alternatives to current cultural, social, political, or economic conditions. Although physically isolated, we found ourselves connecting over food—making it, eating it, missing it, and dreaming about it. These everyday experiences allowed us to share, learn, and think of what could be: they fed our civic imagination. By organizing the Forum “Feeding the Civic Imagination” on Lateral, the journal of the Cultural Studies Association, we invited others to participate in our exploration of food and civic imagination. Scheduled to be released in early 2024, the Forum brings together both topically and structurally diverse contributions to spark imaginations around various food-related practices, from traditional research articles on collectives around ingredients, cooking, eating, and human waste to practice-focused pieces on anti-racist pedagogy and Mexican and Palestinian recipe exchanges. To celebrate and extend the “Feeding the Civic Imagination” journey, three-part dialogues, “Intercultural Food” (by Elaine Almeida and Lisa Silvestri), “Digital Media and Food” (by Brienna Fleming and Ioana Mischie), and “The Great British Bake Off” (by Lauren Levitt and Elaine Venter), were organized for Pop Junctions. Jana Stöxen’s article, “Passing Down and Following Up: Jewish Cuisine’s Umbrella Potential” is the fourth and final installment of Pop Junctions’ series on Feeding the Civic Imagination. Jana’s case study is a thought-provoking companion to the collected essays in Lateral that complements its aims to inspire imaginative engagements with food.

Foreword by Do Own (Donna) Kim, Assistant Professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, on behalf of the Feeding the Civic Imagination co-editors Sangita Shresthova and Paulina Lanz and the editorial team members at the University of Southern California.

Passing Down and Following Up: Jewish Cuisine’s Umbrella Potential

Jewish cuisine. Certainly a general yet elusive term for a plethora of tastes under one roof. None of the various ideas of this denomination can be identified as wrong if the actors primarily concerned with it – be they religious or rather selectively expressing their belonging – label their cooking and eating as Jewish. From this point of departure, asking for the most authentic dishes or the most Jewish sites, sets irredeemable preconditions.

Jewish cuisine can best be understood[1] as a set of practices and habits of eating and drinking, cooking, and serving, exercised by people considering themselves Jewish.[2] It is at the same time embedded in historical lines of traditions, deriving from religious beliefs and commandments – such as the Kashrut[3] – and influenced by local conditions. This combination makes it at the same time strict and highly reflexive: while the religious prescriptions and the Jewish calendar of festivities often offer a limited space for creativity, the local context and its influence provide for a huge diversity within Judaism worldwide. Merging these two contexts of religion and locality or local heritage – or: the sacral and the profane – constitutes the uniqueness of Jewish cuisine. Jewish communities may all have originated from the Twelve Tribes of Israel, but they have transformed over time and space, moved, merged as well as diverged. So did their cuisine: Jewish cooking and eating is multifaceted and yet highly capable of dialogue.

Including religious as well as cultural traits, the most common division into three groups[4] of Jews worldwide is predominantly based on geographical belonging and the heritage linked to it. Ashkenazi, (originally) Middle- and Eastern-European Jewry, Sephardi, (originally) Jews from the Iberic Peninsula and Northern Africa, and Mizrahi, the third and smallest group, (originally) coming from Caucasus and the Middle East. They are traceable through their cuisines so that people and practices of cooking and eating as forged by Kashrut and its interpretations as well as by local traditions appearing in the regions of origin, in the diaspora, be it in Central Europe or the Americas, and in Israel, as country of religious reference. These Jewish lines of tradition form specific contexts and customs, literally a system of social semantics. With its triadic connection of food, cuisine, and identity, it provides a basis for orientation in, and beyond time and space[5], creating Jewish spheres of connection and identification. Locally diverse yet bound to certain patterns, e.g., dishes for religious holidays such as the Seder plate for Pesach, Jewish cuisine in the past and present is best understood as a pluralistic, inclusive concept. It largely contributes to identity formation and its performance in Jewish communities – be they real, easily identifiable ones like families, neighbourhoods or synagogal communities, or rather abstract imagined communities, dwelling on the idea of a religiously-constructed unity, imagined by individuals who perceive themselves as Jewish[6] – and thus form a conceptual group. Anderson uses this concept to analyse nationalism from a political science perspective. Not only the awareness of nation-building processes though, but also the knowledge about food cultures and the two fields’ analogies can contribute to the understanding of community formation: As exemplified here with Jewish cuisine in all its different facets, the recognition of multilateral embeddedness helps to question and to debunk persistent prejudices. For cultural anthropology, the cooking, eating, and drinking culture is an indicator of superordinate cultural processes and practices, which can be used to grasp social structures with their distinctive features and the ways they are negotiated and performed. Hence, eating is always a cultural act and a “social event”[7]. Therefore, I would like to stress a cultural anthropological point of view, expressed from my non-Jewish, thus outsider position. Yet, exploring the field of Jewish Cuisine (in Europe) in the project FoodGuide “Jewish Cuisine”[8] through participant observation, interviews and of course the tasting of a wide array under the umbrella term “Jewish”, made me an informed outsider with certain experiences in the contexts and customs of e.g., Shabbat meals and the discussions on who eventually invented falafel and hummus. Following this disciplinary positioning, I intend to emphasize the socio-cultural aspects of communities that provide support and exchange of ideas without actually imagining exclusive (national) societies.

Aldea Mulhern pictures this openness of the symbolic community aspect in the “eating Jewishly” foodway – an in-between attempt to harmonize the different spheres – as departing “from standard narratives about Jewish food practice as either eating kosher, or eating traditional Jewish foods [, opening] opens a space for a Jewish food practice that includes both of those modes alongside others, such as food ethics.”[9] This inclusive approach sparks potential for a vivid civic imagination[10] alongside the variety of Jewish cuisine: Making use of civic imagination as “the capacity to imagine alternatives to current cultural, social, political, or economic conditions”[11] opens the discussion beyond the question of what a Jewish cuisine tastes like to the more revealing one on what the concept itself and its practice have to offer – besides flavourful dishes. Bridging gaps of ignorance and ideology through literally sitting at another table, tasting the neighbour’s dish can lead into civic arenas, where discussion is understood as cooperative exchange rather than competition.

A first step in this direction can be to sharpen and to loosen the technical terms at the same time: to emphasize Jewish cuisines’ diversity and to recognize the general fluidity of culture as subject to transformation. Settings of Jewish food culture – and Jewishly food and eating, in Mulhern’s terms – can be found throughout the world but with very different facets and frequencies. Mobility and the need to adapt to their surroundings form a common trait among them. For instance, the “multilingual and poly-cultural regions of Central [and Eastern] Europe”[12] have once been the cradle of Ashkenazi culture. These days they pose a tragic yet excellent example of how Ashkenazim have been subject to boundary shifts and other moments of often brutal hegemony: Smothered by nationalization efforts and close to being erased from the map by the Shoah, Jewish life in the region is nowadays an absolute minority project sometimes occupied by touristic expectations towards an entertaining commemoration.[13] Many Jewish survivors of the Shoah emigrated to the Americas or Israel[14] after 1945, taking their heritage and memories with them. Jewish life in Central Europe is thus largely dominated by a small number of long-established families and – since the 1990’s – a much larger amount of people with Jewish roots, originating from the former Soviet Union[15], who in turn brought their own every day and festive customs. Their search for identity is specifically demanding and was further challenged by a diversifying society: in the second half of the 20th century the appreciation of (seemingly) foreign livelihoods[16] – expressed through every-day culture – brought about by increasing mobility; globalization also became relevant in the field of interest in food culture. Mobility through trade and (forced) migration was historically provoked, but this factor of movement is also key to the popularisation of Jewish cuisine in more recent times.

It’s the Foreign, the Other that fascinates and scares people at the same time.[17] But especially in settings of migration, this otherness can constitute more than differences and separation, especially through the soft power of food[18]: Over time, it’s the “’old world’ foods of Greeks, Jews and Italians in New York”[19] that fundamentally changed eating habits in the ‘new world’; these dishes were transformed from often rather modest all-day or festive, rather scarcely consumed foods to signature dishes. Cream cheese bagels with lox, and pastrami sandwiches are just two examples: “The normalizing absorption of difference in mass culture thereby implies an ongoing appropriation and a becoming at home, i.e. a nostrification of the foreign that - as not only foreign, which […] can lead to the complete de-exoticization of the formerly unknown.”[20] Many of those foods nowadays showcased as ‘typical’ dishes in New York and elsewhere derive from places and people of fairly different backgrounds, contributing to a bigger, post-migrant image of empirical and narrated belonging[21]. Although “the advent of a cosmopolitan and lively urban food culture is not an inevitable outcome of economic globalization”[22], the appreciation of the harmless Other contributed to a diversified society, focused on the singular and unique, as opposed to the standardized products of the 20th and 21st century.[23] In terms of food culture, this valorization of particularities creates a certain dilemma: On the one hand, national or religiously determined cuisines – such as the Jewish – are points of reference to determine similarities and differences. On the other hand, this methodological standardization, the subsummation as solely “Jewish” without negotiating its broad character, neglects the diversity behind these terms and the inherent transnational and -cultural intersections. Leaving questionable evaluation criteria such as the degree of authenticity behind, culinary systems can be regarded as an amalgamation of different prerequisites: Jewish cuisine as a non-national but religiously reasoned umbrella term contains everything from lived and subtle traditions to much younger developments and trends. Jewish cuisine largely varies. Focusing on the self-identification of individuals, leaves room for a set of Jewish dietary rules – the Kashrut –, their varying interpretations in relation to several ways of practicing religion and for locally diverse cuisines that have a Jewish side to them, such as the Jewish-Israeli (or Israeli-Jewish) cuisine of the Mediterranean Levante region or the hearty Polish-Jewish (or Jewish-Polish) cuisine, an ideal type of Ashkenazi food styles, and innumerable others. However, the tension between local and global is also evident here: In times of global food and health trends, borders cannot be sustained any longer as clear-cut concepts. Instead, the sometimes eclectic fusion cuisine[24], an interactive, mostly urban trend, crosses culinary systems, when two or more forces are joined to create new dishes and eating habits. They combine various cuisines to add some spice to the culinary currents “between community, memory and identity”[25]. Kosher Sushi or the Ashkenazi chicken soup Golden Joich, aromatized with lemongrass emerge from this dynamic trend “of combining foods from more than one culture in the same dish”[26]. The line between solely and exclusively “Jewish” and “non-Jewish” food thus becomes blurred, if it ever existed at all. Mobility and exchange prove to be as crucial for Jewish history and religious (self-)understanding as for its cuisine.

Established in 2017, the “Jewish Food Society”[27] approaches the branches of Jewish cuisine by following up on passed down family recipes and their origins. It also dwells on the emotions connected to them, testified by family members. The digital archive “works to preserve, celebrate and revitalize Jewish culinary heritage from around the world” through storytelling. Recipe books, cooking tools or certain dishes as well as non-tangible memories of cooking and eating can be understood as family heirlooms, “associated with Jewish cultural heritage that have been passed down through a family over several generations […] important for the formation of collective memories”[28]. Even though it is to question, if traditions, such as recipes, can in fact be passed on over more than three generations, or, which degree of consistency and stability in looks and taste must be present in the dishes that continuity is assumed, the emotions connected to this practice of creating heritage are the actual transmitter. Shared heritage is therefore vital for the creation of affectionate, intergenerational bonds. With people migrating, these bonds have become inter- and transnational. The platform can thus be a vehicle to imagine what can be created, when open-mindedly building up on the passed down: It fosters on the one hand side a community of shared memories, and, on the other hand side, contributes to a valorization, yet not a frantic clinging to these memories and recipes as heritage. Consequently, in an online archive, the aspect of contributing is the key to this process of sharing inspiration.

The homepage of the Jewish Food Society, a “a non-profit organization that works to preserve, celebrate, and revitalize Jewish culinary heritage from around the world in order to provide a deeper connection to Jewish life.” (https://www.jewishfoodsociety.org/about).[29]

The families presenting their recipes, mediated by the team of the open-access platform, are these days often located in the US, Israel, or Western European countries such as France or Great Britain. But their ancestry is much more diverse: Old-worldly Ashkenazi and Sephardi livelihoods are the background for the culinary family heritage. Migration stories from the 19th and 20th century up to today – often but not necessarily related to Shoah[30] – form the path of intergenerational, transnational, often also multiethnic and -religious relations through food practices. The recipes’ “roots and routes”[31] describe the ways of immigrant integration[32] – and, vice versa, the incorporation from the immigrants’ side –, a gradual process in which definitions of belonging, of out- and in-side are challenged over and over again. When the family of Becca Gallick-Mitchell[33] celebrates Thanksgiving, a genuine North American family feast, centring around a shared table, they already have a leftover recycling method in mind, “tempted to carve the turkey poorly, leaving more meat on the bones”[34]. The leftover meat is then used to stuff Kreplach, a traditional Ashkenazi dumpling, filled with meat, potatoes, or what is at hand. Their beloved five-generation old recipe, originating from Poland, preserved through the Lodz Ghetto and emigration to the US by their grandmother Mala, serves as a follow-up on the feast they accustomed to in their adult life, mixing local and Jewish customs to create family traditions. Cherishing memories and reliable practices, such as extensively tried and tested recipes, delivers a basis to intergenerational communication. Since the experiences of first- or second-generation immigrants differs significantly from those their children and grandchildren make in a substantially multifaceted environment with loosened bonds to their family’s region of origin, generational gaps do appear e.g., in the mode, quantity, and frequency in which dishes are prepared[35]. Their situation within “a variety of different and often competing generational, ideological and moral points of reference, including those of their parents, their grandparents and their own real and imagined perspectives about their multiple homelands”[36] further complicates the creation of a common identity.

(Post-)Thanksgiving Kreplach - a mean for intergenerational communication and memory (https://www.jewishfoodsociety.org/stories/a-fifth-generation-thanksgiving-kreplach-tradition).

Nevertheless, “food as a bastion of […] religious, spiritual and cultural identity”[37], is a soft though powerful approach to resilient relations, when regarded with a certain openness for its combinability. The descendants of Marie Immerman[38], a first-generation American of Ukrainian origin, are still fond of her sixth generation Coleslaw recipe, likewise a Thanksgiving staple – “simple but trusty.”[39] At the same time, they are adding their personal twists to it: When Jo Betty Sorensen’s mother came to visit “it was interesting because she would grate onion,” while Jo herself would use onion powder.[40] Jo Betty summarizes this observation according to the changing environments the dish has been prepared in and the respective technologies and food trends: “With recipes, people make it their own.”[41]People in specific local, sociocultural contexts inherit their family recipes and adjust them to their needs. Cooking and revising the inherited recipes can thus be a field of intergenerational interaction, including multiple ties not to change but to subtly adapt a dish to make it a lasting, contemporary product. Same applies to Claude and Anna Polonsky’s family[42]: Their Ashkenazi apple strudel – itself a dish with Habsburgian heritage – evolved over time and became an “updated” Ashkenazi-French strudel aux pommes, prepared close to the famous French Tarte Tatin recipe.[43] By re-creating recipes, they are adding up more and more layers to their shared family history, breaking culinary and national borders but are still staying within the frontiers of the well-known.

Combining religious, national and family holidays to create a personal “culinary canon” (https://www.jewishfoodsociety.org/collections/thanksgiving-recipes).

As Cañás Bottos and Plasil point out for the Levantine and Mizrahi migration to Argentina, four mechanisms – packaging, grinding, mixing and blending[44] – are responsible for the inclusion of migrants and their cuisines in the settling country – and vice versa: People and food are packaged (or labelled) under graspable terms (here: Arab). Especially the following generations are grinded in by language acquisition and schooling. Local circumstances and resources are (partly) mixed with known ones and can even replace those; they blend. The creation of new combinations, such as the post-Thanksgiving-Kreplach, the use of onion powder instead of freshly grated onions, and the preparation of an apple strudel according to French culinary concepts are examples of a process, where cooks and eaters alike are creating a form of “translocal consumer product”[45] with a transgenerational side to it, characterized by various transfers.

This renders the notion of traditional or authentic cuisines highly questionable. Is not almost every dish – especially the nationalized ones – a migratory product, be it the Italian(-American) Pizza with its tomatoes, deriving from Columbian Exchange, or the (stereotypical) German lust for potatoes, stemming from the same place, South America? Yet disputable enough from this radical point of view, one must admit that cuisines are – like the communities they are created in – at least partly imagined, yet highly effective supporters of identity.[46] Collectivity is created through assumptions of standardized belonging, expressed in shared names, dishes and practices, neglecting specificities and other possible dissensions within that frame: same but different. Community cuisines have become more than just necessities – they are cultured, ritualized, traditionalized eating habits. That valuable heritage, passed down and followed up, is kept in their respective families and – see Jewish Food Society – distributed through digitally mediated, yet emotional storytelling, closely relating them to sharing foodstuffs and memories themselves. Preserving recipes for your grandmother’s or -father’s stew is one step in keeping history and its stories alive – but they need to be stirred well from time to time. The act of preserving the old and known might sound like a conservative claim to keep it that way. Still, it can certainly be used in a more productive, proactive way: it can pave the way to a general openness based on recipes as orientation tools and resilient transmitters of emotional bonds. Sharing, trying, and adapting them to today’s needs and beyond offers a glimpse into organic practices of how age-old, non-trivial approaches to e.g., food and nature, food and work, or food and family are intertwined with recent perspectives and challenges. Especially the interconnection of food and migration proves eating culture to be at the same time an artefact of and a glimpse into diversifying, often parallel running patterns of belonging – as here, under the same umbrella of the Jewish cuisine. Therefore, the understanding of these cooking traditions and its transmission is to be read from a resourceful, layered perspective: Jewish Cuisine goes beyond the standard-distinction between Ashkenazi : Sephardi : Mizrahi. It has its feast and its fasting, its seasons and styles, its taboos, and sweet treats – and is spelled out best as pluralistic Jewish Cuisine(s): religious in different intensities and secular, regional and global, fusional, traditional, and re-invented. Everything can be Jewish – and, if not, possibly Jew-ish[47]. In the kitchen, on the plate and beyond, no “either-or”, but a promising “as well as” is crucial for sparking inclusive imagination, for mixing and blending to create dishes not yet tasted. Imagining culinary possibilities is therefore imagining participation, connection, and cooperation.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank the team of FoodGuide “Jüdische Küche”, particularly my colleague Antonia Reck, for their support and input in the development of this text - herzlichen Dank!

Author Bio

Jana Stöxen is a doctoral candidate in Comparative European Ethnology at the University of Regensburg (Germany) and holds a scholarship of the Friedrich-Ebert-Foundation (FES). She is currently working ethnographically on transnational migration and diasporic practices between the Republic of Moldova and Germany. Prior to this, she has been a research associate in the project FoodGuide “Jüdische Küche” on Jewish food and cuisine in Europe. Her research interests lie at the intersection of transformation and migration, and within the spectrum of food and home-making, particularly in post-socialist and transnational contexts.

Contact:

jana.stoexen@gmx.de

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jana-Stoexen

Notes

[1] See: Paulette Kershenovich Schuster, “Habaneros and shwarma. Jewish Mexicans in Israel as a transnational community,” Religion and Food, Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis 26 (2015): 281–302, 285. doi:10.30674/scripta.67458.

[2] Gunther Hirschfelder, Antonia Reck, and Jana Stöxen, „Jüdische Esskultur: Traditionen und Trends,“ Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte. Jüdisches Leben in Deutschland 44-45 (2021): 35-41, 35. [original in German; translation by the author]

[3] “Kashrut” is a set of Jewish religious laws, concerning rituals and dietary prescriptions. The term most commonly associated here is “kosher” – the (ritual) “suitability” of certain, e.g. alimentary “pure” products, as pointed out by the Kashrut.

[4] These “groups” share common traits but are within themselves highly heterogenous. Still counting them, based on the combination of religion and ethnicity or heritage, as “groups” is thus a rather pragmatic approach to conceptualize Jewish people and their traditions. However, “groupism” is to be criticized if it goes beyond the methodological sorting and negates intersectional identities and/or personal characteristics.

Also see: Rogers Brubaker, “Ethnicity without groups,” Ethnicity, Nationalism, and Minority Rights (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 50–77, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511489235.004.

[5] See: Gunther Hirschfelder, „Pelmeni, Pizza, Pirogge. Determinanten kultureller Identität im Kontext europäischer Küchensysteme,“ in Russische Küche und kulturelle Identität, ed. Norbert Franz (Potsdam: Universitätsverlag Potsdam, 2013), 31-50, 32 ff. [original in German; translation by the author]

[6] See: Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London; New York: Verso, 1991), 6 f.

[7] Johanna Mäkelä, “Defining a Meal,” in Palatable Worlds. Sociocultural Food Studies, ed. Elisabeth Fürst, Ritva Prättäla, Marianne Ekström et al. (Oslo: Solum Forlag, 1991), 87–95, 92.

[8] Gunther Hirschfelder, Jana Stöxen, Markus Schreckhaas, and Antonia Reck. Foodguide Jüdische Küche: Geschichten I Menschen I Orte I Trends (Leipzig: Hentrich & Hentrich, 2022).

[9] Aldea Mulhern, “What does it mean to ‘eat Jewishly’? Authorizing discourse in the Jewish food movement in Toronto, Canada,” Religion and Food, Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis 26 (2015): 326-348, 327, doi:10.30674/scripta.67460.

[10] Henry Jenkins, Gabriel Peter-Lazaro, and Sangita Shrestova, Popular Culture and the Civic Imagination: Case Studies of Creative Social Change (New York: New York University Press, 2020).

[11] Ibid. 5.