Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 28

July 27, 2023

Stoicism in Three Steps: Physics, Ethics, Logic

Constantly, and, if it is possible, on the occasion of every impression on the soul, apply to it the principles of Physics, Ethics, and Dialectic. — Marcus Aurelius

This is George Long’s classic translation of Meditations 8.13. This passage, like many others in the Meditations, is difficult to translate because it’s so concise, and yet tries to pack in a lot of meaning, through Marcus’ exceptionally careful choice of words. I think it may refer to three-steps in a therapeutic procedure.

Robin Waterfield, who is responsible for the most recent translation currently available of the Meditations, renders the same passage as follows:

Every moment and whenever an impression arises, do your best to be a scientist, a psychologist, and a logician.

He explains in a footnote: “The Stoics divided philosophy into physics (studied by natural scientists), ethics (here psychology, my translation of ‘expertise in the passions’), and logic.” The original Greek looks like this:

Διηνεκῶς καὶ ἐπὶ πάσης, εἰ οἶόν τε, φαντασίας φυσιολογεῖν, παθολογεῖν, διαλεκτικεύεσθαι.

Put more literally, Marcus actually says:

To talk about what is physical, i.e., to do “natural philosophy”

To talk about the passions, i.e., to do “(psycho-)pathology”

To use “dialectic”, i.e., logical analysis applied to our own moral judgment

Marcus is describing something relatively common sense here, which risks getting lost in translation

In my opinion, Marcus is describing something relatively common sense here, which risks getting lost in translation. Or rather, I think he has a simple process in mind, which nevertheless takes place within the context of a sophisticated philosophical system. Rather than beat about the bush, I’ll explain it in plain English, before proceeding to analyse it and comment.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

What Marcus Really Means?First of all, he clearly means that we should practice a form of mindfulness, as continually as possible throughout the day. This consists in carefully observing our intrusive thoughts and perceptions of events (impressions), particularly when we notice strong desires or emotions. For example, let’s suppose you’re giving an important presentation at work, someone says something critical, you feel like an idiot, and become highly anxious as a result — a fairly common concern these days.

Say nothing more to yourself than what the first appearances report. Suppose that it has been reported to you that a certain person speaks ill of you. This has been reported but that you have been injured, that has not been reported. […] Always abide then by the first appearances, and add nothing yourself from within, and then nothing happens to you. — Meditations, 8.49

We should then respond promptly with the following three steps:

Stick to the facts. Describe the external event to yourself as objectively as possible, suspending value judgments, rhetoric, and assumptions. Example: “I was talking to a group of people and someone said they disagreed with me.”

Analyze your emotions. Identify the beliefs that are causing your emotional reaction, especially underlying value judgments and your beliefs about what you should do. Example: “I thought to myself ‘This is awful; I look like an idiot’ and ‘I must not let them see that I’m upset!’, and that made me feel more anxious.” (Step 1, objective description, has made this easier by suspending or separating our emotional response from the external event to which it refers.)

Challenge your beliefs. Using dialectic, or the Socratic Method of questioning, you should respond by listing pieces of counter-evidence that refute the assumptions causing your emotions. Example: “Yes but it’s not as awful as it seemed because they’re more interested in the rest of what I’m saying than one small criticism, and they already know I’m good at my job, and I doubt they place as much importance on it as I did anyway.” (Step 2 , diagnosing the cognitive basis of our emotion, has made this possible by isolating the value judgment causing our emotion, which can now be examined logically.)

It’s a perfectly sensible approach. First get clear about the facts of the situation, then identify how your thoughts were making you upset, then challenge those thoughts using philosophical reasoning. Steps 1 and 2 combined resemble what we call “cognitive distancing” in modern psychotherapy, often understood as a necessary precursor to disputation (step 3). We have to distinguish between our feelings and reality, then identify the specific beliefs causing our feelings, in order to dispute and change them, and thereby remedy them.

I don’t think we can be absolutely certain that Marcus intended to describe three steps in a sequence in this passage. However, it makes perfect sense both in terms of Stoic philosophy and also by comparison with what we would actually do in modern cognitive therapy. Reading the passage this way also makes it appear much more intelligible and useful — otherwise it seems rather more vague and abstract.

This is how I’d describe what’s happening in each step:

Natural philosophy. Describe the external event to yourself in terms of its physical properties, without values — as if you were what the Greeks called a “natural philosopher”, such as Anaxagoras. The natural philosophers were renowned for dispelling superstitious fears by explaining natural phenomena in terms of their physical causes.

Psychopathology. Identify the beliefs causing the emotion, like an ancient pathologist of the mind, or a modern-day psychologist or psychotherapist. This emotional response is precisely what has been removed or suspended in relation to the naturalistic explanation above — we can now study it separately. This resembles “conceptualization” (a type of assessment or diagnosis of the problem) in modern cognitive therapy.

Dialectic. Using the Socratic Method of questioning, as if you’re cross-examining a witness in court. This is cognitive therapy proper, where we begin changing the beliefs that are causing our emotional problems.

The Stoics also refer to the first step as the use of a phantasia kataleptike, meaning an impression that retains its grip on reality, sometimes translated “objective representation”.

This method is quintessentially Stoic: it consists in refusing to add subjective value-judgements – such as “this object is unpleasant,” “that one is good,” “this one is bad,” “that one is beautiful,” “this is ugly” – to the “objective” representation of things which do not depend on us, and therefore have no moral value. The Stoics notorious phantasia kataleptike – which we have translated as “objective representation” – takes place precisely when we refrain from adding any judgement value to naked reality. In the words of Epictetus: “we shall never give our assent to anything but that of which we have an objective representation.” — Pierre Hadot, Philosophy as a Way of Life, 1995

I think that by remembering these three steps, individuals using Stoicism today as a form of self-help may find it easier to put the philosophy into practice. It gives us a very helpful three-step structure. It may be that a similar three-step model can be found in other ancient Stoic passages. If you spot any examples, please let me know in the comments.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

July 21, 2023

An Illustrated Guide to Stoic Anger-Management

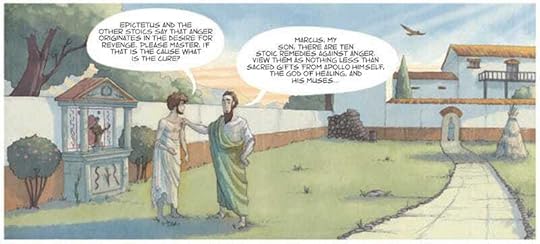

Artwork from Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius (2022), copyright Donald J. Robertson

Artwork from Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius (2022), copyright Donald J. RobertsonWhat does Stoic philosophy tell us about how to control our tempers? When we began working on our graphic novel, Verissimus, the illustrator, Zé Nuno Fraga, and I decided to show how colourful and action-packed Marcus Aurelius’ life really was. We also liked the idea, however, of leaving our readers with a good amount of practical advice from Stoicism, which they could take away and use to help themselves and others.

I chose to focus on Stoic advice about anger — the royal road to self-improvement.

I chose to focus on Stoic advice about anger — the royal road to self-improvement. We know that this was a problem for Marcus because he tells us in the Meditations that he struggled, at first, to master his own temper. Later in life, Marcus had a reputation for remaining completely level-headed, even in the face of extreme provocation. So it appears that he succeeded in using Stoicism to master his natural quick temper. He did this by employing Stoic psychological practices, over and over again, on a daily basis. I can see parallels between many of these strategies and those employed in modern cognitive therapy. So I think that, with practice, they may help the rest of us cope with our feelings of anger too.

It was one of the men who provoked Marcus’ temper the most, ironically, who also taught him how to restore calm and rebuild friendships after an argument — his Stoic mentor, Junius Rusticus. We therefore speculated, in our illustrations, that it could have been Rusticus who taught Marcus the ten anger-management strategies he describes using in the Meditations (11.18). Marcus, curiously, refers to these as ten “gifts” from the god Apollo, and his nine Muses. Apollo, Lord of the Muses, was the god of the arts, including the arts of medicine and, in a sense, also philosophy. It’s perhaps fitting, therefore, that Marcus would call these therapeutic strategies, or self-help tips, gifts from the god of healing.

Draft for Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius (2022), copyright Donald J. Robertson

Draft for Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius (2022), copyright Donald J. RobertsonMarcus describes things he should tell himself whenever he noticed he was growing annoyed with someone. I would call these cognitive (thinking) strategies for anger-management. In this article, I’ll discuss each of his ten strategies in turn, adding a few comments, here and there, from my perspective as a cognitive-behavioural psychotherapist.

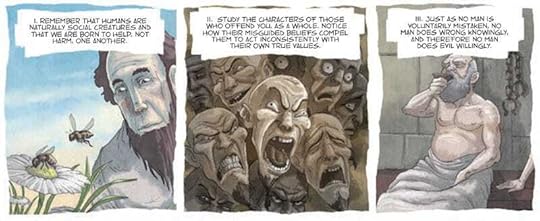

Artwork from Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius (2022), copyright Donald J. Robertson1. Remember that humans are social creatures

Artwork from Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius (2022), copyright Donald J. Robertson1. Remember that humans are social creaturesThis seems to be the toughest Stoic strategy for most people to swallow today, although it’s the one Marcus appeals to most often. It’s actually based on a philosophical argument, about human nature, which predated Marcus by roughly six centuries. We can trace it back at least as far as the “Great Discourse” of the famous Sophist, Protagoras. He argued, foreshadowing Darwin’s theory of natural selection, that because humans happen to be more physically vulnerable than other creatures, they learned to form communities, which required developing principles of justice. We’re social creatures, by nature, because the survival of our ancestors depended upon their cooperation with one another.

Marcus frequently reminds himself of our social nature in the Meditations. We’re not unlike ants or bees, in this regard, who naturally flourish by working together. Of course, in reality, we often compete with and even fight against one another. Nevertheless, the Stoics believe that we have an innate duty to try to realize our potential for living harmoniously, by showing kindness and fairness toward one another. Stoics call this the virtue of “justice” (dikaiosune), although it includes actively trying to help, rather than harm, our fellow humans. Put very simply, Marcus believed that by reminding himself of our natural capacity for kindness and friendship, he would become more inclined toward these ideals, instead of simply giving in to feelings of anger.

2. Consider their character as a wholeWhen people become angry their thinking typically becomes more distorted. In a sense, anger makes us irrational, in several ways. The Stoics put it more bluntly: “Anger is temporary madness.” One of the simplest “cognitive distortions” we experience is called selective thinking. Angry people tend to focus their attention on every detail that feeds their negative emotional state. They also ignore things that might give them cause to feel less upset. When enraged we view the person annoying us through angry “tunnel vision”, in other words, whereas others might view them in a more rounded and complete way.

Narrowing attention in this way is like putting our annoyances under a magnifying glass. Stoics do the opposite by deliberately broadening their attention, and thinking about the other person’s character as a whole. The latter is a much wiser, and healthier, way of responding. Rather than denying or ignoring what someone did to upset us, we’re continuing to notice it, but also noticing many other details as well. Marcus says that when someone is starting to annoy him, he makes a conscious effort to think of their behaviour in many different situations: how they eat, sleep, their other relationships, etc. He also considers how certain questionable assumptions, and perhaps even errors, may have shaped their actions. He does this to avoid the problem of selective attention and to arrive at a more balanced perspective on the character of others.

3. No man does evil willinglyMarcus knew that this was a famous “paradox” of Socrates. The Athenian philosopher, who had died over five centuries earlier, had paved the way for Stoicism — you could call Socrates the godfather of Stoicism. He believed that we all naturally want to do what’s good for us. However, everyone is fallible. So, in practice, we have misconceptions about what we should be doing. People who engage in wrongdoing believe that what they’re doing is right. That doesn’t mean they believe other people think it’s right, of course. People often consider themselves to be doing what’s right even though they know others consider their actions wrong. Brutal dictators like Hitler and Stalin arguably provide a good example: they were dangerously convinced that their actions were justified.

Socrates was able to look his accusers in the face and maintain this perspective, rather than growing angry, even when he was sentenced to death, and handed a cup of poison hemlock to drink. He noted, though, that if someone is misguided about what’s genuinely right and wrong, their actions aren’t entirely voluntary. No matter how awful they seem, their actions can be said to be determined by their own moral ignorance.

This is a very forgiving philosophy, in a sense. Marcus believed that by learning to view the behaviour of others in this way he would reduce his frustration and annoyance with them. Perhaps this attitude also allows us to focus, more constructively, on the question of whether or not those engaged in wrongdoing can be persuaded to change their ways. It’s interesting to note that Marcus served, throughout his adult life, as a magistrate in the Roman courts. Like other Stoics, he believed in trying to reform others, where possible, rather than seeking revenge against them.

Artwork from Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius (2022), copyright Donald J. Robertson4. Realize that we all have similar flaws

Artwork from Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius (2022), copyright Donald J. Robertson4. Realize that we all have similar flawsPause to look in the mirror when you’re starting to become annoyed with other people. Or at least, step back, metaphorically, from the situation, and take a careful look at your own character and actions. The Stoics were originally called “Zenonians” after their founder, Zeno of Citium. Later they named themselves the “Stoics”, after the Stoa Poikile, or “painted porch”, a public colonnade in the Athenian Agora where they met to discuss philosophy. Other schools of Greek philosophy were named after their founders, such as the Pythagoreans, Platonists, Aristotelians, and Epicureans. The Stoics, however, insisted that no man was perfectly wise or beyond reproach — not even their founder, Zeno, was flawless.

I think this attitude of humility is central to Stoicism. We tend to minimize or ignore our own weaknesses in a way that makes us all slightly conceited and narcissistic. The more angry we feel, the more unforgiving and self-righteous we tend to become. We may disapprove of the actions of another but we tend to become less acutely enraged when we consciously accept that we’re capable of exhibiting similar flaws ourselves. Psychologists used to call this “projection” — when you point a finger at someone, three of your own fingers are pointing back at you! Marcus thought that as soon as we notice ourselves becoming irritated with another person, therefore, we should take it as a signal that we must have lost sight of this. We’re being arrogant and ignoring our own weaknesses and should, instead, stop and think — we should look within ourselves.

Of course, people often do terrible things, even committing crimes like murder, of which we’d like to think that we’re utterly incapable ourselves. The Stoics would perhaps say that this is another form of conceit. Even if we have never done such terrible things ourselves, we may nevertheless have felt like doing them. We don’t know for sure what we could be driven to do if caught in very extreme circumstances. Perhaps you’re convinced nothing could ever compel you to think about actually killing another human, even for a split second. Nevertheless, we’ve all thought about lashing out against people, or seeking revenge, to some extent. In that regard, we all share vicious character flaws, albeit to varying degrees. Having the humility to concede that you’re not perfect yourself, as Marcus did, can sometimes help to reduce the intensity of your anger toward others.

5. Keep an open mind about their motivesMarcus spent decades studying jurisprudence, or legal theory, and took his duties as a Roman magistrate very seriously. Even as emperor, he presided over trials. He learned from extensive experience, presiding in the courts, how difficult it is to be certain about other people’s motives. Marcus noted that we often seem to do the wrong things for the right reasons. Many criminals likewise feel inwardly justified and self-righteous in their actions, or at least believe that the negative consequences for others of their bad behaviour are quite trivial. Marcus recalls how those accused of wrongdoing are often indignant, believing themselves to be innocent. Things are not always what they seem. In fact, not only is it difficult to understand the motives of others but often they don’t even fully understand their own motives.

The Stoics want us to recognize the limits of our knowledge — we’re not mind-readers. Anger is often associated with unwarranted certainty about the supposedly vicious or corrupt motives of others. We jump to conclusions about what other people are thinking when we’re getting mad at them. Everything they do or say appears malicious. You can see that sort of negative confirmation bias operating every day in arguments on social media. The Stoics want us to remember that the reasons behind our actions are often hidden from public scrutiny. Yet anger is fueled by certainty. So to the extent that we can reasonably suspend judgment about the motives of others, we can learn to control our temper.

6. Remember that you both must dieAs a young boy, Marcus was adopted by the Emperor Hadrian, and briefly raised in his villa. Later in life, though, he was surrounded by younger men who only knew Hadrian as a historical figure, from sculptures and anecdotes about him in books. Marcus would look at images of Hadrian and imagine that one day he too would be gone except for a few old statues and scraps of history, and eventually he would be forgotten completely. Marcus liked to meditate on how the concerns of Hadrian, and other great rulers who came before him, often seem more trivial in retrospect. They believed that they were very powerful and important men, and yet most of the things they cared about, and became angry about, have since been entirely forgotten.

When he was becoming irritated with someone, Marcus would therefore tell himself that before very long both he and the annoying person would be dead, and eventually forgotten. Once again, in a sense, this involves adopting a much broader perspective on events rather than putting them under a magnifying glass. (That’s a recurring theme in Stoicism.) When we remember that something is transient, we experience both its presence now and we simultaneously imagine a time before it existed and its absence in the future, after it is gone. If we can experience the presence and absence of something at the same time, we naturally reduce the intensity of our emotional reactions, such as feelings of anger. That’s why Marcus contemplated his own mortality, and that of the other person, when he noticed he was becoming angry, and reminded himself of the ephemeral nature of the things about which they were getting upset.

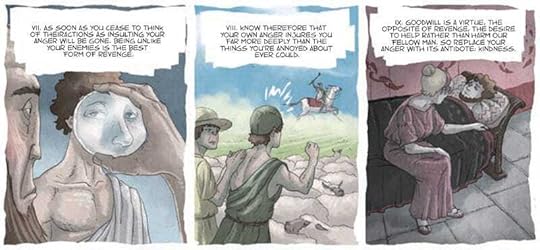

Artwork from Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius (2022), copyright Donald J. Robertson7. It is your own opinions that anger you

Artwork from Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius (2022), copyright Donald J. Robertson7. It is your own opinions that anger youMarcus was a big fan of the Stoic philosopher Epictetus who famously said “It is not things that upset us but rather our opinions about them.” Marcus applied this to many situations, including feeling angry with someone. It is not the other person’s actions that make us angry, in other words, but rather our opinions, especially our value judgements, concerning what they did. We make ourselves angry, according to the Stoics. That’s more obvious if you consider that another person looking at exactly the same situation might feel less angry about it, or not feel angry at all. Indeed, you might not feel as angry about it yourself, months or years from now, looking back on events one day in the future.

This is arguably the most important psychological insight ever made by the ancient Stoics. It went on to become the inspiration for modern cognitive psychotherapy. Early pioneers of cognitive therapy, such as Albert Ellis and Aaron T. Beck, used to teach the quote above from Epictetus to their clients and students. Many modern research studies now confirm that our opinions (cognitions) play a key role in determining our emotional responses, and that by changing them we can change unhealthy emotions into more healthy and adaptive ones. Moreover, there’s now good evidence to support the conclusion that this insight alone can give us more control over our emotions and reduce their intensity. Simply reminding yourself, as Marcus did, that it’s not events that make you angry, but rather your opinions about them, can potentially be therapeutic in itself.

8. Anger hurts you more than the thing you’re angry aboutThis is another very fundamental Stoic principle that applies to many desires and emotions, not just anger. Our strong desires and emotions (“passions”), in general, do us more harm than the things about which we’re upset. The worst, perhaps, that other people can do is kill you, destroy your reputation, and all of your property. Anger, though, by penetrating right to the core of your being, can destroy your very character. The Stoics would even say that anger robs us of our humanity, if we let it, and turns us into wild animals.

There’s a hint of this attitude when people say “It’s not worth it!” to someone who is losing their temper or about to get in a fight. On one hand, the consequences of anger are often that we just make situations even worse for ourselves and others. Actions based on anger frequently do more harm than good. The Stoics emphasise this but they want to go even further and say that, its external consequences aside, anger transforms our very character by its existence, degrading us, and, in that sense, harms us more deeply than any external events ever could. Realizing that anger does us more harm than the things, or people, we’re angry with, though, should motivate us to look inward and focus on personal change rather than lashing out at others.

9. Kindness is the antidote to angerThe Stoics knew that one way to conquer a harmful emotion is to directly cultivate its opposite. Behaviour therapists use a similar strategy named “counter-conditioning”, replacing one habit or emotion with another that naturally inhibits it. (Training in relaxation, e.g., is often used to counteract anxiety.) In Stoic psychology, anger is understood primarily as the desire for revenge — we want to harm someone, or at least for them to be somehow punished. It is associated with the belief that the other person has acted “unjustly”, or unacceptably. More fundamentally, it often derives from the idea that they have somehow harmed us, or at least are threatening to do so. Marcus, for instance, believed that anger is a form of weakness, for several reasons, one being that it is typically based on irrational fears and perceived injuries. A Stoic sage is above anger, because he or she is beyond the reach of fear.

Marcus believed that it requires great wisdom and strength to respond to the provocations of others with kindness. He actually says that true “manliness” consists in having the strength of character to show kindness rather than hatred and aggression. For Stoics, kindness, being the opposite of revenge, consists in the desire to help others rather than harm them. When we really grasp the contrast between these two emotions, it becomes obvious that they’re based on mutually incompatible attitudes. The Stoic ideal is to respond to our “enemies” by wishing to help them rather than harm them. The cognitive strategies above help to prepare the way for this. Marcus is not talking about gritting our teeth and pretending to show kindness but rather a fundamental transformation in our philosophy of life and attitude toward others.

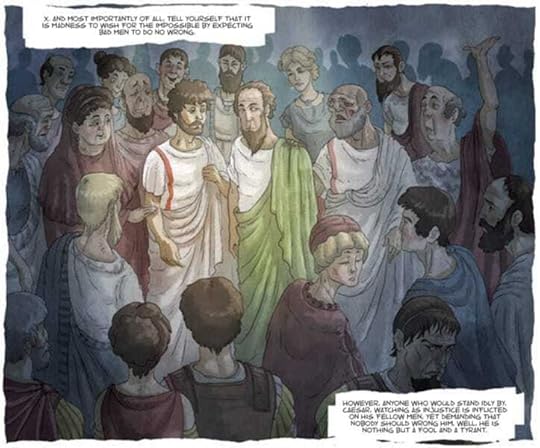

Artwork from Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius (2022), copyright Donald J. Robertson10. Realize the folly of expecting everyone to be wise

Artwork from Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius (2022), copyright Donald J. Robertson10. Realize the folly of expecting everyone to be wiseMarcus, as we’ve seen, calls these “gifts from Apollo”, i.e., therapeutic strategies derived from the god of healing. Apollo was also the god of prophecy. Marcus says that whereas the other nine gifts derive from his Muses, the tenth comes from the Lord of the Muses, the god Apollo himself. It is the gift of rational foresight, and having a philosophical attitude toward future events.

The Stoics noticed that when people become highly upset they often exhibit shock or surprise, which can seem unwarranted to neutral observers. For instance, they cry out things like “I can’t believe this guy!”, “How can this be happening?”, “This is unbelievable!”, and so on. Oddly, though, these expressions of surprise usually relate to common misfortunes that happen every day to other people — so why act surprised? Marcus portrays the sage-like ability to calmly anticipate common setbacks in life as the crowning glory of Stoic anger management.

Stoics do this through a daily practice called “premeditation of adversity” (premeditatio malorum in Latin) or “dwelling in advance” (προενδημεῖν in Greek). This involves imagining challenging situations, in this case people who might make you angry, in advance, as if it’s already happening, in order to practice adopting a philosophical attitude toward them. It’s both a way of rehearsing Stoicism and of learning to view such events as unsurprising when they actually happen. Marcus describes doing this in what is perhaps the most widely-quoted passage from the Meditations:

Begin the morning by saying to yourself, I shall meet with the busybody, the ungrateful, arrogant, deceitful, envious, unsocial. All these things happen to them because of their ignorance of what is good and evil. — Meditations, 2.1

In addition to telling himself that they do these things through ignorance more than through malice, Marcus goes on to rehearse several of the other Stoic anger management strategies we’ve just described. He says he cannot be angry or hate these individuals as long as he reminds himself to view them as his kin, like fellow brothers and sisters. Rather than focusing on our potential conflict, he tells himself that nature intended us to work together for the common good. He says that the actions of others can never truly harm him, unless he allows them to change his moral character. One of the foundation stones of Stoicism, in other words, is this daily training. We should, like Marcus, imagine people doing potentially “annoying” things, while we patiently rehearse more resilient ways of coping, thereby training ourselves to adopt a more Stoic attitude toward others.

ConclusionMarcus warned himself that we are all slaves… as long as we allow anger and other toxic passions to control our lives.

Marcus’ advice is still relevant today. In fact, it may be more important than ever, as social media seems to encourage trolling, arguments, and even hatred and anger toward others. We have to take responsibility for our own emotions, the Stoics said, otherwise we become like puppets whose strings are pulled by external events, such as today’s news and social media. Marcus warned himself that we are all slaves, even a Roman emperor, as long as we allow anger and other toxic passions to control our lives.

Marcus Aurelius was an exceptional ruler, in part, because he dedicated his life to training in Stoicism, including conquering his own anger. We wanted to bring his struggles to life in Verissimus, our graphic novel, through illustrations like the ones above, in order to put a more human face on ancient Stoicism. The more you can visualize a real historical figure using these anger-management strategies, and other aspects of Stoicism, the easier it becomes to do so in your own life.

How to Live Like Socrates: What's inside?

Anyone who holds a true opinion without understanding is like a blind man on the right road. – Socrates in Plato's Republic

Have you had a chance to check out yet?

I created this online course after realizing that few people today were really aware of the practical implications of Socrates' teachings as a philosophy of life.

I knew this was something that might truly make a difference. As a result, I designed , my elearning course on the Socratic dialogues.

Sometimes it can be hard to visualize a course like this, so if you’d like to take a look behind the curtain and see exactly what you’d be getting, check out this brief overview of the content.

Week One: Wisdom and the Socratic MethodThis section focuses on the story of the Socratic Method (elenchus), how it was developed and used by Socrates. It uses illustrations from the life of Socrates, such as the influence of his father and mother's professions. It explores what the virtue of wisdom means in the Socratic dialogues. Includes: Videos, reading, discussion, knowledge-check quiz, weekly webinar, plus bonus material.

Week Two: Moderation and Philosophy as a Way of LifeThis section focuses on the concept of philosophy as a way of life, and what, for Socrates, it meant to be a philosopher. It uses illustrations from the life of Socrates, such as his military service and attitudes toward diet and exercise as illustrations. It explores what the virtue of moderation means in the Socratic dialogues. Includes: Videos, reading, discussion, knowledge-check quiz, and weekly webinar plus bonus material.

Week Three: Justice and FriendshipThis section focuses on the social and interpersonal aspect of Socrates' philosophy, particularly his views on justice and friendship. It uses illustrations from the his life, such as how he coped with political turmoil in Athens, both under the democratic regime and the Thirty Tyrants. It explores what the virtue of justice means in the Socratic dialogues. Includes: Videos, reading, discussion, knowledge-check quiz, and weekly webinar plus bonus material.

Week Four: Courage and Facing DeathThis section focuses on Socrates' famed composure and bravery. It uses illustrations from his life such as the events of his trial and execution as illustrations. It explores what the virtue of courage means in the Socratic dialogues. Includes: Videos, reading, discussion, knowledge-check quiz, and weekly webinar plus bonus material.

Includes: videos, quotes from Socrates, recommended reading, discussion questions, knowledge-check quiz, plus bonus materials.

Please feel free to email me if you have any questions or suggestions. As always, thanks very much indeed for all of your support!

Warm regards,

Donald Robertson

PS. Don’t forget that you'll automatically get $50 off (the standard price of $199) as a reward for subscribing to my email newsletters if you enroll now.

July 20, 2023

Tips for Practical Stoicism in Everyday Life

Elliot Chung, a student at Phillips Academy Andover, interviewed me recently for his new Philosophy for the Modern Mind podcast, and we decided to share our conversation on this podcast as well. We talk in particular about how Stoicism could be of practical benefit to young people, and the challenges they face today.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Coming soon! How to Live Like Socrates

Socrates was the first to call philosophy down from the sky, to place it in cities, to introduce it even into homes, to force it to consider life and customs, good and evil. – Cicero

Today enrollment opens for my online course, . The course will start on Sunday 30th of July, and lasts four weeks. I’m looking forward to helping new students apply Socratic philosophy every day to achieve a more meaningful and fulfilling life. It's great to be back, discussing my favorite philosopher! I’m currently working on a new book about Socrates so have lots to discuss from my ongoing research. This course only runs once or twice a year, when I can spare the time from writing, so don’t miss out.

The best news is, if you sign up now, as a thank you for being one of my newsletter subscribers, you get the best price! Just click any of the links or buttons in this email and you will automatically find a special time-limited discount of $50 off the standard course price has already been applied.

Why not join me? If you have any questions at all about what just hit reply to this email and let me know and I’ll get right back to you, or check out the website to .

NB: If you are a Founding member of my Substack newsletter, you will be eligible for free enrollment on this course – just email me to claim.

Warm regards,

Donald Robertson

Thanks for being a Substack newsletter subscriber. We hope you value being notified of forthcoming courses but if you think you’re receiving these emails in error please just hit the unsubscribe link below.

July 18, 2023

Nodependency: How to Fall out of Love

How do you get out of a toxic relationship? Well, if we were smart, we’d ask some people who have already done it. If you do this, you’ll tend to find at least one common theme that stands out pretty clearly. They finally realized that the person in question was doing them more harm than good. There’s something odd about that, though. Many people who are still in ongoing toxic or abusive relationships will tell you they already know that it’s bad for them. They nevertheless feel as if they can’t leave. So we have a paradox. What’s going on?

Photo by Burst on Unsplash

Photo by Burst on UnsplashWell, again, if you ask some people who have been through this, but found the courage to leave, “What do you mean?”, they often give similar answers. They will say things like “I knew intellectually that it was doing me harm but it took me a while to really accept the truth at an emotional level!” or “I knew in my head but then something happened that made me realize how bad things had become!” You could say they’re “in denial” but there’s another way of looking at it, which I think may often be more helpful.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Our unwillingness to end a toxic relationship can be seen as a particular example of a much more general, and very common, problem. Why do we continue doing things that we know are not in our best interests? As Ovid said, though I see the better path, and approve of it, I end up following the worse. Why? The short answer is: salience.

We tend to respond emotionally to information that is more salient and vivid, or jumps out at us. We all know that somewhere in the world, right now, a child is starving. That knowledge doesn’t us hit us as hard, though, as actually seeing it on television — having it right before our eyes. People who have bad habits or addictions sometimes manage to change their behavior by making the negative consequences of their actions more salient. Individuals in toxic relationships likewise, often free themselves, eventually, by doing the same thing.

How do you go from “knowing intellectually” that you need to change to an “emotional realization”, one that actually changes how you feel, and motivates you to take action? In my experience, there are three basic steps that can help you a lot in this regard.

Filling in gaps in your knowledge, by making it more detailed and comprehensive

Reminding yourself frequently of your reasons for change, until they become extremely familiar

Visualizing the more serious consequences of your current situation, so that they evoke a stronger emotional reaction

Let’s look briefly at each of these strategies in turn.

1. Filling in the gapsSo we said that most people have an “intellectual” knowledge of the problem but, on closer inspection, in many cases, that turns out not to be true. In cognitive therapy sessions, early on, we’ll often ask clients what the most likely consequences would be if they continued in their existing pattern of behavior. You can ask what the likely consequences will be if you continue in your current relationship. Typically, individuals who struggle to change are more focused on the short-term consequences. Try specifically asking yourself what the consequences will be for you longer-term if you stay in the relationship.

We typically weigh-up the pros and cons, or benefits and costs, of a course of action. For simplicity, though, if you’re doing self-help rather than psychotherapy, you may find it easier simply to list the negative consequences or harm that comes from your current course of action. Sometimes this is called an “annoyance review”. For example, a smoker might make a list of their five main reasons for wanting to quit cigarettes: the cost, the health risks, the example set to their children, and so on. The trick is to push yourself beyond your current understanding by pressing yourself at least a little and repeatedly asking “And is there anything else?”

Some people are good at this and come up with lots of reasons for leaving their partner, if the relationship is no good. Other people come up with a few, but then draw a blank. That’s a sign that there’s a gap, and filling these gaps can change our motivation, and our actions. So, again, push yourself a little further than normal. Structured questions can help. For instance, what harm, long-term, does the current relationship do in different areas of life.

What impact would it likely have on your physical and mental health?

How does it affect your other relationships — including friends and family?

Would it be likely to harm your career, work life, or education, in any way?

What about your other interests, such as spirituality or hobbies — how are they being affected?

How will it impact your self-esteem and self-confidence, in the long-run, and where will that leave you in life?

By looking at the consequences of staying in a toxic relationship from different perspectives, you can often flesh out your motives for change, and that makes them stronger and more compelling.

Of course, there will usually also be perceived benefits to the relationship. Often it feels like these are what keep you in a bad relationship, even though you know all the harm it is doing to you. I’m trying to keep my advice here simple. If you were working with a counselor or a therapist it would be easier to spend more time working through all the angles. However, if you find it’s too unbalanced to only consider the disadvantages of the relationship or you feel it would be important to consider the advantages in order to address them, then you should certainly do so.

The most common pros that keep people locked into an unhealthy relationship are short-term. They tend to be forms of avoidance. Probably the biggest ones that you’ll hear is that the individual doesn’t want to hurt their partner or they’re scared that they’ll be alone, if they confront them or decide to leave. So staying in the relationship has the perceived advantage of avoiding that discomfort. You should ask yourself whether these and other perceived benefits are real, though. How do they compare to the long-term consequences of staying? Do short-term benefits such as avoiding confrontation really outweigh long-term benefits like freeing yourself from all the problems we explored above, and being able to move on in your life?

2. Reminding yourself of your reasonsNow we’re getting more into the question of recall and salience. Even if you can list all of the reasons why you should leave, and have filled all the gaps in your knowledge, you may still forget them sometimes. We need to have beliefs ready-to-hand in order to benefit from them. You can’t do that easily with a long-winded argument. So what’s the solution? We abbreviate your reasons, and construct simple reminders.

Someone who wants to lose weight might write down their three main reasons for doing exercise on a cue card, which they carry around in their pocket. Putting your reasons down on paper, or anywhere you can see them regularly, is a good idea. You may also make it a part of your routine to read them aloud, or whisper them to yourself, each day. You may also benefit from doing this whenever you feel that you need a reminder, or to motivate yourself to make a tough decision, or do something you’ve been avoiding. Write down your 3-5 main reasons for wanting to end a relationship, for example, and read it to yourself every day.

You don’t need to go into detail, because you’ve already done that. Just write down a few short phrases or keywords such as: “violence”, “self-esteem”, “children”, or whatever works for you. Of course, you might not want someone else to read this, so you can also just draw symbols, write initials, or use a secret code word. It doesn’t matter, as long as you can remember what it means.

3. Visualizing the ConsequencesThis is my favorite technique, as we’re now getting further away from verbal cognition and into the more experiential realm of mental imagery. This is where you make your motives come alive, giving them more vividness and salience in your mind’s eye. Picture the long-term disadvantages of staying in the relationship, drawing on the questions that you answered earlier. If you don’t change, where will you find yourself ten or twenty years from now? Imagine how it will affect your physical and mental health. Picture the effect on your self-confidence and self-esteem, and the wider impact on your relationships, and other areas of life.

You can make mental imagery more powerful and evocative by relaxing, removing distractions, and spending more time on the exercise. You can also make it more powerful by trying to bring in your other senses, such as imagining sounds and sensations, or even smells. Of course, do not do this if you find it too emotionally overwhelming or disturbing. If you are prone to panic attacks or suffer from other mental health problems, visualizing painful situations needs to be approached carefully, and is often best done under the supervision of a therapist.

The more often you do this the more effect it will have on your emotions and behavior. For instance, it could be part of your daily routine to read your cue-card three times, under your breath, as a reminder, then close your eyes and picture the consequences of staying in the relationship for a few minutes.

Now, you would be right to say that some people may find this too negative. Again, I’m presenting a simplified approach. If you have the time, or you are working with a therapist or counselor, you might want to visualize two contrasting futures. Start with the long-term consequences of staying in the unhealthy relationship, as described above. However, if you feel ready to do so, you may want to follow this by picturing the long-term consequences of leaving, or taking some other form of constructive action. How different would your life be five or ten years from now, if you found the courage to change things? Again, take time to explore the wider impact across different aspects of your life. How would moving on benefit your self-confidence and self-esteem? How would it enhance your mood and your physical and mental health? How would it affect your other relationships? And what positive impact would it have on your work or studies?

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

ConclusionI want to make it clear that I’m not proposing this advice as an alternative to counseling or therapy. There are many other strategies that you could use to help yourself. However, it seems to me that this is simple advice, which can potentially benefit almost anyone. People who are looking for self-help often find it gives them a lot to think about but not much practical advice. If you feel that you’re stuck in a bad relationship, or you’re struggling with a similar problem, there are ways you can probably help yourself solve the paradox Ovid described when he said we see the better path, and approve of it, but end up following the worse. You can train your mind, and your emotions, so that your arms and legs, and the rest of your body, end up following the better course, after all.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

July 16, 2023

How Did Marcus Aurelius Pray?

The Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, in his philosophical reflections, described how Stoics might pray as a form of self-improvement. He describes an approach to prayer that resembles the use of affirmations, and could be of value even to atheists or agnostics as a self-help technique.

First of all, Marcus does mention a simpler and more direct approach to prayer:

A prayer of the Athenians: ‘Rain, rain, dear Zeus, on the ploughlands and plains of Attica.’ We should either pray in this simple and artless fashion, or not pray at all. (Meditations, 5.7)

According to legend, during one famous battle his legionaries were trapped on a plain, surrounded on all sides by numerous Quadi, and dying of thirst under the sun. In one version of the story, Marcus prayed and the heavens opened up pouring rain down upon his men, which they caught in their helmets and gulped down as they fought their way to freedom. This was known as “The Rain Miracle” of Marcus Aurelius.

Elsewhere in The Meditations, though, Marcus says something much more subtle and philosophical about prayer. He asks why those believing that the gods truly have power to help pray for external things rather than for their own freedom and wellbeing. Ironically, rather than praying for rain, in general, a Stoic should pray for strength of character and to neither crave the rain nor be afraid of the drought.

If they have power, why do you not pray to them to grant you the ability neither to fear any of these things nor to desire them, nor to be distressed by them, rather than praying that some of them should fall to you and others not? For surely, if the gods have any power to help human beings, they can help them in this. But perhaps you will object, ‘They have placed this in my own power.’ Well then, would it not be better to make use of what lies within your power as suits a free man rather than to strain for what lies beyond it in a slavish and abject fashion? In any case, who told you that the gods do not assist us even in things that lie within our power? Begin at least to pray so, and you will see. (9.40)

The last remark suggests that Marcus himself tried praying in this manner. He goes on, in the same passage, to give an example:

That man prays, ‘May I come to sleep with that woman,’ but you, ‘May I not desire to sleep with her.’ Another prays, ‘May I be rid of this man,’ but you, ‘May I no longer wish to be rid of him.’ Or another, ‘May I not lose my little child,’ but you, ‘May I not be afraid of losing him.’ In a word, turn your prayers round in such a way, and see what comes of it. (9.40)

Elsewhere, Marcus mentions two more examples of short Stoic prayers. The first expresses his attitude of Stoic acceptance or amor fati:

“Nature, give what it pleases you to give, and take what it pleases you to take” (Meditations, 10.14).

In another passage, he provides a slightly longer Stoic prayer addressed to universal Nature, the “Dear City of Zeus”, which expresses the same basic attitude of acceptance:

Everything suits me that suits your designs, O my universe. Nothing is too early or too late for me that is in your own good time. All is fruit for me that your seasons bring, O Nature. All proceeds from you, all subsists in you, and to you all things return. (Meditations, 4.23)

Stoics, in other words, pray as a means of expressing certain philosophical attitudes that it is within their own power to adopt. We could perhaps compare this to the repetition of a mantra or affirmation. They’re not so much asking the gods for help as reminding themselves to think about events in the way they’re describing. Modern Stoics, even if they’re atheists or agnostics, could adapt these “prayers” for use in daily life as a technique of self-improvement.

If you’re interested in learning more about Stoic philosophy and how it can be applied to daily living, see my latest book How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius.

📝 Read this story later in Journal.

July 13, 2023

Anticipate future adversity

When you are on the point of putting your hand to some undertaking, remind yourself what the nature of that undertaking is. If you are going out of the house to bathe, put before your mind what happens at a public bath—those who splash you with water, those who jostle against you, those who vilify you and rob you. And thus you will set about your undertaking more securely if at the outset you say to yourself, “I want to take a bath, and, at the same time, to keep my moral purpose in harmony with nature.” And so do in every undertaking. For thus, if anything happens to hinder you in your bathing, you will be ready to say, “Oh, well, this was not the only thing that I wanted, but I wanted also to keep my moral purpose in harmony with nature; and I shall not so keep it if I am vexed at what is going on.”

July 11, 2023

Epictetus on Nero

Epictetus, the great teacher, played his part in changing the leadership of Rome from the swill he had known in the Nero White House to the power and decency it knew under Marcus Aurelius. — Stockdale, Thoughts of a Philosophical Fighter Pilot

The Emperor Nero was, it’s fair to say, one of the most controversial Roman emperors. Some people believe that his bad reputation is unjustified and solely due to the propaganda of a handful of biased senators from later generations. I think that’s a difficult claim to substantiate. We shouldn’t dismiss historical evidence as biased without good reason. Moreover, in this article, I’m going to focus on some direct criticism of Nero which comes from a source much closer to him. A famous contemporary of Nero’s, who was not a senator, did not write popular histories, and was neither wealthy nor a member of the political elite. I’m speaking of the Stoic philosopher Epictetus.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Epictetus was born into slavery. Indeed, his name simply means “acquired”. He was the property of an influential freedman called Epaphroditus, who served as Nero’s Greek secretary. Based on his comments in the Discourses about letter-writing, I think it’s possible that Epictetus, while enslaved, worked as a Greek scribe for his master. Epaphroditus was the one who first alleged that a plot was underway to kill Nero and replace him with a Roman senator called Piso. Nero accused Seneca of being involved in the so-called “Piso conspiracy”, and had him executed, by forced suicide. The emperor took this opportunity to execute or exile many of his political opponents.

Nero was one of only a handful of Roman emperors who were refused the honor of deification by the Senate after their death.

After the purges, Nero’s behavior became even more erratic. He allegedly kicked his pregnant wife, Poppea, to death. The emperor then had a young boy called Sporus castrated, dressed him as a bride, and took him as his wife, in a full wedding ceremony — the boy reputedly bore a remarkably resesemblance to Poppea. With a young eunuch standing in for his dead wife, and appearing beside him in public dressed as an empress, Nero became a laughing-stock among both the Senate and the legions. The following year, the governor of Gallia Lugdunensis (France) instigated a rebellion, which failed, but nevertheless stoked a looming civil war between Nero and his general Galba, governor of Hispania (Spain). Nero was declared a public enemy by the Senate, and Galba named emperor instead.

Awakening to find his praetorian guards had abandoned him, Nero fled Rome in disguise. He was one of only a handful of Roman emperors, such as Caligula and Commodus, who tried to deify themselves while living but were refused the honor of deification by the Senate after their death. Epictetus was probably aged around eighteen in 68 CE, when Nero killed himself in order to avoid capture by soldiers loyal to Galba and the Senate — Epaphroditus assisted him in committing suicide.

Vice Admiral James Stockdale, in his characteristic style, gives the following account of the drama at the imperial court, which Epictetus knew as a youth:

He was “bought cheap” by a freedman named Epaphroditus, a secretary to Emperor Nero. He was taken to live at the Nero White House at a time when the emperor was neglecting the empire while he toured Greece as actor, musician, and chariot race driver. When home in Rome in his personal quarters, Nero was busy having his half-brother killed, his wife killed, his mother killed, his second wife killed. Finally, it was Epictetus’s master Epaphroditus who cut Nero’s throat when he fumbled his own suicide as the soldiers were breaking down his door to arrest him. — Stockdale, Thoughts of a Philosophical Fighter Pilot

In fact, it’s possible that Epictetus did not arrive in Rome until shortly after Nero’s death. In any case, he would have witnessed the aftermath, and he would have been able to hear all about Nero directly from Epaphroditus and the other members of his household.

Marcus Aurelius on NeroThe Emperor Marcus Aurelius held Epictetus in very high regard. They both admired the Stoic Opposition who openly defied Nero’s rule. In the Meditations, Marcus does not mention Seneca, who sided with Nero for most of his reign, wrote his speeches, and defended him in the Senate. Instead Marcus mentions his admiration for Thrasea, the leader of the Stoic Opposition, who was executed by Nero, and Helvidius, his son-in-law, whom Nero exiled (Med., 1.14). Marcus only mentions Nero once. He compares Nero to the legendary tyrant Phalaris, when giving an example of someone, “pulled by the strings of desire”, as degenerate as a wild beast (Med., 3.16). He makes it clear, in this passage, that Nero symbolizes the opposite of a good man. Marcus therefore was not a fan of Nero but rather of the Stoic Opposition who resisted his rule in the senate.

Regarding Marcus’ personal attitude toward Nero, we also have the testimony of Roman historians. Herodian claims that when he was faced with the prospect of his son, Commodus, becoming emperor in his teens, Marcus Aurelius “was disturbed also by the memory of those who had become sole rulers in their youth”, especially Nero, who “had capped his crimes by murdering his mother and had made himself ridiculous in the eyes of the people.” The Historia Augusta likewise says that Marcus was afraid Commodus might become “another Nero”, and that in a letter Marcus said “Nero had deserved to die”, by which he meant that he inevitably faced the rebellion, which led to his suicide, because he was such a bad ruler. These histories, though frequently unreliable, are consistent with what Marcus himself writes about Nero being a wild beast, and a tyrant, in the Meditations. As we shall see, Marcus was in total agreement with Epictetus in this regard.

Epictetus’ point here is that Nero is not a morally good person, but a wretched one…

Epictetus on NeroEpictetus, like Marcus, has nothing positive to say about Nero. Moreover, although men run around seeking to win the favor of kings and emperors, he says, it is not actually in the power of such rulers to grant them happiness or rather flourishing (eudaimonia). If it were, he says, then “Nero would be flourishing (eudaimon)” but, of course, he was not. Epictetus adds that even the great Homeric king of kings, Agamemnon, who instigated the Trojan War, did not truly live a good life, or flourish, “though he was a better man than Nero” (Discourses, 3.22). Epictetus’ point here is that Nero was not a morally good person, but a wretched one, and therefore could not even benefit himself, let alone others, despite wielding supreme power as emperor.

In another striking passage, Epictetus uses the metaphor of coinage to illustrate the stamp of a good man’s moral character:

What is the stamp of his opinions? It is gentleness, a sociable disposition, a tolerant temper, a disposition to mutual affection. Produce these qualities. I accept them: I consider this man a citizen, I accept him as a neighbor, a companion in my voyages. (Discourses, 4.5)

This is contrasted with the character of Emperor Nero, who is none of these things and not a good man.

Only see that he has not Nero's stamp. Is he passionate [lit. “quick to anger”], is he full of resentment, is he fault-finding? If the whim seizes him, does he break the heads of those who come in his way? (If so), why then did you say that he is a man? (Ibid.)

Indeed, Epictetus exclaims “It is the stamp of Nero. Throw it away: it cannot be accepted, it is counterfeit.” He seems to be using the analogy of coinage cleverly here. George Long, the translator, writes in his notes: “Perhaps Epictetus means that some people would not touch the coins of the detestable Nero.” It’s possible that coins stamped with Nero’s image were no longer classed as legal tender, after he was condemned by the Senate, and that some were melted down and recast, although many do survive today.

As far as Epictetus is concerned, just as coins stamped with Nero’s image are “counterfeit”, Nero himself was a counterfeit human being. He was not even a real man but rather a brute, an irrational beast. Marcus Aurelius, we saw earlier, says the same thing of Nero, perhaps influenced by this passage. To be more specific, Epictetus describes Nero’s character here as “quick to anger” (ὀργίλος), “bitter and complaining” (μηνιτής), and “fault-finding” or “argumentative” (μεμψίμοιρος).

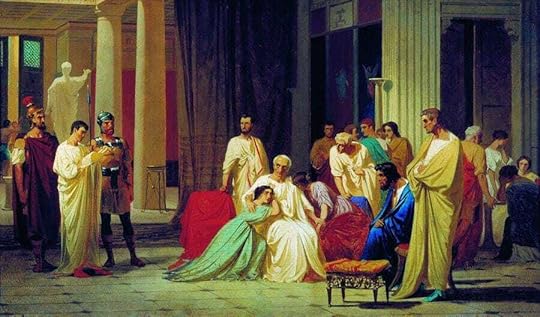

Quaestor Reading the Death Sentence to Senator Thrasea Paetus, by F. BronnikovThe Stoic Opposition to Nero

Quaestor Reading the Death Sentence to Senator Thrasea Paetus, by F. BronnikovThe Stoic Opposition to NeroEpictetus, by contrast, admired the Stoic Opposition and others who stood up to Nero’s tyranny. At the beginning of the Discourses, Epictetus recounts an anecdote in which Thrasea Paetus, the leader of the Stoic Opposition, is boasting of his political defiance against Nero.

Thrasea used to say, I would rather be killed today [by Nero] than banished tomorrow. What then did Rufus say to him? If you choose death as the heavier misfortune, how great is the folly of your choice? But if, as the lighter, who has given you the choice? Will you not study to be content with that which has been given to you? (Discourses, 1.1.)

Musonius Rufus, Epictetus’ own Stoic teacher, was a mentor to the Stoic Opposition. He appears to be counseling Thrasea not to seek out death at Nero’s hands by deliberately provoking him, but to oppose him wisely, and accept death when it comes. Nero finally ordered his execution in 66 CE. Thrasea was revered by later generations of Romans as a famous political martyr.

Epictetus also admires the Cynic philosopher Demetrius, a friend of Thrasea, who was with him when he was executed. He says that Demetrius neither flattered nor feared tyrants, and he praises the Cynic for standing up to Nero. According to Epictetus, when Nero wanted to execute Demetrius, the philosopher simply replied, “You threaten me with death, but nature threatens you” (Discourses, 1.25).

Epictetus particularly admired Paconius Agrippinus, one of the Stoic Opposition, because he says he would not even consider debasing himself on Nero’s behalf.

For this reason, when Florus was deliberating whether he should go down to Nero's spectacles, and also perform in them himself, Agrippinus said to him, Go down: and when Florus asked Agrippinus, Why do not you go down? Agrippinus replied, Because I do not even deliberate about the matter. For he who has once brought himself to deliberate about such matters, and to calculate the value of external things, comes very near to those who have forgotten their own character. (Discourses, 1.2)

The reference is to large festivals organized by Nero where the attendees were surrounded by armed guards, and forced to applaud. Nero sometimes ordered Roman elites who had fallen out of favor with him to perform on the stage, in order to humiliate themselves before the public. If they refused, they were beheaded. Epictetus describes them worrying: “But if I do not take a part in the tragic acting, I shall have my head struck off.” This is reminiscent of a passage in Plato’s Apology, where Socrates says that a good man, when facing danger, would not even weigh-up the chances of living or dying, but would simply choose to do what he considers honorable.

Epictetus also praises a senior Roman senator called Plautius Lateranus who exhibited courage when Nero ordered him beheaded, during his purge of the Piso conspiracy.

Will you not stretch out your neck as Lateranus did at Rome when Nero ordered him to be beheaded? For when he had stretched out his neck, and received a feeble blow, which made him draw it in for a moment, he stretched it out again. (Discourses, 1.1)

The man who was ordered to execute Lateranus was reputedly one of his co-conspirators but Lateranus kept absolute silence and did not betray his involvement to Nero. Epictetus makes it clear to his Stoic students that they should do nothing to aid a tyrant like Nero, even when they are threatened with execution.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

ConclusionThere are several more passages where Epictetus praises those who defied Nero’s rule, and accused him of being a tyrant. Indeed, we’re told that Thrasea, the leader of the Stoic Opposition was famous for saying, paraphrasing Socrates, “Nero may kill me but he cannot harm me.” Arrian chose to close the Enchiridion of Epictetus with the original version: “Anytus and Meletus may kill me but they cannot harm me.” Given the praise that Epictetus heaps on the Stoic Opposition, I think his readers would be likely to take this concluding quote as a subtle nod of respect to Thrasea.

It’s perhaps worth mentioning that the writer Philostratus tells us that Musonius Rufus, Epictetus’ beloved Stoic teacher, was imprisoned and later exiled by Nero. He was forced to do hard labor on the subsequently abandoned canal through the Isthmus of Corinth, in Greece. If it had worked, this canal would have been a marvel of engineering. The Cynic philosopher Demetrius, a native of Corinth, was shocked to find the Stoic in chains digging with a pickaxe. Musonius reputedly struck the earth again, then looked up and said:

‘Do I upset you, Demetrius, to be digging the isthmus for Greece? I wonder what you would have thought if you saw me playing the cithara like Nero?’

Musonius meant that at least he was doing something constructive, unlike Nero, who was vain and obsessed with his own celebrity. (The cithara is a stringed instrument, like a harp.) Nero was performing music at his own festivals, to the fake applause of a captive audience, while the Stoic, despite being in chains, was helping to build a canal, which could actually benefit the whole empire.

Epictetus was the slave of Nero’s Greek secretary, one of his most senior courtiers, so his negative account of Nero’s character is about as close as we get to first hand testimony from a critic of Nero. In stark contrast, the praise that Seneca heaps on Emperor Nero, often makes for uncomfortable reading. For example:

You, Caesar, can boldly say that everything which has come into your charge has been kept safe, and that the state has neither openly nor secretly suffered any loss at your hands. You have coveted a glory which is most rare, and which has been obtained by no emperor before you, that of innocence. Your remarkable goodness is not thrown away, nor is it ungratefully or spitefully undervalued. Men feel gratitude towards you: no one person ever was so dear to another as you are to the people of Rome, whose great and enduring benefit you are. — Seneca, On Clemency

Seneca was writing early in Nero’s rule, but shortly after the murder of the emperor’s young half-brother, and rival for the throne, Britannicus. Nevertheless, he emphatically repeats several times the claim that Nero is completely innocent of any wrongdoing and “has never shed the blood” of another Roman. It seems to me that Seneca, a famous rhetorician, would have been taken by his elite Roman audience as skirting around the fact that Britannicus’ blood was, indeed, never spilled, as he was poisoned. In any case, despite Seneca’s support, and very public defense of him, Nero would repay him, in the end, by ordering him to take his own life.

According to the historian, Cassius Dio, Thrasea, who protested against Nero by walking out of the Senate, told his friends, including many fellow-Stoics:

If I were the only one that Nero was going to put to death, I could easily pardon the rest who load him with flatteries. But since even among those who praise him to excess there are many whom he has either already disposed of or will yet destroy, why should one degrade oneself to no purpose and then perish like a slave, when one may pay the debt to nature like a freeman? As for me, men will talk of me hereafter, but of them never, except only to record the fact that they were put to death. — Thrasea, quoted in Cassius Dio

Thrasea was eventually executed for refusing to praise Nero; Seneca had already been executed, by this time, despite having publicly praised Nero to excess and “loaded him with flatteries” for many years. It often puzzles modern readers that Seneca’s name is never mentioned in any surviving Stoic text, despite the fact the we know, e.g., that Marcus Aurelius had read him. It is possible that the above passage provides the explanation, by suggesting that Thrasea may have instigated a damnatio memoriae against Seneca, among his fellow-philosophers, because of the latter’s support for Nero.

Epictetus, likewise, warns his students not to flatter tyrants, and never to become beholden to them. He was familiar with how Nero persecuted philosophers, such as his own teacher, Musonius. He may even have had a ringside seat to observe the purges following the Piso conspiracy, or at least its chaotic aftermath. In any case, I think it’s beyond dispute that Epictetus viewed Nero as a very bad emperor. Nero was a man full of pathological anger, consumed by bitterness, obsessed with finding fault and taking revenge, who had his critics beheaded on a whim, says Epictetus. The men who stood up to him are moral heroes, and Epictetus presents them to his students as Stoic exemplars, or role models to be emulated. Nero, said Epictetus, was a wild beast, not a real man, and Marcus Aurelius agreed with that verdict.

July 6, 2023

Stoic Philosophy and Alcoholism

How to drink like a Roman emperor, if that emperor is Marcus Aurelius. In this episode I explore the relationship between Stoic philosophy and the Twelve Step Program of Alcoholics Anonymous, discussing how Stoicism can help those suffering from alcoholism, as well as their friends and families. I spot parallels between the Twelve Step advice and Stoic teachings, and give examples from the life of Marcus Aurelius. I talk about how his wayward brother, and co-emperor, Lucius Verus, was almost certainly an alcoholic. Also, Frank, retired NYPD police officer, shares his experience of combining Stoicism the Twelve Step Program.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The original article is available on Substack, titled How to Drink Like a Roman Emperor.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.