Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 33

April 11, 2023

Alexander the Great and Stoicism

Hellenism he spread far and wide

The Macedonian learned mind

Their culture was a western way of life

He paved the way for Christianity. – Iron Maiden, Alexander the Great

It might seem like a surprising claim but, according to Plutarch, Alexander the Great was not only a true philosopher but also paved the way for the ethical “cosmopolitanism” of Hellenistic philosophy, particularly Stoicism, by founding an empire based on the principle that all humans, regardless of their native race or tribe, could, in some sense, be viewed as fellow-citizens of a single world community. This idea arguably laid the foundations for the Christian doctrine, three centuries later, of a brotherhood of man, and the virtue of brotherly love or philadelphia.

Plutarch was himself a philosopher of the Academic school, and also a priest at the famous Temple of Apollo in Delphi. Although was born in the middle of the 1st century CE, nearly four centuries after the death of Alexander, he is one of our main sources of information on the life of the famous King of Macedonia and conqueror of Persia. In addition to his biography of Alexander, in Parallel Lives, though, Plutarch wrote a less well-known essay titled On the fortune or the excellence of Alexander.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The explicit purpose of Plutarch’s essay is to argue that whereas many other rulers had benefited from good fortune, being born into great wealth and power, Alexander conquered a vast empire starting with relatively humble resources. In his early days, as a young prince of Macedonia, it would have been difficult to imagine how he could hope to defeat the might of Darius III, the Great King of Persia. Alexander’s extraordinary achievements, claims Plutarch, must therefore be attributed not primarily to good fortune but to his exceptional strength of character, or arete, meaning virtue or excellence.

Marcus Aurelius lumps Alexander together with famous military leaders… who are nevertheless viewed with disdain by philosophers.

Stoic Criticisms of AlexanderAlthough Alexander was certainly widely revered for his military achievements, some philosophers considered him to have been the opposite of a wise and virtuous ruler. Marcus Aurelius, for instance, lumps Alexander together with Julius Caesar, and his rival Pompey the Great, as examples of famous military leaders, who are nevertheless viewed with disdain by philosophers. For instance, he says that Alexander, and the other two, “often razed whole cities to the ground and slaughtered tens of thousands of horsemen and foot-soldiers on the battlefield.” Nevertheless, he adds, “there came a day when they too departed from this life” (Meditations, 3.3).

Indeed, “Alexander the Great and his stable boy were brought to the same level in death”, either dissolved back into the unity of Zeus or perhaps dispersed among random atoms (Meditations, 6.24). The achievements of these rulers impress ordinary people but they’re of little importance in the grand scheme of things. Though remembered for many centuries, they will one day be forgotten. “Go on, then, and talk to me of Alexander,” says Marcus, and of other celebrated rulers.

If they saw what universal nature wishes and trained themselves accordingly, I will follow them; but if they merely strutted around like stage heroes, no one has condemned me to imitate them. The work of philosophy is simple and modest; do not seduce me into vain ostentation. (Meditations, 9.29)

The great philosophers, says Marcus, were in control of their own minds, understood life properly, and distinguished between events and their causes. Wisdom, in other words, is more important than glory.

As for the great military leaders of history, he says, “consider how many cares they had and to how many things they were enslaved!” Although they were, in their times, the most powerful men in the world, Alexander, and others like him, were enslaved by their own passions, such as the craving for glory. They lacked insight into their own minds and therefore they lacked self-control. “What are Alexander, Julius Caesar, and Pompey when compared to Diogenes the Cynic, Heraclitus, and Socrates?”, he exclaims (Meditations, 8.3).

Alexander the “Philosopher”Plutarch, by contrast, actually argues that Alexander owed his greatness to philosophy. In On the fortune or the excellence of Alexander, he says that Aristotle, Alexander’s tutor, provided him with greatness of soul, quick thinking, temperance, and courage. Alexander, he claims, owed his success more to the education he had received from Aristotle than to the wealth and resources he was fortunate enough to have inherited from his father, Philip, the King of Macedonia.

Plutarch even goes so far as to insist that Alexander was himself, in a sense, a philosopher.

Plutarch even goes so far as to insist that Alexander was himself, in a sense, a philosopher. Some, he concedes, may object that Alexander never discoursed on philosophy at the Lyceum or Academy, and that he wrote nothing on the subject, and did not bring philosophical treatises with him to study on campaign, about “Fearlessness and Courage, and Temperance also, and Greatness of Soul”. “For it is by these criteria”, sniffs Plutarch, “that those define philosophy who regard it as a theoretical rather than a practical pursuit.”

However, he points out that Pythagoras, Socrates, and many other great philosophers did not leave behind writings of their own, and that true philosophers are judged not by their theoretical scholarship, or writings, but by their own lives, and the principles they espoused, and taught others. “By these criteria let Alexander also be judged!”, he says, confidently asserting that “from his words, from his deeds, and from the instruction which he imparted,” it will be evident, surprising though it may sound, that Alexander was indeed a philosopher.

Plutarch notes that whereas Socrates struggled to improve some of his wayward students, such as Critias and Alcibiades, although they were educated native Athenians, Alexander, by contrast, succeeded in bringing Greek culture and civilization to countless “barbarian” tribes throughout Asia, even persuading “the Indians to worship Greek gods”. Alexander was, therefore, he notes, far more successful than Socrates at spreading enlightenment, based on Greek culture and wisdom, to a larger number of people.

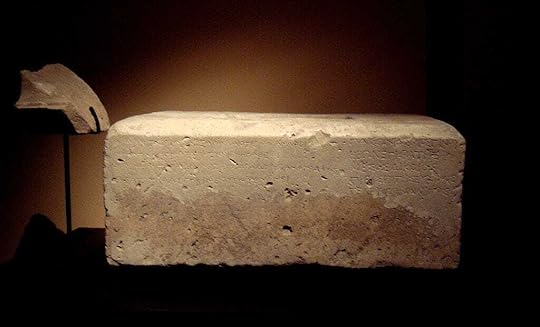

Greek inscription of some Delphic maxims from 2nd century BCE, found at Al-Khanoum in modern-day Afghanistan.

Greek inscription of some Delphic maxims from 2nd century BCE, found at Al-Khanoum in modern-day Afghanistan. Likewise, whereas Plato wrote books on politics, laws, and the ideal Republic, he was unable to convince anyone to establish a society based upon them. Alexander, by contrast, says Plutarch, “established more than seventy cities among savage tribes and sowed all Asia with Grecian magistracies, and thus overcame its uncivilised and brutish manner of living.”

Although few of us read Plato's Laws, yet hundreds of thousands have made use of Alexander's laws, and continue to use them.

Indeed, he makes the striking claim that those “who were vanquished by Alexander are happier than those who escaped his hand”. This remark seems quite presumptuous, and overtly-colonialist, but Plutarch feels it is justified because so many major cities that had once formed part of Alexander’s empire still embraced Hellenism, and continued to flourish, more than four centuries after his demise. Alexander, he argues, spread Greek civilization throughout the known world, establishing the institutions that would preserve wisdom and justice more effectively than any philosopher. The great library at Alexandria, in Egypt, founded by his successor, Ptolemy, would eventually become one of the most famous seats of learning in European history.

If, then, philosophers take the greatest pride in civilizing and rendering adaptable the intractable and untutored elements in human character, and if Alexander has been shown to have changed the savage natures of countless tribes, it is with good reason that he should be regarded as a very great philosopher.

The term “Hellenization” refers to this adoption of Greek culture and language by non-Greek (“barbarian”) people, which typically resulted in a hybrid of cultures, as in the Hellenization of Egypt. After the death of Alexander, though his empire fragmented, into several kingdoms ruled by his generals, the spread of Hellenism continued in this way, but it also began to influence a new wave of emerging philosophical systems, including Stoicism.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Alexander and StoicismZeno, the founder of Stoicism, was a Hellenized, Greek-speaking, Phoenician merchant, from Cyprus, who arrived at Athens a few years after the demise of Alexander the Great. Zeno studied several of the schools of philosophy at Athens before, in 301 BCE, founding his own school, which came to be known as the Stoa after the Stoa Poikile, a painted porch in the Athenian Agora where his followers gathered. Zeno was known, at first, as a follower of the Cynic philosophy, and the first book he wrote was the heavily Cynic-influenced Republic, a critique of Plato’s treatise, of the same name, on justice, and the ideal state. (Our sources also refer to a text attributed to Diogenes, the founder of Cynicism, titled the Republic, which appears closely related to, or was perhaps even confused with, the book by Zeno.)

Plutarch, a follower of the rival Academic school, drew inspiration from the Stoics but was, at times, also very critical of them. However, in On the fortune or the excellence of Alexander, he claims that the political ideals of Zeno, and the early Stoics, had already been implemented, in practice, by Alexander.

Moreover, the much-admired Republic of Zeno, the founder of the Stoic sect, may be summed up in this one main principle: that all the inhabitants of this world of ours should not live differentiated by their respective rules of justice into separate cities and communities, but that we should consider all men to be of one community and one polity, and that we should have a common life and an order common to us all, even as a herd that feeds together and shares the pasturage of a common field. This Zeno wrote, giving shape to a dream or, as it were, shadowy picture of a well-ordered and philosophic commonwealth; but it was Alexander who gave effect to the idea.

Plutarch’s calls this Zeno’s “dream”, implying that it was a Utopian vision. He says that Alexander was the one, a generation earlier, who had first made this a political reality, though. Plutarch can be read as implying that it was actually the cosmopolitanism of Alexander’s empire, in other words, that paved the way for Zeno’s vision of an ideal Stoic Republic.

Alexander, he says, totally rejected the advice of his teacher, Aristotle, “to treat the Greeks as if he were their leader, and other peoples as if he were their master”, or a tyrant. The Macedonian philosopher had told his king, allegedly, to view only their fellow Greeks as friends and kin, but to treat “barbarian” races, such as the Persians, “as though they were plants or animals”, something less than human. Once Alexander found himself controlling most of the former Persian empire, though, he realized it would be impractical to follow this advice. Treating the “barbarian” tribes that surrounded him as inferior to his Macedonian troops would have bogged Alexander down in ethnic conflict, festering rebellions, and other needless obstacles. He had to turn the local population into his allies.

Alexander saw his divinely-assigned role as being a “common moderator and arbiter of all nations”, although he conquered by force those who would not join his empire voluntarily. Nevertheless, he succeeded in bringing together countless foreign tribes, far and wide, under a single dominion. Uniting and mixing, as though in one great “festival cup”, as Plutarch puts it, men’s lives, culture, marriages, and customs. The inhabitants of Alexander’s new empire were to view themselves as citizens of the whole world, with his military camp, wherever it may be, serving as their capital city.

He bade them all consider as their fatherland the whole inhabited earth, as their stronghold and protection his camp, as akin to them all good men, and as foreigners only the wicked.

They were no longer to distinguish Greeks, with their cloaks and shields, from “barbarians” with their scimitars and long-sleeved jackets. Rather, said Alexander, a man should be called a Greek if he is an ally, and virtuous, and a “barbarian”, only if he is vicious and an enemy. There would, in other words, be no distinction based on race, but a fellow-countryman could be anyone who behaved like a friend. Clothing and food, says Plutarch, marriage and customs, were to be regarded as common, “blended into one by ties of blood and children”, as his men were encouraged to marry native women.

Plutarch says that Xerxes, the Great King of Persia, seems foolish, in retrospect, for expending so much time on military efforts to invade Greece and extend his kingdom across the Hellespont, from Asia into Europe. Alexander finally managed to unite Greece and Persia by holding a joint wedding ceremony for a hundred couples, Persian brides and Macedonian soldiers, and thereby “bridged the Hellespont”, not with lifeless rafts, but by creating genuine blood ties between their people, lasting for generations.

Plutarch claims that Alexander himself adopted a form of dress combining elements of both Persian and Macedonian styles, in order to show respect for the culture of the region in which he had established his camp. “As a philosopher what he wore was a matter of indifference,” says Plutarch. He even says that it is the “mark of an unwise and vainglorious mind” to prefer a plain robe of uniform color, such as those traditionally worn by Cynics and Stoics, and to be displeased by a tunic with a purple border, the regal color, which philosophers typically held up as an emblem of vanity and self-aggrandizement. Plutarch complains that some critics “impeach Alexander because, although paying due respect to his own national dress, he did not disdain that of his conquered subjects in establishing the beginnings of a vast empire.”

Moreover, Alexander did not, he says, typically loot the countries that he conquered, like other rulers, but rather he “desired to render all upon earth subject to one law of reason and one form of government and to reveal all men as one people, and to this purpose he made himself conform.”

Therefore, in the first place, the very plan and design of Alexander's expedition commends the man as a philosopher in his purpose not to win for himself luxury and extravagant living, but to win for all men concord and peace and community of interests.

If Alexander had not died young, says Plutarch, “one law would govern all mankind, and they all would look toward one rule of justice as though toward a common source of light.” He concludes that Alexander was a philosopher, first and foremost, because of his cosmopolitan vision for society.

Alexander’s Words and DeedsIn the second place, though, according to Plutarch, Alexander was also shown to be a true philosopher, by certain sayings, and actions, which revealed his character as virtuous and magnanimous.

Are not these the words of a truly philosophic spirit which, because of its rapture for noble things, already revolts against mere physical encumbrances?

When, according to legend, Alexander met Diogenes the Cynic in Corinth, he came away so impressed that thereafter he frequently said, “If I were not Alexander,I should be Diogenes.” “Thus it is the mark of a truly philosophic soul to be in love with wisdom and to admire wise men most of all,” says Plutarch, “and this was more characteristic of Alexander than of any other king.”

[Alexander] confirms the truth of that principle of the Stoics which declares that every act which the wise man performs is an activity in accord with every virtue. — Plutarch

Plutarch says that this is demonstrated by Alexander’s respect for Aristotle, that he was a patron of the Skeptic philosopher, Pyrrho of Elis, and of Xenocrates the Academic, and that he allegedly made Onesicritus, the Cynic, a follower of Diogenes, the chief pilot of his fleet.

For, by Heaven, it is impossible for me to distinguish his several actions and say that this betokens his courage, this his humanity, this his self-control, but everything he did seems the combined product of all the virtues; for he confirms the truth of that principle of the Stoics which declares that every act which the wise man performs is an activity in accord with every virtue; and although, as it appears, one particular virtue performs the chief role in every act, yet it but heartens on the other virtues and directs them toward the goal.

Plutarch goes so far as to say that after recounting each of the deeds of Alexander he wants to exclaim “Like a philosopher!” He gives several examples but one should suffice here:

When he saw Darius pierced through by javelins, he did not offer sacrifice nor raise the paean of victory to indicate that the long war had come to an end ; but he took off his own cloak and threw it over the corpse as though to conceal the divine retribution that waits upon the lot of kings. ‘Like a philosopher!’

Plutarch says that all men have the capacity for wisdom, and Nature herself is capable of leading any one of us toward virtue and what is good. In the face of adversity, however, our wisdom is prone to abandon us. Philosophers, however, have the advantage of having, by means of rational argument, secured their principles, in advance, so that their judgement may remain sound in the face of danger.

Fear not only drives out memory, he says,“but it also drives out every purpose and ambition and impulse, unless philosophy has drawn her cords about them.” Alexander, by contrast, courage and self-mastery were so firmly entrenched in Alexander’s character that he remained faithful to them during the most challenging times. That practical wisdom is what made him exceptional, rather than scholarship or theoretical knowledge of philosophy.

The Politics of ZenoAfter the death of Alexander, when Zeno was still a young boy, in 323 BCE, his short-lived empire fragmented into several successor states, over which his generals fought. Macedonia, Cyprus, Athens, and the rest Greece eventually came under the control of the Antigonid dynasty, founded by one of Alexander’s generals called Antigonus I Monophthalmus, the one-eyed. His grandson, Antigonus II Gonatas, had inherited this kingdom, or small empire, by the time Zeno founded the Stoic school, in 301 BCE.

The younger Antigonus was known as a patron of philosophers, particularly the Cynics and, subsequently, the Stoics. Indeed, he appears to have become a prominent student and follower of Zeno. Diogenes Laertius mentions Antigonus many times throughout his Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, where he states:

Antigonus (Gonatas) also favoured him [Zeno], and whenever he came to Athens would hear him lecture and often invited him to come to his court.

Following the death of Zeno, under the rule of Antigonus, pillars were erected commemorating the founder of Stoic philosophy, in the grounds of both the Lyceum and Academy of Athens. Antigonus subsequently donated a large sum of money to Cleanthes, the second head of the Stoic school, to fund its continuation.

Although we tend to think of the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius as the most famous example of a Stoic-influenced ruler, Antigonus II Gonatas, four centuries earlier, was apparently both a Stoic and a king. Zeno’s cosmopolitan vision of the ideal Stoic Republic, which Plutarch claims to be inspired by Alexander’s Hellenism, presumably had some influence upon Antigonus, although links between the teachings of Stoic philosophy and the policies of his rule are difficult to discern from the sparse historical evidence.

As we’ve seen, in his On the fortune or the virtue of Alexander, Plutarch sums up the Utopian political ideals of Zeno’s early Stoicism as teaching that “all the inhabitants of this world of ours should not live differentiated by their respective rules of justice into separate cities and communities, but that we should consider all men to be of one community and one polity”. It was this cosmopolitan philosophy, which Plutarch says was first introduced by Alexander who encouraged his army, and conquered subjects, to “consider as their fatherland the whole inhabited earth”, of which his military camp formed the capital.

Diogenes Laertius likewise claims that a text called the Republic, attributed to Diogenes the Cynic stated that “The only true commonwealth was that which is as wide as the universe”, and the Republic of Zeno appears to have closely resembled this text. Many controversial views were attributed to Zeno’s Republic by critics of Stoicism, from which it’s difficult to ascertain the truth about its contents. However, it’s worth noting, in relation to what Plutarch said, that the satirist Lucian later described the Stoic ideal Republic as follows:

I remember hearing a description of it all once before from an old man, who urged me to go there with him. He would show me the way, enroll me when I got there, introduce me to his own circles, and promise me a share in the universal Happiness. But I was stiff-necked, in my youthful folly (it was some fifteen years ago); else might I have been in the outskirts, nay, haply at the very gates, by now. Among the noteworthy things he told me, I seem to remember these: all the citizens are aliens and foreigners, not a native among them; they include numbers of barbarians, slaves, cripples, dwarfs, and poor; in fact any one is admitted; for their law does not associate the franchise with income, with shape, size, or beauty, with old or brilliant ancestry; these things are not considered at all; any one who would be a citizen needs only understanding, zeal for the right, energy, perseverance, fortitude and resolution in facing all the trials of the road; whoever proves his possession of these by persisting till he reaches the city is ipso facto a full citizen, regardless of his antecedents. Such distinctions as superior and inferior, noble and common, bond and free, simply do not exist there, even in name. — Hermotimus, or the Rival Philosophies.

This is clearly philosophical cosmopolitanism. Full citizenship, though, is equated here with wisdom and virtue, rather than merely allegiance to Alexander or his successors, although the spread of Hellenism through their conquests perhaps helped to make this philosophical vision conceivable.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

ConclusionAlmost five centuries after Zeno founded the Stoic school, the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, the last famous Stoic of antiquity, described his political vision, in one of the most remarkable passages of the Meditations:

…the idea of a republic in which there is the same law for all, a republic administered with regard to equal rights and equal freedom of speech, and the idea of a kingly government which respects most of all the freedom of the governed. — Meditations, 1.14

Throughout the Meditations, Marcus alludes to the importance of seeing the rest of mankind, even our enemies, as brothers, and our kin. Marcus appears, as we’ve seen, to have resisted the Roman habit of placing Alexander on a pedestal — and he was perhaps no great admirer of him. Nevertheless, if Alexander’s imperialism paved the way for early Stoic cosmopolitanism, as Plutarch claimed, it’s perhaps no surprise that a Roman emperor would find Stoicism so congenial to his own political values.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

April 8, 2023

Stoicism and Resilience Webinar

I’ve been fortunate enough to be involved in a number of conferences and webinars on Stoicism and resilience for the army, marine corps, police, and government agencies such as NASA, over the past few years.

I was rehearsing a presentation that I’m doing soon and decided I might as well record it to share with my subscribers. It was midnight here in Montreal, and I’d been renovating my new home all afternoon, so don’t expect this version to be super high-energy - and my cat insisted on showing up - but after the introduction about who the Stoics were and what they believed, I cover a lot of practical advice, combining Stoicism with cognitive therapy. I think it’s very important material, for self-improvement.

This is accessible only only to you, my Substack subscribers, because it’s some behind-the-scenes work, perhaps best suited for those of you who are already really into Stoicism. There’s also a hidden upload of this video on YouTube. Let me know what you think in the comments.

March 30, 2023

Join us Building the Future of this Community

Dear Stoic fam,

I want to begin by thanking you! In January, this newsletter became one of Substack’s official bestsellers, as a direct result of your support.

However, in some regards the philosophy we love has now become a victim of its own success.

When I was thinking about starting it, I wondered whether it was really needed and what it could accomplish. Way back in Oct 2012, I was invited to a multi-disciplinary workshop, organized by Chris Gill, professor emeritus of Ancient Thought, at Exeter University. We went on to found the Modern Stoicism organization, the Stoic Week online course, and Stoicon conferences. We contributed, I hope, in our small way, to the renaissance in popularity that Stoicism has gone through since then. However, in some regards the philosophy we love has now become a victim of its own success.

Over the years, I noticed more and more articles, videos, podcasts, and books, which seemed to present Stoicism in a very superficial way, or even to badly misrepresent its central ideas. I also watched as the Stoicism communities on social media grew to hundreds of thousands of members but increasingly became dominated by joke memes, and articles about things like how to get rich quick, etc. This seemed very far removed from the Stoic philosophy of Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius. Controversial influencers, such as Andrew Tate and others like him, have jumped on the bandwagon, claiming to be inspired by Stoicism. I noticed that high-quality content from leading experts on the philosophy — like Chris Gill, Massimo Pigliucci, and Chris Gill — was often being drowned out by all the noise on social media.

Not one of my top five recommended resources. Read the Stoics yourself first!

Not one of my top five recommended resources. Read the Stoics yourself first!I learned, though, that Substack was building a space designed to be different. I began to wonder if starting a newsletter might offer a way to create a community where I could help others to put Stoicism and other branches of Greek philosophy into practice, in ways that might help them in daily life.

Since I started writing here, last October, I have been amazed by the conversation we're creating. The conversation is rational and civil. I receive emails almost every week from people telling me how Stoicism has transformed their lives, the lives of their families, and others they care about. We don't have trolls here, we just have a community, based around common interests and values.

Now, I have a request. You are one of the many, highly-engaged people who subscribe to this Substack newsletter with me at no cost to you, for which I'm grateful, because it helps us to spread the word. Thank you! I'd like to ask you to take the next step and become a paid-up subscriber today, for the price of a few cappuccinos ($7 per month or $70 for the whole year).

Although, I write all of the articles myself, reply to all of the comments myself, it takes a small team to keep a community like this alive and thriving.

We try to keep the content fresh, relevant, engaging, and of real practical benefit to you. We’ve been consistently publishing one article every Tuesday, and have added regular podcast episodes. (“Founding” members also get to enroll free of charge on my elearning courses about Marcus Aurelius and Socrates.) Now, to celebrate our growth, I have added a new monthly column titled “Behind the Scrolls”, containing my analysis and commentary on key passages from ancient texts, specifically for paid-up subscribers. It's your paid subscriptions that make this work sustainable.

If Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life has made you think and enriched your life in any way, we would be honored to have you join us as a paid subscriber and community member.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

We’re living in what I like to call the “Third Sophistic”, the modern-era of cyber-Sophists in the form of social media influencers and demagogues! The Internet is awash with divisive political rhetoric, used to provoke fear and anger, in order to manipulate and prey upon the public. Philosophy evolved in ancient Athens precisely as an antidote for the rhetoric of Sophists, the “influencers” of their day. It’s our duty to protect ourselves against those who would exploit us. By learning how to think critically, we can stand on our own two feet, and become more psychologically resilient. This aspect of ancient philosophy reached its pinnacle in the writings of the great Stoic thinkers. The ancient Stoa was a community, first and foremost, where students helped one another to develop their minds, through the use of reason. We can do that again today, cutting through the “smoke and mirrors” and getting back to the basic human virtues — although it does take time and effort.

One final comment… Not everyone who wants to join our community can afford to become a paid subscriber. If that includes you, then please reach out to me directly, and I will do whatever I can to assist you. If that’s not you, though, please consider sponsoring someone else by giving a gift subscription. Substack has a feature, which makes that easy for you, by clicking the button below:

Thank you all, once again, for your support, your questions, and your comments, over the years since I began this journey.

Yours sincerely,

Donald Robertson

March 28, 2023

Announcing: Epictetus Deep-Dive

Starting next Thursday, I’ll be commencing a series of weekly emails based on the Stoic Handbook or Enchiridion of Epictetus. Everyone signed up to my existing newsletter will receive these. (Although you can opt-out if you wish.) I’m calling it the Epictetus Deep-Dive email course because I’ll be discussing each passage in turn, exploring how the Stoic wisdom it contains might be applied in the modern world. It will form the first phase of my new Behind the Scrolls column, exclusively for the paying subscribers among you.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

This sequence will contain original content based upon a revised edition of my earlier “Epictetus Handbook Email Course”, which over six thousand people have completed.

There are 53 passages, which you'll receive one at a time in weekly emails, with my comments underneath. The edition used is the classic 1928 translation by William Abbott Oldfather, which is now in the public domain.

The passages vary considerably in length, from one sentence to several long paragraphs. (So I've split some up further.) The Handbook opens with one of its longest, and most famous passages, which you'll receive via email from my Behind the Scrolls column next Thursday.

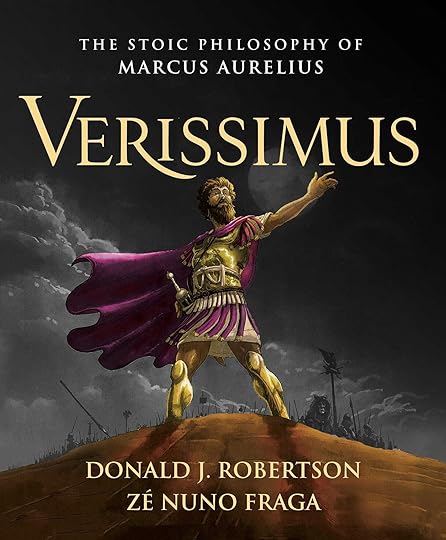

If you're interested in delving even deeper into Stoicism, check out my books How to Think Like a Roman Emperor and Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius.

Thanks for taking part and I hope you enjoy the emails!

Regards,

Donald Robertson

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

March 23, 2023

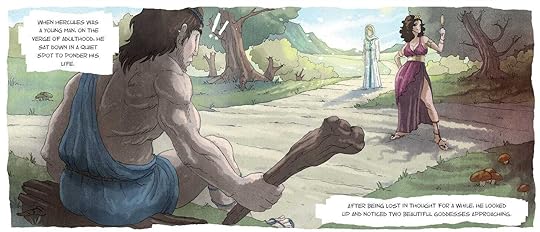

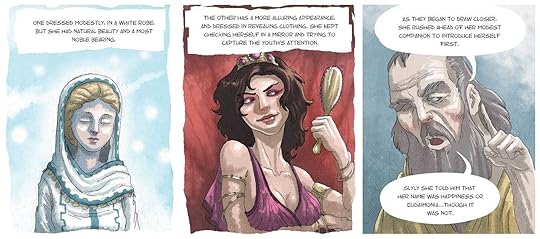

The Choice of Hercules

This is the famous speech, which we’re told inspired Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, to embark on a life of philosophy. He came across it in Book Two of Xenophon’s Memorabilia Socratis, where Socrates is portrayed reciting a version of it, which he learned from the celebrated Sophist and orator, Prodicus. It’s an exhortation to philosophy, which uses the legend of Hercules as an allegory to illustrate the choice between a life of virtue and one of vice. This story was illustrated in our graphic novel, Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Highlights

HighlightsIntroducing the speech

Hercules confronted by the choice between two paths in life

The temptations of Kakia or Vice, to a life of pleasure and idleness

The exhortation of Arete or Virtue, to temperance and endurance

The legacy of the speech and influence on Stoicism

March 21, 2023

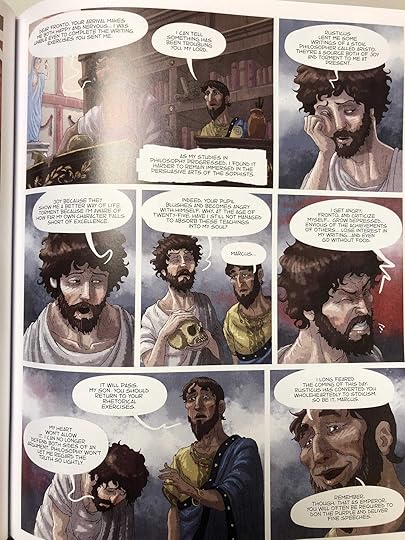

Preface to Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius

Our graphic novel, Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, was released last July, and chosen by Amazon as one of their “best history” editor’s picks. We weren’t sure how it would be received because a comic book aimed at adults, with this amount of history and philosophy, is a relatively unusual idea. Would comic book fans be interested in Stoicism? Would people who read How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, and other Stoicism books, be open to reading a graphic novel? We had to wait and see…

Verissimus is the true story of the last of the Five Good Emperors, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus

Below I’ve included my preface from the book but first here is the feedback from our readers. Verissimus, which is available both in hardback and ebook formats, has now been rated/reviewed nearly 200 times on Amazon. It has a solid 4.8 star rating with “well done”, “great book” and “highly recommend” among the most common phrases used by reviewers, according to Amazon. The most popular review says:

This book takes the disparate sources on Marcus' life and hammers out a portrait of the most relatable soul of pre-Christian antiquity. From Marcus' own words to Herodian and Cassius Dio down to the dodgy Historia Augusta, Robertson has raided the sources and made them make sense.. Robertson also mimics Marcus' style very well. But it is the illustration which really won me over. Ze Nuno Fraga definitely knows Roman architecture, military equipment and ancient fashion. He also knows what the various nationalities neighboring the Romans: Germanics, Parthians, even the Sarmatians are well turned out here. — Doug Welch

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Verissimus also has nearly 200 ratings/reviews on Goodreads, where it has 4.2 stars. The most popular one says:

I solemnly promise not to slip into Gladiator gushing as I review this, never fear, but I'd have to be obtuse to not see that the opening chapter is reminiscent of the film, with Marcus Aurelius up North in the war with the Germans and dying in the presence of his insufferable son, Commodus. But the film is fictional and has numerous historical blunders, whilst Verissimus is the true story of the last of the Five Good Emperors, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus…

Robertson knows the emperor's philosophical thought well, has stayed faithful to the sources and stuck to what's credible, taking very minor creative liberties, about which you can read in the afterword notes… It's a beautiful novel, in my opinion… I appreciated that the artist was as careful with historical accuracy as the writer. The armour, legion formations, architecture, clothing, hairdos, and so on, are well-done without being excessively detailed. I highly recommend it! — Marquise

We can also announce, incidentally, that Brazilian Portuguese will be the first foreign translation available. We’re hopeful that there could also, one day, be a movie or animation based on the book. Below, you can read the whole preface from Verissimus, where I explain how the graphic novel was written and what to expect.

Preface to Verissimus

Preface to VerissimusI’d like to welcome you to the world of Marcus Aurelius, second-century Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher.

The book you are now holding in your hands is the product of nearly twenty-five years of research. While writing my preceding book, How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, I was contacted by a young Portuguese illustrator named Zé Nuno Fraga. Zé showed me some amazing work he’d been doing on a play by Aristophanes. We began experimenting with ideas for illustrations about the life and thought of Marcus Aurelius, and eventually found ourselves at work on a graphic novel for St. Martin’s Press, which acquired the title Verissimus.

A lot of patience was needed to verify the accuracy of the philosophical and historical content of this book, including spending time at the magnificent archaeological park in Carnuntum, and interviewing scholars for our research. I also have to thank our “focus group” of philosophy, comic book, and Roman history enthusiasts for their invaluable feedback on the initial drafts. You’re about to read a truly epic story told in a sweeping cinematic style. As well as Marcus Aurelius the philosopher and statesman, you’ll see him in action as imperator or commander in chief of the Roman legions. However, there’s no way we could have hoped to cover the whole of Marcus’s life and the whole of Stoic philosophy. We had to be selective and focus on specific ideas and events.

This book isn’t intended as an introduction to Stoic philosophy. How to Think Like a Roman Emperor and Stoicism and the Art of Happiness serve that purpose well enough, I hope. Instead, we chose to do something completely new by presenting Marcus’s philosophical precepts and psychological techniques in a more concrete way, placing them within the context of real events from his life. We show how Stoicism influenced some of his decisions as Roman emperor and helped him to cope with the many challenges he faced, in particular the problem of anger and revenge. You’ll find an appendix at the end of this book outlining the main psychological techniques used by Marcus, and indeed by many modern Stoics, for managing anger.

I know some readers are probably unaware of how much historical information we actually possess about the life of Marcus Aurelius. The Roman histories of Cassius Dio, Herodian, and the Historia Augusta are our main sources. We also have fragments of evidence in many other ancient texts, even quotes from Marcus’s rescripts in Roman legislative records, and archeological evidence from monuments, coins, etc. However, it would, of course, be impossible to retell the story of Marcus Aurelius’s life verbatim. There are gaps, ambiguities, and contradictions in the surviving record, as you’d expect. Our goal was to remain as faithful as possible to the historical evidence while also engaging the reader in an exciting story and teaching them some valuable things about Stoicism along the way.

Where there’s information in our sources that seemed dubious or contradictory, we employed the device of presenting it in differently-shaped panels, denoting the character’s imagination, or as gossip, to place its reliability more obviously in question. See also the notes at the end of this book for some examples of decisions that were made regarding notable historical controversies. However, we don’t expect you to read this book as a conventional biography or a philosophy textbook... No, this is a “ripping yarn” about a great man’s philosophical, psychological, and spiritual journey.

My main goal in writing Verissimus was to help you... I want Marcus’s story to bring his philosophy to life for those finding out about it for the first time. I also want to give those familiar with Stoicism a new perspective on some of its main teachings and practices. I hope it inspires you to learn more about Marcus’s life and the philosophy of Stoicism, perhaps by reading Meditations, if you haven’t already done so. Fate permitting, some of you will find that the remarkable story of Marcus’s personal challenges resonates very deeply with you.

May it even help liberate you from the grip of anger and the other toxic passions against which Stoics waged their inner war.

Donald Robertson, Athens, Greece

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

March 16, 2023

Your PDF Stoic Therapy Toolkit

If you’re a paid subscriber, you will be able to download and share with your friends. This is a five-page PDF guide, called the Stoic Therapy Toolkit, designed to help provide a neat summary of the most important Stoic psychological practices.

Very useful summary, I will carry it in my work bag! – Camelia Vasilov

Excellent! Thank you for your tireless work in making this valuable philosophy so accessible in our busy world. – Deborah L Gariepy

I've been asked many times for a Stoic "cheat sheet" or summary of key ideas and practical techniques. So I decided to create one based on my books on Stoicism: The Philosophy of CBT (2010), Build your Resilience (2012) and Stoicism and the Art of Happiness (2013). Thanks to all the individuals who provided feedback and suggestions based on the draft. We're confident now that this provides a good summary of key points, which most people will find beneficial.

Thank so much, Donald! It's awesome to see how hard you work – for all of us! – Michael van der Galien

This printable PDF document will give you a good overview of Stoicism, and a reminder of daily practices. Many people contributed to the wording and Rocio de Torres, our graphic designer, has given it a new look. So we're confident you'll appreciate the end result and find it valuable as a guide to living like a Stoic.

Contents

ContentsIntroduction

The Goal of Virtue

Daily Routine

Four Stoic Meditations

Therapy of the Passions

If you're completely new to Stoicism, it's a good place to start. However, we can't compress the whole philosophy into a few pages, it's just a summary, so you will need to read the Stoics to gain a more complete understanding of their concepts and techniques. The download link is available below to all paid subscribers.

March 14, 2023

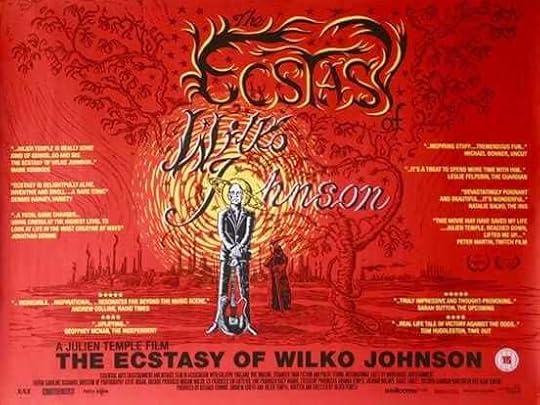

The Greatest Documentary on Stoicism?

This question comes up a lot and I don't think there's a good answer. There's not really a movie explicitly about ancient Stoicism, although there are a few passing references in Gladiator and John Malkovich has a movie coming out soon about Seneca. There are a few others worth mentioning but to be honest, I really think The Ecstasy of Wilko Johnson is the best thing to watch if you're serious about looking for a load of Stoic-related ideas in a movie.

Wilko was the guitarist in the seminal blues rock band Dr. Feelgood, who inspired many early punk bands. He also, later in life, played an executioner in Game of Thrones. About eight years ago, Wilko was told he was dying of pancreatic cancer and had 10 months to live, and he says the certainty of his own impending death was liberating and filled him with a strange euphoria. He had been an English teacher and his love of Shakespeare and Milton, etc., helped him to process coming to terms with his own mortality.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Julien Temple made this great documentary, The Ecstasy of Wilko Johnson, which basically allowed Wilko to quote Hamlet and Paradise Lost a lot, while reflecting on his own mortality. He never mentions Stoicism but there are many quotes such as "What cannot be cured must be endured", which he's drawing from English classics obviously inspired by Stoicism. (I think from Robert Burton's Anatomy of Melancholia.)

Wilko, to his surprise, later found out that his cancer was operable, so after some brutal surgery, he lived about another eight years, but sadly passed away not long ago, which inspired me to watch his documentary again. I think anyone who's really into Stoicism and classics would enjoy it. It's a very deep dive into one man's reflections on his own impending death and how this realization potentially liberated him in many ways.

The whole thing seems to be available on YouTube:

Also worth checking out, Going Back Home, the album he recorded with Roger Daltrey of The Who, when he believed he was dying., although I don't think the songs really cover themes about mortality, etc.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

March 9, 2023

Stoicism, Cognitive Therapy, and Resilience

In this episode, I answer questions about Stoicism, cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), and emotional-resilience from Valentin Lehodey, a digital journalism student at the University of Strathclyde in Scotland.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

HighlightsWhat is Stoicism?

How Stoicism influenced cognitive therapy

Stoicism as a preventative resilience-building approach

How Stoicism goes beyond modern psychotherapy

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

March 7, 2023

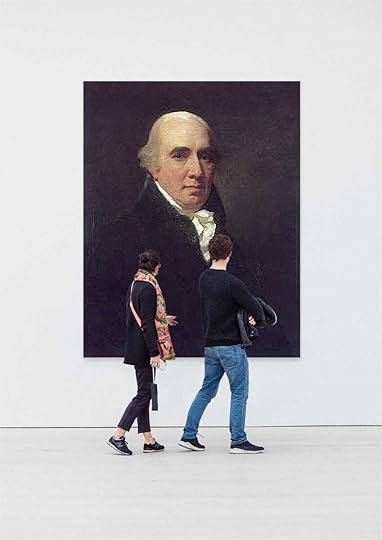

Stoicism and Scottish Philosophy

Dugald Stewart (1753-1828) was professor of moral philosophy at Edinburgh University, and a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS). He was part of the movement in academic philosophy known as Scottish Common Sense Realism. Stewart was also good friends with Scotland's national bard, the poet Robert Burns.

Much of intellectual life in eighteenth-century Scotland is marked by the phenomenon nowadays called the "Scottish Enlightenment" – a flourishing exchange of ideas in a quite remarkably tolerant public space… Scotland before the Enlightenment was not devoid of interest in classical antiquity, yet during the eighteenth century one can identify an increased interest in Greek and Latin authors – particularly in the Stoics and Cicero... – Christian Maurer, 'Stoicism and the Scottish Enlightenment' in the Routledge Handbook of the Stoic Tradition (2016) edited by John Sellars

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Stewart was one of the Scottish Enlightenment philosophers most interested in ancient Stoicism and provides a very insightful summary of its doctrines in the following excerpt from his book The Philosophy of the Active and Moral Powers of Man (1829), Book 4, Chapter 4, Section 2. I've made light editorial changes to the content, such as updating some anachronistic spellings and reformatting his extensive quotations from other authors, such as James Harris and fellow Scots Adam Smith and Adam Ferguson. Thanks to Colin Hay of The Scottish Stoics for help preparing the text. – Donald Robertson

Of Happiness. Systems of the Grecian Schools on the Subject.

Of Happiness. Systems of the Grecian Schools on the Subject.In opposition to the Epicurean doctrines on the subject of happiness, the Stoics placed the supreme good in rectitude of conduct, without any regard to the event. They did not, however, as has been often supposed, recommend an indifference to external objects, or a life of inactivity and apathy. On the contrary, they taught that nature pointed out to us certain objects of choice and of rejection, and amongst these some to be more chosen and avoided than others; and that virtue consisted in choosing and rejecting objects according to their intrinsic value. They admitted that health was to be preferred to sickness, riches to poverty; the prosperity of our family, of our friends, of our country, to their adversity; and they allowed, nay, they recommended, the most strenuous exertions to accomplish these desirable ends. They only contended these objects should be pursued not as the constituents of our happiness, but because we believe it to be agreeable to nature that we should pursue them; and that, therefore, when we have done our utmost, we should regard the event as indifferent.

…the Stoics, in the character of their virtuous man, included rational desire, aversion, and exultation; included love and parental affection, friendship, and a general benevolence to all mankind.

That this is a fair representation of the Stoic doctrine has been fully proved by Mr. James Harris in the very learned and judicious notes on his Dialogue concerning Happiness; a performance which, although not entirely free from Mr. Harris's peculiarities of thought and style, does him so much honour, both as a writer and a moralist, that we cannot help regretting, while we peruse it, that he should so often have wasted his ingenuity and learning upon scholastic subtleties, equally inapplicable to the pursuits of science, and to the business of life. Harris observes:

The word παθος [pathos], which we usually render a passion, means, in the Stoic sense, a perturbation, and is always so translated by Cicero; and the epithet απαθης [apathes], when applied to the wise man, does not mean an exemption from passion, but an exemption from that perturbation which is founded on erroneous opinions. The testimony of Epictetus is express to this purpose. I am not, says he, to be apathetic like a statue, but I am withal to observe relations both the natural and adventitious; as the man of religion, as the son, as the brother, as the father, as the citizen. And immediately before he tells us, that a perturbation in no other way ever arises but either when a desire is frustrated, or an aversion falls into that which it should avoid. In which passage it is observable that he does not make either desire, or aversion, παθη [pathe], or perturbations, but only the cause of perturbations when erroneously conducted. – Harris, Dialogue Concerning Happiness

From a great variety of passages, which it is unnecessary for me to transcribe, Harris concludes that "the Stoics, in the character of their virtuous man, included rational desire, aversion, and exultation; included love and parental affection, friendship, and a general benevolence to all mankind; and considered it as a duty arising from our very nature not to neglect the welfare of public society, but to be ever ready, according to our rank, to act as either the magistrate or as the private citizen."

Nor did they exclude wealth from among the objects of choice. The Stoic Hecato, in his Treatise of Offices, quoted by Cicero, tells us,

That a wise man, while he abstains from doing anything contrary to the customs, laws, and institutions of his country, ought to attend to his own fortune. For we do not desire to be rich for ourselves only, but for our children, relations, and friends, and especially for the commonwealth, inasmuch as the riches of individuals are the wealth of a state. – Cicero, De Officiis, iii.15

"Nay," says Cicero, "if the wise man could mend his condition by adding to the amplest possessions the poorest, meanest utensil, he would in no degree condemn it." [De Finibus, iv.12]

From these quotations it sufficiently appears that the Stoic system, so far from withdrawing men from the duties of life, was eminently favourable to active virtue. Its peculiar and distinguishing tenet was, that our happiness did not depend on the attainment of the objects of our choice, but on the part that we acted; but this principle was inculcated not to damp our exertions, but to lead us to rest our happiness only on circumstances which we ourselves could command. Says Epictetus:

If I am going to sail, I choose the best ship and the best pilot, and I wait for the fairest weather, that my circumstances and duty will allow. Prudence and propriety, the principles which the gods have given me for the direction of my conduct, require this of me, but they require no more; and if, notwithstanding, a storm arises, which neither the strength of the vessel nor the skill of the pilot are likely to with stand, I give myself no trouble, about the consequences. All that I had to do is done already. The directors of my conduct never command me to be miserable, to be anxious, desponding, or afraid. Whether we are to be drowned or come to a harbour is the business of Jupiter, not mine. I leave it entirely to his determination, nor ever break my rest with considering which way he is likely to decide it but receive whatever comes with equal indifference and security. – Epictetus, Smith's translation from Theory of Moral Sentiments

We may observe further, in favour of this noble system, that the scale of desirable objects which it exhibited was peculiarly calculated to encourage the social virtues. It represented indeed (in common with the theory of Epicurus) self-love as the great spring of human actions; but in the application of this erroneous principle to practice, its doctrines were favourable to the most enlarged, nay, to the most disinterested benevolence. It taught that the prosperity of two was preferable to that of one; that of a city to that of a family; and that of our country to all partial considerations. It was up on this very principle, added to a sublime sentiment of piety, that it founded its chief argument for an entire resignation to the dispensations of Providence. As all events are ordered by perfect wisdom and goodness, the Stoics concluded, that whatever happens is calculated to produce the greatest good possible to the universe in general. As it is agreeable to nature, therefore, that we should prefer the happiness of many to a few, and of all to that of many, they concluded that every event which happens is precisely that which we ourselves would have desired, if we had been acquainted with the whole scheme of the Divine administration.

In what sense are some things said to be according to our nature, and others contrary to it? It is in that sense in which we consider ourselves as separated and detached from all other things. For thus it may be said to be the nature of the foot to be always clean. But if you consider it as a foot, and not as something detached from the rest of the body, it must behove it sometimes to trample in the dirt, and sometimes to tread upon thorns, and sometimes, too, to be cut off for the sake of the whole body; and if it refuses this, it is no longer a foot. Thus, too, ought we to conceive with respect to ourselves. What are you? A man. If you consider yourself as something separated and detached, it is agreeable to your nature to live to old age, to be rich, to be in health. But if you consider yourself as a man, and as a part of the whole, upon account of that whole it will behove you sometimes to be in sick ness, sometimes to be exposed to the inconvenience of a sea voyage, sometimes to be in want, and at last perhaps to die before your time. Why then do you complain? Don't you know that by doing so, as the foot ceases to be a foot, so you cease to be a man. – Epictetus

And as Marcus Aurelius Antoninus writes:

Oh world, all things are suitable to me which are suitable to thee. Nothing is too early or too late for me which is seasonable for thee. All is fruit to me which thy seasons bring forth. From thee are all things; in thee are all things; for thee are all things. Shall any man say, O beloved city of Cecrops! and wilt not thou say, O beloved city of God! – Smith's translation from Theory of Moral Sentiments

In this tendency of the Stoic philosophy to encourage the active and social virtues, it was most remarkably distinguished from the system of Epicurus. The latter, indeed, seems (as it was first taught) to have been the reverse of that system of sensuality and of libertinism, to which the epithet Epicurean is commonly applied in modern times; but it was at best a system of selfishness and prudent indulgence, which placed happiness in a seclusion from care, and in an indifference to all the concerns of mankind. By the Stoics, on the contrary, virtue was supposed to consist in the affectionate performance of every good office towards their fellow creatures, and in full resignation to Providence for everything independent of their own choice.

It is remarked by Dr. Adam Ferguson that:

Their different schemes of theology clearly pointed out their opposite plans of morality also. Both admitted the existence of God. But to one the Deity was a retired essence enjoying itself, and far removed from any work of creation and Providence.

The other considered the Deity as the principle of existence and of order in the universe, from whom all intelligence proceeds, and to whom all intelligence will return; whose power is the irresistible energy of wisdom and of goodness, ever present and ever active; bestowing on man the faculty of reason and the freedom of choice, that he may learn, in acting for the general good, to imitate the Divine nature; and that, in respect of events independent of his will, he may acquiesce in the determination of Providence.

In conformity with these principles one sect recommended seclusion from all the cares of family or state. The other recommended an active part in all the concerns of our fellow creatures, and the steady exertion of a mind benevolent, courageous, and temperate. Here the sects essentially differed, not in words, as has sometimes been alleged, but in the views which they entertained of a plan for the conduct of human life. The Epicurean was a deserter from the cause of his fellow creatures and might justly be reckoned a traitor to the community of nature, of mankind, and even of his country.

The Stoic enlisted himself as a willing instrument in the hand of God for the good of his fellow creatures. For himself, the cares and attentions which this object required were his pleasures, and the continued exertion of a beneficent affection, his welfare and his prosperity. – Ferguson, Principles of Moral and Political Science

Such was the philosophy of the Stoics; — "a philosophy," says Mr. Smith, "which affords the noblest lessons of magnanimity, is the best school of heroes and patriots; and to the greater part of whose precepts there can be no other objection but this honourable one, that they teach us to aim at a perfection altogether beyond the reach of human nature."

I cannot however help remarking, that this is by no means an objection to their system; for it is the business of the moralist to exhibit a standard far above the reach of our possible attainments. If he did otherwise, he must recommend errors and imperfections. Speaking of eloquence and the fine arts – and the observation holds equally with respect to every other pursuit – Quintilian says:

It has sometimes happened that great things have been accomplished by him who was striving at what was above his power. – Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria, ii.12

To the same purpose it is well said by Seneca:

It is the mark of a generous spirit to aim at what is lofty; to attempt what is arduous; and ever to keep in view what it is impossible for the most splendid talents to accomplish. – Seneca, De Vita Beata, c.20

The Stoics themselves were sensible of the weakness inseparable from humanity. Cicero, speaking the language of a Stoic, says:

Neither indeed, when the two Decii or the two Scipios are mentioned as brave men, nor when Aristides or Fabricius are denominated just, is an example of fortitude in the former, or of justice in the latter, proposed as exactly conformable to the precepts of wisdom. For none of them were wise in that sense in which we apply the epithet to the wise man. Nor were Cato and Laelius such, although they were honoured with the appellation. No, not even the seven wise men of Greece who have been so widely celebrated, although, from the habitual discharge of middle duties, (ex mediorum officiorum frequentid) all of them bore a certain similitude to the ideal character. – Cicero, De Officiis, L.iii, c.4

Seneca also mentions it as a general confession of the greatest philosophers, that the doctrine they taught was not "quemadmodum ipsi viverent, sed quemadmodum vivendum est." ["even as they themselves were living, but as I have to live"] [De Vita Beata, c.18]

I know that I shall not be Milo, and yet I neglect not my body; nor Croesus, and yet I neglect not my estate; nor in general do we desist from the proper care of anything through despair of arriving at what is supreme. – Epictetus, Discourses, L.i, c.2

In the writings indeed of some of the Stoics, we meet with some absurd and violent paradoxes about the perfect felicity of the wise man on the one hand, and the equality of misery among all those who fall short of this ideal character on the other.

As all the actions of the wise man were perfect, so all those of the man who had not arrived at this supreme wisdom were faulty and equally faulty. As one truth could not be more true, nor one falsehood more false than another, so an honourable action could not be more honourable, nor a shameful one more shameful than another. As in shooting at a mark, the man who had missed it by an inch had equally missed it with him who had done so by an hundred yards, so the man who, in what appears to us the most insignificant action, had acted improperly, and without a sufficient reason, was equally faulty with him who had done so in what appears to us the most important; the man who has killed a cock (for example) improperly, and without a sufficient reason, with him who had murdered his father.

Mr Smith continues,

It is not, however, by any means probable that these paradoxes formed a part of the original principles of Stoicism, as taught by Zeno and Cleanthes. It is much more probable that they were added to it by their disciple, Chrysippus, whose genius seems to have been more fitted for systematizing the doctrines of his preceptors, and adorning them with the imposing appendages of artificial definitions and divisions, than for imbibing the sublime spirit which they breathed. Such a man may very easily be supposed to have understood too literally some animated and exaggerated expressions of his masters in describing the happiness of the man of perfect virtue, and the unhappiness of whoever fell short of that character.

That these paradoxes were not adopted by the most rational admirers of the Stoic philosophy we have complete evidence; for we find them treating expressly of those imperfect virtues which are attained by inferior proficients in wisdom, and which they did not dignify with the name of rectitudes, but distinguished by the epithets of proper, fit, and decent.

Such virtues are called by Cicero officia, and by Seneca convenientia. They are treated of by Cicero in his Offices and are said to have been the subject of a book (now lost) by Marcus Brutus.

This apology, however, it must be confessed, will not extend to all the errors of the Stoic school. In particular, it will not extend to the notions it included on the subject of suicide. But for these errors, if it is impossible to apologize, we may at least account in some measure, by the peculiar circumstances of the times when this philosophy arose, and which infected with the same spirit, though perhaps not in an equal degree, the peaceable and indolent followers of Epicurus. Says Mr. Smith:

During the age in which flourished the founders of all the principal sects of ancient philosophy — during the Peloponnesian war, and for many ages after its conclusion — all the different republics of Greece were at home almost always distracted by the most furious factions, and abroad involved in the most sanguinary wars, in which each sought not merely superiority or dominion, but either completely to extirpate all its enemies, or, what was not less cruel, to reduce them into the vilest of all states — that of domestic slavery. The smallness of the greater part of those states, too, rendered it to each of them no very improbable event, that it might itself fall into that very calamity which it had so frequently inflicted or attempted to inflict on its neighbours.

In this disorderly state of things the most perfect innocence, joined to the highest rank and the greatest services to the public, could give no security to any man, that even at home and among his fellow citizens, he was not, at some time or other, from the prevalence of some hostile and furious faction, to be condemned to the most cruel and ignominious punishment. If he was taken prisoner of war, or if the city of which he was a member was conquered, he was exposed, if possible, to still greater injuries.

As an American savage, therefore, prepares his death song, and considers how he should act when he has fallen into the hands of his enemies, and is by them put to death in the most lingering tortures, and amidst the insults and derisions of all the spectators, so a Grecian patriot or hero could not avoid frequently employing his thoughts in considering what he ought both to suffer and to do in banishment, in captivity, when reduced to slavery, when put to the torture, when brought to the scaffold. It was the business of their philosophers to prepare the death song which the Grecian patriots and heroes might make use of on the proper occasions; and of all the different sects it must, I think, be acknowledged, that the Stoics had prepared by far the most animated and spirited song. – Smith, Theory of Moral Sentiments

After all, it is impossible to deny that there is some foundation for a censure which Lord Bacon has some where passed on this celebrated sect. "Certainly," says he, "the Stoics bestowed too much cost on death, and by their preparations made it more fearful." At least, I suspect this may be the tendency of some passages in their writings, in such a state of society as that in which we live; but in perusing them we ought always to remember the circumstances of those men to whom they were addressed, and which are so eloquently described in the observations just quoted from Mr. Smith. The practical reflection which Francis Bacon adds to this censure is invaluable and is strictly conformable to the spirit of the Stoic system, although he seems to state it by way of contrast to their principles. He says,

It is as natural to die as to be born; and to a little infant perhaps the one is as painful as the other. He that dies in an earnest pursuit is like one that is wounded in hot blood, who for a time scarce feels the hurt; and therefore, a mind fixed and bent upon somewhat that is good doth best avert the dolors of death. – Bacon, Essays

Upon the whole, notwithstanding the imperfections of this system, and the paradoxes which disgrace it in some accounts of it that have descended to our times, it cannot be disputed, that its leading doctrines are agreeable to the purest principles of morality and religion. Indeed, they all terminate in one maxim: That we should not make the attainment of things external an ultimate object but place the business of life in doing our duty and leave the care of our happiness to him who made us. Nor does the whole merit of these doctrines consist in their purity. It is doing them no more than justice to say, that they were more completely systematic in all their parts, and more ingeniously, as well as eloquently, supported, than anything else that remains of ancient philosophy.

I must not conclude these observations on the Stoic system, without taking notice of the practical effects it produced on the characters of many of its professors. It was the precepts of this school which rendered the supreme power in the hands of Marcus Aurelius a blessing to the human race; and which secured the private happiness and elevated the minds of Helvidius and Thrasea under a tyranny by which their country was oppressed. Nor must it be forgotten, that in the last struggles of Roman liberty, while the school of Epicurus produced Caesar, that of Zeno produced Cato and Brutus. The one sacrificed mankind to himself; the others sacrificed themselves to mankind.

Hi mores, hsec duri immota Catonis

Secta fuit, servare modum, finemque tenere,

Naturamque sequi, patriaeque impendere vitam;

Nec sibi, sed toti genitum se credere mundo.

[This was the character and this the unswerving creed

of austere Cato: to observe moderation, to hold to the goal,

to follow nature, to devote his life to his country,

to believe that he was born not for himself but for all the world.]

– Lucan, Pharsalia, Lib. ii. 1. 380

The sentiment of President Montesquieu on this subject is well known.

Never, were any principles more worthy of human nature, and more proper to form the good citizen, than those of the Stoics; and if I could for a moment cease to recollect that I am a Christian, I should not be able to hinder myself from ranking the destruction of the sect of Zeno among the misfortunes that have befallen the human race.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.