Alexander the Great and Stoicism

Hellenism he spread far and wide

The Macedonian learned mind

Their culture was a western way of life

He paved the way for Christianity. – Iron Maiden, Alexander the Great

It might seem like a surprising claim but, according to Plutarch, Alexander the Great was not only a true philosopher but also paved the way for the ethical “cosmopolitanism” of Hellenistic philosophy, particularly Stoicism, by founding an empire based on the principle that all humans, regardless of their native race or tribe, could, in some sense, be viewed as fellow-citizens of a single world community. This idea arguably laid the foundations for the Christian doctrine, three centuries later, of a brotherhood of man, and the virtue of brotherly love or philadelphia.

Plutarch was himself a philosopher of the Academic school, and also a priest at the famous Temple of Apollo in Delphi. Although was born in the middle of the 1st century CE, nearly four centuries after the death of Alexander, he is one of our main sources of information on the life of the famous King of Macedonia and conqueror of Persia. In addition to his biography of Alexander, in Parallel Lives, though, Plutarch wrote a less well-known essay titled On the fortune or the excellence of Alexander.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The explicit purpose of Plutarch’s essay is to argue that whereas many other rulers had benefited from good fortune, being born into great wealth and power, Alexander conquered a vast empire starting with relatively humble resources. In his early days, as a young prince of Macedonia, it would have been difficult to imagine how he could hope to defeat the might of Darius III, the Great King of Persia. Alexander’s extraordinary achievements, claims Plutarch, must therefore be attributed not primarily to good fortune but to his exceptional strength of character, or arete, meaning virtue or excellence.

Marcus Aurelius lumps Alexander together with famous military leaders… who are nevertheless viewed with disdain by philosophers.

Stoic Criticisms of AlexanderAlthough Alexander was certainly widely revered for his military achievements, some philosophers considered him to have been the opposite of a wise and virtuous ruler. Marcus Aurelius, for instance, lumps Alexander together with Julius Caesar, and his rival Pompey the Great, as examples of famous military leaders, who are nevertheless viewed with disdain by philosophers. For instance, he says that Alexander, and the other two, “often razed whole cities to the ground and slaughtered tens of thousands of horsemen and foot-soldiers on the battlefield.” Nevertheless, he adds, “there came a day when they too departed from this life” (Meditations, 3.3).

Indeed, “Alexander the Great and his stable boy were brought to the same level in death”, either dissolved back into the unity of Zeus or perhaps dispersed among random atoms (Meditations, 6.24). The achievements of these rulers impress ordinary people but they’re of little importance in the grand scheme of things. Though remembered for many centuries, they will one day be forgotten. “Go on, then, and talk to me of Alexander,” says Marcus, and of other celebrated rulers.

If they saw what universal nature wishes and trained themselves accordingly, I will follow them; but if they merely strutted around like stage heroes, no one has condemned me to imitate them. The work of philosophy is simple and modest; do not seduce me into vain ostentation. (Meditations, 9.29)

The great philosophers, says Marcus, were in control of their own minds, understood life properly, and distinguished between events and their causes. Wisdom, in other words, is more important than glory.

As for the great military leaders of history, he says, “consider how many cares they had and to how many things they were enslaved!” Although they were, in their times, the most powerful men in the world, Alexander, and others like him, were enslaved by their own passions, such as the craving for glory. They lacked insight into their own minds and therefore they lacked self-control. “What are Alexander, Julius Caesar, and Pompey when compared to Diogenes the Cynic, Heraclitus, and Socrates?”, he exclaims (Meditations, 8.3).

Alexander the “Philosopher”Plutarch, by contrast, actually argues that Alexander owed his greatness to philosophy. In On the fortune or the excellence of Alexander, he says that Aristotle, Alexander’s tutor, provided him with greatness of soul, quick thinking, temperance, and courage. Alexander, he claims, owed his success more to the education he had received from Aristotle than to the wealth and resources he was fortunate enough to have inherited from his father, Philip, the King of Macedonia.

Plutarch even goes so far as to insist that Alexander was himself, in a sense, a philosopher.

Plutarch even goes so far as to insist that Alexander was himself, in a sense, a philosopher. Some, he concedes, may object that Alexander never discoursed on philosophy at the Lyceum or Academy, and that he wrote nothing on the subject, and did not bring philosophical treatises with him to study on campaign, about “Fearlessness and Courage, and Temperance also, and Greatness of Soul”. “For it is by these criteria”, sniffs Plutarch, “that those define philosophy who regard it as a theoretical rather than a practical pursuit.”

However, he points out that Pythagoras, Socrates, and many other great philosophers did not leave behind writings of their own, and that true philosophers are judged not by their theoretical scholarship, or writings, but by their own lives, and the principles they espoused, and taught others. “By these criteria let Alexander also be judged!”, he says, confidently asserting that “from his words, from his deeds, and from the instruction which he imparted,” it will be evident, surprising though it may sound, that Alexander was indeed a philosopher.

Plutarch notes that whereas Socrates struggled to improve some of his wayward students, such as Critias and Alcibiades, although they were educated native Athenians, Alexander, by contrast, succeeded in bringing Greek culture and civilization to countless “barbarian” tribes throughout Asia, even persuading “the Indians to worship Greek gods”. Alexander was, therefore, he notes, far more successful than Socrates at spreading enlightenment, based on Greek culture and wisdom, to a larger number of people.

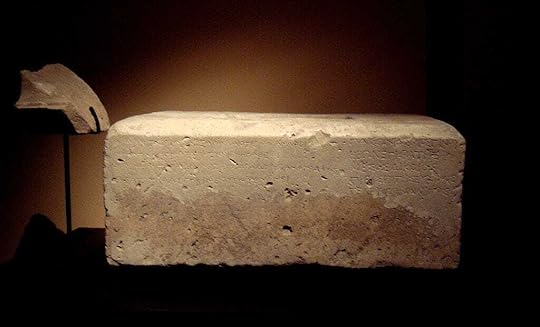

Greek inscription of some Delphic maxims from 2nd century BCE, found at Al-Khanoum in modern-day Afghanistan.

Greek inscription of some Delphic maxims from 2nd century BCE, found at Al-Khanoum in modern-day Afghanistan. Likewise, whereas Plato wrote books on politics, laws, and the ideal Republic, he was unable to convince anyone to establish a society based upon them. Alexander, by contrast, says Plutarch, “established more than seventy cities among savage tribes and sowed all Asia with Grecian magistracies, and thus overcame its uncivilised and brutish manner of living.”

Although few of us read Plato's Laws, yet hundreds of thousands have made use of Alexander's laws, and continue to use them.

Indeed, he makes the striking claim that those “who were vanquished by Alexander are happier than those who escaped his hand”. This remark seems quite presumptuous, and overtly-colonialist, but Plutarch feels it is justified because so many major cities that had once formed part of Alexander’s empire still embraced Hellenism, and continued to flourish, more than four centuries after his demise. Alexander, he argues, spread Greek civilization throughout the known world, establishing the institutions that would preserve wisdom and justice more effectively than any philosopher. The great library at Alexandria, in Egypt, founded by his successor, Ptolemy, would eventually become one of the most famous seats of learning in European history.

If, then, philosophers take the greatest pride in civilizing and rendering adaptable the intractable and untutored elements in human character, and if Alexander has been shown to have changed the savage natures of countless tribes, it is with good reason that he should be regarded as a very great philosopher.

The term “Hellenization” refers to this adoption of Greek culture and language by non-Greek (“barbarian”) people, which typically resulted in a hybrid of cultures, as in the Hellenization of Egypt. After the death of Alexander, though his empire fragmented, into several kingdoms ruled by his generals, the spread of Hellenism continued in this way, but it also began to influence a new wave of emerging philosophical systems, including Stoicism.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Alexander and StoicismZeno, the founder of Stoicism, was a Hellenized, Greek-speaking, Phoenician merchant, from Cyprus, who arrived at Athens a few years after the demise of Alexander the Great. Zeno studied several of the schools of philosophy at Athens before, in 301 BCE, founding his own school, which came to be known as the Stoa after the Stoa Poikile, a painted porch in the Athenian Agora where his followers gathered. Zeno was known, at first, as a follower of the Cynic philosophy, and the first book he wrote was the heavily Cynic-influenced Republic, a critique of Plato’s treatise, of the same name, on justice, and the ideal state. (Our sources also refer to a text attributed to Diogenes, the founder of Cynicism, titled the Republic, which appears closely related to, or was perhaps even confused with, the book by Zeno.)

Plutarch, a follower of the rival Academic school, drew inspiration from the Stoics but was, at times, also very critical of them. However, in On the fortune or the excellence of Alexander, he claims that the political ideals of Zeno, and the early Stoics, had already been implemented, in practice, by Alexander.

Moreover, the much-admired Republic of Zeno, the founder of the Stoic sect, may be summed up in this one main principle: that all the inhabitants of this world of ours should not live differentiated by their respective rules of justice into separate cities and communities, but that we should consider all men to be of one community and one polity, and that we should have a common life and an order common to us all, even as a herd that feeds together and shares the pasturage of a common field. This Zeno wrote, giving shape to a dream or, as it were, shadowy picture of a well-ordered and philosophic commonwealth; but it was Alexander who gave effect to the idea.

Plutarch’s calls this Zeno’s “dream”, implying that it was a Utopian vision. He says that Alexander was the one, a generation earlier, who had first made this a political reality, though. Plutarch can be read as implying that it was actually the cosmopolitanism of Alexander’s empire, in other words, that paved the way for Zeno’s vision of an ideal Stoic Republic.

Alexander, he says, totally rejected the advice of his teacher, Aristotle, “to treat the Greeks as if he were their leader, and other peoples as if he were their master”, or a tyrant. The Macedonian philosopher had told his king, allegedly, to view only their fellow Greeks as friends and kin, but to treat “barbarian” races, such as the Persians, “as though they were plants or animals”, something less than human. Once Alexander found himself controlling most of the former Persian empire, though, he realized it would be impractical to follow this advice. Treating the “barbarian” tribes that surrounded him as inferior to his Macedonian troops would have bogged Alexander down in ethnic conflict, festering rebellions, and other needless obstacles. He had to turn the local population into his allies.

Alexander saw his divinely-assigned role as being a “common moderator and arbiter of all nations”, although he conquered by force those who would not join his empire voluntarily. Nevertheless, he succeeded in bringing together countless foreign tribes, far and wide, under a single dominion. Uniting and mixing, as though in one great “festival cup”, as Plutarch puts it, men’s lives, culture, marriages, and customs. The inhabitants of Alexander’s new empire were to view themselves as citizens of the whole world, with his military camp, wherever it may be, serving as their capital city.

He bade them all consider as their fatherland the whole inhabited earth, as their stronghold and protection his camp, as akin to them all good men, and as foreigners only the wicked.

They were no longer to distinguish Greeks, with their cloaks and shields, from “barbarians” with their scimitars and long-sleeved jackets. Rather, said Alexander, a man should be called a Greek if he is an ally, and virtuous, and a “barbarian”, only if he is vicious and an enemy. There would, in other words, be no distinction based on race, but a fellow-countryman could be anyone who behaved like a friend. Clothing and food, says Plutarch, marriage and customs, were to be regarded as common, “blended into one by ties of blood and children”, as his men were encouraged to marry native women.

Plutarch says that Xerxes, the Great King of Persia, seems foolish, in retrospect, for expending so much time on military efforts to invade Greece and extend his kingdom across the Hellespont, from Asia into Europe. Alexander finally managed to unite Greece and Persia by holding a joint wedding ceremony for a hundred couples, Persian brides and Macedonian soldiers, and thereby “bridged the Hellespont”, not with lifeless rafts, but by creating genuine blood ties between their people, lasting for generations.

Plutarch claims that Alexander himself adopted a form of dress combining elements of both Persian and Macedonian styles, in order to show respect for the culture of the region in which he had established his camp. “As a philosopher what he wore was a matter of indifference,” says Plutarch. He even says that it is the “mark of an unwise and vainglorious mind” to prefer a plain robe of uniform color, such as those traditionally worn by Cynics and Stoics, and to be displeased by a tunic with a purple border, the regal color, which philosophers typically held up as an emblem of vanity and self-aggrandizement. Plutarch complains that some critics “impeach Alexander because, although paying due respect to his own national dress, he did not disdain that of his conquered subjects in establishing the beginnings of a vast empire.”

Moreover, Alexander did not, he says, typically loot the countries that he conquered, like other rulers, but rather he “desired to render all upon earth subject to one law of reason and one form of government and to reveal all men as one people, and to this purpose he made himself conform.”

Therefore, in the first place, the very plan and design of Alexander's expedition commends the man as a philosopher in his purpose not to win for himself luxury and extravagant living, but to win for all men concord and peace and community of interests.

If Alexander had not died young, says Plutarch, “one law would govern all mankind, and they all would look toward one rule of justice as though toward a common source of light.” He concludes that Alexander was a philosopher, first and foremost, because of his cosmopolitan vision for society.

Alexander’s Words and DeedsIn the second place, though, according to Plutarch, Alexander was also shown to be a true philosopher, by certain sayings, and actions, which revealed his character as virtuous and magnanimous.

Are not these the words of a truly philosophic spirit which, because of its rapture for noble things, already revolts against mere physical encumbrances?

When, according to legend, Alexander met Diogenes the Cynic in Corinth, he came away so impressed that thereafter he frequently said, “If I were not Alexander,I should be Diogenes.” “Thus it is the mark of a truly philosophic soul to be in love with wisdom and to admire wise men most of all,” says Plutarch, “and this was more characteristic of Alexander than of any other king.”

[Alexander] confirms the truth of that principle of the Stoics which declares that every act which the wise man performs is an activity in accord with every virtue. — Plutarch

Plutarch says that this is demonstrated by Alexander’s respect for Aristotle, that he was a patron of the Skeptic philosopher, Pyrrho of Elis, and of Xenocrates the Academic, and that he allegedly made Onesicritus, the Cynic, a follower of Diogenes, the chief pilot of his fleet.

For, by Heaven, it is impossible for me to distinguish his several actions and say that this betokens his courage, this his humanity, this his self-control, but everything he did seems the combined product of all the virtues; for he confirms the truth of that principle of the Stoics which declares that every act which the wise man performs is an activity in accord with every virtue; and although, as it appears, one particular virtue performs the chief role in every act, yet it but heartens on the other virtues and directs them toward the goal.

Plutarch goes so far as to say that after recounting each of the deeds of Alexander he wants to exclaim “Like a philosopher!” He gives several examples but one should suffice here:

When he saw Darius pierced through by javelins, he did not offer sacrifice nor raise the paean of victory to indicate that the long war had come to an end ; but he took off his own cloak and threw it over the corpse as though to conceal the divine retribution that waits upon the lot of kings. ‘Like a philosopher!’

Plutarch says that all men have the capacity for wisdom, and Nature herself is capable of leading any one of us toward virtue and what is good. In the face of adversity, however, our wisdom is prone to abandon us. Philosophers, however, have the advantage of having, by means of rational argument, secured their principles, in advance, so that their judgement may remain sound in the face of danger.

Fear not only drives out memory, he says,“but it also drives out every purpose and ambition and impulse, unless philosophy has drawn her cords about them.” Alexander, by contrast, courage and self-mastery were so firmly entrenched in Alexander’s character that he remained faithful to them during the most challenging times. That practical wisdom is what made him exceptional, rather than scholarship or theoretical knowledge of philosophy.

The Politics of ZenoAfter the death of Alexander, when Zeno was still a young boy, in 323 BCE, his short-lived empire fragmented into several successor states, over which his generals fought. Macedonia, Cyprus, Athens, and the rest Greece eventually came under the control of the Antigonid dynasty, founded by one of Alexander’s generals called Antigonus I Monophthalmus, the one-eyed. His grandson, Antigonus II Gonatas, had inherited this kingdom, or small empire, by the time Zeno founded the Stoic school, in 301 BCE.

The younger Antigonus was known as a patron of philosophers, particularly the Cynics and, subsequently, the Stoics. Indeed, he appears to have become a prominent student and follower of Zeno. Diogenes Laertius mentions Antigonus many times throughout his Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, where he states:

Antigonus (Gonatas) also favoured him [Zeno], and whenever he came to Athens would hear him lecture and often invited him to come to his court.

Following the death of Zeno, under the rule of Antigonus, pillars were erected commemorating the founder of Stoic philosophy, in the grounds of both the Lyceum and Academy of Athens. Antigonus subsequently donated a large sum of money to Cleanthes, the second head of the Stoic school, to fund its continuation.

Although we tend to think of the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius as the most famous example of a Stoic-influenced ruler, Antigonus II Gonatas, four centuries earlier, was apparently both a Stoic and a king. Zeno’s cosmopolitan vision of the ideal Stoic Republic, which Plutarch claims to be inspired by Alexander’s Hellenism, presumably had some influence upon Antigonus, although links between the teachings of Stoic philosophy and the policies of his rule are difficult to discern from the sparse historical evidence.

As we’ve seen, in his On the fortune or the virtue of Alexander, Plutarch sums up the Utopian political ideals of Zeno’s early Stoicism as teaching that “all the inhabitants of this world of ours should not live differentiated by their respective rules of justice into separate cities and communities, but that we should consider all men to be of one community and one polity”. It was this cosmopolitan philosophy, which Plutarch says was first introduced by Alexander who encouraged his army, and conquered subjects, to “consider as their fatherland the whole inhabited earth”, of which his military camp formed the capital.

Diogenes Laertius likewise claims that a text called the Republic, attributed to Diogenes the Cynic stated that “The only true commonwealth was that which is as wide as the universe”, and the Republic of Zeno appears to have closely resembled this text. Many controversial views were attributed to Zeno’s Republic by critics of Stoicism, from which it’s difficult to ascertain the truth about its contents. However, it’s worth noting, in relation to what Plutarch said, that the satirist Lucian later described the Stoic ideal Republic as follows:

I remember hearing a description of it all once before from an old man, who urged me to go there with him. He would show me the way, enroll me when I got there, introduce me to his own circles, and promise me a share in the universal Happiness. But I was stiff-necked, in my youthful folly (it was some fifteen years ago); else might I have been in the outskirts, nay, haply at the very gates, by now. Among the noteworthy things he told me, I seem to remember these: all the citizens are aliens and foreigners, not a native among them; they include numbers of barbarians, slaves, cripples, dwarfs, and poor; in fact any one is admitted; for their law does not associate the franchise with income, with shape, size, or beauty, with old or brilliant ancestry; these things are not considered at all; any one who would be a citizen needs only understanding, zeal for the right, energy, perseverance, fortitude and resolution in facing all the trials of the road; whoever proves his possession of these by persisting till he reaches the city is ipso facto a full citizen, regardless of his antecedents. Such distinctions as superior and inferior, noble and common, bond and free, simply do not exist there, even in name. — Hermotimus, or the Rival Philosophies.

This is clearly philosophical cosmopolitanism. Full citizenship, though, is equated here with wisdom and virtue, rather than merely allegiance to Alexander or his successors, although the spread of Hellenism through their conquests perhaps helped to make this philosophical vision conceivable.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

ConclusionAlmost five centuries after Zeno founded the Stoic school, the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, the last famous Stoic of antiquity, described his political vision, in one of the most remarkable passages of the Meditations:

…the idea of a republic in which there is the same law for all, a republic administered with regard to equal rights and equal freedom of speech, and the idea of a kingly government which respects most of all the freedom of the governed. — Meditations, 1.14

Throughout the Meditations, Marcus alludes to the importance of seeing the rest of mankind, even our enemies, as brothers, and our kin. Marcus appears, as we’ve seen, to have resisted the Roman habit of placing Alexander on a pedestal — and he was perhaps no great admirer of him. Nevertheless, if Alexander’s imperialism paved the way for early Stoic cosmopolitanism, as Plutarch claimed, it’s perhaps no surprise that a Roman emperor would find Stoicism so congenial to his own political values.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.