Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 24

December 5, 2023

How Phoenician was Stoicism?

"You slip in, Zeno, by the garden door — I'm quite aware of it — you filch my doctrines and give them a Phoenician make-up."

This intriguing remark was reportedly made by Polemo of Athens, the head of the Platonic Academy. He is accusing Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, of pinching ideas from his philosophy. Stoicism was perceived by some Greeks as having originally borrowed certain doctrines from Platonism, a native Athenian philosophy, and dressed them up in a more Phoenician style. We’re left, though, to puzzle over precisely what this meant.

It’s often said that Stoicism was a school of ancient Greek philosophy but this isn’t entirely accurate.

It’s often said that Stoicism was a school of ancient Greek philosophy but this isn’t entirely accurate. It was “Greek” to the extent that it was founded at Athens, and taught, as far as we know, exclusively, in the Greek language. (At least until Cicero began to translate Stoic philosophy into Latin, two and a half centuries later.) However, most of its early luminaries, came to Athens from several regions of West Asia (Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, and the Levant). Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, is repeatedly described not as Greek but as Phoenician. Athenians, of that period, indeed, saw the philosophy as somewhat foreign.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Zeno, the son of Mnaseas (or Demeas), was a native of Citium in Cyprus, a Greek city which had received Phoenician settlers. — Diogenes Laertius

As we’ll see, other references make it clear that Zeno was related to these Phoenician settlers rather than to the original Greek colonists. After being conquered by Alexander the Great, in 333 BCE, around the time when Zeno was born, Cyprus was progressively Hellenized. (The term we use to refer to a foreign nation embracing Greek language and culture.) Nevertheless, Cyprus still retained ties to Phoenician culture:

Citium in Cyprus, the native place of Zeno, had a population which was largely Phoenician in blood. It was ruled by a dynasty of Phoenician petty kings, whose names figure in the Punic inscriptions found on the spot From 361 to 312 B.C., within which period the first twenty years of Zeno's life probably fall, its king was Pumi-yathon the son of Milk-yathon the son of Baal-ram. — Edwyn Bevan, Stoics and Sceptics

The evidence of inscriptions therefore suggests that a Phoenician royal dynasty continued to rule Citium throughout Zeno’s youth, until around the time he left and ended up in Athens.

What of his father’s name, mentioned in the quote above? Jacques Brunschwig, a professor of Ancient Philosophy at the Sorbonne, writes in a recent study of Zeno’s origins:

It is generally agreed that Mnaseas is a hellenized version of Semitic names like Manasse or Menahem. If that is true, the conclusion to draw would be, of course, that Zeno’s father was a Phoenician; but also, and much more importantly in my opinion, that he was already a hellenized Phoenician.

Zeno’s own name, as Brunschwig notes, is thoroughly Greek. Rather appropriately for the founder of Stoicism, it means “[born] of Zeus”. Mnaseas, his father, was perhaps born into a family who identified more with their Phoenician heritage, and lived to see the Hellenization of Cyprus. Zeno, his son, was probably born into a culture at Citium, which was already becoming Hellenized, despite still being governed by Phoenician nobles. Diogenes Laertius makes a point of describing him as melanchrous, however, which means black-skinned or swarthy. The point he’s trying to make seems to have been that Zeno was somewhat darker in appearance than a typical Athenian. Basically, to most Greeks, he looked a bit foreign.

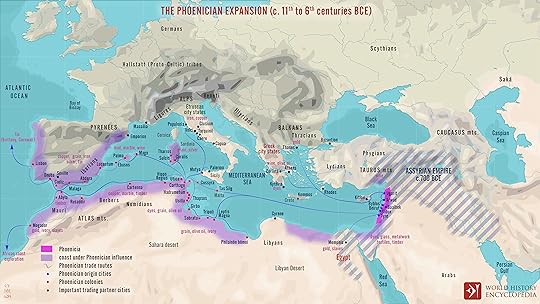

Who were the Phoenicians?The Phoenicians, in the eyes of Athenians, were a seafaring race of barbarians. (The derogatory term barbaroi literally meant people who sound like they are saying bar bar or blah blah, i.e., who speak a foreign tongue.) Crucially, that is, they were not Greek. They are now believed to have been a Semitic people, possibly related to the Canaanites, who originated in the Levant region of West Asia. Some scholars have questioned whether the Phoenicians actually existed as a distinct civilization. It may just have been a term used by the Greeks to lump together various seafaring semitic peoples who shared a common language. Nevertheless, in the eyes of Greeks, the Phoenicians constituted an ancient barbarian nation, which had been conquered and was ruled by Persia.

As far as we know, Phoenicia never had a centralized government but was always a loose federation of largely autonomous city-states. In this regard, it was not unlike ancient Greece. Tyre and Sidon were the two most prominent Phoenician cities — both located in modern-day Lebanon. As result of their success as seafaring merchants, the Phoenicians spread throughout the Mediterranean, settling along the north coast of Africa as far west as Spain. They are even believed to have traded with the ancient Britons. They were renowned as master shipbuilders and Phoenician had one of the earliest written alphabets. According to Greek legend, the Phoenician hero Cadmus, prince of Tyre, founded Thebes. The historian, Herodotus, claimed that Cadmus introduced the Phoenician alphabet to Greece, which led to the evolution of written Greek.

Reproduced under Creative Commons license courtesy of worldhistory.org

Reproduced under Creative Commons license courtesy of worldhistory.orgPhoenicia therefore once constituted a powerful thalassocracy, or maritime empire. They were traditionally allied with, and provided ships for, Persia, the most powerful “barbarian” enemy of Greece. In Zeno’s time, following the conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great, however, the heartland of Phoenicia, in the Levant, became part of the Hellenistic successor state known as the Seleucid Empire. Cyprus became part of the Ptolemaic Empire, a rival Hellenistic successor state, governed from the city of Alexandria, in Egypt.

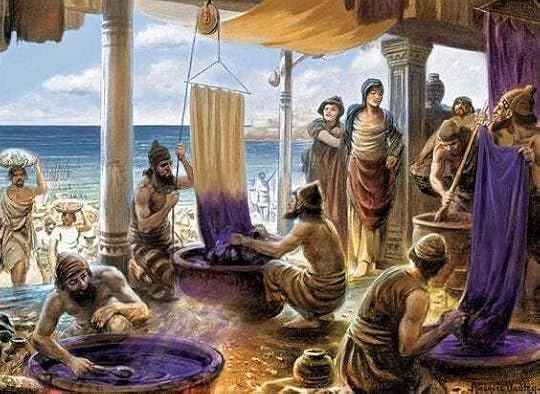

The Phoenician civilization was built upon maritime trade and they were particularly known for manufacturing and trading the most precious dye of the ancient world, known as Tyrian purple. Indeed, the name Phoenicia, given to them by the Greeks, appears to be related to the word phoinix (“purple”) and perhaps meant “the purple people”. (We do not know what these people actually called themselves.) Slaves painstakingly extracted a tiny quantity at a time from the innards of fermented murex sea snails. It was one of the most unpleasant jobs in the ancient world but the resulting dye could be worth its own weight in silver.

Zeno himself was a seafaring dye merchant, who probably travelled between Cyprus, the Levant, and various Greek cities, including Piraeus, the port of Athens.

He [Zeno] was shipwrecked on a voyage from Phoenicia to Piraeus with a cargo of purple. — Diogenes Laertius

After being shipwrecked near Athens, Zeno settled there, living as a metic or foreign resident, which meant he had limited rights compared to an Athenian citizen. For instance, he was most likely prohibited from owning property within the city of Athens. (He may have lodged with friends.)

Another anecdote, attributed to the contemporary writer, Antigonus of Carystus, seems intended to highlight that Zeno could potentially have passed for a Greek, despite his dark complexion, as he had been brought up to be familiar with the language and culture. He earned respect for continuing to be transparent about his Cypriote birthplace.

[…] he never denied that he was a citizen of Citium. For when he was one of those who contributed to the restoration of the baths and his name was inscribed upon the pillar as "Zeno the philosopher," he requested that the words "of Citium" should be added. — Diogenes Laertius

He was clearly proud of being a Cypriote but this story implies that it was something he might have been tempted to conceal. He probably risked being looked down upon as a “barbarian” because of his Phoenician ancestry.

After his death, decades later, he was highly-honored in Athens. A statue of him was erected in Citium, and his legacy was also celebrated by the Phoenician community in Sidon.

The people of Athens held Zeno in high honour, as is proved by their depositing with him the keys of the city walls, and their honouring him with a golden crown and a bronze statue. This last mark of respect was also shown to him by citizens of his native town, who deemed his statue an ornament to their city, and the men of Citium living in Sidon were also proud to claim him for their own.

This final remark is ambiguous but may refer to Phoenicians who had migrated from Citium to Sidon and viewed Zeno as part of their community. Perhaps Zeno’s family were originally from Sidon, and he still maintained a connection with relatives there. It is likely that, as a seafaring merchant, Zeno would have sailed between his home city of Citium, in Cyprus, and the major Phoenician city of Sidon, in the Levant. In any case, Zeno’s kinship with inhabitants of Sidon reinforces the image of him as a Phoenician.

There’s an obvious sense in which the Phoenician dye trade made an impression on Stoicism. There are many references to seafaring, trade, and dye, used as metaphors in Stoic philosophy. The most famous come from the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, written nearly five centuries after Zeno was shipwrecked at Athens. For example, he tells himself to remember that his imperial (Tyrian) purple robe is merely “some sheep's wool dyed with the blood of a shellfish”, and of no real intrinsic value (Meditations, 6.13).

The Foreignness of StoicismThe foreignness of Stoicism, its otherness to the Athenians and other Greeks, is clear from the way that “Phoenician” appears to be used in a somewhat derogatory way by ancient authors to refer to the philosophy. According to Diogenes Laertius, Crates of Thebes, the Cynic, referred to Zeno, who became his student, as “my little Phoenician”.

"Why run away, my little Phoenician?" quoth Crates, "nothing terrible has befallen you." — Diogenes Laertius

The term Phoinikidion (“little Phoenician”) could be affectionate but here seems to be moderately derogatory — not unlike how you’d expect to hear an Athenian refer to a “barbarian” slave. In general, though, using language in this way to downplay, or level, the importance of people and things was quite typical of Cynicism.

Cicero, writing three centuries before Diogenes Laertius, however, uses a similar phrase in Latin, referring to Zeno as “your little Phoenician” (in a fictional dialogue where the Stoic Cato is being addressed). He stresses that the inhabitants of Citium “originally came from Phoenicia”, as we’ve seen, and refers to Zeno as exhibiting the “cunning” supposedly typical of his Phoenician race.

Diogenes Laertius also quotes a satirical poem about Zeno, by his contemporary Timon of Phlius, which begins:

A Phoenician too I saw, a pampered old woman ensconced in gloomy pride.

A later Stoic, Zenodotus, wrote apologetically of Zeno’s Phoenician birth (portraying him not in effeminate but manly terms):

Thou madest self-sufficiency thy rule,

Eschewing haughty wealth, O godlike Zeno,

With aspect grave and hoary brow serene.

A manly doctrine thine: and by thy prudence

With much toil thou didst found a great new school,

Chaste parent of unfearing liberty.

And if thy native country was Phoenicia,

What need to slight thee? came not Cadmus thence,

Who gave to Greece her books and art of writing? — Italics added

His point is that Greeks should not be prejudiced against Zeno for being Phoenician. He compares him to Cadmus one of the greatest heroes of Greek mythology, and the founder of Thebes, who happened to be a Phoenician prince and came originally from the city of Tyre — so not all Phoenicians are bad!

It seems clear from these references in Cicero and Diogenes Laertius, the latter reputedly quoting much earlier sources such as Crates, Timon, and Zenodotus, that the founder of Stoicism was viewed very much as a foreigner. He, and the philosophy he founded, appear to have been looked down upon by some Greeks for this reason. Stoicism was, to some extent, originally seen as a Phoenician and therefore, technically, a barbarian or non-Greek philosophy. We have even seen Zeno being criticized due to Greek (and Roman) prejudices toward the Phoenician race, and defended against the same prejudices by his followers.

Perhaps it would be most accurate to say that Stoicism was originally viewed very much as a Hellenistic philosophy, founded by a Phoenician metic (or immigrant) at Athens, expressed in the Greek language, but (somehow) showing signs of foreign influence, which distinguished it from the Platonism of Polemo’s Academy, and other established branches of Greek philosophy. In short, it was not really a native Greek philosophy in the sense that Platonism and Aristotelianism were. There was originally something slightly alien about the Stoic world-view, perhaps not unlike the presocratic philosophies which had come to Athens from Ionia over a century before Zeno’s time.

It’s also noteworthy that although the Stoic school was based in Athens, most of its subsequent leaders (scholarchs) came from overseas, particularly cities of Asia Minor and the Levant, including Sidon and Tyre, as well as the island of Rhodes, where Phoenicians had settled. (See the partial list on this interactive map.) At least six of the most famous Stoics of the Hellenistic era, in fact, came from the city of Tarsus, or its vicinity, the capital of Cilicia, which was another important centre for maritime trade where the Phoenicians had settled. Tarsus, which was said to have one of the greatest libraries of the ancient world, seems to have had a particularly strong association with Stoic philosophy. A century after Panaetius, the last Stoic scholarch died, Saint Paul was born in the city of Tarsus — Paul was originally known as Saul of Tarsus. Some scholars find traces of Stoicism in his writings.

Of course the resemblance between Zeno, the Hellenized Phoenician of Citium, and Paul, the Hellenized Hebrew of Tarsus, is not purely accidental. The author of the Acts has assuredly put into the mouth of his Paul, with deliberate purpose, phrases characteristic of the teaching which went back to Zeno. Nor is the connection made by the writer an arbitrary one; it is the index of a great fact — the actual connection in history between Stoicism and Christianity. Looking back, we can see more fully than was possible at the moment when the Acts was written, to what an extent the Stoic teaching had prepared the ground in the Mediterranean lands for the Christian, what large elements of the Stoic tradition were destined to be taken up into Christianity. — Edwyn Bevan, Stoics and Sceptics

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Conclusions and QuestionsWhat ideas was Polemo accusing Zeno of pinching? It’s easy to see the influence of the Platonic Academy in early Stoic thought. What could he possibly have meant, though, by saying that Zeno dressed up bits of Platonic philosophy to give them a more Phoenician appearance? As Brunschwig notes:

One would pay much to know what Polemo meant by this "Phoenician makeup": was it a matter of philosophical doctrine, or a matter of expression, style and vocabulary?

An easy answer would have been that Zeno translated Platonic ideas into the Phoenician language but Zeno only ever taught in Greek as far as we know. In De Finibus, Cicero levels a similar criticism at the Stoics for merely rehashing ideas of Platonism in different (Greek) terminology. It’s far from clear how this Stoic philosophical jargon could be described as “Phoenician”, though.

Perhaps there’s another way in which Zeno’s Stoicism may have appeared “Phoenician” to the Greeks. Stoic teachings were divided into three broad topics: ethics, physics and logic. It seems difficult to imagine how Zeno could have dressed Academic logic up in a Phoenician style. Stoic ethics resembled that of Polemo but was more austere, apparently under the influence of Cynic philosophy. It’s difficult to imagine how Zeno’s ethics, therefore, could be described as Phoenician in appearance. My best guess is therefore that Polemo meant Zeno’s physics somehow came across as Phoenician.

The main characteristic of early Stoic physics was that it was pantheistic and influenced by the presocratic philosophers known as the Ionians. Plato identified the divine with the transcendent realm described by his famous Theory of Forms. The Stoics completely rejected this metaphysical view and instead identified their God with the universe considered as a whole, which they considered to be a rational living being, called Zeus. We know very little about the theology of the Phoenicians but they appear to have followed a form of the Canaanite religion, which worshiped the semitic god Baal, typically represented by the image of a bull. (The image of the bull also occurs in the symbolism of Stoic philosophy, e.g., Epictetus appears to compare the Sage to a bull, and Zeno compared the ideal republic to a herd of cattle.) He was known by Phoenicians as Baal Shamen or Lord of the Heavens, and worshipped as a storm god, representing life and fertility, sometimes equated with the Greek god Zeus. The Canaanite religion, however, appears to have been polytheistic rather than pantheistic.

In Greek myth, the Phoenician princess Europa is abducted by Zeus shaped as a bull

In Greek myth, the Phoenician princess Europa is abducted by Zeus shaped as a bullStoic physics drew on the work of Ionian philosophers, such as Heraclitus, who were known for their pantheism. Although the Ionians were Greeks, they lived in colonies on the coast of Asia Minor, under Persian rule until the start of the fifth century. In Ionia, therefore, Greek culture mingled with influences from Persia and Phoenicia. Moreover, the historian Herodotus claimed that Thales, the founder of Ionian philosopher, though born in the Ionian city of Miletus, was, like Zeno, a Phoenician. “Thales a man of Miletus,” he calls him, “who was by descent of Phoenician race.” Diogenes Laertius later expands upon this, writing, “Herodotus, Duris, and Democritus are agreed that Thales […] belonged to the Thelidae who are Phoenicians, and among the noblest of the descendants of Cadmus and Agenor.” According to this account, therefore, Thales came from a family of Phoenician nobles. Other accounts refer to Thales as Greek, so it’s likely he was a Milesian citizen with some Phoenician blood in his family.

Unfortunately, we know relatively little about Thales’ philosophy, and there are no direct links with Zeno’s Stoicism. However, some scholars consider him to have been a monist, and a sort of pantheist. The Ionian philosophers who came after him were certainly associated with pantheism and, as we’ve seen, in the case of Heraclitus, there seems to be a clear influence on Stoicism.

These observations are, sadly, inconclusive. We’re left with some questions. Could the Phoenician appearance of Stoicism somehow have been due to the unique jargon that it used after all? Could Polemo somehow have been referring to the influence of Phoenician religion, the worship of Baal, on Stoic theology, and their distinct conception of Zeus? Or could the influence on Stoic physics of Ionian philosophy, founded by the Phoenician Thales, with its emphasis on monism and pantheism, have been perceived as sufficiently Phoenician to justify the remark? Perhaps we’ll never know for sure but I hope these reflections might inspire someone else to spot a connection, which could shed further light on the origins of Stoicism, and perhaps thereby the meaning of some of its more obscure concepts.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

December 4, 2023

Stoicism Books as Xmas Gifts

It’s that time of year again. If you’re into Stoicism and looking for ideas, we created Verissimus, our graphic novel about Marcus Aurelius, to provide an entertaining (dare I say “fun”?) introduction to the philosophy, suitable for young and old alike. It makes the perfect Christmas gift.

Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius is a full-color 270 page sweeping historical epic, with artwork by award-winning illustrator Zé Nuno Fraga, available in both ebook and hardback formats. It is an Amazon editor’s pick for Best History Book, and has now been reviewed by nearly 250 readers, with a 4.8 star rating. Available now from Amazon and other book stores.

We created Verissimus to make Stoic philosophy more accessible to a wider audience. It is directly based on the surviving historical accounts of Marcus Aurelius’ life, and interweaves sayings and teachings from his philosophy, with an appendix summarizing Stoic practices for overcoming anger.

What other authors think…

What other authors think…"A superb graphic novel that provides stunning insights into one of the most interesting figures of antiquity, as well as into the philosophy that guided him throughout his life." --Massimo Pigliucci, author of How to Be a Stoic

"Donald Robertson is one of my favorite writers about Stoicism." –-Ryan Holiday, #1 New York Times bestselling author and founder of The Daily Stoic

“Verissimus represents the vanguard of the next phase of the ongoing Stoic renaissance.” –-William B. Irvine, author of A Guide to the Good Life

"A remarkable work that is awesome in its conception and execution." --Karen Duffy, author of Backbone

"Whether you're new to Marcus Aurelius or already know him as a friend and guide, this graphic 'novel' will open your eyes. The book truly makes him a three-dimensional person, not just the writer of Meditations. Author and artist have found – invented, I might say – a brilliant combination of entertainment and education." –-Robin Waterfield, translator of Marcus Aurelius and Epictetus

"Superb rendering of Marcus' action-filled life and times. Readers are in safe hands knowing the text comes from Stoic philosophy expert Donald Robertson. Don't be fooled by the graphic nature of this book, you will learn a lot – and be inspired at the same time." –-Tom Butler-Bowdon, author of the 50 Classics series

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

December 1, 2023

Book Review: Lessons in Stoicism by John Sellars

Lessons in Stoicism: What Ancient Philosophers Teach us About How to Live (2019) is a recent introduction to Stoic philosophy by John Sellars, published by Penguin books.

Sellars is a lecturer in Philosophy at Royal Holloway, University of London and a member of Wolfson College, Oxford. He is also the author of two other well-received books on this subject: Stoicism (2006) and The Art of Living (2009), and the editor of the recent Routledge Handbook of the Stoic Tradition (2016). He’s one of the founder members of Modern Stoicism, the group behind Stoic Week. (For transparency: I’m a member of the same team.)

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

This is a very small book, only 96 pages, but that’s part of its appeal. It presents a very concise and yet authoritative account of Stoic philosophy aimed at the lay reader, although written by a leading scholar in this field. In that respect, it reminds me of Stoicism: A Very Short Introduction by Brad Inwood, professor of philosophy and classics at Yale. More and more books on Stoicism are appearing and there are many articles now on the Internet, although the quality varies and often articles and even books on this subject perpetuate basic misconceptions. Sellars’ book, like Inwood’s, helps to address this problem by presenting Stoicism in an accessible manner, while nevertheless being based upon many years of serious academic scholarship.

Lessons in Stoicism is currently available in hardback, ebook, and audiobook formats. (I hope the audio version helps make it accessible to a wider audience.) The table of contents provides a good flavour of the book:

The Philosopher as Doctor

What Do You Control?

The Problem with Emotions

Dealing with Adversity

Our Place in Nature

Life and Death

How We Live Together

Sellars begins by emphasizing that what I call the “medical model of philosophy”, the idea that philosophy is a psychotherapy, was explicitly stated by the Stoics and, as Sellars notes, goes back at least as far as Socrates, and quite probably even to earlier Greek philosophers. The school that placed most emphasis, though, on the notion of philosophy as a psychological therapy was Stoicism:

The philosopher, [Epictetus] says, is a doctor, and the philosopher’s school is a hospital — a hospital for souls.

It’s important to spell this out because several modern critics of Stoicism-influenced self-help have (rather bizarrely) tried to argue that modern psychotherapists, myself included, are completely wrong to interpret it in this way. The Stoics made it crystal clear, though, that they conceptualized philosophy as being, among other things, a form of medicine or therapy for the psyche. It’s not a new idea!

The task of the philosopher, conceived as a doctor for the soul, is to get us to examine our existing beliefs about what we think is good and bad, what we think will benefit us, and what we think we need in order to enjoy a good, happy life.

Sellars also dedicates a whole chapter to the fundamental Stoic doctrine that some things are up to us and other things are not. Earlier authors such as William Irvine somewhat confused readers by implying that this distinction was meant to distinguish between external things which they assume to be under our influence to varying degrees. (Hence, Irvine suggested introducing a “Trichotomy of Control”.) Sellars makes it clear, though, that Epictetus said he was distinguishing between our own voluntary judgments and everything else. Moreover, as Sellars highlights, the Stoics recognized that much, perhaps most, of what goes on in our minds is involuntary. It’s specifically our voluntary judgments, though, that they’re interested in demarcating from the rest of our experience.

Sellars also directly tackles the mistaken tendency to conflate Stoicism, the Greek philosophy, with stoicism, the modern concept of an unemotional “stiff upper-lip” coping style.

In modern English the word ‘stoic’ has come to mean unfeeling and without emotion, and this is usually seen as a negative trait.

That is definitely not what “Stoicism” means, although the two things are frequently confused, including in many articles on the subject on the Internet.

Contrary to the popular image, the Stoics do not suggest that people can or should become unfeeling blocks of stone.

The ancient Stoics themselves frequently explained that their goal was not to be unfeeling like a man made of stone, i.e., a statue. It is unnatural and inhuman for someone to be totally unemotional, as though they have a heart of stone or iron, and it is therefore unStoic.

The Stoics certainly do not envisage turning people into unfeeling blocks of stone. So, we’ll still have the usual reactions to events — we’ll jump, flinch, get momentarily frightened or embarrassed, cry — and we’ll still have strong caring relationships with those close to us. What we won’t do, however, is develop the negative emotions of anger, resentment, bitterness, jealousy, obsession, perpetual fear or excessive attachment. These are the things that can ruin a life and that the Stoics think are best avoided.

Sellars frames Stoic metaphysics and theology in relatively naturalistic terms:

The official Stoic view is that there is a rational principle within Nature, responsible for its order and animation. They call this ‘God’ (Zeus), but it is not a person, and nothing supernatural — it simply is Nature.

He compares this to the “Gaia Hypothesis” of environmentalist and futurist James Lovelock. “For the Stoics,” writes Sellars, “‘God’ and ‘Nature’ are just two different names for the same single living organism that encompasses all things.”

Sellars also helps to refute the misconception that Stoics are somehow passively fatalistic — something obviously untrue when we consider the lives of real historical Stoics such as Cato the Younger and Marcus Aurelius.

Our actions can and do make a difference. They can themselves be causes at play that contribute to the outcome of events. As one ancient source put it, fate works through us. We are ourselves contributors to fate and parts of the larger natural world governed by it.

The point the Stoics were making was basically that once things have turned out as they have there’s no point complaining or wishing that they were otherwise. Sellars rightly notes that this “philosophical attitude” toward adversity, which accepts the reality of our situation and urges us to get on with life regardless, is foundational to the ancient Stoic therapy of the passions. He quotes Marcus Aurelius:

Nature gives all and takes all back. To her the man educated into humility says: ‘Give what you will; take back what you will.’ And he says this in no spirit of defiance, but simply as her loyal subject.

Some (almost fundamentalist) modern proponents of Stoic theology are very hostile to the mere suggestion that ancient Stoics could have seriously considered any form of agnosticism. They even deny that any modern scholar would ever entertain such a view. However, that’s demonstrably not the case. Sellars, for instance, has repeatedly noted that Stoics such as Marcus Aurelius were willing to at least question the providential nature of the universe.

While Seneca stressed the providential order within Nature, Marcus focuses more on the inevitability of events. In a number of passages in his Meditations, he appears to express agnosticism on whether Nature is a rational, providential system or merely a random accumulation of atoms banging together in an infinite void. Marcus was no physicist, and his duties as emperor hardly left him time to investigate the matter in detail himself. In any case, his final view was that for practical purposes it doesn’t matter a great deal. Whether Nature is ruled by a providential deity, a cybernetic feedback system or blind fate, or is simply the chance product of atomic interactions, the response from us should always be the same: accept what happens and act in response as best we can.

Whether Providence exists or the universe is ruled by mere physical chance — “God or atoms”, as Marcus put it — either way Stoic Ethics is still the most philosophically justified philosophy of life. Whether or not we believe that the cosmos is a single living creature, which the Stoics called Zeus, what matters is that we’re able to view our own lives as part of a greater whole:

The lesson here is that we are but parts of Nature, subject to its greater forces and inevitably swept along by its movements, and we shall never be able to enjoy a harmonious life until we fully comprehend this.

Sellars broaches the subject of our own death through references to the concept of making the best use of our time, from Seneca’s On the Shortness of Life.

Learning to live well is, paradoxically, a task that can take a lifetime. The wisest people of the past, Seneca adds, gave up the pursuit of pleasure, money and success in order to focus their attention on this one task.

Sellars goes on to discuss Epictetus’ portrayal of life as a gift, which can be taken away at any moment. Rather than bitterly resent this or deny it, we should embrace our mortality and make the best use of the opportunity that life affords us to excel by cultivating wisdom and virtue.

Another all-to-common misconception of Stoicism is the idea that it’s somehow self-centred. Many modern fans of Stoicism see it in this way, unfortunately. It’s actually quite baffling because one of the major themes of The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius is how to live in harmony with the rest of mankind: social virtue, cosmopolitanism, brotherly love, natural affection, etc. How can anyone read The Meditations without noticing that these and similar ideas are emphasized on virtually every page?

As Sellars notes, the Stoics, like Aristotle before them, asserted that “human beings are by nature social and political animals.” Sellars, however, links this to the notion found in Epictetus, and earlier Stoics, that we have a duty to fulfill certain natural and social roles to the best of our ability, such as being a good parent, being a good spouse, doing our job well, and so on. However, our ultimate duty is to be a good human being in the broadest sense.

Beyond specific roles, such as being a parent, we might also think more broadly about being a member of a much wider community of people, and most broadly of all as simply being a member of the human race. Does this involve any duties or responsibilities? The Stoics think it does. We have a duty of care to all other human beings, and they suggest that as we develop our rationality we shall come to see ourselves as members of a single, global community of all humankind.

As Seneca puts it, we have two levels of social duty: one toward the universal city, embracing all of mankind, and another toward the specific community to which we have been assigned by accident of birth. For Stoics, to neglect our social obligations and kinship with the rest of mankind is to wrench ourselves unnaturally apart from humanity, which is essentially a pathological form of spiritual and psychological alienation. “For the Stoics,” writes Sellars, “people are people, all equal in their shared rationality and instinct for virtue.”

“This focus on sociability and equality challenges the idea”, as Sellars puts it, “that Stoics were indifferent to other people” — something which is in fact another surprisingly widespread misconception of the philosophy.

He also links this to a discussion of the Stoic doctrine that we should be cautious about the company we keep because of the effect it has upon us. It’s worth quoting in full what he says here because it bears on the modern development of Stoic communities:

So, if you are trying to develop some new, positive habits, it may be best to avoid the company of those whose lives embody everything you are trying to escape. Instead, try to spend time with those whose values you share or admire. This is one of the reasons why philosophers in antiquity tended to group together into schools. It also probably stands behind the monastic traditions of various world religions. It is why aspiring Stoics gathered together in antiquity, in places such as Epictetus’s school, and it’s why today people who want to draw on Stoicism in their daily lives are often keen to make contact with others trying to do the same, either in person or online.

Ancient Stoics did not live in a bubble, isolated from the rest of humanity. They married, had children, formed communities, taught students, wrote books, engaged in politics, fought in defence of their nations, risked and even sacrificed their lives standing up to tyrants — for the welfare of their communities and ultimately the benefit of mankind.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

November 24, 2023

Stoicism for Mothers

From a bust of Domitia Lucilla

From a bust of Domitia LucillaThe Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius was the last famous Stoic of antiquity. His personal reflections on applying Stoic philosophy to daily life, The Meditations, begin with a chapter contemplating the virtues of his family members and most cherished tutors, including his mother, Domitia Lucilla.

His father died when Marcus was only a small child, aged around three, leaving him to be raised in the care of his paternal grandfather and his widowed mother.

Domitia Lucilla was a wealthy and cultured Roman noblewoman, the daughter of the statesman Calvisius Tullus, who had served twice as consul. She died while Marcus was Caesar, before having a chance to see him acclaimed emperor. We can see from Marcus’ private letters to his rhetoric tutor, Marcus Cornelius Fronto, that he loved her very dearly. In The Meditations, he thanks the gods that “although my mother was destined to die at an early age, she at least spent her last years with me” (1.17).

She was a woman of considerable means and influence, who owned an important tile and brick factory outside Rome, near the banks of the River Tiber. However, Marcus describes her generosity and the simplicity of her lifestyle, “far removed from that of the rich” (1.17). These qualities perhaps inspired his own love of simplicity and moderation, paving the way for his later education in Stoic philosophy.

Nevertheless, at first, Lucilla perhaps felt Marcus went too far in his embrace of the traditional Cynic-Stoic attire and lifestyle.

He studied philosophy with ardour, even as a youth. For when he was twelve years old he adopted the dress and, a little later, the hardiness of a philosopher, pursuing his studies clad in a rough Greek cloak and sleeping on the ground; at his mother’s solicitation, however, he reluctantly consented to sleep on a couch strewn with skins. (Historia Augusta)

A few years later, Marcus began formal study of Stoic philosophy and his main tutor was to be a Roman statesman called Junius Rusticus. Marcus also mentions that he learned from Rusticus, “to write letters in an unaffected style, as he did when he wrote to my mother from Sinuessa”, a city on the Italian coast south of Rome (1.7). Rusticus and Lucilla would have been around the same age. He and Marcus’ mother were clearly friends and it’s tempting to wonder whether she may have had some hand in the appointment of Rusticus as one of her son’s main tutors in Stoic philosophy.

Marcus lists the qualities he most admired in Lucilla and sought to emulate as follows:

From my mother, piety and generosity, and to abstain not only from doing wrong but even from contemplating such an act; and the simplicity, too, of her way of life, far removed from that of the rich. (Meditations, 1.3)

Lucilla’s notable generosity and love of simple living, despite her immense wealth, perhaps influenced Marcus’ decision to give away much of his own family inheritance.

Later, when his mother asked him to give his sister part of the fortune left him by his father, he replied that he was content with the fortune of his grandfather and relinquished all of it, further declaring that if she wished, his mother might leave her own estate to his sister in its entirety, in order that she might not be poorer than her husband. (Historia Augusta)

Later, the historian adds that Marcus gave away part of the fortune he inherited from his mother to his sister’s son, after her death.

Finally, he mentions in the passage above that his mother’s example instilled in him a sense of piety and a moral conscience that warned him against entertaining evil thoughts even in the privacy of his own mind, a theme that he returns to several times throughout The Meditations. For example,

I have often marvelled at how everyone loves himself above all others, yet places less value on his own opinion of himself than that of everyone else. At all events, if a god or some wise teacher presented himself and told him not to entertain any thought or idea in his mind without stating it aloud as soon as he had conceived it, he would not abide it for even a single day. So much greater is our respect for what our neighbours think of us than what we think of ourselves! (12.4)

Although The Meditations was probably written at least a decade after her death, Marcus is still reflecting on the lessons he learned from his mother and how the example she set in her own life shaped his character. Whether or not she played some role in introducing him, as a child, to Stoic philosophy, she certainly helped lay the foundation upon which his later training would be built by instilling old-fashioned Roman values in her son compatible with those of Stoic ethics.

📝 Read this story later in Journal.

🍎 Wake up every Sunday morning to the week’s most noteworthy stories in Wellness waiting in your inbox. Read the Noteworthy in Wellness newsletter.

November 23, 2023

My Stoicism Book Recommendations

Amazon have a new feature that allows authors to recommend books. So below are some of my favorite books on Stoicism. You can follow my profile and check out all of my book recommendations on my Amazon author page (scroll down to see them).

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Some Stoicism Book RecommendationsAmazon asks authors to recommend some of their own books for readers with different needs, etc., but also to pick five books by other authors that fit different categories. Here are the ones I chose…

The Practicing Stoic: A Philosophical User's Manual by Ward FarnsworthThis is a great introduction to Stoicism. It’s beautifully written, and contains many interesting excerpts from classical texts with a wonderful commentary from the author. The Socratic Method by the same author is also a great book.

Lives of the Stoics: The Art of Living from Zeno to Marcus Aurelius by Ryan Holiday, Stephen HanselmanThis is a unique book. The scholarship is excellent. It provides short biographies of many ancient Stoics, including information you just won’t find anywhere else. It’s a bit like Diogenes Laertius’ Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, an ancient collection of biographical essays about various philosophers. If you’re interested in Stoicism and history, this is definitely worth reading.

Epictetus: A Stoic and Socratic Guide to Life by A. A. LongThis is the best academic text on Epictetus. It’s fairly easy to read, and I know many non-academics have found it helpful. It focuses on the influence of Socrates on Epictetus, a subject dear to my own heart! Prof. Long is a leading academic authority on Epictetus.

The Inner Citadel: The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius by Pierre Hadot, Michael ChaseThis was one of the books that inspired my initial interest in Stoicism. It’s the best academic text on Marcus Aurelius but it’s so easy to read that it’s found an audience among non-academics as well. Hadot focuses on the role of spiritual exercises, such as contemplative practices, in the Meditations. His other books on ancient philosophy are also fantastic.

365 Ways to Be More Stoic: A day-by-day guide to practical stoicism by Tim Lebon

365 Ways to Be More Stoic: A day-by-day guide to practical stoicism by Tim LebonI better declare my bias and say that the editor, Kasey Pierce, is my wife. Also, Tim LeBon is a good friend, whom I’ve known for many years — we’re both CBT practitioners. This is a great introductory book, though, which fills an important gap in the market. It contains many different examples from real people who have applied Stoicism in their daily lives in various ways. It has a bit more diversity, compared to other modern self-help books on Stoicism, e.g., Kasey helped bring a much-needed female perspective to the subject, which I think many female readers will appreciate.

You can also follow me on Goodreads, to receive notifications when my publisher does a book giveaway.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

November 21, 2023

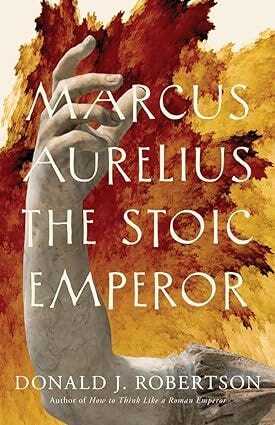

Marcus Aurelius' Father

Below you can read an exclusive excerpt from the first chapter of my new book, Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor, which is part of the Yale University Press Ancient Lives series. It is due out in Feb 2024; by pre-ordering your copy, you can help it to reach a wider audience.

Ebook and audiobook (narrated by me) editions will be forthcoming. Please get your copy today from Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or visit the publisher’s website for other retailers. Thanks for your support!

From Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor

From Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor[Marcus Aurelius’ father] was named Marcus Annius Verus, after his own father. He was, like Lucilla, born into a wealthy and influential senatorial family. They hailed from the Roman province of Hispania Baetica (southern Spain), where they had made their fortune from olive oil. Verus’ side of the family claimed descent from Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome. Renowned as a wise and just ruler, Numa was credited with founding the solemn rites of the Roman religion.

A popular tradition, whose historical authenticity was scorned even in antiquity, claimed he brought to Rome the teachings of the 6th century BCE philosopher Pythagoras of Samos, whose Greek followers had settled around the southern tip of the Italian peninsula. Although their historical connection with Numa and Pythagoreanism is probably a myth, it reveals something of the Annius Verus family’s character and reputation. Marcus was the latest in a line of reputedly peaceful and benevolent nobles, with links to archaic religion and philosophy.

Given his family history and imperial connections, his father must have been expected to reach the office of consul.

Marcus’ father also had a touch of imperial blood in his veins. He was not only the nephew of Empress Vibia Sabina, wife of Hadrian, but also a distant relative of Emperor Trajan on his mother's side. His sister, Faustina (the Elder), was married to a senator who would later become the emperor known as Antoninus Pius. Marcus’ aunt was therefore destined to become an augusta, or empress. Given his family history and imperial connections, his father must have been expected to reach the office of consul. Instead, having reached the preceding rank of praetor, his career was unexpectedly cut short.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Sometime in the early 120s, when Marcus was around three or four years old, his father died. We don’t have any more details. Just a few years into her marriage, Lucilla was left a widow, caring for two small children. One of the sources claims that “at the beginning of his life" Marcus assumed the name of his maternal great-grandfather, Catilius Severus, perhaps implying the old man temporarily adopted him after he lost his father. Lucilla was still a teenager at the time, or in her early twenties. She never remarried.

This first tragic loss shaped Marcus’ character more than the many others he was to experience. We can detect, throughout the rest of his life, a constant interplay between his natural sensitivity to grief and a studied philosophical attitude toward his own death and that of others. “Lucilla buried Verus”, he writes bluntly of this first tragic loss, looking back on events half a century later. And so it goes on, he muses, ever the same, with one life after another. Marcus Annius Verus and all the others were merely “creatures of a day", gone before long. Yet he still recalled them, and shed tears for them.

Marcus barely had a chance to know his father. Nevertheless, he would pray before his image in the family shrine, or lararium, honoring his memory, for the rest of his days. From the fragments of his own childhood memories, and the stories he heard about him, he knew that his father possessed both manliness with modesty. Later he asserts that the word “manly” (arrenikos), correctly defined, means, not tough and aggressive, but kind and full of natural affection.

Marcus, I think, remembered his father as the embodiment of a gentle and affectionate man, at odds with the vicious cliques of Roman elite society. Turning to one male role-model after another, Marcus, struggled to live up to his father’s example. Like many troubled young men, his own feelings of anger would at times get in his way.

Experts Praise the Book

Experts Praise the Book“Few historical figures are as fascinating as Marcus Aurelius, the emperor-philosopher. And few writers have been so effective at bringing his complex life and character to the attention of modern readers as Donald Robertson.”—Massimo Pigliucci, author of How to Be a Stoic: Using Ancient Philosophy to Live a Modern Life

“Robertson has written a very thorough and very readable account of Marcus’s life and the events and people that shaped him. Anyone who wants to understand the author of Meditations should read this book.”—Robin Waterfield, author of Marcus Aurelius, Meditations: The Annotated Edition

“Donald Robertson guides us into the world of a philosopher-emperor whose humility and Stoic teachings fill the pages. We are indebted to Robertson for this wonderful account of the emperor who penned notes to himself while in battle that would be later known as the Meditations and read by millions for philosophical inspiration. Simply spellbinding.”—Nancy Sherman, author of Stoic Wisdom: Ancient Lessons for Modern Resilience

“This highly readable biography is the perfect place to begin for anyone who wants to learn more about the man behind the Meditations.”—John Sellars, author of Marcus Aurelius (Philosophy in the Roman World)

“Robertson’s biography provides a compelling narrative of Marcus’ life, carefully based on the primary sources. He brings out very clearly the life-long significance of Stoicism for Marcus and the interplay between philosophy, politics, and warfare.”—Christopher Gill, author of Marcus Aurelius: Meditations, Books 1-6

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

November 16, 2023

Wish things to happen as they do

CommentaryDo not seek to have everything that happens happen as you wish, but wish for everything to happen as it actually does happen, and your life will be serene.

This is one of my favourite passages from the Handbook. It’s beautifully concise. That said, it needs to be understood within the context of Stoic philosophy. If we accepted events that befall us rather than wishing they were otherwise, our lives would go more smoothly. The expression Epictetus actually uses for “your life will be serene” here (euroeseis, literally, “you will flow smoothly”) appears to be an allusion to an early Stoic definition of fulfillment (eudaimonia) as a smoothly flowing life.

It should remind us of the famous analogy attributed to Chrysippus. Life is like a dog tied to a cart. If the dog runs along behind the cart, in harmony with it, by keeping up, it will go smoothly. If it tries to pull against the leash, though, or run in a different direction, it will be pulled along anyway by the cart in the same direction, but roughly, and it will suffer. That doesn’t mean that we should never try to change the world but rather that we need to accept reality, and adapt to it, before we can change it.

November 14, 2023

Stoicism for Leaders and Entrepreneurs

Every day, it seems, more entrepreneurs and leaders in the business community are becoming interested in Stoic philosophy. Stoicism offers a whole philosophy of life, which promises to help us attain not only greater emotional resilience in the face of adversity, but also a deeper sense of purpose and meaning in life, and in our work.

The Wall Street Journal published a review of my book How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, which perhaps sums up Stoicism’s contemporary appeal.

Marcus is remembered not merely for his long reign but for his practice of Stoicism — a school of philosophy founded in Athens by Zeno of Citium around 300 B.C. Stoicism counsels its adherents not to place too much importance on things outside their control. Rather than fret about the frustrations of our daily lives, the Stoics advise, it is better to bring one’s will in accord with nature and approach the present moment with composure. […] Marcus’ worldview was not an idle intellectual exercise […] but a form of wisdom forged by real-world experiences of friendship, loss and crisis. — The Wall Street Journal

The transcript of an interview about Stoicism that I did recently for Wharton business school’s radio station was published on the World Economic Forum’s website. I was asked how Stoicism works in the business community…

It’s a strange thing. I didn’t anticipate this, but one of the biggest groups of people interested in it seems to be millennials who work in the tech industry. I feel like it [kind of took] root in Silicon Valley. Where I live in Toronto, I meet a lot of young people working in software development or the tech industry in general who are particularly drawn to this philosophy.

Tim Ferriss & Ryan Holiday

Tim Ferriss & Ryan HolidayMost of the younger people I meet who are into Stoicism actually say they were introduced to the philosophy through references made to it by Tim Ferriss or Ryan Holiday.

Ferriss has a whole section of his website devoted to Stoic resources, including the free PDF and (paid) audiobook versions of his own Tao of Seneca book. Tao of Seneca consists of the famous “moral letters” of Seneca to his friend and fellow-Stoic Lucilius, alongside which Ferriss has included thoughts from various “modern Stoics”. (One of the chapters in Tao of Seneca contains an interview I gave for Ryan Holiday’s The Daily Stoic website.) Ferriss says that his own life was transformed in 2004 when he discovered the writings of Seneca.

[Stoicism] can be thought of as an operating system for thriving in high-stress environments. At its core, it teaches you how to separate what you can control from what you cannot, and it trains you to focus exclusively on the former. — Tim Ferriss, The Tao of Seneca

However, Ferriss says that in addition to building emotional resilience for coping with negative experiences in life, “Stoicism can also be used to maximize the positive”.

For this reason, Stoicism has spread like wildfire throughout Silicon Valley and the NFL in the last five years, becoming a mental toughness training system for CEOs, founders, coaches, and players alike. Super Bowl champions like the Patriots and Seahawks have embraced Stoicism to make them better competitors. In my own life, the results have been incredible. — Tim Ferriss, The Tao of Seneca

Ferriss actually says that looking back on the preceding two decades of his life, he credits “nearly all of the biggest successes — and biggest disasters averted — to my study of Stoicism and, specifically, the writing of Seneca.”

Tim Ferriss also recommends the works of Ryan Holiday, author of The Obstacle is the Way and co-author (with Stephen Hanselman) of The Daily Stoic. In his article Stoicism 101: A Practical Guide for Entrepreneurs, Holiday writes:

For those of us who live our lives in the real world, there is one branch of philosophy created just for us: Stoicism. It doesn’t concern itself with complicated theories about the world, but with helping us overcome destructive emotions and act on what can be acted upon. Just like an entrepreneur, it’s built for action, not endless debate. — Ryan Holiday, Stoicism 101

Holiday’s bestselling books have introduced countless people to Stoicism, especially younger generations of readers. Whenever I speak to people who are into Stoicism and work in the tech industry, in particular, I can guess that they’ve probably read The Obstacle is the Way.

Business Leaders on Stoicism

Business Leaders on StoicismSeveral prominent CEOs have likewise spoken about the influence of Stoic philosophy on their lives. For example, in a recent interview, Jules Evans asked Jonathan Newhouse, the CEO of Condé Nast, how he got into Stoicism.

It was 1999. I ran into Alain de Botton in a restaurant. He was having dinner with a friend of mine. He said he was working on a book of philosophy, and mentioned Seneca, who I’d never read. I went out and brought Seneca’s Letters From a Stoic. And it just blew me away. I found it impeccably logical. That led me on to Marcus Aurelius and Epictetus. I read just about everything I could. Now I usually take one of the Stoic books with me when I travel. I incorporated it into my thinking and it’s shaped the way I think and interact with the world in a very positive way.

He explains very succinctly how Stoic philosophy influences his worldview:

People devote a lot of time and emotional effort to things that are beyond their control — what other people do, how other people react to them, even the weather. And they set themselves up for pain, anxiety, disappointment and fear. The Stoics recognised that it was foolish, or counterproductive, to attach oneself to things that are beyond one’s control, when there are things within one’s control — one’s thoughts, attitudes and moral purpose.

I loved the idea that you could make your goal to live a life of moral purpose. I was very taken with the ethical and moral point-of-view of Stoicism. When you read the Stoics, you often come across the word ‘virtue’. They saw the goal of the wise person as to lead a virtuous life. Today, the word ‘virtue’ is almost never heard, except ironically. If you asked 100 people what their goal was in life, hardly any would say leading a virtuous life.

Eugenio Pace, the CEO and co-founder of Auth0, likewise writes in a Forbes article titled Can Philosophy Influence Business? Here’s What The Stoics Have Taught Me,

Being an entrepreneur in the tech world means creating new experiences, opening untapped markets, and forging new paths. Starting a business is risky and involves charting foreign territory. That’s why I find the teachings of the Stoics important for remaining grounded through tumultuous endeavors. — Eugenio Pace in Forbes

Pace adds the following Stoic advice for coping with stress at work,

Some More Articles on StoicismEpictetus said, “Some things are up to us, and some are not up to us.” As a fellow technology entrepreneur, founder and CEO, the best advice I have for liberating yourself from anxieties that make you less happy and productive is simple: Stop worrying about what you can’t control.

Forbes magazine have actually covered Stoicism several times in recent years. Chris Myers, the co-founder and CEO of BodeTree, writes in How One Struggling Entrepreneur Found Solace in the Ancient Philosophy of Stoicism,

Stoicism, at its core, reminds us that life and everything in it, is impermanent. Focusing on our circumstances or pinning our happiness on the attainment of possessions is a surefire recipe for disappointment. The Stoics, such as Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, instead encourage us to free ourselves from the control such pursuits exert over us and focus on the things that are in our direct control: our thoughts, feelings, and desires. In this sense, Stoicism is uniquely suited to serve the needs of entrepreneurs. — Chris Myers in Forbes

He concludes, “In helping us to identify what we can control in our lives and to find happiness in what we already have, Stoic philosophy allows us to mute the terrible emotional roller coaster that is entrepreneurship.”

Stoicism has also been applied to quite specific challenges in the modern workplace. Adam Piercey, an engineering technologist, wrote a recent Medium article on Stoicism in Tech for Better Programming, which explores specific ways Stoicism can be used to handle stressful situations like peer review. He applies wisdom from Marcus Aurelius to the challenge of receiving critical feedback a software engineer.

As Marcus said, you should “immediately consider on the basis of what opinion about good or evil he did wrong.” If you choose to view the feedback as constructive and positive, you can learn and proceed. The Stoics believed that we should welcome criticism in this spirit and that our role is to make the best use of criticism. If you begin any feedback experience with the mindset that it comes from a place of good intentions, there is a significant opportunity to learn and grow. — Adam Piercey in Better Programming

In another Forbes article, titled Five Reasons Why Stoicism Matters Today, Rob Goodman and Jimmy Soni, authors of Rome’s Last Citizen, argue that Stoicism is “a philosophy for leadership”.

Stoicism teaches us that, before we try to control events, we have to control ourselves first. Our attempts to exert influence on the world are subject to chance, disappointment, and failure — but control of the self is the only kind that can succeed 100% of the time. From emperor Marcus Aurelius on, leaders have found that a Stoic attitude earns them respect in the face of failure, and guards against arrogance in the face of success. — Goodman and Soni in Forbes

In an article titled Why Today’s Best Business Leaders Look to Stoicism, Aytekin Tank, the founder and CEO of Jotform, writes:

[W]hat if I told you that there’s a school of philosophy dating back to ancient Greece that can help you handle all of these obstacles on a daily basis and, as a bonus, may even enrich your quality of life? And better still, you don’t have to be a scholar to figure out how to use it. It’s called Stoicism, and it’s a practical philosophy that’s used by some of today’s greatest thinkers and business minds, including Tim Ferriss, Ryan Holiday, Arianna Huffington and Jack Dorsey. — Tank in Entrepreneur

He lists the main ways in which Stoicism can help entrepreneurs as:

Setting priorities, by focusing on what’s essential

Curbing stress, by distinguishing what is up to us from what is not

Stopping procrastinating, by being aware of our own mortality and the precious nature of time

Managing fear, by premeditatio malorum or the systematic anticipation of future misfortunes

A few years ago now, Carrie Sheffield, founder of the digital media startup Bold TV, interviewed me for a Forbes article titled Want An Unconquerable Mind? Try Stoic Philosophy. She opens by stating that the ideas of ancient Stoics “hold fascinating promise for business and government leaders tackling global problems in a turbulent, post-recession slump.”

Prominent business thinker Nassim Nicholas Taleb praises Stoic philosophy in his Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder, a book that Stoic Week organizer Donald Robertson says nudged many curious readers toward Stoicism. Robertson, a Scottish-born therapist and classics enthusiast, led workshops on psychological resilience for managers at oil giant Shell called “How to think like a Roman Emperor,” based on the life of stoic philosopher-king Marcus Aurelius. — Sheffield in Forbes

Taleb’s bestselling book, Antifragile, mentioned above, contains a whole chapter dedicated to his Stoic hero, Seneca. Indeed, Taleb actually says that Seneca “solved the problem of antifragility […] using Stoic philosophy”. Taleb rightly emphasized that Stoic philosophy is not about being totally unemotional, rather it’s about replacing unhealthy emotions with healthy ones.

Seen this way, Stoicism is about the domestication, not necessarily the elimination, of emotions. It is not about turning humans into vegetables. My idea of the modern Stoic sage is someone who transforms fear into prudence, pain into information, mistakes into initiation, and desire into undertaking. — Taleb, Antifragile

We went on to discuss the famous Stoic “Dichotomy of Control” and how it might be related to the psychology of leadership.

“Anyone in a leadership role must come to terms quickly with the paradox of their position: that leaders must wield power but that often so much that happens lies outside of their control,” Robertson told Forbes. “How do we accept the limits of our power without slumping into passivity?” — Sheffield in Forbes

She also asked me about common misconceptions of Stoicism.

Robertson said people sometimes confuse stoicism with submissiveness, but calls this “a very superficial misunderstanding.” Students of ancient stoicism tended to be sons from wealthy, cosmopolitan families. Many went on to rule empires or advise great leaders in commerce and war. “Can you point to a single historical stoic who sat on his hands?” quips Robertson... “It’s just not in the nature of their philosophy to be doormats or stay-at-home types.”

The Economist’s 1843 Magazine ran an article recently on “Stoicism’s revival” called Life Lessons from Ancient Greece, which quoted me on the links between Stoicism and modern cognitive-behavioural therapy.

Many modern stoics argue that this doctrine has already been partially revived in the form of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), the “problem-focused” therapy now widely seen as psychology’s best weapon against depression, anxiety and every kind of unhelpful thinking. Like stoicism, CBT encourages practitioners to distinguish between events and perceptions, and nearly every CBT textbook contains some version of Epictetus’s dictum: “Men are disturbed not by things, but the views they take of them.” Yet although the founders of CBT openly acknowledged the influence of stoicism, they tended to adopt the techniques without reference to the wider moral framework. “Stoicism transcends most modern self-help and therapy by offering the view that much of our emotional suffering is caused by false values, such as egotism, materialism or hedonism,” says Donald Robertson, a cognitive-behavioural psychotherapist who is one of the organisers of Stoic Week. — Rowland Manthorpe in The Economist

Another good source of information is Modern Stoicism, a nonprofit organization run by a multi-disciplinary team of volunteers who carry out research on Stoicism and disseminate information on its application to modern-day living. Modern Stoicism run the annual Stoicon conference and multiple Stoicon-x mini conferences in different cities around the world. They also run the annual Stoic Week online course, in which over eight thousand people took part last year. The figures from these events show that Stoicism is continuing to experience a revival and it’s often among entrepreneurs and leaders in business that it’s catching on the most.

The Leadership Qualities of a Stoic EmperorMany of the articles above discuss ways in which the basic concepts and practices of ancient Stoicism can be of benefit in the work environment today. However, I’ve also tried exploring the relevance of Stoicism from a rather different perspective by looking at the qualities of a good ruler which Marcus Aurelius sought to learn from his adoptive father and predecessor the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius.

We can summarize advice based on the leadership qualities Marcus admired as follows:

Get along with other people

Be hardworking and conscientious

Don’t seek praise or flatter others

Don’t be afraid of criticism

Be content with the simple things in life

You can read more about how Marcus defined those qualities as exemplified by the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius in my previous Medium article on the subject. They’re all consistent with the teachings of Stoicism, although Antoninus Pius himself doesn’t appear to have been a Stoic.

November 9, 2023

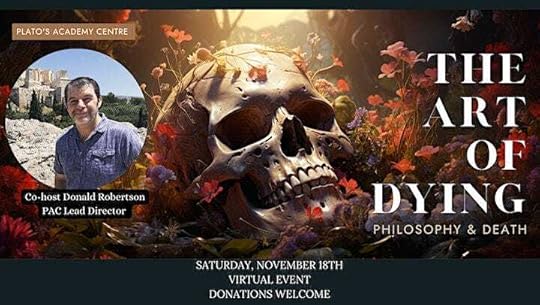

Why should you care about philosophy and death?

I wanted to write a personal invitation for those of you who haven’t already to register for our forthcoming virtual conference. Come and join us on Sat 18th Nov to contemplate mortality at: The Art of Dying: Philosophy and Death. We organize a lot of events through — about four or five per year, now with approx a thousand attendees at each event! — but this was one that I was personally really interested in making happen. I think our relationship with our own mortality has to lie at the centre of any truly profound philosophy of life. It’s one of the major themes of Stoicism and, indeed, of ancient philosophy in general.

Register for Philosophy and Death

Please come along and join us. It’s completely free of charge, as always. (Donations are gratefully received as they help us to continue our work, providing you and others with these events, etc.) Please don’t worry if you’re in another time zone, or can’t make it — most of our attendees watch the playback of the event. Videos will be available to everyone who registers in advance.

I’m going to say a bit more below about the event but first I wanted to mention that as Plato’s Academy Centre grows, we wanted to ensure that we were giving something back to Greece. So we have now partnered with another nonprofit called The Hellenic Initiative, in order to donate a portion of our revenue to support their work in providing crisis relief and also promoting young entrepreneurs throughout Greece. Greece has suffered in recent decades due to economic difficulties and recent floods and wildfires. We love Greek philosophy and wanted to give something back and we’re pleased, although it’s a small initial step, to now be able to do so with your help.

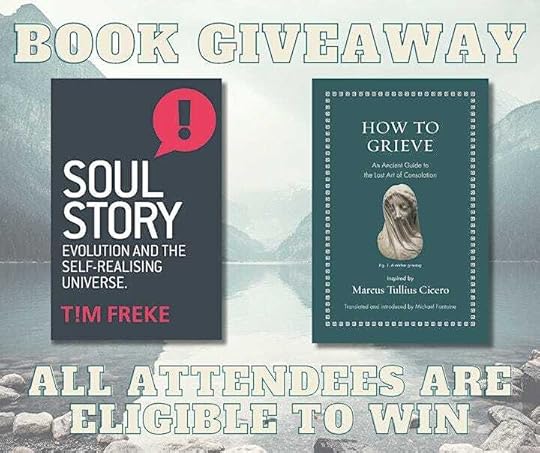

My wife, Kasey, is now on maternity leave, because she’s due to give birth in a matter of days. She’s done a fantastic job in organizing this event. Kasey has been working closely with a number of major publishers on this and other events, and has arranged many benefits for friends of , including the opportunity for anyone who registers in advance for Philosophy and Death to win a copy either of Tim Freke’s Soul Story or Michael Fontaine’s How to Grieve — books by two of the speakers from the event.

I’ve been working for a few years on a major research proposal (it’s a bit hush-hush at the moment) on the psychology of death contemplation. So I’m also fascinated to hear what our speakers have to say, which might be of benefit in helping people through these methods, as we believe there may be significant, measurable, psychological benefits to these sort of practices. I hope to be able to update you all soon with more information on that front!

Who are the speakers?“Cicero on Grieving the Death of a Child”, Michael Fontaine, author of How to Grieve: An Ancient Guide to the Lost Art of Consolation

"Accepting death: The key to psychological equanimity", Dr. Rachel Menzies, author of Mortals: How the Fear of Death Shaped Human Society

"Grief in Ancient Philosophy: Stoic Self-sufficiency or Aristotelian Interdependence?", Prof. Michael Cholbi, Executive Director of the International Association for the Philosophy of Death and Dying and author of Grief: A Philosophical Guide

"Seneca and the Shortness of Life", Tim LeBon, author of 365 Ways to Be More Stoic

"Forays to Face Finitude: Stoic contemplation, communitas, & creative action", Dr. Kate Hammer, existential psychotherapist, author of Joyful Stoic Death Writing, and Kathryn Koromilas, creator of the 28 Days of Joyful Death Writing with the Stoics programme

"Socrates: Fearless in the Face of Death", Dr. Scott Waltman, author of Socratic Questioning for Therapists and Counselors and The Stoicism Workbook

"A Thousand Little Deaths: Lucretius on Death and Change", Shaun Stevenson Lecturer in Philosophy at Manchester Metropolitan University and author of forthcoming Positively Dead: Exploring Death in Deleuze

"The Evolution of Immortality" , Timothy Freke, author of The Jesus Mysteries and Soul Story

I will be hosting with my good friend, Anya Leonard, the founder and director of the Classical Wisdom website.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

November 5, 2023

Register today for Stoic Week 2023

Hello everyone,

I wanted to let you know that Modern Stoicism are running our hugely successful Stoic Week online course again this year. It’s completely free of charge and starts on Monday 6th Nov. I designed the original version but this year it’s being run by Tim LeBon and Eve Riches. At a rough estimate, we think over 25,000 people have completed Stoic Week since it began, around ten years ago.

When people ask me what the best way is to get started practising Stoicism, I usually say: DO STOIC WEEK! But it only runs once per year, so don’t miss your chance!

You will learn about how the ancient philosophy of Stoicism can be adapted to help us lead better lives. The course combines general theory with more specific, step-by-step guidance on certain Stoic exercises. These materials have been prepared by experts in the field and give you an unusual and completely free-of-charge opportunity for personal development.