Michael C. Taylor's Blog, page 10

September 17, 2020

Mortgage Forbearance in CARES Act

With national unemployment spiking this spring at 14.7 percent and climbing – and severe hardship in certain sectors like hospitality, tourism, oil and gas, and retail – the need for mortgage relief is also high, and climbing.

Anticipating this trouble, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act passed March 27th granted some relief for mortgage borrowers.

Three unequivocal benefits for financially stressed mortgage borrowers granted by the CARES Act are:

You likely qualify for automatic mortgage forbearance with your bank, simply by askingThe forbearance agreement with your bank will not be reported to the credit bureaus, potentially protecting your credit score and credit report, andResidential foreclosure procedures are all temporarily frozen, at least until May 18th. Evictions are not enforceable until at least July 18th.

If you must suspend or lower your monthly mortgage payments because the COVID recession created a household financial emergency, then this relief is welcome.

Nationwide mortgage relief like this is rare, because banks really, really, like to be paid on time, every month.

[image error] [image error]

The passage of time is strange right now in the COVID pandemic, right? What does “on time” even mean? For example, everyone acknowledges the month of April lasted, like, 5 years.

My man Benjamin Franklin wrote in The Way To Wealth about how time passes, depending on whether you primarily lend money or borrow money.

“Creditors have better memories than debtors; creditors are a superstitious sect, great observers of set days and times,”

Franklin wrote back in 1758.

For debtors with a mortgage, however, time passes differently, says Franklin.

“If you bear your debt in mind, the time which at first seemed so long, will, as it lessens, appear extremely short: Time will seem to have added wings to his heels as well as his shoulders. ‘Those have a short Lent, who owe money to be paid at Easter.’”

Anyway, as another mortgage payment day approaches on winged heels, forbearance options seem particularly important right now. If you have to ask for a break right now, you have to ask for a break.

[image error]

The CARES Act says that if you have a home mortgage with any kind of federal backing – whether from from the Federal Housing Authority, or Veteran’s Administration, US Department of Agriculture or the mortgage insurance giants Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac – then you have the right to request forbearance on your mortgage. Very few people have a mortgage not administered in some way by these federal institutions, even if you didn’t know it already. Only a small percentage of private mortgages would not qualify for automatic forbearance under the CARES Act.

Out of curiosity, I looked up my own mortgage on the specially-created Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac websites for this purpose and found that indeed mine is covered by Freddie Mac, so I would qualify for forbearance if I chose to.

Incidentally, you may wonder why – if you only deal with your own bank and never with Fannie or Freddie – your mortgage shows up as qualifying on their websites? It’s very likely because your mortgage has been packaged up by Wall Street and sold into a mortgage bond that Fannie or Freddie guarantees.

Anyway, I found I have the right to request a fairly automatic forbearance on my mortgage, and so do you.

What would that look like? Forbearance comes in different flavors. Simply by stating financial hardship, and without having to present evidence, I could cease payments for a 180-day period. Then that could be extended by another 180 days at the end of the first period, at my request.

In addition, banks are forbidden from charging extra late fees or penalties, beyond the normal interest rate. Further, your bank is obligated by CARES – and subsequent guidance from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau – to report a loan in forbearance as “current” to the credit bureaus, rather than delinquent for non-payment, as it normally would. So, even while not paying your mortgage for 6 months or a year, your credit would be fine.

Heck, this sounds so good, it’s a wonder anybody pays on their mortgage anymore!

Not so fast. If you have some assets and income and were wondering about entering into a forbearance agreement in order to get strategic financial relief, the CARES Act is not a great deal, according to Wendy Kowalik of financial consultancy Predico Partners.

One version of forbearance you can get is a 3 or 6 month payment suspension, followed by a lump sum payment at the end of that time period to get back on track. That probably isn’t what most people expect. And it’s totally unaffordable to most.

Wells Fargo, the largest mortgage lender by volume in 2019, offers a weblink to an extensive question and answer page on mortgage forbearance under the CARES Act.

According to the Wells Fargo FAQ, maybe missed payments would be only due a long time from now, but it’s equally clear that that is only one possibility, among many.

Says Kowalik, “every conversation I’ve had – the assumption is that of course they are going to tack payments on to the end of the mortgage,” meaning 10 or 15 or 25 years from now, at the end of a mortgage term. “But if you have any liquidity, the likelihood is the bank will require you to pay the lump sum to get current on your mortgage right away.” That should worry most people considering a forbearance request.

Another version is a repayment plan that divides up the missed payments into a 3, 6, or 9 month repayment schedule. But that higher mortgage payment may then also become unaffordable. And prior to repayment, it will not be possible to draw further on lines of credit, or even to refinance the mortgage, without curing the forbearance.

[image error]Wendy Kowalik of Predico Partners

A key point that Kowalik worries borrowers are not considering is that the banks themselves set the terms of repayment. If your bank decides your assets or income can handle it, they will demand faster repayment. Failure to comply then could affect your credit. None of the CARES Act protections extend past a year, which means that the normal enforcement mechanisms – credit reporting, foreclosure, and eviction – are all back on the table a year from now, if not sooner.

Kowalik thinks borrowers who have a choice should be very wary of putting themselves into temporary relief that will cause even more hardship within a year. Understood that way, the CARES Act is quite bank friendly after all, in the sense that they can set the terms of repayment.

The key, says Kowalik, is this.

“Don’t go into this lightly. It looks like assistance. It looks like a simple answer to help me with my current cash flow, but that may not be the case. There is a lot of devil in the details, and I would hate for people to get surprises.”

“And about the Wells Fargo website that says ‘We want you to know we are here to help,’ Kowalik said, “Well, that just about killed me.”

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express-News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts:

An interview with Wendy Kowalik

Book Review: The Way of Wealth by Benjamin Franklin

Post read (7) times.

The post Mortgage Forbearance in CARES Act appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

September 16, 2020

The COVID Revolution

With the great economic freight train of spring 2020 brought to a screeching halt by COVID-19, our usual supply chains buckled, broke, and then fell off the tracks.

Our normal ways of satisfying our needs disappeared. In the midst of a scramble over the past month, in some ways we went back in time. In other ways, we went forward in time.

I reacted to shortages at the grocery store by getting in the habit of ordering a dozen eggs weekly through my gym, which has a connection to a local farm. The eggs are very delicious, and very expensive, compared to grocery store-bought eggs. I feel very close to the land!

I admire on social media my friends and relatives home-sewing their custom face masks from old scarves and bandannas. Stylish! Unique! Hand-crafted! It’s all very Etsy.com.

I bought a 5-gallon bucket of hand sanitizer from a friend who converted his whiskey distillery to the task.1

So the question becomes, will the legacy of COVID-19 be a return to a slower pace of economic life, recognizable from a century ago? A life full of locally-sourced eggs, hand-sewn clothing, customized distillery products and of course quality time with a small family unit? Seen from a certain angle, it’s all very Little House on the Prairie. Is that our post-COVID future?

No, that fantasy is silly. That train left the station long ago.

[image error]

What’s happening instead, and what will remain after, is a jump-start to new ways of doing things.

In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions philosopher Thomas Kuhn argues that big change comes not as a slow evolutionary process, but rather in sudden paradigm shifts. What we’ve all experienced and observed in the last month of social distancing is a massive jump forward – maybe by many years – into the future of certain economic processes. Below are just a few trends that COVID-19 will rapidly accelerate. COVID-19 causes this paradigm shift, rather than evolutionary change.

The revolution in education

Online learning this month has offered an insight into the future of school and learning. For the first three week of school shutdown, the public elementary school where my fourth grader attends has worked on providing technology to all of her classmates. That technology procurement was necessary because it’s impossible to start online work if kids in the class can’t get connected. So administrators have rushed to acquire and distribute iPads, hotspots, and internet access for families for whom that was previously out of reach financially.

Before COVID-19, they could never do much with online learning, because too many families would be left outside the digital divide.

Having solved that tech problem over the past three weeks, however, new online learning methods, assignments become both possible and necessary.

With the education world forced to adapt so quickly and so universally, will education ever be the same again? Will universities, for that matter, ever be the same? It feels like COVID-19 has forced a paradigm shift in what’s expected of teachers, schools, and kids.

The revolution in payments

I already used the touchless Apple Pay service before now. But I’ve noticed, to my frustration, that a huge number of retail establishments – like my local grocery store chain – never have the right kiosks to accept payment this way. If we understand that bills and coins are a germ-filled disease vector, and even that exchanging credit cards with a cashier is too much contact, then the contactless Apple Pay represents the future. COVID-19 may mark a sudden paradigm shift away from cash.

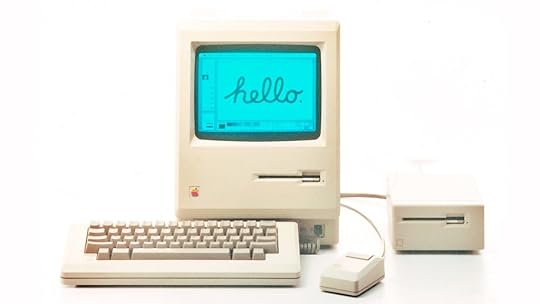

From Apple, in 1984

From Apple, in 1984Apple, as always, sees the future before the rest of us do.

The revolution in retail.

Did we think Amazon’s deliver-to-the-door business model already threatened brick-and-mortar retail before 2020?

Of course. But the only reasonable observation to make now is that Amazon has accelerated its take-over of retail businesses in America. Much more brick-and-mortar retail will now die, much more quickly, in a step-change paradigm-shift way, not in an evolutionary way.

From the distance of time, let’s say two decades from now, my freight train economy analogy that I began this column with will seem even more quaint, and even more apt. We will look back at spring 2020 – before the COVID-19 transformation – and see the way we did things in 2020 as impossibly inefficient. Impossibly brutal, dumb, loud, linear, and tracked. Like a freight train that can only go from one point to another. So limited.

Our sleek, smart, creative, rocket ship economy of 2040 will have blasted off from 2020, no longer held back, no longer limited, by the rails of a freight-train economy.

Note: This post ran in the San Antonio Express News in April 2020…I’ve just been remiss in posting my stuff on Bankers Anonymous! Forgive me.

Please see related posts

The coming death of brick and mortar (2016 edition)

A small whiskey distillery near The Alamo that is also a family legacy

Post read (1) times.

Next request to the distillery: Please hook me up with a 5-gallon bucket of moonshine to tide me over during this period of isolation, as I spend large amounts of indoor quality time with my family. ↩

The post The COVID Revolution appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

Social Security in COVID – Research and Ideas

Adding to a vast ocean of unrelenting bad news, let’s explore some troubling research into the fine print on Social Security benefits.

Andrew Biggs, a resident scholar of the American Enterprise Institute, has two papers out this Spring with interesting implications on our most important safety net for retirees.

American Enterprise Institute

American Enterprise InstituteOne paper has bad news for a particular cohort of soon-to-be-retirees. The other explores an idea for helping with current financial distress. I personally think his proposal is wrong, but worth discussing.

Biggs wrote in a recent paper that for a group of soon-to-retire folks – specifically those born in the year 1960 – the COVID recession could be very hurtful to their benefits claimed in 2027, at full retirement age.

In his paper, Biggs assumes the 2020 US gross domestic product (GDP) shrinks by 15 percent in 2022, and that average wages also drop by a similar amount. The net effect of this drop in average wages – as a mathematical input into the Social Security benefits calculations for people born in 1960 in particular – will drop benefits by 13 percent overall. If that happens, for a medium-wage worker born in 1960 in particular, Biggs calculates an annual and ongoing hit of $3,900. For that same medium-wage worker, lifetime social security benefits drop by a present value of $70,193 due to the 2020 COVID effect.

The math justification behind Biggs’ claim isn’t obvious unless you enjoy building your own Social Security benefits spreadsheet.1

The math trick to know is that before calculating your first benefit check, Social Security indexes your annual earnings to a national wage index – rather than an inflation index, as you might expect.

Andrew Biggs

Andrew BiggsIf the wage index declines by 15 percent in 2020 (Biggs’ assumption), then this national wage indexing of 2020 earnings has a substantial negative impact on your benefit checks starting at age 67. Subsequent retiree benefit checks do increase according to inflation, known as the Cost of Living Adjustment. But if benefits start at a low base, for example, they will remain permanently lowered, even as they move upward with inflation over the years.

An economic recovery may mean later cohorts do not suffer this same temporary drop. Biggs recommends Congress consider interventions to protect this specific born-in-1960 cohort.

The COVID recession – depending on its duration and lasting effects on national wages – may also affect near-retirees born in 1961. So that’s your not-so-great news of the day on COVID.

Biggs also has written another paper in April 2020 which should be filed to the “interesting, but bad idea” pile. In the midst of our national discussions around stimulus payments, Biggs and his co-author Stanford Economist Joshua Rauh propose allowing pre-retirement individuals to take loans from their future Social Security benefits, which could be paid back at retirement age.

For context, private lenders do not make loans specifically collateralized by future social security payments. But Biggs and Rauh propose the federal government become that type of lender.

If a not-yet-retired individual decided to take a $5,000 check now, the authors suggest, the borrower could pay that loan back at retirement age by simply delaying owed benefits until the loan is repaid.

Part of the benefit to borrowers, Biggs and Rauh argue, is that the federal government could offer extremely low interest rates, knowing that it can recoup the money at the individual’s retirement date. This low interest rate helps the individual who could not otherwise borrow cheaply. In addition, warming the cockles of an economist’s heart, this cash infusion can be made budget neutral. Money paid out today during the crisis will be repaid, with low interest, by the worker at retirement.

In their scenario analysis, they show that most workers 45 or older who borrowed this way would likely only delay taking their social security benefits by three months, based on a $5,000 loan made today.

In simplest terms, Biggs proposes a mechanism for financially-strapped workers during the COVID recession to access their social security benefits early, with the obvious implication that they will have less later on, in retirement.

If enacted, (Narrator: this won’t be enacted) this form of pre-retirement loan would clearly impact the most vulnerable folks – people who have no other source of savings.

In general, I like considering any so-crazy-it’s-possibly-good wonky financial idea. But this is more like a so-crazy-its-possibly-terrible financial idea. I can’t endorse robbing future Peter to pay present Peter as a humane way to solve a short-term financial crisis.

When I am declared the National Personal Financial Benevolent Dictator (NPFBD) sometime in the future, I have a few different plans for Social Security. Different from both the current plan and Biggs’ suggestions.

My plan eliminates the need for complicated math and indexing as mentioned by the first Biggs paper. In my plan, basically, everyone gets the same amount of money. It doesn’t matter what your average 35 best earning years are, indexed for wages, then further adjusted for cost-of-living, then made progressive by counting different percentages of a specific workers’ earned wages. That’s a description of the current complicated math, simplified.

Instead, in my simple plan you get, say, $32,000 a year. Or whatever flat amount we choose. Everyone gets the same amount. No math. Congratulations, you’re 67. End of story.

If your lifestyle is above that cost, so be it. You should save some money now so you can maintain your lifestyle. If your lifestyle is below that cost, so be it. You’ll feel rich in retirement.

The complicated math we currently do for social security benefits is a very convoluted way to express a couple of wrong ideas. By wrong ideas, I specifically mean the ideas that:

1. We ‘earned’ our social benefits by a lifetime of working, and

2. If we worked more or harder or got paid more, then we should get a bigger chunk of cash in retirement.

I understand the implications of not doing any tailoring of benefits to individual workers and retirees. I understand why the current system feels “fair” to many. But I think the benefits of simplicity outweigh those implications, leading to a fairer outcome overall.

A spokesperson for the Dallas office of Social Security Katrina Bledsoe said they do not comment on projections or proposed policies, so declined to respond to my query about Biggs’ ideas.

Biggs responded to my query that he is very confident about the math behind his warning about the cohort of near-retirees born in 1960. His biggest doubt is whether the national wage index will actually fall by the estimated 15 percent – a sharp decline – or whether that’s too steep an assumption. At this point – not yet halfway through 2020 – we just don’t know yet.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News.

Please see related post:

Running for Personal Financial Benevolent Dictator

Building Your Own Social Security Spreadsheet

Building Your Own Social Security Spreadsheet, Part 2

Post read (2) times.

Whoops, guilty as charged! ↩

The post Social Security in COVID – Research and Ideas appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

September 7, 2020

Video: Buying Your Dream Home

Part of the series of 10 personal finance videos I made with public television station KLRN – This one focuses on home buying.

There’s the same content, but in podcast form if you prefer…

And, of course, if you like text, we’ve got that too.

Linked to here on the KLRN site.

Please see related posts:

The Rent vs. Buy Debate, resolved

Post read (0) times.

The post Video: Buying Your Dream Home appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

Texas, Inc.

So, anyway, how are finances for the State of Texas going these days?

[Editor’s Note…this post ran in the newspaper in the beginning of July 2020]

Pretty well, thanks for asking.

If you were to whiteboard the best financial practices for a big state, you would want three things. First, you would want transparency, both for officials making decisions as well as for citizens paying taxes. Next, you would want a conservative match balance between expected revenues and expected spending. Finally, you would want to ensure those revenues stayed strong and steady throughout an economic cycle.

In Texas, we’ve actually got significant amounts of financial transparency, which I’ll describe below. We’ve also got a conservatively-matched balance sheet, for specific reasons worth remembering.

Unfortunately, with the COVID-recession, there’s a lot to worry about when it comes to ongoing revenues. But, as Meat Loaf used to sing, two out of three ain’t bad.

Damn that’s a great album cover

Damn that’s a great album coverActually, that last statement is a bit exaggerated for the purposes of making a late ‘70s rock reference, so let me qualify a bit. I expected to find financial devastation at the state level, but instead found merely areas of concern.

Let’s start with the transparency part. The State Comptroller’s office supports a website all you Texas taxpayers should know about, called the State Revenue and Expenses Dashboard. This lets you create color-coded visualizations of all state revenues and expenses from 2011 to 2020. The “picture is worth 1,000 words” idea is that we can intuit changes over time, and relative sizes of fiscal categories, by building with and working with a visual dashboard that shows exactly what categories we want it to. The tool also lets you download data into a spreadsheet for further nerdy fun. Which I have done. And, oddly enough, enjoyed.

Some initial insights you can get from the Comptroller’s visualization tool.

Transfers from the federal government are the largest single source of state revenue. (Sorry for you folks who believe in the sovereignty and self-sufficiency of the state.)The biggest source of locally-derived revenue is retail sales taxes, at 57 percent of taxes in 2019, and 26 percent of all state revenue. This means state revenues will be impacted by recessions, like this one.Oil extraction tax and gas extraction tax revenue is smaller than I expected, at about 3 percent and 1 percent of all state revenue, respectively.

A related page on the Comptroller’s website, the “Monthly State Revenue Watch” shows state taxes and other revenue sources updated monthly.

I know this is updated in real time because I checked it on July 1st, and the June 2020 numbers were already inputted. Impressive! So here is where we can get an idea of how well or how badly things are going in 2020.

Texas runs on a September 1st to August 31st fiscal year, meaning we have two months left in the year. Which further means we already know ten of the twelve months’ worth of numbers, to see any shortfalls versus budget projections.

If you were a worrying type person, you would ask questions like how badly the retail recession, and oil and gas industry disruptions, plus drops in hotel occupancy and car sales and car rentals might wreck state budget projections.

Tax revenue is down, it’s true. But it has not fallen off a cliff. Yet. Retail sales taxes are the largest single tax source, at 57 percent of all taxes. Collections through June are up slightly from 2019, although on track to fall short of the budget by about $2 billion of the projected $35.6 billion, on a total tax revenue base projection of $61 billion.

Again, because we can see ten of the twelve months of the year already, we can see from the transparency website that revenues will fall short by approximately $2 billion in franchise taxes and maybe $1 billion in a combination of oil and gas taxes, with smaller effects in other areas.

While this is not perfect and possibly a bit frightening, transfers from the federal government are already $4 billion above budget, with two months to go. So we could imagine this will roughly balance out this fiscal year ending in August.

I’m going through this partly because it is interesting on its own, but also partly to point out that the online transparency tools of the Texas state government are kind of awesome.

Now a word about the fiscally conservative setup of state finances in Texas.

Texas sets its state budgets two years in advance. Future state government spending depends upon a Comptroller estimate – known officially as the Biennial Revenue Estimate (BRE). This is due at the next legislative session in 2021. Unlike the federal government, Texas is highly constrained from borrowing at the state level.

The Comptroller, by constitutional mandate, must sign an oath to certify that the BRE contains accurate revenue forecasts for the next two years. The next legislature must, again by constitutional mandate, produce a spending plan that does not exceed expected revenues in the BRE.

Spare a moment to imagine the difficulty for the Comptroller of signing this next BRE. Like, there are so many different possible economic scenarios in 2021 as a result of the COVID pandemic.

Financial forecasting is extremely challenging right now. The chief financial officer of any given company must be pulling her hair out trying to estimate future revenue, but at least a private company can kind of wing it on future projections, and then borrow as needed, if things go awry. The Texas Comptroller may not wing it. And there are huge constraints on borrowing. The result has been conservative fiscal state management, which is good. The result in the future – I fear and expect – is a pretty austere two-year revenue projection and therefore spending plan beginning in 2021. This won’t be fun.

Between a pandemic, a recession, and specific oil and gas industry woes – not to mention the 17-year locusts and murder hornets surely set to arrive any moment now – I had expected worse financial numbers for Texas. Can we be blamed for flinching into a reflexive crouch of endless worry in 2020? With strong transparency and a fiscally conservative set-up, I feel a bit better about Texas, Inc, having seen the state’s transparency tools.

It’s safe to expect budgeting next year will be tougher than this year.

A version of this ran in the San Antonio Express News.

Please see related posts

Post read (3) times.

The post Texas, Inc. appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

August 21, 2020

Hater’s Guide To Tesla

With Tesla announcing plans to build a manufacturing plant in Central Texas – and with the possibility of company headquarters arriving as well – many in this state will rejoice. Not me.

Tesla is the worst. And Elon Musk, Tesla’s CEO? He’s awful too. My hatred for both the company and the CEO burns inside me with the heat of ten thousand SpaceX rocket launches.

My reasons for rage range from the profound to the petty. I’ll list them in that order. Tesla, how do I hate thee? Let me count the ways.

Taxpayer Subsidy for Private Enterprise

Del Valle ISD offered $46.4 million in tax breaks for the privilege of hosting Tesla’s new manufacturing facility. Travis County commissioners approved other goodies, for an announced total package of $60 million. Will the state’s Texas Enterprise Fund be far behind in offering public subsidy for private enterprise?

In return, Tesla plans to employ 5,000 workers at a salary of $35,000 per year. In other words, poverty wages for a family of 6. And this was celebrated by Governor Abbot and other Texas leaders? But see, it’s already obvious Tesla moved here precisely because they could pay their workers $35,000 a year! We shouldn’t have to pay Tesla an additional $60 million dollars in public subsidy for the thing they planned to do already.

And anyway, why does a CEO with an estimated net worth of $70 billion demand to take money from Del Valle public school kids – 85 percent of whom are economically disadvantaged – for his company’s bottom line? Because he can. Because there is no shame anymore in late stage capitalism, as practiced by Elon Musk.

Thanks Mr. Musk! Please sir, may I have another?

Electric Vehicle Subsidies

A debate rages over the past four quarters whether Tesla is profitable over the past year, or whether it is still losing money at this time. What is not debatable is that the only way the firm can report a profit is because – for regulatory reasons – other car manufacturers are forced to purchase “regulatory credits” from Tesla. Because other companies do not produce enough electric cars in their fleet, according to federal government regulations. Tesla booked $782 million in payments from traditional auto manufacturers in the first half of the year. Tesla reported a profit of $16 million in Q1 and $104 million in Q2 2020, meaning it would show a loss without the “regulatory credits” forcibly paid by its competitors.

Tesla’s entire business model to date has been built on government subsidies. From the $1.2 billion to build a battery plant in Reno, to the $7,500 EV car purchaser credits (now phased out for Tesla.) Without them, they’ve never been profitable. Can we stop publicly subsidizing a $270 billion market cap company, please? Again, something about capitalism has broken here.

Accounting Shenanigans

Elon Shrugged

Elon ShruggedFundamental investor David Einhorn of Greenlight Capital wrote a scathing analysis in his August 4th quarterly investment letter about Tesla’s accounting practices in 2020. All but accusing the firm, and Musk, of fraud, Einhorn writes:

“We question whether TSLA’s accounting, which does not appear to correspond to the creation of regulatory credits through auto sales, transfers of those credits to a counterparty nor payment for those credits, conforms to GAAP accounting.”

The bottom line from Einhorn is he thinks Tesla is cheating, in order to show a technical profit for 4 quarters in a row, which will allow the firm to be included in the S&P 500 index. “Through what appears to be sheer abuse of the accounting rules, TSLA has now contrived reported profits to make it technically eligible [for S&P 500 inclusion].”

Einhorn goes on to predict Tesla’s future crash along the same trajectory of the June 2020 catastrophic fraud of WireCard (WDI) following its inclusion on the German stock exchange (DAX) “As with WDI and the DAX, we expect the TSLA parabola to end around the speculated inclusion in the prestigious S&P 500 Index.”

Stock Valuation

I’ve made exactly one forward-looking “market call” on an individual stock in my 6 years of writing a newspaper column. I wrote about Tesla in 2015 as a company “I’m reasonably certain will be dead in five years, despite its $25 billion market cap.”

Ha-ha the joke’s on me, because I revisited that call in January 2020, to point out that its growth to a $100 billion market cap was even more ridiculous.

A mere half-year later, the stock switched into ludicrous mode (probably as a direct result of karma from my once-only-ever market call.) The company is now valued at $270 billion. Keep in mind this nearly tripling in value happened amidst a global recession and pandemic. The lesson, as always: I am an idiot. I burn with special hatred for Tesla specifically for making a mockery of my considerable investment skills and business acumen.

Tweets

CEO Musk uses Twitter all day long for lying, bullying, distracting, and constant salesmanship.

When criticized for his PR stunt regarding kids stuck in a cave in Thailand in 2018, Musk replied to the critic over Twitter with unsubstantiated slander: “Sorry pedo guy you really did ask for it.” 1

In the face of critics who pointed out the precarious financial position of Tesla in 2018, Musk lied about a taking-Tesla-private deal “Am considering taking Tesla private at $420. Funding Secured.”

Am considering taking Tesla private at $420. Funding secured.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) August 7, 2018

Lying, bullying, and distracting over Twitter doesn’t make Musk unique among leaders in the world in 2020. But Musk’s style reminds me of the unquenchable narcissism of another lying, bullying, distracting salesman who has an important job to do but who nevertheless chooses to spend his day on Twitter.

Cars.

I hate cars. I get it, people like Teslas. They look cool and they zoom fast. Wearing my personal finance hat, I have tried my best to convince my children (and anyone else who will listen) that paying a premium for a cool car makes as much sense financially as paying a hefty premium for a cool washing machine and dishwasher. They are all just rapidly depreciating metal and plastic consumer goods. (To be clear, I mean cars and household machines, not my children.)

Cars are a bad use of your money. They shouldn’t be cool. Harumph.

7. His Name

“Elon Musk.” Even his name. It sounds like a brand of splash cologne you get for 3 quarters inserted into the gas station lavatory vending machine. Just a few notches in quality below “Axe” fragrance. I’m sorry. My disgust stacks up on itself. If Tesla and Musk were a supper plate, for me they would be black olives and anchovies, garnishing a plate of pan-seared liver. My senses reel with disgust.

Am I being petty? Yes, you’re damn right I am. I’m so Tom Petty right now that I’m Free Fallin’ and I Won’t Back Down.

A version of this ran in the San Antonio Express News.

Please see related posts:

Sin Investing (and my 2015 market call on TSLA)

Tesla as an example of difference between Castle in the Sky and Fundamental investing

Tesla is Stupid (But, it turns out, I am stupider)

Post read (18) times.

He later deleted this one from Twitter ↩

The post Hater’s Guide To Tesla appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

Video: Build Financial Health and Wealth

Earlier this year I did a 10-video series on personal finance for local PBS affiliate KLRN.

Here’s a link to one of the short videos on building financial health and wealth.

If you like your financial information in podcast format, we’ve got that too.

Also, as text.

Enjoy!

Post read (6) times.

The post Video: Build Financial Health and Wealth appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

August 18, 2020

Tesla Stock – Zoom Zoom

NOTE: This post ran in the newspaper in February 2020, but for completionists’ sake I’m posting it now, to accompany yet another “I hate Tesla” post that follows.

You know that feeling when you’re driving through a city downtown in your brand-new Tesla, and a long series of traffic lights turn green, block by block, all in a row, just as you approach, and you think to yourself “Yes! Finally, my magic powers have come in!”

That is just how I feel about my TSLA market prognostication in my post in late January, except my magic works in the complete opposite direction. It’s as if by calling for TSLA shares to fall, I personally managed to push the stock to new, previously unimagined heights. It’s quite a power I apparently possess.

Between my anti-Tesla stock January 26th column and last night’s close (2 week’s later) the stock has soared from 564.82 to 734.7, a gain of 30%. 1

The company value as measured by market capitalization has jumped from 100 billion to 132 billion in less than two weeks. Year-to-date, the stock is up 75% as of last night, and briefly closed up 100% on the year. This is…insane. 2

If we could bottle up my magic skill in market picking – you just invest the exact opposite way from what I call – then we could all be retired billionaire investors by this time next year.

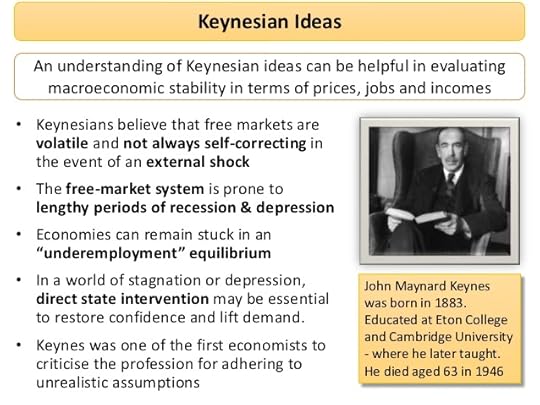

But the price action also provides another great opportunity for reviewing important stock market investments concepts. Like short selling. The madness of crowds. Castles in the air. And investment luminaries like John Maynard Keynes and Burton Malkiel.

Early 20th century economist John Maynard Keynes gets credit for stating that “the market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.” He also famously described that the point of investing was not so much to decide what you think something is worth, but rather what other people in a crowd will think something is worth in the future.

[image error]

In Burton Malkiel’s excellent book A Random Walk Down Wall Street Malkiel explains two distinct ways to value stocks: the “fundamental value” method and the “castle in the air” method. Both have their advantages and disadvantages. Warren Buffet is our modern champion for valuing stocks on a fundamental basis. Depending on how you interpret Tesla’s January 29th earnings announcement and to what accounting regime you ascribe, Tesla just reported its first annual profit, or just barely missed. In any case, it’s close to profitable for the first time in ten years. Applied to the Tesla situation, we know that fundamental value analysis cannot apply, however, relying as it does on tracking a consistent pattern of profits and the reasonable expectation that profit will continue into the future.

By contrast, the castle in the air theory of stocks says that the most important thing to know about a stock is what other people think of it. This method relies on the wisdom (or madness) of crowds. Stock markets trade on future expectations. It isn’t necessary for a stock to be profitable now, but rather it is necessary for sufficient numbers of other people to think it will be profitable in the future. As long as enough other people believe in the future of a stock, it is a perfectly fine investment practice to build a castle in the air.

Anyway. Obviously Tesla is a castle in the air stock. We should drive one mile further along this racetrack, however, to understand the crazy last week of the stock, and it’s crazy price action so far in 2020.

The key thing to know to explain the price action is that Tesla is the most shorted large stock in the market. Shorting means that investors – typically hedge funds and brokerage companies – have sold the stock without owning it, on the expectation that the stock will go down in the medium term. If it does go down, those same investors can buy back shares at a lower price to close out their position. They profit by selling high first, then buying low later, and pocketing the difference.

Shorting Tesla has always made fundamental sense because the darn company has never reported an annual profit – at least until, arguably, January 29th this year.

Shorting a stock that goes up, however, causes losses. If you sell a stock at 100, only to watch it go to 130, you’ve suffered a loss of $30 per share. Also, whereas buying a stock has limited downside, shorting can lead to unlimited losses. If you buy a stock at $100 that goes to zero, you’ve lost 100 per share. It’s a loss, but one that’s capped. at $100 per share. If you short a stock at $100, what if it then goes to $1,000? You’ve lost $900 per share. If it keeps going up beyond that, you have the possibility of infinite losses.

This is all background to explain the price action of Tesla in recent weeks. Large institutional fundamental value investors have long hated Tesla. With good reason! But they have to operate in a castle in the air world. Traders at banks and hedge funds always have risk limits and they also always have managers. At a certain point, managers look at a losing short position and tap the trader on the shoulder. “Sorry buddy, you may be right in the long run, but you need to shrink that position or close it out entirely.” The result is forced buying to close the short position, just as the stock is rising.

The reluctant hedge fund trader buys the stock at a high price, locking in the loss. The forced buying in turn creates a vicious cycle of higher prices, and more forced buying from others. This disequilibrium lasts until the shorts are sufficiently at a neutral risk position, or metaphorically squeezed, dead, or fired.

In this way, a short squeeze is the inverse of the kind of forced selling we last saw in the broad stock market between September 2008 and March 2009. Many institutional investors – like brokerages and hedge funds – didn’t want to sell stocks on a fundamental basis at that time. But the risk managers came along, saw the falling prices, and tapped the traders on the shoulder. “Sorry, buddy, you need to unload all of your positions by Friday. Also, you’re fired.”

Evil genius and Tesla CEO Elon Musk knows all about the short sellers who doubted his company. He taunted them last Summer. He promised on Twitter the “burn of the century” for Tesla short sellers.

Oh and uh short burn of the century comin soon. Flamethrowers should arrive just in time.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) May 4, 2018

He then mailed a package of “short-shorts” to famous fundamental value hedge fund investor David Einhorn of Greenlight Capital, who had bet against Tesla stock through short-selling.

I want to thank @elonmusk for the shorts. He is a man of his word! They did come with some manufacturing defects. #tesla pic.twitter.com/qsYfO8cbkp

— David Einhorn (@davidein) August 10, 2018

In this investment battle between castle in the air and fundamental value, Musk has crushed his competitors, stolen their sheep, and salted their land.

A final reminder of the most important lesson of all. Never invest in individual stocks, or forecast their direction. You might not be as bad as me, but you’re probably not as good at it as you think you are.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express-News

Please see related posts

Sin Investing Can Be Good (and also, Tesla is bad)

Book Review: A Random Walk Down Wall Street by Burton Malkiel

Post read (12) times.

This stock tracking from newspaper columns 2 weeks apart is quite quaint, given what happened subsequently ↩ Haha the “insane” joke is on me because it blew through $300 billion market cap within a few months. ↩

The post Tesla Stock – Zoom Zoom appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

August 6, 2020

Coins – For Collecting, Not Investing

I’m visiting my parents on Cape Cod this month. My father recently turned 90, and my mother decided to open the long-buried safe where my father kept his coin collection. This offered a brief moment of Geraldo Rivera-type drama. What treasures, buried for decades, would we discover? Tune in after the commercial break…

Ok! We’re back! And…

Al Capone’s vault: also disappointing

Al Capone’s vault: also disappointingThe haul fills less than half a shoe box. Mom got a quote from their local coin and stamp shop. This long-buried treasure is worth $728. At least, that’s what the dealer would pay for it. Smaug’s glittering horde this is not.

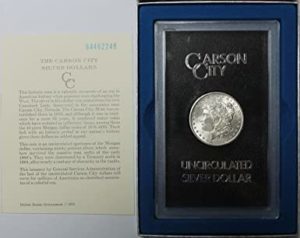

For nerdy numismatists among you, I’ll briefly describe the coins: a ¼ ounce gold coin; an 1877 U.S. Trade Dollar; two Carson City Morgan Silver Dollars (uncirculated, 1883 and 1884), five Peace Dollars, circulated from 1891 to 1934; three Spanish Carolus III Reales, ranging from 1784 to 1806; and two French Indo-China coins, issued a little more than 100 years ago.

I spent some time trying to figure out how much this little collection would cost to accumulate today. I checked Ebay.com, but also specialist sites like Coinquest.com, Greysheet.com and ApMex.com. And then some books I’m about to mention.

Peace Dollar

Peace DollarThe collection would cost between $1,300 and $1,600 to put together.

In other words, the quote from the dealer is about half what it would cost to acquire the collection.

I bought two books at the dealer’s shop, a blue-covered “Handbook of United States Coins 2021: The Official Blue Book 78th Edition” and a red-covered “A Guide Book of United States Coins 2021: The Official Red Book 74th Edition.”

Both books have the same author and the same publisher. Both provide a comprehensive catalogue — lists upon lists upon lists — of coins and prices. They are basically the same book, with one crucial difference. One is for collectors (retail) while the other is for dealers (wholesale).

The issue comes down to what the finance world knows as the “Bid-Ask Spread.” In other words, the difference between how much retail purchasers pay to acquire the asset — the “ask”— and how much dealers will pay to take it off your hands — the “bid.”

This is what the uncirculated Morgan Dollar looks like

This is what the uncirculated Morgan Dollar looks likeComparing the blue and red books side by side is fun. It would cost you about $39 to acquire my father’s 1927 silver Peace Dollar (the ask.) But the dealer will pay just $21 for the same coin (the bid.) It would cost you about $210 to acquire my father’s 1884 Morgan dollar (the ask.) But the dealer would pay just $150 for the same coin.

Sometime in the 1980s, probably at the same time gold prices were rising rapidly, my father became interested in coins. A mania for precious metals and coins has long cursed unsophisticated financial minds, like my father’s, but interest spikes particularly in moments of increased fear — such as the recession in the early 1980s. And also after gold and silver increase rapidly in price. In other words, moments like this one. Which makes his lapses of financial judgment in the 1980s relevant for us in the 2020s.

The problem with coins as investments is not that they are inherently fraudulent, per se. The idea that a dealer will charge an extraordinarily large bid-ask spread is not the same as fraud. Bid-ask spreads, in many cases, are fine. The issue is a question of degree, as well as a question of unequal information. Smaller spreads are obviously better for the purchaser/investor/collector, while bigger spreads can be better for the dealer. Assets with a huge bid-ask spread, like collectible coins, become inappropriate in part because of their inefficiency in trades.

Unequal information about the bid-ask spread gets to the heart of where mere inefficiency slides gently, maybe imperceptibly, into fraud. If the purchaser/investor/collector does not know that a huge big-ask spread exists and likely will persist in the future, rendering the asset extremely inefficient, then we should worry about fraud.That was one of the issues in the multi-state enforcement action against precious metal marketing company Metals.com earlier this year. They targeted the credulous and frightened, mostly elderly conservatives who watch and read right-wing media, and mercilessly charged markups so large that they constituted fraud.

My father’s own coin collection, as it exists in 2020, I mostly consider harmless. I mean, it wasn’t a good investment. But there’s an aesthetic and maybe intellectual pleasure to collecting old things, and that’s fine. My view is that because of their historical and aesthetic significance, his coins are preferable to accumulating a thousand dollars’ worth of Beanie Babies. Although it is, admittedly, more difficult to hug coins than Beanie Babies.

[image error]

Coins don’t work well as investments. But they are OK as collectibles, I guess, because people like what they like.

The details had been a bit lost in family history, but my mother told me that, in fact, my father and his business partner had been defrauded on coin investments in the 1980s. My father’s memory is not good anymore, so I called up his old partner, now 80, to find out more.

A well-trusted accountant had introduced them to a pension advisory group, which helped them invest some of the firm’s pension in rare coins, approximately $50,000 worth, according to my father’s partner. Around the time they figured out that a motel investment (also totally inappropriate for my father and his partner’s level of sophistication) had gone sideways, they were contacted by the state attorney general investigating their pension advisor.

Unsurprisingly, in the end, they had paid huge markups on their coins. My father’s partner estimated they took a 30 percent loss on that portion of the pension, in the course of cutting ties with the advisor. That actually sounds to me about what one would expect, even with no outright fraud. That’s pretty much just the bid-ask spread. The motel was a larger percentage loss on a bigger investment. In the end, employee pensions were made whole on the losses, but my father and his partner took losses in their own pensions — as the business owners who should have known better.

Seems about right.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News.

Please see related posts:

Metals.com – The Long Con and The Short Con

Texas Bullion Depository – What Exactly Is The Point?

Post read (8) times.

The post Coins – For Collecting, Not Investing appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

July 3, 2020

The Great Economic Leap Forward Experiment

While medical researchers race against time to find effective treatments for COVID-19, we have launched ourselves headlong into an economic experiment in federal policy on effectively treating a recession.

The experimental treatment so far is the recently signed $2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. Money for big businesses. Money for small businesses. Money for individuals. Is it too much? Is it not enough? Will it prove to be – in a phrase now used in many contexts – “a cure that’s worse than the disease?”

A primary mission of mine – as a writer – is provide language and categories around which we can discuss financial matters, as citizens. In vastly simplified terms, we could identify 3 theoretical approaches to fiscal and monetary policy in response to a COVID-induced recession, from the right, the middle, and the left.

On the right, the Austrian School and its most famous 20th Century theoretician, the Nobel Prize-winning Freiderich Hayek, would encourage limited government spending and a cautious central bank, in favor of freedom, individual action, efficiency, and ever-vigilance around inflation. Writing in the middle part of the 20th Century, Hayek warned against creeping Socialism and the centralization of economic power as threats to humanity. Bank lending of fiat currency – rather than relying on the solidity of an anchor-currency like gold – tends to artificially lower interest rates and overly expand the money supply.

The policy implications of the Austrian school is to interfere the least in business cycles, as they will work themselves out over time.

In the middle, policy makers advocate along themes established by John Maynard Keynes, who argued for a combination of robust government spending and easy money from the Central Bank, originally in response to the Great Depression of the 1930s. Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, a careful researcher of the Great Depression, followed that playbook in the 2008 Great Recession. And I would say – from a monetary policy standpoint when all was said and done – very successfully.

The left has recently coalesced around something known as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

Just as the Austrian school of thought and Keynesianism have variations, so too does MMT. But simplifying a bit, the big unifying idea of MMT is that governments that print their own currency like the United States do not have to worry tremendously about the problem of paying back debt. Controlling an unlimited supply of money can free policy makers from worries about a finite source of capital, or the classical economists’ worry of “crowding out” private borrowing and private enterprise. Both fiscal policy (taxing and spending) and monetary policy (the supply of money and interest-rate setting) should respond to problems by making money much more available, aggressively where needed. In stark contrast to the Austrian school, MMT points to a massive intervention of the government in the economy.

A key point of MMT – a point in which I am in agreement – is that debt owed by a government is not exactly like debt owed by a household or a business. Households and businesses do not create their own currency, so must always have a reasonable plan for repayment, or risk being shut down or punished by having assets seized by creditors. Governments that create their own currency, by contrast, need not fear creditors in quite the same way as households and businesses.

MMT theorists, accused of disregarding inflation, have argued that in periods of low inflation – like we’ve seen in recent decades, and like we usually see in recessions – policy can focus on more immediate threats, like underinvestment and unemployment.

I’ve been thinking about some of this in part because a conservative friend and reader handed me a copy of Freiderich Hayek’s The Road To Serfdom on March 18th, during what might be the last sit-down meal at a restaurant we will enjoy for months. Hayek’s worldview (or permit me to smoothly roll ‘Weltanschauung’ off my tongue) in simplest terms, is that the biggest enemy confronting society is government control of economic activity.

So where are we currently on the spectrum of policies – from the Austrian right, the Keynesian center, or the MMT left? As of this month we’re neck deep in a massive MMT experiment. That’s not what Congress and President Trump said out loud as they passed the CARES act. They would all deny it, if asked. But just to be clear: that’s what we’re all doing. The CARES Act was the most MMT experiment our country has ever tried. And it’s still early days yet in the COVID recession. As a betting man, I’d say more is coming.

And the weird thing was the near-unanimity of it all. Which also makes me nervous.

One reliable indicator of problematic policy in a democracy is unanimity, or near-unanimity of votes. Problematic because unanimity generally indicates votes forcibly taken, votes taken in fear, or votes taken under emergency conditions.

Like elections in the old Soviet times, in which the winner would earn 99% of the vote. Or like the Patriot Act of 2001, which passed the Senate by a vote of 98-1 in October 2001, following the attacks of September 11th.

We similarly saw the passage of the $2 trillion CARES Act by a 96-0 vote in the Senate, and the absence of anything other than a voice vote among a quorum in the House of Representatives, without a recording of who voted how. Friday March 27 was a weird day in Washington.

So Tea Party folks, just to clearly review. Your party – with a unified Republican Congress and Presidency – passed the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, expected to increase the federal deficit by $1.4 trillion, according to the Congressional Budget Office. The CARES act just passed – by a divided Congress and Republican President – will cost $2 trillion. What we should all agree on right now is that there is no fiscal and monetary conservative party in the United States. It does not exist. We’re all unified MMT leftists right now. I guess we’ll find out in a few years how we like it.

Not that we necessarily had a choice.

Would I have voted yes for the CARES Act, were I in Congress that day? Yes.

Do I think we’ll be instituting a form of Universal Basic Income within 6 months? Yes.

Do I think our fiscal and monetary policy might be a ticking time bomb – both because of our debt levels and inflation – for the United States? Also yes. [LINK to column on government debt spending:

Please see related posts:

We’re getting UBI and we’re never going back, after 2020

Government Debt – Ways to Think About it.

Post read (7) times.

The post The Great Economic Leap Forward Experiment appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.