Henry Jenkins's Blog, page 9

April 5, 2023

The Sound of Protest: Bollywood’s Jimmy Jimmy and COVID unrest in China

In October 2022, following a Covid outbreak, factory workers in China began protesting the Chinese government’s stringent measures to control the spread. What followed was a series of protests against lockdowns and the government’s closed-loop management system that did not allow factory workers to leave the factory; this led to the virus spreading rapidly among the workers. The government came down heavily on the workers in trying to curb the protests. While the factory workers voiced their protest on the street and online, another subtler wave of online protest emerged as humor through the sound of Bollywood. The Chinese Tik Tok Duoyin abounded with videos of Chinese netizens (Internet citizens) singing Jimmy, Jimmy a popular Bollywood song from the 1980s. Jimmy Jimmy, however, is not just any Bollywood song; it was the youth anthem for many soviets and east Europeans in the eighties. In this post, we focus on primarily three aspects of this event. First, what qualities make a song a protest song? Second, how do we account for the transcultural, trans-linguistic flow of the song, and what does this exchange reveal about the cultural dissemination and absorption of Bollywood in China?

Why Jimmy Jimmy?

The song Jimmy Jimmy from the Bollywood film Disco Dancer (1984) has historically enjoyed a global resonance. In a time when the Soviet Union did not allow American exports, the sound of Disco made its way to the USSR and Eastern Europe through Bollywood. The song has had an interesting afterlife in the post-Soviet digital space through performers like Baymyrat Allaberiev, whose rendition of Jimmy Jimmy in 2009 brought back the Disco Dancer phenomenon, leading to multiple versions, performances, and renewed digital fandom. In the context of the circulation of the manifold Tajik and Uzbek versions of Jimmy Jimmy, Chapman notes that past film materials provide rich dispersed content that can often be reified with new meanings.[1] The digital in this context provides a fecund space for the osmosis of Bollywood’s malleable cultural form within transcultural spaces.

However, the question still bears asking, why Disco Dancer? The very specific kind of technological and capitalistic bent of Disco was unique, but it became a distinctive amalgamation when fused with Bollywood’s expressionistic and melodramatic overtones. Its catchy lyrics, over-the-top mise-en-scene, and melodrama entwined together to lend it a malleable quality that overlays well with the discursive malleability of the digital - that is ever-changing and evolving.

There are multiple factors that go into creating the digital malleability for Jimmy Jimmy. First, is the music and ease of lyrics. Second, is the sound of Disco “mix” that is more immediately subversive and situates the audience as the true star of the show. The hedonistic, subversive quality of disco comes together seamlessly in its Bollywood iteration with Jimmy Jimmy’s excessive and melodramatic mise-en-scene. It, therefore, became the perfect globally malleable Bollywood sound that is equally availed of by the Tajiks or the Chinese.

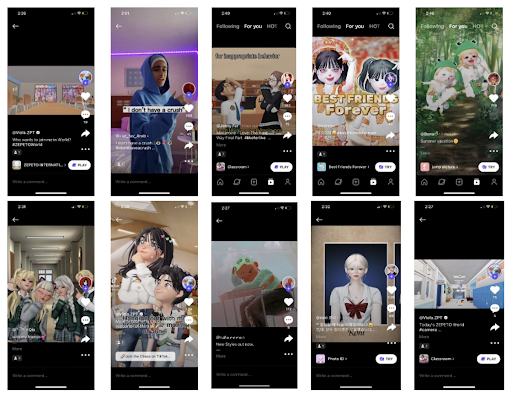

The performative sentimental excess in a film like Disco Dancer lends it a camp quality that is further accentuated by Disco. In protesting the state-imposed oppressive Covid restrictions, China’s netizens leaned into the malleable quality of the song and its Bollywood aesthetic. What was being performed was a queering of the Bollywood aesthetic wherein the Chinese performers of Jimmy Jimmy donned androgynous digital avatars through filters (See images below). The political resonance of the moment juxtaposed with the campy quality does not diminish the citizen videos’ political import. It rather accentuates it by couching a subversive protest by queering and highly stylizing the performance. The parodic adaptation of Jimmy Jimmy, in this instance, works as a political tool and strategy of subversion that allows them to escape direct state censorship yet communicate their protest musically.

1. Chinese Jimmy Jimmy — Douyin

2. Chinese Jimmy Jimmy — Douyin

figure 1: Screenshots from Jimmy Jimmy Performances on Chinese Tik Tok Douyin

Why Tik Tok? Platform MediationThe production, circulation, and reception of protest songs have become increasingly contingent upon the specific affordances of social media platforms such as Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok/Douyin. Specifically, in the case of rapid popularization of the Chinese renditions of Jimmy Jimmy on TikTok and Douyin, the televisual appeals of short video formats attract ordinary people to upload and share songs and comic performances in the first place, even when cultural producers might face tight censorship and surveillance in authoritarian states like China. The platforms’ algorithmic recommendation system further enables its over 1 billion users to quickly discover viral content, both within and beyond the Great Fire Wall (a euphemism for the censorship system in China). Moreover, netizens could share viral short videos from the platform of their origins to other platforms such as Instagram and Twitter. The multi-platform migration of a protest song like Jimmy Jimmy in social media, together with the accelerating news production cycles at news agencies around the world, provides further affordances for popularizing protest songs like Baraye and Jimmy Jimmy.

The popularization of a parody version of Jimmy Jimmy in the Chinese Internet needs to be situated in the tightening censorship and surveillance systems in China, particularly during its draconian zero-Covid policies in recent years. Since the early 2000s, Chinese netizens have created an Internet culture of “e-gao” through satire, parody, punning, spoofing, and mockery in countering official discourses and policies.[2] For example, netizens coined the meme of a “grass mud horse” (meaning “fuck your mother”) to implicitly criticize the government’s Internet policies in the late 2000s. Since then, the image of a “grass mud horse,” together with other made-up “mythical creatures” (shenshou), has become a symbol of resistance against censorship. During the global pandemic of COVID-19, apart from protest songs like Jimmy Jimmy, people have resorted to various forms of online parody and dark humor to express their discontent and dissent. On many college campuses, for instance, students under long lockdowns made paper pets and uploaded the photos and videos of them walking those pets on campus. Women podcasters, rather than directly criticizing the lockdown policies, humorously chatted about their experiences as a way to “make sweetness out of bitterness.”[3] The flourishing of online parody and humor attests to the resilience of Chinese netizens in dodging and dealing with censorship on a daily basis.

Besides satire and parody, translation also plays a crucial role in resisting censorship in China. Broadly speaking, translation is the practice of bringing the meanings of a given text across to another context through a certain medium. In China, translation of a specific text - be it televisual, audio, textual, architectural, or bodily - is a common tactic of protest in cyberspace.[4] One prominent example is that during Wuhan Lockdown, netizens used translation to relay messages that had been censored by the state.[5] The protest song based on the translation of the original Bollywood song Jimmy Jimmy is another powerful example of how translation and satire work together as a gesture of playful resistance against government censorship and covid policies.

Translation, in the case of Jimmy Jimmy, works through specific tactics of anonymity, transliteration, dubbing, and bodily performance. To start with, while the song became a hit within a few days on social media, the anonymous translator of the original lyrics remains unknown as of today. Thus, no individual could be potentially incriminated by the government. Moreover, the translation of Jimmy Jimmy into a protest song is, in fact, a process of mistranslation through transliteration. The original soundtrack is in Hindi; sometimes, English transliteration is displayed as well. The Chinese translation is often displayed on the screen as follows:

Jimmy

借米 (jie mi)

[Can I] borrow rice?

Aaja

哪家 (na jia)

Which family?

Jimmy

借米 (jie mi)

[Can I] borrow rice?

Aaja

俺家 (an jia)

[It’s] my family.

俺家里没米了(an jia li mei mi le)

My family does not have rice now

你家里有米吗?(ni jia li you mi ma)

Does your family have rice?

少拿点不需多 (shao na dian bu xu duo)

Take less, you don’t need more

Hindi Transliterated Lyrics Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy, aaja aaja aaja

English Translation Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy, come come come

Hindi Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy, aaja aaja aaja

English Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy, come come come

Hindi Aaja re mere saath

English Come with me

Hindi Yeh jagi jagi raat

English This night is without any sleep

Hindi Pukare tujhe sun

English Listen, it's calling for you

Hindi Suna de wohi dhun

English Sing the same tune for me

Hindi Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy, aaja aaja aaja

English Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy, come come come

Hindi Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy, aaja aaja aaja

English Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy, come come come

Hindi Aaja re mere saath

English Come with me

Hindi Yeh jagi jagi raat

English This night is without any sleep

Hindi Pukare tujhe sun

English Listen, it's calling for you

Hindi Suna de wohi dhun

English Sing the same tune for me

Hindi Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy, aaja aaja aaja

English Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy, come come come

Hindi Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy, aaja aaja aaja

English Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy, come come come

Hindi Aise gum-sum tu hai kyun khamoshi tod de

English Why are you quiet, break your silence

Hindi Jeena kya dil haarke pagalpan chhod de

English Don't lose your heart and live, don't be mad

Hindi Aise gum-sum tu hai kyun khamoshi tod de

English Why are you quiet, break your silence

Hindi Jeena kya dil haarke pagalpan chhod de

English Don't lose your heart and live, don't be mad

Hindi Aaja re mere saath

English Come with me

Hindi Yeh jagi jagi raat

English This night is without any sleep

Hindi Pukare tujhe sun

English Listen, it's calling for you

Hindi Suna de wohi dhun

English Sing the same tune for me

Hindi Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy, aaja aaja aaja

English Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy, come come come

Hindi Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy, aaja aaja aaja

English Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy, come come come

Hindi Jimmy aaja, Jimmy aaja

English Jimmy come, Jimmy come

Hindi Aaja re mere saath

English Come with me

Hindi Yeh jagi jagi raat

English This night is without any sleep

Hindi Pukare tujhe sun

English Listen, it's calling for you

Hindi Suna de wohi dhun

English Sing the same tune for me

As shown above, the Chinese lyrics phonetically mimics the Hindi lyrics but comes with new meanings. The opening line “Jimmy” is translated as “jie mi” (borrow rice) in pinyin, the official romanization system for Standard Mandarin Chinese in China, which becomes the most catchy phrase from the song. The term “aaja” is translated into two different Chinese meanings - one is “which family” and the other “my family” - which create a sense of a dialogue. The lines go to recreate a scene in which one is borrowing rice from someone else, perhaps their neighbors. This is a common scene during the COVID lockdowns when food supplies were short and people had to try everything they could to feed themselves. There have been many stories of people coordinating group-buying, crying out for help for their kids or the elderly, and helping both strangers and neighbors. The joyful lyrics and the playful bodily performance in the viral short videos, in a sense, remind people of the painful experiences of the constant fear of starvation and the lack of freedom to express their anger and frustration in public. The musical sound of Jimmy Jimmy despite its apparent sentimental campy frivolity embodies the subversive, performative potential of the sound of protest all the way from Tajikistan to China.

[1] For more see “Performing ‘Soviet’ film classics: Tajik Jimmy and the aural remnants of Indian cinema” by Andrew Chapman in Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema.

[2] Li, Hongmei. "Parody and resistance on the Chinese Internet." Online society in China. Routledge (2011): 71-88.

Meng, Bingchun. "Regulating e gao: Futile efforts of recentralization?." China's information and communications technology revolution. Routledge (2009): 64-79.

Yang, Guobin, and Min Jiang. "The networked practice of online political satire in China: Between ritual and resistance." International Communication Gazette 77.3 (2015): 215-231.

[3] Wang, Jing. "Lockdown sound diaries: Podcasting and affective listening in the shanghai lockdown." Made in China Journal 7.1 (2022): 151-161.

[4] Zhang, Weiyu, and Chengting Mao. "Fan activism sustained and challenged: participatory culture in Chinese online translation communities." Chinese Journal of Communication 6.1 (2013): 45-61.

Yang, Guobin. "The online translation activism of bridge bloggers, feminists, and cyber-nationalists in China." Media Activism in the Digital Age. Routledge (2017): 62-75.

[5] Yang, Guobin. The Wuhan Lockdown. Columbia University Press, 2022.

Biographies:Swapnil Rai is an Assistant Professor of Film, TV and Media at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Swapnil’s research is concerned with the intersections of politics, popular culture and media industries and brings together global media industry studies, transnational stardom, audience studies and women and gender studies. Her work has been published in a range of scholarly journals including Communication, Culture & Critique, Feminist Media Studies, International Journal of Communication, Jump Cut and Cinephile. Her book Networked Bollywood: How star power globalized Indian cinema is forthcoming with Cambridge University Press. Swapnil is a member of the editorial board of Pop Junctions and a board member of the feminist media collective Console-ing Passions. She tweets @i_swapnil_rai .

Jing Wang is an incoming Assistant Professor in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She is currently Senior Research Manager at the Center for Advanced Research in Global Communication (CARGC), Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. Jing’s research focuses on anthropology of Islam, race and ethnicity studies, sound and podcasting, feminist practices and theories, and transnational media. She has published in journals across disciplines such as New Media and Society, Made In China Journal, Asian Anthropology, Terrain: Anthropologie & Sciences Humaines, and Journal of Transformative Learning. Committed to public and multimodal scholarship, Jing co-founded TyingKnots 结绳志 and Global Media & Communication podcast series. You can find her on jing-wang.net and Twitter @JingWang0815.

March 27, 2023

A Bowl of Cherries: Footage of a Forgotten Happening

The following post was created as part of the assigned work for Henry Jenkins's PhD seminar, Public Intellectuals. The goal of the class is to help communication and media studies students to develop the skills and conceptual framework necessary to do more public-facing work. They learn how to write op-eds, blog posts, interviews, podcasts, and dialogic writing and consider examples of contemporary and historic public intellectuals from around the world. The definition of public intellectuals goes beyond a celebrity-focus approach to think about all of the work which gets done to engage publics — at all scales — with scholarship and critiques concerning the media, politics, and everyday life. Our assumption is that most scholars and many nonscholars do work which informs the public sphere, whether it is speaking on national television or to a local PTA meeting.

Life is just a bowl of cherries/— "Life Is Just a Bowl of Cherries," performed by Judy Garland. Original music by Ray Henderson and lyrics by Lew Brown, 1931.

So live and laugh at it all.

The satirical featurette A Bowl of Cherries (1961, dir. William Kronick) tells the story of a starry-eyed cowboy, named Sherman Williams, who moves to Greenwich Village with hopes of becoming America’s next great painter. It features prominent cameos by Jim Dine, Robert Whitman, and Lucas Samaras — three major pioneers of the downtown "Happening” scene. These artists introduce our protagonist to the prevailing style of “action painting,” made famous by Jackson Pollock and other Abstract Expressionists, forever altering his worldview. By the time A Bowl of Cherries hit theaters, action painting was on the verge of decline — making it a suitable subject of parody for artworld insiders witnessing these changes in real time.

figure 1: William Glover (AP), “Experimenting Film Director Swings Back into 'Silent'," The Amarillo Globe-Times, March 16, 1961, 20.

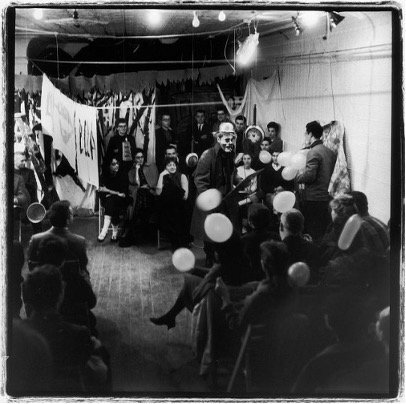

As active participants in “Painter’s Theater,” a process-oriented mode of performance art that flourished in the cooperative gallery spaces on Tenth Street in the early 1960s, Dine, Whitman, and Samaras were all experienced actors prior to making of A Bowl of Cherries. These semi-scripted, absurdist shows were staged in elaborate installations cobbled together from everyday objects, urban detritus, and expressionist paintings. Dine mused that the older generation of painters “Would have been embarrassed,” by these self-deprecating and delightfully nonsensical plays: “They would’ve said, ‘This isn’t serious. We are not actors. We are serious intellectuals. We are not circus performers.’” Creators of Painter’s Theater used comedy to puncture the self-seriousness of the prior generation, and to make dead-serious points about the role of art in a culture progressively geared towards mass-spectatorship. Much like Painter’s Theater, A Bowl of Cherries grapples with the legacy of action painting, asking what does art look like after Pollock? And, more existentially, what does an artist look like in a media landscape increasingly fascinated with the New York art world?

After reaching out to the film’s director and writer William Kronick via the comments section on YouTube, I had the opportunity to interview him on the phone on November 23, 2021.

Figure 2: Reaching out to William Kronick via YouTube.

Kronick told me he was inspired to make a film about the downtown art scene sometime in 1959 after reconnecting with his former college roommate, Bruce Glaser, the manager of Camino Gallery (one of several artist-run spaces on Tenth Street). At the time Glaser was dating Natalie Edgar, a painter and critic for ARTnews, who passed the script on to her brother George. A hotshot Wall Street investor keen on getting into the movie making business, George Edgar gave Kronick around $8,000 to make the picture no strings attached. With Glaser as his production coordinator and casting director, Kronick shot the entire film on location in Greenwich Village during a period of about twelve days in September 1960.

According to Kronick, the decision to cast working artists was financially motivated — as it was a vastly cheaper alternative to hiring professional actors. But as a stylistic choice, the casting is in keeping with a larger cultural shift in independent filmmaking towards realism and improvisation. Critic and filmmaker Jonas Mekas identified a new wave of American cinema “intimately linked with the general feeling in other areas of life and art: with the ardor for rock and roll; the interest in Zen Buddhism; the development of abstract expressionism (action painting); the emergence of spontaneous prose and New Poetry — all a long-delayed reaction against puritanism and the mechanization of life.”[1] Mekas points to Pull My Daisy (1959), directed by the photographer Robert Frank and painter Albert Leslie, as an example. Based on a play by Jack Kerouac (who also provides the film’s narration), this short chronicles a dinner party hosted by a railway brakeman and his wife, an abstract painter, featuring a star-studded cast of literary and artistic luminaries including Allan Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, Alice Neel, and Larry Rivers. "Pull My Daisy is an accumulation rather than a selection of images. It was made by non-professionals in search of that freer vision.”[2] In 1968 Leslie revealed that the film was in fact not improvised, but thoroughly rehearsed and scripted.[3] Pull My Daisy was successful (at least in part) because people believed the film to be improvised and thus truer to life.

Shot just two years after Pull My Daisy, A Bowl of Cherries operates under a similar fusion of reality and fiction. While the participating artists were not as famous as Ginsberg or Kerouac, they were nonetheless recognizable as “rising stars” in the New York artworld. Their presence in A Bowl of Cherries lends an air of authenticity to the project, enhanced by the film’s reliance on on-location scenery. At times the movie feels like a time capsule of 1960s New York, particularly in its documentation of now-defunct artists co-ops on Tenth Street, as the protagonist wanders through the actual, moving cityscape of Greenwich Village. However, the authenticity of the scene is doubly ruptured by the character’s ridiculous cowboy get-up and the flickering frame rate associated of a turn-of-the-century silent film.

figure 3: Fred McDarrah, View of Tenth Street Galleries, c. 1960

figure 4: View of Tenth Street Galleries from A Bowl of Cherries.

By toying with the aesthetic conventions of an old slapstick comedy, A Bowl of Cherries presents a proximate simulation of the downtown art scene primed for humorous critique. In a promotional interview for the film Kronick stated, “The fact that the actors can't talk, and the motion is unnatural creates a new reality.”[4] In keeping with the genre, the director substituted speech with old-fashioned title cards, which provide context for the pantomimed performances on screen. After reviewing a copy of the original script almost sixty years after the film’s production, Kronick remarked, “I couldn't believe it — I'm reading it and it's exactly the film that we shot. No changes…the title cards were all the same, identical.” From his recollection, the actors received the title cards prior to filming and used them as prompts for improvised action as the camera rolled. The title cards almost never line up with the mimed dialogue on screen, creating an odd dissonance between word and image.

The movie opens as a wannabe painter from the country, with the on-the-nose name Sherman Williams, is dropped off by a man in a convertible on the side of the West Side Highway. The driver is played by Kronick himself.

figure 5: Sherman Williams on the West Side Highway, with director William Kronick.

With several rolled-up canvases in hand, Williams dodges oncoming traffic in efforts to make it to the subway station, where he takes the train down to Christopher Street. Upon his arrival downtown he happens upon a group of stylish young women clad in all black, smoking cigarettes in front of Paperback Gallery (a literary hotspot in the Village). When Williams asks them where he can rent an artist’s studio they stare at him with skepticism, followed by a title card that reads: “Man, are you real?”

Figure 6: Sylvia Rudolph, Natalie Edgar, and Hilda Ruiz outside Paperback Book Gallery.

Getting the message, the cowboy backs away from the group of women and continues his downtown odyssey. After wandering around the Village, he stumbles upon the storefront of a laundromat advertising studio space for rent. The proprietor, played by painter James Hiroshi Suzuki, leads Williams through rubble-filled alleyways to get to a vacant loft.

figure 7: James Hiroshi Suzuki leading Sherman Williams to his new studio.

The space, according to Kronick, “was an actual downtown loft…about five blocks away [from the Tenth Street galleries]”. In the film, Williams hands over his life savings to the landlord and begins to hang his artwork up on the blank studio walls. As the cowboy unfurls his canvases, it is revealed to the audience that all of Williams’ paintings feature horses. Could there be a subject more out of step with fashionable New York?

figure 8: Sherman Williams and his horse painting.

After settling into the city, the protagonist finally goes to an art gallery in search of representation. As he walks into the space, he is confronted with abstract painting for the very first time, amounting to what can only be described as a revelatory experience.

figure 9: Sherman Williams encounters abstract art, and gallerist Bruce Glaser.

figure 10: Sherman Williams encounters abstract art, and gallerist Bruce Glaser.

Like Dorothy’s arrival in Oz, the film suddenly switches from black and white to color for a twenty-second interlude. Close-up shots of paintings are juxtaposed with images of Williams’ face, which switches from shock to suspicion, and ultimately satisfaction. Moving back to black and white, the cowboy shows his work to the gallery owner —played by Bruce Glaser. Unimpressed by the horse paintings, the gallerist nonetheless invites Williams to an art opening the following night.

This is where his true initiation into the art world occurs. Kronick shot this scene at an actual opening hosted at Great Jones Gallery, in celebration of a new show of paintings by Vivian Springford. Exhibition ephemera from the painter’s archive inadvertently reveals the filming date of this scene — September 26, 1960 —providing a more precise timeframe for the production of A Bowl of Cherries.

Figure 12: Vivian Springford in A Bowl of Cherries; exhibition ephemera from her exhibition, September 20, 1960.

Springford’s show was curated by critic Harold Rosenberg, one of the most influential proponents of action painting. Rosenberg most likely attended the party, and perhaps even passes by Kronick’s camera (although this is difficult to confirm visually). In the press release for Springford’s exhibition, Rosenberg writes: "a good number of people suspect that all it takes to be a modern painter is a beard, some canvas, and a good paint supply. Presumably, you do not even need a brush to paint abstraction. The reverse is true of Vivian Springford,” — a soak-stain painter in the vein of Helen Frankenthaler or Morris Louis.[5] Springford’s effusive, almost calligraphic paintings float in the background as Jim Dine, Robert Whitman, and Lucas Samaras are introduced on screen for the very first time, under the respective aliases of Benno Moskowitz, Tim Babka, and Max Theodopolous.

Figure 13: Robert Whitman as Tim Babka, Lucas Samaras as Max Theodopolus, and Jim Dine as Benno Moskowitz.

Figure 14: Robert Whitman as Tim Babka, Lucas Samaras as Max Theodopolus, and Jim Dine as Benno Moskowitz.

Figure 15: Robert Whitman as Tim Babka, Lucas Samaras as Max Theodopolus, and Jim Dine as Benno Moskowitz.

In the following scenes they proceed to school Williams in the various modes of abstraction. Samaras applies globs of paint to pieces of newsprint splayed out on the floor, and feverishly insists to the protagonist that “sensuous forms are the only ones to consider.” Whitman constructs a precariously hanging assemblage that almost hits Williams as it spins haphazardly around the room. Dine dips his hands directly into a can of white paint and uses his fingers as a brush. Maintaining a straight face, he reaches his paint-covered hand out towards Williams to say, “the tactile element in my work is wonderful.” Kronick stated that all the works featured on screen were made by the cast — although he did not recall what happened to these pieces after the end of the production, or if the artists considered these objects as a part of their oeuvre.

Figure 16: Sherman Williams gets a lesson in abstraction.

Figure 17: Sherman Williams gets a lesson in abstraction.

Figure 18: Sherman Williams gets a lesson in abstraction.

The idea of “performing” the artistic process for the camera is integral to discourse of action painting. Photojournalist Hans Namuth has been credited with with transforming Jackson Pollock “From a talented, cranky loner into the first media-driven superstar of American contemporary art, the jeans-clad, chain-smoking poster boy of abstract expressionism” through the medium of photography.[6] His widely circulated images of the artist at work depart from the long-standing convention of picturing the artist sitting stoically behind an easel.

figure 19: Jackson Pollock, by Hans Namuth, 1950.

Dine, in particular, was a voracious consumer of such heroic images of artists, stating in 1977: “As a college student, I schooled myself totally in the New York School, via ARTnews. I remember stealing bound volumes of ARTnews from the ’50s, tearing out pictures, and looking at de Kooning, Pollock, Kline, and everyone else from that period. I knew about everybody. It was an impressionable time for me. I was teaching myself about New York — the moves.” In his recollection Dine evokes something of the performative nature of these images (“the moves”) and suggests the importance of mediated images to his burgeoning art practice.

The Smiling Workman, one of Dine’s most important Painter’s Theater performances, is directly engaged with the legacy of Jackson Pollock. For this piece, Dine created then destroyed an abstract painting in front of a live audience, recreating a spectatorial experience in dialogue with Namuth’s photographs. The artist also decorated the set with white handprints, evocative of those left on Pollock’s canvases as traces of the artistic process.

Figure 20: Jim Dine in The Smiling Workman, photo by Martha Holmes, May 1960; Detail of Number 1A, by Jackson Pollock, 1948.

Figure 21: Jim Dine in The Smiling Workman, photo by Martha Holmes, May 1960; Detail of Number 1A, by Jackson Pollock, 1948.

Filmed six months after The Smiling Workman, Dine’s vignette in A Bowl of Cherries recreates aspects of this earlier work for the film camera. As in the performance, Dine presses his paint-covered hands into the canvas to show the protagonist an alternate mode of painterly expression, rooted in physical comedy.

After meeting with Dine, Williams soon becomes possessed with an almost manic drive to create new work. Wearing nothing but a pair of underwear and a bandana around his neck, Williams compulsively applies paint to both the canvas and his studio wall. He becomes so preoccupied with his work that he eventually loses his life savings and can only afford to feed his pregnant wife oatmeal.

figure 22: Sherman Williams tries abstraction.

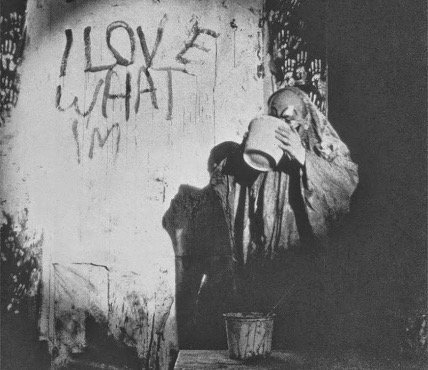

As in A Bowl of Cherries, the danger of artistic obsession is also the subject of The Smiling Workman. Filmmaker Stan VanDerBeek shot a version of The Smiling Workman staged specifically for video (versus live performance). Not unlike A Bowl of Cherries, the film rendition of The Smiling Workman is a silent short — sped up to exaggerate Dine’s frenetic motion across the set. Overcome by mania, the artist hastily scrawls the words “I love what I’m doing” onto a piece of paper, before proceeding to pour a can of paint on his head and crash through the canvas.

Figure 23: Jim Dine in The Smiling Workman, film by Stan VanDerBeak, 1960.

Whereas Dine punches through the painting at the end of The Smiling Workman, A Bowl of Cherries concludes with Dine visiting Williams in his studio, only to slip and fall onto the cowboy’s unfinished canvas. His physical commitment to the scene is striking and demonstrates the artist’s interest in over-the-top slapstick comedy as a destabilizing force. Dine once remarked, “I do not think Smiling Workman was funny. I do not think obsession is funny or not being able to stop one’s intensity is funny.”[7] Despite the artist’s insistence that the performance was not intended to be comedic, he is nevertheless dressed as a clown.

Figure 24: Jim Dine falling onto Sherman Williams’s canvas.

In the early part of his career, Dine repeatedly played with different figurations of the clown character. For example, in The Big Laugh (a happening orchestrated by Allan Kaprow in which actors laughed at the audience for seven straight minutes), Dine played a carnival barker, donning white face paint and a straw hat. In Vaudeville Collage, staged at the Reuben Gallery on June 11, 1960, the artist created his approximation of a cabaret show. Appearing once again in clown makeup as the show’s MC, Dine attached vegetables to pieces of string and made them “dance” around the stage like marionette dolls. Dine was even known to attend gallery openings dressed up in a clown costume, blurring the boundary between life and art.

Figure 25: Jim Dine (in hat) in The Big Laugh, by Allan Kaprow, 1960.

Figure 26: Vaudeville Collage, June 11, 1960.

Figure 27: Jim Dine in clown makeup at gallery opening, c. 1960.

Figure 28: Jim Dine in clown makeup at gallery opening, c. 1960.

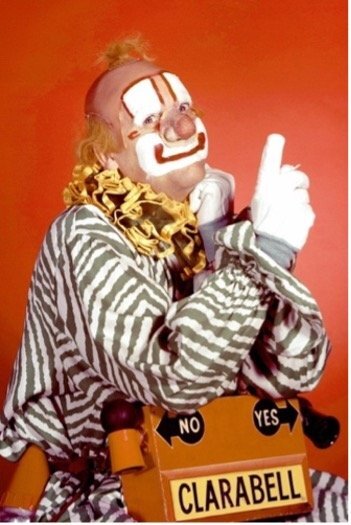

Discussing his creative partnership with Robert Whitman, Dine stated: “Because we had little children, we watched children's TV in the late '50s and early '60s and that said something about the kind of performances we made. We would refer to Captain Kangaroo…We listened to his way of speaking and the way the characters spoke. It put the performances out of the realm of literal theater by these characters for children speaking to them in this odd way, which wasn't naturalistic.”[8]

Figure 29: Bob Keeshan as Captain Kangaroo (L) and Clarabell the Clown (R).

Again, I find Dine’s reference to mass-media visuals incredibly fascinating. In performances such as Car Crash (1960), the artist did not act on a stage, but wandered freely through the audience — often pushing conventional boundaries of personal space. Although the painter scoffed at the suggestion that he was “the one who did the funny happenings,” laughter was an inevitable component of his outrageous and often uncomfortable performances. A photograph by Fred McDarrah, shows one such instance, in which critic Jill Johnson is pictured with her head tipped back in laughter as Dine (dressed in a Pierrot-inspired getup) lets out a guttural scream.

Figure 30: Jim Dine in Car Crash, November 1960. Photograph by Fred McDarrah.

What then, can we make of Dine’s purposefully comedic turn in A Bowl of Cherries? And how does the technology of film amplify the comedy that characterizes of Painter’s Theater?

To some extent, A Bowl of Cherries provided a space for Dine to act out (or perhaps become) the film sequences that inspired Painter’s Theater. Dine’s performance is filtered through the logic of silent comedy, which results in something quite different (and much tamer) than his Painter’s Theater performances. While he doesn’t wear a literal clown mask, the artist nonetheless plays a fool — and even ends up with a paint-covered face after taking a pratfall on screen.

While it is tempting to over-read A Bowl of Cherries as a “lost” work of Painter’s Theater, the participating artists had very little control over the end product. The filming of A Bowl of Cherries coincided with a period of financial instability for Dine; in August 1960, evidenced by a postcard the artist wrote a postcard to the dealer Allan Karp thanking him for sending a check.

Figure 31: Postcard from Jim Dine to Ivan Karp, c. August 1960. Ivan C. Karp papers and OK Harris Works of Art gallery records, 1960-2014, Archives of American Art.

While Kronick couldn’t tell me what kind of compensation Dine received for his performance in A Bowl of Cherries, the film shoot occurred in between two of his major performances (Vaudeville Collage, June 11, 1960, and Car Crash, November 1-6, 1960) indicating that the artist undertook the project during a short hiatus, perhaps just as a fun way to make some extra money.

Kronick lost touch with the cast shortly after filming wrapped at the end of September 1960. Although A Bowl of Cherries was accessioned into MoMA’s film collection shortly after its release, the short featurette has rarely been reshown and has virtually no presence in art historical literature. Nor is it cited in any of Dine’s numerous career-spanning monographs, despite the many connections with other works in his oeuvre.

A Bowl of Cherries offers an unexpected point of entry into Painter’s Theater and its relation to film.. This short featurette is a curious work at the crossroads of avant garde and popular culture and nicely captures the transition from painterly post-war art culture to the performative art culture that comes to dominate in the 1960s.

[1] Artist statement printed in Mekas, “New York Letter: Towards a Spontaneous Cinema,” 120.

[2] Artist statement printed in Mekas, “New York Letter: Towards a Spontaneous Cinema,” 120.

[3] Alfred Leslie "Pull My Daisy: Ten Years Later, Village Voice, November 28, 1968, 54.

[4] See William Glover (AP), “Experimenting Film Director Swings Back into 'Silent'," The Amarillo Globe-Times, March 16, 1961, 20

[5] Courtesy Vivian Springford Estate, Almine Rech Gallery, New York, NY. See also Phong Bui, ed., Vivian Springford (Brusssles, BE: Almine Rech Editions, 2018).

[6] Ferdinand Protzman, “The Photographer's Snap Judgment,” Washinton Post, May 23, 1999. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/style/1999/05/23/the-photographers-snap-judgment/7062b20f-a479-4dad-af27-c1144896e6bb/

[7] Statement quoted in Michael Kirby, Happenings: An Illustrated Anthology (New York: EP Dutton, 1965), 186.

[8] "Walking Memory: A Conversation with Jim Dine, Clare Bell and Germano Celant," 63.

BiographyRose Bishop is a PhD student in the Department of Art History at the University of Southern California and an enrollee in the Visual Studies Research Institute (VSRI). She received her master’s degree in Art History and Curatorial Studies from Hunter College in 2021. Her scholarship focuses on the history of photography and mass media in the United States, with an emphasis on celebrity culture and fashion. Bishop is also a 2022-23 National Endowment for the Humanities Graduate Fellow with the VSRI’s Images Out of Time seminar, an interdisciplinary workshop that considers how images travel through time, dropping in and out of linear histories and reshaping perception, institutions, and social practices along the way.

Her article, “‘The Whole Show on One Photograph’: Gordon Anderson and the Making of a Star at Harlem’s Apollo Theater,” will be published in the Spring 2023 issue of Transbordeur and represents the first in-depth exploration of the photographer’s prolific career as a concert documentarian. Bishop has also contributed writing for 125th Street: Photography in Harlem (Hirmer Publishers with Hunter East Harlem Gallery, 2022) and What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999 (10x10 Photobooks, 2021), which received the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation Catalogue of the Year Award in 2021.

Prior to her academic career, she worked as an archivist at the Richard Avedon Foundation.

March 22, 2023

We Witnessed One of the Best FIFA World Cups Ever Played on the Graves of Thousands of Migrant Workers… What Now?

The following post was created as part of the assigned work for Henry Jenkins's PhD seminar, Public Intellectuals. The goal of the class is to help communication and media studies students to develop the skills and conceptual framework necessary to do more public-facing work. They learn how to write op-eds, blog posts, interviews, podcasts, and dialogic writing and consider examples of contemporary and historic public intellectuals from around the world. The definition of public intellectuals goes beyond a celebrity-focus approach to think about all of the work which gets done to engage publics -- at all scales -- with scholarship and critiques concerning the media, politics, and everyday life. Our assumption is that most scholars and many nonscholars do work which informs the public sphere, whether it is speaking on national television or to a local PTA meeting.

On December 18, 2022, approximately one out of every five human beings on Earth watched Lionel Messi lift the World Cup for Argentina in Qatar. What seemed like the pinnacle of everything sports, culture, politics, entertainment, and humanity was reached when Gonzalo Montiel neatly tucked in that 4th Argentina penalty to the right of French captain and goalkeeper, Hugo Lloris. What still replays in my mind, as well for millions of others, is iconic Argentinian American sports commentator, Andres Cantor, calling the game live in Spanish for Telemundo as that final penalty went in, “GOOOOOOLLLLLLLL! ARGENTINA CAMPEÓN DEL MUNDO! ARGENTINA CAMPEÓN DEL MUNDO!” as he smiled and cried on live air.

Andrés Cantor, who moved to the U.S. from Buenos Aires as a teenager, calls Argentina winning the World Cup: pic.twitter.com/4PougSj1g7

— luffy (@vvsLuffy) December 18, 2022

Now rewind 12 years to December 2, 2010, when FIFA announced a shock when Qatar - a small Arab Gulf nation that wasn’t too well known on the world stage and had almost no football/soccer history - was awarded the bid for the 2022 FIFA Men’s World Cup, beating out the likes of England and the United States. FIFA’s decision clearly set off alarms concerning suspicions of corruption and bribery. Out of the eight stadiums that were to host World Cup matches, seven of them were not even built yet. The country was in no shape to host the largest sporting event in the world, and so a 12-year rapid growth project ensued.

Laurence Griffiths/Getty Images

Quickly, it became clear that this project was fueled by migrant laborers (mostly from South Asia) under a strict labor system called the Kafala. Pete Pattison came out with a groundbreaking exposé on how Qatar was essentially operating under labor conditions that many referred to as modern day slavery. Migrant workers in extremely economically precarious situations were essentially exported by contracting agencies in their home countries under misleading employment terms and (in many cases) worked to death. Nepali migrant workers made up a disproportionately high number of Qatar’s workforce in the last decade, listed as the second most populous group in the country (even ahead of Qatari nationals). The majority of Qatar’s population is composed of migrant workers, with most of them coming from South Asian countries.

While the exact number is disputed, over 6,500 workers were killed by the time the kickoff whistle blew for the opening Qatar vs. Ecuador match. Many people were aware of these conditions around this 2022 FIFA World Cup, yet so many didn’t know what to do about it. Ultimately over $200 billion was spent with an estimated revenue of only around $10 billion. Certain Western countries such as Denmark and Germany tried to engage in subtle and non-disruptive protests such as posing in the starting XI lineup with their mouths covered, yet drew backlash as the team and federation turned a blind eye when German star Mesut Ozil spoke about the racism he experienced for his Muslim faith and Turkish background. A number of European captains planned to wear rainbow-colored armbands as a protest to the anti-Gay laws in Qatar, but swiftly backed out when FIFA officials threatened them with yellow cards as punishment.

Alexander Hassenstein/Getty Images

When asked about the number of deaths, Qatari officials acknowledged that there were three deaths in the buildup to the World Cup, but eventually said there were between 400-500 when pressed further, which is a still a gross underestimate of the lives of migrant workers lost in Qatar.

As part of my undergraduate thesis, I travelled to Nepal to conduct ethnographic work and interviews with these migrant workers who were in the process of obtaining visas for migrant labor to Gulf Countries and those who had returned from working in these places. As if reading about all these atrocities and watching several expose documentaries was not disheartening enough, talking to these people who were vulnerable (and in many ways manipulated), I felt like I wanted to do something about it besides studying what was really going on behind the scenes. Awareness doesn’t do too much when you’re dealing with arguably the single largest collectively shared, simultaneous human experience - the FIFA World Cup with its hundreds of billions of dollars in capital investment.

I found that the operation of migrant labor for these types of global mega-events were rooted much deeper than they seem. Especially in economies that were vulnerable and malleable, the geopolitics of exporting labor were a significant portion of ensuring a growing economy at the cost of the lives of those at the bottom of the socio-economic hierarchy. Approximately 1/3 of Nepal’s GDP is remittances - money that gets sent back home by Nepali workers abroad. This meant that the hundreds of thousands of workers going abroad (and thousands of them dying) were not a coincidence but part of an oiled machine. Airlines, healthcare companies, banks, and a number of other industries all relied on the exportation of migrant workers to operate and make a profit. Returning from my travels at the Kathmandu airport, I really got a glimpse of how important the labor exportation economy was. There were three designated lines at the exit visa area: 1. Nepali nationals, 2. Foreign Nationals, 3. Migrant workers. I had never seen that third designation at any airport I had been to; to put in perspective, that migrant worker line was by far the longest line whereas the other two were practically empty.

Picture by Pratik Nyaupane

The profit, however, meant that these workers (mostly young men from impoverished families and very low education and literacy rates) would arrive in foreign countries such as Qatar to have their passports confiscated, pay withheld, and forced to live and work in unsafe and unsanitary conditions. As I talked to many of these workers, they were simply trapped in this inhumane operation, not just by their employers, but by the governments and agencies designated to support them.

Sam Tarling/Corbis via Getty Images

But there is also no denying that to many like me, the FIFA World Cup is the ultimate form of emotion, family, and connection. I spent hours each day watching every minute of every match for a month. My phone was blowing up with notifications in the half a dozen group chats I was in alongside several other friends who were texting me about every goal, controversial play, and nail-biting moment. Almost everyone who has watched soccer in the last 30 years has grown up watching Lionel Messi play and cementing his stature as one of the greatest athletes to have lived, winning every trophy eligible besides the most difficult one of them all - the World Cup. I found myself singing Argentinian chants while standing in line at the store while witnessing videos of hundreds of thousands of people in every corner of the world, such as those in Bangladesh (a country that also exported thousands of laborers to Qatar), stay up until 4 am to watch Argentina’s historic run.

Embed Block Add an embed URL or code. Learn moreArgentina fans in Bangladesh as Argentina won the World Cup. Via @robiulhossainn. pic.twitter.com/U980TLiagi

— Roy Nemer (@RoyNemer) December 19, 2022

For every soccer fan and Argentinian, this World Cup will be a moment they will never forget. Millions of people in Buenos Aires flocked to the streets at the same time as thousands filled Times Square and other town squares across the world to celebrate. My grandmother in Nepal told me she couldn’t sleep because people were shooting off fireworks all night with excitement over Argentina’s first world cup victory in 36 years. Clearly the passion of the sport of world football takes over the world. , whether it be watching a match or engaging with social media content.

It has now been over two months since the World Cup ended, and we are forced to ask the question: were those moments of joy worth the thousands of deaths of workers and the abuse and trauma of hundreds of thousands more? Obviously, not.

The geopolitical and economic power of sporting governing institutions such as FIFA and the International Olympic Committee are expanding more and more. I argue that these are full governmental bodies themselves and harness enough power to override the sovereignty of many nations and human rights of billions. It has been evident that with the joy surrounding football can be used for good, however these organizations are able to act recklessly without oversight and accountability for their own profit and power.

The FIFA Women’s World Cup is less than 150 days away, and the next men’s tournament is being hosted in the US, Canada, and Mexico in 2026. I do believe that sports can be enjoyed by the masses without there being violent harm, displacement, labor exploitation, and death, but the playing field is uneven with institutional and political power on the sides of those who merely seek profit. I don’t know the simple answer. But what I do know is that there are already a number of human rights, labor rights, migrant rights, and other advocacy groups that have been relentlessly fighting against the harm that these events cause. Now, it really is abilities as individuals to engage through collective action to hold officials and bad actors (who are greenlighting these detrimental operations) accountable to ensure that that we can prevent these grave injustices from occurring in the future.

BiographyPratik Nyaupane is a doctoral student at USC Annenberg, where he focuses on research broadly relating to technology, inequality, and social and political movements. As an early career scholar, his work explores how various groups utilize and perceive technology as a means of political power. His recent projects consist of studying surveillance capitalism on university campuses and researching environmental justice groups’ utilization of technical practice and citizen science initiatives. His work is grounded in the needs and concerns of communities that are subject to systems of oppression. Prior to joining USC, he graduated from Arizona State University summa cum laude with a B.S. in Informatics and a minor in Political Science.

How Omegaverse Came to Dominate Fanfiction, and Why That Might Not Be Such a Bad Thing

The following post was created as part of the assigned work for Henry Jenkins's PhD seminar, Public Intellectuals. The goal of the class is to help communication and media studies students to develop the skills and conceptual framework necessary to do more public-facing work. They learn how to write op-eds, blog posts, interviews, podcasts, and dialogic writing and consider examples of contemporary and historic public intellectuals from around the world. The definition of public intellectuals goes beyond a celebrity-focus approach to think about all of the work which gets done to engage publics -- at all scales -- with scholarship and critiques concerning the media, politics, and everyday life. Our assumption is that most scholars and many nonscholars do work which informs the public sphere, whether it is speaking on national television or to a local PTA meeting.

Header image attribution https://foto.wuestenigel.com/women-writing-on-paper/

One of my favorite things to explain to strangers at parties is the omegaverse. More often than not, young women and gender non-conforming people hear that title and immediately burst out in laughter; they already know what I’m talking about and are excited to see someone react for the first time to one of the oddest—but somehow incredibly popular—phenomena on the internet.

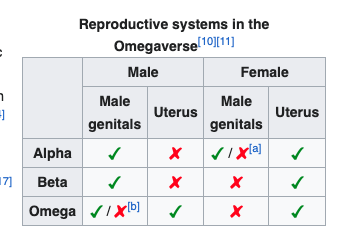

At parties, I explain omegaverse in hyperbole. I say, “Okay, it’s a world where everyone is either an alpha, beta, or omega. Alphas have massive penises that knot—yes, like a dog,” I pause here while my audience laughs, “and omegas can get pregnant. Anatomy varies, sometimes they’re intersex, sometimes they just have vaginas, and sometimes they can get pregnant through their ass? I guess?” I pause here again for all the delighted, fascinated questions (Wikipedia has a helpful chart explaining some common anatomy configurations—see Figure 1). “But they always have some form of self-lubrication; that’s called slick. No, I’m serious! People love this shit!”

figure 1

And then, I pull up Archive of Our Own and show them this.

figure 2

There are over 165,000 pieces of literature in this universe—that’s 10,000 more than there were when I wrote my first draft of this post, only two weeks ago. Then, I open TikTok. TikTok has banned the tag #omegaverse, but it’s still widely discussed in my corner of the app. @icaruspendragon has even made a social media career off of explaining the nuances of omegaverse to her 315,000 followers.

This post, simply explaining how the aforementioned knot works, has over two million views. The omegaverse has started to leave the more close-knit and insular spaces of fanfiction and entered romance publishing; even The New York Times wrote about one author’s attempt to copyright omegaverse, and Lindsay Ellis’s video essay on the same topic has already racked up over 3.5 million views.

Omegaverse may not be hitting the mainstream any time soon, but awareness of the trope is no longer limited to the few—or not so few—actively engaging in fanfiction communities. However, as I and all the people laughing with me know, omegaverse is weird, but it has a lot more nuance than I can generally explain at parties, as well as a long history in fandom.

The first official stories using omegaverse terminology popped up in the early 2010s in the fandom adjacent to the TV show Supernatural, except they focused on the actors, not the characters. Jensen Ackles was the first omega, and Jared Padalecki was the first alpha. Some of the tropes that are common in omegaverse go back further, too. Star Trek’s concept of the Vulcan mating cycle, pon farr, lines up well with the omegaverse idea of heat, and fans have been finding ways to get men pregnant in their fanfiction since at least 1988.

@oldmythos I love that I had to get access to a university archive to read this AND I DID #PepsiApplePieChallenge #fic #ao3 #omegaverse #mpreg #history ♬ Lofi - Domknowz

But that’s just the problem with omegaverse for a lot of people: it almost always focuses on men. 84% of the omegaverse fanfiction on Archive of Our Own is tagged M/M, or slash, meaning it focuses on the relationship between two men. Except, in this universe, one of them can also get pregnant. In the early discourse around omegaverse within fandom, this trope was pretty widely seen as a bad thing. I remember reading through conversations on LiveJournal where fans I looked up to talked about how misogynistic it was, how it removed women from the universe. Fathallah (2017) quotes a fan’s comment on an omegaverse fic: “‘I love these AU’s where women seem to die off or don’t exist and men can have babies,’” (p. 73). Omegaverse is also often based in incredibly patriarchal systems in which alphas literally and biologically own omegas; rape and dubious consent are also common to the trope. In place of women, omegas—again, often omega men—become the victims of gendered violence and all forms of oppression. To quote one of my students, “it just recreates heteronormativity and misogyny, but more and worse.” This just begs the question: what makes omegaverse so popular, and should we be worried about it?

Fans in 2023 have had over a decade to hone their criticisms of the practice, even as it has grown. The problem is no longer just misogyny but transphobia as well. Fans argue that omegaverse writers have created an entirely new universe to avoid writing about transgender men, who can get pregnant in this universe, the one we live in. It creates a new type of gender essentialism; in omegaverse, sexes are signaled not only by appearance and genitalia but by unescapable scents. An important caveat here: male omegas are still men in omegaverse. They are almost always addressed with he/him pronouns, and if they do in fact bear children, they are often still called “father.” Omegaverse allows for a separation of sex and gender, in which reproductive organs don’t necessarily determine if you are a man or a woman or any other gender. Reproductive organs do, however, determine social and hierarchical statuses in these invented societies.

All of this is true, and they are all valid criticisms. Why then, does it remain so popular amongst fans, who are often queer women and gender non-conforming people? We don’t want to live in a world where our gender identities are re-prescribed in new ways, and we don’t want to live with the constant threat of sexual violence like omegas often do in our fanfictions.

Popova’s (2021) article “Dogfuck Rapeworld” (title referencing a self-satirizing meme fans use to talk about omegaverse) argues that the writers, often women, create power imbalances in order to explore them and warp traditional sexual scripts. In her construction, it creates a new layer of intimacy that exists for the sake of romance and kink. It becomes a space of exploration for intimate and sexual desire, one that removes the potentially triggering reality of sexual violence on women’s bodies.

Fans use omegaverse to explore the deepest violence of cis-hetero-patriarchy through non-real, alien, invented anatomies; not just the kinks. Kelsey Entrikin has a fantastic dissertation on the subject through the queer lens, but I first came to this realization as a long time, avid reader and writer of the trope. In omegaverse, omegas live in the most oppressively gendered society imaginable. They’re often not allowed to work, kept as sexual slaves, and bound by heat cycles that periodically make their lives miserable. They’re sometimes dramatically smaller than alphas and have overwhelming weaknesses to things like an alpha’s scent or command. And yet, omegas survive and find ways to work the system.

Sometimes, omegas work their way through society by hiding their status. Sometimes, they kill their captors and escape sexual slavery. Sometimes, omegas create intimate and sexual relationships with other omegas in order to keep themselves safe from alphas. In my own fanfiction, I’m interested in how omegaverse functions under capitalism, how labor and wage inequalities might be rectified in a world that is even harsher than our own.

Dystopian science fiction can take us to the worst edge of the current world and ask what if? Sometimes it’s through a climate apocalypse, or a nuclear disaster, or after a collapse of capitalism, but these ideas all explore the looming problems of real life. In omegaverse, writers take us right to the worst parts of cis-hetero-patriarchy; they reject the world we live in in order to explore the complications of sex, gender, and sexuality more deeply. They ask what if? in a way that allows not only complex looks at how things like reproductive rights function but also indulgence and enjoyment. Right next to a rant about inequality, there is full on erotica.

Omegaverse plays with some of the most problematic facets of gender and sex. Returning to my wise student’s words, omegaverse “recreates heteronormativity and misogyny, but more and worse”; but that’s the point. It turns up the dials on problems that deserve attention, and fans use that to say something, even if they don’t know what they have to say yet.

When I explain omegaverse to strangers at a party, I don’t tell them about the nuanced representations of gender and power; that’s not what makes people read a work of literature, at least not if they’re reading for fun. Even so, omegaverse makes those arguments. People can read for indulgence and come out hyper-aware of facets of society they might not have been paying attention to. Radicalization and joy are a powerful combination (even if they came together through wolf porn).\

BiographyYvonne Gonzales is a PhD student at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, where she studies fan culture and transformative fiction. She earned her bachelor's degree in English at UC Berkeley. Her research focuses on the connections between fan subcultures and the larger patterns of culture that create and maintain fandoms.

March 20, 2023

Elder Orphans: A Hard Knock Life?

The following post was created as part of the assigned work for Henry Jenkins's PhD seminar, Public Intellectuals. The goal of the class is to help communication and media studies students to develop the skills and conceptual framework necessary to do more public-facing work. They learn how to write op-eds, blog posts, interviews, podcasts, and dialogic writing and consider examples of contemporary and historic public intellectuals from around the world. The definition of public intellectuals goes beyond a celebrity-focus approach to think about all of the work which gets done to engage publics -- at all scales -- with scholarship and critiques concerning the media, politics, and everyday life. Our assumption is that most scholars and many nonscholars do work which informs the public sphere, whether it is speaking on national television or to a local PTA meeting.

It’s a hard knock life for us

It’s a hard knock life for us

’Stead of treated

We get tricked

’Stead of kisses

We get kicked

It’s the hard-knock life

After the world went nuts over Jay-Z’s 1998 hit single, “Hard Knock Life (Ghetto Anthem),” Charles Strouse, the composer of the original song from the musical Annie that Jay-Z sampled, was asked for his reaction to it. Aside from being a little worried about all the “swears” and use of the “N-word,” the Broadway veteran liked it and said, “In some areas, there's parallel thinking between me and Jay-Z...'Hard Knock Life' had to reflect the fact that the kids in the story were underprivileged and exploited."

Jay-Z didn’t share Strouse’s point of view about the grubby band of orphans singing about their sorry lot in life, saying, “They ain't singing that song as if they sad about it. 'Ok, this is our situation. We gonna make the best of it,’ and went on to say:

“You know, I knew how people in the ghetto would relate to words like, 'Instead of treated we get tricked' and 'Instead of kisses we get kicked'…It's like when we watch movies we're always rooting for the villain or the underdog because that's who we feel we are. It's us against society. And, to me, the way the kids in the chorus are singing 'It's a hard-knock life' is more like they're rejoicing about it. Like they're too strong to let it bring them down. And so that's also the reason why I call it the 'Ghetto Anthem."

You can watch “It’s a Hard Knock Life” from the original 1982 film version with Carol Burnett and Albert Finney above, or you can watch the later 2014 version with Cameron Diaz and Jamie Foxx (although if you love musical theater, I recommend avoiding the later version like the plague, as you will never be able to unsee Cameron Diaz’s performance as Miss Hannigan).

Where am I going with this, you ask? Well, first of all, Jay-Z’s “Hard Knock Life” is a great song, so if you’ve never heard it, you’re welcome.

Second, I think we can learn from his point of view about the resilience and strength of the underdog when it comes to growing old on one’s own, and on what it means to be an “elder orphan” in America.

Helen Dennis and I wrote about the somewhat unfortunately named “elder orphans” in a book chapter on retirement:

“The term ‘elder orphans’ is referred to in gerontological circles as ‘aged, community-dwelling individuals who are socially and/or physically isolated, without an available known family member or designated surrogate or caregiver.’ An alternative term ‘solo agers’ was recently introduced by author and life planning coach Sarah Zeff Geber. Geriatricians, gerontologists, retirement planners and others concerned about older adults aging alone are focused on the ‘acute’ issues solo agers may face, such as making plans for what would happen should they need legal guardianship or become incapacitated with no one to advocate for them.” (Dennis & Marnfeldt, 2021)

It’s true, growing older without a family support network has the potential to put people in vulnerable situations. A quick Google image search will tell you what the world thinks growing older alone looks like—apparently a lot of looking out the window:

figure 1

The thing is, being a solo ager is not rare and is even becoming the norm. A 2020 survey by the AARP found that 12% of people in the United States over the age of 50 live alone, are un-partnered, and have no living children. Living alone also increases with age, especially for women who have a longer life expectancy, and are typically partnered with someone older than themselves to start with. In a 2021 profile of older Americans published by the Administration for Community Living, 20% of men and 33% of women over the age of 65 lived alone.

figure 2

Profiles of “kinless elders” that often emerge in the press are exemplified in this December 2022 New York Times article, “Who Will Care for ‘Kinless’ Seniors?” by Paula Span. Most coverage of older adults in the mainstream press emphasizes a decline narrative, whether it’s a decline in health, mental capacity, or social capital. A more positive narrative is one of resilience and resourcefulness.

In Span’s article, two kinless older women, Lynne Ingersoll, a 77-year-old retired librarian, and Joan DelFattore, a retired English professor, are featured. Both women arrived kinless in elderhood, one by choice, the other by circumstance.

Ms. Ingersoll didn’t know she was on a path to become an elder orphan. The path only became clear in retrospect as she slowly outlived her parents, her partners, her pals and her pets.

“My social life consists of doctors and store clerks—that’s a joke, but it’s pretty much true,” she says now, as she manages to take care of herself, despite multiple debilitating health conditions.

figure 3

A contrasting profile to Ms. Ingersoll’s is one of Joan DelFattore, a woman who deliberately fashioned her life to become an elder orphan. She said she knew from a young age that she didn’t want to be a wife or a mom, and she knew she preferred living alone. With that, she says she “went about constructing a single life.” The retired professor is healthy, still engaged in her work as a researcher and teacher, and has a wide circle of both personal and professional social connections.

figure 4

Ms. Ingersoll would presumably argue that she too “constructed” her life based on her preferences as a younger woman the same way Prof. DelFattore did. She didn’t want to live alone, and yet she does. She had no children, but she had three life partners over the years who all predeceased her.

She’s living the hard knock life of an elder orphan in her later years due to many things out of her control. She can take care of herself now, but in a year or two or five, who knows? Where will she live, and will she be able to make that choice for herself?

In 2016, a survey of an Elder Orphans Facebook group was conducted among over 500 of its 10,000+ members aged 55+. It found that 45% of its members had lived alone for 20 years or more, with 42% saying they lived alone just because they wanted to.

In a section of the survey on vulnerability, respondents were asked if they believed they could take care of themselves as they aged. Answers were pretty equally distributed across three buckets—those who said definitely yes (28%), those who said probably yes (35%), and those who were hedging a bit with “maybe/maybe not” (33%).

Asked about their top choice for where they want to live as they age, it comes as no surprise to those of us in the field of aging and gerontology that almost 50% of the Facebook elder orphans say their wish is to remain in their own home, with another almost 30% adding a more detailed version of that, saying they want to live in a “Tiny affordable house in a village of people like you.”

figure 5

Only 2% said their top choice was to move in with another family member, and just 1% said they wanted to rent a room in a home they shared with someone else. A surprising 12% said they’d choose “affordable” assisted living.

I say surprising because they keep using that word—“affordable”—and I do not think it means what they think it means because there is virtually no “affordable” assisted living in the United States, unless you have a minimum of $3,000 bucks a month to spare and want to live in one of the Dakotas.

And yet, I get it.

Keeping the “affordable assisted living” myth alive is far better than contemplating a terrifying possible future where a kinless elder might have no alternative but to be placed in the modern day equivalent of an orphanage for older people—a nursing home.

It’s not a stretch to think that older adults are more freaked out than usual about the possibility of being placed in a nursing home, given what we’ve lived through over the last three years. From the start of the COVID-19 pandemic through January 2022, over 200,000 residents and staff in nursing facilities in the U.S. died, and the death rate for people living in nursing homes was more than 23 times the death rate of people over age 65 who did not live in nursing homes.

Two hundred thousand people dead. What’s an elder orphan to make of that?

Maybe, like Jay-Z, elder orphans have metaphorically revised the “Hard Knock Life” lyrics in their heads?

It’s a hard knock life for us

It’s a hard knock life for us

No one cares for you, a smidge

When you’re in an orphanage

That’s probably too optimistic for most budding elder orphans or other reality-based individuals. They probably think more like Tracey Pompey. Ms. Pompey, a nurse’s aid for 30 years who believes she lost her father due to neglect in a nursing facility, said:

People get desensitized to things like this…

If it happens to a child or a dog, people won’t shut up.

figure 6

The people in the elder orphans Facebook group are probably more aligned with Ms. Pompey’s sentiments, as they understand the risk of the social (and literal) death they face being orphaned in late life.

I wonder if their mindset is less Jay-Z and more Killer Mike in the 2017 “Hummels & Heroin” episode of South Park, where he voiced the original song, "They Got Me Locked Up In Here.”

The episode is a parody of the opioid epidemic set against the nursing-home-as-prison paradigm that was as salient in 2017 as it is today and probably will be in 2050. The first stanza ends with nursing home placement as indictment:

🎶 They got me locked up in here

They got me locked up in here

And I’m sitting, doin’ hard time

Pissin’ in a metal bowl

Eatin’ shit from a lunch line

(They got me locked up)

In here, nobody knows you by your name

You just a number

Livin’ under bitch-ass rules of a broken game

They put me here to die,

Left me angry and alone

For the crime of being old

They threw me in this nursing home

Jay-Z’s “Hard Knock Life” from 25 years ago was about rooting for the orphan kid, the underdog, in an “us against the world” vibe that felt at once cautious but hopeful. Killer Mike’s rendition of the orphaned elder is decidedly more dark and hopeless but also reflective of what many people believe to be true.

Contemplating this harsh reality made me reach for Jay-Z again and his 2009 single, “Young Forever” from the “Blueprint 3” album, in which his optimism is unfettered by caution:

🎶So we live a life like a video

When the sun is always out and you never get old

And the champagne’s always cold

And the music is always good

And the pretty girls just happened to stop by in the hood

And they hop their pretty ass up on the hood of that pretty ass car

Without a wrinkle in today

’Cause there is no tomorrow

Just some picture perfect day

To last a whole lifetime

And it never ends

’Cause all we have to do is hit rewind

So let’s just stay in the moment

Smoke some weed, drink some wine

Reminisce, talk some shit, forever young is in your mind

Leave a mark that can’t erase, neither space nor time

So when the director yells cut we’ll be fine

Ah Forever young

Sometimes we need to cling to “forever young” in our minds to escape from hummels and heroine, but, most days, it’s just a hard knock life for us.

Biography

Kelly Marnfeldt is a doctoral candidate at USC’s Leonard Davis School of Gerontology, where she also received her Master of Science in 2019. Her research interests broadly include the impact of caregiver burden, the meaning of justice for victims of elder abuse, and the intersection of vulnerability and autonomy for people living with dementia who wish to age in place in their communities.

March 17, 2023

A Glimpse into the Brain-Bending Way We Appraise Health Information

The following post was created as part of the assigned work for Henry Jenkins's PhD seminar, Public Intellectuals. The goal of the class is to help communication and media studies students to develop the skills and conceptual framework necessary to do more public-facing work. They learn how to write op-eds, blog posts, interviews, podcasts, and dialogic writing and consider examples of contemporary and historic public intellectuals from around the world. The definition of public intellectuals goes beyond a celebrity-focus approach to think about all of the work which gets done to engage publics -- at all scales -- with scholarship and critiques concerning the media, politics, and everyday life. Our assumption is that most scholars and many nonscholars do work which informs the public sphere, whether it is speaking on national television or to a local PTA meeting.

Since the early days of newspaper printing in the United States, mass media and public health scholars have observed spikes in the prevalence of mis/disinformation related to major public health advancements, including the discovery of immunizations, the introduction of water fluoridation, and the implementation of tobacco regulations. While the problem of mis/disinformation is not new, the advent of social media has magnified the reach and impact of unverified and harmful health information. The cost has never been more visible than it is today, amid a global pandemic that has claimed more than 6.5 million lives, disproportionately affected communities of color, and erased decades of women’s progress in the labor market.

Despite the toll of the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccine hesitancy remains a significant public health challenge, and it’s only one of many health arenas plagued by uninformed or misinformed decision-making. To make sense of it, let’s begin with some of the sources that produce mis/disinformation, putting aside for a moment the personal and cognitive attributes that make someone susceptible to fake news/conspiratorial thinking.

Increasingly, junk science is being introduced through various digital media sources. One recent study found that 36% of U.S. adults cited the internet as their most common source of health information (roughly half cited their health professional, and a third cited television). Alternative medicine websites, such as NaturalNews.com, serve as examples of online worlds that promote false and misleading claims to millions of users through a network of 200+ interlinked websites, such as VaccineHolocaust.org and Healthfreedom.news. In more sophisticated cases, peddlers of false health information employ a common yet insidious tactic – embedding a kernel of truth within layers of spurious claims. The single piece of truth serves to lend credibility to a series of unfounded connections.

Take, for example, the Brownstone Institute, which positions itself as a nonprofit “think tank” staffed with credentialed academics and physicians. In one recent Brownstone article called “Have the Children Been Poisoned?” the article’s author claims that the use of masks and hand sanitizer lead to toxic poisoning of children (spoiler: this is not true). Upon further evaluation, more skeptical readers will find that the Brownstone Institute is a special interest group comprising anarcho-capitalist physicians who have been condemned by the U.S. medical establishment and reprimanded by their respective state medical boards.

figure 1

Now let’s return to the question of personal susceptibility: why do some people stop to question the claim that face masks poison children and others don’t? What underlying skills, competencies and biases allow some people to sail past junk science and others to capsize? One piece of the answer is media literacy, or one’s ability to “access, analyze, evaluate, create and participate with messages in a variety of forms” (Center for Media Literacy). In this context, numerous studies examining the relationship between media literacy and health beliefs have consistently shown that low levels of media literacy are linked with greater susceptibility to digital mis/disinformation. There is also a body of evidence that shows an independent linear relationship between low functional literacy (i.e., basic reading and writing skills) in adults and poor health outcomes, including higher rates of hospitalizations and mortality. Translation: If you struggle to understand what your doctor is saying, or you can’t follow the instructions on your prescription bottle, you’re probably less likely to achieve positive health outcomes.