Henry Jenkins's Blog, page 6

May 20, 2024

WrestleMania XL: The Greatest Story Ever Told (Part One)

By Tara Lomax and Mark Williamson

This is the first of three parts on the recent WrestleMania XL and the current revival of WWE. It reviews the interconnected and multistrand storytelling that unfolded over two years leading into the recent event and highlights opportunities for further appraisal. This first part establishes the important role of audience and character in pro wrestling, and overviews key moments for Roman Reigns leading into WrestleMania XL. The second part reflects on long form serialized storytelling in WWE and introduces the story of Cody Rhodes. The third part explores the blurring of reality and fiction that drives pro wrestling storytelling and the role it played in the lead up to WrestleMania XL. Readers who might be interested in this piece include those new to pro wrestling within the context of popular culture and entertainment studies and those curious about WWE’s revival. Italicized text denotes wrestling terms.

World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) is in the midst of a revival. This rejuvenation of WWE is a result of new ownership (Endeavor purchased WWE in 2023 and formed The TKO Group with UFC), new creative leadership (Paul ‘Triple H’ Levesque became Chief Content Office [CCO] in 2022), and the return of ‘The American Nightmare’ Cody Rhodes at WrestleMania 38 (2022). WWE’s renaissance has emerged over the past two years and follows a period of economic and creative decline for the company (largely driven by the pandemic but not entirely), so this resurgence is welcomed by the wrestling business and the WWE Universe (its fanbase); it is also significant for the entertainment industry and its study because it shows what can be achieved when creators reconnect with the distinctiveness of the medium, its history and its audience. Over three parts we will explore the significance of WrestleMania XL (2024), the serial storytelling that led to the event, and its affirmation of a new era for WWE and professional wrestling.

What is Professional Wrestling?Professional wrestling – or pro wrestling – is a form of live storytelling that revolves around staged combat in a wrestling ring, otherwise called “the squared circle”. In this form, storytelling emerges through the blurring of reality and fiction as pro wrestlers adopt archetypal personas (gimmicks) and form rivalries based on two principal character roles: the babyface (or face) and the heel. These roles are often understood as protagonists (or heroes) and antagonists (or villains) that are associated with storytelling more generally, but the function of these roles is more nuanced in pro wrestling: the babyface and the heel are defined by a relationship with audience.

While it might be easy to simply label the babyface as a heroic ‘goodie’ and the heel as a villainous ‘badie’, this does not quite account for the distinct relationships that form between babyfaces and heels and how the audience can influence these characters and their stories. A heel can be morally ‘good’ and still be a heel if they deny the audience something, or a babyface can behave immorally and be cheered, as with the double turn of Bret ‘The Hitman’ Hart and ‘Stone Cold’ Steve Austin at WrestleMania 13 (1997). Heels can still be very popular, despite their presentation, as with ‘Rowdy’ Roddy Piper, Ric Flair, Austin, and The Rock. Pro wrestlers can also move back and forth between these roles based on booking (match and story producing) and audience response. A face that gets a pop and a heel that gets heat signal a successful synergy between the audience and the story (inside and outside the ring).

For most mainstream commentators, pro wrestling’s “fakeness” is a shroud that obscures appreciation of its distinct storytelling qualities and medium specific conventions. This idea of “fakeness” in relation to pro wrestling is really about an ambiguous relationship between fiction and reality, which can be a complex dynamic to manage creatively. WWE storytelling occupies this ambiguous threshold between the real and the scripted through distinctive character types, cause and effect driven by staged (not fake) combat, serialized narration, and audience participation. This is all exemplified by the road to WrestleMania XL.

What is WrestleMania?WrestleMania is an annual event produced by WWE (formerly WWF) that began in 1985. It is the flagship event of WWE programing that all premium lives events (PLEs) – formerly pay-per-views (PPVs) – revolve around. Historically, each year the “Road to WrestleMania” begins at the Royal Rumble; since WrestleMania XL celebrates the event’s 40th anniversary, this event also culminates 40 years of WWE history. It is also the first WrestleMania without a member of the McMahon family running WWE.

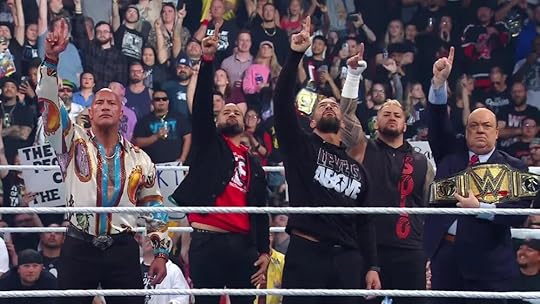

Image 1: WrestleMania XL held at Lincoln Financial Field in Philadelphia (April 6-7, 2024)

Taking place in Philadelphia over two nights on April 6 and 7 2024 and live streamed internationally (image 1), WrestleMania XL broke records including highest attendance and Peacock’s most-streamed entertainment event. According to CCO ‘Triple H’, it is “by every metric the biggest WrestleMania of all time”. What made this WrestleMania so notable is that it was built on a Main Event invested in serialized storytelling that harnessed its relationship with audience. This story is about the babyface, ‘The American Nightmare’ Cody Rhodes – son of the pro wrestling legend, ‘The American Dream’ Dusty Rhodes – finally defeating the long-reigning heel, ‘The Tribal Chief’ Roman Reigns, who is a member of the Anoa’i family and descendent of the great Samoan wrestling dynasty that includes The Rock. Over three parts, this piece explores key moments in this story and its culmination at WrestleMania XL. This part focuses on the story of Reigns, the next part will explore the key moments for Rhodes and the final part will discuss the inclusion of The Rock in the final stage in the story of WrestleMania XL.

Video 1: WrestleMania XL (2024) teaser trailer

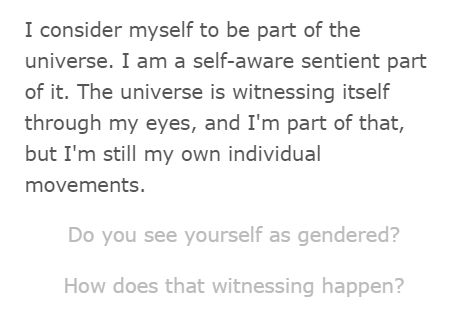

Roman Reigns: Heel, Champion, ‘The Tribal Chief,’ ‘Head of the Table’Going into WrestleMania XL, Roman Reigns had been champion for 1316 days with the help of his manager ‘The Wise Man’ Paul Heyman and his faction ‘The Bloodline’. Over his reign, he developed a reputation for being manipulative, narcissistic, ruthless, and sadistic; his behavior resembled a crime boss more than a pro wrestler, as he ordered ‘The Bloodline’ – his family – to attack opponents and interfere in matches. Through these tactics, Reigns defeated all who challenged him, including Daniel Bryan, Finn Bálor, John Cena, Goldberg, Rey Mysterio, Edge, Randy Orton, Brock Lesnar, Drew McIntyre, Kevin Owens, Sami Zayn, Logan Paul, and Cody Rhodes – the best of the WWE roster. Reigns built an empire around this domination and demanded that all of WWE acknowledge him as ‘The Tribal Chief’ and leader of WWE (Image 2). By all accounts, Reigns as ‘The Tribal Chief’ exemplified the most archetypal version of the heel as ‘bad guy’, but what the climax of WrestleMania XL reveals is the story of a man broken down by a history of insecurity, betrayal, and rejection.

Image 2: ‘The Bloodline’ (L-R: The Rock, Jimmy Uso, Roman Reigns, Solo Sikoa, and Paul Heyman) and the WWE Universe (the fandom) acknowledging Roman Reigns as the ‘The Tribal Chief’ on Smackdown (March 1, 2024).

Reigns was previously a member of a babyface faction called ‘The Shield’, together with Seth Rollins and Dean Ambrose. ‘The Shield’ had been in a feud with ‘The Authority’, a heel faction principally made up of ‘Triple H’, Vince McMahon, and Stephanie McMahon with associate members including Orton, Kane, and Batista. ‘The Shield’ broke up on Raw in 2014 when Rollins joined ‘The Authority’ after hitting Reigns in the back with a steel chair and making a heel turn (video 2). This is a linchpin moment in Reigns’ story that will continue to repeatedly haunt him.

Video 2: Rollins hits Reigns with a chair on Raw (June 2, 2014).

Over the years that followed the break-up of ‘The Shield’, Reigns was booked as the top babyface of WWE, to mixed audience responses. His appearances at major events, including the Royal Rumble (2015), WrestleMania 33 (2017), and the “Raw after Mania” (2017), were met with loud groans – this was not heat for a heel, but a rejected babyface (video 3).

Video 3: Reigns is booed on Raw (April 3, 2017)

This fraught relationship with the audience continued until 2018 when he announced a break from WWE to treat leukemia (which he had been battling privately for 11 years prior). His return in 2019 was met with some cheer, but he was still not fully embraced as a leading babyface. This points to a further dimension in the relationship between storytelling and audience in pro wrestling: the perception of audience agency and story causality. It was not necessarily Reigns himself who the audience rejected, but the consistent presentation of him as an unstoppable babyface, despite their vocal disapproval.

Like with all forms of live entertainment, the pandemic put WWE and WrestleMania at risk of collapse: WrestleMania 36 (2020) took place in the WWE Performance Centre where the only fan in sight was a ceiling fan. During this period, WWE trialed multiple ways to simulate the audience or facilitate their remote engagement, from the digital faces of the ThunderDome to piped-in sound, but it remained clear that pro wrestling is nothing without a live audience (image 3).

Image 3: (Left) WrestleMania 36 (2020) in an empty WWE Performance Centre; (right) Digital faces of the ThunderDome.

For Reigns, the coronavirus outbreak posed a higher health risk and so he took a five-month hiatus, which allowed him to also reassess his career and consider retirement. During WWE’s time of crisis, Reigns fortunately returned with a new heel attitude and a manager, Heyman (Image 4). In his return match at Payback (2020), he won the WWE Universal Championship in a “Triple Threat” match with ‘The Fiend’ and Braun Strowman (image 5).

Image 4: Reigns returns with Heyman on SmackDown (August 28, 2020)

Image 5: Reigns (with Heyman) wins the WWE Universal Championship at Payback (2020)

After years of resisting the audience’s disapproval, the heat was now in sync with booking intensions. Reigns had fully embraced his new heel role, to the point that he would inflict brutal violence on his own cousins – twins Jey Uso and Jimmy Uso – to show his dominance and make them subservient. At Hell in a Cell (2020), Reigns forced Jey Uso to surrender in their “I Quit” match by choking his brother Jimmy Uso and so ‘The Bloodline’ and Reigns as ‘The Tribal Chief’ were born (Video 4). Reigns would go on to reinforce his dominance in a feud with Lesnar to also win the WWE Championship in a “Winner Takes All” Main Event at WrestleMania 38 (2022) to become the Undisputed WWE Universal Champion (image 6).

Video 4: Reigns defeats Jey Uso at Hell in a Cell (2020)

Image 6: Reigns becomes Undisputed WWW Universal Champion at WrestleMania 38 (2022)

The development of ‘The Bloodline’ involved multiple story angles and archetypes, as Sami Zayn was introduced as the outsider looking for protection and Solo Sikoa (The Uso’s younger brother) took on the role as sadistic enforcer. Bestowed with the title of ‘Honorary Use’ to recognize this allegiance to ‘The Bloodline,’ Zayn was driven to prove his loyalty by sacrificing his long-term friendship with Kevin Owens at Survivor Series: WarGames (2022). This loyalty was put into question again: in the aftermath of Reigns defeating Owens in the Main Event at the 2023 Royal Rumble, Zayn was ordered to bludgeon Owens with a steel chair; instead, Zayn picked up the chair and – harking back to Rollins in 2014 – hit Reigns in the back, thus ending his allegiance with ‘The Bloodline’ (video 5). While pro wrestling is principally concerned with simulating combat sport, the gangster melodrama quality of the ‘The Bloodline’ story intensified pro wrestling as a serialized soap opera.

Video 5: Zayn hits Reigns with a steel chair at Royal Rumble (2023).

Image 7: Elimination Chamber (2023) poster.

Zayn’s involvement with the ‘The Bloodline’ played a major role in boosting the story’s popularity: it elevated Zayn as a babyface and amplified Reigns as an unstoppable heel. Next to Reigns’ brutal dominance, Zayn represented the underdog and everyman – there was a sense that he had qualities that might just be what was needed to defeat Reigns. However, this hope was lost when Reigns defeated Zayn in his hometown of Montreal in the Main Event at Elimination Chamber (2023) (image 7). Leading into WrestleMania 39 (2023) it became clear that WWE needed a superhero to defeat Reigns (more on this in Part Two).

Tara Lomax is the Discipline Lead of Screen Studies at the Australian Film Television and Radio School (AFTRS). She has expertise in blockbuster franchising, multiplatform storytelling, and contemporary entertainment and has a PhD from the University of Melbourne. She has published on media franchising, the superhero and horror genres, entertainment industries, transmedia storytelling, and stardom. Her work can be found in publications that include the Journal of Cinema and Media Studies (2024, forthcoming), Senses of Cinema and Quarterly Review of Film and Video, and the edited books Starring Tom Cruise (2021), The Supervillain Reader (2020), The Superhero Symbol (2020), Hannibal Lecter’s Forms, Formulations, and Transformations (2020), The Palgrave Handbook of Screen Production (2019), and Star Wars and the History of Transmedia Storytelling (2017). She is on the Pop Junctions editorial committee.

Mark Williamson has over twenty years of experience as a performer, promotor, producer and commentator in Australian professional wrestling. He has booked wrestling promotions including International Wrestling Australia (IWA) and Warzone Wrestling, and produced the series Underworld Wrestling (2018-2019), which streamed on Amazon Prime Video (2018-2022) and is now available on Tubi. As a pro wrestling manager, he worked with former pro wrestler and now WWE Raw General Manager Adam Pearce. More recently he has explored the creative opportunities of pro wrestling storytelling through comic books and audio platforms.

April 24, 2024

Moving Between World(views) with Database Narratives

Great transmedia storytelling shows me that a single piece of media is just one limited window on a larger world. It invites me to imagine a universe that extends far beyond what I can see on screen or understand directly through the text. Telling multiple stories in the same universe, across different media formats, demonstrates that each character, place, or point in history presents just one out of many possible perspectives. To develop our own perspective, we take on board these different points of view and imagine what might exist out there that connects it all, a kind of “blind men and the elephant” exercise

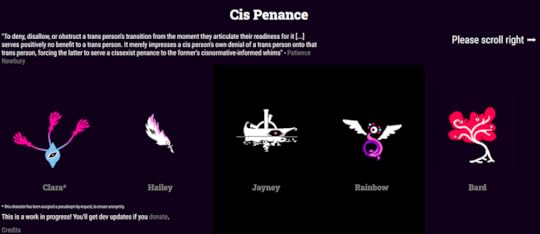

In my chapter in Imagining Transmedia, “Cis Penance: Transmedia Database Narratives,” I discuss my own interactive documentary work about transgender people (specifically, a piece called Cis Penance: Trans Lives in Wait), in terms of concepts that come from Japanese media studies scholarship: database narratives and sekaikan (worldview). These can be considered alongside related concepts such as “storyworld” and “cinematic universe”.

Database narratives (or “database consumption”) is a concept introduced by Hiroki Azuma in the 2001 book Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals to describe a way of relating to media products that had become very prominent in Japanese otaku culture by the late 1990s. To take a well-known example, each Pokémon game, anime, movie, and other media extension contributes to a larger picture of the storyworld, establishing an overarching fictional reality through the narrative device of the Pokédex—though database consumption does not require this kind of in-world database. Database narratives or database consumption can also be observed in Star Trek, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the Hellaverse of Hazbin Hotel and Helluva Boss, and many more.

Rather than pointing to a singular, overarching “grand narrative” associated with modernism, in database consumption each person creates their own internal database of associations with a storyworld. Although “database” does not refer to a media object in itself—Azuma’s database is a metaphor for an imagined cognitive rendering of a storyworld inside a fan’s head—fan wikis are interesting texts to refer to when making sense of a database narrative, and represent an effort to negotiate a shared metatextual reality with other fans. Azuma’s argument is that otaku do not just consume the text of a particular piece of media, but more broadly consume the world that it portrays: its “sekaikan”.

I am generally grumpy about the introduction of loan words from Japanese into English, because their acquired meaning in English will inevitably come to differ significantly from their associations in Japanese. Part of this is due to the same inevitable semantic drift that plagues all language, but it may also be exacerbated by a strong tendency to exoticise “the Far East”. From “ikigai” to “katsu curry”, we just don’t seem to be able to resist making Japanese words into something they are not.

With that said, I find sekaikan legitimately useful, because it does point to something that is not quite captured by its English and German equivalents (worldview and Weltanschauung, respectively). Sekaikan is not just a set of beliefs about a world, but also how a world is portrayed in a piece of media. In English, we think of worldview as a philosophical position that “underlies” a work, a prior cause from which our narratives emerge. Sekaikan can mean this, but it can also refer to the outcome of a set of creative decisions. Rather than betraying the auteur’s underlying values, the creative process can itself produce a sekaikan, as part of its aesthetic effect. A worldview is something I have, but a sekaikan is something I try to create.

It might also be worth noting that when translating from Japanese to English, you often have to infer from context whether a noun is singular or plural, and whether to apply “the” or “a”. When we talk about worldview, we assume that the “world” in question is the consensual reality that we share with every other living being—there is only one “real world” with reference to which our worldviews are formed. Sekaikan is more freely used to describe how a fictional world is portrayed, independent of any beliefs the authors may have about the real world. Is the sekai of sekaikan “the world”, “a world”, or (many) “worlds”?

Another linguistic pleasure I get from “sekaikan” is that the character that translates to “view” is homophonous with another common suffix that translates to “feeling” or “sense of” (e.g. 疎外感 sogaikan, (feeling of) alienation; or 親近感shinkinkan, (sense of) affinity). Sekaikan does not mean “world feeling”, but it almost feels like it could (perhaps in another world?). Of course, here I’m doing the very thing that frustrates me about loan words—I’m making the word into something it is not, simply because it supports my own sensibilities and interests.

Just as we can construct database narratives about fictional worlds, I think we do the same about our own societies. I came to understand what it means to be a genderqueer person and a transgender man because I encountered the stories of other transgender people, through meeting people in LGBTQ+ community spaces, watching documentaries made by other trans people such as Fox Fisher’s My Genderation project, exploring trans people’s blogs and video-blogs, and playing indie games in the early years of the queer games movement. Each individual story contributes to a larger reality—a world in which gender identity exists independently of sex assigned at birth, gender dysphoria causes significant distress that one might only recognise after unlearning lifelong dissociative habits, and gender euphoria can be experienced by trans and cis people alike. Each testimony adds to my own internal database of things it is possible to feel, be, see and do.

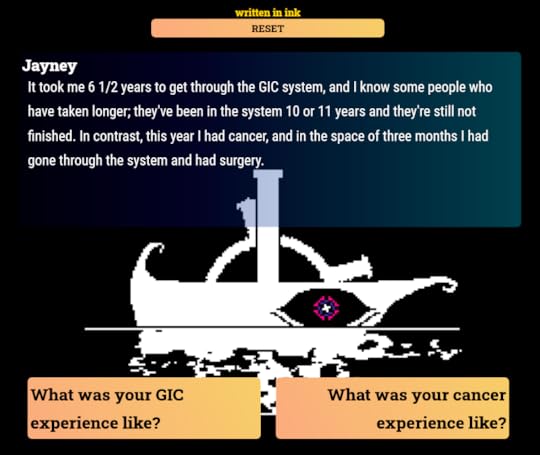

This construction of a sekaikan in which trans lives are possible was part of the purpose of my own work creating interactive documentaries based on oral-history interviews with transgender people. My first such work was created in 2018, when I was an artist in residence in Tokyo with a programme supported by the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs. I interviewed transgender people in the Kansai and Kanto areas, and turned each transcript into an interaction with an on-screen character. All the text attributed to that character came verbatim from one of the interviews, but to keep the interaction loop short I invented questions that the user could choose from, employing an interaction pattern seen in many role-playing games.

credit: Zoyander Street

Since 2019, I have been working on a piece much larger in scale, based on 45 interviews with transgender people across the UK. I’ve had the pleasure of collaborating with trans artists whom I have admired for many years: for example, the character designs are by June Hornby (a.k.a. Critterdust), who previously created a game called Earthtongue that has you manage an alien terrarium; and the music is by Liz Ryerson (a.k.a. Ellaguro), who has heavily influenced my own worldview on digital art through her vast body of work across indie game development, music, criticism, visual arts, and podcasting.

credit: Zoyander Street

My hope is that Cis Penance initially overwhelms the player with the sheer number of characters, who are arranged as though they are all waiting in line for something. My starting point was thinking about one of the differences between my own worldview and my mother’s: while I’m a leftist of a fairly radical bent, my mother is staunchly opposed to communism and socialism alike, because of her own experiences as the child of Ukrainian immigrants who came to the UK after World War II. I remember the image of the breadlines of eastern Europe as a key example of the failures of socialism in my mother’s worldview. For me, the breadline is not a quality of left- or right-wing economic policy, but of systemic failure more generally.

While the breadline is something that can be observed and portrayed clearly on-screen, other policy failures produce queues that are hidden in bureaucratic systems. National Health Service (NHS) waiting lists are a key example of this in the UK, caused not by socialism but by neoliberal austerity. I and almost every British trans person I know have experienced excruciating waiting times, putting our lives on hold in many ways as we wait for essential medical care to alleviate our gender dysphoria. Very few people will ever see an NHS waiting list on a screen, but if you speak to enough trans people, you start to feel its weight, like an invisible force pressing in on our community. This is just one example of the waiting that characterises our experience—there is also the slow progress of hormonal transition itself, and the socially imposed waiting that pressures us to delay our transition until some arbitrary point in the future (“You’re too young to know, what if you regret it?” or, “Can you at least wait until your children are grown up, this will traumatise them!”)

credit: Zoyander Street

credit: Zoyander Street

However, as I spent more time with other trans people, I also noticed that there is another side to trans people’s altered relationship with time. We have experienced first-hand that the linear life path that cisheteronormativity assumes everyone will follow is arbitrary. Many of us experience transition as a second adolescence; at the same time, we may feel old before our time, as rapid cultural changes and a lack of LGBTQ+ elders push us into the position of being the wise older trans person. A lot of trans people are neurodivergent, which may include neurological differences in our experience of time itself (for example, ADHD can involve impaired perception of time, and dissociative conditions can cause us to lose time). Trans experiences of spirituality can also alter our understanding of time, space, and consciousness. Talking to many trans people can hint at a sekaikan in which time is more fluid. This connects with concepts from queer theory, such as “chrononormativity”, “heterotemporality”, and “queer time” (and “crip time”, from disability studies and crip theory).

By presenting a large number of characters for the player/user to interact with, I hope to contribute to a database narrative about transgender ways of being and seeing, and give people (cis and trans alike, because not all trans people have access to a larger trans community) a window into an expansive sekaikan, and perhaps an expansive worldview. Transmediating oral testimonies into videogame characters invites people into a context where they accept that they do not know everything about how this world functions—in videogames, you build up a database narrative about the storyworld in a bottom-up manner, rather than imposing top-down assumptions. Perhaps if we could learn to more readily do this in our own consensual reality, we might give people more space to define themselves for themselves.

credit: Zoyander Street

More recently, I have shifted my practice from interactive documentary to interactive online theatre performance. Part of this is because my own relationship to time has shifted following a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. It’s not that I was so bold as to think that I wouldn’t develop a chronic illness—somehow, every queer person I know has ended up chronically ill by their mid-thirties, and I am exactly the kind of person who would burn themself out so much that their immune system ends up attacking their own brain. I knew something like this would hit me, but somehow I still thought that I had time to build my art practice incrementally, until eventually I could reach my larger goal: creating interactive ethnographies about aliens sent to Earth to study the reality that humans have socially constructed. Now that I’m operating on “crip time” (working more slowly, but also having less time to reach my larger goals), I have had to find a way to skip ahead directly to the weird stuff.

Whereas Cis Penance is transmedia in the sense that it transmediates oral testimony into videogame characters, and into a live experience for users, my new project Intrapology connects more directly to the kind of transmedia storytelling that has become familiar through expanded universes, particularly multiverses in which characters move between parallel worlds. In Intrapology, I take social constructivism literally, to the point of absurdism—each world exists directly and only as a result of social consensus. When a fundamental difference in worldviews occurs, this causes a physical rift in reality itself, and what was once a shared world splits into two smaller, separate worlds.

One of the distressing things about our present historical moment is the pervasive sense that we do not all occupy the same world. Some people describe our times as “divided”, but I find that language too neutral, suggesting that the issue is our failure to all “just get along”. The concept of “epistemic injustice” is more instructive. I experience this as a transgender person: every time I am misgendered, I am reminded that I do not exist in other peoples’ worldviews the same way I exist in my own and those of the people who care about me. My own testimony about my life and experience is worth very little to someone who simply believes that their view on the world is correct, and mine is deluded.

Through transmedia database narratives, I can hold onto a little hope that we can do something to make the world more bearable for one another. In a situation where modernist grand narratives can no longer be relied upon to shape social consensus, and we are all constructing our own worldviews in a bottom-up manner, it is easy to feel hopeless and lost. But I think that by learning how to communicate a sekaikan, we can develop the capacity to contribute to epistemic justice, by inviting others into the worlds we have had the joy and privilege to explore.

BiographyZoyander Street is a freelance artist-researcher with a PhD in Sociology from Lancaster University. They work on a variety of projects spanning disciplinary boundaries, including theatre with game-like interactions and games for gallery spaces. Their work has been shown around the world, including London, Berlin, Tokyo, Chicago, Vancouver, and Arizona.

April 22, 2024

It’s All Transmedia Now

This post is part of a series written by contributors to Imagining Transmedia , a new book of essays published by the MIT Press. The book explores how transmedia techniques are being used in a wide range of settings, from entertainment and education to health care, journalism, politics, urban planning, and more.

Our stories are getting more complicated all the time. Not in terms of plot or character, per se, but in how we find them and share them. It’s almost a requirement that the stories we tell now live in multiple places, from social media platforms and little screens to the pages of books and magazines, and then back to big screens for film and television. Even writers of novels and popular nonfiction books perform a carefully calibrated version of authorhood and curate communities of their fans online as assiduously as any other type of “influencer,” from lovingly designed Zoom backgrounds to artfully crafted social media posts and laboriously maintained Substacks. Every middle schooler I know today sees creativity as a tech-infused, multidimensional process that involves making and sharing work across many different tools.

Academics came up with a special word in the 1990s to describe this kind of storytelling: transmedia. It needed a special word because at the time, it still felt unusual to see the deliberate construction of a storyworld, a community of shared imagination, across multiple media. But over the past few decades, everything has become transmedia. How do we think about stories and what it means to imagine a world together when the pathways for telling, sharing, and reacting to those stories are constantly shifting and bleeding into one another? When that shared narrative universe is massively distributed, debated, and collectively infused with the energy and attention of thousands or millions of people?

These are the questions at the heart of our new book Imagining Transmedia, the culmination of over a decade of intensive mucking about in transmedia storytelling at the Center for Science and the Imagination at Arizona State University. I’d like to tell you a story about how we got here.

Origins and Stories

When we launched the Center for Science and the Imagination (CSI) in 2012 at Arizona State University, there were many uncertainties. Would an outfit with the mission of “inspiring collective imagination for better futures” make any sense at a research university? How would CSI actually advance that mission? And most important of all, how were we going to navigate the issue that while everyone agrees that we need imagination, nobody really knows what it is?

“Participants engage in a recent futures thinking exercise at ASU’s Center for Science and the Imagination”

But we did know a few things, and arguably the most important was this: storytelling matters. I am a firm believer in the proposition that humans are storytelling animals: that we understand and navigate the world primarily through stories. We tell stories about who we are, about the past and the future, and even stories edited on-the-fly, continually, inside our brains, about what is happening right now. Magicians and politicians know how telling the right story can completely shift one’s experience of reality. And so it follows for CSI that if you want to change the future, you need to change the stories we tell about the future.

We pursued this approach with gusto, bringing together science fiction writers, scientists, engineers, and many other creative and technical experts to collaboratively imagination hopeful, technically grounded futures. Since 2012 we’ve published more than 20 book-length works of speculative fiction and nonfiction, nearly all of them available for free on our site or through open-access editions with publishers like the MIT Press. These projects tend to focus on the areas where our failures and crises of imagination feel most acute: climate change, AI and automation, and the societal consequences of the pandemic, for example.

But amidst these excellent themes arrayed like jewels in the CSI display case, there is one eternal wellspring of imagination, one relentlessly relevant, unstoppable juggernaut of an idea that can’t stop, won’t stop: Frankenstein.

We got into the Frankenstein business ten years ago when my colleague Dave Guston pointed out that the world would soon be celebrating the bicentennial of Mary Shelley’s remarkable novel. We worked together to get a planning grant from the National Science Foundation and support from ASU for a graduate researcher. The next thing you know, nearly a hundred scholars, artists, writers, and researchers were brainstorming ways to celebrate the anniversary through performances, books, art-science experiments, and much more.

“Art by Nina Miller”

The deeper I got into Frankenstein, the more I came to realize that Mary Shelley created a transmedia phenomenon two centuries before anyone had any idea what that meant. Think about it: even if you have never read the book, you know this story. You’ve seen it in one or more of the hundreds of screen and stage adaptations, in the endless references in comic books and art, in music videos and live performance, or branded on breakfast cereals and lunch boxes. Most importantly, it’s a story that most people, at least in the global north, think of with a sense of shared ownership. Anyone can lurch around like Boris Karloff in a Halloween costume, or write their own ending to the book.

Frankenstein is a story about creativity and responsibility: taking ownership for your actions, being a good parent, loving your monsters. It’s also a story about storytelling, a meditation on how reading and language shape us. Almost as soon as the book was published in 1818, it was ripped off for stage productions and published in translation around the world. In just a few short years Frankenstein’s monster had become a metaphor that could be deployed in political debates and newspaper cartoons. It was a story you could tell in any and all media. And so it’s fitting that our Frankenstein project has become a never-ending story, a beautiful, shambling creature that continues to disgorge new research papers, theatre projects, and, well, blog posts.

Transmedia Now

So it is a beautiful thing that our Frankenstein Bicentennial Project gave birth to another assemblage of big ideas and bold questions: Imagining Transmedia. This book only has one chapter on Frankenstein itself, but the whole anthology takes on the Pandora’s Box that Mary Shelley opened when she published her amazing novel: how do the stories we tell together shape our reality?

Imagining Transmedia tackles this question at a time when transmedia is no longer an esoteric critical term or a media strategy that only a mega-corporation could afford. Just about every story we tell now is constructed using transmedia logics: played out through multiple platforms and channels, using digital technologies that allow multiple audiences to share a storyspace, an imagination space, and make it their own. Taylor Swift is a transmedia phenomenon, weaving together her personal and professional history, long-term engagements with her fans, easter eggs and double meanings, into a fully immersive experience that plays out across concerts, albums, social media, documentaries, press coverage, the Super Bowl, and a significant fraction of all the brain cells and molecules contained within a sphere of radio waves that began expanding outward from Earth into the universe in 1989.

The book’s not about Taylor Swift either (sorry). But it is about the world in which celebrity like Swift’s is possible, the world in which only this kind of celebrity is possible. We are all transmedia storytellers now, living our lives in the shadow of thousands of digital reflections of ourselves shared intentionally or created through surveillance capitalism. For storytelling animals, stories are the building blocks of reality, and so the turn to ubiquitous transmedia has profound implications for politics, shared culture, even shared reality. Conspiracy theories like QAnon thrive on fluid and ephemeral transmedia storyworlds. We have become so used to the blurred lines between fiction and reality that we are at risk of losing the plot.

I don’t see those blurred lines as a cause for despair, but as an invitation. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the zenith of transmedia happened shortly before the arrival of generative AI. The large language models we see today powering ChatGPT and other such tools are deeply rooted in the principles of transmedia: meaning and connections can be found anywhere, from photos to math problems to forum posts. Build a thick enough web of connections and context, and you can create a system that spouts out plausible new connective tissue on the fly. One challenge we will have to grapple with in the years to come is how to differentiate between authentic human-human communication and a world wide web filled with more and more machines talking to one another. Technologists already fret that future generative AI tools will be inadvertently trained on the output of other machines. These systems only work if they are fed real human creative output and fall apart quickly when their own outputs become inputs.

The same could be said for humans, of course, and while the darker sides of contemporary transmedia are indeed scary, I think we’re capable of developing the new literacies we need to navigate a world where stories can live and travel just about anywhere. Ultimately, that’s a question of imagination, and recognizing when other peoples’ stories in the world are trying to colonize our own imaginative minds. Building some resilience and independence into our relationships with media—an imagination immune system, if you will—is one of the most important tasks ahead. I hope our new collection can be a start, by calling out the changing shape and rising stakes of transmedia in a world that is, more than ever, made of stories.

Ed Finn is the founding director of the Center for Science and the Imagination at Arizona State University, where he is an associate professor in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society and the School of Arts, Media and Engineering. He coedited the books Imagining Transmedia (2024) and Frankenstein: Annotated for Scientists, Engineers, and Creators of All Kinds (2017), and is the author of What Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of Computing (2018). Website:https://edfinn.net

March 20, 2024

“Girl Crush” K-pop Idols: A Conversation between Korean, Chinese, and US Aca-fans Part II

This piece is a continuation of a conversation started in Part I.

Donna:

In addition to Mulvey’s writing, Kavka’s (2020) work on “fuck-me” and “fuck-you” celebrities can be a useful lens to the fan perceptions of Girl Crush K-pop artists. Your discussion of HyunA’s overtly sexual yet “‘I don’t give a fuck’ attitude” (p. 20) resonates with Kavka’s discussion of subversive (sexual) agency in some contemporary female celebrities:

“the inversion of fuck-me to fuck-you implies a reversal of (sexual) agency, in the sense that I am doing the fucking, while, on the other hand, the rhetorical force of the ‘fuck you’ serves as a statement of resistance and resilience, a rejection of the feminine fuckability standards that aims to foment a revolution against them.” (p. 19)

Although in HyunA’s case, it is arguable that her sexiness—although in a non-conventionally overt form—still conformed to traditional standards of female attractiveness and was supported by major media complex’s conventional production system.

HyunA - Red (2014) (Source: YouTube)

Other Girl Crush idols/artists can also be approached through this lens, too, particularly the transition from more “oppa”-focused girl idols to “me” or “unnie”-focused girl idols. However, the notion of “fuck-you” celebrity requires some adaptations around how desirability is performed by Girl Crush K-pop idols that we discussed so far: reclamation of agency may be present but overt “fuckability” or romantic desirability can be absent, hidden, or deferred (e.g., fourth generation girl groups) or appear in forms that are reasonably interpretable as conventionally conforming to the male gaze (e.g., HyunA). Some of the contextual factors for this would be that K-pop exists in a relatively sexually conservative culture than (Western) pop music spheres and that innocence and youthfulness tend to be considered as desirable traits (which coincides with the typical age range of idols). Therefore, de- or subtler sexualization, especially if accompanied with less direct criticisms on gender inequities, may indicate a more malleable self-positioning rather than a radical subversion from “fuck-me” to “fuck-you,” strategically open to interpretation: are these expressions of feminist subjectivity, or are they just being cute—i.e., acceptably subversive?

This involvement of interconnected conventional media production systems in the making of K-pop idols is perhaps what makes Girl Crush K-pop an exceptionally rich topic. K-pop idols tend to be produced and managed by companies with commercial motivations within the realm of popular music. Conformity to common values and desires of their target audience is expected. Without denying the artists’ own contributions to their idol persona, we must not discount the multi-actor, commercial, and common taste-aware (aka, “Top 100”) production process in the making of Girl Crush idols. This means that at least in the K-pop idol production model, we must be cautious of attributing the idols’ Girl Crush-ability solely to the artist’s unique genius or their fandoms’ subversiveness. Rather, it should be approached as a collaboratively constructed and managed symbolic status, not independent of existing dominant structures (see Banet-Weiser, 2018).

Then, if we are observing shifts, the questions become: What are the (different) ways that the idols can be read, as encoded? Has the target audience shifted, or has its range expanded, and if so, in what ways and why? Can the readings reasonably vary depending on the audience group or would the readings be relatively uniform? How do these readings and groups align with or object to dominant patterns of power? Has there been (or do the answers to the prior questions signal) any changes to common values? Here, I would like to remind us of two things: first, the history of Girl Crush artists in the history of K-pop (i.e., that it is not a “new” trend per se), and second, the contemporary co-existence of girls and women’s empowerment and persisting (or perhaps in some ways exacerbated) anti-feminism in Korea.

I argue that this context, i.e., the infusion of dominant desires, is what makes Girl Crush readings by fans, such as what Lenore described, more subversive. That is, it is not so much that the Girl Crush idols are produced to be read as feminist and urging related social activism (or at least not as overtly coded as so as it may be in more tolerant cultures) but rather that the fans are, although at times with some disagreements, interpreting them as so. It is the fans who both individually and collectively girl crush on the girl crush-able idols, making salient certain readings and associated values, discursively and materially expressed through their fan engagement—which in turn can impact media system’s commercial decision-making processes. So regarding fans, the questions I would like to ask are: What are their understanding of the society? What are their desires, and how are they being realized and expressed through so-called “Girl Crush” K-pop? What have been the personal (including in immediate environments and close relationships), collective, and societal consequences of these realizations and expressions? I am less interested in sleuthing the (hidden) symbolisms and intended (hidden) meanings (e.g., to borrow from Lenore’s reflections, whether Arashi intended to question gender construction). I am more interested in how fans partake in shaping the symbols and meanings (e.g., questioning, subverting, and in ways reproducing existing essentializing gender expectations through their engagement with Arashi).

Crush gains dynamism in its verb form. If the “Girl Crush” can be described as a movement in K-pop, the momentum can be traced in the interaction between girl-crushing fans and crushing gender structures.

Lenore:

I agree with your idea, that fans’ interpretation plays an important role in the process of value building in “Girl Crush”, their participation may empower extra meaning to the original production, and the content will change depending on different audience groups. For example, (G) I-DLE's new song “Wife” has aroused various reactions in China’s K-pop fandom: some think they are showing their compliant attitude towards the social norm, some others see it as an irony to the female stereotype. Some passersby of the K-pop fandom cannot understand what this song is mainly about when reading the lyrics, so fans’ assistance (interpreting video/pictures) is necessary if they hope to build the image of the group and connect them with the feminism. In this perspective, fans’ participation has become a huge driver of “Girl Crush” and even social progress.

(G)I-DLE) - 'Wife' (Source: YouTube)

If we focus on fans and their appeals, like what they want to get or express from “Girl Crush”, we may also notice that most K-pop fans will not see themselves as fan of only one group, which means, they are travelers of the K-pop universe. In this circumstance, they fall in love from one group to another, looking for relevant values from them, gathering together and forming a strength that is hard to ignore. In response to the travelling feature in K-pop fandom, the term “crush” could also have the interpretation from the time perspective: fans get crushes on those girl groups, but they won’t stick to one, they love them momentarily and keep changing the objects to show their value in the long run.

“Girl Crush” is a part of the Korean Wave (Hallyu), which has had great impacts all over the world, and has also exerted influence on Chinese popular culture and social culture since it entered our context 30 years ago (Sun & Liew, 2019). From a transnational perspective, maybe we can extend the theme into relevant topics like cultural differences and acceptance, political attitudes, etc. For example, feminism is seen as exotic and mainly influenced by Western ideology in China, but the “Girl Crush” from Hallyu undoubtedly provides cultural proximity to the Chinese audience, so what changes will it make to our social acceptance of the whole movement? The queerness shown in “Girl Crush”, which was always a gray area in the Chinese context, has been a visible culture in K-pop fandom, what are the factors and the impacts behind it? For a long time, the Chinese government has been trying to build an influential culture that could build up citizens’ confidence and influence the world. What are the differences between these two cultures, and what can we learn from the Hallyu? These are all valuable questions waiting to be solved.

I think I should give a more specific description of queerness in the “Girl Crush” group since it’s part of the meaning of the term. I talked about Moonbyul’s performance earlier, but didn’t fully elaborate:

Moon’s performance also points to the queerness in “Girl Crush” K-pop group, which makes the style so popular in China. In mainland China, the government’s attitude towards the queer community is always seen as ambiguous, they won’t block queer content on social media, and they treat the community with the attitude “No Asking, No Mentioned, No Responding”. To avoid unnecessary troubles, like some aggressive strangers suddenly coming and insulting you when they search the content, queer community tend to use various forms to express their identity, K-pop is one of the forms. Just like Lady Gaga and Jolin Tsai, “Girl Crush” K-pop groups are also important to the queer community. However, one thing that makes it different is that the K-pop group seldom stands out and supports the queer community in public. So, as Donna said, fans’ participation has empowered the K-pop production of various meanings, and in “Girl Crush” K-pop, it is not only about feminism, but also queer sexuality. In Shin’s (2018) article, she mentioned female fans crossplay as BTS and cover their performance, especially the soft masculinity shown by some male stars, and tomboy-style female stars—whether it is fan practice or the idol company’s strategy, they all show non-binary sexuality of K-pop and its fandom. In this case, maybe Hallyu with such great power, will change what it means to be queer in Asian culture and promote social progress with other strong cultural powers.

Henry:

This has been a great discussion and sheds a lot of insight onto the political impact of this important K-Pop movement. I was struck while I was in China how many of my young female students knew and cared passionately about these groups, how many had developed interpretations about what they were saying through their music videos especially, and why their messages were so vital as resources for them.

I had been struck while I was there about the performance of hyper-femininity I was seeing on the streets of Shanghai, how often the women I saw were dolled up in ways that I see much more rare in the United States these days. I also was struck by how much those women who opted out of that system of gender performance stood out in this context. Some women seemed to be making conscious choices not to wear make-up, to wear more gender-neutral clothing which would not be out of place on an American college campus. This choice seems to me almost an act of courage, and it was in this context that I first encountered {G]Id-le as my point of entry into the Girl Crush movement. Strikingly, because of their positioning in the media industry, the female performers themselves rarely made these same choices in their presentation, though a song like “Tom Boy” did seem to speak to their fans who were carrying their self-empowerment much further into this space.

For the most part, the men I spoke with young and old seemed oblivious to these debates about gender that were taking place amongst women. For the most part, they claimed not to know [G]id-le or “Tom Boy.” When I showed the video to one man in his early 40s, he described the group as dressing like dominatrix which suggests how threatening (or kinky) their gender performance felt to him. It was this gap between how they were being read by women and men in Chinese culture which first interested me. This is what reminded me of the debates we used to have when I was in graduate school about the Madonna videos as they were coming out, as she embraced a more empowered view of feminism, as she both attracted and critiqued the male gaze, as she made more and more direct expressions of queerness and support for gay rights. Today we can see her mainstreaming certain ideas that were bubbling up from more underground groups like La Tigre and appropriating voguing as a subcultural practice from the NYC queer scene.

I am reminded of what John Fiske wrote about the young Madonna fans at the time: "The teenage girl fan of Madonna who fantasizes her own empowerment can translate this fantasy into behavior, and can act in a more empowered way socially, thus winning more social territory for herself. When she meets others who share her fantasies and freedom there is the beginning of a sense of solidarity, of a shared resistance, that can support and encourage progressive action on the microsocial level." Retrospectively, we can see how Madonna helped pave the way for the Riot Grrls and how their street activism became third wave feminism. Could the Girl Crush movement have a similar impact in Korea and China?

March 18, 2024

“Girl Crush” K-pop Idols: A Conversation between Korean, Chinese, and US Aca-fans: Part I

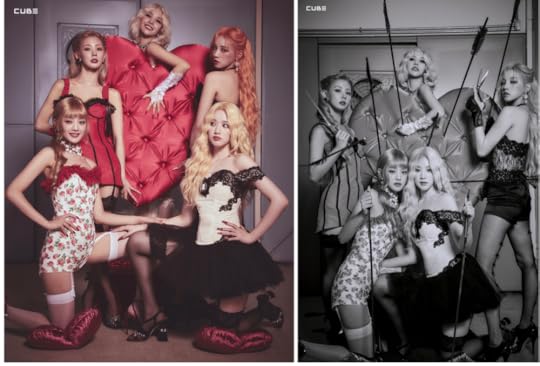

(G)I-DLE. “Nxde” Concept Photos (Source: Cube Entertainment)

Henry:

During my recent trip to Shanghai, I was introduced -- by Lenore -- to the music videos of [G]I-DLE and taken by the ways they seem to echo the themes and some of the style I associated with Madonna videos from the 1980s and 1990s and that some of my students here have compared to the Gwen Stefani videos of the early 2000s. I was struck by the quality of discussions they were generating among the young women of Lenore's generation in China and the ways they functioned as vehicles for popular feminist concepts from South Korea to enter into the conversations about gender in urban China. In my investigations since, I have learned that [G]I-DLE is technically considered part of the "Girl Crush" movement in K-Pop. So, I invited Lenore to join us for a conversation with Donna, who is one of my former students, who is Korean and does work on, among other things, Korean feminist and popular culture. These developments are not as well known in the west as they should be. I was hoping, Donna, you could give us a bit of a big picture of what this movement is about, how [G}I-DLE fits into it, and how these videos are being understood at the point of their production in Korea. Since many readers will not necessarily know these groups, this context may help everyone to better understand the discussions which follow.

Donna:

Let me zoom out from (G)I-DLE. Perhaps a bigger picture on the “Girl Crush” trend would help. This will inevitably be long. Many female K-pop idol groups have been successful in the 2020s, from newly debuted ones (aka “fourth generation” idols) to those who returned after a hiatus. Many of their lyrics focus on topics such as being a strong woman, self-confidence, and self-love rather than those that innocently seek love from (supposedly) male listeners. In other words, they are “me”-focused rather than “you (traditionally male listeners)”-focused. For instance, (G)I-DLE sings in TOMBOY (2022):

“Do you want a blond Barbie doll? / It's not here, I'm not a doll (like this if you can)….Your mom raised you as a prince / But this is queendom, right?”

IVE’s Love Dive (2022) parades great admiration for themselves, drawing on the Narcissus mythology. All translations are by me:

“Narcissistic, my god I love it / 서로를 비춘 밤 [the night that we shone on each other] / 아름다운 까만 눈빛더 빠져 깊이 [beautiful black eyes fall more deeper] / (넌 내게로 난 네게로) [(you into me I into you)] / 숨 참고love dive [hold breath love dive]”

LE SSERAFIM emphasizes their agency and passion for their career in ANTIFRAGILE (2022):

“무시 마 내가 걸어온 커리어 [don’t overlook my career path] / I go to ride till I die die .... 멋대로 정하네 나란 애에 대해 [decides however they want the person I am] / I don’t know what to say I can’t feel it / 뜨거운 관심은 환영 귀여운 질투는 go ahead [fervent attention welcome cute jealousy go ahead] / 줄 달린 인형은 no thanks 내 미랠 쓸 나의 노래 [string puppet no thanks my song that will write my future] / Yes gimme that”

LE SSERAFFIM - “Antifragile”. (Source: YouTube)

Beyond K-pop, female talents’ careers and “strong,” “independent” women personae are becoming more recognized and celebrated in the broader South Korean media industry. Kim Sook, has gained nicknames like “Sook-crush (drawing on “Girl Crush”),” “Furiosook (parody of Mad Max’s Furiosa)” and “Matriarch-sook” from her famous gender role-flipped humor and non-subservient image that she built over ~25 years of her career, became the second woman to ever win Korea’s national broadcasting station’s (KBS) Grand Prize in Entertainment in 2020 since Lee Young-ja’s first win in 2018. Female street dancer crew reality competition series Street Women Fighter (Mnet; 2021-2023) and many of the featured dancers have become sensational hits. As the series’ name suggests, the “Girl Crush” dancers boasted “strong” physiques, personalities, and styles but with comradery and professionalism that matched their (formerly underrecognized) diverse and impressive career backgrounds, rather than one-dimensional “catty” competitiveness.

Kim Sook’s “matriarch” comedy. Caption: “The best man is a man who carefully and gently does housework.” (Source: YouTube)

An example of a more explicit crossover with K-pop would be Refund Sisters, a temporary project group from TV variety show “Hangout with Yoo” (MBC) that consisted of four top female pop divas across generations of K-pop Uhm Jung-hwa (1993 debut), Lee Hyori (1998 debut; first generation idol group Fin.K.L member who became a national icon after solo debut in 2003), Jessi (2005 debut; amassed great popularity from Mnet’s 2015 female rapper competition show “Unpretty Rapstar”), and Hwasa (2014 debut; third generation idol group Mamamoo member). The group name originates from the joke that advocating for oneself (e.g., asking for tricky refunds) would be easy with the support of its fierce, confident members. Their single DON’T TOUCH ME (2020) celebrates their successful careers as “strong” women in K-pop:

“Trouble 이래 다 그래 [everyone says I’m trouble] / 세 보인대 어쩔래 [says I look strong so what] … 불편한말들이 또 선을 넘어 [uncomfortable words cross the line again] / 난 또 보란 듯 해내서 보여줘 버려 [as if to show off I accomplish again and show off] / 나도 사랑을 원해 [I want love too] / 나도 평화가 편해 [peace is easy for me too] / 하지만 모두가 you know [but everyone you know] / 자꾸 건드리네 don’t touch me [they bother me don’t touch me] … I don’t care yeah yeah / 내 맘대로 해 [I do as I please]”

Refund Sisters - Don’t Touch me. (Source: YouTube)

As the group composition of Refund Sister and their respective debut year suggests, the presence of “strong,” “Girl Crush” women figures in K-pop is not new (e.g., BoA - Girls on Top (2005); 90’s “strong unnies”). “Sexy female warrior” had been a historical trope that served as an alternative to the cute, innocent, and “girlish” presentation. The same goes for K-pop idols. A step more advanced from “sexy female warrior,” second-generation idol group 2NE1 (2009-2016) was considered groundbreaking during the era with their independent, less male gaze-centric self-presentation. With members at the time who were perceived as less conventionally beautiful (cf., their song Ugly (2011) captures internalized gendered lookism in Korea), 2NE1 confidently sang in studded outfits and experimental hairstyles.

“Ha-ha-ha-ha 다신 널 비웃지 못하도록 [Ha-ha-ha-ha so that they can’t laugh at you anymore] / Now let’s 춤을, 춤을, 춤을 춰요, want to get down [Now let’s dance, dance, dance, want to get down] / 보다 큰 꿈을, 꿈을, 꿈을 꿔 세상은 [dream bigger dream, dream, dream, the world] / 내 맘대로 다 할 수 있기에 큰 자유를 위해[I can do whatever I want for great freedom]” (debut single FIRE, 2010)

Arguably, their songs still tended to be thematically centered around heterosexual romantic love and pursuit. Their global hit I Am the Best (2011) is literally about how they are the best and they feel great being so with many repetitions of the song’s title. However, even this song includes a part where they claim that men take a second look at them and women try to imitate them, after which they mock (contextually presumably male) posers (“playa’”) whose pursuit they reject. Moreover, it should be noted that 2NE1 was considered unconventional. The following are some examples of lyrics from popular second-generation K-pop girl idol groups.

“Hey, 오빠 나 좀 봐 [Hey, oppa (term for older brother and older male acquaintance of similar age range) look at me / 나를 좀 바라봐 [please look at me] … Oh, oh, oh, oh, 빠를 사랑해 [Oh, oh, oh, oh-ppa I love you] / Ah, ah, ah, ah, 많이 많이 해 [Ah, ah, ah, ah, lots and lots] … 오빠 오빠, I’ll be, I’ll be down, down, down, down [oppa oppa, I’ll be, I’ll be down, down, down, down].” - Oh! (2010) by Girls’ Generation

“Tell me, tell me, tell, tell, tell, tell, tell, tell me / 나를 사랑한다고, 날 기다려 왔다고 [that you love me, that you’ve been waiting for me] / Tell me, tell me, tell, tell, tell, tell, tell, tell me / 내가 필요하다 말해, 말해줘요[say that you need me, tell me]” – Tell me (2007) by Wonder Girls

2NE1 - I am the Best (Source: YouTube)

Girls’ Generation - Don’t Touch me. (Source: YouTube)

So yes, I believe it would be appropriate to approach the current trend of idol K-pop as more in the direction of “Girl Crush.” Their overall presentations have been interpreted as targeting “auntie fans” over “uncle fans” (Korean article). Even New Jeans, a fourth-generation girl idol group that does not really have a “strong women” type of presentation, is being interpreted as a youthful group that reminds fans of their innocent teenage years. I think this trend both reflects the rise of feminism in S. Korea (and globally) and the industry’s recognition of these fans’ purchasing power. There is an ongoing social hostility towards feminism in Korea but the current trend in K-pop can be interpreted as the desires for gender equality and diverse role models being more recognized (e.g., Kim Sook’s winning of KBS’s 2020 Grand Prize in Entertainment), albeit possibly in the form of---and supported by the language of---(profitable) “demand.”

Perhaps another factor that allows the creative freedom for this direction would be the emphasis on worldbuilding in fourth-generation K-pop idols. This too isn’t “new” per se as many pre-fourth generation idol groups had historically crafted their own fantasy world to base their group production and storytelling. This also does not apply to all groups. In fact, New Jeans does not draw on fantasy, and (G)I-DLE does not have a set “concept” world as their background. However, many fourth-generation K-pop idols have been more explicitly invested in building a larger interconnected story world and creating songs in accordance with their group’s narrative, with each release being a part of the larger storyline that is to be unraveled, also open to fan participation. Most notably, with Aespa’s debut, SM Entertainment has been weaving together their previous idols’ narratives under their version of the Marvel multiverse, “SM Culture Universe.” If an idol group’s central narrative task revolves around navigating the vast, mysterious “Kwangya (translates to the wilderness)” and fighting “Black Mamba,” seeking oppa’s love is not so important. Similarly, declaring that they are “antifragile” in the fantasy world of Crimson Heart (webcomic version of the group LE SERRAFIM’s worldbuilding) as a character is more risk averse and ambiguous than declaring so against the Korean society’s structural gender inequality as a Korean woman.

Aespa - Black Mamba (Source: YouTube)

This is by no means a comprehensive history of “Girl Crush” movement in K-pop. But I hope this will be helpful for those who are not familiar with Korean entertainment media. A couple of things that may be specifically unique about (G)I-DLE could be that their leader Jeon So-yeon has been directing the course of the group’s activities including overall album production instead of simply performing the songs and that unlike many other fourth-generation idol groups they do not have a structured “concept” fantasy world that they are drawing their inspiration from. My knowledge about the group is not extensive; I would love to hear your thoughts on (G)I-DLE or any other groups that are relevant to this topic, perhaps regarding how global fans are interacting with their content.

Lenore:

Luckily, the K-pop group and TV shows you mentioned in the last letter are also well-known in China. In my following response, I will discuss what may be ‘Girl Crush’ from my own experience and fan practice about it. In my opinion. ‘Girl Crush’ may not just be about the image of a ‘strong female’, but also the spirit and power the idol brings to fans that make them want to follow and even fight against some inequality in society.

When I tried to recall the starting point of the K-pop ‘girl crush’ style that appeared in China, 2NE1 came to my mind too. It was in 2011, 2NE1’s ‘I AM THE BEST’ suddenly became the background music of most of the stores, almost everyone knew how to sing the song even if we didn’t know the meaning of the lyrics. Girl’s Generation’s ‘GEE’, at the same time, was well known for its catchy lyrics and was popular among the young generation. Though both of them were very popular, students took different attitudes to ‘GEE’ and ‘I AM THE BEST’: boys treat the former in a teased attitude, they perform the song to attract other’s attention and hope to see girls perform it in cute style and then mock at them, which leads to girl’s rejection and uncomfortable feeling. Though we didn’t know what ‘male gaze’ was at that time, we knew the meaning behind its popularity among boys and tried to avoid such a situation. The appearance of 2NE1’s ‘I AM THE BEST’ appropriately fits girl’s attitude and dream—we don’t want to be ‘cute’ as they think we should be, we want to be cool and have some ways to show we are. So, though we loved both of them, the latter were performed more frequently by girls. In this stage,’ wanna be cool’ was our core goal to follow the K-pop ‘girl crush’ group.

Chris Lee(Left), BiBi Zhou(Right). Source: Sina Weibo

At the same time in China, BiBi Zhou and Chris Lee are also two popular singers among teenagers (especially girls), both of them are girls but have a neutral appearance and singing style. They are ’Tomboy’ in our parent's mouths, and some parents don’t want their baby girls to pay too much attention to them because they look ’neither male nor female’. Their love songs break through the traditional framework, it did not depict a ‘poor girl who is waiting for her lover’s attention’ anymore, but a teenager who wants to cherish love and time, which definitely aroused many teenagers’ resonance.

HyunA - 'Lip & Hip' (Source: YouTube)

Then HyunA Kim came to the stage center of Chinese K-pop fandom, with her sexy appearance and confident attitude. (I have asked many people whether they think HyunA belongs to the ‘Girl Crush’ category, and most of them said ’no’ but were convinced by me then, so it’s just my stubborn try here. She may arouse some controversy and I would like to hear your views about her.) HyunA is worth discussing, she has more female fans than male fans in China, and there is a rumor that says ’HyunA is a woman who owns overly aggressive beauty, she won’t be welcomed by men here.’ But that is the reason why she was welcomed by female fans, the idea she conveyed to us was ‘Do not feel shy to show your sexyness and beauty.’ These ideas are very important in our society. For a long time, girls tried to hide themselves and look well-behaved, those who wore short jeans and shirts may be criticized by their parents or even be verbally abused as ’slut’ by strangers. Sexy appearance may be a curse at that time. In school, some girls bend their backs to try to make their bosoms not so evident, they lack confidence because of the strange eyes of the environment though it’s physically normal. So HyunA’s sexy confidence influences many of them and creates an image of what they want to be in the future. What is more, though HyunA sings love songs too, some of her songs build a ‘queen’ image. For example, in HyunA’s Lip & Hip (2017), the lyric says (I translated it from Chinese lyrics so it may have some mistakes)

‘ 오늘 내가 Queen queen queen / 내 옆에만 서면 너도 King king king / 날 원하는 남자는 많지만 너를Pick pi pi pi pi pick / 매일 난 솔직하게 표현해 주길 원해 / 마치 네가 네가 아닌 것 같아 / 가끔 난 섹시하게 워킹은 더 당당해 난‘

' Today I am the queen / If you stand by my side you are also the King / There are plenty of men who want me but I pick you / Every day I want it to be honest (to express myself) / Sometimes I need to show my sexy and should be more confident '

Compared with traditional songs, HyunA puts women’s positions higher than men, which reverses the power position in old love songs. So, her ‘sexy’ here may be ‘overly aggressive’ to men, but her uncovered ambition builds a model for girls and encourages them to present themselves. So, the definition of ‘Girl Crush’ here may not depend on whether it is desexualization or not, it depends on the idol's attitude and girls’ feedback about ‘If I should follow her or If she gives me some courage in some aspects’.

蔡依林 Jolin Tsai - PLAY我呸 (Source: YouTube)

Another thing worth mentioning here is that some fans in China remix HyunA's ‘How This ' and Jolin Tsai's ‘Play ’, the remix of them makes the songs more aggressive (to men) because the song conveys a thought like ‘I don’t care about who you are, you are just my prey and toy’. Jolin Tsai is also a ‘queen’ in China. Since the release of her album ‘Myself’ (2010), she highlights and conveys the spirit ‘you should be confident and independent, your yellow skin color is beautiful’. So, the remix of two queens' songs shows the attitude of the fans toward both of them.

Moonbyul - Love & Hate (Source: YouTube)

Moon Byul E (Moon) in Mamamoo is also a representative idol in ‘Girl Crush’ topic. She shows both confidence and a unique charm to the fandom. We call her ’live spanner’ because the spanner could turn the ‘straight' to other shapes, and Moon could let girls love her and imagine her as their girlfriend. In her solo song ‘Love & Hate’(2017), she wears black suit and does the same dance with male partners, which makes her look cool and somehow have a feeling of 'soft masculinity’. Fans also show their love for her voice and temperament in the comment section of the song, I took some sentences from Love & Hate’s Youtube comment section:

‘ Moonbyul is living proof that a woman doesn't need to show skin to be sexy and hot! Love you girl! ‘ (@louisacasella3059)

‘ Every single person in Mamamoo is so talented and have amazing vocals. But Moonbyul's low vocals is something I've never heard among female idol vocalists. It's so unique and I wish she'd get to sing more like in Paint Me. I absolutely adore her voice and Taehyung's voices cause they have alto and baritone vocal ranges respectively in an industry dominated by sopranos and tenors. ‘ (@anishasrikar4996)

So Moon’s ‘Girl Crush’ here is not only 2NE1 and HyunA’s ‘I wanna be like her’, but also a real attraction to girls. I may want to highlight her 'soft masculinity’ here because I was a fan of both Mamamoo and Arashi(Jpop group) at that time. As a Jpop male group, Arashi did not stress idol’s masculinity but wanted male idols to perform femininity to attract female fans, and it worked—the group became one of the most famous idol groups in Asia, and their album '5×20 All the BEST!! 1999-2019’ have won the 'Global Top Album’ award in 2019. (They even exceed Taylor’s ‘Lover’ and BTS’s ‘Map of the Soul’ in this list). Matsumoto Jun in Arashi was called ‘men like flower’ by fans to show his beauty. In Arashi’s success, I have found that women may be more willing to access performers who have femininity than those who have masculinity like Chris Hemsworth, but the paradox here is that though fans love femininity, they also need the reliability provided by masculinity. What may make them win in this step may be the balance of masculinity and femininity, not their physical gender. But when it comes to physical gender, it is obvious that a woman could arouse more empathy and provide more sense of safety than man to fans. So that may be one winning point of ‘Girl Crush’ when compared to those real men who also have 'soft masculinity’, female performers provide reliability and empathy that only belong to the same gender and situation.

(G)I-DLE - 'TOMBOY' (Source: YouTube)

Empathy and resonance are important to ‘Girl Crush’ since we have talked about the importance of ‘wanna be’ and ‘equality between male and female audiences’ relationship’ in it, but just having the same gender is not enough. As a way to rebel against the imbalance and strange eyes of society, girls need an obvious expression that fits their ideas, which is the best part of (G)-Idle. In (G)-Idle’s song, they talked about body anxiety (Allergy,2023), fighting back to the male gaze (Nxde,2022), and trying to break the stereotype of Tomboy and femininity (Tomboy,2022). In their song ‘I want that’, they discuss domestic violence through their performance in MV. We can see that they are not only cool and confident in their appearance but try to use such ways to discuss the inequality in reality, which draws fan’s attention and arouses their resonance. After the release of ’Nxde’, lots of girls (even not fans) use the lyric ‘I‘m born nude, you’ve got a dirty mind’ to fight back against the strange eyes and verbal bullying. So, the expression and the power they express in the song gives those girls the power to say something instead of feeling shy/pretending they are cool/hiding their interests like they used to do before.

(G)I-DLE) - 'Nxde' (LEFT), Madonna - Material Girl (RIGHT)

Another interesting thing about (G)-Idle is their performance in MV, they pay tribute to many famous antecedents and use some bold narrative means to express themselves and tell the stories. In ‘Nxde’,Jeon So-yeon, minnie and Shuhua dress the same clothes as Madonna in ‘Vogue’ and ‘Material Girl’. From Tomboy’s killing a Ken to I Want That’s killing a real men, their rebellions are increasingly obvert. So, I am wondering if K-pop had such direct rebellion before to any societal problem, whether such storytelling form is a traditional expression form or a new form starting from K-pop feminism.

NewJeans 'Ditto' (Source: YouTube )

New Jeans is also a special group in this topic, as you said, they have more ‘aunt fans’ than ‘uncle fans’. In the Chinese context, they may not only be a memory of youth, but also a dream and compensation of it. When they first entered our market, they were labeled as “American high school style," which indicates that the youth they represent is culturally different to us. Most of Chinese students are not allowed to touch cosmetics or fall in love with others before they enter the university. All we should do at that time is to chase a good school performance. Expressing your feelings or fantasies sometimes may bring shame, but the appearance of NewJeans tells us it is normal and your emotion should be well taken care of by your sisters: NewJeans.Even though fans have grown up, they still need such comfort and make up their youth through something that could be seen, imitated, or shown.So in ‘Ditto’, they set up a 'me', who is not anyone in the group, but a high school girl with real emotions, as if the fans were participating in the youth they created for us through the character (like the main female character in the otome game, or maybe we could call it a parasocial relationship). They could be ‘Girl Crush’ too because they create a youth image girls(women) want to be even if they cannot trace back to time and fulfill this dream. The group convey the spirit through their energetic expression and fill the holes in some women’s hearts.

So I have depicted a picture of ‘Girl Crush’ K-pop group in China and try to tell what girls learn from them: from silent avoidance to protesting loudly, from hiding themselves to showing confidently, from a poor girl waiting for love to a queen control the right to choose, it is not only the image transfer on the media, but also some attitudes change in women in the real world. ‘Girl Cursh’ here, is not only ‘ wanna be her ‘, but a channel to gain power and express your attitude. We may don’t need to be a strong woman or pretend to be cool, we could fall in love with others like New Jean’s interpretation of ‘Ditto’, we could show our sexy like HyunA, and we could be what we want to be through the channel.

BiographiesDo Own (Donna) Kim is an Assistant Professor at the University of Illinois Chicago's Department of Communication. She studies everyday, playful digital cultures and mediated social interactions. She focuses on boundary-crossing practices in human-technology assemblages: being together across diverse "real", "online", "virtual", or "imaginary" places, and among the mundane and the weird, the "normal" and the Other. What does it mean to be human in mediated communication environments? How do we want to be together?She received my Ph.D. degree in Communication from the University of Southern California's Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism (2022). Her dissertation—Virtually Human? Negotiation of (Non)Humanness and Agency in the Sociotechnical Assemblage of Virtual Influencers—took a deep dive into boundary crossings in digital reality technology and social media cultures through the lens of virtual influencers (CGI human social media influencers).

Ying Wang (Lenore) is a second-year master’s student in Journalism and Communication at Shanghai University. As a participant in various popular cultures, she explores cosplay, games and online fiction. Her research focuses on participatory culture, especially gender and sexuality in fandom in China.

Henry Jenkins is the Provost Professor of Communication, Journalism, Cinematic Arts and Education at the University of Southern California. He arrived at USC in Fall 2009 after spending more than a decade as the Director of the MIT Comparative Media Studies Program and the Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities. He is the author and/or editor of twenty books on various aspects of media and popular culture, including Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture, Hop on Pop: The Politics and Pleasures of Popular Culture, From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: Gender and Computer Games, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, Spreadable Media: Creating Meaning and Value in a Networked Culture, and By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism. His most recent books are Participatory Culture: Interviews (based on material originally published on this blog), Popular Culture and the Civic Imagination: Case Studies of Creative Social Change, and Comics and Stuff. He is currently writing a book on changes in children’s culture and media during the post-World War II era. He has written for Technology Review, Computer Games, Salon, and The Huffington Post.

March 11, 2024

OSCAR WATCH 2024 — Video Essay Reflections on Character in ‘Oppenheimer’ (2023)