Kristine H. Harper's Blog, page 8

January 15, 2021

Rewilding

I recently stumbled upon a term that I had never heard before: rewilding. I was watching the TED Talk by British writer and activist George Monbiot, who in this talk tells about his devotion to the term, and I was immediately captivated.

When you look up rewilding the definition goes somewhat like this: rewilding means to restore an area of land to its natural uncultivated state, or to a wild state.

But perhaps rewilding can also concern nurturing an uncultivated side of human nature? I will get back to this, but firstly, let’s take a look at the way Monbiot explains the concept of rewilding in his talk.

Monbiot initiates his explanation of rewilding by talking about the effects of the 1995 reintroduction of wolves in the Yellowstone National Park in the US. The park was suffering from the increased number of deer, because there were no animals to hunt them, and as a result a large part of the diverse vegetation had been reduced. When the wolves were reintroduced at first, as intended, they of course started killing some of the deer in the park.

But importantly; something else slowly started happening as well. As the deer were hunted by the wolfs, they moved away from the valleys where they were vulnerable and could easily get caught, which resulted in the bare valleys quickly turning into forests with a great diversity of trees and other plants. And because hereof, birds started to move in, and the numbers of beavers started to increase, and the dams the beavers build in the valleys created habitats for otters, muskrats, ducks, fish, and reptiles.

The wolves also kept the population of coyotes down, which resulted in the number of rabbits and mice increasing — and that meant more hawks, foxes and badgers. Furthermore, the bear population began to rise; probably because of the berries on all the trees that were growing in the valleys.

On top hereof, the wolves changed the behaviour of the rivers. More pools were formed, more narrow streams were made; all of which is great for wildlife. The reason for the changes was that the regenerating forests stabilized the banks of the rivers, and hence mudslides were limited.

Conclusively, the small number of wolves that were reintroduced to the park not only transformed its ecosystem radically; they also changed its physical geography. They reversed it to a natural state, which allows for the diversity necessary in order to foster resilience.

The wolf-story highlights an important point: Making everything and everyone homogeneous is not a resilient, sustainable way of life. Allowing for and fostering diversity on the other hand is!

Glamping in Yellowstone Park, Montana, July 2017

Glamping in Yellowstone Park, Montana, July 2017In Denmark, where I am from, wolves (that have been extinct for a very long time) were recently seen in the countryside of the Mid and North-Western part of the country. And a lot of residents felt really scared. Even though the number of wolves spotted was extremely low (we are talking somewhere between five and ten), and despite the fact that in Denmark’s neighbouring country Germany wolves have lived freely since 2000 without any registered attacks on humans, people were concerned. The wolf-discussion filled up the news for a while, and there were stories of sheep being eaten by wolfs during the night etc. For and against wolf-groups arose, and families in the areas where the wolfs were spotted were afraid to let their children play outside and of walking their dogs. Hence, in June 2018 it became legal in Denmark to shoot down wolves that were considered a problem. The problematic wolves were defined like this: 1. wolves that are not naturally aversive near people, 2. wolves that prey on farm animals, 3. wolves that attack dogs, and 4. wolves that are dangerous to humans.

Obviously it is uncomfortable to feel threatened. And particularly to feel that your children could be in danger. However, wolfs and other wild carnivores and humans have lived side by side for centuries, and the wolf is an original part of not only the Danish, but the European nature. And, as the Danish Nature Association points out; wolves are natural foresters (as also demonstrated in the Yellowstone Park example), and they fill out a void in the Danish nature, which hasn’t contained large predators for over 200 years. Furthermore, the wolf is an endangered species.

Rewilding involves bringing back some of the missing plants and animals to a region – and then stepping back and allowing for nature to develop its diverse magnificence. It is a way of helping nature finding its own way.

The vast, windswept part of Mid-West Denmark

The vast, windswept part of Mid-West DenmarkAnother dimension of the concept of rewilding that deeply fascinates and resonates with me is the idea of rewilding human nature and human life.

In Monbiot’s TED talk he starts of by talking about how he as a young man spend six years of “wild adventure” in the tropics, and how he, after returning to England found himself ecologically bored — and quickly longing for a richer and rawer life.

Ecologically bored? What does that mean? Or rather, what does it include? When I think of this term, I think of the dullness of experiencing only one, homogenous, tame kind of nature. But being ecologically bored also means that our instincts are dormant and sedated. In our late-modern, capitalistic reality there is no use for natural instincts and intuitive hunches; rather, being able to make rational choices and act in a cultivated, normal, civilised manner is celebrated.

Rewilding one’s life does not (necessarily) mean moving out into the woods to engage in an offline and off-grid lifestyle a la Thoreau. Rewilding is a mindset! And it is closely connected to freedom. Not freedom in the way we usually think of it, as Monbiot rightfully points out in this column: i.e. freedom to develop ones business, to carry guns, to say whatever we want, or to believe in whatever or whoever we want. No, the wild kind of freedom is related to our inner wildness; to listening to our intuition, our instincts, and to going against the societal and cultural norms if necessary.

In this article by Positive News’ Lucy Purdy the following questions in relation to rewilding human nature are raised:

“Just as ecological rewilding succeeds by letting nature do what it is designed to do, could we take the same approach towards ourselves? What would happen if we were more aware of and driven by our own dynamic processes?”

Purdy suggests that we perhaps (just as nature) are tamed and restricted; limited and held down by should-do’s and cultural norms. That we too are becoming uniform and monocultural. That diversity is disappearing – and that that is not a resilient, sustainable way of life.

There is something very Michel Foucault (1926-1984) about this notion. In his seminal work Discipline and Punish from 1975 he argues that modern society is the most efficient “prison” that has ever existed. It doesn’t even need prison guards! Its rules and restrictions are stored in each of us, as well as exercised by each of us. Just like in an actual prison the modern social prison disciplines and forms us into good employees, good consumers, good neighbours, good students, good friends etc. And on top of this we are constantly told through tv-programs, magazines and social media what our bodies should look like, what beauty is, what our homes should look like (and how we should tidy them up), what we should eat, what we can and cannot say etc. etc. No prison can make people do what they willingly do to themselves in our modern social prison.

We have created a world in which we are under constant surveillance by ourselves and others; a world in which we seek to meet societal expectations on everything from what we should look like to where we should go on holiday.

As Monbiot says in the previously mentioned column:

“We entertain the illusion that we have chosen our lives. Why, if this is the case, do our apparent choices differ so little from those of other people? Why do we live and work and travel and eat and dress and entertain ourselves in almost identical fashion?”

I plan to return to Foucault and the “modern prison” (which by the way has become even more efficient since Foucault wrote his book in the 70’s) in future posts, as I am currently writing about his thoughts in my forthcoming book on Anti-trend. And, I recommend highly the podcast Philosophize this! for a more thorough – and very entertaining – introduction to Foucault.

The Kindergarten at Green School Bali is packed with evidence of the children’s wild explorations of nature

The Kindergarten at Green School Bali is packed with evidence of the children’s wild explorations of natureThe longing for rawness, for a rawer life that Monbiot mentions in his TED talk makes me think of our current smooth, friction-less reality. A lack of tactile stimuli characterises our late-modern cityscapes and work spaces. Or rather, a lack of anything that can “endanger” our safe, smooth comfort zones. We shelter ourselves from natural temperatures through air conditioning, we only experience cultivated nature, we celebrate convenience, and we allow for our senses to be tamed and sedated by the smooth surfaces of endless tablets, smartphones and computer screens.

But something is lost in this equation. We have become alienated from the natural world. And when you don’t feel connected to nature, you are, simply put, less inclined to take care of it – and perhaps also more inclined to feel that nature poses a threat (apropos the Danish wolf-story).

Everyday I find myself nurtured by the tactility of these natural, odd-shaped rocks that are laid out on the paths in our garden. I love how rough and uneven they are – and how they store the heath from the sun, and hence feel warm in the evening and slightly cooler in the morning. They are anti-smooth and asymmetrical, and as such; aesthetically pleasing.

Everyday I find myself nurtured by the tactility of these natural, odd-shaped rocks that are laid out on the paths in our garden. I love how rough and uneven they are – and how they store the heath from the sun, and hence feel warm in the evening and slightly cooler in the morning. They are anti-smooth and asymmetrical, and as such; aesthetically pleasing.My friends and family in Denmark often ask me how I can live with the presence of huge spiders and other oversized insects, scorpions, snakes and big bats — not to mention wild dogs, the threat of mosquito borne diseases, and the sudden heavy tropical thunderstorms. The truth is that besides the street dogs, by whom I have felt threatened a few times (but am now finding my way to cope with), I don’t give it much thought. And, the truth is also that I kind of like the wildness and the rawness of this place.

Living in a state of fear and worry is something that you choose. And, as it is with choices; you can also choose not to.

My youngest son’s wonder book. This morning he found a big dead spider and was thrilled to add it to his treasures (despite the fact that it lost a couple of legs in the process).

My youngest son’s wonder book. This morning he found a big dead spider and was thrilled to add it to his treasures (despite the fact that it lost a couple of legs in the process).

January 11, 2021

Interview #7: Evangelia Paliari from The Tribe in Action

I met Evangelia in Bali a couple of years ago, when we both lived in a small eco-village near Green School. Evangelia was at the time writing a dissertation on the Green School called “The New Age Education”, and she is at the moment working on the prospect of starting up a Green School in Greece.

Evangelina is very engaged in permaculture and sustainable living. I remember having many through-provoking talks around the campfire at night with her. When we recently touched base I learned about her new projects and her new tribe.

The Tribe In Action is a NGO founded by Evangelina and her friend Iliana. The Tribe engages in projects that revolve around social entrepreneurship and reforestation.

In this interview Evangelia shares her visions for building a tribe focused on action and change-making, and she furthermore tells about her upcoming reforestation project in Kenya

***

What does sustainability mean to you?Sustainability is a way of being. In its core, it encloses qualities that can be taught and impact one’s physical and mental health and therefore influence the society, the economy and the environment we live in. The world is one of influence.

Part of our energy is used up in the preservation of own body and mind. Beyond that, every particle of our energy is day and night being used in influencing others and are being influenced by them. Personality may be the personal magnetism that produces an impression. Real thoughts, new and genuine and actions that foresee the effect. An effect that follows the cause. So for me sustainability is a martial art that starts from the individual self.

***

How would you describe your current project and organisation?As Iliana (the co-founder of our NGO) says, our guideline can be described by the phrase “Nature for Humanity and vice versa”.

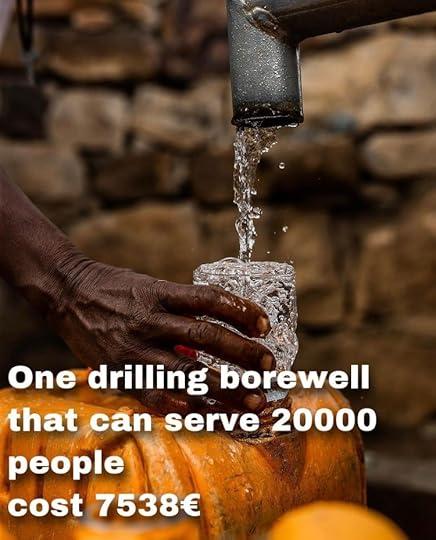

We started The Tribe In Action because we were tired of actions of philanthropy that didn’t have a sense of sustainability and long-term thingking, and therefore wouldn’t last, and henceforth would leave people in need again and again waiting for the charity from others.

We believe in a neo-humanism that supports a sustainable development of existence. Whenever hunger exist, it means there is a lack of food-forests, and it furthermore means that there is a lack of water. It is well comprehended by the movie The boy that harnessed the wind. Watching the movie is an easy way to make awareness viral sometimes rather than explaining techniques and facts.

The Tribe In Action started as a vision (or obsession) of mine. Then Iliana joined and we were two – she says she joined because she loves me and because she dreams of a better world. Now we are a beautiful team of twelve passionate members as well as many volunteers whenever it’s time to act. We are growing, we are becoming a tribe, and it is really fulfilling.

It is also explorative as sometimes we define ourselves through our actions and we learn from each other and we adapt to each other while working as a team.

In our project in Kenya this August, along with Mutuku and our team there in SWECF, we design a land of 30.200 square kilometers, with 3 sand dams, 1 borewell drilling and we plant 60.000 trees while at the same time providing seminars for 24 schools about permaculture and sustainability. That literally means an impact in 500 communities that count around 30.000 people.

We will have an open call for Kenya soon, so whoever wants to join us in Kenya this August can book its seat to fly with us in our dreams and actions.

***

What do you view as the biggest environmental problem?Fear and lack of empathy.

I find that these two elements are the source of all problems in the whole world. I too fall into that trap sometimes. As it is well narrated in the movie I referred before, everything is connected and affected and even a small action can bring a domino that you can not ever imagine.

When there is war it really doesn’t matter who is right or wrong, we are all wrong when this is happening. And the state we are at now started with war. War created terrorism. Terrorism created the attacks in the towers in NYC, this created a chaos in the economy worldwide, which led to companies (supported by banks and government in Africa) to ask for timber for very low prices. People in Africa accepted this because they were afraid of losing their jobs. Deforestation led to drought and flooding. Drought and flooding transformed a land of abundance into nothingness. No food, no water – so people literally starved. Right now many regions in Africa are trying to thrive again with a hope by the help of Chinese or Indians that have arrived in lands to reach cheaper labor costs. This flow is not sustainable.

Whatever we do, echoes to eternity. So let’s do something good.

October 22, 2020

Making a difference

This is a story that I have been looking forward to write. It is a story of a friendship between two boys from very different cultural backgrounds. And it is furthermore a story of the fact that we are all able to make a difference; of the importance of never feeling that even the smallest step we take towards helping someone or preserving something that is important to us is too small, and that we should never excuse not acting when we deep down feel like we should, could and want to by the fact that we are too young or old, or too small a part of a bigger picture, or whichever other reason we might use to convince ourselves to just accept the status quo.

My oldest son Marius, who is now 13 years old, met his friend Putu on the first day of school, when we just moved to Bali nearly two and a half years ago. Marius felt alone and insecure, and furthermore a bit insecure about speaking English. Putu was the only one who reached out to him and showed him around the campus, and they quickly developed a beautiful friendship based on the same sense of humor, a love for bicycling and for running around the jungle during recess.

[image error]Marius and Putu June 2020

Putu lives with his lovely mother in a small village close to Ubud, called Sibang, which was also where we lived in Bali. Putu’s father died when he was very young, and his mother works as a gardener and earns merely enough for their daily needs, and for their offerings to the spirits and Hindu Gods, as well as for religious ceremonies (which are a crucial part of the Balinese people’s lives). Putu’s life differs on almost every level from Marius’, and yet all their differences never mattered as the bond between them is based on empathy and respect.

I realised another profound level of Marius and Putu’s friendship one evening, as I was riding home from the beach with Marius on the back of my scooter. Marius said to me that getting to know Putu had made him realise that wealth is not only about money. He said: “Putu has a great life; he lives right next to school and therefore doesn’t have to ride a car for half an hour every morning and afternoon like lots of the other kids, he and his mum have a great relationship, they laugh a lot, he has two dogs, and he can bicycle around to see his friends after school. In a sense he is richer than many other people I know”

He also told me that Putu has never left Bali and dreams of one day travelling to Java – which in the light of all the many overseas travels most Green School families do almost seemed unbelievably humble. And then I realised that Marius was aware of exactly that humbleness, and that he treasured it.

We learn a lot from friends that come from entirely different cultural backgrounds than us. We learn about other traditions and ways of life – and furthermore, such friendships might encourage us to question things we take for granted due to our cultural fundamental assumptions, such as what wealth or succes means or what a good life consists of. And importantly, we learn that we, despite all our differences, might have more in common than with people who grew up in the house next door and come from the exact same cultural and societal background as us.

[image error]Putu and his mother, June 2020

In July 2020 we left Bali and moved back to Europe, and Marius and Putu had to say goodbye to each other.

Before we left Marius said to me: “I really want to help Putu and his mum renovate their house, because the roof is leaking. Could we make a fundraiser?” I loved that question! I have absolutely no experience with fundraising what so ever, but at The Green School Marius had learned about doing so as a way of kickstarting sustainable projects and conducting charity work. And so he and I did a bit of research and found a platform we could use, and over the week of us packing our suitcases and saying farewell to beautiful Bali, Marius took photos of Putu’s house, wrote a text about the project, and made a short video. As soon as we got to Europe he set up a fundraiser.

Marius wrote:

Dear friends and family,

Putu Darmajasa is my good friend who I met at school when I lived in Bali. He lives in a small village called Sibang in Bali, Indonesia with his mum. He is in 8th grade. When Putu was little, his dad was hit in the head by a coconut that fell from a tall palm tree when he was working in the fields, which killed him. Since then, Putu and his mum have been alone. His mum works as a gardener at a school in Sibang, and only earns enough for them to take care of their daily needs. Their house is in need of major repairs but they have no money to spend on renovations. The roof is leaking, the walls need repairing and they don’t have access to drinking water in the house (they have to get it from a common well).

I would really like to help Putu, as he is a great friend and a really good person. I hope you will help me help him, as it would make a huge difference to him and his mum.

Thank you for supporting this project.

Marius

It was amazing to experience the level of support for the project. Within a couple of weeks Marius had reached the goal he set for the fundraiser, and he could close it and send the money to Bali. Via the amazing support of Stacia Acker (the mother of a girl in Marius’ class at The Green School) the renovation of the house began.

Today, I just received the last photos from the house-renovation (thank you Stacia!). Not only did both roofs of the home get totally replaced, there was also money for the dentist, as Putu has had some trouble with his teeth for a while.

In the below photos you can see the roofs before and after the renovation.

[image error]The work begins, August 2020

[image error]Before the renovation of the first part of the house

[image error]

[image error]And after

[image error]

[image error]The renovation of the second part of the home

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]October 2020

[image error]

Thank you so much to all the amazing people, who have supported the project – you are a reminder that it is indeed possible to make a difference.

With love from Marius and Putu.

October 16, 2020

The anti-trendy design object

As mentioned on several occasions I am in the finishing process of editing and illustrating my new book Anti-trend – resilient design and the art of sustainable living. And, as a part hereof I am concretising the characteristics and properties of the anti-trendy design-object in comparison with the trendy design object. In this post I will share some of my thoughts regarding these differences.

The anti-trendy design-objectThe trendy design-objectResilientFleetingSuper long-lived or super short-lived (permanence or sustainable planned obsolescence)Perceived as obsolete after a short period of usage (despite being made from materials that can last for almost ever)HeavyLightAlterable, adaptable, in flowStaticFlexibleFixedRepairableUn-repairableRawnessSmoothnessOpen, ever evolvingClosedUndone or underdone (usage “finishes” it)Declines or worsens when usedCircular, iterativeLinearFriction, texturesqueEvenness, “glittery” surfacesChallenging expression or functionalities (might offer new ways of life or nudge the user to alter her habits)Convenience (easily understandable, usable and decodable)Uneven, variated textures (tactilely nourishing)Picture perfect (even the slightest blemish ruins its appearance)DiverseHomogeneousEncourages wholesome rhythmsPraises newnessEmbraces and celebrates decayDecay makes it obsoleteUpcycled or craftedMade from virgin materialsSharableMade to be consumed (and hence replaced)Cherishes innovation (made to encourage sustainable living)Conventional (made to “fit in”)Challenges status symbolsMade to be admired by peers

As the table shows, the anti-trendy design object is generally characterised by being resilient, flexible, alterable, and repairable. But it is also interlinked with more abstract characteristics such as heaviness and rawness (which are features that I in my upcoming book investigate as both philosophical qualities as well as concrete design guidelines). These features are interlinked with the friction and openness of the anti-trendy design-object, as they revolve around an object’s “ability” to nourish the receiver’s senses by introducing a degree of ductility and “graininess” or coarseness to the user’s daily life; they are not easily or quickly digestible or consumable, and hence they require time to consume.

[image error]Signature Shirt (2020) by Danish Sustainable fashion brand La Femme Rousse. The shirt is made from discarded, upcycled bedlinen. It is hand-painted, and the buttons are made out of 80% food waste. A shirt like this can easily hold user traces and stains, and hence, usage doesn’t make its value demolish. Furthermore, due to its patterns that ensure a degree of rawness, repairs will not appear as blemishes.

The anti-trendy object is furthermore underdone in the sense that when it is released into the world by the designer it is not yet completely finished; usage finishes it (i.e. if it makes sense to talk about it ever being finished), as the object is created to develop, to be open, and to embrace decay.

Moreover, the anti-trendy design object is characterised by gently pushing or “nudging” the user towards sustainable living; whether that means inviting more textural stimulation into her life by e.g. investing in handcrafted artefacts that are anti-smooth or texturesque, engaging in nourishing daily rhythms that can provide her life with a sense of direction and with the beauty of continuity and perseverance, or by allowing for more rawness, inconvenience and heaviness (in the wholesome sense of these word, which I discuss thoroughly in Anti-trend).

[image error]Products made by hands for hands to touch nourishes the tactile sense by offering an aesthetically pleasing uneven anti-smoothness. Photo from the Sudaji Weavers in North Bali.

The trendy design object is made to develop from being new, shiny and attractive at its peak (i.e. when it is brand new and newly acquired by the consumer) to slowly, or perhaps even very quickly, being experienced as unattractive and obsolete. In that sense the trendy design object is linear: it moves from a starting point to an end point, and the development is designed to be a downgrade. The trendy object is in other words created to be consumed in the most literal sense of the term; to get all its nutrients sucked out of it (so to speak), and to then be discarded. The anti-trendy design object on the other hand is circular, or rather, it has a circular lifespan, or maybe even more correctly; an iterative lifespan.

Using the term iterative rather than circular is done to emphasize the anti-trendy design object’s inherent ability to develop. An iterative process involves doing something time and again, usually to improve it. And, this is exactly what happens when the anti-trendy object is being used. The more the object is used the better it gets; it matures and develops, and it supports the functional and aesthetic needs of the user.

Nevertheless, despite all the notions on longevity the sustainable anti-trendy design object can also be created to be super short-lived, as highlighted in the about table. But unlike the trendy product, the sustainable short-lived, anti-trendy object is not created to fulfil the late-modern consumers’ ever-changing need for attention and approving gazes from peers. Rather, it is based on planned obsolescence and intentional fleetingness or natural deterioration.

Whereas trends nurture and cultivate a linear desire for the newest looks and likings, anti-trends encourage longevity and flow.

October 15, 2020

Mono no Aware

Because my main focus when working with sustainability is aesthetics I am always intrigued when I stumble upon aesthetic philosophies, methodologies or approaches. And my latest finding is the Japanese term of mono no aware.

The term is a combination of aware, which means sensitivity, feeling or pathos, and mono, which means things. The mixture of these words, which can be translated as the pathos or the feeling of things indicates an awareness of the fleeting, impermanent nature of life, as well as a recognition of this impermanence.

Awareness of impermanence contains both sadness and appreciation. In Japanese poetry it is often described by the ephemeral nature of beauty and the melancholic, and beautiful (!), realisation that nothing lasts forever.

“If man were never to fade away like the dews of Adashino, never to vanish like the smoke over Toribeyama, how things would lose their power to move us! The most precious thing in life is its uncertainty”

Yoshida Kenkō (Japanese poet)

[image error]

Mono no aware contains an encouragement to enjoy life, to be present and to notice and appreciate our physical surroundings; the nature around us and the physical things in our milieu. It is an incentive to enjoy the pathos or the ambience of the things with which we share our lives – and it is, importantly, a hymn to the constant shifts around us (and within us) that manifest in our physical surroundings; seasons that change, trees that bloom and wither, rainstorms that move in and turn heaven and sea into one only to clear up into blueness or the red-purple bliss of a sunset, flowers that blossom for a short while and then deteriorate (and that shortly before deterioration smells the sweetest and the most alluring), fruits that are juicy and fragrant, but only last a short while before they start to rot, or animals that die and turn into food for other animals or nourish the soil beneath them. – But also the changes in our physical artefacts: traces of usage on a beloved chair, the wear and tear that manifests on a jacket or a pair of cherished trousers and that tell stories of the owner and her life and habits, or the decay of an old building that has hosted generations of people and has been moulded by their lives. Mono no aware holds an awareness of the powerful sentiments that physical objects carry and can evoke in us.

Mono no aware is hence the ultimate ode to everything always being in flux (as a wise man thousands of years ago said): to the shifts and alterations that characterise the world we live in as well as human life. It celebrates, rather than bemoans, deterioration, decay, things and experiences coming to an end, shifts and alterations. It is a state of mind that you reach when you learn to appreciates transience and impermanence and learn that the most satisfying aesthetic nourishment is to be found in ephemerality and in the changes in and around us. It a state of acceptance and it bring harmony.

[image error]

Another thought-provoking aspect of mono no aware is that it underlines the human tendency to clinginess as a major obstacle on our path towards fulfilment. Mono no aware celebrate Mujo. Mujo is a word originated in Buddhism, and summarily it means impermanence, transience or mutability.

Mujo is a particularly important concept to understand in relation to the human strive for happiness. If all things are impermanent and hence never-ending subjects to change, the human need for persistence and security, which materialises in our tendency to accumulate lots of possessions that we store in our increasingly big home-boxes, and the security-hungry need to primarily stay and live in one place the majority of our lives. The result of this clinginess and heaviness is the unsatisfactory nature of ordinary, unenlightened human existence. We seem to think that by changing nothing we can capture and secure the status quo — but as everything is always in flux, including our own minds and desires, this is the direct pathway to dissatisfaction. Being overly attached and forcefully trying to fixate and hold on to things and situations causes what in Buddhism is called Ku, which translated to emptiness. Our lives are not fixed, but dynamic, constantly changing and evolving.

[image error]

The above conclusion makes me wonder about two things: 1. why most things are created out of materials that last for a very, very long time, well almost forever, and 2. why more things are not designed to be alterable, moudable, or even fleeting. I will return to these questions in a forthcoming post, as they are closely interrelated with my anti-trend research.

If you want to read more about mono no aware I recommend this description of Japanese aesthetics, this article on mono no aware as well as this one, and this book.

October 11, 2020

The end of the growth-mindset

I recently re-read the 1972 book The Limits to Growth. The book was published by the think tank The Club of Rome and has since its publication been sold in more than 30 million copies and translated to 30 languages. In other words, there has been an immense interest in the topic, and there still is; the message seems to be successively timely despite its data being decades old.

The researchers behind the book examine five basic factors: population increase, agricultural production, nonrenewable resource depletion, industrial output, and pollution generation, and demonstrated that the interaction between these factors limit growth. Furthermore they demonstrate that unless we take seriously that there are indeed limits to growth the development will end up with a collapse before 2070. A collapse of our economy, our environment as well as a population collapse. They call this scenario the “business as usual” scenario.

Population cannot grow without food, food production is increased by growth of capital, more capital requires more resources, discarded resources become pollution, pollution interferes with the growth of both population and food.

The Limits to Growth, 1972

If we keep drawing on the world’s resources faster than they can be restored, we will reach a point of shortage and collapse. But fortunately, the “business as usual” scenario is not the only plausible scenario presented in the book. The researchers also line up other scenarios; twelve different ones actually, which demonstrate different possible patterns as well as environmental outcomes of world-development over two centuries from 1900 to 2100. And, they reach the conclusion that there (at their present time) is still room to grow safely whilst examining longer-term options.

However, in 1992 a 20-year update was made to the book and the book Beyond the Limits was published. And, a rather different plot was presented here: humanity is moving deeper and deeper into unsustainable territory, the researchers stated. There is no longer space to grow safely. And then, 10 years later the study Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update was published and the researchers conclude that humanity is now dangerously in a state of overshoot.

To overshoot means to go too far, to grow so large so quickly that limits are exceeded. When an overshoot occurs, it induces stresses that begin to slow and stop growth. The three causes of overshoot are always the same, at any scale from personal to planetary. First, there is growth, acceleration, rapid change. Second, there is some form of limit or barrier, beyond which the moving system may not safely go. Third, there is a delay or mistake in the perceptions and the responses that try to keep the system within its limits. The delays can arise from inattention, faulty data, a false theory about how the system responds, deliberate efforts to mislead, or from momentum that prevents the system from being stopped quickly.

Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update

In the 30-year update the previous twelve scenarios are reduced to ten, and most of these scenarios result in overshoot and collapse. The world as we know it will cave in to pollution, food shortage, over-population, and economic inequality, and eventually collapse.

Now in year 2020 it is nearly 50 years ago that Limits to Growth was published. And where are we now? In a state of overshoot overdrive?

The Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update suggests three different ways to respond to over-usage of ressources and pollution emissions beyond sustainable limits.

The first one involves disguising and denying the signals of overshoot; by for example making use of air conditioners to bring relief from global warming, or to ship toxic waste for disposal in distant regions (which is obviously already being done on a large scale). The second way is to make use of technical fixes like the development of less polluting cars, electric vehicles or carbon filters (this is also a common current way of eradicating guilt-feelings from consumers by encouraging green consumption, and hence for legitimising continuous growth). However, this way doesn’t eliminate the cause of the problem either.

The third way of dealing with over-pollution and shortage of natural ressources is the only one that looks into the underlying cause of the state of affairs in stead of just treating the symptoms. This way involves acknowledging that our current socioeconomic system has overshot its limits, and hence that it must be altered. This scenario involves a rise of a societal need to pursue goals that are more satisfying and sustainable than perpetual material growth. In other words, what would really make a difference and what could change the path towards overshoot and ecological collapse would be if everybody decided to moderate their material lifestyles! It is our culture and our mindset that constitute the biggest obstacle when it comes to turning around the state of affairs.

Now, this last very important take-away reminds me of two things: 1. of degrowth, and 2. of the importance of reducing consumption, and not only reducing it a little bit, but reducing it radically (which I normally preach, when I talk about aesthetic sustainability).

[image error]A secondhand market in Denpasar, Bali. Overflowing with unwanted, yet perfectly fine discarded clothes and accessories.

Freedom and diversity

I will never forget listening to a radio show once about freedom and cultural differences on which an elderly, wise-sounding indian man stated that to him freedom is the freedom from ambitions. That was the weirdest thing I had ever heard! Freedom from ambitions?! The core of the societal norms and cultural consensus that I am a part of and have grown up with is that one should be ambitious and always strive for more; more succes, more money, more acknowledgment, more material belongings. And that being ambitious is an important drive and the antithesis of being lazy and lethargic. So, how could this man say this? What exactly did he mean? I could feel that the statement provoked me slightly, but that it also made me curious; what did he know that I wasn’t aware of? How could he sound so certain? Could feeling truly free really involve being freed from ambitions? What if the antithesis to being ambitious was not lethargy, but fulfilment and purpose?

Many years later I stumbled upon degrowth, and this term made me think of what the old man said.

The degrowth movement constitutes a reaction towards the unsustainable growth or “more wants more” model that governs our post-modern capitalistic reality. And, degrowth involves an important concept that is very aligned with the old man’s statement, namely voluntary simplicity.

“In other words, voluntary simplicity involves embracing a minimal “sufficient” material standard of living, in exchange for more time and freedom to pursue other life goals, such as community or social engagements, more time with family, artistic or intellectual projects, home-based production, more fulfilling employment, political participation, spiritual exploration, relaxation, pleasure-seeking, and so on – none of which need to rely on money, or much money.”

Giacomo et al (2015). Degrowth – A Vocabulary for a new Era

Perhaps, being on the constant chase for more and better burdens our individual wellbeing and inner ecosystem in a similar way that economic growth-models overwhelm the natural environment and put colossal strain on our natural ressources. And furthermore, perhaps the growth-mindset fosters homogeneity.

Let me elaborate. Exponential growth destroys biodiversity: for example, when wild nature is transformed into homogenous farmland with the purpose of effectively producing more crops diverse species of insects, animals and plants suffer and disappear. And similarly, our cultural focus on growth and efficiency, on wanting more (for less), and on optimising value chains and production models have led to a homogenous, globalised world, in which traditional crafts-traditions are suffering due to the fact that they cannot compete with cheap mass-produced things, and in which your can buy everything everywhere and at any time of the year which is devaluating and makes nothing feel truly special (and which obviously strains the ecosystem).

Fortunately though, as previously written about, the number one rule of thumb when working with cultural tendencies is the following: if there is an overload of something the need or longing for the opposite will arise, so that a balancing point can be established. And the need for degrowth and for diversity is definitely present. And henceforth the book on the limits of growth written in the 70’s is still relevant and timely, as it stirs up our bsic assumptions that might seem fundamental, but nevertheless are changeable and fluid.

Importantly though, as this very recommendable article points out; we are not at all headed towards an end to economic growth, on the contrary actually:

While we in the west talk about the limits of growth, those in Asia, Latin America and Africa are attempting to realise their dreams of a better life – modern homes, sufficient food, televisions, computers, telephones, fashionable clothes and the freedom to travel both at home and abroad. Nothing and no one will persuade them to abandon these goals. The question is whether this enormous drive for more goods and services will end in an environmental collapse or whether it can be guided into a more sustainable track.

And how can you blame people of dreaming of comfort, fashion and consumer-luxury? After all, exactly that; i.e. the joy and satisfaction of consumption and of filling your home-box with lots and lots of things is what we are being told again and again by the entertainment industry is the path to happiness.

The last sentence of the above quote contains a bit of hope though. Maybe things could still be turned around if only mass-consumption was guided towards a more sustainable track. But it requires a fundamental change in the characteristics of mass-produced products, and importantly, it requires a radical alteration of mainstream statussymbols — an alteration headed towards the values of creativity, mending-mentalities and the beauty of simplicity.

[image error]A beautiful kingfisher, killed by our cat Eddie

One of the main problem with the way we are currently consuming (which is excessive and gratuitous) and the way the things we consume are designed is the amount of waste it produces.

In nature there is no waste. Leaves that fall from a tree nourish the soil that they fall into, an animal that dies turns into food for another animal or it deteriorates and fertilizes the earth, decomposing fruit is eaten by ants and other insects etc. etc. In a natural circular system everything is always altering, always in flux, and nothing is wasted, nothing is superfluous. In our “circular” systems we are told that something similar to nature’s ingenious “waste-management” is happening. But the truth is that static things made to fulfil a temporary consumer-need to fit in, to feel trendy or admired, or to be pampered are not reusable; they turn into the trash the second they are casted off by the owner. They are by definition superfluous.

September 21, 2020

Interview #6: Balinese art activist Slinat

Everyone who lives in Bali or even just stays in Bali for a short while will know his murals. Slinat aka Silly in Art runs the small Art of Whatever Store in the island’s capital Denpasar, where he sells second hand garments upcycled with art in the words most literal sense; “upcycling means to recycle (something) in such a way that the resulting product is of a higher value than the original item”.

Additionally, his shop is a gallery for his artwork and his customers can furthermore deliver their favourite shirt, jacket, jeans, shoes, skateboard etc., and Slinat will decorate it with a one-of-a-kind art-piece. Finally, Slinat is, as mentioned, an amazing street artist and the man behind the many intriguing murals you will find all over the Southern part of Bali.

Most on Slinat’s artwork is a visual comment on the development in Bali; the movement from an agricultural, traditional society to a society that bases its income on tourism, the increased air and plastic pollution on the island, on the damages from mass-tourism; on nature and on culture, on disrespect for nature, and on the absurdity in holy balinese ceremonies being reduced to the perfect backdrop for a tourist photo (“Take my picture and say that my culture is beautiful”, as it says below one of his paintings of a balinese woman showing her middle finger).

[image error]Slinat, work in process, Denpasar 2020

In this interview, I will share Slinat’s thoughts on pollution and the consequences of mass-tourism, but also a variety of his amazing artwork; his pieces are so captivating and thought-provoking that words are almost redundant.

Please make sure to visit his instagram account to see more and if you are in Bali, visit his shop in Denpasar.

***

What does sustainability mean to you?

“To me, sustainability is all about respecting nature. The biggest threat to nature is pollution, because it creates an imbalance in the natural cycles, and hence the flow is hampered.”

[image error]“Kenangan Kesuburan” (Fertility memories) 2020

“I furthermore work a lot with the environmental consequences of mass-tourism in Bali. My emblem therefore is an ancient Balinese man or woman wearing a gas mask.

Lots of tourist postcards and souvenirs picture ancient Balinese people wearing traditional, ceremonial clothes. These photos are used as promotion tools by the tourist industry.”

[image error]“Dekonstruksi Ingatan” (Deconstruction memory) 2019

“Tourism on this island continues to grow. Land that should be used for wild nature to thrive and for sustainable farming is being turned into hotels and air-conditioned villas made of concrete. And the same goes for the ocean; it is exploited and needs to be restored.

Damage to the natural environment on this island caused by the greedy tourism industry continues to increase, and it only benefits the investors. But an additional problem is that the local people who happen to live in tourist areas get spoiled by and grow dependent on the cash flow. Many local people who previously worked in nature, which is a much slower process (for example seaweed farmers or rice farmers) have promptly changed their profession when tourism have started to grow in their areas and have become villa entrepreneurs or keepers, or service employees in hotels, bars or restaurants.”

[image error]“Save your culture, sell your land” 2018

“An example of the disturbance of the natural cycle is the following: when the seaweed farmers stop farming seaweed in order to focus on servicing tourists, and the areas for seaweed farming turn into crowded tourist areas, turtles who naturally inhabit such areas, because they look for food here, become endangered, and the natural balance, including the natural food chain, collapses.”

Seaweed farming is, as a sidenote, often highlighted by conservationists as a sustainable industry worth preserving, as it causes very little or no damage to the environment and allows reefs to flourish unencumbered by human degradation.”

[image error]“Visit Bali” 2019

“Indirectly, and even directly, mass-tourism changes the cycle that exists in nature as well as the balance between nature and people.

But despite hereof, the government in Bali is very focused on developing and boosting the tourist industry, which is expressed in the large number of hotels being built all over Bali.

I guess the hope is that the Balinese people can earn a good living from tourism. But now, during the Covid 19 pandemic close to 100% of tourism has stopped, and consequently people are confused and scared because they have lost their jobs and hereby their monthly income.”

[image error]“Oleg” 2018

“Meanwhile, here in Bali there are many other potentials that require more attention from the government, such as for example agriculture. Bali has a lot of rice fields and the natural irrigation system in Bali, or the subak, which consists of a system of intertwined weirs and canals that draw from a single water source, been in decline for a while now and is slowly deteriorating; it needs renovation.

Furthermore, local fishermen should be supported as they carry out the cycle of life in a natural, non-exploitable manner.”

[image error]“Nyepi” 2020

***

How would you describe your art?

“I distribute my artwork in public spaces and I make indoor works as well. I often use secondhand items.”

As written above, Slinat upcycles secondhand garments by decorating them with art; you can see beautiful examples thereof at Art of Whatever. This way of upcycling is intriguing to me; Slinat turns castoff items into one-of-a-kind objects or what you could describe as soft wearable galleries. This is the ultimate upgrade of a thing that was experienced as obsolete by its previous owner and thrown away.

[image error]Upcycled notebook by Slinat

“For a while now I have been working with the X Visit Bali Year X theme, which is a parody of the tourist industry in Bali that a few years ago used this slogan. In my X Visit Bali Year” pieces I don’t picture the archetypical exotic Bali or “Bali as the last paradise”, but rather traditionally dressed local people wearing gas masks and polluted nature.”

***

September 2, 2020

The anti-trendy design object

As mentioned on several occasions I am in the finishing process of writing and illustrating my new book Anti-trend – resilient design and the art of sustainable living. And, as a part hereof I am concretising the characteristics and properties of the anti-trendy design-object in comparison with the trendy design-object. In this post I will share some of my thoughts regarding these differences.

The anti-trendy design-object

The trendy design-object

Resilient

Fleeting

Super long-lived or super short-lived (permanence or sustainable planned obsolescence)

Perceived as obsolete after a short period of usage (despite being made from materials that can last for almost ever)

Heavy

Light

Alterable, adaptable, in flow

Static

Flexible

Fixed

Repairable

Un-repairable

Rawness

Smoothness

Open, ever evolving

Closed

Undone or underdone (usage “finishes” it)

Declines or worsens when used

Circular, iterative

Linear

Friction, texturesque

Evenness, “glittery” surfaces

Challenging expression or functionalities (might offer new ways of life or nudge the user to alter her habits)

Convenience (easily understandable, usable and decodable)

Uneven, variated textures (tactilely nourishing)

Picture perfect (even the slightest blemish ruins its appearance)

Diverse

Homogeneous

Encourages wholesome rhythms

Praises newness

Embraces and celebrates decay

Decay makes it obsolete

Upcycled or crafted

Made from virgin materials

Sharable

Made to be consumed (and hence replaced)

Cherishes innovation (made to encourage sustainable living)

Conventional (made to “fit in”)

Challenges status symbols

Made to be admired by peers

As the table shows, the anti-trendy design-object is generally characterised by being resilient, flexible, alterable, and repairable. But it is also interlinked with more abstract characteristics such as heaviness and rawness (which are features that I in my upcoming book investigate as both philosophical qualities as well as concrete design guidelines). These features are interlinked with the friction and openness of the anti-trendy design-object, as they revolve around an object’s “ability” to nourish the receiver’s senses by introducing a degree of ductility and “graininess” or coarseness to the user’s daily life; they are not easily or quickly digestible or consumable, and hence they require time to consume.

[image error]Signature Shirt (2020) by Danish Sustainable fashion brand La Femme Rousse. The shirt is made from discarded, upcycled bedlinen. It is hand-painted, and the buttons are made out of 80% food waste. A shirt like this can easily hold user traces and stains, and hence, usage doesn’t make its value demolish. Furthermore, due to its patterns that ensure a degree of rawness, repairs will not appear as blemishes.

The anti-trendy object is furthermore underdone in the sense that when it is released into the world by the designer it is not yet completely finished; usage finishes it (i.e. if it makes sense to talk about it ever being finished), as the object is created to develop, to be open, and to embrace decay.

Moreover, the anti-trendy design-object is characterised by gently pushing or “nudging” the user towards sustainable living; whether that means inviting more textural stimulation into her life by e.g. investing in handcrafted artefacts that are anti-smooth or texturesque, engaging in nourishing daily rhythms that can provide her life with a sense of direction and with the beauty of continuity and perseverance, or by allowing for more rawness, inconvenience and heaviness (in the wholesome sense of these word, which I discuss thoroughly in Anti-trend).

[image error]Products made by hands for hands to touch nourishes the tactile sense by offering an aesthetically pleasing uneven anti-smoothness. Photo from the Sudaji Weavers in North Bali.

The trendy design-object is made to develop from being new, shiny and attractive at its peak (i.e. when it is brand new and newly acquired by the consumer) to slowly, or perhaps even very quickly, being experienced as unattractive and obsolete. In that sense the trendy design-object is linear: it moves from a starting point to an end point, and the development is designed to be a downgrade. The trendy object is in other words created to be consumed in the most literal sense of the term; to get all its nutrients sucked out of it (so to speak), and to then be discarded. The anti-trendy design-object on the other hand is circular, or rather, it has a circular lifespan, or maybe even more correctly; an iterative lifespan.

Using the term iterative rather than circular is done to emphasize the anti-trendy design-object’s inherent ability to develop. An iterative process involves doing something time and again, usually to improve it. And, this is exactly what happens when the anti-trendy object is being used. The more the object is used the better it gets; it matures and develops, and it supports the functional and aesthetic needs of the user.

Nevertheless, despite all the notions on longevity the anti-trendy design object can also be created to be super short lived, as highlighted in the about table. But unlike the trendy product, the sustainable short-lived, anti-trendy object is not created to fulfil the late-modern consumers’ ever-changing need for attention and approving gazes from peers. Rather, it is based on planned obsolescence and intentional fleetingness or natural deterioration. Whereas trends nurture and cultivate a linear desire for the newest looks and likings, anti-trends encourage longevity and flow.

August 21, 2020

Aesthetically sustainable woven fabrics made in North Bali

There is a small village in North Bali in the mountainous district of Sawan called Sudaji. It is surrounded by papaya and clove fields, rice terraces, coconut palms, and teak and durian trees. People here work as farmers and artisans and have done so for generations. The village is not only a long windy drive from the tourist filled south part of Bali with its fancy beach clubs, large hotels and noisy bars, it is a world away. Actually, the first time I arrived in the village 4 years ago, I felt like I had travelled in time.

In this village, a collective of female weavers create the most beautiful, colourful, detail saturated fabrics and sarongs. I have previously written about the Sudaji weavers, and have for a long time now followed their work. With this article my mission is to spread the word of this wonderful, peaceful place, and support their beautiful work.

[image error]Meet Ketut Suciningsih, she is 35 years old and has been working for 7 years as a weaver.

For four months now the weaving collective has been shut down due to Covid19. This means no income what so ever for the weavers. The collective has slowly started up weaving fabrics and sarongs again, but due to no foreigners visiting Bali at the moment the vast majority of customers are missing. And, as the weavers only get paid if their pieces are sold this means that they are currently working for free.

However, even before the pandemic the weaving collective was struggling. We live in a world in which craftsmanship is rarely appreciated. Why pay more for a handmade piece of clothing, a crafted piece of furniture, or a ceramics bowl that carries traces of the creation-process, if you can buy a mass-produced object that resembles such pieces and in addition costs a fraction of the price?

Well honestly, there are many reasons for doing so. One of them being the fact that craftsmanship and artisan knowledge is extinct, and that we are currently in the process of destroying vast human cultural heritages — just by our overconsumption of cheaply manufactured goods.

Another reason is that the aesthetic nourishment that a well-crafted object made by the hands of a skilled artisan contains is of great importance to our human well-being. Not least in an era in which we are increasingly deprived of hands-on, offline activities and experiences. The beauty of a beautifully handmade object, whether this being a bedspread, a chair or a vase, increases our daily wellbeing by offering us the pleasure of continuously using an aesthetically pleasing object as well as the pleasure of experiencing such an object embracing traces of usage in a flattering way. This kind of human wellbeing furthermore increases our ability to live sustainably, as it decreases our need for new things and hence makes it easier for us to reduce our consumption.

[image error]This is Nengah Ariani. She is 30 years old and her son is 2. She has worked as a weaver for 5 years.

The weavers at the Sudaji weaver-collective bring their children to work, which enables them to continuously refine their weaving skills, master the complex traditional patterns, and make their own money. The children who come to work with their mothers (either all day or after school) are generally between one and ten years old, and whilst the smallest ones are breastfed and pampered when needed, the bigger ones seem to have a wonderful companionship and a lot of fun.

Workspaces like the weavers’ collective in Sudaji are empowering women, who would otherwise be unable to work (due to obligations at home, cultural boundaries and traditional gender roles) and enjoy the freedom and status that comes with earning one’s own income.

[image error]The weaving collective uses naturally dyed cotton from Tarum Bali.

[image error]Meet Luh Reniasih. She is 41th years old and has been weaving for 5 years.

But the skilled weavers are an endangered species, as traditional crafts-traditions are facing extinction in the majority of the world. They are threatened due to societal and cultural developments, aesthetic challenges, and particularly due to the fact that they cannot keep up with the speed and efficiency of the industrial evolution.

[image error]Detail from one of the complex patterns.

Together with my partner Putu Shelly from Omunity Bali I am determined to help the weavers from Sudaji in order to ensure that this collective of talented artisans will not be come yet another story of local craftsmanship that didn’t survive the competition from mass-production.

I hope you will help us support these immensely skilled crafts-women by purchasing one or more of their beautiful sarongs, which besides a traditional sarong can be used as bedspreads, tablecloths or as fabrics for dresses, kimonos, shirts, pillows etc.

[image error]A couple of the sweet children who hang out at their mum’s workspace

Please visit the Sudaji Weavers’ Etsy shop which is being set up at the moment. Soon the online shop will be filled with beautiful fabrics and sarongs, which can be shipped to anywhere in the world (through my Instagram account I will keep you posted on when new fabrics are uploaded). All purchases will go uncut to the weavers.

August 9, 2020

Nomadic sustainable living

As I am sitting here looking out at my bougainvillea covered courtyard in our newly rented town house in a small town in Mallorca, Spain, I feel overwhelmed with calmness. I have spent the past ten days house hunting, unpacking our (six, six!) suitcases, and equipping our new house with necessities that were missing – like kitchenware, bedsheets and towels and a few pieces of furniture… and now suddenly, it feels like a home. Yes, it would be nice with some more curtains, and no we haven’t yet hung our pictures on the walls, and yes we could do with a few more lamps and some more comfortable chairs etc. But, the house is now liveable. Well, even more than liveable. It is rather comfortable and homely – as well as charming and quirky.

[image error]The intensely nourishing magenta makes me think of Kandinsky and his amazing ability to describe colours with adjectives that are usually interlinked with taste and scent experiences.

Limiting one’s personal belongings to a minimum of clothes, books, toys (if kids are involved) and personal ornaments that have an “instant home-effect” makes moving around the world fairly easy. But in order to live a nomadic lifestyle, and hence enjoy the freedom of being able to pull up stakes, owning a minimum of things is not quite enough. One needs to be ok with some crucial factors: 1) that working alone most of the time is the norm 2) that things might not always turn out the way that you imagined (generally they actually don’t), 3) that convenience is one’s enemy, well at least if living sustainably is a goal, because it tends to make one go down the quick-fix consumer path, and that 4) that you leave everything and everyone well-known behind, and that in the beginning you may feel lonely.

Living a nomadic life in a sustainable and responsible manner does not involve convenience or smoothness; rather, it is a celebration of “life being in flux” (as the Greek philosopher Heraclitus so eloquently put is thousands of years ago), of adaptability, and of the fact that deliberately inviting a degree of “hardship” into one’s life can be extremely nourishing and edifying.

Responsible nomadic living furthermore involves knowing how to quickly “plug in” in the sense that one understands what is needed in order to be able to work, cook, wash clothes, get around etc. And it furthermore involves trusting trusting that communities are everywhere and that it is only a matter of time before one will find one to embrace and get involved in.

[image error]Still a spectator, still a newcomer.

In my upcoming book on Anti-trend, I describe the most sustainable way of life as resilient and heavy. Pursuing lightness and convenience generally leads to unsustainable decisions, both in relation to consumption and in relation to lifestyle-choices. This being said, engaging in a nomadic lifestyle is of course far from the only way of living sustainably. However, as sustainable nomadic living is the theme of this article, it is important to point out that when moving around the world with one’s family it is very easy to fall into the trap of filling one’s new home with cheap mass-produced goods, as so much new stuff is needed – and needed urgently.

The most sustainable purchases if one needs a lot of new things quickly are secondhand items as well as new things that are aesthetically nourishing (as such items are generally kept for longer and maintained more carefully). Both of these elements involve tactility, roughness and wholesome colour combinations.

The current consensus appears to be that improvements and progress are the equivalent of making things more comfortable, smoother, and more convenient by minimising friction and heaviness. Nevertheless, sustainable improvements could and should ideally mean something entirely different. Improvements should increase the tactile experience and foster a tangible bond between object and owner, or they should challenge the user’s senses and mind and induce more nourishing heaviness, or they should encourage the user to repair and maintain the object or perhaps even to share it with others, or they should activate the user and engage her in communal or sustainable actions.

Before designing yet another slightly better, slightly more convenient, slightly more streamlined, slightly easier to use version of a phone, a chair, a jacket, or a washing up bowl for that matter, the sustainable designer should question the very inclination for this task, by asking herself the following question: What can legitimise designing something new; are minor improvements or increased convenience a good enough reason? Can you, literally and metaphorically speaking, legitimise replacing your entire kitchen because you want new cupboards that don’t make any noise when you close them (and because you cannot solely change the cupboards, since kitchen elements typically don’t mix and match like Lego), and because the new countertop has a skinnier surface than your old one? Can that in any way be a legitimate reason to improve one’s belongings in a world with scarce resources? And, does today’s common consumer really need more convenience? Is allowing for and even encouraging increased lethargy and laziness by making repairs next to impossible (and replacements easier and cheaper and even doable online), by introducing yet another way of unlocking a phone or a computer or starting a tv-series streaming-service without having to move a finger (literally; writing and getting out of one’s chair seem to have become redundant activities), by introducing more unsustainable fleetingness; by smart-phoning and smart-homing everything and focusing on accessibility and user-friendliness above all really necessary?

[image error]A few of my instant-homeliness items

By insisting on convenience and accessibility we have deprived ourselves from “getting our hands dirty”, from rawness and wildness, from edifying hardship, from sensuously nourishing analogue experiences, and from the slow and satisfying act of having to learn to navigate and manage something new, to maintain and repair our belongings and to make food from scratch. But we are forgetting that a balanced life, a life worth sustaining and maintaining, a life that is justifiable and authentic consists of a balancing act. A balancing act that is not unlike that of the golden mean that the Greek philosopher Aristotle explored millenniums ago, which encourages living a good life worth maintaining by balancing between extremes. For example, according to Aristotle the virtue of courage is the middle way between cowardliness and recklessness or foolhardiness. Henceforth, both exaggeration and neglect will be destructive for building up strength. Human beings must uphold a balance, just like nature, argues Aristotle.

If we transfer Aristotle’s ancient wisdom to the art of sustainable living, and hence assess a sustainable life as the balancing point between two extremes, it is fundamental to initially ask: what are the extremes to be avoided? Streamlined convenience as one extreme and complete withdrawal from society as the other? Sensuous deprivation as opposed to an overload of aesthetic challenges? Overconsumption of trendy, insignificant knick-knacks at the one end of the scale and convulsively collecting and storing stuff at the other? Buying closed, static things that are inflexible and contain a linear development towards degeneration as the one extreme and investing in objects that are overly open and characterised by complete shapelessness as the other. Or, smoothness and firmness by all means at the one end of the scale and sloppiness and disorder at the other?

I have come to the realisation that nomadic, sustainable and responsible living is a balancing act between instantly reestablishing an entire home (involving immediately purchasing an overload of mass-produced items) and living out of a suitcase for an extended period of time. It is a balancing act between quick-fix solutions and slow indecisiveness. And it involves an ability to view home as a mindset rather than a place.