Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 27

August 29, 2023

How to Walk Like a Stoic

All truly great thoughts are conceived by walking. — Nietzsche

[Note: I wrote this article in 2019. My friend, “Scottish Thomas” (Thomas Douglas) passed away two years later in 2021.]

A few years ago, one of my friends, “Scottish” Thomas, was nearly beaten to death by four youths who tried to mug him at the Halifax Waterfront, in Nova Scotia. He told them to “Get lost!” (or words to that effect) and clung on to his knapsack, although there was nothing in it but some dirty laundry.

They crowded round him and stamped his face into the ground, fracturing his jaw in several places. Thomas had reconstructive surgery, requiring several operations. He never fully recovered his physical health. Years later, I read a news story about the attack and was shocked to see a photograph showing the blood stains left behind on the boardwalk — my friend’s blood. After he’d been discharged from hospital Tommy got into the habit of walking around town for hours more or less every day, even during the frigid winters, passing by the spot where he was attacked. He told me that he found it therapeutic: both physically and mentally. Sometimes, I’d go with him and keep him company.

My friend, Thomas Douglas, passed away in 2021.

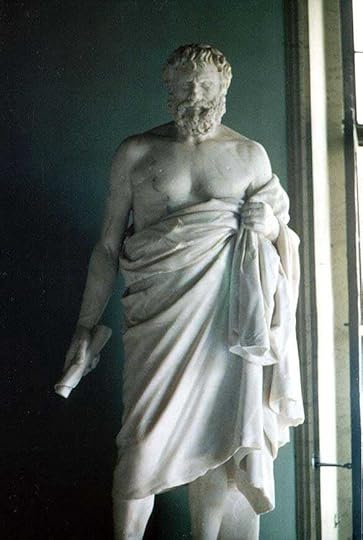

My friend, Thomas Douglas, passed away in 2021.We used to talk and joke, sometimes about Socrates and the Stoics, and it made me think about the role of walking in ancient Greek and Roman philosophy. (At the time, I was working on my book about Stoicism: How to Think Like a Roman Emperor.) Tommy reminded me of the Cynic, Diogenes of Sinope, albeit perhaps a softer, friendlier version. Diogenes was a “wanderer without a home” and a citizen of the whole world. He walked around Athens barefoot and naked except for a grubby woollen cloak and a small knapsack containing some basic food: some cheap bread, and a few lupin beans.

Diogenes taught that genuine freedom comes from within — from self-sufficiency rather than from wealth, power, or reputation.

Diogenes taught that genuine freedom comes from within — from self-sufficiency rather than from wealth, power, or reputation. Not from having as much as possible, in other words, but from needing as little as possible. The most famous story about Diogenes the Cynic was that when Alexander the Great, paid him a visit and asked if he could do anything for him, Diogenes replied: “Yes, step aside, you’re blocking the sunlight.” (Alexander was sometimes portrayed as the child of the solar god, Apollo.) As he was walking away, with his retinue chattering in puzzlement, the Macedonian king reputedly said: “Truly, if I were not Alexander, I would wish to be Diogenes.”

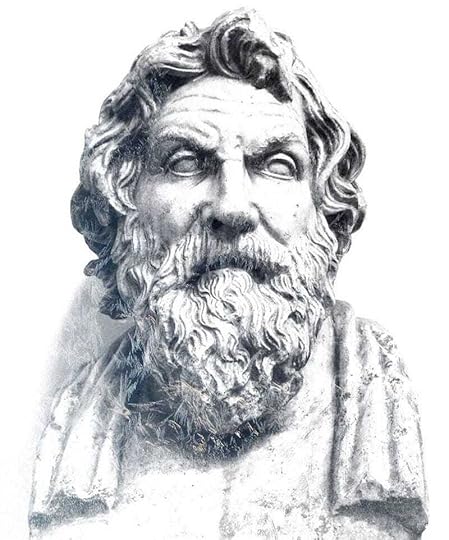

Before emigrating to Canada, I was a cognitive-behavioural therapist in London, UK. I had published several books about my special interest: Stoic philosophy and modern psychotherapy. Diogenes is traditionally seen as part of a philosophical lineage spanning over half a millennium. It begins with Socrates, extends through his follower Antisthenes, via Diogenes and the Cynics, down to Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoic philosophy, and his many followers. I became interested in the Stoics because their writings constituted the original philosophical inspiration for modern cognitive-behavioural therapy. It struck me one day that a curious philosophical interest in the activity of walking permeates this Cynic-Stoic wing of the Socratic tradition.

Socrates himself was known for walking barefoot. His student Antisthenes, who inspired the Cynics and Stoics, likewise walked barefoot for miles to listen to him talk each day. It’s said they were both good friends with a shoemaker called Simon. (They discussed philosophy with Simon but weren’t giving him much business!) Among Socrates’ many followers, Antisthenes particularly espoused philosophy as a way of life, by embracing poverty and simplicity, and cultivating self-discipline and endurance. Socrates and Antisthenes were pioneers, in a sense, of the distinctive Cynic lifestyle made famous a generation later by Diogenes, who sought to return to nature through plain living, despite being in an urban setting.

Diogenes used to say that both mental and physical training are required to become a true philosopher. Constant physical exercise that is in accord with nature, leads to a fulfilled life. However, he reputedly also said that “no exercise is of any value unless it aims at the good order and fitness of the soul, as opposed to that of the body.” Later in his life, Diogenes was captured by pirates and sold into slavery. He was purchased by a wealthy man who entrusted him with the education of his sons. The Cynic taught the young men in his care to “go out dressed in nothing but a cloak, with no shoes on their feet; as they walked they had to keep silent, and not look around them in the street.”

The philosophy of Diogenes inspired various moral, spiritual, and psychological exercises that involved walking. He would walk into the theatre against the flow of people leaving, and walked around backwards in public arcades. Other Cynics walked around carrying fish, cheese, or bowls of lentil soup, down bustling streets, where they would be jostled by the crowds. This symbolised their desire to radically swim against the tide of popular opinion but it also served an important psychological function. Modern cognitive therapists treat social anxiety by prescribing “shame-attacking” exercises. Diogenes once tied a piece of string around the neck of a ceramic wine bottle and took it for a walk through the potter’s district. Today it’s a banana on a string. The idea is to do something embarrassing so often that, eventually, you completely extinguish your sense of shame.

Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, seems to have been socially nervous or shy until his mentor Crates instructed him to walk through the crowded streets carrying a bowl of lentil soup. When Zeno tried to hide the bowl under his cloak, Crates smashed it with his staff, leaving his student to walk around with lentil soup dribbling down his bare legs until he finally got over his embarrassment. It must have worked because about two decades later we’re told that Zeno was consulted by King Antigonus of Macedonia, one of the most powerful military and political leaders of the time. Although Zeno dressed like a beggar, Antigonus found himself looking to him as an equal, or even a superior, because of his wisdom, composure, and self-confidence — much as Alexander the Great had reputedly looked upon Diogenes the Cynic.

Like their Cynic predecessors, the Stoics had an interesting attitude toward walking. Zeno was renowned for lecturing on philosophy while walking briskly up and down the Stoa Poikile or “Painted Porch” where he started his school. (We’re told that prevented lazy students from slouching on the floor!) He disliked being among a crowd of people, such as at a drinking party or dinner, and preferred to spend his evenings either walking alone or with no more than two or three companions. His successor as head of the Stoic school, Cleanthes, walked around all night watering gardens to make a living. Chrysippus, the third head of the Stoic school, was a long-distance runner. He warned his students that when they’re consumed by passionate desires and emotions they resemble someone running too quickly to avoid obstacles in their path. The wise man resembles someone walking (or running) slowly enough to be able to stop or change direction whenever he chooses to do so — he’s still in control of his own actions.

Later Stoics also seem to have associated philosophy with walking calmly, in a self-possessed fashion. Cato of Utica, the great Stoic hero of the Roman Civil War, attracted attention because, unusually for a military officer, he generally avoided riding a horse and walked everywhere. Plutarch implies this was part of training himself in “shamelessness” (like a Cynic) as well as a means of developing physical endurance. Seneca, another Roman Stoic, likewise recommends walking in the fresh air as an exercise for Stoics. “We should take wandering outdoor walks,” he says, “so that the mind might be nourished and refreshed by the open air and deep breathing.”

However, Seneca also frequently says you can judge a man’s character by the way he walks. The ancient philosophers believed that walking barefoot encouraged circumspection. Epictetus says, for instance, that someone walking barefoot must obviously be careful where he treads, in case he steps on a nail or hurts his foot. He tells his students that, in the same way, they should be cautious not to harm their own character through the value-judgements they make, which Stoics believe to be the root cause of our unhealthy fears and cravings. To walk with wisdom is to walk with self-awareness, mindful of how we are using both our body and our mind, from moment to moment. It’s our ruling faculty, our faculty of judgement, that we have to watch like a hawk.

“Man, if you are anything, both walk alone and talk to yourself, and do not hide yourself in the chorus.”

Indeed, Epictetus tells his students about a highly-regarded Stoic philosopher called Euphrates of Tyre who spent years secretly living as a philosopher, patiently training himself to eat with moderation and to walk around with mindfulness and in a self-possessed manner. Epictetus asks his students: “Do you read when you are walking?” No, he says. If they want to become true philosophers, like Euphrates, they should walk alone and silently converse with themselves.

They should walk in order to contemplate the deepest questions in life, without paying too much attention to other people’s opinions or what’s written in books: “Man, if you are anything, both walk alone and talk to yourself, and do not hide yourself in the chorus.” Get into the habit of examining your own mind and the world around you while walking in deep philosophical contemplation, Epictetus says, so that you may come to know who you really are, rather than losing yourself in society, among the chatter of other people’s voices.

Antisthenes

Antisthenes

August 24, 2023

Stoicism and Buddhism

In this episode, I speak about Stoicism and Buddhism with Matthew Gindin. Matthew is a former Forest Monk in the Thai Buddhist tradition. He taught meditation practices for 15 years, and has written extensively for Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. He is now the author of the newsletter on Substack.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

HighlightsHow Matthew became interested in Stoicism and his other philosophical influences, such as Spinoza

The rise in popularity of Stoicism, e.g., how it appeals to people interested in Buddhism, etc.

What do you think Stoicism and Buddhism have in common?

The historical relationship between Stoicism and Buddhism, e.g., communication between ancient eastern and western philosophers

How Stoics could benefit from learning more about Buddhism

LinksSubstack Newsletter

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 22, 2023

Video: Stoicism and Cognitive Distancing

Here’s the video of the talk I gave recently about Stoicism and Cognitive Distancing for the Conversations with Modern Stoicism event.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 17, 2023

Design your Mind with Stoicism

In this episode, I talk to Ryan A. Bush, author of Designing the Mind: The Principles of Psychitecture and the forthcoming Become Who You Are: A New Theory of Self-Esteem, Human Greatness, and the Opposite of Depression. Bonus: Ryan is generously offering listeners two free ebooks from his website, called the Psychitect’s Toolkit and The Book of Self Mastery.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

HighlightsWhat is Designing the Mind and Psychitecture?

How Ryan’s background in design influenced his approach to self-improvement

The main thing Ryan thinks people should learn to stop doing

The philosophical influences on Ryan’s work

How Ryan became interested in Stoicism

How Ryan’s work draws on cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT)

The role of metacognition and meditation

Ryan’s views about anger

How his new book, Become Who You Are, differs from his previous book

LinksDesign the Mind: The Principles of Psychitecture

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 15, 2023

Stoicism and Persia

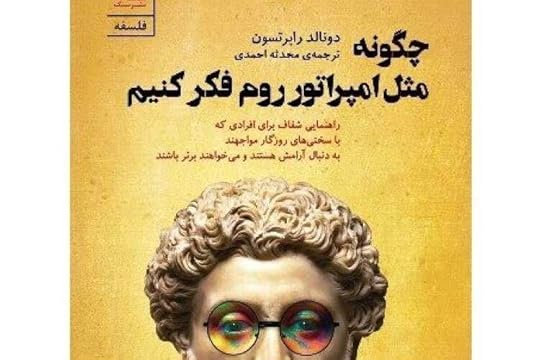

Recently I was asked to contribute the foreword for a Persian edition of my book Stoicism and the Art of Happiness, translated by Morteza Barati. The original English edition was published as part of Hodder’s popular Teach Yourself series in 2013, and a 2nd revised edition was published in 2018. My subsequent book on Stoicism, How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius (2019), was translated into Persian by Sang Publishing in 2020.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Stoicism and PersiaThe Stoics were greatly influenced by Socrates and some of the philosophers who followed him. Socrates, and two of his friends Xenophon and Antisthenes, all expressed admiration for Cyrus II, who founded the Persian Empire in 550 BCE. (Socrates in Plato’s First Alcibiades, Xenophon in his Cyropaedia, and Antisthenes in the Cyrus, and other lost works.) The Socratics of the 4th century BCE looked back upon Cyrus as an exemplar of the wise and just ruler. We know that some of the Stoics inherited this perspective from them. The last head of the Stoic school, Panaetius, for example, held Cyrus in high regard, as did his student, the great Roman statesman Scipio Africanus, who constantly quoted from Xenophon’s Cyropaedia. Cicero and, later, Dio Chrysostom, also seem to have held Cyrus in high regard as a role model.

After Alexander the Great defeated the Persian king Darius III, in 331 BCE, the Achaemenid Empire founded by Cyrus fell to a series of Greek rulers, who formed the Seleucid Empire. The Stoic school was founded a few decades later, around 301 BCE, by Zeno, a Phoenician merchant from Citium in Cyprus, after he was shipwrecked near Athens. Most of the subsequent leaders of the early Stoic school were also immigrants to Athens, many of them coming from within the Seleucid Empire. They came from Tarsus, the ancient centre of learning in Asia Minor, but also from as far east as Babylon and Seleucia, on the banks of the Euphrates and Tigris respectively, where Hellenistic and ancient Iranian cultures mingled.

As the Parthian Empire of the Arsacids gradually succeeded the Seleucid Empire in the east, though, the centre of learning for Stoic philosophy moved westward from Athens to Rome. Some traces of the early Socratic respect for the great founder of the Persian empire endured. Epictetus, the most influential Roman Stoic teacher, and Marcus Aurelius, the last famous Stoic of antiquity, both quote a passage seemingly from one of Antisthenes’ works dedicated to the Great King of Persia (Discourses, 4.6.20; Mediations, 7.36).

It is a royal thing, O Cyrus, to do good and yet to be spoken of badly.

In other words, it shows true leadership and strength of character for an individual to persist in doing what they believe to be right, even in the face of criticism.

We think that there is nothing worse than death, though death is not bad; fearing death is bad.

We’re told that when the emperor Marcus Aurelius visited the eastern provinces of the Roman empire, around 175 CE, travelling through Cappadocia, Cilicia, and Syria, he met with emissaries from ancient Iranian kingdoms, and renewed interest in Stoic philosophy among eastern intellectuals.

He conducted many negotiations with kings, and ratified peace with all the kings and satraps of Persia when they came to meet him. He was exceedingly beloved by all the eastern provinces, and on many, indeed, he left the imprint of philosophy. (Historia Augusta, Marcus Aurelius, 26.1)

Centuries later, during the era of the Graeco-Arabic translation movement, many western philosophical texts were translated by Arab scholars, including some Greek Stoic texts. Indeed, we can find examples of Stoic philosophy in the writings of Arab Muslim scholars, such as Al-Kindi’s Device for Dispelling Sorrows, written in the 9th century CE. Al Kindi attributes such pieces of wisdom to Socrates, though the Stoic notes in this text are clear.

It is related about the Athenian Socrates that it was said to him: ‘Why is it that you are not sorrowful?’ He responded: ‘Because I do not possess anything for the loss of which I will be sorrowful.’ (Al-Kindi, Device for Dispelling Sorrows)

At times, he sounds even more Stoic, such as in his saying “We think that there is nothing worse than death, though death is not bad; fearing death is bad.”

The Arab philosopher al-Farabi (Alpharabius) drew upon Stoic logic, and apparently wrote a lost text titled Interpretation of the Great Zeno’s Book, in reference to the founder of Stoicism. Later, in the 11th century CE, the Persian philosopher, Ibn Sina, known in the west as Avicenna, is believed also to have studied Stoic logic, and to have been influenced by Galen, the court physician of Marcus Aurelius, who drew, albeit critically at times, upon Stoic theories of psychopathology and psychotherapy in his writings.

In the 12th century, there may even have been a fully-fledged Stoic movement within Islamic scholarship, started by the Persian philosopher Suhrawardi, the “Master of Illumination”, and his followers. Although, Suhrawardi appears to have been mainly influenced by Plato and the Neoplatonists, in the 17th century, the Persian philosopher, Sadr al-Mutalahin Shirazi, better known as Mulla Sadra, critically responded to what he described as a “Stoic” tradition, which he identifies with Suhrawardi and his followers, referred to approximately 200 times in his surviving writings.

The Socratic-Stoic tradition in the west took early inspiration from the founder of the Persian Empire, as we’ve seen, and Stoic principles, derived from the Graeco-Arabic translation movement, have been among the philosophical influences shaping the thought of Arab and later Persian scholars. It is my hope that this Persian translation of my work, drawing on a range of surviving Greek and Latin Stoic texts, may help in some small way to encourage both the modern application of Stoic philosophy and study of its relationship with the wisdom and values found in ancient Persian history and the writings of Islamic scholars.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 10, 2023

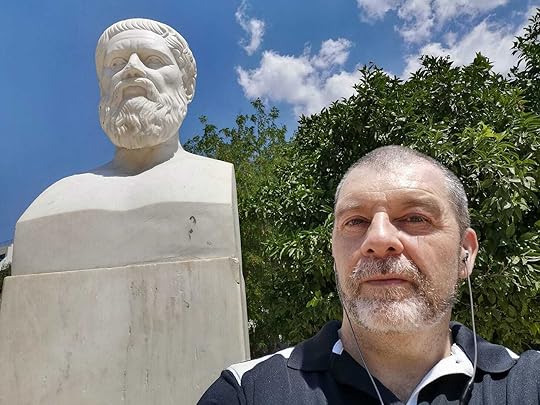

What is the Plato's Academy Centre?

A few years ago, I was walking in the Akadimia Platonos park in Athens wondering: Why on Earth isn’t there an international conference centre at the original location of Plato’s Academy? Today, our nonprofit, (PAC), is in its second year and growing rapidly, thanks in part to our stellar directors and Board of Advisors.

Phase One of our vision is to build a thriving intellectual online community where people can access classical wisdom with the help of leading academics and bestselling authors.

Phase Two is to run regular in-person events in Athens, and ultimately to acquire property there, to help urban renewal in the suburb where Plato’s Academy is located.

Who would have thought we’d have made this much progress so quickly? Today, I’m pleased to be able to reward all of my own loyal Substack subscribers with a special free trial offer when you sign up now for our Plato’s Academy Centre newsletter on Substack. (NB: This offer is time-limited, so don’t miss out!) See our platosacademy.org website for more information on the nonprofit and its goal of bringing philosophy back to the original location of Plato’s Academy. We can’t do this without your support!

Donald taking photos of the ruins in Plato’s Academy Park

Donald taking photos of the ruins in Plato’s Academy ParkWe launched the newsletter on Substack recently, where Kasey, my wife, and our communication’s director, has been regularly publishing a program of high-quality original content, including:

Interviews with classics authors and academics

Select audio of talks from our virtual events on philosophy,

Interviews with experts on philosophy and classics via the PAC Philosophy and Classics podcast

Exclusive excerpts from recent/forthcoming books on classics and philosophy in Plato’s Library

By becoming a free subscriber to the Plato’s Academy Centre newsletter you help us to build our community and reach a wider audience. That helps us to expand our network of authors and academics, and build more support from other stakeholders in Greece and around the world. By becoming a paying subscriber or even a Founding member of the you help us cover the operating costs involved in organizing free events and spreading the word about Greek philosophy.

Donald Robertson, Justin Stead, Kostas Bakoyannis, Pat Cash, and Michalis Michael, at Plato’s Academy Park

Donald Robertson, Justin Stead, Kostas Bakoyannis, Pat Cash, and Michalis Michael, at Plato’s Academy ParkLast September, we were proud to support the Aurelius Foundation and YPO in running a first-of-its-kind open-air philosophy event in Plato’s Academy Park, in a marquee among the ruins. The Mayor of Athens, Kostas Bakoyannis, was our guest of honour, and we were also grateful for support from the Minister for Development and Investment, the Minister of Culture and the US Ambassador to Greece. We’re helping to run an even bigger and better event next Spring, building on our success.

Nearly three thousand people have attended our virtual events so far, and we’re on course to have over a thousand attendees at our forthcoming On Seneca: Anger, Fear and Sadness event on 19th August — you’re welcome to join us!

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Thanks for your support! If you want to refer friends to The Plato’s Academy Centre newsletter please feel free to do so, using the special trial offer link below:

https://platosacademycentre.substack....

Yours faithfully,

Donald Robertson

President of The Plato’s Academy Centre

August 8, 2023

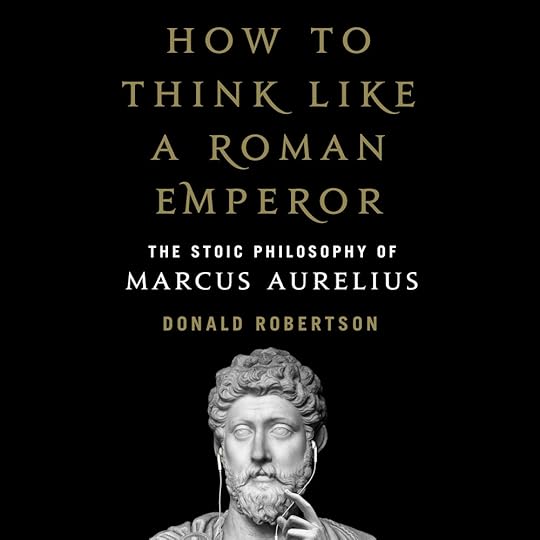

Audiobook: How to Think Like a Roman Emperor

I recently finished writing a prose biography called Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor, due to be published by Yale University Press as part of their Ancient Lives series in January 2024. I’ll be sharing more info about Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor soon. I’m pleased to announce, though, that I will be narrating the audiobook version of this new book.

Some early praise for Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor:

Robertson has written a very thorough and very readable account of Marcus’s life and the events and people that shaped him. Anyone who wants to understand the author of Meditations should read this book.—Robin Waterfield, author of Marcus Aurelius, Meditations: The Annotated Edition

Robertson’s biography provides a compelling narrative of Marcus’ life, carefully based on the primary sources. He brings out very clearly the life-long significance of Stoicism for Marcus and the interplay between philosophy, politics, and warfare.—Christopher Gill, author of Learning to Live Naturally: Stoic Ethics and its Modern Significance

You can actually preorder it already from Amazon and some other booksellers.

Some of the existing titles in the Ancient Lives series

Some of the existing titles in the Ancient Lives seriesThe audiobook of How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, has sold over 60k units, and the book, across all formats and translations, is now approaching sales of a quarter of a million!

In March, it was featured on the Audible Blog list of The Best Philosophy Audiobooks, which says:

How to Think Like a Roman Emperor weaves together three threads—biographical content on Marcus Aurelius, summaries of his Stoic philosophy from his famous The Meditations, and information about cognitive behavioral therapy approaches that complement the practice of Stoicism—to craft a compelling listen. Psychotherapist Donald Robertson narrates his own work, and his even, understated delivery makes this intensive look at philosophy, psychology, and history engaging and easy to follow. The figure of Marcus Aurelius looms large in history, and Robertson does his life and work justice with this comprehensive introduction. Neither losing the listener in the halls of history nor forcing tenets of Stoicism to fit contemporary times, the author manages to make the wisdom of Marcus Aurelius immediate and personal.

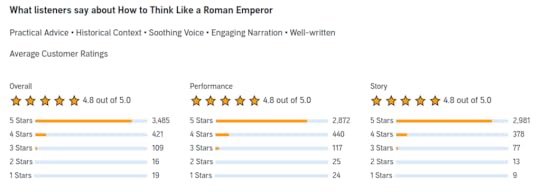

The English audiobook of How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, has now been rated/reviewed by over four thousand listeners on Audible.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

It is also available in Spanish, and hopefully audiobooks in other languages will be available in the future, as the print copy has already been translated into at least eighteen languages.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 3, 2023

It is not things that disturb us. . .

CommentIt is not the things themselves that disturb men, but their judgements about these things. For example, death is nothing dreadful, or else Socrates too would have thought so, but the judgement that death is dreadful, this is the dreadful thing. When, therefore, we are hindered, or disturbed, or grieved, let us never blame anyone but ourselves, that means, our own judgements. It is the part of an uneducated person to blame others where he himself fares ill; to blame himself is the part of one whose education has begun; to blame neither another nor his own self is the part of one whose education is already complete.

The opening sentence of this passage is almost certainly the most famous quotation from Epictetus. It was taught to therapy clients by Albert Ellis, the founder of Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy (REBT) and became a common part of the “socialization” (orientation) process in subsequent cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT). Clients might just be told about it but it was, and still is, often included on handouts given to them at the start of therapy.

The truths of Stoicism were perhaps best set forth by Epictetus, who in the first century A.D. wrote in the Enchiridion: ‘Men are disturbed not by things, but by the views which they take of them.’ – Albert Ellis

This isn’t really the most fundamental teaching of Epictetus. That’s probably the opening sentence of the first passage, which as we saw earlier deals with the distinction between what is up to us and what is not. However, it’s perhaps a close second, as variations of this teaching recur frequently throughout the Discourses of Epictetus.

August 1, 2023

Join me for a Conversations about Modern Stoicism

I’ve been invited to give a short presentation for Conversations with Modern Stoicism. This is an interactive online event designed to bring the community together to talk with each other about Stoicism. Everyone is welcome; free of charge.

I’ll be talking about how Stoic practices can be combined with modern self-help and cognitive therapy, and the pros and cons of using different psychological techniques.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Saturday, August 12th, 10-11.30am EDT

There will be a short introduction and presentation, followed by a Q&A session. Then everyone will break out into groups for structured discussions.

Audience members will be encouraged to have cameras on and be ready to communicate with each other via video and with audio.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

July 28, 2023

Time is Running out to Join How to Live Like Socrates!

Tempus breve est.

Time is short.

I just wanted to send a quick reminder that enrolment for How to Live Like Socrates will be closing tomorrow, so don't miss your chance to take part.

If you haven't already joined the course, here's why you should consider giving it a go...

Discount. You'll be receiving a special discount as a newsletter subscriber. I've taken $50 off the price for the standard course, including webinars.

Payment Plan. I've added a , so it's now possible to split payments across three monthly instalments!

Improvements. You'll have ongoing access to the course as long as it's available, including any future additions or improvements you might suggest.

Bonus Resources. I've bundled in 3 online resources for you: The Life and Opinions of Socrates, Socrates HD Wallpapers, and Crash Course on Socrates

Interact and Learn with Others. Get the chance to interact with and learn from other participants as well as take part in weekly webinars. On my last course the students shared nearly five hundred comments discussing the content.

Learn from an Expert. You'll be taking a course run by someone who's published four books on Greek philosophy, plus another three chapters in edited collections of articles on the subject.

If now’s not the right time for you then no problem, you’ll still be able to join when it opens again next time - I usually open it once or twice a year. If you’re just not sure if the course is for you, then don’t forget I offer a risk free 30-day money-back satisfaction guarantee. Hope to have you join me!

Warm regards,

Donald Robertson

PS. If you haven't already, check out the sneak peek at my video!