Henry Jenkins's Blog, page 3

September 8, 2025

EMMYS WATCH 2025 — Television that Changes Us (Part 2): An Interview with Gabe Gonzalez and Sasha Stewart on We Disrupt This Broadcast

In this second part of the “Television that Changes Us” interview about We Disrupt This Broadcast, podcast creatives Sasha Stewart and Gabe González join one of the associate editors of Pop Junctions, Lauren Alexandra Sowa, to discuss how the podcast blends humor, expertise, and cultural critique. They share more about the process, the role of expert voices in deepening conversations, and the impact they hope to spark with listeners.

Lauren: Thank you so much for joining me, Sasha and Gabe. I was wondering if you can tell me a little bit about your role in the podcast—what each of you do, how you work together and collaborate, and how that all comes together.

Gabe: I will kick us off. My name is Gabe Gonzalez. I am the host of the Peabody's podcast, and I also contribute to some of the writing, although Sasha, who is joining us today, is really doing the heavy lifting on that front. Writing and editing is her bag, and I don't think the episodes would be as tight or as beautiful as they are without it. I'm very lucky to work with this team, especially folks like Sasha, because I get to do what I'd be doing anyway—watching television and talking about it. Only now, I don’t kidnap my boyfriend for an hour to talk about what I just watched on Andor (Disney+). I can do it on a podcast with some of my colleagues. It’s nice to be able to redirect that energy elsewhere.

we disrupt this broadcast podcast logo

Sasha: I couldn’t agree more. I’m Sasha Stewart. I am a writer on We Disrupt This Broadcast, and as part of my writing duties, I edit the interviews and transcripts. I love working with our team. We have a small but mighty group. Basically, what we do is come up with: what are these amazing Peabody Award-winning shows that we’re obsessed with? Which ones can we not stop talking about? That helps us pick our themes, and then we eventually write questions around those.

We also always start with an amazing research packet, so we try to create questions our interview subjects have never gotten before, ones others may have overlooked. One of the cool things about our show is that we’re all about: how does this show disrupt cultural narratives? How is this show changing the game and making the world a better place? A lot of cultural shows will stay away from that. But many writers, showrunners, creators, and actors are excited to talk about what drove them to create the show in the first place. We’re a really nice home for folks to talk about what they super care about when it comes to those shows.

Gabe: It’s also a very natural collaboration between the Peabodys and the Center for Media and Social Impact, because both organizations are focused on highlighting and elevating exceptional work. What’s fun about this podcast is we get to dive into what that means. You kind of know it when you see it—it’s like the Supreme Court’s definition of pornography. You know good TV when you see it, but if you’re not in that world, it’s hard to articulate what it is that makes TV exciting, fascinating, thought-provoking, or emotive. Getting to talk to showrunners, experts, actors, and journalists who’ve been covering some of these stories before they’re turned into scripts is such a fascinating process. Sasha and I are both television nerds. We got the writer of an Emmy nominated series with us here today with Sasha. And I am a stand-up comedian who once wrote on a now canceled late-night show, but we both have television experience.

Sasha: We’re both TV writers, end of sentence.

Gabe: That’s true, it’s true. We both love talking about this stuff. Being able to articulate what makes something disruptive is valuable these days—understanding the mechanisms that provoke conversation or thought. PRX (Public Radio Exchange) is the final missing piece of the puzzle, helping us put together such a professional-sounding production. Between all those forces, we’re really proud of the show we get to make and the guests we get to talk to.

Sasha: I think there are a lot of podcasts out there about how a show is made, but we’re the one about why a show is made.

Lauren: That’s excellent, absolutely. When I was listening to the podcast, something I was really impressed with was how seamless the collaboration is. You’re writing questions, Gabe is also a writer, so you’re taking that in, and it all moves together perfectly. I know you both come from politically engaged and media-savvy backgrounds, so do your personal experiences shape the direction of the podcast? Or do things ever surprise you in the moment during interviews—do you change direction after talking to guests?

Gabe: I actually used to work in journalism—that was my day job while I pursued comedy at night. I left journalism for comedy because comedy seemed like a more sustainable industry at the time, during the Facebook/Meta bubble of the 2010s, when everyone in journalism was hiring and then it exploded. I made the shift and doubled down on what I was passionate about.

Lauren: I understand that. Our readers will laugh, but I left acting for academia because it also felt more stable.

Gabe: Haha, right. And now all our creative industries are exploding. I feel like tech is chasing me at every career. It’s the boyfriend that won’t leave me alone, that I should have dumped long ago, but here it is.

Lauren: Well, now with AI, even that’s not stable, so who knows?

Gabe: Exactly. It drives me nuts.

Sasha: And I learned from our Fantasmas (HBO) episode that it’s also private equity and the financialization of culture that’s chasing us everywhere. Just saying, I learn so much from our own podcast.

Gabe: No, for real. We talked to Andrew DeWaard, who wrote a book about how Wall Street devours culture—Derivative Media: How Wall Street Devours Culture—and why it has turned its sights on television and creative fields. That episode really got me fired up, I know it got Sasha fired up, and the whole team fired up. We all come from these industries that merge journalism and the creative, we got experience in both. So, it makes me doubly passionate. I want to get to the why, and I want everybody to be just as mad about it. In some ways, comedy or criticism is an easy way to get folks on board with an idea, rather than yelling at them in an article on the very website that is the problem. Nobody’s looking at articles on Facebook or X anymore.

Lauren: So true. Do you think there’s a balance between humor, critique, and deep analysis? Because as a comedian, and with the podcast not just being heavy—it’s celebratory but also critical—how do you strike that balance for listeners?

Sasha: It’s been a fascinating journey. We all come from comedy backgrounds and are obsessed with comedy. Originally, we had grand plans: we were going to infuse so much humor in the podcast and it’s going to be so funny. We are going to have all these very specific segments. But what we found, and one of the beauties of being in a different medium than we had worked in before, is that you figure out what actually works for the medium. And for podcasts, that hyper-scripted segments are not funny. They just don’t work well. What works better is having a fabulous host and interviewer like Gabe, who brings humor organically. We just trust that it’s going to be funny— we know Gabe is going to bring the humor, he is going to bring the joy, and he is going to connect with the subject in a way that subject isn’t going to suspect, and they are going to bond over something delightful and hilarious. We always end up with these funny moments we put at the end of the episode as our “most disruptive moment.” They’re always unexpected and improvised, which makes them unique. Which, again, we both come from scripted comedy and improv backgrounds, so it makes sense that humor shows up more naturally in conversation. Therefore, when we’re writing questions, we can put on our “nerd hat” and ask the most sincere, intense questions of all time, because we can trust that Gabe will bring the humor and the levity.

Lauren: You have to make them laugh so you can make them cry, right?

Sasha: Absolutely, and we also start interviews with a softer question to warm-up our interview subjects. Not start with “what is this most traumatic experience like?”

julio torres—creator and star, fantasmas (we disrupt this broadcast (season 2)

Gabe: And some folks we are interviewing are already primed to talk about these dark topics in comedic ways, since they are dealing in satire. Fantasmas is a great example—critiquing the isolationism caused by late capitalism through weird vignettes. Severance (Apple TV) was another great example of that, where we got to talk to Ben Stiller, the cast, and production. It’s refreshing to see so many shows embrace satire to critique the world around us. Comedy can be a powerful tool to lay the world bare as it is without being totally depressing, but isn’t afraid to speak the truth, right? That conversational tone is where we can find the happy balance as Sasha had said. As a team, as writers and hosts, we’ve melded together into a Monstro Elisasue voice. I don’t feel like the podcast is just my voice—sometimes he’ll read one of Sasha’s questions and say, “Wow, I was trying to ask that, but it took me three sentences and inarticulate words, and Sasha said it in a sentence and a half. So, love that question!” We mold ourselves to fit each other because we bring different strengths to the table. But the podcast has evolved to meet the moment. We ask: what do our listeners need? What’s the world around us saying? How can we be reflective of that, rather than imposing a rigid structure on our interview series?

Sasha: And the other thing that I think is so great and special about our podcast is that we also give ourselves the opportunity to talk to experts. So, we know that if we want to have a lighter interview with our main subject, we can then pivot into the more hardcore, gritty stuff with our interview guests. In that Fantasmas episode, Gabe and Julio had an amazing conversation that was super funny, very emotional, and in-depth. But then when we talked to Andrew DeWaard, it was like, okay, now let’s get into: what does financialization of culture mean, what are the six aspects of financialization, and what exactly is private equity? And I’m finally going to understand that for the first time in my life.

Gabe: And I will say, just to get brutally honest here for a second, there was a moment during that interview with Andrew DeWaard where he called out the specific CEO of a company as an example of something he’s talking about in his book. In conversations with production, we review notes for everything, and our producer flagged it: is it okay that we say this? I would say that in 8 out of 10 places I’ve worked, whether TV or publications, folks clutch their pearls at a guest calling out a CEO of a powerful company that directly and citing them as the problem and cause of all these symptoms we are outlining. I remember we talked to Jeff about it, and Jeff was like, “Well, that’s the guest’s opinion, so I don’t see why we should censor them.” And that was that.

It feels so liberating to work on a team that isn’t caught up in corporate webs of having to answer to people. It was just like, “hey, we brought on this guest, they’re the best person to talk about this, let’s talk about it honestly.” And if that means pointing a finger to better illustrate their point, then let’s do it. I really appreciate that. It’s less censorship than I’ve faced at major networks that claim to speak truth to power. It’s refreshing, and it feels liberating as a comedian, too, to be able to say, yes, let’s laugh at the guy that canceled the Acme movie that’s coming back anyway because people wanted to see it. I want to do that.

Lauren: That’s awesome to hear that you don’t have to worry about the PR of it all, the studio heads, or the gatekeepers that writers are always trying to get through. You have this space to just be honest and let the guests be honest, and that’s awesome that Jeff was on board with that as well. Do you have any thoughts on how listeners should engage with the podcast beyond just consuming it? Are there other actions or conversations you hope it sparks?

Sasha: What I hope our listeners take away is, first, to think about the culture they consume more critically. To consider what it’s saying, how it makes them think, how it makes them feel. I hope they then talk to their friends and family about it.

We’ve had so many great episodes this year, but I cannot stop talking to my friends about the Fantasmas episode. If I’m that engaged, I’m hopeful our listeners are too. When we talked to Tony Gilroy about Andor Season 2, about fascism and authoritarianism and how leaders are born in crises, I hope listeners took something away about how to act in our current climate. Or in our Bad Sisters (Apple TV) episode, we had an incredible expert talking about divorce, and it made me think about divorce in a way I never had before. I hope listeners, too, thought, “Wow, I’m empowered to see this differently,” or “I never realized I was feeding into cultural bias against divorced women, and the pressure for women to stay in marriages that are bad for them.” So, I hope the podcast is engaging on multiple levels, and that it helps people have difficult, but also fun, conversations with their friends and family.

Gabe: I want to echo something Sasha said earlier about the importance of the experts. One of the greatest takeaways from any episode is their perspectives—their insights into the themes we’re talking about. We had this incredible episodeabout Pachinko (Apple TV). We interviewed the showrunner, but we also spoke with comedian Youngmi Mayer about her Korean heritage and her memoir. I hope people who listen to that episode and watched Pachinko also walk away wanting to read her book or hear her stand-up. She is an incredible comedian. Her themes dovetailed perfectly with the show, offering a modern, irreverent take on a similar story. I like to think we always bring complementary materials or suggested additional reading for people who want to go deeper. If you’re a nerd like us, you can learn more or discover a new historical fact or genre you hadn’t considered before. I hope these experts can expand that universe for you.

Sasha: To that end, we did an episode with Amber Seeley of Out of My Mind, a Disney+ movie about a young woman with cerebral palsy. It’s about accessibility and disability representation, and it’s incredible. The interview was fascinating because she talked about how much better her set was when she made it fully accessible. It wasn’t just for disabled folks on set—it made everyone’s lives better. I hope it sparks people to think, “If I’m an architect, why don’t I design with accessibility in mind? Not just because I have to do it because of ADA, but because it makes everyone’s lives better.” Similarly, our expert in that episode also talked about barriers to accessible and integrated education. It totally blew my mind, and I hope it makes parents listening think differently: is my school accessible? Are my kids getting the education they deserve? Or, if they’re facing those educational barriers, they’ll realize they’re not alone—there are activists everywhere fighting for change.

Lauren: I think one of the things that I love hearing you guys talk about here and on the podcast is this perfect combination of the academic side of things—that a lot of us in media studies are writing about in the journals—and TV creators and writers are creating for television, and you're melding them together, and then bringing it to the public. And the podcast medium allows them to listen to it while they're doing other things; they don’t need to sit and read through the dense research. Yet it can still spark these conversations that we’re all trying to have in different ways. So, I'm so glad that this podcast exists. It’s been fun to listen to!

To wrap up, congratulations again, Sasha, for being a writer on the Emmy nominated Dying for Sex (Hulu). I would love if you could share more of your thoughts on this experience.

dying for sex – Emmy nominee, outstanding limited series nominee

Sasha: Working on Dying for Sex was the career highlight of my life. I had cancer several years ago, I have a number of health issues, and so getting to work on a show that was similar to what we get to talk about on We Disrupt This Broadcast…it was a show that was not afraid to take on these big subjects in a way that is funny, that in our show is very sexy; it was truly the joy of my life.

One of my favorite things that happened with the show, just on a personal level was that I made my therapist cry—because when she watched the series, she said, “I can’t believe how much of our journey that we have been on together that you put on screen.” That’s one of the beautiful things of working on a narrative show: you get to take the difficult, personal experiences and show them authentically through characters who grow and change. And one of the blessings of therapy is you get to grow and change. You get to grow alongside your characters and heal alongside your characters.

An aspect of the show was about how women in particular are often perceived in the healthcare space, are often dismissed in the healthcare space. I think that is something that has happened to me over the course of the last 15 years of my life. It was a huge growth for me being able to express that through a character, and hopefully helps a lot of women who are currently going through the healthcare system advocate for themselves and learn how to talk to their doctors and trust themselves in these really difficult situations. It is really inspiring to me to be able to create characters to model how to do it right. The Sonya character is somebody who I really hope exists a lot more of in the world, because there are so many people who I met in the healthcare system who are trying to make it better—trying to be Sonyas. My oncologist in particular is somebody who was really very wonderful, and a true partner in my experience. So, to show—here's the reality, here’s how it often is—but it doesn't have to be that way. I think that’s one of the beautiful things about narrative TV and trying to disrupt these narratives. You can both authenticate people’s feelings, validate people’s feelings, like, yes, this is the horrible problems we're seeing, and then also model a better future.

Lauren: Incredible. I want to thank you again so much for being here and talking with me today. You both have such insight and wonderful enthusiasm, and I am excited for our readers to engage with your work and the podcast!

BiographiesGabe González is a Puerto Rican comedian, writer and actor living in Brooklyn, NY. He can be seen in Season 4 of The Last OG, the HBO Latino documentary Habla y Vota, and starred in Audible’s The Comedians. His pilot ‘Los Blancos’ was a winner at the Yes And Laughter Lab in 2019 and his satirical sketch “Bootlickers” was an official selection at the LA Comedy Film Festival and Atlanta Comedy Festival in 2022. He’s hosted and produced digital videos for places like MTV, GLAAD and Remezcla, and performed stand-up across the country. His most recent projects include a monthly queer comedy show in NYC called ‘The Lavender Scare’ and working with Imagine Entertainment to pen the short film Alma, available on Amazon.

Sasha Stewart is a Writers Guild Award-nominated TV writer, producer, and creator who creates work that elicits joy, has a positive impact, and gives her an excuse to eat craft services. She most recently staffed on the critically-acclaimed, 9x Emmy-nominated limited-series dramedy Dying for Sex (FX), starring Michelle Williams and Jenny Slate, available to watch now on Hulu (U.S.) and Disney+ (Worldwide). Her TV credits include: Amend: The Fight For America (Netflix), The Fix (Netflix), and The Nightly Show with Larry Wilmore (Comedy Central). She also writes for the Peabody Awards podcast, We Disrupt This Broadcast. Sasha is a winner of the 2024 NRDC Climate Storytelling Fellowship for her and co-creator Casey Rand’s half-hour comedy pilot, Bill on Earth. A PSA starring Jane Fonda she co-wrote aired on CBS Sunday Morning in November 2024. She participated in the 2020 Comedy Think Tank on Paid Family Leave, the 2023 Stand Up For Humans comedy show, and is a winner of the 2020 Yes and… Laughter Lab. She is now part of the Laughter Lab’s Leadership Committee. She contributes to the New Yorker, McSweeney's, and Cosmopolitan. She developed a women’s healthcare docuseries with Samantha Bee and Soledad O’Brien. She’s currently developing an animated half-hour comedy, a lighthearted legal procedural, and has she mentioned you look absolutely radiant today?

Lauren Alexandra Sowa is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Communication at Pepperdine University. She received her Ph.D. from the Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California and has a BFA in Acting from NYU's Tisch School of the Arts. Her research focuses on intersectional feminism and representation within production cultures, television, and popular culture and has been published in The International Journal of Communication and Communication, Culture and Critique. These interests stem from her several-decade career in the entertainment industry as member of SAG/AFTRA and AEA. Lauren is a proud "Disney Adult" and enthusiast of many fandoms. Lauren is also a Pop Junctions associate editor.

EMMYS WATCH 2025 — Television that Changes Us (Part 1): An Interview with the Peabody Award’s Jeffrey Jones on We Disrupt This Broadcast

To kick off our “Emmys Watch” series, Pop Junctions spotlights a podcast that goes deeper into impactful television content. The Peabody Awards continue to champion what they call “stories that matter”—narratives that don’t just entertain, but engage us as citizens. In this interview, Jeffrey Jones, Executive Director of the Peabody Awards and co-creator of the podcast We Disrupt This Broadcast, speaks with one of Pop Junctions’ associate editors, Lauren Alexandra Sowa, about how the podcast extends the Peabody Awards’ mission.

We disrupt this broadcast logo

Lauren: I wanted to start off by saying thank you so much for joining me today and talking about your amazing podcast, We Disrupt This Broadcast. Can you talk a little bit about the genesis of the podcast, what inspired this idea, and how does it complement the mission of the Peabody Awards?

peabody awards logo

Jeffrey: Yeah, so, a couple things. The Peabody Awards are located at the University of Georgia and, as an educational mission, we feel like we have more to do than just hand someone an award, pat them on the back, and say, “good job, put it on your Vita, see you next year.” Which is to say, everything that Peabody recognizes are what we call “stories that matter,” and we really mean that. Not so much “matter” to us as consumers, but “matters” to us as citizens. That mandate of a story that “matters” to us as citizens means that often the stuff we recognize may not be known by many people, including within the industry itself. We do entertainment, news, documentary, public service, children's, and podcasting. So, there's a lot of materials that aren't always well known.

We disrupt this broadcast podcast logo

The second thing about this was this understanding that, since I joined Peabody in 2013, we’ve been living through what scholars call the streaming era. And the streaming era has been massively disruptive to the typical flow of events, and I don't need to articulate all that here. The system was created in a non-advertiser-centric programming flow, and did accentuate prestige programming. But, in that process, a lot of diverse and emerging voices were allowed to create programming: Mo (Netflix), Ramy (Hulu), We Are Lady Parts (Peacock), Pose (FX), Transparent (Amazon Prime), Reservation Dogs (FX), and, I could go on and on, but you get the point—the industry has opened up, allowing more really creative showrunners and storytellers and creatives to tell their stories, which used to be much more marginalized voices.

So, the title is, We Disrupt This Broadcast, and it's so focused on disruption. It's focused on the text and the showrunners—the creatives who are producing these texts that we find disruptive to the industry. The focus is on entertainment television. Almost all have won a Peabody. It is one of the ways in which these kinds of stories are doing something a little different from the broadcast era of television.

Lauren: That's great! It's exciting to hear that you're talking about disruption on the content side of things, because I feel like, as you had mentioned earlier, that a lot of discourse surrounding “television disruption” centers the industrial impact side of things. Many of us are familiar with Amanda Lotz's book, We Now Disrupt This Broadcast, which traces that history. What differentiates your podcast and why I find it a compelling listen is how you're focusing more on what that content is, who the creators are, and what they're bringing to the cultural conversation.

Jeffrey: Exactly. It is disruption and a narrative and cultural flow. Peabody feels very good about the diverse and emerging voices. So, a lot of those people that I named—Mo, Ramy, We Are Lady Parts—there are three shows that have Muslim representation. All were very new showrunners when they won a Peabody Award. The same with Sterlin Harjo and Reservation Dogs. So, those are emerging voices, and they often come out of the gate really strong. They produce Peabody-winning shows, and we want to highlight that.

The podcast is focused on two things: one is an interview with the showrunner and or major talent on the show—traditionally just getting into what they're doing and how and why. The second part of the podcast is strongly emphasized by our producing partners. So, our producing partner is the Center for Media and Social Impact at American University, headed by Caty Borum. In particular, it's an interview with an expert—an academic, a journalist, who can reflect on the kind of cultural, political, and economic dimensions of what makes this show or the showrunner relevant. So, it's grounding the popular, cultural text in the moment of the political, economic, and social context in which it exists.

Lauren: Oftentimes, I feel like we, as academics, try to find this balance between the celebratory part of media and being critical as well. So, would it be fair to say then that in this podcast, you are taking the content that we want to celebrate, and analyzing how it's being critical of culture or critical of these moments?

Jeffrey: Yeah, I think the second expert interview is the moment of more traditional critical analysis. And of course, we don't have a monopoly on that. There's plenty of authors. Though we interview lots of professors, they just aren't often media studies professors. One of the great things is we're often talking to psychologists, to economics professors, to sociologists and others. So, it broadens the conversation. I think the critical component is to reflect on how the text sits within culture, what it illuminates. I do think there's a celebratory part to the podcast. I mean, we're celebrating when we give them a Peabody Award, right? But the critical part of the analysis is that it's really hard to win a Peabody Award. You know, only about 7 to 10 shows win a Peabody in a given year. So, critically, we've cut out a lot that don't belong. And the ones that are there, we are celebrating. And again, I think for the right reasons, because they are doing something in the streaming era that wasn't on television when I was a kid. It didn't exist. Frankly, when you and I were growing up, it wasn't the same kind of text. For the industrial reasons of advertising and the kind of competition, monopoly of the three, four networks, etc.

Lauren: I know that this year, Hacks is an example of a show that has both a Peabody Award and an Emmy nomination, but that kind of crossover doesn’t happen all that often. How do you see the Peabody Awards intersecting with the Emmys? Do you think the Peabody’s can help reach a broader audience? The Emmys often reflect the political canvassing of the Hollywood scene to win. While the Peabody’s seem to focus more on meaningful content without the campaigning. So, in a broader context, what does that say? And how do you think we can bridge the gap between the two to bring that kind of content to a wider audience?

Jeffrey: Yeah, well, I'd start with that, you know, most people don't realize our process. So, Peabody meets 3 times face-to-face. And it is an award that is decided across genres and platforms: television, radio, podcasting, and interactive, which is games and VR, etc. And across genre: entertainment, news, documentary, etc. But in particular, it's decided by a unanimous vote of a board of 18 people. And those 18 people represent lots of different facets. There's critics, which include academics and TV critics, media executives, writers, and showrunners. And I want to compare the face-to-face critical deliberation that we engage in as to who will be a winner is different from a campaign for 26,000 voting members, in which you have no control of what they've watched and what they've not watched. So, they're very different processes. You know, Aziz Ansari was famous for coming to our show and saying, “You know, this is pretty cool. It's like you watch all of our shit, and you just decided it was good, and we didn't have to go to a bunch of weird-ass parties and stuff, you know?”

Lauren: Ha! That’s great!

Jeffrey: So, by being different processes, they are different things. Ours is also not just about the craft: it is, is it a story that matters? So, sometimes the craft can be brilliant, but it may not be a story that matters.

But, back to your question about crossover: yeah, there are popular shows like Hacks (HBO Max), The Last of Us (HBO Max), The Bear (FX), Ted Lasso (Apple TV)—they win Peabody's, they win Emmys. But between the voting process, and really somewhat even the criteria of what we're looking for, that crossover can exist, but may not. And often, it probably doesn't. Peabody will often recognize shows truly on their merits, and not the political forces that shape multi-million-dollar campaigns by the industry players to influence votes.

Lauren: Absolutely. So, now, as someone who has studied and shaped media discourse, what has surprised you most in your conversations about the podcast, or something that was unexpected?

we disrupt this broadcast (season 2, feb 6, 2025) with Bill Lawrence and Brett Goldstein

Jeffrey: Not really. It's just a privilege to be able to talk to showrunners about their craft. It's a privilege to look for themes. I mean, I think we probably interview a little differently than journalists, probably because we're academics. We want to dig into the text a bit more than a traditional media trade publication, journalist interview. So, I think about my interview with Bill Lawrence and Brett Goldstein about Shrinking (Apple TV) and Ted Lasso (Apple TV). You know, I'm a man of a certain age, and so is Bill, and I literally said it in that way, and he laughed, said, yes, we are. And we got to talk about toxic masculinity and therapy, and then with Shrinking, about forgiveness, and the textual themes that are percolating across both of those shows. So, in that regard, I feel not so much surprised as by what a privilege it is to hold that conversation.

Lauren: You had a successful two seasons of the podcast. Are there plans for season three as well? What do you see as the future for We Disrupt this Broadcast?

Jeffrey: There are indeed. We will launch Season 3 either later this year or early 2026. We're very happy. I should give a shout out to our producing partner, PRX (Public Radio Exchange), which produces a lot of quality podcasts. They reached out to us to produce this show, and we couldn't be happier. They're quality folks, and I'm very happy to still support public radio even through the PRX avenue.

Lauren: Well, I think that our audience, or our readers, would definitely enjoy listening to this podcast. I just started, too, and I think it's excellent. Gabe Gonzalez does a wonderful job with his interviews. One of the things that strikes me is that it is academic, but it is incredibly entertaining and very human. I think that's one of the best parts about listening to it, and I think that's what makes it engaging for people who study this and people who don't. I think it's accessible to everyone.

Jeffrey: One of the things that's great about our podcast, I think, and I'm a huge Gabe Gonzalez fan, is that he's a comedian, and extremely smart, and extremely talented.

Lauren: Agreed! Thank you again so much. Is there anything else you want to share or add that I didn't ask about that you would want everyone to know?

Jeffrey: That's a great one, always a great question. One of the things is that Peabody is a very respected award. It's existed for 85 years, it predates the Emmys, because we were recognizing radio broadcasting first. And there's still so much integrity to the award and love for the award in the industry. But the Peabody's, because of its position a little outside the industry, and at a university, there's a little bit of a moral imperative, if you will. It's not just the base to win a Peabody on popularity, but this is the way storytelling does something for us as citizens. So, I think one of the things that's great about the podcast is it's leaning into that. It's not just celebrating entertainment. It's trying to talk about the ways that popular culture and entertainment can deeply shape who we are and want to be as a people, as empathetic citizens in the world. And that's, of course, what Henry Jenkins' whole career has been built on, and why Henry identifies with Peabody and contributed to it for 6 years.

It's that kind of imperative, I think, that we believe, like Henry does, that entertainment can be a positive force, especially in an era when so much news media is seen as rejectable.

As a rejectable truth, as something that you’re buying a brand that's no different than the politics that you adhere to. But when you're telling stories that are deeply empathetic about people and the world that aren't like you, maybe there's an avenue for people to watch it as entertainment and see a part of the world, or even a part of themselves that they weren't in touch with, and that they'll give more credence to, and more love for, and more empathy for. And that's what popular entertainment can do. And to me, that's what the Peabody Awards lean into when we do entertainment programming, but it's especially what this podcast does.

Lauren: That's beautifully stated. I was going to say, that's why art and pop culture (it's all the same thing, right?) makes us human and, like you said, tells the stories about who we are as a people. It's why most of us study this, and why we dedicate our lives to it, right?

Jeffrey: Sure, absolutely, for sure. For sure.

Lauren: That's great. Well, thank you again so much, Jeff. I really appreciate it. This was a really fun, very informative conversation.

Biographies

Jeffrey P. Jones is the Executive Director of the George Foster Peabody Awards at the University of Georgia and Lambdin Kay Chair for the Peabodys in the Department of Entertainment & Media Studies. Jones became only the fifth director of the Peabody Awards in 2013. He holds a Ph.D. in Radio-TV-Film from The University of Texas at Austin. In conjunction with the Center for Media & Social Impact at American University and produced by PRX, Peabody launched a podcast in 2023—WE DISRUPT THIS BROADCAST—celebrating entertainment winners through the lens of cultural and industrial disruption in the streaming era. Professor Jones is the author and editor of six books, including Entertaining Politics: Satiric Television and Civic Engagement, Satire TV: Politics and Comedy in the Post-Network Era, and The Essential HBO Reader. His research and teaching focuses on popular politics, or the ways in which politics are engaged through popular culture.

Lauren Alexandra Sowa is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Communication at Pepperdine University. She received her Ph.D. from the Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California and has a BFA in Acting from NYU's Tisch School of the Arts. Her research focuses on intersectional feminism and representation within production cultures, television, and popular culture and has been published in The International Journal of Communication and Communication, Culture and Critique. These interests stem from her several-decade career in the entertainment industry as member of SAG/AFTRA and AEA. Lauren is a proud "Disney Adult" and enthusiast of many fandoms. Lauren is also a Pop Junctions associate editor.

July 4, 2025

Frames of Fandom: An Interview on Fandom as Audience (Part Three)

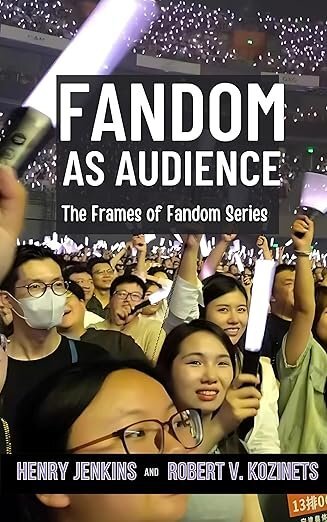

Henry Jenkins and Robert Kozinets recently released the second book in their Frames of Fandom book series, Fandom as Audience. The ambitious project will release 14 books on various aspects of fandom over the next few years. A key goal of the project is to explore the different ways that different disciplines, especially cultural studies and consumer culture research, have examined fandom as well as the ways fandom studies intersects with a broad range of intellectual debates, from those surrounding the place of religion in contemporary culture or the nature of affect to those surrounding subcultures or the public sphere.

Pop Junctions asked two leading fandom scholars, Paul Booth and Rukmini Pande, editors of the Fandom Primer series at Bloomsbury, to frame some questions for Jenkins and Kozinets.

SEE PART ONE SEE PART TWO BUY FRAMES OF FANDOM

books 1 and 2 in the frames of fandom series

Through both books the examples of fandom used are a mix of primarily North American fan cultures along with mentions of non-Anglophone ones, such as k-pop. While this mix certainly accomplishes the goal of showing the diversity of fandom spaces/objects/practices, how does the series also accommodate adequate consideration of the differences between them and the role of conflict in contemporary fandom communities? (Specifically, Book 2's overview of kinds of fans and their relationship to both each other and media texts/industries mentions the idea of fandom being where fans of marginalized identities can “appropriate” texts and refashion them to their own ends. There is also a side-bar that discusses the different ideas of appropriation and their complications, which is well taken. How does this discussion of audiences and their motivations interface with work on fandom spaces that has highlighted the roles racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism, etc continue to play in fandom communities and their reworkings of media texts?)

Henry: These are questions we’ve struggled with as we have been writing these books. The past decade has seen thorough and evolving critiques of fandom studies on the basis of race in particular, and we want to do the best we can to acknowledge those critiques and factor them into our considerations. We do so with an awareness that there is going to be a tension between the importance of representing a broad range of perspectives on these topics and also recognizing that as two white Anglo-American authors, this is not necessarily “our story to tell.”

All I can say is that we are trying to find our balance within this shifting terrain, and one way we do so is by highlighting the work of fandom scholars of color across all of these volumes and representing these debates through the insights they provide us. Fandom as Audience includes discussions of racebending Harry Potter, for example, that include the interpretive and expressive work of Black fans doing fan art and fan fiction to illustrate Stuart Hall’s notion of negotiated readings. Our book on Fandom as Subcultureforegrounds the example of a Black Disney bounder, considers the case of hijab cosplay, discusses the ways Black fans work around their marginalization in the mass media texts that inspire much of cosplay practice, and much more. Fandom as a Public situates the recent discussions about “toxic fandom” or racism in fandom in the larger context of Nancy Frazier’s critique of Habermas’s claims about the “equal access to all” offered by the public sphere that emerge from his idealized understanding of the early modern European coffee houses. We show that contradictions about inclusion and exclusion surround the notion of the public from the start, and that we should not be shocked, though it is critical to understand, that fandom often falls short of its utopian ideals about creating a safe space for all who share passion for the same object.

One of the challenges, then, with trying to represent the broadest range of different perspectives and experiences through the books is that we can only represent the work that is already out there, and thus we are doomed to reproduce some of the blind spots in the existing literature. Our hope is that in mapping the field, we make the strengths and limitations of this work visible to emerging scholars, so they can focus their energies in ways that allow them to make original contributions.

Something similar can be said about the shift of fandom studies to encompass diversity on a transnational or transcultural, if not yet global, scale. My own current interests include supporting and amplifying work on fandoms in East Asia, particularly China. I have started a research network that is bringing together a mix of researchers based in the United States, China, Korea, Japan, and beyond to do collaborative and comparative work together. This research group has two special issues of journals under development, one for the International Journal of Cultural Studies, and one for the Shanghai-based journal Emerging Media.We include such perspectives in every book in the series, but we also focus on it more explicitly in the Fandom as a Force of Globalization and Fan Locations books.

There and elsewhere, we pay attention to the tensions between pop cosmopolitanism/transcultural fandom (forms that connect across national borders) and fan nationalism (conflicts that seek to align fandom to national interests and to police borders between cultures). This is one of the key conflicts within fandom today, and to understand it, we may need to try to keep multiple and seemingly contradictory insights in mind at the same time. We signal the potential mobilization of fandom and fan-like structures by global strongmen in Defining Fandom, and we explore other forms of “toxic” or conflictual forms of fandom throughout all of the books. Our forthcoming book on Fandom as Public discusses some of the research on QAnon that has emerged within fandom studies, but we also look at ASMR fandom as a space where a more healing or therapeutic function emerged during the pandemic lockdown. We talk about the ways that the Chinese state encourages an entanglement between fandom and the national interests that restricts what can be said but also requires the performance of nationalism. But we also discuss how the free speech and participatory ethos of the Archive of Our Own struggles to deal with the structural and systemic racism that make it a sometimes uncomfortable space for fans of color.

We certainly have our own biases as researchers and mine includes a framing of the opportunities for cultural and political participation that fandom affords that is more optimistic than that of scholars drawn from critical theory and political economy. We also want to provide an overview of the field as a whole and that includes citing critiques of fandom and fandom studies.

I appreciate your acknowledgement of the ways we discuss appropriation. From the start, fandom studies has centered on the ways diverse audiences appropriate and rework resources from mass culture as the basis of participatory culture. This has included the ways that groups marginalized in the source text speak back to media producers and re-story the media. Yet, we also have to acknowledge that there are ongoing critiques of cultural appropriation which have rendered that term problematic. How do we reconcile the two? Writers like Mikhal Bakhtin tell us that all cultural expression involves appropriation – the language we use does not come pristine from a dictionary but from other people’s mouths. Rather than a simple dismissal of appropriation, which would be inconsistent with other aspects of the field, we should ask harder questions and offer more nuanced accounts of the ethics of appropriation. When is it appropriate to appropriate?

I am not sure we have the answers to this question yet and perhaps not even the best framework for asking it, but at least we are acknowledging the problem here and considering some ways people are trying to address it. In Defining Fandom, there is a similar section where we consider the metaphor of consumer tribes and tribalism as it has been developed in consumer culture research and critique it from perspectives drawn from indigenous studies.

Henry Jenkins is the Provost Professor of Communication, Journalism, Cinematic Arts and Education at the University of Southern California. He arrived at USC in Fall 2009 after spending more than a decade as the Director of the MIT Comparative Media Studies Program and the Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities. He is the author and/or editor of twenty books on various aspects of media and popular culture, including Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture, Hop on Pop: The Politics and Pleasures of Popular Culture, From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: Gender and Computer Games, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, Spreadable Media: Creating Meaning and Value in a Networked Culture, and By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism. His most recent books are Participatory Culture: Interviews (based on material originally published on this blog), Popular Culture and the Civic Imagination: Case Studies of Creative Social Change, and Comics and Stuff. He is currently writing a book on changes in children’s culture and media during the post-World War II era. He has written for Technology Review, Computer Games, Salon, and The Huffington Post.

Robert V. Kozinets is a multiple award-winning educator and internationally recognized expert in methodologies, social media, marketing, and fandom studies. In 1995, he introduced the world to netnography. He has taught at prestigious institutions including Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Business and the Schulich School of Business in Toronto, Canada. In 2024, he was made a Fellow of the Association for Consumer Research and also awarded Mid-Sweden’s educator award, worth 75,000 SEK. An Associate Editor for top academic journals like the Journal of Marketing and the Journal of Interactive Marketing, he has also written, edited, and co-authored 8 books and over 150 pieces of published research, some of it in poetic, photographic, musical, and videographic forms. Many notable brands, including Heinz, Ford, TD Bank, Sony, Vitamin Water, and L’Oréal, have hired his firm, Netnografica, for research and consultation services He holds the Jayne and Hans Hufschmid Chair of Strategic Public Relations and Business Communication at University of Southern California’s Annenberg School, a position that is shared with the USC Marshall School of Business.

July 2, 2025

Frames of Fandom: An interview on Fandom as Audience (Part Two)

BOOK 2: FANDOM AS AUDIENCE

Henry Jenkins and Robert Kozinets recently released the second book in their Frames of Fandom book series, Fandom as Audience. The ambitious project will release 14 books on various aspects of fandom over the next few years. A key goal of the project is to explore the different ways that different disciplines, especially cultural studies and consumer culture research, have examined fandom as well as the ways fandom studies intersects with a broad range of intellectual debates, from those surrounding the place of religion in contemporary culture or the nature of affect to those surrounding subcultures or the public sphere.

BUY FRAMES OF FANDOMPop Junctions asked two leading fandom scholars, Paul Booth and Rukmini Pande, editors of the Fandom Primer series at Bloomsbury, to frame some questions for Jenkins and Kozinets.

SEE PART ONE

what is a ‘fan’?

I'm curious about the conceptualization of what a “fan” is. Does that definition change between books?

Rob: We took special care to define what we mean by “fan,” “fanship,” and “fandom” early in the series, and we did this not because we thought the terms were unfamiliar, but because we found that they were being used inconsistently, even by experts. Sometimes “fandom” referred to an individual’s enthusiasm, for instance, but at other times it described a collective entity. We needed to have that conceptual clarity to move forward with the other work we wanted to do in the series. So, although the definition does not change from book to book, it does develop, and we add nuance to its various elements. We build on them, return to the definition, even challenge it from different angles—but, fortunately, the foundation holds.

Our distinction is rather simple, yet essential. Fanship is a personal, passionate relationship between an individual and a fan object. It’s an orientation, an emotional and cognitive investment in a piece of culture: a team, a singer, a show, a brand, a game. Fandom, by contrast, is what happens when that fanship becomes social. When fans affiliate with others, when they participate in shared rituals, critique, creativity, or community, they enter into fandom. Fandom is thus always a collective formation of some kind. It includes norms, histories, values, and practices that are produced, shared, and sometimes contested by its members.

We think this distinction is powerful because it travels. It works across domains—music, sports, fashion, theme parks, politics, celebrity, brands. It respects solitary fans who have never set foot in a forum or a fan con, while also giving us language to talk about the intense collective energies that swirl around franchises like BTS, Formula One, Taylor Swift, and the UFC. It helps us map different kinds of involvement without being forced into ranking them. It also allows us to develop and accommodate the many digital advances that have altered the terrain, trajectory, and capacities of fans and fandoms, most notably those involving social media.

We also emphasize that fandom is not a static identity. It moves, changing through our lives and across our different activities. Fans shift in and out of fandoms over time. Their levels of involvement change. Our framework accommodates that fluidity, offering something more than a typology, and less than a rigid model. It’s a way to think about how people organize meaning through the passionate cultural engagements they form both alone and together.

So no, the definition doesn’t change. But it does get tested, elaborated, and put to work. That was the point. We didn’t want to assume we already knew what fandom was. We wanted to build a foundation strong enough to support fifteen books and flexible enough to grow with them.

Henry: Each frame allows us to see things we would not see otherwise. Star Trek surfaces in almost all of the books because it was the starting point for both of us and because it has been so foundational for both media fandom and fandom studies. Other fandoms, such as those around Disney, Marvel, Star Wars, K-pop and Harry Potter, appear often across the books. Each time they surface, though, we add some new depth as we look at them from another vantage point. We may discuss how Black fans of Harry Potter explore the possibilities of a mixed-race Hermoine in Fandom as Audience and fan responses to J. K. Rowlings’ transphobic comments in Fandom as Activism. Other examples are more local – we consider how Netflix has built Wednesday to address multiple audiences in Fandom as Audience or how a public sphere about gender and sexuality issues surfaces around the comic books Sex Criminal and Bitch Planet in Fandom as Public or how Good Omens inspired an online exploration of spirituality issues in Fandom as Devotion.

In terms of the purpose of these books, at one point you mention that you hope the series will help practitioners – marketers, brand managers – to interact with fan communities on the principle of “do no harm.” How does this work within contemporary fandom spaces which are increasingly polarized and where “harm” can be conceptualized very differently by different fan groups? Is there a consideration of ethical issues facing fandom researchers and practitioners? Is there a space for discussion of toxicity in fandom?

Henry: We do not have a separate book on fan ethics – perhaps we should. But I’d like to think that ethical issues – for researchers, for practitioners, and for fans – surface across every book in the series. The goal of creating a conversation between fandom studies and consumer culture research is not to teach industry how to better “exploit” fans but to help them to understand the richness and complexity of fandom as a site of cultural experience within the context of a consumer economy. To serve those ends, we often include passages that show points of friction between fans and industry – for example, book 2 includes a discussion of the concept of fans as surplus audiences, how Alfred Martin has taken up the concept of “surplus Blackness” as a means of critiquing the racial assumptions guiding contemporary franchises, and the ways that “queer baiting” has been critiqued within fandom studies. In Fandom as Co-Creation, we dig deep into the literature on fan labor and explain why many existing industry practices that claim to “honor” fans actually exploit them. We link this work to the debates around the Paramount guidelines on Star Trek fan cinema and a larger consideration of intellectual property law, transformative works, and fair use.

We definitely will be taking up sites of conflict between different groups of fans, including reactionary backlash by white male fans against women and fans of color, and we definitely deal with the growing literature on so-called “toxic” fan cultures, especially in Fandom as Public. I am sure we will face criticism on the balance of different perspectives here. Even with the large canvas this book series provides us, we will not be able to discuss everyone and everything, and our own blindness and privilege will be on display. But in creating this framework, we will create something that other scholars can push against and call attention to what is still missing in a field of research that for too long was shaped by presumptions of whiteness and Anglo-Americanness.

Rob: Yes, “do no harm” is a principle we offer to practitioners, but we don’t mean it naively. We’re fully aware that harm, like toxicity, is a contested category. What one fan sees as righteous defense of their values, another sees as overreaction or harassment. What a marginalized fan calls a reasonable and direct critique, a showrunner might experience as outlandish abuse. And from the point of view of an authoritarian government, even playful remix culture or satire can read as dangerous thought crime. So when we talk about harm in fandom spaces, we’re talking about something that always has to be contextualized socially, culturally, and politically.

Fandom gives people a channel for strong feelings. Love, anger, grief, obsession, loyalty, and betrayal: fan communities are pulsing with these emotions. In an age when formal institutions often fail to reflect people’s values or listen to their concerns, fandom has become one of the few arenas where people feel like they can speak together about and maybe even back to power, or act to reshape culture in their own image or into forms that suit them better. That’s why governments monitor fan spaces. That’s why platforms struggle to manage fan conflicts. That’s why brands court fans and fear them at the same time.

We’re not trying to sanitize that energy, though. We respect it, and we are doing our utmost to try to understand it. Across the series, we return to the idea that fandom is a passionate form of cultural participation, not a passive state of appreciation. It’s not neat, and it’s not always polite. Sometimes it’s defiant. Sometimes it’s funny. Sometimes it’s cruel. But it is always meaningful to those within it. And when that passion becomes collective—when it organizes, critiques, remixes, or revolts—it forces industry and institutions to listen. That’s not toxicity. That’s power and culture being built and rebuilt.

Of course, there are behaviors that cross lines. There are moments when fandom mirrors or reproduces structural harms—racism, misogyny, queerphobia, nationalism. We don’t make excuses for those things, of course, but we also don’t believe you can understand or engage with fandom by labeling entire communities as “toxic” from the outside. Those elements, like racism and misogyny, are not particular to fandoms or fans–they are all around us, and some fans express them, as one would expect. There is a bigger picture, however, in the study of how norms are negotiated within fan cultures, how boundaries are drawn, how accountability functions—or fails to. Those are interesting and important discussions to have, beyond simply labeling this or that phenomenon or behavior as “toxic” or “inclusive.” We think this sort of intellectual elaboration happens alongside viewing fandoms not only as expressive publics, but as moral economies, with their own forms of justice, solidarity, and exclusion.

Ethics, in that sense, is not a separate topic in the series. It runs through every volume, because we are always asking what these relationships—between fans and brands, fans and each other, fans and society—require and demand. We don’t claim to have the final word. But we hope the series opens space for that ongoing conversation and models the kind of respect and critical generosity that we believe fandom itself, at its best, embodies.

More to come in Part Three.

Henry Jenkins is the Provost Professor of Communication, Journalism, Cinematic Arts and Education at the University of Southern California. He arrived at USC in Fall 2009 after spending more than a decade as the Director of the MIT Comparative Media Studies Program and the Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities. He is the author and/or editor of twenty books on various aspects of media and popular culture, including Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture, Hop on Pop: The Politics and Pleasures of Popular Culture, From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: Gender and Computer Games, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, Spreadable Media: Creating Meaning and Value in a Networked Culture, and By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism. His most recent books are Participatory Culture: Interviews (based on material originally published on this blog), Popular Culture and the Civic Imagination: Case Studies of Creative Social Change, and Comics and Stuff. He is currently writing a book on changes in children’s culture and media during the post-World War II era. He has written for Technology Review, Computer Games, Salon, and The Huffington Post.

Robert V. Kozinets is a multiple award-winning educator and internationally recognized expert in methodologies, social media, marketing, and fandom studies. In 1995, he introduced the world to netnography. He has taught at prestigious institutions including Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Business and the Schulich School of Business in Toronto, Canada. In 2024, he was made a Fellow of the Association for Consumer Research and also awarded Mid-Sweden’s educator award, worth 75,000 SEK. An Associate Editor for top academic journals like the Journal of Marketing and the Journal of Interactive Marketing, he has also written, edited, and co-authored 8 books and over 150 pieces of published research, some of it in poetic, photographic, musical, and videographic forms. Many notable brands, including Heinz, Ford, TD Bank, Sony, Vitamin Water, and L’Oréal, have hired his firm, Netnografica, for research and consultation services He holds the Jayne and Hans Hufschmid Chair of Strategic Public Relations and Business Communication at University of Southern California’s Annenberg School, a position that is shared with the USC Marshall School of Business.

June 30, 2025

Frames of Fandom: An Interview on Fandom as Audience (Part One)

Henry Jenkins and Robert Kozinets recently released the second book in their Frames of Fandom book series, Fandom as Audience. The ambitious project will release 14 books on various aspects of fandom over the next few years. A key goal of the project is to explore the different ways that different disciplines, especially cultural studies and consumer culture research, have examined fandom as well as the ways fandom studies intersects with a broad range of intellectual debates, from those surrounding the place of religion in contemporary culture or the nature of affect to those surrounding subcultures or the public sphere.

BUY FRAMES OF FANDOMPop Junctions asked two leading fandom scholars, Paul Booth and Rukmini Pande, editors of the Fandom Primer series at Bloomsbury, to frame some questions for Jenkins and Kozinets.

henry jenkins and a furry fan

The books (esp. book 1) straddle autobiography and autoethnography. In your minds, is there a separation between the two (and does there need to be?) and how does your own personal background affect the books?

Henry: It would be hard to exclude the autoethnographic/autobiographical voice from a book on the field of fandom studies. As we discuss in Fandom as Subculture (not yet published), the aca-fan stance has been a founding and defining trait of fandom studies. We pay tribute there to the work of Angela McRobbie, whose influence I have come to see as absolutely foundational to my own work in Textual Poachers. In her “Settling Accounts” essay, she calls out the male researchers at Birmingham who were writing about various British subcultures without acknowledging their own involvement with them. She advocated a feminist standpoint epistemology as the intellectually honest way to approach such terrain. I would say the passages in the books where we write about our experiences as fans are a fulfillment of those principles.

I have often been reluctant to go full autoethnography in the past when writing about, say, female fan fiction writers in Textual Poachers, for fear that as a male scholar I would be taking up too much space or redirecting attention away from the feminist/feminine project of fan fiction. But, here, I can tap my own participation in, say, the monster culture of the 1960s as we examine the ways it deployed a range of domestic technologies and practices – from monster models to my mother’s eyeshadow, which I appropriated for monster make-up, to a super-8 camera or a Disney record of haunted house sounds or the photocopier from my dad’s company – to encourage and enable new forms of participatory culture.

Our use of the first-person is also a challenge to the anonymous voice with which most textbooks are written and the reason why such “nonhuman” prose becomes deadly to read. We often use first person to call attention to the forms of association between people that shape our scholarship, seeing scholarship as emerging through conversations, debates, and even confrontations between human beings. This is something I never got from a textbook: understanding here who our mentors were, who our students were, who our collaborators are, to help readers grasp the collaborative nature of scholarship. We don’t like the mind/body split implied when we focus exclusively on ideas without acknowledging the people behind them.

Rob: There is a distinction between autobiography and autoethnography, and it’s a meaningful one, although perhaps it is not always a hard and fast boundary. We certainly do straddle it in Defining Fandom and across the series, and we do that very intentionally. Autobiography, traditionally, is about self-expression and narrative coherence, where the telling of a life, or a slice of it, foregrounds the personal and the idiosyncratic because it is interesting and entertaining in itself. Autoethnography, on the other hand, takes that personal slice and uses it for a purpose–it refracts it through conceptual lenses and asks, “What does this story help us understand about culture, media, society, technology or something else? What frameworks does it offer to us, which does it challenge, which does it expand upon?”

Our series, and especially the first book, mobilizes autobiography in the service of autoethnography. So we are not just telling stories about our youthful engagements with Batman, Gilligan’s Island, or Pogo comics because we think they might be charming tales or nostalgic trips down memory lane (which, sometimes, they might be). We're using them to get at some of the finer conceptual points of fandom, to calibrate, through the lens of our own experiences, its meaning across personal, cultural, commercial, sacred, and other territories.

This requires a kind of careful attunement. We are aware that who we are—our backgrounds, identities, affiliations, fascinations, values, emotional repertoires, and much more—shapes how we understand fandom, and even what aspects of fandom we consider meaningful. But rather than bracketing that influence, we try to make it central. Positionality in qualitative research doesn’t eliminate subjectivity (that is inevitable in all research) but it does seek to make it visible so that we can make it count in our interpretations. It acknowledges that who we are shapes what we see, how we interpret, what we choose to write down and leave out. Like I tell my students when I teach qualitative research methods, positionality isn’t a bug: it’s a feature of cultural inquiry. By placing our subjectivities in full view, we treat them not as something which distorts or “biases” our perspectives but as instruments that can be adjusted for, cross-checked, and interpreted in light of their specific strengths and limitations–something we are doing constantly behind the scenes as we write this book series and try to adjust for our mutual blind spots.

That said, although we have some key similarities, we don't speak from a single unified voice. Instead, we use our two voices to emphasize the divergences between us—our different relationships to religion, for example, or to particular genres (like sports, videogames, and music), or even to what counts as “serious” academic work. These differences aren’t obstacles to understanding; they actually are our understanding. We are modeling through our voices and their perspectives what it looks like to build theory in dialogue, across perspectives, with attention to friction and resonance.

That’s also why our approach embraces a diversity of fan practices, motivations, and intensities, just as we show our own attachments as uneven, sometimes ambivalent, and always transforming. The personal becomes meaningful when it is not only deeply felt but also when it is analytically situated as a formation we can use to ask better questions about how people form attachments, how meaning circulates, and how cultural structures shape affective life.

In this way, the autobiographical and the autoethnographic come together for us as complementary modalities. One provides raw material we enjoy writing and feel passionate about, while the other encourages us to be judicious and consider its processing into a more conceptual form of understanding. One brings the reader closeness and the specificity of particular examples; the other offers some degree of distance and a space for abstract reflection and considerations. Our books use both, not to collapse the personal into the scholarly, but mainly to explore how one can clarify and deepen the other.

Can you discuss what impact you want the books to have? Why these topics for the fifteen books – how did you come up with those, why not others? They are semi-academic, semi-personal; they are short, but still longer than (say) the Fandom Primer series; they are built around the two of you, but tell stories of fandom across a spectrum of ideas. How should readers “place” the books in their categorization of books about fandom?

Rob: The impact we hope for is both intellectual and practical. We want these books to help reframe how fandom is understood and approached across multiple fields. That means deepening the conversations already happening in cultural and fan studies while also extending them into marketing, consumer research, and communication studies. We want the work we’ve each done separately to meet here, in dialogue. Not fused into some hybrid middle but sharpened through contrast and coordination. These books aim to do that work out in public, so to speak.

The initial goal was modest. We needed a textbook for our Fan(dom) Relations course at Annenberg. But very quickly, the project expanded. It became an intellectual voyage, one that it seems we could only take together. The idea of “frames” gave the whole notion structure as well as depth. Each book would examine a different paradigm for understanding fandom: Fandom as Audience. Fandom as Subculture. Fandom as Activism. The frames overlap, they build on one another, and sometimes they even conflict with one another. That’s okay; we actually wanted that level of complexity and depth. This wasn’t a master theory of fandom we were putting together. It was always meant to be a way for us to think about and across fandom’s many multiplicities.

Fandom today is multifarious—it is strong, great, and numerous. We think that, for better and worse, has moved from the margins to the center of culture, economics, identity, and politics. We wanted to write books that reflected that shift. These books had to find a balance between being focused, teachable, grounded in prior thinking, up-to-date, future forward, and conceptually rich. The books are short but not light. They are accessible but not simplistic. And yes, they’re personal. We appear in them because we believe that theory is better when it’s situated, when it has a voice, a history, and a perspective.

The fifteen topics we chose reflect a kind of mapping exercise. They trace out the dominant ways scholars and practitioners have tried to understand fandom. Some frames, like Fandom as Participatory Culture or Fandom as Co-Creation, reflect well-established paradigms. Others, like Fandom as Desire, Fandom as Devotion, Fandom as Technoculture, or Fandom Relations, push into less charted territory that we think is important or will be. But every book tries to say something new. We are trying to use these books to develop a novel perspective, not just report on or overview existing ones.

We’re aware that this series doesn’t fit easily into existing categories. It’s not quite academic publishing, but it’s also not a fan primer or how-to. These are conceptual books written by researchers, who are also fans, and by fans, who are also researchers. We’re building on decades of work that has argued—we think correctly—that fandom is not a deviation from everyday life, but a powerful and productive mode of engaging with culture. That argument has been made and what we do here is trace in a variety of new ways its implications for scholars, students, managers, and certainly for fans themselves.

Where should these books be placed? Maybe in the space that doesn’t yet exist: a shelf for works that take fandom seriously as a global social form. That speak across disciplines. That engage theory without detaching from lived experience. That are willing to argue, to speculate, to build, and to risk being wrong. This, as I see it, is the Frames of Fandom series.

Henry: Our initial discussions on the project centered on the high costs of textbooks and especially student frustration when only small portions of books are used. Most students have not yet learned to think of books as long-term investments not restricted to the benefits to be gained within the context of a particular class. But what if we could deconstruct the textbook, allowing people to, in effect, buy chapters a la carte, paying for only the portions they need? This question is what started us down the path towards self-publishing.

As we got into it, our idea of selling a book chapter by chapter evolved into the concept of short-ish books focused around a single frame but looking at that frame from a number of different angles, thus incorporating a broad array of different literatures.

Revision of Hall’s ENCODING/DECODING MODEL

So, the book on fandom as an audience largely foregrounds how the approach grew out of Stuart Hall’s encoding/decoding model, but it also considers some other parallel developments from consumer culture research, reader-response theory, or formalist film theory, each of which taught us things we needed to know to understand fandom. We hit the big names, but we also are reintroducing writers who have often dropped out of the conversation about fandom within fandom studies, considering for example Dorothy Hobson’s advocacy on behalf of the audiences for soaps or Martin Barker’s potential contributions as a critic of fandom studies methodology.

When John Fiske asked me to write a book about fans in the early 1990s, he wanted a grand theory of fandom, which was not something I could write given the state of research on fans then. Textual Poachers became a study of a relatively discrete set of fans – the women who wrote and read fan fiction – though there are mixed signals throughout as it tends to universalize these fans or incorporate material from research on other kinds of media audiences. Many of the criticisms writers like Matt Hills directed against the book locate contradictions, uncertainties, inconsistencies, and hesitations that emerged from those competing ideas about the book’s project.

Now, we are at a place where there is a massive body of scholarship on fans, and so we can begin to map this as a field while, at the same time, constantly pushing for a more inclusive understanding of what fandom studies might learn from other adjacent bodies of literature. Simply bringing consumer culture research and fandom studies together, which is at the heart of our initial vision, is a large contribution. Trying to keep up with the writings about fandom beyond the Anglo-American world, say, requires active searching and careful contextualization of the similarities and differences that emerge. Debates within fandom require us to go back to intellectual roots, to consider roads not taken, works not read or discussed, that might allow us to expand our research in productive new directions.

Often as we are writing these books, we have in mind a reader being introduced to the field for the first time, someone in graduate school who is searching for where they might make their ‘original contribution.’ We are leaving many, many breadcrumbs here. But also, as a scholar in my, erm, late 60s, I am trying to trace my own journey through this space, consolidate ideas developed in scattered publications, weigh ideas to see how I might modify them if I were writing these works today, acknowledge old debates and heal old wounds. I have made many different contributions to fandom studies at different phases of my career, as has Robert, and these books function as introductions to our body of scholarship as well as maps of the field more broadly.

One challenge, though, is that these books are coming out on a rolling basis. The core of each book is drafted, so we can point to what topics will surface in what book, but we are also adding and reflecting as we prepare them for publication. About a third of the content or more comes at that stage. We are writing as if the whole project had been completed, including pointers to what’s in the books not yet published. We hope people will be patient since all of this apparatus will be helpful once the project is completed. I also worry that people will get upset because we did not include a person or topic in book 2 that was always planned to be discussed in book 10. So, bear with us…

More to come in Part Two.

BiographiesHenry Jenkins is the Provost Professor of Communication, Journalism, Cinematic Arts and Education at the University of Southern California. He arrived at USC in Fall 2009 after spending more than a decade as the Director of the MIT Comparative Media Studies Program and the Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities. He is the author and/or editor of twenty books on various aspects of media and popular culture, including Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture, Hop on Pop: The Politics and Pleasures of Popular Culture, From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: Gender and Computer Games, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, Spreadable Media: Creating Meaning and Value in a Networked Culture, and By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism. His most recent books are Participatory Culture: Interviews (based on material originally published on this blog), Popular Culture and the Civic Imagination: Case Studies of Creative Social Change, and Comics and Stuff. He is currently writing a book on changes in children’s culture and media during the post-World War II era. He has written for Technology Review, Computer Games, Salon, and The Huffington Post.