Henry Jenkins's Blog, page 14

May 23, 2022

Feeding the Civic Imagination (Part Two): Digital Media and Food

Brienna Fleming and Ioana Misc

What is your project about?

Brie: My project looks at the ways a popular YouTube cooking show, Binging with Babish, helps foster a digital food literacy, but this show is just one example of the myriad ways we can examine the growing genre of YouTube cooking channels and shows as a collection of recipes or as a digital cookbook. In English Studies, and in my field of Rhetoric and Composition, it’s becoming commonplace to foreground social justice issues through the texts we read and the papers we have students compose, and food discourse is being used more than ever to present the histories of marginalized people. Take Steven Alvarez’s course, on what he calls “Taco Literacy.” In his 2017 Composition Studies article, Alvarez discusses how he uses this Mexican heritage food can help unveil the Mexican immigration experience, racism, appropriation, and appreciation of Mexican culture and foodways. Food Studies, a discipline unto itself, asks us to consider the ways foodways are related to people and history, to intimate and personal facets of life, race and sexuality, religion, and the place we call home. In addition to the integration of popular food and culture into the composition classroom, we’re seeing an increasing need for multiliteracies, specifically a digital one. Most people in and outside academe embody a basic digital literacy, if it only emerged through social media use. So what does Binging with Babish, food, and digital literacy have to do with the civic imagination?

“If Looks Could Kale” Burger Inspired by Bob’s Burgers https://www.bingingwithbabish.com/#top

If the heart of civic imagination is to allow for the presence of an alternative, then I see a digital food literacy as a current, emerging literacy that can help audiences experience food through a perspective that’s not their own. Just as taco literacy invites students to study Mexican history and heritage, so too can we assume that people learn from engaging with digital (social media) content. In a highly polarized pandemic world, it’s easy to come up against perspectives that mirror our own, so to be a just, informed person we must be reminded to look beyond the scope of what we’re comfortable with. This matters in the real world and in higher education. Scholars still have much to do in regards to the uncovering and integration of marginalized histories and voices, as well as the sources from which these things come. Digital texts, especially those stemming from social media or personal profiles, challenge the use of traditional, print-based texts. And the food-based content they contain can be used as a teaching tool offering the users/audience an understanding of the relationship between food and personhood.

Ioana: I couldn’t agree more with your final claim that “scholars still have much to do in regards to the uncovering and integration of marginalized histories and voices, as well as the sources from which these things come.” This is valid for artists or technologists too.

While advocating for the expansion of inclusive and collaborative methodologies, my current research explores the mechanism in which gastronomy can be intertwined meaningfully with other “disciplines” (artistic, scientific, spiritual, technological) in order to awaken our imaginative senses: civic, social, creative.

An exquisite example can be found in teamLab Borderless, a highly advanced digital interactive museum in Tokyo, Japan. Among many pioneering installations, En Tea House, in particular, stood out to me for combining the sacred tea ritual with a responsive video mapping technique into a holistic journey that enchants multi-layered forms of imagination. As the teacup was emptied by each visitor, the responsive video mapping juxtaposed a choreography of flower petals that adjusts its intensity in a proportionate manner. This journey activated a sensorial tech-culinary path and a sensorial imagination. I used to call it “immersive food” as it was at the crossroads between carefully curated nutritive ingredients and highly advanced digital extensions. You are not only accessing the specific food or drink, but rather the poetic story of it. You step out from material reality in order to enter into an augmented world. The artists signing the installation teleport you into a dimension that blends food and art seamlessly. Where does food end and where does art begin? We seem to assist to the emergence of a new “species” that I tend to call food-tainment, previously nicknamed by the media as “eatertainment”.

Still from teamlab Borderless, En Tea House, Tokyo, Japan

The roots of these hybrid experiences can be found in a different movement called culinary cinema, however in that realm food was the extension of cinema, while in this case food is extended by interactive cinema. In the current evolutive context, the question I am asking is: can we perceive immersive food as an elevated form of imagination or as a form of trading our own imagination for an external authored visual experience? How can we relate to food as art or to art as food? Under what circumstances the convergence of the two could bring added value to our human experiences? Is the culinary experience intensified or rather it decreases its importance, while joined by interactive mechanics? On a personal level, I felt elevated by the experience. It seemed an intersectionality of history (tea rituals preserved from the ancient times) and futurism (interactive and responsive tech that enchants and surprises). It clearly remained a memorable experience, most probably taking into account also the novelty factor.

Another intriguing example can be found in high end experimental restaurants such as The Alchemist, based in Copenhagen, Denmark, which claims to propose to its visitors elevated forms of “holistic cuisine”. The founders even launched in 2018 an expanded manifesto in this regard.

Still from The Alchemist Facebook page, Copenhagen, Denmark

Quoting one of the lead initiators, Danish Chef Rasmus Munk, the experiences “stimulate and interact with all five senses and the intellect by exploring elements from theatre, art, science and technology”.

Although the level of innovation is high, the level of accessibility is low, as the restaurant’s rates often exceed ordinary incomes. Still, the process is revealing, encouraging us to look at food from another angle and this process alone can be replicated by anyone in the world with basic means. Munk adds a dimension that I find evocative, claiming that “the fundamental recipe of the restaurant menu has changed very little in the last 100 years - it basically works according to the same script everythere. When I started investigating how theatre can enrich gastronomy, it dawned on me how similar the dramaturgy of a restaurant meal is to that of the theatre.” Taking this idea further, we may as well ask: how can storytelling structures of theatre/cinema/VR change when inspired by food rituals?

Other restaurants such as RAW from Taipei, Taiwan, led by chef Andre Chiang aimed to create experiences blending food and virtual reality, while adding most recently to the menu a rarity of our days: “edible NFTs”. For them, the kitchen itself is “a place for creativity, a place to dream. Dream to be brave [...] If this is a dream, please don’t wake me up.” (George Calombaris).

The team launched eight NFTs, each inspired by a food principle curated by Chiang: Unique, Pure, Texture, Memory, Salt, South, Artisan, Terroir. These tags alone are a booster for civic imagination. The collectors of the NFTs would be then invited to join a private dinner. This process involving high end gastronomy, technology and sustainability is a proposing not only a new take on enjoying event-dishes, but also a new take on community formation. The idea of encouraging collective dinners for passionate strangers with similar interests may lead to creative conversations and bonds.

NFT Collectors invited at RAW, https://www.tatlerasia.com/dining/journeys/nft-we-are-what-we-eat-2021-en

However, it is not just technology the one that may turn food rituals into spectacular shows. In countries like Peru, molecular gastronomy, a blend of culinary craft and chemistry is perceived close to a national brand, being found in almost all local restaurants.

All these combinatory practices of food, philosophy, chemistry, virtual reality, film or theatre seem to prototype a new aura of contemporary food, one that blends spectacular-ness, creativity and civic imagination. In short lines, the curated intersectionality of food and other fields of life involving arts, tech, sciences or spirituality can lead to more than a food ritual, to a one-of-a-kind experience that prologues our body, mind and spirit in unprecedented manners.

How does food inspire or stifle an inclusive imagination? How can we encourage ways to involve food in civic imagination and debates on justice?

Ioana: To my mind, food is inclusive by design, however its imaginative layers might vary heavily and the question is indeed - how to preserve those and how to debate them? How can we archive the philosophies or rituals of food? And how to do it in innovative manners? How to preserve more perspectives on the same food ritual at once?

I would recall an example where (fictionalized) food culture and virtual reality are combined into an unique installation. The Doghouse emerged as a VR experience directed by Danish VR artist Johan Knattrup Jensen and produced by Mads Damsbo. The installation was designed for five persons at a time, each with his/her own VR headset, however seating at the same impeccably arranged dinner table. The story portrayed a tense, Danish family dinner seen from more angles. Each explorer could choose a character and imply his/her perspective in order to reveal the story. In other words, the explorers are allowed to inhabit the perspective of the mother, the father or the children invited for dinner (one at a time). At the end of the experience, a dialogue between all participants invited them to negotiate the story that has happened by combining all of their individual angles into a narrative that would feel coherent. Methodologically, the project felt groundbreaking in 2015 when it was launched for capturing multiple perspectives on the very same topic: a troubled family dinner. I experienced it in Tel Aviv, during The Steamer Salon (a VR program) and back then I was affiliated with the role of the mother, rooted in the story as an alcoholic woman. In VR there were numerous toasts, while in reality as well there were corresponding glasses and this flow of dimensions (from real to digital, from digital to real) allowed me to inhabit the story more profoundly than any conventional VR piece. Not the food itself, but the objects surrounding food, the forks, glasses, knives became context markers or even characters narrating the story for us further. Traces of fiction in reality and traces of reality in fiction. To me, this project tapped into a highly important topic: decoding reality and its emotional, gastronomic, social aspects from multiple angles. Once we understand more perspectives, we come closer to a form of collective justice. And this is equally valid for civic imagination. Once we collect more perspectives, we may negotiate a more meaningful societal model.

The Doghouse VR installation still, courtesy of Makropol, the production team

How can we inspire our shared imagination as we prepare meals, serve dishes and eat what we made? How does food connect with our memories and aspirations?

Brie: All of this sounds so interesting! I’m drawn to one of the first things you write, “how can we preserve and debate” notions on the inclusiveness of food? In some ways, I think this idea bridges our ideas and research together, especially because in this moment we’re both talking about “artifical” food experiences (that is to say, digital and virtual). I also find it compelling that The Doghouse offers users a chance to experience a tense and fraught family dinner with a VR experience in that it offers people a chance to experience a role and a meal from a perspective that’s not their own. While I agree with you that food is inclusive and so telling of our familial rituals and heritage, I am also of the mindset that in the real world food plays a role in a social hierarchy that isn’t so inclusive (e.g. food deserts and insecurity at large).

To me, it’s impossible for food not to connect us with our past and our memories. The trouble is without our family food literacy being passed down, where might we gather information on foodways like or unlike our own? I first noticed that YouTube and all of its popular cooking channels could be used as teaching tools when I was watching an episode of Frank Pinello’s The Pizza Show about San Marzano tomatoes. In the 3:34 minute video, Pinello takes us to Italy to meet a bunch of canning nonna’s; “masters,” according to him. I soon realized short YouTube videos such as Binging with Babish or The Pizza Show would be innovative and approachable texts in the composition classroom: students can analyze visual rhetoric or they can learn something a little deeper about a can of tomatoes they see in the market. Listening to Pinello interview those old Italian women confirmed the notion that heritage foodways are dying. Perhaps this is true of our own, but either way I think we can start taking a closer look at the educational benefits of social media food content. And the interesting thing about the connectivity of social media is that even if our own food stories have gaps, we can turn towards social media and alternative cooking shows to learn something new.

Ioana: I love the way you highlight the educational benefits of social media food content and the way you emphasize the importance of digital archival especially when it comes to “saving” dishes or practices that are almost extinct. The web can be indeed seen as an expandable gastronomic library, although a very messy one. So one question for the future is how can we index food and food content in a meaningful manner? Can food be truly “indexed” in compelling manners or can it be solely experienced?

Danish chef Ramus Munk proposed a creative take on portraying food. In his gastronomic practice, he promotes what I call “painting mimicry”, depicting ingredients as comestible creative tools.

A gastronomic dish from The Alchemist restaurant, courtesy of The Alchemist Facebook page

While coming back to the core of the question, I believe food is in many ways a display of imagination in itself, similarly to a painting or sculpture. It is just then we don’t place it in a museum, but rather in spaces that we have tagged as conventional or “non-artistic” per se. To my mind, this angle on food shall invite us to rethink our spaces as well as holistic playgrounds.

How can the media and popular culture support food and civic imagination? What are the opportunities? What are the challenges? How to reckon with the history and heritage of the food we fuse?

Brie: Right now, I think there is an upsurge of social media food content and because cooking shows and the desire to learn about food history or follow recipes is increasing in visibility, so too are the dark undercurrents of racial and gendered issues. Whereas the Restaurant Opportunities Center (ROC) exists in the real world to protect the rights of food, hospitality, and agriculture workers in the United States, nothing like that exists to mitigate racial or gender problems in digital food-spaces. But, people are opening their eyes to inequity in online realms more and more. We see this with “mathematician and food antagonist” Joe Rosenthal’s Instagram handle who most recently is taking a swing at Bon Appetit’s chef star, Brad Leone, for spreading misinformation that could make his audience ill. Furthermore, this isn’t the first time Bon Appetit has come under fire; within the last couple of years, 14 former employees have accused the publication of a racist, sexist, and toxic work environment.

Ioana: Following this note, how could we make the ethics of food more transparent, rather than the aesthetics? This is perhaps a challenge that our century already deals with in direct and sometimes over-pressing manners.

Brie: Yes! That’s at the heart of what I’m getting at: making the ethics of food transparent. And while it’s interesting and helpful that social media, virtual, and digital spaces can continue to be used as teaching tools, with a closer examination we can also unveil the unequal power dynamics in the food industry, whether it’s “real life” or “online.”

What has the pandemic taught us about food and framing the imagination? What examples and approaches need to be documented at this moment in time?

Brie: I think that COVID sparked a lot of connections for people from online food-based social media communities. Arguably, many include a lot of women therefore such online communities are dubbed as feminist and are being analzued and writtin about more in higher education. I’m a member of a private Facebook group with more than 200 members dedicated to helping others “connect with others through baking”. It’s inclusive, too. It encourages failure and adaptation and acknowledges problems with availability or what some might have access to. On Instagram, there’s Christina Tosi’s group and hashtag “bakeclub” that’s been written about, too, and the group actually paused when Tosi was called out for being culturally insensitive during the summer of 2020 when the Black Lives Matter Movement took off and xcelerated. The pandemic leveled the ground, so to speak, making us confront inequity in the world. And that extends to food. Most recently, I’ve enjoyed Alexis Nikole aka “theblackforager” on Instagram. Her videos are short and sweet and pack an educational punch that doesn’t avoid the racist or colonial subjectivations of certain foods and native plants.

Ioana: I believe on one hand it reignated intricate food rituals, it replaced “fast food” with “slow food”, it turned food into a playground. I feel citizens have become what I call “play-zens”, people taking time to contemplate and rebalance life, to have a ludic look on topics that previously felt over-ordinary. However, on the other hand, it brought more automation and technologization in the food industry, which is not necessarily ideal in the long term. Back in 2017, IDFA DocLab displayed a project called Eat | Tech | Kitchen, where the creators designed a chatbot to develop recipes of the future, based on the input of the spectators. Emerging tech-restaurants started to program AI mechanics to assemble food bowls. Although the novelty factor is high for all these experimentations, I personally advocate for the importance of preserving and prioritizing human-crafted food.

How can we cook with civic imagination? What are the “recipes” that could guide us?

Ioana: I believe recipes could include not only comestible ingredients, but also expanded ingredients able to activate all of our senses. Music, visuals, the setting of a certain food are able to trigger more layers of civic imagination. Sometimes even an ordinary dish could become spectacular if placed in a creative context. I believe any recipe could potentially be a premise for civic imagination as long as the participants are open to expand on it creatively, socially, philosophically.

Brie: I love that you’re helping me to consider other elements of a meal that “activate our senses”, such as dinner music and the place-settings. It also has me thinking about the ways we can better understand food and class issues based on how other’s access food, prepare it, and set the table.

How do we want cooking practices to look like in the future?

Ioana: I believe cooking practices can be expanded ethically (by making sure we respect food sustainability and empower local producers), aesthetically (by combining cooking practices with artistic, technological practices) and spiritually (by taking the time to respect the rituals of cooking).

Brie: And I think some social media handles, like the blackforager (Alexis Nikole), for example, get right to the root of this in how she uses her platform to educate about local, Appalachian plants, their history, and how to safely and ethically harvest.

Are there any similarities and/or differences between your projects? What are some additional points that you think should be explored in the future?

Ioana: At a first glance, we both focus on expanding food culture and we both dive into digital media as a way of archival (Brie) or creative stimulus (myself). While Brie is focussing on including marginal voices into food culture, which is highly needed from my perspective, being what I call an “ethical expansion”, I tend to advocate for including (when fitted) more artistic, technological, spiritual practices into food culture, and this is perhaps more of a “sensorial or aesthetic expansion”. Overall, I feel our approaches combined form a holistic approach towards expanding food culture in more accessible, but also more creative and innovative manners. There are numerous questions launched in our dialogue that, if taken further, could perhaps prototype new food rituals and new food-centered educational playgrounds. So, among the leading questions I will take with me as a post-dialogue “food for thought” are - what would a school of ethical and aesthetic food culture look like? How can we expand food practices creatively and qualitatively, without altering the core? How can we decode food as a means to express imagination?

Brie: I think that Ioana articulates a conneciton between our research and ideas well. Food is sensory, and its creation (cooking) is an artistic process. The “chef” is valued and perceived as an artist and outside of what I’m looking at on YouTube and Instgram is a rich, digital world of documentaries and food-related series that are dedicated to carving out a “holistic approach towards expanding food culture in a more accessible, but creative manner.”

References:

Alvarez, Steven. “Taco Literacy: Public Advocacy and Mexican Food in the U.S. Nuevo South.” Composition Studies, vol. 45, no. 2, 2017, pp. 151–66, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26402788.

Beardsley, Ashley M. “‘You Are a Bright Light in These Crazy Times”: The Rhetorical Strategies of #BakeClub that Counter Pandemic Isolation and Systemic Racism. Popular Culture Studies Journal vol. 10, issue 1, 2022, pp. 219-236.

Fleitz, Elizabeth Jean. The Multimodal Kitchem: Cookbooks as Women;s Rhetorical Practice. 2009. Bowling Green State University, dissertation.

Harris, Margot, Palmer Haasch, and Rachel E. Greenspan. “A new podcast is exploring the reckoning that happened at Bon Appetit. Here’s how the publication ended up in how water, Insider, 9 Feb. 2021, https://www.insider.com/bon-apptit-ti....

Rae, A. (2020). Faq. Binging with Babish. https://www.bingingwithbabish.com/faqs.

Alchemist, Manifesto (2018), https://www.dropbox.com/s/jp4c4xzkoyel6t4/Holistic%20Cuisine%20Manifest.pdf?dl=0

Teamlab Borderless (2022), https://borderless.teamlab.art/

Eat | Tech| Kitchen (2017)https://www.idfa.nl/en/film/612ac86c-3a86-4f2f-bb72-a79f444898c6/eat-tech-kitchen

Calombaris, George, RAW website (2021) https://www.raw.com.tw/?fbclid=IwAR1RL8Esuz4uG61XRNb4YK_doiXbGPXHwjc9PB-8NUHQFJBXsqQPODexBfs

Brienna Fleming is a PhD candidate writing her prospectus and studying Rhetoric and Composition at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio. Before her PhD, she taught first-year writing and literature in eastern Oregon and Wyoming. She holds a BA in English-Literature with a minor in Women’s Studies from Penn State, and two Master’s of Arts (English-Literature and American Studies) from the University of Wyoming. Informed by feminist and queer theory, her research and writing focuses on foodways, social media, identity and communities, American literature, and the cowboy.

Ioana Mischie is a Romanian-born transmedia artist (screenwriter/director) and transmedia futurist, multi-awarded for film, VR and innovative concepts. Fulbright Grantee Alumna of USC School of Cinematic Arts (collaborating with the Civic Imagination Lab / Mixed Reality Lab / JoVRnalism / Worldbuilding Lab), and Alumna of UNATC, advanced the transmedia storytelling field as part of her doctoral study thesis completed with Summa Cum Laude. Her cinematic projects as writer/director have traveled to more than 250 festivals worldwide (Palm Springs ISFF, Hamptons IFF, Thessaloniki IFF), were developed in top-notch international programs (Berlinale Talents – Script Station, Sundance Workshop – Capalbio, Cannes International Screenwriters Pavilion) and awarded by innovation-driven platforms (The Webby Awards, F8, Golden Drum, SXSW Hackathon, Stereopsia, D&AD). She has created groundbreaking franchises such as Tangible Utopias or Government of Children, empowering children to see themselves as leaders and to redesign their society. Her most recent immersive experience, Human Violins received the first European Meta award thanks to Women in Immersive Technologies and the Immersive Creators Catalyst program. TEDxBoldandBrilliant speaker, member of Women in Film and Television LA, she teaches wholeheartedly at UNATC and UBB as a PhD lecturer. Co-Founder of Storyscapes, leading Noe-Fi Studios (a neuro-VR start-up) and Omniversity (educational VR). Envisioning the world as a neo-creative playground, she deeply believes that storytellers are “the architects of the future” (Buckminster Fuller).

May 18, 2022

Feeding the Civic Imagination (Part One): Intercultural Food

The Civic Imagination Project team spent a lot of time during the pandemic thinking about food (and making food) from our own pods and considering the ways that communities get forged, identities get defined, around what we eat and what food we share with others. Out of those discussions has come a special issue of the cultural studies journal, Lateral, focused on “Feeding the Civic Imagination” still in process and scheduled to release in the months ahead. To celebrate and extend the rich mix of formal academic essays there, we invited some of the would-be contributors to participate in a series of dialogues at the intersection of their research. I am going to share these rich and thoughtful conversations over the next three installments. These conversations were overseen by Do Own “Donna” Kim, who was recently award a doctorate in communication from the University of Southern California and accepted a job at the University of Illinois - Chicago. Sangita Shresthova, my longtime research collaborator, has also taken the lead here. The rest of the editorial team consists of Essence Wilson, Isabel Delano, Khaliah Reed, Becky Pham, Javier Rivera, Steven Proudfoot, Amanda Lee, Molly Frizzell, Paulina Lanz

Elaine Almeida and Lisa Silvestri

SILVESTRI: Hi Elaine! I am excited to talk food, justice, and civic culture with you! Maybe we could start with a little “definition of terms.” I roll my eyes at my own suggestion because it sounds very academic of me to say and perhaps indicates that I'm in the process of reading seminar papers..!

I guess it makes sense to start with what makes this conversation series unique: FOOD! For me, “food” is a medium of sorts. But I realize that it can also be artifact, ritual, and/or practice. How do you understand food?

ALMEIDA:

First, I have to say as an avid lover of food, what an honor it is to be able to study and be with it in our scholarship! I’ve come to thoroughly enjoy studying and thinking through food for many reasons— like you said, food can be a site of ritual and practice, and what’s more, food elicits deep ties to memory and our psychic lives. Food invokes memory through its visceral employment of the sensorium, creating neural pathways not just related to taste, but to texture, smell, sight and sound of food. So there’s something to be said about food’s role in building our memories and imaginaries of the world.

But more so, I think through food particularly through the lens of Rachel Slocum’s food justice, where she understands that food is a benign but charged site for construction of race and ethnic relations. Food is a cultural contact zone where we have the opportunity to not just experience another culture through sight and sound, but literally process it through our body—the food stays with us, is, for a moment, us. It is a site where one can really undertake an embodied understanding of the ways a people create, imbibe and nourish themselves through the world around them. It, however, often a site of othering; not ritual or practice, but the literal devourment of our imagined ideas of how others can make us more whole, more full. Instead of using food to understand and imagine others, food, and particularly “ethnic” food in the United States serves as a place where people can imagine more about themselves as cosmopolitan, “adventurous” subjects without ever having to make true connection with the purveyors and creators of their food. This is what Slocum means by food being a benign but charged space. If everytime we taste a meal it elicits a memory of us devouring the other, how do we imagine ethical, people-centered relationships to food, particularly for marginalized groups in America who are visually underrepresented, but are readily represented in the takeaway menus and trendy cafes?

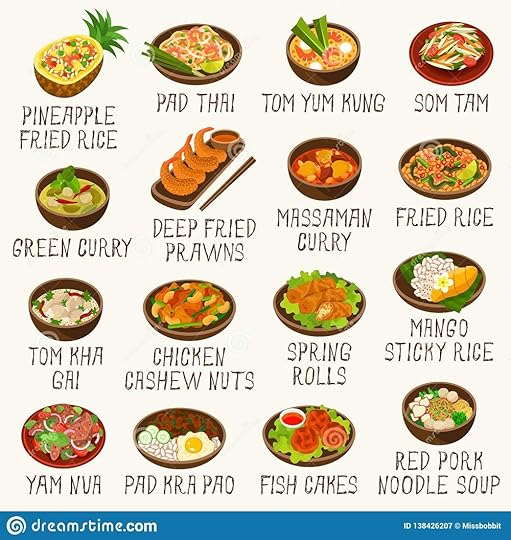

And you know, in my project (jeez sorry to ramble!) I take this question to examine how Thai Americans are represented in food journalism in our contemporary era. Thai food is a popular takeaway option and “fusion” food in the United States, but Thai Americans are a generally small minority group in the United States and are not often represented across various media— including, as I soon found out, even in journalism about Thai food. Articles about Thai recipes and restaurants were centered on how Thai food might attract American readers and never centered Thai Americans. Mark Padoongpat, author of Flavors of Empire: Food and the Making of Thai America, argues “Thai food acted primarily as a site for the construction of Thai Americans as an exotic racialized foriegn other through taste and other human senses besides sight.” And so again, and again, I come back to this idea of how can we imagine people-centered relationships to food that move from devouring to nourishing each other?

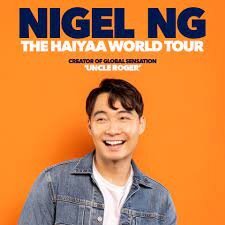

SILVESTRI: I like that- “from devouring to nourishing.” I also hear what you are saying about food being a “cultural contact zone” but also a potentially dangerous site for Othering. It’s that idea of a little knowledge has the potential to produce a lot of (wilful) ignorance. The work you describe reminds me a little of the comic, Nigel Ng and his podcast “Rice to Meet You” where among other things he problematizes (in a funny way) this kind of teflon cosmopolitanism you describe; Where a hunger for exotic/forieng/other is satiated through safe/controlled exposure but nothing actually *sticks* in a meaningful way.

ALMEIDA: No, totally, you exactly understand this difference between devourment and nourishment, this radical ability to create using our relationships and food as a vehicle!

SILVESTRI: I guess the food story I have for you is more about absence; the problem of not having food as a point of contact. If food is a useful point of entry (even if problematic), what about cultures with no shelf space in our pantry? How do they exist in our civic imagination?

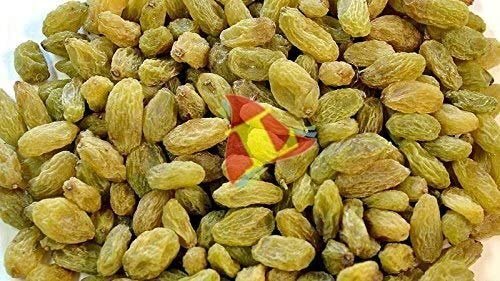

The case study I am working with involves a partnership between US Veterans and Afghan farmers. First, a little background: In the 1960s and 1970s, Afghanistan’s export of raisins accounted for 60 percent of the world market. So for a time you might think, “Ah Afghanistan, yes I’ve had their dried fruit.” But after decades of war in that country (first with the Soviet Invasion then with the U.S.), they have been cut off from global trade. Instead rhetorical associations with terrorism dominate American ideas about Afghanistan.

Case study research from 2004 includes an interview with a raisin trader named Mazar who said: “We don’t have any government and they don’t care about the raisin business. The custom and excise authorities are serious about their own benefits and are not serious about trade. They collect duty from us, and that’s all.” The farmer’s remarks speak to an inability to participate in and subsequent exclusion from the global community. To that I would add, without Afghanistan's identity represented through food commodities, it is much easier to ignore, forget, and Other the people of Afghanistan in the civic imaginary.

ALMEIDA: You know, when we talk about civic imagination so many examples are visual and auditory, and I think what both of our stories show is that a robust imagination, one that can really help us articulate alternative paths forward, needs to encompass numerous senses and be a full bodied imagining. Right? Because our stories seem to have opposite problems that are leading to the same absence—Afghan people are represented in mass media but not in intimate cultural spaces such as food and spices, while Thai food and spices are present throughout the US, but Thai people are missing from the public eye. With both, we have an unfinished idea of who either people group authentically are. To imagine ethical, caring relationships for public good, we have to imagine the robustness of life in unmediated ways. Food allows us to physically come in contact with items and artifacts meaningful to different ways of life. And isn’t the crux of this that part of the work of the civic imagination is to debate and work through narratives, hopes and fears, but again, both of our projects are centered on people groups who are both widely understood through only one narrative and lens.

For Thai Americans, the easy “so what” is representation, right? That people should know that Thai Americans are a robust ethnic group in the United States. But more than that, how can imagining Thai Americans and Thai people help us to understand the history and implications of US-Thai relationships—where Thai subjects/objects are always sites for others pleasure (be it the Thai tourism industry, sex industry or even again, Thai food,)— and actively create equitable, ethical relationships? And I wonder for you, what does access to Afghan food products help us to reach or reimagine? (Which wow, not a large question at all!)

SILVESTRI: Ha! That’s great- the bigger the questions, the better the conversation! I like what you said “food allows us to physically come in contact with items and artifacts meaningful to different ways of life.” That’s the heart of it. And the sensory nature of food- you are right- is paramount to its role in imagination. I am sure we all have a taste, smell, or texture that transports us in time and space, even back to our own childhood. But of course that transportation or I should say imagination hinges on familiarity. When the food or spice is unfamiliar- foreign- Other- it is more difficult to imagine.

The rest of the story about Afghanistan picks back up during the U.S. war in that country when a soldier who knew just a little Dari (the local language) worked with an Afghan saffron farmer to get his spice to market. The farmer’s request implied an interest in transporting his spice locally, but three Army Veterans had bigger ideas. Now, Rumi Spice as it is called, sources crocus flowers from local Afghan farms and employs hundreds of women in the cultural tradition of hand-harvesting the flowers’ delicate stigmas (the source of saffron). It’s so cool. And now- from the one farmer’s request–Rumi Spice sells Afghan saffron (and wild black cumin too) in American stores like Whole Foods and those Blue Apron boxes that people become obsessed with during the pandemic! How cool is that? I think the thing that blew me away when I learned this story is not only the imagination, but also the courage and faith it took to do something like this. It’s one thing to imagine but it is another to execute. Imagination, though, has to come first.

ALMEIDA: Yes! And I think what food helps us to add to our civic imagination is methods of imagining and transforming. A lot of the time, our imagination can be pretty ocularcentric—we need to “visualize” or “picture” the things we want. I fall into this trap a lot. And because we’ve started with “visualizing” and “picturing” solutions, we operate in a way to match: we fight for representation, to be seen, we fight for exposure, for visibility. And this is such a limited way to bring about justice. To be clear it is an important way, but not the only way. Because then we get caught upkeeping the artifact of the image we’ve created, and not on the processes of life. Joan Tronto, the care ethicist, reminds us that care is not simply a thing or a collection of things to uphold, but a continual collaborative practice we cultivate in ourselves and others to strengthen democracy.

And to circle back to my opening little thought, what food brings to care, imagination, justice is those methods of practice. If we’ll all indulge my craziness for a second, here’s a recipe for Khao mok gai, a Thai saffron chicken dish: https://hot-thai-kitchen.com/kao-mok-gai/

One, super delicious, but two, what do we see happening in this recipe? We understand that there are numerous pieces happening together, but at slightly different times, that will come together in the end to make the dish. The chicken has to marinate for at least two hours, and that is only after you’ve used a mortar and pestle to make the marinade. Meanwhile, for the dipping sauce, you just have to bring the ingredients together and blend, easy-peesy. The rice has to be sauteed on a high heat and then fluff over a low heat. It has to go through the different heats and from the wok to the pot to get to the fluffy tasty place it needs to be. And right, this isn’t the whole recipe, but what we see is that to come together to make this dish, one that brings comfort and nourishment, numerous rates and style of change need to take place all dependent on not only the ingredients, but how each product simmers, or marinates or cooks into our new dish.

And notably, while I use this food example, I want to be super mindful about multicultural examples that have used food—the “melting pot” or the “stew” or “salad bar” of America. While those food examples were useful for promoting a specific style of colorblind multiculturalism in the US, that’s not what I am interested in. This Thai saffron chicken dish is coming out yellow; the rice, chicken and spices are all being transformed before us, not just made visible next to each other.

And cooking takes time. It is something we have to do more or less everyday to sustain our bodies, unless someone else does it for us, and then their labor has helped alleviate mine. There are questions of sourcing and presentation and all of these things are directly applicable to how social change takes place on micro and macro scales. We always talk about how “sweet” things can be, but how can we imagine how savory and spicy justice will be on our tongues? For me, this is the exciting potential of food and why our communication and stories about food are not just trivial fluff pieces, but really cue us in on processes of change.

SILVESTRI: You are so fun to talk to. I love how you engage metaphors to guide your thinking (and I’m thankful for the recipe!). I had the same thought about the problems associated with “melting pot” multiculturalism and a concern that my own talking about the civic imaginary slipped into the white imaginary as I spoke about the importance of exposure (“Exposure to whom?” my better angels asked). And as dissatisfied as I am with mere exposure, I wonder if we could briefly celebrate exposure as a step on the justice continuum. I am thinking of the dreaded “ethnic aisle” in every American supermarket.

As you know, most of my scholarship is about war in some capacity. And war, like it or not, brings a lot of societal change. The typical focus is on how war advances communication technologies, but it’s also worth recognizing what war has done to our supermarkets. When US troops returned from Vietnam, for example, they had a hankering for South Vietnamese food. American supermarkets expanded their “specialty aisles,” which consisted mostly of Italian food products at the time (thanks to WWII), to include other items like rice vermicelli or glass noodles. Now our supermarket “ethnic” aisles consist of a nonsensical smattering of other “foreign” food products. Meanwhile Italian products have made their way out of the “ethnic aisle.” Olive oil can now be found with other cooking oils..

So I guess what I am thinking about as we apply cooking metaphors is to what extent is exposure a flash in the pan form of justice that would do well to stew for a while? I liked your line about care being a “continual collaborative practice” because it made me think about adaptation. My favorite part of cooking is the artfulness of adaptation. I am terrible about following recipes. I never have all the ingredients. I am a vegetarian. I like spicy things. I add. I eliminate. I taste. I adapt. And as I do, the food becomes an expression of who I am. So when I go to the “ethnic aisle” to buy plantain chips I am not looking for something exotic. I am looking for “my chips.” And when they slide across the checkout counter and the cashier says “huh, I’ve never seen these before '' and I say “they’re good with hummus,” I feel like something important is happening. I am tapping into the civic imagination. In that moment, the cashier and I glimpse ourselves as “part of a larger democratic culture.”

Almeida: Your art of adaptation that in the process brings others with you—wow! I love that so much. We’ve talked about so much in this piece— a plethora of big ideas that intersect our lives and our work—and again and again, what I take away from you is this stubborn optimism that engaging the civic imagination with others through food, through stories, that this has the potential to disrupt in ways many take for granted. You make me want to return to my work with new senses!

Lisa Silvestri is Associate Professor of Communication Studies at Gonzaga University. Her writing showcases creative ways people exert agency in even the most stringent circumstances. One of her areas of focus is the way social media links communication to connection, which helps produce and sustain individual and collective identities. Her book Friended at the Front won the 2016 James W. Carey Media Research Award for pioneering cultural approaches to the study of social media. In 2017 she received a major grant from The National Endowment for the Humanities in support of her community-based initiative, Telling War, which helped surface and inspire Veteran voices through a variety of story forms. She has written, lectured for, and had her research featured in several popular outlets including The Washington Post, The New York Times, The South by Southwest Festival, and The 92nd Street Y.

Elaine Almeida is a Mass Communication doctoral student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison with minors in Gender and Women’s Studies and Transdisciplinary Visual Cultures. She is a qualitative scholar interested in how minoritarian storytellers utilize care to transform digital spaces. Previously she attended the University of Texas at Austin for both a B.S. and M.A. in Advertising. She further explores her interests through her role as a freelance digital artist.

May 16, 2022

The Trans* Fantasy in Harry Langdon’s The Chaser

In the fall, I taught a seminar on American film Comedy with a particular focus on comic performance and slapstick. I included a range of lesser known figures but I also wanted to represent the big Four silent comedians — Keaton Lloyd, Chaplin, and Langdon. Langdon is often an afterthought these day since modern audiences often find it difficult to appreciate his slow-reaction style alongside the fast rough and tumble of his contemporaries. I ended up selecting The Chaser, one of the films where Langdon directed himself, pushing past the slander that Frank Capra fostered in The Name Above the Title that Langdon lost his way once he rejected Capra’s shaping role. This turned out to be one of the more popular films from the class with students intrigued by its difference from other silent comedy and especially its bold play with gender identity, which has to be seen to be believed. One MA student, Sabrina Sonner wrote an essay on the film as a Trans fantasy which suggests why Langdon may be especially meaningful to the generation coming of age right now.

The Trans* Fantasy in Harry Langdon’s The Chaser

by Sabrina Sonner

Introduction

Watching Harry Langdon in The Chaser, I am transfixed by his hat. Throughout the film, he appears as a philanderer in a night club, a guilty husband in court, a wife in the kitchen, a illicit fugitive, a uniformed captain, and a ghost-like apparition. He falls off a cliff in a runaway vehicle, lays eggs, kisses the iceman, and is nearly driven to suicide. And, throughout it all, the hat remains.

This consistent signifier of his identity stays with him throughout the film, which takes the basic premise of The Husband (played by Harry Langdon) accused of infidelity and court ordered to “take his wife’s place in the kitchen, or serve six months in jail.”[1] He dons a dress and performs his wife’s role, while The Wife (played by Gladys McConnell) takes on her husband’s role. Left at home, Langdon must deal with unwanted advances from the iceman and bill collector. As a result, he tries and fails to kill himself, writing a note that states he is leaving because “no woman knows what it is to go without pants.”[2] At the golf club with his hyper-masculine friend, he rediscovers a masculine uniform, and through a series of mishaps returns home covered in white flour. Though his mother-in-law flees, his wife returns to his arms, and the same intertitle that opened the film closes it, proclaiming “In the beginning, God created man in his own image and likeness. A little later on, he created woman.”[3]

While it may be one of Langdon’s less discussed films, I believe The Chaser opens up unique spaces surrounding gender and identity through interweaving Langdon’s innocent star persona with the potential of comedy to disrupt societal expectations. Within the history of clowns and silent comedians, there exists a power to break away from normative societal values.[4] We see this idea in Langdon’s disruption of gender in the film, as his comedic identity remains consistent while his gender presentation wildly fluctuates. Additionally, the slapstick nature of the film opens up ideas around the body and what it is allowed to do. Though made to dress a certain way, Langdon is still able to freely use his body in the world in a way enviable to a trans* body. In the way Langdon is clothed and in his undamageable slapstick body, a trans* fantasy emerges. What if I could wear a dress and be seen as a woman? Or wear a suit and be seen as a man? The film highlights the absurdity of the world responding to a single gendered indicator so strongly, but also opens up a freeing daydream that asks, “What would happen if we could be seen this way?” Langdon’s body never bruises, breaks, or tears – it behaves how he wants it to. With mine, I consider thousands of dollars of surgery to get it to behave as I wish. In this conflux of gender non-conformity, traditionally gendered clothing, Langdon’s consistent star persona, and a freely controlled slapstick body, The Chaser creates a fantastical trans* space.

In my journey through discovering my identity, I have understood it as the way one sees oneself internally, the way this is reflected to the world externally, and most importantly the way one searches to find a happy combination of the two. To that extent, this essay is structured in those three parts, pulling on theorists such as Jack Halberstam, Teresa de Lauretis, Louise Peacock, James Agee, and Muriel Andrin to connect ideas between comedy and queerness.

Langdon’s Consistent Star Persona and the Queerness of Childhood

Throughout The Chaser, Langdon is depicted with an unwavering consistency through his identifiable comedic persona, including his blank face, childlike innocence, and, of course, that hat. Regardless of his attire in the film, the way in which he comedically responds to situations and the recognizability of his star persona shines through. This sense of his baby-faced naivete is detailed by James Agee is his essay on silent film comedy:

“Like Chaplin, Langdon wore a coat which buttoned on his wishbone and swung out wide below, but the effect was very different: he seemed like an outsized baby who had begun to outgrow his clothes. The crown of his hat was rounded and the brim was turned up all around, like a little boy’s hat, and he looked as if he wore diapers under his pants. His walk was that of a child which has just gotten sure on its feet, and his body and hands fitted that age. His face was kept pale to show off, with the simplicity of a nursery-school drawing, the bright, ignorant, gentle eyes and the little twirling mouth…. He was a virtuoso of hesitations and of delicately indecisive motions, and he was particularly fine in a high wind, rounding a corner with a kind of skittering toddle, both hands nursing his hatbrim.”[5]

In The Chaser, we see this childlikeness in the consistency of his reactions, where he responds with a great deal of perplexity to the absurdity of the situations that he finds himself in, especially gendered rituals. Throughout the film, he seems unable to fully grasp any gendered roles assigned to him, both feminine and masculine. For instance, the charge he faces during the film is that of being an unfaithful or unruly husband. However, looking at the film’s depiction of this behavior, Langdon hardly seems the type. He goes to this club to eat peanuts and watch. Though slightly voyeuristic, this depiction is relatively tame in comparison to the way a philandering womanizer could appear. When he finishes in the club, he then dons a masculine uniform, which fails him in his goals of appearing the idealized husband. He fairs no better when he performs the wife’s role. In his dress, he seems uncomprehending of feminine ideas, such as the cooking behaviors he is asked to take on as well as understanding of reproduction, albeit that of chickens and eggs. When he returns to his masculine attire, he counters the hyper-masculinity of his friend while golfing. Within these scenarios, which are rife with gendered expectations, Langdon always fails to measure up, or even understand exactly what he’s being measured up to.

Langdon’s child-like lack of understanding of gendered norms creates a parallel with Jack Halberstam’s writings on the queerness of childhood. When writing of childhood and its depictions in cinema, Halberstam writes:

“There is nothing natural in the end about gender as it emerges from childhood; the hetero scripts that are forced on children have nothing to do with nature and everything to do with violent enforcements of hetero-reproductive domesticity. These enforcements, even when they can accommodate some degree of bodily difference, direct children toward regular understandings of the body in time and space. But the weird set of experiences that we call childhood stands outside adult logics of time and space. The time of the child, then, like the time of the queer, is always already over and still to come.[“6]

Though Langdon is not a literal child, his childlike nature evokes this queerness. He acts as a receptacle that the world places meaning on. As he attempts to sort through it, he appears as if he’s a child completely unaware of what is expected of him and encountering gendered expectations for the first time. In both his masculinized uniform and feminized wife’s attire, he seems out of place, like a child playing dress-up. Langdon’s character operates in a different logic from the rest of the world and, due to his specific star persona, encapsulates this childlike logic and queer aspect of the time of childhood.

To illustrate the innocence and consistency of Langdon’s comedic persona in a specific example, throughout The Chaser, Langdon has this consistent deadpan reaction, where he faces the camera and blinks a couple times, uncomprehending the absurdity of the comedic bit that just happened. We see this throughout the film as a constant presence, whether he is reacting to a woman falling into his arms when he wears his masculine uniform, the iceman kissing him when he dons a dress, or when he lays an egg. Alongside his ever-constant hat is a solidified comedic identity that refuses to adapt to ever-changing gendered expectations. In Langdon’s confusion regarding the gendered expectations, and the consistency of his identity beneath it all, there is space within the film to question alongside Langdon exactly how valuable these societal expectations are.

Additionally, I would argue that there’s a queerness to Langdon’s body as a slapstick body. His star persona adheres to ideas that Muriel Andrin considers writing of an unbreakable slapstick form:

“These are “bodies without organs,” immune to fragmentation or, when they do suffer fragmentation, insensitive to trauma. They remain whole no matter what the threat, displaying not a permanent moral integrity like melodramatic characters, but a lasting physical integrity… The slapstick world is a perfect place for instant healing.”[7]

There are many ways in this world that the trans* body can find itself under threat or in need of healing, whether it is due to growing rates of violence against transgender and gender-nonconforming people,[8] or trans* bodies themselves being voluntarily surgically modified to better fit one’s gender expression. The idea of the resilient slapstick body appears in The Chaser in a sequence near the end of the film, where Langdon hides in the trunk of a car that topples off a cliff and crashes through multiple billboards into his kitchen without troubling Langdon one bit. In a more serious and subtle way, the scene in which he fails to kill himself in several ways can be read as the trans*, slapstick body resisting its own demise and providing a protection that the individual needs despite their momentary wants.

Altogether, the confused, youthful quality of Langdon’s star persona connects his performance to a queer period of childhood, and the slapstick nature of this comedic body opens spaces for a specifically trans* imagination of the carefree, freedom of physical expression. The internal reflection of identity within Langdon’s star role in this film establishes a consistency and queerness to his self that clashes with the way society views him throughout the film.

Society, Gender, and The Clown Outside It All

While Langdon’s identity remains constant in the visibility of his comedic star persona to the audience, society takes gendered cues from his clothing and behavior and focuses on them to an absurd degree. Additionally, his role as a clown in the film places Langdon as a figure outside of societal boundaries to whom failure is central. Louise Peacock writes of the clown as “an outsider and a truthteller” who can comment on the societies in which they live.[9] Peacock additionally writes of the way failure is a part of clowning:

“Failure or ‘incompetence’ is a staple ingredient of clown performance… Clowns demonstrate their inability to complete whatever exploit they have begun. In doing so they speak to the inner vulnerability of the audience whose members are often bound by societal conventions which value success over failure.”[10]

The failures of Langdon within the film largely relate to his inability to adhere to gendered roles, such as his initial failings at masculinity that bring about the film’s inciting incident and his subsequent failures to perform his wife’s duties in the kitchen. In doing so, he highlights the constructed nature of the assignment of these duties based on gender. He places himself outside of the gendered expectations of society in a literal way in the opening scene, where he appears a dance club just to watch the activities. And in the comedic bits of the film, his inability to perform either masculinity or femininity allows the audience to consider the facades of those structures. In watching him actively try to learn and fail at these activities he’s been given based on his gender assignment, there is a trans* understanding of the failure to perform at the roles of the gender one is assigned at birth, as well as the complexity of learning the rituals of one’s own gender.

The failings of the clown echo Jack Halberstam’s considerations of failure and queerness, solidifying Langdon’s placement in the film as a queer, comedic outsider. In Halberstam’s writings on queerness and failure, Halberstam writes:

“The Queer Art of Failure dismantles the logics of successes and failure with which we currently live. Under certain circumstances failing, losing, forgetting, unmaking, undoing, unbecoming, not knowing may in fact offer more creative, more cooperative, more surprising ways of being in the world. Failing is something queers do and have always done exceptionally well; for queers failure can be a style, to cite Quentin Crisp, or a way of life, to cite Foucault, and it can stand in contrast to the grim scenarios of success that depend on “trying and trying again.”[11]

In applying Halberstam’s ideas around failure to the film, we can find joyous resistance in the way that Langdon fails at the tasks placed before him in the film. His placid reactions to his failures allow us to safely fantasize about the possibilities that open up before us if we too embrace this logic of failure.

Further considering the way the world interacts with Langdon by way of his encounters with the bill collector and iceman, we can apply ideas surrounding the technologies of gender from Teresa de Lauretis to the film. Within her essay “The Technology of Gender,” de Lauretis establishes gender as a construction that is inseparably connects gender, work, class, and race, writing, “social representation of gender affects its subjective construction and that, vice versa, the subjective representation of gender – or self-representation – affects its social construction.”[12] Given the complexity with which de Lauretis breaks down the social construction of gender, there is an absurdity to the simplicity to the way gender operates within the film when it comes to passing as a gender within the film. As soon as Langdon changes his clothes, the outside world chooses to see him as a woman. By changing one factor of his appearance, Langdon completely alters the way the world views his gender. In contrast, however, we still see Langdon as himself due to his aforementioned star persona, challenging the notion that gender operates this discretely. While the behavior of the men towards Langdon is largely disrespectful, leering at and nonconsensually kissing him, there is also a small space within these interactions to read an absurd form of respect. They see someone placing a feminine indicator on themself, and despite the obviously visible Harry Langdon beneath it, they choose to treat the individual as the presentation he puts forth into the world. Returning to de Lauretis’ theories, the film itself also operates as a technology that can expand and challenge notions of gender and, through this representation, hope to affect its societal construction.

The simplicity of the direct correlation between Langdon’s changing outfits and the way the world genders him opens up a fantasy that, while absurd, evokes a trans* desire to live within a world that could operate in the way that the world of The Chaser does. In Scott Balzerack’s writing on queered masculinity in Hollywood comedians, he brings up the way that “as a gendered subject, the male comedian rearranges (or, at times, rejects) heteronormative protocols.”[13]Viewing Langdon as a gendered subject within the film, he distorts and evades masculinity and femininity as much as he can, playing within a space that allows him to transform in an almost enviable way.

Unifying Gendered Identity Through a Familiar Spectator

Between the tensions of Langdon’s constant identity to the audience and his shifting gender presentation to the world, one might wonder if the film offers a point of resolution of these external and internal identities. By its closing shot, the film leaves us with an image of Langdon remaining in his dress and hat and reuniting with his wife, who has returned to her more traditionally feminine clothes. Looking back at the role played by Gladys McConnell as The Wife in the film provides the answers and resolution we seek.

At the start of the film, McConnell is seen talking nonstop over the phone at her silent husband, and it is her desire to divorce him that brings about the gender-swapping court order. While nothing in this order explicitly mentions her, in the following scenes we see her partially switch roles with her husband – she wears a blazer and tie with a skirt as an incomplete transference into his role. In this outfit, there are suggestions at her failures at femininity when she finds her husband’s suicide note and, believing him dead, sobs until her make-up runs to a heightened extent. While Langdon’s arc throughout the film depicts him failing at femininity in a skirt, McConnell fails at the same ideas of gender while dressed oppositely. In addition, despite the change in roles, she still sees him as her husband, referring to him as such with her friends later in the film. This contrasts with the starkly shifted view of Langdon’s gender by the iceman and bill collector. The film gives her the power to see his identity through the façade of his clothing. When Langdon returns to the house covered in flour, his mother-in-law runs out in fear of a ghost while McConnell, after a temporary fright, recognizes and embraces her husband.

Within this ending moment, some of the more nuanced ideas of gender within the film come together. After having both the husband and wife change their gendered attires, reuniting them when the wife has changed back but the husband remains the same gives a sense of ambiguity around the return to gendered roles within the film. While there is a normative reading of this ending that reunites the heterosexual couple with each person in their place, the actual execution of it has two femininely clothed individuals reuniting. With McConnell recognizing her husband beneath it all, there is an acknowledgement of his identity separate from his presentation. In the space with his wife, Langdon can be seen for who he is, regardless of how he presents. The film closes on a final shot of Langdon with his usual puzzled reaction to his wife returning to him, albeit with a couple of smiles tossed in. Coupled with the closing title reminding us of God creating man in his image and creating woman later on, there is a hint at the queer, homosocial world predating woman, as well as a challenge to the audience in if these binary viewpoints still hold up after watching a film that so comedically unpacks the artificiality of their construction.

Conclusion

By applying a trans* perspective to The Chaser, we can see the way that the film negotiates ideas gender, considering where it is performative, intrinsic, and a part of one’s identity. While there are complex structures around gender in society, there is something delightfully freeing about the space created by the film. In the comedic failures and childlike incomprehension of Langdon, there emerges a queerness in the film that is only heightened by its preoccupation with gender. There isn’t one specific trans* identity explored within the film, but a variety of resonances that makes an umbrella term more appropriate than a specific notion. For instance, in viewing a fantasy of wearing a dress and being seen as a woman, there’s a trans-feminine fantasy. In the idea that he remains a man beneath his clothing regardless of how everyone views him, we see the opposite in the way of a trans-masculine fantasy. And in his positioning throughout the film that remains as neither successfully the uniformed studly husband nor the submissive wife, but finding peace in his final image of a ghost-like version of himself, there’s a non-binary desire of finding a space separate from any of these rituals. Altogether, the film provides evokes a sense of trans* desire through the absurdity with which its gendered rituals exist, the connection between queerness and comedic failure, and the queerness that Langdon’s childlike persona.

Sabrina Sonner is a recent graduate of the University of Southern California’s Cinema and Media Studies Masters program. Their work focuses on queer studies, interactive media, and media that supports live communal forms of play. They have previously been featured at USC’s First Forum conference in 2021, where they examined late stage capitalism through a playfully destructive reimagining of the board game Monopoly. Outside of academia, Sabrina works professionally in new play development for theatre.

Works Cited

Agee, James. “Comedy’s Greatest Era.” Life, 1949. https://scrapsfromtheloft.com/2019/11/17/comedys-greatest-era-james-agee/

Andrin, Muriel. “Back to the ‘Slap’: Slapstick’s Hyperbolic Gesture and The Rhetoric of Violence,” Slapstick Comedy (AFI Film Readers). Routledge, 2009.

Balzerack, Scott. “Someone Like Me for a Member.” Buffoon Men: Classic Hollywood Comedians and Queered Masculinity. Detroit: Wayne State University, 2013.

The Chaser. Harry Langdon. Harry Langdon Corporation. First National Pictures. 1928.

De Lauretis, Teresa. 1987. “The Technology of Gender.” Technologies of Gender: Essays on Theory, Film, and Fiction. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1-30.

“Fatal Violence Against the Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Community in 2021.” Human Rights Campaign. 2021. https://www.hrc.org/resources/fatal-violence-against-the-transgender-and-gender-non-conforming-community-in-2021

Halberstam, Jack. “Becoming Trans*.” Trans*: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability. Oakland: University of California Press, 45-62. 2017.

Halberstam, Jack. The Queer Art of Failure. Duke University Press Books. 2011.

Peacock, Louise, “Clowns and Clown Play,” in Peta Tait and Katie Lavers (eds.), The Routledge Circus Studies Reader. London: Routledge, 2016.

[1] The Chaser. Harry Langdon. Harry Langdon Corporation. First National Pictures. 1928.

[2] The Chaser

[3] The Chaser

[4] Peacock, Louise, “Clowns and Clown Play,” in Peta Tait and Katie Lavers (eds.), The Routledge Circus Studies Reader. London: Routledge, 2016. 90.

[5] Agee, James. “Comedy’s Greatest Era.” Life, 1949.

[6] Halberstam, Jack. “Becoming Trans*.” Trans*: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability. Oakland: University of California Press, 61. 2017.

[7] Andrin, Muriel. “Back to the ‘Slap’: Slapstick’s Hyperbolic Gesture and The Rhetoric of Violence,” Slapstick Comedy (AFI Film Readers). Routledge, 2009. 232

[8] “Fatal Violence Against the Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Community in 2021.” Human Rights Campaign. 2021. https://www.hrc.org/resources/fatal-v...

[9] Peacock, 88.

[10] Peacock, 86.

[11] Halberstam, Jack. The Queer Art of Failure. Duke University Press Books. 2011. 2-3.

[12] De Lauretis, Teresa. 1987. “The Technology of Gender.” Technologies of Gender: Essays on Theory, Film, and Fiction. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 8-9.

[13] Balzerack, Scott. “Someone Like Me for a Member.” Buffoon Men: Classic Hollywood Comedians and Queered Masculinity. Detroit: Wayne State University, 2013. 4

May 12, 2022

Global Fandom Jamboree Conversation: Hyo Jen Lee (South Korea) and Kirsten Pike (Qatar) (Part Two)

illustrator/SF writer Park Moon Young.

Response to Kirsten Pike's response

(by Hyo Jin Kim)

Dear Kirsten and everyone,

Thank you so much for your thoughtful response.

You raised several interesting issues: Korean feminist SF (what the government's scientific discourse is in terms of reaching the public, especially women and girls; how Korean feminist SF expresses Korean sentiment and experiences; what common themes/characteristics of Korean feminist SF are; similarities vs. differences of Korean feminist SF and Western SF; male participants in feminist book clubs), Doctor Who fandom and comparisons with the Scully effect, and the response for the 13th Doctor, Jodie Whittaker.

First, I want to start with some good news and changes in terms of the science culture in South Korea. Since my dissertation, the Korean government and science communicators and experts have reached out to the public for science culture. ‘The Science & Culture Consultative Group’ was established last month, April 2022. This group will work mainly on several missions, such as spreading scientific and cultural activities, designing scientific projects, installing collaborative platforms for developing scientific culture, providing research/suggestions for scientific culture and its policies, filming and producing scientific images and broadcastings, holding academic conferences and seminars, and completing other voluntary scientific and cultural activities. As this group supports and encourages voluntary scientific and cultural activities, it may include some SF fandom activities. I am excited about the group and looking forward to their actions. This group will be the bridge between the public (hopefully include SF fans) and the government in terms of science culture. The government’s efforts in science culture have been accomplished through KOFAC and WISET. The Korea Foundation for the Advancement of Science and Creativity (KOFAC) leads science culture and develops policies as a quasi-governmental and non-profit organization under the Ministry of Science and ICT. In addition, the Korea Foundation for Women in Science, Engineering, and Technology (WISET) is a public institution funded by the government to encourage girls and women in the STEAM (A stands for Art) fields. According to WISET, the gender gap in natural science and engineering has decreased by 1.0% and 10.2%.

Korean SF and especially Korean feminist SF may step ahead of the government's science discourse. Korean feminist SF encourages readers to experience the future and even the current status quo, such as sexist oppression, discrimination, climate change and facing and living with non-human species, including aliens, AI, etc. Korean feminist SF has become more popular with the public since the 2010s. Statistics from the online bookstore ‘Aladin’ show the growth of female readers in their 20s to 40s, as I mentioned in my opening statement. With the reboot of feminism, new young female SF writers such as Cho-Yeop Kim and Se-Rang Chung and their work have become popular with the public. Cho-Yeop Kim won the 43rd Korea Artist Prize with her If We Cannot Move at the Speed of Light (Hubble, 2019) and the 11th Young Writer's Award with her following works. Se-Rang Chung's work School Nurse Ahn Eunyoung (Minumsa, 2015) aired on Netflix's original series in 2020. Media industries also showed interest and started making cinematic dramas such as 'SF8', eight directors with eight original Korean SFs in AI, AR, robot, game, fantasy, horror, supernatural, etc. Now Korean readers and audiences have more chances to meet Korean SF through books and media. The entrance barrier of SF has become lower and easier than before for the public.

As I mentioned in the opening statement, book club participants strongly tied with Korean feminist SF compared to Western SF. One reason might be the Korean storytelling. Participants and the public readers read Korean names, places, and even world views in Korean. They are used to reading characters' Western words and Western world views, making them feel distant from the genre. However, young SF Korean writers' works depict Korean characters (even many Korean female characters, single, married, young, and old) with Korean names, places, and cultures, allowing readers to feel comfortable with Korean SF. Korean feminist SF is mainly concerned with society's various issues and presents many diverse voices of Korean culture. For example, South Korea's constitutional court ordered the law banning abortion must be revised by the end of 2020. It's been 66 years since abortion became illegal. At the end of 2020, several SF writers joined the #abolition of abortion campaign by writing and sharing short SF stories. Korean SF writers openly associate their work with social issues. Korean feminist SF reflects current social issues and lets readers consider what-if situations. Therefore, Korean feminist SF book club participants engage strongly with Korean feminist SF.

Kirsten asked about Korean feminist SF's common themes or characteristics, and I'm working on analyzing and researching as same theme of a book project this year. Fandom research and the sub-genre of feminist SF are rare and getting to start in South Korea. So far, I've seen in Korean feminist SF themes of disability, gender issues, various types of violence toward women and others, stereotypes of women and others, prejudice against women and others, posthuman, patriarchy etc. Analyzing common themes and characteristics of Korean feminist SF is in progress. As a Korean feminist SF reader, I’ve got the impression that every single voice seems to matter to Korean SF writers. Korean feminist SF and Western feminist SF have in common that feminist issues meet the SF genre. Feminist SF writers are actively involved with social issues and let readers find solutions through their imaginations. The difference between Korean feminist SF and Western SF is how feminist issues reflect Korean society. As famous Western feminist SF books have been translated into Korean, readers feel Western feminist SF to be learned rather than empathetic. Every culture deals with different feministic issues. This is why Korean readers get more comfortable and engage tightly with Korean feminist SF. Kirsten wondered if there were male participants in the feminist SF book club. There were no male participants in the "Meet without meeting; 500 days' journey of reading feminist sf" club, but there were some male participants in other feminist SF book clubs I participated. Those male participants had entirely different attitudes toward feministic issues. They joined the book club because they wanted to learn more and understand feministic issues through the book and discussion.

Kirsten asked the Doctor Who fandom about the Scully effect, however, I could not find any academic research in South Korea. SF fandom studies in South Korea are few. In the part of my dissertation, some Whovians learn and understand complicated physics terms through Doctor Who. In my dissertation, I suggested SF fandom as a part of science communication. Scully effect on The X-File seems to follow a similar path, approaching SF fandom as the part of science communication in popular culture. Therefore, finding Scully effect of The X-Files or any other SF in South Korea will be fascinating and could be a good research project for WISET. I was able to find a news article about the fandom of The X-Files. How I remembered The X-Files is unique and different from these days’ SF fandom because of the dubbed version. Kirsten mentioned watching the dubbed version of The X-Files, and there was a massive fanbase surrounding dubbing actors in the '90s PC era in South Korea. There were several fan communities for the dubbing actors and main characters, Mulder and Scully. Still, many fans remember Mulder and Scully as the dubbed version of the voices. One news article shows that The X-Files returned in 2016, and the dubbing actors as Mulder and Scully got the information from the fans and celebrated together. The dubbing actors were as famous and vital as the original actors of Korean The X-Files’ fans. In the '90s in South Korea, I and Korean people were familiar with dubbed versions of television programs such asMacGyver, The X-Files, and other foreign films and television programs. The dubbed actors were top-rated as well. I remember MacGyver's Korean dubbing actor's voice. I was shocked when I heard the actual voice of MacGyver (Richard Dean Anderson). It didn't sound right to me. I am sure this kind of experience is common for people who grew up in the '90s. The popularity and fandom of dubbed versions of films and television programs may differ. Focusing on the differences may present how international fans deal with original characters' voices vs. dubbing actors' voices in a different context. At the same time, the '90s PC era is significant to SF fandom studies in South Korea. That period began with SF fandom, translating Western SFs, and creating Korean SFs. Some current famous SF writers/critics have been actively involved with the '90s PC era since. Several Korean SF scholars consider the '90s PC era a significant time for Korean SF fandom, and research is in progress.

As Kirsten asked about the response of the 13th Doctor, the Jodie Whittaker of Korean Whovians, I would say this might be another good start for the future Doctor Who fandom studies. I was pretty excited about Jodie Whittaker being the 13th Doctor because The Doctor's gender has never been revealed on the show. Though I had to dig deeper for the research, glancing over several Doctor Who online fan communities' comments seem negative responses. As some fans welcomed the female Doctor, they were disappointed with her performance and storytelling. I don't think this is about Jodie Whittaker's performance but fans' frustrations with accepting the female Doctor. The program has run for more than 60 years. Old and even new Whovians are already too familiar with male Doctors. It might take some time to adjust to new perspectives, such as gender or race issues, on the Doctor.

It was an excellent opportunity to learn about Qatar girls’ Disney princess fandom and discuss dubbed versions of films and television programs. It’s been fun to be part of this Global fandom Jamboree Conversation. Always exciting to meet a friendly but inspiring colleague. Thanks again to Kirsten for the thoughtful feedbacks, and hope everyone also enjoyed our conversations.

Part 2: Second Response to Hyo Jin Kim

(by Kirsten Pike)