Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 25

October 31, 2023

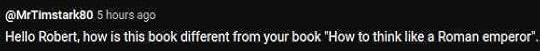

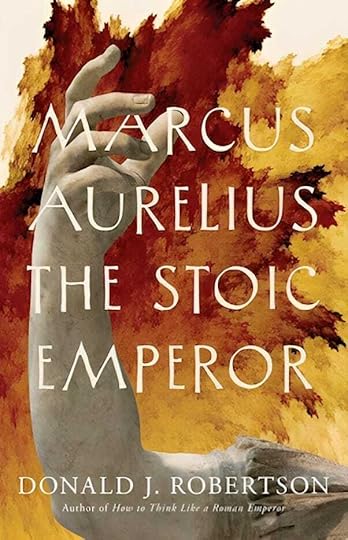

What Makes Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor Different

Several people have asked me how my new book Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor (Yales) is different from How to Think Like a Roman Emperor (St Martin’s). I’ve written three books in row about Marcus Aurelius and they’re all very different. (The other one, Verissimus, is a graphic novel about his life.)

In a nutshell, Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor is a biography with a bit of philosophy and self-improvement advice; How to Think Like a Roman Emperor is a self-help book with a bit of philosophy and some biographical vignettes. Personally, I view them as very different books. I’ll try to explain some of the other differences below. By the way, Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor is already available to order in advance from Amazon and all other good booksellers. Please consider pre-ordering now if you’re interested as not only will you potentially benefit from Amazon’s pre-order price guarantee but by placing an advance order you help us get the book into more stores!

My hunch is that after reading How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, people will get a lot more out of Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor because it’s intended to help them put themselves much more into Marcus’ shoes, and immerse themselves in his world.

The biographical vignettes in How to Think Like a Roman Emperor are mainly intended to illustrate some of the philosophical and psychological points being made. Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor was written from a different perspective, with the goal of helping you to really get to know Marcus, in a more rounded way, as a human being. There’s also far more historical context, which is designed to help you deepen your understanding of Marcus’ character and actions.

There is a lot of Stoic philosophy in Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor. In fact, it contains about 100 references to the Meditations. The focus, though, is on how these help to explain Marcus’ character and actions as emperor, and his personal psychological journey. While I was writing the book, I also kept in mind that many readers would be looking for some self-improvement takeaways. So although this is not primarily a self-help book, I think there are general self-improvement themes which pervade the story, and which I hope readers will notice and take away. These may be subtle at times but I also think they can be more powerful for some readers because they’re more closely entwined with the story of Marcus’ life and the struggles he overcame.

The main self-improvement theme that I think we can observe in Marcus’ life is how he learned to master his own temper, and cope with anger. I believe that’s the most important area of self-help for most people today. Indeed, I like to say that anger is the royal road to self-improvement — or rather learning to overcome our anger is. You may notice that I say quite a lot about how Hadrian influenced Marcus. I believe that Emperor Hadrian, his adoptive grandfather, was, in a sense, as much of an influence on Marcus’ character as Emperor Antoninus, his adoptive father, was. Hadrian is barely mentioned in the Meditations, though, because his influence was that of a negative role-model — Marcus learned from him what not to do.

Description

DescriptionAdd this title to your Goodreads bookshelf.

This novel biography brings Marcus Aurelius (121–180 CE) to life for a new generation of readers by exploring the emperor’s fascinating psychological journey. Donald J. Robertson examines Marcus’s relationships with key figures in his life, such as his mother, Domitia Lucilla, and the emperor Hadrian, as well as his Stoic tutors. He draws extensively on Marcus’s own Meditations and correspondence, and he examines the emperor’s actions as detailed in the Augustan History and other ancient texts.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Marcus Aurelius struggled to reconcile his philosophy and moral values with the political pressures he faced as emperor at the height of Roman power. Robertson examines Marcus’s attitude toward slavery and the moral dilemma posed by capturing enemies in warfare; his attitude toward women; the role of Stoicism in shaping his response to the threat of civil war; the treatment of Christians under his rule; and the naming of his notorious son Commodus as his successor.

Throughout, the Meditations is used to shed light on the mind of the emperor—his character, values, and motives—as Robertson skillfully weaves together Marcus’s inner journey as a philosopher with the outer events of his life as a Roman emperor.

Table of ContentsPrologue: Truth in the Meditations

Chapter One. The Mother of Caesar

Chapter Two. Verissimus the Philosopher

Chapter Three. The Greek Training

Chapter Four. Hadrian’s Vendettas

Chapter Five. The Death of Hadrian

Chapter Six. Disciple of Antoninus

Chapter Seven. Disciple of Rusticus

Chapter Eight. The Two Emperors

Chapter Nine. The Parthian Invasion

Chapter Ten. The War of Lucius Verus

Chapter Eleven. Parthicus Maximus

Chapter Twelve. The Antonine Plague

Chapter Thirteen. The War of Many Nations

Chapter Fourteen. Germanicus

Chapter Fifteen. Sarmaticus

Chapter Sixteen. Cassius the Usurper

Chapter Seventeen. The Civil War

Chapter Eighteen. The Setting Sun

Epilogue: The Hall of Mysteries

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 30, 2023

The Stoic Virtues and Code of Honor

Something about the chivalric codes of the Middle Ages seems curiously akin to the ethical ideals of Stoicism. Ancient Stoic philosophy didn’t have an explicit code of honor, as far as we know. However, according to the doxographer Stobaeus, the Stoics maintained that the goal of their philosophy, “living in agreement with nature”, was synonymous with “living honorably”. Moreover, a basic code of honorable conduct is clearly implicit in the surviving writings of Seneca, Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius, and our other sources for the philosophy.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Stoics liked to have lists that could be easily committed to memory. Most obviously, there is their list of four cardinal virtues, which goes back at least as far as the portrayal of Socrates in the dialogues of Plato: Wisdom (sophia), Righteousness (dikaiosune), Fortitude (andreia), and Temperance (sophrosune); or Wisdom, Justice, Courage, and Moderation, in more modern language. These virtues came to be represented by four corresponding animals in the traditional symbol known as the tetramorph: the man of wisdom, eagle of justice, lion of fortitude, and ox or bull of temperance.

The Christian tetramorph: man, eagle, lion, bull

The Christian tetramorph: man, eagle, lion, bullThe doxographer Diogenes Laertius said that the Stoics described the supreme good as “honorable” because it consists of these four factors required for the perfection of human nature: the virtues of wisdom, justice, courage, and, as he writes, orderliness (self-discipline or moderation). The “honorable”, he says, denotes those qualities which make their possessor genuinely praiseworthy, by allowing him to fulfil his natural potential as a human being. The Stoics concluded therefore that the wise man alone is honorable and “that only the honorable is good”. The good and the honorable are synonymous, in other words. However, the good is also that which is beneficial. The Stoics believed that doing what is honorable is in our own best interests because it allows us to flourish as human beings.

We might briefly summarize the Stoic code of honor described below as follows:

Love the truth and seek wisdom

Act with justice, fairness, and kindness toward others

Master your fears and be courageous

Master your desires and live with self-discipline

In addition to this fourfold scheme, some of the Stoics also refer to a threefold rule of life, which Epictetus describes as the distinction between the Discipline of Assent, the Discipline of Action, and the Discipline of Desire and Aversion. It’s easy to combine these threefold and fourfold models, though, as shown below. The Stoics regarded courage and moderation as two aspects of the discipline required to live consistently in accord with wisdom and justice, by mastering our fears and desires. We can see that in the famous slogan attributed to Epictetus: endure and renounce. Endure our fears, through courage, and renounce our desires, by exercising moderation — the Discipline of Desire and Aversion.

The four cardinal virtues, and examples of Stoic indifferents

The four cardinal virtues, and examples of Stoic indifferentsZeno, the founder of Stoicism, defined the supreme goal as a “smoothly flowing life”, or “living in agreement with Nature”. For the Stoics this came to mean living consistently and in harmony with our own nature, as rational beings, with the rest of mankind, and with Nature as a whole, particularly the external events that befall us in life. For example, Marcus Aurelius uses this threefold model to express the basic Stoic code of conduct throughout The Meditations.

Every nature is contented when things go well for it; and things go well for a rational nature when it [1:] never gives its assent to a false or doubtful impression, and [2:] directs its impulses only to actions that further the common good, and [3a:] limits its desires and aversions only to things that are within its power, and [3b:] welcomes all that is assigned to it by universal nature. (Meditations, 8.7)

Likewise,

It is sufficient that [1:] your present judgement should grasp its object, that [2:] your present action should be directed to the common good, that [3:] your present disposition should be well satisfied with all that happens to it from a cause outside itself. (Meditations, 9.6)

Marcus attributes these ideas to Epictetus:

No one can rob us of our free will, said Epictetus. He said too that [1:] we ‘must find an art of assent, and [2:] in the sphere of our impulses, take good care that they are exercised subject to the “reserve clause”, and that they take account of the common interest, and that they are proportionate to the worth of their object; and [3a:] we should abstain wholly from immoderate desire, and [3b:] not try to avoid anything that is not subject to our control’. (Meditations, 11.36–37)

Equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius1. The Discipline of Assent — Stoic MindfulnessThe Virtue of Wisdom: Love the Truth

Equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius1. The Discipline of Assent — Stoic MindfulnessThe Virtue of Wisdom: Love the TruthThe very word philosophy literally means “love of wisdom”, which entails the love of truth. Socrates taught that genuine wisdom consists in grasping the truth about the most important things in life. For Stoics, wisdom therefore consists in our ability to grasp the nature of the supreme good, i.e., the goal of life. Put differently, it’s the knowledge of what is good, bad, and indifferent. You can therefore also describe wisdom as the ability to know what helps us flourish and achieve fulfillment (eudaimonia) in life, or what harms us in that regard. The Stoics use the word prosoche (attention) to describe the practice of continual mindfulness regarding our ruling faculty and its use of judgements in daily life, especially the way our value judgements shape our desires and emotions. Wisdom requires “Stoic mindfulness”, in other words.

However, the virtue of wisdom, and therefore Stoic honor, is also associated with the ability to be scrupulously honest both with oneself and others. Wisdom can’t exist alongside self-deception and justice can’t exist as long as we’re deceiving others. Wisdom is the ability to grasp the truth about the most important things in life, to perceive its implications for daily life, and to communicate as clearly as possible on that basis. Epictetus calls this the Discipline of Assent. We should avoid giving our assent to impressions that are false. Rather we must firmly grasp hold of certain basic truths such as those concerning the nature of the supreme good in life, i.e., that it consists of wisdom and virtue.

In the 19th century, Gautier summarized the Ten Commandments of medieval European chivalry. We can compare his code of honor with the four Stoic virtues and three disciplines. However, chivalry was wedded to Christianity so instead of loving philosophical truth and wisdom, Gautier’s equivalent would be the more doctrinaire: “Thou shalt believe all that the Church teaches and thou shalt observe all its directions.” Yet Christian knights are expected to embrace truth and honesty just like the Stoic code: “Thou shalt never lie, and shalt remain faithful to thy pledged word.” A Stoic code of honor would therefore require being ruthlessly honest with yourself and not deceiving others — Stoics also avoid jumping to conclusions rashly in areas where the truth is uncertain. The virtue of wisdom is traditionally symbolized in the tetramorph by the image of a man.

2. The Discipline of Action — Stoic PhilanthropyJustice: Seek to Help Others, Fate PermittingWisdom applied to our actions leads to the virtue of justice, although in Stoicism this is a broad concept which could better be described in more general terms as social virtue. Marcus Aurelius constantly reminds himself that his actions should be dedicated to the fundamental goal of life, the attainment of wisdom and virtue. However, the virtue of justice must also aim at an external outcome and for Stoics that is the common welfare of mankind. Everything a Stoic does should contribute, in some small way, to benefiting humanity, or at least not do the opposite. We might describe this as “Stoic philanthropy” or brotherly love.

However, as other people are externals, beyond our direct control, Stoics have to pursue their welfare with the caveat “Fate permitting” — known as the Stoic “reserve clause” (hupexairesis). Cicero explained this through the famous metaphor of the archer. He can take aim at a target and fire his arrow skilfully but once it has flown from the bow, whether or not it hits the target is in the hands of fate. He takes aim to the best of his ability but accepts that the target could move, for instance, and accepts either success or failure with emotional equanimity.

Marcus says that the Discipline of Action is threefold. It requires acting for the common welfare of mankind, with the caveat “Fate permitting”, but also using reason to judge the relative value (axia) of different outcomes in order to determine the most appropriate course of action. The Stoic virtue of justice consists of two main qualities: kindness and fairness.

Kindness is simply the opposite of anger, according to the Stoics. Anger typically consists in the desire to harm others because of some perceived injury, the desire for vengeance. Kindness, by contrast, is the desire to help others. We help others, even our “enemies”, by educating them and bringing them closer to wisdom. However, the Stoics recognize that it’s natural to “prefer” certain external advantages in life, such as health, wealth, and reputation, so long as they’re only desired within reasonable bounds and not excessively. That means, though, that we must exercise judgment to rationally determine in each case the difference between having enough sleep, for instance, and having too much.

Gautier’s chivalric code requires medieval knights to defend their nation and the Christian community: “Thou shalt defend the Church”, “Thou shalt love the country in which thou wast born.” However, it also requires knights to pledge their lives to protecting the poor and the weak: “Thou shalt respect all weaknesses, and shalt constitute thyself the defender of them”, “Thou shalt be generous, and give largesse to everyone”, “Thou shalt be everywhere and always the champion of the Right and the Good against Injustice and Evil.” Stoics likewise dedicate their lives to acting wisely and with the social virtues of justice, fairness, and kindness, acting for the common welfare of mankind, Fate willing, i.e., while accepting that the outcome is not directly under their control. The virtue of justice is symbolized in the tetramorph by the image of an eagle.

Cato of Utica in Dante’s Purgatory, by Gustav Dore3. The Discipline of Desire and Aversion — Stoic Acceptance

Cato of Utica in Dante’s Purgatory, by Gustav Dore3. The Discipline of Desire and Aversion — Stoic AcceptanceSeek not for events to happen as you wish but wish events to happen as they do and your life will go smoothly. — Handbook

The last two virtues are closely-related and can be viewed as the twin virtues of self-mastery. Epictetus combines them in his slogan “endure and renounce” (or “bear and forbear”). Epictetus believed that novice Stoics should begin their training by focusing on these virtues. We can call this “Stoic acceptance” because it requires a kind of resignation to external events, beyond our direct control, that the majority of people struggle against, seeking to change or avoid. The Stoics famously used the metaphor of a dog tied to a cart to illustrate this. The fool is like a dog who tries to sit down or run in the opposite direction but is dragged along roughly by its leash anyway. The wise man is like the dog who keeps pace with the cart, for whom things go smoothly because he accepts and adapts to his fate.

a. Courage: Endurance in the Service of Wisdom and JusticeWith courage and endurance we face our fears and patiently bear unpleasant feelings, such as hunger and fatigue, and even pain. The Stoics constantly remind themselves of the paradox that our fear does us more harm than the things of which we’re afraid. However, the majority of people tend to confuse recklessness with courage. Courage without wisdom, as Socrates pointed out, though, is not a virtue — it’s just reckless or foolhardy. Even criminals act fearlessly, or endure pain and discomfort, but they do so in the pursuit of base and vicious goals.

Gautier’s chivalric code requires knights to show courage: “Thou shalt not recoil before thine enemy.” Stoics likewise view pain with relative indifference and are willing to face things feared by the majority of people, in the service of wisdom and justice. The virtue of courage is symbolized in the tetramorph by the image of a lion.

b. Moderation: Sacrifice in the Service of Wisdom and JusticeThrough the virtue of moderation or temperance, we limit our desires to what reason determines to be appropriate under the circumstances, renouncing excess and forbearing from over-indulgence. As the famous maxim of the Delphic Oracle said: “nothing in excess” — all things in moderation. However, the majority of people, again, tend to confuse the appearance of self-discipline with the real thing. Vain and greedy individuals often exercise self-discipline in one area of their lives in order to indulge themselves in others.

Gautier’s version of the chivalric code requires Christian knights to fulfil their duties in a conscientious and disciplined manner: “Thou shalt perform scrupulously thy feudal duties, if they be not contrary to the laws of God.” Stoics view pleasure with relative indifference and are therefore willing to forego things desired by the majority of people, living in a self-disciplined manner in the service of wisdom and justice. The virtue of temperance is symbolized in the tetramorph by the image of an ox or bull.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 26, 2023

Excerpt from "Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor"

In this episode, I read an exclusive excerpt from my latest book, Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor, published by Yale University Press, as part of the Ancient Lives Series. The book is a philosophical biography of the Roman emperor, which contains many references to the Meditations and how his philosophy shaped his life. You can help it reach a wider audience by pre-ordering now from Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or any other bookseller.

Marcus Aurelius did not have a heart of stone. When the news was brought to him that one of his most beloved tutors had died, the young Caesar was distraught, and tears poured down his cheeks—he may perhaps have started to beat his chest and tear his clothes in grief. Palace servants, afraid his reputation would be harmed by such a public display of raw emotion, rushed to his side, trying to restrain him. His adoptive father, the emperor Antoninus Pius, a thoughtful and gentle man, gestured for them to step aside. He whispered, “Let him be only a man for once; for neither philosophy nor empire takes away natural feeling.”

Praise from other Authors

Praise from other Authors“Few historical figures are as fascinating as Marcus Aurelius, the emperor-philosopher. And few writers have been so effective at bringing his complex life and character to the attention of modern readers as Donald Robertson.”—Massimo Pigliucci, author of How to Be a Stoic: Using Ancient Philosophy to Live a Modern Life

“Robertson has written a very thorough and very readable account of Marcus’s life and the events and people that shaped him. Anyone who wants to understand the author of Meditations should read this book.”—Robin Waterfield, author of Marcus Aurelius, Meditations: The Annotated Edition

“Donald Robertson guides us into the world of a philosopher-emperor whose humility and Stoic teachings fill the pages. We are indebted to Robertson for this wonderful account of the emperor who penned notes to himself while in battle that would be later known as the Meditations and read by millions for philosophical inspiration. Simply spellbinding.”—Nancy Sherman, author of Stoic Wisdom: Ancient Lessons for Modern Resilience

“This highly readable biography is the perfect place to begin for anyone who wants to learn more about the man behind the Meditations.”—John Sellars, author of The Pocket Stoic

“Robertson’s biography provides a compelling narrative of Marcus’ life, carefully based on the primary sources. He brings out very clearly the life-long significance of Stoicism for Marcus and the interplay between philosophy, politics, and warfare.”—Christopher Gill, author of Learning to Live Naturally: Stoic Ethics and Its Modern Significance

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 24, 2023

Exclusive Excerpt from "Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor"

Exclusively for you, my Substack subscribers! Below you can read an excerpt from the beginning of my latest book, Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor, which is part of the Yale University Press Ancient Lives series.

It is due out in Feb 2024 but you can help it reach more people by pre-ordering your copy. Ebook and audiobook (narrated by me) editions will be forthcoming. Please get your copy today from Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or other retailers via the publisher’s website. Thanks for your support!

Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic EmperorExclusive Excerpt

Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic EmperorExclusive ExcerptMost of us, of course, are interested in Marcus because of the famous book attributed to him. The Meditations has become one of the most cherished self-improvement classics of all time. It has had a profound influence on many different individuals throughout history. Modern appreciation of it began when the first printed edition of the Greek manuscript was published in 1558, bearing the title “To himself” (Ta eis heauton), along with a Latin translation. In 1634, the first English translation appeared under the title Marcus Aurelius Antoninus the Roman Emperor, his Meditations Concerning Himself. The use of this term eventually stuck and it is now common to abbreviate the title simply to the Meditations.

Marcus tells himself that nothing can prevent him from living in agreement with nature, although he often struggled to do so in practice.

So what are the core teachings “to himself” described in the Meditations? First of all, the Stoics defined humanity’s supreme goal as “living in agreement with nature”. Although Marcus only uses the word “Stoic” once, he often uses this slogan. He gives thanks that his tutors provided him with frequent examples of what “living in agreement with nature” meant in practice, in their daily lives. He also tells himself that nothing can prevent him from living in agreement with nature, just like they did, although he often struggled to do so in practice.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

“In agreement with nature”, for the Stoics, meant rationally because they considered reason to be the highest human faculty. If we lived consistently in accord with reason, we would perfect our nature and attain the virtue of wisdom. If we apply such wisdom in our relationships with others, treating them honestly and fairly, we achieve the social virtue of justice. In order to live more fully in accord with wisdom and justice, though, we need to master any fears and desires that threaten to lead us astray. That calls for courage and moderation, giving us the four “cardinal virtues” of ancient Stoicism: wisdom, justice, fortitude, and temperance. The Stoic goal of life can also be understood, in this sense, as “living in accord with virtue”, as long as we bear in mind that all the virtues are taken by them to be forms of moral wisdom.

Although the wise are not highly perturbed by misfortune, neither are they completely unfeeling. Marcus, as we’ve seen, could be described as quite a sensitive man. He gradually trained himself to manage his emotions better, by examining them rationally rather than merely suppressing them. Stoicism taught him to view external events, i.e., events beyond our direct control, as of secondary importance. Marcus thereby learned a kind of psychological therapy, designed to free him from unhealthy passions, a state of mind called apatheia by the Stoics. Almost everything he says about philosophy can be related back to this basic goal of living in agreement with Nature, free from unhealthy emotions. This book includes over a hundred such references to the Meditations, which have been carefully interspersed in order to highlight various connections between Marcus’ Stoic principles and the events of his life.

Who was Marcus, though? Many today came to know him through his portrayal by Richard Harris in the movie Gladiator (2000) and a few may recall Alec Guinness in The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964) – these are only very loosely based on history. Sometimes people assume that we know little or nothing about the facts of Marcus’ life. Fortunately, that is not the case. Indeed, we know more about him than about any other Stoic, or most other ancient philosophers. Three main Roman histories survive that describe his life and character: the Historia Romana of Cassius Dio, Herodian’s History of the Empire from the Death of Marcus, and the Historia Augusta. We also possess a cache of private letters between Marcus and his rhetoric tutor, which give us an exceptional insight into his private life as Caesar, and later as emperor.

Experts Praise the Book

Experts Praise the Book“Few historical figures are as fascinating as Marcus Aurelius, the emperor-philosopher. And few writers have been so effective at bringing his complex life and character to the attention of modern readers as Donald Robertson.”—Massimo Pigliucci, author of How to Be a Stoic: Using Ancient Philosophy to Live a Modern Life

“Robertson has written a very thorough and very readable account of Marcus’s life and the events and people that shaped him. Anyone who wants to understand the author of Meditations should read this book.”—Robin Waterfield, author of Marcus Aurelius, Meditations: The Annotated Edition

“Donald Robertson guides us into the world of a philosopher-emperor whose humility and Stoic teachings fill the pages. We are indebted to Robertson for this wonderful account of the emperor who penned notes to himself while in battle that would be later known as the Meditations and read by millions for philosophical inspiration. Simply spellbinding.”—Nancy Sherman, author of Stoic Wisdom: Ancient Lessons for Modern Resilience

“This highly readable biography is the perfect place to begin for anyone who wants to learn more about the man behind the Meditations.”—John Sellars, author of Marcus Aurelius (Philosophy in the Roman World)

“Robertson’s biography provides a compelling narrative of Marcus’ life, carefully based on the primary sources. He brings out very clearly the life-long significance of Stoicism for Marcus and the interplay between philosophy, politics, and warfare.”—Christopher Gill, author of Marcus Aurelius: Meditations, Books 1-6

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 20, 2023

The metaphor of the ship

CommentaryJust as on a voyage, when your ship has anchored, if you should go on shore to get fresh water, you may pick up a small shellfish or little bulb on the way, but you have to keep your attention fixed on the ship, and turn about frequently for fear lest the captain should call; and if he calls, you must give up all these things, if you would escape being thrown on board all tied up like the sheep. So it is also in life: If there be given you, instead of a little bulb and a small shell-fish, a little wife and child, there will be no objection to that; only, if the Captain calls, give up all these things and run to the ship, without even turning around to look back. And if you are an old man, never even get very far away from the ship, for fear that when He calls you may be missing.

The metaphor of sailing a ship is common in Greek philosophy but it undoubtedly had special significance for the Stoics.

The metaphor of sailing a ship is common in Greek philosophy but it undoubtedly had special significance for the Stoics. Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, was a member of a race of seafaring merchants called the Phoenicians, who were renowned for trading purple dye derived from the murex sea snail. He reputedly lost his fortune in a shipwreck and was washed ashore near Athens, where he studied philosophy and later founded the Stoic school.

October 19, 2023

Socrates and Love

In this episode, I speak about Socrates with Armand D'Angour, professor of classics at Oxford University. He is the translator of How to Innovate: An Ancient Guide to Creative Thinking (2021) and the author of Socrates in Love: The Making of a Philosopher (2020), among other works.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

HighlightsWhy should we care about Socrates today?

How reliable are our sources regarding Socrates?

What was Socrates like as a young man?

How do you imagine his relationship with Pericles and Aspasia?

Why did Socrates love Alcibiades so much?

Did Socrates have a mental illness?

Why was Socrates executed?

Links

LinksSocrates in Love: The Making of a Philosopher

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 17, 2023

Stoicism at the Dentist

I’ve just come home from the dentist so I thought I’d write a short article while the experience is still fresh in my mind. I always use psychological techniques to help me cope with the pain and discomfort of dental procedures. Today’s appointment was for something pretty minor but I still found it helpful to use Stoicism and some cognitive therapy to manage my discomfort.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

There are lots of different strategies you can use to cope with pain. They fall into two main categories, which I would call distraction and acceptance. Generally speaking, acceptance strategies are going to work out better for most people long term, for chronic pain. For acute pain, like medical or dental procedures, though, distraction techniques are fine. Nevertheless, I prefer to use acceptance-based techniques at the dentist because I think it helps me to learn better general-purpose skills.

There are lots of effective distraction techniques. For example, I will often clench one fist, or squeeze my index finger and thumb together, and really try to concentrate on that sensation for a short while if I want to distract myself from a painful injection or something. Typically, I’ll combine doing this with acceptance techniques.

Photo by Colourblind Kevin on Unsplash

Photo by Colourblind Kevin on UnsplashI’ll cut to the chase and say that my favorite acceptance-based strategy is to try to imagine both the absence of pain and its presence simultaneously. How do you do that? Well, it’s a bit of a knack, because it seems like a paradoxical idea at first. However, like most paradoxes, it’s actually common sense once you grasp the basic concept. For instance, as long as you view pain as temporary and focus on its transience, you must be thinking that until now it did not exist, it will only exist for a split-second, and then forever it will cease to exist again. Being aware of something’s transience means accepting its presence, here and now, while also contemplating its non-existence in the past and future.

As you can see, the trick to most acceptance-based strategies is that you continue to be aware of something, even though it is painful or unpleasant, but you do so from a different perspective. In this case, what’s changed is that you’re also aware of the impending non-existence of the sensation and perhaps also its non-existence in the past. Sometimes I also just think of the infinite realm of unknown experiences that lie beyond the present moment. Again, that’s simply like telling yourself “There’s so much more than this!” I might also say to myself “This is only a split-second, and then it’s gone forever… in an hour it will still be gone… tomorrow it will still be gone… in a month it will still be gone… in a year it will still be gone… and a hundred years from now, after I am gone, it will still be gone forever…” The key, I think, is to imagine the absence of the sensation while accepting its presence, which mostly comes from thinking of it as fleeting.

Another strategy that I often use is to stop responding to a sensation altogether, while accepting it with indifference, as neither good nor bad. This feels a bit like training yourself to just stare blankly at something, and do nothing. The specific technique I use is to count, in my imagination, backwards from one hundred, while imagining that my voice is becoming weaker and its requiring more effort with each number. So normally, by the time I’ve counted just a few numbers — from 100 to 95 let’s say — my mind has become sort-of blank. That helps me accept the pain or discomfort and adopt a neutral attitude toward it, which I like to call studied indifference. It doesn’t bother me but I’m also not trying to avoid experiencing it.

“He who knows how to suffer suffers less.” — Paul Dubois

All of these strategies are meant to be done in such a way as to prevent the fear of pain. Acceptance, if you like, means avoidance of avoidance. That’s the biggest pitfall of pain management, basically. You have to be careful that you’re not trying to run away from pain. Adopting a fearful or avoidant attitude can become a habit, which can lead to more problems in the future. That’s why we try to frame these strategies as forms of acceptance. They’re not ways of escaping pain but ways of looking at it differently, so that it doesn’t appear as disturbing any more. The goal is to learn to view pain as “just a sensation”, which you no longer need to worry about or avoid. As the Stoic-influenced psychotherapist, Paul Dubois, once said: “He who knows how to suffer suffers less.”

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 15, 2023

Distortion Spotting Exercise

Have you noticed that other people often exhibit quite biased thinking? Angry people seem to be looking for more reasons to become enraged. Anxious people seem at times to exaggerate the dangers they face. Depressed people seem to view everything in an overly-negative way, and not to be able to see the positives. The worst thing is that they don’t seem to realize they’re doing it! What if I told you that you probably do this as well? We all exhibit biases in our thinking sometimes but we don’t notice because, well, because we’re biased.

There are things we can do to address this problem, though. One of the fundamental techniques of cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), involves learning to spot biases in your own thinking — we call these “cognitive distortions” in research or just “thinking errors” when speaking informally. You can view the list of cognitive distortions I’m going to give you below as consisting of various labels for common biases that we all exhibit from time to time in our thinking.

The central premise of all cognitive therapy is what we could call the cognitive model of emotion, which simply means that our beliefs shape our emotions a lot more than we normally assume. It’s often explained by quoting the Stoic Handbook of Epictetus: “It’s not events that upset us but rather our opinions about them.” Cognitive therapy therefore sets out to identify errors in our reasoning, and to correct them using a form of Socratic questioning. The therapist isn’t really correcting the client’s thinking errors by asking these questions. Rather the client is helped to learn how to identify and correct his or her own errors. They are encouraged to continue doing this between sessions, and even, to some extent, after the therapy has ended.

Photo by Emiliano Vittoriosi on Unsplash

Photo by Emiliano Vittoriosi on UnsplashIn the first book he wrote on psychotherapy, Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders (1976), for instance, Aaron T. Beck, said:

This new approach—cognitive therapy—suggests that the individual’s problems are derived largely from certain distortions of reality based on erroneous premises and assumptions. […] Regardless of their origin, it is relatively simple to state the formula for treatment: The therapist helps a patient to unravel his distortions in thinking and to learn alternative, more realistic ways to formulate his experiences. — Beck, 1976, p. 2, italics added

Cognitive therapy has many different techniques. The one we’re going to explain in this article is called spotting thinking errors. We can identify common types of faulty reasoning, similar to logical fallacies, which research shows are associated with emotional problems, such as severe anxiety and depression.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Certain types of belief tend to be associated with certain problems. For example, people who suffer from severe anxiety tend to overestimate the severity and probability of certain perceived threats. People who have problems with anger tend to blame others severely for transgressing some moral rule, jump to conclusions about their motives, and often underestimate the risks associated with aggression. Depressed individuals often hold excessively negative beliefs about themselves, and have a negative bias toward life in general.

Just by noticing our thinking errors, and realizing that they are errors, we gain a more detached and objective perspective on our own thinking,

Learning to spot our own faulty reasoning and biases can be a very powerful way of helping ourselves. Just by noticing our thinking errors, and realizing that they are errors, we gain a more detached and objective perspective on our own thinking, which we sometimes call “cognitive distancing”. We now know that’s one of the simplest and most powerful processes in psychotherapy, and it can benefit you every day in self-improvement as well. In the next section, I’ll list some common thinking errors, and then we’ll look at several different exercises, which can help you to spot them, and gain cognitive distance.

What Thinking Errors?There are lots of lists of common thinking errors to be found in books on CBT. Different authors use different lists of errors, some may contain 4-5 types, others as many as twenty or more. Thinking errors typically overlap. Most people don’t experience all of them at once, though.

In his earliest book on psychotherapy, Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders, 1976, Beck lists four main categories of common cognitive distortions.

Extreme thinking, this encompasses many types of exaggeration such as what therapists call “catastrophizing”, which means overestimating the severity of a threat, or blowing things out of proportion. Beck also uses this term to refer to thinking in terms of polarized extremes, which we tend to call “black and white” or “all or nothing” thinking.

Selective abstraction, sometimes called “selective thinking” (a bit like “selective hearing” or “selective memory”), this refers to taking information out of context by ignoring, or possibly dismissing, relevant facts. It’s arguably quite fundamental, and perhaps underlies several other errors.

Arbitrary inference, this refers to jumping to conclusions prematurely, perhaps based on unfounded assumptions, or by making leaps such as “fortune telling”, in which we presume things about the future without sufficient evidence, or “mind reading”, in which we jump to conclusions about what other people are thinking.

Overgeneralization, this is another very common form of error, closely related to selective abstraction, in which we assume that something true in one context is true more generally, sometimes this can be called “always or never” thinking, and it’s also the basis of many stereotypes and prejudices.

As you can see, we can distinguish between different variations of most of these errors, and there are many others we can add to the list. There’s nothing to stop you from identifying others and choosing to work on those, if you want. It’s often helpful, though, to analyze your thinking in order to spot what the most prominent errors might be in your own emotions. Below are several exercises, which will help you work on your cognitive distortions in a variety of different ways.

Thinking of ExamplesClark and Beck (2011) suggest completing a worksheet in which you think of several examples of each thinking error. For instance, from your recent experience, particularly situations where you’ve struggled with your emotions, can you find several specific examples of each of the following:

Extreme thinking. Do you ever exaggerate anything or blow things out of proportion? Do you feel you sometimes view things too much in a black-and-white or all-or-nothing way? (Give some examples.)

Selective abstraction. Do you ever focus too much on some aspects of the situation and ignore others, as if you’re looking at events through a microscope or magnifying glass? Do you sometimes take certain events too much out of context? (Give some examples.)

Arbitrary inference. Do you ever jump prematurely to any conclusions about a situation? Do you ever make any mistaken assumptions about what others are thinking or how events will turn out in the future? (Give some examples.)

Overgeneralization. Do you ever find yourself making sweeping generalizations, such as telling yourself something is always or never the case? (Give some examples.)

As you can see, these questions are just a rough guide. Try your best to identify the sort of situations where you may be prone to making these or similar thinking errors. In the exercises below, you’re going to focus more narrowly on a specific situation and look at the thinking errors you may have exhibited, and how they may affect your emotions and behavior.

Analyzing a SituationA more common exercise in CBT would be to pick a recent time when you’ve experienced a problem, such as anxiety, and to ask yourself whether your thinking in that situation exhibited any of the thinking errors above.

What was the situation? Can you describe it in a few words? Where and when did it happen?

What emotions were you feeling at the time?

What thoughts were going through your mind?

What actions did you take in response? What did you actually do?

Spot thinking errors:

What, if anything, might have been too extreme about your thinking during that situation? Do you think you may have exaggerated anything?

What examples, if any, of selective thinking, taking things out of context, or overlooking details, might you identify on that occasion?

What conclusions, if any, did you jump to in that situation, without enough evidence?

What overgeneralizations, if any, might you have been making?

Once you’ve identified the sort of thinking errors that might be causing you the most problems, you can start keeping an eye out for them in general, using the next exercise.

Counting your ErrorsThis is really one of the easiest ways of applying cognitive therapy. If you can learn to keep a tally of your upsetting thoughts, that alone will often tend to reduce their frequency, intensity, and duration. For instance, Beck et al. 2005 describe counting automatic thoughts as a form of cognitive distancing.

Counting allows the patient to distance himself from his thoughts, gives him a sense of mastery over them, and helps him to recognize their automatic quality, rather than accepting them as an accurate reflection of external reality. — Beck et al., 2005, .p 195

There are several variations of this technique. For example, you could keep a written tally or use a tally counter, of the sort used by golfers and doormen.

Beck et al. mention these could be thoughts exhibiting specific types of cognitive distortion, such as catastrophizing. After noticing it, they advise accepting the thought rather than fighting and, and merely saying to yourself “There’s another fearful thought. I’ll just count it and let it go.” For instance, you might keep track of how many times each day you catch yourself exaggerating things, whether in your thoughts or speech, or how often, each day, you exhibit a negative bias in your thinking.

Often when people start doing an exercise like this, they notice an initial increase in the frequency of the troubling thoughts. That’s normal. Over the course of 2-3 days, though, if you’re consistent, you’ll usually find the thoughts occurring less often, and you’ll probably start to experience them as more boring, as if you’re viewing them from a more detached perspective.

Photo by Fallon Michael on UnsplashExercise: Spotting Distortions

Photo by Fallon Michael on UnsplashExercise: Spotting DistortionsThis exercise is longer and more in-depth so I’ve left it until last. You’ll gain more benefit from it if you’ve already completed some of the exercises above. You should already be more familiar with the idea of cognitive distortions and the experience of spotting them and gaining distance from them, by viewing them in a detached and objective manner.

Relax and focus on a specific situation where you’ve experienced anxiety, anger, or some other problem. If you can, imagine it as if it is happening right now. Your aim is to identify any problems or errors of thinking that might distort your perception of that situation. Fundamentally, you may find it becomes useful to evaluate whether your current viewpoint on the situation is 100% logical, accurate, and constructive, or whether you could potentially see things differently.

So, concerning the situation you’ve chosen:

What, if anything, might you be falsely presupposing about things?

What, if anything, might be distorted by your feelings?

What might you be dismissing or discounting unnecessarily?

What might you be looking at too much in all-or-nothing or black-and-white terms?

What might you be falsely assuming about other people?

What conclusions might you be jumping to about the future?

What false assumptions might you be making about yourself in regard to this matter?

What might you be making overgeneralizations about?

What, if anything, are you exaggerating?

What, if anything, are you trivialising?

What unreasonable demands, if any, might you be imposing upon yourself?

Are you placing any illogical demands on other people?

Are you imposing any irrational expectations on life?

What, if anything, might you be mistaken about?

What might you be ignoring or overlooking?

Who, if anyone, are you blaming excessively?

What, if anything, are you taking too personally?

What might you be misinterpreting about things?

What evidence is there that might contradict your view of the situation?

What might you be thinking about in an illogical way?

Are you contradicting yourself in any way?

What might be self-defeating or counter-productive about your attitude to things?

Are you unfairly labelling anything about yourself, others, or events?

Review QuestionsWhat have you learned from contemplating these questions?

What would be a more rational and helpful way of thinking about that situation?

What advice would you give someone else faced with a similar problem?

What else can be done now to begin changing things for the better?

What else do you have to report about the experience of doing this exercise?

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

ConclusionI hope you found those exercises of interest. Think of it a bit like going to the gym — don’t expect a miracle cure. In fact, the assumption that if you’re not cured immediately then it’s a waste of time, which we often find with depressed clients, but also in many other cases, is an example of one of the thinking errors we mentioned earlier: all-or-nothing thinking.

Please comment below with your thoughts, and particularly any examples of other types of common thinking errors you consider worth mentioning, or any interesting examples from your own life. Remember, that cognitive therapy techniques like these are about a kind of learning, so they usually take a little practice, and reflection.

October 12, 2023

Clarity and Wisdom

In this episode, I speak about Clarity and Wisdom with executive coach, Jim Vaselopulos. Jim is co-host of The Leadership Podcast. We discuss his new book, Clarity: Business Wisdom to Work Less and Achieve More.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

HighlightsWhat is clarity?

What's the relationship between wisdom and clarity?

What are the benefits of having more clarity?

What gets in the way of clarity?

How do we get clarity?

How do we help other people to get more clarity?

LinksThe Leadership Podcast website

The Leadership Podcast on Apple

Jim Vaselopulos on LinkedIn

Clarity: Business Wisdom to Work Less and Achieve More

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 11, 2023

Announcing "Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor"

It’s finally here! I can now announce my latest book, a philosophical biography called Marcus Aurelius: The Stoic Emperor, part of the Yale University Press Ancient Lives series. When the series editor, James Romm, contacted me I was very pleased because although there are already several excellent biographies of Marcus Aurelius, I always felt there was something missing. I wanted to write a biography that said more about Stoic philosophy and how it influenced Marcus’ life as a young man, and later his actions as emperor. I hope I achieved that, while also giving the reader a few ideas they can take away and benefit from in their own lives.

The book is now available for pre-order in hardback, due out 7th Feb 2024. Ebook and audiobook edition will be forthcoming (narrated by me). You can get a copy now from Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and other retailers via the publisher’s website. NB: This title is eligible for Amazon’s pre-order price guarantee, which means that if you order your copy now, not only will you be helping the author (!) but you will also be more likely to benefit from certain discounts off the price. (See Amazon’s website for terms and conditions.)

Experience the world of Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius and the tremendous challenges he faced and overcame with the help of Stoic philosophy.

Yales’ Ancient Lives series consists of titles by leading academics who unfold the stories of thinkers, writers, kings, queens, conquerors, and politicians from all parts of the ancient world. The aim is for readers to come to know these figures in fully human dimensions, complete with foibles and flaws, and to see that the issues they faced—political conflicts, constraints based in gender or race, tensions between the private and public self—have changed very little over the course of millennia.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Experts Praise the Book“Few historical figures are as fascinating as Marcus Aurelius, the emperor-philosopher. And few writers have been so effective at bringing his complex life and character to the attention of modern readers as Donald Robertson.”—Massimo Pigliucci, author of How to Be a Stoic: Using Ancient Philosophy to Live a Modern Life

“Robertson has written a very thorough and very readable account of Marcus’s life and the events and people that shaped him. Anyone who wants to understand the author of Meditations should read this book.”—Robin Waterfield, author of Marcus Aurelius, Meditations: The Annotated Edition

“Donald Robertson guides us into the world of a philosopher-emperor whose humility and Stoic teachings fill the pages. We are indebted to Robertson for this wonderful account of the emperor who penned notes to himself while in battle that would be later known as the Meditations and read by millions for philosophical inspiration. Simply spellbinding.”—Nancy Sherman, author of Stoic Wisdom: Ancient Lessons for Modern Resilience

“This highly readable biography is the perfect place to begin for anyone who wants to learn more about the man behind the Meditations.”—John Sellars, author of Marcus Aurelius (Philosophy in the Roman World)

“Robertson’s biography provides a compelling narrative of Marcus’ life, carefully based on the primary sources. He brings out very clearly the life-long significance of Stoicism for Marcus and the interplay between philosophy, politics, and warfare.”—Christopher Gill, author of Marcus Aurelius: Meditations, Books 1-6

Description

DescriptionAdd this title to your Goodreads bookshelf.

This novel biography brings Marcus Aurelius (121–180 CE) to life for a new generation of readers by exploring the emperor’s fascinating psychological journey. Donald J. Robertson examines Marcus’s relationships with key figures in his life, such as his mother, Domitia Lucilla, and the emperor Hadrian, as well as his Stoic tutors. He draws extensively on Marcus’s own Meditations and correspondence, and he examines the emperor’s actions as detailed in the Augustan History and other ancient texts.

Marcus Aurelius struggled to reconcile his philosophy and moral values with the political pressures he faced as emperor at the height of Roman power. Robertson examines Marcus’s attitude toward slavery and the moral dilemma posed by capturing enemies in warfare; his attitude toward women; the role of Stoicism in shaping his response to the threat of civil war; the treatment of Christians under his rule; and the naming of his notorious son Commodus as his successor.

Throughout, the Meditations is used to shed light on the mind of the emperor—his character, values, and motives—as Robertson skillfully weaves together Marcus’s inner journey as a philosopher with the outer events of his life as a Roman emperor.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Table of ContentsPrologue: Truth in the Meditations

Chapter One. The Mother of Caesar

Chapter Two. Verissimus the Philosopher

Chapter Three. The Greek Training

Chapter Four. Hadrian’s Vendettas

Chapter Five. The Death of Hadrian

Chapter Six. Disciple of Antoninus

Chapter Seven. Disciple of Rusticus

Chapter Eight. The Two Emperors

Chapter Nine. The Parthian Invasion

Chapter Ten. The War of Lucius Verus

Chapter Eleven. Parthicus Maximus

Chapter Twelve. The Antonine Plague

Chapter Thirteen. The War of Many Nations

Chapter Fourteen. Germanicus

Chapter Fifteen. Sarmaticus

Chapter Sixteen. Cassius the Usurper

Chapter Seventeen. The Civil War

Chapter Eighteen. The Setting Sun

Epilogue: The Hall of Mysteries