Kristine H. Harper's Blog, page 3

October 17, 2023

Resilient aesthetics

Resilient aesthetics and resilient beauty are terms that immediately sound like oxymorons, as beauty and aesthetically pleasing experiences and objects tend to connote something fleeting, transient, and/or volatile. We are used to viewing beauty as something that fades, being synonymous with newness, youth, unwrinkled faces and garments, fresh flowers, polished tables, newly painted walls, and with undented floors — all of which diminish with age, usage, and wear. We are used to aesthetics and beauty being linked to the visual impression of an object.

But resilient beauty is not smooth and spotless. It is mature and open.

Charging a design-object with resilient aesthetics is a celebration of usage, and implies creating an object that is made to be used, grow, become more beautiful or intriguing, and sense-stimulating with age as it is infused with and developed by the hands that touch it and the occasions for which it is used.

“Regardless of when the objects’ optimal state takes place, there is a sense of process applicable to all material existence, and it is generally one-directional. After the optimal state, the objects are considered “past their prime” and we get the feeling that things are “downhills from here,” and most of our effort is directed to- ward “repairing” and “restoring” the deteriorating objects and “turning back the clock.”

As professor of philosophy Yuriko Saito points out in this quote from her book Everyday Aesthetics, our linear way of looking at things often makes us praise newness and the beauty related hereto, and hence define beauty as something unblemished, flawless, smooth, and pristine. In the linear perspective there is a starting point, and a development that moves toward an end point, which is either defined by malfunctions and unrepairable or non-upgradeable elements; or by the shifting winds of fashion, and thus, perceived obsolescence.

Resilient beauty is enduring; it is open to development and even embraces the tactile qualities of unevenness, roughness, irregularity, and decay. Resilient objects are created to be used, and the traces that usage leaves must naturally be incorporated into their central concept.

Photo from weaver village Tanglad in Nusa Penida that I recently visited

Photo from weaver village Tanglad in Nusa Penida that I recently visited

A good example of an aesthetically resilient object is a vintage object. When garments, furniture, or bicycles for that matter are described as vintage, an affirmative term, it basically means that the specific object has become more beautiful and more valuable with age and with frequent use and wear. It seems as if the previous owner’s love for the object has left enhancing aesthetic traces on its surface, and so, its beauty can be described as resilient.

However, a vintage object can only be described as resilient after it has, so to speak, proven being so. But perhaps new objects can be infused with resilience from conception. The design process should then include more than considerations on how to attract consumers and convince them to buy yet another new thing. It should contain well-thought through and transparent intentions or even calculations on how to prolong the user phase to ensure a long product lifespan.

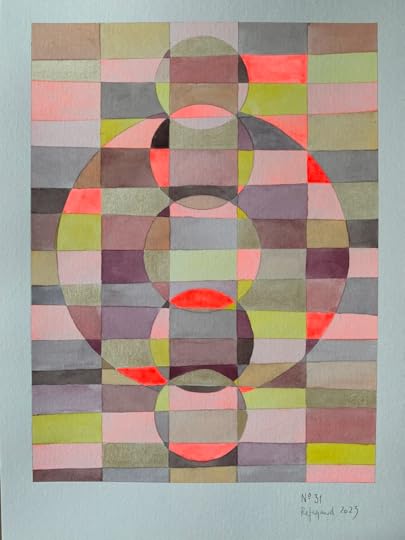

Photo created in LimeWire

Photo created in LimeWire

Resiliently aesthetical objects are sharable, durable, and they contain a certain heaviness. The term heaviness often connotes something dreary or gloomy, however, here it refers to meaning, substance, and stability and challenges. In order to live sustainably we must invite more heaviness into our lives; meaning, more substance, more stability as well as more significance and challenges. Resiliently aesthetic objects are charged with heaviness in relation to the undertones, associations, and feelings that they awaken in the receiver.

The sensations that are stimulated by an aesthetically resilient object are heavy in the sense that they don’t pass immediately — they linger. However, the heaviness that the aesthetically resilient object is infused with is also very hands-on in a physical, phenomenological kind of way. The hands-on heaviness that the resilient object encompasses consists of physical, material, sensuous stories; stories about the time that has been literally put into the object, which might even be discernable on the object’s surface; stories about the time that has been spent conceptualizing and constructing or shaping the object; or stories about the time that is meant to be spent using the object, which materializes in the newly designed object’s openness to usage.

By emphasizing that it is not only the “privilege” of the vintage object to be resilient—because it has with time proven to be so—but that resilient aesthetics can also be charged into a new design-object, I wish to high- light the importance of making user-phase considerations a vital part of the design process.

Furthermore, when I write “new design-object” it is important to stress that a new object could very well be upcycled, or an object made of recycled materials rather than virgin materials. We are at a point right now where designing new products can really only be legitimized if these are created to be extremely long-lived or in other ways improve our ability to live sustainably.

September 25, 2023

The Universal Effect of Color

Colors are a vital and aesthetically nourishing part of an object’s expression. But when creating sustainable design products that are meant to last and to be loved and maintained for years, decades, well, maybe even a lifetime, how does one supersede color symbolism and trend-based color-favoritism, which tends to shorten the lifespan of an object?

Maybe a way could be to work with the physical or sensuous effect of colors.

Sensorially, human beings have a tendency, for instance, to regard darker colors as being less expansive than lighter ones; a white room seems bigger than a dark blue one; black appears slimming because our gaze decodes color in this way. Further, colors such as blue, turquoise, and cyan appear cool; whereas red, purple, and orange seem warm by contrast. A red chair will feel warmer to sit in or to stroke one’s hands across compared to a blue counterpart. A room of cyan walls will feel colder than a room of purple walls, and so on.

Regarding color theory, a number of aesthetic principles challenging the color symbolism red for love, white for innocence, green for hope, etc.) and the trend-/ culture based approach to color, have preoccupied thinkers and artists such as Johan Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) and Johannes Itten (1888–1967).

Basic universal principles of aesthetics, in regard to color, can help us understand how different colors affect the human senses and how to create an expression that fosters the most harmonic composition — that is not affected by trends, culture or symbolism.

In his work of 1961, The Art of Color: The Subjective Experience and Objective Rationale of Color, Itten sets up guidelines for creating color harmonies or contrasts. For Itten, harmony means equilibrium or symmetrical composition. The eye is always searching for symmetry, according to Itten, and the color contrasts, when followed, can provide it with the means of achieving a sense of equilibrium and harmony, which is immediately pleasurable.

For example, complementary contrast provides the eye with a calm aesthetic experience, as all three primary colors (red, blue, and yellow) are present, and because humans have an innate preference for the simultaneous presence of all three primary colors. This preference can be illustrated with the following example: staring for a minute at a green circle and then moving one’s gaze to a white surface will result in the eye creating the illusion of a red circle (Itten called this illusion simultaneous contrast). Since green is a mix of yellow and blue, all three primary colors are here present.

The complementary and the simultaneous contrasts are two out of seven color contrasts that can help create different color harmonies. The rest are the contrasts of hue, light-dark, cold-warm, saturation, and extension. According to Itten, our senses can only apprehend and process objects and expressions by way of comparison, and the different contrasts can affect the senses in more or less powerful or diverse ways.

The harmonious composition of the color contrasts can nevertheless be challenged. Designers and artists can choose a challenging, dynamic, and vivid expression in order to change the color scale in relation to the contrast of extension and thereby make room for the most “voluminous” or expansive color (yellow, say) in a given composition, as this would break with the harmony, which is attained by maintaining the internal sense of proportion. Itten bases his concept of scale on Goethe’s color theory.

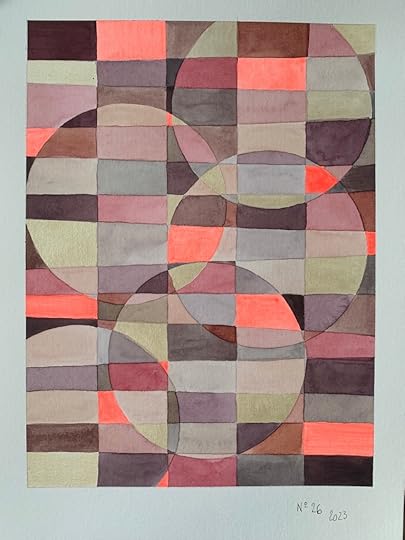

Artist x Artisan collaboration by Lene Refsgaard & Southeast Saga

Artist x Artisan collaboration by Lene Refsgaard & Southeast SagaIn line with Itten, Russian painter and art theorist Wassily Kandinsky has discussed colors and their physical effect on the human senses in his poetic and theoretical work, Concerning the Spiritual in Art.

According to Kandinsky, colors have a physical, almost tactile, effect on the viewer that is based in the “spiritual vibration” of a given color. This sensorial, synesthetic approach to color, which is characteristic of Kandinsky, is expressed in the following quotation:

Many colours have been described as rough or sticky, others as smooth and uniform, so that one feels inclined to stroke them (e.g., dark ultramarine, chromic oxide green, and rose madder). Equally the distinction between warm and cold colours belongs to this connection. Some colours appear soft (rose madder), others hard (cobalt green, blue-green oxide).

The extent to which human beings are susceptible to the “vibrations” of colors and shapes, Kandinsky suggests, depends on their spiritual sensitivity. This means that it is only possible to truly impact the “spirit” of the viewer if she engages with and remains open to the aesthetic experience.

But what characterizes such a human being — a human being for whom, to quote Kandinsky, “[t]he expression ‘scented colours’ is frequently met with”?

And can spiritual sensitivity be taught?

Imputing to the artist (or designer) this kind of task is certainly idealistic: teaching humanity about spiritual sensitivity or about how to be open and receptive to aesthetic experiences and to recognize their value as such.

Artist x Artisan collaboration by Lene Refsgaard & Southeast Saga

Artist x Artisan collaboration by Lene Refsgaard & Southeast SagaItten, Goethe, and partly Kandinsky take a phenomenological, rather than a symbolic, approach to color. In other words, all three are concerned with how colors and their “weight” or combinations/contrasts affect the body (and the mind), how colors feel to be around, rather than with what they symbolize or which associations they spark in the experiencing subject.

The phenomenological approach ignores culturally specific symbolic values, which are changeable and which are thereby antithetical to the universal (unchanging, eternal) human experience of color.

On the whole, phenomenology has a lot to contribute in terms of locating a universal experience of the world and its physical objects. If the corporeal understanding and apprehension of the world comes before the cognitive and the reflective, as French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908–61) thinks, the cultural “baggage” and connotative framework of human beings are not necessarily an impediment to creating aesthetically durable expressions or objects with the ability to please or challenge recipients and thereby affecting them in powerful ways. In fact, cultural connotations are entirely insignificant in this regard.

Artist x Artisan collaboration by Lene Refsgaard & Southeast Saga

Artist x Artisan collaboration by Lene Refsgaard & Southeast SagaRead more about the Artist x Artisan collaboration by Lene Refesgaard & Southeast Saga here.

September 12, 2023

The Rescue Rejected Jeans mission

The global denim market has seen persistent growth in the past few years, and is forecast to reach $107 billion by 2023.

Research shows that less than 1 per cent of discarded denim is recycled. 80 per cent of this is sold as second-hand apparel in poorer countries (and I went to one of the markets where this takes place today), and nearly 20 per cent goes to landfill or are incinerated.

Approximately 2,900 liters of water is used in the production of a single pair of jeans. And yet we happily throw away our jeans when they no longer serve us (meaning are no longer perceived as trendy, cool, beautiful or whatever we choose to call it).

The poor rejected jeans… so so many of them….

The jeans that I rescued today are now in my home relaxing and will soon be reborn as Southeast Saga Mosaic Kimonos

“Rejected by previous owner, rescued and reborn by Southeast Saga” is the mantra.

Stay tuned for more on instagram!

The Rescue Rejected Jeans mission by Southeast Saga

The global denim market has seen persistent growth in the past few years, and is forecast to reach $107 billion by 2023.

Research shows that less than 1 per cent of discarded denim is recycled. 80 per cent of this is sold as second-hand apparel in poorer countries (and I went to one of the markets where this takes place today), and nearly 20 per cent goes to landfill or are incinerated.

Approximately 2,900 liters of water is used in the production of a single pair of jeans. And yet we happily throw away our jeans when they no longer serve us (meaning are no longer perceived as trendy, cool, beautiful or whatever we choose to call it).

The poor rejected jeans… so so many of them….

The jeans that I rescued today are now in my home relaxing and will soon be reborn as Southeast Saga Mosaic Kimonos

“Rejected by previous owner, rescued and reborn by Southeast Saga” is the mantra.

Stay tuned for more on instagram!

September 10, 2023

Breathing Life Into Fading Craft Traditions

Although I usually push for radical reduction of consumption and the production of new products, there’s a one important reason for designing new things in a world overflowing with discarded objects — and that is to sustain traditional crafts and prevent them for dying out.

However, even with the prevailing and clear enjoyment of shopping, we are currently experiencing a mass extinction of crafts traditions worldwide. Part of the reason for this is the immense competition that quickly, cheaply produced products constitute in relation to slowly crafted artifacts. And part is due to the societal and cultural development of norms and status, which tend to be interlinked with a need for growth and quick, easy acquirement of convenient products.

The role of a sustainable designer hence goes beyond just creating new things. There is a deeper, more profound mission interlinked with the profession, which includes reviving endangered craft traditions and joining hands with local communities to make sure everyone gets their fair share.

Gratefully, there are lots of conscious consumers out there, who hold a deeper care, transcending appearances and convenience. Their focus extends to the narratives woven within the objects, to the values that these creations bear.

The current state of affairs is that traditional crafts are endangered in many regions in the world. This tendency is typically either caused by a lack of status and money in working as an artisan, so younger generations pursue other careers. Or, it is due to the aesthetics linked to the particular crafts stagnating, which has led at times to traditional craft products being labeled kitsch — an unjust label that taints them with an air of tastelessness and gaudiness.

As mentioned, adding to these challenges, the discordance between traditional crafts and the demands of many contemporary consumers exacerbates the struggle. The needs of modern mass-consumers, marked by the rapid pace of life, tends to diverge from the offerings of time-honored crafts. While traditional pieces are often infused with profound cultural significance and an intricate legacy, they may not always harmonize with the immediate demands of a world geared for convenience and immediacy.

In this intricate dance between heritage and evolution, the threads of traditional craftsmanship often find themselves frayed, stretched between the past and the present. There is a need for innovative solutions that can bridge the gap between tradition and modernity.

The vanishing of traditional crafts techniques leads to the unfortunate loss of invaluable knowledge and expertise. These techniques, often honed over generations, carry within them the essence of cultures, communities, and the mastery of human hands.

Moreover, crafts techniques and patterns are seldom archived in written form, and the intricate designs that constitute the heart of traditional crafts are rarely transcribed or stored on paper. Instead, they are intricately woven into the fabric of intergenerational transmission, handed down from one skilled hand to the next through oral traditions and live demonstrations. The intricate patterns of traditional weaving are intricately woven into the very fabric of life itself — entwined with the rhythms of ceremonies, the cadence of daily routines, and hence preserved within the very activities of the people.

When artisans veer towards alternative paths for earning their livelihoods — which is a lamentable consequence of the fading resonance of crafts traditions — a tapestry of craftsmanship unravels, one intertwined with customs, daily rhythms, memories, and the accumulated wisdom of countless artisans before them. This decline signifies more than just a cultural setback; it signifies the gradual erosion of diversity — it is an unfortunate movement towards homogenization and globalized sameness.

This loss resonates as a void within the collective spirit of a society. Each discarded craft technique or forgotten pattern holds within it the potential for inspiration: for igniting imagination — as well as for fostering a connection to our roots. There is therefore an urgency in this plea to recognize artisans’ crucial role in safeguarding our cultural heritage. Because crafts’ survival is prerequisite to sustaining and protecting stories, heritage, and the very essence of our diverse, interwoven human family.

So, what’s the answer? How can a sustaining designer make a difference?

At the heart of the sustainable designer’s role lies innovation — a pivotal force that can empower artisans to sustain their livelihoods and rescue dying crafts. Breathing new life into traditional crafts involves optimization, where processes are refined, designs reinvigorated, and potentially intertwining traditional techniques with modern technologies.

One of the most challenging parts about sustaining endangered crafts traditions is the balancing act between maintaining the core of the craft — the technique, hands-on wisdom, the look of the traditional patterns, the feel of textures, etc. and updating the overall aesthetics in order to effectuate and innovate.

The difficulty here lies mainly in the curious fact that the significant aesthetics — the look and feel of the crafted product — which is linked to a specific crafts tradition is its strength but simultaneously its Achilles heel.

A craft-tradition is accompanied by certain motifs, patterns, textures, color combinations, carvings, or shapes, and is restricted to staying within the limitations of these. The motifs and textures are typically charged with connotations; with metaphysical meaning, allegories, symbols, stories, and signs, and linked to certain events or ceremonies — and only worn or used at these — societal status, family ties, or life-phases. And traditional artisans are trained to carry out these conventional patterns with precision.

However, these shapes and motifs may not align with the preferences and needs of those beyond the initial target audience for which they were crafted. As they are removed from their original context, their symbolism might dissipate or lose its significance, rendering them void of meaning. Additionally, their functionality might become outdated, and their aesthetic appeal might fall short of offering a complete nourishing experience.

Moreover, as already discussed, the techniques inherent to these original craft expressions often demand extensive time and effort, resulting in a situation where contemporary artisans find themselves unable to equate the price of their meticulously crafted products with the hours invested in their creation. This poses a substantial burden on artisans, who grapple with the challenge of preserving their craft while also ensuring its viability in a modern market.

The balancing act that the sustaining designer faces hence involves locating the core of the specific craft-tradition that she is working on preserving — whether this is wood carving or basket or textile weaving — and entering the design-process with the overall objective of leaving significant, recognizable traces from the original layout.

But how do you discover the very heart of a craft’s expression? How can you ensure that as you innovate, you preserve its essence rather than letting it fade away, erasing its original technique and spirit, contradicting the very notion of sustaining the craft?

How do you uncover the fundamental core of its patterns, textures, or forms, and weave this core seamlessly into a new iteration, all with the overarching aim of rescuing that unique craft tradition from the brink of extinction? And most importantly, how can you guarantee that the wisdom passed down through generations remains alive and unscathed?

Within this process, a hint of deconstruction comes into play, resembling the act of peeling back layers to reveal the core of the specific craft. To unearth its most essential characteristics, one must engage in disassembly and reverse engineer its appearance, tactile sensations, and functional intricacies.

Navigating these inquiries is a multi-layered endeavor, and it’s precisely this exploration that lies at the heart of my new initiative, Southeast Saga. By embarking on this journey, I aim to uncover how the essence of craft traditions can be safeguarded, their techniques invigorated with innovation, and their stories woven into the tapestry of our ever-evolving world. Through Southeast Saga, my intention is to pay homage to the artisans of Southeast Asia, especially Indonesia (as this is where I spent a significant amount of my time), to honor their expertise, and contribute to the preservation of these invaluable traditions.

I invite you to join me on this journey! As I uncover the stories, traditions, and innovative approaches that breathe life into fading crafts in the wild, beautiful Southeast, your presence will contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage and the celebration of human creativity.

August 28, 2023

Southeast Saga

Dear loyal readers,

I am very excited to share with you my latest venture, Southeast Saga

Here, the beauty of Bali, Indonesia, merges with the spirit of aesthetics and sustainability.

As a lot of you already know, I live in breezy, open house, where the jungle meets the rice fields, I embrace the role of an author, immersing myself in sustainable, rewilded living. I am frequently barefooted, deeply into loud music, nerdy books, long podcasts, and poetry. Oh, I am also a vegetable garden enthusiast – though not very successful, yet

My professional journey is centered on delving into the depths and breadth of sustainability, inspiring the creation of designs that offer a deeply enriching aesthetic experience and stand the test of time.

Southeast Saga isn’t just a venture; it’s a purposeful journey comprising:

Soulful Journal: a collection of immersive articles that delve into the realms of rewilding, sustainable living, and aesthetically enriching design. Beyond that, it’s a portal to visually enriching experiences, inviting you into the studios and homes of artisans, artists, and writers who call the Southeast their cherished home.

Soulful Journal: a collection of immersive articles that delve into the realms of rewilding, sustainable living, and aesthetically enriching design. Beyond that, it’s a portal to visually enriching experiences, inviting you into the studios and homes of artisans, artists, and writers who call the Southeast their cherished home.

Local Wisdom Workshops: Embark on a soil-bound journey. Themes encompass aesthetic sustainability, “new luxury” infused with the passage of time, plant-powered design, tactile literacy, and the art of natural dyeing. Collaborate with artisans, fusing creativity and craft.

Local Wisdom Workshops: Embark on a soil-bound journey. Themes encompass aesthetic sustainability, “new luxury” infused with the passage of time, plant-powered design, tactile literacy, and the art of natural dyeing. Collaborate with artisans, fusing creativity and craft.

Sustainability Services: Seeking the pulse of sustainable trends? My custom-made slow trend reports and sustainable storytelling hold the keys to a more conscious and thoughtfully fashioned future.

Sustainability Services: Seeking the pulse of sustainable trends? My custom-made slow trend reports and sustainable storytelling hold the keys to a more conscious and thoughtfully fashioned future.

Rescued and Rewilded: “Rejected by previous owner – rescued and reborn by Southeast Saga.” This mosaic collection merges salvaged garments with handcrafted textiles in a harmonious symbiosis. The mission is simple: to inspire the joys of reusing, repairing, reducing, and at times, refusing.

Rescued and Rewilded: “Rejected by previous owner – rescued and reborn by Southeast Saga.” This mosaic collection merges salvaged garments with handcrafted textiles in a harmonious symbiosis. The mission is simple: to inspire the joys of reusing, repairing, reducing, and at times, refusing.

Crafts Collection: In collaboration with local textile weavers, the fabric of Southeast Saga comes to life. Timeless pieces for wardrobes, living rooms, and bedrooms are born from this union, destined to stand the test of time. Moreover, occasional artist collaborations will add a unique dimension to select creations.

Crafts Collection: In collaboration with local textile weavers, the fabric of Southeast Saga comes to life. Timeless pieces for wardrobes, living rooms, and bedrooms are born from this union, destined to stand the test of time. Moreover, occasional artist collaborations will add a unique dimension to select creations.

Each chapter of Southeast Saga’s story is infused with purpose and fueled by passion. I invite you to join the journey- launching soon!

With love and respect,

Kristine

August 17, 2023

The Beauty of Slow Aesthetics

Fashion is by definition focused on new and forward-looking trends. But despite of its forward-looking and new-is-good doctrine, fashion constantly borrows from the stylistic expressions of earlier times. It is often described as moving like a pendulum between two dialectical poles — for example, the minimalistic, “purified” expression and the decorative, decadent, and “maximalistic.” A movement that, rather than being either decidedly forward-looking or exactly retrospective, should be considered stagnant.

Every season is defined by new colors, styles, and themes, whether in relation to clothes, interior design, or food. These are often (especially regarding clothes fashion) “dictated” by trend agencies, which report on the focus points of the coming season, based on an analysis of societal trends.

For example, a theme could be “Urban Boheme” complete with flowing robes, flowery patterns in warm nuances, dark velvet suits, and broad-brimmed felt hats, on the basis of the idea that we are living in a time when the individual is striving for a free, relaxed urban existence, reminiscent of artistic 19th-century Paris. This is grist to the mill of our throwaway culture, but it is not in keeping with aesthetic sustainability. If themes change every season, who would want to parade around looking like a mix between a 70’s hippie and a 19th-century dandy, when the current look is minimalistic, “tight,” and influenced by black-and-white geometrical patterns?

My beautiful Marius wearing a handwoven kimono from Southeast Saga

My beautiful Marius wearing a handwoven kimono from Southeast SagaSo, what is the best way to circumvent this mechanism? Currently, there are many interesting anti-trend movements that “dictate” slow design, slow fashion, or slow clothing — all of which challenge the whirling forward momentum of fashion and the constant impetus to consume. In fact, it has become trendy to preface everything with “slow”: slow food, slow travel, slow living, slow parenting, slow shopping, etc. In a way, this is a somewhat self-contradictory move, as the intention is rather to think beyond the trend-machine.

Nevertheless, the slow movement, in relation to aesthetic sustainability, contains a number of important points. In point of fact, aesthetic sustainability can be considered part of the slow movement — the part, which could also be called slow aesthetics, that aims to put a brake on aesthetic pleasure (to keep it from dissipating, which would lead to casting aside the object that caused it in the first place and moving on to the next in line), or, rather, to make the aesthetically pleasurable experience last longer.

The slow movement, in brief, is about celebrating slowness and challenging consumerism. The focus is on “little, but good” — the idea that slowness results in an increased focus on one’s surroundings and the objects found here, and that this focus is a source of intimacy. Physical, sensuous intimacy, that is. A kind of intimacy that might disappear when living life in the fast lane, to use an obvious cliche.

I consider the slow movement and the intentions behind it as an expression of a paradigm shift, rather than as a passing trend like many others.

Photo by Susan Wilkinson on Unsplash

Photo by Susan Wilkinson on UnsplashAesthetic pleasure is not just about renewal, but also about repetition. A worthwhile piece, or a good design object, can nourish the owner aesthetically time and again. This is exactly what makes it slow — and lovely.

Establishing a “relationship” with an object — bonding with an object in the sense that merely a glance or a touch is enough to elicit an all-encompassing feeling of comfort or an inspiring feeling of seeing everything in a new light — means that one will want to keep it around. Getting rid of it, finally, would signal that one is “done” with it, that one has perhaps moved on to a different stage of life, wanting to make room for new moods and new impulses — which is, of course, only natural.

The slow aesthetic experience is a continual source of aesthetic nourishment and enrichment; an experience that is characterized by being both constant (something one will want to relive) and regenerative, as it is a continual source of new nourishment — whether it is the kind of nourishment that leads to immediate enjoyment or to trembling pleasure.

My wonderfully crooked floor and thick handwoven rug from Java (by Southeast Saga)

My wonderfully crooked floor and thick handwoven rug from Java (by Southeast Saga)To create sustainable objects, which are aesthetically durable, and which thereby possess an aesthetic slowness, one must thus juggle permanence as well as variation, fixity as well as vitality, repetition as well as renewal. Only in combination is it truly possible to nourish the experiencing subject aesthetically and to open up an aesthetic, potentially insightful, realization and for the individual to feel “at home” in the world.

The durable aesthetic object consists not solely of pure permanence, which might otherwise be an obvious conclusion, as permanence and sustainability are closely related. The durable aesthetic expression consists of a combination of permanence (and thereby the enduring or what is temporally extended) and renewal, variation or energy (meaning that which is surprising and uneven, that which triggers the mind into movement and challenges the senses).

Permanence is expressed, for instance, by shapes and color combinations that speak directly to the viewer, and that are easy to decode, or understand, and to use; permanent objects can be quickly absorbed and put to use. This element is essential in relation to aesthetic sustainability as it is of universal appeal, which partly concerns the joy of recognition and partly the pleasure of satisfying one’s human need for synthesis and structure.

However, renewal and dynamic energy are just as crucial. To keep the viewer engaged, the object must leave an impression so great as to separate itself from the enormous amount of human-made things that clutter our world. Achieving this, means that the object must contain a certain degree of renewal and dynamic energy. The dynamic part of the aesthetic sustainable object is the part that makes the viewer take note, and that makes her come back to the object, again and again, as she seeks the immediate pleasure experienced in first encountering it.

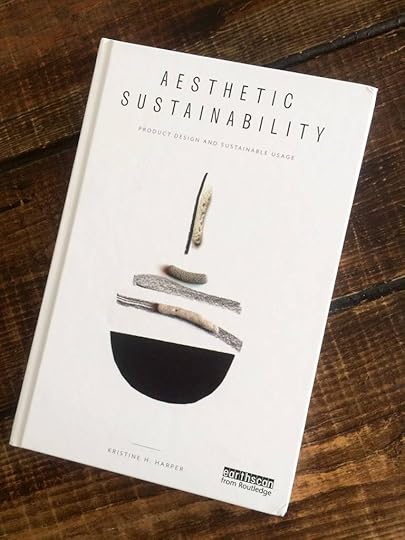

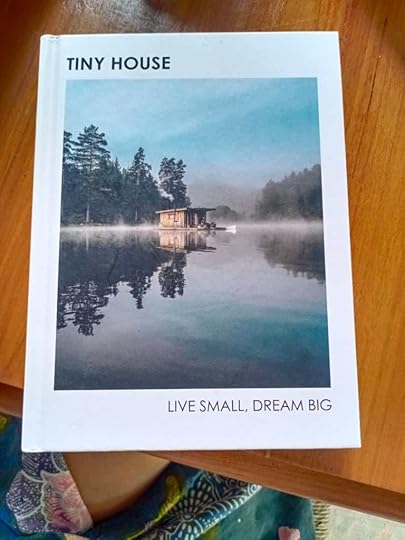

My book Aesthetic Sustainability that discussed ways of creating aesthetically durable design products

My book Aesthetic Sustainability that discussed ways of creating aesthetically durable design productsthe aim is to create a design object valued for its ability to prompt comfortable feelings in an immediate way, it is not enough to simply copy an already-existing object. On the contrary, it is necessary to temper the familiar with the regenerative, with variation. The regenerative element can be rather low-key, consisting, for example, of a material that adapts to the form without issue and without inertia, and that thereby matches the form and the use of the object, but which is nevertheless somewhat different from the material usually employed to construct the particular object. It might even work better.

Working on creating such objects can be described as an investigation of how much the core of an easily recognizable or easily decodable jacket, chair, lamp, or cup can “contain:” how far can the expression or the form or the sensuous qualities of an object be stretched, while still evoking the a familiar kind of pleasure?

The aesthetically sustainable object— and hence the object that manages to appeal to a human being who will watch it, use it, consider it, or touch it, time and again — has a core consisting of an easily recognizable or easily decodable element and of either some or a lot of dynamic movement, regeneration, and variation. This is to ensure that interest in the object will endure for an extended period of time, maybe even for decades, and that the experiencing subject will return to the object in search of new aesthetic satisfaction, creating a bond to it in the process.

June 1, 2023

My precious

I am still in the process of writing a new book that I have named Uncultivated.

The book is built around negations of what I have chosen to call “the ten commandments of cultivation”. The intention herewith is to challenge taken-for-granted cultural and societal “truths” and assumptions and to promote a rewilding of the cultivated human being.

The ten commandments are the following:

We have to adapt and behaveWe are superior to animalsWe are separated from natureWe must be ambitiousWe must work hardWe must consumeWhat we cannot explain is not trueWe do not talk about deathWe must defeat decayWe must live in the nowIn this post I will share a short passage from Chapter 6: We must consume.

My favourite glitter shoes.

My favourite glitter shoes.  Waste art-installation made by arist Liina Klauss

Waste art-installation made by arist Liina Klauss We buy glittery, shiny things like were we magpies; collect and store them in our homes and wear them to decorate our bodies and flash our wealth and/or trend- or sustainability-awareness.

Consumption is so much more than just surviving — we are way, way past satisfying our most basic needs for food and shelter, and we consume more for entertainment and image than for functional, practical reasons. Even the consumption of food and drink has become a lifestyle-act: what and when we eat and even if we eat appears to be a part of our late-modern identity-creation (do we occasionally fast or do we engage in intermediate fasting on a daily basis — and hence withhold from consumption?).

Refraining from consumption when it comes to fast fashion items and other trendy knickknacks seems to have also become a nearly activist-like choice that signals consciousness and awareness (and is typically flashed on social media). But the act of refraining from consumption is for the privileged few only; for the once who can make a choice and decide not to consume — because they already have more than enough, and because they will never go to bed hungry unless this is a conscious decision.

(quick parenthesis here: when I write “they” I of course mean “we”, as I too am a part of the privileged few, who are fortunate enough to check in and out of consumption as if it were an existentialist quest.)

Photo by charlesdeluvio on Unsplash

Photo by charlesdeluvio on Unsplash My own photo of a very instagramable coffee

My own photo of a very instagramable coffeeIs being a consumer an identity? Late-modern, privileged consumption is interlinked with feel-good-experiences, acknowledging gazes and status symbols — well, in general with experiences rather than with getting fed and nourished (which you might initially, naïvely, think consumption was all about, given the word) or with being clothed and sheltered.

One could even raise the question: What are we if we don’t consume? (well, unless it is a conscious act of non-consumption, under which circumstances we are still acknowledging the driving force and the importance of consumption).

What is our purpose if we don’t participate in the spending party — if we don’t desire anything or rather any thing? Because, let’s not forget that you can desire something without desiring things, objects, shiny stuff. But it appears that we have forgotten how to do that. And this despite the fact that all our most applauded current lifestyle tendencies (slow living, simple living, minimal living) celebrate living with less belongings and with more awareness.

Photo by Uliana Kopanytsia on Unsplash

Photo by Uliana Kopanytsia on Unsplash Handwoven tablecloth by illusi

Handwoven tablecloth by illusi

During the pandemic consumerism even seemed to become more predominant as an identity creator. I guess it in a way makes sense, as it was one of the only possible ways to interact, communicate, and feel alive! So, despite the fact that most people were stuck at home and hence had no-one to flash their brand new phone or gadget to, and nowhere to go wearing their new trendy outfits, consumption via online shops skyrocketed.

What does that tell us about our consumption of things? If we don’t consume in order to be well-dressed when we go to work or to be up to date in the eyes of our peers, I guess the consumption of new, fashionable, tech-trendy, glittery things has become a crucial part of our personal well-being.

This reminds me of a sign I often pass in a shop in Ubud that says: “shopping is cheaper than therapy.

The dream of the simple life is a predominant theme in books, films and on blogs

The dream of the simple life is a predominant theme in books, films and on blogs

We need an alternative to consumerism. We need an anti-consumerist manifesto: one that will gain loads of followers and that can fill our late-modern lives with sense and direction. And we need it pretty much right now.

Why? Well, firstly, and obviously, because our overconsumption is a ticking bomb under an ecological disaster waiting to happen (or sorry, more correctly; a disaster that is already happening).

I don’t like to lay out doomsday scenarios. But overconsumption of insignificant, unsustainable short-lived things wrapped in cheap plastic meant to be thrown away after removal (but never really disappears) is one of the main sinners when it comes to pollution.

I see it every day here in Bali. There is trash everywhere! Piles and piles of plastic waste in the ditch edges, dirty brown rivers of plastic that flow down the sides of the mountains during rainy season, heaps of plastic flip-flops and toothbrushes and ice cream wrappers and shampoo bottles and polyester shirts are washed in from the sea and turn the beaches into colourful patchworks of disaster, discarded clothes from all over the world are shipped here and pile up in landfills while slowly emitting methane clouds into the environment, and the same goes for hard plastic waste from computers and washing machines and televisions.

The beautiful rice fields surrounding our house. You can see the wooden fence around our land in the background

The beautiful rice fields surrounding our house. You can see the wooden fence around our land in the backgroundMy family and I recently bought land here in Bali–a blissful little piece of heaven overlooking vast rice fields and with the majestic over 3000 meter high volcano Mount Agung towering in the background–and started digging up the soil in order to plant vegetables and herbs and fill the land with tall, slender bamboo, fern and fruit trees, my awareness of the immense plastic pollution that we are facing here in Bali reached new heights. There were generations and generations of plastic in the soil! I almost felt like an archeologist; digging through layers, observing the different states of my findings. The further down we dug, the more old, dirty, yet hardly deteriorated, plastic surfaced. Some of the plastic that had clearly been there for years had the texture of parchment paper and was thin and porous, but still far from a state of deterioration. There were also old clothes, primarily made from polyester or rayon. I found shirts, socks, trousers, even shoes.

Since there is hardly any infrastructure for waste management here in Bali, most people just throw their trash in nature. And, when a piece of land, neighbouring a village, is uninhabited for a while (like ours was) it tends to become the village dumpster.

However, one could argue that this is only the case in developing countries like Indonesia, and that in Europe or America or Australia (or wherever you, my dear reader might be located) it is different: there is an effective system for waste management; waste is even mostly recycled or used as fuel or in other ways made into a ressource. And while that might be true, there are two points I would like to point out: 1. a lot of the waste that ends up in large landfills here in Indonesia is shipped here from Europe or America or Australia (which, as a subtle side remark, is a whole new way of exhibiting colonialism), and while this might solve the waste-problem that overconsumption constitutes in developed countries, it only adds to the overall global inequality. Furthermore, just because waste is out of sight, it doesn’t mean that it is gone. We live on a globe of connecting continents and oceans, and hence the pollution that these landfills cause should be everyone’s concern.

Which leads me to the next point; that 2. even though the worldwide waste-problem is not visible in developed countries, and one will not experience buying land and finding decades of plastic waste layered in the soil (like we did here), there is no recycling system and no “turning waste into a ressource” procedure that can keep up with the amounts of waste that are generated every year. Last time I checked the number was an astounding 2.12 billion tons of waste a year! If all that waste was loaded on trucks they would go around the world 24 times.

So actually, while you might be appalled by the image of my plastic-polluted backyard, the layers of pollution I am experiencing in our garden and here in our small village (plastic bottles thrown on the side of the road, sweet wrappers in the fields, nappies floating down the river, etc.) is nothing in comparison to the mountains of waste the population of a similar sized European village generates.

The only difference is visibility.

Besides the immense pollution that overconsumption causes, there is another reason for our concurrent need for an anti-consumerist manifesto. A reason that is closely interlinked with my present plea for uncultivation.

Let me explain.

Consumption contains destruction, says French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir. Consumption means utilising or going through stuff: things and experiences. It is a destructive movement, because the act of consuming is wasteful and mostly conducted for momentary pleasure. The act of consuming constitutes a counterpoint to storing up and saving, which is what you do when you aim for, what de Beauvoir eloquently calls: stationary plenitude in-itself.

The term stationary plenitude in-itself makes me think of phrases like self-sufficiency, resilience, nourishing repetitions, independence, and autonomy. All of which are related to leading an justifiable, sustainable life.

Consumption is in other words in opposition to sustainability. It is a negative movement, which at its core is based on destruction. But nevertheless; despite its destructive nature, consumption is a crucial way of being cultivated in our late modern reality.

Photo by Haithem Ferdi on Unsplash

Photo by Haithem Ferdi on Unsplash My very worn-out jeans (and my little friend Ana’s feet)

My very worn-out jeans (and my little friend Ana’s feet)Reducing consumption radically–by for example investing in only a few things that are made to last, by mending and repairing one’s belongings, by buying secondhand clothes, or by wearing the same clothes to parties every time, by embracing or even elevating wear and tear as a sign of a loving bond to one’s belongings, or by not giving a s… if one’s phone is not the right shape or thin enough or up-to-date with whatever tech-trend is predominant, and by flashing this behavior and thereby paving the way for a new sense of luxury and new rewilded status symbols, can be an uncultivated act of civil disobedience that might inspire others.

(And maybe writing about one’s actions could outline the well-needed uncultivated anti-consumerist manifesto).

May 6, 2023

Regrowth: Design Visions for the Future

Imagine your jacket being a living organism can repair itself, reinforce broken areas, and regrow — just as plants in nature do.

An intriguing way of designing objects that are resilient to changing needs is to embrace regrowth. Regrowth involves making repairs and upgrades an integral possibility. The majority of mainstream products intended for consumption are not designed for repairs or upgrades; they are made to become increasingly more unappealing and planned to be obsolete in a matter of a short time of usage.

Contrariwise, the resilient, anti-trendy design-object is upgradeable or maybe even regrowable.

Regrowth in relation to sustainable design can involve upgradability on many levels. It is, so to speak, a seed that is planted in the object from the starting point.

The term regrowth is typically used in relation to regrowing forests that have been cut down. It involves naturally regenerating flora and fauna, and it most often encompasses restoring a diverse ecosystem.

In the creation of anti-trendy, resilient design-objects regrowth involves restoration and regeneration. Imagine if your jacket or your chair was regrowable, or if it was naturally updatable? Imagine it being a living organism that when used and worn would repair itself, reinforce the broken areas, and regrow—just as plants in nature do? This might sound farfetched, but perhaps, as a part of the development of new natural design-materials it isn’t an out-of-reach thought.

Danish furniture designer Jonas Edvard works with local, raw, natural materials such as seaweed, limestone, hemp, and mushrooms.

Edvard’s MYX Chair is made from mushroom-mycelium and hemp-fibres; a material that is grown naturally and fast using no additional energy, and that is both flexible and solid. Using mushrooms and fungus as a material means making use of living materials that are constantly in flux and open to atmospheric changes and usage.

The MYX Chair can be grown, developed, and composed, and thus it mimics the cycles in nature.

Regrowth can also involve working with discarded materials such as plastic or textiles. Instead of growing new sustainable, alterable materials, regrowth can materialise as renewing or upgrading of waste or superfluous materials.

Danish sustainable fashion designer Freja Løwe specialises in natural dyeing of textiles. She uses anything from local plants to food waste to create her textile-dye and embraces the imperfection, rawness, and unpredictability that working with natural, “living” colours entails. The alterability of her garments and spreads is a crucial part of her aesthetic.

As she stated, when I recently interviewed her:

“Each color is an encapsulation of nature’s cycle and the fact that the colours change slightly over time is a reminder to the user of the natural variability life contains.”

Løwe works with zero waste in her design process, meaning that no swatches or scraps go to waste. The usage of the natural dye provides her with a tool that can transform and unify remainders from secondhand sheets and leftovers from her small-scale garment production into a sensuously nourishing expression.

Creating design-objects that are alterable and resilient to changing needs is in its core the equivalence of designing objects that are alive: objects that are made to contain traces of usage, that are adaptable to changing needs and situations, that are raw and open, and made to develop and take shape or regrow.

April 12, 2023

The master and the slave

In Phenomenology of the Spirit, German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel has a famous passage, known as the master/slave dialectic, which explains the importance of the relationship between equal, self-identical people when it comes to self-realisation. Between a free and a bound individual, the authentic acknowledgment, which is crucial for the realisation of the self, cannot arise. The acknowledgment between two people must always be mutual and free in order for it to have any value.

In Hegel’s theory of the master/slave relationship, a meaningless, non-evolving relationship between people, characterised by an unequal unilateral acknowledgment is displayed.

By enforcing acknowledgment, the acknowledging person is made unfree, and thus the acknowledgment is worthless. The master seeks acknowledgment from the slave without recognising them in return. Thus, the slave’s acknowledgment of the master is void, and because hereof neither party obtains a growth of their self-awareness.

In other words, it is crucial to the individual’s own development to respect the person from whom s/he seeks acknowledgment and to view them as an equal and unique personality. In the unequal relationship between the master and the slave, the master is independent and self-sufficient, while the slave is a dependent being.

Furthermore, the master has no connection to the objects surrounding her/him and feels independent of the outside world — in a sense he relates to his surroundings through the slave. The slave, on the other hand, is of course dependent and restricted, but work gives a degree of independence, as it defines her/him and provides direction. However, neither the master nor the slave is living an authentic life — both live despairing existences.

Hegel’s focus on the slave’s independence through his ability to navigate in and mould the physical world is captivating. It underlines something that I fid immensely important, namely that detachment from our physical milieu leads to deprivation and to a feeling of being unfree.

The slave knows how to navigate the physical world and knows how to interact with nature and make use of materials, resources, crops, and tools, and is aware of interconnectivity with the physical environment. The master on the other hand is detached, almost entirely, from physical surroundings. S/he doesn’t know how to make use of materials and doesn’t know how to operate and manoeuvre independently. S/he might be so detached so as not to even know how to cook. Hence, s/he is alienated to nature and to the physical environment. Without the slave s/he wouldn’t eat, be able to get around, or shape her/his surroundings.

To an extent, most late-modern people in developed countries are living as masters. They are alienated from nature and detached from knowledge about how to manage by themselves in their physical milieu. They might cook themselves, but the food they buy is partly pre-prepared: cut, cleaned, minced, and pasteurised; everything is made convenient. And when it comes to consumption, they are detached from knowledge about how the many things they buy are made. They know nothing about the materials that are used, how they are grown or constructed, and they know nothing about the conditions of the “slaves” that produce the goods they consume. They don’t know how to repair their things if they break or mend them when they get worn out. They cannot stitch or patch or darn.

When I write “they,” I of course mean we. I too am guilty of most of the above-mentioned points. But, leaving my convenient city life has forced me to become more aware, more conscious, and more attached to my physical environment, and to nature. And it is a gift; a grounding, nourishing gift.

In relation to nature — wild nature that is — not city parks or curated forests, most late-modern “masters” feel completely lost, even scared. A while back I had visitors from Denmark; a really good friend of mine and her daughter who live in Copenhagen stayed with us for two weeks. They were terrified by the sounds of nature that are omnipresent here. The sound of a gecko was more intrusive to them than heavy traffic, and the loudly croaking frogs and cicada choir that takes off every night at sunset felt more threatening to them than howling police sirens. Not to mention the knowledge of the presence of snakes and scorpions, which felt like a constantly lurking fear to them (despite the fact that I have only on a couple of occasions had encounters with these creators, even after living here for years, and that they were, of course, much more scared of me than I of them).

Why do we feel so lost and frightened when exposed to nature? Why have we sacrificed our knowledge about how to get by and get nourished in and by nature; make food, clothes, and medicine out of plants, shape our living spaces in accordance with our natural environment, and live in harmony with wildlife.

On that note, I must agree with Hegel that the slave is actually freer than the master, despite this being an obvious paradox.

Our detachment from our physical environment and nature is, in my perspective, a large part of the reason for our unsustainable habits such as overconsumption, perceived obsolescence, and lack of respect for crafts and skills. We are alienated from our physical world, and we lack insight and skills it takes to shape it (sustainably!) and preserve it.