Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 32

May 4, 2023

Withdraw your desire from what is not up to you…

Comment

Remember that the promise of desire is the attainment of what you desire, that of aversion is not to fall into what is avoided, and that he who fails in his desire is unfortunate [i.e., feels he misses out on good fortune], while he who falls into what he would avoid experiences misfortune.

If, then, you [seek to] avoid only what is unnatural [i.e., unhealthy] among those things which are under your control, you will fall into none of the things which you [seek to] avoid; but if you try to avoid disease, or death, or poverty, you [cannot and so] will [feel as though you] experience misfortune. Withdraw, therefore, your aversion from all the matters that are not under our control, and transfer it to what is unnatural [i.e., unhealthy] among those which are under our control.

But for the time being remove utterly your desire; for if you desire some of the things that are not under our control you are bound to [fail to achieve them sometimes and so] be unfortunate; and, at the same time, not one of the things that are under our control, which it would be excellent for you to desire [i.e., perfect wisdom and virtue], is within your grasp. But employ only choice and refusal, and these too but lightly, and with reservations, and without straining. — Epictetus, Enchiridion 2, italics and paragraph breaks added

The Stoics believe that when we judge something to be intrinsically good we naturally desire it and commit ourselves to the wish that we should attain it. On the other hand, when we judge something bad or harmful we develop an aversion and desire to avoid it. When our desires and aversions are thwarted our lives go badly so we should be careful what we wish for. As this is inevitable, given that nothing external is completely under our control, we must learn to manage our desires and aversions if we want to flourish, and for our lives to go smoothly.

Stoics don’t judge external setbacks in a strongly negative way because they would be setting themselves up for failure insofar as these aren’t under their direct control.

Stoics focus on avoiding doing things under their direct control badly, or viciously, something they should always be able to achieve. They don’t judge external setbacks in a strongly negative way because they would be setting themselves up for failure insofar as these aren’t under their direct control.

May 2, 2023

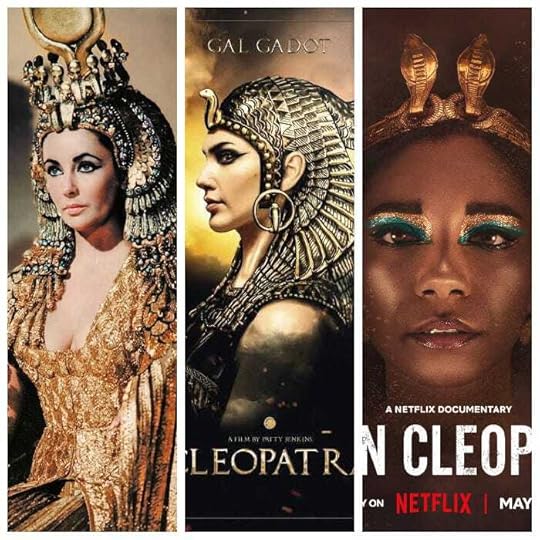

How Pale was Cleopatra's Skin?

You’ve probably heard by now that Netflix are releasing a historical documentary about Cleopatra, produced and narrated by Jada Pinkett Smith, in which the famous Egyptian ruler is portrayed by Adele James, a black English actor. The documentary engages with a long-running historical debate known as the Cleopatra Race Controversy by showing a woman in the trailer who says:

I remember my grandmother saying to me, 'I don't care what they tell you in school, Cleopatra was Black.’

Accusations of “blackwashing” were made by many people, particularly in Greece and Egypt, who pointed out that, to the best of our knowledge, Cleopatra was a white European woman of Macedonian (Greek) descent. I doubt there would have been a heated response if a black actor was cast as Cleopatra in Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, or any work of historical fiction, but we’re talking here about a historical documentary. Complaints were mainly about it being misleading and pseudohistorical. Netflix responded to them by turning off the YouTube comments under the trailer.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

She truly was one of the most amazing women in history...

I want to make it clear from the outset, though, that I decided to write about this not because of the politics of race but because, as you’ll see, I think the discussion has overlooked an interesting fact about the significance of skin color in the ancient world, which did not typically have to do with race. I’m mainly interested in what Cleopatra looked like because I’ve written several ancient biographies, including a graphic novel, Verissimus, for which, of course, it was necessary for me to carefully study details such as the ethnicity and physical appearance of historical figures.

I think the recent furor may actually have had some positive effect if it’s encouraged people to think more deeply about the historical evidence related to the life of Cleopatra. I doubt many non-academics realized, to be honest, that she was a descendant of one of Alexander the Great’s generals, until they heard about these controversies. She died, in part, because while some Romans envied her power, others were threatened by her. She truly was one of the most amazing women in history, and she deserves our attention.

Who was Cleopatra?

Who was Cleopatra?Alexander the Great conquered a colossal empire, in the fourth century BCE, spanning Greece, Egypt, Asia Minor, and Persia. Embarking from his homeland in Macedonia, he fought his way across the world to Afghanistan and Pakistan before dying aged only thirty-two, without designating an heir. His empire immediately fragmented and was claimed by several Macedonian generals who became his successors. Alexander founded dozens of cities named Alexandria, after himself. The most important of these became the capital of Egypt during the Hellenistic era, when Greek culture spread through the kingdoms ruled by his successors, and the Greek language became their lingua franca. Egypt was claimed by one of Alexander’s Macedonian generals, Ptolemy I Soter, and ruled for generations by the dynasty he founded. Around 230 years after the first Ptolemy’s demise, Cleopatra, his descendant, became the last pharaoh to rule Egypt.

Although she was the only Ptolemaic ruler to learn the Egyptian language, her first language was Greek. Her name, Κλεοπάτρα, is Greek, and was handed down through her family, although one of the very earliest references to it belongs to Alexander’s sister, Cleopatra of Macedonia. Our Cleopatra lived in a city named after Alexander, where his tomb was still one of the most important religious shrines in the ancient world. When the victorious Octavian (who became the first Roman emperor, Augustus) arrived in Alexandria, to depose Cleopatra, he pardoned its citizens, in part, because of his admiration for Alexander, whose tomb he immediately requested to visit.

The speech in which he [Octavian] proclaimed to them [the citizens of Alexandria] his pardon he delivered in Greek, so that they might understand him. — Cassius Dio

In other words, the first language of Alexandria, under Cleopatra, was still Greek. She presided over the Great Library of Alexandria, a treasurehouse of ancient Greek texts. Alexandria was a highly cosmopolitan city, the three main ethnic groups being native Egyptians, the Jews (like Gal Gadot), and the Greeks, from which group the Ptolemaic ruling class came. Cleopatra was clearly very proud of, and closely-identified with, her Greek ancestry and heritage. If you were directly descended from one of Alexander the Great’s generals, you’d probably want everyone to know about it, right?

Bronze coin believed to depict Cleopatra, minted during her reign

Bronze coin believed to depict Cleopatra, minted during her reignThere’s no historical evidence to suggest that she was black or, indeed, that she had any Sub-Saharan African, or even native Egyptian, ancestors. (There’s also no evidence to support Netflix’s claim that the children she had with Julius Caesar and Mark Antony were mixed race.) As we’ll see, the images that have been identified as depicting her are white and have been described as exhibiting European features. It’s still theoretically possible that Cleopatra was black but, in my opinion, and that of most historians, it’s extremely unlikely.

The Roman poet Lucan, born 70 years after she died, actually refers to her pale complexion:

Cleopatra wears a fortune and she strains beneath her finery. Her white breasts [candida pectora] shine through the Sidonian thread… — Lucan, Pharsalia, my italics

The Latin word he uses, candidus, is the root of our English words “candle” and “incandescent”, it means pure-, brilliant- or snow-white.

She seems to me to have very strongly identified with her Greek heritage and, based on surviving depictions, she was probably a pale-skinned woman with a large, possibly quite aquiline, nose, big eyes, and reddish-brown hair, which is usually neatly braided. She is always shown with the Macedonian royal diadem, a linen ribbon woven with gold thread bearing a jewel in the center, worn by Hellenistic (Greek) monarchs since the time of Alexander.

The Director’s ArgumentThe director of Queen Cleopatra, Tina Gharavi, responded to the criticism of her documentary’s trailer in an article for Variety titled ‘What Bothers You So Much About a Black Cleopatra?’ She writes, “Cleopatra’s heritage has been attributed at one time or another to the Greeks, the Macedonians and the Persians.”

1st century CE bust of a younger Cleopatra, originally had the hair painted red. / 1st century CE portrait believed to be Cleopatra, with pale skin and red hair

1st century CE bust of a younger Cleopatra, originally had the hair painted red. / 1st century CE portrait believed to be Cleopatra, with pale skin and red hairThe ancient Macedonians were Greeks, as Gharavi seems to acknowledge later in the article. The “Persians” she’s talking about were Seleucid rulers, descended from another of Alexander’s generals, Seleucus I Nicator — who was Macedonian, and therefore a Greek.

The known facts are that her Macedonian Greek family — the Ptolemaic lineage — intermarried with West Asian’s Seleucid dynasty and had been in Egypt for 300 years. Cleopatra was eight generations away from these Ptolemaic ancestors, making the chance of her being white somewhat unlikely. After 300 years, surely, we can safely say Cleopatra was Egyptian. She was no more Greek or Macedonian than Rita Wilson or Jennifer Aniston. Both are one generation from Greece. Doing the research, I realized what a political act it would be to see Cleopatra portrayed by a Black actress.

This seems like an odd argument. Nobody has ever denied that Cleopatra was Egyptian, in the sense that she was born in Egypt. However, she clearly identified ethnically with Greek culture. The controversy, though, was about what she looked like, and who her ancestors were. The Ptolemies are believed mainly to have married their own relatives and other nobles of Greek descent, including those from the Seleucid Empire, another Hellenistic kingdom to the east. It’s likely that Cleopatra had mainly Greek ancestors, and perhaps a few of Persian descent. In any case, we have what are believed by experts to be depictions of her in paintings, which portray her as a pale-skinned woman with reddish-brown hair; and we have coins and sculpture, which portray her in the same Hellenistic attire and with the same typical Mediterranean features.

1st century BCE (contemporary) Roman painting believed to depict Cleopatra and Caesarion, her son with Julius Caesar

1st century BCE (contemporary) Roman painting believed to depict Cleopatra and Caesarion, her son with Julius Caesar After much hang-wringing [sic.] and countless auditions, we found in Adele James an actor who could convey not only Cleopatra’s beauty, but also her strength. What the historians can confirm is that it is more likely that Cleopatra looked like Adele than Elizabeth Taylor ever did.

I don’t think most historians would actually agree with this statement. Elizabeth Taylor probably didn’t look much like Cleopatra, but not because of her skin color. As we’ll see, the real Cleopatra was most likely even paler skinned than Elizabeth Taylor.

Egyptians accused me of “blackwashing” and “stealing” their history. […] Amir in his bedroom in Cairo wrote to me to earnestly appeal that “Cleopatra was Greek!” Oh, Lawd! Why would that be a good thing to you, Amir? You’re Egyptian. So, was Cleopatra Black? We don’t know for sure, but we can be certain she wasn’t white like Elizabeth Taylor. We need to have a conversation with ourselves about our colorism, and the internalized white supremacy that Hollywood has indoctrinated us with. Most of all, we need to realize that Cleopatra’s story is less about her than it is about who we are.

Why should it matter whether the director thinks it’s a “good thing” for Amir? (Especially if he doesn’t agree!) Surely, for a historical-documentary maker, what matters more is the truth, i.e., whether or not it’s more accurate to portray Cleopatra as a woman of Greek or Sub-Saharan African descent?

It was also noted by many of the director’s critics that, in the article above, she says her main reason for casting a black actress as Cleopatra was “political”, rather than historical. Many people pointed out in response, though, that she could have chosen an African ruler who was actually believed by historians to have been black if she wanted to provide a role model from history for African Americans. As it happens, an earlier Egyptian dynasty, unrelated to Cleopatra and the other Ptolemies, known as the Kushite Empire, probably consisted of black rulers from Northern Sudan.

The Egyptian PerspectiveThe Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Archeology responded to the Netflix trailer with an official statement. It says that the Secretary General of the Supreme Council of Archeology in Egypt, Dr. Mustafa Waziri, “confirms that Queen Cleopatra was light-skinned with Hellenic (Greek) features.” The works of art and statues depicting Cleopatra provide, it says, the “best evidence of her true features and Macedonian origins.”

Dr. Waziri adds that the physical appearance Cleopatra in the Netflix docuseries “is a falsification of Egyptian history and a blatant historical misconception, especially as the film is classified as a documentary and not a drama”. The show’s producers should therefore be obliged to confirm its historical accuracy “and refer to historical and scientific facts in order to ensure that the history and civilizations of peoples is not falsified.”

Dr. Waziri stresses the existence of many relevant “artifacts and depiction on coins” that all confirm “Cleopatra's Hellenic (Greek) features, in terms of light complexion”, and the shape of her nose and lips. In addition to these sources of evidence from the archeological record, the official Egyptian government statement goes on to cite DNA studies, and hair, skin, and bone analyses that contradict the depiction of Cleopatra in Netflix’s documentary.

Did Ancient Greek Women Sunbathe?Now for the point that I think is missing from the discussion. I believe that Cleopatra probably had much paler skin than Elizabeth Taylor, for the following reason… Whereas modern European women often sunbathe, most ancient Greek, Roman, and Egyptian women, as far as we know, did not. Indeed, women of status in these ancient cultures were particularly known for having pale white skin, which they deliberately cultivated by avoiding exposure to the sun.

Skin color, in other words, was often more an indicator of gender than race, as far as ancient Greeks and Romans were concerned.

Men, by contrast, had darker-tanned skin than most of us today, because they spent more time outdoors, either working or exercising. Dark skin was typically considered a sign of masculinity whereas white skin was considered feminine. Aristophanes, for example, mocks certain Athenian philosophers, and Xenophon mocks certain Persian soldiers, for being pale skinned and effeminate. Skin color, in other words, was often more an indicator of gender than race, as far as ancient Greeks and Romans were concerned.

Women who had tanned skin looked as though they worked outdoors, which was deemed a sign of low status. Female slaves and prostitutes might be tanned but noblewomen were typically extremely pale skinned. In modern English, we still use the idiom “blue-blooded” to refer to someone of noble birth. This comes from the notion that European aristocrats, until quite recently, had a reputation for being pale-skinned, from lack of exposure to the sun. Their blue veins were more visible than normal under their pallid skin. One late Roman source, likewise, describes the Emperor Marcus Aurelius as having “diaphanous” or transparent skin.

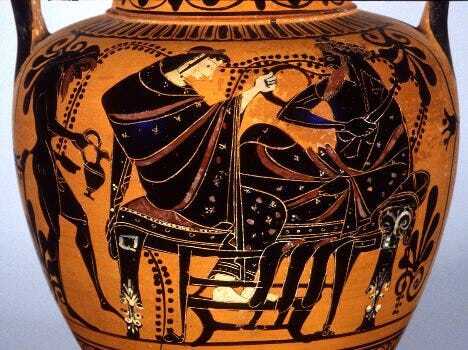

In Greek theatre, the masks of male characters were typically painted brown, whereas those of women were painted white. We often find a similar convention in ancient ceramics, where female figures are clearly distinguished from males, by giving them white and black skin respectively.

2nd century CE Roman mosaic, depicting female and male theatrical masks

2nd century CE Roman mosaic, depicting female and male theatrical masksThis distinction is also alluded to in ancient literature. For example, Andrea Sinclair’s Unmasking Ancient Colour, discusses the evidence found in a 2nd century CE text, the Onomasticon of Julius Pollux, which describes the appearance of theatrical masks.

Gender distinction is consistent with Greek artistic convention and is characterised by the use of dark and light skin tones. Thus, a male character will have a darker complexion than a female, whose ideal colouring was white, no doubt from a notion of seclusion in the domestic environment (but this may apply more to women of higher social standing).

Indeed, the only female mask that Pollux describes as non-white depicts the ruddy face of an ageing prostitute.

Greek ceramic showing Ariadne (female) as pale skinned and Dionysus (male) as dark-skinned.

Greek ceramic showing Ariadne (female) as pale skinned and Dionysus (male) as dark-skinned.I’ve not seen this fact mentioned in any of the recent discussions concerning the depiction of Cleopatra, except in the recent Egyptian government statement. Dr. Nasser Mekkawy, Head of the Egyptian Department of Archeology, Cairo University, is quoted as saying that when later generations began coloring the skin of mummified corpses to resemble their appearance during life, “they painted the man's skin in brown color and the woman's skin in light yellow.”

The director of Queen Cleopatra made several claims such as “What the historians can confirm is that it is more likely that Cleopatra looked like Adele [James] than Elizabeth Taylor ever did.” However, if Cleopatra was predominantly of Greek descent, perhaps with some Seleucid ancestors, it’s likely she would have deliberately cultivated a pale complexion like other Greek and Roman noblewomen. Perhaps they did this by wearing makeup but they also avoided exposure to the sun because they considered it a sign of low social-status for women to have darkly-tanned skin. Indeed, we can easily see that the paintings historians believe to be of Cleopatra depict her as much paler-skinned than Elizabeth Taylor was in the movie.

Liz Taylor as Cleopatra, with tanned skin unlike paintings of the Egyptian queen Conclusion

Liz Taylor as Cleopatra, with tanned skin unlike paintings of the Egyptian queen ConclusionCLEOPATRA: I am pale, Charmian. — Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra

I don’t have strong opinions about the politics of race with regard to the casting of historical figures like Cleopatra, although I do believe that such documentaries should be as historically accurate as possible. Often we simply cannot be certain about details such as the skin color of specific individuals as far back in history as the first century BCE. However, in the case of Cleopatra, as the Egyptian ministry confirmed, there’s sufficient evidence for us to say that she was probably a pale-skinned woman with typical Mediterranean features. She certainly identified deeply with her Greek ancestry, culture, and ethnicity, given her status as the ruler of such an important Hellenistic kingdom.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

What’s of more interest to me is the general point that skin color was often used as an indicator, not of race, but of gender, in Greek and Roman society. Modern Greek women frequently sunbathe, and enjoy relaxing on the beach, but ancient Greek woman did not, and actually avoided getting a tan. Paleness was strongly associated with femininity, but also with nobility, or social status. Rich aristocrats, the blue-blooded elite, did not toil in the fields under the blazing sun, and, for the most part, they wanted everyone to see that they were above such things.

It’s a common misconception that ancient Greek and Roman women were tanned, therefore, when, in fact, they, especially the aristocracy, appear to have been significantly paler than modern Mediterranean women — we can see as much from their depiction in mosaics and paintings. Knowing this can help us to understand certain social differences between men and women, or the rich and the poor, in the ancient world.

April 27, 2023

Philosophy as a Way of Life with Matthew Sharpe

In this episode, Donald talks with Matthew Sharpe. Matt is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Deakin University in Australia. He’s spoken at Stoicon in Athens. He is the co-author of Philosophy as a Way of Life, and one of the translators of The Selected Writings of Pierre Hadot: Philosophy as Practice. His most recent book is titled Stoicism, Bullying, and Beyond: How to Keep Your Head When Others Around You Have Lost Theirs and Blame You.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

HighlightsStoicism and Philosophy as a Way of Life

Why isn’t Stoicism more popular in academia?

Pierre Hadot and Stoicism

Philosophy and Spiritual Exercises

Philosophy and the History of Psychotherapy

Anger, Self-Estrangement, and Politics

The French Enlightenment and Philosophy as a Way of Life

LinksMatthew Sharpe Profile at Deakin University

Stoicism, Bullying, and Beyond

The Other Enlightenment: Race, Sexuality and Self-Estrangement

The Selected Writings of Pierre Hadot

Philosophy as a Way of Life: History, Dimensions, Directions

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

April 26, 2023

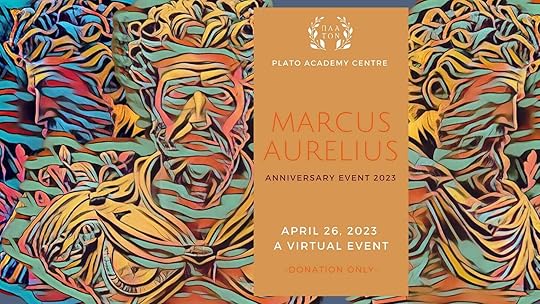

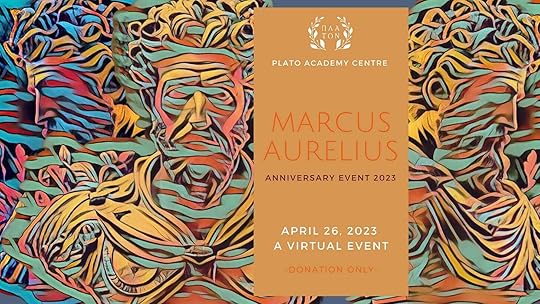

Last Chance: Marcus Aurelius Anniversary Event

Today we are holding a unique event — one I’ve been looking forward to for a long time! You will hear three authors who have recently written books on Marcus Aurelius, discussing his life and philosophy, and answering (your) questions from the audience. Everyone is welcome, registration is free, although donations for nonprofit are appreciated.

Are you in another timezone? Don’t worry. The event is at 2pm EDT today but if you register now you’ll be sent a link to the recording afterwards, to play back at your leisure. Come along and join us! We’re looking forward to hearing all of your questions about the life and philosophy of Marcus Aurelius.

Speakers

SpeakersDr. John Sellars, author of Marcus Aurelius, Routledge's Philosophy in the Ancient World series

Donald Robertson, author of How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius

Prof. William O. Stephens, author of Marcus Aurelius: A Guide for the Perplexed

Hosted by Anya Leonard of Weekly.

April 24, 2023

The 10 Most Surprising Facts about Marcus Aurelius

In this article, I discuss ten little-known facts about Marcus Aurelius. But first… If you’re interested in Marcus Aurelius, check out our special online event to commemorate the anniversary of his birth, on 26th April. Three authors who have written books about Marcus Aurelius will be discussing his life and philosophy together and answering questions from the audience. Register now and you’ll be able either to watch live or get access to the recording later.

I have spent a lot of time researching Marcus Aurelius. I first read his notes about applying Stoic philosophy to daily life, the Meditations, one of the most cherished philosophical and self-help classics of all time, over 25 years ago. Since then, I’ve written six books on Stoicism — three in a row have been about the life of Marcus Aurelius! The first was a self-help book, based on vignettes from his life, called How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, the most recent was a prose biography of him for Yale University Press, and between them came a graphic novel called Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, from which the illustrations in this article are borrowed. Here are some of the most interesting things I learned during my research…

1 Marcus led a dance troupeAs a young boy, Marcus was appointed to several important positions due to the influence of the Emperor Hadrian. One of them was the College of the Salii or leaping priests, a Roman religious order supposedly founded by the legendary King Numa, from whom Marcus’ family claimed descent. The Salii recited obscure chants and performed an athletic military dance, bearing archaic shields and spears, in honor of Mars, the god of war. These rituals were meant to train youths for the physical exertions of battle.

Artwork from Verissimus, copyright Donald J. Robertson, reproduced by permission.

Artwork from Verissimus, copyright Donald J. Robertson, reproduced by permission.When Marcus refers to dancing in the Meditations, therefore, he’s drawing on a wealth of experience, which makes his comments much more personally meaningful. For example, being well-acquainted with both wrestling and dancing, he wrote:

The art of life is more like the wrestler’s art than the dancer’s, in respect of this, that it should stand ready and firm to meet onsets which are sudden and unexpected. — Meditations, 7.61

Marcus appears to have relished his training in dance, though, and eventually went on to become the leader of the Salii.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

2 Marcus enjoyed toilet humorIn the Meditations, Marcus reflects on the evolution of Greek tragedy into Old Comedy, with its “magisterial freedom of speech,” which he says inspired Diogenes the Cynic. Marcus felt the art of comedy had gradually declined, though, into something trivial (Meditations, 11.6). In other words, he believed that old-fashioned cynical humour could serve a moral purpose.

Elsewhere, for instance, he illustrates a series of philosophical musings about the superficial nature of material wealth by quoting a scatalogical joke from the poet Menander, a representative of New Comedy, who nevertheless appeals to Marcus. It concerns a rich man who has so many possessions that there’s nowhere left for him to empty his bowels (Meditations, 5.12).

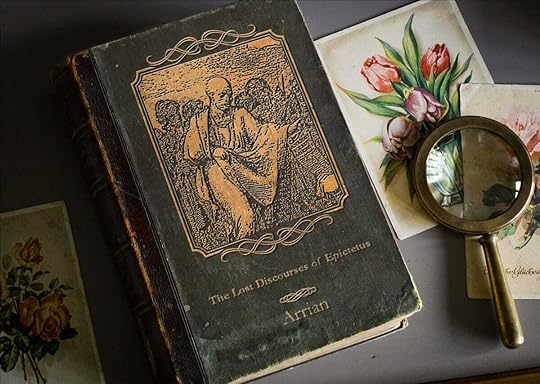

3 Marcus may have read lost books by EpictetusThe philosopher Marcus quotes most frequently is the Stoic Epictetus, who died in Greece when Marcus was still a boy at Rome, so they appear to have narrowly missed the opportunity to meet one another. Marcus tells us that his main Stoic tutor, Junius Rusticus, gave him a set of notes from Epictetus’ lectures from his own private collection (Meditations, 1.7). As Marcus quotes several times from the Discourses of Epictetus that survive today, it’s very likely those are the texts to which he’s referring.

One ancient source tells us there were originally eight volumes of Epictetus’ Discourses whereas only four survive today…

One ancient source tells us there were originally eight volumes of Epictetus’ Discourses whereas only four survive today — half of them, in other words, are lost. Marcus, however, also quotes sayings of Epictetus that are otherwise unknown to us today, so it’s possible he had actually read the four missing volumes of Epictetus’ Discourses. Moreover, Arrian, the student who transcribed and edited the Discourses, says that originally they were circulated in private, and were not known to the public until a later date. When Marcus stresses that Rusticus gave him a copy from his private collection he may be referring to the fact that, at the time, the very existence of these scrolls was still a closely-guarded secret!

Artwork from Verissimus, copyright Donald J. Robertson, reproduced by permission.4 Marcus had reservations about Seneca

Artwork from Verissimus, copyright Donald J. Robertson, reproduced by permission.4 Marcus had reservations about SenecaNone of the surviving writings from the Stoics who came after Seneca mention his name. Marcus never mentions Seneca in the Meditations, although Seneca was very famous as Emperor Nero’s Latin rhetoric tutor, who later became his speechwriter and most senior advisor. This could be because Roman authors who write in Greek, like Marcus, tend not to cite those who wrote in Latin, like Seneca. However, we know that Marcus had read Seneca’s writings because of a cache of letters between Marcus and his own rhetoric tutor, Marcus Cornelius Fronto.

Fronto mentions Seneca several times. Although they had much in common, as Latin rhetoric tutors to emperors, Fronto seems to despise Seneca’s writings. At one point he goes so far as to say that searching for wise sayings in Seneca’s writings would be like grubbing around in the filth at the bottom of a sewer, just to retrieve a few silver coins! Frustratingly, we do not possess the letters in which Marcus responds to these comments but it’s clear from Fronto’s letters that Marcus had read Seneca, and was perhaps defending him, at least to some extent. It’s possible that they were more familiar with Seneca’s political speeches, rather than the Moral Letters he is best known for today. See, for example, Seneca’s On Clemency, where he portrays Nero as a virtual philosopher king, insisting, somewhat brazenly, that the hands of the emperor, who had recently murdered his younger brother, Britannicus, were free from any stain of blood.

There’s a passage in the Roman historian Cassius Dio suggesting that Thrasea, the leader of the Stoic Opposition against Emperor Nero, made it known that Seneca should be subjected to damnatio memoriae, the Roman practice of eliminating someone’s name from history. While these men risked their lives opposing Nero’s tyranny, Seneca was assisting him, and defending his actions in the Senate. Epictetus, who was originally the slave of Nero’s Greek secretary had a ringside seat for the scandal that engulfed Seneca. He viewed Thrasea’s circle of Stoics as moral examplars, and may therefore have omitted mention of Seneca out of respect for them. Marcus mentions that he views Nero as a tyrant ruled by animal-like passions, so he may have followed Epictetus in distancing himself from Seneca for that reason.

5 Marcus was opposed by a faction of enemies at RomeThis is clear from the fact that he faced a civil war in 176 CE, led by his most senior general in the east, Avidius Cassius. However, Cassius did not act alone. He commanded seven legions, each of which was led by officers, including generals who would normally be of the senatorial class. He appointed his own praetorian prefects and cohorts, or personal bodyguard. He was also supported by the prefect of Egypt, the most important province in the empire. Our sources make it clear that a number of senators and other officials were involved in the faction supporting Cassius’ rebellion against Marcus.

The reasons for the civil war are unclear but the faction opposing Marcus appear to have been military hawks who felt that his handling of the protracted war along the Danube frontier had placed too much emphasis on diplomacy — Marcus was too much of a military dove or peacemaker for their liking. However, the rebellion only lasted a few months and Cassius was eventually assassinated by his own officers.

There are also several pieces of gossip critical of Marcus and his family reported in the Roman histories. Several of them, on close inspection, seem designed to cast doubt on the legitimacy of his son Commodus. For example, it was rumored that the Empress Faustina was unfaithful, and slept with sailors and gladiators. One obvious explanation was that these rumors originated in propaganda spread by the faction who instigated the civil war against Marcus and Commodus. They may have wanted to portray Commodus as an illegitimate heir to the throne, so that it would be easier for Avidius Cassius to seize power instead. As it happens, the surviving statues make it apparent that Commodus bore a striking physical resemblance to his father, casting doubt on the claim that he was someone else’s son!

6 Marcus’ mother was a highly educated womanMarcus’ father died when he was about four years old, so other men in his family took responsibility for his upbringing, but his mother, Domitia Lucilla, also appears to have taken him back into her own care eventually. Marcus loved her dearly and she spent her final years living with him in the imperial palace of Emperor Antoninus Pius. She was a physically small but otherwise quite imposing woman. She had inherited a brick and tile factory, and clay fields, from her side of the family, making her one of the leading figures in the Roman construction industry, and probably one of the wealthiest and most powerful women in Rome. Many bricks have been unearthed with her name stamped on them.

Artwork from Verissimus, copyright Donald J. Robertson, reproduced by permission.

Artwork from Verissimus, copyright Donald J. Robertson, reproduced by permission.She was also an intellectual, and appears to have had a reputation as a philhellene or lover of Greek culture. Herodes Atticus, the leading figure of the Second Sophistic, and the most prominent Greek intellectual and orator of the time, was raised in the same household as her, and they seem to have remained family friends. She also seems to have been friends with Marcus’ main Stoic tutor, Junius Rusticus, and with his Latin rhetoric tutor, Fronto. Indeed, Fronto writes to her in Greek, addressing her as “the Mother of Caesar”, but he nervously asks young Marcus in one letter to check the grammar of his Greek because he doesn’t want to appear foolish or uncivilized. The fact that the leading Latin rhetorician of the time is intimidated when writing in Greek to Lucilla, shows that she was held in high regard as an intelligent and cultured woman.

She also appears to have taken Fronto’s young wife under her wing, as a kind of student. It’s likely that she was the patron of a salon, or circle of intellectuals, who visited their household, to discuss Greek literature, when Marcus was growing up. She probably had considerable influence over the selection of Marcus’ tutors. As it happens, in addition to the leading Greek and Latin rhetoricians of the time, there seem to be an unusual number of Stoic philosophers among Marcus’ teachers. We’re also told that he was introduced to the study of philosophy at the exceptionally young age of twelve. This may, perhaps, be evidence of his mother’s influence.

7 Marcus throws shade on two very important peopleRomans often show their disapproval by omitting or removing mention of someone’s name— a practice known as damnatio memoriae, which could be viewed as an ancient precursor of “cancelling” someone! There are two very striking examples of this in the Meditations. (Not including Seneca!)

The first is the Emperor Hadrian, Marcus’ adoptive grandfather. Hadrian groomed Marcus for power, and effectively had him placed in line to the throne, after Antoninus Pius. Marcus knew Hadrian pretty well, having been brought to live in his villa for the last six months or so of his life, when his mental and physical health rapidly deteriorated, and he engaged in political purges, including against members of Marcus’ own family. Marcus absolutely heaps praise on Antoninus Pius, in Book One of the Meditations, when listing the family members and tutors he most admires. He says nothing about Hadrian. In fact, he does mention Hadrian a few times later in the book but only to use him as an example of someone once powerful, who is now long dead, and will one day be forgotten. Worse, several of the qualities Marcus praises in Antoninus appear to be implicit criticisms of Hadrian. For instance, when Marcus says things about Antoninus like “nobody could ever accuse him of being a Sophist”, it often comes across as though he wants to add the words: unlike Hadrian!

The second is Herodes Atticus, Marcus’ main Greek rhetoric tutor. Herodes was a family friend, and the leading figure of the Second Sophistic movement. He was the most celebrated intellectual in the Roman empire at that time. However, we know he was very critical of Stoic philosophy. Marcus makes no mention of him whatsoever anywhere in the Meditations. He literally has nothing positive to say about him. Instead, he praises all of his Stoic tutors, and even an unnamed tropheus, or nanny-tutor, probably a slave or freedman, who cared for him when he was a small child. The notoriously pompous Herodes would have been utterly aghast at being ignored in this way, especially when Marcus makes a point of expressing gratitude for what a nameless slave taught him.

8 Marcus may have been a budding historianIn a letter to Marcus, Fronto says in passing “I gave you advice on what you should do to prepare yourself for writing a work of history, since that is what you wished.” Moreover, Marcus seems to allude in the Meditations to having been compiling notes for a history of ancient Greeks and Romans.

Don’t be sidetracked anymore! You’re not going to read your notebooks, or your accounts of ancient Roman and Greek history, or the commonplace books you were saving for your old age. — Meditations, 3.14

We can actually glimpse clues throughout the Meditations of Marcus’ attitude toward famous Greeks and Romans, and they would have been somewhat controversial. For instance, he writes:

Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great, what are they in comparison with Diogenes the Cynic and Heraclitus and Socrates? — Meditations, 8.3

He clearly prefers the philosophers and thinks the great military leaders are overrated, and somewhat morally compromised individuals, enslaved by the desire for power and glory.

9 Marcus introduced safety nets for tightrope walkersIn the ancient world, children were often trained to perform acrobatic feats for the entertainment of paying audiences. The crowds often wanted these to be as sensational and therefore dangerous as possible. One of our sources claims that Marcus Aurelius put a stop to this at Rome.

Among other illustrations of his unfailing consideration towards others this act of kindness is to be told: After one lad, a rope-dancer, had fallen, he ordered mattresses spread under all rope-dancers. This is the reason why a net is stretched them to-day. — Historia Augusta

An earlier historian, Cassius Dio, says that Marcus was famously opposed to bloodshed and therefore required the gladiators at Rome to “contend, like athletes, without risking their lives”, by fighting with blunted weapons. It’s believed that this specifically meant fighting with weapons that were able to cut but not pierce, so they would still cause superficial wounds but were less to kill and opponent.

10 Marcus was initiated into the Eleusinian mysteriesThe Sophist Philostratus quotes a letter which Marcus Aurelius reputedly wrote to Herodes Atticus, saying:

Do not, I say, feel resentment against me on this account, but if I have annoyed you in aught, or am still annoying you, demand reparation from me in the temple of Athena in your city at the time of the Mysteries. For I made a vow, when the war began to blaze highest, that I too would be initiated, and I could wish that you yourself should initiate me into those rites. — Lives of the Sophists

This was probably a widely-publicized event, as Marcus paid for rebuilding of the temple complex, which had been damaged during the war. The fact that he was initiated was mentioned by three different historians of the period. A bust of Marcus was placed above the main gate to the temple precinct and it still remains there as part of the ruins at modern-day Elefsina, just outside Athens.

Artwork from Verissimus, copyright Donald J. Robertson, reproduced by permission.

Artwork from Verissimus, copyright Donald J. Robertson, reproduced by permission.The mysteries of Eleusis concerned the myth of the goddess Demeter, the earth mother, associated with agriculture. Several passages in the Meditations clearly evoke Eleusinian symbolism relating to ears of corn, and natural cycles of birth and death.

Life must be reaped like the ripe ears of corn. One man is born; another dies. — Meditations, 7.40

There was always an association between the Eleusinian mysteries and Stoicism as the ceremony, which lasted several days, actually began before the Stoa Poikile, the home of the Stoic school at Athens, before proceeding to nearby Eleusis.

Artwork from Verissimus, copyright Donald J. Robertson, reproduced by permission.Conclusion

Artwork from Verissimus, copyright Donald J. Robertson, reproduced by permission.ConclusionWe included most of these and many more anecdotes in our graphic novel, Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius. Some of these less well-known details add richness to our understanding of Marcus’ character, and that can allow us to feel his presence more when reading the Meditations, allowing him to become a three-dimensional human being.

Enter into every man’s mind and also let every other man enter into yours. — Meditations, 8.61

By really trying to picture the events of his life, and imagine ourselves in his shoes, we can immerse ourselves more fully in his use of Stoic philosophy, as a guide to living wisely.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

April 20, 2023

What is Wisdom? with J.W. Bertolotti

In this episode, I chat with host of the In Search of Wisdom podcast, and founder of the Perennial Leader Project. Josh was one of the speakers at our Stoicon-x Military event a few years ago. We’re both very active on Substack now, Josh at so I thought it would be a great opportunity to reconnect and chat about philosophy as a guide to life.

Highlights

HighlightsHow Joshua got into philosophy

His journey as a podcaster speaking to people about the nature of wisdom

Stoicism and other philosophies

Desire and attachment in philosophy

Conceit, and skepticism as a way of life

How the Delphic maxims can teach us about philosophy

LinksNewsletter on Substack

In Search of Wisdom Podcast @in sear on Substack and on Spotify

Perennial Meditations Podcast

@JWBertolotti on Twitter

Perennial Leader Project website

April 18, 2023

Marcus Aurelius as Disciple of Epictetus

Epictetus was the most important Stoic philosopher of the Roman Imperial period, and perhaps even the most influential philosophy teacher in Roman history. We can see that he had considerable influence over Marcus Aurelius but the relationship between them probably requires some explanation.

Ancient Stoicism took different forms. The rhetorician Athenaeus, who lived around the same time as Marcus, claimed that the Stoic school had divided into three branches. These consisted of the followers of the three last scholarchs, or heads, of the school: Diogenes of Babylon, Antipater of Tarsus, and Panaetius of Rhodes. Although it’s difficult to know exactly what the differences were, it seems likely that the Stoicism of Panaetius was more philosophically eclectic in nature, drawing more upon aspects of Platonism and Aristotelianism.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Epictetus never mentions the “Middle Stoicism” of Panaetius and seems instead to hark back to an older form of the philosophy, more aligned with Cynicism. The only one of the three scholarchs above he mentions is Antipater, so it’s possible he saw himself as following the “Antipatrist” branch of Stoicism. Marcus aligned himself mainly with Epictetus, and perhaps assumed he was part of the same branch of Stoicism.

It is fair to say that the essential substance of Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations comes from Epictetus. — Hadot, Philosophy as a Way of Life, 195

The Men who Knew Epictetus

The Men who Knew EpictetusMarcus was only about fourteen years old when Epictetus died. He’d probably never left Rome and it seems virtually certain that the two never ever met in person. Epictetus had previously lived and taught philosophy in Rome but left around 93 AD when the Emperor Domitian banished philosophers, nearly three decades before Marcus Aurelius was born. He set up a Stoic school in Nicopolis in Greece, where he remained for the rest of his life. However, their lives overlapped and Marcus surrounded himself with philosophers, particularly Stoics. Some of the older men he knew had doubtless studied with Epictetus in person.

The Emperor Hadrian was a passionate hellenophile and associated with many philosophers. Though far from a Stoic himself, he was reputedly a personal friend of Epictetus. Marcus was close to Hadrian, who chose him to succeed Antoninus, his immediate heir. So it’s quite possible Marcus first heard of Epictetus from Hadrian and other members of his court. However, Marcus’ natural mother was another hellenophile and there’s a hint she was friends with Junius Rusticus, whom we’ll return to below. It’s vaguely possible she also had some familiarity with Epictetus or his students. Marcus mentions that Rusticus wrote an admirable letter consoling his mother. Rusticus was closer in age to Domitia Lucilla than to Marcus. It’s therefore possible that he was already a family friend prior to becoming Marcus’ tutor in philosophy, and it seems likely that he was an admirer, and perhaps former student, of Epictetus.

The Discourses and Handbook of Epictetus were not actually written by him but are edited notes made at his school by a student called Arrian of Nicomedia. Arrian was himself an exceptional man. He was reputedly, like Epictetus, a personal friend of Hadrian. Hadrian appointed him to the Senate and then made him suffect consul around 132 AD. He was later made governor of Cappadocia, for six years, where he became an accomplished military commander. Late in life, around 145 AD, he retired to Athens to serve as archon there, now under the emperor Antoninus. He was a prolific writer, highly esteemed as an intellectual, as well as being one of the most senior statesmen and military commanders in the empire. His relationship with Epictetus was compared to that of Xenophon with Socrates.

Arrian probably died not long after Marcus was acclaimed emperor in 161 AD, but it’s quite possible Marcus could have met him if Arrian ever visited Rome. He must certainly have known of him as Arrian held important roles during the reign of Antoninus, in the administration of which Marcus was effectively second-in-command. Arrian almost certainly knew Antoninus personally and probably also knew many other men in Marcus’ acquaintance.

Marcus reads EpictetusMarcus’ main Stoic tutor was Junius Rusticus. In The Meditations, Marcus stated that Rusticus gave him a copy of notes (hypomnemata) of Epictetus’ lectures. This could be taken to refer to personal notes taken down by Rusticus. However, Marcus quotes from Arrian’s edition of The Discourses several times so it’s generally assumed those were the “notes” of Epictetus’ lectures to which he referred. Of course, it’s also possible that Marcus possessed both The Discourses noted down by Arrian and also notes taken by Epictetus’ other students. Rusticus could easily have attended Epictetus’ school himself if he had travelled to Greece, and provided Marcus with notes on his lectures. He certainly seems to have encouraged Marcus to study Epictetus’ branch of Stoicism.

Marcus clearly felt that getting his hands on a copy of the Discourses was one of the key events in his life.

However, one later Roman source indicates that Rusticus served alongside Arrian in the Roman was against the Alani, toward the end of Hadrian’s rule. So it seems quite possible that Rusticus met Arrian, who provided him with a copy of The Discourses in person.

To make the acquaintance of the Memoirs of Epictetus, which he supplied me with out of his own library. — Meditations, 1.7

Marcus clearly felt that getting his hands on a copy of the Discourses was one of the key events in his life. What’s the significance of saying that it came from Rusticus’ private library?

Arrian wrote an introduction to the Discourses saying that he’d only intended them to be circulated in private among his friends but, somehow, they had leaked into the public domain. It’s tempting, therefore, to imagine that, as a youth, Marcus felt he’d narrowly missed the opportunity to meet the most acclaimed philosopher of his era, and assumed that he left behind no writings. It would have been a breathtaking experience for him to be told by Rusticus, his Stoic teacher, that, in fact, copious notes from the lectures of Epictetus had been preserved by Arrian. We can imagine that it would have been a life-changing event for Marcus to be handed a rare copy of the Discourses, therefore, from the private collection of Rusticus — at the time, quite possibly, Marcus had no idea these writings even existed.

Whereas four volumes of Epictetus’ Discourses survive today, there were originally eight – half of them are now lost.

It seems virtually certain the “notes” (hypomnemata) were what we now call The Discourses, written and edited by Arrian. Indeed, Marcus quotes several passages, which are found in The Discourses. However, whereas four volumes of Epictetus’ Discourses survive today, there were originally eight – half of them are now lost. In addition to the quotations from the surviving Discourses, however, in the Meditations, Marcus appears to attribute a saying and several more passages to Epictetus. It seems quite likely that one or more of these may come from the lost Discourses.

Marcus doesn’t always cite the name of the author he’s quoting, or even indicate when something is a direct quote or paraphrase from another text. So it’s quite possible that there are other passages in The Meditations which actually quote or paraphrase Epictetus’ lost Discourses. Some of the sayings popularly attributed to Marcus, for all we know, could be quotations from other authors, especially Epictetus. As we’ll see, Marcus alludes to Epictetus more often than any other author in the Meditations, although Heraclitus perhaps comes a close second.

Epictetus in The MeditationsMarcus mentions Epictetus by name in the illustrious company of Chrysippus and Socrates, which seems to confirm the exceptionally high regard in which he held him. We should remind ourselves that for Marcus, Epictetus was a contemporary whereas Socrates and Chrysippus were famous sages, from four or five centuries earlier in history. It would be a bit like comparing a living scientist to Isaac Newton and Galileo, perhaps, only more so.

How many a Chrysippus, how many a Socrates, how many an Epictetus has eternity already engulfed. (7.19)

Elsewhere, Marcus quotes from Discourses (1.28 and 2.22) where Epictetus paraphrases Plato’s Sophist.

‘No soul’, he said, ‘is willingly deprived of the truth’; and the same applies to justice too, and temperance, and benevolence, and everything of the kind. It is most necessary that you should constantly keep this in mind, for you will then be gentler towards everyone. (7.63)

The word “he” probably refers either to Socrates or Epictetus.

In another passage, he attributes a saying to Epictetus not found in The Discourses, which is numbered Fragment 26. The use of the Greek diminutive (“little soul”) is certainly typical of Epictetus’ way of speaking.

You are a little soul carrying a corpse around, as Epictetus used to say. (4.41)

Marcus repeats this phrase again later, suggesting that it was particularly significant to him, although the meaning is somewhat obscure to us now:

Children’s fits of temper, and ‘little souls carrying their corpses around’, so that the journey to the land of the dead appears the more vividly before one’s eyes. (9.24)

The phrase seems intended to remind us that reputation and possessions are extraneous, i.e., to puncture our ego and bring us back down to earth. Imagine, for a moment, that Rusticus, Marcus’ very direct and confrontational Stoic mentor, told him, the future emperor of Rome, that he was not really a Caesar but rather a little soul carrying around a bag of flesh and bones, like everyone else, and that his anger, even over the most important matters of state, was no more rational than the temper tantrum of a small child.

Marcus also appears to have a well-known saying of Epictetus in mind when he writes:

You can live here on earth as you intend to live once you have departed. If others do not allow that, however, then depart from life even now, but do so in the conviction that you are suffering no evil. “Smoke fills the room, and I leave it”: why think it any great matter? (5.29)

Elsewhere he appears to be quoting the Stoic slogan of Epictetus “bear and forbear” (or “endure and renounce”, Marcus uses the same Greek words as Epictetus). This phrase, incidentally, does not occur in the extant Discourses, but is known from other sources, providing further evidence that Marcus had read more of Epictetus than we have today.

Wait with a good grace, either to be extinguished or to depart to another place; and until that moment arrives what should suffice? What else than to worship and praise the gods, and do good to your fellows, and “bear” with them and “forbear”; but as to all that lies within the limits of mere flesh and breath, to remember that this is neither your own nor within your own control. (5.33)

In addition to these, Book 11 of The Meditations concludes with a flurry of quotations or paraphrases from The Discourses. The first is clearly from Discourses 3.24.86-7.

It takes a madman to seek a fig in winter; and such is one who seeks for his child when he is no longer granted to him. (11.33)

Epictetus is named by Marcus in the next one, which is from Discourses 3.24.28.

Epictetus used to say that when you kiss your child you should say silently ‘Tomorrow, perhaps, you will meet your death.’—But those are words of ill omen.—‘Not at all,’ he replied, ‘nothing can be ill-omened that points to a natural process; or else it would be ill-omened to talk of the grain being harvested.’ (11.34)

Then he quotes from Discourses 3.24.91-2.

The green grape, the ripe cluster, the dried raisin; at every point a change, not into non-existence, but into what is yet to be. (11.35)

Then from Discourses 3.22.105, a phrase which Epictetus repeated several times elsewhere.

No one can rob us of our free will, said Epictetus. (11.36)

This is followed by Epictetus Fragment 27, which appears to be from a lost book of the Discourses or perhaps from notes taken down by another student:

He said too that we ‘must find an art of assent, and in the sphere of our impulses, take good care that they are exercised subject to reservation, and that they take account of the common interest, and that they are proportionate to the worth of their object; and we should abstain wholly from immoderate desire, and not try to avoid anything that is not subject to our control’. (11.37)

Epictetus Fragment 2 also apparently from a lost book of the Discourses, but related to Discourses 1.22.17-21.

‘So the dispute’, he said, ‘is over no slight matter, but whether we are to be mad or sane.’ (11.38)

That appears to be linked to the last passage, a mini Socratic dialogue, which is probably also derived from one of the lost Discourses.

Socrates used to say, ‘What do you want? To have the souls of rational or irrational beings?’ ‘Of rational beings.’ And of what kind of rational beings, those that are sound or depraved?’ ‘Those that are sound.’ ‘Then why are you not seeking for them?’ ‘Because we have them.’ ‘Then why all this fighting and quarrelling?’ (11.39)

As Marcus clearly groups quotations together, it’s possible that some of the other passages surrounding those mentioned above, or elsewhere in The Meditations, could be quotes or paraphrases from The Discourses, or in some cases quotes from other authors cited in The Discourses.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

April 15, 2023

Announcing Marcus Aurelius Anniversary Event

You are invited to join our special symposium on the life and philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, the famous Stoic Roman Emperor. This virtual event, hosted by will take place on 26th April, to commemorate his birthday. Register today, via EventBrite, and join me and Dr. John Sellars, as we discuss what we can learn from the Stoic philosophy of Marcus Aurelius to improve our lives today, in the modern world.

John is an academic philosopher, currently a Reader in Philosophy at Royal Holloway, University of London, a Visiting Research Fellow at King's College London. He is also the chair of Modern Stoicism, and on the board of the Aurelius Foundation. We have both written several books about Stoicism, including recent ones on Marcus Aurelius.

John is the author of Marcus Aurelius for Routledge's Philosophy in the Ancient World series, wrote an introduction for Farquharson's translation of The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius for Macmillan Collector's Library, and he is the editor of the forthcoming Cambridge Companion to Marcus Aurelius' Meditations. I have written three books on Marcus Aurelius: How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, a self-help book based on him; Verissimus, a graphic novel about his life; and the forthcoming biography of him for Yale University Press’ Ancient Lives series.

The format of this event will be an informal “fireside chat”, with two authors who have studied the life and philosophy of Marcus Aurelius in depth. John and I will be chatting about Marcus for an hour, followed by half an hour of Q&A from the audience. So you will have an opportunity to ask us your burning questions!

Get your ticket now, and join us. We’ll be using this opportunity to test out Streamyard, as an alternative platform to Zoom. So we’re hoping that will allow for a more seamless event, and better interaction with the audience. We’re hoping to get at least five hundred people attending, so please tell your friends. Tickets are free but if you want to donate to support The Plato’s Academy Centre nonprofit, that helps ensure we can continue providing events like this in the future. Many thanks!

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

April 13, 2023

Some things are up to us and others are not

CommentSome things are under our control, while others are not under our control. Under our control are conception, choice, desire, aversion, and, in a word, everything that is our own doing; not under our control are our body, our property, reputation, office, and, in a word, everything that is not our own doing. Furthermore, the things under our control are by nature free, unhindered, and unimpeded; while the things not under our control are weak, servile, subject to hindrance, and not our own.

Remember, therefore, that if what is naturally slavish you think to be free, and what is not your own to be your own, you will be hampered, will grieve, will be in turmoil, and will blame both gods and men; while if you think only what is your own to be your own, and what is not your own to be, as it really is, not your own, then no one will ever be able to exert compulsion upon you, no one will hinder you, you will blame no one, will find fault with no one, will do absolutely nothing against your will, you will have no personal enemy, no one will harm you, for neither is there any harm that can touch you. — Enchiridion, 1

Some things are up to us whereas others are not. Arrian of Nicomedia, who compiled the Handbook and Discourses from notes made during Epictetus' lectures, put this sentence first because it's so fundamental to everything else that follows.

April 12, 2023

Join me on Substack Notes

I just published my first public note on Substack Notes, why not join us there! It’s basically an alternative to Twitter, where there are more writers, and fewer politicians.

Notes is a new space on Substack for us to share links, short posts, quotes, photos, and more. I plan to use it for things that don’t fit in the newsletter, like work-in-progress or quick questions - and random bits of philosophy.

How to joinHead to substack.com/notes or find the “Notes” tab in the Substack app. As a subscriber to Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life, you’ll automatically see my notes. Feel free to like, reply, or share them around!

You can also share notes of your own. I hope this becomes a space where every reader of Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life can share thoughts, ideas, and interesting quotes from the things we're reading on Substack and beyond.

If you encounter any issues, you can always refer to the Notes FAQ for assistance. Looking forward to seeing you there!