Donald J. Robertson's Blog, page 35

February 5, 2023

Why is Marcus Aurelius Called Verissimus?

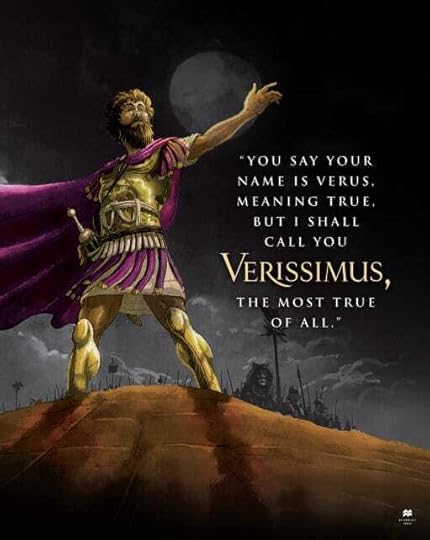

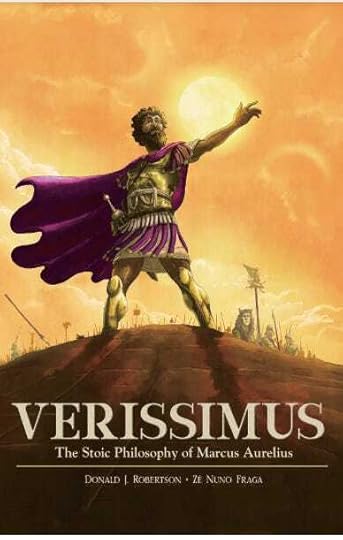

Check out our graphic novel, Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, available now from St. Martin’s Press. It was chosen as an Amazon Editor’s Pick for Best History Book, and has an average 4.8 star rating from nearly 200 Amazon readers. The article below was written to explain the name in the title, which may be unfamiliar to many readers.

You’ve probably heard of Marcus Aurelius, the Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher. He’s the author of The Meditations, one of the most popular self-improvement classics of all time. Even if you’ve not read that book, maybe you saw Richard Harris playing him in the first act of the Russell Crowe movie Gladiator (2000).

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Did you know that Marcus was also called Verissimus, though? This name means “most true” in Latin. It’s confirmed by at least three or four ancient sources. and seems to have caught on, in part, because it naturally suited his reputation as a philosopher, and a lover of wisdom.

Marcus Annius Verus

Marcus Annius VerusFirst let me explain a bit more about his original name. Roman names are notoriously confusing, especially those of emperors, which often change several times during their lives. Marcus was born into a Roman family or gens known as the Annii, more specifically to a branch called the Annii Veri. His father, who died from unknown causes when Marcus was small, perhaps four years old, was called Marcus Annius Verus. The son was given the same name as the father. So our Marcus Aurelius was actually called Marcus Annius Verus as an infant.

Marcus Aurelius is never referred to simply as “Aurelius”, his adoptive family name.

Later, when Marcus was adopted by the emperor Antoninus Pius, he was renamed Marcus Aelius Aurelius Verus. When he succeeded Antoninus and was acclaimed emperor himself he became Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, having adopted the family name and cognomen of his predecessor Antoninus Pius. Today we usually just know him as Marcus Aurelius, although during his rule as emperor he would be officially addressed, normally, as Antoninus, or using his imperial titles: Imperator, Caesar, and Augustus. Hence, he writes in his notes to himself:

But my nature is rational and social, and my city and country, so far as I am Antoninus, is Rome, but so far as I am a man, it is the world. — Meditations, 6.44

Marcus Aurelius, is never referred to simply as “Aurelius”, incidentally, his adoptive family name. Scholars usually just refer to him as “Marcus”, following the convention that sovereigns are known by their first name, i.e., we don’t refer to Emperor Napoleon simply as “Bonaparte” or to Queen Elizabeth as “Windsor”.

Artwork from the forthcoming graphic novel, Verissimus. Copyright D. Robertson.The Origin of Verissimus

Artwork from the forthcoming graphic novel, Verissimus. Copyright D. Robertson.The Origin of VerissimusSo how did Marcus come to be known as Verissimus and what does it mean? We have several sources attesting to this name but the most helpful is the Roman historian Cassius Dio. He claims that Emperor Hadrian, who knew Marcus as a boy, took a shine to him, after his father died, viewing him as a potential successor “because he was already giving indication of exceptional strength of character.” Dio adds:

This led Hadrian to apply to the young man the name Verissimus, thus playing upon the meaning of the Latin word. — Cassius Dio

This was at the time when Marcus, as a child, went by his family name Marcus Annius Verus. Hadrian, who fancied himself a poet, and enjoyed wordplay, was upgrading the name Verus, which means “true”, to Verissimus meaning “truest” or “most true”. If only we knew why he came up with this pun!

Perhaps young Marcus said something remarkably truthful and honest in the emperor’s presence. However, it can also mean “most appropriate”, so it could be, given the context, that Hadrian was hinting that he saw Marcus as the most fitting successor to the throne. Nevertheless, as we’ll see, the name certainly became associated with Marcus as a philosopher in adulthood, where it must have been interpreted as meaning that he was known for being markedly truthful, or a lover of truth.

As an aside, there’s something I find quite odd about this nickname. Modern readers tend to underestimate how important subtle wordplay was to educated Romans of this period. Hadrian lived during a cultural movement called The Second Sophistic, which celebrated the art of rhetoric. Intellectuals at Rome, of whom Hadrian considered himself one, relished good puns. Master rhetoricians were also adept (much more than we typically are today) at insinuating digs or criticisms. Although Marcus’ father was dead, his grandfather, also named Marcus Annius Verus lived on for some time, and Marcus was actually raised for a while in his household. He was one of the most senior statesmen in Rome, a triple consul, and a friend of Hadrian. By calling Verus’ grandson “Verissimus” was Hadrian implying that the young boy was truer and the elder statesman less true by comparison?

Artwork from the forthcoming graphic novel, Verissimus. Copyright D. Robertson.

Artwork from the forthcoming graphic novel, Verissimus. Copyright D. Robertson.This verbal contrast between Verus and Verissimus became even more awkward once Marcus himself was acclaimed emperor. He took his adoptive brother, and son-in-law, Lucius Verus, as co-emperor. So Rome had two emperors, known as Verus and Verissimus or “True” and “Truest”. As though one ruler was good but the other was better! In taverns across the empire, surely, this must have led to jokes at Lucius’ expense. He was clearly the subordinate in this relationship, a second-rate emperor.

Marcus had a favourite son who bore his own original name Marcus Annius Verus. This child was appointed Caesar, along with his older brother Commodus, presumably with the intention that they would rule jointly. However, he died tragically, when he was around six years old, during an operation to remove a tumour growing behind his ear. The Roman historian Herodian, who lived during the rule of Commodus, says that at some point in his short life this boy Caesar was also given the nickname Verissimus, like his father, Marcus Aurelius.

A later Roman historian, in the Historia Augusta, confirms that Marcus himself bore this name by writing that after the death of his father, “Hadrian called him [Marcus] Annius Verissimus” as opposed to Marcus Annius Verus. In a subsequent passage it reiterates that Marcus was “reared under the eye of Hadrian, who called him Verissimus, as we have already related.”

Regarding his character as emperor, the Historia Augusta says of Marcus:

He did not readily accept the version of those who were partisans in any matter, but always searched long and carefully for the truth.

As we’ll see, this love of truth was an aspect of Stoic philosophy that Marcus took to heart and in his private notes, in The Meditations, we can perhaps see him musing somewhat about the meaning of his family name, Verus or True.

Truth in The MeditationsAt one point, in The Meditations, he refers, albeit somewhat figuratively, to having assumed the names of certain virtues, including true.

When you have assumed these names, good, modest, true, rational, a man of equanimity, and magnanimous, take care that you do not change them; and if you should lose them, quickly return to them. — Meditations, 10.8

The word he uses here is alethes as he’s writing in Greek not Latin. Nevertheless, he clearly knew that this could be viewed as a translation of his family name, Verus.

Indeed, throughout The Meditations we can find numerous references to the love of truth. For instance:

If it is not right, do not do it: if it is not true, do not say it. — Meditations, 12.17

At one point he goes so far as to equate truth with the divine Nature of the universe:

This universal Nature is named truth, and is the prime cause of all things that are true. He then who lies intentionally is guilty of impiety, inasmuch as he acts unjustly by deceiving. And he also who lies unintentionally, inasmuch as he is at variance with the universal Nature, and inasmuch as he disturbs the order by fighting against the nature of the world. — Meditations, 9.1

In this passage, he equates truthfulness with piety, typically for a Stoic, almost turning philosophy into a kind of mystical religion.

Verissimus the PhilosopherThat brings me to one final reference. Around 156 CE, during the rule of Antoninus Pius, the Christian author Justin Martyr wrote an open letter called The First Apology. Justin begins the letter by addressing the emperor as follows, using his full imperial title:

To the Emperor Titus Ælius Adrianus Antoninus Pius Augustus Cæsar, and to his son Verissimus the Philosopher, and to Lucius the Philosopher, the natural son of Cæsar, and the adopted son of Pius, a lover of learning, and to the sacred Senate, with the whole People of the Romans… — Justin Martyr, First Apology

Artwork from the forthcoming graphic novel, Verissimus. Copyright D. Robertson.

Artwork from the forthcoming graphic novel, Verissimus. Copyright D. Robertson.It may seem peculiar to call Lucius Verus a philosopher, but he was studying philosophy under some of the same Stoic teachers as Marcus around this time. More importantly, though, Marcus is here clearly referred to as “Verissimus the Philosopher”. In fact, Justin assumes that it’s perfectly sufficient to use this name alone in order for his own readers, the Senate, and the emperor, to know that Marcus Aurelius is intended.

So it wasn’t just a childhood nickname given to Marcus Annius Verus by Hadrian. Apart from the fact that it became well-known enough to be recorded by Roman historians, we can see from Justin’s letter that Marcus was still being addressed as Verissimus later in life, as Caesar, probably in his mid thirties.

I think Marcus thoroughly owned his childhood nickname, which become synonymous with his philosophy of life.

If you hold to this, expecting nothing, fearing nothing, but satisfied with your present activity according to nature, and with heroic truth in every word and sound which you utter, you will live happily. And there is no man who is able to prevent this. — Meditations, 3.12

It seems to me that this nickname became permanent, Verus became Verissimus, the true became the truest, in the eyes of the Roman people, and all subsequent generations, precisely because of this remarkable commitment to “embracing heroic truth in every word and sound you utter.”

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Check out our graphic novel, Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, available now from St. Martin’s Press. It was chosen as an Amazon Editor’s Pick for Best History Book, and has an average 4.8 star rating from over 150 Amazon readers.

February 4, 2023

How Socratic is Modern Stoicism

This is a clip from a recent conversation I had for the Stoa app, in which I was asked whether Modern Stoics were Socratic enough.

I think, first of all, that most people who study Stoicism read modern self-help books and articles, the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, and maybe Seneca or Epictetus, but they often don’t read many modern academic books or delve deeper into the classics. In particular, the ancient Stoics appear to view Socrates as one of their most important influences. Epictetus repeatedly holds up Socrates to his student, in fact, as their supreme role model. Yet there’s not really much discussion today of what modern Stoics can learn from the Socratic dialogues of Plato and Xenophon.

(If you’re interested in learning more about Socrates, by the way, check out my , or my four-week intensive course .)

Reading about SocratesIn my opinion, if you’re interested in Stoicism, and you’ve been reading Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius, you can probably also benefit a lot by reading Plato and Xenophon. (Of course, you can also expand your knowledge of Stoicism a lot through other ancient sources, such as Cicero, Plutarch, and other surviving Stoic texts, like the lectures of Musonius Rufus, or fragments, such as those found in Diogenes Laertius.) I hesitate to recommend specific texts because I know everyone’s needs are different. However, in my opinion, pretty much everyone should read Plato’s Apology. Why? Well, because it’s a masterpiece, and it also happens to be relatively short and easy to read.

The Apology is one of the most dramatic of Plato’s works because it deals with the trial of Socrates and his (notoriously unapologetic) defense speech. You could read it in a few hours. It’s one of the most important philosophical texts in the Western canon. (Personally, I think it’s the most important text in the Western canon.) In my experience, it’s also useful for those who are into Stoicism to read the first book of Plato’s Republic. The Republic, Plato’s magnum opus, is also one of his longest and most technical works, unfortunately. It’s ten books long, so roughly ten times the length of his shorter dialogues. However, scholars have traditionally felt that book one was written earlier than the rest. It feels like a self-contained dialogue, it’s more down-to-earth, more dramatic, and generally easier to read than much of what follows. So I tell people just to read that by itself, and maybe leave the rest of the Republic for later.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I would also recommend reading the Memorabilia and Apology of Xenophon, our other main source for information on Socrates. The Stoics appear to be as influenced by Xenophon as they were by Plato and their understanding of Socrates, I suspect, was probably closer to that of Xenophon, as they rejected the metaphysical and political views of Plato. I would also advise reading book two of Diogenes Laertius’ Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, at least the chapters dealing with Socrates and his followers. This is much later source but it’s easy to read and provides an interesting overview of the life and thought of Socrates, and his influence on the tradition that followed. Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, had studied Plato’s dialogues, but also the Memorabilia of Xenophon, and the teachings of other philosophers of Socrates, known as the Megarian school. It’s likely he was also influenced by the writings of Antisthenes and other Socratics.

Thinking Like SocratesIn the clip, I talk about how the surviving Stoic texts focus on moral precepts rather than philosophical arguments. That’s probably a historical accident. There were many ancient Stoic teachers and authors, we know the names of roughly sixty or seventy, and they were often prolific writers. Chrysippus alone, the greatest intellect of the school, reputedly wrote over 700 texts, none of which survive today. At a rough estimate, we maybe have less than one percent of the original Stoic texts, surviving today.

With regard to the central teachings of the philosophy that’s not as much of a problem as it might seem, as they make it fairly clear what Stoics believed — the doctrine that virtue is the supreme good is, e.g., repeated many times. However, it does leave us with a skewed impression of what Stoics studied in general. For example, we know that ancient Stoics typically spent a lot of time reading and learning about logic and nature (ancient physics) as well as ethics.

I think one of the main things we miss out on today is an appreciation of the role of dialectic and the Socratic Method in ancient Stoicism. (Dialectic refers generally to the process of philosophical debate and the Socratic Method is one of its most important forms.) The Stoics were philosophers, first and foremost, and they stood squarely in the Socratic tradition. We can see, for example, that Epictetus sometimes employed the Socratic Method with visitors to his school, and he talks about the extensive studies in logic undertaken by his students. We even find little fragments of Socratic dialogue in the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, such as the following:

Socrates used to say: What do you want, souls of rational men or irrational? – Souls of rational men. – Of what rational men, healthy or wretched? – Healthy. – Why then do you not seek for them? – Because we have them. – Why then do you fight and quarrel? — Meditations, 11.39

Nobody wants to sacrifice their mental health or ability to reason clearly. Yet we squabble, and don’t take this as a warning sign that we’ve lost the very thing we claim to cherish the most. Although this fragment is nowhere else attested in the surviving literature, it certainly sounds like the type of contradiction that Socrates loved to point out. (We can’t be sure but it’s possible this is a quote from an early Socratic dialogue, perhaps quoted in one of the lost Discourses of Epictetus, which we know Marcus had read.)

How do we, modern students of Stoicism, learn to think like Socrates and actually do philosophy? I think that one route comes from reading the surviving Socratic dialogues, as long as we then take onboard the lessons they contain about critical thinking and the Socratic Method. I think the simplest way I can express this is to say that Socrates, I suspect throughout his adult life, was the sort of person who was adept at spotting contradictions. This is really the essence of his entire method, in my opinion. If you said to Socrates “I believe that pleasure is the goal of life”, or any such thing, he would respond as if to say “Yes but…”, and either point out some simple observation that didn’t sit well with your theory or something you’d already said that conflicted with it on closer inspection.

Socrates would often invite his acquaintances to define an important concept they were discussing, usually a virtue such as wisdom or justice. He’d then proceed to brainstorm, as we put it today, examples of the concept that appear to constitute exceptions and contradict the definition. For instance, in one of Xenophon’s dialogues, Socrates begins from the premise that lying is a form of injustice. However, he proceeds to bring up the example of an elected general lying to the enemy during warfare. Put crudely, it’s as though he wants his companions to respond by saying “Oh yeah, I guess you’ve got a point, I hadn’t thought of that!”

This process of spotting examples that his partners agrees contradict what they just said is continued, with the original definition being revised along the way. For instance, his young friend in this dialogue, Euthydemus, adopts the revised definition that justice consists in telling the truth to friends but lying to enemies. Socrates, once again, comes up with an exception that conflicts with this. Suppose, he says, your friend is out of his mind with depression, and suicidal, and asks you where he can find a knife to kill himself? Would it still be unjust to lie to a friend under these circumstances? And so the process continues. We’re obviously doing philosophy now or rather the philosophical process known as dialectic.

That’s what’s missing from modern self-help literature on Stoicism, though. Without it, ancient Stoicism potentially becomes even more dogmatic than it was intended to be as principles are accepted on the basis of intuition rather than reason. (Hopefully nobody really accepts the ideas of ancient Stoics today purely on the basis of their personal authority, though.) I think we lose some important psychological benefits of Stoicism if we abandon their use of dialectic, though. We can benefit from learning about modern formal and informal logic, particularly being able to spot logical fallacies. However, I think the best foundation for incorporating Stoic logic into our studies is simply to begin with the Socratic Method, and the practice of identifying logical contradictions in our own thinking and that of others.

(If you’re interested in learning more about Socrates, by the way, check out my , or my four-week intensive course .)

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

⏳ Live Like Socrates: Last Chance to Register!

Utere non reditura.

Use the hour, it will not come again.

This is it – the last few hours to join !

As of midnight Pacific time tonight, the course will closed. Remember, if you enroll via these links, you'll also be receiving $50 discount off the standard price. You can also get the same discount if you choose the !

By joining today you’ll get access to any future updates or improvements, via lifetime course access – the course is just going to keep on getting better.

One of the great things about Donald Robertson's courses is that they never end. They are available to us forever (or at least as long as Donald is able to keep them posted). As with "How to think like a Roman emperor" I will be going back to this course when the spirit moves me. Each time I will discover something new. In the process of learning more about Socrates I learned more about me. Would I recommend this course? Yes, without hesitation. If you find it a bit much to "complete" in four weeks (I did) don't worry. The material is there and the instructor is wonderfully accessible. – Wilfred Allan

Are you ready to join me in ?

Thanks once again for your support and feedback, and I look forward to seeing you in person in the course!

Warm regards,

Donald Robertson

PS. If you're interested but have questions, please feel free to reply to this email. (I get loads of emails from people about courses and answer all of them personally.)

February 3, 2023

Time is Running out to Join How to Live Like Socrates!

Tempus breve est.

Time is short.

I just wanted to send a quick reminder that enrolment for How to Live Like Socrates will be closing tomorrow at midnight Pacific Time, so don't miss your chance to take part.

If you haven't already joined the course, here's why you should consider giving it a go...

Discount. You'll be receiving a special discount as a newsletter subscriber. I've taken $50 off the price for the standard course, including webinars.

Payment Plan. I've added a , so it's now possible to split payments across three monthly instalments!

Improvements. You'll have ongoing access to the course as long as it's available, including any future additions or improvements you might suggest.

Bonus Resources. I've bundled in 3 online resources for you: The Life and Opinions of Socrates, Socrates HD Wallpapers, and Crash Course on Socrates

Interact and Learn with Others. Get the chance to interact with and learn from other participants as well as take part in weekly webinars. On my last course the students shared nearly five hundred comments discussing the content.

Learn from an Expert. You'll be taking a course run by someone who's published four books on Greek philosophy, plus another three chapters in edited collections of articles on the subject.

If now’s not the right time for you then no problem, you’ll still be able to join when it opens again next time - I usually open it once or twice a year. If you’re just not sure if the course is for you, then don’t forget I offer a risk free 30-day money-back satisfaction guarantee. Hope to have you join me!

Warm regards,

Donald Robertson

PS. If you haven't already, check out the sneak peek at my video!

February 2, 2023

Stoicism as a Philosophy of Life

This is my attempt to provide a short and simple introduction to Stoic practices, which anyone can begin using right away. It includes:

Brief introduction to Stoicism and dispelling the most common misconceptions

Two basic concepts:

The dichotomy of control

That it’s not things that upset us but rather our judgments about them

Three basic practices:

Objective description

Contemplating virtue and the double-standards strategy

The view from above

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The original article on which this audio recording is based can be found on Substack, Stoicism as a Philosophy of Life. Check out my books Stoicism and the Art of Happiness and How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, for more advice on applying Stoicism in daily life.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Live Like Socrates: Take a Sneak Peek

I'd like to thank everyone who's reading these emails and supporting the launch of my online course, . Your feedback and suggestions have already been absolutely invaluable and I've done my best to make the course even better in the last few days before enrollment closes.

For single-payment pricing, including your special discount:

For payments split over three months:

(These links will automatically apply your discount.)

You can get a special preview of one of the course intro videos below. It's about 10 minutes and explains briefly why I chose Socrates to be the focus of the course content:

Warm regards,

Donald Robertson

February 1, 2023

🎁 How to Live Like Socrates: Special Discount + Bonuses!

Surprise! I have not one but three extra-special bonuses for you if you today!

With the help of my colleagues, Paul Summers Young and Rocio de Torres, I've created three online resources for you on the life and philosophy of Socrates:

The Life and Opinions of Socrates - based on excerpts from Diogenes Laertius on the life of Socrates, Xenophon, Antisthenes, Aristippus and Plato

Socrates HD Wallpapers - some high-definition desktop wallpapers with quotes from and images of Socrates

Crash Course on Socrates - my fifteen minute introduction to Socrates

These three resources are all bundled with the course . There's no extra charge! I've added these to the course for everyone enrolling now.

If you want to across three monthly installments, you can do so and still receive your $50 special discount as a loyal subscriber to my newsletter. If you change your mind, just request a refund under the 30-day satisfaction guarantee. It's totally risk free.

All of the links in this email will automatically apply your $50 special discount coupon, as a reward for subscribing to my newsletter.

As always,thanks for your support!

Warm regards,

Donald Robertson

January 31, 2023

The Virtue of Being Wrong

And what kind of man am I? One of those who would be pleased to be refuted if I say anything untrue, and who would be pleased to refute anyone who says anything untrue; one who, however, wouldn’t be any less pleased to be refuted than to refute. For I count being refuted a greater good, insofar as it is a greater good to be rid of the greatest evil from oneself than to rid someone else of it. I don’t suppose that any evil for a man is as great as false belief about the things we’re discussing right now. — Socrates in Plato’s Gorgias

Nobody likes being wrong, we’re told. Least of all those individuals who suffer from pathological narcissism. They have to believe that they were right all along, even when it becomes obvious they are very much in the wrong.

Figures who live in the public eye, such as celebrities and politicians, if they become overly-incentivized by praise, risk turning this into a habit. As Aristotle once said, habits become our “second nature”. They solidify into character traits if we’re not careful.

Perhaps sometimes the person who gains the most is the one who loses the argument.

So do we always have to be right? The ancient Greek philosophers — who loved paradoxes — said the opposite: maybe true wisdom requires the capacity to delight in being proven wrong. My favourite expression of this idea comes from Epicurus:

In a philosophical dispute, he gains most who is defeated, since he learns the most. — Epicurus, Vatican Sayings, 74

How crazy is that? Perhaps sometimes the person who gains the most is the one who loses the argument. The one who wins the argument gains nothing, except perhaps some praise — but what does that matter? The one who loses, though, gains knowledge, and perhaps gets a step closer to achieving wisdom.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

It wasn’t Epicurus who first stated this paradoxical insight, though. Much the same attitude was characteristic of the famous method of Socrates, over a century earlier. In Plato’s Gorgias, for example, Socrates makes it clear that he’s no less happy to be proved wrong than to prove someone else wrong, and actually believes he comes off best by being shown his mistakes — it’s better, he says, to be saved, than to save someone else. He goes on to explain that if someone proves him wrong, he won’t get cross with them, even if they did with him. Instead, he jokes, he’ll make sure public records list that person as his greatest benefactor.

The Stoic school of philosophers, which was greatly influenced by Socrates, taught essentially the same thing. This article will focus on what one Stoic in particular, the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, said about the benefits of being proven wrong. (For a more in-depth discussion of Marcus’ life and philosophy, see my book How to Think Like a Roman Emperor.)

The Stoicism of Marcus AureliusMarcus Aurelius looked up to one man above all others: his adoptive father, the preceding emperor, Antoninus Pius. In his private notes, which we call The Meditations, Marcus carefully lists the qualities he most admires in Antoninus, despite the fact that by this time he had been dead for over a decade. Marcus does this more than once, in fact, and with such care, that I think it has all the hallmarks of an exercise that he’s engaged in repeatedly over the years.

If someone showed him he was wrong, rather than being offended, he was pleased.

We can think of this as Marcus’ attempt to study and emulate what today we would call the Emperor Antoninus’ leadership qualities. He tells himself to be, in every aspect of life, a student of Antoninus (Meditations, 6.30). It’s a fascinating analysis of the man’s character. However, for our purposes, I just want to draw attention to one of the things that Marcus says:

[Remember] how he would tolerate frank opposition to his views and was pleased if somebody could point to a better course of action. — Meditations, 6.30

Earlier in the book we find something related:

And most admirable too was his readiness to give way without jealousy to those who possessed some special ability, such as eloquence or a knowledge of law and custom and the like, and how he did his best to ensure that each of them gained the recognition that he deserved because of his eminence in his particular field. — Meditations, 1.16

In other words, although he was a hard-working and intelligent ruler, the Emperor Antoninus also had the wisdom to know when to listen to experts. Marcus admired this as an example of the man’s strength of character, self-awareness, and humility. If someone showed him he was wrong, rather than being offended, he was pleased. It didn’t hurt his pride or damage his ego, as we say today. Antoninus was a big enough man, and emotionally mature enough, not only to deal with criticism but to actively seek it out and welcome it as an opportunity for personal growth. That was one of the qualities which made him such an exceptional leader.

Stoic TherapyMarcus says that it was his Stoic mentor, Junius Rusticus, who first persuaded him that his own character required correction and even therapy. (Literally, he uses the Greek word therapeia.) He also tells us that he often became irritated or angry with Rusticus and was thankful that he never lost his temper with him over the years. Elsewhere, Marcus tells us that showing a man his moral faults is like telling him he has bad breath or body odour (Meditations, 5.28). People often don’t like hearing it and so there’s an art to communicating criticism effectively. It requires a delicate combination of honesty and tact. Rusticus was adept at this. Nevertheless, Marcus found that it required lifelong training to genuinely welcome plain speaking and criticism from others.

Marcus was probably about fifteen years old when he first met the philosopher Rusticus — there’s a hint that he may have a been a friend of his mother’s. Over three decades later, on the northern frontier, in the middle of the First Marcomannic War, Marcus was writing his famous Meditations. He’s still working on himself. He tells himself to always be ready to apply the following rule to any situation:

Be prepared to change your mind if someone is at hand to put you right and guide you away from some ill-grounded opinion. — Meditations, 4.12

Someone like Rusticus, although he’s now dead. Marcus adds, though, that this change of opinion should always be motivated by the belief that it is not only true but also serves justice and the common welfare. We should not, in other words, be swayed by others, such as the silver-tongued Sophists, merely because it feels easier to adopt a more popular opinion. As a leader, in particular, Marcus believes he should change his course of action when he’s persuaded that another way would actually be better for everyone.

We have a curious piece of evidence that Marcus meant this quite sincerely and had adopted this attitude from his youth. In a private letter to his rhetoric tutor, Marcus Cornelius Fronto, written when Marcus was aged about eighteen, he says:

I have received two letters from you at once. In one of these you scolded me and pointed out that I had written a sentence carelessly; in the other, however, you strove to encourage my efforts with praise. Yet I protest to you by my health, by my mother’s and yours, that it was the former letter which gave me the greater pleasure, and that, as I read it, I cried out again and again “O happy that I am!”

As we’ve seen, the Greek philosophers love paradoxes. Marcus knows that the majority of people think it’s a sign of weakness and subordination to acknowledge that someone else is right and you’re wrong. The Romans would have been tempted to say it’s slavish and, in their sexist way, they actually called Marcus an “old woman”. The powerful are always right, these men would say.

Marcus was the most powerful man in the known world, though, and he saw through this lie. He remembered that Antoninus, the greatest man he knew, welcomed criticism and was the first to change his mind when someone showed him he was wrong.

Remember that to change your mind and follow somebody who puts you on the right course is none the less a free action; for it is your own action, carried out in accordance with your own impulse and judgement, and, indeed, your own reason. — Meditations, 8.16

We enslave ourselves to external things and other people whenever we betray reason. True, absolute freedom would consist in doing what we know is right, regardless of the cost. Sometimes it takes courage to admit you’re wrong, and in that moment you’ve broken free. If you change your mind to please other people, sure enough, that’s a form of slavery. However, if it’s because you genuinely recognize that you were in error then the opposite is true — you’ve liberated yourself by admitting your mistake.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Got Questions About How to Live Like Socrates? We've got Answers…

He is nearest the gods who has fewest wants. – Socrates

Since my last email, I’ve received quite a few questions about , so I thought I’d answer them here in case you’ve been wondering the same thing.

Question 1: What if it’s not for me?If you're not totally happy, just email me within 30 days of purchase and I'll refund your fees in full, no questions asked. Enrollment in this course is absolutely risk free!

Question 2: How do I enroll?Just go to the course page, click the Enroll button, and follow the instructions. You can also just click the button below, which links directly to the enrollment page.

Question 3: How much does it cost?The course price is $149 USD - this includes your $50 discount, applied automatically if you click on the buttons or links in this email.

Question 4: Can I pay in installments?Yes, of course. There's a at the checkout, which gives you the option of splitting payments into 3 three monthly installments.

There are a lot of resources in it that I wouldn't be able to put into a book, like audio and video recordings, discussions, quizzes, infographics, exercises, and even some of the written content. It's based on the Socratic Method and examples from the life of Socrates, the quintessential Greek philosopher. The course is four weeks long, and each week includes a wide variety of high-quality elearning resources plus live webinars on how you can apply what you learn from Socrates in your own daily life.

Question 6: Is it self-paced?Yes, if you want it to be. There are weekly webinars but if you can't attend live you can just view the recordings in your own time, so you can treat it as a self-paced course because you'll have lifetime access to the content, including any updates or improvements.

I've really enjoyed this course, thanks for putting it together, and I've really enjoyed being able to move through it at my own pace looping back to the challenging exercises, putting it down when other commitments took more or my time and picking it up again when I could. I'd recommend it, no question. – Steve Powell

Hopefully that helps if you’ve had a few hesitations about joining me! However if your question isn’t answered here then reply to this email and let me know.

Or, if if you’re ready to join us. Don't miss the boat – we start in a few days!

Warm regards,

Donald Robertson

Thanks for being a valued newsletter subscriber. (As always, if you think you're receiving this email in error please click the unsubscribe link below.)

January 30, 2023

The danger of "little s" stoicism

I grant that [the Stoic Sage] is sensitive to these things, for we do not impute to him the hardness of a rock or of iron. There is no virtue in putting up with that which one does not feel. — Seneca, On the Constancy of the Sage

This is a clip from an interview that I did recently for the Stoa App. I’m talking about the problem of people confusing stoicism (lowercase), the unemotional coping style, with Stoicism (capitalized) the Greek philosophy. Ironically, people think of lowercase stoicism, or having a stiff upper-lip, as a way of being tough but research shows it’s actually, in a sense, the opposite — stoic individuals, far from being tougher and more resilient, are actually more emotionally vulnerable.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

There’s a growing body of modern psychological research that suggests lowercase stoicism, which consists in suppressing or concealing unpleasant or embarrassing emotions, leads to a number of problems. People who try to be “stoic” in this way are less likely to see a therapist or counsellor, or doctor, and less likely to seek emotional support from friends or family — which makes them more prone to difficulties and undermines resilience in the long-run. They also tend to use crude emotional coping strategies like trying distract themselves or suppress or avoid unpleasant emotions, which often backfires by forcing them to allocate more attention than normal to their inner turmoil, as if placing painful emotions under a magnifying glass. This can also lead to what psychologists call the “rebound effect” or “paradox of thought suppression” whereby trying too hard not to think or feel something has the opposite of the desired effect by causing it to recur more frequently in the future.

Photo by Ivan Aleksic on Unsplash

Photo by Ivan Aleksic on UnsplashThe Greek philosophy of “Stoicism”, by contrast, is the main philosophical inspiration for modern cognitive therapy, from which most of the strategies used in emotional-resilience training are actually derived. So there’s reason to believe that Stoicism is good for your mental health whereas stoicism is bad for your mental health — and those are two things you definitely wouldn’t want to confuse!

Stoic philosophy does not tell us to suppress our fears but rather to challenge the beliefs and values underlying them.

However, the Internet is awash with bad self-improvement and self-help advice that does precisely that, mixing up the Greek philosophy with the unemotional coping style named after it. These often give contrary advice about how to cope with emotions, though. Lowercase stoicism tells us to view our painful feelings as bad and to try to suppress them. Stoic philosophy tells us to accept the automatic feelings with indifference, and be unafraid of them, while taking more responsibility for our thoughts and beliefs in response to them, and questioning those philosophically, as a way of learning to cope. Stoic philosophy does not tell us to suppress our fears but rather to challenge the beliefs and values underlying them.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.

If you’re interested in going into this subject in more depth, check out my article The Difference between stoicism and Stoicism.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of LifeThe Difference between stoicism and StoicismAgainst being unemotional and the case for a “Passionate Stoicism” I do not withdraw the wise man from the category of man, nor do I deny to him the sense of pain as though he were a rock that has no feelings at all. — Seneca, Letters, 71 Stoicism has become a quite trendy over the past …Read more2 years ago · Donald J. Robertson

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of LifeThe Difference between stoicism and StoicismAgainst being unemotional and the case for a “Passionate Stoicism” I do not withdraw the wise man from the category of man, nor do I deny to him the sense of pain as though he were a rock that has no feelings at all. — Seneca, Letters, 71 Stoicism has become a quite trendy over the past …Read more2 years ago · Donald J. Robertson