Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 29

July 5, 2023

Join us for On Seneca: Anger, Fear, and Sadness

We’re delighted to announce that registration is now open for the forthcoming Plato’s Academy Centre virtual event On Seneca: Anger, Fear, and Sadness. Registration is free of charge; donations are welcome. Don’t worry if you’re in another time zone as recordings will be available afterwards. Also, register now to be entered for a chance to win in our special book giveaway — details to be announced soon!

I will be hosting the event, along with my friend, Anya Leonard, of . So who is speaking?

David Fideler, the author of recent self-help bestseller, Breakfast with Seneca: A Stoic Guide to the Art of Living

Prof. James Romm, author of the biography, Dying Every Day: Seneca at the Court of Nero, and translator of the self-help books for Princeton’s Ancient Wisdom series: How to Die, How to Give, and How to Keep your Cool, which are based on Seneca’s works

Prof. Christopher Star, author of The Empire of the Self: Self-Command and Political Speech in Seneca and Petronius

Lalya Lloyd, classicist and translator of a forthcoming edition of Seneca’s On Tranquillity

Prof. Margaret Graver, author of Stoicism and Emotion and Seneca: The Literary Philosopher

We think you’ll agree that’s already an amazing program, but we’re still confirming additional speakers. So stay tuned!

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

July 2, 2023

Stoic Mindfulness

Attention (prosochê) is the fundamental Stoic spiritual attitude. It is a continuous vigilance and presence of mind, self-consciousness which never sleeps, and a constant tension of the spirit. Thanks to this attitude, the philosopher is fully aware of what he does at each instant, and he wills his actions fully. (Hadot, 1995, p. 84)

Ancient Stoic philosophy contains a bewildering array of psychological practices. In my first book on the subject, The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (2010), I tried to provide an overview of them and counted about eighteen altogether. I’ve often asked myself, though, which is the most fundamental psychological technique of Stoicism — the one that people should focus on learning first.

There are certainly different ways of approaching this question. However, one obvious answer comes from looking at the famous Handbook (Encheiridion) of Epictetus. The opening sentence says: “Some things are up to us and other things are not.” Modern Stoics call this “The Dichotomy of Control” and it can reasonably be said that this premise is the psychological foundation upon which the rest of the Handbook builds. The Earl of Shaftesbury, an early modern scholar of Stoicism, called it the “sovereign precept” of Stoicism.

In his discourse On Attention, Epictetus elevates this precept to a daily practice of continual Stoic mindfulness. The Greek word used here for “attention” is prosochê (προσοχή). In modern Greece it’s often used on warning signs where in English we might write “Caution!” or “Beware!” — pay attention, in other words. Epictetus, though, appears to be specifically describing attention to our ruling faculty (hegemonikon), i.e., our use of value judgements. The most important criterion to which Stoics must pay attention when making value judgements is that only what is up to us, our own volition, can be truly good or bad — everything else is (ultimately) indifferent.

Epictetus on Losing AttentionEpictetus begins by warning his students that when they have allowed their attention to lapse in this regard, they cannot simply recover it whenever they choose to do so. They should bear in mind that by failing to pay attention today to the most important things, our lives will be worse tomorrow. What causes most trouble in life is getting into the habit of not paying attention to our ruling faculty at certain times, which further leads to the habit of postponing paying attention at other times, and so on. Epictetus warns his student that to postpone paying attention in this way is to postpone the fundamental goal of life — which Stoics call “living in agreement with Nature”. It also means we’re putting off engaging in proper conduct, and achieving our own true fulfilment and flourishing as human beings (eudaimonia).

Epictetus’ students appear to have felt that it might be in their interests sometimes to delay making the effort to pay attention in this regard. They say they lose themselves in play or singing and become forgetful of how they’re using their ruling faculty to make value judgements. Epictetus argues that if it were good for them to abandon paying attention sometimes it would surely be even more beneficial to stop doing so completely. However, if it’s not generally profitable to let our attention wander, he asks, why not maintain it constantly? Epictetus tells his students that they could have played or sang while continuing to pay attention to their own ruling faculties.

Is there any part of life to which attention does not extend? Will you do anything in life worse by using attention and better by not attending at all? And what things in life are done better by those who do not do them with attention? Does he who works in wood work better by not paying attention? Does the captain of a ship manage it better by not attending?

When we have let our mind loose, he says, by allowing our attention to lapse, we no longer have the power to recall it to reason whenever we choose but rather we allow ourselves to be driven by our instincts.

The famous Daoist scripture Dao de Jing said that the wise man is “cautious like someone crossing a wintry stream”. Epictetus likewise says in the Encheiridion that just as someone walks very cautiously when he has to take care not to step on a sharp object or sprain his foot, the Stoic is always mindful, in his every act, not to harm the ruling faculty of his own mind by lapsing into folly or vice. Epictetus’ own Stoic teacher, Musonius Rufus, likewise said very bluntly that we should never relax our attention because “to let one’s mind go lax is, in effect, to lose it” (Sayings, 52). To abandon mindfulness is, in a sense, to become mindless.

Beware of the dog! (Prosochê skylos)Attention to What?

Beware of the dog! (Prosochê skylos)Attention to What?To what should Stoics pay attention, he asks his students. First and foremost, to the general principles of their philosophy, which they should have ready-to-hand at all times — neither falling asleep, awakening in the morning, eating, drinking, nor conversing with other people without having these basic precepts in mind. In particular, he says that we should continually pay attention to the fact that “no man is master of another man’s will, but that in the will alone is the good and the bad.” In other words, Stoics should be continually mindful of the fact that other people’s actions, or opinions, are ultimately indifferent to them, because all that matters is that their own mind is in agreement with Nature, by which the Stoics mean that they’re living in accord with reason and virtue. As long as I pay attention to this basic realization, I have no cause to be disturbed by external events. As Epictetus says elsewhere, “It’s not events that upset us but our judgements about them” (Encheiridion, 5).

He gives his students a simple example. Suppose that I get the impression that another person isn’t very pleased with me — he’s annoyed with me. The Stoic, paying continual attention to his own ruling faculty, should ask himself: “Is his opinion up to me then?” No, it’s not. My opinion of him is up to me, however, and I should remember to take full responsibility for how I choose to view things. Why should I be disturbed therefore as long as I remember to pay attention to the fact that his opinions aren’t truly up to me? Epictetus actually says his students should only be concerned how God (Zeus) might judge them or perhaps those who are “close to him”, i.e., the wise.

When we firmly grasp that some conclusion necessarily follows logically from a premise, we don’t care for any man who says the opposite. Seeing plainly that 1+1=2, we ignore any fool who tries to convince us otherwise. Why then, asks Epictetus, do we allow ourselves to become upset by those who blame us, and swayed by their opinions of us. Rather we should firmly grasp the fact that virtue is the only true good, which means that other people’s opinions of us — whether they praise or censure — are ultimately indifferent to us. The majority of people don’t know right from wrong, so we should be as indifferent to their opinions as a shoemaker would be to the advice of someone who knows nothing about making shoes. We shouldn’t, in other words, be easily swayed by praise or blame coming from ignorant people with regard to the most important things in life. We have to depend upon our own judgement and that requires unwavering attention to the use we make of it.

Wisdom and JusticeWe should therefore always have these basic rules of Stoicism ready-to-hand, paying attention to them continually, and training ourselves to undertake every daily task in this manner. Our mind should be kept focused on the fundamental goal of “living in agreement with Nature”, which means “pursuing nothing external, and nothing which is up to others.” Rather we should pursue our own flourishing, first and foremost, by remembering that we are rational beings, and aiming to live with wisdom.

We can deal in external things (“preferred indifferents”), to some extent, but only insofar as it is reasonable to do so, without becoming emotionally attached to them. Elsewhere Epictetus compares this to players in a game throwing a ball to one another and catching it. Virtue consists in handling externals in the same sportsmanlike way, being willing to catch the ball when it’s thrown and to throw it to another when it’s appropriate to do so.

We should also remember therefore that we are social beings, and what our duties are with regard to other people, both as individuals and communities. Applying moral wisdom to our relationships constitutes the Stoic virtue of justice. We must discern when it is appropriate to play or sing, Epictetus says, and in whose presence, and what the likely consequences of doing so will be.

We must continually pay attention, however, so that we can interact with other people, in our various social roles, without compromising our own moral character and damaging our fundamental wellbeing. We must realize that true harm comes to us, says Epictetus, not from anything external but from our own thoughts and actions. As the Stoics repeatedly like to say, passions such as excessive fear and anger do us more harm than the things we’re upset about.

Conclusion: Nobody is PerfectEpictetus concludes by reassuring his students: the Stoics concede that nobody is perfect. It’s impossible, even through continual attention, to free our minds completely from vices and passions. Nevertheless, it is within our power to direct our efforts to being perfect. That’s the connotation of the very word “philosopher”, which literally means “love of wisdom”. No man can claim to be perfectly wise but we should nevertheless all aspire to become so — we should all love wisdom. We should be content, says Epictetus, if by continual attention, and the continual desire to live wisely, we at least escape a handful of errors — because we’re talking about the most important errors in life.

When you say that “tomorrow I will begin to pay attention” (to reason and the fundamental goal of life) you should always remember that you are implicitly saying that today you will let yourself be irrational, shameless, and vicious. Today, asks Epictetus, will you then be passionate and envious, and needlessly allow others to cause you pain? “If it is good to pay attention tomorrow,” he says, “how much better is it to do so today?” And because we are creatures of habit, tomorrow it will become easier to pay attention appropriately if I have already done so today.

If you’re interested in learning more about Stoic mindfulness and other practical applications of the philosophy, see my recent book How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius (St. Martin’s) for more discussion and examples.

June 29, 2023

Stoicism and the Live and Let Live Movement

In this episode, I talk with Marc J. Victor, about Stoicism and politics. Marc is an attorney in the US, where he is a certified Criminal Law Specialist, and president of the Attorneys for Freedom law firm. He is also an activist and founder of the Live and Let Live global peace movement.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

HighlightsWhy Stoicism is attracting more interest today

Misconceptions

What is the Live and Let Live Movement?

What does “live and let live” mean in terms of your philosophy?

The relationship between Stoicism and the Live and Let Live principle

How does the movement define aggression?

Our competence to avoid being victims of exploitation

Rhetoric, lawyers, and philosophy

Final question: “How could we better incorporate Stoicism into a political philosophy that could help us achieve global peace?”

Links

LinksThank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

June 28, 2023

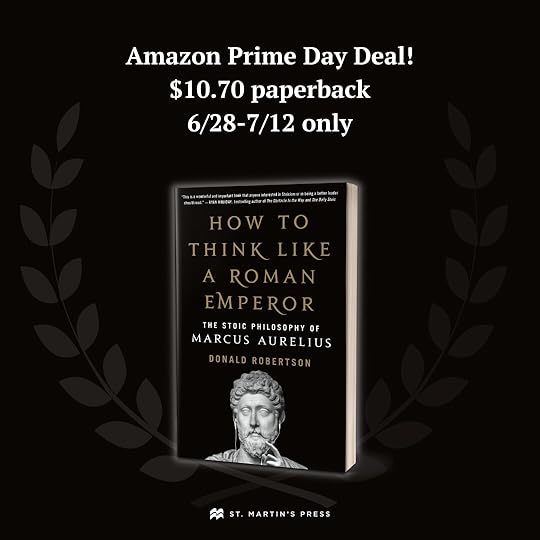

Special Offer: How to Think Like a Roman Emperor

We’re delighted to announce that Amazon have selected my book How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius as an early Prime Day Deal. That means the paperback edition of the book will be just $10.70, for Amazon Prime members, while the offer lasts! The price drop begins today, the 28th June, and only lasts a few days — so don’t miss your chance to grab a bargain!

You may also find discounts on the ebook, hardback, and audiobook editions around this time, if you’re lucky. If you’re based outside the US, check your regional Amazon site for current discounts and offers.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

About How to Think Like a Roman EmperorHow to Think Like a Roman Emperor is a self-help book about the life and Stoic philosophy of Marcus Aurelius. It is an innovative cross-genre book, combining elements of history, philosophy, and psychology.

It was reviewed in the Wall Street Journal when it was released in 2019 and has since gone on to sell over a quarter of a million copies internationally, with translations now available in about twenty different languages.

It has now been rated and reviewed over 3,000 times on Amazon, over 4,000 times on Audible, and over 9.000 times on Goodreads. Thanks for your support!

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

June 27, 2023

The Dead Emperor

Excerpt from How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius (2019). Copyright © Donald Robertson. All rights reserved.

This philosophical attitude toward death didn’t come naturally to Marcus. His father passed away when he was only a few years old, leaving him a solemn child. When he reached seventeen, he was adopted by the Emperor Antoninus Pius as part of a long-term succession plan devised by his predecessor, Hadrian, who had foreseen the potential for wisdom and greatness in Marcus even as a small boy. Nevertheless, he had been most reluctant to leave his mother’s home for the imperial palace. Antoninus summoned the finest teachers of rhetoric and philosophy to train Marcus in preparation for succeeding him as emperor.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Among his tutors were experts on Platonism and Aristotelianism, but his main philosophical education was in Stoicism. These men became like family to him. When one of his most beloved tutors died, it’s said that Marcus wept so violently that the palace servants tried to restrain him. They were worried that people would find his behavior unbecoming of a future ruler. However, Antoninus told them to leave him alone: “Let him be only a man for once; for neither philosophy nor empire takes away natural feeling.” After losing several young children, Marcus was once again moved to tears in public while presiding over a legal case, when he heard an advocate say in the course of his argument: “Blessed are they who died in the plague.”

Marcus was a naturally loving and affectionate man, deeply affected by loss. Over the course of his life, he increasingly turned to the ancient precepts of Stoicism as a way of coping when those closest to him were taken. Now, as he lies dying, he reflects once again on those he has lost. A few years earlier, the Empress Faustina, his wife of thirty-five years, passed away. He’d lived long enough to see eight of their thirteen children die. Four of his eight daughters survived, but only one of his five sons, Commodus.

Death was everywhere, though. During his reign, millions of Romans throughout the empire had been killed by war or disease. The two went hand in hand, as the legionary camps were particularly vulnerable to outbreaks of plague, especially during the long winter months. The air around him is still thick with the sweet smell of frankincense, which the Romans vainly hoped might help prevent the spread of the disease. For over a decade now, the scent of smoke and incense had been a reminder to Marcus that he was living under the shadow of death and that survival from one day to the next should never be taken for granted.

CommentsThat was an excerpt from the opening chapter of How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, which follows a short introduction about how I came to write the book and my work over the years on Stoicism. It opens with the death of Marcus Aurelius. I wanted to start the book with something dramatic. Each chapter begins with a story about some major event in Marcus’ life, based on the information we have from the various Roman histories of his reign. In most of the chapters that leads into a discussion of Stoic philosophy and psychology and the concepts and techniques he used to cope with various problems such as anger, anxiety, pain, and so on. Then there’s a detailed discussion of how Stoic techniques can actually be applied today, drawing on my experience as a cognitive-behavioural therapist and the relevant scientific research. However, the first chapter is slightly different because after describing the events surrounding Marcus’ death in some detail, it proceeds to give the reader a short introduction to Stoic philosophy — an overview.

The story of Stoicism begins with Zeno of Citium, the founder of the school, and so you’ll be introduced to various anecdotes about him and other famous Stoics. Then we focus on what the Stoics actually believed: the core doctrines of the philosophy followed by Marcus throughout his entire adult life. And we’ll address some common misconceptions about Stoicism, such as the idea that Stoics were unemotional or joyless, which is false. I tried to keep the explanation of Stoicism in this chapter as simple as possible but after reading it you should have a pretty clear idea of who the Stoics were and what they believed. Then you’ll be well prepared to begin delving into the application of Stoicism to different areas of life. For example, in the next chapter we’ll be looking at how Stoics used language and in subsequent chapters you’ll learn how they overcame unhealthy desires and bad habits, conquered anxiety, managed anger, coped with pain and illness, came to terms with loss, and even faced their own mortality.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

June 22, 2023

Plato of Athens, with Robin Waterfield

In this episode, I talk to Robin Waterfield about the life and philosophy of the Greek philosopher, Plato. Robin is a British classicist who has translated many works of Plato, Xenophon, and other Greek writers. He is also the author of several books, including the recently-published Plato of Athens: A Life in Philosophy, the first full-length modern biography of Plato in English. Robin is also a member of our board of advisors for the Plato’s Academy Centre.

HighlightsWhy is Plato “super-important” today?

The Socratic Problem — to what extent can we separate Socrates from Plato?

How eclectic was the early Academy?

How did Plato differ from the image of Socrates in his dialogues?

The relationship between Plato and Pythagoreanism

What advice would Plato give us about dealing with social media?

Final question: “Why are we born to suffer and die?”

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Links

LinksPlato of Athens, Oxford University Press

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

June 21, 2023

Andrew Tate on Stoicism

The social media influencer Andrew Tate is in the news today because he’s been charged in Romania with “rape, human trafficking and forming an organised crime group to sexually exploit women.” He is also under investigation on separate charges including “money laundering and trafficking of minors”, as reported in the media. Whenever a figure that’s in the public eye mentions Stoicism, I receive emails and messages from people, sometimes including journalists, asking me to comment.

I’m not going to comment directly on the charges Tate faces, etc., but I would like to respond to the video clip below, in which he talks about Stoicism, as I’ve been asked about it several times in the past. It’s called “Stoicism Explained by Andrew Tate” and was published eight months ago (Oct 2022) by the YouTube channel Intellectual Dark Web.

The video opens with the interviewer asking the following question:

The Meditations by Marcus Aurelius. Stoicism. [Tate: Yup, yup.] You’ve referenced Stoicism multiple times. Not getting emotional. Thinking rational. [Tate: Yup.] This was a book that you’ve subscribed to for years, what was it about Stoicism and not getting caught up in emotions and even triggering emotions that resonates with you?

The first thing I’d say is that it’s unclear from this exchange, and the remainder of the video, whether Tate has actually read the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius. The interviewer implies that he has, and Tate says “Yup”, but he doesn’t explicitly say so himself.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Stoicism versus stoicismThe second point I’d make is that the opening question explicitly frames the discussion as being about “Stoicism” (capital S), the Greek philosophy followed by Marcus Aurelius. However, it also immediately equates this with “not getting emotional”, which sounds more like “stoicism”, the modern concept of a “stiff upper-lip” coping style. These are definitely two different things and the most common misconception about Stoicism, which you find all over the Internet, is that it’s the same as “stoicism” the unemotional coping style.

It’s extremely important not to confuse these two things as a considerable body of evidence shows that “stoicism”, as measured by tools such as the Liverpool Stoicism Scale (LSS), is linked to increased risk of psychological problems. By contrast, Stoicism, as followed by Seneca, Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, is the philosophical inspiration for modern cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), the leading evidence-based form of modern psychotherapy. Tim LeBon, the research director of the Modern Stoicism organization, incidentally, recently carried out a large research study that provided clear evidence that “stoicism” (measured with the Liverpool Stoicism Scale) was statistically uncorrelated with belief in “Stoicism” (measured with the Stoic Attitudes and Behaviors Scale or SABS) — they are two different things. We really don’t want to confuse something that is known to be bad for mental health with something that is known to be good for mental health.

How do we know that lowercase “stoicism” is unhealthy? Well, for a start there’s a well-known body of scientific evidence consisting of studies conducted independently by different teams of researchers, in different countries, using a variety of methods, with different populations. There are several mechanisms by which stoicism, or having a stiff upper-lip appears to cause problems. Some of them are almost common sense. For example, individuals who score high on the Liverpool Stoicism Scale tend not to seek emotional support from friends, family members, therapists or doctors. They see their independence as a sign of toughness but, of course, it makes them less resilient, in the long-run, than people who have good social support networks and make use of them wisely.

On a more internal level, people who view something as shameful or threatening automatically pay more attention to it. If there’s a predator on the horizon, your brain should override whatever else you’re doing and give all of your attention to that threat until it’s gone. That’s a basic survival mechanism. It can backfire dramatically, though, when we view inner experiences, like feelings of anxiety or depression, as the threat. Allocating more attention to them tends to magnify them in a number of ways. Moreover, several studies provide evidence that when we try to block thoughts and feelings from our minds they may recur more frequently — a phenomenon known as the “rebound effect” or “paradox of thought suppression”.

So “stoicism”, an attitude which tries to suppress or conceal unpleasant and embarrassing emotions, can be called “toxic” in this pretty obvious regard — it tends to make us more vulnerable to mental health problems, especially over the long-term. The irony about this, of course, is that people, often young men, are attracted to stoicism because they view it as a way of being “tough”. It appears strong or tough to them, at first, to suppress painful emotions but if that causes them to become less emotionally resilient in the long term it is, of course, actually a form of weakness. It’s psychological bait and switch — your mind tricks you into thinking this seems tough but it’s actually making you weaker and more emotionally vulnerable.

Andrew Tate’s Reply

Andrew Tate’s ReplyNow, although Tate initially agrees with the interviewer saying he believed in “Stoicism” and “not getting emotional” (“Yup, yup”), he immediately seems to contradict this. He replies that “emotions are feedback” and that men are, in some ways, naturally more emotional than women. He gives the examples of heartbreak, anger and pure rage. Tate also says that “Stoicism” is not about “not feeling emotion” but rather about feeling emotion and asking why it’s happening and what the most intelligent next move would be. In a nutshell, he seems to now be arguing that strong emotions, particularly anger or rage, can be healthy, as long as they’re controlled and channelled in a positive direction — and he equates this with Stoicism, although it’s not clear if he’s still referring to Marcus Aurelius or not.

The conversation becomes a little unfocused as Tate begins talking about playing chess, being banned from social media, being the most hated man in the world, his Bugattis, etc. He goes on to say that he considers everything, good or bad, that befalls him, to be his own responsibility. He adds that sometimes he thinks his own rage is healthy whereas sometimes it’s pointless. These are his words:

I've also had times where I'm in a room by myself enraged [Tate laughing as he speaks] sitting there going “this is no good for anybody, I need to just calm the f*** down!”

“Emotions are feedback,” he continues, “but Stoicism is the ability to process them.”

That’s what you need to be learned as a man. You’re never going to be able to turn them off, you’re going to feel them, you’re going to have to learn to feel them, and turn them into a positive. It’s energy. It’s unlimited energy!

When he was heartbroken, he says, for instance, he hit the gym harder. Sometimes during this video Tate says things like “rage should be accepted and channeled in a positive direction” and other times he’s says things like “when you are angry you should tell yourself to calm down”, as we’ll see, these are potentially conflicting pieces of advice.

So all the bad things that happen to to you as a man, if you’re Stoic, you get to take unlimited energy, Heartbreak is unlimited energy. So is depression. So is rage. So is sadness. All these negative emotions…

He goes on to give the example that when he’s enraged “it’s like a dam” and you have to control the anger and “put the energy somewhere”, presumably instead of allowing it to be expressed freely.

My Analysis of Tate’s “Stoicism”I have to preface what I’m about to say by repeating that despite the video being titled Stoicism Explained by Andrew Tate, and the interviewer’s opening reference to Marcus Aurelius, it seems uncertain to me whether Tate has actually read the Meditations, or any other books on Stoicism. It’s impossible to know for certain but:

What he says sounds very unlike what Marcus Aurelius says concerning emotions in general and, as we’ll see, I believe Tate’s views conflict with Stoic philosophy

He never quotes any sayings or makes any explicit reference to any concepts or terminology, which might indicate that he’s read the Stoics

His comments about anger are particularly at odds with what Stoicism teaches

I get the impression that in response to a question about the Stoicism of Marcus Aurelius, Tate basically just goes on autopilot and launches into his usual schtick about sports cars, chess, getting frustrated with women, and hitting the gym — he actually says nothing about Stoic philosophy or what it tells us about coping with violent emotions. (And I’m pretty sure Marcus Aurelius didn’t drive a Bugatti.)

Let’s examine the advice Tate does give about emotions, though. To my mind, as a cognitive-behavioral therapist, it appears like he is vacillating between two different, and potentially conflicting, emotional coping strategies: should we “calm the f*** down” when enraged or are we going to have to learn to accept the energy and “turn it into a positive.” Tate runs a self-improvement empire of sorts and has reputedly earned millions by giving advice like this. So I actually expected his answers to sound more consistent, as if he’d thought this over, or at least answered similar questions before.

My honest impression, though, is that Tate sounds like he’s put very little thought into this. Whether you agree with them or not, most self-help experts will tend to give a more coherent account of their favoured coping strategies. Tate gives the sort of response you would be more likely to hear from ordinary people (non experts) who have never been asked for their advice on emotional coping before. There are a couple of different strategies that come to his mind but he doesn’t seem very clear how they’re related. Indeed, suppressing emotions is quite different from redirecting them into activity. You can’t really do both at the same time. He might, for instance, have resolved that conflict by saying that there are certain situations where he thinks emotional suppression is more appropriate and others where redirection is his goal — and he could have explained the criteria for distinguishing one from the other.

None of this bears any resemblance to what Stoics such as Marcus Aurelius believed…

None of this bears any resemblance to what Stoics such as Marcus Aurelius believed, though. Tate views emotion in the naive way most people do by default, as a kind of energy, which builds up inside us — this is sometimes called the “hydraulic” model of emotion. In reality, we know that emotions are composed of multiple factors, though. In particular, the Stoics were known for their emphasis on the cognitive nature of emotion, which became the inspiration for modern cognitive therapy. This research-based model holds that our emotions, including rage, are shaped, more than most people realize, by certain corresponding thoughts and beliefs. This is expressed in the famous quote from Epictetus: “It’s not things that upset us but rather our opinions about them.” Marcus Aurelius says many similar things, paraphrasing this, including applying it specifically to anger.

Tate makes no mention of the role our beliefs play in shaping our emotions. For instance, according to the Stoics, anger is often associated with the belief that someone has acted unjustly and they should be severely punished. Modern cognitive therapy also uses very similar models of anger. We would normally help the client to examine whether these sort of beliefs are rational, healthy, and so on, or if there’s a more accurate, more balanced, or more constructive way of thinking about the situation. For Stoics, and cognitive therapists, therefore, “calming the f*** down” when angry, would reduce the sensation but do nothing to address our underlying angry beliefs. Neither would “hitting the gym” or redirecting anger in other ways.

These strategies can be understood as forms of what psychologists call “experiential avoidance”, trying to temporarily suppress or control an emotion, without actually changing the root cause. For instance, if you believe “women must respect me” and one day (inevitably) a woman rejects you, you will probably feel very angry — your cognition caused your emotion. Telling yourself to calm down might work temporarily but it’s not going to remove the demanding “must” cognition that made you vulnerable to getting enraged in the first place. Likewise, hitting the gym, might distract you from your anger, temporarily, but as long as you still rigidly believe that “women must respect me and if they reject me that is unbearable”, or some other such cognitive recipe for neurosis, you’re just going to become enraged again when they don’t act as you demand. You might as well be trying to hide a ticking time-bomb under a blanket.

Suppression, distraction, and other such avoidant forms of emotional coping are not usually recommended by evidence-based clinicians. In fact, we often begin therapy by evaluating clients’ existing dependance on such strategies and advising them to drop them in favor of alternative ways of coping. That said, I do believe that these strategies can have some benefits. In short, they can work temporarily. For example, although it’s still perhaps not the best way to cope, during a dental procedure, you might handle pain and anxiety by trying to “calm down”, or suppress unpleasant feelings using relaxation techniques. That can work in a pinch, but it will generally become problematic if those sorts of short-term (“experientially avoidant”) emotional coping strategies become your long-term solution. They are basically band-aids, which simply mask emotional problems rather than curing them.

Marcus Aurelius lists ten cognitive strategies for coping with anger, derived from Stoic philosophy…

Of course, you could, in some cases, use relaxation or distraction, to buy yourself time, so that you could work on your angry beliefs later. That’s definitely not what Tate describes doing though. Neither telling yourself to “calm the f*** down” nor hitting the gym harder, by itself, is going to do anything to change your underlying angry beliefs and neurotic demands. Moreover, suppression (calm down) or redirection and venting (hit the gym) are not how Stoicism advises us to handle our emotions. For instance, Marcus Aurelius conveniently lists ten cognitive strategies for coping with anger, derived from Stoic philosophy, in Meditations 11.18. They all involve changing our perspective on the situation, so as to modify the underlying beliefs causing our anger. That’s the real advice Stoics give us. (Along with the very detailed concepts and techniques in Seneca’s full book titled On Anger.) From Marcus’ list of ten Stoic strategies for dealing with anger, though, Tate mentions precisely zero.

So this is not a Stoic approach being described in the video. Nor is it very good psychological advice. Some of Tate’s anger management strategies (“calm the f** down”) are potentially more like lowercase stoicism, the unemotional coping style, than Stoicism, the Greek philosophy. His references to channeling the energy of his rage sound, at times, more like what we call “emotional venting”. This used to be a popular therapy for anger management until around the 1990s. People would go to anger-management workshops held in parking lots or gyms, e.g., where they would thump pillows with baseball bats to “get the anger out of their system”. Several studies showed that this wasn’t an effective therapy, though, and in some cases it has been found to make anger worse.

When you vent or redirect anger you’re not really purging the energy from your body. It’s more like you’re creating a habit through repetition. So, if you’re not careful, you run the risk of making the expression of your anger stronger and more habitual, which often means more automatic and less easy to control. For instance, if “hitting the gym harder” in an attempt to redirect or vent the energy of our emotions really did cure anger then athletes would all be very anger free, including Conor McGregor, John McEnroe, Mike Tyson, et al.

Part of the problem here is that most of us begin with an overly-simplistic view of emotion, as I mentioned above. In addition to recognizing that emotions have a cognitive aspect, it’s also very important to distinguish between voluntary and involuntary aspects of our emotions. This distinction was made by the Stoics over two thousand years ago, providing them with a much more nuanced understanding of emotion than most people have today, including self-improvement influencers like Tate. He seems to vacillate between talking about accepting our emotions and trying to control them. It would be better to say more clearly that we should accept the involuntary aspects of emotion, such as trembling with rage, and take more responsibility or control over the voluntary aspects, such as ruminating about thoughts of revenge, and so on.

ConclusionI’ve left this comment until the end because I think it should make more sense now. If it turns out that the allegations of violence against women are true, and Andrew Tate gets convicted, it’s possible to view poor emotional self-regulation, of his anger or rage, as a contributing factor in his behavior. Certainly, we would expect someone with healthy emotional-coping strategies to be less prone to aggression and violence, and the key to that in most cases is addressing the underlying attitudes which cause intense rage in the first place. It will probably be quite some time, though, before we find out the verdict in this case.

In the meantime, my advice would be that if you’re looking for ways to cope with strong emotions, especially the sort of intense rage described by Tate, you would be better to get advice from a qualified mental health professional, such as a cognitive-behavioral therapist, or at least to read some books providing evidence-based recommendations, rather than turning to influencers such as Tate. They are not basing their advice on scientific research or clinical best practices and, as a result, are often an unreliable source of information on the psychology of emotions, and the best way to cope with toubling feelings.

Likewise, if you’re interested in finding out about Stoicism and Marcus Aurelius, with all due respect, you’re definitely not going to get much of that from Tate’s video above. I would recommend Dr. John Sellar’s book Lessons in Stoicism: What Ancient Philosophers Teach Us About How to Live, as a short and easy to read but philosophically and historically authoritative introduction to the subject.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

As a bonus, here’s a video from The Stoic Teacher, critically evaluating another interview where Tate refers to himself as practising Stoicism.

June 20, 2023

Invite your friends to read Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life — your support allows me to keep doing this work.

If you enjoy Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life, it would mean the world to me if you invited friends to subscribe and read with us. If you refer friends, you will receive benefits that give you special access to Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life.

How to participate

1. Share Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. When you use the referral link below, or the “Share” button on any post, you'll get credit for any new subscribers. Simply send the link in a text, email, or share it on social media with friends.

2. Earn benefits. When more friends use your referral link to subscribe (free or paid), you’ll receive special benefits.

Get a 1 month comp for 3 referrals

Get a 3 month comp for 5 referrals

Get a 6 month comp for 25 referrals

To learn more, check out Substack’s FAQ.

Thank you for helping get the word out about Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life!

Was Marcus Aurelius a Republican?

Ridley Scott’s movie Gladiator (2000), starring Russell Crowe, introduced many people to the figure of Marcus Aurelius, Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher, played in the film by Richard Harris. A few individuals seem to assume it’s meant to be an accurate depiction of events. Most people, though, at least in my experience, realize it’s just a Hollywood “sword and sandals” epic, not a historical documentary, and they take its version of events with a pinch of salt.

I’ve written three books about Marcus Aurelius, and have spent decades studying his life and thought. So I’m very interested in this movie, and the forthcoming sequel, Gladiator 2. It strikes me that some parts of Gladiator that people believe to be totally fictitious, or even absurd, may have been inspired by real events, or at least by the accounts given by ancient historians. In this article, I’ll examine one of the most intriguing examples: the movie’s bold claim that if Marcus Aurelius had lived longer he would have reinstated the Roman Republic.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Marcus the Republican in Gladiator

Marcus the Republican in GladiatorIn the first act of Gladiator, Marcus Aurelius is shown telling his son and heir, Commodus that he has made plans for Rome to revert back to being a republic, ruled by the Senate rather than by an emperor.

MARCUS: Are you ready to do your duty for Rome?

COMMODUS [with a slight smile on his face]: Yes, father.

MARCUS: You will not be Emperor.

COMMODUS [the smile quickly vanishes leaving in its place painful bewilderment]: Which wiser, older man is to take my place?

MARCUS: My powers will pass to Maximus to hold in trust until the Senate is ready to rule once more. Rome is to be a Republic again.

Commodus would have been bypassed in order to appoint Maximus, Russell Crowe’s character, as a transitional ruler, tasked with restoring the Republic. Of course, Commodus takes this news badly. He murders his own father, in order to seize the imperial throne. This is not an accurate portrayal of events. Nevertheless, the historian Cassius Dio does confidently report, albeit based on hearsay, that imperial physicians hastened Marcus’ demise, in order to win favor with Commodus. So, at least in this regard, the depiction in Gladiator differs from but may be loosely based upon one of the accounts we find in the Roman histories.

The biggest historical anomaly in this scene arguably comes from the fact that Commodus had already been Marcus’ co-emperor for three years, ruling alongside his father, before his death. People are usually more taken aback, though, by Marcus’ remarks about Roman politics. They cannot imagine that a Roman emperor, even one such as Marcus Aurelius, could advocate abolishing imperial rule and turning Rome back into a republic. As we’ll see shortly, Marcus does mention some surprising political views in the Meditations. In order to understand them, we need to summarize the history of Roman politics leading up to his time, and its relationship with Stoic philosophy, as that provides the context to which he was referring.

The Historical Context

The Historical ContextI know that many people in America associate the word “republican” with the GOP but we’re using the word here in its original sense. The Romans first introduced the word respublica to refer to the state understood as a “public thing”, as opposed to the possession of a monarch. According to legend, the city of Rome was founded in the 8th century BCE by Romulus, who became its first king after murdering his brother, Remus. It was ruled by successive kings until the last one, Tarquin the Proud, was deposed in the 6th century BCE.

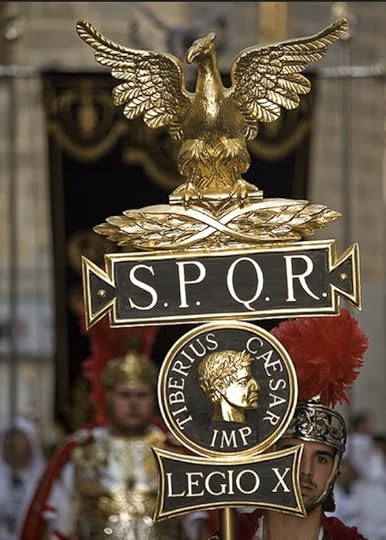

The Roman people replaced him with a senate composed of citizens who governed on their behalf. Each year the senators elected two consuls, or senior magistrates, to lead them. The consuls were granted the power to veto one another’s motions, as a safeguard against the return of one-man rule or autocracy. The state became the property of the Senate and People of Rome or Senatus Populusque Romanus, commonly abbreviated to SPQR. A republic is therefore a state in which supreme power rests with the citizens and their representatives, rather than with an autocrat or monarch.

The Senate and People of Rome, on a legionary standard

The Senate and People of Rome, on a legionary standard The absolute power invested in monarchs, throughout most of antiquity, effectively placed them above the law, whereas their subjects were often forced to comply with whatever laws they imposed on them. Most Romans, particularly the powerful senatorial class, hated the idea of returning to a monarchy. Subjugation to the rule of a king, or political tyrant, was associated with “barbarian” nations, and viewed as a form of slavery. (Romans could reason, paradoxically, that even an enslaved person in their own nation, having some basic legal rights, was more free than the subjects of a “barbarian” kingdom, who could be executed at the ruler’s whim.) Today, in most countries, “republicanism” simply denotes opposition to rule by monarchy. In imperial Rome, it also evoked nostalgia for the old-fashioned values of an era in which supreme power rested in the hands of the Senate.

The fall of the Republic began in 49 BCE when Julius Caesar, a Roman general, crossed the Rubicon river and instigated a civil war against the Senate. Caesar was victorious and appointed himself dictator of Rome. Following later rumors that he wished to go further and be made King of Rome, he was assassinated by Brutus and other republican senators. This triggered another series of civil wars in which Caesar’s assassins were defeated by his two successors, Mark Antony and Octavian. Finally, Octavian defeated the combined navies of Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE. Eighteen years had passed since Caesar crossed the Rubicon. The Roman people were exhausted by the cycle of civil wars and, desperate to avoid any further conflict.

Octavian was an astute statesman and gradually converted the republic into what became known as the principate, governed by him as its “first citizen” or princeps. He progressively claimed more powers until he effectively became the first emperor of Rome, henceforth assuming the title Augustus. He nevertheless insisted that the principate was still a form of republic, although he did rule over it like an autocrat. The Senate begrudgingly accepted this compromise as Augustus had successfully restored stability to the empire after a long period of chaos and civil war.

It meant, though, that his successors would, for centuries, be placed in an ambiguous position. Some Roman emperors ruled more like autocrats or even monarchs, whereas others shared power more with the Senate, and tried to distance themselves from the appearance of monarchy or despotism. Some emperors, such as Nero, for instance, wore extravagant purple robes, decorated with gold, and decked in jewellery, giving them the appearance of wealthy eastern monarchs. Others, such as Antoninus Pius, dressed-down in plain togas, like ordinary senators. Throughout the late Republic and the era of the principate, as we shall see, Stoic philosophers were strongly associated with the defense of traditional Roman values (mos maiorum, the “way of the ancestors”) and republican political ideals.

During the reign of Emperor Nero, the poet Lucan, nephew of the Stoic philosopher Seneca, composed an epic poem about the civil war of Julius Caesar. The hero of his Pharsalia is the Stoic philosopher Cato, an ardent republican, who opposed Caesar every step of the way. Cato’s old-fashioned Roman austerity is implicitly being contrasted with the decadence of the imperial court.

This was the character and this the unswerving creed

of austere Cato: to observe moderation, to hold to the goal,

to follow nature, to devote his life to his country,

to believe that he was born not for himself but for all the world.

In his eyes to conquer hunger was a feast, to ward off winter

with a roof was a mighty palace, and to draw across

his limbs the rough toga in the manner of the Roman citizen of old

was a precious robe, and the greatest value of Venus

was offspring: for Rome he is father and for Rome he is husband,

keeper of justice and guardian of strict morality,

his goodness was for the state; into none of Cato’s acts

did self-centred pleasure creep in and take a share. — Lucan, Pharsalia

…unlike Emperor Nero, for example. When Nero read this, of course, he had Lucan executed, and so the poem was left unfinished.

Republicanism in the MeditationsMarcus Aurelius knew that he was surrounded by powerful figures who did not share his Stoic political values, and even wished him dead. The civil war of 176 CE, in which Avidius Cassius tried to usurp the imperial throne from Marcus and Commodus, proves that a powerful faction of senators and other Roman officials opposed his rule.

There is no man so fortunate that there shall not be by him when he is dying some who are pleased with what is going to happen. Suppose that he was a good and wise man, will there not be at least someone to say to himself, “Let us at last breathe freely, being relieved from this schoolmaster? It is true that he was harsh to none of us, but I perceived that he tacitly condemns us.” This is what is said of a good man. But in your own case how many other things are there for which there are many who wish to get rid of you? You will consider this, then, when you are dying, and you will depart more contentedly by reflecting thus: “I am going away from such a life, in which even my associates in behalf of whom I have striven so much, prayed, and cared, themselves wish me to depart, hoping perchance to get some little advantage by it.” — Meditations, 10.36

Marcus saw himself as engaged in a political struggle against certain powerful Romans who opposed his values, such as Avidius Cassius, and perhaps even his own son, Commodus. What were these ideals that Marcus felt others around him did not share, though?

In order to understand his political vision, we should first acknowledge that Marcus did not believe in revolution. He says clearly in the Meditations that change should come by educating people, and persuading them, rather than by force. This kind of political reform can take decades, or even centuries. Rome was not built in a day, as the modern cliche says, and we should be satisfied with small steps in the right direction. Nevertheless, it is our duty to try to improve both ourselves and the world in which we live.

Set yourself in motion, if it is in your power, and do not look about yourself to see if any one will observe it. Nor yet expect Plato's Republic: but be content if the smallest thing goes on well, and consider such an event to be no small matter. For who can change men's opinions? And without a change of opinions what else is there than the slavery of men who groan while they pretend to obey? — Meditations, 9.29

This passage shows that Marcus wanted to see political changes that were beyond his power, even as the emperor, to achieve overnight. He clearly had a political vision, which he compares to the ideal republic of Plato’s magnum opus. He is probably speaking loosely here and thinking of utopian ideals in general. He was certainly aware of, and had perhaps even read, the Republic of Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, which was a scathing critique of Plato’s work of the same name.

Other political philosophers, however, are mentioned by Marcus, as among his main inspirations.

From my “brother” Severus [I learned] to love my kin, and to love truth, and to love justice; and through him I learned to know Thrasea, Helvidius, Cato, Dio, Brutus… — Meditations, 1.14

Marcus appears to be expressing gratitude to Gnaeus Claudius Severus Arabianus, the father of one of his sons-in-law, whom he refers to affectionately as his brother. The Historia Augusta tells us that Severus was a Peripatetic philosopher, whose lectures Marcus attended. Although known as an Aristotelian, the philosophers mentioned in connection with Severus here are mostly Roman Stoics from previous generations. Marcus presumably meant that Severus had introduced him to their writings.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Let’s consider their names in turn, as these men have something striking in common…

Cato is almost certainly Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis (95 - 46 BCE), known as Cato the Younger, the famous Stoic hero and defender of the Republic, whom we met earlier. Cato opposed Julius Caesar’s attempts to make himself the sole ruler of Rome, but eventually committed suicide rather than being captured during the civil war that ended the Roman Republic.

Brutus is certainly Marcus Junius Brutus (85 - 42 BCE), the lead conspirator in the assassination of Julius Caesar, who was also known among Romans as a philosopher. He was the nephew of Cato the Younger, and later became his son-in-law. Through primarily a Platonist, Brutus was nevertheless a member of Cato’s circle and is generally believed to have been influenced by Stoicism. (Shakespeare, e.g., portrays him as a Stoic philosopher.) For later generations of Romans, Brutus’ name would be synonymous with the philosophical defence of republican political ideals.

Thrasea is certainly Publius Clodius Thrasea Paetus (died 66 CE), the leader of the Stoic Opposition, who criticized autocratic emperors. Thrasea opposed the vicious emperor Nero, in the Senate, protesting against his excesses. As a result, Nero had him executed, which made him a martyr and hero to later generations.

Helvidius is certainly Helvidius Priscus, Thrasea’s son-in-law, who became another martyr after being executed by the tyrannical emperor Vespasian. Epictetus presented him to his students, along with other followers of Thrasea, as a Stoic moral exemplar.

Dio (or Dion) is the trickiest individual here to identify. Some scholars think Marcus meant Dion of Syracuse (408 - 354 BCE), the student of Plato who opposed the tyrant Dionysius II, but he seems quite out of place on this list of Roman philosophers. (Except perhaps that Plutarch compared Dion and Brutus in his Lives.) I believe Marcus is more likely referring to Dio Chrysostom (40- 115 CE), the famous orator and philosopher, who combined Platonism, Cynicism, and Stoicism. He was exiled by the autocratic Emperor Domitian, the son of Vespasian, for allegedly conspiring against his rule.

Thrasea, Helvidius, and Dio Chrysostom had all studied under the famous Stoic Musonius Rufus (c. 20 - 101 CE), who was himself exiled once by Nero and again under Vespasian, and later became the teacher of Epictetus.

In other words, the figures named by Marcus appear to be the two leading Stoic opponents of autocracy during the Republican era (Cato and Brutus), the leading members of the Stoic Opposition (Thrasea and Helvidius), who followed them, and perhaps one of their Stoic-influenced associates (Dio Chrysostom) who opposed the same autocratic emperors. These are predominantly republican thinkers. Cato and Brutus certainly opposed imperial rule. Whereas it’s unclear if the Stoic Opposition all wanted to restore the old Republic, they certainly resisted the office of emperor being turned into political tyranny. For these men, supreme power must rest in the hands of the Senate and people of Rome.

In his recent annotated edition of the Meditations, the classicist Robin Waterfield comments on this passage as follows:

Most of these men were famous, philosophically inspired martyrs to the cause of preserving or restoring the Roman Republic in the face of sole rule or the threat of it […] It says a lot about the changed face of the imperial throne under the “good emperors” that the philosophy of the opposition to the imperial rule in the first century had become the personal philosophy of an emperor. What was Marcus’s interest in these men? Perhaps they were reminders of the opposition he would arouse if, as emperor, he turned autocratic. Perhaps, also, they were reminders that it is possible for politics to be a field where idealism is not misplaced. — Robin Waterfield, Meditations: The Annotated Edition

…the idea of a political state in which there is the same law for all, one administered with regard to equal rights and equal freedom of speech.

Marcus recalls this being one of the key moments in his life. Severus had opened his eyes somehow by introducing him to the works of famous Roman political thinkers from previous generations. In the next sentence, Marcus clearly states that what he took from these conversations was a set of political ideals.

[From Severus] I [also] received the idea of a political state [politeia] in which there is the same law for all, one administered with regard to equal rights and equal freedom of speech, and the idea of a kingly form of government [i.e., a constitutional monarchy] which respects most of all the freedom of the governed. — Meditations, 1.14

The word Marcus uses here, politeia, can be used broadly to refer to any political state, but it tends to carry the connotation of being a republic. How could it be both a republic and a monarchy, though?

Political tyranny was defined by ancient philosophers as a form of absolute monarchy, where the king, or a similar ruler, is above the law, commands supreme power, and rules without any accountability to the people. What Marcus describes here is a political vision in which everyone enjoys equal rights and freedom of speech. For the Romans, that would mean a republic in which the office of Augustus, if it continued to exist, would function more like that of a genuine “first citizen” (princeps), subject to the same law as everyone else. It might be comparable to the concept of what we call today a “constitutional monarchy”, if the emperor depended upon the Senate for his powers, or even a “monarchial republic”, if the office of emperor became largely symbolic or ceremonial. Given that Rome was famously a slave-owning society, it is remarkable to find an emperor telling himself that he envisages a government whose greatest priority is to preserve the freedom of its subjects.

Did Marcus want his general, Pompeianus, to share power with Commodus? Conclusion

Did Marcus want his general, Pompeianus, to share power with Commodus? ConclusionIf this notion of a Roman emperor’s rule seems fanciful or idealistic, nevertheless, we find an echo of it in the Historia Augusta’s account of Marcus’ life:

Toward the people he [Marcus] acted just as one acts in a free state. He was at all times exceedingly reasonable both in restraining men from evil and in urging them to good, generous in rewarding and quick to forgive, thus making bad men good, and good men very good, and he even bore with unruffled temper the insolence of not a few. — Historia Augusta

Marcus saw the emperor, in other words, not as an absolute monarch or political tyrant, but as a servant of the people. We’re told that he always consulted the Senate about key political decisions, including the first major decision of his rule, the appointment of Lucius Verus as his co-emperor. It was also at the behest of the Senate that Commodus was appointed co-emperor. Presumably the Senate must have debated these appointments and voted on them. It is plausible, therefore, that Marcus wanted to institute measures to limit the power of the emperor and place more power in the hands of the senators.

Indeed, the Historia Augusta records that Marcus granted many additional powers to the Senate, even some that formerly belonged to the emperor, adding: “Nor did any of the emperors show more respect to the Senate than he.” The historian Cassius Dio confirms this general picture and adds that Marcus would seek explicit permission for any use he made of public funds.

Marcus also asked the Senate for money from the public treasury, not because such funds were not already at the emperor’s disposal, but because he was wont to declare that all the funds, both these and others, belonged to the Senate and to the people. “As for us,” he said, in addressing the Senate, “we are so far from possessing anything of our own that even the house in which we live is yours.” — Historia Augusta

I don’t think that Marcus wanted to abolish the office of emperor completely, and restore the old Roman Republic, in the way that the movie Gladiator suggests. However, he was clearly influenced by and sympathetic to the writings of philosophers who opposed autocratic rule, including famous republican thinkers such as Cato the Younger and Brutus. Like Thrasea and the Stoic Opposition, Marcus definitely wanted to prevent political tyranny and autocracy, which placed supreme power in the hands of one man without any accountability.

He took steps in this direction by replacing the sole rule of one emperor with the joint rule of two co-emperors, modelled on the way power was shared between two consuls in the Roman Senate. It’s unclear whether he wanted each co-emperor to be able to veto the actions of the other, which would be one way of limiting each individual’s power. However, it does seem that Marcus viewed the role of emperor as requiring him to work hand-in-hand with the Senate, share power with them, and obtain their approval for key decisions and appointments.

It is plausible, therefore, that if his physicians really did hasten Marcus’ death to please Commodus, they may have prevented him from announcing additional changes to the office of emperor, which would have prevented his son from becoming such an autocrat and tyrant. Perhaps Marcus would have expressed his wish, based on the advice of Severus, and the works of philosophers such as Cato, Brutus, Thrasea, et al., that Rome should become an imperial republic “which respects most of all the freedom of the governed”, by ceding further powers to the Senate.

Commodus equated himself with the god Hercules

Commodus equated himself with the god HerculesSo although Gladiator is hardly intended to resemble a historical documentary, in some instances it is not as far removed from the evidence as many people assume. I doubt Marcus would have announced, as he does in the movie, Rome is to be a Republic again! However, based on what he wrote in the Meditations, his final words could more plausibly have been depicted in the movie as: Rome is to have the same law for all! In accord with his philosophy of gradual political change, this would require progressively handing over greater powers to the Senate until the emperor was effectively sharing power with them, ruling with their approval, and subject to the law, like an ordinary citizen.

In reality, though, following Marcus’ death, Commodus reversed much of what his father had done. He wielded supreme power as sole emperor, operating above the law, without regard for the Senate. Commodus eventually began dressing in extravagant silk robes and expensive jewels, declared himself a god, and became Rome’s tyrant. How this was allowed to happen is another story but I believe that it has to do with the Senate’s fear of an even greater threat: the fragmentation of the Roman Empire through civil war.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

June 7, 2023

Ask me anything about Marcus Aurelius

I’m answering questions about Marcus Aurelius on Substack Notes today, as a way of testing out the new feature. You’re welcome to join the discussion and post any comments or questions you like in response to the Note below.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.