Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 37

January 12, 2023

The Philosophical Therapy of Anaxagoras

I’m currently researching the philosophy of the Presocratic philosopher Anaxagoras for a book I’m writing about Socrates. I’m very interested in the therapeutic dimension of Greek philosophy, particularly Stoicism. So I’ve been wondering if Anaxagoras’ philosophy can potentially be read from that perspective. I’m not suggesting that Anaxagoras was a psychotherapist, or that his philosophy can be reduced to therapeutic techniques, or even that this is necessarily how he intended parts of his philosophy to be received. I’m simply interested in whether ancient followers of his philosophy would have potentially derived psychological benefits from it, and whether some of his ideas could perhaps benefit modern readers in a similar way.

Our evidence for the life and thought of Anaxagoras is fragmentary, obscure at times, and even, prima facie, contradictory — it’s notoriously problematic for modern scholarship. With that caveat in place, I’ll excuse myself for adopting a particular reading of the extant fragments, which I won’t attempt to justify in this article, because my goal here is to focus on exploring possible psychological benefits of the teachings, as they’re handed down to us in the surviving literature. I’ll leave it to others to decide how accurate the resulting account of his life and thought is, although, of course, I’ve attempted to base it on a reasonable interpretation of the available evidence. So how can the philosophy of Anaxagoras actually help us today?

The Life of AnaxagorasI’ll begin by saying a little about Anaxagoras’ life, for historical context. He was a philosopher from Klazomenai in Ionia, on the Aegean coast of modern-day Turkey. He was probably born around 500 BCE and died around 428 BCE, although these dates are rather uncertain. As a young man, aged around 20, he arrived in Athens, and was, it’s claimed, the first there to actually be called a “philosopher”. He was, indeed, the earliest representative at Athens of the so-called Ionian school. Klazomenai had formerly been controlled by Athens but in 387 BCE it became part of the Persian empire, hence Anaxagoras may have been viewed by some as a Persian subject, or at least a potential sympathizer. As a foreign thinker residing in Athens, he naturally aroused curiosity and suspicion.

Anaxagoras famously stated that the universe was caused by something called Nous, a cosmic intellect which organized matter into the distinct objects of our experience. He placed so much importance on this concept that he earned himself the nickname Nous, which would perhaps be a bit like the public dubbing a well-known intellectual today “Brains” or “The Thinker”, although it was possibly meant in a disparaging sense like “Egghead” or maybe even someone who thinks too much for his own good.

He was, in a sense, a typical intellectual. He was known for being lofty and high-minded. The only book written by him seems to have been concise, and expressed in a pleasant, lucid style. His life was wholly dedicated to the quest for truth, causing him to seem aloof from everyday materialistic concerns. Anaxagoras came from a wealthy and noble family, yet was content to give away his fortune. When his relatives accused him of neglecting his inheritance, he simply replied “Why don’t you look after it then?”, and handed it over to them.

He said “I care greatly for my native land,” as he gazed upwards.

Having migrated to Athens, where he lived as a foreign resident or metic, he focused entirely on his philosophical studies, and therefore remained uninvolved in public life, something many Greeks viewed with suspicion. He was once asked why he believed he had been born, replying “To study the sun, the moon, and the heavens.” He appears to have viewed the goal of life in general as the pursuit of such knowledge. Someone scolded him saying “Do you care nothing for your native land?” He simply pointed at the stars, telling them to hush, and saying “I care greatly for my native land,” as he gazed upwards. If he meant to imply that he considered himself a citizen of the cosmos, he may be seen as foreshadowing the cosmopolitanism of later thinkers, such as Diogenes the Cynic, and the Stoics.

Anaxagoras, like other Ionian philosophers, emphasized naturalistic interpretations of phenomena that Greeks often viewed as supernatural, or of divine origin. He reputedly predicted the fall to earth, in 467 BCE, at Aegospotami on the Hellespont, of a large meteorite, possibly coinciding with the passing of Halley’s comet, from which it may have originated. The meteor was described as a lump of stone, around a “wagonload” in size. Anaxagoras’ association with this event appears to have bolstered his fame considerably. Whether or not he really predicted the date of the meteorite’s impact, he could point to the find as evidence for his controversial claim that celestial bodies were made of something akin to burning stone or iron.

In particular, Anaxagoras became known for teaching his followers that the sun was a blazing lump of stone or iron. He was implying, of course, that the sun was not a divine being, riding a horse-drawn chariot across the sky. At best, such myths were metaphors for natural phenomena. Naturalistic explanations, though, still caused some controversy. Many Athenians were not yet used to, and perhaps not entirely ready for, such radical ideas.

Although Anaxagoras’ whole philosophical method must have ruffled some feathers, it seems his claims about the sun may have been the final straw for his critics. He found himself dangerously at odds with conservative religious elements in Athenian society. The conflict was perhaps especially with regard to the official worship of Helios, the sun god. Helios was a minor deity, in the state religion, primarily associated with harvest festivals, and the cult of Demeter at Eleusis. That said, the sun becomes a “great god”, portrayed as much more important, in the writings of Greek poets and certain philosophers, including Plato. The god Apollo later became identified with the sun, or Helios, but it is doubtful that he typically was during the 5th century, except perhaps in a lost tragedy of Euripides called Phaethon. This play was connected with Anaxagoras by later authors, probably because it tells the story of a young mortal whose attempts to master the sun lead to disaster, and end with him, blasted by Zeus, crashing down to earth by a great river, like a meteorite.

The Trial and ExileAnaxagoras is believed to have served as a tutor to Pericles, who later became the leading statesman in the Athenian democracy. They must have been good friends. Pericles retained Anaxagoras as an advisor until the philosopher was placed on trial at Athens, around 450 BCE. Anaxagoras was charged with impiety, for claiming the sun is a red-hot lump of iron, and possibly also conspiring with Greece’s enemies, the Persians. If the teacher could be condemned, it would subsequently be easy to argue that his famous student had been corrupted. So it is often assumed that the trial was really an indirect attack on Pericles by his political opponents, either Cleon or Thucydides, son of Melesias (not the famous historian). Pericles had had his main political rival, Cimon, the leading figure of the oligarchic faction, exiled by means of an ostracism vote, ten years earlier. As it happens, Cimon returned to Athens about a year before the charges were brought against Anaxagoras — so we may wonder whether he was somehow involved.

Anaxagoras was found guilty and, according to one account, sentenced to death. Pericles, however, stood before the the court, placing his own reputation on the line, to defend his friend and tutor. He courageously asked the people whether they could find a single thing to criticize in his own conduct. They could not. He said, “Well, I am this man’s student. Do not be carried away by slander, and put him to death, but listen to me and release him.”

Some say, Anaxagoras was brought into court so frail from disease, that the jury took pity upon him. The sentence was reduced to exile, and a fine of five talents, a small fortune. One talent was enough silver to pay the crew of a trireme for a month. Pericles may have paid the fine on Anaxagoras’ behalf, if it’s true he’d given away his own inheritance

Anaxagoras spent his remaining years exiled in Lampsacus, a Greek city on the eastern side of the Hellespont. It happens to face the very spot, at Aegospotami, where the meteorite had fallen about seventeen years earlier. The people of Lampsacus held Anaxagoras in very high regard, although the public indignity of his trial and banishment reputedly left him a broken man. His friend Pericles would eventually die of the plague at Athens, in 429 BCE. Anaxagoras passed away the following year, by suicide according to some. Diogenes Laertius, seven centuries later, would therefore write:

The sun’s a molten mass,

Quoth Anaxagoras;

This is his crime, his life must pay the price.

Pericles from that fate

Rescued his friend too late;

His spirit crushed, by his own hand he dies.

Photo by Taylor Flowe on UnsplashSocrates and Anaxagoras

Photo by Taylor Flowe on UnsplashSocrates and AnaxagorasCuriously, Socrates, who was known for seeking out the greatest intellectuals of his era, seems never to have met Anaxagoras, the man who, only a generation earlier, had founded the study of philosophy at Athens. Socrates must have been around twenty years old when Anaxagoras, aged around fifty, stood trial. He may already have been dabbling in the study of philosophy for up to five years.

It’s natural for us to imagine that Socrates would have loved nothing more than to have spoken with Anaxagoras and yet for some reason was unable to do so. The most obvious explanation would be that, in his youth, Socrates lacked the social connections who may have introduced him to Pericles’ intellectual circle. (Perhaps Anaxagoras charged hefty fees, which Socrates could not afford, although this would clash with the former’s portrayal as a man indifferent to wealth.) In a sense, though, Socrates spent the rest of his life making up for this missed opportunity, by mingling with most of the other great minds of Athens, including the famous tragedian Euripides, who had, like Pericles, been a student of Anaxagoras.

Ironically, then, it may have been the very attempt to censor Anaxagoras that finally placed his teachings in the hands of Socrates and countless other young Athenians.

After the trial, Socrates became a student of Anaxagoras’ successor at Athens, Archelaus, who was probably the first Athenian citizen to teach natural philosophy at Athens. He seems to have read to Socrates from a copy of the only book written by Anaxagoras. The little book of Anaxagoras later became widely available, and we’re told it could be purchased, in the Agora, for only a single drachma. Clearly, those who sought to “cancel” Anaxagoras, for impiety, had completely failed to suppress his writings. One possibility is that Anaxagoras had circulated this text privately among his friends and students at first but after his exile, once he was gone and could no longer be held responsible or control the publication of his writings, cheap copies became more freely available. Ironically, then, it may have been the very attempt to censor Anaxagoras that finally placed his teachings in the hands of Socrates and countless other young Athenians.

Socrates was, as a young man, fascinated by natural philosophy. However, he eventually became frustrated with the explanations it offered of natural phenomena. When he learned that Anaxagoras had made Nous, or Intellect, the cause of the universe, Socrates was exhilarated because it seemed to promise a more profound level of philosophical analysis. Minds have intentions, which Socrates hoped to study and understand. Socrates therefore wanted to know more about what this cosmic Nous actually was. However, his joy soon turned to disappointed, when he discovered that Anaxagoras made quite superficial use of this concept, and offered little explanation of its meaning. Nous, which explains everything for Anaxagoras, is itself explained by nothing. This initial frustration perhaps fuelled Socrates’ later insistence on the most important concepts in an argument being clearly defined from the outset.

Socrates, it seems, assumed that, being goal-directed or “teleological” in nature, cosmic Nous must have some plan for the world. In order to understand nature, therefore, we would have to understand what Nous considered the best arrangement of things. Anaxagoras was little help in this regard and Socrates realized that trying to analyze the real nature of things in terms of Nous would simply end in speculation. As a result of this dead end, he gradually abandoned the study of natural philosophy in favour of a new approach, which focused primarily on studying human nature, ethics, and what is best for man, i.e., the virtues.

Socrates was therefore critical of Anaxagoras’ philosophy, and sought to distance himself from his teachings, which he was accused, in his own trial for impiety, of repeating. Nevertheless, he also seems to have admired Anaxagoras, and to have been influenced by him in certain ways. There are such obvious parallels between the two philosophers’ lives that it’s difficult to imagine that Socrates did not feel as though he was walking, at times, in the footsteps of his ill-fated predecessor.

For instance, in Aristophanes’ satire The Clouds, first performed in 423 BCE, five years after the death of Anaxagoras, Socrates is pilloried as a natural philosopher, running a school called the Phrontisterion, “Thinkery” or “Thinking Shop”, and in the Symposium of Xenophon, an angry man is therefore shown disparaging Socrates as the Phrontistes, “The Thinker”. These inevitably remind us of Anaxagoras’ nickname of Nous, the archetypal intellectual or thinker, in the eyes of contemporary Athenians. Socrates took Anaxagoras’ place as Athens’ foremost philosopher, but he was a very different sort of thinker, who placed more importance on asking the right question than speculating about the answers, who didn’t present himself as an “expert”, and who was more interested in human nature than the nature of celestial phenomena.

January 11, 2023

Stoicism in a Time of Pandemic

Re-reading a newspaper article that I wrote at the start of the pandemic about how Marcus Aurelius used Stoicism, in the Meditations, to cope with the Antonine Plague. It struck me that, in part at least, the Meditations can be seen as Marcus’ notes to himself on coping with the psychological and moral challenges of the plague — or, if you like, as a manual for coping Stoically during a pandemic.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

HighlightsHow Marcus used Stoicism to cope with his own pandemic

The Dichotomy of Control

Modelling virtue

Contemplating our own mortality

Original article titled Stoicism in a Time of Pandemic, from The Guardian newspaper, April 2020.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

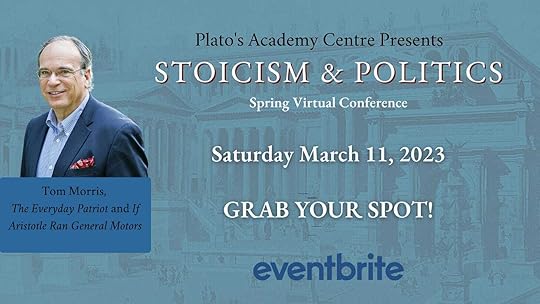

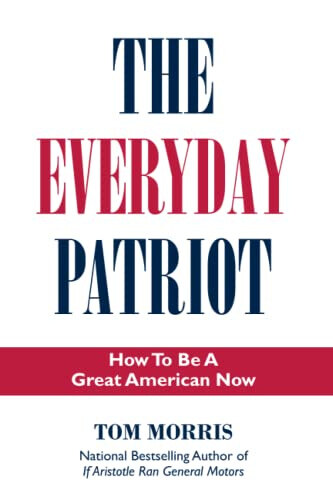

Book Giveaway: The Everyday Patriot

I am delighted to announce that everyone who registers now for the Plato’s Academy Centre’s March 11th virtual event, Stoicism and Politics, will be automatically entered our free prize draw for a chance to win a signed copy of Dr. Tom Morris’ new book The Everyday Patriot!

Registration for this online event is completely free of charge, although we’re grateful for your donations, which help the nonprofit to continue running events like these.

Tom Morris is also the author of The Stoic Art of Living and several other books on philosophy. He is one of our featured speakers at the forthcoming Stoicism and Politics event. See the event listing for the current program of speakers.

What people are saying…

What people are saying…“The programmes offered are exciting and courageous. ”

“Find the time to watch as very informative.”

“Plato Academy's virtual events are a pleasure to watch. I learn so much, so fast!”

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

January 10, 2023

The Socratic Philosophy of Wednesday Addams

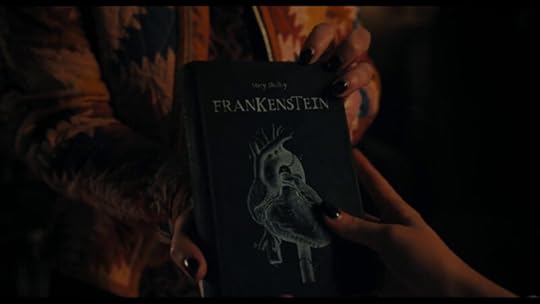

There’s an obvious, albeit slightly mangled, reference to one of the famous Socratic paradoxes in episode six (“Quid Pro Woe”) of the Netflix series, Wednesday. Ms Thornhill, the botany teacher and “dorm mom”, played by Christina Ricci, offers Wednesday Addams a beautiful hardback copy of Mary Shelley’s novel, Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus. This provides a surprising opportunity for the scriptwriters to touch upon some very radical philosophical ideas.

Still from Wednesday (2022) from Netflix. Reproduced under fair use.

Still from Wednesday (2022) from Netflix. Reproduced under fair use.Saying that someone disguises their evil motives as good is, of course, not at all the same as saying that they have mistaken evil for good.

Wednesday, an aspiring writer, seems to know the book well and says Mary Shelley is one of her “literary heroes”. She then appears to cite the following quote from the text, or perhaps from another work by Mary Shelley.

No man chooses evil because it is evil. He only mistakes it for happiness, the good he seeks.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Wednesday uses this to explain her belief that some people, including one of her main antagonists in the series, “do bad things under the guise of protecting the greater good.” That’s a disappointingly sloppy reading on her part. Saying that someone disguises their evil motives as good is, of course, not at all the same as saying that they have mistaken evil for good. Wednesday’s philosophical interpretation of the maxim, therefore, contains a rather egregious error. Nevertheless, it’s still great to see this reference to philosophy in a popular television series.

Still from Wednesday (2022) from Netflix. Reproduced under fair use.Mary Wollstonecraft not Mary Shelley

Still from Wednesday (2022) from Netflix. Reproduced under fair use.Mary Wollstonecraft not Mary ShelleyThere appears to be another mistake in this scene, though. Wednesday (or the show’s scriptwriters) imply that this quote comes from Frankenstein. It is also attributed to Mary Shelley on Internet quotation sites, which are notoriously unreliable. These words appear nowhere in the novel, though.

They were written, in fact, by Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), a pioneering feminist philosopher. She died of septicaemia shortly after giving birth to her daughter, also called Mary Wollstonecraft, later Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley but better-known simply as Mary Shelley (1797–1851), the author of Frankenstein.

The words quoted by Wednesday can, it turns out, be traced to Mary Wollstonecraft’s pamphlet titled A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790).

It may be confidently asserted that no man chooses evil, because it is evil; he only mistakes it for happiness, the good he seeks. And the desire of rectifying these mistakes, is the noble ambition of an enlightened understanding, the impulse of feelings that Philosophy invigorates.

This was certainly not an original idea. Although Mary Wollstonecraft doesn’t mention its source, it would have been very familiar to many of her educated readers at the time, in Georgian England.

Still from Wednesday (2022) from Netflix. Reproduced under fair use.Socrates and the Stoics

Still from Wednesday (2022) from Netflix. Reproduced under fair use.Socrates and the StoicsThe notion that no man does evil willingly, but rather in error, is best-known as one of the famous paradoxes attributed to Socrates. For example, in Plato’s dialogue known as the Protagoras, Socrates is shown saying that wise men do not assume that others do evil willingly, or knowingly.

I am fairly sure of this — that none of the wise men considers that anybody ever willingly errs or willingly does base and evil deeds; they are well aware that all who do base and evil things do them unwillingly.— Protagoras, 345d-e

The Stoic philosophers also followed Socrates in this regard. For example, Marcus Aurelius wrote to himself:

If men do rightly what they do, we ought not to be displeased. But if they do not do right, it is plain that they do so involuntarily and in ignorance. For as every soul is unwillingly deprived of the truth, so also is it unwillingly deprived of the power of behaving to each man according to his deserts. — Meditations, 11.18

For Marcus, this way of thinking serves an important role as a cognitive (or thinking) strategy helpful in mastering our own anger.

People sometimes object to this idea by claiming that many individuals, such as criminals, appear to do bad things in full knowledge that they are wrong. Of course, Socrates and the Stoics also realized this — for them to have believed otherwise would have been extraordinarily naive. What they meant was more subtle: that such individuals are typically unable to define the good. That means they are acting in ignorance, in a sense, of what is right and wrong.

Most of us also know, moreover, what other people consider to be wrong. That’s not the same as agreeing with them or genuinely understanding what it means for something to be wrong. There are, in fact, many ways in which we can mistake evil for good, or simply mistake evil for what is morally indifferent. “I didn’t think it was a big deal”, is one common way, for instance, that people rationalize and justify wrongdoing.

Socrates and the Stoics realized that unless we believe that an individual understands the true nature of goodness, we have to view their failing to do good as the product of ignorance on their part. That also means that such wrongdoing cannot be considered completely voluntary, because we’re not really free to do good unless we know what to do and how to do it.

Still from Addams Family Mystery Mansion computer game. Reproduced under fair use.

Still from Addams Family Mystery Mansion computer game. Reproduced under fair use.By coincidence, in the earlier animated movies, The Addams Family (2019) and The Addams Family 2 (2021), Wednesday has a pet octopus by the name of Socrates. (Although it goes by other names, including Aristotle, in other versions of the franchise.) I don’t think the show’s scriptwriters realized that the quote above derives ultimately from Greek philosophy, though. Nevertheless, I’m glad they included it, because it’s a powerful enough philosophical paradox to get people thinking more deeply, almost two and a half thousand years after it was first made famous by the original Socrates, as portrayed in Plato’s dialogues.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

January 6, 2023

Marcus Aurelius and Carnuntum

This podcast episode contains the audio recording from a conversation about Marcus Aurelius, which I had with Markus Wachter, the CEO of the Carnuntum Archeological Park, at the Museum Carnuntinum, in 2019. I was visiting Austria for around a week, doing research for my books on Marcus Aurelius. The audio was recorded live in the main hall of the reconstructed Roman villa in the archeological park, hence the acoustics.

Marcus stationed himself at the Roman legionary fortress of Carnuntum, for part of the Marcomannic Wars. He included the note “At Carnuntum” near the start of the Meditations, proving that he must have written at least part of the manuscript there.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thanks to Landessammlungen Niederösterreich, Archäologischer Park Carnuntum for permission to film, and to Adam Piercey for filming and editing.

You can also watch the video hosted on Substack.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of LifeMarcus Aurelius and CarnuntumWatch now (23 min) | Welcome to the new (beta) video hosting feature in Substack! My first upload here is a video of a conversation about Marcus Aurelius, which I had with Markus Wachter, the CEO of the Carnuntum Archeological Park, at the Museum Carnuntinum, in 2019. I was visiting Austria for around a week, doing research for my books on Marcus Aurelius…Read more9 days ago · 10 likes · 4 comments · Donald J. Robertson

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of LifeMarcus Aurelius and CarnuntumWatch now (23 min) | Welcome to the new (beta) video hosting feature in Substack! My first upload here is a video of a conversation about Marcus Aurelius, which I had with Markus Wachter, the CEO of the Carnuntum Archeological Park, at the Museum Carnuntinum, in 2019. I was visiting Austria for around a week, doing research for my books on Marcus Aurelius…Read more9 days ago · 10 likes · 4 comments · Donald J. RobertsonThank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

January 5, 2023

Exclusive: Marcus Aurelius Poster

We are delighted to be able to bring you this downloadable PDF of a full-color, 16” x 20” Marcus Aurelius poster designed by Zé Nuno Fraga, courtesy of St. Martin’s Press. Zé is the award-winning Portuguese illustrator, responsible for the artwork in our graphic novel, Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius.

The poster depicts Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, with a quote from the book, spoken by Emperor Hadrian,

You say your name is Verus, meaning true, but I shall call you Verissimus, the most true of all.

This content is exclusively accessible to our paid Substack subscribers. If you’re already signed up, simply click the download button below to access the PDF file. Otherwise, if you want to sign up for a trial subscription, you’ll unlock access to the download link.

January 3, 2023

Coming Soon: Heroic Coach Program

I first started training therapists and life coaches about 25 years ago. People often ask me if there are any online courses for life coaching or self-improvement that would be good for someone interested in Stoicism.

I don't usually recommend courses unless I know quite a bit about the content and the people running them. So I'm pleased to be able to say that there's a really good 300-day online training coming up soon by Brian Johnson, author of the book A Philosopher's Notes, which draws heavily on Stoic philosophy – a subject he's as enthusiastic about as I am! (He also has an upcoming book called Heroic.)

My wife, , did Brian's Stoicism 101 Masterclass a while back and published a short review, which is now available via her Substack newsletter.

Review of Stoicism 101: Online Course from Brian Johnson

The Heroic Coach program starts on January 15th. I told Brian I was going to pass on the details. Registration has already opened, so you can book right now. It’s a fantastic course!

I’m a member of the Heroic Coach Guest Faculty, along with 70+ other teachers who connect with the Heroic Coach community for exclusive live sessions that happen every month. In my most recent session I shared what it was like to write my latest book, Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, how to start with the end in mind, why death is so present in Stoicism, how to bring Stoicism to life, the Stoic approach to agency…. and more! If you want to sample some of their content, you can watch that entire session for free.

I've been enjoying Brian's content for several years now... Over the next few days, I'll be sending you some more information about the amazing resources he has available on Stoicism, etc.

Please let me know your thoughts.

Hope you enjoy the course,

Donald Robertson

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

PS. Here’s a sample from the many testimonials you’ll find on the Heroic Coach site:

“The Heroic Coach Program has had a greater impact on me than any other program I have pursued in my lifetime. The program has helped me define my purpose, outline the framework for a masterpiece day, and operationalize many of the theories introduced.” – Thomas Pierson

“Before joining Heroic Coach I had this deep desire to present my best to the world but didn't know exactly how to do so. Heroic Coach has helped me to gain the skills to live with Arete and to also be well equipped to serve mankind heroically.” – John Nshom

“I have learnt so much about me, and how to optimize my life through implementing protocols and understanding how powerful my actions are moment to moment to moment. I have learnt about the paramount importance of identifying my Soul Goal and using my soul force to seek eudaimonia and to love my soul. Thank you.” – Kamal Patheja

December 29, 2022

How to Deal with Overwhelming Feelings

What can ancient philosophy teach us, in general, about coping with overwhelming emotions? In this article, I’ll summarize some of the advice given by Pythagoreans and Stoics. You’ll find a bullet-point list of practical tips followed by a more detailed discussion taken from my book on Stoicism and cognitive psychotherapy.

Photo by Jose Aragones on UnsplashSummary of Techniques

Photo by Jose Aragones on UnsplashSummary of TechniquesLearn to spot the early-warning signs of unhealthy desires or irrational emotions before they spiral out of control

Don’t allow yourself to be “carried away” by your feelings but take them as a signal you should pause for thought

Gain cognitive distance from your feelings by reminding yourself that the underlying impression (value-judgement) is not the thing itself but just the internal representation of it, and that you are upset not by things themselves but you your value-judgments about them

If the feelings is overwhelming, postpone responding to it, or even thinking about it, until things have calmed down and you’re able to rationally evaluate it

First apply the general principle of Stoic psychology by asking yourself whether the underlying value-judgement is about something up to you (directly under your control) or not. If it is not, then remind yourself of the reasons why Stoics judge external or bodily things (not “up to us”) to be ultimately “indifferent” with regard to the goal of life

Consider what the hypothetical ideal Sage, someone perfectly wise and good, would do in response to the same situation, and try to emulate their example. Alternatively, ask yourself what faculties or virtues nature has given you that correspond with the demands of the situation, such as the capacity for courage or self-control, etc.

December 28, 2022

Marcus Aurelius and Carnuntum

Welcome to the new (beta) video hosting feature in Substack! My first upload here is a video of a conversation about Marcus Aurelius, which I had with Markus Wachter, the CEO of the Carnuntum Archeological Park, at the Museum Carnuntinum, in 2019. I was visiting Austria for around a week, doing research for my books on Marcus Aurelius.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Marcus stationed himself at the Roman legionary fortress of Carnuntum, for part of the Marcomannic Wars. He included the note “At Carnuntum” near the start of the Meditations, proving that he must have written at least part of the manuscript there.

Thanks to Landessammlungen Niederösterreich, Archäologischer Park Carnuntum for permission to film, and to Adam Piercey for filming and editing.

At a writing desk in the reconstructed Roman villa at Carnuntum

At a writing desk in the reconstructed Roman villa at CarnuntumThank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

December 27, 2022

Happy Birthday From Marcus Aurelius

It’s my birthday today (27th Dec) so I’ve scheduled one of my favourite curiosities from ancient literature: a beautifully-written birthday greeting composed by the young Marcus Aurelius.

In 1815, the Italian scholar Angelo Mai discovered a cache of letters between the Roman rhetorician Marcus Cornelius Fronto and several of his friends, including his student, Marcus Aurelius.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

One of these letters contains a birthday greeting from Marcus to Fronto, believed to have been written around 140–143 AD, when Marcus would have been a young Caesar, somewhere between nineteen and twenty-two years old.

The tone of Marcus’ letters is generally strikingly affectionate. Indeed what he writes of Fronto’s influence later, in The Meditations, suggests his rhetoric master encouraged Marcus to show more affection toward his friends and family.

Letter from Marcus to FrontoFrom Fronto I learned… that generally those among us who are called Patricians are rather deficient in natural affection. — Meditations, 1.11

Hail, my best of masters.

I knew that on everyone’s birthday his friends undertake vows for him whose birthday it is. I, however, since I love you as myself, wish to offer up on this day, which is your birthday, hearty prayers for myself.

I call, therefore, with my vows to hear me each one of all the Gods, who anywhere in the world provide present and prompt help for men; who anywhere give their aid and shew their power in dreams or mysteries, or healing, or oracles; and I place myself according to the nature of each vow in that spot where the god who is invested with that power may the more readily hear.

Therefore I now first climb the citadel of the God of Pergamum and beseech Aesculapius [the god of healing] to bless my master’s health and mightily protect it.

I entreat and pray that, if ever I know aught of letters, this knowledge may find its way into my breast from the lips of none other than Fronto.

Thence I pass on to Athens and, clasping Minerva [Athena, goddess of wisdom] by her knees, I entreat and pray that, if ever I know aught of letters, this knowledge may find its way into my breast from the lips of none other than Fronto.

Now I return to Rome and implore with vows the gods that guard the roads and patrol the seas that in every journey of mine you may be with me, and I be not worn out with so constant, so consuming a desire for you.

Lastly, I ask all the tutelary deities of all the nations, and the very grove, whose rustling fills the Capitoline Hill, to grant us this, that I may keep with you this day, on which you were born for me, with you in good health and spirits.

Farewell, my sweetest and dearest of masters. I beseech you, take care of yourself, that when I come I may see you. My Lady greets you.

[Possibly “my Lady” refers to Marcus’ betrothed, Faustina the Younger, but more likely to his mother, Domitia Lucilla, who was good friends with Fronto’s wife.]

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.