Michael C. Taylor's Blog, page 11

June 29, 2020

Video: Good Debt Bad Debt – It Just Makes Cents

Earlier this year I did a series of videos/blog posts for TV Station KLRN.

Over the next month or three I’ll post them here. This one is on a theme I’ve delved into before, namely that debt is like a drug, for better and worse.

The text of this post – if you’re a word rather than video person – is linked to here, as one of my 10 “It Just Makes Cents” blog posts.

They even did podcast versions of the audio, which is also cool.

Please see related post:

Post read (13) times.

The post Video: Good Debt Bad Debt – It Just Makes Cents appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

May 18, 2020

How’s Your Small Business Going Lately?

What do you do when your business is forcibly shut down from one week to the next, as has happened to first every bar and restaurant owner, and then every other so-called “non-essential” business?

I gathered anecdotal data from Bryan Potts, a San Antonio-based CPA and the owner of CFO2Go, who primarily serves restaurants with consulting and accounting services. It’s been rough. Potts says he lost 75% of his client base in March.

With doors forcibly shut, many of his clients simply can’t pay him. Of his restaurant clients, Potts estimates that 10% are hanging on to their employees in the shutdown, while 40% have cut back as much as possible to just a few essential employees. About 50% of his clients have simply laid off all of their employees.

To begin to get a sense for the scale of the hit to employment numbers this month: The Texas Restaurant Association counts 50,000 restaurants in the state, and counts 1.4 million Texans in the restaurant industry.

In a related story, US weekly jobless claims have hit catastrophic levels every week since late March.

Back in the good old days, in December 2019 – which feels like a decade and a half ago – I sat down with Ryan Salts of the small-business resource center Launch SA.

Salts’ passion and profession is to support entrepreneurs and would-be entrepreneurs as they launch, survive, and then hopefully thrive as business owners.

This Spring, however, is not at all like the good old days. Salts invited me to listen in, as he gathered together entrepreneurs online on Zoom in a part advice-giving session, part therapy session. Potts was not on this call, although he is part of Salts’ mentoring network.

A different mentor on the call – who asked not be named – described the process of filing with the Texas Workforce Commission for a “full company” claim of unemployment. This would streamline the process for her employees, all of whom she assumed would need to apply for unemployment benefits.

A question among the group arose: Is it time – as the classic entrepreneurial wisdom says – to “pivot” your business model? Not necessarily.

Many restaurant owners, for example, have opened up grocery stores, or boosted their take-out and delivery businesses. Customers want this and encourage this, and employees may feel grateful for the ongoing work. But this could be – in fact it probably is – a money loser for restaurant owners. And the result of operating a money-losing pivot over the next few months could be further debt for the owner down the line when normalcy returns.

One of the Zoom participants was Jeni Spring, from The Center For Barefoot Massage. She said a widely suggested pivot runs counter to her business. She runs a San Antonio-based continuing education center to train massage therapists in deep tissue technique. In this lockdown, she’s received advice and pressure to move to an online training model for massage therapists nationwide. But that, fundamentally, is not something she believes in.

I hadn’t ever heard of them either!

I hadn’t ever heard of them either!“We can’t become something we are not. It doesn’t work to move to online training, since our entire reason for being is that you have to learn massage in person. You simply can’t learn the sense of touch needed to give professional massages online.”

So, the “pivot” is a mixed bag.

What about the other solutions business owners bandied about following the lockdown – such as offering gift cards, as a kind of down-payment on future business that would help finance the present?

Salts offered a cautionary tale.

“I have a downtown friend. He won’t make it through this. His normal traffic is foot traffic. of the first things I thought last week was “’why don’t you do gift cards?’”

“But everything is changing so fast that recommendations from earlier in the week change day to day.” His friend didn’t feel gift cards were ethical, Salts explained, “given that he was of the mindset that he had a 70% chance of not surviving the downturn.”

In December, Salts and I had talked about how hard it is, even in the best of times, for food service businesses to survive. I was curious about a spate of high profile restaurant closures in my neighborhood at the end of last year.

Salts was philosophical and realistic, based on his work with Launch SA: “Are food people good business people? On average? No,” he’d said then. “They’re really good at what they do. They’re creative. They can put together a good menu. But can they run their accounting? Can they cost things out?” That was December.

Now, of course, none of that matters. The best restaurant owner in the world cannot stay open against the COVID-19 lockdown orders.

About the restaurant businesses now shuttered, Salts has an extremely dire prediction.

“Probably 50% of the places that close their doors right now are not going to reopen when this thing is over. Every single person I work with is in a dire situation of triage.”

And with those shut-downs, we are learning, painfully, how essential these small businesses are. Everything is interconnected. As Potts explained: “It shows how far small business employers contribute to the economy. It’s everything from people who clean out the grease traps to lawyers and accountants. I don’t think there’s anybody that’s not been affected by restaurants shutting down.”

Disclosure: I do occasional consulting projects for the non-profit small business lender LiftFund, which partners with the City of San Antonio to run Launch SA.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express-News.

Please see related post:

Post read (2) times.

The post How’s Your Small Business Going Lately? appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

May 15, 2020

Meditations On The 100 Year View

Something was very different this Spring. A once-in-a-century type of event.

Did you notice it? Many centuries ago, the Mayans could have told us.

The vernal equinox came early – March 19th. The earliest in more than a century. Don’t blame carbon emitters or the COVID-19 virus. The earth’s natural rotation means that an equal amount of night and day hit all US time zones earlier in the year than at any time since 1896.

I understand: the early vernal equinox was not on the top of your mind. But I’m trying to zoom out our short-term focus to ponder a bit on the big picture here. The one-hundred-year view.

During this first week of Spring, can we talk a little bit about stock market gyrations? And then meditate on interest rates as well?

In the spirit of meditation, the Judeo-Christian tradition provides a metaphor for stock performance. By contrast, the path of interest rates and bonds, metaphorically, follows the Hindu-Buddhist tradition. I’ll explain what I mean by those metaphors later on, as I understand I’m saying something that sounds a little kooky.

What’s happening in the stock market these past two months is not new. It’s a hundred-year flood that periodically recurs, well, about every ten years. Let’s try to see the larger pattern.

What’s happening in interest rates, by contrast, is totally wild. Uncharted territory. There is no past precedent for these moves.

In an interview with the BBC in 2009, Charlie Munger – the Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway and famously Robin to Warren Buffett’s Batman – laid out a concise version of the correct hundred-year view of stocks.

“I think it’s in the nature of long-term shareholding, of the normal vicissitudes of world outcomes, of markets, that the long-term holder has his quoted value of his stocks go down by say 50%,”

said Munger during the interview.

Even beyond the utter normalcy of this kind of volatility, Munger says the periodic 50% drops determine who will be rewarded.

As Munger continued, “In fact you can argue that if you’re not willing to react with equanimity to a market price decline of 50% two or three times a century you’re not fit to be a common shareholder and you deserve the mediocre result you’re going to get compared to the people who do have the temperament, who can be more philosophical about these market fluctuations.” Munger has 96 years and $1.7 billion to back up his wisdom right there.

So, stock market fluctuations like this past week are normal. Carry on as you were. Do nothing different. If you can, maintain regular automatic contributions to your portfolio.

Incidentally, this recent volatility is a reminder of why owning individual stocks could generate bad investor behavior (trading frequently) whereas owning broad indexes of stocks could generate good investor behavior (doing nothing in the face of volatility). Heading into a recession, we can easily see why any particular business will get crushed. We can’t help but have an emotional reaction to a particular story of a particular company. But a broad index of stocks, heading into a recession, maybe inspires us to remember that over the next few decades a few thousand of the best-run and most innovative companies in the world will figure out ways to generate profits, and therefore a return on investment. Indexes help us worry less about any particular story and to focus on the longest time horizon possible.

The stock market, understand as a whole, follows a linear path through the medium term. It sure doesn’t seem that way, especially this past month. We humans with our hominid brains want to take note of a every single up and down movement, like baboons tracking a particularly delicious, but peripatetic, insect on a tree branch. Up, down, up, up, up, down.

The up and down is an illusion, however, as the stock market, again as a whole, goes upward with each decade. In the long run, over a century, the stock market understood as a whole, follows first a linear, and then an exponential upward, path. In the longest run, a basket of stocks is unidirectional. Birth, life, and then an ascent into the infinite. That’s what I mean by the metaphor of the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Meanwhile, interest rates typically act more like the Hindu-Buddhist tradition of a circular path. Sure, rates change a little bit over time, but they always tend to loop back upon themselves. Unlike stocks, interest rates resemble a wheel. A cycle of birth, death, rebirth and reincarnation. We don’t ascend or decline too much over a century. We don’t depart from the wheel. Except this month, we did.

Holy Cow! 1

Anyway, rates recently have been anything but normal. We’ve never in US history seen interest rates this low.

As Covid-19 panic set in mid-March, thirty-year US government bonds hit 1% mid-day, while 10-year government bonds hit 0.5%, albeit briefly. We’ve seen 0% overnight Fed Funds rates before, but even in the 2008 Great Recession, long-term US bonds didn’t hit these low rates. This all indicates panic in the financial system. For what it’s worth, the Fed’s move to carpet bomb financial institutions with liquidity following unprecedented interest-rate lows seems appropriate to me. We do not want the wheel to break.

Finally, the vernal equinox again. Few of us alive today will live to see another March 21 vernal equinox, which will not happen until the year 2101. What else will be never-before-seen between now and then?

A link for those who don’t follow the Old Farmer’s Almanac assiduously.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Post read (4) times.

Thanks very much, folks, I’ll be here all week with even more Hindu-tradition jokes. ↩

The post Meditations On The 100 Year View appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

May 12, 2020

Hurricane Harvey Macro and Micro Impact

Two and a half years after Hurricane Harvey slammed the Texas Gulf Coast, the first surprising thought is how quickly the Texas economy has recovered, and how quickly households have recovered.

Houston underwater after Hurricane Harvey

Houston underwater after Hurricane HarveyAccording to the governor’s report on the storm impact, the estimated $125 billion in losses made this the second-costliest natural disaster ever in the United States. (Hurricane Katrina’s impact on New Orleans in 2005 was the only costlier disaster.)

And yet, the state comptroller’s office estimated the impact on state economic output – the equivalent to GDP but for Texas – estimated a 3-year net economic gain of $800 million, due to Harvey

A big temporary hit to state income in year one following the storm – estimated as a $3.8 billion loss – is actually made up for by the spur in economic growth by the need to rebuild in years two and three, estimated at $2.1 billion and $2.5 billion respectively. It’s a stunningly healthy macroeconomic recovery from a major economic shock, with obviously a lot of variation across the state.

Researchers have also used the experience and time since Harvey to study the economic effects on the finances of households, what we could think of as the microeconomic impact of the storm.

A paper released in mid-February by the Federal Reserve of St. Louis and written by economists at the University of Colorado explores the rates of bankruptcy and rates of access to federal financial assistance by affected households in Houston following Harvey.

St. Louis Fed Building, 1924

St. Louis Fed Building, 1924These economists studied household recoveries to see whether – underneath the average strong recovery of households – what kind variation existed. They found a few significant variations.

They show that two types of households weathered the financial hit of Harvey the best: People who happened to live inside the designated floodplain – presumably already forced to be covered by flood insurance – had lower rates of bankruptcy.

They also found people in any part of the city in a strong financial position ahead of time were able to access more federal resources in the form of small grants and larger loans. That finding may have implications for program design in the future.

The authors found no overall change in the level of bankruptcy in the city of Houston, following Hurricane Harvey. Digging into specific circumstances and specific city blocks, however, they did see relatively large jumps in bankruptcy among certain groups.

A big jump in bankruptcy rates occurred in areas of high home ownership where they also measured folks with relatively low access to credit.

That seems a bit counter-intuitive at first, since we associate home ownership with wealth, and renting with less wealth.

The intuition here, I think, is that compared to homeowners, renters have less at stake – between home equity and personal property – when a severe flood hits. Homeowners with low home equity and low access to credit, however, can see their net worth reduced drastically without a fix. So bankruptcy rates spiked in high homeownership neighborhoods, following this sudden drop in wealth.

The biggest observed jump in bankruptcy rates occurred in areas outside of the natural floodplain, rather than in city blocks inside the floodplain.

The explanation there is that homeowner rates of flood insurance outside of the floodplain are low, estimated at 17% flood insurance coverage in Houston, prior to Harvey. Again this is probably because in the case of having a home flooded without flood insurance – like folks outside the designated flood plain – bankruptcy is a far more likely outcome for someone just having had their net worth devastated.

Homeowners inside the floodplain, most of whom would have had to have insurance in place, recovered financially much more quickly. In fact, bankruptcy rates overall declined among homeowners in the floodplain whose blocks experienced the heaviest rates of flooding. We can presume this is because flood insurance provided a big chunk of liquidity when it was needed most, lowering the probability of bankruptcy.

The authors next studied who in Houston got access to federal assistance – mostly from FEMA and SBA – in the months following the storm.

Coming from a higher income area of Houston, the authors found, correlated with a higher likelihood of assistance. It also correlated with a higher dollar amount of assistance, even controlling for the amount of property damage reported. I think it’s obvious to say that federal assistance does not set out – from a policy perspective – to reward people in a disaster who are better off financially, before the disaster.

On the other hand, this result could be explained intuitively by one of the big rules of personal finance. Namely, it helps to have money in order to get money. In the specific case of grants and loans, we can imagine barriers which folks in lower socioeconomic neighborhoods face in applying, following up, and qualifying for federal assistance.

The fact that households who are worse off to begin with benefit less than the better off – following a devastating financial shock – suggests that policy makers have some program design to consider, for when the next big disaster hits.

This post ran a few months ago in The San Antonio Express-News and Houston Chronicle.

Post read (7) times.

The post Hurricane Harvey Macro and Micro Impact appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

May 11, 2020

Credit Score Cities

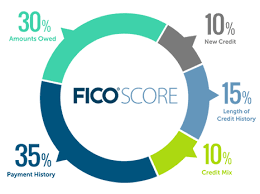

When comparing the economic health of cities, I’m interested in credit scoring becoming a more mainstream tool for measurement of financial health. A recent WalletHub study, which I’ll describe below, kicks off a comparison between Texas cities. Beyond intramural municipal competition, however, it seems regular measurement of the accessibility of credit should stand alongside other measures such as household income and wealth, for policymakers and others.

WalletHub recently posted the average credit scores among 2572 cities in the United States. You probably want to know where your city ranks, at least among Texas cities, right? FICO scores range from 300 to 850.

Austin – that eager-beaver city full of high achievers – ranks highest among Texas cities and the 62nd percentile nationwide, with an average credit score of 712. That tells me that the average person in Austin can get a prime mortgage and car loan, enjoying the lowest rates of interest.

El Paso and San Antonio cluster down at the 20th percentile (not so good!) with median credit scores of 662 and 661 respectively. The cities of Houston and Dallas are further down the list, at the 18th and 16th percentile nationally, and with median scores of 659 and 658 respectively. In each of these four cities, the average person is not qualifying for low-interest home and low-interest auto loans.

Among large cities in Texas, Corpus Christi trailed all others, with a 12th percentile ranking nationally and a median score of 652.

Meanwhile, Corpus Christi people are like, “hey, at least we’ll always have Atlantic City, in the 2nd percentile, with a median score of 614!” (Now listen, everyone, comparisons are odious. Every city is special in its own way. Also, Atlantic City is not in Texas, bless their hearts.)

Unlike normal people, I actually really like the score put out by FICO, the firm formerly known as Fair Isaac Company. I like it partly because it’s a score that uses 100% objective historic data.

Specifically – how well have you paid your debts in the past? How much credit are you using today? What indications do we have about your intent to borrow in the future? And that’s it.

Interestingly, FICO does not take into account wealth, income, job status, home ownership status, geography, or marital status, even though we can easily see how all of these factors could make a big difference in whether you’re a safe bet to lend money to.

Trinity University in San Antonio, TX

Trinity University in San Antonio, TXAlso, FICO does not track race, religion, political beliefs or any other modern identity we can come up with. To FICO, we’re all just faceless data streams. That’s a good thing.

While in general we would expect a poorer city to correlate with lower credit scores, it doesn’t have to be that way. We could imagine a concentration of high average credit access even within a lower-income region, due to cultural aversion to debt, or the cultivation of careful use of credit.

And interestingly, high debt balances actually correlate with high incomes. So poor access to credit is a characteristic of poor cities, but maybe ironically high debt usage correlates with richer cities.

From a public policy standpoint, the relative FICO scores of a community matter. If I’m the mayor of Austin versus the mayor of Corpus Christi, I would take this WalletHub data seriously. A whole different set of policy tools might matter to one city versus another.

Aerial view of Boston in Massachusetts, USA at night in winter

Aerial view of Boston in Massachusetts, USA at night in winterA low citywide average credit score means huge numbers of the population are locked out of the affordable mortgage market, which implies the affordable housing market as well. A low citywide average credit score would also make a much higher portion of the population susceptible to high-interest loans and predatory lenders. You can’t stop the credit card companies from signing up customers online and via mail, but policy makers have at times taken steps to limit payday lenders within cities.

Credit access is not yet a typical measure of financial health for city policy makers, although academics and economists are increasingly studying it and using it. Income and wealth differences between cities and within cities are one measure of financial health, while access to credit is another significant measurement which can tell a distinct but complementary story. A 2018 study by the Federal Reserve Bank in Boston contains a few interesting comparisons between cities in Massachusetts.

To give just one example, while we often think of debt as dangerous, in fact higher amounts of debt correlate with much higher-income cities and neighborhoods. In 22 large cities in Massachusetts, the households in the wealthiest city in the study carried the largest average balances of household mortgage debt, as well as credit card debt, and even student loan debt. Lower income and lower wealth cities, by contrast, report much smaller average debt balances. This holds true in comparisons between neighborhoods of Boston as well, with stark differences between rich and poor.

Because access to credit leads to access to home ownership and higher education, access to credit as measured by credit score is a not just a result of income and wealth, but is in fact a predictor of future income and wealth.

One of the ongoing debates in economics is the best way to measure financial health in a local economy. Obviously no one measurement or number tells a complete picture today or the full story of financial or economic progress over time. Access to credit seems to me a major measurement to always include in assessing the financial health of cities.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle earlier this year.

Please see related posts:

Post read (8) times.

The post Credit Score Cities appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

April 30, 2020

Adventures in Auto insurance

I conducted an experiment a few months back to test a long-held theory. The ubiquitous funny advertisements with the green lizard have led me to believe I could save money by calling up my automobile insurance provider and asking them to reduce my costs. (FWIW I don’t use that company. I have a different one, and I’m loyal to mine.)

Long story short, it worked. At the end of my phone conversation with my provider I’ll pay $20.07 less per month. To state some obvious math, that’s $240.84 per year.

I think my choices are prudent for me, but they are not free-lunch choices. I made a series of calculated gambles based on what I know about insurance in general, my particular car, and my personal financial situation.

This all started from a conversation over coffee with a reader two weeks ago. He mentioned that since the 1980s he’d declined to pay for collision insurance on his car, and that he calculates having saved at least $30,000 since then as a result. That got my attention. I realized I haven’t deeply studied the different components of auto insurance. Maybe you haven’t either. Now’s your chance to get a little nerdy with me.

For starters, auto insurance is required by law in every state. The required part of auto insurance is liability insurance. That’s for when you damage someone else’s body, car, or property. In Texas you’re allowed to buy a minimum of $25,000 in coverage per person or car, and $60,000 per incident. I pay to insure well over the minimum amounts and I didn’t mess with this liability part of my auto insurance policy.

The second part of auto insurance – which turns out to be optional in some cases – is collision insurance. That’s the amount you’ll receive if your car gets damaged.

Here’s where insurance theory and two other personal finance theories came into play. I’ll hit you with all three theories. First, insurance is expensive, so buy the least you can while still avoiding catastrophic financial risk. Second, don’t buy too much car. Third, try to buy so little car that you can avoid having a car loan. This third part is admittedly rarely achieved, but something to strive for. Because if you can eliminate your car loan, you have more options with collision insurance.

If you have a car loan, your lender makes you buy collision insurance, naturally, because the car acts as collateral for your loan. A smashed up car makes for poor collateral. If you don’t have a car loan, however, you can decline collision insurance.

I don’t have a car loan. I also don’t have a valuable car. In combination, that means I’m not terribly worried about losing many thousands of dollars in value if I wreck it. During this process I looked up trade-in value for my 11 year-old Hyundai Elantra with 95,000 miles and learned it’s worth $1,800 to $2,500. I don’t expect my insurance company to shower me with much more than that amount, in the event of a total wreck. And I’m not dropping $7,000 in repairs into this automotive beauty in that event either. Both of these factors mean I should keep my collision insurance to a minimum. I declined to pay for any collision insurance this week, because that suits my particular circumstance.

A fourth rule of personal finance came into play on the issue of comprehensive coverage. The rule is that it helps to have money in order to save money.

I saved a small amount when I upped my comprehensive coverage deductible from $500 to $1000. A few definitions might be helpful to explain what this means. Comprehensive coverage protects me if something other than another motorist hits me, such as hail damage, a tree falling, or flooding. The deductible is the amount I’m on the hook for, in the event of needed repairs. My upping the deductible is really a result of being able to handle the financial hit if a bad thing happens. If I didn’t have either savings or decent lines of credit, I wouldn’t be able to responsibly increase my deductible. But I do, so it’s cool. That’s the “it takes money to save money” thing.

A few other fine-print things I considered during my auto insurance conversation.

I continue to pay for vehicle damage if I’m hit by an uninsured motorist, although I lowered my coverage to the Texas state minimum of $25,000. As I mentioned, my car ain’t worth $25,000, so I’m probably over-covered there.

I continue to pay $1.65 per month for towing and labor. Between a history of dead batteries and flat tires, it feels like I need a tow or jump start more than once a year. So I’m getting my full money’s worth there, if history is any guide.

I also learned that our household auto insurance premiums won’t jump in six months when my eldest gets her learner’s permit. But they will jump in 1.5 years – quite a bit – when she gets her full license. I could hear the empathetic pain over the phone in the auto insurer representative’s voice when I told her my daughter’s age.

So that will be a future auto insurance cost increase. In the meantime, I was happy to squeeze out a bit in savings while I could.

A version of this ran in the San Antonio Express-News and Houston Chronicle.

See related posts:

Book Review My Vast Fortune by Andrew Tobias

Buying a Car Part I – Not Getting Fleeced

Post read (3) times.

The post Adventures in Auto insurance appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

April 14, 2020

M1 Finance App Review

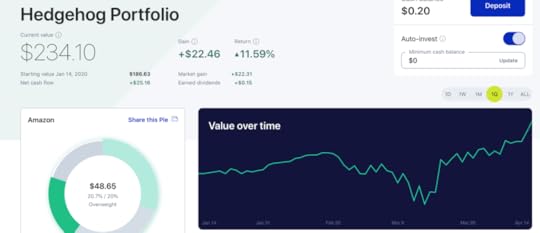

Editor’s Note: This post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle in December 2018, but for some unknown reason I forgot to post it here, back then. Anyway, I needed to post this because I noticed the stocks my younger daughter picked for her account were ridiculously suited for the COVID-19 economy. Surely I could raise $100 million for her hedge fund launch, tentatively titled Hedgehog Capital.

One of the evergreen problems of personal finance is how to entice non-investors – especially the young’uns – to cross over the hump into capitalism, to own some stocks.

In the old days of stock investing – maybe two generations ago – this meant sitting down with Daddy’s highly paid stockbroker in a leather and wood-paneled room, selecting prudent choices from the “Nifty Fifty” list of blue chip companies, and paying him hundreds, or thousands, of dollars every time you traded.

One generation ago, a combination of low-cost trading and online access radically democratized that process, removing almost all the guardrails. My generation learned the joys and pains of picking our own stocks and ETFs, trading as often as we liked from the comfort of our own laptops for a few dollars per trade, or annual fees of less than $100.

M1 Finance Hedgehog portfolio started by my younger daughter. She nailed the “COVID-19 portfolio”: Amazon, Netflix, Walmart, and Google.

M1 Finance Hedgehog portfolio started by my younger daughter. She nailed the “COVID-19 portfolio”: Amazon, Netflix, Walmart, and Google. Around 2010, robo-advising improved upon the old free-wheeling ways, matching an individual’s risk tolerance with low-cost, passive portfolios that required no thinking and reintroduced prudent guardrails without the need for expensive human advisors.

2018 means you can1 use a hybrid robo-investing app like M1 Finance to invest and trade for free, with a starting amount as little as $100, rebalancing your portfolio while zipping down the highway at 65 miles an hour. (Note: This is neither driving nor investing advice. If you do rebalance your portfolio while driving, wear your seatbelt in the backseat of a Lyft or Uber ride.)

In fact, the first time I used the M1 Finance app I was driving down the highway taking my 13 year-old to school, and I told her to build herself a stock portfolio. (She had her seatbelt on, I served as Uber daddy.) She’s my willing guinea pig for new finance apps.

She agreed to fund her portfolio with $100 of her own hard-earned money (Ok, mostly from losing teeth to the tooth fairy, if we’re being honest).

She picked 6 stocks, all household names you’d recognize, plus 3 mutual funds. After linking a bank account for funding the portfolio, the app prompted us to automate additional contributions. We did not, as teeth do not grow on trees and my daughter’s sources of funds are few and far between right now.

Over time, as her assets shift in value, the app can automatically rebalance her original allocation with new contributions, if she makes any.

Things I like about this app:

Extremely low starting funding amounts, as little as $100A very intuitive user-interface on your phone with color-coded “pies” showing your asset allocation. Easy rebalancing to maintain the original allocations over time and with new investments.Fractional share amounts allowed. So if each Apple share cost around $200, you could own one-tenth of an Apple share for $20. This matters for investors just starting out. (FYI, she did not choose Apple.)No fees to invest or tradeHybrid robo-investing. You can take guidance on pre-set “robo-portfolios,” or you can build your own portfolio. Or you can do a hybrid combination. Choose your own adventure.

Two features of the app could be considered, by some, a mixed blessing. The first is that purchases or sales only happen once a day on the M1 Finance platform. With trading and management free, that rule keeps costs low for M1. From my perspective, once-a-day trading is a feature not a bug, since day trading will only make you poorer in the long run. I think you should sell or change asset allocations somewhere between every two decades and never, so I’m not concerned about this limitation. Day trading folks, obviously, will avoid this platform.

Another mixed blessing, ironically coming from me because I’m obsessed with fees, is that M1 Finance is free. Normally low cost is good, and free is the ultimate low cost.

Betterment and Wealthfront, two well-known robo-advisors which I have not used but about which I have a good impression, charge 0.25 percent of assets under management, which is already a rock-bottom price for investment services. Acorns, a robo-advising app I do use and love, also charges 0.25 percent.

Acorns app screens

Acorns app screensBut does no fee investing even make sense? I’m not sure. I’m cautious about free in this case, because of a basic business rule.

That rule is that if you aren’t paying for the product, then you are the product. That’s how Facebook works, obviously. That’s how network television works. The real product of television and Facebook is not our infotainment, but rather delivering our eyeballs to advertisers. Anyway. That’s my worry when I see M1 Finance is free – I assume they are delivering my eyeballs to somebody. And if not now, then possibly in the future.

How does M1 Finance claim they will be making money, if not charging fees?

From online reviews their CEO says M1 will make money from securities lending. That’s something that traditional brokerages do also, without necessarily emphasizing it as an important part of their business model. I’m skeptical this will earn them enough to survive.

Also, the CEO says they may develop other products with fees in the future. I guess that’s the part I’m cautious about, at least for the future. Without knowing exactly how my eyeballs – or my daughter’s eyeballs – will be delivered to advertisers, I don’t know what M1 Finance will ultimately look like.

For now, however, it’s a pretty cool on-ramp to the superhighway of low-cost, low dollar investing.

(By the way if you want to sign up for M1 Finance and get me a referral fee, go ahead and click the M1 Finance referral button here. Why not? It’s $10 for me. Or sign up for the even more totally awesome Acorns app and use my referral button. I think that’s $5 for me. I think you would get a similar matched $10 or $5 incentive. Whatever.)

Please see related posts:

Daughter’s first stock investment

Daughter allowance and compound interest

Never Sell! A Disney and Churchill mashup

My review of the Acorns app, which I totally love (even more than M1 Finance)

Post read (13) times.

I wrote this post in 2018 and I decided not to update this since its an artifact of when I originally wrote this post/column ↩

The post M1 Finance App Review appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

March 31, 2020

Oil and Gas For The Little Guy

Editor’s note: Yeah Yeah Yeah I have the worst timing of all time. Still, the idea that this vehicle exists is important!

One of the regrets of my last ten years as a Northeasterner-turned-Texan is that I’ve only fulfilled some of the stereotypes.

To be fair to me, I’ve accomplished important ones. I wear Lucchese boots. I wear bespoke guayaberas – shout-out Dos Carolinas! I am not yet, however, an investor in oil and gas. I say this with some wistful regret. I want to fit in as a real Texan.

I have recently discovered a possible way to correct this – the subject of the rest of this column – but I should start with a few reasons why I haven’t yet invested in oil and gas. The most obvious reason is that I don’t have enough money to be invited into large-scale opportunities. Next, I have no particular expertise that would assist me in oil and gas investing. Prudence suggests – and I always suggest – doing the simplest, low-cost investing thing that requires the least amount of knowledge.

Oil and gas investments are famously opaque and high-cost opportunities – meaning if you buy into some heavily-promoted deal, it’s hard to avoid just funding a dry hole while paying many layers of fees to the operator or promoter, who makes money whether they are successful or not. The proverbial “heads you win, tails I lose,” kind of situation.

Having laid out some caveats – which hold true no matter what – I am intrigued by a Houston-based online platform called Energy Funders [LINK: https://www.energyfunders.com] designed for the little guy (like me) to invest in oil and gas opportunities.

When you create an investor account on Energy Funders (as I did this month) you can access specific oil and gas exploration opportunities, with a minimum as small as $5,000. Garrett Corley, the VP of investor relations who called to vet me as an investor, says they average about one opportunity per month on their platform, with 34 deals closed to date.

CEO Casey Minshew says over the last five years they have been “Beta Testing” their thesis: That they can disrupt the closed, highly capital-intensive, and high fee world of oil & gas exploration, by giving access to smaller investors while reducing fees.

Minshew shared with me the results so far – involving 34 deals closed to date – as well as the direction he intends Energy Funders to go in the future.

Of 34 deals, 11 have been dry holes. Sixteen have produced appreciable oil and gas to date. Six of the deals, he considers, will be significant wins for investors. I did not independently verify his reported results, but those feel like results one should expect from high-risk investing, and therefore strike me as credible.

Minshew says that for this type of investment, small-dollar participants should split their money between a variety of projects, to lower their risk of failure on any one investment.

Unlike the past five years, however, Minshew explained that the next few years will look a little different in terms of project style. Until now, Energy Funders has mostly backed so-called “wildcat”-style drilling, in which funders inevitably drill dry holes, but hope to have enough big winners to compensate for losses.

Future capital raises on their Energy Funders will focus on lower-risk investing, through two methods. One is to create a portfolio approach to projects, allowing investors access to multiple drilling projects, for diversification purposes.

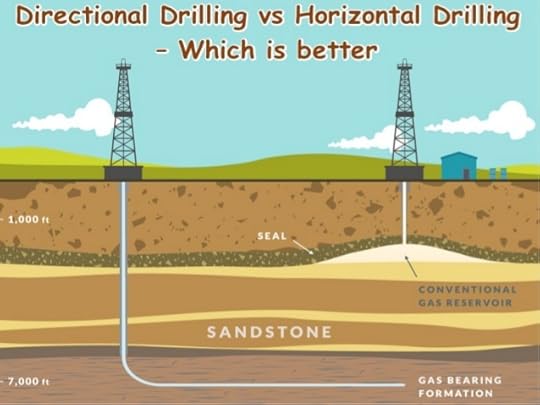

Their second risk-reducing plan is to open up access to “unconventional,” or horizontal drilling projects.

For those familiar with oil and gas extraction lingo, you’ll know what that means. For the rest of us, conventional means drilling a traditional, vertical, hole in the ground.

The way you lose money in conventional is if your vertical hole is dry, with insufficient oil or gas available for extraction.

Unconventional refers to horizontal drilling techniques and deep underground rock-formation smashing, known colloquially as fracking. The way you lose money in unconventional drilling is if the high cost of fracking exceeds the value of the oil and gas extracted – particularly if there’s too much gas and not enough oil. Success or failure is mostly a function of costs rather than dry holes. As an extremely general rule right now, gas is not profitable and oil is profitable, although markets obviously vary and will change in the future.

The project up on the site that I reviewed this week is one of their unconventional offerings, which has already been pumping oil and gas. The structure of that deal, as a result, offers less risk and less reward. But Minshew believes that’s increasingly what investors on their platform want.

I don’t mean to endorse Energy Funders as an investment vehicle in particular because, again, I know nothing about oil and gas investing. But the theory seems plausible to me that a larger market exists for lower-risk, lower-return investments in oil and gas, especially among the smaller-size investors that Energy Funder’s online portal will appeal to.

Since at least 2014, margins in oil and gas exploration have been thin. But like any good entrepreneur, Minshew finds a silver lining in tough market conditions for drillers. As he says,

“It is a capital-starved environment right now. [Oil and gas operators] are now willing to play ball with us. Which is to remove fees and reduce prices.” In addition to drilling risk, fees are largely what has hurt small investors. But Minshew believes “The more and more capital starved the industry, the more valuable we will be.”

In other words, he believes drillers will value the money Energy Funders can raise that much more, and that they can negotiate relatively strong terms for participants. That strikes me as a plausible theory.

I’ve written about and invested in, music royalties in the spirit of democratizing access to previously closed markets.

I’ve also written about, but not invested in, customer loyalty-based funding at Houston-based NextSeed which offers little-guy investing opportunities in startups like bars and restaurants. Energy Funders investments are also a kind of democratizing platform, but from a regulatory standpoint is only offered to accredited investors, who must meet a relatively high income or net worth threshold. While their investment minimums are very small – $5,000 – you do have to have some income or wealth to burn in order to participate.

Final note. I understand that to many readers the idea of investing in oil and gas – in the age of climate change – is akin to investing in cancer. I disagree, but ok.

A version of this ran in the San Antonio Express-News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts

My latest favorite investing idea – Music Royalties!

Crowd-Sourcing Restaurant and Bar businesses (to be posted shortly. SA-EN version here)

Post read (6) times.

The post Oil and Gas For The Little Guy appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

March 29, 2020

Comprehension Not Disclosure

Despite all reports to the contrary, I have not suspended my campaign for National Personal Financial Benevolent Dictator (NPFBD).

In fact, today I add a new plank to my platform.

My latest plank is regulation through comprehension, rather than through disclosure. I’ll unpack what I mean by that below.

I’m in the process of renewing the Home Equity Line of Credit (HELOC) on my house.

As you can imagine, my mailbox and email box filled to the brim with dozens upon dozens of disclosure document pages for my signature. These are virtually unreadable and they will go unread by me. Nevertheless, I will sign them.

Lauren Willis, a law professor whose criticism of financial literacy programs I recently described admiringly, has a replacement for these disclosure documents, and I’ve stolen her idea for my platform.

She argues in a 2017 paper “The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Quest for Consumer Comprehension” that financial products regulation should focus less on disclosure and more on creating a system of consumer comprehension.

Here’s what she means. Financial service providers – of credit cards, insurance, investments, and mortgages – would need to regularly show to regulators that a large majority of their customers could pass a simple comprehension test about their product.

Placing the burden on financial firms to stay consumer compliant is analogous to requiring car companies to prove they can meet emissions standards, or toy manufacturers can meet child safety standards.

As long as, say, 80% of credit cards users could ace a quiz about what their interest rate is and the cost of their late fees, and maybe also what the mandatory arbitration clause means, the credit card company would be in the clear. Or, as long as 70% of insurance buyers could accurately describe the meaning of their deductible, premium, their coverage and exceptions, they are good. Provided that 85% of mortgage borrowers correctly describe in a quiz their terms and what their payments will look like if the adjustable rate changes in 3 years, the product is fine.

I’m making up these numbers and these requirements just to provide some sense of what a consumer-comprehension quiz would look like. The point from Willis is two-fold: Disclosing terms in tiny print over 30 pages never helps. It leaves the burden on the consumer. Instead, the burden should be on the firm to show – with a consumer comprehension audit – that customers know what they are buying. After all, isn’t that the original point of these non-effective disclosures in the first place?

Our default system is free market. And I’m a free markets guy. I like classical economics’ trust that prices and quantities will reach equilibrium as long as we minimize frictions like taxes and government interference. Few people will purchase a $10 tomato when a $1 is available, says classical economics. Firms able to offer $1 tomatoes will sell many more units than a purveyor of Gucci tomatoes. I understand this concept very well.

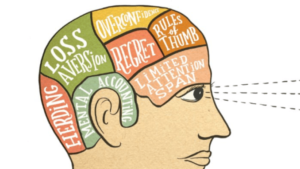

But the last forty years of behavioral finance has taught us that classical equilibrium theory doesn’t work as well in areas like personal finance, because of predictable inherent biases and errors of thought. As a result, people are unknowingly purchasing $10 tomatoes when they should, logically, be buying $1 tomatoes. The inefficiency endures because of human error in predictable, repeatable, ways. And if we know these errors in advance we should build in protections.

And yes, regulation like this could be expensive to firms.

But the alternative is not free market efficiency. The alternative is people paying for $10 tomatoes out of predictable ignorance.

Professor Lauren Willis

Professor Lauren WillisAs NPFBD, I am used to people not understanding the brilliance of my proposals at first glance. But I am both benevolent and a dictator, so I will further explain and address your concerns.

One objection: Some people just can’t be taught, because math is hard. And financial concepts are especially hard. Ok, true. But Willis’ proposal focuses on setting a target for average comprehension. Like maybe just seventy percent of customers have to pass the “comprehension audit.” Not everyone. Just a good majority. That seems reasonable and flexible to me.

Another objection: Comprehension seems costly for firms, as they would be required to create educational programs around their products. Maybe. But wouldn’t it also seem that firms facing the potentially high cost of consumer education would be greatly incentivized to simplify these same financial products? Wouldn’t firms pivot towards selling things that any fifth grader could understand?

I am certain, for example, that variable annuities would rightly disappear from the face of the earth if insurance companies were forced to educate consumers about how they actually work. Because, quite simply, they cannot be explained in simple terms.

You know what else is costly? 25% of sub-prime mortgage borrowers defaulting in the same year, sending the world financial system into a tailspin, and requiring an unlimited bailout of all of Wall Street.

Another objection: True financial complexity cannot be captured in short consumer-education segments. Willis addresses this by analogy with energy-efficiency regulation. Simple labelling with stars currently informs us consumers of energy-efficient dishwashers and refrigerators. I don’t have to be an electrical engineer to understand the energy-efficiency star system. I just need to know enough about how the labelling of stars on my dishwasher works. A simple and consistent labelling system for credit cards, mortgage, and investment products could go a very long way to building consumer comprehension.

This is a results-oriented approach to regulation. It’s not about the number of pages of fine print. It’s about proving – with reasonable room for variation – that people using the products actually know what they’re getting and at what price.

I’m knowledgeable enough about behavioral finance to know that the unfettered free market will lead to worse results for many. But I’m cynical enough to recognize that traditional financial product regulation – in the form of more disclosures – creates an ever-increasing paperwork and liability burden on businesses, but without addressing the core problem.

I don’t read disclosures even on my own HELOC application. In fact, nobody does. This creates a “You pretend to disclose, while I’ll pretend to be protected” universal cynicism toward the regulation of personal financial products.

As your NPFBD, I’ll focus less on disclosure and more on consumer comprehension instead.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related post

My Campaign For NPFBD – Focus on retirement investing

Renewing my HELOC in 2015 – Judgement vs. Objectivity

Post read (5) times.

The post Comprehension Not Disclosure appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

March 25, 2020

Thy Will Be Done – And Do it NOW

Editor’s Note: This post ran as as newspaper column in the beginning of March 2020, before it was clear the imminent threat that COVID-19 posed to everyone’s health. So…this message just got a lot more urgent since the beginning of March.

In December 2017, my friend, who I will call LM, and her sisters visited their elderly father for Christmas. During that visit, he verbally expressed a few wishes to her, just in case something should happen to him.

At the time, he had gone so far as to have a will drawn up, but he had not finalized a plan with his official signature. In addition, he had not authorized anyone with a durable power of attorney, in case of illness.

LM is not sure if he didn’t finalize papers with his signature due to a psychological block around facing his mortality, a mistaken idea for saving money, or hesitation around who should use his apartment if he died. All she knows is that he’d done 99% of the process, but didn’t complete it.

A week later, in January 2018, he fell ill and was hospitalized. Then, family hell broke loose. The story is a bit complicated, as these stories always are. As Tolstoy wrote in the beginning of Anna Karenina, “every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Like other 19th Century novels, LM’s story stems from contested estates, suspicion between family members, and expensive legal processes.

[image error]

LM’s father’s girlfriend became verbally abusive. LM’s aunts – LM’s father’s sisters – were suing LM’s father, in the mistaken belief that LM’s father – as trustee of their father’s trust – was collecting more than his fair share, while their father LM’s grandfather was still alive.

Meanwhile, paying for her father’s care during a 2-months’ long hospitalization became complicated. Without a written and signed power of attorney, and in the face of a draining lawsuit and logistical difficulty even making health care decisions, LM and her family had to declare a “conservatorship” for her father’s assets. Her father died at the end of February 2018 without a will, and with his estate under legal attack from his own sisters.

Tanya Feinleib, an attorney and shareholder at Langley & Banack in San Antonio, board certified in estate planning and probate law, says this type of “conservatorship” or “guardianship” can be an expensive and cumbersome court-supervised process.

LM describes three kinds of costs to not having a will and power and attorney at the time of her father’s death. The first is in time.

LM’s father died in late February 2018, two full years ago. She and her two sisters have only just this past month settled the probate case, and settled a lawsuit with her aunts. Two years is a long time to remain suspended in an uncomfortable legal process with family members, made worse by the mixture of mourning, family strife, and uncertainty.

The second cost is the most obvious one, dollars drained from her father’s estate. LM calculated that her father’s estate paid 13 times more than necessary, for lack of a power of attorney. She calculates that her father’s estate paid 3 times more than necessary for lack of a will. When she includes the costs of settling the lawsuit with her aunts, more than 30% of her father’s estate was lost due to a combination of unclear communication and unfinished estate planning. Over half a million dollars remained suspended in probate, and then drained by a third, over two years.

But the third cost, LM says, was the worst.

LM told me, “What’s even more tragic are the physical, psychological and spiritual costs of siblings who used to love each other growing to hate each other. All of that stress physically manifests in them. The worst cost imaginable to me, would be to be so insanely angry with a sibling that you couldn’t find it in you to forgive them, to say good-bye to them on their deathbed or even attend their funeral. That still makes me cry when I think about it.”

A 2016 Gallup poll found that just 44 percent of American adults have a will Of course this number varies by age, with only 14 percent of those aged 18-29 having a will (Millennials, amirite?), and 68 percent of folks over age 65 with a will. (Ok, Boomer) I’m now talking to the 32 percent of you without a will. What are you thinking? Do it. Do it now.

You should expect the cost – for a family without complicated trusts or an ultra-high net worth – to range between $1,000 and $2,500 to prepare a will and power of attorney documents. Expect on the low end for single people without dependents. Higher for more complex families and estate requirements. Feinleib says that there are legal aid providers in many cities, including Houston and San Antonio, that offer free wills and powers of attorney for people who qualify. Some employers offer an employee assistance program for free or subsidized time with an attorney, which could be used to get your will done.

It may be tempting to try to save money without an attorney. Feinleib says web-based or artificial intelligence will-preparation could happen in our lifetime, but don’t rely on that yet.

“For now, with respect to handwritten wills and off-the-internet wills” Feinleib warns, “When they go wrong, they tend to be extremely expensive on the probate side.”

My friend LM’s main reason for speaking with me about the details was to encourage other people to get this done right away. To not let her family’s heartache happen to other families.

Feinleib says “I think it’s the most loving thing you can do for your family. Your incapacity is going to be one of the worst moments of their life.” By properly preparing for that time, she says, you give your family a great gift.

The costs and some of the heartaches endured by LM and her family were avoidable. Says Feinleib, “every person needs to have a plan in place for who will make decisions regarding health care if they become incapacitated.”

Would you like to know the worst, ironic part of this? Even two years following her father’s death, even after years of expensive litigation, LM’s own mother has still not prepared her own will. LM herself is a certified financial planner, and one of her sisters is an attorney. And they still can’t convince their own mother to prepare her will. After the last two years of probate hell and family struggle, LM was in a state of near-disbelief when she told me this, caught somewhere between shock and bursting into tears.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express-News and Houston Chronicle.

Post read (5) times.

The post Thy Will Be Done – And Do it NOW appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.