Kelsey Timmerman's Blog, page 6

January 9, 2019

Is awareness a burden or the key to happiness?

“Don’t F@ck with chocolate. I don’t want to know.”

That was a friend’s reaction when I told him I was researching the book that would become WHERE AM I EATING?, a book in which I traveled around the world to meet farmers who produce chocolate, bananas, coffee, lobster, and apple juice.

The cocoa farmers I met in West Africa lived in poverty. A worker on a cocoa farm was enslaved. Child labor. Environmental degradation. Economic impacts of a changing climate. There were plenty of issues to be aware of.

So…did this awareness ruin chocolate for me?

Nope. Quite the opposite. Now that I know more about chocolate, how it’s produced, where it comes from, and brands that concern themselves with the well-being of cocoa farmers, I actually enjoy chocolate more. I don’t eat mass produced chocolate (Mars, Snickers, etc.) any longer, not so much out of protest of their business practices, which are often worthy of protest, but more so to outwardly remind myself of my inner change. When you meet a modern-day slave, it should forever change you in a lot of ways.

(I write about quitting mass-produced chocolate here.)

Awareness has enhanced my life and not just as a chocolate eater.

WHERE AM I EATING led to eating local eggs, which taste way better, learning so much more about coffee and appreciating it more. WHERE AM I WEARING? made me aware of the harsh realities of the garment industry, but it also introduced me to brands positively impacting the lives of the people who make their products. I didn’t care much about labels before, but after my experiences meeting workers in Bangladesh, Honduras, Cambodia, China, and Ethiopia, I sought out ethical brands. Wearing them makes me happy and reminds me that there is good in the world and that I can be a part of that good.

All the above relate to things we consume and awareness of how they are produced. Shopping our way to a better world is so American, and the solution to a consumer can seem so easy. But what about issues like extreme poverty, genocide? Wouldn’t it be better to NOT know about the famine in Yemen? Wouldn’t it be nice to live in a fantasy world where we thought all humans lived happy, healthy, and fulfilled lives?

At times I’ve thought that it would be better to not know. Then I met Scott Neeson in Cambodia while I was researching WHERE AM I GIVING?.

Scott was a Hollywood executive who many would say had it all – a Porsche, a yacht, movie star girlfriends, and an annual salary of a million dollars. While traveling in Cambodia he had an experience that ultimately led to the selling all of his possessions, founding Cambodian Children’s Fund and moving to Cambodia where he’s been for 13 years. Each night he walks the edges of an abandoned trash heap where people live and face the harshest of realities.

Scott is happier now.

“I believe that the happiest you’ll be is when you find your groove and settle into it,” Scott told me. “I believe in the philosophy of Joseph Campbell.”

Joseph Campbell was an American mythologist who wrote about the common themes and journeys of mythical heroes.

Campbell wrote:

People say that what we’re all seeking is a meaning for life. I don’t think that’s what we’re really seeking. I think that what we’re seeking is an experience of being alive, so that our life experiences on the purely physical plane will have resonances with our own innermost being and reality, so that we actually feel the rapture of being alive. (From The Power of Myth.)

In Cambodia, Scott doesn’t appear to be living in happy circumstances. He works too much, and worries that he might get shot in the back. He confronts child rapists and deals with the aftermath. He has a folder of photos on his phone from the Child Protection Unit – a partnership between the police and CCF. Each photo is accompanied with a horrible story. When I was with Scott he scrolled through his phone and landed on a picture of a smiling girl who could’ve been one of the dancers at the CCF school we had visited.

“Attempted murder and rape,” he told me. “Guy tried to drown her. Held her underwater. She swallowed really nasty water and got a lungful of pneumonia and another infection. But we got them. These two really nasty people. They’ve gone away forever. Ah … horrible stuff.”

How is this happy?

The Dalai Lama wrote an editorial in The New York Times addressing our need to give to others:

…[R]esearchers found that senior citizens who didn’t feel useful to others were nearly three times as likely to die prematurely as those who did feel useful. This speaks to a broader human truth: We all need to be needed…Americans who prioritize doing good for others are almost twice as likely to say they are very happy about their lives. In Germany, people who seek to serve society are five times likelier to say they are very happy than those who do not view service as important. Selflessness and joy are intertwined. The more we are one with the rest of humanity, the better we feel.

Life in Cambodia helping kids and families of the dump is Scott’s groove, and it is full of meaning and purpose for him.

Researchers from Florida State University who compared happiness and meaning found that “[h]appiness without meaning characterizes a relatively shallow, self-absorbed or even selfish life.”

Meaning isn’t something that we find in ourselves, but only in putting ourselves and our gifts to work for others. This is true in our daily lives of abundance, or in the most extreme conditions you can imagine.

Viktor Frankl, an Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist, wrote about his time surviving the Holocaust and life in concentration camps, including Auschwitz, in his book Man’s Search for Meaning. Frankl acted as a therapist to his fellow prisoners, helping them find meaning in the senseless tragedy they all faced.

“Being human,” Frankl wrote, “always points, and is directed, to something, or someone, other than oneself – be it a meaning to fulfill or another human being to encounter. The more one forgets himself – by giving himself to a cause to serve or another person to love – the more human he is.”

When we become aware of something, we have the opportunity to act on that awareness. Not acting leaves us guilty until the hollowness of apathy takes hold. But acting on awareness gives us purpose, enhancing our lives.

Want to be happy?

Seek awareness. Accept responsibility. Act.

///

To read more about Scott, awareness, and purpose, check out my book WHERE AM I GIVING? A GLOBAL ADVENTURE EXPLORING HOW TO USE YOUR GIFTS AND TALENTS TO MAKE A DIFFERENCE

January 7, 2019

On Prom Night I was a Lucky Immoral Idiot

In high school I drove a black Firebird. It was a ‘93 Trans-Am, the first year for the curvaceous f-body, with a 275-horse-powered LT1 engine. The same engine the Corvette had. It wasmy dream car then and now. The license plate read: BATMBLE.

Batmobile. I’d be lying if it ended with the license plate. I had Batman floor mats. I had the soundtrack to the first Batman movie, the one with Michael Keaton, in the CD player. I loved blaring it on fall nights, leaves swirling where the Batmobile had been.

“You want to get nuts,” Bruce Wayne said to the Joker’s henchmen in the movie. “Come on let’s get nuts.”

I occasionally got nuts in the Batmobile. Like potentially life-changing nuts. One moment haunts me to this day.

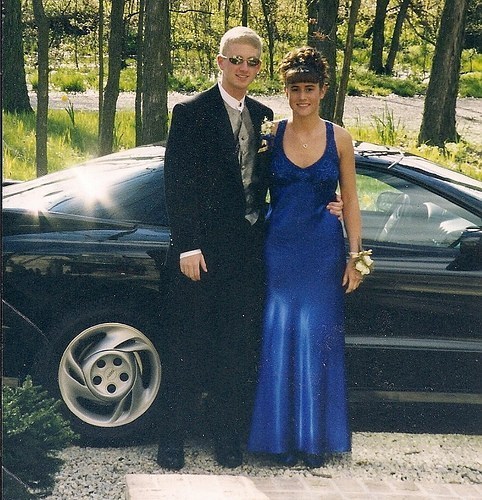

It was after my first prom. Annie, my wife was my date, of course because we were born together. A friend was following us and had the nerve to pass the Batmobile. What would Batman do?

I dropped the pedal and shot into the left lane across a double-yellow line up a blind hill. A cemetery sits at the top of the hill. People who we went to school with, people who died too young, were buried there. But I was seventeen. I was nuts. I was as invincible as Batman. I passed my friend going way too fast and luckily there wasn’t an oncoming car.

After the adrenaline subsided, the guilt crept in. I could’ve ruined or taken lives that night. I could’ve died. Annie could’ve died. I could’ve killed my friend who I passed or an oncoming car full of strangers. Twenty-years later there would be no Harper or Griffin. Just another memory of a teen driver too fast and reckless to live. I still think about that night and what could’ve been erased.

What I did could’ve led to jail time. I could be a criminal, a felon, but I’m not because I was lucky. Others haven’t been so lucky.

Let’s say another kid from prom did the same thing, but there was a car coming, and people died because of his actions. Am I any less guilty than him? (And yes, I’m gendering the driver in this example because guys are almost always going to be the idiots behind the wheel.)

This scenario is referred to as moral luck. I was just as much to blame as the driver in the example, but I was lucky that there wasn’t a car coming over the hill.

I was lucky when I texted while driving and a kid didn’t run in front of me. I was lucky in high school when I stole a road sign–government property–and didn’t get caught. I’ve been lucky and so have you. Yet we so easily feel morally superior to those who did the exact same thing we did, but who weren’t lucky.

That person’s life who got screwed up or who has been shunned from society could’ve been us.

Let’s not forget our flaws, our lapses in judgement and learn from them, and remember that many of us are lucky not to have them define our lives. Let’s have a bit more compassion for those who haven’t been so lucky. This isn’t to say that their actions shouldn’t be punished. Such behavior should be condemned to discourage it.

On prom night I could’ve killed myself and my future wife. It still gives me nightmares. I was immoral…an idiot…but a lucky idiot. If I wouldn’t have been lucky this picture wouldn’t have been possible….

—

Hank Green has a great Crash Course on Moral Luck –

January 1, 2019

On Climate Change: Finding Hope in the Lack of Hope

I went for a three-mile run down my Indiana country road yesterday on December 31st, 2018. It was 60-degrees. That’s not okay normal. It’s a terrifying new normal to which I still can’t adjust. Even though I knew the temperature, I still dressed for a December run.

I ran past a field of unharvested corn, each stalk broken or bent, sewed but not reaped.

I was hot and wished I had worn shorts…in December…in Indiana…while running outside.

The realities of our changing climate are no different than they were a few months ago, but humanity’s understanding of them has made the prognosis even more dire.

We’re now aware that the world is in worse shape than we thought it was.

The IPCC’s 2018 report states that “…pledges from the world’s governments to reduce greenhouse gases, made in Paris in 2015, aren’t enough to keep global warming from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees F).”

The IPCC predicts that the consequences of 1.5 degrees Celsius increase from pre-industrial levels, which we are on track to hit by 2040, are worse than previously thought: extreme heat waves, severe droughts, mass extinctions, and sea-level rise.

The average global temperature has already increased 1 degree Celsius, but just half a degree more may forever change our world.

Let’s add a few layers of pessimism on top of that.

The commitments to the Paris climate agreement have wavered. The Trump administration has pledged to pull out.

New leadership in Brazil is prioritising business over protecting the Amazon, long held as the greatest tool to fight climate change. Deforestation has increased 14% over the last year.

A two-degree increase will look like something out of a movie. Coral reefs…gone; an iceless arctic; parts of coastal cities like New York and Miami abandoned.

Yet through it all the IPCC leaves room for hope that we can have a different future, but it would “require large-scale transformations of the global energy–agriculture–land-economy system, affecting the way in which energy is produced, agricultural systems are organized, and food, energy and materials are consumed.”

Agriculture. Food. Reconnecting with land and nature. This is the prescription. Although the IPCC doesn’t necessarily espouse a reconnection, but more of reinventing.

Many of the solutions proposed by the IPCC involve out-engineering our way out of our predicament. As if the solutions don’t exist already. As if “synthetic protein” and “untested carbon removal technologies” and other new discoveries and technologies are our only hope.

Reminds me of a quote from Yvon Chouinard, founder of Patagonia:

“Technocrats tell us we can’t go backward, we can’t refuse technology, because then we won’t progress. We are told that life is increasingly complex, that’s the way it is […] If this is all true, then we are doomed.

Going back to a simpler life based on living by sufficiency rather than excess is not a step backward; rather, returning to a simpler way allows us to regain our dignity, puts us in touch with the land, and makes us value human contact again.”

We have a cultural problem that won’t just be fixed by business or science, but one addressed through a return to a culture more closely connected to food and land and people.

The ways of agribusiness–disconnecting us from food, focusing on the monetization of single crops, heavy use of inputs, and an over reliance on fossil fuels–is not sustainable. Yet this is the model that has been exported around the world. American farmers themselves–in the Midwest, which isn’t the most progressive of places–are questioning the ways of agribusiness.

An excerpt from The Guardian, “As climate change bites in America’s midwest, farmers are desperate to ring the alarm”:

“Oswald [a farmer] believes that denial is in retreat. Where farmers, including him, were once skeptical they now see the change with their own eyes. The problem is what to do about it.

“A lot of them will say there’s nothing we can do about it so we might as well not worry because we can’t have an impact, we just have to live with it,” he said.

But he said as climate change bites, farmers are increasingly accepting of the science as they are forced to spend more money on equipment and seeds to maintain current crop yields.

“It’s become almost an annual assault on their ability to produce good crops. So they are now starting to ask questions and I think are listening a little more to what the scientists are saying about the potential future.”

Reading the IPCC report and watching the headlines over the past few months haven’t exactly filled me with hope. At a time when we need to progress toward a solution, we seem to be doing anything but.

I don’t know if this makes sense, but I find hope in the lack of hope. It’s like we are in a lagoon of hog shit. When it was up to our knees we didn’t care, but now that it’s lapping our chins, we’re realizing we have to do something. I’m hopeful that now is the time we act. We all have to change.

Personally, I’m exploring planting warm summer native grasses on an acre of yard we don’t mow. I’ve reached out to the USDA’s National Resource Conservation Service – https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/site/national/home/ – for guidance. Native grasses have deep root system, which are better for the soil and also sequester more carbon. I’m also looking at implementing a tree planting strategy on our property. Our pond drains into a small stream that empties into the Mississinewa River. I plan on engaging with the Upper Mississinewa River Partnership to see how I can be a responsible landowner and encourage my neighbors to do the same.

Today I cut a vine in the woods and showed the kids how to swing down hill Tarzan style. We’ll be installing a zip line soon. It’s important to me that my kids connect with the outdoors. Of all the things I could do in the next year, this might be the most important.

I have a lot to learn, but we’re up to our necks in hog shit, so time to do something.

So, what steps are you going to take in 2019?

Suggested Actions

Donate to Cool Earth, a nonprofit that works alongside rainforest communities to halt deforestation and climate change – https://www.coolearth.org/

Calculate your carbon footprint – https://www3.epa.gov/carbon-footprint-calculator/

Learn about carbon offsets – https://www.carbonfootprint.com/carbonoffset.html

Start in your own backyard – https://www.patagonia.com/actionworks/#!/choose-location/

December 28, 2018

The Invisible Poor

Poverty, like death, is something that is all around us, but we like to pretend it doesn’t exist and could never happen to us.

Most cultures have prejudices toward the poor. I’ve noticed this when I travel. I’ve had translators in China and Cambodia who wondered why I would want to talk to people who worked in a factory or lived in a slum. I’ve had plenty of translators and friends who’ve said things like “They talk uneducated,” and they do things because “they don’t know better.” For many of my translators, the poor in their country are as invisible to them as the poor in my own had been to me until I started to volunteer. Researchers found that tourists on slum tours in India looked at slum residents as a positive part of a community and culture, while they perceived the homeless in their own communities as lazy or addicts. We are harsher critics of the poor in our own communities.

The narrative of the American Dream where if you work hard you will succeed lends itself to an undercurrent of the inverse: Those who don’t work hard aren’t successful, as if poverty is solely a condition of lack of effort.

We fear poverty; we are made uncomfortable by poverty. We judge people. We ignore people. We put the responsibility on the poor and not on ourselves, until we meet them.

How are you facing poverty in your own community?

—

Read more in Where Am I Giving?

December 12, 2018

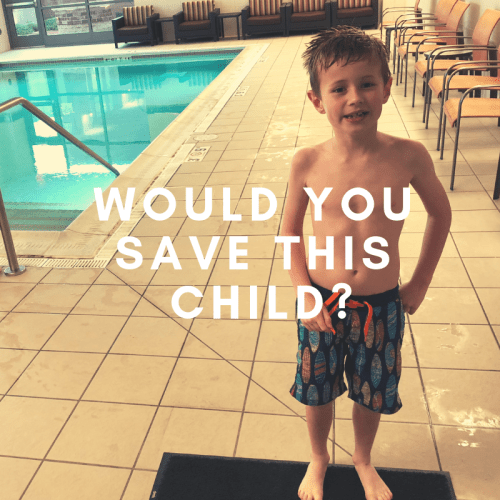

Would You Save This Child?

This is a pic of my son Griffin. I think you’d save him, if he needed saving. Why then do we ignore the preventable deaths of other children around the world when our actions would save their lives? This is a challenging question and one introduced to me by Peter Singer, author of The Life You Can Save.

This is a pic of my son Griffin. I think you’d save him, if he needed saving. Why then do we ignore the preventable deaths of other children around the world when our actions would save their lives? This is a challenging question and one introduced to me by Peter Singer, author of The Life You Can Save.

I present Singer’s thoughts in this excerpt of Where Am I Giving?:

///

I threw my cell phone, dropped my laptop bag, and ran as if my life depended on it. Part of me wanted to throw up or scream or both, but I needed to focus all of my energy on running as fast as I could.

Nothing else in my life mattered in that moment more than running.

The kids had followed me into the garage. Before I helped them into the car, I realized that I had forgotten my wallet.

Griffin, 4 at the time, is on the autism spectrum, and has a deep curiosity to explore places where he shouldn’t be — all of our cabinets, no matter how high, the top of the refrigerator, the inside of a stranger’s unlocked car, the tub of the dryer. You could say he’s part spelunker or mountain goat. In autism lingo, he’s also an “eloper.”

Here one second, gone the next.

I was pretty sure he wouldn’t bolt for the road and that I had enough time to grab my wallet off the counter and get back outside before anything bad could happen. I had assumed wrong.

Griffin wasn’t in the garage. He wasn’t playing outside the garage. He wasn’t on the swing. He usually takes two strides and does this little skip, as if he’s too footloose and fancy free to run full out, so he runs joyously. Not this time. He was running at a dead sprint down our long driveway to the road.

Dead. That’s what he would be if I didn’t get to him, I thought as I ran. But he was already two-thirds down our long driveway and I wasn’t gaining on him fast enough. The fencerow to the east of the drive would block the oncoming traffic from seeing him.

He made it to the road. I didn’t catch him in time. But luckily we live on a crumbling, country road in Indiana with very little traffic.

Griffin sat in the middle of the road and laughed. I was emotionally wrecked for three days.

Now I want you to imagine that you are standing on my driveway by the garage and you are holding your computer and phone. You see Griffin running to the road and you know he’s a kid that won’t stop. Let’s add a few certainties: 1) you’ll have to drop your phone and laptop to pursue him and they are certain to break if you do, destroying more than $1,000 of electronics; 2) there isn’t a doubt in your mind that you can catch him, but only if you drop your phone and laptop; 3) if you don’t catch him he is certain to be hit.

What do you do? Do you save Griffin?

I bet you would. I bet you wouldn’t think twice before sacrificing $1,000 of things to save a young child.

This thought experiment is one similar although not as philosophically pure as one ethicist Peter Singer put forward in his “drowning child” scenario in his essay Famine, Affluence, and Morality in 1972. In a later essay, he writes of how he uses the scenario in his classes:

To challenge my students to think about the ethics of what we owe to people in need, I ask them to imagine that their route to the university takes them past a shallow pond. One morning, I say to them, you notice a child has fallen in and appears to be drowning. To wade in and pull the child out would be easy but it will mean that you get your clothes wet and muddy, and by the time you go home and change you will have missed your first class.

I then ask the students: do you have any obligation to rescue the child? Unanimously, the students say they do. The importance of saving a child so far outweighs the cost of getting one’s clothes muddy and missing a class, that they refuse to consider it any kind of excuse for not saving the child.

He then asks his students a few more questions:

Does it matter if there are others around who could save the child but are not acting? The students agree that it doesn’t.

Does it matter if a child in similar life and death circumstance that could be prevented with your actions was in another country? The students agree that our obligation to save the child is the same: If our actions can save a life, then we ought to act.

I think most of us agree with that. But here’s where it gets challenging. Singer argues that there are children around the world who are dying preventable deaths, and most of us are doing nothing to save them. Remember that on average American’s give 2% of their income to charity and only 4% of that goes to supporting global causes. That’s less than $50 to helping save a kid’s life, or $950 less than the laptop and phone you dropped to run after Griffin.

Singer’s philosophies rooted in practical ethics formed the foundation of effective altruism, “a philosophy and social movement which applies evidence and reason to working out the most effective ways to improve the world.”

—

To learn more about Singer’s philosophies visit his site TheLifeYouCanSave.org.

December 11, 2018

Wanderlust, It’s a Wonderful Life, & Mom

(Mom and I with Safari Doctors in Lamu, Kenya)

A few years ago Mom told me that when she was in high school she wanted to be a travel writer. She graduated and went to a business college for a year before becoming pregnant. Mom and Dad got married in a ceremony I haven’t heard much about. They moved into a mobile home, but her life was anything but mobile. Dad worked construction and on his parents’ farm. Mom worked as a secretary for an auto manufacturer that has long since closed.

She lost the baby. His name was Michael. I’ve always felt some connection with him. If he had lived, would they have decided to have a third child after my older brother, Kyle, was born? Would I be here?

Mom and Dad only lived in the trailer for a few months. I wonder, what twenty-year-old Lynne was thinking in the mornings? At work? When you are 20 and want to be a travel writer, you want to move and never stop. Explore, but never too long in one place. I remember the ache of wanderlust and the fear of being stuck.

I felt every word George Bailey had to say in It’s a Wonderful Life:

“Mary, I know what I’m going to do tomorrow, and the next day, and the next year, and the year after that. I’m shakin’ the dust of this crummy little town off my feet, and I’m gonna see the world: Italy, Greece, the Parthenon, the Coliseum. Then, I’m comin’ back here to go to college and see what they know. And then I’m gonna build things. I’m gonna build airfields. I’m gonna build skyscrapers a hundred stories high. I’m gonna build bridges a mile long.”

George didn’t travel or build bridges. He built a life with kids and a struggling family business. His life wasn’t what he imagined, but he gave to his family and his community and they all became something they wouldn’t have if not for him. And Clarence the angel told him: “Strange, isn’t it? Each man’s life touches so many other lives. When he isn’t around he leaves an awful hole, doesn’t he?”

I learned to SCUBA dive when I was 13 in Ohio with Mom. The first time I left the country was to the Bahamas with Mom to take the plunge on our first open water dives. We did a shark dive, too. My nose bled into my mask and Mom didn’t freak out that much. She accidentally snuck me into a topless show at a casino. She was the first to expose me to a world beyond the rural Midwest. And more than show me the world, she was the first to teach me how to see it through the books we read, the news we watched in the morning, and the conversations we had. She believed in fairness, justice, and diversity.

By DNA, upbringing, or both, Mom passed her wanderlust on to me.

—

Want to read more? This was an excerpt from my book WHERE AM I GIVING? Get a copy.

Now, check out Mom’s dance moves…

October 23, 2018

Dear friend who doesn’t like to get political

Dear friend who doesn’t like to “get political,”

Farm bill. Food stamps. Farm subsidies. Food safety. Poisoned.

Eating is a political act.

Car emissions. Smog warning. Ozone action. Factory exhaust. Suffocation.

Breathing is a political act.

No music. Test teaching. Politician’s curriculum. Slashed budgets. Dumbed.

Education is a political act.

High premium. Expensive meds. Uninsured bankruptcy. Untreated. Preexisting until you unexist.

Health is a political act.

Farm runoff. Waste treatment. Lead water. Depleted aquifers. Parched.

Drinking is a political act.

Bears Ears. Natural parks. Algal blooms. Dying reefs. Homeless.

Recreation is a political act.

Trade laws. Labor rights. Underpaid. Overtime. Destitute.

Working is a political act.

Neighborhood watch. Stand your ground. Speed limits. Slow . . . at risk children at play.

Safety is a political act.

Unemployment. Social security. Disability. Promised entitlements. Uncertainty.

The future is a political act.

Museums. Public works. Heart appreciation. Examined life. How to see, think, feel.

Art is a political act.

You might not “get political,” but your life is political.

Vote! Visit vote411.org to find your polling place and view your ballot.

September 4, 2018

Speaking in Indy & Evansville this week

I’ll be speaking about WHERE AM I WEARING? at Marian University in Indianapolis tomorrow night 9/5. Doors open at 7. Details here – https://events.marian.edu/events/#!view/event/event_id/6761

And I’ll be speaking about WHERE AM I GIVING on Thursday, 9/6, at the downtown Evansville Vanderburgh Public Library at 7 PM. Details here – https://events.evpl.org/event/922843

The gift of a teacher

Before I turn in a book manuscript to my editor, I turn it in to my high school English teacher, Dixie Marshall. She’s my best and most trusted editor. And also, I suppose, I’m trying to make up for all the assignments I didn’t turn in as a high school student.

There was the group project on King Arthur where we turned in our “notes” and it became apparent that none of us were taking the assignment seriously.

There was the summer reading group. Mrs. Marshall selected me and a few other students for a group she hosted at her house . . . in the summer! Did I mention this was during the summer?

We had recipe boxes filled with blank index cards, each representing a book we were going to read and discuss as a group. She was preparing us to think for ourselves and engage in conversations that would take place in a college classroom. Our first assignment was Tale of Two Cities. We met twice. I didn’t read it.

Acknowledgements

I wrote this in the acknowledgements of my first book WHERE AM I WEARING:

If everyone had an English teacher like mine, the world would be a better place and much more grammatical. Kyle [my brother] and I once bumped into my English teacher, Dixie Marshall, at a play. [It was an one-man performance in which John Astin was Edgar Allan Poe]. She introduced us to her sister as such: “This is Kyle Timmerman, one of my best students ever,” and turning to me, “…this is his brother Kelsey.” Even so, she never gave up on me and continued to teach me about gerunds and split-infinitives a decade after I last sat in her class. She poured over the manuscript countless times with her red pen.

I wrote this in the acknowledgements of my second book WHERE AM I EATING:

My high school English teacher, Dixie Marshall, was one of the first to read this entire manuscript. I’ll never be able to make up for not turning in my term paper on King Arthur, but here’s to trying! Thanks, Mrs. Marshall! How is it that you get younger by the year?

But then I wrote a book on GIVING, and since I mailed the manuscript to her on her vacation in Florida, which she edited in two days, I’ve started to think about my friendship with Mrs. Marshall through the lens of GIVING.

When I didn’t complete the King Arthur assignment or read Tale of Two Cities I’m sure she was disappointed in me, but I don’t remember her disappointment. What I remember is what it was like to have someone who wasn’t family believe in me.

She sent WHERE AM I GIVING back along with a message on logistics. That’s all I saw. I turned in my assignment to my teacher and she didn’t give me any overall thoughts, stickers, or a “way to go kiddo.”

This time she must be disappointed.

A few days later I saw the note she had written me after the logistics. The note I had missed. For WHERE AM I GIVING I received blurbs from authors, philosophers, and change-makers, but none of their thoughts on the book meant as much as the words of Dixie Marshall my high school English teacher.

By the way, I believe this is the most important book you have written and may ever write. It’s really an impressive book, a valuable book, and one that everyone should read. You are really inspiring, Kiddo. You are someone who has more than lived up to his potential.

WHERE AM I GIVING was a journey. It covers 15 years of travel, but the bulk of the work was done starting in June of 2017, and I turned the manuscript over to my publisher in March of 2018. That’s not much time. It was a taxing book to write physically and emotionally. And her words fell on my heart like a sigh of relief that turned to joy. Her words, like her edits were a gift.

Yet somehow, during the literal 11th hour of the day of my deadline, I was writing the acknowledgements for WHERE AM I GIVING, and I didn’t mention Mrs. Marshall. I didn’t even realize the oversight until my mom received her copy of the book in the mail. I was sick.

Of all of the people to leave out and of all the books to leave her out of . . .

I met Mrs. Marshall and her husband for dinner last month to give her a copy. I told her about the oversight. Again, I don’t remember her disappointment in me. I remember her being proud of me. I remember her words of encouragement.

Her character and commitment reminded me of the graduation gift she had given me 22 years ago.

A Graduation Gift

Somehow despite multiple moves across various states and decades, I came across the graduation gift Mrs. Marshall gave me shortly after I finished writing GIVING. It’s a book of quotes–A Hero in Every Heart: Champions from all walks of life, share powerful messages to inspire the hero in each of us.

In June of 1996, on the first page of the book she wrote, “See page 76.”

Page 76 was a quote from Captain Scott O’Grady, a pilot who was shot down in Bosnia:

“It wasn’t the reward that mattered or the recognition you might harvest. It was your depth of commitment, your quality of service, the products of your devotion–these were the things that counted in a life. When you gave purely, the honor came in the giving, and that was honor enough.”

There are certain people you want to make proud. Mrs. Marshall is one of mine. It is important to me for her to see that her belief in me and investment of time were worth it.

Our lives are shaped by the gifts of others, people making small and large impacts that seem to embed into our DNA and change the course or our lives. Unless we recognize the people who have shaped our journey, we’ll think we arrived on our own. The best way to show gratitude for them is to allow their gifts to flow through us.

With the Mrs. Marshalls in all of our lives we can never repay or acknowledge their gifts proportionally. We can only honor them by giving to others.

I had Mrs. Marshall in school for two years, but she’ll always be my teacher.

September 3, 2018

Do you tip the barista when they aren’t looking?

Has this happened to you?

You place your coffee order and by the time you find a buck or two for the tip, the barista has their back to you. You look at the hand-decorated, ornamented tip jar and pause. Do you drop in the tip while no one is looking, or do you wait to get “credit”– a “thank you” for your “thank you.”

What did you do?

Does a tip fall into a jar if there is no one in the cafe to see it? Does it count? Of course it is counted at the end of the day. But in that moment, it’s not counted as your act of gratitude.

But are we tipping to enhance our own status or tipping to support someone else? Is tipping about us or about them?

In WHERE AM I GIVING I have a few Giving Rules (which are really just suggestions and sometimes contradict one another) that apply to this scenario.

Giving Rules: A gift should be given without expectation.

Giving Rules: Giving isn’t about you.

Each of these points support dropping in the tip while no one is looking.

I’m a bit of a boy scout, literally, and like to think that my altruism is internally motivated. Although, I’m afraid I have a bit too much self-pride in this regard. I’ve dropped the tip in while no one was looking, but not before reminding myself that I’m the kind of person who does acts of good and doesn’t need recognition. But I feel like having this thought makes it no less of an act of ego-driven altruism than waiting to be seen tipping.

However, there is another Giving Rule that supports waiting.

Giving Rules: Giving should connect you.

Your $1 may mean less to the barista than the in-person appreciation of the work they do.

I relied on tips when I was a SCUBA instructor and dive master in Key West. I received a $100 tip for finding a diver’s underwater camera that floated away and a $0 tip from a man whose life I saved. So I recognize there are a lot of awkward thoughts, feelings, and philosophies around tipping.

So, do you tip when no one is looking?