Michael C. Taylor's Blog, page 13

December 27, 2019

Weird Finances Of Trump Campaign Manager’s Company

Editor’s Note: This post ran as a newspaper column in November 2019. Parscale resigned from the board of the company on December 10th, according to a public company notice. I did an interview with Texas Public Radio about that development here.

The head of President Trump’s re-election campaign, Brad Parscale, serves on the board of – and owns rights to acquire a majority stake in – an odd penny stock company headquartered in San Antonio called Cloud Commerce. The company publicly filed its intention on October 31, 2019 to raise up to $20 million through issuing preferred stock.

It’s clear from public company filings that Cloud Commerce needs this money. The firm has consistently lost money every single year since at least 2012, when current management took over. It’s less clear why anyone would give them money.

Cloud Commerce Logo

Cloud Commerce LogoTo state the obvious, successful companies fund themselves through ordinary revenues and, hopefully, profits. But it’s hard to maintain a company like Cloud Commerce afloat when it loses money year after year. You have to resort to either borrowing money or issuing new shares. Cloud Commerce has gotten into a weird financing habit of doing both.

“Substantial Doubt” and “Going Concern” language

The company’s disclosures, in dry auditor-speak, use boiler-plate language which reflects the financial reality of Cloud Commerce.

In a recent quarterly filing dated November 14, 2019, the firm wrote

“The Company does not generate significant revenue, and has negative cash flows from operations, which raise substantial doubt about the Company’s ability to continue as a going concern.”

The company’s annual report filed April 15, 2019, states “We have experienced net losses and negative cash flows from operating activities, and we expect such losses and negative cash flows to continue in the foreseeable future.”

This doubt about the company’s continuation “as a going concern” due to lack of revenue and losses each year is repeated in year-end filings every year going back to 2012, when the current management team took over.

The company had net losses and negative cash flows and substantial doubt about its ability to continue as a going concern in 2017 when it purchased Parscale’s business, which raises the question of what advantage Parscale saw in the sale.

Parscale received rights to obtain a majority of the shares in the company when he and his San Antonio-based partner sold their web and design company to Cloud Commerce in August 2017.

Financing Through Convertible Debt

Before that, beginning in January 2016 and continuing right up until the week Cloud Commerce acquired Parscale’s business in July 2017, a primary source of working capital for the company appears to be loans from the company’s CFO, Greg Boden. Throughout 2016 Boden issued a series of loans worth a total of $1.1 million from an investment company he owns named Bountiful Capital LLC, to Cloud Commerce.

Between May and July 2017, Boden made seven more smaller loans to Cloud Commerce, in amounts ranging from $26,000 to $105,000.

All of that debt soon became a different financial instrument.

On the same day as the acquisition of Parscale’s company, Boden turned his total of $1.4425 million in loans into preferred shares that give him the right to convert into 144,250,000 common shares of Cloud Commerce.

If fully converted into common stock, the total amount of 144 million shares would exceed the amount of common shares outstanding in the company, currently 137 million. Conversion would make Boden the majority shareholder in the company.

Meanwhile, Parscale’s deal gave him the rights to own 225 million shares in Cloud Commerce. Those rights would make him the majority owner, if he chose.

Prior to that, an earlier transaction gave a different ownership group preferred shares with rights to own 450 million shares.

Are you confused yet? It appears three different groups have to right to exercise an option to own a majority of Cloud Commerce.

In 2019, in the absence of sufficient revenue and profit, Cloud Commerce has continued to fund itself through convertible debt.

Seven times between January and July 2019, the company borrowed money at 10% annual interest, with the lender’s option to purchase new shares at a 39% discount to average market prices, six months later. So if the stock traded at an average of 0.01, the lender could convert the debt into shares at $0.0069. As of this writing, the company borrowed $397,000 this way in 2019. Public filings do not name the lender on the convertible notes between January and July 2019.

If you squint your eyes a bit, these convertible notes represent a kind of financial magic for the lender. The game here is that the lender gets to convert the loan into common shares at a deep discount to the stock’s market price.

When you can buy something seemingly worth a dollar for just 69 cents, then in the finance world you want to do that type of transaction all day long.

But to be clear, this is not a normal public company transaction.

Normal public companies sometimes do issue new shares at a slight discount to current market prices, such as 5%, to preferred investors, for strategic reasons. Normal companies do not, however, issue shares at a 39% discount to market prices.

From the perspective of a normal existing shareholder in a public company, a company issuing shares at a 39% discount to market value would be bizarre and wealth-destroying. If Cloud Commerce had any meaningful outside shareholders, they would howl at the unfairness of new share issuance at a 39% discount.

This in itself is not illegal. But it is bizarre.

Of course, it would be extremely difficult to ‘cash out’ Cloud Commerce shares at $0.01, to earn that theoretical free money profit, when there aren’t any noticeable willing outside buyers. Daily volume in this stock does not usually exceed $750.

For insiders to profit, most penny stock schemes like this depend on a pump-and-dump mechanism. You know, issue a series of positive press releases to pump up hope among unsophisticated buyers who jump on board. These new buyers prop up the price long enough for insiders to dump their shares at a profit.

Who’s Zooming Who?

This brings us back to the great mystery of Cloud Commerce, and Trump campaign manager Brad Parscale’s willingness to get involved with them. What is the game here? As the late great Aretha Franklin once asked, “Who’s Zooming Who?”

Who’s Zoomin’ Who?

Who’s Zoomin’ Who?If the general rule of strange penny stock companies like Cloud Commerce is that they are hotbeds of market manipulation and pump-and-dump schemes, we would kind of expect that the insiders would be looking to take advantage of outsiders. Issuing rights to create nearly a billion shares at around 0.01 over the past few years to insiders mostly just shuffles around who owns the company amongst the insiders.

Actually making money from share ownership would require outsiders to become interested in buying these shares. Whether for $0.01, or at whatever price. Failing that, you could try another scheme.

You could try for example to raise $20 million from credulous buyers, so that owning a majority of a $20 million shell company would actually be worth something.

From everything I’ve seen, President Trump’s campaign manager Brad Parscale hopes to profit from questionable tactics in order to fool a gullible public with the flim-flam illusion of a successful businessman and a profitable business.

In a related story, he’s also involved with a company called Cloud Commerce.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related post:

Potemkin-finances of Trump Campaign Manager company

Recording My Thoughts on Trump, in Fall 2019

Post read (8) times.

The post Weird Finances Of Trump Campaign Manager’s Company appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

December 26, 2019

The Penny Stock Campaign Manager

Editor’s NOTE: This ran in the newspaper in November. Just found out Parscale resigned from the board of the company in Mid-December.

The highest-profile tech entrepreneur to emerge from San Antonio over the past decade is Brad Parscale. His career rocketed upward over the last four years, from designing a $1,500 Trump campaign website in 2015, to digital director and largest-billing vender to the successful “Project Alamo” in support of the 2016 Donald Trump Presidential campaign, to his current appointment, beginning in February 2018, as campaign manager for Trump’s 2020.

Parscale

ParscaleAlthough he lives in Florida now, Parscale continues to have ongoing deep ties to an obscure but publicly traded web, design and data-based business in San Antonio. This business, under the umbrella Cloud Commerce (ticker CLWD) is one of the mysteries of the Brad Parscale story. Parscale currently serves on the Board of Directors of CLWD.

The mystery began with the announcement, August 1, 2017, of the sale of Parscale’s web design business to Cloud Commerce, for a reported $10 million. That transaction never make sense, from a straightforward financial perspective, more than two years ago.

Cloud Commerce has never traded on a major exchange and it has long existed in a different, murkier, world from regular stocks. With 137.5 million shares outstanding, “trading” at a price between 0.0027 and 0.02 in the past year, the value of the company could be mathematically described as between $370 thousand and 2.7 million. In the week before Parscale sold his company in 2017, all shares in CLWD were “traded” at $0.01, for a total company “worth” of $1.37 million.

But trading volume on the shares typically reaches to less than $1,000 per day, which means that a true market value of the company is nearly impossible to determine.

On Penny Stocks

It’s worth considering the strange world of penny stocks it comes from.

A “penny stock” is any publicly owned company whose shares trade below $5 a share. Any stock trading below $2 in the case of the Nasdaq – or $1 in the case of the New York Stock Exchange – risks losing their listing on a major stock exchange. But CLWD shares have long traded at one one-hundredth of the penny stock threshold and has never come close to being eligible for listing on an exchange.

The Potempkin-Village approach to public company ownership

The Potempkin-Village approach to public company ownershipCloud Commerce has lost money every year since current management took over in 2012. Losses totaled less than $1 million in 2012, 2013 and 2014, but have since accelerated to at least $2 million per year, and an average of over $4 million, since 2016. Having lost money every year, the company has never paid federal taxes.

Penny stocks like this don’t really make sense as investments but are often vehicles for “pump-and-dump” schemes, in which operators hype thinly-traded shares to attract buyers, and then sell shares at the inflated prices.

Robert R. Johnson, Professor of Finance, Heider College of Business, Creighton University points out, “for the vast majority of investors, investing in penny stocks is wholly unsuitable. Penny stocks are the Wild West of the financial landscape. Investors should simply expect to lose their investment in penny stocks. There is an immense amount of fraud in the penny stock world.”

The Cloud Commerce story does not seem to be an exception to this rule of penny stocks. it’s a loss-making firm with strange financial arrangements. As Jacob Frenkel, former SEC regulator said in an Associated Press story regarding Cloud Commerce: “What about this company isn’t a red flag?”

Financing The Sale, Without Any Money

The strangeness of Parscale’s sale to a penny stock company began with the announcement that Parscale and his San Antonio-based partner Jill Giles had sold their business for $10 million to Cloud Commerce.

Strange, because the value of the acquiring company Cloud Commerce at the time, as measured by “market capitalization,” was less $1.5 million.

So how could Cloud Commerce pay $10 million when they lose money every year and were only supposedly worth $1.5 million?

The quick answer: It didn’t pay $10 million.

Instead, the purchase was structured in the following way.

Public filings describe Parscale received 90,000 “Series D Preferred shares,” each convertible into 2,500 common shares in Cloud Commerce. The 90,000 Preferred shares granted Parscale the right convert into 225 million common shares of Cloud Commerce. In other words, more shares than were currently outstanding in the company. If he converted his preferred shares and other executives did not, he would become the majority shareholder in the company, with 225 million shares. Parscale was locked up for two years from selling, or in other words until August 2019.

Parscale seems to have been excited about the possibilities of owning shares in his penny stock firm in the days following the sale, with a tweet on August 8, 2017 touting the stock’s rise from 0.01 to 0.05. He tweeted “Big week for the parent company of my commercial business @CloudCommerceco. Stock up 500%”

Big week for the parent company of my commercial business @cloudcommerceco. Stock up 500%. https://t.co/u1Pbfi0HmO

— Brad Parscale – Text TRUMP to 88022 (@parscale) August 8, 2017

In the announcement of the sale to Cloud Commerce, these 90,000 “Series D Preferreds” were declared to be worth $9 million.

How? Just because. It’s as real as if I wrote down the number $9 million on a piece of paper, then handed it to you. “Here,” I’d say conspiratorially, sliding it across the table, “I’m giving you $9 million. Trust me. See? It says $9 million right here on the paper.”

It is true that had the shares remained at $0.04 or above, Parscale could have, sort of, claimed his stake was theoretically worth $9 million, two years hence. For the past year the shares have rarely broken 0.02 and are today “worth” one-tenth of even that amount.

The $10 million announcement in August 2017 also mentioned an extra payment of $1 million in cash to be paid to Parscale. Except that CloudCommerce doesn’t have that kind of money.

So, six months later, when it still had not paid Parscale any cash, it began to make arrangements. According to a February 2018 8K filing, the company made an agreement with Parscale to pay $1 million in the form of a promissory note, an IOU, in monthly installments of $85,149.90.

Interestingly, we know from later filings that Cloud Commerce also did not pay that note in a cash to Parscale. Instead, it produced an invoice in November 2018 detailing 68 separate services Cloud Commerce performed for Parscale Strategy – his separate political business based in Florida – through 2018. Those services netted out money owed to Parscale for the purchase.

In the first week of the sale – when Parscale tweeted about the 500% rise in shares, I could understand the sale as just another pump-and-dump scheme, typical of this style of penny stock. It has not made any sense since.

Recently, however, Cloud Commerce announced a new plan to fund itself. I’ll explain in a future post.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related post:

The weird finances of Cloud Commerce (to be posted shortly)

Post read (20) times.

The post The Penny Stock Campaign Manager appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

December 15, 2019

Book Review: Scarcity by Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir

When we talk about making good financial decisions over a lifetime, we often assume they flow from a combination of willpower and knowledge. Essentially, as long as our brain is screwed on tightly, we can do this. Good decisions follow.

One of the most intriguing branches of behavioral finance – described in the 2013 book Scarcity: The New Science of Having Less And How It Defines our Lives by Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir – suggests that our brains face an unfair fight under certain conditions. Specifically, the lack of something – scarcity – makes us unable – cognitively – to make the right decisions to overcome our lack in the long run.

The authors study more than just financial scarcity: Starvation, busyness, and loneliness are all experiences of scarcity of important resources – food, time, or personal connection.

The first effect of scarcity, they argue, can actually be positive. Scarcity focuses the mind. Newspaper writers know the value of a tight deadline for completing work. Low-income contestants on The Price is Right gameshow have a huge advantage over wealthy people who haven’t ever needed to focus on such forgettable matters as the exact retail price of Gold Bond Medicated Powder. The last stick of gum in the pack sure seems unusually delicious and valuable to my kids, who never, ever, share it with Daddy.

But that increased mental focus or heightened value for a scarce resource comes at a mental cost. By tunneling our vision on some things, we lose the ability to deal rationally with others.

In study after study, the authors show, we all tend to exhibit this behavior. In the realm of finance, researchers simulate poverty or abundance and find that our brains become either impaired or sharpened – for better and worse – in both instantaneous and long-lasting ways.

The effect works the same on the rich and the poor. Meaning, our brains react automatically to conditions of scarcity – even if it is artificially-induced scarcity – in a lab. We all perform worse on IQ-type tests when made to feel poor. We all seek to squander resources, or hoard resources, in predictable ways when faced with abundance or scarcity.

One mechanism by which scarcity leads to a cycle of poverty looks like this. A lack of money increases our mental focus on immediate savings or cashflow, but greatly reduces our ability to think outside of the immediate need. Good personal finance choices, unfortunately, often require us to rationally decide between complex choices with effects that will play out over months, years, and decades.

What does that cause? It means someone becomes less able to plan for one month from now (savings) or 25 years from now (retirement investing) or for an unexpected and costly illness (health-insurance). The same mind-focus on stretching a few dollars effectively from today to tomorrow will prevent our brains from seeing outside of our immediate challenge.

The authors point out that sometimes what looks like poor financial choices from the outside is actually both highly rational for someone maximizing scarce resources, as well as an unconscious response by our brains under conditions of scarcity.

Throughout the book I found myself reflecting on all the ways big and small, short and long, I’ve felt these effects. A multi-hour calorie-deficit at 7pm makes for a different type of thought-process for me.1 The unpleasant brain fuzziness after learning about a larger-than-anticipated tax bill. Attention-deficit when receiving pleasant, or unpleasant, texts on my phone while hurtling down the highway in my car at 70 miles-per-hour. A kind of perseverative neediness can take over my brain when I’m lonely.2

Of course, poverty is not the only thing weighing on a poor person’s mind. Culture, past-experiences, and individual personalities could all play even larger roles in what happens to someone in poverty. Scarcity of money is only one of many factors.

But, the authors argue, scarcity tends to affect our minds in a way that reinforces poverty.

As Americans we enjoy the myth that if we all just could yank aggressively on our bootstraps, we will rise above our inherited place in society.

Understanding the scarcity mindset, however, tends to undermine this myth. It is literally harder for a brain in poverty to focus on the steps necessary to cure the poverty. Our brain becomes our own enemy in this aggressive bootstrap-yanking project.

It’s not hard to extend the logic of these economists’ book to contemporary policies.

Andrew Yang’s quixotic campaign for the Democratic Presidential nomination has only about 4 minutes left to it, but he has brought one lasting policy idea to the fore of American politics: Universal Basic Income, as either a supplement or as a replacement for existing welfare policies. It’s an idea I personally think should be more seriously debated, and deserves as much attention from the traditional Right as it does from the traditional Left of the political divide.

Maybe, the logic goes, if we reduced the tunnel-vision of poverty through a small basic income, recipients could focus on longer-term steps, like job-training or eliminating their pay-day loan debts.

In the light of the Scarcity book, a move in the beginning of December by the federal government to restrict access to food stamps with a more restrictive work requirement doesn’t seem to take into account the work of Mullainathan and Shafir.

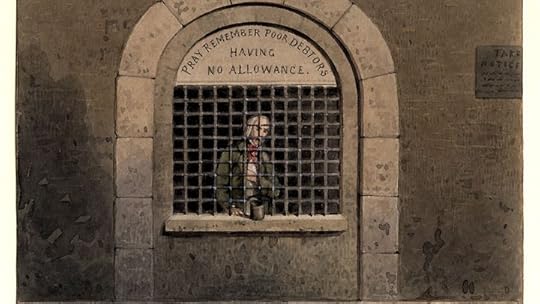

Restricting food stamps uses the same kind of logic as the old 19th Century debtors’ prisons

Restricting food stamps uses the same kind of logic as the old 19th Century debtors’ prisonsCompounding the scarcity of poverty with additional food scarcity seems not just cruel but ignorant of brain science. It’s a kind of 19th Century mindset reminiscent of debtors’ prisons. I think Mullainathan and Shafir would ask us to understand the effect of this type of thing on our brains better, if the goal is to break the cycle of poverty.

Behavioral finance research like in this book continues to take us down roads into the complexity of the human mind. We need continuous reminders of how un-simple the issues really are.

[image error]

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts

Universal Basic Income – That Right Wing Idea

Cash Rather Than Good Intentions

Post read (4) times.

Watch out kids, Daddy has the personality of a grizzy bear until dinner is served. ↩ Luckily, I married a saint. ↩

The post Book Review: Scarcity by Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

November 20, 2019

FIRE Part III – The Role of Frugality

I’ve recently written about the Millennial trend known as FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early), in which people in their 20s and 30s strategize and save and aspire to be able to retire from work very early in their life. While complex planning is interesting one thread links the people I know who successfully retired early: They are super frugal.

Elizabeth

My friend Elizabeth Morse lives in rural New Mexico. Now 48, she retired at age 42. She had previously earned close to $40,000 per year through work, mostly at a private school. Her income spiked to approximately $80,000 for just four years prior to retirement when she worked in the development office of her school. She was pleasantly surprised to be earning that much in those years, but soon realized – by around age 38 – that she could retire very early. She didn’t do any fancy math or tax-savings tricks to plan her FIRE.

Instead, she realized she and her husband Alan could live on around $42,000 per year. Between his pension and their joint savings, they have that covered.

I asked Elizabth about her keys to retiring early.

Elizabeth and her husband, a retired math teacher, previously lived in the faculty housing of their private school, taking financial advantage of that, plus free cafeteria food. Living that way, they saved 25% of their pay every year.

“If I’d had kids or divorced, I wouldn’t be able to do it,” she acknowledged.

Her hobbies come straight out of the 19th Century. They frequently walk in the national forest land that abuts their property. She reads constantly. She knits constantly. She makes her own yarn for knitting, with a spinner. In fact I learned from Elizabeth the origin of the word “spinster.” (Look it up!) As she says, “If your hobbies are free, the money just accumulates.”

If you make your own yarn, you may be a spinster

If you make your own yarn, you may be a spinsterThey are too far a drive from the nearest town to buy coffee from somewhere else, or to go out to eat much. She bakes her own bread and almost always cooks at home. She recently bought a half-cow and a whole lamb from a nearby ranch, from which they’ll derive 2 years’ worth of meat. By her estimation they will pay $1.12 per pound of grass-fed meat for that privilege. She adds that this quickly justifies the cost of their chest freezer.

Her husband’s tastes and hobbies are similarly modest. Although he loves stamp collecting, he recently scratched that itch by organizing and disposing of someone else’s extensive stamp collection. Which, as Elizabeth explained, provided all of the fun with none of the expense! Philately, I gather, may be pursued either expensively or frugally.

Philately may be pursued frugally or expensively

Philately may be pursued frugally or expensivelyElizabeth wasn’t always this way. “I grew up as an American in the 1980s, where going to the mall and shopping is recreation.” But as her twenties became her thirties and forties, she figured out what she really liked doing with her time. Which turned out to be shockingly free or frugal. And although she jokes that her non-participation in consumerism is ‘counter-cultural,’ she also sees it as a key to her early retirement.

“Everybody who wants financial independence has to be somewhat counter-cultural. We live in a culture that pushes instant gratification.”

As old-school as this life seems, they aren’t shut off from the world. She’s on Facebook. She and her husband listen to radio and podcasts. Their internet plan at home doesn’t have enough bandwidth to stream video, so they still do the old-school Netflix CDs through the mail. (I thought Netflix CDs through the mail ended in in the 1950s, but that just shows what I know.)

Gerald

Gerald Van Den Dries, now 59 and living near Lake Medina, Texas, retired at age 53 from teaching at public school.

In his highest earning years as a teacher he made less than $55,000 per year. He lives partly from his Texas teachers retirement pension, partly from investments, and partly from part-time work that he and his wife still do – work they do more for stimulation than for the money. Gerald emphasized to me, however, that he and his wife never let their part-time work get in the way of their extensive travel schedule.

Gerald and his family were featured in a newspaper article in 2005 about how frugal they are. This isn’t his first frugality rodeo.

Now in retirement, it’s not that Gerald avoids spending money on meals out, or on travel. On the contrary, he provided to me extensive details of his planning a 66-day trip to Asia. He says he and his wife travel so much they are running out of places to go on vacation. They’ll go out to a steak dinner, if he can get a 30% discount. But if there’s no discount, there’s no eating out.

Gerald takes the cruise ship in the ‘repositioning leg’ of the journey to save money

Gerald takes the cruise ship in the ‘repositioning leg’ of the journey to save moneyJust as exciting as the trips and the steak, it seems, are the cheap deals he gets.

They travel off season, picking up flights, hotel, and cruise-ship rides at crazy-bargains. A big part of the joy of travel for Gerald is in the steal he gets by using websites like groupon.com for travel, golfnow.com for recreation, and mindmyhouse.com to save on hotels.

Frugality, for Gerald, is not a cold, joyless existence. It’s a game that he relishes and maximizes. Some people write symphonies. Gerald is the Mozart of saving his money.

Elizabeth’s expressed her counter-cultural philosophy as the commonest of common sense: “The important thing for me is framing my world so that my wants and my needs are not that far apart”

Speaking to Elizabeth and Gerald. the FIRE thing seems to work for a lot longer and a lot more consistently if frugality is not a struggle, but rather an expression of who you are in the world.

As I write this, I see from Facebook that Elizabeth and her husband are in Paris, on a houseboat on the Seine River. Gerald and his wife’s trip to Asia will happen in February.

Their day-to-day frugality and early retirement has led to some pretty big perks.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express-News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts

FIRE Part II – Doing it The Complex Way

Post read (1) times.

The post FIRE Part III – The Role of Frugality appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

November 11, 2019

FIRE Part II – Complex Strategies

I’m not saying you should do this. In fact, very probably, don’t do this. In discussing early retirement plans with my buddy Justin recently, however, I learned for the first time about penalty-free ways of accessing retirement accounts early. This post is in the spirit of learning about obscure financial planning tips relevant to one in a thousand people.1

One hitch for young folks attempting FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early) is that traditional 401(k) accounts do not let you withdraw retirement savings, without a 10% penalty, before age 59.5. If you diligently socked away money into a plump nest egg in a tax-advantaged account in your 20s, 30s, and 40s, how would you access this money for your early retirement?

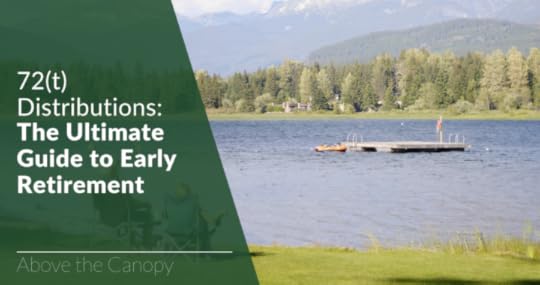

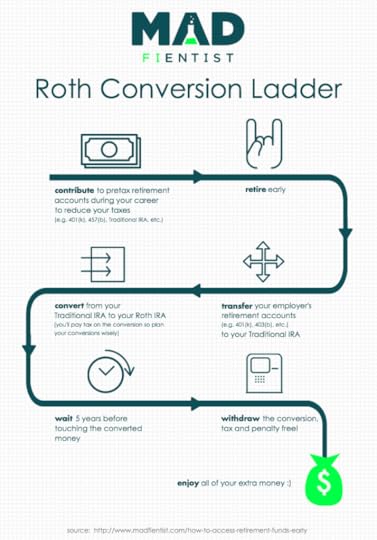

Justin mentioned two techniques known to FIRE Movement adherents for accessing retirement account funds early, without penalty. One is known as the “72(t) exception.” The other is “building a 5-year Roth conversion ladder.” I’ll take them one at a time.

The 72(t) exemption allows a person under 59.5 (the ordinary non-penalty retirement age) to lock in a fixed annual withdrawal amount from their retirement accounts, as long as that amount continues without fail until age 59.5, and also for at least five years. The amount withdrawn may be determined by an IRS table of ‘expected remaining life.’ That’s the same table that gets used for typical ‘required minimum distributions’ from retirement accounts after age 70.5. Or it could be determined by two other allowable methods that fix an annual withdrawal rate, based on either ‘annuitizing’ or ‘amortizing’ your account balances in an even, formulaic way. You can find calculators online that will let you compare withdrawal amounts between all three methods.

The bummer of this technique is that it’s entirely inflexible. Once you start retirement account withdrawals under the 72(t) exemption, you may not stop until age 59.5, even if your life circumstances change. In addition, any account that goes into 72(t)-mode cannot be contributed to anymore. It’s locked. And your withdrawal amounts are locked in.

Ben Gurwitz, Certified Financial Planner and Principal of San Antonio-based Financial Life Advisors, a fee-only financial planning firm, likens the 72(t) choice to “a straightjacket.” He also says that both in his previous work with a CPA firm and in his current work, reviewing hundreds of clients’ finances, he has never once had a client choose the 72(t) option. Probably because it’s weirdly inflexible. As he says, “Once you turn this thing on, you can’t turn it off.” If you decide not to retire, or you realize you need more (or less) income in retirement, you can’t really shift the 72(t) withdrawals in mid-plan.

The second FIRE technique for accessing retirement account money early – The “5-year Roth conversion ladder” – is a lot more reasonable, and a lot more flexible.

As a reminder, Roth retirement account contributions are taxed upfront, but allow for tax-free withdrawals in retirement.

The Mad Fientist has a ton of FIRE strategies explained in plain language. If you’re into it, you probably already know about the Mad Fientist.

The Mad Fientist has a ton of FIRE strategies explained in plain language. If you’re into it, you probably already know about the Mad Fientist.Because Roth money has been taxed once as income already, the rules are a bit more relaxed for how and when withdrawals can be made.

One semi-relaxed rule is that 5 years after converting funds from a traditional 401(k) to a Roth account, the Roth funds may be withdrawn penalty-free, even before age 59.5. You are required to pay taxes on 401(k) funds to make the conversion, but then the Roth money is available tax-free in the future. And because of larger annual contribution limits, it’s easier and more plausible to build up a sizeable nest egg in a 401(k) than in a Roth IRA.

Maybe an example would help. You’re 45 years old. You plan to retire at age 50. And you need to use the funds in your $250,000 401(k) to supplement your lifestyle costs, at least until you qualify, let’s say, for a combination of Social Security and a pension at age 59.5.

You begin to construct your “Roth conversion ladder” by converting $25,000 of your traditional 401(k) into a Roth IRA at age 45. You owe some income taxes on that conversion. You continue to do this conversion of $25,000 per year, every year, over the next 10 years, until the original traditional 401(k) is depleted. The goal is that by the time you hit age 50 – early retirement age – you can withdraw $25,000 from the Roth account without incurring any early-retirement penalty. By converting $25,000 each year starting at age 45, you should have $25,000 (or more, after investment gains) available to you as tax-free income each year beginning at age 50.

As long as your conversion was done at least 5 years prior, you can withdraw Roth converted amounts tax free and penalty free. That’s the basis for the “5-year Roth conversion ladder” strategy for early retirement folks.

Gurwitz concurs this is a more flexible approach to early-retirement planning, and a technique that in no way restricts future income or decisions. If one decides to not retire at age 50, besides having paid taxes, there’s no particular downside to having converted traditional 401(k) retirement funds into a Roth.

Gurwitz agrees with me, however, that the concept of FIRE itself may be the problem, in so far as people are eager to quit work. The “work is just a means to an end,” approach maybe misses the bigger picture about the value of work in our lives, he says. “They [FIRE adherents] are shooting at the wrong thing.”

Another problem he sees, partially reflecting what he does for a living, is people trying to do this entirely on their own. Planning for retirement, and especially early retirement, can be complicated. But the kind of person who passionately reads FIRE blogs is also precisely the kind of person uninterested in paying a financial planner.

So they probably wouldn’t walk in the door to ask for advice about the 72(t) or a “5-year Roth conversion ladder” in the first place. Gurwitz cautions against that do-it-yourself approach.

Says Gurwitz, “I would encourage people to seek the advice of a professional. If they can’t afford to see a professional, they probably can’t afford to be financially independent and retire early.”

I’m a do-it-yourselfer when it comes to my own personal finances. But I think I’m in Gurwitz’s camp when it comes to next-level FIRE strategies, which are kind of complex.

So, as Smokey the Bear might say, don’t play with matches kids, and seek professional help before you start your FIRE.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts:

FIRE Part I – Taxonomy of the Different Retirement Styles of the Young and Independent

FIRE Part III – On the Importance of Being Frugal

Post read (14) times.

“Per usual,” you mutter under your breath. Hey now! I heard that! ↩

The post FIRE Part II – Complex Strategies appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

October 30, 2019

Transparency Part III – Salaries! All We Have To Lose Is Our Chains!

Ready for another crazy, but great, money idea that could

change your life for the better?

Salary transparency. At your workplace. Meaning: everyone

knows what everyone else gets paid, every year. No, wait, stick with me here. I

know you suddenly felt a little ill. But salary transparency works to your

advantage.

Salary transparency is an idea most commonly discussed as an

ideal in recent years among Silicon Valley tech companies, but it shouldn’t

begin or end there.

San Antonio-based software engineer Nancy Hawa of DevResults a data-organization and data-visualization company based in Washington DC, pushed for salary transparency in her 12-person company earlier this year. DevResults decided to take the plunge.

As a result, her CEO and COO released to employees a

completely open set of data around not only what all employees make this year,

but the entire history of everyone’s compensation.

The initial feeling among Hawa and her colleagues with that

disclosure, she admits, was dismay. She described the higher-paid employees in

the office holding their heads at their desks in a kind of awkward embarrassment.

Lower-paid employees, like Hawa, held their breath to find out what would

happen next.

To the credit of DevResults’ leadership, they announced that

despite what appeared to be “unfair pay” then, nobody would be paid less as a

result. Over time, Hawa reports, lower-paid employees received a bump up in pay

to put them in line with their colleagues. Transparency for Hawa meant she will

be paid a lot more, not only this year, but in the future.

I learned from my conversation with Hawa a bunch of the nuances around salary transparency, a topic about which she is passionate.

The first nuance is about the “Why?” of salary disclosure.

The two best reasons to want financial transparency are to

fight corruption and to ensure fairness.

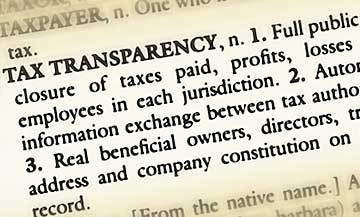

I wrote earlier this Spring about income tax transparency, which is mostly about fighting corruption, and somewhat less about fairness.

Salary transparency is an even more radical departure from

current norms than tax transparency. I’m increasingly convinced good business

leaders should institute it as a matter of setting company culture.

Now, before you all freak out, salary transparency actually

is somewhat normal in certain circumstances. As Hawa notes, “The State of Texas

is not a progressive or radical organization, but they decided they needed

salary transparency.”

Texas believes strongly in salary transparency as a public

policy value, presumably for both anti-corruption and fairness reasons. I did an experiment, moments ago, to answer

the question of how long it would take me to figure out Texas Governor Greg

Abbott’s annual salary. The answer, in my case: 46 seconds. He makes $153,750

per year.

But immediately, I realized the next important nuance about

transparency.

One of Hawa’s main warnings is that ‘partial’ salary transparency

is actually destructive. With ‘partial’ disclosure she points out, you move

quickly from no salary information to salary misinformation.

TX. Transparency there is mixed. Easy to find what we pay the Governor. But legislator salaries are misleading

TX. Transparency there is mixed. Easy to find what we pay the Governor. But legislator salaries are misleadingFor example, an online search would tell you that Texas legislators earn $7,200 per year. But that number totally overlooks the generous pensions they can accrue over years of service, as I wrote about back in January. So ‘salary transparency’ can be done well, but it can also be done badly.

It took me 41 seconds to find that my wife has part of her

salary disclosed online as well, as she is paid part-time by a State of Texas

entity. That partial disclosure, however, is misleading because it’s only part

of the story. Again, partial disclosure can obscure rather than illuminate.

Hawa also cited companies that release “salary bands” rather

than all salary data. All that does is potentially hide big differences in

total compensation within wide ranges, like $40,000 differences, as she has observed

elsewhere. Also, releasing general information about characteristics of employees,

like “new hires receive $X in salary, but with some exceptions” can actually deceive.

Why the exceptions? And why the non-identifiable descriptions?

Selective disclosure, Hawa argues, is often worse than no disclosure at all,

because it misleads.

I wondered if only a relatively “flat” organization would

want to radical transparency. Hawa doesn’t think so. Companies should be free

to pay for star performance, as long as management can justify it.

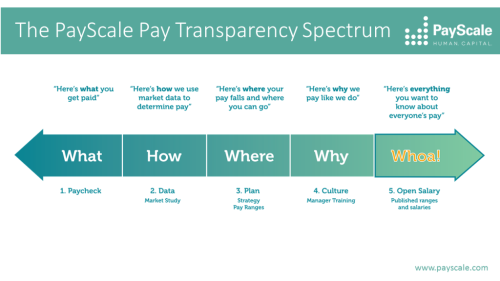

PayScale has a spectrum on the topic

PayScale has a spectrum on the topic“The company doesn’t have to aspire to flatness, but does

have to aspire to fairness,” says Hawa. “Unequal is not the same as

inequitable.” Those seem to me important points as well. Pay as much as you

want or need to, as long as you wouldn’t be embarrassed by everyone knowing

everyone’s pay.

If you’re a business owner who would be embarrassed by full

salary transparency at your firm, what does that say about your method of

paying folks? In an important sense, Hawa believes, the discomfort is the

point. Hawa described her colleagues’ initial discomfort as a positive rather

than a negative.

From Hawa’s perspective, transparency challenges leadership

to be introspective. That’s where the hard conversations, and maybe some

learning, can begin.

Says Hawa, “If you are leader, give yourself the opportunity

to be challenged by your employees. If your salaries are fair, you’re good. If

they are not, you [the manager/owner] have something to learn.”

I’m pretty interested in the thought experiment. This all

got me thinking about the fact that salary transparency is really not

considered ‘normal’ in most workplaces. But why? Why are we unwilling to be

transparent? What are we uncomfortable with? Who benefits from the secrecy?

For competitive reasons, we can all agree it makes sense not

to publish your data to your competitors. But to ensure fairness within your

own organization, wouldn’t full disclosure for current employees reduce

mistrust?

I asked Hawa if she thought disclosure helped managers run

her business better.

“I think there’s a business value in taking this off of

people’s minds.”

And if you are a worker at an organization and the idea of

salary transparency makes you uncomfortable, you should probably realize that

secrecy isn’t your friend. You might have some initial shock and resentment

upon disclosure, sure, but after that you would likely benefit. Secrecy is a

tool in the hands of management.

As Siskel and Ebert once said: All You Have To Lose Are Your Chains

As Siskel and Ebert once said: All You Have To Lose Are Your ChainsI think if you’re a worker worried about salary disclosure, you should remember the words written by a couple of German guys who became famous in 1848: All you have to lose are your chains!

A version of this post previously ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts:

Transparency Part I – TX Legislator Salaries

Transparency Part II – I’m a fan of total income tax transparency

City Economic Development Transparency – SA and Houston failing grades

San Antonio and Houston need transparency taken to 11

Post read (6) times.

The post Transparency Part III – Salaries! All We Have To Lose Is Our Chains! appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

October 29, 2019

Broken Recycling Markets Part IV – Best Household Practices

As recycling commodity markets have swooned the past few years and this former source of city revenue has now become a costs item, what’s a responsible household to do?

The first response is that households can’t do this alone. Recycling involves a complex interconnected chain between raw material producer, manufacturer, transporter, retailer, consumer, and waste processor. Household consumer behavior is only one link in the chain. I’m addressing the household link in the chain here mostly because I figure I have more household consumers reading this column than I have of managers of packaging manufacturers and managers of retail operations.

So, what’s a guy and his big household recycling bin supposed to do?

Until recycling processors change their engineering methods for efficiently separating materials, “less is (probably) more” when it comes to what we put in the recycling bin. Like, if you’re not sure, probably just leave it out. Even if you are sure, try to make sure you are sure, you know? We tend to suffer from a classic behavioral finance error, when it comes to our bins. That error is overconfidence, and putting things in “just in case” they can be recycled. That’s costly.

Republic Services, the nation’s second-largest waste management company reports that 41 percent of households received a “failing grade” on knowing what is, or is not, recyclable.

Josephine Valencia, recycling manager at San Antonio’s Solid Waste Department, explained to me that when the city has surveyed people about what they think goes into the recycling bin, they find that people are vastly overly confident about the wrong things. We think we know what we can recycle, but we are frequently wrong.

Metal

With clean metal soup cans and aluminum beverage cans – these are unreservedly still good for the bin. More than that, they represent the single highest value commodity that you can put into your municipal bin. So, you’re making money for your city when you put those in there.

But what about other metals? Tin foil? Small metal pieces? Metal mixed with plastic packaging? Chances are these aren’t at all recoverable by recycling processors. You’re just raising the cost of processing when you include these in your bin.

Plastic

Plastic single-use water bottles? Those actually are fine and have a market value. Milk jugs too, and even heavier plastic bottles. Practically all other plastics though are headed for the landfill.

About two years ago San Antonio said we could gather our single-use plastic bags into bundles of 30-40 bags, in the shape of a soccer ball. I learned those are headed to the landfill as well, with plastic prices where they are now. That made me sad. Many large retailers will take back the plastic bags, but that extra layer of effort is, well, not something I currently do. I liked making the soccer balls, darnit!

Paper

Paper is more fraught than I expected. It turns out most recycling processors were not built for the volume of small Amazon-style cardboard boxes we produce in 2019. Until that gets fixed at the processing plant, most of these are not getting efficiently recycled, to my chagrin.

Mixed paper is hardly worth anything these days, and cities are currently paying processors to take it off their hands.

Glass

And then there’s glass. This is a money loser for cities. It’s mentally difficult to landfill glass because it’s quite recyclable. And yet, the finance guy in me knows I’m just raising costs when I put glass in the bin. I’m torn.

Mixed Packaging

Most all mixed-packaging, which increasingly fills our shopping carts, is not recyclable. Your favorite thin salty chips come in in that cylindrical can made up of paper but with a metal lining inside? Totally not recyclable.

The metal trays from your favorite fast food barbecue place are not recyclable.

Plastic toys are generally not recyclable.

Plasticware from your take-out restaurant is not recyclable.

Generally plastics that aren’t a water bottle, milk jug or cleaned plastic can’t be recycled.

Clothing is not recyclable. Bring it to Goodwill.

And for goodness’ sakes, diapers are not recyclable. That’s for the trash bin only.

“When in doubt, leave it out” is what the experts keep telling me. By putting iffy items into the recycling bin you are simply raising the cost of processing, which gets passed on to municipalities one way or another, which we ultimately cover in our taxes.

I’m a markets guy, so I tend to think that recycling doesn’t have a chance unless we align dollars and self-interest with best waste management practices. I’ve come to appreciate that this is

1. Super-duper complicated and

2. Sustainable financially and environmentally only if everyone in the waste production and management chain is working together. It’s so complicated that it’s far easier to come up with questions rather than solutions or answers.

Big Questions for the Future

A few fundamental questions that learning about this raised for me:

Can households be trained better to recycle only the limited number of financially viable commodities like cans, tins, water bottles, and clean plastic jugs?

Can households some day be trained to actually separate their commodities into more valuable sorted bins, as is done in Europe and Japan?

Will consumers prioritize buying recyclable packaging materials in a way that will force manufacturers and retailers to respond to market demand?

Can manufacturers be incentivized to create more recycled and recyclable packaging, rather than mixing paper, plastic and metal in a way that can’t conceivably be recovered from household waste?

Can retailers be incentivized to serve as the feedback mechanism for channeling consumer preferences to food manufacturers?

Can recycling processers adjust their collecting and sorting processes in a cost-effective way to constantly-changing packaging?

Will municipal, state, and national government policies nudge – in a sustainable way – for more efficient recovery and reuse of materials?

The recycling market is in a period of transition caused by a market slump.

An optimistic view would be that technological and engineering changes, combined with household changes, can mitigate and even solve our problems in the future.

Energy and environment expert Rachel Meidl of Rice University’s Baker Institute says she doesn’t see the China ban or current commodity slumps “as a crippling force. I see it as an opportunity to prepare and strategize for the next generation of recycling and innovation. A long-term sustainable solution would be investing in R&D and scaling up infrastructure to recycle or recover” more commodities.

That, combined with household behavior, would help over the medium and long run. I don’t know enough whether to be optimistic or pessimistic about the current crisis. I’m going to try to do better with my bin though, and leave the rest to the experts.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle.

Please see related posts

Broken Recylcing Markets Part I – China Ban, market swoon

Broken Recycling Markets Part II – Commodity Markets slump

Broken Recycling Markets Part III – Hit on City Budgets

Organic Recycling – Green in Being Green

Post read (7) times.

The post Broken Recycling Markets Part IV – Best Household Practices appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

October 28, 2019

FIRE Part I – Taxonomy of Early Retirement

Up until now I’ve mostly ignored the Millennial FIRE movement, which stands for Financial Independence, Retire Early.

My buddy Justin S. introduced me to some retirement planning strategies I’d never heard of recently, strategies that he is considering using in the next few years as part of his FIRE plan. FIRE is the aspiration of many 20 and 30-somethings, who hope to quit their jobs by age 40 or so. It would be easy – as with all trends involving Millennials – to exaggerate and strawman-ify the FIRE movement.

Justin, a software engineer at a large financial services company in San Antonio, is 39 years young. He hopes to be able to retire within the next five years.

Justin’s FIRE journey began 1.5 years ago when he and his wife began to really examine what role paid work should, and should not, play in their lives. It was at that point that they got serious about trying to accumulate savings enough to let them walk away from work within ten years.

He says his wife had always been a natural saver, whereas he had enjoyed buying nice cars and a motorcycle. In an earlier phase of life he’d bought a condo at the worst time and place (Central Florida, 2007), an experience that left him with wrecked credit and a searing fear of being stuck financially, living paycheck-to-paycheck.

Says Justin, “My primary driver is to not be in a position like that again. Anything can happen at work, anything can happen with houses.”

He’s gotten deep into FIRE-oriented blogs, retirement strategies, and tracks his progress on a free website.

with numerous retirement calculators. His ultimate goal is to have enough saved that he could choose more hands-on work. He seeks something more tangible than software, something that would give him a more tangible sense of accomplishment.

Justin explained to me the many variations on FIRE. To save you some time navigating Reddit threads, finance blogs and YouTube channels, here’s your guide to different FIRE flavors.

Lean FIRE – This is Justin’s plan. This means figuring out the bare minimum income you need to survive on annually, usually by making choices to downsize a home and car, location, and lifestyle. If Justin and his wife can figure out a way to live on $35,000 per year total, for example, and assume a 5% annual withdrawal rate, then theoretically they would only need $700,000 in a nest egg to call it quits in five years. (These are my numbers, not theirs, and just reflects a starting point for planning)

Obviously they (or we) can tweak some assumption about tax rates, rates of return, inflation, and their ability to eat only rice and beans forever, but you can sort of see the initial plan start to come together.

Inherent in Justin’s Lean FIRE planning, he says, is a commitment to live cheaply enough that work isn’t necessary. If that means living in a lower-cost state, or even a lower-cost country, he’s ok with that. Their reward will be freedom from having to work in an office or depend on a paycheck in the future.

Fat FIRE – This is for folks who make a high enough income that they can build a hefty nest egg for later. Generally this also means sacrificing current wants to ensure future luxury. Or as Justin says, Fat FIRE adherents want to live middle class today in order to live upper class in the future. Of course, part of the goal is to build that nest egg as quickly as possible in order to still retire early. A Fat FIRE pile of savings is by definition far higher than a lean FIRE pile of savings.

Barista FIRE – This is for current corporate drones who dream of giving up a career advancement and responsibility and who have seek to have enough money in the bank to just work a minimum wage job with good benefits. Since healthcare costs naturally represent a major barrier to early retirement, the “Barista FIRE” enthusiast may sign up to work for a company like Starbucks, post-retirement, for the generous benefits rather than for the paycheck. FIRE in this case doesn’t mean a full retirement but rather the independence from work that requires long-term responsibility, career, and those jerks from headquarters requesting you come in to finish those TPS reports on Saturdays.

Coast FIRE – This is for folks who have made their “number” for financial independence but don’t actually have an incentive to quit yet. Maybe their spouse isn’t ready to retire early, so it’s worth hanging on to a job. But they can ‘coast’ for a while without the pressure to actually work to pay one’s bills.

All in all, of course, you can criticize and exaggerate these different versions of financial independence and retiring early. Assumptions may strike us as unrealistic. The goal may seem overly materialistic, or not materialistic enough. Personally, my main objection to seeking to retire early is that work is what gives us meaning. If we don’t like work and seek an early retirement, maybe the solution is to seek different work that better suits our skills and interests?

Older barista may be totally financially secure, just doing it for the healthcare.

Older barista may be totally financially secure, just doing it for the healthcare.And yet, every responsible financial planner would ask her client to set forth a future plan, make realistic assumptions about savings and investment to get there, and then ask what the client is willing to give up to make the future a reality. That’s what the FIRE adherents are doing. Financial independence always requires some version of these steps, even if some FIRE enthusiasts take it to the extreme.

At the extreme, of course, even the financial independence aspect of FIRE can be overdone. Just as body dysmorphia pushes even the thinnest people to cut calories, so can the FIRE movement lead to penny-pinching absurdity. Justin is not in that problematic category, but you don’t have to look hard online to see people maximizing their savings to an extreme that doesn’t make a ton of sense.

What about those specific FIRE retirement account strategies Justin mentioned that I hadn’t heard of before? I looked into them. They aren’t exactly universally recommended – nor is FIRE for that matter – but I’ll describe them in more detail in an upcoming column.

Please see related posts:

FIRE Part II – Some Complex Techniques

FIRE Part III – On the Benefits of Frugality

Post read (27) times.

The post FIRE Part I – Taxonomy of Early Retirement appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

October 25, 2019

Transparency Part II – TOTAL Tax Transparency

I’ve been reading up on “tax transparency” lately and have become a convert to the idea. The idea is that the IRS could and should publish online, in a searchable database, the annual income and income taxes paid by all taxpayers.

I’ve got political, economic, and sociological reasons for my conversion.

You probably already anticipate the political. Most Democratic presidential candidates this month have rushed to release a decade’s worth of their personal tax returns. They do this in part to contrast with President Trump, who has broken with forty years of tradition by not releasing his own tax returns. His stated reason is that his returns are “under audit” with the IRS. An audit process, however, does not prevent voluntary disclosure, according to the IRS itself.

But there is a better way. You’re going to love this idea.

If you’ve ever read my columns before, you probably realize that when I say “You’re going to love this,” I actually mean that you’ll probably hate this.

Let’s not limit ourselves to begging for voluntary disclosure by a president, or presidential contenders. Let’s get it all out there. For everyone. That was the rule back in 1924. The IRS made public the amount of taxes paid by every individual and corporation. I say we reinstitute that rule, which was unfortunately repealed in 1926.

What happens when you disclose everyone’s income and taxes paid publically?

A primary goal of income and tax transparency is to deter tax evasion, especially by powerful people. A secondary goal is to increase the amount of taxes paid. A tertiary goal is that we get to address important issues like wage inequality.

A paper published in February 2019 by the National Bureau of Economic Research describes Pakistan’s recent experience with tax disclosure.

In Pakistan, the government began in 2012 to publish how much both elected officials and citizens earned in income and paid in taxes.

This has direct relevance to the current United States situation, since the program began as a result of press reports that elected officials had not been paying their taxes.

What better way to ensure compliance and trust in the system than 100% exposure of all citizens’ income and taxes paid? Sunlight, as they say, is a great disinfectant.

In Pakistan, two free searchable directories are published in PDF form online each year. The first is income earned and taxes paid by all members of Parliament. The second directory has the same tax information on all taxpayers, searchable by name.

One hoped-for effect with this program is to encourage whistleblowers to come forward if they suspect someone, like a political rival or a neighbor, of not paying their fair share of taxes.

As a result of this program, among members of parliament in Pakistan, tax compliance moved from 30% to 90% within the first year of the program – an extremely dramatic jump. I feel like this kind of effect on public officials of tax transparency should be a requirement in a democracy.

For an entire society, individuals would be less likely to attempt illegal tax avoidance, or even plausibly legal but overly aggressive attempts to reduce taxes, if they knew others would be watching. Other taxpayers may enjoy the “bragging rights” afforded by high reported income and high tax compliance, possibly helping bring in additional revenue.

Norway has a strong tradition of tax transparency, dating to the 19th Century. Beginning in 2001, the central government began to publish all taxpayer wages and taxes paid online, searchable by anyone

A Norwegian study from 2014 found that business owners’ reported income increased by 3% on average following the change to total transparency, with a 0.2% bump in taxes collected. Higher reported income leads to higher taxes paid. An equivalent jump in taxes in the US would raise $3.2 billion. The effect is larger on business incomes rather than salaried incomes because of the extra wiggle room that businesses enjoy to report and pay taxes, when compared to W2-type earnings that are independently reported.

Norway: Earth Porn and Tax Porn! Photo credit : TORE MEEK/AFP/Getty Images)

Norway: Earth Porn and Tax Porn! Photo credit : TORE MEEK/AFP/Getty Images)Pakistan and Norway are not the only countries to experiment with tax transparency. Italy tried it in 2008, posting all tax returns from 2005 online, before taking down the information, following protests.

Greece and New Zealand use public exposure of tax evaders to encourage compliance.

This tax transparency may all sound radical, but we already have a small version of this in the United States. And life goes on. I just mean the fact that I can look up property taxes owed and paid by almost anyone who lives near me through a simple internet search of county records.

Academic studies do acknowledge some downsides to transparency. Some consider this an invasion of privacy. We could easily imagine some embarrassment or even harassment about one’s level of income.

Apparently in Norway, the well-known practice of “tax porn” internet searches – looking up people’s income for voyeuristic purposes – actually makes people unhappier in some instances.

As a result, since 2013 in Norway, the subject of a tax search is informed of who is doing the searching. This has led to a drop from 16.5 million searches to 2.15 million searches in the year after implementation of the rule change, all on a population of 5 million.

When I am declared benevolent dictator of this fair land, I will look to institute tax transparency similar to what they have now in Norway and Pakistan – an easy internet search of anyone’s net worth, taxes owed, and taxes paid. A moderate charge for each search would make it a revenue generator for my government’s coffers. The moderate charge would also limit “tax porn” searches and encourage tax compliance.

One additional benefit of this proposed database would be to equalize pay. Efficient markets, including markets for work, depend on the free flow of information. Pay information, however, is often obscured and secret. A 2010 economics paper found that disclosure of income not only mattered to lower-income people, but prompted them to take action, such as look for higher paid work. Under my tax transparency regime, people would have the information to make their arguments for better pay and equality.

Finally, Joel Slemrod, the University of Michigan economist who co-authored both papers on tax transparency in Norway and Pakistan, also published a paper in 2015 with the intriguing title “Sexing Up Tax Administration.”

Let me know if you need a synopsis of that one in an upcoming post.

Please see related post

Transparency Part I – Legislative Salaries

Transparency Part III – Salaries

Post read (14) times.

The post Transparency Part II – TOTAL Tax Transparency appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.

October 22, 2019

Recycling Part III – Bottom Line For Cities

In the past decade most cities have benefitted financially from developing robust recycling programs, helping cities financially in two ways. First, by diverting tons of waste away from landfill, cities reduce their landfill costs. Second, by hiring recycling processors who can resell and share profits from the resale of secondary commodities like metal, paper, and plastic, cities have earned positive revenues from their programs.

A slump in commodity prices as well as other market factors, however, have fundamentally shifted this second factor in the municipal economics of recycling. A snapshot of San Antonio and Houston contracts illustrates the market change over just the past three years.

Houston has seen a swift financial change in their recycling deal.

Houston

Before 2016, Houston had enjoyed a contract with Waste Management in which the processor would not charge anything to haul recyclables, and would split the upside of revenues as it sold recovered materials into the secondary commodity markets. Recycling made money for Houston, with no financial downside.

Houston skyline

Houston skylineAt the end of that contract in 2016, however, Houston endured temporary contracts and exposure to faltering markets. Between 2016 and 2019, the city paid $92 per ton for hauling and processing, a cost per ton that ended up costing the city an average of $120,000 per month. Also, under temporary contracts, there was no predictability to what the program could cost.

Houston’s new contract with Spanish processor FCC went into effect in March 2019, requiring the city to pay $87.05 per ton of recycled waste. Like most municipal contracts, Houston can share in the revenue that FCC generates through secondary sales, and use that revenue to offset the costs of hauling and processing.

Says Sarah Mason, Division Manager of Recycling at Houston’s Solid Waste Management Department “We were aware that the commodities market was on the downside at the time we were working out the [present 2019] contract.”

Given that exposure, Mason says, they negotiated a maximum net cost of $19 per ton, even if recovered commodity revenues remained weak. Houston has hit the $19 cap every month the contract has been in effect. This cost cap has cut recycling costs to about a third, or an average of $41,000 per month. Still, it’s a contract that reflects the new altered dynamics of the recycling market in 2019. A former revenue source has become a net cost to the city budget.

Meanwhile, a three hours’ drive west on I-10, San Antonio has a few years remaining on its contract, one negotiated in better times.

San Antonio

Costs to haul and process recycled materials are just over $36 per ton through 2024, according to their contract with Republic Services, which by comparison with Houston seems quite low. An additional “contamination” fee for non-recycled waste that gets mixed in with the recyclables typically raises the costs by another $12.50 per ton. San Antonio’s experience is that contamination fee typically kicks in every month.

San Antonio skyline

San Antonio skylineIn good years, prior to 2017, San Antonio expected secondary commodity revenues to more than offset its costs. The city enjoyed a 50/50 split on revenues above costs. If revenues brought in $72 per ton, the entire program would be paid for.

Recovered revenues above $72 per ton ended up as a net revenue-generator for San Antonio. In addition, Republic agreed that if recoveries didn’t fully match costs, the city could roll over its net costs, with a promise of owing nothing if recoveries over the life of the contract proved insufficient. That’s how confident Republic must have been in its ability to make money from recovered paper, plastic, and metal, under the old contract, negotiated in the 2013/2014 period.

Financial data shared by Josephine Valencia of recycling manager of the Solid Waste Management Department of San Antonio show net revenues have on average been negative in 2018 and 2019. Net 2018 revenues from recycling averaged negative $2.60 per ton in 2018, and worsened to an average of negative $9.45 per ton, reflecting declining commodity markets. The average recycling costs would be over $60,000 per month in 2019, although Republic will eventually absorb those monthly losses if commodity markets do not recover. San Antonio’s contract lasts through 2024, but if present conditions persisted the city could expect that kind of cost would factor into any new negotiated contract.

In other words, future municipal recycling contacts – if commodity market conditions do not change – will lock in recycling as a loss-maker rather than revenue-generator for cities in the future. Valencia confirmed that Houston and San Antonio’s shift from monthly gain to monthly loss are probably happening nationwide, at least in cities that employ the popular “single bin” method of household recycling.

Don’t forget landfill-cost comparison

The contracted costs from Houston and San Antonio simplify the total financial picture somewhat, because they do not reflect at least one big factor. Recycling lowers waste management costs overall by redirecting waste away from landfills. The City of San Antonio estimates 2018 and 2019 savings from reduced landfilling at approximately $1.5 million and $1 million respectively, according to Valencia, on a total waste management budget of $150 million. That’s not nothing, and provides a compelling reason to continue the programs, even as they do not produce the positive cash flows of the past.

A version of this post ran in the San Antonio Express News and Houston Chronicle

Please see related posts

Broken Recycling Markets Part I – The Plastic Ban and Commodity Swoon

Broken Recycling Markets Part II – Commodity Market Prices

Recycling Part IV – Best Household Practices (forthcoming)

Organic Recycling – Green to Green

Post read (6) times.

The post Recycling Part III – Bottom Line For Cities appeared first on Bankers Anonymous.