Henry Jenkins's Blog, page 11

February 10, 2023

Chernobyl Reloaded: Renewing Traditional Male Heroism Through Female Characters

This is the second in a series of perspectives on HBO’s 2017 series, Chernobyl.

Chernobyl reloaded: Renewing traditional male heroism through female characters

Charo Lacalle (Autonomous University of Barcelona)

As highlighted in various studies on the miniseries, the protagonism and tragic fate of Valery Legasov (Jared Harris) and Boris Shcherbina (Stellan Skarsgård) in Chernobyl grants them an absolute pre-eminence. This work, however, vindicates the narrative prominence of the two female characters, who rework the male Homeric models of heroism: Lyudmilla Ignatenko (Jessie Buckley), the wife of one of the first victims of the nuclear accident, and Ulana Khomyuk (Emily Watson), the scientist who travels to Chernobyl to determine the causes of the explosion at the nuclear power plant. Both women, who initially complement the firefighter Vasily Ignatenko (Adam Nagaitis) and the scientist Legasov plots respectively, subvert the men's protagonism by forging their own narrative trajectories: Lyudmilla's desperate struggle to find her husband and support him in his agony, and Ulana's collaboration with Legasov to halt the spread of the radiation.

Free from the servitude to the power governing the destinies of Legasov (deputy director of the Kurchatov Institute) and Shcherbina (deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers), the two women endow the miniseries with the necessary "moralizing impulse" present in any account of reality where narrativity makes the world speak itself as a story (White, 1980). Lyudmilla constitutes one of the most disturbing voices of the survivors, recounted by Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich in her acclaimed work Voices from Chernobyl. The oral history of a nuclear disaster (2006[1997]). Beyond Luydmilla's characterization as a wife, her primary narrative function consists of developing a sentimental subplot, aimed at suturing from the emotional dimension the distance between the viewer and the documentary exposition of the events. Ludymilla's love for her husband drives her to disobey the prohibition on approaching or coming into physical contact with him, to the point of risking her own life and even that of the unborn child she carries to be with him in his death throes. By contrast, the fictional character of Ulana is based on an amalgamation of many unnamed scientists who struggled to unravel the true causes of the catastrophe and "to honor their dedication and service to truth and humanity", as the miniseries credits inform the viewers.

Adam Higginbotham, a former British correspondent in the USSR and author of Midnight in Chernobyl, which won the 2020 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence, criticizes Chernobyl on the premise that there was no need for a crusading whistleblower to uncover the causes of the catastrophe. The journalist also questions the plausibility of Ulana's portrayal as not reflecting reality in terms of the position of women in power-appointed bodies in the Soviet Union in 1986. Sonja Schmid considers instead that while Ulana effectively erases the names and efforts of many other people, her character illustrates that Soviet women were top scientists and fearless investigators at that time. Schmid (2020: 1161) praises Higginbotham's book, but argues that the miniseries should be enjoyed for what it is: "an engaging storytelling with extremely felicitous reconstructions of the accident and Soviet material life".

Emily Watson, who plays Ulana, goes further by considering Chernobyl a politically astute and essential piece of work, and she even attributes her character to a hypothetical past anchored in Ukrainian history to justify her inclusion in the miniseries: "My character would've been a child during World War II, and from Belarus — one of the worst places on the planet to be in the 20th century. Just astonishing. Horrific treatment from every direction. She would've grown up incredibly tough […] As a child, she lived through extraordinary brutality and probably was witness to appalling acts. She developed a 'don't trust anybody' mentality" (Watson in Nicolau, 2019).

Be that as it may, it is worth recalling that the number of women in the field of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) in the USSR even exceeded the average for Western countries in the period of the disaster, despite Soviet women scientists' difficulties to pursue their profession and conciliate it with their family life were systematically on Mikhail Gorbachev's agenda (Evans, 2012). In this sense, the discussion of plausibility should not overshadow the need to highlight the achievements of women scientists in Western, where the media plays a key role in spreading the research results. Most of all, because disregarding women's STEM achievements stimulates the creation of negative myths and misconceptions about women scientists' and therefore contributes to their social discrimination.

From heroes to heroines

The contrast between the ideal (Ulana) and real (Lyudmilla) characters installs in Chernobyl's narrative logic an opposition between emotion and reason around which the text's axiological system is articulated. Both women symbolize two classical versions of heroism, which Mark Edmunson (2015) identifies respectively with the figures of the warrior and citizen soldier: Achilles and Hector. And with this recognition of the typically masculine andreia/ἀνδρεα (manliness, bravery) in the two female characters, the miniseries subverts the traditional concept of heroism.

Like Achilles, Ulana chooses to set off to war from the Nuclear Energy Institute in Minsk (Belarus), where she works. This fictional character, whose sole dimension explored in Chernobyl is her portrayal as a scientist (everything concerning her personal sphere is unknown), embodies the ideal of perfection in that she will not be fu And it is this recognition of the typically masculine andreia/ἀνδρεα (manliness, bravery) in two female characters, that manages to subvert the traditional concept of hero.lfilled until she has completed her particular quest for truth. Ulana has the pride and self-confidence attributed by Edmunson to the Homeric hero she embodies, which places her beyond fear and weariness. Aware of the limits imposed on Legasov by his Communist Party membership, but also that those in power will never hear her own voice, Ulana urges him to take on the system to defend the truth "Because you're Legasov. And you mean something. I'd like to think if I spoke out, it would be enough. But as I said, I know how the world works" (fifth episode).

LEFT: El trunfo de Aquiles (Franz von Matsch, 1892) RIGHT: Ulana khomyuk

Unlike Ulana/Achilles, Lyudmilla is forced to acquire the fighting spirit natural to a warrior. Lyudmilla/Hector is the citizen soldier who fights to defend what she loves; although she does not fear death, she must learn heroism. Hence, like the hero who inspires her, this female character is both the brave fighter and the pater familias. Her journey from Pripyat - the city where the Chernobyl power plant is located - to the Moscow hospital room where her husband is dying constitutes the initiatory journey of a woman who, like Ulana, also rebels against impositions.

LEFT: The Farewell of Hector to Andromaque. RIGHT: Astyanax Lyudmilla and Vasily (Karl F. Deckler, 1918)

As the narrative unfolds and Ulana and Lyudmila come to the fore, the viewer empathizes with their respective points of view. Impervious to the constrictions of the rise and fall of tragic heroes, the warrior Ulana and the citizen soldier Lyudmila represent the characters through whom the miniseries pays homage to the bond between women and nature. Both archetypes thus evince Chernobyl's alignment with today's eco-feminist sensibility, which calls for women's involvement in environmental issues (Rigby, 2018: 61). And so doing, the conciliation between heroism - a characteristic associated by dualism with masculinity - and compassion - traditionally attributed to femininity - merge into a message of hope, which transcends desolation to penetrate the spectators' sensibility and alert them to the nuclear risk.

References

Alexievich, Svetlana (2006[1997]) Voices From Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster. Picador.Evans Clements, Barbara (2012) History of Women in Russia From Earliest Times to the Present. Indiana University Press.

Higginbotham, Adam (2019) Midnight in Chernobyl: The untold story of the world's greatest nuclear disaster. Bantam Press.

Nicolau, Elena (2019) "She Was A Truth Ninja:" Emily Watson On Her Intrepid Chernobyl Character. Available at: https://www.refinery29.com/en-gb/2019...Schmid, Sonja D. (2020) Chernobyl TV series: O suspending the truth of what’s the benefit of lies? Technology and Culture, 61(4), 1154-1161. doi: https://doi.org/10.1353/tech.2020.0115

Watson, Fay (2019) Chernobyl explained: Is Emily Watson's character Ulana Khomyuk a real person? Express, July the 15th. Available at https://www.express.co.uk/showbiz/tv-radio/1139105/Chernobyl-explained-Is-Emily-Watson-s-character-Ulana-Khomyuk-a-real-person-hbo-seriesWhite, Hyden (1980) The value of narrativity in the representation of reality. Critical Inquiry, 7(1), 5-27.

Biography

Charo Lacalle is Full Professor at the Autonomous University of Barcelona-UAB (Department of Journalism and Communication Sciences), where she teaches Semiotics and Narratives. She has two degrees, in Journalism and in Philosophy, and a PhD in Communication Sciences. She started my academic career as an assistant in the Faculty of Languages and Literature at the University of Bologna. Her research activities focus on Semiotics, TV and internet studies, media cultural analysis (particularly about fiction and entertainment genres), feminist studies, intermediality and fandom. Her last book explores de social role of media in the construction and dissemination of dignity and indignity: (In)dignidades mediáticas en la Sociedad digital (Catedra Editors, 2022).

February 9, 2023

Remembering (and Refiguring) Chernobyl: What Can be Learned from the HBO (2019) Series?

This is the first in a multipart series offering transnational and interdisciplinary perspectives on the 2019 HBO series, Chernobyl.

Remembering (and refiguring) Chernobyl:

what can be learned from the HBO (2019) series?

Nicola Dusi (University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Italy)

Charo Lacalle (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain)

The premiere of Chernobyl (HBO-SKY, 2019) recalled the greatest man-made catastrophe in human history and the enormous damage on both living beings and the environment. This "historical drama" —as the critics labelled the miniseries— made nuclear disasters once again the focus of public attention, after being overshadowed in the last two decades by the increasing dramatization of other risks (such as climate change).

Created by the experienced director and screenwriter Craig Mazin, Chernobyl asserts the role of media in the recovery and dissemination of historical and cultural memory (Rampazzo Gambarato, Heuman and Lindberg, 2022). The miniseries also corroborates the intermediality of television fiction and its capacity to touch the deepest and most complex dimensions of our existence (Pallarés-Piquer, Hernández, Castañeda y Osorio, 2020). In this sense, it can be said that its value lies not so much in evoking a past that can no longer be changed, “in a risk society, where history offers no guarantees” (Giddens & Pierson, 1998: 157), but in appealing to human responsibility so that this type of catastrophe will never happen again.

Russia's invasion of Ukraine and its control of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant —the largest in the world— makes Chernobyl a wake-up call for the fear of another explosion. Such a concern was expressed by the director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Rafael Grossi, after his visit to the installations at the end of August 2022. "It could be a bigger disaster than Chernobyl," warns Carlos Umaña, co-chair of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW). As it is, Mazin’s miniseries makes us feel skeptical about the European Union's February 2022 proposal to grant "green" status to nuclear power at least until 2025 on the premise that it is consistent with the EU’s climate and environmental objectives.

The risk society

Sociologists of Modernity Ulrich Beck and Anthony Giddens use the concept of risk society to express the anthropogenic manipulation of nature and the concern for the future of humanity, at a time when it is no longer possible to attribute catastrophes to, “an external intervention of hazards” because risks depend on decisions (Beck, 1992[1986]:183). The risk society theory also expresses the way contemporary society organizes itself in order to manage the consequences of human agency in what is referred to as the Anthropocene: the new stage of the current Quaternary period shaped by the actions of humankind thought to have succeeded the Holocene or post-glacial period (Boyd, 2009; Crutzen, 2002).

As the Australian philosopher Toby Ord points out in his influential book, The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity (2019), the certainty that we are at a crucial turning point in the history of the human species, whose greatest challenge is to safeguard the future of humanity, clashes head-on with the lack of maturity, coordination, and perspective needed to avoid ecological disasters. In keeping with the stories about the effects of the Anthropocene, the Chernobyl series’ mixture of fiction and facts and narrative strategies illustrates the horror of a nightmare from which we can never entirely escape, because it is something that could possibly happen again. After all, “Russia effectively is using the plant at Zaporizhzhia as a pre-positioned nuclear weapon to threaten and intimidate not only Ukrainians but millions of Europeans across a dozen countries,” writes Mary Glantz (2022), Senior Advisor for Russia and Europe Center of US Institute of Peace (USIP).

Complex TV, Intermediality and Transmediality

The Chernobyl TV series opens many possible issues, and in this thematic section of the blog, we will address some of those issues that are part of our research topics. Like many new contemporary TV series, Chernobyl can be considered a case of what Jason Mittell (2015) calls "complex TV." It is no longer a matter of analyzing a TV series as an isolated and autonomous media product. It is important to understand the miniseries' choice of discursive genre and format (Giorgio Grignaffini); to examine the narrative structure of the script (Paolo Braga), and the construction of male (Andrea Bernardelli) and female characters (Charo Lacalle), as well as to analyze the collision or interplay in the series between its fictional capacity and its documentary aspirations (Nicola Dusi), as is evident in the miniseries' finale (images of the fictional narrative are replaced by those of iconographic and historical sources). While analyzing the TV series, we will talk about the Chernobyl disaster as a social and cultural trauma (Antonella Mascio), about the TV series and the elements of modern sacrifice (Alberto Garcia), and about the representation of the Cold War and the manipulation of information (Federico Montanari). All this without forgetting "traditional" viewers and their reactions, for example in a particular local setting such as Greece (in Europe), verifying with qualitative sociological analysis (interviews) the reception and understanding of the TV series’ narrative (Ioanna Vovou).

TV seriality, as Chernobyl teaches us, thrives on the intermedial and transmedia relations that are created through the paratexts, the commentaries, the reinterpretations, and interpretations that circulate on the web in the transmedia storytelling of the Western semiosphere (to limit ourselves to this part of the world).

Therefore, the discussion we open in these pages faces the intermedial interweaving of footage, allusions, quotations, and translations, which the Chernobyl series activates from the writing of the script to the shooting and the postproduction editing. Think, for example, of iconographic sources, literary sources, and historical sources, including written (investigative literature, journalistic reports, historical documents), visual (photographs, drawings) and audio-visual (footage from the period, interviews, television reports). The comparison and discussion also becomes a transmedia problem, as the series is reopened and discussed weekly (during its airing) through some detailed podcasts by HBO with interviews with the showrunner Craig Mazin and other members of the production team. As Jenkins (2006) claims, this kind of transmedia storytelling features the TV series narration and story world on other platforms, where each medium retells them in the way that suits it best.

The transmedia and crossmedia products are a swarm of new interpretations, controversies, and discussions about the truthfulness and the accuracy of the choices of the Chernobyl serial’s narrative, which produce new videos, remixes, articles and statements in which a close scrutiny and exchange of views is conducted about the sources and testimonies used in the TV series. Lots of reinterpretations, often critical and highly polemical, are given by web prosumers intent on discussing (even with fairly obvious tendentious purposes) a serial narrative that casts a cold and negative light on the Soviet regime and its manipulative and falsifying handling of the nuclear disaster through the information provided about the catastrophe both as it occurred in 1986 and in the following years.

For these reasons, some contributions to the discussion we are presenting will take into account intermedial intersections with other media products (other series, films, documentaries, but also novels and documentary photographs, etc.) on the one hand, and on the other, transmedia and crossmedia overlaps and reinterpretations (through production podcasts, but also through the autonomous and grassroot productions of web users).

Our proposal stems from a panel discussion that took place at the University of Thessaloniki during the World Semiotics Conference (IASS/AIS) in August-September 2022, but has been extended (for this blog) to other scholars and researchers interested in the analysis of contemporary television seriality and its psychological, social, and semiotic implications and constructions.

References

Beck, Ulrich (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity. Sage Publications.

Boyd, Brian (2009). On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction. Harvard University Press.

Crutzen, P. J. (2002). Geology of mankind. Nature 415(23).doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/415023a

Giddens, Anthony; Pierson, Christopher (1998). Making sense of Modernity. Polity Press.

Glantz, Mary (2022) Russia’s New Nuclear Threat: Power Plants as Weapons. United States Institute of Peace. Available at: https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/08/russias-new-nuclear-threat-power-plants-weaponsJenkins, Henry (2006). Converge Culture. Where Old and New Media Collide. New York University Press.

Mittell, Jason (2015). Complex TV. The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling. New York – London: New York University Press

Ord, Toby (2019). The precipice: Existential risk and the future of humanity. Hachette Editions.

Pallarès-Piquer, Marc; Hernández, J. Diego; Castañeda, W. José; Osorio, Francisco (2020). “Vivir tras la catástrofe. El arte como intersección entre la imagen viviente y la conciencia. Una aproximación a la serie “Chernobyl” desde la ontología de la imagen”. Arte, Individuo y Sociedad 32, 738-798. doi: https://doi.org/10.5209/aris.65826

Rampazzo Gambarato, Renira; Heuman, Johannes; Lindberg, Ylva (2022). “Streaming media and the dynamics of remembering and forgetting: The Chernobyl case”. Memory Studies, 15(2), 271-86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/17506980211037287.

January 16, 2023

“Part of Your World”: Fairy Tales, Race, #BlackGirlMagic, and The Little Mermaid

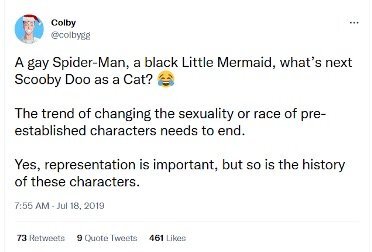

In 2016 Disney announced a live-action adaptation of its 1989 animated film The Little Mermaid. Loosely based on Hans Christian Andersen's 1837 fairy tale, the animation earned critical acclaim, took $84 million at the domestic box office during its initial release, and won two Academy Awards (for Best Original Score and Best Original Song). Given Disney’s recent foray into creating live-action adaptations of some of its most successful animated films, it’s no surprise that The Little Mermaid was added to the list. Yet controversy rose when Black actress Halle Bailey was announced as Ariel in July 2019. Among the critiques was the argument that the adaptation should be as close to the original as possible, and the original featured a white mermaid; that if a Black character was re-cast as white in a remake there would be uproar; and while representation in all forms is important it shouldn’t override the history of the characters (Figure 1.1):

Figure 1.1: Tweets discussing the casting of Ariel when Halle Bailey was originally announced in 2019

“This film ruined my childhood!”Adaptations and remakes are often contentious topics because fans can have deeply emotional connections to the original text. Disney animations in particular often hold a nostalgic appeal for adults who grew up with the original films, and for whom they hold ties to a different - perhaps better - time. Yet negative responses to remakes which feature Black actors go beyond the ‘purist’ argument which states that adaptations and remakes should remain true to the original. A key example of this is the 2016 Ghostbusters remake which featured an all-female team of ghostbusters. The gender-swap of the ghostbusters themselves is criticized, but the majority of vitriol was directed against Black actress Leslie Jones. We have seen over the last decade or so the way that social networking sites can “promulgate sexually violent discourse and expand the opportunities to shame and humiliate women” (Horeck 2014, 1106). Twitter became one of the main spaces used to target Jones, with the star herself sharing just some of the many horrific tweets (Figure 1.2) that she had been sent:

Figure 1.2: Racist tweets directed at Leslie Jones following the 2016 Ghostbusters reboot

This language clearly shows the racism inherent in many viewers’ reactions to the film, and while this overt hate speech is horrific to see, there were other, more insidious racist responses to the film. One of the most frequent reasons for dislike of the Ghostbusters reboot was that it affected fans’ memories of the original - a common refrain highlighted in discourse around the film was that it ‘ruined my childhood’. Nostalgia thus became a coded way for some fans to perform racism, framing a childhood classic - where straight, white men were the default in film and television - as the norm and any attempt to change that as ‘wokeness gone mad’.

We see some of these more covert racist responses in reactions to The Little Mermaid. The trailer for the adaptation was released in September 2022, giving viewers their first glimpse of Halle Bailey as Ariel, singing “Part Of Your World”. Immediately comments began circulating on social media sites criticizing the casting as Disney pandering to the woke brigade, diversity for diversity’s sake, and another example of social justice warriors ruining popular culture (Figure 1.3):

Figure 1.3: Tweets responding to the first The Little Mermaid trailer, released in 2022

For these viewers then, their opposition to the recasting of Ariel isn’t because they’re racist; it’s because they see a concerted effort being made in popular culture to force an ideology, they feel isn’t necessary, despite that ‘ideology’ being an attempt to redress the decades of racism evident in both the production of film and television content and the representations within that content. Of course, this is still racism. It’s just couched in language that frames these as legitimate concerns. So, while questions like ‘instead of remaking this film why don’t they produce a film based on African folklore?’ may seem valid on the surface, they ignore the systemic racism within the industry and the difficulty in pitching, commissioning and making a profit on non-white content.

Before Halle there was Mami Wata…While the original fairy tale from Hans Christian Andersen does describe Ariel’s character as “her skin was as clear and delicate as a rose-leaf, and her eyes as blue as the deepest sea” this does not mean that there were no mermaids who were of color. In fact, water spirits and Black mermaids existed even before Christian Andersen’s 1837 fairy tale. It is important to note the global history of mermaids and water spirits due to the fact that the existence of Black characters in fantasy, magical realism, and science-fiction is often non-existent. If we think about this from an Afrofuturistic lens, these early Western tales did not see Black characters as even being a part of these narratives. The waters have always been seen as a sacred space literally and figuratively within African folklore. Housed within many African traditions, the water serves as a bridge between otherworlds, life and the afterlife. And the sea deity Mami Wata or La Sirene (which translates as Mother Water or Mother of Water) serves as the beginnings of many African mythical tales. Described as having a female human torso, sometimes with a serpent wrapped around her, with a tail like a fish, and hair that can be straight, curly, or wooly the image (see Figure 1.4) could be likened to that of Halle Bailey. Nevertheless, the idea of mermaids has had a long African tradition. In South Africa, there is a myth from the Khoi-san people about the Karoo Mermaid that was discovered in the Cango Caves, in Mali the Dogon people have an origin story involving fish creatures called “nommos”, and in Nigerian Igbo tradition Mmuommiri ("Lady of the waters"). The water spirit also translates into Caribbean and South American tales through the orishas of Yemonjá (or Yemanjá) in Brazil and Yemanya (or Yemaya) in Cuba; and River Mumma, River Mama in Jamaica, and Maman de l'Eau ("Mother of the Water")/Maman Dlo/Mama Glo in Dominica.

Figure 1.4 [l-r] Sculpture of the African water deity Mami Wata. Nigeria (Igbo)-Original in Minneapolis Institute of Art and Dona Fish Ovimbundu peoples-Angola-Private Collection-Photo by Don Cole

Moreover, this narrative has and continues to be re-written to include and normalize Black bodies in the fantastical and mythical space. For example, author, filmmaker and Afrofuturist Ytasha L. Womack brings attention to the presence of these magical creatures in her chapter “The African Cosmos for Modern Mermaids (Mermen)” in her 2013 book Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture; Afro-Futurist artist, writer, and educator D. Denenge Akpem recreated her own water fairy tale reminiscent of African mermaids by transforming herself into a space-sea-siren-hybrid-human-jellyfish for a 2006 exhibition show at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA)-Chicago; and Nigerian-Welsh writer Natasha Bowen would create a literary series of African mermaids based in West African tradition through her YA/fantasy novels “Skin of the Sea” (2021) and “Soul of the Deep” (2022) which follows Simi, a ‘mami wata,’ that travels across sea and land in search of the Supreme Creator. Additionally, Ta-Nehisi Coates makes references to Mami Wata in his 2019 novel "The Water Dancer" as well as Nalo Hopkinson making the key figure ‘Lasiren’ a part of her 2003 erotic historical fiction novel “The Salt Roads,” and the 2022 film Nanny depicts the figure of Mami Wata in relation to the main character Aisha. Each of these mediums of past and current history provide a plethora of historical context for the casting of Halle Bailey in the role of Ariel. As noted by Bowen, “I think speaking from Black mermaids, we need to see ourselves in positions as magical creatures. There's all the furo about Black people in fantasy. And I think that it's important for us to see ourselves — to have that freedom of imagination. And I think it's important for everyone else to see us in those roles as well.”[1]

“She’s Black! Oh, my God!”In the same vein, the news of the live-action adaptation also garnered a #BlackGirlMagic effect that would have just as much excitement across social media. This is not surprising as there has always been a history of Black audiences wanting to see themselves represented in a way that is not stereotypical, campy, or cliched. However, the move on Disney to celebrate and include a diverse cast is an encouraging move towards embodying the idea of “#RepresentationMatters. Having the teaser trailer center the introduction of Halle Bailey as Ariel makes a strong statement of how narratives can change. Her presence in just the teaser trailer ushers in an opportunity for Black girls to see themselves as magical as well as for other young girls to see a manifestation of what can be beyond the westernized white princess. In Disney’s almost 100-year history there has been only one Black Disney princess — Princess Tiana in “The Princess and the Frog (2009),” which was voiced by Anika Noni Rose. And similar to the casting of Halle Bailey as Ariel, singer Brandy portrayed “Cinderella” in the 1997 made-for-TV film version remake of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical. Thus, the addition of the upcoming live-action of The Little Mermaid is very much welcomed.

Evidence of this welcoming was seen in an array of TikTok videos. For many parents, having tangible representations of characters that resemble and look like their children is essential and necessary. In a reaction on TikTok from the Lanier family, it features the three children getting ready to watch The Little Mermaid teaser. Their excitement is captured and is filled with joy (Figure 1.2), “She’s Black! Oh, my God!” exclaimed a wide-eyed Madison (11), followed by their brother Carter (6) shouting “Yes, yes, yes!” with a final reaction from McKenzie (9) “I can’t wait to see this!”

Figure 1.5- https://www.tiktok.com/@mrshannonlanier/video/7142462207656332587

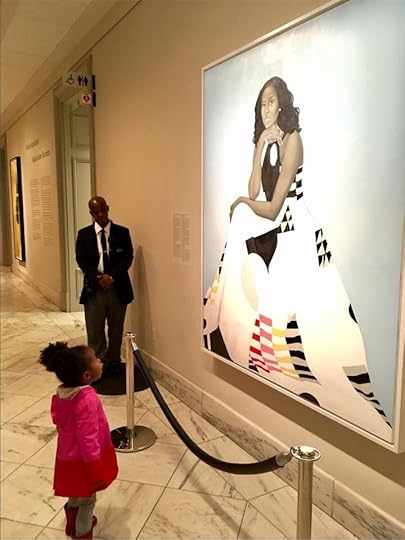

Since the teaser trailer dropped in September 2022, many parents have been flooding the TikTok space with reactions to seeing a Disney princess who looks like them. The reaction to Bailey as Ariel is also very reminiscent of the young Parker Curry’s reaction to the Michelle Obama portrait at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC (Figure 1.3). While the teaser is only a little under one minute and a half, its impact is leaving a long-lasting imprint. With a slow, steady increase of Black girl representation particularly in film and television, The Little Mermaid has the potential to become a part of a legacy that does not diminish Black girl’s imaginations but revitalizes them and makes them a fantastical reality. Even for Bailey, she understands the significance of playing this role, in an interview with Variety magazine she notes, “What that would have done for me, how that would have changed my confidence, my belief in myself, everything…Things that seem so small to everyone else, it’s so big to us.”

Figure 1.6: Parker Curry in awe of seeing the National Portrait Gallery painting of Michelle Obama, Photo credit: Ben Hines

It will be interesting to see how the reactions change or stay the same once the official trailer drops and we visually see the other characters, especially the six other sisters. Since there are seven daughters total, representing the seven seas, the representation of each which is rumored to be from different racial/ethnic backgrounds will be one that probably causes a mix of emotions. Once the rest of the cast is announced and the official trailer is dropped, the conversations will only increase and become even more layered. Moreover, the teaser is an example of a filmic litmus test used to get the ball rolling to see what the response would be and ultimately show people what Halle Lynn Bailey is going to bring to the table as Ariel.

[1] Headlee, C., & Saxena, K. (2022, September 30). Long before 'The little mermaid' remake, Black mermaids were swimming through African folklore. WBUR. https://www.wbur.org/hereandnow/2022/09/30/black-mermaids-the-little-disney

Grace D. Gipson is an assistant professor of African American Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University where she teaches courses on theories and foundations in Africana Studies, Blackness in pop culture, and Black media narratives. Her research interests include Black pop culture, race and gender in comics, Afrofuturism, and digital humanities. Outside the classroom, you can find Grace collecting comic books and stamps on her international travel discoveries, ticket stubs to the latest movies, co-hosting the video podcast "Conversations with Beloved and Kindred," contributing her personal and professional thoughts on pop culture via blackfuturefeminist.com and giving back to the community through a myriad of projects and organizations. You can also follow her on Twitter @GBreezy20 and Instagram @lovejones20.

Bethan Jones is a Research Associate at the University of York. She has written extensively about anti-fandom, media tourism and participatory cultures, and is co-editor of Crowdfunding the Future: Media Industries, Ethics, and Digital Society (Peter Lang) and the forthcoming Participatory Culture Wars: Controversy, Conflict, and Complicity in Fandom (under contract with University of Iowa Press). Bethan is on the board of the Fan Studies Network, co-chair of the SCMS Fan and Audience Studies Scholarly Interest Group and one of the incoming editorial team for the journal Popular Communication.

December 19, 2022

Tumblr, TikTok, Dead Memes, and ‘Me’: Finding Yourself in the Niche-fied Internet

Recently, while I was making my way through Kaitlyn Tiffany’s wonderful book Everything I Need I Get from You: How Fangirls Created the Internet as We Know It (2022), I came across the title “meme librarian” describing Amanda Brennan, and I knew I had to chat with her!

Amanda’s decade-long career as an internet librarian spans across different platforms and materials ranging from memes to trends at large. I spoke to her to learn about how she understands and struggles with internet culture. In our interview, Amanda highlights the internet as a place for creative niches and fandoms where people can explore and make sense of their identity, with Tumblr being the quintessential place for that type of engagement. We also discuss the difference between “memes” and “trends” in Amanda’s work, how she organizes and categorizes internet culture to forecast trends, and whether trends ever really die.

Since we live in an era where the internet is “nichefied” – dominated by platforms that try to monopolize audiences with increasingly narrow parameters my conversation with Amanda has left me thinking about a loss of agency in the ways we now use the internet. I identified a difference between the experience of exploring internet niches that we both seemed nostalgic for in the “old internet” versus the algorithmically personalized corners we find ourselves on while using TikTok or other platforms today. Amanda described exploring websites, creating fan art, and learning new perspectives as key parts of identity formation online. Today this practice of exploration is exemplified through TikTok, where a user finds themselves in a “corner” determined by the algorithm that is difficult to move away from. This can make the experience of identity exploration more challenging, or sadly, less self-directed.

Whether we are working at the intersection of technology and popular culture, researching it, or roaming the internet to try to figure out our own identity, Amanda reminds us of the importance of being aware of our positionality that determines the lenses through which we interact with the internet.

So, I get the impression that you like the internet. Can you tell me what you like about it?

I've been doing this for so long that things I like have changed. It’s a lot more nuanced now, where some of the things I like are double-edged. For example, I like the ability for people to connect based on the things that are parts of their identity that they may not always be able to find people in their physical space to share those things with. Which, going back to the double-edged sword, sometimes people connect over things that are… not great.

I think the hard bit is that, for the most part, the internet allows people to explore their identity and vulnerability in new and novel ways that continue to evolve and just exploring identity and exploring what it means to be the self.

Is there a particular way that you have gone through this process? Or, are there specific communities online that you think helped in the process of exploring identity?

Oh, yeah. For sure! I started my Internet journey like, in the walled gardens of AOL chat rooms and I was in fandom from the beginning, when I was 12 years old and obsessed with Hanson. This may seem embarrassing now, it’s messy. But, realizing that I could find a space of people who think similarly but would challenge me to think differently at the same time. When you’re in a fandom, there is this one thing that you all like, but you all bring different lenses to it. This way, you can see how different people approach that same thing. It’s like this crystal that I have at my desk at home that looks completely different each way you hold it. If you hold it one way, you’ll see rainbows, and if you hold it a different way, you can see a pattern of squares in it. I love being able to take a thing and think “what are the lenses that I’m bringing into this?” But also, if I’m talking to a coworker, the lenses they bring into it allow me to see it differently and better understand it as a whole.

I love that about fandom. It’s a place where people connect over things they know and love, but then it also becomes a space to learn new things, to push your bounds, and maybe do some very creative stuff together as well.

Yeah, and it’s not always like that. But, transformative fandom specifically does that. I think that’s why I’m so drawn to Tumblr. The types of fans that are drawn to Tumblr where you can be creative and you can question ‘the canon’ and really dig into the reasons of why you are participating in this thing. I love that. I love overanalyzing.

What are your favorite platforms, or the platforms that you use everyday? And, I know these two do not necessarily overlap and are not always the same thing.

They are not! Yeah, Tumblr is one of my favorite platforms, but I don't use it everyday, which is a perfect example of that because I definitely go through cycles where I want to be in it, or when I pick up a new fandom. For example, I just got into the Locked Tomb series. So, I’ve been obsessed with looking at Tumblr series and fanart and explorations of those characters, but that happens when I feel like I have all the time in the world and I just want to focus on the things that I love.

The platforms I use everyday are in a flux right now. It used to be Twitter, but, with everything going on [referring to the changes ensued after Elon Musk purchased the platform] I’ve been using Twitter less and less. I feel like I don’t know where my internet home is right now. I use Instagram but mostly just for messaging and inspiration. I use it everyday but I don’t love it.

I do not use TikTok, although I think I need to for my job and for what I do. But, I have a lot of moral complications with it because TikTok wants to put you in an algorithmic niche to better serve ads against you. What happens is you’re being taught that an algorithm is seeing you, and you’re like “Oh, I love being on the side of TikTok!” But I don't know if I want an algorithm to try to put me in a box. The reason I like Tumblr is because there is that magic serendipity where you get what you get when you log in. To be really cliché about it, it is like going to a library and walking through the stacks, as opposed to going to Amazon and looking at your recommendation list and consuming what an algorithm thinks you are. From working in internet culture for so long, I have a lot of strong opinions about algorithms and I try to be cautious of where I’m letting algorithms consume me.

My sense is that this is becoming increasingly difficult with the platforms that are popular right now, right? At the same time, as someone who researches the internet, TikTok feels like a must. It’s not that I don’t enjoy it, I do. But I feel like I have to be on it to know what is going on there. Then, of course, I end up knowing only about trends that are in my “algorithmic corner” that maybe other people don’t know about or aren’t exposed to at all. This limits my ability to use TikTok trends as a means of connecting with friends or students because they’re not in the same corners of it.

I explicitly use TikTok on burners. When I think of using the internet as myself versus using the internet as my work persona or work concept, I’ve got several burner accounts depending on what corner of TikTok I’m trying to be in. The other day I even realized some people have been sending me messages on TikTok and I will just never see those. When most people think about TikTok, they’re usually thinking “this app knows me so well!” and, going back to what I said earlier about identity and the self, this makes me ask: how much of the self is chosen and how much of the self is assumed by an algorithm at this point and at what point does it become a self-fullfilling prophecy that, for example, all bisexuals love Phoebe Bridgers or something like that.

“My Spotify Wrapped Outed Me” - Video by @jakeblennings on TikTok

A lot of the work I do is also based around archetypes and stereotypes and how we lean into more comforting generalizations to find our identity. I think there’s something to be said about how in the last five to seven years people increasingly want to be seen and quantified. An example of this is the rise of astrology memes. You want to be put into a bucket where you can always have something that you can look at and say “Yes! I don’t know how, but this signs as sandwiches meme is right, I am a Taurus, and I identify with the peanut butter and jelly sandwich.” It’s such a stretch of the brain. But I think over the last decade or so we’ve been trained to look for a group of things and find our archetype within them.

the signs as sandiwches image by @thezodiacstea on Instagram

I feel like, on one hand, people have started trusting the algorithm so much now, so if TikTok feeds us videos about ADHD, we think we must also have ADHD, and we forget that the algorithm is not a doctor. But people believe it and trust it so much, so when it puts them in that corner they begin to question ourselves. On the other hand, I think even when the algorithm messes up, people find it funny and almost endearing. So, if someone finds themselves on some side of TikTok that they did not expect to be on, then they’re like “oh that’s so funny LOL.” rather than questioning it and worrying about what it looks like for other people and all the echo chambers and misinformation that it’s helping spread.

People feel honored to be put somewhere, like “wow I’m in ? You must think I’m so cool!” There is this trust in the algorithm but the algorithm was built mostly by a bunch of dudes who don’t understand fandoms and don’t understand communities in the same way that a teenage girl would. That’s something that’s always on my mind: that people who built the algorithms built them in their own lenses. We each bring our own lenses to the table, and that’s not a moral failing, it’s just who you are. So, what does it mean when a bunch of Gen Z kids are defining who they are based on some algorithm that a 40 year old man built and doesn’t maintain like a garden. They just build it and let it be.

Yeah, that assumption that algorithms are a neutral code language, rather than a specific way of seeing things and a way of building things. As someone who works in that space, do you see this changing at all? Or do we still have a long way to go?

I feel like Gen Z has a really interesting perspective on algorithms, that they see it a little bit as a necessary evil. But we are at a weird place right now where millennials are not quite in the decision making process of all this stuff yet, and it’s still run by the generation above. When it comes to change, I think it’s a question of: will capitalism win? Or will search for identity win? Because, at the end of the day, the algorithm serves capitalism, it’s not for people. It’s made to serve ads better and as Gen Z is so hyper-aware of how they’re being advertised to constantly, I think there’s potential there to change that, but we are a ways off.

Going back to a happier place, I get the sense that Tumblr represents the old internet, and I wanted to ask you: do we over romanticize the old internet? Or are there things about it that we should try to carry over or bring back and maintain?

There are three or four things that come to mind. The first one that sparked in my brain is: not being online all the time is important for everyone, and especially important for people who are chronically online, to remind themselves that the whole world is not on Twitter. I say this as someone who is chronically online and needs to be reminded of that a lot. As Twitter has been burning down, I am realizing that there are people in this world who don’t care at all or don’t know that this is happening, and they are living happy lives. That’s my own journey of finding what part of my life is IRL and what part of my life is online, and what the venn diagram of where they cross each other.

I also really miss when it was just websites because I could go to a website. Now, I have to download an app and do about six steps and sign up for the loyalty program and buy an in-app purchase. I miss the freedom of someone’s shitty Geocities page about how much they love their cat and the ability to not have to be on every app. I follow this witch shop based in Philadelphia called The 8th House, and I love everything she makes. I think she’s really cool and smart. She always makes these reels about how running social media content to promote her business is also a job. That’s how she can get new customers. But I met her at the Trenton Punk Rock Flea Market in Jersey, and had a great interaction with her and I was like “You know what? I am going to stan you forever!” This makes me think about my partner, who does art as well, and has to put up with all of the actions in social media in order to get their art out there. It makes me think “How did people do this before apps?” There had to have been a way because we have a history of art. I think Patreon is one great way to find art and support artists and them. I do a lot of Patreons as a way to say “You don’t have to be on every app. I see you, I like what you make, and I’m going to support you.”

Also: Serendipity. The ability to just look at something. I love going to museums. I recently went to see Nick Cave–the artist, not the singer–at the Guggenheim, and I didn’t look at any information online, I just went. I remember walking into the room and having this experience where I was taking it all in and feeling like “woah!” It felt very special in a way that I hadn’t felt in a while. I find art online constantly. I’m always looking for art inspo and tattoo art or the silly four-panel comics. But this is the type of experience that I can’t stop thinking about.

There was that element of discovery and exploration. Now, we have so many steps before. Even if I want to do something like watch a movie, I will probably look up a list of the most popular movies from this year, then watch some of their trailers, and at that point, I might be too tired to even watch the movie. But, thinking back to maybe 10-15 years ago, I would watch any movie just because a friend told me I have to watch it. Then I’m on this ride, and who knows what’s going to happen! There used to be an element of simultaneously having the option to be offline, but also when we were online, we had a chance to be completely enmeshed in whatever we were doing rather than being on 10+ apps simultaneously with the phone buzzing next to us and the email tab constantly open.

Oh, yeah. I have no attention span anymore. And it’s something I’m working on. Whenever I have to sit and write a document, I need to put everything on Do Not Disturb and try not to open Twitter in another window.

Diving a little deeper into your work, I saw that you are doing some work around trends at XX Artists. I want to hear more about that. Is there a particular way that you define a trend? Do you predict trends?

I would define a trend as a concept plus a constraint. That is the highest level kind of approach to it. But I also feel like the word “trend” has lost its meaning now, which is a little silly because it is my specialty. But, the way that Tiktok works has changed the approach to trends, specifically audio trends. When you have to do this specific audio with this specific lip sync or this specific dance, those are memes, not necessarily trends. When I talk about trends, about concept plus constraint, that allows for the ability to think about things like how we celebrate celebrity birthdays. I’m thinking here about KPop fandom and all of the goings on that go into an idol’s birthday. I think of trends with which we celebrate different holidays like, Mariah Carey defrosting on November first. That is a specific trend. The ways that very colorful tinsel trees are happening right now because people are desperate to find joy, to reinvent right now.

View this post on InstagramA post shared by Mariah Carey (@mariahcarey)

Part of the reason I wanted to be at an agency rather than a platform is because I wanted to be able to take in all the input from across the internet. I wanted to be able to see how people are approaching something on one platform versus another and a third one, and what ties all these things together. I work a lot with the idea of macro trends. We identify for example, that XYZ is happening on these platforms, but the underlying meaning behind it all is this little nugget of something. I work with a really great team across the organization and I like to coach everyone to approach the internet with the idea that we all have our own personal internet, and how we can help each other understand the larger concepts at play in internet culture by sharing the things that we are seeing. This is because I also believe monoculture is over. There are things that will tap into a whole different bunch of cultures but I think you and I can exist on the internet in very different worlds and have very small overlap. We have a lot of people in their early twenties who work at the agency so I coach them on identifying internet trends to understand how to make the connections between what’s happening in different places and stretch their mind a little bit, to get them thinking “why do I want to share this thing?” I think back to last year when everyone was tweeting series of red flags with a caption like “when he lives in his parents’ basement.” I think of questions like “why is everyone using this time now to talk about this? Why does everyone want to talk about a red flag? And why are some of them so universal?” There’s no definitive answer for any of it. It is a thought exercise in what drives people to share and what makes certain concepts stand out? What makes something catch on? And what is the emotional drive behind why?

I am interested in hearing more from you about the difference you identify between a meme and a trend. Many scholars who research memes identify an urge or invitation to participate in sharing memes or creating your own iteration as part of what a meme is. From what I’m hearing, you’re seeing a difference between meme culture (like TikTok dances that when people see everyone doing one dance they feel like they have to do this dance now), versus a trend that touches on a social or cultural moment that resonates with people. How do we better differentiate between a meme and a trend?

When I think about macro trends, an example that comes to mind is the desire to put yourself into an aesthetic. That is a macro trend. It is trying to niche-ify yourself so much because that's like what all the businesses are doing and also like a way to find identity. Then the trends that pop up from that are like ‘cottagecore’ and ‘dark academia’ or all the ‘-cores’ we could say. Memes to me are more format-oriented. I consider the dance a meme because people would iterate on it. For example, the hot meme right now is the dance Wednesday does in an episode of the Netflix show and there are iterations of people doing it on their own, some people who are not goth are doing it. People have ways of making it their own personal expression. The macro trend that that leads up to is that people like doing whatever dance is the hot dance right now because it’s a low lift. If I see a dance and it’s a little weird, it’s still simple overall and you can join in very easily. It’s also difficult to siphon off my personal understanding from the words I have to use for my job. I would call that a meme, my work would call that a trend.

image by 🥀 𝐦𝐞𝐢𝐠𝐚 🥀 from instagram

I would also add that a word may start a little more niche, as it gains popularity it goes to the most common denominator. A meme, at the lowest common denominator, is a word with pictures on it, and some people have a hard time expanding out the idea past that. Another example is the word ‘Emo.’ Everyone has a different interpretation of that word depending on their age and how into weird music culture they are. To me, Emo means a very specific group of bands. To the average person, if you say Emo, it might mean My Chemical Romance and Fall Out Boy, but I wouldn’t consider those Emo. I would be thinking of bands like Rites of Spring and Penfold and all these bands no one has heard of because I’m in that niche bucket.

I want to talk more to you about how to organize memes so let me ask you this: What does a meme librarian do? What does your day to day job look like?

In my past job it was a lot more tactile. But in my role now, I read a lot of newsletters because, again, everyone has their own perspective and there are people whose perspectives I really trust at seeing what they’re seeing through the internet and how they’re interpreting it. Like Ryan Broderick of Garbage Day, Kelsey Weekman who’s at Buzzfeed, Kate Lindsay and Nick Catucci’s Embedded, Casey Lewis’ After School, Dirt, and many other newsletters. I also check people’s Twitter accounts, I have a list of people that I love to follow. I like to see what people are taking in and kind of be a sponge. I will look at the internet and see what connections people are making today, and where I can make the connections on top of that. I have a big macro-trend document where I organize my thoughts and I work with incredible people everyday who are sharing information and thoughts. It’s really all about trying to make connections. It’s less archiving than my old job was. I don’t think it’s necessary for every business or agency to have their own meme archive, unless they want to think about the memes directly about their brand or business. Know Your Meme is very good at what they do and they serve a specific purpose. What I really like to do is get people to look at what is popping up and think about what ties them together and find out what the thing that’s up and coming so we can find out what is going to be the next thing. How can we take these smaller conversations and know what it’s like to be in this community while also being ahead of the curve so we can impress the audience with knowledge. One of my not-official OKRs is someone responding to the account with the social media manager “Are you okay?” Showing up as a brand and getting an audience reaction that is like “Woah! This is my internet thing! How do you know about that, brand?!” That is a win to me. Some brands are better than others at this, and it also has a lot to do with the level of trust that is given to the social media manager. Not everything is well planned, and sometimes you need to jump in on a dumb thing on the internet. It might not drive clicks to your website but it shows that you are in community with your audience and speak their language. That is not a measurable metric per se. But it is important to show up and let people know that you know what they’re talking about, and that as a brand, I am not here to dominate the conversation. Rather, I am here to get you to connect with other people, and have the audience feel like they’re part of something.

Yeah, that they’re in on the joke, at least.

Yes, and I think a lot about how in the heyday of Doctor Who, some people would post on Tumblr saying “I’m thinking of watching Doctor Who. What episode should I start with?” And the Doctor Who Tumblr, rather than answering that person themselves, would reblog the post saying something like “We see that this person likes X, Y, and Z. If you also like X, Y, and Z, what episode would you recommend for this person to watch?” and facilitating the fandom without dominating it or deciding for it.

Thinking back reminds me of one of the challenges I bump up against in my own work which is tracing a meme or tracing a trend back to find out where it started or how it has evolved. Sounds like what you're doing is trying to keep track as things develop. But, if you have to go back and trace where something started, especially if it is across platforms, how do you facilitate that?

A lot of reverse image searching. I really love the date range tools on Google search. I studied a lot of linguistics when I was in college, and I learned that a word won’t come into your point of view unless it’s been used for a certain amount of time before it reaches you. I think about this with memes too. A meme could be used in a closed Facebook group or an instagram DM or a Discord. Things are happening in those communities that just aren't archivable or searchable. You can get as close as you can unless you've got someone who was there when the tones were written. But, I think that especially over the past few years I had to do some letting go because sometimes you are not going to find the original. But, you can find the amplifiers, and sometimes the amplifiers are the best way to understand what community brought this forth.

Is there a typical track or a trajectory of where a trend starts and how it moves or evolves? I think I was giving a talk on memes maybe five or more years ago, and, at that time, it seemed that many memes started on 4chan, moved to Reddit, then Instagram and Twitter almost simultaneously, then maybe Facebook. Do you think there is still a common “track” for memes?

I don't think there is as much anymore. I think TikTok really has a handle on it, but I don't think TikTok is where things start necessarily. People see something somewhere on the internet and then they bring it to TikTok. Then because of the algorithm and the way that a lot of other platforms favor video, there's a little bit of a perfect storm of TikTok as amplifier. For example, all of the -cores that “started” on TikTok in the past couple of years like cottagecore? Those were on Tumblr about five years before. Tastemakers that make content that plays algorithms are definitely in that track. But tastemakers can really be anything or anyone. It really depends on the niche and how niches bump up against each other. The past couple of years have had the least amount of standard process. I was talking to a friend recently about the Tumblr-blog-to-book trajectory. You could make a Tumblr and it would be dumb and then you would get a book deal and that would be the process. But I don’t know if there is that process anymore. Maybe Instagram-page-to-book-deal? But if you are on Instagram then you have to also be on TikTok or somewhere else to drive people to look at that thing. TikTok is also so video-based so I don’t know if any TikTok people are getting book deals. Maybe there’s TikTok-to-TV? I’m thinking of Charli D'Amelio, that was TikTok to Hulu, but that was not a story that is as easily replicable. TikTok is more focused on moments versus people. People like Charli D'Amelio and Khaby Lame, who is now a spokesperson for a fashion brand, are exceptions. You don’t hear as many stories like those on TikTok. Other ones that stand out are Cranberry Juice Guy, Corn Kid. These types of specific moments from a random person that go viral. TikTok’s viral videos now are also getting smaller. This goes back to niche-fying. Something that can go viral in a niche doesn’t have the same impact because there’s no monoculture to drive it. The people who do succeed are becoming more niche. One of my personal favorites on TikTok is the Pasta Queen. Her videos are incredible loops where she is making pasta in an incredible kitchen and is always wearing beautiful clothes. She has such a wholesome approach to recipe-making. She’s always saying things like “this is beautiful just like you are.” And she just released a cookbook now, she just got signed to CAA. I think not everyone is going to want to watch Pasta Queen and that’s okay, but for people who love pasta and like this affirmation-y content, her style is amazing and the book is incredible. It includes stories from her Italian family and it’s all really accessible too. So, there are people out there who are going to be accessible and will be an influencer for a specific group of people, but it’s not the same as it was five years ago or more. Then, everyone has seen a Charli D’Amelio video.

PastaQueen

One thing that continues to interest me is when a trend is based off of a “revived” meme. Recently, for example, I was listening to an ICYMI Podcast episode where they talked about a fake Martin Scorsese film that was completely made up by fans on Tumblr based on a meme from years ago that someone just decided recently to respond to. Have you heard about this? It makes me wonder if memes ever “die”? How do we know if a meme is dead?

Some die. I think Gen Z tells us when they’re dead. Like, when was the last time you heard someone say “Damn, Daniel!”? I don’t know. Does Gen Z still watch Charlie the Unicorn? I don't think they do. Then you have something like the Rickroll, which makes Rick Astley part of internet culture forever. I don’t think we can predict which memes stay in power and which won’t. If a tastemaker finds it and thinks “Wow! This is fun! I want to bring this back,” then there’s potential for anything to come back. Since the pandemic, we’ve had a revised relationship with “cringe” as an idea. More people are going to like stuff and continue to do stuff just because it resonates with them, and that includes the memes that they use. Look at Minions memes, for example. They’re cringe but some people use them just for the irony of it. Or afffirmations on Instagram, that meme style is one that has been around and iterated on repeatedly. In my brain, it is the great grandchild of the de-motivational poster from the early internet. It’s all about what lenses people are bringing in. That goes back to the beauty of Tumblr. You can have a long tail because Tumblr exists in this no-timestamp and no-algorithm space. If someone wants to resurrect a photo from years ago, they can, and no one will know that it’s from 5-10 years ago. It’s all about the absurdity of it all. It’s all about finding absurdity and finding joy amidst the actual absurdity of all of our lives.

Tolerance demotivational poster

It feels like this moment is a moment of absurdity. Cringe is weirdly enjoyable. The aesthetic is exaggerated and crass. This isn’t new to the internet, but it feels like this is the time to eat this stuff up. So, in the midst of all this absurdity in our lives and on our internet(s?), what is a message that you would like to share with the world?

Wow! I’d say: Think about what lenses you bring to the table and how they affect what you’re seeing. Self awareness is a good one!

Sulafa Zidani is a writer, speaker, and educator at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she is an Assistant Professor in Comparative Media Studies and Writing. She is a scholar of digital culture, and writes about global creative practices in online civic engagement. She is currently working on a book-length student on multilinguistic internet memes. She also serves as an editor on the board of Pop Junctions. You can learn more about her work at www.sulafazidani.com

Amanda Brennan is an internet librarian who has spent the past decade looking at the ways we talk about the things we love online. After graduating with her MLIS from Rutgers University, she began her career at Know Your Meme, then spent seven years at Tumblr. There, she spearheaded The Fandometrics, a ranking system of entertainment fandoms, which Paste Magazine asserted should be “given a permanent place in pop culture’s critical metrics tool belt.” In 2021, Amanda stepped into the role of Senior Director, Trends Social at XX Artists, an award-winning agency built on diversity and inclusion. She has spoken about internet history at conferences across the US, on topics ranging from Slender Man to cat videos, and has appeared in multiple documentaries as an authority on internet culture. She can be found in liminal spaces between New York City and New Jersey.

December 12, 2022

Games as Social Technology—A Syllabus

IMAGE 1: Welcome to COMM 260: Games as Social Technology

Teaching Games(Video) Game is a curious topic to teach. Despite its social and cultural significance, it is still a topic that gets an occasional “wow, this thing exists?” and a “wow, people are actually into doing this stuff?”, often followed by a “but it’s not real!” At times, you may catch a whiff of condescension in the awe. When you engage with popular culture enough, whether as an academic, a fan, or both, you get trained to its distinct note.

Game design is a curious topic to teach because this lingering prejudice can contribute to a unique classroom atmosphere; a sense of community. Many students are likely to have been drawn to the course by their pre-existing interest in games, with an eagerness that matches their fan expertise. They are likely to have observed and experienced first-hand many of the topics to be covered in class, although not necessarily with a critical or analytic approach. Research findings and concepts may resonate on a personal level, and discussions can be rich with examples. The class may grow to become a safe space to bond over shared passions, an environment that may not have been readily available to everyone. In fact, my first semester of teaching COMM 260: Games as Social Technology at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC)—which was also my first semester here—started with many “I was so happy to see a course on games!”’s and ended with a series of student presentations that truly felt like a celebration of learning and camaraderie that we have fostered together over the course of the past 15 weeks.

Of course, I have heard, although lucky to have not personally experienced it (*yet—fingers crossed), that some students may approach a game studies class with a hostile counterproductivity that champions only their gamer or game player identity, especially if it is taught by someone who does not fit the dominant “gamer” image (i.e., typically heterosexual, cisgender male, and young, and depending on the cultural context also White, Western, and English-speaking). This challenge is relevant to a mythical thinking that an expression that I casually used in the previous paragraph can espouse: (a sense of) “community”. While the concept does not innately assume uniformity among its members, the notion of membership can limit one’s imagination, at times to a composite of similar self-portraits, entitled “the gaming culture”. In reality, there are numerous people who play games that do not perfectly fit this profile, including myself. In fact, a more accurate title for such a composite picture would be “a gaming culture”. The core of the challenge then, in a somewhat circular manner, becomes how to encourage, if not benefit from, a sense of community around games while embracing gaming communities and cultures, including those associated with non-gamers and non-game players.

This was what I understood as the foundation of Games as Social Technology(*) and my main objective. The course overview and learning objectives are as follows:

Course Overview:

This course approaches games as networked and collaborative technologies. This semester, we will focus on how games, gaming practices, and gaming cultures communicate values. As social technologies, games can facilitate community building, interaction, and development. However, not everyone is (feels) invited. We will closely study how their structural, representational, and cultural components are sites of dynamic meaning negotiations. Games have a social impact.

Student Learning Objectives:

Understand how video games have shaped culture (and how culture has shaped games)

Explain why certain video games and gaming trends have been so controversial

Interrogate video game structure, narratives, and their representations

Analyze the implications of video games as cultural commodities and as political technologies

Assess the impact that video games have on audiences and culture

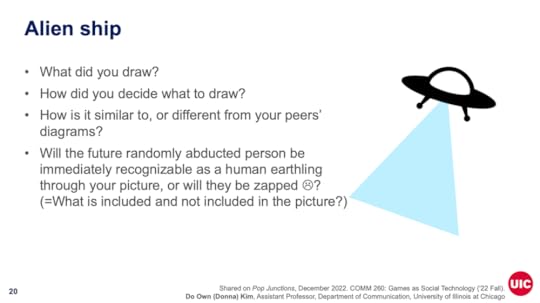

IMAGE 2: Sample In-class Exercise “Alien Ship.” (two slides). This exercise invites students to think about standards in technology design and diverse parties that may be involved in this process. Politics, biases, and consequences and be discussed.

AssignmentsI am a big believer in scaffolding when it comes to assignments. Weekly journals were designed to doubly yield an annotated bibliography and a pseudo gameplay log (Consalvo & Dutton, 2006; see course schedule for full reference) or ethnographic fieldnotes for the student’s final project. Reflection essays and documentary notes were designed to provide sufficient time and space for students to deeply reflect on, personally experience, and/or think through (with aid of media) practices and discourses that are relevant to the flow of the course. When needed, prompts for weekly journals additionally helped with this process. The midterm exam functioned as a checkpoint before progressing into more discussion-heavy topics. As the focus was on learning, the students were given the option to review up to four questions for partial points; it was to include a) why they got confused, b) why the correct answer is correct, and c) an illustrative, narrativized example that demonstrates their understanding of the concept. For their final project, students could choose from one of two options: 1) a creative project (designing a choice-based dating simulator) and 2) a critical gaming analysis. An in-class group exercise around Week 5 introduced the students to the first final project option and allowed them to start exploring it. The gameplay logs from their weekly journals were to be used as the data for those pursuing the second final project option.

(1) Weekly Journal

Except on the days with a designated prompt, you can have up to two (2) freebies. This is designed so that it will help you keep up with class discussions and prepare for the final project.

1. Reading Note

a. You are expected to have come read the assigned readings before coming to each class. From the readings you read for the week, pick one (1) academic reading (journal article or book chapter) that you found interesting and include in your Weekly Journal as your Reading Note. Please follow the format below.

Bibliography: APA recommended

Takeaways: Key summary points or takeaways based on the reading. No more than 3 sentences.

Application/Thoughts: Discuss your reflections on the concept and/or apply to an example(s) and discuss. You may draw on class discussions, make connections to your gameplay log, or discuss its relevance to your final project. Putting readings in conversations with each other is also encouraged. Quality over quantity—e.g., should not exceed a paragraph; aim for insightful 2-3 sentences.

[Optional] Key quotes: Put in quotation marks and include page number(s).

2. Gameplay Log

Play your game of choice* for at least 30 minutes every week. You may exceed 30 minutes, and this does not need to be in one sitting. (*on some weeks, there may be a designated game.)

Answer if there are any journal prompts.

Write down 1) game name, 2) when you played and your total playtime, and 3) three (3) bullet points of your play experience/observations. Include details, also bullet pointed. For example, don’t just write “It was good.” What do you mean by “good” and what made you feel that way? Was it because of certain features, the way you played it, or any other external circumstances? Make sure to screen cap or memo if something interesting happened or there is something you think you might want to refer to later. See formatting example below:

Game Name: write name of the game

Playtime: XX hour XX minutes

Aug 22 Mon 12:30-1:15 pm (45 minutes)

Aug 23 Wed 10:00-11:00 pm (1 hour)

(add as needed)

Notes:

Your play experience #1 (repeat for play experience #2 and #3)

Supporting details such as a relevant feature, your thought/feeling, a reason, relevant information

Supporting detail

Supporting detail

(2) Reflection Essay x2

These will be short essays (~2pages). The first will be on your personal relationship to games and the second will be on your social play experience of playing either Among Us or Pokémon Go with your classmates. Instructions will be provided.

(3) Documentary Notes x2

There will be two at-home screening days. Links will be available on Blackboard. After watching each documentary, you will upload a list of timestamped quotes and quick impressions from the documentary. Instructions will be provided.

(4) Midterm Exam

Some people feel more comfortable with taking an exam, others with writing papers. Your midterm will be a take-home Blackboard exam. We will go over the format in class before the exam.

(5) Final Project: Final Presentation + Final Paper

For your final project, you will give a short final presentation and submit a final paper (~5 page without references, tables, images, etc). You will have two options. Option 1 will be a creative project. You will develop one of the class exercises we will do during the semester (designing a choice-based dating simulator) and write about your experience, thought process, etc. Option 2 will be a critical game analysis. You will refer to your weekly gameplay logs and critically analyze the game(s) that you played during the semester. In both cases, you will be required to discuss your positionality and integrate course materials and discussions. Instructions will be provided.

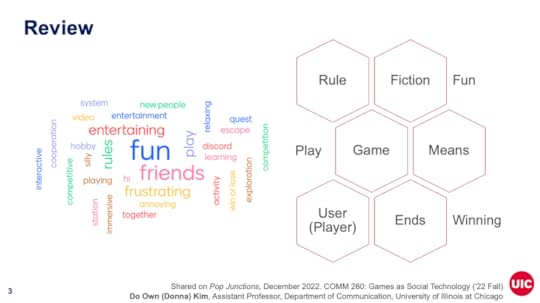

Image 3. A Sample “In the Previous Class” Review Slide . I have befriended continuity, repetition, and gradual build-up in my lecture organization as well. At the beginning of each class, I briefly review some key concepts and/or discussion points from the previous class. I use this time to stress important ideas and help students immerse themselves back into the course narrative, even if they could not attend a few times. This also helps me remind myself of my progress and easily connect together lectures delivered on different days. The left-side image is a Mentimeter word cloud on “game” from the first day.

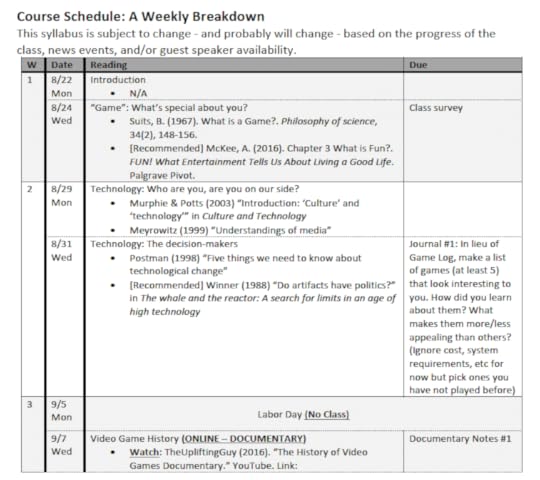

Course Schedule: A Weekly BreakdownThe narrative of my syllabus, also represented by the respective section titles, can be put as: “we can/should talk about games…by studying these things…for these things”. Classroom is where theory can be practiced. This semester, I paid additional attention to two diversity and inclusivity goals—or, goals for better science—while finalizing the course materials: 1) actively discuss and embrace, if not center, casual games and casual gameplay, as opposed to reproducing the overconcentration on stereotypically “hardcore” games and playstyles; 2) incorporate works on non-English, non-Western cases and by traditionally underrepresented authors throughout the semester, not only on “global” or “diversity” weeks. My training and background both helped me and limited me. The syllabus will continue to be a work in progress. This is one of the reasons why I decided to share it: let’s talk, let’s work together.

The course schedule is as follows. Please note that the original schedule has been reformatted from a table-based version to the current text-only version. Additionally, there are materials that I did not assign as reading to prevent overburdening the students but introduced in class that my students loved, such as Nick Bowman and colleagues’ 2022 work(**) on online discourses around Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 that discusses eudaimonic media effects. One of my students seemed to be particularly fascinated by the notion of “proactive stickiness” from Jen-Her Wu and colleagues’ 2010 article(***) on the Uses and Gratification theory and online games that we discussed in class.

The course schedule was prefaced with the following statement: “This syllabus is subject to change—and probably will change—based on the progress of the class, news events, and/or guest speaker availability.” It did change. I drafted the map, but my students and I navigated together. Based on what I observed during the semester and from student presentations, I am happy to announce that we have progressed and arrived.

Week 1

8/22 Mon: Introduction

N/A

8/24 Wed: “Game”: What’s special about you?

Suits, B. (1967). What is a Game?. Philosophy of science, 34(2), 148-156. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/288138

[Recommended] McKee, A. (2016). Chapter 3 What is Fun?. FUN!: What Entertainment Tells Us About Living a Good Life. Palgrave Pivot.

Due: Beginning of the semester class survey

Week 2

8/29 Mon: Technology: Who are you, are you on our side?

Murphie, A., & Potts, J. (2003). Introduction:‘Culture’and ‘Technology’. In Culture and Technology (pp. 1-10). Palgrave, London.

Meyrowitz, J. (1999). Understandings of media. ETC: a review of general semantics, 56(1), 44-52. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42579860