Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 34

March 2, 2023

Stoicism, Self-Help and Modern Psychology

This is the audio of an interview I gave recently for Book Club with Kaiden Kelly, talking about How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, Verissimus, and Stoicism, self-help and modern psychology.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

February 28, 2023

Webcomic: Socrates' Dinner Guests

Below is one of several webcomics about Socrates that I designed, and had illustrated by Ze Nuno Fraga, the award-winning illustrator who did the artwork for our graphic novel, Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius. It’s based on an anecdote found in Diogenes Laertius’ life of Socrates.

He would say that the rest of the world lived to eat, while he himself ate to live.

Socrates invited some wealthy friends round to his house without warning his notoriously quick-tempered young wife, Xanthippe. Xanthippe was upset when he told her, saying she was ashamed of what little they had to offer such important guests for dinner.

February 23, 2023

How Stoicism Cures Anger

Donald discusses what Stoicism teaches us about anger and how it can actually help us in practice today.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

HighlightsWhy anger is a problem

What the Stoics say about anger

Ways in which Stoicism can help us manage anger

The benefits of learning to cope with anger

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

You can read the text of How Stoicism Cures anger on my Substack newsletter.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of LifeHow Stoicism Cures AngerAncient Philosophy as a Therapy for Violent Passions One of the most celebrated physicians and medical researchers of the ancient world, Galen of Pergamon, wrote a book about mental illness, called On Passions and Errors of the Soul. The passion considered most dangerous by Galen and other ancient writers is…Read more2 years ago · Donald J. Robertson

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of LifeHow Stoicism Cures AngerAncient Philosophy as a Therapy for Violent Passions One of the most celebrated physicians and medical researchers of the ancient world, Galen of Pergamon, wrote a book about mental illness, called On Passions and Errors of the Soul. The passion considered most dangerous by Galen and other ancient writers is…Read more2 years ago · Donald J. Robertson

Photo by Daniel Lincoln on Unsplash

Photo by Daniel Lincoln on Unsplash

February 21, 2023

Review: The Stock Horse and the Stable Cat

In this video, Donald and Poppy have fun reviewing The Stock Horse and the Stable Cat, an illustrated children’s book inspired by Stoicism, written and illustrated by Phil Van Treuren and published by stoicsimple.com. They also discuss how thinking about certain philosophical ideas can change children’s emotions and behaviour, in ways that might help them to cope with anger and other challenges in life.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

We both recommend this book because of its helpful Stoic message and beautiful artwork, which we’re sure will be appreciated by adults, and especially by children.

“We get to decide for ourselves how things make us feel,” said the stock horse at last.

“And that is good.”

The Stock Horse and the Stable Cat tells the story of two friends who have very different opinions about what should be called “good” and “bad.” As they walk on the ranch together one autumn day, they gradually realize that their own stubborn opinions of the world might not be the only way to see things.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Here’s the promotional trailer…

February 18, 2023

Seneca (2023) starring John Malkovich | Trailer Reaction

Seneca: On the Creation of Earthquakes, starring John Malkovich, will be released in Germany on 23rd March 2023.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Donald Robertson is the author of How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: the Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius; Verissimus, a graphic novel about Marcus Aurelius; and a forthcoming prose biography of Marcus Aurelius for Yale University Press.

Donald also wrote a biography of Seneca for the Capstone Classics edition of his Moral Letters.

How to Think Like a Roman Emperor

Verissimus graphic novel

Seneca’s Moral Letters (Capstone Classics)

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

February 16, 2023

The Great Discourse of Protagoras

In this episode, I discuss and recite one of the most important philosophical speeches in history — the Great Discourse or Great Speech of the Sophist Protagoras, from Plato’s dialogue Protagoras. This speech contains some remarkable imagery and ideas, which clearly foreshadow many later ideas about social virtue and politics in Greek and Roman philosophy, from Socrates to the Stoics, and beyond.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

HighlightsIntroducing the Great Speech, and why it is so important

Reading an excerpt from Plato’s Protagoras, containing the speech

Summary of the key points, in plain English

The speech can be seen as containing a kind of proto-evolutionary theory of social virtue

Can the capacity for virtue be seen as universal?

Can virtue can be taught?

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

My Synopsis of The Great DiscourseAt first there were gods but no mortal creatures. When the time came, the gods fashioned countless animals by mixing together the elements of fire and earth. Zeus then commanded Prometheus, the Titan, to assign different abilities to each living thing.

Some creatures were naturally slow and so he gave them great strength. Others were weak and so to these Prometheus granted speed. Some he armed while others were given various forms of protection. Small creatures were granted the capability for winged flight or for concealing their dwellings underground. Large beasts had their size for protection. And he took care to grant all creatures some means for their own preservation so that no species should be in danger of elimination by others.

Having equipped them to survive among each other in this way he proceeded to grant them protection against their environment and the harshness of the seasons. He clothed some creatures with dense hair or thick skin, sufficient to endure the heat of summer and ward off the cold through winter months. To some he gave strong hooves, to others claws and hides that did not shed much blood. And every creature was assigned its own source of food. Some pastured on the earth, others ate fruits hanging from trees or roots from beneath the ground. Yet others were predators who fed upon other animals for their meat. To these he assigned limited offspring whereas their prey were more abundant so that there would always be enough to serve as food.

However, having assigned to each species its own special capabilities, Prometheus realized that he had nothing left to give the race of man. Humans are born naked, unshod, unarmed, and with no bed in which to lay their head and rest safely. Not knowing what else to do, Prometheus stole the technical wisdom of the gods Hephaestus and Athena and gave it to mankind, along with the gift of fire.

Once men were granted these divine gifts, they sensed their kinship to the gods and began to pray and build altars to them. They invented clothing, bedding, dwellings, agriculture, and even the use of language to express their thoughts and acquire learning. Men lived apart at first but finding themselves beset continually and harassed by wild beasts they sought to build cities for their own mutual protection.

However, the wisdom that concerns our relations with others belonged to Zeus alone, king of the gods and patron of friendship and families. No sooner than men gathered together trying to save themselves, being lawless, they began instead to wrong one another and fight among themselves. And so scattering once again from their failed cities, they continued to perish in the wild.

Looking down upon this chaotic scene with dismay, Zeus feared for the destruction of the entire human race. He therefore sent Hermes, the messenger of the gods, to teach mortals about justice and to imbue them with a sense of shame concerning wrongdoing. By this means Zeus now granted mankind the capacity to unite themselves in cities, maintaining order through the bonds of friendship and a sense of community.

Hermes asked Zeus whether he should distribute justice, and other social and political arts, among men in the same way as technical knowledge concerning other crafts. One man who possesses the knowledge of medicine, he said, was enough to benefit many men, and so on. However, Zeus decreed that every human being must be granted some knowledge of justice and the arts needed to unite society. He even laid down the law that anyone who was found unable to respect justice and the rule of law should be put to death, being a plague on the city.

For this reason, said Protagoras, we seek the advice only of those few who are experts with regard to crafts such as medicine or carpentry but concerning justice we allow every citizen to have his say. Further, if someone boasts of being an expert in playing the flute or some such art but is nothing of the sort then he is ridiculed for his folly. However, anyone who claims not to participate in justice risks being expelled from society because each and every citizen is expected to share at least somewhat in this capacity, which allows him to live harmoniously in the company of others.

February 15, 2023

New Trailer: John Malkovich in "Seneca"

Is this the Seneca you expected to see on the big screen, or not?

The trailer below has just been released for director Robert Schwentke’s long-awaited movie Seneca: On the Creation of Earthquakes (IMDB). I think John Malkovich is a good choice to play the Stoic philosopher. From what I understand, the movie is a black comedy, which will explore Seneca’s troubled relationship with Emperor Nero. It may come as a shock to some modern readers of Seneca, though, to discover that his life didn’t always seem to reflect his moral principles. See the excerpt from my biography of Seneca below, if you’re interested in finding out more!

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Some quotes from the trailer…

They laugh at you! The Stoic preacher of the simple life who got filthy rich being Nero's ghostwriter.

...a bargain not many good men have made when agreeing to help bad regimes but, you know, I did it for Rome!

My Biography of SenecaPerhaps I can become my best Seneca by playing Socrates.

A few years ago, I was commissioned to write a short biography of Seneca for the Capstone Classics selection from his letters to Lucilius, which you can find on Goodreads, and in all good bookstores. In many people’s minds, an image of Seneca as a wise and virtuous historical predominates, a man who lived simply despite his station in life. I wanted to highlight some of the criticisms of Seneca that are explicitly stated, or clearly implied, in ancient sources, though. I felt they’d simply been ignored for far too long. That’s not to say I agree with them — we can never be certain — but I felt that most existing accounts of his life were misleading because they brushed many serious concerns about his life under the carpet.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Excerpt: The Life of SenecaLucius Annaeus Seneca, also known as Seneca the Younger, is one of the most compelling and yet paradoxical figures in Roman history. Ancient historians, particularly Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio, provide us with important details about his life. These mainly regard Seneca’s relationship with Nero, with whose rule as emperor his own story is intertwined. However, our information from these sources is very sparse and its reliability has often been questioned. On the other hand, Seneca himself was a very prolific writer. Yet if we turn to his works for clues about his life and character, we encounter another notorious problem – he was carefully constructing his own public image.

What Seneca tells us about himself often says more about how he wished to appear than about how he actually was in reality.

Seneca’s writings employ rhetorical methods to knowingly paint a picture of his life that is, in many ways, quite at odds with the historical evidence. What Seneca tells us about himself often says more about how he wished to appear than about how he actually was in reality. For example, he was by profession a rhetoric tutor. He says very little in his writings about his passion for rhetoric, his position as an imperial speechwriter, or his relationship with Nero’s court, though, in order to present himself, first and foremost, as a Stoic philosopher. For instance, those who read only the Moral Letters, written to his friend Lucilius, are bound to form a very different impression of Seneca than those who consult other Roman sources about his life.

A good example would be the way Seneca describes his banishment. The island of Corsica was a thriving colony for wealthy Romans, long known for exporting wine. Seneca almost certainly lived in relative luxury there, probably accompanied by his wife, and attended by a large retinue of slaves. Perhaps slaves even carried him around Corsica in a sedan chair, his favoured mode of transportation mentioned in the later writings (e.g., Moral Letters, 55). Seneca chose, however, to portray himself as stranded on a “barren rock” where he eked out a very austere and lonely existence, surrounded by uncivilised foreigners. Emily Wilson notes that in doing so, he appears to be drawing inspiration from the earlier writings of the poet Ovid, who was in fact exiled to a remote town called Tomis, beside the Black Sea, at the edge of the empire on the so-called Scythian Frontier. Corsica, by contrast, is off the coast of Italy, just two days’ sailing from the port of Ostia, near Rome. Today, of course, it’s a popular holiday destination for tourists.

The enduring success with which Seneca constructed his own persona is perhaps best illustrated, however, by the curious way in which another man’s face was, for many decades, mistaken for his own. Seneca tells us that he suffered throughout life from some kind of chronic lung condition, possibly pulmonary tuberculosis. He says that he “became totally emaciated” through illness and often felt like taking his own life. He was only stopped by the thought that his loving father, who was now advanced in years, would be distraught at losing his son. However, as is often the case, Seneca’s writings contain rather conflicting accounts. He also says that it was his training in philosophy, rather than the thought of his father’s grief, that saved him from committing suicide.

My studies were my salvation. I ascribe it to philosophy that I recovered and got stronger. It is to her that I owe my life, and that is the least of what I owe her. (Moral Letters, 78.3)

This and similar remarks about his inner struggle, and his embrace of simplicity and austerity, shape the perception many readers form of Seneca the man. A bronze bust discovered at Herculaneum in 1794 was believed at first to depict Seneca, whose appearance was otherwise unknown at the time. The face was suitably haggard, slightly emaciated, with straggled hair, and beard, and an intense, perhaps even angst-ridden, expression. This image was widely replicated and found its way into works of art, book illustrations, etc. Today it frequently accompanies quotations from Seneca on the Internet. However, it is not Seneca.

This bust is now known as pseudo-Seneca and believed to be modelled on an earlier Greek sculpture, perhaps of the poet Hesiod. A couple of decades later, in 1813, a double-herm – a single sculpture composed of two busts – was discovered, dating from the 3rd century AD, which depicts Socrates and Seneca back to back. Seneca’s name is conveniently engraved upon his chest. Real Seneca looks completely different from the pseudo-Seneca. He is an overweight, bald-headed man, with a double chin, heavy jowls, pursed lips, and an emotionless, perhaps slightly aloof expression.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Of course, we can’t tell much about Seneca’s character from his facial appearance. What we do know, however, is that Seneca’s modern readers have tended to come away from his writings with an image of him more like pseudo-Seneca than real Seneca, because of how he describes himself in those writings. In real life, perhaps unsurprisingly, Seneca looked less like our stereotypes of an anguished poet-philosopher and more like a typical billionaire Roman senator. “It seems the face of a businessman or bourgeois,” as James Romm put it, “a man of means who ate at a well-laden table.” Seneca’s writings had once again created an image that proved to be dramatically at odds with the truth. With this note of caution in mind, therefore, we may proceed to examine the main events of Seneca’s highly eventful life.

For more of this short biography, check out the Capstone Classics selection from his Letters From a Stoic.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

February 14, 2023

How Marcus Aurelius wrote The Meditations

If thou would’st master care and pain,

Unfold this book and read and read again

Its blessed leaves, whereby thou soon shalt see

The past, the present, and the days to be

With opened eyes; and all delight, all grief,

Shall be like smoke, as empty and as brief.

This epigram is found at the end of a Vatican manuscript of The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, one of the most widely-read spiritual and philosophical classics of all time. Readers of The Meditations are usually aware that Marcus was a Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher. However, they often don’t realize how much more we know about him.

Marcus studied rhetoric under Fronto for many years, and learned certain techniques from him that appear to have shaped the writing of The Meditations.

In my recent book, How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, I drew upon the surviving evidence to make connections between Marcus’ life and thought. We have three main contemporary biographical sources: The Historia Augusta, Cassius Dio’s Historia Romana, and Herodian’s History of the Empire from the Death of Marcus.

CC0 1.0 Universal, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

CC0 1.0 Universal, courtesy of Wikimedia CommonsIn addition to these, one of our most important sources is a cache of letters belonging to Marcus’ family friend and rhetoric tutor Marcus Cornelius Fronto. These were discovered in the early 19th century by the Italian scholar Angelo Mai. They give us a remarkable window into the private life of the Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

We learn, for instance, that Marcus was, in private, an exceptionally warm and affectionate man. He also shows evidence of being adept at diplomacy and at resolving conflicts between his friends. As we’ll see, Marcus studied rhetoric under Fronto for many years, and learned certain techniques from him that appear to have shaped the writing of The Meditations.

Stoics versus SophistsFronto was officially Marcus’ main Latin rhetoric tutor. The Meditations, of course, is actually written in Greek. Marcus was also a student of the most celebrated Greek rhetorician of his day, Herodes Atticus. Both of these men were part of the broad cultural movement known as The Second Sophistic and they can both be described as Sophists. Although, from the time of Socrates onward, there was a historical rivalry and conflict between Sophists and philosophers, perhaps especially Stoics, they were more what we call today frenemies. Indeed, some of Socrates’ best friends were Sophists and he liked to quote their sayings and speeches, although often putting his own twist on their words.

Sophists, especially by Marcus’ time, were typically very well-read in philosophy, although they approached it more a source of arguments and ideas than as a way of life. Despite the historical conflict between Sophists and Stoics, therefore, it should come as no surprise if we find one or two topics being discussed by Marcus and Fronto cropping up in The Meditations. However, what caught the eye of scholars was the obvious similarity between the method of writing described by Fronto and the format of The Meditations.

Fronto’s Method: Finding the Right WordsFronto says that he greatly admires the writings of Cicero as the very “head and source of Roman eloquence.” Nevertheless, having scoured Cicero’s writings for this purpose, Fronto claims that he finds in them “very few words indeed that are unexpected and unlooked for”, by which he means unusual words and phrases of the sort encountered mainly in old poetry. Fronto describes how these must be “hunted out” with great care and the stored up in the memory of an orator as though in a treasurehouse.

By an unexpected and unlooked-for word I mean one which is brought out when the hearer or reader is not expecting it or thinking of it, yet so that if you withdrew it and asked the reader himself to think of a substitute, he would be able to find either no other at all or one not so fitted to express the intended meaning. Wherefore I commend you greatly for the care and diligence you shew in digging deep for your word and fitting it to your meaning. — Fronto

A great orator spends time finding the perfect word, or phrase, to express his meaning. He avoids cliché where possible. Fronto stresses that he doesn’t just mean using obscure words in a pretentious manner. He means taking more care than normal to express our ideas very clearly.

But, as I said at first, there lies a great danger in the enterprize lest the word be applied unsuitably or with a want of clearness or a lack of refinement, as by a man of half-knowledge, for it is much better to use common and everyday words than unusual and far-fetched ones, if there is little difference in real meaning. — Fronto

Of course, anyone can do this. However, most of us fall into the habit of over-using the most common words and phrases. These don’t hold our attention or stimulate the imagination, though, and a more careful choice of words can allow our meaning to ring out more loudly and clearly. A master rhetorician like Fronto would invest a great deal of his life in the process of refining his vocabulary in this way.

Fronto’s Method: Making Paradoxes IntelligibleI hardly know whether it is advisable to shew how great is the difficulty, what scrupulous and anxious care must be taken, in weighing words, for fear the knowledge should check the ardour of the young and weaken their hopes of success. — Fronto

Although Marcus trained extensively in rhetoric, for many years, he became progressively more drawn toward the study of philosophy. Fronto obviously considered Marcus to be a very gifted student. He’s very concerned about the risk of losing him to philosophy. He therefore likes to remind Marcus that rhetoric and philosophy should be viewed as complementary disciplines. Philosophers need to know how to express their ideas powerfully and clearly.

Nor, in my opinion, can philosophers dispense with such artifices any more than orators. — Fronto

CC0 1.0 Universal, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

CC0 1.0 Universal, courtesy of Wikimedia CommonsHe tells Marcus repeatedly to paraphrase philosophical maxims, and other wise sayings, perhaps such as the quotes from Greek poets that we find in The Meditations alongside sayings from Socrates, Epictetus, and others.

You must turn the same maxim twice or thrice, just as you have done with that little one. And so turn longer ones two or three times diligently, boldly. — Fronto

Marcus enjoys these exercises but sometimes finds them hard work.

Now, if never before, I find what a task it is to round and shape three or five lines and to take time over writing. — Marcus Aurelius

Fronto explains to Marcus that he pushed him to find the right words to express himself clearly precisely because of his philosophical nature. Even as a young man, Marcus was wrestling with profound ideas, which are not easily expressed in plain English, or even plain Greek or Latin.

You had, [Marcus] Antoninus, but one danger to fear, and no one of outstanding ability can escape it — that you should limp in respect of copiousness and choiceness of words. For the greater the thoughts, the more difficult it is to clothe them in words, and no small labour is needed to prevent those stately thoughts being ill-clothed or unbecomingly draped or half-naked. — Fronto

Socrates and the Stoics were famous for their paradoxes, a word which literally means “contrary to (popular) opinion” in Greek. We have whole lists of words that we’re told the Stoics were at pains to explain were being used in a novel and technical sense — different from the way they were normally used. For instance, Diogenes Laertius, one of our main sources for early Stoic teachings struggles to explain the following distinction:

Now they [the Stoics] say that the wise man is “passionless” [has apatheia], because he is not prone to fall into [passions]. But they add that in another sense the term “apatheia” is applied to the wretched man, when, that is, it means that he is hard and unrelenting. — Diogenes Laertius

Or to put it more simply, they mean that the goal of Stoicism is to be self-possessed and free from unhealthy emotions but not to be cold-hearted or unemotional as though our hearts were made of stone. Philosophers are experts at making subtle conceptual distinctions and working out their implications. Rhetoricians, however, are experts at explaining ideas more clearly so that we can better understand what is meant.

Fronto refers — in Greek, the language of philosophy—to the problem of handling “new and paradoxical ideas” or arguments. This passage, in particular, could easily be viewed as describing the approach followed by Marcus in writing The Meditations.

I warn you, therefore, again and again, my Marcus, and beseech you to remember, as often as you conceive in your mind a startling thought, think over it with yourself and turn and try it with various figures of speech and dress it out in splendid words. For there is a danger that what is new to the hearers and unexpected may seem ridiculous unless it be embellished and made figurative. — Fronto

Fronto has no problem using unusual words or phrases, as long as the audience understand them. However, he feels very strongly that radical new ideas, such as the paradoxes of Stoicism, will confuse people and be misunderstood unless philosophers learn to take more care and express them clearly. Fronto was concerned that Marcus, given his position as Caesar, and later as emperor, needed to be especially careful in this regard.

Speaking the TruthIf we didn’t know this, it would perhaps come as a surprise to find that Marcus praises Fronto, a Sophist, for teaching him how to put the truth into words.

It is that I learn from you to speak the truth. That matter (of speaking the truth) is precisely what is so hard for gods and men: in fact, there is no oracle so truth-telling as not to contain within itself something ambiguous or crooked or intricate, whereby the unwary may be caught and, interpreting the answer in the light of their own wishes, realize its fallaciousness only when the time is past and the business done. — Marcus Aurelius

Again, although it’s difficult enough to grasp the truth ourselves, if we wish to share our wisdom with others that’s even more hard work.

Interestingly, although Fronto tells Marcus to paraphrase the same philosophical maxims repeatedly as an intellectual exercise he nevertheless thinks that to do so in a speech or essay is obnoxious. In fact, he’s absolutely eviscerates Seneca for having done so.

You will say, there are certain things in his [Seneca’s] books cleverly expressed, some also with dignity. Yes, even little silver coins are sometimes found in sewers; are we on that account to contract for the cleaning of sewers? The first and most objectionable defect in that style of speech is the repetition of the same thought under one dress and another, times without number. — Fronto

In Marcus’ case, though, we find something else. We find him struggling with the same ideas over and over again in The Meditations, rephrasing them in different ways, not for the sake of others but for his own sake. The approach Fronto taught him, of finding exactly the right words by repeatedly paraphrasing maxims, has become a method of rendering Stoic wisdom clearer, more impactful, and more memorable, in the privacy of his own mind. Indeed, “The Meditations” was the title given to Marcus’ notes by modern editors. The earliest manuscript version was titled in Greek: To Himself.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

February 9, 2023

Anya Leonard on Why Classics Matter Today

In this episode, I chat with Anya Leonard. Anya is the founder and director of Classical Wisdom, a website and online community dedicated to bringing ancient wisdom to modern minds. She also recently published a children’s book about the ancient Greek poetess, called Sappho: The Lost Poetess.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

HighlightsHow Anya got into the classics

Why she chose to write a children’s book about Sappho

Why are classics are important today

Should only boffins talk and write about classics

What obstacles do we face teaching people about classics?

What is Classical Wisdom Kids?

LinksCheck out Anya’s Substack newsletter

And her newnewsletter

Get her book Sappho: The Lost Poetess

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

February 6, 2023

Stoicism for Children

Stoicism has exploded in popularity over the past couple of decades. One of the questions I’m now asked most frequently, by teachers and parents, is whether there are any good resources available to help kids learn about Stoic philosophy. The answer is YES, although you may need helping finding them.

You can demonstrate Stoic philosophy in action quite easily by using what psychologists call the “thinking aloud” technique…

Basic Lessons

Basic LessonsThere are many aspects of Stoicism that you could discuss with children but it makes sense to start by focusing on some basic principles. You can demonstrate Stoic philosophy in action quite easily by using what psychologists call the “thinking aloud” technique. This is a form of “cognitive modelling” which lets you show your children how you, the parent, might use simple Stoic ideas to guide your own decisions. For example:

Some things are up to us and others are not, which you can demonstrate simply by asking of some challenging event “What aspects are up to me?” or “What can and can’t I control about this situation?”

It’s not things that upset us but rather our opinions about them, which you can model by asking “How might other people view this situation differently?” or “What would be a better way of looking at this whole thing?”

The Stoics taught that it’s better to lead by example than through books and lectures, although there’s a place for both. Kids can’t read your mind, though, so the “thinking aloud” technique can be a useful way to provide a window on your thought processes. That lets you model a healthy way of tackling a problem, which you’d like your kids to gradually learn. This should be done as naturally as possible, of course, so demonstrating a little bit at a time, over a long period, perhaps works best if you’re a parent or teacher.

Stoic Books for TeensReading books can also help, of course. I began teaching my daughter about Greek philosophy, including Stoicism, when she was about five years old. Young children will probably find it difficult to pick up one of the classic texts on Stoicism and just start reading. However, certain older teens, depending on their ability and interests, might have no problem reading the more accessible texts.

Most adults begin by reading The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius. Make sure you get a modern translation, though. Most of the cheap or free editions are public domain translations, which are very old now, e.g., from the Victorian era. Good modern translations are available by Gregory Hays, Robin Hard, and Robin Waterfield, which teens will find easier to read. Sharon Lebell’s The Art of Living is a paraphrase of the Discourses of Epictetus in plain English, which is quite easy to read. Don’t forget about audiobooks! Most of these books are available in audio format, which can be more appealing to some teenagers.

Stoic Books for Younger ChildrenFirst of all, I introduced my daughter to Greek philosophy by first teaching her about Greek mythology. She loves the Percy Jackson movies, and those books are also very popular with teens. There are lots of great kids’ books available on Greek mythology. Poppy particularly liked the Early Myths series by Simon Spence. Her favourite Greek legends are about Hercules and she’s heard them hundreds of times!

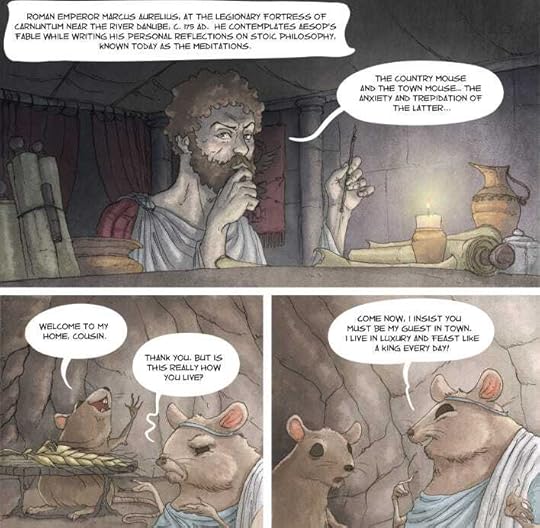

Aesop’s Fables are also very popular with young children, and many have moral and philosophical messages. For example, Marcus Aurelius actually mentions Aesop’s fable of the Town Mouse and the Country Mouse, and Seneca seems to allude to the fable of The Farmer and the Viper. As for books more focused on Greek philosophy, the classicist M.D. Usher has written two beautifully illustrated children’s books on Diogenes the Cynic (called Diogenes) and Socrates (called Wise Guy), which my daughter loved reading with me.

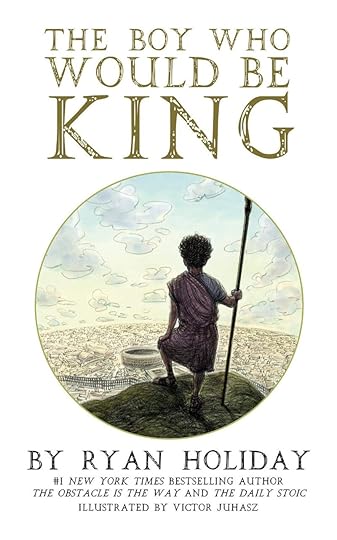

Socrates and the Cynics were important precursors of Stoicism. If you’re looking for something even more Stoic, though, Ryan Holiday has an illustrated children’s book about Marcus Aurelius called The Boy Who Would be King. This is a lovely book with beautiful artwork. I think it’s suitable even for very young children, especially if they read it with an adult. It’s a short story about the moral lessons Marcus Aurelius learned as a child from his Stoic tutor, Junius Rusticus.

Cover of The Boy who Would be King by Ryan Holiday

Cover of The Boy who Would be King by Ryan HolidayFor very young children, there’s also the Little Stoics series by Jason Valenstein.

Stoic Reading for ParentsAs we discussed earlier, though, kids don’t just learn Stoicism from books. The best way to teach them is by modelling Stoic attitudes and behaviours yourself, as their parent. Brittany Polat has an excellent book called Tranquillity Parenting, which draws upon Stoicism to provide “timeless truths for becoming a calm, happy, engaged parent.” Brittany also runs a Facebook group called Stoic Parents, where you can discuss parenting and find other resources for teaching Stoicism to kids.

Excerpt from webcomic about Marcus Aurelius and Stoicism, copyright Donald J. RobertsonStoic Comics and Graphic Novels

Excerpt from webcomic about Marcus Aurelius and Stoicism, copyright Donald J. RobertsonStoic Comics and Graphic NovelsA few years ago, I created a series of three short webcomics about Marcus Aurelius. Each one is based on one of Aesop’s Fables. They’re meant for adults, but can be read even by younger children. That eventually led to me writing Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, our graphic novel about the Stoicism, with artwork by award-winning Portuguese illustrator Zé Nuno Fraga. This is meant for adults. I think it might be too violent, or too philosophical, for some younger children. However, I think most teenagers would enjoy reading it. The comic book format seems to serve as a great introduction to philosophy.

cover of Verissimus graphic novel, by Donald J. Robertson

cover of Verissimus graphic novel, by Donald J. RobertsonAs soon as we started talking about the graphic novel, we were flooded with requests from parents and teachers who wanted to know if it would be suitable for kids. So we created a short PDF handbook called , which could be downloaded and used by anyone. It’s intended to be helpful as a teaching aid, but can be read simply as an introduction to Stoicism.

What Next?It’s Father’s Day here, in the US, as I write this article, and I’m about to call my daughter, who’s in Canada. I’ll ask her advice about teaching Stoicism to kids. One of the most helpful things I’ve learned, as a parent, is that it can be helpful just to talk to my daughter about emotions and the best way to cope with them. Of course, when someone is upset, that can be difficult. So either do it in advance, anticipating future challenges, or wait until a crisis has passed, and everyone has calmed down. “What do you think would be a better way of dealing with that if it happens again?”, is often a good question.

I’d love to hear about your strategies, though, and let me know of any other good resources you’ve found for teaching kids about Stoicism, or Greek philosophy in general. Please post your comments and I’ll try to update the article with anything important you think I may have missed.