Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 26

October 10, 2023

Alcibiades argues for Libertarianism

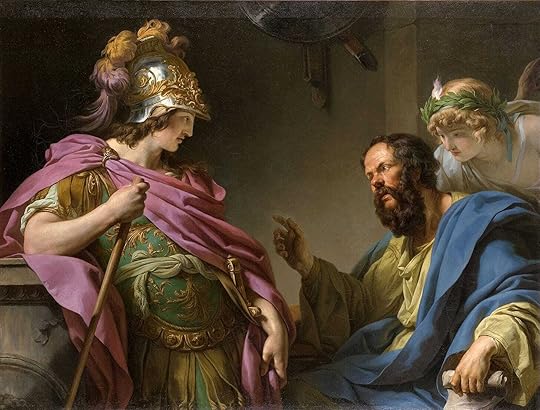

In Xenophon’s Memorabilia Socratis, there’s an unusual mini dialogue, in which he portrays the young aristocrat Alcibiades using the Socratic Method against his guardian, the great Athenian statesman, Pericles. Pericles was the leading champion of the Democrat faction. Alcibiades seemed to want to embarrass the older statesman by catching him in a contradiction. His argument is designed to show that Pericles does not understand the essential nature of law, and also to force him to question the validity of the laws passed by the Athenian Assembly.

Alcibiades and Socrates

Alcibiades and Socrates

Indeed, there is a story told of Alcibiades, that, when he was less than twenty years old, he had a talk about laws with Pericles, his guardian, the first citizen in the State.

“Tell me, Pericles,” he said, “can you teach me what a law is?”

“Certainly,” he replied.

“Then pray teach me. For whenever I hear men praised for keeping the laws, it occurs to me that no one can really deserve that praise who does not know what a law is.”

Thus the dialogue begins in typically Socratic fashion. Alcibiades approaches an expert and asks them to define the basic concept which underlies their area of expertise. Socrates, for instance, asked the Athenian general Laches to define “courage”; Alcibiades here asks Pericles, the leading statesmen in Athens, to define what is meant by “law”.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

“Well, Alcibiades, there is no great difficulty about what you desire. You wish to know what a law is. Laws are all the rules approved and enacted by the majority in assembly, whereby they declare what ought and what ought not to be done.”

“Do they suppose it is right to do good or evil?”

“Good, of course, young man, — not evil.”

Again, this is typically Socratic. The question seems too easy at first because an expert is being asked about his area of expertise. The “laws” are simply rules approved by the Assembly that governs Athens, in which all the male citizens vote. Pericles was the most senior statesman in the Assembly. He takes it for granted that he knows what a law is, but Alcibiades will attempt to show that this is a form of intellectual conceit — Pericles does not know what he believes he knows.

“But if, as happens under an oligarchy, not the majority, but a minority meet and enact rules of conduct, what are these?”

“Whatsoever the sovereign power in the State, after deliberation, enacts and directs to be done is known as a law.”

“If, then, a despot, being the sovereign power, enacts what the citizens are to do, are his orders also a law?”

“Yes, whatever a despot as ruler enacts is also known as a law.”

Oligarchy and tyranny were political systems opposed by Pericles and other Democrats. Tyranny refers to rule by an individual who makes his own laws, and is therefore above the law, like an absolute monarch or dictator. Oligarchy refers to rule by a “few”, i.e., an elite, usually a council of wealthy aristocrats, who make the laws, and impose them on the majority, i.e., the common people. Many Greek city-states were governed by individual tyrants or groups of oligarchs. Sparta, for instance, was basically an oligarchy, ruled by two kings, whose power was limited by a council of elders and other institutions, controlled by the aristocracy.

“But force, the negation of law, what is that, Pericles? Is it not the action of the stronger when he constrains the weaker to do whatever he chooses, not by persuasion, but by force?”

“That is my opinion.”

Tyrants and oligarchs impose the laws they pass on the majority, without their consent, and therefore by force. Alcibiades already has Pericles in trouble because Athenian foreign policy required him to deal with tyrants and oligarchic regimes, although he questions the validity of laws imposed by them.

“Then whatever a despot by enactment constrains the citizens to do without persuasion, is the negation of law?”

“I think so: and I withdraw my answer that whatever a despot enacts without persuasion is a law.”

“And when the minority passes enactments, not by persuading the majority, but through using its power, are we to call that force or not?”

“Everything, I think, that men constrain others to do ‘without persuasion,’ whether by enactment or not, is not law, but force.”

Pericles, is now hesitant and unsure, perhaps sensing he’s approaching a contradiction. Yet he agrees with Alcibiades that “laws” are made by tyrants and oligarchs without persuading the common people, or obtaining their consent, and are therefore imposed by force.

“It follows then, that whatever the assembled majority, through using its power over the owners of property, enacts without persuasion is not law, but force?”

Alcibiades now reveals the paradoxical conclusion he has been leading Pericles toward. The democratic Assembly behaves like a tyrant toward the property-owning aristocracy by imposing laws upon them with which they do not agree. Alcibiades is forcing Pericles, an aristocrat who leads the Assembly and the Democrat faction, to question whether such laws can be considered valid. He is suggesting the democracy is simply another instance of political coercion, albeit one in which the balance of power is reversed compared to an oligarchy. The poor, who are many, have joined forces to impose their will on the wealthy, who are few.

“Alcibiades,” said Pericles, “at your age, I may tell you, we, too, were very clever at this sort of thing. For the puzzles we thought about and exercised our wits on were just such as you seem to think about now.”

“Ah, Pericles,” cried Alcibiades, “if only I had known you intimately when you were at your cleverest in these things!”

The conclusion makes it clear that Alcibiades was trying to embarass Pericles by forcing him into an admission he found unpalatable. As sometimes happens in Socratic dialogues, though, he remains unconvinced despite seemingly being forced to expose a contradiction in his thinking. More seriously, Pericles has failed to demonstrate that he knows what “law” means, which undermines his claim to be an expert in the field of politics.

CommentaryWhatever we make of the dialogue, it seems to me that it bears a notable resemblance to certain arguments employed in right-wing libertarianism, of the form currently popular in the United States of America. Right-wing libertarianism is associated with what is known as the Non-aggression Principle,

The principle forbids “aggression,” which is understood to be any and all forcible interference with any individual’s person or property except in response to the initiation […] of similar forcible interference on the part of that individual.— Libertarianism.org

What libertarians mean by “aggression” is therefore comparable to what Alcibiades meant in the dialogue above by “force”. From the premise that the laws a tyrant imposes by force are not valid, Alcibiades leads Pericles to question the validity of the laws imposed by the majority, via the Assembly or Athenian state, on those who disagree with them, i.e., the aristocracy in this case.

Alcibiades doesn’t question the property-rights of the Athenian aristocracy. He implies that the Athenian state, in the form of the democratic Assembly, is a disguised form of tyranny, in which the poor majority conspire against the aristocracy, in order to redistribute their power and wealth.

Alcibiades was typically viewed as a champion of the Democrat faction, although his controversial political and military career brought him into conflict with other Democrats. Xenophon, despite his own oligarch sympathies, was not a fan of Alcibiades. In this dialogue, he appears to be trying to substantiate his claim that Alcibiades was not a good student of Socrates, and that he merely exploited Socratic teachings for his own political ends. Socrates himself paints a contrasting picture, e.g., in Plato’s Crito, where he argues, on the basis of a sort of “social contract” theory that by choosing to live in a country we fundamentally commit ourselves to accepting its legal system, even if we reject certain interpretations of the law.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

October 3, 2023

The Wisdom of Talking to Yourself

We could be forgiven for thinking that the philosophical ideas of Socrates, or at least those attributed to him, have already been studied quite exhaustively. Indeed, the scholarship began with Plato, Xenophon, and the other Socratics, carried on throughout many centuries, and still continues in universities today. Almost all of this research has been philosophical, however, and virtually none of it is psychological. Perhaps because of my interdisciplinary background, in philosophy and psychotherapy, it struck me that some of the most important lessons we might learn from Socrates relate to what we might describe as the psychology of philosophy.

Photo by Laurenz Kleinheider on Unsplash

Photo by Laurenz Kleinheider on UnsplashMany psychological observations can be made about the peculiar way that Socrates is portrayed doing philosophy, and his use of the Socratic Method. The first thing we might notice, however, is simply that he believes philosophy, the love of wisdom, can best be pursued by examining some of the most important assumptions held by other people. Socrates believed that he could learn more about the nature of wisdom by using the Socratic Method in dialogue with his interlocutors, than by quietly applying philosophy to his own life in solitude.

Solomon’s ParadoxRecent research by social psychologists has, indeed, provided some fascinating support for Socrates’ approach to wisdom. Prof. Igor Grossmann is the head of a centre at the University of Waterloo in Canada, called the Wisdom and Culture Lab, which carries out psychological research studying wisdom. Wisdom has already been shown to be related to wellbeing. One of Grossmann’s initial insights was that we typically exhibit greater wisdom when considering other people’s problems than we do when considering our own.

We chose the term Solomon’s Paradox to identify the contradiction between thinking about other people’s problems wisely, but failing to do so for ourselves. The Biblical King Solomon, known for his keen intellect and unmatched wisdom in guiding others, failed to apply wisdom in his own life, which ultimately led to the demise of his kingdom. — Grossmann, ‘Why We Give Great Advice To Others But Can't Take it Ourselves’, Forbes Magazine, Apr 7, 2015

Experiments carried out by Grossmann and his colleagues appeared to confirm that our judgment becomes better, or wiser, when we are examining other people’s lives. For example, they gave experimental subjects the same relationship problem to discuss, but whereas one group were asked to imagine it was a friend’s problem the other group viewed it as if it were their own problem.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Wisdom was defined by the researchers in terms of measures of intellectual humility, such as being willing to search for additional information that could inform their judgment; open-mindedness, such as being more likely to look at the situation from the perspectives of others involved; and compromise, or being willing to combine alternative perspectives to find a solution. The group examining the problem as if it happened to a friend turned out to score 22% better on ratings of intellectual humility, 31% better on open-mindedness, and 15% better on compromise. These and other experiments therefore confirm, to put it simply, that we’re better at giving other people advice than giving it to ourselves.

So far, this might seem like bad news. There may, however, be ways to protect ourselves from the psychological limitations caused by Solomon’s Paradox. What if we can examine our own beliefs as if they belonged to other people? Socrates makes it clear that he can imagine being in his interlocutor’s shoes, sharing some of their assumptions, and making similar errors to the ones they make. Through his method of questioning, in fact, he uses the other person as a mirror, of sorts, in which he may examine his own reflection. They reflect back the image not of his face but his intellect. The other person becomes a philosophical laboratory in which Socrates may examine his own beliefs, and mistakes he might potentially make, with greater detachment and objectivity than if doing so alone.

The dialogue format adopted by Plato and the other Socratics brings this to life for us. From our perspective, Socrates and his interlocutor provide mirrors capable of reflecting our own assumptions about important questions such as the nature of justice, or wisdom itself. When we read philosophical dialogues, or engage in a similar sort of dialogue with a real person, we gain a broader perspective from which to consider our beliefs. We can more easily imagine the consequences of holding a particular belief, its wider impact on our relationships, how it might influence one’s character and actions, whether it conflicts with other beliefs, and how it might relate to a variety of different situations.

IlleismThere are signs, moreover, that Socrates adapted the philosophical method he used in the dialogues for solitary use. When someone asked Antisthenes, for instance, what benefit he had obtained from studying philosophy with Socrates, he replied “The ability to hold conversations with myself.” We don’t have any explanation of what he meant by that, however, we do find several intriguing references to Socrates having philosophical conversations with himself.

In Plato’s Hippias Major, for example, Socrates keeps referring to a mysterious man who relentlessly pesters him with questions, as though trying to refute him. Socrates describes him as a very close relative, who even shares his home. He waits there to challenge Socrates when he comes home from speaking about such things as wisdom and justice with the Sophists.

So whenever I go home to my own house, and he hears me saying these things, he asks me if I am not ashamed that I have the face to talk about beautiful practices, when it is so plainly shown, to my confusion, that I do not even know what the beautiful itself is. “And yet how are you to know,” he will say, “either who produced a discourse, or anything else whatsoever, beautifully, or not, when you are ignorant of the beautiful?

Socrates appears to let slip that the man in question is none other than “Socrates, the son of Sophroniscus, who would no more permit me to say these things carelessly without investigation than to say I know what I do not know.”

The strange man is therefore Socrates himself, viewed as if he were another person. In other words, even after Socrates had finished having a dialogue with one of his friends about philosophy he would continue by having an imaginary dialogue with himself in private. This other (second) Socrates, the stranger, was imagined pointing out the limitations of the real (first) Socrates’ perspective, challenging his biases, by questioning the definitions he took for granted of important concepts.

Likewise, in Plato’s Crito, Socrates says that he is going to imagine being interrogated by the Laws of Athens. According to him they say: “Tell us, Socrates, what you are about?” and later “Answer Socrates, instead of acting astonished — you are in the habit of asking and answering questions!” He then proceeds to conduct an imaginary dialogue between himself and these Laws. By engaging in dialogue with others, Socrates therefore learned how to engage in imaginary dialogue with himself.

We can achieve greater objectivity with regard to our own thinking by imagining someone else challenging our beliefs, as Socrates describes doing. A related, and perhaps easier, method, however, consists in referring to our own thoughts and actions as if we were talking about those of someone else. Third-person self-talk is actually known as “illeism”, from the Latin ille meaning “he” (the third-person pronoun). For example, rather than thinking “I’m really upset and I don’t know whether I should stay or go!” (first person), I might say to myself “Donald is really upset and he doesn’t know whether he should stay or go” (third person).

In another research study, Grossmann and his colleagues examined whether it makes any difference to talk about our own problems in the first-person or third-person. They compared two groups of subjects, again discussing a hypothetical relationship problem. The results showed that simply by phrasing things differently, talking about their own problem as if they were talking about someone else’s, participants were 35% more likely to employ a “wiser” style of reasoning than normal, as if giving advice to a friend. This is, more or less, what Socrates is portrayed as doing when he pretends that an imaginary stranger, or the Laws of Athens, are criticizing his thinking and pointing out his errors.

More recently, a pair of studies on illeism, which the researchers call “distanced self-reflection”, asked a total of 555 participants to record their thoughts in a journal for four weeks. In order to test whether wise reasoning could be cultivated in daily life, participants were to write about various pleasant or troubling social experience that happened each day, one group using first-person and the other third-person language. Those employing illeism were found to have improved their “wisdom” as measured by ratings of intellectual humility, acknowledging others’ perspectives, and conflict resolution. The study also found some evidence that those employing illeism experienced less negative emotion, such as anger or frustration, in their relationships.

Illeism in Cognitive TherapyThere’s good evidence that illeism can not only help wisdom and problem-solving but that it may be therapeutic when it comes to negative emotions. In a recent systematic review, Wallace-Hadrill and Kamboj (2016) identified no less than 38 studies in which the effect on emotion of deliberately adopting a third-person perspective was measured, including with regard to anxiety, sadness, anger, and guilt. Across the board, evidence was found that the intensity of emotion was reduced, and the meaning of events was viewed differently.

Indeed, similar verbal techniques are already widely-used in cognitive psychotherapy. For example in their 1985 manual for the treatment of anxiety disorders, Aaron T. Beck, and his colleagues, describe referring to our thoughts in the third-person as a technique for emotional self-regulation. Someone might describe his own worries by saying “Bill is feeling anxious, he’s worried others are judging him negatively…” as if he were observing the thoughts of another person (Beck, Emery, & Greenberg, 2005, p. 194).

In conclusion, there’s good reason to view certain aspects of the Socratic Method as having measurable psychological benefits. Socrates is portrayed using dialogue as a means of developing his self-awareness by treating the other person as a mirror for his own intellect. He also explicitly uses illeism in several places, referring to himself in the third-person by engaging in imaginary dialogue with a second Socrates or with the personified Laws of Athens, and so on, in order to examine his own beliefs and biases from a more objective point of view.

ReferencesWallace-Hadrill SMA and Kamboj SK (2016) The Impact of Perspective Change As a Cognitive Reappraisal Strategy on Affect: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 7:1715. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01715

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

September 26, 2023

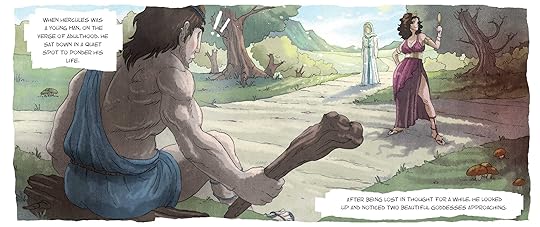

Read our Graphic Novel: Verissimus

Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius is a full-color graphic novel about the life and philosophy of the Stoic Roman emperor, published by St. Martin’s Press. The book was chosen as an Amazon editor’s pick for Best History Book, where it has earned 4.8 stars on average from reviewers. (It’s become a popular gift — check Amazon and other retailers now for special offers!) Verissimus has also been reviewed over by hundreds of readers on Goodreads. Below you can see a sample of the artwork, by award-winning Portuguese illustrator, Ze Nuno Frage, and read the whole section relating the legendary story that first inspired Stoic philosophers! Please let us know what you think in the comments. Thanks for reading!

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

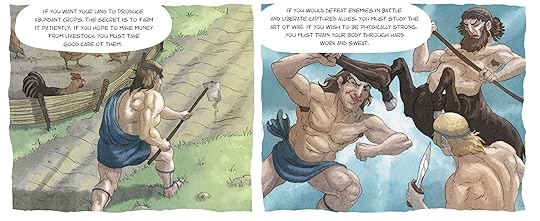

The Choice of HerculesThis excerpt from chapter four depicts a story within a story. The Stoic philosopher, Apollonius of Chalcedon is delivering a lecture attended by the young Caesar Marcus Aurelius. He relates the famous allegorical story, known today as the Choice of Hercules. We’re told that it was reading this story that inspired Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, to become a philosopher. It’s an example of protreptic, or an exhortation to follow a life of virtue, rather than hedonism. Zeno read the version in Xenophon’s Memorabilia, which claims to record Socrates telling the story, based on the original speech composed by his friend, the Sophist Prodicus. (NB: These graphics are best viewed on Substack via the web.)

1. When Hercules was a young man, on the verge of adulthood, he sat down in a quiet spot to ponder his life. After being lost in thought for a while, he looked up and noticed to beautiful goddesses approaching.

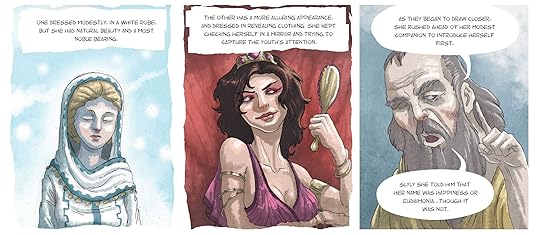

2. One dressed modestly, in a white robe, but she had natural beauty and most noble bearing. The other had a more alluring appearance and dressed in revealing clothing. She kept checking herself in a mirror and trying to capture the youth’s attention.

Apollonius: “As they began to draw closer, she rushed ahead of her modest companion to introduce herself first. Slyly, she told him that her name was Happiness or Eudaimonia… though it was not.”

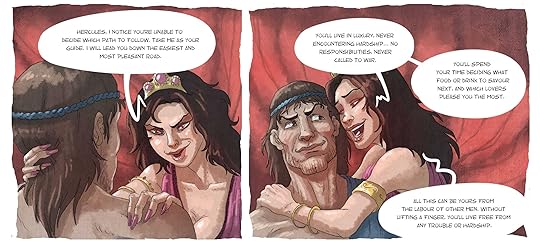

3. Kakia: “Hercules, I notice you’re unable to decide which path to follow. Take me as your guide. I will lead you down the easiest and most pleasant road. You’ll live in luxury, never encountering hardship… no responsibilities, never called to war. You’ll spend your time deciding what food or drink to savor next, and which lovers please you the most. All this can be yours from the labor of other men. Without lifting a finger, you’ll live free from any trouble or hardship.”

4. Arete: “I too am here to counsel you, Hercules. Having studied your character from afar, I am certain that by following my path you will become a great hero. However, rather than make false promises of future pleasures, I will tell you the truth ordained by the gods… Nothing truly good and admirable can ever belong to men without effort on their part. If you want to be loved by your friends, for example, you must be kind to them. To be honored by great cities, you must help their citizens. To be admired throughout the world, you must benefit all of mankind.”

5. Arete: “If you want your land to produce abundant crops, the secret is to farm it patiently. If you hope to make money from livestock, you must take good care of them. If you would defeat enemies in battle and liberate captured allies, you must study the art of war. If you wish to be physically strong, you must train your body through hard work and sweat.”

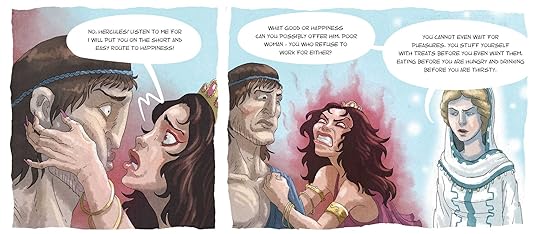

6. Kakia: “No, Hercules! Listen to me for I will put you on the short and easy route to happiness!”

Arete: “What good or happiness can you possibly offer him, poor woman — you who refuse to work for either? You cannot even wait for pleasures. You stuff yourself with treats before you even want them, eating before you are hungry and drinking before you are thirsty.”

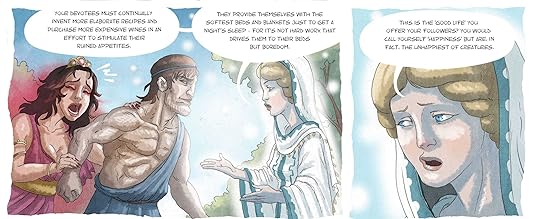

7. Arete: “Your devotees must continually invent more elaborate recipes and purchase more expensive wines in an effort to stimulate their ruined appetites. They provide themselves with the softest beds and blankets just to get a night’s sleep — for it’s not hard work that drives them to their beds but boredom. This is the ‘good life’ you offer your followers? You would call yourself ‘Happiness’ but are, in fact, the unhappiest of creatures?”

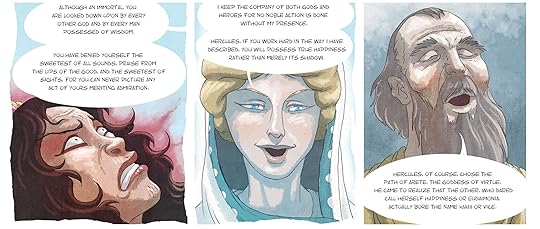

8. Arete: “Although an immortal, you are looked down upon by every other god and by every man possessed of wisdom. You have denied yourself the sweetest of all sounds, praise from the lips of the good, and the sweetest of sights, for you can never picture any act of yours meriting admiration. I keep the company of both gods and heroes for no noble action is done without my presence. Hercules, if you work hard in the way I have described, you will possess true happiness rather than merely its shadow.”

Apollonius: “Hercules, of course, chose the path of Arete, the goddess of Virtue. He came to realize that the other, who dared call herself Happiness or Eudaimonia, actually bore the name Kakia or Vice.”

Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius is available from all good bookstores, including Amazon and other online retailers.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

September 21, 2023

Video: Talking to Brian Johnson about Stoicism

I recently spoke with Brian Johnson, author of A Philosopher's Notes, about Stoicism, self-improvement, and psychotherapy. You can now watch our conversation on YouTube.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

September 17, 2023

A Simplified Modern Approach to Stoicism

This article is designed to provide a very concise introduction to Stoicism as a way of life, through a simplified set of Stoic psychological practices.

The first few passages of Epictetus’ Handbook (Enchiridion) actually provide an account of some fundamental practices that can form the basis of a simplified approach to Stoicism and this account is closely based on those. I recommend you treat it as an introduction to the wider Stoic literature. However, starting with a set of basic practices can help people studying Stoic philosophy to get to grips with things before proceeding to assimilate some of the more diverse or complex aspects found in the ancient texts.

Both Seneca and Epictetus refer to the Golden Verses of Pythagoras, which happens to provide a good framework for developing a daily routine, bookended by morning and evening contemplative practices.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Zeno of Citium, who founded Stoicism in 301 BC, expressed his doctrines in notoriously terse arguments and concise maxims. However, Chrysippus, the third head of the Stoic school, wrote over 700 books fleshing these ideas out and adding complex arguments to support them. Let’s focus here on the concise version but bearing in mind there’s a more complex philosophy lurking in the background. For example, Epictetus, the only Stoic teacher whose works survive in any significant quantity, described the central precept of Stoicism to his students as follows:

And to become educated [in Stoic philosophy] means just this, to learn what things are our own, and what are not. (Discourses, 4.5.7)

The practical consequence of this distinction is essentially quite simple:

What, then, is to be done? To make the best of what is in our power, and take the rest as it naturally happens. (Discourses, 1.1.17)

The routine below is designed to provide an introduction to Stoic practice for the 21st Century, which can lead naturally into a wider appreciation of Stoic philosophy as a way of life. The instructions are designed to be as straightforward and concise as possible, while still remaining reasonably faithful to classical Stoicism. The most popular book for people to read who are new to Stoicism is The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, so we recommend that you also consider reading a modern translation of that text during the first few weeks of your Stoic practice.

The Basic Philosophical RegimeStage 1: Morning PreparationPlan your day ahead with the Stoic “reserve clause” in mind. Decide what goals you want to achieve in advance and make a decision to try to achieve them but with the caveat: “Fate permitting.” In other words, aim for success and pursue it wholeheartedly while also being prepared to accept setbacks or failure with equanimity, insofar as they lie outside of your direct control.

Try to choose your goals wisely, picking things that are rational and healthy for you to pursue. Your primary goal throughout these three stages should be to protect and improve your fundamental wellbeing, particularly in terms of your character and ability to think clearly about your life. You’re going to try to do this by cultivating greater self-awareness and practical wisdom, which requires setting goals for yourself that are healthy, while pursuing them in a sort of “detached” way, without being particularly attached to the outcome.

Stage 2: Stoic Mindfulness (Prosochê) Throughout the DayThroughout the day, continually pay attention to the way you make value-judgements and respond to your thoughts. Be mindful, in particular of the way you respond to strong emotions or desires. When you experience a distressing or problematic thought, pause, and tell yourself: “This is just a thought and not at all the thing it claims to represent.”

Remind yourself that it is not things that upset you but your judgements about things. Where appropriate, rather than being carried away by your initial impressions, try to postpone responding to them for at least an hour, waiting until your feelings have settled down and you are able to view things more calmly and objectively before deciding what action to take.

Once you have achieved greater self-awareness of your stream of consciousness and the ability to take a step back from your thoughts in this way, begin to also apply a simple standard of evaluation to your thoughts and impressions as follows. Having paused to view your thoughts from a distance, ask yourself whether they are about things that are directly under your control or things that are not.

This has been called the general precept or strategy of ancient Stoic practice. If you notice that your feelings are about something that’s outside of your direct control then respond by trying to accept the fact that it’s out of your hands, saying to yourself: “This is nothing to me.” Focus your attention instead on doing what is within your sphere of control with wisdom and to the best of your ability, regardless of the actual outcome. In other words, remind yourself to apply the reserve clause described above to each situation. Look for ways to remind yourself of this. For example, the Serenity Prayer is a well-known version of this idea, which you might want to memorise or write down somewhere and contemplate each day.

Give me the Serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

The Courage to change the things I can,

And the Wisdom to know the difference.

You may find that knowing you are going to review these events and evaluate them in more detail before you sleep (see below) actually helps you to become more mindful of how you respond to your thoughts and feelings throughout the day.

Stage 3: Night-time ReviewReview your whole day, three times, if possible, before going to sleep. Focus on the key events and the order in which they happened, e.g., the order in which you undertook different tasks or interacted with different people during the day.

What did you do that was good for your fundamental wellbeing? (What went well?)

What did you do that harmed your fundamental wellbeing? (What went badly?)

What opportunities did you miss to do something good for your fundamental wellbeing? (What was omitted?)

Counsel yourself as if you were advising a close friend or loved one. What can you learn from the day and, where appropriate, how can you do better in the future? Praise yourself for what went well and allow yourself to reflect on it with satisfaction. You may also find it helps to give yourself a simple subjective rating (from 0–10) to measure how consistently you followed the instructions here or how good you were at pursuing rational and healthy goals while remaining detached from things outside of your direct control. However, also try to be concise in your evaluation of things and to arrive at conclusions without ruminating over things for too long.

Appendix: Some Additional Stoic PracticesThere’s a lot more to Stoicism, in terms of both the theory and practice. You might want to begin with a simple approach but you should probably broaden your perspective eventually to include the other parts of Stoicism. Reading The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius and other books can provide you with a better idea of the theoretical breadth of Stoic philosophy. Here are three examples of other Stoic practices, followed by a link to a longer and more detailed article on this site…

Contemplation of the Sage: Imagine the ideal Sage or exemplary historical figures (Socrates, Diogenes, Cato) and ask yourself: “What would he do?”, or imagine being observed by them and how they would comment on your actions.

Contemplating the Whole Cosmos: Imagine the whole universe as if it were one thing and yourself as part of the whole, or the View from Above: Picture events unfolding below as if observed from Mount Olympus or a high watchtower.

Premeditation of Adversity: Mentally rehearse potential losses or misfortunes and view them as “indifferent” (decatastrophizing), also view them as natural and inevitable to remove any sense of shock or surprise.

For a more detailed account of these and other Stoic psychological techniques see my books Stoicism and the Art of Happiness and How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius.

September 14, 2023

How to Apply Stoicism to Physical Exercise

I’ll admit right from the outset that I’m no expert on physical fitness. So why write about it? I’ve been looking for years for a good discussion of how Stoic philosophy could be applied to the psychology of exercise. I’ve decided that it might be of value to jot down my own notes, and questions, regarding the potential uses of Stoicism in this regard. My area of expertise is psychotherapy, particularly treatment of anxiety disorders, but also, to a lesser extent, issues like pain management.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

There’s an obvious overlap between what we know works in these areas and what’s at least worthy of investigation in relation to exercise. Modern psychologists know a lot, for instance, about how to cope with pain. Does that potentially offer us guidance when it comes to coping with the discomfort and fatigue felt when lifting heavy weights or jogging long distances, and so on? Stoicism offers us a philosophical framework for employing techniques from cognitive therapy and, perhaps, holds out the hope of a whole philosophy of fitness, which is consistent with modern cognitive-behavioural research in psychology.

Photo by Simone Pellegrini on UnsplashThe Goal of Exercise

Photo by Simone Pellegrini on UnsplashThe Goal of ExerciseTolerance of discomfort plays an important role in modern psychotherapy and voluntary endurance of hardship is integral to training in ancient Stoicism. So could physical exercise offer a way of training not just our bodies but also our minds, in accord with the goals of Stoic philosophy. Stoicism was a famously paradoxical philosophy, meaning that it taught doctrines that seemed, at first, completely at odds with the prevailing values of society. Most people pursue wealth and status as if they were ends in themselves, whereas the Stoics believed this was a mistake. Likewise, it seems clear that most (but not all) people today see the primary goal of physical exercise primarily as physical wellbeing or improving their appearance, e.g., through weight loss. Some people exercise in order to compete with others in sports.

The Stoics consider it a fundamental error, though, to treat any of these goals as primary. They are, at best, preferred indifferents. These are things we naturally desire in some circumstances but which are of no intrinsic value in relation to our true goal, which for Stoicism is moral wisdom or arete (virtue) — and the improvement of our character. Stoics would, therefore, be exercising for fundamentally different reasons than the majority of people. Perhaps this helps to address one challenge with the psychology of exercise: motivation. People who exercise to lose weight, for instance, often lose motivation to continue exercising once they achieve their goal. People who are trying to build strength, can lose motivation when they hit a plateau and stop making gains. At some point, our focus must shift on to maintenance rather than improvement, but not everyone finds that sufficiently motivating to keep up the effort required for consistent physical exercise.

Exercise, for Stoics, is primarily about developing self-discipline, psychological endurance, and strength of character in general.

Curiously, Stoic philosophy would view physical exercise primarily in terms of moral or psychological goals. Exercise, for Stoics, is mainly about developing self-discipline, psychological endurance, and strength of character. That’s not how most people think of going to the gym, however — or at least it’s certainly not how they talk about exercise. It may have implications for how we would approach exercise in practice. For instance, Diogenes the Cynic famously built endurance by holding his naked body against frozen statues in winter — the modern equivalent would be having cold showers every day. Reputedly a Spartan asked him how he managed to do it and Diogenes replied that it becomes quite easy with practice. The Spartan, however, replied “What’s the point then?”

Lifting weights or jogging becomes easier with practice. Arguably more self-discipline is required by someone who is unfit and overweight, or recovering from illness or injury, and beginning to attempt even modest exercise. The psychological challenge, for them, may be much greater than for someone who is already fit and finds exercise naturally easy and enjoyable. Would the Cynics and Stoics therefore advise us to keep seeking different physical challenges to avoid complacency?

Applying Stoicism to ExerciseThere’s a great deal more we could say about this subject but I want to focus on some practical techniques, which I think might be worth evaluating. These actually lend themselves to being tested fairly easily in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) — the gold standard for outcome research. Stoic psychological practices often help us cope with discomfort, such as the fatigue of lifting weights or jogging. It may be that these sort of techniques can be applied more easily to static forms of physical exercise where endurance clearly becomes the main challenge, such as isometric exercises, including The Plank, or perhaps dynamic tension. (Although these forms of exercise may be less suitable than others for general fitness training.)

Below, I’ll list several general Stoic strategies for physical exercise, broken down into specific tactics or techniques.

September 10, 2023

How to Drink Like a Roman Emperor

Every so often I receive emails from people who have struggled to cope with their own alcoholism or that of their loved ones. They tell me how they’ve found great support and consolation in the writings of ancient Stoic philosophers, such as The Meditations of Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius. Those who are familiar both with the Stoics and the Twelve Step Program often recognize connections between them. The Serenity Prayer, for instance, made famous by Alcoholics Anonymous, neatly encapsulates one of the most characteristic doctrines of Stoic philosophy.

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

Courage to change the things I can,

And wisdom to know the difference.

The Stoic philosopher Epictetus taught his students the same thing:

What, then, is to be done? To make the best of what is in our power, and take the rest as it naturally happens. — Discourses, 1.1

Emperor Marcus Aurelius, the last famous Stoic of antiquity

Emperor Marcus Aurelius, the last famous Stoic of antiquityThere are countless other references in the Stoic literature to making a firm distinction between what’s under our control and everything else: what we do versus what merely happens to us. We should take greater responsibility for what’s up to us, according to Stoicism, and get less upset about what is not. Wisdom consists largely in bearing this simple — almost commonsense — distinction in mind and being clearer about its practical and emotional implications for us in daily life.

Modern Stoics tend to call this idea the “dichotomy of control” or “Stoic fork”. However Stoicism offers much more than just this wise maxim — it’s a complete philosophy of life. One person who contacted me about alcoholism and Stoicism therefore described it as “the Serenity Prayer on steroids”.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Stoic TherapyThe most influential psychological principle of Stoicism comes from another one of Epictetus’ sayings:

It’s not things that upset us but our judgments about things. — Encheiridion, 5

That became the inspiration for modern cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), the leading evidence-based approach to psychotherapy today. Both Stoicism and CBT are based on the idea that our emotions are largely — if not exclusively — determined by our underlying beliefs. From that shared premise they draw similar conclusions about how best to change feelings by changing our voluntary thoughts (cognitions) and actions (behaviour).

For the Stoics, the beliefs that upset us ultimately take the form of strong value judgments about things outside our direct control being either extremely bad or extremely good, leading to excessive fear or desire respectively. The Stoics argued that it was irrational — a veritable recipe for neurosis — to have a strong desire to get or avoid external things insofar as they are beyond our direct control. It’s healthier to focus on our own voluntary actions instead and take more responsibility for the way we respond to the situations that befall us.

We need to learn to do our own work, in a sense, by focusing more attention on what we can do rather than worrying about the things fate throws at us. When we can’t change something we need to learn to accept that fact with Stoic indifference. As Shakespeare put it:

Things without all remedy should be without regard. — Macbeth

The Eleventh Step uses more religious language to express this attitude of emotional acceptance in dealing with alcoholism:

[We sought] through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God as we understood Him, praying only for knowledge of His will for us and the power to carry that out.

We should, in other words, learn to accept reality — the Will of God, if you prefer theological language — and adapt accordingly to the demands of our situation.

The Eleventh Step also contains the following retrospective meditation technique.

When we retire at night, we constructively review our day. Were we resentful, selfish, dishonest or afraid? Do we owe an apology? Have we kept something to ourselves which should be discussed with another person at once? Were we kind and loving toward all? What could we have done better? Were we thinking of ourselves most of the time? Or were we thinking of what we could do for others, of what we could pack into the stream of life? But we must be careful not to drift into worry, remorse or morbid reflection, for that would diminish our usefulness to others.

“After making our review”, the authors say, “we ask God’s forgiveness and inquire what corrective measures should be taken.” This obviously resembles an influential technique described in The Golden Verses of Pythagoras, which was adopted by the Stoics. We find it in the writings of Epictetus, Seneca, and also in a book by Galen, Marcus Aurelius’ court physician, about Stoic therapy practices. Before retiring to sleep each night, it advises us to review the events of the day three times asking ourselves three questions: What we did well? What we did badly? What we omitted to do?

The Big Book continues by describing a complementary prospective meditation technique:

On awakening let us think about the twenty-four hours ahead. We consider our plans for the day. Before we begin, we ask God to direct our thinking, especially asking that it be divorced from self-pity, dishonest or self-seeking motives. Under these conditions we can employ our mental faculties with assurance, for after all God gave us brains to use. Our thought-life will be placed on a much higher plane when our thinking is cleared of wrong motives.

This also resembles morning meditation practices found in The Golden Verses of Pythagoras, and the writings of the Stoics.

The Stoic is a real beerThe Stoics on Alcohol

The Stoic is a real beerThe Stoics on AlcoholSo how did the Stoics view alcohol? The historian Diogenes Laertius, a “doxographer” who recorded the views of Greek philosophers, says that the Stoics typically drank wine in moderation, but would not allow themselves to get drunk. Stobaeus, another doxographer, tells us that the Stoics classified excessive love of wine as a disease, although curiously they considered hating it too much to be one as well. Although the Stoics typically appear to have favoured moderation, they may perhaps have agreed with the Twelve Step Program’s abstinence approach for individuals who struggle to limit their drinking.

Stoics had to be careful they were abstaining for the right reasons, though. Epictetus seems to assume that his students have sometimes become “water drinkers”, presumably abstaining from wine, for the purposes of training in Stoicism (Discourses, 3.14). He criticizes them for telling everyone they meet “I drink water”, as if the goal is to show off. He says that if what they’re doing is good for them they should be satisfied with that and shut up instead of going on about it to the annoyance of others.

The Stoic wise man (or woman) views alcohol itself with studied indifference and focuses instead on the use he makes of it. Everything can be used either well or badly, according to the Stoics. So the wise man pays attention to the present moment and whether he is acting wisely or foolishly, with self-discipline or recklessness, in a healthy manner or an unhealthy one, and so on. To help ourselves make progress in this direction, we should actually set aside time to study how people we admire cope with temptation, trying to learn from their attitude and emulate their behaviour.

Marcus Aurelius’ most important role model was his adoptive father the emperor Antoninus Pius. Marcus writes in his notes that what was traditionally said of Socrates could be said of Antoninus: he was able to abstain from or enjoy those things that the majority of us are either too weak to abstain from or enjoy over-indulgently (Meditations, 1.16). Marcus says that Antoninus showed strength, endurance, and restraint whether he chose to abstain from something or partake in it, and that this is “the mark of someone who possesses a well-balanced and invincible character”.

Lucius Verus and Marcus AureliusThe Emperor Lucius Verus

Lucius Verus and Marcus AureliusThe Emperor Lucius VerusIn my recent book, How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, I used stories from the life of Marcus Aurelius to illustrate ways Stoicism can be applied in practice to help us deal with psychological problems today. However, we can also learn from other people’s mistakes. Marcus’ temperance stood in contrast to the notorious self-indulgence of his adoptive brother and co-emperor, Lucius Verus. From the way Roman historians describe him it appears likely that he was an alcoholic. We’re told that when he was meant to be commanding the legions in the Parthian war instead he would spend his time throwing parties, gambling, and drinking. He was obsessed with the chariot races and had a huge crystal goblet made, named Volucer after his favourite horse, which we’re told “surpassed the capacity of any human draught”.

Lucius would get drunk and “wander about at night through taverns and brothels with only a common travelling-cap for a head-covering, revel with various rowdies, and engage in brawls, while concealing his identity”, according to the Historia Augusta. Sometimes he would stagger drunk into the cook-shops and throw heavy coins at the cups, smashing them, and “often, they say, when he returned, his face was beaten black and blue”. He liked to feast late into the night, until he passed out at his banqueting table, and had to be carried to bed by his servants. We’re told his health was “weakened by such follies of debauchery and extravagance”.

The same historian claims that shortly after being acclaimed emperor, Lucius’ character was revealed to be “weak and base” when he was supposed to be leading the Roman counter-offensive against a Parthian invasion. Indeed, “while a legate [a Roman general] was being slain, while legions were being slaughtered, while Syria meditated revolt, and the East was being devastated”, Lucius spent all of his time hunting in the countryside or partying with his entourage in the brothels and taverns of one pleasure resort after another.

We’re told Marcus was sorely tested by the vices of his brother, particularly his “excessive candour and hot-headed plain speaking”, described as the result of “natural folly”. Lucius was struggling to cope with his feelings, though. During the Parthian War, Lucius wrote to a family friend complaining in desperation of “the anxieties that have rendered me very miserable day and night, and almost made me think that everything was ruined.” He’s probably referring to problems negotiating with the hostile Parthians, but he was clearly overwhelmed by emotional distress. Binge drinking, casual sex, gambling, and partying became his way of coping, albeit badly, with the pressures of his role as Marcus’ junior co-emperor.

In The Meditations, Marcus arguably damns him with faint praise and says only that observing Lucius’ character compelled him to take better care of his own, although he was also reassured by his brother’s respect and affection (1.17). I think Marcus perhaps watched helpless as Lucius’ life disintegrated, and vowed that he would never let himself make the same mistakes. Instead, he spent decades improving his character through training in Stoicism. If Lucius had practised Stoicism like his brother could it have helped him?

Frank’s Recovery StoryFrank, a retired NYPD Officer, got in touch to tell me about the role Stoicism played in his own recovery:

In the rooms of AA with the Twelve Steps and my sponsor I built the archway that I walked through a free man, and which lead me to the Stoics. On my journey I was searching for anything that might help me spiritually because my childhood faith did not help nor did I want it. Then I found some old quotes and everything changed. They fell in line with what I was learning from going through the Twelve Steps. I read in The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius “Such as are your habitual thoughts, such also will be the character of your mind; for the soul is dyed by the thoughts.” I identified with these sayings and realized that they were along the same lines as the principles I was learning in AA. So I looked up Marcus Aurelius and discovered he was an emperor of Rome. The words “Stoic philosopher” appeared next to his name. So I began reading up on the Stoics.

Frank’s embrace of Stoicism reinforced and expanded what he’d learned from the Twelve Step Program. He was now more focused on taking responsibility for his own actions, more philosophical about setbacks, and more contented with life.

I’ve come to learn that I control very little! However, Stoic and Twelve Step principles such as looking for opportunities to experience gratitude in everything that happens to me good or bad — amor fati or “love of one’s fate” — have helped put me on the path of living happy joyous and free.

(Frank’s blog article Gratitude in my Attitude goes into more detail about his personal journey and Stoicism.)

Stoicism and AlcoholismSo what did the ancient Stoics have to say about alcohol and addiction? Well, the Stoics trained themselves to develop the virtue of temperance by practising various psychological techniques on a regular, often daily, basis. For example, they would often make an effort to describe things to themselves in very matter-of-fact language, like an ancient natural philosopher making observations about animal behaviour or a physician describing the symptoms of a disease. Stripping away emotive language and strong value judgments allowed them to retain a stronger grip on reality, which Stoics called having an “objective representation” (phantasia kataleptike).

When Marcus Aurelius gazed upon a bottle of the exquisite Falernian wine, therefore, he would remind himself that it was merely fermented grape juice, and that the fine meat dishes set before him were just the corpses of fish, birds, and pigs (Meditations, 6.13). We should strip away all the verbal embellishments that cloud our judgement of the things we desire and view the naked truth with total objectivity. Napoleon employed the same down-to-earth strategy by saying that a throne is merely a bench covered in velvet.

I think Stoicism appeals to many people who struggle with alcoholism because it offers more than just self-help advice. The language in which it’s expressed in the classics is often striking, beautiful, and memorable. These stories from ancient philosophy stick in people’s minds and their constant presence can help us to gradually find a new orientation in life whereas sound advice from modern self-help books is often more forgettable. Stoicism isn’t just a therapy, either, but a whole philosophy of life. People who embrace it find that it can give them the opportunity to recover a sense of purpose and direction in life, and in some cases that can help fill a void that they’d previously been using drugs or alcohol to conceal from themselves.

Most importantly, though, Stoicism is a philosophy that contains a call to action. The Stoics wanted us to apply reason to our lives, and engage in philosophical discussions about the meaning of life, but only insofar as it actually helps us to improve our characters. We also have to make decisions, arrive at conclusions, and put wisdom into practice. As Marcus Aurelius said:

Waste no more time arguing about what it means to be a good man and just be one. — Meditations, 10.16

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

September 7, 2023

Rejoice only in what is your own

CommentaryBe not elated at any excellence which is not your own. If the horse in his elation were to say, “I am beautiful,” it could be endured; but when you say in your elation, “I have a beautiful horse,” rest assured that you are elated at something good which belongs to a horse. What, then, is your own? The use of external impressions. Therefore, when you are in harmony with nature in the use of external impressions, then be elated; for then it will be some good of your own at which you will be elated.

September 3, 2023

Marcus Aurelius on Stoicism and Leadership

The Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius was the most famous proponent of the ancient philosophy known as Stoicism. He was also one of the most powerful leaders in European history, assuming control of the Roman empire aged 39, during the height of its power. Marcus had completed a longer apprenticeship than any of his predecessors, serving 23 years as Caesar, the appointed successor and political deputy of his adoptive father, the emperor Antoninus Pius.

Indeed, Antoninus granted Marcus a share in most of the imperial powers, in 147 CE, the day after his first child was born. Marcus was not yet granted the title Augustus, although his wife, Faustina the Younger, had already been named an Augusta (similar to an empress) by her father. Marcus was named imperator, giving him supreme command of the army, and granted the “tribunician power”, which meant he had imperial authority over the Roman Senate. Marcus was effectively co-emperor, in all but name, for the last 14 years of Antoninus Pius’ rule, in addition to the 19 years he ruled as Augustus himself. Marcus Aurelius, therefore, knew something about what it took to be a successful Roman emperor.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

This article explores the five key leadership qualities that Marcus talks about admiring:

Develop your character

Be hardworking and conscientious

Don’t over-value praise

Don’t be afraid of criticism

Be content to live simply

Marcus’ rule as emperor was notoriously challenging. After a period of exceptional peace and stability during the rule of his adoptive father, Marcus faced a series of disasters. Shortly after he was acclaimed emperor, the River Tiber suffered one of its most severe floods ever, destroying homes and livestock, which led to a famine at Rome. Around this time, the Parthians invaded Armenia, a Roman ally, instigating a war in the east that would last five years.

Rome’s eventual victory in the Parthian War was soured when returning legionaries spread a deadly virus throughout the empire. The Antonine Plague took the lives of an estimated five million people, over the course of roughly fifteen years. To make matters worse, while the empire was struggling to recover enemy tribes along the northern frontier seized the opportunity to invade. The young King Ballomar of the Marcomanni led a vast army, which overran Pannonia and the other northern provinces. They proceeded to loot and plunder their way down the Amber Road, across the Alps, and into Italy itself, finally laying siege to the wealthy Roman city of Aquileia.

I admire him all the more for this very reason, that amid unusual and extraordinary difficulties he both survived himself and preserved the empire.

Marcus nonetheless faced these unprecedented challenges head on, with total Stoic equanimity and endurance. The Roman historian Cassius Dio could therefore conclude:

[Marcus Aurelius] did not meet with the good fortune that he deserved, for he was not strong in body and was involved in a multitude of troubles throughout practically his entire reign. But for my part, I admire him all the more for this very reason, that amid unusual and extraordinary difficulties he both survived himself and preserved the empire.

After the sudden death of his adoptive brother and co-emperor, Lucius Verus, Marcus was unexpectedly left in sole command of the army. Rather than run the war from behind a desk back in the safety of Rome, he donned the military cape and boots and rode forth to battle. Indeed, Marcus stationed himself in the military camps along the front line throughout the Marcomannic War, in modern-day Austria, Hungary, and Serbia. With no military experience whatsoever, he found himself at the head of the largest army ever deployed on a Roman frontier, numbering approximately 140,000 men in total.

During this time Marcus wrote down his personal reflections on Stoic philosophy in a text that would later become known as The Meditations, one of the most influential spiritual and self-help classics of all time. Marcus opens the book with a chapter written in a different style from the rest. He lists the virtues or qualities he most admires from about sixteen different people: teachers or members of his family. In doing so, he was clearly attempting to study attitudes and behaviours worth emulating.

The MeditationsAt the time of writing, Marcus had known three other Roman emperors in person: Hadrian, his adoptive grandfather; Antoninus Pius, his immediate predecessor and adoptive father; and Lucius Verus, his adoptive brother and junior co-emperor. It’s notable that Marcus virtually relegates Lucius Verus to a footnote, almost as though damning him with faint praise. Hadrian gets even worse treatment and is completely ignored, as though Marcus can’t think of anything positive to say about him at all. However, these omissions are all the more apparent because of the way Marcus heaps praise at length upon Antoninus Pius, his adoptive father and predecessor as emperor. Not only does he expend spend far more words on Antoninus here than on any other individual but Marcus returns to him later in the text, providing another list of his virtues and stating quite categorically that he views himself as the “disciple of Antoninus” in all matters.

Marcus, in other words, was carefully modelling the leadership qualities he saw exemplified in the emperor Antoninus Pius.

We also have a letter addressed to a young Marcus from his celebrated Latin rhetoric tutor, Marcus Cornelius Fronto, in which Fronto advises Marcus on writing speeches in praise of the Emperor Antoninus, who was still alive at the time. Marcus, he says, should thank his father eloquently and “be most full and copious”,

For there is nothing that you can say in all your life with more honour or more truth or more liking than that which concerns the setting forth of your father’s praises.

It’s crystal clear that, even a decade or more after his demise, Marcus was still turning to his adoptive father’s memory to find a guide and role model, particularly in relation to his duties as emperor. Marcus, in other words, was carefully modelling the leadership qualities he saw exemplified in the emperor Antoninus Pius. Although Antoninus wasn’t a Stoic, Marcus saw him as naturally embodying the sort of virtues Stoics wanted to cultivate. This seems to have been a common practice. For example, Seneca had earlier written:

We can remove most sins if we have a witness standing by as we are about to go wrong. The soul should have someone it can respect, by whose example it can make its inner sanctum more inviolable. Happy is the person who can improve others, not only when present, but even when in their thoughts! (Moral Letters, 11.9)

I’ve combed through the various remarks Marcus makes about the traits in his father he most admired and discovered that they fall under a handful of broad headings. We can view these as some of the characteristics Marcus associated with the ideal leader or ruler.

1. He had equanimity and a pleasant characterMarcus mentions that he admired the emperor Antoninus Pius for being mild tempered. He became very famous for the air of serenity that accompanied his presence. Hadrian, by contrast, was notoriously volatile and quick tempered . He made people nervous and they were afraid to tell him bad news. As with other tyrants, over time, Hadrian increasingly became paranoid and feared perhaps sometimes with justification, that he he was surrounded by conspirators.

Marcus tells us that he suffered from a temper himself, which he struggled to control, so it’s tempting to imagine that he wanted to be more like Antoninus and less like Hadrian in this regard. Marcus also said that Antoninus always seemed to be cheerful and satisfied with life. He therefore came across as very natural and agreeable in conversation. Marcus described his adoptive father very “sweet-natured”. People trusted Antoninus and found it easy to talk to him. Marcus noted that, compared with Hadrian, Antoninus kept very few secrets and those he did concerned matters of state. He perceived him as a genuinely pious man, while nevertheless above superstition. He had a calm and reassuring presence and it was pleasant dealing with him. It may surprise many people to know that Stoics, like Marcus, were often cheerful and pleasant company.

2. He was patient, hardworking and conscientiousAntoninus would research his decisions meticulously beforehand, minimizing the likelihood he’d have to change course at a later date. He’d therefore find himself able to stick to his original plan of action more consistently than other rulers. He wasn’t content with a superficial understanding but sought to think through his decisions very carefully, even anticipating events in the distant future. Marcus says his adoptive father would usually examine the problems he faced one aspect at a time as if he had ample time, proceeding vigorously and in a focused, organized, and determined manner. He would never allow an important decision to be made until he was satisfied that he’d given it enough thought to understand what was at stake. Once he’d determined the most rational course of action, though, he would act accordingly, ensuring that it was put into practice. He seemed to enjoy working and was therefore able to labour patiently at things for long hours, even returning to work immediately after recovering from severe bouts of headache.

He was also very prudent and conscientious in managing both his own affairs and those of others, and careful to avoid wasting public money. He was cautious about putting on crowd-pleasing spectacles or constructing public buildings. He sincerely respected the institutions of his country. He wasn’t desperate for change, for its own sake, but content to remain in the same place, working consistently on the same tasks. This was quite the opposite of Hadrian who constantly travelled and sought novelty and stimulation. Marcus admired this because Stoicism teaches us to value strength of character, and virtue, first and foremost. That leads to a hard-working attitude because taking pride in what you do is more important than avoiding discomfort.

3. He neither flattered others nor sought to win praise himself

3. He neither flattered others nor sought to win praise himselfMarcus said that Antoninus helped cure him of pride and affectation and showed him that he could live in a palace almost as if he were a common citizen, minimizing the trappings of imperial office. Antoninus was neither pretentious nor pursued acclaim. He was above flattery himself and put a stop to it at court. He didn’t try to win popularity by heaping praise on others or showering them with gifts. He had a natural lack of interest in empty fame and instead focused on doing what was actually required rather than what would win him admirers.

However, he showed loyalty and consistency in his friendships. He sought genuine friends rather than being seduced into flattering others to win fairweather friendships. He treated people justly, giving them what they deserved, and never imposed unreasonable demands on his companions. This indifference to flattery was integral to the Stoic philosophy followed by Marcus Aurelius. It’s easy to be mesmerized and lured off course by fame but the wise person remains aloof from these things and committed to doing what reason determines to be the right course of action.

4. He was unafraid of criticismAntoninus didn’t consider himself superior to anyone and was happy to listen to whoever had potentially useful information or advice. Nevertheless, he would very carefully study the manners and actions of others to determine their character. He honoured true philosophers, but was not easily led by pseudo-intellectuals. He was ready to give way to experts on matters of law or ethics, or those who were more skilled speakers, without any envy or resentment, and he helped competent individuals to advance in their careers. Moreover, Antoninus never listened to slanderous gossip and didn’t indulge in idle complaints about others himself. Marcus was impressed by how his adoptive father tolerated freedom of speech in those who opposed his opinions and, indeed, rather than being indignant he was extremely pleased whenever anyone could show him a better way of looking at things.

“It is kingly to do good and yet be spoken of ill.”

Antoninus was therefore neither timid nor aggressive; neither a sloppy thinker, like the Sophists, nor a pedant. He would challenge other people’s views where necessary but was also willing and able to accept criticism from others. For example, Marcus says his adoptive father endured a considerable amount of criticism for being too cautious with regard to public expenditure, etc. He patiently put up with individuals who blamed him unjustly without blaming them in return. In The Mediations, Marcus quotes an old saying from Antisthenes: “It is kingly to do good and yet be spoken of ill” (7.36). In his play Hercules Furens, the Stoic philosopher Seneca likewise wrote “’Tis the first art of kings, the power to suffer hate.” A truly wise leader, in other words, must be able to ignore insults and be tolerant of criticism.

5. He was content with simple things in lifeMarcus was impressed by how little was necessary to satisfy Antoninus, in terms of his lodgings, bed, dress, food, servants, etc. He looked after his own health in a simple down-to-earth way, without becoming overly-preoccupied with diet or exercise. When he had access to luxuries he enjoyed them without any reservations but when he didn’t have them he didn’t want them. Marcus says that like Socrates, Antoninus was able both to abstain from, and to enjoy, those things which many are too weak to abstain from and cannot enjoy without excess. However, to be strong enough both to bear abstaining from desires and yet sober enough to enjoy satisfying them without excess is the mark of a perfect and invincible soul, he says. In other words, this sort of moderation and self-discipline was integral to Stoic philosophy and its conception of leadership.

Socrates himself had long ago made the point that, on reflection, nobody with any sense would rather entrust the care of their loved ones to someone reckless who lacks self-control than to someone self-disciplined and moderate. He concluded that these are obviously traits we should desire in any leader because it’s impossible to act consistently in accord with wisdom if we lack self-control. Marcus clearly saw Antoninus as embodying the sort of self-mastery required for a leader to live consistently in accord with wisdom and justice.

The Historia Augusta portrays the emperor Antoninus’ character as a ruler in a way that’s broadly consistent with Marcus’ personal notes on him in The Meditations:

In personal appearance he was strikingly handsome, in natural talent brilliant, in temperament kindly; he was aristocratic in countenance and calm in nature, a singularly gifted speaker and an elegant scholar, conspicuously thrifty, a conscientious land-holder, gentle, generous, and mindful of others’ rights.

It adds that he “possessed all these qualities, moreover, in the proper mean and without ostentation”, and was praiseworthy in every conceivable respect. Moreover, “for three and twenty years [Marcus Aurelius] conducted himself in his [adoptive] father’s home in such a manner that [Antoninus] Pius felt more affection for him day by day, and never in all these years, save for two nights on different occasions, remained away from him”. By all accounts, therefore, Antoninus was both an excellent father and a role model to Marcus, especially in his capacity as a leader and the emperor of Rome.

See my book, How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, for a more in-depth discussion of Marcus Aurelius’ life and use of Stoic philosophy.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

August 31, 2023

Video: Stoicism, Psychotherapy, and Self-Help

I recently recorded this conversation with Greg Sadler, of Modern Stoicism, about problems that can arise when using Stoicism for self-help and how it relates to what we know from research in psychotherapy.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.